Abstract

In this study, we examine the respective effects of prosocial personality and grandiose narcissism on individual social responsibility, and attitudinal and behavioral responses to Covid-19 health and safety preventive measures. We further analyze the extent to which individuals feel targeted by bullies for wearing a mask in order to shed light on the psychological consequences of the current pandemic. We employed a cross-sectional technique using a snowball sampling method to recruit participants from the United States and Canada. We obtained a total of 968 completed surveys. Results of SEM reveal that prosocial personality enhances individual social responsibility and positive responses to health and safety preventive measures, whereas grandiose narcissism augments negative responses. Results highlight that socially responsible individuals report being bullied for wearing a mask. Findings are discussed in light of the characteristics of the respondents, and cultural aspects.

Keywords: Prosocial personality, Grandiose narcissism, Individual social responsibility, Bullying, Pandemic, Covid-19, Public health

1. Introduction

The highly communicable airborne virus Covid-19 is omnipresent in the news as the number of cases keep mounting throughout the world. Critical resurgences appeared throughout the most developed nations leading Canada to introduce curfews and lockdowns. The United States faced a surge of infections with a death toll exceeding forecasts (CDC, 2021). Such unfolding setbacks shed doubts concerning an eventual return to social normalcy. The situation is dire and the burden to reduce the transmission of Covid-19 rests on individual social responsibility to protect others.

Although individuals are requested to follow health and safety guidelines such as mask wearing and social distancing, anti-maskers routinely challenge such measures with protest rallies putting themselves and others at risk. Consequently, it is essential to develop an accurate view regarding the dispositional characteristics of individuals who flout health and safety measures and engage in health-risk behavior that can threaten the health and safety of others (Nowak et al., 2020). Likewise, it is crucial to identify personality traits that enhance individual social responsibility and compliance with health and safety preventive measures. Such individual differences can significantly impact societal health and safety outcomes (Hughes & Machan, 2021). Furthermore, it is important to address whether individuals feel targeted by bullies for wearing a mask in order to shed light on the psychological consequences of the pandemic.

Therefore, we analyze the role of personality in predicting how individuals react to mask wearing and social distancing. More specifically, we analyze the respective predictive effects of prosocial personality (Penner et al., 1995) and grandiose narcissism (Paulhus, 2001; Raskin & Terry, 1988) on individual social responsibility (Droms Hatch & Stephen, 2015) and health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses to Covid-19 preventive measures. We further analyze the extent to which socially responsible individuals report being bullied (Einarsen, 1999).

2. Theory

2.1. Prosocial personality

Personality refers to stable dispositional propensities that explicate individual differences in patterns of thoughts, attitudes and behaviors (McCrae & Costa, 2003). Personality constitutes a significant predictor of health and safety attitudes and behaviors. For instance, conscientiousness-related traits reduce health-risk and unsafe behaviors and enhance beneficial health-related behaviors (Beus et al., 2015; B.W. Roberts & Bogg, 2004). The positive role of conscientiousness in promoting physical health and longevity (B.W. Roberts et al., 2014) can be attributed to the fact that conscientious individuals follow prescribed social norms, are precautious, act dutifully, and show resilience (McCrae & Costa, 2003) while dealing with stressful events (Bartley & Roesch, 2011; Luo & Roberts, 2015).

Poor health behavior and unsafe risky behavior are primarily responsible for mortality and poor health outcomes in the United States (McGinnis & Foege, 1993). However, meta-analytic research shows that responsibility reduces harmful health and safety behaviors (Bogg & Roberts, 2004). The personality trait of responsibility refers to a high sense of obligation to the welfare and security of the group, and personal accountability (Gough et al., 1952).

Altruism, defined here as the propensity to selflessly help others, can enhance safety behaviors. Individuals who are conscientious and altruistic seem better equipped to deal with critical situations in their personal, social and professional lives. Oda et al. (2014) found that conscientious individuals act in an altruistic manner in dealing with their family members. Furthermore, altruistic individuals are more apt to make blood donations over time (Steele et al., 2008), thereby showing consideration for the urgent needs of others. Consistent with such findings, research shows that some individuals can incur significant personal costs to help others (C.D. Batson & Shaw, 1991). Altruistic motives generate adaptive prosocial behavior through a genuine need to help others (C.D. Batson & Powell, 2003). In brief, conscientiousness, responsibility and altruism constitute essential traits of prosocial personality (Penner et al., 1995).

