Abstract

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery are the options for revascularization in coronary artery disease (CAD). This meta-analysis aims to compare the efficacy of CABG and PCI for the management of patients with CAD. The meta-analysis was conducted as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE were searched for relevant articles. The reference list of included articles was also searched manually for additional publications. Primary endpoints were cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints included myocardial infarction, stroke, and revascularization. In total, 12 randomized control trials (RCTs) were included in this meta-analysis encompassing 9,941 patients (4,954 treated with CABG and 4,987 with PCI). The analysis showed that PCI was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality (risk ratio (RR) = 1.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.10-1.45) and revascularization (RR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.82-3.21). However, no significant differences were reported between two arms regarding cardiovascular mortality (RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.96-1.39), myocardial infarction (RR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.82-1.67), and stroke (RR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.35-1.16). CABG was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality and revascularization compared to PCI. However, no significant difference was reported in the risk of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke between the two groups.

Keywords: efficacy, meta-analysis, coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass graft surgery, percutaneous coronary intervention

Introduction and background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major cause of mortality worldwide [1]. The complexity and severity of CAD can vary among patients. CAD can involve a single vessel and can impact various territories such as multivessel coronary disease. CAD can also impact arteries with little to no clinical significance or arteries vital to the survival and function of the left ventricle, including the left main coronary artery. For the past several years, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been the standard of care for invasive treatment of left main and multivessel CAD, considering its extensive advantage in survival [2]. However, in the last few decades, rapid advancements have been made in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including pharmacotherapy, adjunctive imaging support, and stent technology [2]. These have enhanced the surgical approach to the treatment of CAD. Based on the results of small randomized control trials (RCTs) [3,4], with the above-mentioned technical and pharmacological advancements, the value of PCI in the treatment of CAD is still being explored. RCTs including NOBLE [3] and Excel [4] trials have added some uncertainty to this vital topic.

Currently, and with large numbers of RCTs being performed among patients with multivessel and left main artery CAD, the choice of suitable coronary artery revascularization strategy remains unclear [5]. RCTs by Head et al. (2014) and Farkouh et al. (2012) [6,7], along with large retrospective studies [8,9], have all reported consistent findings preferring CABG over PCI for long-term benefits. The NOBLE trial showed that in individuals with left main CAD [3], PCI was less effective than CABG, while the Excel trial showed non-inferiority of PCI compared to CABG [4]. The results of these trials are different because of their different methodologies, and, therefore, their results need to be interpreted with caution.

A suboptimal outcome was obtained following PCI in individuals with a high-risk profile who were ruled inoperable for CABG. Patients who cannot undergo PCI because of the complexity of CAD benefit greatly from bypass surgery [10]. The study by Kappetein et al. found that patients with a complex disease have a greater risk for major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with PCI, making CABG the preferred treatment option [11]. In left main CAD, CABG can significantly reduce major cardiac-related events compared to PCI [12].

The recommendations for PCI are somewhat weaker despite the fact that more recent data indicate that PCI may sometimes produce results that are comparable to, if not better than, CABG [3]. Nowadays, most patients prefer a less invasive approach. Moreover, robust data are important for the facilitation of appropriate choices for individual patients. Since the current recommendations were issued, numerous clinical trials comparing PCI and CABG in various patient subgroups have been performed. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a current meta-analysis that takes this data into account. This meta-analysis aims to compare the efficacy of CABG and PCI for the management of patients with CAD. This meta-analysis analyzed the complete spectrum of stable and unstable coronary syndromes across a gamut of different subgroups of patients.

Review

Methodology

This meta-analysis was conducted as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

Two reviewers independently searched electronic databases from inception to August 1, 2022, including PubMed, Cochrane Library, and EMBASE without putting restrictions on the year of publication and language. The reference lists of included articles were also searched manually for additional publications. Keywords used to search for relevant articles were “coronary artery bypass graft,” “percutaneous coronary intervention,” and “coronary artery disease.” This meta-analysis includes RCTs that compared PCI and CABG for the management of CAD in the presence of left main CAD, multivessel CAD, or both. Observational studies, cross-over trials, and reviews were excluded from this meta-analysis. Second, we excluded studies that compared CABG or PCI along with medical therapy and excluded studies that compared two forms of CABG and that compared two forms of PCI.

