Abstract

The ET-15 clone within the electrophoretic type (ET)-37 complex of Neisseria meningitidis was first detected in Canada in 1986 and has since been associated with outbreaks of meningococcal disease in many parts of the world. While the majority of the strains of the ET-37 complex are serosubtype P1.5,2, serosubtype determination of ET-15 strains may often be incomplete, with either only one or none of the two variable regions (VRs) of the serosubtype PorA outer membrane protein reacting with monoclonal antibodies. DNA sequence analysis of the porA gene from ET-15 strains with one or both unidentified serosubtype determinants was undertaken to identify the genetic basis of the lack of reaction with the monoclonal antibodies. Fourteen different porA alleles were identified among 38 ET-15 strains from various geographic origins. The sequences corresponding to subtypes P1.5a,10d, P1.5,2, P1.5,10d, P1.5a,10k, and P1.5a,10a were identified in 18, 11, 2, 2, and 1 isolate, respectively. Of the remaining four strains, which all were nonserosubtypeable, two had a stop codon within the VR1 and the VR2, respectively, while in the other two the porA gene was interrupted by the insertion element, IS1301. Of the strains with P1.5,2 sequence, one had a stop codon between the VR1 and VR2, one had a four-amino-acid deletion outside the VR2, and another showed no expression of PorA on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Our results reveal that numerous genetic events have occurred in the porA gene of the ET-15 clone in the short time of its epidemic spread. The magnitude of microevolutionary mechanisms available in meningococci and the remarkable genetic flexibility of these bacteria need to be considered in relation to PorA vaccine development.

Neisseria meningitidis expresses different porins in its outer membrane which may be characterized serologically. Meningococci possess either a class 2 or 3 protein which defines the serotype and a class 1 protein which defines the serosubtype (14). Sequencing of the porA gene, which encodes the class 1 or PorA protein, revealed that antigenic variation occurs within two variable regions (VRs) of the porin, referred to as VR1 and VR2. These are located on loops 1 and 4, respectively, and are responsible for the generation of the two serosubtype specificities (5, 22–25, 31).

In the early 1990s, outbreaks of serogroup C meningococcal disease occurred in Canada. Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, which has been used extensively for genotyping of N. meningitidis, revealed that the strains responsible for these outbreaks belonged to the electrophoretic type (ET)-37 complex but were characterized by a rare allele at the fumarase locus (4). This new variant, designated ET-15, was subsequently associated with outbreaks of meningococcal disease in parts of the United States, Israel, the Czech Republic, Iceland, Finland, Norway, England, Germany, and Australia (8, 18–20, 28, 34–35). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and Southern hybridization analysis of ET-15 strains confirmed a common origin of the strains causing these outbreaks and demonstrated that, in addition to the change in the fumarase locus, large genetic rearrangements had occurred within the ET-37 complex in association with the appearance of this new clone (19).

The predominant serotype-serosubtype combination associated with strains of the ET-37 complex is 2a:P1.5,2 (8), and most ET-15 strains had the phenotype C:2a:P1.5,2. The monoclonal antibody-based typing scheme currently used is, however, not comprehensive, and many isolates can be only partially typed. This is especially true for strains of ET-15 which may present an incomplete serosubtype or are fully nonserosubtypeable (NST). Thus, the phenotypes C:2a:P1.5, C:2a:P1.2, and C:2a:NST have been frequently encountered in ET-15 strains.

We report here the results of sequence analysis of the porA gene in 38 meningococcal ET-15 strains from diverse geographical origins that had an incomplete serosubtype or were NST. This study was undertaken in order to (i) establish the VR1 and VR2 occurring in NST and partially typed strains, (ii) determine the level of expression and specificity of the PorA proteins in selected strains, and (iii) define the extent of genetic variability of the porA gene in strains of a single clone during epidemic spread. The results revealed a high degree of porA gene variability among meningococci of the ET-15 clone which had occurred in about a decade, thus reinforcing the inadequacy of the current serological typing reagents. Many different genetic mechanisms were involved in generating this diversity, further illustrating the evolutionary potential of the meningococcal genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

The 38 strains examined were identified as belonging to the ET-37 complex by their allelic variation at 14 enzyme loci (8). In addition, all of them presented the allele 2 at the fumarase locus, identified in Canada as a marker for the ET-15 variant (4). Of these isolates, 23 were selected on the basis of their incomplete serosubtype among 72 ET-15 strains previously analyzed for genome organization (19). This ET-15 collection was supplemented with a further 10 isolates from Australia and 6 strains from Norway that also presented incomplete serosubtypes. The serological characteristics of the 38 ET-15 strains on dot blots (36) were as follows: C:2a:P1.5 (23 strains), C:NT:P1.5 (1 strain), C:2a:P1.2 (5 strains), C:2a:NST (8 strains), and B:2a:P1.2 (1 strain). The 38 strains spanned the years 1988 to 1999 and, with the exception of strain II050775 from a healthy carrier in Iceland, they were recovered from patients in Australia, Canada, the Czech Republic, England, Finland, Israel, and Norway. The strain characteristics are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the 38 ET-15 N. meningitidis isolates

