Abstract

Significance:

Glaucoma is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder of the visual system associated with sensitivity to intraocular pressure (IOP). It is the leading irreversible cause of vision loss worldwide, and vision loss results from damage and dysfunction of the retinal output neurons known as retinal ganglion cells (RGCs).

Recent Advances:

Elevated IOP and optic nerve injury triggers pruning of RGC dendrites, altered morphology of excitatory inputs from presynaptic bipolar cells, and disrupted RGC synaptic function. Less is known about RGC outputs, although evidence to date indicates that glaucoma is associated with altered mitochondrial and synaptic structure and function in RGC-projection targets in the brain. These early functional changes likely contribute to vision loss and might be a window into early diagnosis and treatment.

Critical Issues:

Glaucoma affects different RGC populations to varying extents and along distinct time courses. The influence of glaucoma on RGC synaptic function as well as the mechanisms underlying these effects remain to be determined. Since RGCs are an especially energetically demanding population of neurons, altered intracellular axon transport of mitochondria and mitochondrial function might contribute to RGC synaptic dysfunction in the retina and brain as well as RGC vulnerability in glaucoma.

Future Directions:

The mechanisms underlying differential RGC vulnerability remain to be determined. Moreover, the timing and mechanisms of RGCs synaptic dysfunction and degeneration will provide valuable insight into the disease process in glaucoma. Future work will be able to capitalize on these findings to better design diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to detect disease and prevent vision loss. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 37, 842–861.

Keywords: glaucoma, neurodegeneration, synapse, retina, vision, axon, mitochondria

Introduction

Humans rely on vision as their primary means of navigating and understanding the world around them. Vision starts with the detection of photons by rod and cone photoreceptors and depends on numerous steps of parallel processing by neurons and synapses in the retina, subcortical visual structures, and higher-level visual centers in the cortex. Diseases that rob us of our sight do so by preventing the initial detection of photons in our retinas or by disrupting the processing and transmission of information along the visual pathway.

This occurs either via altered function of visual pathway neurons or by degeneration of visual system neurons, thereby short-circuiting the proper flow of visual signals and preventing their processing by downstream visual areas.

The focus of this review is on how retinal neurodegenerative disease alters the structure and function of synapses—points of chemical information transfer between neurons—throughout the visual system. The major emphasis is on glaucoma, an age-related neurodegenerative disease, which is the leading cause of irreversible visual impairment and blindness worldwide. Glaucoma causes vision loss by damage to the optic nerve and degeneration of retinal ganglion cells (RGCs), the output neurons of the retina (21, 69, 173).

Changes in the fidelity of signal transmission across synapses as well as degeneration of pre- and/or post-synaptic structures are common to many neurodegenerative diseases. However, interpreting the interaction of synaptic changes with the degeneration process is challenging as altered functional measures of synaptic transmission (i.e., vesicle release probability, synaptic transmission amplitude, long-term plasticity, postsynaptic receptor changes, endocytosis) might result from either homeostatic plasticity or unchecked synaptic dysfunction. In homeostatic plasticity, neurons attempt to maintain a stable firing rate in response to altered network activity by altering synaptic responsiveness or intrinsic excitability (110, 159).

This contrasts with an unchecked degenerative process, where altered synaptic transmission might be the consequence of dyshomeostasis and pathological loss of synaptic structures and subcellular machinery (91). In this sense, synapse-specific functional changes and the accompanying alterations in neuronal information transmission might serve as useful points for early diagnosis. Alternatively, synaptic dysfunction might be causative for neurodegeneration, in which case understanding and remedying the root causes of the synaptic dysfunction might be a useful avenue for preventing irreversible neuronal loss. Thus, exploration of the specifics of synaptic alterations in glaucoma will be informative for understanding mechanisms and progression of other neurodegenerative diseases.

Synapses and Circuits in the Mammalian Visual System

Retina

The retina (Fig. 1) is a thin piece of the central nervous system (CNS) that lines the back of the eye. It is responsible for detecting photons and performs early stage processing of visual information that is efficiently relayed to the brain (104). Three layers of cells bodies (photoreceptor layer, inner nuclear layer, and ganglion cell layerGCL) are divided by two layers of synapses (outer and inner plexiform layers [OPL and IPL], respectively). Vision begins in the outermost retina and signals are transmitted progressively through each layer of neurons via the synaptic layers until they ultimately leave the eye as trains of action potential carried along the optic nerve, which comprised the axons of RGCs.

FIG. 1.

Neuron types and synapses in the retina. Viewed in cross-section, the retina comprised three layers of cell bodies and two layers of synapses. The PRL contains rod and cone cell bodies whereas the INL contains cell bodies of horizontal cells, ACs, and BCs. The GCL contains RGC bodies as well as numerous AC bodies. The OPL/IPL are sites of synaptic contacts between neurons. The IPL can be further divided into On and Off layers depending on the response polarities of the neurons, making synapses there. For visual signaling, rod and cone photoreceptors make excitatory, glutamatergic synapses onto BCs. Cones signal predominantly in daylight conditions to On and Off CBCs. The CBCs then make excitatory synapses onto RGCs and ACs. The ACs, in turn provide inhibitory signals (via GABA or glycine) onto BCs and RGCs. The RGCs carry the signals to the brain along their axons as trains of action potential. Rods signal predominantly in dim-light conditions and make use of a specialized circuit involving an RBC. The RBC makes an excitatory synapse onto the AII AC, which then passes excitatory signals to On CBCs via a gap junction electrical synapse and to Off CBCs via an inhibitory glycinergic synapse. The purple arrows signify excitatory glutamatergic synapses, whereas the green dashed arrows signify inhibitory synapses (mediated by GABA and glycine). An electrical synapse is signified as a resistor. ACs, amacrine cells; BCs, bipolar cells; CBC, cone bipolar cell; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; PRL, photoreceptor layer; RBC, rod bipolar cell; RGC, retinal ganglion cell.

The RGCs are functionally divided into Off and On types based on the sign of their response to stimuli falling in their receptive fields—the regions of visual space that, when stimulated, evoke a change in RGC firing rate. The dendrites of RGCs cells occupy functionally distinct sub-layers of the IPL, with dendrites from Off-responding RGCs receiving synaptic input from Off-type bipolar cells (BCs) in the outer layers of the IPL and On-responding neuron dendrites receiving input from synapses with On-type BCs. In addition to the On- and Off-IPL lamination, neurons with processes in the middle of the IPL tend to be more transient, whereas those with processes in the peripheral IPL layers (both inner and outer) tend to be more sustained (86).

There have been more than 30 types of RGCs so far identified in mouse retina (8). Why are there so many different types? This is largely because the retina splits vision into distinct and parallel information channels at the level of the BCs (104). The BC signals are then further split as they are conveyed to RGCs, which optimally detect different features of the visual stimulus such as motion, edges, luminance, local contrast, orientation, wavelength, etc. (104). The RGCs of the same type are regularly spaced across the retina so that their dendritic fields “tile” the retina, sampling from regions of the visual field with only enough overlap that optimizes redundancy for signal detection by the RGC array (151).

Different classes of RGCs, however, do overlap with each other so that each point in visual space is sampled by each type of RGC. Dividing the responsibility for different types of visual information to different RGC types allows RGCs to more efficiently convey visual information to the brain, ultimately saving energy (11, 151, 179, 184).

Retinal projections to the brain

The RGC axons comprise the optic nerve and optic tract and terminate in synapses in numerous structures throughout the brain (55, 103, 143). In mammals, the principal projection targets are the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus and the superior colliculus (SC) in the midbrain. The SC serves principally to integrate sensory modalities, especially vision and auditory signals, to drive attention and orienting motor responses such as head or eye movement. As such, it is considered a “reflexive” visual center.

In comparison, the LGN underlies conscious, image-forming vision (82). It receives RGC inputs via excitatory glutamatergic synapses onto thalamocortical (TC) relay neurons—retinogeniculate synapses—and onto a population of GABAergic interneurons. The TC neurons, in turn, relay signals to the primary visual cortex (V1) largely via direct excitatory synaptic inputs to Layer IV, although some TC neurons also signal to other cortical layers.

Glaucoma Is an Age-Associated Neurodegenerative Disease of the Visual System

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide and estimates suggest that >110 million individuals will be affected by the year 2040, with ∼10% of those affected being rendered bilaterally blind (130, 156). Glaucoma is often associated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), which triggers a cascade of degenerative events that ultimately lead to degeneration of RGCs and their projections.

