Abstract

Introduction

There is limited evidence to guide clinicians on the treatment of psoriasis with biologics in patients with a history of malignancy who are often excluded from clinical trials investigating biologics. The aim of this work is to report a multicenter real-life experience of secukinumab treatment in patients with psoriasis and a personal history of cancer.

Methods

This retrospective observational study included adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis treated with secukinumab for at least 24 weeks and a previous diagnosis of cancer at 15 Italian referral centers. The primary endpoint of the study was tumor recurrence or progression and new cancer diagnosis during treatment. Secondary outcome assessment of secukinumab effectiveness (reduction of Psoriasis Area and Severity Index [PASI] score, improvement of Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI], itch and pain).

Results

Forty-two patients (27 male) were included. Malignancy was diagnosed in the previous 5 years in 21 (56.8%) and in the previous 10 years in 37 (88.1%). The mean interval between cancer diagnosis and the start of secukinumab treatment was 3.5 ± 3.3 years. No tumor recurrence nor progression occurred over a mean of 56 ± 31.7 weeks of treatment. Three patients developed a new malignancy not related to the previous cancer. At week 48, PASI 90 was reached by 64.7% of patients and PASI 100 by 38.2%. Mean DLQI, itch, and pain VAS scores significantly improved during treatment.

Conclusions

Our multicenter real-life experience is the largest reported to date focusing on a specific biologic and adds evidence to the safety of secukinumab in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer.

Keywords: Secukinumab, Psoriasis, Cancer, Biologics

Key Summary Points

| The treatment of psoriasis with biologics in patients with a personal history of cancer is debated, and the evidence available to guide clinicians is limited. |

| We report the largest real-life experience on the use of secukinumab in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer. |

| No tumor recurrence nor progression occurred in our 42 patients over a mean of 56 ± 31.7 weeks of treatment. |

| Considering the absence of cancer recurrence observed in our study and in other case series and the lack of direct association between anti-IL-17 agents and cancer to date, there is no evidence to exclude secukinumab for psoriatic patients with a previous diagnosis of malignancy. |

| Our multicenter real-life experience, which is the largest reported to date focusing on a specific biologic, adds evidence to the safety of secukinumab in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, immune-mediated skin disease with a significant physical and psychological impact that is estimated to affect roughly 3% of the general population in Europe and North America [1].

Psoriasis has been associated with an increased risk of malignancies [2–4]. This association has been partially linked to an underlying immunosurveillance imbalance and chronic inflammation, as well as long-term immunosuppressive treatments and common risk factors such as obesity and metabolic syndrome. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, patients with psoriasis were reported to have an increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) and solid tumors, especially those related to alcohol consumption and smoking [3]. In a large population-based cohort study, the link between psoriasis and cancer was shown to be mainly driven by an increase in NMSC, lymphoma, and lung cancer, and was highest in those with moderate-to-severe psoriasis [2]. More recently, a systematic review and metanalysis, including 112 studies and more than 2 million patients, confirmed a slightly increased risk of keratinocyte cancers and lymphoma in psoriasis patients, but did not demonstrate an increased risk of malignancies among patients with psoriatic arthritis and in those treated with biologic agents [4].

The immune system plays a key role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, with the involvement of both innate and adaptive immune responses [1, 5]. A better understanding of the molecular pathways underlying psoriasis has led to significant advances in the treatment of psoriasis over the past two decades, with the introduction of several biologics [5]. New treatment options targeting the interleukin (IL)–23/Th17 axis have shown greater efficacy than traditional psoriasis drugs and even newer anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α agents [6, 7]. Secukinumab is a humanized anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody indicated for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis. It improves the spectrum of all psoriatic manifestations, showing rapid and sustained responses with a good safety profile [8–11].

The treatment of psoriasis in patients with a personal history of cancer is debated, and the evidence available to guide clinicians is limited. In daily practice, the risk of progression or recurrence should be considered in the treatment decision-making process [12]. In a patient with a current cancer diagnosis or if cancer was diagnosed within the previous 5 years, the EuroGuiDerm guidelines provide a strong recommendation for topical treatment, narrowband UVB phototherapy, and/or acitretin and a weak recommendation for methotrexate, apremilast, and biologic agents inhibiting TNF, IL-12/IL-23, IL-17, IL-23. No specific recommendation is given for dimethyl fumarate in this special class of comorbid psoriasis patients. Treatment decisions should be discussed on a case-by-case basis with a cancer specialist, considering the patient's preferences and psoriasis disease burden [12].