2.2. Individual social responsibility

In an individualistic culture emphasizing individual freedom and self-sufficiency, the belief that people should decide for themselves is widespread. The resultant lack of social cohesiveness has the potential to impede the effectiveness of health and safety preventive measures. Consequently, the notion of personal health responsibility is often utilized by public health authorities to make a persuasive appeal to the population and increase socially responsible behavior.

Individual social responsibility pertains to being responsible for the consequences of one's actions that directly impact other individuals and communities (Droms Hatch & Stephen, 2015). Individual social responsibility enhances prosocial behavior such as giving to charities, investing in socially responsible funds (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010), and making green purchases (Rahimah et al., 2018). Such prosocial actions are motivated by altruism (Bénabou & Tirole, 2010; Droms Hatch & Stephen, 2015).

Socially responsible individuals exhibit low hostility and rebelliousness (Berkowitz & Lutterman, 1968). For instance, individual social responsibility predicts less divorce and better health-related behaviors among women (B.W. Roberts & Bogg, 2004). Socially responsible individuals believe in the righteousness of societal values, are not contemptuous of vulnerabilities, and possess a sense of duty (Berkowitz & Lutterman, 1968). As a consequence, they will bear the extra load of protecting others, which can augment their stress or Covid-19 mental fatigue. Nevertheless, individual social responsibility enhances adequate social adjustment.

2.3. Negative health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses

In a pluralistic society in which debates over mask mandates raise concerns over individual freedom, attitudinal and behavioral responses to health and safety preventive measures will vary considerably depending on the worth individuals ascribe to public health authorities. Prosocial personality should be associated with constructive viewpoints and attendant well-adjusted responses to health and safety preventive measures such as mask wearing and social distancing. Prosocial personality should enhance adequate perceptions of information from the media and public health authorities. Taken together, the prosocial traits of conscientiousness, responsibility and altruism suggest a strong moral character, which augments resourcefulness under stressful conditions (Gough et al., 1952). Prosocial personality is responsive, adaptive and constructive. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 1a

Prosocial personality increases individual social responsibility.

Hypothesis 1b

Prosocial personality reduces negative attitudinal and behavioral responses to Covid-19 preventive measures.

2.4. Grandiose narcissism

Narcissists are self-centered and lack consideration for others. Narcissists exhibit a grandiose sense of self-importance and believe that they are invulnerable (Judge et al., 2006). Narcissists are referred to as disagreeable, hostile, arrogant (Paulhus, 2001), self-indulgent and nonconforming (Raskin & Terry, 1988). Consistent with such description, research shows that narcissism is strongly related to social supremacy orientation, right wing political ideology (Kerr et al., 2021) and prejudice against minorities (Cichocka et al., 2017). Narcissists display irresponsible uninhibited conduct (Gentile et al., 2013) that can be reckless in the context of a pandemic.

Of particular interest, research shows that grandiose narcissism predicts greater health-risk behaviors (Buelow & Brunell, 2014). Grandiosity is inherent to the definition of narcissism (Raskin & Terry, 1988) and refers to a lack of disconnection between an idealized representation of the self and the actual self. Grandiose narcissists project an image of toughness and self-confidence (Raskin & Terry, 1988) to nurture their self-aggrandized and distorted self-representation (Emmons, 1987).

We expect grandiose narcissists to be skeptical of recommendations issued by public health authorities (Nowak et al., 2020) and to exhibit high self-reliance to strengthen their idealized invulnerable sense of self. To this point, there is no research on the predictive effect of grandiose narcissism on individual social responsibility in the context of new social norms prescribed by public policy officials. Therefore, we propose:

Hypothesis 2a

Grandiose narcissism reduces individual social responsibility.

Hypothesis 2b

Grandiose narcissism increases negative attitudinal and behavioral responses to Covid-19 preventive measures.

2.5. Being bullied

Bullying consists of aggressive and antisocial behavior such as embarrassing, belittling and insulting a target (Einarsen, 1999). In the context of the pandemic, incidents of bullying oriented toward individuals who adhere to health and safety measures were reported in the news as exemplified by the case of passengers on a ferry of British Columbia who were verbally abused by anti-maskers (Correia, 2020). In such context, bullying can be conceived as a means to resist change and social norms (Einarsen, 1999).

