Abstract

The tumor microenvironment provokes endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in malignant cells and infiltrating immune populations. Sensing and responding to ER stress is coordinated by the unfolded protein response (UPR), an integrated signaling pathway governed by three ER stress sensors: activating transcription factor (ATF6), inositol-requiring enzyme 1 α (IRE1α), and protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK). Persistent UPR activation modulates malignant progression, tumor growth, metastasis, and protective anti-tumor immunity. Hence, therapies targeting ER stress signaling can be harnessed to elicit direct tumor killing and concomitant anti-cancer immunity. Here, we highlight recent findings on the role of the ER stress responses in onco-immunology, with an emphasis on genetic vulnerabilities that render tumors highly sensitive to therapeutic UPR modulation.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a dynamic organelle that controls fundamental cellular processes such as lipid metabolism, calcium balance, and especially the synthesis, folding, and post-translational modification of transmembrane and secreted proteins. While these processes must be tightly regulated to ensure cell survival, a variety of factors and conditions can disrupt ER homeostasis and provoke “ER stress”, a cellular state induced by the accumulation of misfolded and/or unfolded proteins in this organelle. Sensing and responding to ER stress is governed by the unfolded protein response (UPR), an integrated adaptive pathway that evolved to maintain ER proteostasis (Box 1). Three ER-resident sensors coordinate the UPR: inositol-requiring enzyme 1 α (IRE1α; encoded by ERN1), protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK; encoded by EIF2AK3), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6; encoded by ATF6). Increasing evidence indicates that malignant and immune cells residing in the tumor microenvironment (TME) experience sustained activation of the UPR. These events facilitate malignant progression and metastasis by enhancing the pro-tumorigenic attributes of cancer cells, while simultaneously disabling anti-tumor immunity. This review summarizes recent advances on the immunoregulatory activity of ER stress in tumors and highlights key alterations in cancer cells that render tumors sensitive to genetic or pharmacological abrogation of UPR elements.

Box 1: The UPR at a glance.

Under homeostatic conditions, ER stress sensors remain inactive due to interaction with binding-immunoglobulin protein (BiP; HSPA5/GRP78). Upon ER stress, BiP preferentially binds to misfolded protein and is titrated away from the sensors, enabling their activation. IRE1α is the most evolutionally conserved ER stress sensor that contains both a kinase and an RNase domain. Active IRE1α splices an internal 26-nucleotide fragment from the cytosolic XBP1 mRNA, generating the XBP1s isoform that encodes the functionally active transcription factor XBP1s[111]. Notably, a novel mediator of IRE1α-mediated XBP1s generation was identified[112]: In the MCF7 breast cancer cell line, estrogen receptor α (ERα) demonstrated RNA-binding activity that promoted XBP1s generation through interaction with the RtcB ligase, which mediates XBP1s religation after splicing[112]. Under severe ER stress, IRE1α-dependent decay of mRNA (RIDD)[113] degrades mRNAs containing CUGCAG consensus motifs to reduce further protein accumulation. Additionally, IRE1α can contribute to autophagy and apoptosis via interaction with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor (TRAF)2, which activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and nuclear transcription factor-kB (NF-kB)[114–116].

PERK-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit 1 alpha (eIF2α), arrests bulk cap-dependent translation and activates cap-independent alternative translation. PERK can also mediate alternative translation of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)[117], which induces expression of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP)[118]. Additionally, PERK phosphorylates other canonical substrates, including the prosurvival antioxidant regulating transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)[119]. PERK also exerts lipid kinase activity, catalyzing conversion of diacylglycerol (DAG) to phosphatidic acid (PA)[120].

Functioning as a transcription factor rather than a kinase or endoribonuclease, ATF6 undergoes serial intra-membrane proteolysis in response to ER stress to generate an amino terminal fragment of ATF6 (ATF6f)[121] that transactivates ER stress-related genes BIP, XBP1, and CHOP [122], while also acting as an molecular off-switch that terminates IRE1α-directed signaling[123].

Collectively IRE1α, PERK, and ATF6 coordinate the UPR, which (1) reduces biosynthetic demands on the ER through transient attenuation of bulk translation and active degradation of RNA; (2) resolves protein accumulation through protein refolding; (3) prompts ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) machinery; and (4) mediates the delivery of misfolded proteins from the ER to the lysosomes for degradation via autophagy or to the cytosol for proteasomal processing. If the cell is not capable of restoring ER homeostasis, the UPR ultimately mediates cell death[1].

ER stress-driven immunosuppression in tumors

The hostile tumor milieu, including scarcity of nutrients, low pH, accumulation of suppressive metabolites, uncontrolled generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and hypoxia, among others, cooperate to disrupt ER homeostasis in multiple intratumoral immune cell subsets, resulting in impaired anti-tumor immunity[1]. Below we discuss recent findings emphasizing the key immunoregulatory role of ER stress responses in the TME (Figure 1).