Psoriasis patients with a personal history of malignancy are a special population often excluded from clinical trials investigating biologics. In addition, real-life experiences describing the treatment of such patients with biologics are limited to a few case series [13–16]. Accordingly, the purpose of our study was to report a multicenter real-life experience of secukinumab treatment in adult patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis and a history of cancer.

Methods

Study Design

This retrospective observational multicenter study included adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and a personal history of malignancy, enrolled at 15 Italian referral centers. Eligibility criteria included patients with at least 24 weeks of secukinumab treatment and a diagnosis of cancer before starting secukinumab. Patients with a history of keratinocyte tumors or with unavailable data regarding treatment or cancer were excluded.

We reviewed demographic data (sex, age, body mass index [BMI]) and associated comorbidities of patients, as well as duration and severity of psoriasis, number, and type of previous systemic treatments for psoriasis. Regarding neoplasms, the following data were collected: age at diagnosis, clinical and histological information, stage at diagnosis, type and duration of treatment, presence of any metastases, and interval of metastasis appearance.

The primary endpoint of the study was to evaluate tumor recurrence or progression and new cancer diagnosis during secukinumab treatment. The secondary outcome was the evaluation of secukinumab effectiveness, assessed as the percentage reduction in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score from baseline to weeks 12 and 24 and, for a subset of patients, to weeks 48, 96, and 144. PASI 75, 90, and 100 were also recorded. In addition, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and visual analog scale (VAS) scores were used to analyze the impairment of quality of life and levels of pain and itch, respectively.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Coordinating Centre (L’Aquila) (IRB University of L’Aquila, prot. number 32/2022). Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients according to local regulations.

Statistical Analysis

Variables were evaluated by descriptive statistics, with frequency for categorical variables and mean with standard deviation for continuous variables. Missing data were treated using last observation carried forward data analysis. Statistical differences between variables were calculated using RM one-way ANOVA with the Greenhouse–Geisser correction. Results were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Forty-two patients were recruited for the study, 27 (64.3%) males and 15 (35.7%) females. The mean age at diagnosis of psoriasis was 40.4 ± 12.9. Comorbidities were present in 37 (88.1%) patients, with hypertension being the most common (28/42, 66.7%), followed by dyslipidemia (21/42, 50.0%), diabetes (11/42, 26.2%), and psoriatic arthritis (10/42, 23.8%). The most frequent previous treatment was methotrexate, reported by 80.9% (34/42) of patients, followed by acitretin and phototherapy 50% (21/42), adalimumab 47.6% (20/42), cyclosporine 45.2 (19/42), apremilast 30.9 (13/42), etanercept and infliximab 26.2% (11/42), certolizumab 4.7% (2/42), golimumab and ixekizumab 2.4% (1/42); 30 of 42 (71.4%) patients were bio-experienced. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients included in the study

| Characteristic | Patients N = 42a |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 27 (64.3) |

| Female | 15 (35.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.1 (± 4.5) |

| Any smoking, n (%) | |

| Never | 22 (52.4) |

| Yes | 19 (45.2) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 28 (66.7) |

| Dyslipidemia | 21 (50.0) |

| Diabetes | 11 (26.2) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 10 (23.8) |

| Psychiatric disease | 7 (16.7) |

| Thyroiditis | 7 (16.7) |

| Atopy/allergies | 4 (9.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 (9.5) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 3 (7.1) |

| Neurologic disease | 1 (2.4) |

| Psoriasis characteristics | |

| Age at psoriasis diagnosis, mean ± SD | 40.4 ± 12.9 |

| No. of previous therapies, mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 1.9 |

| Biological therapies, n (%) | |

| Bio-naive | 12 (28.6) |

| Bio-experienced | 30 (71.4) |

| PASI, mean ± SD | 17.2 ± 6.0 |

| DLQI, mean ± SD | 19.5 ± 5.7 |

| VAS pain, mean ± SD | 2.7 ± 3.6 |

| VAS itch, mean ± SD | 6.1 ± 3.3 |

BMI body mass index, PASI Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, VAS visual analogue scale

aNumbers do not always add up to the total due to missing data

All 42 patients reached 24 weeks of secukinumab treatment as an inclusion criterion, 34 of 42 (80.9%) reached 48 weeks, eight (19.0%) patients 96 weeks, and three (7.1%) patients 144 weeks.