| porA allele | Strain no. | Source | Yr | Phenotypea | Subtypeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 95N477*c | Australia | 1995 | B:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| I | 50447* | Australia | 1996 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5,2 |

| I | 57463 | Australia | 1996 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5,2 |

| I | 88080* | Canada | 1988 | C:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| I | 89486* | Canada | 1989 | C:2a:NST | P1.5,2 |

| I | 343/93* | Czech Republic | 1993 | C:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| I | 58* | Finland | 1994 | C:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| I | M929* | Israel | 1993 | C:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| II | M837* | Israel | 1992 | C:2a:P1.2 | P1.5,2 |

| III | 15/98* | Norway | 1998 | C:2a:NST | P1.5,2 |

| IV | 84/96* | Norway | 1996 | C:2a:NST | P1.5,10d |

| IV | 114/96* | Norway | 1996 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5,10d |

| V | 96M1966 | Australia | 1996 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10a |

| VI | 94N266* | Australia | 1994 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VII | 98N079 | Australia | 1998 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 94N369* | Australia | 1994 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 95N668 | Australia | 1995 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 97N221 | Australia | 1997 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 97N236 | Australia | 1997 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 97WM008 | Australia | 1997 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 98N005 | Australia | 1998 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 98N041 | Australia | 1998 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 98N097 | Australia | 1998 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 98N161 | Australia | 1998 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 99N001 | Australia | 1999 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 934286 | England | 1993 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 311268 | England | 1995 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 17 | Finland | 1992 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 11/94* | Norway | 1994 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 121/95 | Norway | 1995 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| VIII | 36/97 | Norway | 1997 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10d |

| IX | 251033* | England | 1995 | C:2a:P1.5 | P1.5a,10k |

| IX | 85/96 | Norway | 1996 | C:NT:P1.5 | P1.5a,10k |

| X | 311340* | England | 1995 | C:2a:NST | P1.5,2 |

| XI | 67* | Finland | 1994 | C:2a:NST | P1.5,− |

| XII | M702/91* | Iceland | 1991 | C:2a:NST | P1.−,2 |

| XIII | 91297* | Canada | 1991 | C:2a:NST | IS1301 |

| XIV | II050775* | Iceland | 1993 | C:2a:NST | IS1301 |

NT, nonserotypeable.

Subtype = VR loop names, as defined by sequence analysis.

*, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

PCR amplification and sequencing.

One loopful of N. meningitidis cells was boiled for 10 min in 100 μl of 1× TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0). PCR to amplify the porA genes were performed on 1 μl of boiled cells using the following primer pairs: 730 (5′-AAACTTACCGCCCTCGTA-3′) and 733 (5′-TTAGAATTTGTGGCGCAAACCGAC-3′) (9). Reactions were carried out in 50-μl volumes, containing 1× buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.1 M Tris HCl, pH 8.3; 0.5 M KCl; 0.1% gelatin), 1 U of AmpliTaq (Perkin-Elmer), 200 μM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 1 μl of each primer (20 pmol). Cycling conditions were as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min 30 s and terminated by 5 min at 72°C. The resulting PCR products were visualized with ethidium bromide on a 0.7% agarose gel. These PCR products were then prepared for sequencing by purification with shrimp alkaline phosphatase and exonuclease I (Amersham Life Science, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequencing was undertaken using the ABI Prism Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (PE Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers used for sequencing of the PCR product were the PCR primers 730 and 733 and the primers E (5′-CCGCACTGCCGCTTGCGG-3′) and H (5′-CGCATATTTAAAGGCATA-3′) (24). Primers IS1301a (5′-TCGTCGATGAATACCCATTC-3′) and IS1301b (5′-AGTCATCAAGAAGCCCAGTT-3′) were also used for sequencing of the PCR products of strains 91297 and II050775. Sequencing reactions were run on the ABI Prism 377 (PE Applied Biosystems) using 5% Long Ranger Gels (FMC Bioproducts).

Sequence assembly and analysis.

DNA sequences were determined on both strands. Sequences were assembled with the AutoAssembler DNA Sequence Software version 2.0, and consensus sequences compared using Sequence Navigator DNA and Protein Sequence Comparison Software (PE Applied Biosystems). Consensus sequences representative of each variant were then analyzed with the GenBank BLASTN search and the Neisseria meningitidis porA Variable Region Database (VRD) (2; M. C. J. Maiden, I. M. Feavers, and J. Russell, http://mlst.zoo.ox.ac.uk/porA-vr/vr_index.htm). Representative sequences for alleles determined in this study were submitted to GenBank (accession numbers AF173020 to AF173031, AF174359, and AF174360).