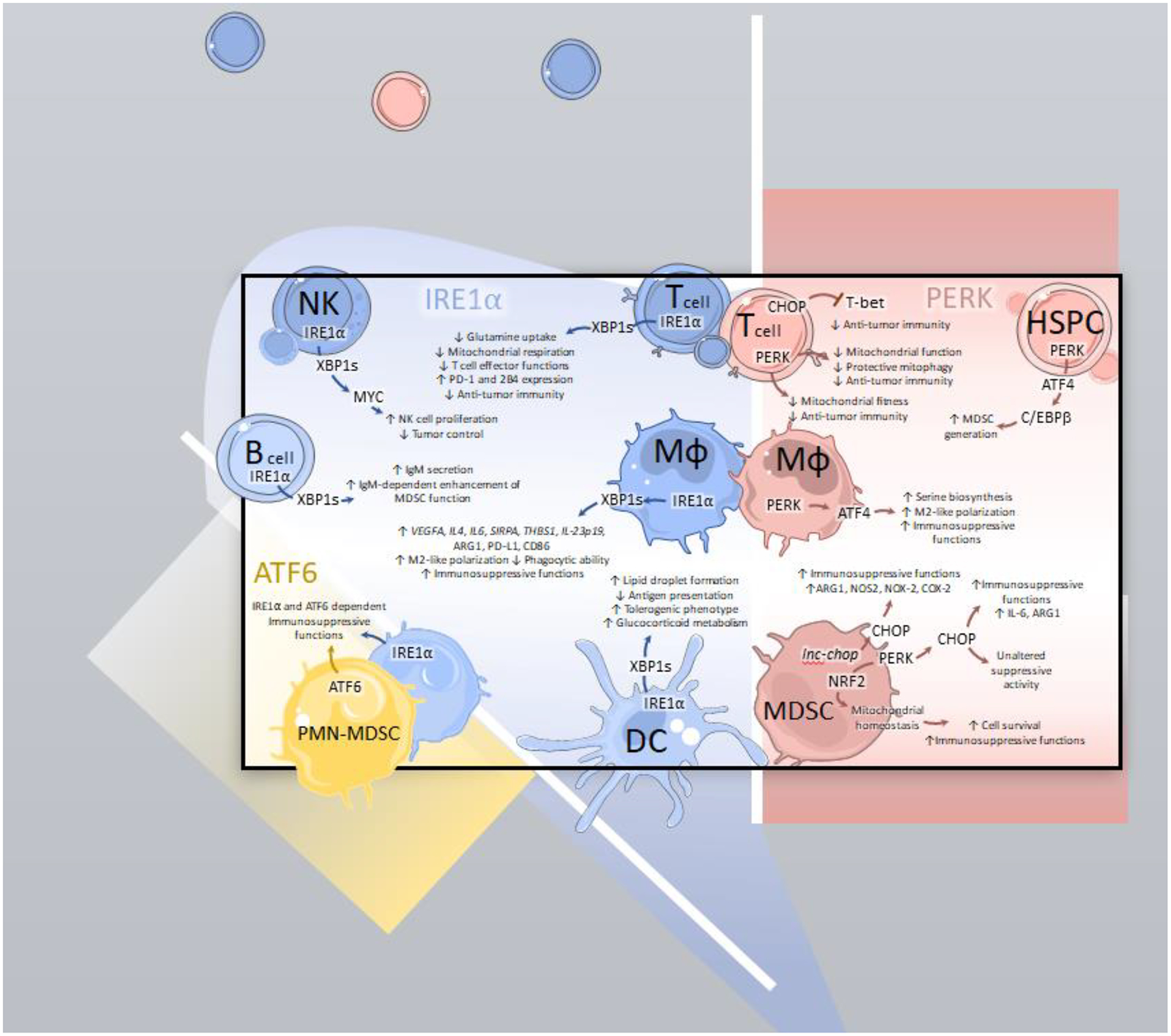

FIGURE 1: Immunoregulatory effects of ER stress signaling in the TME.

Intratumoral leukocytes experiencing ER stress demonstrate immunosuppressive reprogramming driven by activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), inositol requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and protein kinase R (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK).

ATF6: ATF6 and IRE1α contribute to the immunosuppressive attributes of tumor-associated polymorphonuclear (PMN) myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs; PMN-MDSCs).

IRE1α: In natural killer (NK) cells, IRE1α drives XBP1s-dependent activation of MYC that is needed for NK cell proliferation and thus, NK cell-dependent tumor control. Maladaptive IRE1α-XBP1s activation provokes metabolic reprogramming of intratumoral T cells, resulting in decreased glutamine uptake, reduced mitochondrial respiration, impaired effector function, elevated expression of checkpoint markers PD-1 and 2B4 and thus, overall decreased anti-tumor immunity. In tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs; MΦ), XBP1s galvanizes M2-like polarization corresponding to an increase in expression of suppressive markers (VEGFA, IL-4, IL-6, THBS1, SIRPA, IL-23p19, ARG1 and PD-L1). It also reduces TAM phagocytic capacity and promotes their immunosuppressive functions. Furthermore, in dendritic cells (DC), IRE1α activation causes lipid droplet accumulation, impaired antigen presentation, increased glucocorticoid metabolism, and a global shift towards a tolerogenic phenotype. In B cells, XBP1s promotes soluble IgM production that enhances MDSC function via an unknown mechanism.

