Abstract

Objectives

To share a concept analysis of social movement aimed at advancing its application to evidence uptake and sustainability in health-care.

Methods

We applied Walker and Avant method to clarify the concept of social movement in the context of knowledge uptake and sustainability. Peer-reviewed and grey literature databases were systematically searched for relevant reports that described how social movement action led to evidence-based practice changes in health and community settings. Titles, abstracts and full texts were reviewed independently and in duplicate, resulting in 38 included articles.

Results

Social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability can be defined as individuals, groups, or organizations that, as voluntary and intrinsically motivated change agents, mobilize around a common cause to improve outcomes through knowledge uptake and sustainability. The 10 defining attributes, three antecedents and three consequences that we identified are dynamic and interrelated, often mutually reinforcing each other to fortify various aspects of the social movement. Examples of defining attributes include an urgent need for action, collective action and collective identity. The concept analysis resulted in the development of the Social Movement Action Framework.

Conclusions

Social movement action can provide a lens through which we view implementation science. Collective action and collective identity – concepts less frequently canvassed in implementation science literature – can lend insight into grassroots approaches to uptake and sustainability. Findings can also inform providers and change leaders on the practicalities of harnessing social movement action for real-world change initiatives. By mobilizing individuals, groups, or organizations through social movement approaches, they can engage as powered change agents and teams that impact the individual, organizational and health systems levels to facilitate knowledge uptake and sustainability.

Keywords: Collective action, Collective identity, Grassroots, Implementation science, Knowledge-to-action, Mobilization, Social movement action

What is known?

-

•

Traditional, top-down approaches to implementation too often struggle to achieve the necessary active participation of staff to achieve and sustain the adoption of new practices as informed by evidence.

-

•

Grassroots, people-led approaches that engage social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability are lesser-known alternatives to traditional, programmatic ones.

What is new?

-

•

Social movement action engages individuals, groups and/or organizations to mobilize knowledge through key characteristics such as an urgent need for action, framing, intrinsic motivation, individual and collective action and collective identity.

-

•

Having a comprehensive understanding of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability and its elements offers a viable approach to implementation science and to those leading change that provides new perspectives.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, the field of implementation science has been marked by significant progress, as researchers and practitioners have worked together to develop a better understanding of implementation determinants, mechanisms and outcomes [1]. Yet, despite the progress and the abundance of literature on effective implementation strategies, suboptimal rates of adherence to evidence-informed decision-making and practices are common across health disciplines [[2], [3], [4], [5]] and successfully implemented interventions are too often not sustained [3,6,7].

Traditionally, most implementation strategies rely on top-down approaches that use prescriptive and tested guidelines and tools with sequential, planned steps to follow for end-users who are implementing an intervention or a change in practice in their setting [1,[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. However, the reliance on linear, rational notions of implementation is often not enough to achieve successful evidence uptake and sustainability. More recently, there is a shift toward co-created implementation that engages multiple stakeholders in the change process [13,14]. Recently, the use of social movement has been documented as a welcome innovation to evidence uptake and sustainability [10]. Here, intrinsically motivated individuals or groups who see a need and opportunity for change initiate action in their institutions. Many of these changes include the implementation of evidence (for example, practice guidelines or evidence-based interventions) to advance practice [9,10].

The application of grassroots approaches to implement evidence-based practice (EBP) or to increase knowledge uptake in different settings [15,16] has not received much theoretical attention, although applied sporadically for the past 20 years. A grassroots approach to change is characteristic of social movements in which individuals, groups, and/or organizations use their shared energy to achieve goals through self-directed actions. It contrasts with a top-down approach to change in which leaders plan and establish goals and milestones for “followers” [15]. While social movement approaches have demonstrated effectiveness to achieve important social change historically, it is unclear whether these approaches can be used to support the implementation and sustainability of evidence. Gaining a robust understanding of the concept of social movement and how social movement approaches facilitate and accelerate evidence uptake and sustainability can create a shift in the traditional paradigms of viewing knowledge translation as mainly a prescriptive approach.

We know that social movements are important drivers of societal change. For instance, they have contributed to eliminating slavery [17,18], establishing gender equality [19,20], and addressing racial inequality [21]. The phrase “social movement” is often used to describe a broad range of social transformations in a myriad of disciplines, resulting in the proliferation of definitions and descriptions. A social movement is largely described as a group of diffusely organized people or organizations striving toward a common goal relating to human society or social change [22]. Traditionally, definitions of social movements have highlighted the noninstitutionalized and minimally organized nature of collective actions, most of which form around the specific grievances or discontent of a group to promote or resist social change [[23], [24], [25]]. In the social sciences literature, social movements historically represent a “societal level force” for groups in the search for social justice and empowerment [26, p.35]

Can the concept of a social movement – a concept that originated as a driver for societal change – be also useful to institutional changes, implementation and implementation research? To advance this discussion and gain conceptual clarity, we engaged in a concept analysis of “social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability”, highlighting its defining attributes, antecedents and consequences. Our objectives were to 1) clarify the meaning of the concept, and 2) determine whether it can be used as an approach to support evidence uptake and sustainability in health-care settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Research design

A concept analysis helps gain a deeper understanding of the concept’s definitions, including all of its uses and its defining attributes (key characteristics), antecedents (preconditions), and consequences (outcomes) [27]. The eight steps of the Walker and Avant [27] concept analysis method are described in Table 1. For this article, steps 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 7 are featured.

Table 1.

