Abstract

Research problem

Real patients living with a disease and engaged in the education of healthcare professionals are referred to by different terms. To address this, A.Towle proposed a draft taxonomy.

Objective

Our objective is to extract from the literature the definitions given for the following terms: (1) patient educator, (2) patient instructor, (3) patient mentor, (4) partner patient, (5) patient teacher, (6) Volunteer Patient in order to clearly identify their roles and level of engagement.

Methods

The literature search was carried out in Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo and Eric by adding medical education or healthcare professional to our previously identified keywords to ensure that it is indeed literature dealing with real patients’ involvement in the education of healthcare professionals.

Results

Certain terms refer to real and simulated patients. Roles are more or less well described but may refer to multiple terms. The notion of engagement is discussed, but not specifically.

Conclusion

Explicitly defining the terms used according to the task descriptions and level of engagement would help contribute to Towle’s taxonomy. Real patients would thus feel more legitimately involved in health professional education.

Abstract

Problème de recherche

Les patients vivant avec une maladie et qui sont impliqués dans l'éducation des professionnels de la santé sont désignés par des termes différents. Pour y remédier, A.Towle a proposé un projet de taxonomie.

Objectif

Notre objectif est d'extraire de la littérature les définitions données pour les termes suivants : (1) patient éducateur, (2) patient instructeur, (3) patient mentor, (4) patient partenaire, (5) patient enseignant, (6) patient volontaire afin d'identifier clairement leurs rôles et leur niveau d'implication.

Méthodes

La recherche documentaire a été effectuée dans Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo et Eric en ajoutant l'éducation médicale ou le professionnel de santé à nos mots-clés précédemment identifiés afin de s'assurer qu'il s'agit bien de littérature traitant de l'implication des patients dans l'éducation des professionnels de santé.

Résultats

Certains termes font référence à des patients ayant une maladie ou simulés. Les rôles sont plus ou moins bien décrits mais peuvent faire référence à plusieurs termes. La notion d'implication est abordée, mais pas de manière spécifique.

Conclusion

Définir explicitement les termes utilisés en fonction de la description des tâches et du niveau d'implication permettrait de contribuer à la taxonomie de Towle. Les patients se sentiraient ainsi plus légitimement impliqués dans la formation des professionnels de santé.

Introduction

Long considered to be passive subjects of examinations by students in university hospital settings, patients are now voluntarily and meaningfully engaged in the education of future healthcare professionals. The development of medical pedagogy has favoured their active involvement in teaching and the term “patient-centered education” is an integral part of the curricula for training healthcare professionals.1,2 However, there is little consensus in the literature on the terms used to refer to these real patients engaged in education. This lack of consensus impacts the research in this field as well as the development of education programs for healthcare professionals. Moreover, this ambiguity has implications for patient safety, since their active participation in medical education could influence their health, depending on the level of their engagement.

In 2010, Towle et al. highlights the paradox of medicine that claims to be patient-centered when, in fact, real patients have little involvement in the management of university hospital environments.2 They emphasize the notion of active participation, synonymous with collaboration between patients and institutions to develop health training programs. They stress the need not to limit the concept to medical studies but to expand it to all healthcare professionals and concludes that there is confusion around terminology that requires a taxonomy. Over time, these notions of active participation or partnership render obsolete the term “Volunteer Patient,” found in the literature prior to the 2000s. This term was most often used to differentiate real patients from simulated or standardized patients who were involved in medical education.3

The terms used then to describe patients living with a disease (real patient) and engaged in education are confusing and impede the implementation of patient-centered education programs. Two levels of confusion appear. First, not all sick people are called “patient” in all professions: sometimes they are clients, service users, and sometimes they are family members of the sick person.4 For the sake of convenience, Towle et al. suggest keeping the term, “patient.”2 Second, the qualifier added to the term “patient” seems to suggest different roles but without a precise definition. “Patient Teacher,” “Patient Educator,” “Patient Instructor,” “Partner Patient” are the terms most often seen in recent publications on patients and health professional education.5,6,7,8,9

The literature review done by Jha et al. focuses primarily on the intervention strategies of real patients. To our knowledge, no literature review has been done on the definition of the qualifiers added to the word “patient” in the context of education. Mougeot et al. presents a narrative literature review on the nomenclature of real patients involved in care.10 They see lexical inflation as a beneficial sign reflecting real patients’ active involvement in care. We can draw a parallel with the involvement of real patients in the education of healthcare professionals. Moreover, in Towle and Godolphin’s taxonomy the terms for naming real patients are not standardized. These authors suggests six different levels of engagement ranging from participation to partnership and which meet different curriculum needs.7 However, a number of similar terms are found at multiple levels, which implies that no one term defines the level of participation. We therefore propose to verify in the literature whether the definition of the various terms cited in Towle and Godolphin’s taxonomy make it possible to clarify the role and level of engagement of real patients.

