Abstract

This cohort study examines the association of self-reported postvaccination symptoms with anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody response among Framingham Heart Study participants contributing to the Collaborative Cohort of Cohorts for COVID-19 Research study.

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines (BNT162b2 [Pfizer-BioNTech] and mRNA-1273 [Moderna]) are associated with local and systemic symptoms; however, whether postvaccination symptoms are associated with vaccine-induced antibody response is unknown. Previous studies1,2,3 of COVID-19 vaccine reactogenicity and immunogenicity were limited to convenience samples that may not be generalizable. We studied the association of self-reported postvaccination symptoms with anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibody response among Framingham Heart Study (FHS) participants contributing to the Collaborative Cohort of Cohorts for COVID-19 Research (C4R) study.4

Methods

The FHS is an ongoing, prospective cohort study evaluating cardiovascular disease risk factors. In February 2021, participants were invited to self-administer C4R questions on COVID-19 vaccination (and associated symptoms) and submit a dried blood spot to test for anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (eFigure in the Supplement). This report includes participants who received 2 doses of mRNA vaccine at least 2 weeks before blood spot collection. Postvaccination symptoms were categorized as systemic symptoms (fever, chills, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, and/or moderate to severe fatigue) or local symptoms (injection site pain and/or rash). IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 spike subunit were measured using microsphere immunoassay (Luminex), chosen for its successful use in population-based serosurveys. Results were reported as median fluorescence intensity (MFI), with batch-specific reactive antibody response MFI cutoffs.5 Associations between postvaccination symptoms and antibody response were assessed by χ2 test and multivariable linear regression, with complete case analyses adjusted for batch, time since vaccination, and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. A 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Protocols were approved by institutional review boards of participating institutions and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Results

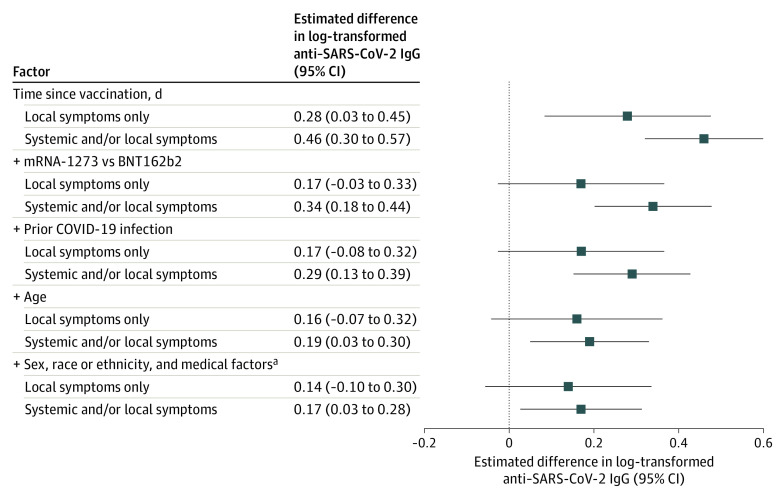

Of 3200 FHS participants eligible to participate in C4R, 928 (29%) completed the C4R questionnaire and blood spot collection and reported 2 doses of BNT162b2 (414 [45%]) or mRNA-1273 (514 [55%]) vaccines (eFigure in the Supplement). Respondents’ mean (SD) age was 65 (12) years, 360 (39%) were men and 568 (61%) were women, 893 (96%) were non-Hispanic White, and 84 (9%) self-reported prior COVID-19 infection. After either vaccine dose, 446 participants (48%) reported systemic symptoms, 109 (12%) reported local symptoms only, and 373 (40%) reported no symptoms. In bivariate analysis, symptoms were associated with younger age, female sex, prior infection, and the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Table). Antibody reactivity was observed in 365 asymptomatic participants (98%), 108 participants (99%) with only local symptoms, and 444 participants (99%) with systemic symptoms (P = .08). In adjusted models, systemic symptoms were associated with greater antibody response, although associations were attenuated with sequential adjustment for potential confounders (Figure). Similar results were obtained with exclusion of participants with prior COVID-19 infection.

Table. Characteristics of Study Participants by Self-reported Symptoms After SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA Vaccinationa.