Strong evidence indicates that RGC axons passing through the optic nerve head are the site of injury in glaucoma. This injury has effects that propagate throughout the neurons, in both anterograde (toward the axon terminal) and retrograde directions (toward the soma and dendrites). As studies in animal models have shown, this is in turn associated with dysregulation of axonal mitochondria and metabolism (73), diminished axonal transport (35, 40), altered RGC spiking (9, 134), gliosis (17, 18, 20, 33, 74, 134), and axonal degeneration (26, 74, 139).

Irreversible vision loss arises from optic nerve degeneration and RGC apoptosis. However, it is likely that early stage dysfunction and degeneration of RGC synapses contribute to visual impairment. As discussed later, synapses in the visual system are altered early in the course of the disease. It is unclear whether or to what extent disease-triggered changes in synaptic structure and function are early stage degenerative/pathological events versus whether they are homeostatic attempts by the visual system to preserve vision despite altered neuronal function.

RGC Axonal Injury and Dendritic Remodeling

A considerable body of evidence indicates that loss of synaptic input sites and pruning of RGC dendritic arbors are among the earliest pathological changes in glaucoma and occur well before RGC somatic degeneration (3). For instance, a longitudinal study used in vivo imaging of RGCs in Thy1-Yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) mice for 6 months after an optic nerve crush (ONC) with a confocal laser scanning ophthalmoscope (3, 92). This Thy1-YFP line has the advantage of sparsely labeling RGCs in their entirety so that their entire dendritic fields are labeled with YFP. This study showed that RGCs undergo shrinkage of their dendritic fields before eventual somatic loss.

Another study that used a cross-sectional experimental design analyzed dendrites in isolated retinas with confocal imaging up to 9 days after ONC (80). They found that ONC led to fairly rapid overall diminished RGC dendritic arbors, quantified with a Sholl analysis (which measures dendritic complexity by counting the number of times that rings placed at regular intervals and centered on the soma are each intersected by dendrites), shorter total dendritic length, and fewer dendritic branches. Of course, one challenge of imaging dendrites using approaches such as Thy1-YFP expression is that detected changes in dendrites might arise from altered expression of the YFP reporter rather than dendritic reorganization.

One of the major questions in the field is whether and how different RGC populations might be differentially affected by eye pressure and/or other optic nerve injuries. In an analysis of cat RGCs, Weber and Harman (171) showed that ONC injury led to both a somatic and dendritic atrophy of alpha (α) RGCs, but only somatic atrophy of beta (β) cells. αRGCs (comparable to mammalian parasol cells) have large dendritic fields, whereas βRGCs have smaller fields with more highly branched dendrites. This contrasts with the ONC study in mice by Leung et al. (92), where it was the larger RGC types that appeared to be more resistant to ONC injury. The discrepancy might be the result of species differences, but this has yet to be determined.

It is also important to note that although ONC is commonly used as a way to probe effects of optic nerve injury to elucidate the degenerative processes in glaucoma (23), the time course and extent of the injury is much more dramatic than that which occurs in the “typical” glaucoma. For instance, ONC appears to trigger a Wallerian-type degeneration in which focal axon damage leads to coordinated loss of the distal axon, whereas glaucoma more closely follows a slower “dying-back” process where degeneration originates in distal compartments of the axon and progresses toward the soma (21, 31).

Although there might be some similarities between crush and pressure-induced injuries and their effects on RGCs and their synaptic partners, there is unlikely to be a one-to-one correspondence and comparisons between the two experimental approaches or extrapolation from crush effects to glaucoma pathogenesis need to be carefully caveated.

RGC Synaptic Alterations in Animal Ocular Hypertension Models

Although ONC models attempt to explore the effects of an extreme optic nerve injury, ocular hypertension (OHT)-associated glaucoma is a much slower, more subtle injury process. Still, RGC dendritic remodeling occurs early after IOP elevation, suggesting that this is a common feature of nerve injury and might be among the earliest signs of glaucoma pathology (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

RGC and BC synaptic changes after increased eye pressure. The BCs make excitatory synapses onto RGCs (sites marked with PSD95) with synaptic ribbons. After elevation of eye pressure, RGC dendrites retract and become less complex. In addition, synapses along the RGC dendrites are pruned, as evidenced by a reduced density of PSD95 puncta. Synaptic ribbons are also lost in the IPL, although the loss is more pronounced in the Off sublamina than in the On sublamina in some eye pressure models (13, 31, 104, 119). PSD95, postsynaptic density 95.

After experimentally raising IOP in cats, Shou and colleagues (145) measured somata and dendrites of α- and βRGCs labeled by retrograde transport of horseradish peroxidase from the LGN. They found that dendritic properties (field size, total dendritic length, and dendritic branching) were reduced across the retina for both α and β cells, although the effect was more pronounced for αRGCs and more pronounced with greater distance from the optic nerve head, similar to what was reported for the ONC experiments.

Changes in RGC dendritic structure have also been examined in DBA/2J mice, which is a commonly used mouse model of inherited glaucoma characterized by IOP elevation and progressive RGC degeneration beginning around 6–7 months of age (76, 79, 95). Williams and colleagues (176) used a gene gun to label RGCs in flat-mount DBA/2J retinas with DiI. They found that RGC dendritic field area and the area under the curve of Sholl plots were reduced in DBA/2J mice when compared with controls, but only in retinas that showed optic nerve damage.

Interestingly, when they crossed the DBA/2J mice with Thy1-YFP mice, they found that YFP+ RGCs did not show any dendritic atrophy, a finding that they interpreted to suggest that only healthy RGCs express YFP. It is important to note, however, that the DBA/2J mouse, while commonly used to understand glaucoma pathogenesis and effects of eye pressure, also has numerous other abnormalities, including corneal calcifications, iris synechiae, IOP variability, early onset hearing loss, etc., which may or may not complicate a comparison with human glaucoma (74, 79, 158).

Although the disruption of multiple intracellular signaling pathways likely contributes to RGC dendritic pruning in glaucoma (3), there has been considerable attention paid to the interactions of neuron with glia and the innate immune surveillance system during disease. The complement signaling cascade and microglia are important in synaptic pruning during development and activated during injury (61, 150), when they have been proposed to play a major role in early stage synaptic pathology (152).

In this paradigm, the complement cascade culminates in the tagging of cellular structures by the complement protein C3, which targets those structures for phagocytic digestion by microglia. The complement protein C1q, which is the initiating protein in the “classical” complement cascade, is upregulated and localized to synapses in the IPL in DBA/2J mice and is associated with loss of postsynaptic PSD-95 labeling (152). This likely results from the injury-triggered release of a signaling molecule from reactive astrocytes that, in turn, triggers C1q expression and complement cascade signaling by RGCs. Such a mechanism would be an adult recapitulation of the synaptic refinement and circuit maturation process occurring during development. Elevation of eye pressure leads to microglia activation in the retina and optic nerve (42, 53, 133, 135).

Williams and colleagues found that genetic deletion of the gene encoding the C1q complement protein prevents RGC dendritic atrophy in DBA/2J mice, as does pharmacological inhibition of complement cascade signaling (176). Highlighting the link with RGC degeneration, the extent of RGC loss in aged DBA/2J mice (10 months) was found to correlate with retinal microglia activation measured in those same mice at a younger age (19). In addition, using a gene therapy technique in DBA/2J mice to inhibit complement cascade signaling slows glaucoma progression by preserving RGCs.

This suggests that complement cascade signaling and microglia-dependent synapse elimination, contributing to RGC degeneration. In addition, complement signaling also appears to be important for synaptic refinement of the retinal projection to the dorsolateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) (152), yet it is unclear whether it mediates dendritic remodeling or presynaptic elimination in retinal projection targets in glaucoma.

Recently, the field has sought to determine whether the dendrites across different broad categories of RGCs (i.e., On- vs. Off-RGCs) or even specific members of the 30 or so RGC subtypes are differentially affected in glaucoma (39) (Table 1). Some evidence suggests that Off RGCs are, in general, more susceptible to early dendritic remodeling than On-type RGCs, although this is far from settled. For instance, Della Santina and colleagues used anterior chamber microbead injections in mice and labeled RGC somata and dendrites as well as postsynaptic sites by biolistic transfection with tdTomato- and fluorescently tagged postsynaptic density 95 (PSD95) plasmids (38).

Table 1.