Malignancies

The clinical characteristics of tumors and related treatments are detailed in Table 2. Eight (19.0%) patients had a previous diagnosis of melanoma, seven (16.7%) patients each had breast and colorectal cancer, five (11.9%) bladder cancer, five (11.9%) lung cancer, four (9.5%) prostate cancer, three (7.1%) kidney cancer, and one patient (2.4%) each cancer of the uterus, testicle, and lymphoma. Malignancy was diagnosed within the previous 5 years in 21 (56.8%) patients and within the previous 10 years in 37 (88.1%). The mean interval between cancer diagnosis and the start of secukinumab treatment was 3.5 ± 3.3 years. Most cases were early stage cancers, and only two (4.8%) patients had distant metastases (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of tumors and treatment in our cohort of psoriatic patients

| Patients | Sex | BMI | Age at psoriasis diagnosis | Type of cancer | Age at tumor diagnosis | Year at diagnosis | TNM staging classificationa | Adjuvant therapy | Type of therapy | Time between tumor diagnosis and treatment with secukinumab (years) |

Family history of neoplasiab | Diagnosis of new neoplasias during secukinumab treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1c | M | 23.4 | 24 | Melanoma | 60 | 2016 | T2bN0M0 | No | No | 1 | Yes | Small cell lung carcinomad |

| 2 | M | 23.7 | 35 | 51 | 2006 | TisN0M0 | No | No | 10 | Yes | No | |

| 3 | F | 32.8 | 24 | 51 | 2017 | T1bN0M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 4 | M | 28.1 | 62 | 64 | 2011 | T1aN0M0 | No | No | 6 | No | No | |

| 5 | F | 21.3 | 38 | 31 | 2005 | TisN0M0 | No | No | 14 | Yes | No | |

| 6 | M | 24.4 | 35 | 55 | 2015 | T1N0M0 | No | No | 4 | No | No | |

| 7 | M | 28.1 | 35 | 65 | 2018 | T1N1M0 | No | No | 2 | No | No | |

| 8 | F | 32.0 | 50 |

Melanoma 1: 43; Melanoma 2: 60 |

Melanoma 1: 1993; Melanoma 2: 2010 |

Melanoma 1: T2aN0M0; Melanoma 2 T2aN0M0 |

No | No | 8 | No | No | |

| 9 | F | 25.4 | 46 | Breast | 58 | 2012 | T2N0M0 | Yes | Cytotoxic | 6 | No | No |

| 10 | F | 20.7 | 38 | 47 | 2013 | T1bN0M0 | Yes |

Hormonalf Radiotherapy |

4 | No | No | |

| 11 | F | 21.8 | 50 | 75 | 2011 | T2N0M0 | Yes | Radiotherapyg | 7 | No | Breast cancer | |

| 12 | F | 44.1 | 46 | 56 | 2016 | TisN0M0 | Yes |

Hormonalf Radiotherapy |

0 | No | No | |

| 13 | F | 23.5 | 32 | 45 | 2013 | T1N1M0 | No | No | 6 | Yes | No | |

| 14 | F | 30.4 | 49 | 53 | 2018 | T1aN0M0 | Yes | Radiotherapy | 1 | Yes | No | |

| 15 | F | 25.5 | 46 | 45 | 2019 | T2N2M0 | Yes | Radiotherapy | 1 | No | No | |

| 16 | M | 25.2 | 42 | Colon | 45 | 2019 | T2N2M0 | No | Cytotoxic | 1 | No | No |

| 17 | M | 26.5 | 45 | 67 | 2017 | T3N1M0 | No | Cytotoxic | 3 | No | No | |

| 18 | M | 30.1 | 47 | 64 | 2017 | T3N1M0 | Yes | Cytotoxic | 0 | Yes | No | |

| 19 | F | 28.3 | 61 | 61 | 2008 | T2N0M0 | No | No | 9 | No | No | |

| 20 | M | 24.2 | 40 | 60 | 2018 | T1aN0M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 21 | M | 26.5 | 43 | 50 | 2007 | T1N0M0 | No | No | 12 | No | No | |

| 22 | M | 27.4 | 28 | 68 | 2019 | T2N1M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 23 | F | 31.6 | 59 | Lung | 69 | 2018 | T1aN0M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No |