SDS-PAGE and whole-cell immunoblotting analysis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as previously described in 12% polyacrylamide gels with whole-cell suspensions of heat-inactivated meningococci, boiled in sample buffer, as antigens (36). The strains examined are marked by an asterisk in Table 1. Fourteen of these strains were further analyzed in immunoblots (36) for their reactions with monoclonal antibodies specific for the P1.5 (MN22A9.19), P1.2 (3-1-P1.2), and P1.10 (56C5/MN20.F4.17) epitopes, as well as for the common PorA epitope, P1.C (9-1-P1C). The monoclonal antibodies were kindly provided by W. D. Zollinger and J. T. Poolman.

RESULTS

PCR and sequence analysis.

PCR with primers 730 and 733 resulted in the amplification of a product of ca. 1,100 bp for all but two strains. The exceptions were the patient isolate 91297 from Canada and the carrier isolate from Iceland II050775, which both gave a product of ca. 1,900 bp.

The PCR product obtained for the 38 strains was sequenced, and a segment of the porA gene starting seven codons from the signal peptide was compared for all strains. A total of 14 alleles of the porA gene were identified. Each allele was assigned a roman number (Table 1), starting with the subtype commonly associated with strains of the ET-37 complex, P1.5,2. Tables 2 and 3 depict the sequence results obtained for VR1 and VR2, respectively. Five different VR1s and five different VR2s were identified. The deduced amino acid sequences of the corresponding VRs were compared to those previously published (10, 32; Maiden et al., VRD) using the designation scheme of Suker et al. (32). The VR1 and VR2 designations were based on the translated nucleotide sequence and were assigned regardless of the monoclonal antibody interpretation.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide sequences encoding the VR1 region of the PorA in ET-15 N. meningitidis strains

| Representative straina | VR1 DNA sequenceb | VR1(s) identified in allele no. | Epitope variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 58 | CCG CTC CAA AAT ATT CAA ... CCT CAG GTT ACT AAG CGC AAA | I–IV, X, XI | P1.5 |

| 11/94 | CCG CTC CAA AAT ATT CAA CAA CCT CAG GTT ACT AAG CGC AAA | V–IX | P1.5a |

| M702/91 | CCG CTC CAA AAT ATT CAA ... CCT TAG | XII | Stop codon |

| 91297 | CCG CTC CAA AAT ATT CAA ... CCT CAG GTT ACT AG-IS1301 (reverse orientation) | XIII | IS1301 detected |

| II050775 | CCG CTC CAA AAT ATT CAA ... CCT CAG GTT ACT AG-IS1301 (forward orientation) | XIV | IS1301 detected |

Strains representative of the corresponding VR1 nucleotide sequence; other strains with the same epitope are listed in Table 1.

A period indicates a gap inserted for the purpose of alignment. The underlined segment indicates the insertion recognition site for IS1301, and the boldface letters refer to the mutation A→G.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide sequences encoding the VR2 region of the PorA in ET-15 N. meningitidis strains

| Representative straina | VR2 DNA sequenceb | VR2(s) identified in allele no. | Epitope variant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 57463 | CAT TTT GTT CAG CAG ACT CCT AAA AGT CAG ... ... ... CCT ACT CTC GTT CCG | I–III, X, XII | P1.2 |

| 96M1966 | CAT TTT GTT CAG AAT AAG CAA AAT ... ... ... CAG CCG CCT ACT CTC GTT CCG | V–VIII | P1.10a |

| 311268 | CAT TTT GTT CAG AAT AAG CAA AAT AAG CAA AAT CAG CCG CCT ACT CTC GTT CCG | IV | P1.10d |

| 85/96 | CAT TTT GTT CAG AAT AAG CAA AAT CAG CAA AAT CAG CCG CCT ACT CTC GTT CCG | IX | P1.10k |

| 67 | CAT TTT GTT CAG TAG | XI | Stop codon |

Strains representative of the corresponding VR2 nucleotide sequence; other strains with the same epitope are listed in Table 1.

A period indicates a gap inserted for the purpose of alignment. The mutation between P1.10d and P1.10k is marked in boldface.