Summary of Retinal Ganglion Cell Dendritic Changes by Retinal Ganglion Cell Subtype in Glaucoma/Elevated Intraocular Pressure

| RGC type | Species | Reference | IOP model | labeling approach | Sholl intersections | Dendritic field area | Total dendritic length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αOn-sus | Mouse | Ou et al. (116) | Laser | Biolistic | Reduced | No change | |

| Mouse | Bhandari et al. (16) | Microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | ||

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | Microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | |

| Mouse | Feng et al. (46) | Laser | SMI-32 Immunostaining | Reduced | |||

| αOff-trans | Mouse | El-Danaf and Huberman (43) | Microbead | Sharp electrode dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Mouse | Ou et al. (116) | Laser | Biolistic | Reduced | Reduced | ||

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | Microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | |

| aOff-sus. | Mouse | Ou et al. (116) | Laser | Biolistic | Reduced | Reduced | |

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | No change | No change | No change | |

| ooDSGC (On dendrites) | Mouse | El-Danaf and Huberman (43) | Microbead | Sharp electrode dye fill | Increased | No change | Increased |

| Mouse | Ou et al. (116) | Laser | Biolistic | No change | |||

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | Microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | |

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | 10-month DBA/2J | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced | |

| ooDSGC (Off dendrites) | Mouse | El-Danaf and Huberman (43) | Microbead | Sharp electrode dye fill | No change | No change | Reduced |

| Mouse | Ou et al. (116) | Laser | Biolistic | Reduced | |||

| Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | Microbead | Patch clamp dye fill | No change | No change | No change | |

| On DSGC | Mouse | El-Danaf and Huberman (43) | Microbead | Sharp electrode dye fill | No change | No change | No change |

| M1 ipRGC | Mouse | El-Danaf and Huberman (43) | Microbead | Sharp electrode dye fill | Reduced | No change | Reduced |

| Rat | Li et al. (94) | Laser | Melanopsin immunofluorescence | No change | |||

| On | Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | 10-month DBA/2J | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Off | Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | 10-month DBA/2J | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| On-Off | Mouse | Risner et al. (134) | 10-month DBA/2J | Patch clamp dye fill | Reduced | Reduced | Reduced |

| Mouse | Feng et al. (46) | Laser | Thy1-YFP | ||||

| Midget | Human | Tribble et al. (157) | Human patient tissue | Serial block face scanning EM | Reduced number and length of dendrites | ||

| Rhesus macaque | Weber et al. (172) | TM lasering | Sharp electrode fill | Reduced (severe glaucoma) | |||

| Parasol | Rhesus macaque | Weber et al. (172) | TM lasering | Sharp electrode fill | Reduced | ||

Dendritic changes are determined from the authors' descriptions and data figures.

IOP, intraocular pressure; M1 ipRGC, M1-type melanopsin-expressing intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell; RGC, retinal ganglion cell; sus, sustained; trans, transient; ooDSGC, On-Off direction-selective retinal ganglion cell; YFP, Yellow fluorescent protein.

PSD95 is a postsynaptic scaffolding protein found at excitatory synapses, which makes it a useful marker for measuring synapse density and loss on neuronal dendrites. They found that although On-sustained αRGCs as well as Off-sustained and Off-transient αRGCs showed a reduced density of PSD95 puncta, only the Off-transient RGCs showed evidence of dendritic atrophy (i.e., smaller dendritic field area, lower overall dendritic length, lower dendritic number, and reduced Sholl intersections).

In a later study, Ou et al. (116) used a similar approach to label RGCs in mice with elevated IOP induced by laser photocoagulation of the episcleral veins, which produces a higher and more transient eye pressure (and is sometimes used as a model for acute angle closure glaucoma). Similar to the microbead approach, they found that elevated pressure led to an earlier and more pronounced reduction in dendritic field area and Sholl intersections for Off αRGCs (although Off-sustained and Off-transient cells seemed similarly affected) than for On αRGCs.

In addition, PSD95 postsynaptic sites were reduced in both On and Off αRGCs. Likewise, Berry et al. (15) used viral injections to express a fluorescently tagged PSD95 in RGCs labeled by SMI32 immunofluorescence staining in DBA/2J mice with severe retinal pathology. SMI32 staining is commonly used as a label of αRGCs in mammalian retinas, and it might have differential labeling efficiency for On-versus-Off and sustained-versus-transient αRGCs (86, 116). They showed that the density of PSD95 puncta was reduced along with the complexity of RGC dendritic arbors.

A study of additional RGC types lends some support to the greater susceptibility of Off RGCs than On RGCs; El Danaf and Huberman (43) combined the microbead OHT approach with transgenic mouse lines in which GFP is expressed in RGC subpopulations to target those RGCs for intracellular dye injection and dendritic analysis. Notably, Off-transient αRGCs showed a reduction in dendritic complexity and dendritic field area as well as a previously un-reported shift in dendritic orientation; although these RGCs typically have a fairly radially symmetrical dendritic field, the dendritic fields after IOP elevation tended to be skewed toward one side.

In addition, On-type direction-selective (DS) RGCs were not affected by elevated eye pressure. The dendritic fields of On-Off DS-RGCs, which have dendrites stratified in both the outer and inner IPL, showed pruning of the Off-stratifying dendrites and increased branching of the On-stratifying dendrites. This is similar in some respects to data from Ou and colleagues (116), where On-Off DS RGCs showed selective pruning only of their Off dendrites, although their On dendrites were not affected by acute pressure elevation.

Ou and colleagues also used staining for synaptic ribbons (which mark excitatory presynaptic sites in BCs) and performed three-dimensional (3D) analysis of ribbon density in the IPL, finding that ribbons were reduced in the Off (outer) IPL, but not the On (inner) IPL (116). This is consistent with studies by Park and colleagues using episcleral vein cauterization in rats to trigger a sustained increase in IOP that showed a decrease in the density of IPL synaptic ribbons in transmission electron microscopy (119, 120). There, increased IOP also led to changes in presynaptic morphology (Fig. 3), including a decrease in synaptic ribbon length and the number of tethered synaptic vesicles, although it also led to an increase in the total number of vesicles present in BC terminals.

FIG. 3.

Presynaptic structural changes in BCs. After IOP elevation, structural changes can be observed in the synaptic terminals of BCs. This includes a shortening of synaptic ribbons, fewer synaptic ribbons, a reduction in the number of presynaptic vesicles tethered to the ribbons, and an increase in the number of untethered ribbons (104, 107). IOP, intraocular pressure.

Western blot analysis of retinal tissue also showed an increase in the synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin. Park et al. also demonstrated an increase in the PSD95 via Western blot, although the interpretation of this finding is uncertain, as studies by Della Santina, Ou, and Berry showed decreases in PSD95 puncta in RGC dendrites (15, 38, 116). PSD95 is also presumably present at BC synapses with amacrine cells and is present presynaptically at photoreceptor synapses in the outer retina (85), both of which might contribute to the changes in total retina PSD95 protein.

The RGCs principally respond to excitatory BC synaptic inputs with a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors. AMPA receptors (AMPARs) are glutamate receptor ion channels that allow depolarizing cations (Na+, K+, and Ca2+) to flow across the membrane after glutamate binding. An RNA editing enzyme, “adenosine deaminases acting on RNA” (ADAR2) mediates a glutamine/arginine editing in the pore region of the GluA2 AMPAR subunit, which decreases permeability to Ca2+ ions, making them calcium-impermeable (64, 99, 180).

Elevation of eye pressure downregulates ADAR2 in RGCs, which leads to a greater Ca2+ permeability AMPARs in RGCs. Such Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors (cp-AMPARs) are more common in development and are important in plasticity. However, excess intracellular Ca2+ is excitotoxic and therefore is closely regulated by a balance of Ca2+ influx pathways, intracellular stores, mitochondrial sequestration, extrusion, and buffering. In an RGC cell culture model, the increased Ca2+ permeability and influx contribute to neuronal death and blockade of cp-AMPARs reduces the number of apoptotic cells (168).

Further supporting differential susceptibilities of RGC populations to the effects of elevated eye pressure, cp-AMPAR expression was increased in some RGC populations (i.e., On-Off and Off RGCs), but decreased in On αRGCs and this appears to correspond to RGC survival (146, 168, 174). The presence of cp-AMPARs also appears to contribute to a more dramatic paired pulse synaptic depression and a decrease in synaptic gain in Off RGCs, by a mechanism that involves postsynaptic Ca2+ ions and endocannabinoid signaling (146). It is possible that stress associated with elevated IOP triggers a reversion to a more plastic state in an attempt to facilitate homeostasis (110), but that doing so inadvertently contributes to RGC degeneration.