We posit that socially responsible individuals can constitute targets of bullying. The literature highlights that targets of bullying express psychological distress and feel victimized (Nielsen et al., 2012). Victimization from bullying stems from behaviors perceived as threats to the psychological and physiological wellbeing of a target (Nielsen et al., 2012). A target who shows submissiveness to new social norms, such as mask wearing, can be perceived as vulnerable. Although most studies on the effect of target vulnerability were conducted in schools, target vulnerability has shown a consistent relationship with bullying (Strindberg et al., 2020). The salience of mask wearing can indicate target vulnerability and provoke unwanted aggressive reactions from bullies. The literature examined a target's proneness to fear and negative feelings (Strindberg et al., 2020). However, it neglected bullying due to a target's socially responsible behavior. Therefore, we offer:

Hypothesis 3

Individual social responsibility positively predicts being bullied.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

We employed a snowball sampling technique to gather data using an electronic survey with Qualtrics. Instructions requested participants to state that they were at least 18 years of age. Participation was entirely voluntary and anonymous. We collected data from mid-July through early September of 2020. We obtained 968 completed surveys. A total of 938 respondents provided information on their citizenship. Of them, 89% were citizens of the United States and about 10% of Canada. Of the 926 respondents who indicated their gender 27% were men and 73% were women. A total of 933 respondents provided their age. The mean age and standard deviation are 38.32 and 17.34, respectively.

3.2. Measures

Items were measured with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree. For prosocial personality and grandiose narcissism, respondents rated how each adjective corresponds to their personal characteristics. For individual social responsibility, health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses, and for being bullied, respondents indicated their extent of agreement with each sentence. Concepts were not mentioned in the survey and items were mixed throughout the survey to avoid consistency bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

3.2.1. Prosocial personality

We generated five single adjectives using definitions of responsibility and positive character from Gough (1952) and Lanning and Gough (1991), and of conscientiousness from B.W. Roberts et al. (2014).

3.2.2. Grandiose narcissism

We employed six single adjectives from the Narcissistic Grandiosity Scale (NGS; Rosenthal et al., 2019) to measure grandiose narcissism.

3.2.3. Individual social responsibility

We developed seven items to measure individual social responsibility. Three items assessed individual responsibility with respect to the transmission of coronavirus. Two items assessed the recognition of one's vulnerability to Covid-19 and two items measured mental stress.

3.2.4. Health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses

We developed a 10-item scale to measure individual responses to Covid-19 health and safety preventive measures. We built five items pertaining to mask wearing, two items measuring social distancing and three items assessing how people react to relevant public information. High scores on this scale indicate stronger negative responses.

3.2.5. Being bullied

We developed three items to assess whether people experienced being bullied for wearing a mask.

3.3. Procedures

We used structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the hypotheses. We created three parsimonious independent models. In model 1, we assessed the effect of prosocial personality on individual social responsibility (ISR) and on negative health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses (HSABR). In model 2, we evaluated the effect of grandiose narcissism on ISR and on negative HSABR. Finally, model 3 analyzed the sequential respective effects of prosocial personality and ISR on being bullied.

In order to improve fit indices, we reduced the number of parameters to estimate (Benson & Bandalos, 1992). Scale refinement is supported by adequate construct reliability and validity (MacCallum & Austin, 2000). We computed the means of the respective items pertaining to individual responsibility, vulnerability to Covid-19 and mental stress and used the obtained means as indicators of the latent construct of ISR. Likewise, we calculated the means of the respective items pertaining to mask wearing, social distancing and public information and used the obtained means as indicators of the latent construct of negative HSABR.

4. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the study variables. We computed t-tests to address gender and country differences. Women (men coded 1 and women coded 2) were found to be most at risk of being bullied (t = −2.62, p < .01). Citizens of the United States (United States coded 1 and Canada coded 2) were likely to report being bullied (t = 4.29, p < .01). Women were higher on prosocial personality (t = −6.11, p < .01), ISR (t = −5.10, p < .01) and lower on grandiose narcissism (t = 2.50, p < .01), and negative HSABR (t = 4.97, p < .01). Respondents from the United States rated themselves lower on grandiose narcissism (t = −2.55, p < .05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 PP | 4.37 | 0.44 | ||||

| 2 GN | 2.67 | 0.65 | 0.05 | |||

| 3 ISR | 4.12 | 0.76 | 0.35** | −0.05 | ||

| 4 HSABR | 1.83 | 0.86 | −0.29** | 0.10** | −0.86** | |

| 5 BB | 2.26 | 0.97 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.21** | −0.13** |

Notes: PP = Prosocial Personality; GN = Grandiose Narcissism; ISR = Individual Social Responsibility; HSABR = Negative Health and Safety Attitudinal and Behavioral Responses; BB = Being Bullied; SD = Standard Deviation ** significant p < .01.