| 24 | M | 29.7 | 47 | 58 | 2012 | T2N1M0 | No | No | 7 | No | No | |

| 25 | M | 23.6 | 36 | 56 | 2018 | T1N1M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 26 | F | 21.3 | 41 | 59 | 2018 | T2aN0M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 27 | M | 26.1 | 23 | 62 | 2018 | T1N2M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 28 | M | 24.3 | 48 | Prostate | 50 | 2016 | pT2cpNxM0 (Gleason score 3 + 3) | No | No | 1 | No | Glioblastomaf |

| 29 | M | 26.9 | 66 | 63 | 2014 | T2cNxMx | No | No | 4 | No | No | |

| 30 | M | 24.3 | 18 | 63 | 2016 | T3aN0M0 | Yes | Radiotherapy | 4 | No | No | |

| 31 | M | 29.4 | 40 | 64 | 2016 | T3N2M1 | Yes | Hormonalh | 3 | Yes | No | |

| 32 | M | 37.6 | 57 | Bladder | 72 | 2019 | T1aN0M0 | No | No | 1 | No | No |

| 33 | M | 24.6 | 57 | 79 | 2017 | TisN0M0 | Yes | Intravesical BCG | 2 | Yes | No | |

| 34 | M | 30.0 | 43 | 70 | 2017 | TaNxM0 | No | No | 2 | No | No | |

| 35 | M | 27.7 | 50 | 64 | 2018 | TisNxM0 | No | No | 1 | No | No | |

| 36 | M | 24.1 | 25 | 37 | 2016 | TaNxM0 | Yes | Intravesical Cytotoxic | 2 | No | No | |

| 37 | M | 25.7 | 31 | Kidney | 61 | 2017 | T1N1M0 | No | No | 2 | No | No |

| 38 | M | 25.5 | 48 | 43 | 2013 | T1aNxM0 | No | No | 5 | Yes | No | |

| 39 | F | 31.6 | 20 | 44 | 2017 | T1aNxM0 | No | No | 2 | No | No | |

| 40 | F | 31.1 | 6 | Uterus | 60 | 2013 | T1aN0M0 | No | No | 6 | No | No |

| 42 | M | 26.5 | 45 | Hodgkin lymphoma | 60 | 2018 | II | No |

Cytotoxic Radiotherapy |

1 | No | No |

| 43 | M | 20.5 | 33 | Testis | 40 | 2018 | T1N1M0 | No | Cytotoxic | 1 | No | No |

BMI body mass index, BCG Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

aPathological stage

bFamily history of malignancy in 1st- or 2nd-degree relatives

cThis patient was previously reported in Odorici et al. 2019 [15]

dSmall cell lung carcinoma diagnosed at 62 years, developed 72 weeks after the start of secukinumab

eBreast cancer diagnosed at 84 years, developed 96 weeks after the start of secukinumab

fAdvanced glioblastoma developed 144 weeks after the start of secukinumab

gThe patient underwent only radiation therapy for personal decision

hThe patient was treated with leuprorelin as therapeutic treatment for metastatic disease

No recurrence of malignancy was detected during secukinumab treatment. No progression of malignancy was observed in the two patients with metastatic disease. Three patients developed a new malignancy during treatment (Table 2). Patient 1 was previously diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma, T2bN0M0, at the age of 60 years, and then developed small cell lung carcinoma 72 weeks after starting secukinumab. Previous treatments included a 3-month treatment period with cyclosporine, 12-month treatment with methotrexate and, as the last treatment before secukinumab, an 18-month treatment with infliximab. Patient 2 was diagnosed with a previous mucinous breast carcinoma (right breast, T2N0M0, ER 90%, PgR 80%, HER2 neu-negative) treated with radiotherapy; the second neoplasia was a ductal breast carcinoma (TisN0M0, ER 0%, PgR 0%) treated with mastectomy and diagnosed 96 weeks after secukinumab initiation. Among previous treatments, she had a 6-month treatment period with cyclosporine and, as the last treatment before secukinumab, a 12-month treatment with adalimumab. Patient 3 had a history of prostate cancer (T2cN0M0) at the age of 50 years and was then diagnosed with advanced glioblastoma 144 weeks after starting secukinumab. Among previous treatments, he underwent a 12-month treatment period with methotrexate as the last treatment before secukinumab.