Our research objectives had two distinct but related parts: (1) Are the definitions found specific enough to differentiate real patients’ roles?; (2) Are the definitions found specific enough to determine real patients’ level of engagement in training institutions?

Methods

We conducted a narrative literature review using Medline, CINAHL, PsychInfo and Eric databases in order to identify literature dealing with “real” patients involved in health professional education. Indeed, as our project was aimed primarily at conducting an update and critique of knowledge related to the specificity of the definition of “real patient” in order to ascertain whether it is inclusive of the patient's role and engagement, a narrative review of the literature is more suitable for this research project. 11, 12 Therefore, we conducted a synthesis of information and discussion on this topic without a systematic and comprehensive review of the literature.

In addition, since our study focused primarily on the definitions of terms described by Towle and Godolphin in their taxonomy of real patients, we included the keywords “Patient Educator,” “Patient Instructor,” “Patient Mentor,” “Patient Partner,” “Patient Teacher,” and “Volunteer Patient.” To ascertain that it is literature related to health education, we added the keywords “medical education” or “healthcare professional” to the search. We adjusted the precise syntax of the sentence to meet the requirements of specific databases and we eliminated keywords that were not identical to those entered in the database. As an example of this, we eliminated the term “standardized patient educator” which implies that these were simulated or standardized patients rather than “real” patients. To be included, the source had to be in English or French and from a journal or conference with evidence of peer review, published between 2000 and 2020. The starting year is 2000 as it corresponds roughly to the year in which we see more and more literature addressing the issue of involving real patients in the training of healthcare professionals. The literature search was conducted between April and August 2020.

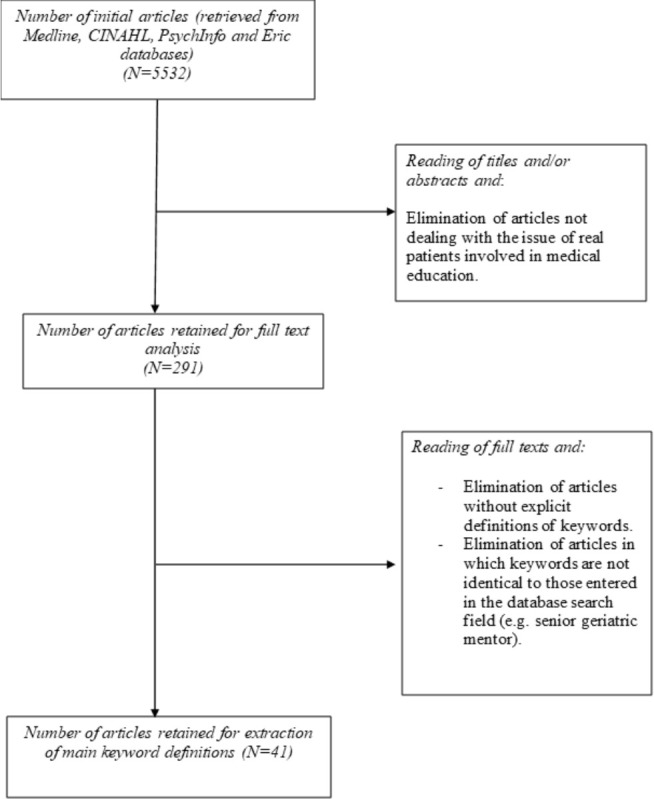

First, we screened the titles and abstracts and then the full text of those articles that remained. Next we extracted the data: the definitions of the main keyword within each of the included articles (Figure1). We then analyzed the data thematically.

Figure 1.