PERK: In tumor-localized T cells, persistent PERK directs CHOP-dependent T-bet signaling resulting in impaired development of anti-tumor immunity and decreased overall mitochondrial fitness. Conversely, acute PERK activation induces protective mitophagy, mitochondrial function, and sustained anti-tumor T cell activation. In hematopoietic stem and precursor cells (HSPC), activation of PERK drives MDSC generation via downstream C/EBPβ signaling. In macrophages, PERK-directed ATF4 activation promotes serine biosynthesis that enables immunosuppressive functions. In MDSCs, PERK supports mitochondrial homeostasis via NRF2 activation, thus preserving MDSC survival and suppressive activity while directing CHOP-dependent signaling. CHOP fosters immunosuppressive functioning in MDSCs via upregulation of ARG1, NOS2, NOX-2, COX-2 and IL-6. CHOP may have limited effects on suppressive myeloid polarization depending on the context and tumor models utilized.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

As an abundant myeloid population in most cancer types, TAMs may promote protumoral angiogenesis, resistance to therapy, and immunosuppression[2]. Macrophage-intrinsic IRE1α was implicated in cathepsin secretion that facilitated cancer cell invasion in vitro[3]. Subsequent work indicated that TAMs isolated from colorectal cancer patients or from a murine model of colitis-associated cancer displayed increased XBP1 splicing compared to peripheral blood monocytes or splenic macrophages, respectively[4]. In bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) stimulated with conditioned media from colorectal cancer cells, XBP1s directly promoted the expression of VEGFA, IL-4, and IL-6, as well as ligands for “don’t eat me” signals such as SIRPA and THBS1. Loss of XBP1s augmented macrophage phagocytic capacity and impaired tumor formation in a mouse model of colorectal cancer, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear[4]. Changes in macrophage polarization upon ablation of IRE1α-XBP1s signaling were also described in B16.F10 melanoma models, where BMDMs exposed to conditioned medium from ER-stressed cancer cells upregulated pro-inflammatory IL-23p19 and IL-6, co-stimulatory CD86, and the immunosuppressive factors Arginase 1 (ARG1) and PD-L1. Blocking IRE1α signaling reduced overexpression of these molecules[5]. Notably, B16.F10 tumor-bearing mice selectively lacking IRE1α in macrophages demonstrated increased survival compared with their wild-type counterparts. XBP1s ablation in macrophages did not phenocopy these effects[5], suggesting that RIDD mediates these protumoral effects. Additional studies are needed to discern these potential mechanisms and define the functional significance of TAM-intrinsic RIDD.

IRE1α-XBP1s signaling in macrophages mediates optimal IL-6 production upon stimulation via Toll-like receptors (TLRs)[6]. Of note, human macrophages infected with Kaposi’s Sarcoma Herpesvirus demonstrated IRE1α-dependent expression of IL-6, IL-10, PD-L1, and VEGF[7], but further research is needed to confirm these findings in TAMs from Kaposi’s sarcoma patients.

A recent seminal study showed that TAMs or BMDMs co-cultured with melanoma cells undergo UPR activation and immunosuppressive polarization[8]. Mechanistically, cancer cell-derived β-glucosylceramide engaged the inducible Ca2+-dependent lectin receptor (Mincle) on macrophages, resulting in altered ER membrane lipid composition that triggered protumoral IRE1α-XBP1s signaling[8]. Importantly, reduced XBP1s in TAMs and increased host survival were observed when tumor-bearing mice were treated with a liver X receptor (LXR) agonist that induced lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), which counteracts lipid-induced ER stress by synthesizing phosphatidylcholine that contains unsaturated fatty acids[8].

PERK signaling also regulates TAM function. Another seminal study recently demonstrated that polarization towards an “M2-like” phenotype coincided with elevated PERK signaling in comparison with naïve or “M1-like” macrophages, and PERK-deficient macrophages showed impaired M2 polarization in a B16-F10 melanoma model[9]. Importantly, PERK-directed metabolic reprogramming of TAMs was found to proceed via ATF4-mediated stimulation of serine biosynthesis, which supported M2 polarization[9]. Mechanistically, PERK-deficient TAMs expressed reduced levels of phosphoserine aminotransferase 1 (PSAT1) that is important for serine biosynthesis, resulting in decreased mitochondrial fitness and major epigenetic alterations[9]. Inhibition of PERK in TAMs therefore delayed tumor growth, increased T cell infiltration, and improved the effects of anti-PD-1 treatment[9].

Dendritic cells (DCs)

ER stress responses blunt intratumoral DC function[10]. Ovarian cancer-associated DCs were first demonstrated to exhibit robust IRE1α-XBP1s activation fueled by ROS accumulation and generation of lipid peroxidation byproducts that caused ER stress[11]. In this setting, XBP1s induced a transcriptional lipogenic program leading to uncontrolled accumulation of cytosolic lipid droplets that impaired normal antigen presentation to T cells[11]. Genetic abrogation of IRE1α or XBP1s enhanced intratumoral DC function, leading to improved adaptive immune responses and extended host survival in multiple mouse models of ovarian cancer[11]. Subsequent studies showed that treatment of mice bearing ID8-based ovarian cancer with nanoemulsions containing the IRE1α inhibitor KIRA6 and the ROS scavenging agent α-Tocopherol reduced tumor growth[12].