Illustration of the eight steps in the Walker and Avant concept analysis method, and description of how each step was completed.

| Concept analysis step | Description of how each step was completed |

|---|---|

| 1. Select a concept | We selected the concept “social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability”. |

| 2. Determine the purposes of the analysis | We determined the purposes of analyzing to be:

|

| 3. Identify all of the uses of the concept | We defined the concept of “social movement” using a variety of sources including dictionaries, peer-reviewed and grey literature. |

| 4. Determine the defining attributes | After identifying all the different usages of a social movement for knowledge uptake and sustainability, we reviewed them to identify key characteristics that repeatedly appeared. At the end of this step, we generated a cluster of key characteristics frequently associated with the concept. |

| 5. Identify a model case | We sourced a model case that exemplifies the concept and includes all of its key characteristics. |

| 6. Construct additional cases | We developed a contrary case to contrast the model case and support the conceptual clarity of the concept. |

| 7. Identify antecedents and consequences | Next, we identified the antecedents (preconditions) and consequences (outcomes) of the concept. These elements refer to events or characteristics that must arise before the concept (antecedents) or may arise as the result of the concept’s occurrence (consequence). |

| 8. Define empirical referents | The final step in the concept analysis involved defining any empirical referents of the concept that are included in the literature identified for the concept analysis. |

The concept analysis was followed rigorously to achieve conceptual clarity of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability, in health-care. The work was supported by an international panel of experts (Leading Change Toolkit Expert Panel) who also contributed to the development of a new edition of an implementation resource entitled the Leading Change Toolkit [28] in which some of the results of the concept analysis (that is, the defining attributes, antecedents and consequences) are featured. The volunteer expert panel was recruited and invited to participate in recognition of their expertise in areas including implementation science, knowledge translation, patient advocacy and/or social movement action. It was led by two co-chairs – Dr. Doris Grinspun and Dr. Janet Squires (who are also the senior authors of this paper). The panel was comprised of individuals representing various health care and related disciplines; geographic areas in Canada, Australia, England, Spain and the United States; and health sectors (e.g., public health, primary care, home care, hospital care, long-term care, and academia).

2.2. Search methods

Two reviewers iteratively developed a search strategy (KW, SAL), in consultation with the two senior authors (DG, JES) and a subset of the expert panel as a working group. A health sciences librarian completed the search. A second team of health sciences librarians peer-reviewed the search strategy, consistent with the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) Guideline, to ensure sensitivity and specificity [29]. No revisions were indicated from this second review of the search strategy. A preliminary focused literature search to determine key terms in the topic area was conducted [12,13]. Key terms included social movement, collective identity, collective mobilization, people-led, large-scale change and evidence uptake. The health sciences librarian expanded on the list of key search terms submitted by the two reviewers. Once the search strategy was finalized, the two reviewers searched indexed databases in health and social sciences (see Appendices - Supplementary File 1), as the concept of social movement action is interdisciplinary. In addition, dissertations and theses, conference proceedings, books, and grey literature were searched. Databases were searched in the English language, from inception to June 4, 2019. The two reviewers also manually searched relevant health and social sciences journals and websites (see Appendices - Supplementary File 2) for potential papers that did not surface from our electronic searches. The expert panel reviewed their libraries to identify key articles not found through the search strategy. Articles submitted were included in the search results if the two reviewers independently determined that the papers met the inclusion criteria. Further, the two reviewers manually searched the references of the included publications at the full-text screening stage to uncover potential articles that did not surface in the electronic searches. (See Appendices - Supplementary File 3 for the full MEDLINE search strategy).

A separate search was conducted for dictionaries for the term “social movement” to support our understanding of the uses of the concept. (See Appendices - Supplementary File 4)

2.3. Screening and eligibility criteria

The two reviewers reviewed titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate, using a set of predetermined eligibility criteria including that the articles were peer-reviewed or grey literature with a focus on social movement approaches for knowledge uptake and sustainability in any setting (see Appendices - Supplementary File 5 for more details). Full texts of publications were retrieved for all articles that met screening criteria and were assessed for inclusion independently and in duplicate. The reviewers resolved disagreements through consensus; when required, a third senior team member made the final decision.

2.4. Data extraction and synthesis

Each of the two reviewers shared in the data extraction for all of the included publications using an Excel spreadsheet. Following extraction, the results were reviewed by the second reviewer and all cases of disagreement were resolved through consensus. Specifically, each of the two reviewers extracted study characteristics, which included: the discipline of the published article; the authors’ discipline(s); the setting; the purpose (as stated in the publication); the study design; and the stated definition(s) of a social movement (if available). To determine the commonalities across each description of a social movement in the context of knowledge uptake and sustainability, all examples of the concept and its components were extracted in detail. Following this, categories and subcategories were created and organized into antecedents, defining attributes or consequences.

Results were reviewed by members of the expert panel, who engaged in the creation of a framework of social movement in the context of knowledge uptake and sustainability over several sessions involving energized discussions and mapping exercises. This included the two co-chairs as well as some of the members of the expert panel who participated in a working group that met on a regular basis and provided feedback to the two reviewers. Members of the working group included panel members with and without expertise in social movement action. Following meetings with the working group, the two reviewers updated the full expert panel at regular virtual and in-person meetings on the progress and results of the concept analysis for their feedback and guidance.

Per the Walker and Avant method, and considering that data extracted were limited to definitions and features of the concept, a quality appraisal was not warranted. In addition, many of the publications were theoretical studies as opposed to empirical ones.