We analyzed potential common method variance (CMV) using Harman's single factor method for the overall measurement model. In doing so, we included all individual indicators pertaining to each latent construct. Test results explained only 30.45% of the total variance, thereby suggesting no common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Exploratory factor analysis (FA) with varimax rotation was employed to assess construct validity. We obtained significant KMO's above 0.80 and Bartlett's tests of sphericity were below 0.05.

In the first FA, we included all the personality adjectives. We obtained an unconstrained 2-factor solution. The first factor corresponding to grandiose narcissism explained 27% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 3.03. The second factor pertaining to prosocial personality explained an additional 24% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 2.57. Convergent validity is adequate as revealed by exclusive factor loadings ranging from 0.65 to 0.74 for grandiose narcissism and from 0.60 to 0.79 for prosocial personality. All cross-factor loadings were below 0.16.

In order to assess the independence of the concepts for model 3, we entered all items pertaining to prosocial personality, ISR and being bullied in a single factor analysis. We obtained an unconstrained 3-factor solution. The first factor corresponding to ISR explained 26.37% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 4.70. The second factor matching prosocial personality explained an additional 17.28% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 2.34. The third factor corresponding to being bullied explained an additional 15.12% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 1.78. Each item loaded exclusively on its respective factor. Factor loadings ranged from 0.63 to 0.81 for the seven items of ISR, from 0.58 to 0.79 for prosocial personality and from 0.84 to 0.87 for being bullied. Cross-factor loadings were all below 0.20 except for one item with a cross-factor loading of less than 0.30.

For the 10 items of HSABR, we obtained a single factor solution explaining 60% of the variance with an eigenvalue of 5.99. Factor loadings ranged from 0.64 to 0.88. Cronbach alpha coefficients were all above 0.70, thereby indicating good reliability. Table 2 presents the results for the measurement model including all survey items.

Table 2.

Constructs and measures.

| Construct and measurement item | Standardized loading |

|---|---|

| Prosocial personality α = 0.76; CR = 0.87; AVE = 0.60 | |

| Responsible | 0.80 |

| Caring | 0.77 |

| Helpful | 0.75 |

| Conscientious | 0.64 |

| Diligent | 0.60 |

| Grandiose narcissism α = 0.80; CR = 0.81; AVE = 0.41 | |

| High-status | 0.74 |

| Superior | 0.71 |

| Powerful | 0.71 |

| Prominent | 0.70 |

| Dominant | 0.70 |

| Envied | 0.65 |

| Individual social responsibility (ISR) α = 0.87; CR = 0.83; AVE = 0.62 | |

| Responsibility | |

| I believe that I am part of a collective endeavor in the fight of Covid-19 | 0.82 |

| It is everyone's social responsibility to prevent the transmission of Covid-19 | 0.82 |

| I feel personally responsible for preventing the transmission of Covid-19 | 0.82 |

| Mental stress | |

| I feel exhausted with others who do not want to wear masks | 0.77 |

| When I hear people cough and sneeze it worries me | 0.72 |

| Vulnerability to Covid-19 | |

| I am not vulnerable to Covid-19 (reversed scored) | 0.65 |

| Anyone can be a victim of Covid-19 | 0.64 |

| HSABR α = 0.92; CR = 0.89; AVE = 0.73 | |

| Mask wearing | |

| Wearing a mask in public is useless | 0.88 |

| Masks cannot be mandatory | 0.87 |

| I have a right not to wear a mask in order to protect my individual freedom | 0.81 |

| I feel justified not to wear a mask in public transits | 0.79 |

| People who wear masks in public have unjustifiable fears | 0.65 |

| Social distancing | |

| Social distancing only serves the purpose of feeding people's fears | 0.87 |

| Social distancing protects us (reversed score) | 0.64 |

| Public information | |

| The pandemic is exaggerated by the media | 0.80 |

| Covid-19 is not any more dangerous than the flu | 0.73 |

| I do not think that the virus is spreading in my community | 0.66 |

| Being bullied α = 0.83; CR = 0.83; AVE = 0.62 | |

| Some people laugh at me for wearing a mask | 0.87 |

| Some people bullied me for wearing a mask | 0.87 |

| I sometimes feel devalued by others because I wear a mask | 0.85 |

Notes: CR = composite reliability; AVE = average variance extracted; HSABR = Health and Safety Attitudinal and Behavioral Responses. Sample consisted of 968 respondents. χ2 = 344.94, d.f. = 145, CMIN/d.f. = 2.38, p < .05; GFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.98; NFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04 [0.02–0.05].