Article selection process

Results

Patient educator

The article selection process yielded 13 articles defining “Patient Educator.” Of these 13 articles, 11 considered the Patient Educator to be a real patient while two considered the “Patient Educator” to be a simulated or standardized patient.13,14 Both Humphrey-Murto et al. and the article “Do you know?” gave a nearly identical definition of “Patient Educator,” that is, a real patient who was trained to teach physical examination to students.15,16 On the other hand, Lauckner et al. and Oswald et al. both defined the “Patient Educator” as someone with a health condition who educates students.17,18 While the other nine articles contained varied definitions, 10 authors mention the involvement of “Patient Educators” in medical education or teaching, and seven authors mention that patients were trained in preparation for their role as “Patient Educator.”

Patient instructor

The article selection process yielded 12 articles defining “Patient Instructor”. Of these 12 articles, seven considered the “Patient Instructor” to be a real patient while six considered the “Patient Instructor” to be a simulated or standardized patient. Hassell, Roberts and Bideau et al. all gave similar definitions of “Patient Instructor”, that is, a patient with a specific illness, such as rheumatoid arthritis, trained to teach history taking and examination in the context of their illness.19,20,21 The definition of “Patient Instructor” appeared in two articles by Henriksen et al. and described a “Patient Instructor” as patients with rheumatism involved in teaching.22,23 Again, the other seven definitions were variable but many contained similar themes. Indeed, across the 12 articles, nine authors mentioned educational involvement and seven authors mentioned that the patients were trained.

Patient teacher

The article selection process yielded six articles defining “Patient Teacher.” Five articles implied or stated that the “Patient Teacher” was a real patient, while one article stated that the “Patient Teacher” could be both a real or role-played patient. Again, few definitions resembled each other; however, several themes arose: five authors mentioned that the “Patient Teacher” had experiential knowledge pertaining to their illness, four authors mentioned that the “Patient Teachers” were involved in teaching or education and three authors mentioned that the “Patient Teachers” were volunteers.

Partner patient

The article selection process yielded seven articles defining “Partner Patient.” All eight articles implied or stated that the “Partner Patient” was a real patient. While few definitions resembled each other, several main themes arose: six authors mentioned “Partner Patient” involvement in education or teaching, four authors mentioned “Partner Patient” involvement in the teaching of musculoskeletal/physical examinations and one author mentioned that “Partner Patients” participated in a training program.

Patient mentor

The article selection process yielded one article defining “Patient Mentor”. The definition implies that the “Patient Mentor” is a real patient and states that their role is to support other healthcare professionals through their knowledge and experience.

Volunteer patient

The article selection process yielded one article defining “Volunteer Patient.” The definition states that “Volunteer Patients” are simulated patients involved in the role play of clinical scenarios designed to educate a variety of healthcare professionals.

Table 1 summarizes the articles selected for each keyword.

Table 1.

Selected articles for each key word

| Key word | References |

|---|---|

| Patient Educator | 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 |

| Patient Instructor | 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 |

| Patient Teacher | 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 |

| Partner Patient | 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50 |

| Patient Mentor | 51 |

| Volunteer Patient | 52 |

Analysis

We analyzed the definitions of the six terms along three axes: Do the definitions found specifically describe who these patients are, what they do and how they do it? In other words, was there clear information on their status, their role, and how they are involved?

Defining patients’ status: simulated patient or real patient?

In health professional education, it is customary to learn from real patients who are people living with a disease and whom students interact with in a clinical setting. Learning is also done with simulated patients to allow students to practice on healthy people without risk of harming them. The definition of the status of these different patients (living with a disease or healthy or simulating) is therefore unequivocal. For “Partner Patient,” “Patient Teacher,” “Patient Mentor” and volunteer patient, the patient’s status is clearly defined: they are real patients.

On the other hand, for “Patient Educator” and “Patient Instructor,” the status is sometimes ambiguous. “Patient Educator” is defined in 11 articles as a person living with a disease, while in two articles this person is described as a simulated patient.

The confusion is more pronounced for “Patient Instructor,” who appears as a real patient as well as a simulated patient. It should be noted that all three authors who consider the “Patient Instructor” as a simulated patient publish in dental education journals, which may suggest the use of this term in a way that is specific to this profession.33,34 There is also an article about a volunteer patient coming to work as a simulated patient.32 It is not possible to determine from the text whether it is a real patient or a healthy person. In this case, it would be wise to use the term “simulated patient instructor” (SP instructor ) in order to limit confusion and specify that the “Patient Instructor” is a real patient who can more or less standardize his or her own history to meet the learning objectives in a simulation context.