In vivo studies have not yet probed whether retinal overexpression of ADAR2 or inhibition of cp-AMPARs is neuroprotective after eye pressure elevation and such studies would be informative in probing a causal link between synaptic alterations and RGC degeneration.

One type of RGC, M1-type melanopsin-expressing cells (ipRGCs, or intrinsically photosensitive RGCs) are unique in that their dendrites stratify in the Off IPL yet they have On-type synaptic responses (41, 68, 124, 142, 178). ipRGCs have received special attention largely due to reports suggesting that they are less prone to degeneration than other RGC populations, including in glaucoma and other RGC injury models (36). Some of this has come from studies of the pupillary constriction in human glaucoma patients, whereas other evidence is based in rodent experimental glaucoma studies (44, 50, 66, 87, 161, 162, 165, 166, 169).

In terms of dendrites, El-Danaf and Huberman showed that these cells had a slight reduction in dendritic complexity in OHT eyes that resulted from reduced dendritic branching and an overall lower dendritic length, but no change in the total area of the dendritic field, indicating that they were somewhat affected (43).

Combined, these findings appear to support a differential effect of OHT and optic nerve injury on Off-stratifying RGCs compared with On RGCs, with possible differences depending on RGC subtype within the broad On/Off categories. Some of the differences in RGC functional and morphological properties are summarized in a recent review by Della Santina and Ou (39). However, such On- versus Off-RGC differences are far from settled. Of note, other rodent studies have provided conflicting results, with Risner and colleagues (134) showing that dendrites of On-sustained αRGCs and Off-transient αRGCs as well as On-stratifying dendrites of On-Off RGCs undergo pruning fairly early after microbead-induced IOP elevation.

In DBA/2J mice, they also showed that On, Off, and On-Off RGC dendritic complexity is reduced at 10 months of age, but not 3 months of age, when compared with C57Bl6 control mice. In addition, Bhandari et al. (16) showed a reduction in the complexity of On-sustained αRGCs and total dendritic length 4–5 weeks after microbead-induced IOP elevation. It is not clear what differences give rise to these effects, although the method and consequent extent of IOP elevation, time point after induction of high IOP, animal age, and/or other factors might contribute. For instance, studies performed by Risner and colleagues (134) were conducted with fairly modest IOP elevations that more closely reflect human glaucoma whereas other studies used manipulations triggering more dramatic and short-term IOP increases (38, 43, 116).

In addition, and as noted earlier, elevated IOP activates complement/microglia signaling pathways that appear to contribute to RGC synaptic pruning and RGC cell body loss. Although inherited and inducible rodent glaucoma models show complement protein increases in the IPL as well as microglia activation in the IPL, they do not appear to localize specifically to Off IPL sublayers (20, 42, 135, 152), as would be expected for a selective targeting of Off RGCs and their dendrites. Whether complement signaling and microglia contribute to On/Off differences in RGC degeneration remains to be determined.

Still, differences in the extent and timing of IOP increases in rodent studies present a major hurdle to understanding how eye pressure affects RGC dendrites and this will require further study to clarify. The consequences of the numerous documented structural changes on RGC function are not always immediately obvious and it remains a challenge to synthesize anatomical and functional studies conducted by using diverse approaches to elevate eye pressure to come to a clear picture of the consequences on RGC function.

In addition, On- versus Off-differences have not been studied in human or primate glaucoma. The 3D electron microscopic reconstructions of human midget RGCs showed that they undergo dendritic pruning in glaucoma (157); although evidence from nonhuman primates indicates that parasol RGCs show dendritic pruning in a manner that corresponds to disease severity, midget RGCs show dendritic pruning only in eyes with the most severe signs of glaucomatous pathology (170, 171). The latter results fit largely within a framework, suggesting that in human and nonhuman primates, larger RGCs—those possessing large cell bodies, dendritic fields, and axons—are prone to earlier degeneration (52, 131, 132), potentially due to the higher energetic demands associated with supporting an extensive dendritic arbor.

It is not currently known whether On- versus Off- RGC populations are differentially affected in human or nonhuman primate glaucoma and this requires further study to determine whether or under what conditions they are similar to rodent models.

RGC Synaptic Function in Glaucoma

The RGC receptive fields are the areas of visual space that, when stimulated, evoke changes in firing rates. These areas are determined by the responses of upstream neurons and their synaptic inputs to RGCs. The RGC receptive fields have a concentric organization, with the excitatory center region corresponding to the RGC dendritic field and an inhibitory surround region determined largely by outer retinal inhibitory feedback circuits.

Using multielectrode array recordings, multiple groups have demonstrated that RGC receptive field properties are altered in mice with elevated IOP. Della Santina et al. reported that the receptive sizes of Off-transient RGCs were reduced, as was the gain of their response after microbead injection and IOP elevation (38). Feng et al. (46) also reported reduced RGC receptive field sizes and lower numbers of visually responsive RGCs. Sabharwal et al. described reduced Off RGC responses and diminished receptive field centers (136). Notably, they also found that On RGCs showed reduced antagonistic receptive field surrounds.

Some of these effects are likely attributable to upstream retinal circuits and inhibitory synapses, as some effects on Off RGCs depended on On-responding pathways. Some of these physiological findings also appear to concur with anatomical studies of RGC dendritic structure, which were discussed earlier. For instance, narrowing of RGC dendritic fields and decreases in either the complexity of the dendrites within the field and/or decreases in the density of postsynaptic sites are largely consistent with the observed physiological changes (15, 38, 116, 134); a reduced dendritic field area might be predicted to reduce the size of receptive field centers, whereas reductions in the numbers of synaptic sites might be expected to alter the gain of RGC responses, consistent with the functional findings.

Risner et al. (134) performed patch clamp recordings from RGCs after microbead-induced IOP elevation, finding that cone-driven On spiking responses of On-Off RGCs were enhanced early after IOP elevation (2 weeks), but they declined after 4 weeks. A similar response profile was seen for Off RGCs. Elevated IOP also led to a decrease in response latency. These effects were largely attributed to changes in intrinsic excitability of RGCs after IOP elevation due to upregulation of NaV1.6 sodium channel expression at the 2-week time point.

By 4 weeks, recordings of BC-driven excitatory synaptic currents in voltage clamp showed some reductions in inputs in the On and Off components of On-Off RGC responses as well as in the Off transient RGC responses. The same was not true for On or Off sustained RGCs, supporting some differential susceptibility of RGCs depending on RGC class. Moreover, RGCs showed an impaired response to rapid puff-application of AMPA at both 2- and 4-week time points, suggesting downregulation of postsynaptic responsiveness independent of any changes localized to the presynaptic BCs. As described earlier, eye pressure also affects the AMPAR complement in RGCs and this contributes to a more pronounced synaptic depression and a reduced synaptic gain of excitatory inputs to Off RGCs (146, 168, 174).

Examining RGC responses under scotopic (rod-driven) conditions, Pang and colleagues performed patch-clamp recordings from BCs, AII amacrine cells, and On and Off RGCs while measuring their responses to photic stimulation (118). They found that both On and Off αRGC responses showed a rightward shift (decreased sensitivity) of their intensity-response profiles after IOP elevation and that this shift appeared to originate at the synapse between rod BCs and AII amacrine cells, a key circuit in the primary rod pathway for carrying rod-driven signals to RGCs.

The exact mechanisms of this change are unclear; although Ou et al. (2016) found a lower density of BC synaptic ribbons in the Off IPL, On IPL ribbons seemed unaffected by elevated eye pressure (116). Park et al. (2014 and 2019) did show some changes in BC ribbons and synaptic terminal architecture that could underlie these changes, although it is not clear from which subregion of the IPL they imaged or what BC populations they were able to analyze (119, 120). Changes could also occur postsynaptically, at the AII amacrine cells.

In general, glycinergic amacrine cells (which includes AII's) have been reported not to degenerate in microbead-induced glaucoma models (4), but little is known about nondegenerative changes to their structure or function.