3. Results

3.1. Eligible studies

Title and abstracts of 27,832 citations were screened for relevance by applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria. This yielded 281 references that were reviewed in full text, with 38 retained for the final sample. (See Appendices - Supplementary File 6 for the search and screening process using a PRISMA diagram.)

3.2. Uses of the concept

Definitions of the term “social movement” from our review of the literature, including peer-reviewed and grey literature found through the concept analysis, and from hand-searched general and social sciences dictionaries were gathered [16,17,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37]] (See Appendices - Supplementary File 4 for more details). The review and breakdown of the definitions clarified the concept and defined some of its attributes. Social movement was often described as people-powered and innovative with individuals and groups connected through informal networks and shared purpose or as a type of innovation that promoted or resisted change to produce lasting effects.

3.3. Theoretical framework

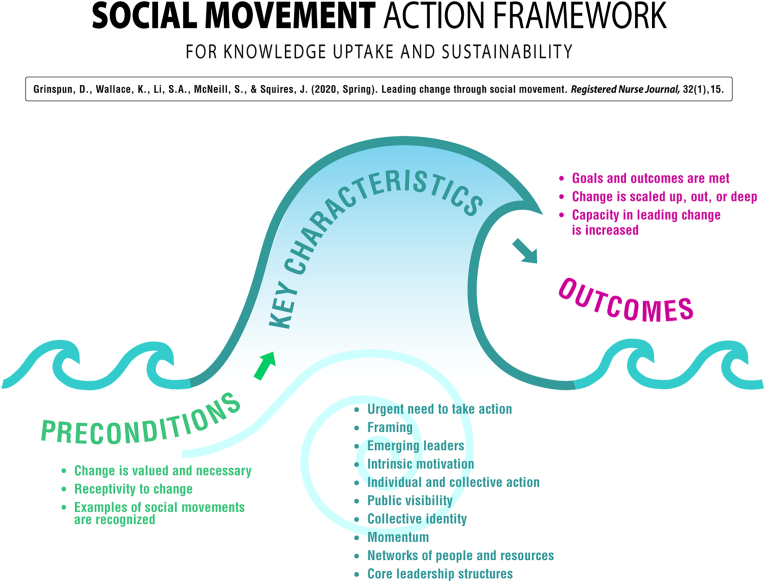

The concept analysis served as the foundation to develop a novel implementation framework that describes the necessary elements of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability. Named the “Social Movement Action (SMA) Framework” [38], it is inclusive of 10 defining attributes, three antecedents and three consequences (Fig. 1). The SMA Framework helps illustrate the key elements that can inform individuals, groups, and/or organizations to mobilize teams to adopt and sustain evidence-informed practices in different settings. It also illustrates how these elements are structured according to the three phases of defining attributes that evolve and occur during the social movement; the antecedents that occur before the onset of the social movement; and the consequences that may occur following it.

Fig. 1.

Social Movement Action Framework. (Used with permission from the authors.)

A graphic designer participated in conceptual discussions with the expert panel and created the image of the SMA Framework [38]. The social movement is depicted as a wave, an unstoppable force of nature that transforms energy. The wave image is superimposed on the three components of the concept analysis that are written in plain language: preconditions (antecedents); key characteristics (defining attributes); and outcomes (consequences).

3.4. Key characteristics of the SMA Framework

We identified 10 key characteristics (Urgent need to take action; Framing; Emerging leaders; Intrinsic motivation; Individual and collective action; Public visibility; Collective identity; Momentum; Networks of people and resources; and Core leadership structures). These key characteristics are defined and described in Table 2. The key characteristics indicate that the change is a priority and that there is a recognized opportunity to create change (Urgent need for change) [12,15,17,[39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44]]. This is communicated through framing [8,11,15,17,36,43,[45], [46], [47], [48]], by positioning the shared concern or strongly desired change and its underlying values and beliefs which engages individuals’ intrinsic motivation [15,34,40,43,[49], [50], [51], [52]]. As individuals, groups, and/or organizations become involved in social movement action and start taking individual and collective action [8,12,15,34,35,40,48,49,[53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59]], their leadership emerges [8,10,39,47,[49], [50], [51], [52]]. Activities of the social movement, key messages and outcomes are shared via public platforms, including social media, to raise and support public visibility [12,35,36,42,44,45,49,51,54,55]. The combined efforts of individual and collective action and their public presence support the momentum [15,17,43,44,60]. As individuals, groups, and/or organizations engage together in change, they develop a collective identity [10,15,34,40,48,51,54,56,61] reflecting a shared purpose and commitment to the cause and social ties to one another. This is also supported by engagement in networks of people and resources [10,12,15,36,[39], [40], [41], [42],48,51,54,59,62,63] with a similar focus of action. Finally, as the social movement develops, a core leadership structure [12,17,35,36,40,46,52,55,64,65] is needed to guide and support the social movement.

Table 2.