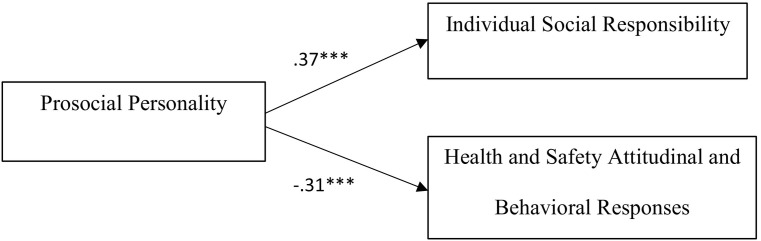

Model 1 yielded strong fit indices: GFI =0.99, AGFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, and RMSEA = 0.04 [0.03–0.05]. Prosocial personality increased ISR with a path coefficient of 0.37 (p < .01) and reduced negative HSABR with a path coefficient of −0.31 (p < .01), thereby supporting hypotheses 1a and 1b. Fig. 1 illustrates the findings.

Fig. 1.

Prosocial personality relationships with individual social responsibility and health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses. Notes: Sample consisted of 968 respondents. ꭓ2 = 75.46, d.f. = 32, GFI =0.99; AGFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99 RMSEA = 0.04 [0.03–0.05]. * p < .050, ** p < .010, *** p < .001 one-tailed.

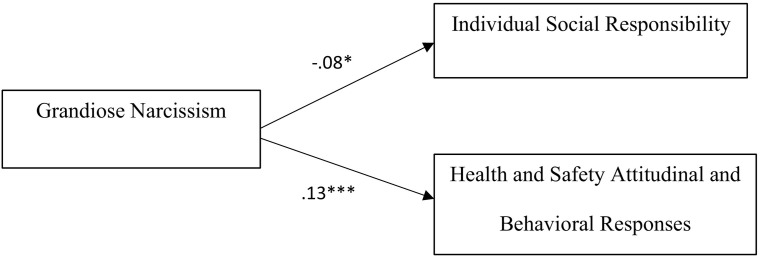

Model 2 yielded strong fit indices: GFI =0.99, AGFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, and RMSEA = 0.03 [0.03–0.05]. Grandiose narcissism reduced ISR with a path coefficient of −0.08 (p < .05) and increased negative HSABR with a path coefficient of 0.13 (p < .01). Findings support hypotheses 2a and 2b. Fig. 2 illustrates the findings.

Fig. 2.

Grandiose narcissism relationships with individual social responsibility and health and safety attitudinal and behavioral responses. Notes: Sample consisted of 968 respondents. ꭓ2 = 79.86, d.f. = 45, GFI =0.99; AGFI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99 RMSEA = 0.03 [0.03–0.05]. * p < .050, ** p < .010, *** p < .001 one-tailed.

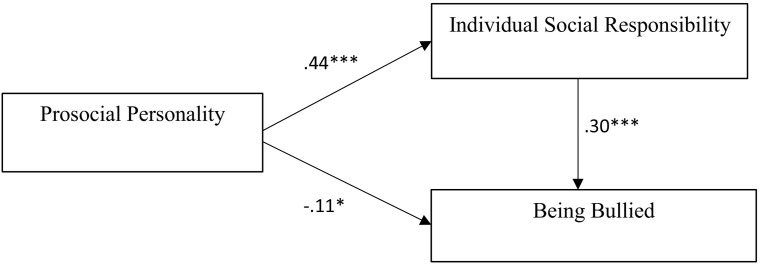

Model 3 yielded strong fit indices: GFI = 0.99, AGFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.99, NFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.98, and RMSEA = 0.04 [0.03–0.05]. Prosocial personality had a positive predictive effect on ISR with a path coefficient of 0.44 (p < .01). ISR had a positive predictive effect on being bullied with a path coefficient of 0.30 (p < .01). Findings support hypothesis 3. Fig. 3 illustrates the findings.