In one study that used microbead injection to evoke an especially mild IOP elevation (∼3 mmHg), multielectrode array recordings revealed no effect on RGC receptive field center size, although there was a loss of the antagonistic surround in some RGCs (154). There was also a change in some baseline conditions such as a decrease in spontaneous firing rate, similar to other studies (16, 38, 116). Elevated pressure also led to an acceleration of RGC responses, consistent with other multielectrode array and patch-clamp studies (38, 116, 134, 136).

The origins of the acceleration are unclear: Risner and colleagues suggested that the shorter RGC response latency 2 weeks after IOP elevation was likely due to enhancement of RGC Na+ channels, whereas Sabharwal suggested it might arise from a weakening of the relatively slow primary rod pathway, allowing faster retinal circuits to dominate the RGC responses. Of course, both might contribute, as those studies examined RGC responses at different time points after IOP elevation.

Perhaps more applicable to clinical diagnostics, studies have used noninvasive electroretinographic measures to test for inner retinal dysfunction in multiple animal models of OHT and glaucoma. Conventional flash electroretinogram (ERG) recordings are largely considered as a means to measure rod, cone, and BC function, although some flash ERG components such as the oscillatory potentials (OPs), the photopic negative response (PhNR) (129), and positive and negative components of the scotopic threshold response (pSTR, and nSTR, respectively) are tied to inner retinal function. The scotopic threshold response is a biphasic ERG waveform detected at very dim stimulus intensities, whereas the PhNR is a negative peak following the b-wave in cone-dominated stimulus conditions.

The relationship to inner retinal function is based largely on the sensitivity of these components of the ERG to pharmacological treatments targeting RGCs and amacrine cells as well as to ONC experiments that lead to RGC degeneration while sparing the ERG a- and b-waves (108, 140, 147, 188). Holcombe et al. (65) showed that the pSTR was reduced after IOP elevation via episcleral vein cauterization in mice and that these changes preceded RGC degeneration. In mice with microbead-induced OHT, the ERG b-wave was slightly increased compared with controls although the absolute amplitudes of a-waves, pSTR, and nSTR were unchanged.

However, when the authors normalized the data, they found that the pSTR was decreased relative to controls, which was attributed to changes in inner retinal function. Likewise, the b-wave enhancement was interpreted as amacrine cell dysfunction, which might lead to reduced amacrine cell inhibition to BCs, thereby enhancing ERG b-waves (48). A few studies have examined the PhNR in mouse glaucoma models, finding that it is reduced relative to controls after IOP elevation (30, 189). Interestingly, Grillo et al. found that the PhNR was not different between young (4-month-old) and older (11-month-old) DBA/2J mice, although both pSTR and nSTR peaks were reduced, as was one portion of the OP waveform (54).

Correlations of STR with histological assessment of RGC loss in DBA/2J (along with C57Bl6J controls) showed that the pSTR was reduced as animals aged, but that it was more dramatically reduced in DBA/2J mice. In this study, the pSTR changes appeared to be concurrent with RGC degeneration, as indicated by the parallel loss of RGC somata with the pSTR changes (123).

Another in vivo ERG tool, the pattern electroretinogram (PERG) (14), in particular, has received substantial attention as a noninvasive assessment of inner retinal function. The PERG typically uses a contrast-reversing checkerboard stimulus and evokes a three-peaked waveform reflecting inner retinal function (125, 126). In humans, these are termed N35, P50, and N95, which denotes their sign and time postflash. In mice, three peaks of the PERG waveform (N1, N2, and P1 for the first and second negative peaks and the first positive peak) occur at ∼50, 80, and 300 ms.

The PERG is sensitive to pharmacological manipulations of RGC and inner retinal function, optic nerve injury, and ablation of RGC projection targets in the brain (126). PERG amplitudes decline and latencies lengthen in older DBA/2J mice (127, 128). Comparisons of young (2–4 month-old) DBA/2J mice with C57Bl6J and DBA/2JGpnmb+ controls revealed differences in PERG amplitude and latencies (127). Longitudinal experiments with DBA/2J mice showed that PERG amplitudes declined with age, and that the PERG amplitude negatively correlates with IOP (138).

Moreover, a study using young and aged DBA/2J mice in which IOP was regulated by changing how steeply the head was tilted during PERG showed that IOP alters PERG amplitude and manipulations to reduce IOP led to recovery of the PERG (109). Similar results have been found in other mouse and rat glaucoma models (1, 29, 72, 192, 193). Some studies indicate that PERG deficits precede RGC degeneration, whereas others suggest that PERG changes are concurrent with (and possibly result from) ganglion cell loss (13). Studies using DBA/2J mice in combination with in vivo electroretinography should be interpreted with caution since, as noted in the following section, these mice display defects in pupil dilation as well as corneal opacities (74, 79), both of which will affect the true amount of light reaching the retina in those experiments.

Still, given its link to RGC function, as established in animal studies, and its utility in assessing early glaucomatous dysfunction, the PERG has also been employed to understand glaucoma progression in human patients (10). Comparisons of PERG with in vivo measurements of inner retinal thickness with OCT imaging showed that PERG began declining ∼8 years before detectable thinning of the inner retina, suggesting that functional deficits precede structural deficits (7, 12, 109, 126, 177, 192, 193).

Adaptive optics scanning technology, which allows for a very sensitive measurement of subtle retinal structure changes in glaucoma patients (67), might provide more insight into the relative timing of retinal structure and function alterations.

Does Glaucoma Affect Photoreceptor Synapses?

One of the mysteries surrounding retinal pathology in glaucoma has been whether signaling in the outer retina is altered. It is commonly established that the outer retina is unchanged in human glaucoma patients and this is supported by histological studies showing no apparent loss of photoreceptors from human patients and age-matched controls; there is no correlation of glaucoma disease severity (i.e., inner retinal thinning or visual field deficits) with outer retinal thickness or photoreceptor number (81).

This is similar to some findings from primates as well (183). However, there is also evidence for loss of cone opsin but not rhodopsin mRNA in human glaucoma patients and nonhuman primates (122), which might suggest glaucoma-associated changes in opsin expression even without detectable photoreceptor degeneration. There is also some evidence for photoreceptor degeneration in acute angle closure glaucoma (which can cause a fairly rapid-onset and extreme IOP elevation and ischemia) (5, 77, 117), which might represent injury to be more associated with retinal ischemia rather than a slower-moving effect of pressure.

There is some swelling of photoreceptors in human patients, which is mirrored in primates with glaucoma triggered by laser photocoagulation of the episcleral veins (111). One study has also shown some increases in outer nuclear layer thickness measured with spectral domain optical coherence tomography (45). Many of these results appear contradictory, and it will take further study to more carefully probe whether and under what conditions photoreceptors are lost or become dysfunctional in glaucoma patients.

A substantial body of evidence in favor of outer retinal deficits has largely come from studies using the DBA/2J mouse, which develops elevated eye pressure and progressive glaucoma starting around 6 months of age, as noted earlier. For instance, a largely anatomical study of the outer retina documented changes in the structure of photoreceptor synaptic ribbons (49). Usually, rod ribbons are long and thin when viewed in cross-section and plate-like when viewed from their side. In DBA/2J mice, Fuchs and colleagues showed that there was a greater proportion of ribbons that had taken on a club-shaped appearance or apparently disconnected from the presynaptic membrane and taken on a spherical morphology (49).

They also showed some thinning of the OPL and altered ribbon morphology under light microscopy. Some of these changes appeared to occur as early as 2 months of age, which is before DBA/2J mice experience an elevation in IOP or any notable RGC degeneration, raising questions about whether this is truly associated with glaucomatous pathology in these mice or is simply a reflection of strain differences between DBA/2J and the C57Bl6 controls. Age-associated loss of outer retinal neurons has also been documented as early as 3 months of age in DBA/2J mice (47).

Additional supporting evidence for altered outer retinal function comes from ERG studies. In DBA/2J mice, several studies have documented reductions in a-waves (which represent photoreceptor population responses) and b-waves (representing the responses of On BCs). This was the case in 2-year-old DBA/2J mice compared with age-matched C57Bl6 mice (63) as well as in 10-month-old DBA/2J mice compared with C57Bl6 mice (62). In the latter study the authors showed that ERGs were similar at 2 months of age and, although a- and b-waves declined with age in both DBA/2J and C57 mice, the decline was greater in DBA/2J mice.

Notably, the ratio of the b-wave to the a-wave was unchanged, which suggests that the effect on ERG originated in the voltage response of the photoreceptors rather than at the synapse or postsynaptic rod BCs. Another study compared young (4 month) with older (11 month) DBA/2J mice, showing a decline with age (54).