Key characteristics of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability.

| Key characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Urgent need to take action |

|

| Framing |

|

| Emerging leaders |

|

| Intrinsic motivation |

|

| Individual and collective action |

|

| Public visibility |

|

| Momentum |

|

| Collective identity |

|

| Networks of people and resources |

|

| Core leadership structures |

|

Each of the key characteristics is dynamic, interrelated and can appear in any order as the social movement emerges. When combined, the characteristics can exert a bidirectional, or sometimes a multi-directional relationship on one another and work in concert to mobilize social movement action; as such, they should not be understood as discrete, finite components. The SMA Framework [38] recognizes the fluid and evolving nature of social movements. For instance, key characteristics such as the urgent need to take action, framing and intrinsic motivation may work in concert to build individual and collective action and collective identity. Collective identity, in turn, can fuel the intrinsic motivation of individuals, groups, and/or organizations. Collective identity can also affect the momentum that is required to grow the social movement. Networks of people and resources can be the underlying fabric on which collective action and identity are formed. Networks that facilitate the social movement may be expanded through existing and/or acquired connections and relationships of informal and formal leaders. Core structures that support and respond to the dynamics of the social movement may also facilitate the expansion of networks and identification of emerging leaders. These are only a few examples of how key characteristics can weave together to mobilize a social movement. When at least two characteristics are present, synergy towards social movement action is likely generated [17,44]. Individuals, groups, and/or organizations must understand this and should aim to nurture each of these characteristics.

3.5. Preconditions of the SMA Framework

We uncovered three preconditions which we describe more fully in Table 3: “Change is valued and necessary”; “Receptivity to change”; and “Examples of a social movement are recognized”. For a social movement to occur, a shared concern or strongly desired change that is valued and regarded as necessary by individuals, groups, and/or organizations is required [9,12,15,17,[39], [40], [41],43,44,54,58,60,64]. Having a receptivity to change [15,34,[39], [40], [41],58,65] includes the presence of activist energy, as social movement action is fueled by energy for change. Individuals must also recognize examples of social movement action [10,12,15,16,34,35,44,52,54,65] as a powerful grassroots people-led approach to change. In our review of the literature, social movements that involve a change in practice are predicated on at least one of three preconditions in the SMA Framework [38] that may present in any order.

Table 3.

Preconditions of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability.

| Preconditions | Description |

|---|---|

| Change is valued and necessary |

|

| Receptivity to change |

|

| Examples of social movements are recognized |

|

3.6. Outcomes of the SMA Framework

We uncovered three outcomes of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability, each in its separate dimension (Table 4). These elements may occur in any order. The first element in the table relates to the goals of social movements; depending on the setting in which the social movement resides, the goals and outcomes of the social movement may be fully or only partially achieved [16,34,35,40,43,55,61]. The second element in Table 4 points to the changes that have occurred in the actual setting as a result of the social movement action; when change is perceived or determined as effective, it may be scaled up or out [11,35,44,66] to widen its influence and impact on other populations and settings. Or, it may be scaled deep [10,35,47], resulting in norms and values being changed. Finally, as a result of engagement in social movement action, individuals develop the capacity in leading change and are more likely to assume leadership roles due to these experiences [11,12,39,40,55,57,60].

Table 4.

Outcomes of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability.

| Outcomes | Description |

|---|---|

| Goals and outcomes are met |

|

| Change is scaled up, out, or deep |

|

| Capacity in leading change is increased |

|

3.7. Model case

A model case is defined as an example of a concept that includes all of its defining attributes to illustrate the concept in its entirety [27]. The following model case uses an example of a Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario Best Practice Spotlight Organization® (BPSO®) and its Best Practice Champions Program which supports organizations to implement and sustain best practice guidelines [52]. The chosen example is Fundación Oftalmológica de Santander (FOSCAL), a tertiary care hospital in Bucaramanga, Colombia – one of more than 1,000 exemplary BPSOs engaged in the global knowledge movement.

Staff nurses at FOSCAL BPSO recognized an urgent need for quality improvement and excellence in care [67]. The advancement of EBP was determined as a critical way to optimize nursing care outcomes, education and research. To this end, nursing and other staff that supported EBP chose to become champions of the BPSO program. As committed individuals and informal leaders, they used knowledge exchange and other collective action activities to disseminate information and actively engage staff, which resulted in markedly improved outcomes for patients, nurses’ satisfaction and the organization as a whole. The champions influenced and inspired their peers to engage in shared learning and improvement. Communications, including social media, were used to convey the goals and vision of the change publicly and build momentum. Through the nurses’ shared experiences, they developed a collective identity and wore badges that reflected their pride as change agents. As the change initiative evolved and momentum sustained, networks were established to facilitate connection with other champions and to access and share resources. A core structure of formal and informal leaders developed to organize and support the continuation of evidence-based practice.

3.8. Defining the concept of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability

Based on this analysis, the two reviewers and expert panel members developed the following definition of social movement action for knowledge uptake and sustainability:

Individuals, groups and/or organizations that, as voluntary and intrinsically motivated change agents, mobilize around a common cause to improve health outcomes through knowledge uptake and sustainability.

4. Discussion

The results of this concept analysis advanced the conceptual clarity of social movement approaches to support evidence uptake and sustainability. The concept analysis identified central approaches such as: taking urgent action on shared concerns or a strongly desired change through individual and collective action; and the development of a collective identity to support and achieve practice change.

The results of the concept analysis also supported the formulation of the SMA Framework [38] for knowledge uptake and sustainability. This framework structures the elements of social movement action across three key time phases:

-

•

the earliest phase (preconditions) as the urgent need for change begins to emerge and pressure for change rises;

-

•

the central phase in which social movement action develops (key characteristics); and

-

•

the concluding phase in which the impact of social movement action is seen (outcomes).