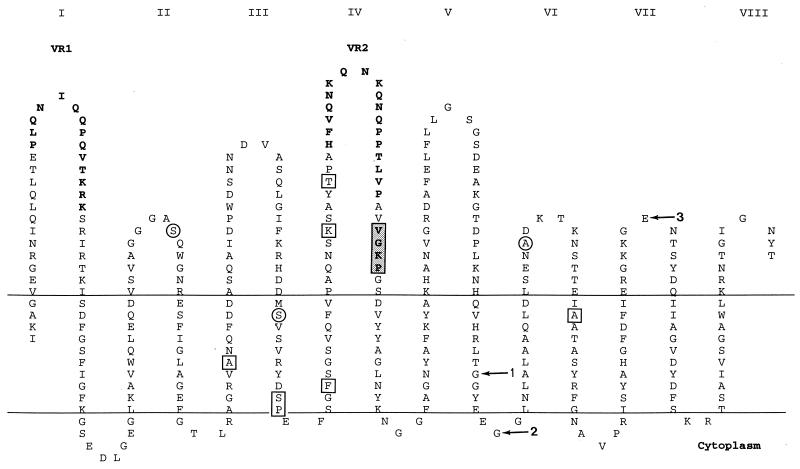

Of the 14 porA alleles, allele VIII was the most common and was found in 16 of the 38 isolates. It corresponded to subtype P1.5a,10d, as defined by the VRs sequences (Table 1). Figure 1, based on the class 1 porin topology model described by van der Ley et al. (33), shows the loop structure of the molecule with the peptide sequence deduced from the sequence of allele VIII. The sites where the other alleles differed from this sequence are indicated.

FIG. 1.

Topology of P1.5a,10d class 1 protein, based on the model of van der Ley et al. (33), depicting the 10 substitution sites outside of VR1 and VR2; circles indicate sites of mutations leading to amino acid changes, and squares indicate sites of silent mutations. The loops exposed on the cell surface are numbered by roman numerals. The two VRs are indicated in boldface; the shaded box indicates the site of the four-amino-acid deletion in strain 15/98 (allele III). Arrows indicate the sites of mutations identified in alleles II (arrow 1), V (arrow 3), and VI and VII (arrow 2).

Two other strains, 94N266 and 98N079, also with the deduced subtype P1.5a,10d, represented two distinct porA alleles (alleles VI and VII), differing from allele VIII by single base mutations at the same site in the periplasmic region between loops V and VI. These mutations resulted in a G→D substitution (allele VI) and a G→A substitution (allele VII). Subtype P1.5a,10k (allele IX) was found in two strains, and subtype P1.5a,10a (allele V) was found in one strain, 96M1966. This last strain had, in addition to a different VR2, an E→A mutation at the top of loop VII.

The second most common subtype, found in 11 of the 38 strains, was P1.5,2. Eight of these strains had the same porA sequence (allele I), whereas alleles II, III, and X were represented by one strain each. Allele II presented a mutation in the transmembrane region between loops V and VI; allele III had a four-amino-acid deletion in loop IV, just outside of VR2 (shaded block in Fig. 1), and allele X had a stop codon between VR1 and VR2.

Of the 23 isolates with VR2 belonging to the P1.10 sequence family, 21 had the same 10 single base substitutions outside the two VRs (see Fig. 1) in comparison with strains having a VR2 of the P1.2 family. Of these 10 base differences, 3 resulted in amino acid substitutions in loop II, in loop IV, and in the transmembrane region between loops III and IV, respectively. The remaining two strains with VR2 in the P1.10 family, 84/96 and 114/96 (both allele IV and corresponding to subtype P1.5,10d), were found to have all but the first 2 of the 10 substitutions outside the VRs.

The remaining four strains each presented a distinct allele (alleles XI to XIV). Strains M702/91 and 67 had a stop codon interrupting the VR1 and the VR2, respectively, while the porA of 91297 (allele XIII) and II050775 (allele XIV) was interrupted by a single copy of the insertion sequence IS1301 in VR1 (15, 16). The insertion site was identical, but the orientation of IS1301 differed for these two isolates (Table 2). The target consensus for insertion of IS1301, 5′-AYTAG-3′ (16), was found within the porA gene of these strains, generated by an A→G mutation in VR1 (Table 2), and was accompanied by a TA duplication.

GenBank accession numbers.

The following nucleotide sequences were submitted to GenBank: 343/93, allele I (AF173031); M837, allele II (AF173020); 15/98, allele III (AF173024); 84/96, allele IV (AF173025); 96M1966, allele V (AF173030); 94N266, allele VI (AF173026); 98N079, allele VII (AF173028); 94N369, allele VIII (AF173027); 251033, allele IX (AF173029); 311340, allele X (AF173022); 67, allele XI (AF173023); M702/91, allele XII (AF173021); 91297, allele XIII (AF174359); and II050775, allele XIV (AF174360).

SDS-PAGE and whole-cell immunoblot analysis.