There are several noteworthy caveats to these studies. The first is that controls were probably C57Bl6J mice, which, although they are commonly used as controls for DBA/2J mice, are of a different genetic background, which might very well produce different ERGs. A superior control would be the DBA/2JGpnmb+ mouse (70), which is strain-matched and has a functional copy of the Gpnmb gene that is mutated in DBA/2J and does not develop elevated eye pressure or glaucoma.

An additional complication is that although pupils are typically dilated using topical mydriatics for ERGs, DBA/2J mice have documented pupillary defects such as iris synechiae (irises that stick to the inside of the cornea), leading to poor pupil dilation, or corneal opacities (74, 79), both of which would reduce the amount of light that can reach the retina (79, 158). This would cause an apparent rightward shift in ERG sensitivity corresponding to the reduced pupil area without changing the b/a-wave ratio. This has led some to suggest that ERG assessments in DBA/2J mice (even those designed to probe inner retinal function) are inherently flawed and that any apparent outer retina functional deficits are more likely the result of inadequate pupil dilation (158). Whether this is the case, or whether outer retinal ERG changes in DBA/2J mice result from true outer retinal defects, or possibly some combination, has yet to be resolved.

Degeneration and Dysfunction of RGC Outputs in the Brain

The RGCs are retinal output neurons that carry visual information relatively long distances (on the order of several cm in humans) in the form of trains of action potential. One of the first effects of elevated eye pressure is an inhibition of anterograde axonal transport by RGC axons, which occurs long before any RGC somatic degeneration. Transport to the SC is inhibited in a patchy manner and drops off from portions of the SC with age and increased IOP (35). This likely reflects the sectorial effects of IOP across the retina; RGC degeneration has been reported in patches in human retinas (90) and in wedge-like regions of DBA/2J mouse retinas (76, 141).

Within the nerve itself, RGC axons display fairly early pathology, showing atrophy and degeneration that is accompanied by changes to astrocytes and microglial distribution (17, 18, 32, 33). Similar to the sectorial loss of RGCs in the retina, this appears to follow a regional pattern in the nerve as well (102, 107). Notably, IOP is not the only factor affecting optic nerve pathology, as transport deficits correlate more strongly with age than IOP in DBA/2J mice (40). In contrast, axon loss appears more strictly related to IOP, as demonstrated by correlation of lifetime IOP and optic nerve axon density (74).

This highlights the complex nature of the degenerative process in glaucoma and supports the notion that some facets of the disease might be better understood as “sensitivity to IOP” rather than the result of high eye pressure, per se (21).

Despite the decline in axonal transport and pronounced optic nerve pathology observed in rodent glaucoma models, RGC axon terminals do not degenerate until fairly late in the disease. Crish and colleagues (35) demonstrated this by using a combination of microbead and DBA/2J mouse models and examining anterograde axon transport, axonal pathology, and RGC terminal staining to show that RGC axon terminal degeneration lags other signs of axonal pathology.

This finding was expanded on in a later study using 3D serial block face scanning electron microscopy of the SC, which showed intact presynaptic RGC terminals in the SC in regions with both intact and compromised anterograde transport of 9–14 month-old DBA/2J mice (148). Likewise, Bhandari et al. showed no significant changes in the density of RGC axon terminals labeled with vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGlut2) immunofluorescence staining in the LGN (16), although vGlut2 loss was apparent and correlated with IOP in 9 month-old DBA/2J mice (163).

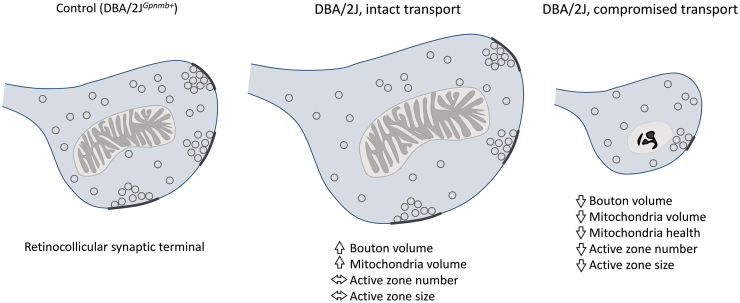

Although RGC axons persist fairly late in glaucoma, Smith et al. showed some structural differences that are likely indicative of early dysfunction (148) (Fig. 4). Capitalizing on the patchy pattern of optic nerve transport deficits to the SC, they examined regions with intact and compromised transport at the ultrastructural level. The RGC axon terminals were enlarged in SC regions with intact transport and slightly atrophied in regions with compromised transport. In contrast, when they explored the morphology of presynaptic active zones—regions of synaptic vesicle fusion—they found that the number and size of active zones were similar in control SC tissue and in regions of the SC with intact transport, but that active zone number and size was reduced in regions with compromised transport. The mitochondria also showed evidence of diminished health in transport-compromised terminals.

FIG. 4.

RGC axon boutons in the SC undergo structural changes in aged DBA/2J mice. Transport along RGC axon boutons is lost in sectors of the SC in aged DBA/2J mice. In regions with intact transport, boutons increase in volume and this is accompanied by an increase in mitochondrial volume. In contrast, in regions showing compromised transport from the retina, there is a reduction in bouton volume, a decrease in mitochondrial volume, and a reduction in the size and number of presynaptic active zones. In addition, a greater proportion of the presynaptic mitochondria show signs of compromised health (129). SC, superior colliculus.

Changes in axon terminal active zone structure and presynaptic mitochondria would be expected to lead to changes in the function of the synapse (83, 91, 141). Synaptic transmission is highly costly from the perspective of cell energetics and synaptic mitochondria are important for (i) supplying ATP to fuel numerous presynaptic processes and (ii) regulating the concentration of presynaptic Ca2+ ions (83, 91, 141). For instance, ATP can be rapidly generated by the combined actions of glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation under conditions of increased energy demand whereas mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is the main ATP source for supporting normal neuronal activity (6, 24, 149, 191).

The ATP is involved in refilling presynaptic vesicles with neurotransmitter, synaptic vesicle priming, endocytic retrieval, and recruitment of reserve supplies of synaptic vesicles to be exocytosed. Moreover, presynaptic vesicle release is triggered by Ca2+ ion influx through voltage-gated Ca2+ channel and interaction with synaptotagmin proteins that bridge the energy barrier for vesicle membrane to fuse with presynaptic terminal membrane. Ca2+ is also involved in regulation of synaptic vesicle endocytosis, vesicle pool refilling (via Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinases as well as other mechanisms), and vesicle priming steps.

Because of its numerous important roles in presynaptic function, [Ca2+] is carefully controlled through a combination of buffering (binding with Ca2+-binding molecules), extrusion (via plasma membrane pumps), and sequestration into intracellular organelles. Mitochondria, along with the endoplasmic reticulum, are the main organelles for Ca2+ sequestration via a mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Mitochondrial localization to the presynaptic terminal is important in regulating Ca2+-related mechanisms of presynaptic homeostatic plasticity (93, 160).

As a result, mitochondrial damage, dysfunction, and diminished anterograde transport in glaucoma are likely to lead to some level of Ca2+ dyshomeostasis and altered energy supply in the synaptic terminal (75, 153), which would lead to disruption of synaptic vesicle release probability, short-term plasticity, vesicle recycling, pool refilling, etc. (77, 83, 91, 141). In addition, impaired retrograde transport by RGC axons in glaucoma (40) is likely to prevent removal of stressed mitochondria from presynaptic terminals (97), further exacerbating synaptic dysfunction.

Beyond mitochondria, disruptions of axonal transport—either kinesin-mediated anterograde transport or dynein-mediated retrograde transport—will deprive presynaptic terminals of components that are necessary for proper function (56). For instance, synaptic vesicle precursors are transported from the soma (112) and loss of this process would be expected to contribute to progressive loss of synaptic vesicle pools. Likewise, alterations in kinesin-dependent voltage-gated ion channel trafficking will alter axonal excitability and/or Ca2+ entry through presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Beyond this, axon terminals are able to maintain function somewhat independently of the soma due to the presence of mRNAs and local protein translation.

However, these mRNA's must be periodically replenished via transport from the soma, a process involving kinesin-dependent transport of mRNA complexed with RNA binding proteins (137), and loss of transport will prevent this replenishment process. Finally, perturbation of dynein-dependent retrograde transport, which occurs at a relatively late stage in glaucoma (40), will prevent removal of degraded and/or misfolded proteins, allowing them to accumulate at the synapse, potentially contributing to synaptic dysfunction and loss (105).