Most recently, antigenic peptides were reported to directly activate IRE1α in DCs, a process that caused RIDD-driven downregulation of MHC-I molecules[13]. Abrogating IRE1α function in DCs was found to alleviate RIDD and increase their capacity to present antigens to T cells[13]. In this study, systemic pharmacological inhibition of the IRE1α kinase domain using the small molecule G9668, improved anti-tumor responses and augmented the efficacy of checkpoint blockers in syngeneic mouse models of breast cancer[13]. Whether these therapeutic effects are mediated by restored intratumoral DC function and/or enhanced adaptive immunity was not established and deserves further investigation.

DCs lacking BAT3, an adaptor protein that binds to TIM-3 on T cells, exhibited UPR overactivation resulting in a tolerogenic phenotype that impaired anti-tumor T cell responses[14]. UPR activation was observed in BAT3-deficient DCs as this factor operates as an ER chaperone involved in the quality control of newly synthesized proteins[14]. DCs isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of MC38-bearing mice had low BAT3 expression compared with splenic naïve DCs, which was proposed to promote tumor growth[14]. Of note, BAT3-null bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDCs) displayed reduced expression of costimulatory molecules that could be restored upon treatment with the ER stress-mitigating chemical chaperone 4BPA or the IRE1α inhibitor 4μ8C[14]. Finally, UPR activation evoked by BAT3 deficiency altered DC metabolism by redirecting Acetyl-CoA towards immunosuppressive glucocorticoid production[14]. It remains unknown whether PERK and/or ATF6 signaling also mediate the tolerogenic activity of BAT3-deficient DCs undergoing ER stress. Taken together, these studies demonstrate that controlling abnormal IRE1α signaling in intratumoral DCs emerges as a major opportunity to boost endogenous antitumor immunity and enhance the effects of cancer immunotherapy.

Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs consist of immature myeloid cells that exert T cell-suppressive activity[15–17]. In this population, PERK enforces mitochondrial DNA integrity, hence supporting immunosuppressive MDSC function in multiple tumor models[18]. Targeting PERK provoked NRF2-dependent disruption of mitochondrial functionality, subsequent release of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol, and MDSC reprogramming via mtDNA-induced STING activation[18]. Downstream of PERK, ablation of CHOP or ATF4 in the stroma of different tumor models attenuated the immunosuppressive function of MDSCs by reducing TME-induced C/EBPβ expression, phospho-STAT3 and IL-6[19]. Deletion of the nutrient-sensing kinase GCN2 that phosphorylates eIF2α similarly impaired ATF4 activation and therein MDSC and TAM suppressive function[20]. Furthermore, the long non-coding RNA lnc-chop interacted with CHOP to enhance the suppressive function of MDSCs in the TME by increasing expression of ARG1, inducible nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2)[21]. Yet, a recent report showed that global CHOP deficiency did not alter the immunosuppressive activity of either monocytic or polymorphonuclear MDSCs (M-MDSCs or PMN-MDSCs, respectively)[22]. In addition, the immunosuppressive activity of PMN-MDSCs, but not M-MDSCs, was found to rely on IRE1α and ATF6. Intriguingly, loss of either of these ER stress sensors in myeloid cells – by using genetic mouse models that express Cre recombinase under control of the Lyz2 promoter – resulted in delayed MC38 colon carcinoma growth but did not alter the progression of Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC)[22]. Additional research is needed to discern whether these differences are due to changes in the abundance of TAMs, which are also impacted by the loss of IRE1α and ATF6 in these models, or solely dependent on modulation of MDSC activity.

PERK activation in splenic hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) has also been shown to promote tumor progression in a hepatoma model[23]. Mechanistically, stromal-derived IL-6 induced PERK-ATF4-C/EBPβ signaling in HSPCs that skewed their differentiation towards MDSCs. Accordingly, spleen-directed delivery of the PERK inhibitors AMG-PERK-44 or GSK2606414 elicited robust tumor control. Treatment with PERK inhibitors was ineffective in splenectomized mice, highlighting the detrimental role of PERK activation in splenic MDSCs[23].

T cells

TME-induced ER stress is a crucial mediator of intratumoral T cell dysfunction [24, 25]. In ovarian cancer, T cells demonstrated impaired glucose uptake and dysregulated N-linked protein glycosylation, resulting in aberrant IRE1α-XBP1s signaling. In this setting, maladaptive XBP1s activation hindered glutamine intake and thus inhibited the use of glutamine as an alternative carbon source for mitochondrial respiration in the absence of glucose, resulting in IRE1α-XBP1s-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction and impaired anti-tumor activity[26]. Using an intravenous B16-F10 melanoma model, another study reported that intratumoral CD8+ T cells accumulated cholesterol that induced expression of the inhibitor receptors PD-1 and 2B4, and promoted T cell exhaustion in a XBP1s-dependent manner[27]. Therein, XBP1s deletion in T cells increased their anti-tumor function and prolonged survival compared with their wild-type counterparts[26, 27]. While the underlying mechanism remains elusive, it is possible that CD36-mediated uptake and accumulation of oxidized low-density lipoproteins may induce T cell ferroptosis and/or severe ER stress accounting for the observed CD8+ T cell dysfunction[28, 29].