The P1.5a subtype differs from P1.5 by an extra glutamine (Q) residue on the top of the loop I of the PorA. The monoclonal antibody directed against P1.5 recognizes both epitopes on dot blot but reacts more strongly and at a lower concentration with P1.5a subtype strains than with P1.5 strains (E. Wedege, unpublished data). This was illustrated by the fact that all of our strains with the P1.5a sequence reacted with the P1.5 monoclonal antibody on dot blot, while those with the P1.5 sequence had more variable reactions. None of the variants of the P1.10 family, identified by sequencing of the VR2 in this study, reacted with the P1.10 monoclonal antibody on dot blot, although it has been reported that P1.10a may be detected at a high antibody concentration (32). To analyze the cause of some discrepancies between the antibody reaction on dot blot and the sequence data, a selection of the strains were further studied by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

The specificities demonstrated by dot blot were generally also seen in immunoblotting (Table 4). However, most of the selected strains expressed low levels of PorA in comparison with meningococcal strains of other genetic lineages previously analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Among the nine strains (alleles I through III) with a DNA sequence in the VRs of the porA corresponding to subtype P1.5,2, one NST strain, 89486, had no detectable PorA band on SDS-PAGE gels. That strain also showed no reaction in immunoblots with all monoclonal antibodies, including P1C, which binds to a conformational epitope present in nearly all class 1 outer membrane proteins (Table 4). Another NST strain, 15/98, showed a low level of class 1 protein on SDS-PAGE gels, and by immunoblotting a very weak reaction was seen with the P1.2 monoclonal antibody. The lack of reaction of strain 15/98 with the P1.2 monoclonal antibody on dot blots may be caused by the four-amino-acid deletion occurring just after the VR2, which may lead to less exposure of the P1.2 epitope. Strain 50447, which surprisingly according to its porA sequence, clearly reacted with the P1.5 but not with the P1.2 monoclonal antibodies on dot blot, showed the same reaction in immunoblot (Table 4). The lack reaction of the P1.2 monoclonal antibodies with that strain can only be explained by interaction of the PorA with other molecules.

TABLE 4.

Detection of PorA in ET-15 N. meningitidis strains by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting reaction with monoclonal antibodies specific for the P1.C, P1.2, P1.5, and P1.10 epitopesa

| Strain | Phenotype on dot blot | porA sequence | SDS-PAGE detection | Immunoblotting detection

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1.C | P1.5 | P1.2 | P1.10 | ||||

| 95N477 | P1.2 | P1.5,2 | (+) | + | − | + | − |

| 50447 | P1.5 | P1.5,2 | + | + | + | − | − |

| 89486 | NST | P1.5,2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| M837 | P1.2 | P1.5,2 | + | + | (+/−) | + | − |

| 15/98 | NST | P1.5,2 | (+) | (+) | − | (+/−) | − |

| 84/96 | NST | P1.5,10d | (+) | + | − | − | − |

| 94N266 | P1.5 | P1.5a,10d | + | + | + | − | − |

| 11/94 | P1.5 | P1.5a,10d | (+) | (+) | (+) | − | − |

| 251033 | P1.5 | P1.5a,10k | (+) | + | + | − | − |

| 311340 | NST | P1.5,2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| M702/91 | NST | P1.5,− | − | − | − | − | − |

| 67 | NST | P1.−,2 | − | − | − | − | − |

| 91297 | NST | IS1301 | − | − | − | − | − |

| II050775 | NST | IS1301 | − | − | − | − | − |

Weaker reactions are indicated in parentheses.

No expression of the PorA protein was detected by SDS-PAGE or immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies for the NST strains 311340, 67, M702/91, 91297, and II050775 (alleles X through XIV), which either had a stop codon within the porA gene or an insertion of IS1301 (Table 4). Thus, of the eight NST ET-15 strains, six totally lacked a PorA. The lack of reaction of the monoclonal antibodies was due to factors other than genetic variation in the sequenced region of the porA gene in three strains: 50447, which should have reacted with P1.2; 89486, which did not express a PorA, although the gene was present; and 84/96, which should have reacted with P1.5.

DISCUSSION

Genetic characterization of the porA gene of N. meningitidis has been utilized extensively as a research tool (3, 10, 12, 22, 23, 31) but, as yet, has not been undertaken routinely for subtype identification. The use of monoclonal antibodies remains the most common technique for assigning serotypes and serosubtypes (1, 13, 27). However, there have been increasing reports of the failure of the existing panel of typing reagents to detect both VRs, and many strains are reported as NST (3, 10, 32). In this study we examined a collection of 38 strains, all of which had previously been identified as belonging to a single newly generated clone of the ET-37 complex (4, 8). This new variant, ET-15, was first identified in 1986 after an extensive outbreak of meningococcal disease in Canada (4) and has later been associated with outbreaks and clusters of meningococcal disease in many different countries (4, 8, 18, 20, 28, 34–35). The ET-15 strains examined here were isolated between 1988 and 1999 in eight countries and were selected on the basis of their phenotypic traits.

Given that the class 1 outer membrane protein of N. meningitidis is an important vaccine target, it is necessary to have a full complement of information regarding the genetic events which can and does arise within this gene during the epidemic spread of a clone. In the ET-15 strains the lack of reaction of the serosubtyping monoclonal antibodies was shown to result from numerous independent genetic events, since a total of 14 alleles were recognized among the 38 strains. Of the strains, 23 were originally part of a collection of 72 ET-15 strains that were selected regardless of their serological characteristics, showing that the genetic events encountered here may be epidemiologically significant.