Two authors reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles independently, followed by full-text screening, as required for determining whether the studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Conflicts between authors were resolved through discussion and re-review.

Outcome Measures

The primary endpoints were cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. Secondary endpoints included myocardial infarction, stroke, and repeat revascularization. Only studies with a minimum follow-up of one year were included.

Quality Assessment

The risk of bias assessment of each included study was done by two authors independently using the criteria defined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The risk of bias was assessed in the following six domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other biases. Each domain was graded as high, low, or unclear for each of the included studies. Conflicts between authors were resolved through discussion and re-review.

Data Extraction

Two review authors extracted study characteristics from included studies using pre-designed data collection forms. The following data were extracted from each of the included studies: the first author, year of publication, sample size, follow-up duration, patient gender, patient age, percentage of patients with diabetes, hypertension, baseline SYNTAX score, and outcomes. Conflicts between authors were resolved through discussion and re-review. One author transferred the data into the Review Manager File for analysis, and one author double-checked whether the data was put correctly by comparing it with the completed data collection form.

Statistical Analysis

Dichotomous data were presented as risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) using the Mantel-Haenszel model. The extent of heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistics and Cochran Q test. I2 values of 0-25%, 25-50%, and 75-100% denote low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. If there was evidence for homogenous effects across trials (I2 <50%), we used RR to analyze the data and the fixed-effects model to summarize all results. If we discovered significant levels of heterogeneity, as shown by a high I2 statistic value of at least 50%, we used the random-effects model. Publication bias for each of the outcomes was assessed using Egger’s test. Stratified analyses were done for early-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) and bare-metal stents (BMS) or newer-generation DES, and for left main CAD and multivessel CAD. Early generation DES included sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents, while newer generation DES included everolimus-eluting and zotarolimus-eluting stents. For a subgroup analysis of studies, data for primary outcomes (all-cause mortality and cardiac-related death) were extracted to calculate RR. Analysis was performed using Review Manager version 5.4.1 (Cochrane, London, UK) and STATA version 16.0 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

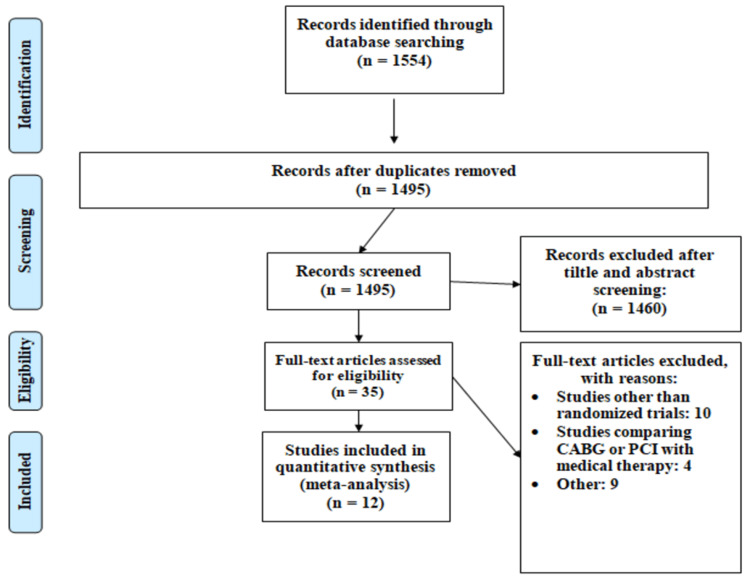

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart of the selection of studies. Out of a total of 1,554 articles resulting from the initial database literature search, 1,495 articles were retrieved for abstract and title analysis. Among 1,495 articles, the full text of 35 articles was accessed to assess eligibility. In total, 12 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. These RCTs enrolled a total of 9,941 patients, of whom 4,954 were assigned to CABG and 4,987 were assigned to PCI. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the included studies.

Table 1. Characteristics of the included studies.