In Towle and Godolphin’s classification, the “Patient Instructor” would therefore be involved in levels 1 and 2, focused primarily on learning in a simulation context.7

Defining patients’ role: teacher and evaluator

Five of the six terms are defined by a clinical skill teaching role, whether it is the medical history, communication or physical examinations in the context of their illness. “Patient educator,” “Partner Patient,” and “Patient Teacher” also participate in student evaluations and are invited to give students feedback. In their teaching role, “Partner Patients” are commonly associated with teaching musculoskeletal examinations. Therefore, no precise definitions exist to differentiate between the roles of educator, teacher, and partner. This is in line with the observations made by Jha in a literature review where the author specifies that the terms “Patient Educator” and “Patient teacher” are often interchangeable and that this hinders a precise definition of the role.6

The “Volunteer Patient” also participates in complex roles in the context of learning by simulation. They are therefore close in their role to the “Patient Instructor” and may therefore be found in levels 1 and 2.

The sixth term, “Patient Mentor,” does not meet the definition of clinical skills teacher. It seems to be defined as a support role for various healthcare professionals. It may correspond to Towle and Godolphin’s level 3 and involve participation in mentoring programs.

Defining patients’ mode of intervention

Given that the roles are similar, it is possible that the terms differ according to the methods or context of patient interventions. The sharing of expertise or the experience of living with a disease is a type of intervention frequently described for all except the “Patient Instructor” and the “Volunteer Patient.” All the others teach the patient’s perspective and can give their personal history. There are no details on the strategies used to deliver the material to the students. For all, there is involvement in education but without specifying the level of patient engagement. Only the term “Partner Patient” refers to a collaborative mode that suggests more advanced involvement. Note that this appears in two French-language articles that refer to the Montreal model of partner patients.44,43

It seems therefore that “Patient Educator” and “Patient Teacher” correspond to the same level of involvement, which would correspond to Towle and Godolphin’s level 4.7 This would be consistent with the fact that in the article by Cheng and Towle, the two terms are often interchanged whereas the “Partner Patient,” through a more collaborative intervention, seems to be set apart and on a more institutional level as defined by the Montreal model.8 It would be closer to level 6 and the term “Patient Program Leader” found in Towle’s publication.53

From these results, we see that certain terms correspond to multiple levels, and we can propose a draft patient nomenclature based on Towle and Godolphin’s classification, as describe in Table 2.7

Table 2.

Correspondence between the nomenclature of real patients and Towle’s taxonomy.

| Description | Corresponding Term | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Patients create learning materials |

Patient Instructor

Volunteer Patient |

| 2 | Standardized or volunteer patient in a simulated clinical setting. |

Patient instructor

Volunteer patient |

| 3 | Patient shares his or her experience | Patient Mentor |

| 4 | Patient-teacher(s) are involved in teaching or evaluating students. |

Patient Educator

Patient Teacher |

| 5 | Patient teacher(s) as equal partners in student education, evaluation and. curriculum development. | Partner Patient |

| 6 | Patients involved at institutional level in addition within a faculty-directed curriculum | Patient program leader |

Even without an exact match between the levels and definitions of patient terms, this should help us to more rationally name patients according to their role and their level of involvement in education.

Discussion

Terms to define a function, not a person

There are parallels between the problems faced when defining the role simulated patients and real patients. The adjective associated with the term simulated patient defines a role, a function that helps the SP act according to the expectations of the educational system. In contrast, a real patient might have reservations about being labeled by educational institutions, echoing the paternalism perceived by patient organizations in the healthcare setting.10 If real patients are committed to participating inthe education of health professionals, it is important that they are aware that the terms used do not define them but specify a function and level of commitment, just as with simulated patients or health professionals who intervene in faculties as tutors, educators, trainers, etc. These adjectives do not qualify a person but a function. This clarification should be presented to real patients so that they do not feel affected by a decision made by health professionals, in order to facilitate educational research. Discussions should be held with real patients themselves to improve this terminology.