The SMA Framework [38] describes the typical lifespan of a social movement; however, it should not be regarded as a discrete entity. Rather, the outcomes may mobilize the next wave of social movement, where individuals, groups, and/or organizations identify an exemplar of social movement, see an opportunity to lead change, and recognize that a shared concern or strongly desired change is urgently needed and will positively affect individuals’ lives, services, and/or systems.

4.1. Social movement action

Although the SMA Framework [38] flows from empirical evidence supporting the effectiveness of social movements at institutional and systemic levels, elements in the framework are also found in many social movement frameworks that focus on social and political issues [24,68,69], as well as health reforms [35,[70], [71], [72], [73], [74]]. This supports the notion that social movements at the institutional and systemic levels follow similar patterns in the social movements that we largely recognize (for example, civil rights, democratic movements, and global movements). However, none of the pre-existing social movement frameworks include all of the elements contained in the SMA Framework; this illustrates the framework’s comprehensiveness and specificity to social movements that occur at the institutional and systemic levels to mobilize knowledge. As such, the framework’s ecological levels (micro, meso, macro) are worth exploring. Influential factors exerted at each level may impact the progression and fate of the social movement.

4.2. Implications for nursing practice

The SMA Framework [38] has practical value for nurses, teams, and work settings that have a thirst for quality improvement, EBP and other institutional changes. Social movement action engages frontline nursing staff, management and interprofessional teams in a bottom-up robust way creating energy to implement evidence-informed decision-making and practice changes that improve patient, staff and organizational outcomes. The framework can prospectively guide nurses and health organizations to assess their environment on whether it is conducive to social movement action by assessing the main elements that are observed in social movements. For instance, are nurses intrinsically motivated? Does the organization or unit encourage formal and informal leaders to drive change? If yes, the SMA Framework is perfect to accelerate change through an expanded network of individuals who share similar values toward the desired outcome. It is important to note that nurses, change teams and health organizations can consider all or some of the elements to ensure success in their social movements. Lastly, the framework can also be applied retrospectively to assess and reflect on social movements to understand their progression and outcomes.

The SMA Framework [38] may also be combined with other EBP or quality improvement implementation frameworks to accelerate and strengthen implementation initiatives for nurses and other members of the interprofessional team. The use of multiple frameworks represents an opportunity to move implementation science toward greater inter- or trans-disciplinarity, including incorporating principles from political science, sociology, anthropology and other social sciences. For instance, the SMA Framework’s key characteristic, “Networks of people and resources” may be combined with the Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) Framework’s [74] action cycle phase “Assess barriers and facilitators to knowledge use” in which having access to networks of individuals in the implementing setting may help change teams understand more about the barriers and facilitators from different perspectives. These networks may act as key informants to help change teams understand what other factors should be considered before implementing the change. They may also help change teams identify resources and tools to efficiently leverage facilitators and/or address barriers. Other examples of how the SMA and KTA Frameworks can be applied as complementary approaches and used to accelerate success and create lasting improvements are detailed in the online, freely accessible Leading Change Toolkit [28].

Social movement action is needed to mobilize and power frontline nursing staff, middle and senior management teams and other stakeholders such as patients and consumer groups, to engage energetically as a collective driven by shared concerns that align intrinsically with their values and beliefs. More importantly, the applicability and credibility in the context of implementation science offer an alternative to traditional, prescriptive strategies that too often fail to be sustained due to ineffective staff engagement. Intrinsically motivated individuals driving a shared agenda for EBP potentiate changes that are accelerated and sustained. Learning these characteristics and experimenting with them in real change situations enables frontline staff and others to optimize staff engagement, create momentum and reach sustained change in evidence uptake.

4.3. Limitations of the concept analysis

The search strategy was limited to articles published in English; therefore, articles in other languages that are relevant to the concept analysis may have been omitted. Many examples of social movements in health-care settings were in high-income countries such as Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. Examples of social movements in low- or middle-income countries may include patterns and characteristics distinct from those of high-income ones, due in part to the lack of available resources. Despite our comprehensive search strategy, this is a limitation of the literature and indicates an area for future studies. Finally, empirical studies included in this concept analysis did not examine the impact and the progression of the social movement beyond the short term. It is possible that social movements that are sustained beyond the short term are precipitated by different conditions, comprised of other key characteristics, and result in different outcomes. Future research should consider investigating the progression of social movements as a function of time, which has not been explored in this concept analysis.

4.4. Future considerations

The concept analysis resulted in a preliminary framework that requires testing for its feasibility, usability and appropriateness in implementation science. None of the studies we reviewed reported a social movement that included all of the elements presented in the SMA Framework [38]. The included studies demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating some of the elements of the framework but do not provide any documentation on whether social movements that include all elements are more effective and longer-lasting.

Further, whether and how elements of the SMA Framework [38] catalyze the mechanisms of social movements remain unknown. While we identified the elements that conceptualize and describe the lifespan of social movements in the context of knowledge adoption and sustainment, we do not know the relationships they have with each other or how they work together to drive change. More research should determine how each of these elements contributes to the progression of the social movement. For instance, what are the mechanisms behind each element? How does each key characteristic evolve into the next, and at which juncture? Are there certain social movements that could not advance to the next key characteristic, and why? Finally, how and to what extent, and in which contexts can the SMA Framework be used and combined with other implementation theories, models and frameworks? If this is not possible, why not? These questions warrant further exploration. Some answers may surface from individuals, groups and/or organizations who actively engage in social movement approaches by applying the framework and detailing their processes and outcomes to boost understanding. These may include current and future users of the Leading Change Toolkit [28].