CAD: coronary artery disease; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

| Author | Year | Setting | Population | Groups | Sample size | Follow-up period |

| Boudriot et al. [13] | 2011 | Multicenter | Left main CAD with or without multivessel CAD | PCI | 100 | 1 year |

| CABG | 101 | |||||

| Booth et al. [14] | 2008 | Multicenter | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 488 | 6 years |

| CABG | 500 | |||||

| Buszman et al. [15] | 2008 | Single center | Left main CAD with or without multivessel CAD | PCI | 52 | 1 year |

| CABG | 53 | |||||

| Farkouh et al. [7] | 2012 | Multicenter | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 953 | 5 years |

| CABG | 947 | |||||

| Hueb et al. [16] | 2009 | Single center | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 205 | 10 years |

| CABG | 203 | |||||

| Kamalesh et al. [17] | 2013 | Multicenter | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 101 | 2 years |

| CABG | 97 | |||||

| Kapur et al. [18] | 2010 | Multicenter | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 256 | 1 year |

| CABG | 248 | |||||

| Kumar et al. [19] | 2020 | Single center | Multivessel coronary disease | PCI | 103 | 1 year |

| CABG | 107 | |||||

| Mäkikallio et al. [3] | 2016 | Multicenter | Patients with left main CAD | PCI | 592 | 5 years |

| CABG | 592 | |||||

| Park et al. [20] | 2011 | Multicenter | Left main CAD | PCI | 300 | 2 years |

| CABG | 300 | |||||

| Serruys et al. [21] | 2009 | Multicenter | Left main and/or three-vessel disease | PCI | 891 | 1 year |

| CABG | 849 | |||||

| Stone et al. [4] | 2016 | Multicenter | Patients with left main CAD | PCI | 948 | 3 years |

| CABG | 957 |

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of selection of studies.

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

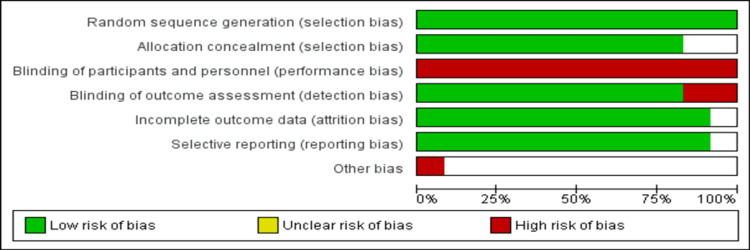

Nine studies were multicenter [3,4,7,13,14,17,18,20,21]. The follow-up of included RCTs ranged from one year to ten years. Figure 2 represents the risk of bias of the included studies. Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias, and it was found to be consistent. The overall study quality was good.

Figure 2. Graph showing the risk of bias.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of patients enrolled in RCTs included in this meta-analysis. The pooled mean age of patients was 62.88 years. Patients enrolled were mainly males (75.9%). More than one-third of the participants were diabetic (44.2%), and nearly two-thirds of patients had hypertension (65.14%).

Table 2. Characteristics of participants.

*: Mean (standard deviation)

UK: not given in the article; CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention

| Author | Groups | Age* | Male n (%) | Diabetes n (%) | Hypertension n(%) | Baseline SYNTAX score* |

| Boudriot et al., 2011 [13] | PCI | 66 (8.1) | 72 (72) | 40 (40) | 82 (82) | UK |

| CABG | 69 (7.4) | 78 (77) | 33 (33) | 83 (82) | UK | |

| Booth et al., 2008 [14] | PCI | 61 (9.2) | 390 (80) | 68 (13.9) | 212 (43) | UK |

| CABG | 62 (9.5) | 392 (78) | 74 (14.8) | 235 (47) | UK | |

| Buszman et al., 2008 [15] | PCI | 60.6 (10.5) | 31 (60) | 10 (19) | 39 (75) | 25.2 (8.7) |

| CABG | 61.3 (8.4) | 39 (73) | 9 (17) | 37 (70) | 24.7 (6.8) | |

| Farkouh et al., 2012 [7] | PCI | 63.2 (8.9) | 698 (73.2) | 953 (100) | UK | 26.2 (8.4) |