Effectiveness and Safety of Secukinumab Treatment

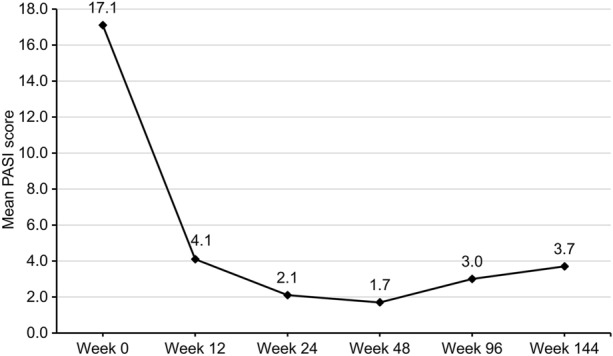

The mean duration of secukinumab treatment was 56 ± 31.7 weeks. Mean PASI score was 17.2 ± 6.0 at baseline, 4.2 ± 3.5 at week 12, 2.1 ± 2.7 at week 24, and 1.7 ± 2.8 at week 48 (p < 0.0001). PASI reduction was 74.7% ± 31.7 at week 12, 88.6% ± 12.8 at week 24 and 91.4% ± 11.3 at week 48. For patients reaching longer timepoints, mean PASI was 3.0 ± 3.5 at week 96 and 3.7 ± 3.2 at week 144. Mean PASI values for each timepoint are shown in Fig. 1. PASI 75, 90, and 100 were achieved by 64.3% (27/42), 28.6% (12/42), and 14.3% (6/42) of patients at week 12, by 88.1% (37/42), 52.4% (22/42), and 37.2% (15/42) at week 24, and by 91.2% (31/34), 64.7% (22/34) and 38.2% (13/34) of patients at week 48, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Mean Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) values for each timepoint

Mean DLQI score was 19.5 ± 5.7 at baseline, 4.1 ± 4.4 at week 12, 1.7 ± 2.2 at week 24, and 1.5 ± 2.2 at week 48 (p < 0.0001). Mean pain VAS was 2.7 ± 3.6 at baseline, 1.6 ± 2.4 at week 12, 0.7 ± 1.9 at week 24, and 1.1 ± 2.6 at week 48 (p = 0.02). Mean itch VAS was 6.1 ± 3.3 at baseline, 1.8 ± 2.4 at week 12, 0.8 ± 1.4 at week 24, and 0.6 ± 2.1 at week 48, (p < 0.0001).

Four patients (4/42, 9.5%) discontinued secukinumab due to lack of efficacy, three patients at week 48, and one at week 96. Treatment was interrupted in the three (7.1%) patients who developed a second malignancy, two at week 96, and one at week 144. Secukinumab was well tolerated and adverse events were rare (3/42 cases; 7.1%)—one case of onset of fibromyalgia and one case of worsening of a previous spongiotic eczema at week 12 and one case of dactylitis at week 48.

Discussion

We report a multicenter real-life experience of secukinumab treatment in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer. No tumor recurrence or progression occurred in our 42 patients over a mean of 56 ± 31.7 weeks of treatment. Three patients developed a new neoplasia not related to the previous malignancy. In addition, our data confirmed the high effectiveness of secukinumab for the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis, with a mean PASI reduction of 91.4 ± 11.3% at 48 weeks and support its favorable safety profile.

A pooled safety analysis of ten phase II/III clinical trials of secukinumab treatment in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis showed a low exposure-adjusted incidence rate (EAIR) of unspecified neoplasms (excluding NMSC) over the 52-week period of treatment (0.48 per 100 subject-years), with no differences between groups of patients exposed to different doses of secukinumab (300 and 150 mg) and comparable EAIR with etanercept-treated patients (0.68 per 100 subject-years) [17]. The EAIR of secukinumab was also comparable with published data for the general population (0.45 per 100 subject-years), and for TNF or IL-12/23 inhibitors (0.36–0.72 per 100 subject-years) [18–20]. More recently, a large integrated safety study including 10,685 psoriatic patients from both clinical trials and post-marketing surveillance provided important long-term data on the risk of all malignancies in patients receiving secukinumab [21]. For the 1250 patients from clinical trials having secukinumab exposure for 5 years, the year-on-year risk for malignancy did not increase over time, and a final cumulative EAIR of 0.83 (per 100 subject-years) was reported, with NMSC being the most common reported cancer (both basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) [21]. The mean time to first malignancy was 1.2 ± 1.3 years. In the 4-year post-marketing surveillance data, the crude cumulative incidence of malignancy was 0.27 per 100 subject-years in the entire cohort of secukinumab-treated psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis [21]. While these data are reassuring, real-world evidence is needed to assess the risk of cancer recurrence in patients with psoriasis and a recent personal history of cancer during treatment with secukinumab, considering that clinical trials have only included patients with a cancer diagnosis at least 5 years prior to study inclusion.