The oldest ET-15 strains isolated in Canada were usually serotype 2a:P1.5,2, suggesting that allele I was the original porA of ET-15. Recombination of parts or most of the gene was likely involved in generating the P1.5a,10d subtype from the original P1.5,2 subtype in the Canadian ET-15 strain, since the two sequences differed by numerous single base substitutions outside the two VRs, in addition to the two subtype-specific VRs. Another recombinational event starting within loop III was probably responsible for the P1.5,10d subtype. Allele VIII dominance among the 38 strains reflects, in part, the fact that a large proportion of Australian strains was included in the analysis and that all Australian strains with allele VIII might have a common origin. Both allele I and allele VIII were found in several countries. Our study does not permit determination of whether the generation of allele VIII has occurred independently several times during the spread of ET-15 or whether after the recombinational event generating allele VIII, ET-15 with allele I and with allele VIII, respectively, has had an intercontinental spread.

Single base mutations from one of the two common subtypes, P1.5,2 and P1.5a,10d, may have generated seven of these alleles, inclusive of three mutations to stop codons in different parts of the gene, resulting in no PorA expression. Three mutations occurred in the transmembrane region (allele II) or in the periplasmic region (alleles VI and VII) of PorA. These regions are not surface exposed, and thus these mutations are unlikely to provide protection against eventual bactericidal antibodies during the pathogenic process. It is noteworthy, however, that all three mutations are located within a fragment of the PorA molecule that has been shown to be one of the immunodominant T-cell epitopes recognized in humans (37). The other variants resulted from duplication of a codon, duplication of a codon triplet, deletion of four codons, and two cases of insertion of IS1301. In addition, one strain with allele I did not express a PorA, but the reason for the lack of expression has not been elucidated. Mutation in the promoter region of the porA gene has previously been shown to result in a total loss of expression (3).

Insertional inactivation of the porA gene by IS1301 has been described previously (3, 26). IS1301 was found at the same location within the VR1 in two ET-15 strains in this study, resulting in no PorA production and a phenotype of C:2a:NST. The orientation of IS1301 differed, however, between these two strains. The ability of IS1301 to insert with different orientations has been described previously: orientation of IS1301 varied among the 12 insertion sites in the chromosome of N. meningitidis B1940 (16). The target consensus for insertion of IS1301 is 5′-AYTAG-3′, and this target site was found within the porA gene of our strains, with a A→G mutation being a prerequisite for the fulfillment of the insertion site criteria (15, 16). In all cases of inactivation of porA genes by IS1301 reported so far, the strains involved were serogroup C with either serotype 2a (26) or subtype P1.5,2 (3), phenotypes that are frequently associated with strains of the ET-37 complex. Although the multilocus genotypes of these specific strains have not been analyzed, they were recently isolated in Canada and England during increased meningococcal disease associated with ET-15 (4, 8). The two isolates identified here were from Canada and Iceland and represented two different genetic events, as evidenced by the reverse orientation of the insertion element. We found IS1301 inactivation of the porA gene in 2 of the 38 ET-15 isolates; in a recent study, 1 of 10 strains from Quebec with the P1.5,2 subtype, also probably ET-15, presented IS1301 (3). Thus, one could surmise that inactivation of the porA gene by IS1301 is not an infrequent event in the ET-15 clone.

The porA gene has been targeted as a diagnostic marker and has been extensively utilized in PCR strategies (9, 26, 29). In spite of the numerous diagnostic porA gene PCRs that have been undertaken in our laboratory and others, IS1301 has not been detected in clinical samples analyzed by porA PCRs other than those reported by Newcombe et al. (26). Thus, inactivation of the porA gene of meningococcal strains by IS1301 is unique to ET-15.

The distribution of IS1301 in the genome of meningococcal strains belonging to various genetic lineages was recently studied and shown to rarely occur in clones associated with epidemic disease (17). Especially, only 3 of 103 (3%) of serogroup C strains of the ET-37 complex possessed a copy of IS1301 anywhere in their genome (17), and two of these, one from Australia and one from Norway, were ET-15. Whether the insertion site for these two strains was also the porA gene has not been determined, but it is unlikely since the strains were subtypeable.