5. Conclusions

Implementation efforts typically feature a top-down approach, in which change is introduced to the setting and certain incentives, user training and user education are applied to facilitate changes. Implementers usually find themselves having to engage stakeholders, identify champions, modify local contexts, and pour large amounts of resources to fund these programs so that users can adopt and sustain the practice. Social movements provide a new lens through which to view implementation. We see that social movement can develop out of grassroots, people-led actions. We observe elements including social cohesion, collective identity, momentum and public identity – concepts to date less frequently canvassed in implementation science – as central to social movement action. The SMA Framework [38] offers a new perspective on implementation science; it provides conceptual clarity on the concept of social movement in knowledge uptake and sustainability. It informs frontline staff and others as change leaders, academics and researchers on how social movement actions can be applied successfully to advance implementation science and knowledge uptake. By mobilizing individuals, groups, and/or organizations through social movement approaches, they can engage as powered change agents at the individual, organizational and health systems levels to facilitate evidence uptake and positively impact clinical practice, health outcomes and advocacy.

Ethical approval

As this was a concept analysis, ethical approval was not sought.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Doris Grinspun: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Katherine Wallace: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Shelly-Anne Li: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Susan McNeill: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Janet Squires: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Members of the Leading Change Toolkit Expert Panel: Jesús Bujalance, Maryanne D’Arpino, Gina De Souza, Nataly Farshait, Ian D. Graham, Alison Hutchinson, Kim Kinder, Celia Laur, Tina Mah, Julia E. Moore, Jennifer Plant, Jodi Ploquin, P. Jim A. Ruiter, Daphney St- Germain, Margie Sills-Maerov, May Tao, Marita Titler, Junqiang Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing - review & editing; John Gabbay: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization.

Funding

This work is part of a larger project to create a third edition of a foundational implementation resource, the Leading Change Toolkit (https://rnao.ca/leading-change-toolkit). The Leading Change Toolkit (Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario, 2021), developed in partnership with Healthcare Excellence Canada, was partially funded by Healthcare Excellence Canada and the Ontario Ministry of Health. All work produced by Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario is editorially independent of its funding source.

As the co-sponsor of the Leading Change Toolkit, Healthcare Excellence Canada, formerly Canadian Patient Safety Institute, collaborated with Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario to support the methodology, project deliverables and outcomes. This collaboration also resulted in the development of the SMA Framework, featured in this article.

Data availability statement

The authors declare the absence of shared data in the present study.

Declaration of competing interest

Doris Grinspun has declared a conflict of interest in the following categories: Support for attending meetings and/or travel; patents, planned, issued, or pending; Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory board; Leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee, or advocacy group paid or unpaid; and Receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services. None of the other co-authors declared having a conflict of interest that may have influenced the work reported in this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Zelmer, President and Chief Executive Officer, Healthcare Excellence Canada, as the executive co-sponsor of the Leading Change Toolkit, for her continued support and commitment. We would also like to thank Kristina Brousalis for her assistance with the editing of the manuscript. We would also like to recognize Dr. John Lavis, Jignesh Padia and Bernie Weinstein for their valued contributions to this work.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Nursing Association.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.08.003.

Contributor Information

Doris Grinspun, Email: dgrinspun@rnao.ca.

Katherine Wallace, Email: kwallace@rnao.ca.

Appendices. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Powell B.J., Fernandez M.E., Williams N.J., Aarons G.A., Beidas R.S., Lewis C.C., et al. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7:3. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ament S.M.C., de Groot Jja, Maessen J.M.C., Dirksen C.D., van der Weijden T., Kleijnen J. Sustainability of professionals' adherence to clinical practice guidelines in medical care: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tricco A.C., Ashoor H.M., Cardoso R., MacDonald H., Cogo E., Kastner M., et al. Sustainability of knowledge translation interventions in healthcare decision-making: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2015;11(1):55. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0421-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varsi C., Solberg Nes L., Kristjansdottir O.B., Kelders S.M., Stenberg U., Zangi H.A., et al. Implementation strategies to enhance the implementation of eHealth programs for patients with chronic illnesses: realist systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(9) doi: 10.2196/14255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yost J., Ganann R., Thompson D., Aloweni F., Newman K., Hazzan A., et al. The effectiveness of knowledge translation interventions for promoting evidence-informed decision-making among nurses in tertiary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0286-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruen R.L., Elliott J.H., Nolan M.L., Lawton P.D., Parkhill A., McLaren C.J., et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet. 2008;372(9649):1579–1589. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)61659-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiltsey Stirman S., Kimberly J., Cook N., Calloway A., Castro F., Charns M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dementia Action Alliance . 2011. The Right Prescription: a call to action on the use of antipsychotic drugs for people with dementia.https://dementiapartnerships.com/resource/the-right-prescription [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grinspun D., Bajnok I. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Transforming nursing through knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grinspun D. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Transforming Nursing through Knowledge: the conceptual and programmatic underpinnings of RNAO's BPG program; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sustainable Improvement Team. Horizons Team . 2018. Leading large scale change: a practical guide.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/practical-guide-large-scale-change-april-2018-smll.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waring J., Crompton A. A ‘movement for improvement’? A qualitative study of the adoption of social movement strategies in the implementation of a quality improvement campaign. Sociol Health Illness. 2017;39(7):1083–1099. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz A. Implementation brief: the potential of co-creation in implementation science. 2015. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-Metz-ImplementationBreif-CoCreation.pdf National Implementation Research Network.