Fig. 3.

Prosocial personality relationships with individual social responsibility and being bullied. Notes: Sample consisted of 968 respondents. ꭓ2 = 80.29, d.f. = 33, GFI = 0.99; AGFI = 0.97; CFI = 0.99; NFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.98 RMSEA = 0.04 [0.03–0.05]. * p < .050, ** p < .010, *** p < .001 one-tailed.

5. Discussion

This study highlights the important role of personality as a predictor of individual social responsibility and attitudes regarding the health and safety of others. Findings suggest that prosocial individuals invest in the health and safety of others. Prosocial personality generates adaptive and well-adjusted constructive responses to health and safety measures. Grandiose narcissists foresee the consequences of their actions in a self-interested way, and may not see health and safety preventive measures as part of a social exchange. Grandiose narcissists can view such measures as wrongfully imposed personal restrictions with attendant potential deleterious effects on the prevention of Covid-19.

Interestingly, findings indicate that Americans were less likely to rate themselves high on grandiose narcissism. Paradoxically, it is interesting to note that there is stronger adherence to health and safety measures and obedience to authority in Canada. In fact, Canada is clearly most effective in the containment of Covid-19 (Leonhardt, 2020). We attribute such situational differences in part to the consensus among politicians in Canada regarding the impact of mask wearing and social distancing (Leonhardt, 2020). Consequently, culture can explicate to some degree why Canada has shown better containment of the spread of the virus.

Of particular importance, individual social responsibility played a key role in triggering bullying. Socially responsible individuals who adhere to mask wearing recommendations expose themselves to unwanted blatantly aggressive verbal comments from bullies. Such inadvertent and uncontainable reactions from bullies can affect the psychological health of targets. In particular, our findings suggest that women can be subjected to such mistreatment. Therefore, the psychological consequences of the pandemic such as victimization are not gender neutral.

5.1. Limitations

We used a cross-sectional design with perceptual measures. Behavioral responses to health and safety measures were inferred from general feelings. The sample is composed of a majority of women living in the United States. A sample composed of a majority of men could yield stronger results concerning the effect of grandiose narcissism. Moreover, a comparison with other countries would enhance knowledge on the role of personality across cultures in predicting adherence to health and safety measures.

5.2. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that personality impacts responses to global threats and public policies. Public policy officials can frame information on threats in a compelling way. However, narcissists are unlikely to comply with public health and safety measures. Bullies are most likely will take advantage of target vulnerability in the context of the pandemic, thereby triggering mental health issues. Public policy officials need to recognize such evidence when designing public policy.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Colleen O'Brien: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration. Louise Tourigny: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Elizabeth H. Manser Payne: Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

We have no known conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Bartley C.E., Roesch S.C. Coping with daily stress: The role of conscientiousness. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50(1):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson C.D., Powell A.A. 2003. Altruism and prosocial behavior. Handbook of psychology; pp. 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Batson C.D., Shaw L.L. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry. 1991;2(2):107–122. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli0202_1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bénabou R., Tirole J. Individual and corporate social responsibility. Economica (London) 2010;77(305):1–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2009.00843.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benson J., Bandalos D.L. Second-order confirmatory factor analysis of the reactions to tests scale with cross-validation. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1992;27(3):459–487. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr2703_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz L., Lutterman K.G. The traditional socially responsible personality. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1968;32(2):169–185. doi: 10.1086/267597. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beus J.M., Dhanani L.Y., McCord M.A. A meta-analysis of personality and workplace safety: Addressing unanswered questions. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2015;100:481–498. doi: 10.1037/a0037916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T., Roberts B.W. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):887. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buelow M.T., Brunell A.B. Facets of grandiose narcissism predict involvement in health-risk behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;69:193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.05.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control . Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021. Frequently asked questions about Covid-19 vaccination.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/faq.html [Google Scholar]

- Cichocka A., Dhont K., Makwana A.P. On self-love and outgroup hate: Opposite effects of narcissism on prejudice via social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. European Journal of Personality. 2017;31(4):366–384. doi: 10.1002/per.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia, C. (2020, October 17). Anti-mask protesters banned from B.C. Ferries for the day after verbally abusing other passengers. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/anti-mask-protesters-cause-disturbance-and-verbally-abuse-passengers-on-b-c-ferry-1.5766903.