The range of VR families identified in the ET-15 strains was limited. For the VR2, the prototype subtype 2 was found, as well as several variants of the subtype 10 family: 10a, 10d, and 10k. The VR1 family was less diverse, with only subtypes 5 and 5a being represented. Although the porA gene has a mosaic structure (11) resulting from frequent recombinational events (30), within the period of 13 years since the origin of ET-15 only related VRs have been seen in association with the clone. Thus, genetic exchange has been restricted to a few closely related porA genes, perhaps because of structural constraints from other antigens in the outer membrane. Numerous genetic events other than recombination have been responsible for the allelic variation of the porA gene in these 38 strains. They have led to either minor modification of the epitopes, resulting in the failure of the monoclonal antibodies to adequately detect the VRs or the total loss of expression of the PorA protein. Deletion of a single amino acid is sufficient to hinder the recognition of the epitopes by the monoclonal antibodies (10, 12, 22, 31, 32). Other genes of ET-15 also are subject to high rate of genetic changes. Microevolution among strains of ET-15 isolated in the Czech Republic since 1993 was newly evidenced by study of the polymorphism in siaD, pilA, and pilD genes (21).

Previously, the uniformity of the porA genes of serogroup C strains isolated from various locations was explained by the fact that these strains were of limited genetic diversity and recombination with other meningococci occurred infrequently (10). Our results reveal, however, the generation of a considerable degree of porA diversity among a selection of 38 strains belonging to the ET-15 clone of the ET-37 complex, all of which must have occurred since the emergence of this new clone after 1986. The porA gene is an important epidemiological marker, and comprehensive analysis of this gene can provide valuable data, especially during an outbreak of meningococcal disease. With the development of wild-type outer membrane vesicle vaccines (6) and polyvalent PorA vaccines (7), full porA gene characterization is also crucial if the PorA antigen is to be a useful vaccine target.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the receipt of strains from participating laboratories of the Australian National Neisseria Network. The excellent technical assistance of Torill Alvestad and Karin Bolstad is acknowledged. We thank Fredrik Oftung for valuable discussion.