| CABG | 63.1 (9.2) | 658 (69.5) | 947 (100) | UK | 26.1 (8.8) | |

| Hueb et al., 2009 [16] | PCI | 60 (9) | 138 (67) | 47 (23) | 125 (61) | UK |

| CABG | 60 (9) | 146 (72) | 59 (29) | 128 (63) | UK | |

| Kamalesh et al., 2013 [17] | PCI | 62.7 (7.1) | 100 (99) | 101 (100) | 97 (96) | 21.5 (8.9) |

| CABG | 62.1 (7.4) | 96 (99) | 97 (100) | 90 (95.7) | 22.7 (10.6) | |

| Kapur et al., 2010 [18] | PCI | 64.3 (8.5) | 181 (70.7) | 256 (100) | 196 (76.6) | UK |

| CABG | 63.6 (9.1) | 197 (77.9) | 248 (100) | 203 (80.6) | UK | |

| Kumar et al., 2020 [19] | PCI | 59 (9) | 64 (62) | 21 (20) | 45 (44) | UK |

| CABG | 59 (10) | 65 (61) | 22 (21) | 46 (43) | UK | |

| Mäkikallio et al., 2016 [3] | PCI | 66·2 (9·9) | 476 (80) | 86 (15) | 386 (65) | 22·5 (7·5) |

| CABG | 66·2 (9·4) | 452 (76) | 90 (15) | 389 (66) | 22·4 (8·0) | |

| Park et al., 2011 [20] | PCI | 61.8 (10) | 228 (76) | 102 (34) | 163 (54.3) | UK |

| CABG | 62.7 (9) | 231 (77) | 90 (30) | 154 (51.3) | UK | |

| Serruys et al., 2009 [21] | PCI | 65.2 (9.7) | 681 (76.4) | 228 (25.6) | UK | 28.4 (11.5) |

| CABG | 65 (9.8) | 670 (78.9) | 209 (24.6) | UK | 29.1 (11.4) | |

| Stone et al., 2016 [4] | PCI | 66 (9.6) | 722 (76.2) | 286 (30.2) | 703 (74.2) | 20.6 (6.2) |

| CABG | 65.9 (9.5) | 742 (77.5) | 268 (28.0) | 701 (73.2) | 20.5 (6.1) |

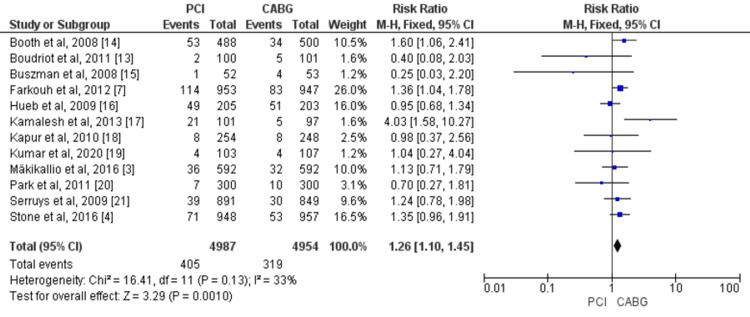

All-Cause Mortality and Cardiovascular Mortality

Overall, 12 studies assessed all-cause mortality by enrolling 9,941 patients (4,954 treated with CABG and 4,987 with PCI) [3,4,7,13-21]. The pooled data of included studies revealed that the risk of all-cause mortality was significantly higher in patients treated with PCI compared to CABG (RR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.10-1.45). No significant heterogeneity was found among the study results (p-value = 0.13, I2 = 33%), as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Pooled risk for all-cause mortality with PCI versus CABG.

Sources: References [3,4,7,13-21].