Activation of the PERK downstream target CHOP in intratumoral T cells further impairs their effector function in murine ovarian cancer and other tumor models. High expression of CHOP in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells was associated with poor clinical outcome in ovarian cancer patients[30]. Ablation of CHOP in CD8+ T cells restored antitumor immunity via derepression of the transcription factor T-bet, a master inducer of Type-1 anti-tumor immunity[30]. In tumor antigen-specific T cells, chronic PERK activation coincided with impaired mitochondrial fitness. Abrogating PERK activity in T cells thus resulted in decreased mitochondrial ROS and enhanced antitumor efficacy in vivo[31]. Interestingly, while persistent PERK signaling restricts mitochondrial fitness, acute PERK activation induced by carbon monoxide temporarily halted protein translation, induced protective mitophagy and mitochondrial function, and promoted anti-tumor T cell activity in B16-F10 melanoma[32].

While it is unclear whether UPR activation impacts the function of regulatory T cells (Treg) in cancer, some reports indicate that ER stress might modulate the biology of this T cell subset. In both human and mouse Tregs, induction of ER stress by the pharmacological ER stressor thapsigargin enhanced production of TGF-β and IL-10, which was mitigated after inhibition of PERK or eIF2α[33, 34]. Thus, it is likely that TME-induced ER stress may augment the immunosuppressive function of Tregs residing in this milieu.

NK cells

IRE1α-XBP1s was found to mediate optimal NK cell proliferation in part by promoting MYC expression[35]. Hence, in models of viral infection and cancer where NK cells mediate protective effects, loss of IRE1α in these cells resulted in decreased NK cell infiltration, increased tumor burden, and reduced host survival compared to their wild type counterparts[35]. Additional research is necessary to evaluate if IRE1α inhibitors can alter NK cell proliferation and/or function in cancer models.

B cells

XBP1s plays a critical role in the development of antibody-secreting plasma cells and in the secretion of immunoglobulin M (IgM)[36]. Genetic ablation of XBP1s was found to cause IRE1α phosphorylation on its S729 residue and thereby RIDD that blunted expression of the secretory μ heavy chain, thus impairing IgM secretion by B cells [37, 38]. Recent findings showed that secretory IgM promotes the immunosuppressive functions of MDSCs in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and LLC mouse models. Hence, genetic loss of XBP1s controlled this detrimental process and elicited T cell-mediated tumor control[39]. Whether canonical ER stress alters the function of tumor-infiltrating B cells has not been established and deserves further investigation.

Disabling the UPR in cancer cells: new developments and therapeutic vulnerabilities

Due to adverse environmental conditions, metabolic changes, and oncogenic pathways, cancer cells also experience ER stress in the TME. Transformed cells can usurp the UPR as a major adaptive mechanism that promotes their aggressive behavior[1]. The UPR has also been documented to mediate cancer cell chemoresistance, which has been reviewed elsewhere [1, 43]. Hence, global UPR signatures show relevant prognostic value in several malignancies, such as osteosarcoma, breast, and bladder cancer[40–42]. This section summarizes new discoveries on the role of ER stress responses in the cancer cell and highlight specific genetic alterations that sensitize tumors to UPR-targeted therapies (Figure 2).