This work was supported in part by a South Western Area Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales Postgraduate Scholarship to J.J. and by grant C11/181/23 from the World Health Organization to D.A.C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdillahi H, Poolman J T. Whole-cell ELISA for typing Neisseria meningitidis with monoclonal antibodies. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:367–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local assignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:404–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arhin F F, Moreau F, Coulton J W, Mills E L. Sequencing of porA from clinical isolates of Neisseria meningitidis defines a subtyping scheme and its genetic regulation. Can J Microbiol. 1998;44:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashton F E, Ryan J A, Borczyk A, Caugant D A, Mancino L, Huang D. Emergence of a virulent clone of Neisseria meningitidis serotype 2a that is associated with meningococcal group C disease in Canada. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2489–2493. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.11.2489-2493.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barlow A K, Heckels J E, Clarke I N. The class 1 outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis: gene sequence and structural and immunological similarities to gonococcal porins. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjune G, Høiby E A, Grønnesby J K, Arnesen O, Fredriksen J H, Halstensen A, Holten E, Lindbak A-K, Nøkleby H, Rosenqvist E, Solberg L K, Closs O, Eng J, Frøholm L O, Lystad A, Bakketeig L S, Hareide B. Effect of outer membrane vesicle vaccine against group B meningococcal disease in Norway. Lancet. 1991;338:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91961-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cartwright K, Morris R, Rumke H, Fox A, Borrow R, Begg N, Richmond P, Poolman J. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity in UK infants of a novel meningococcal vesicle vaccine containing multiple class 1 (PorA) outer membrane proteins. Vaccine. 1999;17:2612–2619. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caugant D A. Population genetics and molecular epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis. APMIS. 1998;106:505–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caugant D A, Høiby E A, Frøholm L O, Brandtzaeg P. Polymerase chain reaction for case ascertainment of meningococcal meningitis: application to the cerebrospinal fluids collected in the course of the Norwegian meningococcal serogroup B protection trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 1996;28:149–153. doi: 10.3109/00365549609049066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feavers I M, Fox A J, Gray S, Jones D M, Maiden M C. Antigenic diversity of meningococcal outer membrane protein PorA has implications for epidemiological analysis and vaccine design. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1996;3:444–450. doi: 10.1128/cdli.3.4.444-450.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feavers I M, Heath A B, Bygraves J A, Maiden M C J. Role of horizontal genetic exchange in the antigenic variation of the class 1 outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:489–495. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feavers I M, Yost S E, Maiden M C J. Molecular analyses of meningococcal serosubtyping antibodies. In: Evans J S, Yost S E, Maiden M C J, Feavers I M, editors. Proceedings of the Ninth Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. Winchester, United Kingdom: Mérieux Ltd.; 1994. pp. 314–315. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frasch C E, Tsai C M, Mocca L F. Outer membrane proteins of Neisseria meningitidis: structure and importance in meningococcal disease. Clin Investig Med. 1986;9:101–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frasch C E, Zollinger W D, Poolman J T. Serotype antigens of Neisseria meningitidis and a proposed scheme for designation of serotypes. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:504–510. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.4.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammerschmidt S, Hilse R, van Putten J P, Gerardy-Schahn R, Unkmeir A, Frosch M. Modulation of cell surface sialic acid expression in Neisseria meningitidis via a transposable genetic element. EMBO J. 1996;15:192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilse R, Hammerschmidt S, Bautsch W, Frosch M. Site-specific insertion of IS1301 and distribution in Neisseria meningitidis strains. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2527–2532. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2527-2532.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hilse, R., J. Stoevesandt, D. A. Caugant, M. Frosch, and U. Vogel. Distribution of the meningococcal insertion sequence IS1301 in clonal lineages of Neisseria meningitidis. Epidemiol. Infect., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jelfs J, Jalaludin B, Munro R, Patel M, Kerr M, Daley D, Neville S, Capon A. A cluster of meningococcal disease in western Sydney, Australia, initially associated with a nightclub. Epidemiol Infect. 1998;120:263–270. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898008681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jelfs J, Munro R, Ashton F, Rawlinson W, Caugant D A. Program and Abstracts of the 11th International Pathogenic Neisseria Conference. Paris, France: Editions EDK; 1998. Global study of variation in a new variant of the ET-37 complex of Neisseria meningitidis; p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kriz P, Vlckova J, Bobak M. Targeted vaccination with meningococcal polysaccharide vaccine in one district of the Czech Republic. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:411–418. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kriz P, Giorgini D, Musilek M, Larribe M, Taha M-K. Microevolution through DNA exchange among strains of Neisseria meningitidis isolated during an outbreak in the Czech Republic. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:273–280. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)80052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maiden M C J, Bygraves J A, McCarvil J, Feavers I M. Identification of meningococcal serosubtypes by the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2835–2841. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2835-2841.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maiden M C J, Suker J, McKenna A J, Bygraves J A, Feavers I M. Comparison of the class 1 outer membrane proteins of eight serological reference strains of Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:727–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGuinness B T, Barlow A K, Clarke I N, Farley J E, Anilionis A, Poolman J T, Heckels J E. Deduced amino acid sequences of class 1 protein (PorA) from three strains of Neisseria meningitidis. Synthetic peptides define the epitopes responsible for serosubtype specificity. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1871–1882. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.6.1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuinness B T, Clarke I N, Lambden P R, Barlow A K, Poolman J T, Jones D M, Heckels J E. Point mutation in meningococcal porA gene associated with increased endemic disease. Lancet. 1991;337:514–517. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newcombe J, Cartwright K, Dyer S, McFadden J. Naturally occurring insertional inactivation of the porA gene of Neisseria meningitidis by integration of IS1301. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:453–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poolman J T, Abdillahi H. Outer membrane protein serosubtyping of Neisseria meningitidis. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1988;8:291–292. doi: 10.1007/BF01963104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ringuette L, Lorange M, Ryan A, Ashton F. Meningococcal infections in the Province of Quebec, Canada, during the period 1991 to 1992. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:53–57. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.53-57.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saunders N B, Zollinger W D, Rao V B. A rapid and sensitive PCR strategy employed for amplification and sequencing of porA from a single colony-forming unit of Neisseria meningitidis. Gene. 1993;137:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90001-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maynard Smith J. Analyzing the mosaic structure of genes. J Mol Evol. 1992;34:126–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00182389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suker J, Feavers I M, Achtman M, Morelli G, Wang J-F, Maiden M C J. The porA gene in serogroup A meningococci: evolutionary stability and mechanism of genetic variation. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:253–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suker J, Feavers I M, Maiden M C J. Monoclonal antibody recognition of members of the meningococcal P1.10 variable region family: implications for serological typing and vaccine design. Microbiology. 1996;142:63–69. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van der Ley P, Heckels J E, Virji M, Hoogerhout P, Poolman J T. Topology of outer membrane porins in pathogenic Neisseria spp. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2963–2971. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.9.2963-2971.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel U, Morelli G, Zurth K, Claus H, Kriener E, Achtman M, Frosch M. Necessity of molecular techniques to distinguish between Neisseria meningitidis strains isolated from patients with meningococcal disease and from their healthy contacts. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2465–2470. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2465-2470.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vogel U, Morelli G, Zurth K, Claus H, Kriener E, Achtman M, Frosch M. Necessity of molecular techniques to distinguish between Neisseria meningitidis strains isolated from patients with meningococcal disease and from their healthy contacts (author's correction) J Clin Microbiol. 1998;37:882. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2465-2470.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wedege E, Høiby E A, Rosenqvist E, Frøholm L O. Serotyping and subtyping of Neisseria meningitidis isolated by co-agglutination, dot-blotting and ELISA. J Med Microbiol. 1990;31:195–201. doi: 10.1099/00222615-31-3-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiertz E J H J, van Gaans-van den Brink J A M, Gausepohl H, Prochnicka-Chalufour A, Hoogerhout P, Poolman J T. Identification of T cell epitopes occurring in a meningococcal class 1 outer membrane protein using overlapping peptides assembled with simultaneous multiple peptide synthesis. J Exp Med. 1992;176:79–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]