Little is known about how RGC axonal damage or stress influences the synaptic vesicle release process in retinorecipient regions of the brain. Recently, we found that elevation of eye pressure using anterior chamber microbead injections in mice led to an increase in synaptic vesicle release probability at a subset of RGC synapses in the LGN (16) (Fig. 5). These measurements were taken ∼5 weeks after IOP elevation of ∼30% over baseline levels and occurred before major RGC loss. In this case, synaptic vesicle release probability was measured by expressing an optogenetic reporter (channelrhodopsin-2) in a subset of RGCs to activate RGC axons in acute brain slices.

FIG. 5.

Elevated eye pressure leads to pre- and post-synaptic changes at RGC synapses in the LGN. (A) Use of anterior chamber microbead injections to raise eye pressure (OHT) leads to a reduction in the paired pulse ratio of EPSCs evoked by optogenetic stimulation of RGC axons, indicating an increase in synaptic vesicle release probability. (B) Analysis of dendritic structure shows that TC relay neuron in the mouse LGN undergo dendritic pruning in mice with OHT, as assessed with a Sholl analysis (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Adapted from Ben-Shlomo et al. (13). EPSCs, excitatory postsynaptic currents; LGN, lateral geniculate nucleus; OHT, ocular hypertension; TC, thalamocortical.

Both the paired pulse ratio of the responses and the responses to high-frequency stimulus trains indicated an increase in Pr. Although the underlying mechanism for the change is still unknown, it would be consistent with altered presynaptic Ca2+ signals in the terminal due to disrupted mitochondrial function. In the SC, Georgiou et al. have documented that glaucoma leads to changes in responses to activation of a group III metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) expressed on RGC axon terminals that leads to modulation of RGC synaptic output (51).

Notably, elevated IOP also led to pruning of dendrites from relay neurons in the LGN, as measured using a Sholl analysis of the dendritic fields after dye fill in whole-cell patch clamp recordings (16) (Fig. 5). As noted earlier for RGCs, pruning of RGC dendrites is a hallmark of optic nerve injury (3). Animal glaucoma studies have pointed toward a loss of dendritic complexity and general neuronal atrophy (somatic shrinkage) of neurons in central visual targets fairly late in the disease process (25, 57–60, 98, 163, 185–187).

Eventually, glaucoma appears to lead to loss of the postsynaptic neurons in the LGN and SC (190). The changes in the dendritic structure of retinorecipient neurons imply that early stage glaucoma is accompanied by a partial disconnection of RGCs from their postsynaptic targets in the brain and that this might occur quite early in the disease process and contribute to early stage vision loss. Moreover, these findings are notable in that they indicate that the effects of elevated eye pressure extend across the RGC synapse and influence the postsynaptic structure and the function of neurons receiving signals from RGCs (22, 34, 88).

As noted earlier, microglia are involved in synaptic refinement of RGC projections in the dLGN (152), yet it has yet to be determined whether they contribute to pre- or postsynaptic pruning in the dLGN in glaucoma.

Animal studies and work with human patients have also documented functional changes in retinorecipient regions of the brain as well as responses even further down in the visual pathway. For instance, receptive fields of the SC appear to be expanded in rats after IOP elevation (83, 144). Likewise, a modest IOP elevation using a combination of microbeads and episcleral vein cauterization led to a shift in the balance of On and Off responses of SC receptive fields as well as spatial misalignment of the On and Off receptive fields (27). It is unclear whether this receptive field misalignment arises in the SC or results from disrupted receptive field properties of RGCs themselves, although documented evidence for disrupted RGC receptive fields would support a major retinal origin (38, 116, 136).

Origins of RGC and Synaptic Vulnerability in Glaucoma

The visual system is an especially energy-demanding functional unit of the CNS. The RGCs in particular, with their relatively long stretches of unmyelinated axon in the retina and long projections to the brain require substantial energy to convey information in the form of action potentials. As noted earlier, that task is made possible by the division of visual signals into several parallel information streams and selective filtering out of extraneous information.

Still, maintaining relatively high spike rates over long distances requires a steady supply of ATP to reset neuronal ion gradients. The RGCs are believed to be one of the most energetically demanding neuron types in the CNS, and RGCs appear to be especially susceptible to diseases linked to mitochondrial dysfunction. For instance, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy and autosomal dominant optic atrophy are strongly linked to mutations in mitochondrial genes (75, 179, 184).

Although IOP is a major risk factor for glaucoma, age is the biggest risk factor, making glaucoma an age-associated neurodegenerative disease. Age leads to accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations, which impair mitochondrial function (84). In addition, this is compounded when IOP is elevated, as animal studies have shown that experimentally raising IOP leads to accumulation of mtDNA mutations and mtDNA mutations and expression changes are found in aged DBA/2J mice (46, 101, 181).

Mitochondria movement in RGCs is perturbed in animal glaucoma models (153), and measures of ATP production point to a shift toward increased dependence on glycolysis rather than the mitochondria-dependent oxidative phosphorylation (78). Manipulations that preserve mitochondrial function such as taurine treatment, vitamin B3 supplementation, antioxidant treatment, light therapy, or mitochondrial transplantation also have neuroprotective effects in animal glaucoma models and might have potential in slowing glaucoma progression (28, 113–115, 175, 182).

Beyond the fact that proper RGC function places high demands on proper mitochondrial function, synapses are also notably energetically demanding. In presynaptic terminals, a substantial amount of energy is needed to retrieve the synaptic vesicle membrane, refill vesicles with neurotransmitters, maintain synaptic vesicle pools, and tightly regulate presynaptic Ca2+ levels (89, 100, 167). At postsynaptic sites, neurotransmitter molecules gate ion channels that allow for ion flux and changes in postsynaptic membrane potential.

Due to a background amount of spontaneous neurotransmitter release at many synapses, this process is ongoing. The RGCs, for instance, generally rely on a steady tone of excitatory synaptic input that can be modulated up or down to signal increments or decrements of light. Maintaining ionic gradients in the face of this sizeable amount of synaptic drive requires a constant energy supply. Thus, perturbation of mitochondrial function and mitochondrial transport to synapses in glaucoma would be expected to alter synaptic function.

Future Directions

The discussion just cited has focused primarily on the effects of glaucoma and elevated eye pressure on RGC synapses—both the inputs to RGCs from bipolar and amacrine cells in the retina and RGC output synapses. Notably, optic nerve injury and elevated eye pressure appear to trigger changes to the function of RGC synapses in the form of dendritic pruning, rearrangement of the presynaptic BC ultrastructure, and loss of pre- and post-synaptic markers. Less is known about RGC output synapses, although evidence to date indicates that glaucoma and elevated eye pressure alter the structure of presynaptic RGC axon terminals as well as the dendrites of postsynaptic neurons that receive RGC input.

The function of these synapses is also altered and this is likely to be a consequence of the changes in pre- and post-synaptic structure. Synaptic function requires a substantial and dynamic supply of energy in the form of ATP supplied largely by mitochondria present at in pre- and post-synaptic compartments of the RGC. Age and elevated eye pressure lead to mitochondrial gene mutations, structural abnormalities, intracellular transport deficits, and functional impairment that are likely to contribute to the numerous early stage alterations of synaptic function in RGCs and their synaptic partners.

Several key questions remain. Studies to date have indicated that eye pressure selectively affects some RGC populations whereas others are either spared or undergo delayed degeneration. The major conclusions are currently that Off RGCs appear to be more susceptible than On RGCs and that melanopsin-expressing RGCs (ipRGCs) are uniquely resistant to injury. Some data, however, seem to contradict this and/or argue that the situation is quite a bit more nuanced, as discussed earlier. If RGC populations are differentially affected by eye pressure, the mechanism for this also remains to be determined. It is possible that gene expression differences (71, 94), or different complements of synaptic excitatory receptors make some cells less susceptible to degeneration (168).

In addition, differential effects of eye pressure on different populations of RGCs might serve as diagnostic aids. For instance, if glaucomatous degeneration of retinal projections to the brain follows a distal-to-proximal time course of progression, one would expect that deficits in reflexive/orienting eye movements mediated by the SC will precede deficits in conscious vision mediated by RGC synapses in the dLGN. ipRGCs, and the ipRGC-mediated pupillary light reflex in particular, has received special attention due to a fairly clear understanding of the responsible circuit and readily measurable functional output (44, 87).