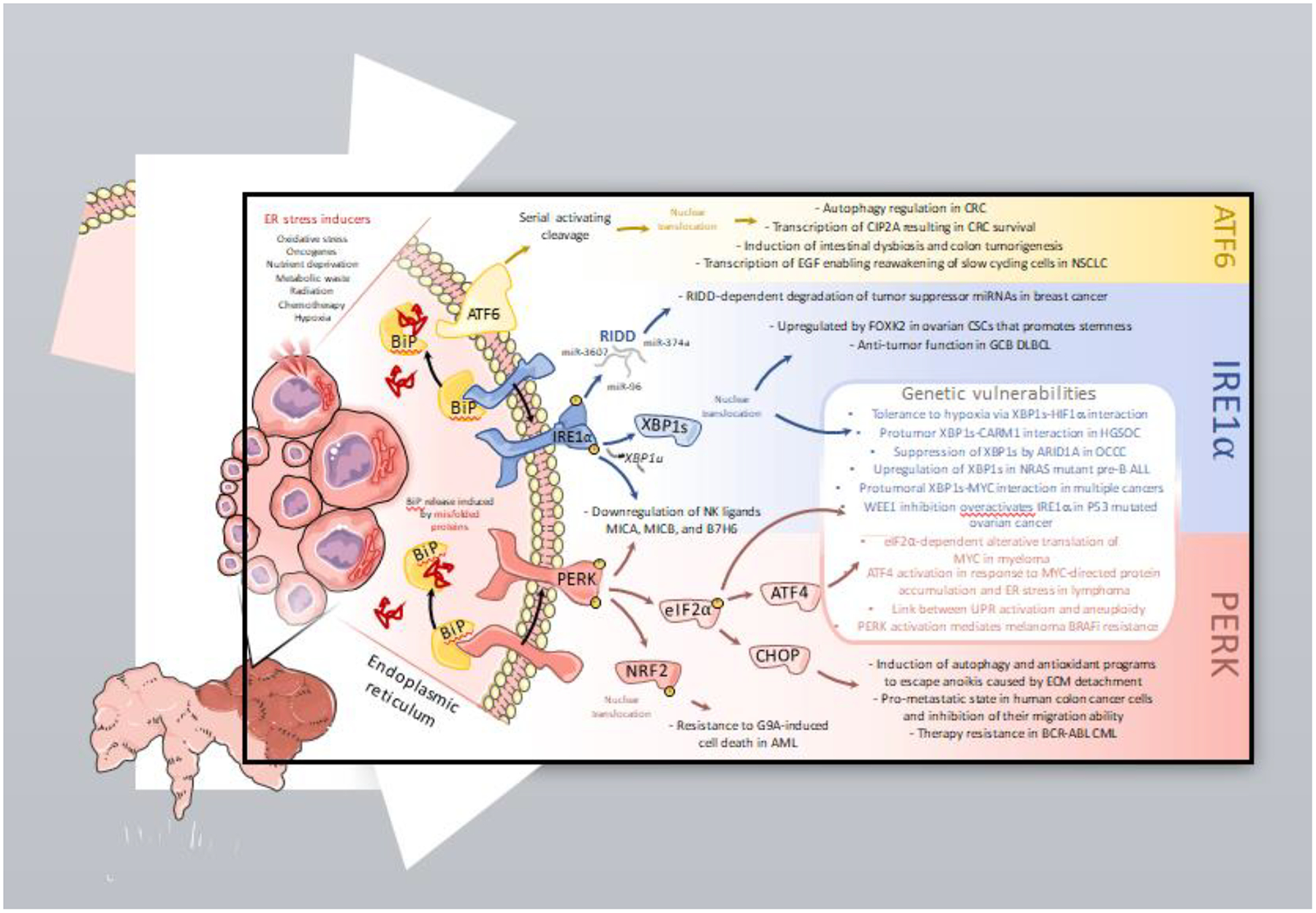

FIGURE 2: The UPR as a targetable codependency in cancer.

Malignant cells exploit the UPR as an adaptive, prosurvival mechanism. Hence, overactivation of ER stress response pathways in the cancer cell has been demonstrated to directly promote tumor growth, metastasis, and resistance to therapy. Recent findings further underscore that distinct genetic features in the cancer cell can be harnessed to sensitize tumors to UPR therapeutic modulation.

ATF6: In colorectal cancer, ATF6 induces transcription of autophagy-related genes and oncogene cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (CIP2A), expression of which corresponds to a poor overall prognosis. Constitutive ATF6 activation also promotes intestinal dysbiosis and colon tumorigenesis. Additionally, ATF6 enables reawakening of slow-cycling cells in non-small cell lung cancer.

IRE1α: IRE1α degrades critical tumor-suppressor miRNAs such as miR-3607, miR-374a and miR-96 in breast cancer cells through its RNase activity. In germinal-center B-cell like (GCB) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), IRE1α prompts XBP1s-mediated antitumor activity. Conversely, in ovarian cancer stem cells, FOXK2-mediated IRE1α-XBP1s activation directs the expression of stemness-related genes. Activation of both IRE1α and PERK decreases surface expression of stress-induced ligands such as MICA, MICB, and B7H6 on melanoma cells, allowing them to evade killing by NK cells.

PERK: PERK-driven CHOP induces autophagy and antioxidant programs that enable cancer cells to escape anoikis caused by extracellular matrix (ECM) detachment. Furthermore, PERK signaling in colon cancer supports a premetastatic state and promotes therapy resistance in BCR-ABL fusion chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Activation of NRF2, downstream of PERK, enables resistance to G9A-induced cell death in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Genetic vulnerabilities: IRE1α-XBP1s is a crucial co-dependency in cancer cells with specific genetic contextures. XBP1s and HIF1α cooperate to increase hypoxia tolerance in breast tumors, while XBP1s and CARM1 interact to drive protumorigenic functions in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC). The MYC-IRE1α-XBP1s axis further sculpts the aggressive phenotype of diverse cancer cell types. Loss of ARID1A unleashes protumoral IRE1α-XBP1s activity in ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC). NRAS-mutant pre-B cell acute lymphocytic leukemia (pre-B ALL) exhibits increased XBP1s expression that contributes to malignant progression. Pharmacological inhibition of the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint kinase, WEE1, induces pro-apoptotic PERK and pro-survival IRE1α activation in ovarian cancer cells bearing P53 mutations, which are therefore sensitized to IRE1α inhibition. PERK signaling is another major MYC co-dependency in cancer. MYC directs protein accumulation, resulting in ER stress, and ATF4 activation in lymphoma. PERK-driven eIF2α phosphorylation enables alternative translation of MYC, supporting its protumoral role. PERK activation mediates resistance to BRAF inhibition (BRAFi) through activation of ERK and induction of protective autophagy. Finally, using the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, a recent report linked the activation of multiple branches of the UPR as the result of aneuploidy in cancer cells.

Global effects of the UPR in cancer cells

The IRE1α-XBP1s axis facilitates cancer cell proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and drug resistance[44]. IRE1α-XBP1s signaling also promotes tolerance to hypoxia. In triple-negative breast cancer, XBP1s drives tumorigenesis by interacting with hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α (HIF1α) to stimulate transcription of HIF1α target genes [45]. Furthermore, in colon cancer cells, hypoxia-induced ER stress caused decreased WNT/β-catenin signaling, which resulted in XBP1s-mediated transcription of prosurvival hypoxia response genes[46]. IRE1α-XBP1s also contributes to stemness maintenance in ovarian cancer stem cells (CSC)[47]. In human ovarian CSCs, binding of the transcription factor FOXK2 to a regulatory element of ERN1 increased IRE1α levels and facilitated XBP1s-directed induction of stemness-related genes[47].