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

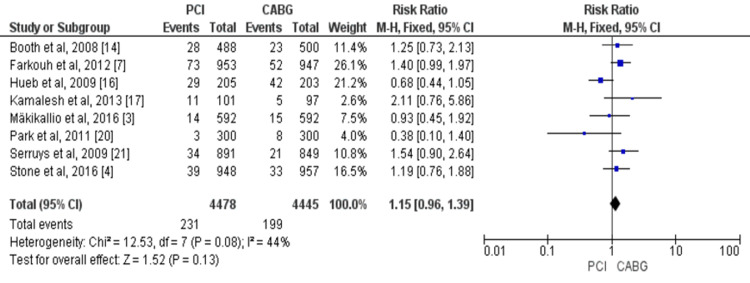

No significant difference was found between CABG and PCI regarding cardiovascular mortality (eight studies, 8,923 patients; RR = 1.15, 95% CI = 0.96-1.39). Significant heterogeneity was found among the study results (p-value = 0.08, I2 = 44%), as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Pooled risk for cardiac-related mortality with PCI versus CABG.

Sources: Reference [3,4,7,14,16,17,20,21].

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Myocardial Infarction, Stroke, and Revascularization

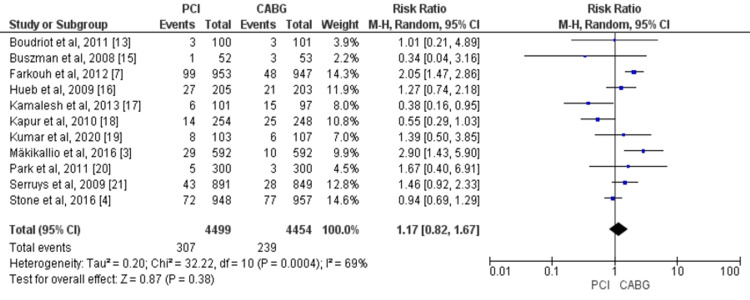

Overall, 11 studies compared the risk of myocardial infarction between two study groups including 8,953 patients with CAD (4,499 in the PCI group and 4,454 in the CABG group) [3,4,7,13,15-21]. Myocardial estimates from the random-effect model showed no significant difference in myocardial infarction between the PCI and CABG arm (RR = 1.17, 95% CI = 0.82-1.67, I2 = 69%), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Pooled risk for myocardial infarction with PCI versus CABG.

Source: References [3,4,7,13,15-21].

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

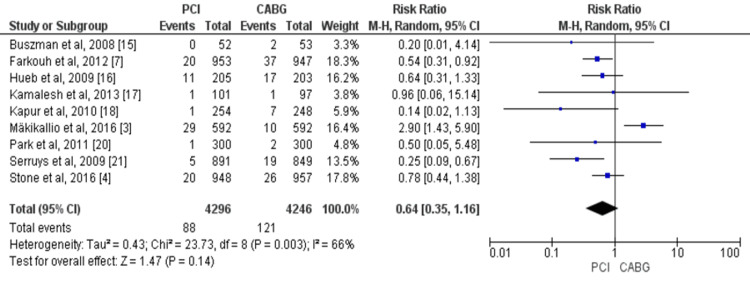

Overall, nine studies compared the risk of stroke in patients between two study groups [3,4,7,15-18,20,21]. There was a trend of excess strokes with CABG compared to PCI, but this difference was not statistically significant (RR = 0.64, 95% CI = 0.35-1.16, I2 = 66%), as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Pooled risk for stroke with PCI versus CABG.

Source: References [3,4,7,15-18,20,21].

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

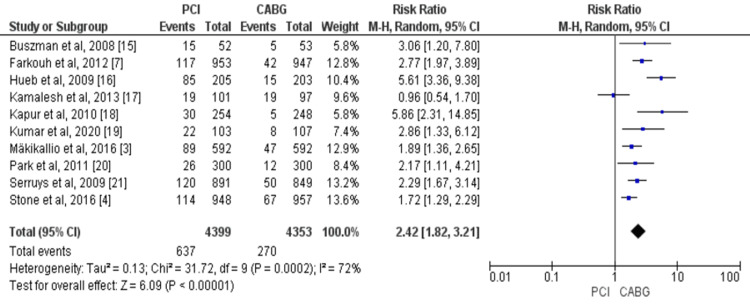

Overall, 10 studies compared the risk of revascularization in patients treated with PCI and those treated with CABG enrolling a total of 8,752 patients with CAD [3,4,7,15-21]. The risk of revascularization was significantly higher in the PCI group compared with CABG (RR = 2.42, 95% CI = 1.82-3.21, I2 = 72%), as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Pooled risk for revascularization with PCI versus CABG.