To date, few reports have described real-life experiences of the use of biological drugs in psoriatic patients with a history of malignancy [13–16]. All of these were case series limited in sample size, with a total of 75 cases described, and presented overall data on several classes of biologics, not focusing on a specific drug. Odorici et al. (2019) collected 14 psoriatic patients who initiated or resumed biological therapies after a diagnosis of cancer [15]. No recurrence was observed during a median follow-up of 34 months (range 6–133), while two new tumors, a small cell lung carcinoma, and a multiple myeloma developed in two patients after 18 and 30 months from the start of secukinumab and ustekinumab treatment, respectively. More recently, treatment with different classes of biologics (anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12/23, anti-IL-23, and anti-TNFα) was reported in a case series of 16 psoriatic patients with a diagnosis of cancer within the previous 10 years. The study showed no worsening and reactivation or new diagnoses during the 96-week follow-up of biological therapy [13]. A small monocentric report, focusing on IL-17 inhibitors in patients with psoriasis and previous cancer, described seven patients treated with secukinumab and five with ixekizumab, reporting no recurrence after a median treatment period of 46 months. Progression was observed in two patients with advanced disease [14]. Finally, Mastorino et al. [16] described 37 psoriatic patients, 21 of whom were treated with secukinumab for a mean of 33.1 months after tumor diagnosis. No recurrence was observed, and only one patient with advanced endometrial cancer progressed during secukinumab therapy.

Herein, we report the largest real-life experience on the use of secukinumab in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer. We included patients with a recent history of malignancy, with a median interval between cancer diagnosis and initiation of secukinumab treatment of 3.5 years. The tumor types as well as the early stage of the neoplastic disease were similar to previous case series [13–16]. We observed an absence of recurrence and progression over a mean of 56 ± 31.7 weeks of secukinumab treatment. The rate of new diagnoses was comparable to the published data [13–16]. Three patients developed a second malignancy during treatment, in two cases unrelated to the previous neoplasm. In all three patients, we were able to recognize high-risk factors for cancer development, such as a strong family or personal history of cancer and exposure to environmental risk factors.

Considering the lack of direct association between anti-IL-17 agents and cancer development and the absence of cancer recurrence in population and other case series, to date, there is no evidence to exclude secukinumab for psoriatic patients with a previous diagnosis of malignancy. Indeed, there is increasing evidence that IL-17 inhibition might have a protective role on tumor progression. IL-17 stimulates a proangiogenic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that promotes cell growth and metastasis through induction of inflammatory mediators [22], contributing to the pathogenesis of a wide range of malignancies [23, 24]. This has been recently highlighted in patients treated with chemotherapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors, where IL-17 might drive resistance, thus opening to the addition of anti-IL-17A biologic drugs for overcoming resistance [24].

In psoriasis, the efficacy of IL-17 inhibition has been gradually accumulating, and real-world evidence of secukinumab treatment has confirmed its high effectiveness [25–31]. In a meta-analysis including 43 real-world studies of psoriatic patients treated with secukinumab, PASI 90 were achieved in 50, 53, and 60% of cases at 3, 6, and 12 months, and PASI 100 in 36, 46, and 51% of cases at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively [31]. In our series, at week 48, PASI 90 was reached by 64.7% of patients and PASI 100 by 38.2%. Moreover, in our study, secukinumab was well tolerated with no new or unexpected safety signal.

There are limitations to our study that may affect the generalization of results. The relatively small number of patients and the heterogeneity of cancer types and oncological information did not allow us to statistically analyze data, giving only descriptive information. Due to potential fragmentation and inconsistency of information in clinical records, we decided not to collect and describe patients' history of keratinocytic tumors. In addition, the inclusion of early stage tumors and the short duration of observation might have led us to underestimate the cancer recurrence, although we recognize that our findings are in line with the literature. Nevertheless, our cohort of patients is the largest reported to date and focuses on a single drug, secukinumab, adding evidence to the scarce body of real-life experiences on biologics and the risk of cancer.