To train or not to train real patients

Based on our analysis, we can establish connections between roles and level of engagement. (Table 7) Real patients can participate in teaching, but it appears that their participation as assessors requires a higher level of involvement in the curriculum. This means that patient educators, partner patients and patient teachers must be trained to provide feedback or evaluate students. Their involvement is therefore defined by the need to train themselves for these functions. There are mixed views on the need for real patient training, but our research findings invite us to consider the level of engagement to assess the need for training; however, real patient training appears to be an asset to maintaining a viable program, and trainings should be tailored to the level of engagement.7,54

Benefit to real patients

As stated at the outset, the lack of terminology creates confusion in the literature but can also have an impact on real patient safety. Indeed, a high level of engagement in Towle's taxonomy requires the patient to be stable and able, to contribute to the teaching without risk to his or her health. Thus, some patients, because of their medical condition or by choice, might prefer to invest themselves in the first taxonomic levels in order to preserve their health. This notion of freedom seems important to us in order to leave the real patient in control of his life and his choices. Some patients with stabilized chronic diseases would be better candidates to be partner patients (level 5 or 6).

Limitations

Looking for explicit definitions of keywords in titles and abstracts may have minimized the number of relevant articles. This choice to retain only those articles with a specific description was made to avoid making implicit interpretations. On the other hand, the selection having been made solely on the relevance of abstracts, it is possible that explicit definitions appear in the body of articles we did not retain. This explains the small number of articles read compared with the number of articles retrieved from the databases.

We modified the search criteria for “Volunteer Patient” due to the large number of articles found that did not pertain to patients working in the context of medical education. Specifically, the search for “Volunteer Patient” in CINAHL Ebsco originally yielded 3376 articles, of which the vast majority were not related to medical education. The terms patient and volunteer often appeared in the same article, but were rarely, if ever seen in conjunction and referring to a patient implicated in medical education. Therefore we decided to only review articles that contained either “Volunteer Patient” and “Medical Education,” or “Volunteer Patient,” and “Healthcare Professional.” This search yielded a combined 37 articles, which represents a limit to this review as it is possible that some pertinent articles were lost when this restriction was made.

Conclusion

This research confirmed that there are inconsistencies in nomenclature of real patients involved in health professional education. It further clarified the definitions of terms used to refer to patients involved in medical education. This made it possible to contribute to the taxonomy initiated by Towle.7 These data lead us to pursue the project of developing explicit definitions, particularly in the area of real patient engagement in health professional education. We believe that this would facilitate the implementation of patient partnership programs. Furthermore, by accurately naming things we recognize and validate them. In this way, like healthcare professionals and academics, real patients will have and feel they have legitimacy to teach in institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Funding