Source: References [3,4,7,15-21].

CABG: coronary artery bypass graft; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

Subgroup Analysis

Regarding all-cause mortality, a statistically significant difference was observed across multiple subgroups (Table 3). In the subgroup of BMS or early-generation DES (four studies, RR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.07-1.56) and studies with multivessel CAD (four studies, RR = 1.28, 95% CI = 1.06-1.54). No significant interaction was noted in these stratified analyses as the p-value was more than 0.05.

Table 3. Results of the subgroup analysis.

*: Significant at p-values <0.05.

DES: drug-eluting stents; BMS: bare-metal stents; CAD: coronary artery disease; RR: risk ratio; CI: confidence interval

| Outcomes | Subgroups | Number of studies | Total patients | RR (95% CI) | I2 |

| All-cause mortality | BMS or early-generation DES | 3 | 2,748 | 1.29 (1.07-1.56)* | 0% |

| DES | 4 | 5,190 | 1.02 (0.78-1.33) | 0% | |

| Left main CAD | 5 | 3,995 | 1.13 (0.88-1.46) | 26% | |

| Multivessel CAD | 4 | 3,506 | 1.28 (1.06-1.54)* | 20% | |

| Cardiovascular mortality | BMS or early-generation DES | 3 | 2,748 | 0.84 (0.41-1.72) | 72% |

| DES | 3 | 4,989 | 1.26 (0.98-1.63) | 0% | |

| Left main CAD | 3 | 3,689 | 0.96 (0.59-1.55) | 33% | |

| Multivessel CAD | 3 | 3,296 | 1.06 (0.67-1.68) | 70% | |

| Revascularization | BMS or early-generation DES | 3 | 2,748 | 3.03 (1.65-5.54)* | 52% |

| DES | 2 | 3,089 | 1.79 (1.44-2.23)* | 0% | |

| Left main CAD | 4 | 3,794 | 1.87 (1.53-2.29)* | 0% | |

| Multivessel CAD | 2 | 618 | 4.26 (2.21-8.18)* | 42% |

Regarding cardiovascular mortality, consistent findings were observed in the subgroup of second-generation DES (three studies, RR = 1.26, 95% CI = 0.98-1.63) and BMS or early-generation DES (three studies, RR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.41-1.72) and in studies with left main CAD (three studies, RR = 0.96, 95% CI = 0.59-1.55) and multivessel CAD (three studies, RR = 1.06, 95% CI = 0.67-1.68).

Discussion

This meta-analysis of 12 RCTs compared long-term outcomes of PCI and CABG for the management of CAD. Based on pooled data from 12 RCTs that included a total of 9,941 patients, of whom 4,954 were assigned to CABG and 4,987 assigned to PCI, we found that PCI was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and repeat revascularization compared to CABG. However, the overall risk of cardiac death, stroke, and myocardial infarction was similar between PCI and CABG. Stratified analysis showed that increased risk for all-cause mortality associated with PCI was only evident in patients with BMS and early-generation DES and multivessel CAD.

Unlike previous systematic reviews and meta-analyses that focused on PCI and CABG in patients either with left main CAD or multivessel CAD [22,23], this meta-analysis aimed to analyze the complete spectrum of unstable and stable syndromes across a range of patient subgroups.

With the advancement of the PCI, such as the design of stents, higher-risk patients with more complex coronary lesions have been included in trials [24]. As such, we found relative mortality benefits of CABG over PCI in this study, especially in patients with multivessel CAD. The findings of this meta-analysis are in line with short-term outcomes reported by Head et al. [25] and other retrospective studies [26,27]. Zhang et al. conducted a meta-analysis [19] and reported no difference in all-cause mortality between PCI and CABG among patients with left main CAD. Subgroup analysis in this meta-analysis identified a similar trend. However, our findings showed that the risk of all-cause mortality is higher in patients with multivessel CAD, and similar findings have been reported in a previous meta-analysis that included only patients with multivessel CAD [23]. Recent propensity-matched research of over 100,000 patients validated the robustness of our results, reporting better survival rates with multivessel CABG compared to multivessel PCI [28]. Current guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and American College of Cardiology (ACC) have recommended that low-complexity multivessel disease can be treated with PCI-like lesions without total occlusions or side branch involvement. On the other hand, more complex multivessel disease (triple-vessel disease) is best managed with CABG [29,30].