Conclusions

Our multicenter real-life experience adds evidence to the safety of secukinumab in psoriatic patients with a personal history of cancer. Further real-life studies with larger populations and longer observation periods are needed to confirm the findings.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study.

Funding

Medical writing assistance was funded by Novartis Farma SpA. Novartis had no involvement in study design, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript preparation and/or publication decisions.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

We thank Ray Hill, an independent medical writer, who provided English-language editing and journal styling prior to submission on behalf of Health Publishing & Services Srl. This assistance was funded by Novartis Farma SpA.

Author Contributions

Study concept and design: Maria Concetta Fargnoli, Maria Esposito, Cristina Pellegrini, Giovanni Schinzari, Ernesto Rossi. Acquisition of data: All authors. Analysis and interpretation of data: Maria Concetta Fargnoli, Cristina Pellegrini, Maria Esposito, Giovanni Schinzari, Ernesto Rossi. Drafting of manuscript: Cristina Pellegrini, Maria Concetta Fargnoli, Maria Esposito. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors besides those drafting the manuscript. Statistical analysis: Cristina Pellegrini. Obtained funding: Maria Concetta Fargnoli. Study supervision: Maria Concetta Fargnoli, Maria Esposito, Cristina Pellegrini

Conflict of Interest

Maria Esposito has served as speaker and/or consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Biogen, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB. Ernesto Rossi has served as a consultant for MSD, Novartis, Pierre Fabre.Paolo Gisondi has been a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sandoz, Sanofi, UCB Pharma.Stefano Piaserico served as advisory board member and consultant and has received fees and speaker's honoraria or has participated in clinical trials for AbbVie, Almirall, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, and UCB Pharma. Paolo Dapavo has been a consultant and/or speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, Leo Pharma, UCB Pharma.Andrea Conti reported personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Janssen Cilag, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Sandoz, UCB Pharma.Martina Burlando acted as speaker for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Leo-pharma, Novartis, UCB Pharma.Alessandra Narcisi has been a consultant for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Boehringer, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB Pharma.Annamaria Offidani has been principal investigator in clinical trials and has been paid as a consultant by AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme.Francesca Prignano served as advisory board member and consultant and has received fees and speaker's honoraria or has participated in clinical trials for AbbVie, Almirall, Biogen Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Janssen, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme. Marco Romanelli received research grants from AbbVie, Almirall, Eli Lilly, Emoled, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Novartis.Maria Concetta Fargnoli has served on advisory boards, received honoraria for lectures and research grants from AMGEN, Almirall, AbbVie, BMS, Galderma, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Pierre Fabre, UCB, Lilly, Pfizer, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Sanofi-Regeneron, Sun Pharma.All the other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Coordinating Centre (L’Aquila) (IRB University of L’Aquila, prot. number 32/2022).Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients according to local regulations.Consent for publication not applicable.

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Cristina Pellegrini and Maria Esposito contributed equally as first authors.

Giovanni Schinzari and Maria Concetta Fargnoli contributed equally as last authors.