| Characteristic | No symptoms (n = 373) | Local symptoms only (n = 109) | Systemic symptoms (n = 446) | P valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 68 (12) | 69 (11) | 62 (12) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 195 (52) | 38 (35) | 127 (28) | <.001 |

| Female | 178 (48) | 71 (65) | 319 (72) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| White | 362 (97) | 105 (96) | 426 (95) | .40 |

| Other racial or ethnic groupc | 10 (3) | 4 (4) | 20 (5) | |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | |

| Vaccine | ||||

| BNT162b2 | 214 (57) | 41 (38) | 159 (36) | <.001 |

| mRNA-1273 | 159 (43) | 68 (62) | 287 (64) | |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28 (5) | 28 (6) | 28 (6) | .87 |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 191 (51) | 53 (49) | 242 (54) | .72 |

| Former | 146 (39) | 46 (42) | 170 (38) | |

| Current | 36 (10) | 10 (9) | 34 (8) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 159 (43) | 45 (42) | 163 (37) | .21 |

| Diabetes | 39 (10) | 16 (15) | 47 (11) | .41 |

| Coronary heart disease | 32 (9) | 9 (8) | 31 (7) | .67 |

| Heart failure | 4 (1) | 3 (3) | 1 (0) | .03 |

| eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 344 (93) | 99 (93) | 425 (96) | .26 |

| Stroke or TIA | 12 (3) | 3 (3) | 8 (2) | .42 |

| Prior COVID-19 | 19 (5) | 6 (6) | 59 (13) | <.001 |

| MFI S-antibody reactive | 365 (98) | 108 (99) | 444 (99) | .08 |

| Log-antibody, mean (SD) | 8 (1) | 9 (1) | 9 (1) | <.001 |

| Time from vaccination, mean (SD), d | 118 (63) | 129 (67) | 122 (68) | .34 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Data are presented as number (percentage) of participants unless otherwise indicated. Participants were classified as having any systemic symptoms (fever, chills, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, and/or moderate to severe fatigue), local symptoms only (injection site pain and/or rash), or no symptoms after either messenger RNA vaccine dose.

P values are from the χ2 test or unpaired t test.

Other racial or ethnic group includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black, and Hispanic or Latino.

Figure. Association of Self-reported Symptoms After SARS-CoV-2 Messenger RNA Vaccination With Continuous Log-Transformed Values for Anti-Spike IgG Antibodies Among 928 Fully Vaccinated Framingham Heart Study Participants, February 2021 to January 2022.

Effect estimates for self-reported symptoms compared with no symptoms with 95% CIs. Plus signs indicate that those factors were sequentially added to the model.

aMedical factors include body mass index, smoking status, diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke or transient ischemic attack, and estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Discussion

In a sample of twice-vaccinated, older, community-dwelling US adults, self-reported systemic symptoms after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination were associated with greater antibody response vs local-only or no symptoms. These results agree with a previous report6 in US health care workers that showed higher postvaccination antibody measurements among those with significant symptoms after an mRNA vaccine. This report identifies age, sex, and Moderna vaccine as factors associated with both vaccine reactogenicity and immunogenicity, consistent with prior observations.3,6 No association was observed between symptoms after vaccination and race or ethnicity, body mass index, or comorbidities. In this generalizable cohort, nearly all participants exhibited a positive antibody response to complete mRNA vaccine series. Nonetheless, systemic symptoms remained associated with greater antibody response in multivariable-adjusted models, highlighting unexplained interpersonal variability. Further research on biological mechanisms underlying heterogeneity in vaccine response is needed. Limitations of this report include an older, predominantly non-Hispanic White, professional cohort; potential recall bias; and use of MFI, which is not standardized against neutralizing antibody titers. In conclusion, these findings support reframing postvaccination symptoms as signals of vaccine effectiveness and reinforce guidelines for vaccine boosters in older adults.

eFigure. Flowchart of Study Participants Who Completed the C4R Questionnaire, Submitted a Dried Blood Spot for Evaluation and Received Two Doses of Either Pfizer-Biontech or Moderna SARS Cov-2 Vaccines

References

- 1.Bauernfeind S, Salzberger B, Hitzenbichler F, et al. Association between reactogenicity and immunogenicity after vaccination with BNT162b2. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1089. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Held J, Esse J, Tascilar K, et al. Reactogenicity correlates only weakly with humoral immunogenicity after COVID-19 vaccination with BNT162b2 mRNA (Comirnaty®). Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(10):1063. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hwang YH, Song KH, Choi Y, et al. Can reactogenicity predict immunogenicity after COVID-19 vaccination? Korean J Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1486-1491. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2021.210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oelsner EC, Krishnaswamy A, Balte PP, et al. ; for the C4R Investigators . Collaborative cohort of cohorts for COVID-19 research (C4R) study: study design. Am J Epidemiol. 2022;191(7):1153-1173. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwac032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Styer LM, Hoen R, Rock J, et al. High-throughput multiplex SARS-CoV-2 IgG microsphere immunoassay for dried blood spots: a public health strategy for enhanced serosurvey capacity. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9(1):e0013421. doi: 10.1128/Spectrum.00134-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debes AK, Xiao S, Colantuoni E, et al. Association of vaccine type and prior SARS-CoV-2 infection with symptoms and antibody measurements following vaccination among health care workers. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1660-1662. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.4580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flowchart of Study Participants Who Completed the C4R Questionnaire, Submitted a Dried Blood Spot for Evaluation and Received Two Doses of Either Pfizer-Biontech or Moderna SARS Cov-2 Vaccines