A previous meta-analysis conducted among patients with left main CAD showed that the overall risk of stroke was significantly lower in the PCI arm compared to CABG am [31,32]. However, the current meta-analysis showed no significant difference in terms of risk of stroke between CABG and PCI. An in-depth analysis of the Syntax trial [21] and NOBLE trial [3] challenged the benefit of PCI over CABG in the risk of stroke by demonstrating that PCI was associated with the enhanced late stroke that might counteract the early benefit of PCI [3].

One of the benefits of CABG over PCI found in this meta-analysis and in previous meta-analyses [22,23] is the decreased rate of repeat revascularization in the group. Our study’s finding that the PCI group had an increased risk of revascularization than the CABG group is consistent with recent literature [31]. According to observational data, graft patency after CABG is good over the long term, with up to 95% patency in the left internal mammary artery after 15 years [33] and 86% patency in saphenous vein grafts after 10 years [34].

The profound significance of the heart team remains crucial in choosing the best strategy of revascularization for patients with multivessel disease. Current evidence from clinical trials suggests that CABG is preferred to PCI in patients with multivessel disease. The findings of this meta-analysis also support the favorable revascularization of CABG over PCI in patients with multivessel disease.

Limitations

The results of our meta-analysis should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. This was a trial-level meta-analysis as we did not have access to individual patient-level data. Thus, we were not able to perform subgroup analysis to determine whether CABG is superior to PCI for a reduction in all-cause mortality. Moreover, it was limited to certain subgroups of patients such as patients with high syntax scores. Heterogeneity was evident in the analysis of certain outcomes. To incorporate heterogeneity among studies, we used random-effect models for the analysis of those outcomes. We also performed a subgroup analysis to explore the heterogeneity.