Recent studies also pinpoint RIDD to play a role in tumor progression. In luminal breast cancer, IRE1α degraded several protumorigenic microRNA (miRNAs), such as miR-3607, miR-374a, and miR-96, leading to the expression of RAS oncogene GTPase, RAB3B[48]. In contrast, in glioblastoma, IRE1α-XBP1s controlled pro- and anti-tumor effects via regulation of macrophage infiltration, and tumor invasion and angiogenesis, respectively[49]. Patients with a high XBP1s signature and a low RIDD signature showed worse survival, suggesting that the balance between these two pathways could have prognostic value[49].

Paradoxical antitumor roles for IRE1α-XBP1s have been described in germinal center B-cell–like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (GCB-DLBCL) wherein exogenous expression of XBP1s in GCB-DLBCL cells delayed tumor growth in a xenograft model[50]. This study highlights that types and subtypes of cancer may respond differently to IRE1α inhibitors. Hence, additional studies are needed to identify the range of cancer types that would be amenable to therapeutic UPR modulation.

PERK plays a bifunctional role in directing protumor and antitumor responses depending on the duration and magnitude of ER stress. Transient activation of PERK in cancer cells stimulated the pro-survival PERK-ATF4-NRF2 axis, while sustained ER stress directed pro-apoptotic PERK-ATF4-CHOP signaling[51]. Additionally, the paradoxical effects of PERK in cancer cell survival are partly explained by expression of miR-211. Upon ER stress, PERK-ATF4 induces miR-211, which in turn attenuates stress-dependent expression of pro-apoptotic CHOP. However, if PERK activation is severe, miR-211 is not expressed, thereby resulting in CHOP-mediated apoptosis[52]. CHOP also promotes apoptosis through induction of miR-216b that subsequently suppresses pro-survival c-Jun expression[53]. Importantly, this finding could explain the primary role of PERK-associated eIF2α phosphorylation in the pro-survival vs. induction of immunogenic cell death (ICD) of tumor cells after treatment with specific anti-cancer agents[54]. The additional potential effect of the expression of type-I interferon (IFN) receptor in the pro-survival vs. pro-apoptotic effects of PERK on tumor cells have been described[55], and deserve additional research.

Oncogenic signaling evokes cellular stress. The first evidence linking oncoproteins and ER stress was observed in CLL, where the T Cell Leukemia/Lymphoma 1 (TCL1) oncoprotein associated with XBP1s[56]. Hence, genetic or pharmacological inhibition of XBP1s expression resulted in decreased CLL progression[56, 57]. Additionally, stress-mitigating programs such as those directed by PERK are critical for the survival of transformed cells. This paradigm is exemplified by the BCR-ABL fusion that, when expressed in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), induced ER stress and subsequent activation of PERK-eIF2α. PERK activation triggered survival of transformed cells, while PERK inhibition sensitized CML to imatinib treatment[58]. Similarly, in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), drugs targeting the histone methyltransferase G9A provoked oxidative stress, which was mitigated by activation of PERK and NRF2. Thus, PERK signaling enabled AML cells to escape G9A inhibitor-induced cell death[59]. Moreover, extracellular matrix (ECM) detachment provoked significant stress in ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) cells. Activation of PERK during ECM detachment reduced toxic ROS and promoted autophagy, which enabled DCIS to escape detachment-associated cell death (anoikis)[60]. Also, a recent report identified the occurrence of a pro-metastatic state upon impending cell death in human colon cancer cells, which is characterized by enhanced ER stress, stemness, and cytokine storm[61]. While PERK-CHOP activation was key for the acquisition of the pro-metastatic state, PERK inhibition increased cell migration, suggesting that cells need to resolve ER stress prior to undergoing metastasis[61].

Interestingly, the UPR can also modulate cancer cell recognition by immune cells. In particular, IRE1α-XBP1s and PERK activation in melanoma cells has been shown to suppress the expression of stress-induced ligands for NK cells, such as major histocompatibility complex class I polypeptide-related sequence A and B (MICA and MICB)[62] and B7 homolog 6 (B7H6)[63], thus inhibiting NK cell-mediated killing of cancer cells.