None

References

- 1.Pomey MP, Flora L, Karazivan P, et al. Le «Montreal model»: Enjeux du partenariat relationnel entre patients et professionnels de la santé. Sante Publique (Paris). 2015;27:S41–50. 10.3917/spub.150.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towle A, Bainbridge L, Godolphin W, et al. Active patient involvement in the education of health professionals. Medical Education.2010;44(1): p. 64–74. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokken L, Rethans JJ, Scherpbier AJJA, Van Der Vleuten CPM. Strengths and weaknesses of simulated and real patients in the teaching of skills to medical students: A review. Simulation in Healthcare. 2008.3(3): p. 161–9. 10.1097/SIH.0b013e318182fc56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello J, Horne M. Patients as teachers? An evaluative study of patients’ involvement in classroom teaching. Nurse Educ Pract. 2001;1(2):94–102. 10.1054/nepr.2001.0014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vail R, Mahon-Salazar C, Morrison A, Kalet A. Patients as teachers: An integrated approach to teaching medical students about the ambulatory care of HIV infected patients. Patient Educ Couns. 1996;27(1):95–101. 10.1016/0738-3991(95)00793-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jha V, Quinton ND, Bekker HL, Roberts TE. Strategies and interventions for the involvement of real patients in medical education: a systematic review. Med ed. 2009;43(1). p. 10–20. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03244.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Towle A, Godolphin W. Patients as teachers: promoting their authentic and autonomous voices. Clin Teach. 2015. J;12(3):149–54. 10.1111/tct.12400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng PTM, Towle A. How patient educators help students to learn: An exploratory study. Med Teach. 2017. Mar 4;39(3):308–14. 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1270426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med. 2015;90(4) p. 437–41. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mougeot F, Robelet M, Rambaud C, et al. Emergence of the patient-actor in patient safety in France. A narrative review in social sciences and public health. Sante Publique. 2018;30(1):73–81. 10.3917/spub.181.0073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saracci C, Mahamat M, Jacquérioz F. Comment rédiger un article scientifique de type revue narrative de la littérature ? Rev Med Suisse. 2019; 15(664): 1694-1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demiris G, Oliver D, Washington K. Defining and Analyzing the Problem 3.1 INTRODUCTION.Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care. 2019; 27-39. 10.1016/B978-0-12-814449-7.00003-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oswald AE, Bell MJ, Wiseman J, Snell L. The impact of trained patient educators on musculoskeletal clinical skills attainment in pre-clerkship medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1):65. 10.1186/1472-6920-11-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen SS, Miller J, Ratner E, Santilli J. The educational and financial impact of using patient educators to teach introductory physical exam skills. Med Teach. 2011;33(11):911–8. 10.3109/0142159X.2011.558139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Do you know? Med Teach. 2004;26(6):579–80. 10.1080/01421590400012257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Humphrey-Murto S, Smith CD, Touchie C, Wood TC. Teaching the Musculoskeletal Examination: Are Patient Educators as Effective as Rheumatology Faculty? Teach Learn Med. 2004;16(2):175-180. 10.1207/s15328015tlm1602_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauckner H, Doucet S, Wells S. Patients as educators: the challenges and benefits of sharing experiences with students. Med Educ. 2012;46(10):992–1000. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oswald A, Czupryn J, Wiseman J, Snell L. Patient-centred education: what do students think? Med Educ. 2014;48(2):170–80. 10.1111/medu.12287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bideau M, Guerne PA, Bianchi MP, Huber P. Benefits of a programme taking advantage of patient-instructors to teach and assess musculoskeletal skills in medical students. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(12):1626–30. 10.1136/ard.2004.031153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassell A. Patient instructors in rheumatology. Med teach. 2012;34(7): p. 539–42. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.678425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts TE. Delivering tomorrow’s curriculum. Med teach. 2012;34(7): p. 519–20. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.689449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henriksen A-H, Ringsted C, Henriksen A-H, Ringsted ÁC, Ringsted C. Medical students’ learning from patient-led teaching: experiential versus biomedical knowledge. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2014;19:7–17. 10.1007/s10459-013-9454-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henriksen A-H, Ringsted C. Learning from patients: students’ perceptions of patient-instructors. Med Educ. 2011;45(9):913–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fong S, Tan A, Czupryn J, Oswald A. Patient-centred education: How do learners’ perceptions change as they experience clinical training? Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;24(1):15–32. 10.1007/s10459-018-9845-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renard E, Alliot-Licht B, Gross O, Roger-Leroi V, Marchand C. Study of the impacts of patient-educators on the course of basic sciences in dental studies. Eur J Dent Educ. 2015;19(1):31–7. 10.1111/eje.12098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oswald AE, Wiseman J, Bell MJ, Snell L. Musculoskeletal examination teaching by patients versus physicians: How are they different? Neither better nor worse, but complementary. Med Teach. 2011;33(5). 10.3109/0142159X.2011.557412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coret A, Boyd K, Hobbs K, Zazulak J, Mcconnell M. Patient narratives as a teaching tool: a pilot study of first-year medical students and patient educators affected by intellectual/developmental disabilities. Teach Learn Med. 2018;30(3):317-327. 10.1080/10401334.2017.1398653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solomon P. Student perspectives on patient educators as facilitators of interprofessional education. Med Teach. 2011;33(10):851–3. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.530703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hedge N, Pickens N, Neville M. A model of clinical reasoning: what students learn from patient educators. Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(Suppl. 