- 14.Jackson C.L., Greenhalgh T. Co-creation: a new approach to optimising research impact? Med J Aust. 2015;203(7):283–284. doi: 10.5694/mja15.00219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bate S.P., Bevan H., Robert G. Towards a million change agents. A review of the social movements' literature: implications for large scale change in the NHS. 2004. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/32885680_Towards_a_million_change_agents_A_review_of_the_social_movements_literature_implications_for_large_scale_change_in_the_NHS

- 16.Elsey B. Hospice and palliative care as a new social movement: a case illustration from south Australia. J Palliat Care. 1998;14(4):38–46. doi: 10.1177/082585979801400407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bibby J., Bevan H., Carter C., Bate P., Robert G. The power of one, the power of many: bringing social movement thinking to health and healthcare improvement. https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/The-Power-of-One-the-Power-of-Many.pdf

- 18.King B.G., Pearce N.A. The contentiousness of markets: politics, social movements, and institutional change in markets. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:249–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casquete J. The power of demonstrations. Soc Mov Stud. 2006;5(1):45–60. doi: 10.1080/14742830600621183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snow D.A., Vliegenthart R., Corrigall-Brown C. Framing the French riots: a comparative study of frame variation. Soc Forces. 2007;86(2):385–415. doi: 10.1093/sf/86.2.385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devakumar D., Selvarajah S., Shannon G., Muraya K., Lasoye S., Corona S., et al. Racism, the public health crisis we can no longer ignore. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):e112–e113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31371-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicholas R.W. Social and political movements. Annu Rev Anthropol. 1973;2:63–84. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.an.02.100173.000431 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins J. Resource mobilization theory and the study of social movements. Annu Rev Sociol. 1983;9:527–533. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2946077 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tilly C. Centre for Research and Social Organization; Ann Arbor, MI: 1978. Studying social movements/studying collective action. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkinson P. MacMillan International Higher Education; 1971. Social movement. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maton K.I. Making a difference: the social ecology of social transformation. Am J Community Psychol. 2000;28(1):25–57. doi: 10.1023/A:1005190312887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker L.O., Avant K.C. vol. 4. Pearson Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2005. (Strategies for theory construction in nursing). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leading Change Toolkit| RNAO.ca. https://rnao.ca/leading-change-toolkit

- 29.McGowan J., Sampson M., Salzwedel D.M., Cogo E., Foerster V., Lefebvre C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;75:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koopmans R. The dynamics of protest waves: west Germany, 1965 to 1989. Am Socio Rev. 1993;58(5):637. doi: 10.2307/2096279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.della Porta D., Diani M. Blackwell Publishing; 1999. Forms, repertoires and cycles of protest. Social movements: an introduction; pp. 165–192. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris A.D. A retrospective on the civil rights movement: political and intellectual landmarks. Annu Rev Sociol. 1999;25:517–539. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parkinson G., Drislane R. Athabasca University; 2000. Online dictionary of the social sciences.https://bitbucket.athabascau.ca/dict.pl [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herechuk B., Gosse C., Woods J.N. Achieving environmental excellence through a multidisciplinary grassroots movement. Healthc Manag Forum. 2010;23(4):144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.hcmf.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell K. Collective action definition| open education sociology dictionary. https://sociologydictionary.org