References

- 1.Boehncke WH, Schon MP. Psoriasis Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Shin DB, Ogdie Beatty A, Gelfand JM. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the Health Improvement Network. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(3):282–290. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Horreau C, Barnetche T, Misery L, Richard MA, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(Suppl):336–346. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaengebjerg S, Skov L, Egeberg A, Loft ND. Prevalence, incidence, and risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(4):421–429. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylet A, Laclaverie M, Marchand L, Bordes S, Closs-Gonthier B, Delpy L. Immunotherapies in cutaneous pathologies: an overview. Drug Discov Today. 2021;26(1):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger JG, Wharton KA, Jr, Schlitt T, Suprun M, Torene RI, Jiang X, et al. IL-17A inhibition by secukinumab induces early clinical, histopathologic, and molecular resolution of psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(3):750–763. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, Reich K, Griffiths CE, Papp K, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deodhar A, Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Baraliakos X, Reich K, Blauvelt A, et al. Long-term safety of secukinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis: integrated pooled clinical trial and post-marketing surveillance data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(1):111. doi: 10.1186/s13075-019-1882-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab sustains improvement in signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: 2 year results from the phase 3 FUTURE 2 study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56(11):1993–2003. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reich K, Warren RB, Coates LC, Di Comite G. Long-term efficacy and safety of secukinumab in the treatment of the multiple manifestations of psoriatic disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(6):1161–1173. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thaçi D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, Tsai TF, Vanaclocha F, Kingo K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nast A, Smith C, Spuls PI, Avila Valle G, Bata-Csörgö Z, Boonen H, et al. EuroGuiDerm Guideline on the systemic treatment of Psoriasis vulgaris part 2: specific clinical and comorbid situations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35(2):281–317. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valenti M, Pavia G, Gargiulo L, Facheris P, Sanna F, Borroni RG, et al. Biologic therapies for plaque type psoriasis in patients with previous malignant cancer: long-term safety in a single- center real-life population. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1886231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellinato F, Gisondi P, Maurelli M, Girolomoni G. IL-17A inhibitors in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis and history of malignancy: a case series with systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14889. doi: 10.1111/dth.14889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Odorici G, Lasagni C, Bigi L, Pellacani G, Conti A. A real-life experience of psoriatic patients with history of cancer treated with biological drugs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):e453–e455. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mastorino L, Dapavo P, Avallone G, Merli M, Cariti C, Rubatto M, et al. Biologic treatment for psoriasis in cancer patients: should they still be considered forbidden? J Dermatolog Treat. 2021 doi: 10.1080/09546634.2021.1970706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van de Kerkhof PC, Griffiths CE, Reich K, Leonardi CL, Blauvelt A, Tsai TF, et al. Secukinumab long-term safety experience: a pooled analysis of 10 phase II and III clinical studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Cancer Institute Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program. Overview of the SEER program. 2022. http://seer.cancer.gov/about/overview.html.

- 19.Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Gordon K, Lebwohl M, Szapary PO, Wasfi Y, et al. Long-term safety of ustekinumab in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: final results from 5 years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168(4):844–854. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, McIlraith MJ, Lacerda AP. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn's disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(4):517–524. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lebwohl M, Deodhar A, Griffiths CEM, Menter MA, Poddubnyy D, Bao W, et al. The risk of malignancy in patients with secukinumab-treated psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis: analysis of clinical trial and postmarketing surveillance data with up to five years of follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185(5):935–944. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong C. IL-23/IL-17 biology and therapeutic considerations. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5(1):43–46. doi: 10.1080/15476910801897953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blauvelt A, Lebwohl MG, Bissonnette R. IL-23/IL-17A dysfunction phenotypes inform possible clinical effects from anti-IL-17A therapies. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(8):1946–1953. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao J, Chen X, Herjan T, Li X. The role of interleukin-17 in tumor development and progression. J Exp Med. 2020 doi: 10.1084/jem.20190297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carpentieri A, Mascia P, Fornaro M, Beylot-Barry M, Taieb A, Foti C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in patients with moderate-severe psoriasis: a multicenter real-life study. Dermatol Ther. 2020;33(6):e14044. doi: 10.1111/dth.14044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Megna M, Di Costanzo L, Argenziano G, Balato A, Colasanti P, Cusano F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in Italian patients with psoriasis: an 84 week, multicenter, retrospective real-world study. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2019;19(8):855–861. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2019.1622678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ortiz-Salvador JM, Saneleuterio-Temporal M, Magdaleno-Tapial J, Velasco-Pastor M, Pujol-Marco C, Sahuquillo-Torralba A, et al. A prospective multicenter study assessing effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in a real-life setting in 158 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(2):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramonda R, Lorenzin M, Carriero A, Chimenti MS, Scarpa R, Marchesoni A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of secukinumab in 608 patients with psoriatic arthritis in real life: a 24-month prospective, multicentre study. RMD Open. 2021 doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz-Villaverde R, Rodriguez-Fernandez-Freire L, Galan-Gutierrez M, Armario HJC, Martinez-Pilar L. Drug survival, discontinuation rates, and safety profile of secukinumab in real-world patients: a 152-week, multicenter, retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(5):633–639. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thaçi D, Körber A, von Kiedrowski R, Bachhuber T, Melzer N, Kasparek T, et al. Secukinumab is effective in treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: real-life effectiveness and safety from the PROSPECT study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(2):310–318. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustin M, Jullien D, Martin A, Peralta C. Real-world evidence of secukinumab in psoriasis treatment - a meta-analysis of 43 studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(6):1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.