- Droms Hatch C., Stephen S.A. Gender effects on perceptions of individual and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Applied Business and Economics. 2015;17(3):63–71. https://libproxy.uww.edu:9443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uww.edu:9443/docview/1727644648?accountid=14791 [Google Scholar]

- Einarsen S. The nature and causes of bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower. 1999;20(1/2):16–27. doi: 10.1108/01437729910268588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons R.A. Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52(1):11. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile B., Miller J.D., Hoffman B.J., Reidy D.E., Zeichner A., Campbell W.K. A test of two brief measures of grandiose narcissism: The narcissistic personality inventory–13 and the narcissistic personality Inventory-16. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25(4):1120–1136. doi: 10.1037/a0033192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough H.G., McClosky H., Meehl P.E. A personality scale for social responsibility. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1952;47(1):73. doi: 10.1037/h0062924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S., Machan L. It's a conspiracy: Covid-19 conspiracies link to psychopathy, Machiavellianism and collective narcissism. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;171:110559. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge T.A., LePine J.A., Rich B.L. Loving yourself abundantly: Relationship of the narcissistic personality to self-and other perceptions of workplace deviance, leadership, and task and contextual performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006;91(4):762. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J., Panagopoulos C., van der Linden S. Political polarization on COVID-19 pandemic response in the United States. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;179 doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanning K., Gough H.G. Shared variance in the California Psychological Inventory and the California Q-Set. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;60(4):596. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt, D. (2020, October 29). Where the Virus is Less Bad, The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/29/briefing/lockdown-france-miles-taylor-early-voting.html.

- Luo J., Roberts B.W. Concurrent and longitudinal relations among conscientiousness, stress, and self-perceived physical health. Journal of Research in Personality. 2015;59:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2015.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum R.C., Austin J.T. Applications of structural equation modeling in psychological research. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51(1):201–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae R., Costa P.T. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2003. Personality in adulthood: A five-factor theory perspective. [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis J.M., Foege W.H. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270(18):2207–2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M.B., Hetland J., Matthiesen S.B., Einarsen S. Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying and psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2012;38-46 doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak B., Brzóska P., Piotrowski J., Sedikides C., Żemojtel-Piotrowska M., Jonason P.K. Adaptive and maladaptive behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of Dark Triad traits, collective narcissism, and health beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;167:110232. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda R., Machii W., Takagi S., Kato Y., Takeda M., Kiyonari T., Hiraishi K. Personality and altruism in daily life. Personality and Individual Differences. 2014;56:206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulhus D.L. Normal narcissism: Two minimalist accounts. Psychological Inquiry. 2001;12(4):228–230. [Google Scholar]

- Penner L.A., Fritzsche B.A., Craiger J.P., Freifeld T.R. In: Advances in personality assessment. Butcher J., Spielberger C.D., editors. vol. 10. 1995. Measuring the prosocial personality; pp. 147–163. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., Mackenzie S.B., Lee J.-Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimah A., Khalil S., Cheng J.M.-S., Tran M.D., Panwar V. Understanding green purchase behavior through death anxiety and individual social responsibility: Mastery as a moderator. Journal of Consumer Behaviour. 2018;17(5):477–490. doi: 10.1002/cb.1733. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raskin R., Terry H. A principal-components analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(5):890. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890. (10.137/0022-3514.5.890) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B.W., Bogg T. A longitudinal study of the relationships between conscientiousness and the social-environmental factors and substance-use behaviors that influence health. Journal of Personality. 2004;72(2):325–354. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B.W., Lejuez C., Krueger R.F., Richards J.M., Hill P.L. What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(5):1315. doi: 10.1037/a0031109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal S.A., Hooley J.M., Montoya R.M., van der Linden S.L., Steshenko Y. The narcissistic grandiosity scale: A measure to distinguish narcissistic grandiosity from high self-esteem. Assessment (Odessa, Fla.) 2019;27(3) doi: 10.1177/1073191119858410. (107319111985841–507) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele W.R., Schreiber G.B., Guiltinan A., Nass C., Glynn S.A., Wright D.J., Garratty G. The role of altruistic behavior, empathetic concern, and social responsibility motivation in blood donation behavior. Transfusion. 2008;48(1):43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strindberg J., Horton P., Thornberg R. The fear of being singled out: Pupils’ perspectives on victimization and bystanding in bullying situations. British Journal of Sociology and Education. 2020;41(7):942–957. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2020.1789846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]