- 36.del Castillo J., Khan H., Nicholas L., Finnis A. Nesta; 2016. Health as a Social Movement: the power of people in movements.https://www.ipcrg.org/sites/ipcrg/files/content/attachments/2019-10-29/health_as_a_social_movement-sept.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tremblay M.C., Martin D.H., McComber A.M., McGregor A., MacAulay A.C. Understanding community-based participatory research through a social movement framework: a case study of the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. BMC Publ Health. 2018;18:487. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5412-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grinspun D., Wallace K., Li S., McNeill S., Squires J. Leading change through social movement. RNJ. 2020;Spring https://rnj.rnao.ca/feature/leading-change-through-social-movement [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burbidge I. 2017. Releasing energy for change in our communities.https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/projects/psc/health-as-a-social-movement/rsa-releasing-energy-for-change-in-our-communities-report-nov-11.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carson-Stevens A., Patel E., Nutt S.L., Bhatt J., Panesar S.S. The social movement drive: a role for junior doctors in healthcare reform. J R Soc Med. 2013;106(8):305–309. doi: 10.1177/0141076813489677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Embry R.A., Grossman F.D. The Los Angeles County response to child abuse and deafness: a social movement theory analysis. Am Ann Deaf. 2006;151(5):488–498. doi: 10.1002/chp.4710.1353/aad.2007.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lippman S.A., Neilands T.B., Leslie H.H., Maman S., MacPhail C., Twine R., et al. Development, validation, and performance of a scale to measure community mobilization. Soc Sci Med. 2016;157:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bate P., Robert G., Bevan H. The next phase of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from social movements? Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(1):62–66. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bevan H., Plsek P., Winstanley L. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement; 2011. Leading large scale change: a practical guide.https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2011/06/Leading-Large-Scale-Change-Part-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davey L. From research to practice: communications for social change. N Dir Youth Dev. 2010;2009(124):83–90. doi: 10.1002/yd.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonner R., Hurley J., Ho E., Dabars E. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Value for the money: measuring the economic impact of BPSOs in Australia; pp. 433–461. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grinspun D., Botros M., Mulrooney L.A., No J., Sibbald R., Penney T. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Scaling deep to improve people's health: from evidence-based practice to evidence-based policy; pp. 465–491. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bauermeister M.R. Iowa State University; 2014. Social movement organizations in the local food movement: linking social capital and movement support[Dissertation] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kennedy L., Pinkney S., Suleman S., Mâsse L., Naylor P.J., Amed S. Propagating change: using RE-FRAME to scale and sustain A community-based childhood obesity prevention initiative. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. 2019;16(5):736. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White R., Mitchell T., Gyorfi-Dyke E., Sweet L., Hebert R., Moase O., MacPhee R., MacDonald B. Prince edward Island heart health dissemination research project: establishing a sustainable community mobilization initiative. Promot Educ. 2001;Suppl 1:13–17. PMID: 11677817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serna Restreopo A., Esparza-Bohórquez M., Abad Vasquez S., Cortés O.L., Granados Oliveros L.M., Belmar Valdebenito A., et al. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. The Latin-American BPSO experience: a consortium model; pp. 359–391. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bajnok I., Grinspun D., McConnell H., Davies B. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Best practice Spotlight organization: implementation science at its best; pp. 141–166. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Klaus T.W., Saunders E. Using collective impact in support of community-wide teen pregnancy prevention initiatives. Community Dev. 2016;14;47(2):241–258. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2015.1131172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lippman S.A., Maman S., MacPhail C., Twine R., Peacock D., Kahn K., et al. Conceptualizing community mobilization for HIV prevention: implications for HIV prevention programming in the African context. PLoS One. 2013;8(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wynn T.A., Taylor-Jones M.M., Johnson R.E., Bostick P.B., Fouad M. Using community-based participatory approaches to mobilize communities for policy change. Fam Community Health. 2011;34(Suppl 1):S102–S114. doi: 10.1097/fch.0b013e318202ee72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casas-Cortés M.I., Osterweil M., Powell D.E. Blurring boundaries: recognizing knowledge-practices in the study of social movements. Anthropol Q. 2008;81(1):17–58. doi: 10.1002/chp.4710.1353/anq.2008.0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis-Floyd R. Changing childbirth: the Latin American example. Midwifery today Int midwife. 2007;84:9. https://www.midwiferytoday.com/mt-articles/changing-childbirth-latin-american-example [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eltanani M., Laughlin S., Robertson T. Social movements and public health advocacy in action: the UK people's health movement. J Public Health. 2016;38(3):413–416. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdv085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Campbell C. Social capital, social movements and global public health: fighting for health-enabling contexts in marginalised settings. Soc Sci Med. 2020;257 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arnold S., Coote A., Harrison T., Scurrah E., Stephens L. 2018. Health as a social movement: theory into practice.https://www.thersa.org/globalassets/hasm-final-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 61.De Pedro K.T., Pineda D., Capp G., Moore H., Benbenishty R., Astor R.A. Implementation of a school districtwide grassroots antibullying initiative: a school staff and parent–focused evaluation of because nice matters. Child Sch. 2017;39(3):137–145. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdx008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moreno-Casbas T., Gonzalez-Maria E., Alborbnos-Munoz L. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. BPSO Host: a model for scaling out globally; pp. 319–331. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Timmings C., Heatley B., Whitney L., Quinn H., Canzian S. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Creating evidence-based cultures across the health continuum; pp. 187–215. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruglis J., Freudenberg N. Toward a healthy high schools movement: strategies for mobilizing public health for educational reform. Am J Publ Health. 2010;100(9):1565–1570. doi: 10.1002/chp.4710.2015/AJPH.2009.186619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shiers D., Smith J. In: Early intervention in psychiatry: EI of nearly everything for better mental health. Byrne P., Rosen A., editors. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014. Early intervention and the power of social movements: UK development of early intervention in psychosis as a social movement and its implications for leadership; pp. 335–357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McConnell H., Merali S., John S., McNeill S., Bajnok I. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. Scaling up and out: system-wide implementation initiatives; pp. 241–263. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Serna Restrepo A., Esparza-Bohórquez M., Abad Vasquez S., Cortés O., Granados Oliverso L., Belmar Valdebenito A., et al. In: Transforming nursing through knowledge. Grinspun D., Bajnok I., editors. Sigma Theta Tau; Indianapolis: 2018. The Latin-American BPSO experience: a consortium model; pp. 359–391. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azani E. Hezbollah: the story of the party of god. The Middle East in focus. Palgrave Macmillan; New York: 2009. Social protest movements—theoretical framework; pp. 1–22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Freeman J. In: The dynamics of social movements: resource mobilization, social control, and tactics. Zald M.N., McCarthy J.D., editors. Winthrop Publishers, Inc.; 1979. Resource mobilization and strategy: a model for analyzing social movement organization actions; pp. 167–189. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bate P., Robert G. In: Social movements and the transformation of American health care. Levitsky S., Zald M., editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2010. Bringing social movement theory to healthcare practice. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Grinspun D. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario; 2018. Advancing nursing and health through social movement thinking. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grinspun D. Transforming nursing through knowledge: progress on the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (RNAO) best practice guidelines programme. Enfermería Clínica. 2020;30(3):133–135. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcle.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grinspun D. Transforming nursing through knowledge: past, present and future of the Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario best practice guidelines program. MedUNAB. 2021;24(2):239–254. doi: 10.29375/01237047.3977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Graham I.D., Logan J., Harrison M.B., Straus S.E., Tetroe J., Caswell W., et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Continuing Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare the absence of shared data in the present study.