1):6911510136p1. 10.5014/ajot.2015.69s1-po4082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdoolraheem MY, Zeina M. A perspective on simulated patients’ and patient-educators’ teaching of communication skills. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1097–1097. 10.1111/medu.13646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krautter M, Diefenbacher K, Schultz J-H, et al. Physical examination skills training: Faculty staff vs. patient instructor feedback—A controlled trial. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e180308. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martineau B, Mamede S, St-Onge C, Rikers RMJP, Schmidt HG. To observe or not to observe peers when learning physical examination skills; That is the question. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13(1):55. 10.1186/1472-6920-13-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner J, Arteaga S, D’Ambrosio J, et al. Dental Students’ Attitudes Toward Treating Diverse Patients: Effects of a Cross-Cultural Patient-Instructor Program. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(10):1128–34. 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2008.72.10.tb04590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broder HL, Janal M. Promoting Interpersonal Skills and Cultural Sensitivity Among Dental Students. J Dent Educ. 2006;70(4):409–16. 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2006.70.4.tb04095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yudkowsky R, Downing S, Klamen D, Valaski M, Eulenberg B, Popa M. Assessing the head-to-toe physical examination skills of medical students. Med Teach. 2004. Aug;26(5):415–9. 10.1080/01421590410001696452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaworsky D, Gardner S, Thorne JG, et al. The role of people living with HIV as patient instructors–reducing stigma and improving interest around HIV care among medical students*. AIDS Care-Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2017. Apr 3;29(4):524–31. 10.1080/09540121.2016.1224314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broder HL, Janal M, Mitnick DM, Rodriguez JY, Sischo L. communication skills in dental students: new data regarding retention and generalization of training effects. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(8):940–8. 10.1002/j.0022-0337.2015.79.8.tb05985.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aires MJ, Gagnayre R, Gross O, et al. The patient teacher in general practice training: perspectives of residents. J patient Exp. 2019;6(4):287–95. 10.1177/2374373518803630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roussel J-C. Le “patient formateur”, ou comment enseigner son propre vécu. Soins.2008;51(702):55-56.SOIN-11-2006-00-710-0038-0814-101019-200608990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lown BA, Sasson JP, Hinrichs P. Patients as partners in radiology education: an innovative approach to teaching and assessing patient-centered communication 1. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(4):425. 10.1016/j.acra.2007.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fiddes PJ, Brooks PM, Komesaroff P. The patient is the teacher: ambulatory patient-centred student-based interprofessional education where the patient is the teacher who improves patient care outcomes. Intern Med J. 2013;43(7):747–50. 10.1111/imj.12197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Towle A, Bainbridge L, Farrell C, et al. Where’s the patient’s voice in health professional education? Conference presentations. Nurse Educ Pract. 2006;6(5):300–2. 10.1016/j.nepr.2006.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lai MMY, Martin J, Roberts N. Improving ambulatory patient-centred practice with a patient teaching associate programme. Intern Med J. 2015;45(8):883–4. 10.1111/imj.12813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young K, Kaminstein D, Olivos Aet al. Patient involvement in medical research: What patients and physicians learn from each other. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):21. 10.1186/s13023-018-0969-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goulet M-H, Larue C, Chouinard C. Partage du savoir experientiel: regard sur la contribution des patients partenaires d’enseignement en sciences infirmieres. Sante Ment Que. 2015;40(1):53-66. 10.7202/1032382ar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lierville Christine Grou Jean-François Pelletier A-L . Enjeux éthiques potentiels liés aux partenariats patients en psychiatrie : état de situation à l’institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal. 2015;40(1):119-134. 10.7202/1032386ar [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dahrouge S, James K, Gauthier A, Chiocchio F. Engaging patients to improve equitable access to community resources. CMAJ. 2018;190(S1): p. S46–7. 10.1503/cmaj.180408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morin M-P, Schneider R, Martimianakis T, Bowen F, Mylopoulos M. A141: Active engagement of teens with juvenile idiopathic arthritis in medical education: what do they think their contribution might be? Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:S184–S184. 10.1002/art.38562 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murphy RF, LaPorte DM, Wadey VMR. Musculoskeletal education in medical school: Deficits in knowledge and strategies for improvement. J Bone Jt Surg. 2014;96(23):2009–14. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barr J, Bull R, Rooney K, Barr J, Rooney ÁK, Bull R. Developing a patient focussed professional identity: an exploratory investigation of medical students’ encounters with patient partnership in learning. Adv Heal Sci Educ. 2015;20:325–38. 10.1007/s10459-014-9530-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anderson ES, Ford J, Thorpe L. Perspectives on patients and carers in leading teaching roles in interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2019;33(2):216-225. 10.1080/13561820.2018.1531834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Webster BJ, Goodhand K, Haith M, Unwin R. The development of service users in the provision of verbal feedback to student nurses in a clinical simulation environment. 2011; 32(2):133-138. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Towle A, Godolphin W. Patients as educators: Interprofessional learning for patient-centred care. Med Teach. 2013;35(3):219–25. 10.3109/0142159X.2012.737966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pageau S, Burnier I, Fotsing S. Stratégies de recrutement et de formation des patients en éducation: une synthèse de la littérature. Pédagogie Médicale. 2021;22(2):91–100. 10.1051/pmed/2021008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]