Of course, one challenge of this is that ipRGCs are reportedly less susceptible to injury and degeneration than other RGC populations (36). Although studies of the susceptibility of different RGC dendrites and somata have received considerable focus, as discussed earlier, less is known about the relative time course of synaptic dysfunction at the multitude of RGC projection targets in the brain.

The details of how elevated eye pressure influences synapses beyond those made by RGCs in the brain remain to be seen. It is already clear that elevated IOP and glaucoma affect the structure and function of relay neurons in the LGN, including somatic and dendritic atrophy. However, it is still unclear whether and how those changes might propagate to other downstream visual regions such as the primary visual cortex and beyond. In addition, can interventions that prevent mitochondrial dysfunction rescue dendritic pruning, early synaptic dysfunction, and synaptic loss?

Finally, one of the major research areas for vision restoration in glaucoma concerns strategies for regenerating RGCs and restoring their synaptic partners in the retina and the brain (164). Modifying mitochondrial oxidative function might also be a promising target for promoting the therapeutic regeneration of RGC axons after glaucomatous damage (37). Specifically, activation of the mTOR pathway (mammalian target of rapamycin) can promote dendritic and synapse regeneration in both in vivo models of optic nerve injury and RGC culture systems (2, 96, 106, 121, 155). This highlights the important links between mitochondrial function and the structure/function of RGC synapses and points toward the cellular functions that can be exploited for therapeutic vision restoration.

Conclusion

Understanding the effects of retinal disease on synaptic microcircuits and single-neuron structure and function is an important foundation for understanding the mechanisms of neurodegeneration and blindness. Glaucoma is a gradual disease and as a result, diagnosis often occurs after irreversible vision loss. Beyond identifying causes of vision loss, research into the cellular and synaptic dysfunction in glaucoma is intended to find earlier and more efficient ways to detect disease and initiate vision-saving treatment before vision loss becomes permanent.

Abbreviations Used

- AC

amacrine cell

- ADAR2

adenosine deaminases acting on RNA

- AMPA

a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- AMPARs

AMPA receptors

- BC

bipolar cell

- CBC

cone bipolar cell

- CNS

central nervous system

- cp-AMPAR

Calcium-permeable AMPA receptor

- dLGN

dorsolateral geniculate nucleus

- DS

direction–selevtive

- EPSCs

excitatory postsynaptic currents

- ERG

electroretinogram

- GCL

ganglion cell layer

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- IOP

intraocular pressure

- IPL

inner plexiform layer

- ipRGC

intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cell

- LGN

lateral geniculate nucleus

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- nSTR

negative component of the scotopic threshold response

- OHT

ocular hypertension

- ONC

optic nerve crush

- OPs

oscillatory potentials

- OPL

outer plexiform layer

- PERG

pattern electroretinogram

- PhNR

photopic negative response

- PRL

photoreceptor layer

- PSD95

postsynaptic density 95

- pSTR

positive component of the scotopic threshold response

- RBC

rod bipolar cell

- RGC

Retinal ganglion cell

- SC

superior colliculus

- TC

thalamocortical

- V1

primary visual cortex

- vGlut2

vesicular glutamate transporter 2

- YFP

Yellow fluorescent protein

Author Disclosure Statement

The author declares no competing commercial or financial interests that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding Information

NIH Grant R01 EY030507; University of Nebraska Collaboration Initiative Seed Grant.

References

- 1. Abdul Y, Akhter N, and Husain S. Delta-opioid agonist SNC-121 protects retinal ganglion cell function in a chronic ocular hypertensive rat model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 1816–1828, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Agostinone J, Alarcon-Martinez L, Gamlin C, Yu W-Q, Wong ROL, and Di Polo A. Insulin signalling promotes dendrite and synapse regeneration and restores circuit function after axonal injury. Brain 141: 1963–1980, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Agostinone J and Di Polo A. Retinal ganglion cell dendrite pathology and synapse loss: implications for glaucoma. Prog Brain Res 220: 199–216, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akopian A, Kumar S, Ramakrishnan H, Viswanathan S, and Bloomfield SA. Amacrine cells coupled to ganglion cells via gap junctions are highly vulnerable in glaucomatous mouse retinas. J Comp Neurol 527: 159–173, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anderson DR and Davis EB. Sensitivities of ocular tissues to acute pressure-induced ischemia. Arch Ophthalmol 93: 267–274, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ashrafi G and Ryan TA. Glucose metabolism in nerve terminals. Curr Opin Neurobiol 45: 156–161, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bach M, Unsoeld AS, Philippin H, Staubach F, Maier P, Walter HS, Bomer TG, and Funk J. Pattern ERG as an early glaucoma indicator in ocular hypertension: a long-term, prospective study. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 47: 4881, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Baden T, Berens P, Franke K, Román Rosón M, Bethge M, and Euler T. The functional diversity of retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. Nature 529: 345–350, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baltan S, Inman DM, Danilov CA, Morrison RS, Calkins DJ, and Horner PJ. Metabolic vulnerability disposes retinal ganglion cell axons to dysfunction in a model of glaucomatous degeneration. J Neurosci 30: 5644–5652, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banitt MR, Ventura LM, Feuer WJ, Savatovsky E, Luna G, Shif O, Bosse B, and Porciatti V. Progressive loss of retinal ganglion cell function precedes structural loss by several years in glaucoma suspects. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54: 2346–2352, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barlow HB. Possible principles underlying the transformations of sensory messages. In: Sensory Communication. Rosenblith WA (ed). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1961, pp. 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayer A, Danias J, Brodie S, Maag K-P, Chen B, Shen F, Podos S, and Mittag T. Electroretinographic abnormalities in a rat glaucoma model with chronic elevated intraocular pressure. Exp Eye Res 72: 667–677, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ben-Shlomo G, Bakalash S, Lambrou GN, Latour E, Dawson WW, Schwartz M, and Ofri R. Pattern electroretinography in a rat model of ocular hypertension: functional evidence for early detection of inner retinal damage. Exp Eye Res 81: 340–349, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Berninger TA and Arden GB. The pattern electroretinogram. Eye Lond Engl 2 Suppl: S257–S283, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berry RH, Qu J, John SWM, Howell GR, and Jakobs TC. Synapse loss and dendrite remodeling in a mouse model of glaucoma. PLoS One 10: e0144341, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bhandari A, Smith JC, Zhang Y, Jensen AA, Reid L, Goeser T, Fan S, Ghate D, and Van Hook MJ. Early-stage ocular hypertension alters retinal ganglion cell synaptic transmission in the visual thalamus. Front Cell Neurosci 13: 426, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bosco A, Breen KT, Anderson SR, Steele MR, Calkins DJ, and Vetter ML. Glial coverage in the optic nerve expands in proportion to optic axon loss in chronic mouse glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 150: 34–43, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bosco A, Inman DM, Steele MR, Wu G, Soto I, Marsh-Armstrong N, Hubbard WC, Calkins DJ, Horner PJ, and Vetter ML. Reduced retina microglial activation and improved optic nerve integrity with minocycline treatment in the DBA/2J mouse model of glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49: 1437–1446, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bosco A, Romero CO, Breen KT, Chagovetz AA, Steele MR, Ambati BK, and Vetter ML. Neurodegeneration severity can be predicted from early microglia alterations monitored in vivo in a mouse model of chronic glaucoma. Dis Model Mech 8: 443–455, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bosco A, Steele MR, and Vetter ML. Early microglia activation in a mouse model of chronic glaucoma. J Comp Neurol 519: 599–620, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Calkins DJ. Critical pathogenic events underlying progression of neurodegeneration in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 31: 702–719, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calkins DJ and Horner PJ. The cell and molecular biology of glaucoma: axonopathy and the brain. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53: 2482–2484, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cameron EG, Xia X, Galvao J, Ashouri M, Kapiloff MS, and Goldberg JL. Optic nerve crush in mice to study retinal ganglion cell survival and regeneration. Bio Protoc 10: e3559, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chamberlain KA and Sheng Z-H. Mechanisms for the maintenance and regulation of axonal energy supply. J Neurosci Res 97: 897–913, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chaturvedi N, Hedley-Whyte ET, and Dreyer EB. Lateral geniculate nucleus in glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol 116: 182–188, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]