Conclusions

In the pooled data of 9,941 patients with CAD (4,954 in the CABG arm and 4,987 in the PCI arm), CABG was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality and repeat revascularization compared to PCI. This mortality benefit was observed particularly among patients with multivessel CAD. However, no significant difference was reported in the risk of cardiovascular mortality, myocardial infarction, and stroke between the two groups. Considering the risk of revascularization in patients with CAD, CABG needs to be the preferred method of revascularization for patients with CAD. Compared with CABG, PCI with second-generation DES might be a safe strategy for repeat revascularization in patients with CAD; however, it is associated with increased chances of revascularization.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in low- and middle-income countries. Gaziano TA, Bitton A, Anand S, Abrahams-Gessel S, Murphy A. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2010;35:72–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coronary artery bypass graft surgery vs percutaneous interventions in coronary revascularization: a systematic review. Deb S, Wijeysundera HC, Ko DT, Tsubota H, Hill S, Fremes SE. JAMA. 2013;310:2086–2095. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in treatment of unprotected left main stenosis (NOBLE): a prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Mäkikallio T, Holm NR, Lindsay M, et al. Lancet. 2016;388:2743–2752. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. Stone GW, Sabik JF, Serruys PW, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2223–2235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with left main and multivessel coronary artery disease: do we have the evidence? Gersh BJ, Stone GW, Bhatt DL. Circulation. 2017;135:819–821. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.025263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronary artery bypass grafting vs. percutaneous coronary intervention for patients with three-vessel disease: final five-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. Head SJ, Davierwala PM, Serruys PW, et al. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2821–2830. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2375–2384. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drug-eluting stents vs. coronary-artery bypass grafting in multivessel coronary disease. Hannan EL, Wu C, Walford G, et al. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:331–341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selection of surgical or percutaneous coronary intervention provides differential longevity benefit. Smith PK, Califf RM, Tuttle RH, et al. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1420–1428. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Risk profile and 3-year outcomes from the SYNTAX percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting nested registries. Head SJ, Holmes DR Jr, Mack MJ, et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comparison of coronary bypass surgery with drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of left main and/or three-vessel disease: 3-year follow-up of the SYNTAX trial. Kappetein AP, Feldman TE, Mack MJ, et al. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2125–2134. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.In left main CAD, CABG reduced major adverse cardiac or cerebrovascular events at 5 years compared with PCI. Bates ER. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:0. doi: 10.7326/ACPJC-2017-166-4-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with sirolimus-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in unprotected left main stem stenosis. Boudriot E, Thiele H, Walther T, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randomized, controlled trial of coronary artery bypass surgery versus percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: six-year follow-up from the Stent or Surgery Trial (SoS) Booth J, Clayton T, Pepper J, Nugara F, Flather M, Sigwart U, Stables RH. Circulation. 2008;118:381–388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.739144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. Buszman PE, Kiesz SR, Bochenek A, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ten-year follow-up survival of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS II): a randomized controlled clinical trial of 3 therapeutic strategies for multivessel coronary artery disease. Hueb W, Lopes N, Gersh BJ, et al. Circulation. 2010;122:949–957. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary bypass surgery in United States veterans with diabetes. Kamalesh M, Sharp TG, Tang XC, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:808–816. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Randomized comparison of percutaneous coronary intervention with coronary artery bypass grafting in diabetic patients. 1-year results of the CARDia (Coronary Artery Revascularization in Diabetes) trial. Kapur A, Hall RJ, Malik IS, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:432–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Comparison of outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary artery bypass grafting. Kumar R, Mal K, Razaq MK, et al. Cureus. 2020;12:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Randomized trial of stents versus bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. Park SJ, Kim YH, Park DW, et al. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1718–1727. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Percutaneous intervention versus coronary artery bypass graft surgery in left main coronary artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Zhang XL, Zhu QQ, Yang JJ, et al. BMC Med. 2017;15:84. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0853-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coronary artery bypass grafting vs percutaneous coronary intervention and long-term mortality and morbidity in multivessel disease: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of the arterial grafting and stenting era. Sipahi I, Akay MH, Dagdelen S, Blitz A, Alhan C. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:223–230. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention for multivessel coronary artery disease: a one-stage meta-analysis. Chew NW, Koh JH, Ng CH, et al. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:822228. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.822228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting for coronary artery disease: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Head SJ, Milojevic M, Daemen J, et al. Lancet. 2018;391:939–948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for multivessel coronary disease. Bangalore S, Guo Y, Samadashvili Z, Blecker S, Xu J, Hannan EL. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1213–1222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Comparative effectiveness of revascularization strategies. Weintraub WS, Grau-Sepulveda MV, Weiss JM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1467–1476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Comparative effectiveness of multivessel coronary bypass surgery and multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention: a cohort study. Hlatky MA, Boothroyd DB, Baker L, et al. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:727–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, et al. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2501–2555. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Special Articles: 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Hillis LD, Smith PK, Anderson JL, et al. Anesth Analg. 2012;114:11–45. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182407c25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Left main coronary artery stenosis: a meta-analysis of drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting. Athappan G, Patvardhan E, Tuzcu ME, Ellis S, Whitlow P, Kapadia SR. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Percutaneous coronary intervention vs. coronary artery bypass graft surgery for unprotected left main coronary artery disease in the drug-eluting stents era--an aggregate data meta-analysis of 11,148 patients. Alam M, Huang HD, Shahzad SA, et al. Circ J. 2013;77:372–382. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The right internal thoracic artery: the forgotten conduit--5,766 patients and 991 angiograms. Tatoulis J, Buxton BF, Fuller JA. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:9–7. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arterial grafts for coronary bypass: a critical review after the publication of ART and RADIAL. Gaudino M, Bakaeen FG, Benedetto U, et al. Circulation. 2019;140:1273–1284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.041096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]