The role of cancer cell-intrinsic ATF6 in tumors remains largely unexplored. Current research on ATF6 in cancer has focused on how the prosurvival functions of this transcription factor can be co-opted to support tumor growth, malignant progression, and chemoresistance, while also contributing to autophagy regulation and oncogenic microbial dysbiosis[64, 65]. In p53-mutant triple negative breast cancer, selective activation of ATF6 promoted cancer cell survival and tumor progression[66]. In colon cancer cells, ATF6 upregulated oncogene cancerous inhibitor of protein phosphatase 2A (CIP2A) by binding to its promoter[67]. High expression of both ATF6 and CIP2A was associated with poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients[67]. Additionally, in cervical cancer cells, ATF6 activation promoted EMT, cell migration, and cell survival in vitro[65]. Another study identified ATF6, and mutations associated with increased expression of ATF6, as a marker of decreased survival in colorectal cancer patients[64]. Mice with constitutive intestinal epithelial deletion of ATF6 had elevated proliferation of intestinal epithelia, adenoma formation, and marked changes in the gut microbiota composition, coincident with loss of mucus membrane integrity and intraepithelial bacteria penetration. Treatment of mice with antibiotics, or gnotobiotic housing, prevented tumorigenesis. Mechanistically, infiltrating bacteria sustained TLR-mediated STAT3 activation[64]. These findings indicated that ATF6 contributes to changes in the permeability of intestinal epithelia, allowing infiltration of tumorigenic bacteria[64]. Furthermore, ATF6 signaling provoked the awakening of slow cycling non-small cell lung cancer cells via EGF upregulation, and stimulated angiogenesis[68].

Genetic vulnerabilities that render tumors dependent on optimal UPR signaling

Although it was proposed that premalignant melanocytes rely on the UPR to induce oncogene-induced senescence and prevent melanoma development[69], additional research focused on later stages of malignant progression indicates that targeting dysregulated ER stress responses can be used as a general anti-cancer strategy. Importantly, recent studies have further revealed that specific genetic alterations in cancer cells (Figure 2) may dictate the therapeutic efficacy of UPR modulators, hence enabling the development of new precision immuno-oncology approaches.

MYC.

MYC functions as a major transcriptional regulator and oncogene in multiple tumor types[70]. In the context of ER stress, KRAS-independent activation of MYC signaling in pancreatic cancer is reported to induce accumulation of protein aggregates, activation of the IRE1α-MKK4-JNK pathway, and potential sensitization to UPR-targeted therapies[71]. Additionally, studies in breast cancer and Burkitt’s lymphoma models demonstrated crucial roles for MYC in the UPR: First, it induces transcription of ERN1[72, 73], XBP1, and HSPA5[72]. Second, it forms a complex with XBP1s, increasing its gene-inducing activity[73]. Third, it regulates IRE1α stability and RNase activity[72]. Also, the IRE1α-XBP1s pathway induced stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) transcription, which preserved ER homeostasis and prevented cytotoxic ER stress[72]. Disabling IRE1α-XBP1s signaling therefore decreased tumor growth, revealing that MYC overexpression sensitizes tumors to IRE1α inhibitors[72, 73]. Notably, XBP1s also controlled the transcription of MYC in prostate cancer cells by directly binding to MYC responsive elements in its 5’ flanking region[74].

The PERK-eIF2α arm also contributes to MYC regulation. In multiple myeloma, PERK-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α activates cap-independent translation of MYC due to the presence of upstream open reading frame (uORF) and internal ribosome entry site (IRES) motifs in the MYC mRNA[75–77]. Therein, targeting of IRES-mediated MYC translation synergized with ER stress-inducing agents resulting in killing of multiple myeloma cells[77]. Interestingly, MYC-induced elevation of protein translation drives ER enlargement, UPR activation, PERK phosphorylation and ATF4 expression in lymphoma models[78, 79]. In this context, genetic knockout of ATF4 or PERK delayed tumor initiation of MYC mutant lymphomas and prolonged host survival[78, 79].

CARM1.

While coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1) was first discovered as an arginine-methylation associated transcription co-regulator, recent studies identified several protumor roles for CARM1 in cancer[80]. Indeed, CARM1 is overexpressed in ~10% of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma (HGSOC)[81] wherein CARM1 directly interacts with XBP1s during stress and regulates expression of XBP1s-target genes[82]. Immunocompromised mice orthotopically injected with CARM1-high ovarian cancer cells demonstrated improved therapeutic responses to the IRE1α RNase inhibitor B-I09, compared with mice bearing CARM1-low ovarian tumors[82]. In this important study, the authors further observed an additive effect of B-I09[57] and PD-1 blockade in immunocompetent tumor-bearing mice[82], likely because systemic IRE1α inhibition concomitantly disables this regulatory pathway in intratumoral immune cells. Nonetheless, it remains to be determined whether other CARM1-overexpressing tumor types also demonstrate sensitivity to IRE1α abrogation.

ARID1A.

AT-rich interacting domain−containing protein 1A (ARID1A) is a subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex. The gene encoding this factor is mutated in >50% of ovarian clear cell carcinoma (OCCC), with most mutations resulting in loss of protein expression[83, 84]. In OCCC cells, ARID1A functions as a repressor of the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway. ARID1A-deficient cells demonstrated overactivation of this UPR branch and where highly susceptible to its therapeutic inhibition[85]. Indeed, in ARID1A-mutant OCC models, ablating XBP1s or IRE1α increased host survival compared to control mice[85]. Notably, the authors show an additive therapeutic effect of combining B-I09 with an HDAC6 inhibitor, which increased ER stress in the cancer cell while concomitantly decreasing XBP1s expression[85]. Future studies are needed to understand the mechanism of action of this combination treatment since HDAC6 is involved in multiple biological pathways.

KRAS and NRAS.

KRAS-mutant lung cancer cells were found to be susceptible to treatment with Verteporfin, a yes-associated protein 1 (YAP1) inhibitor, whereas cells with wild-type KRAS did not[86]. Interestingly, verteporfin effect on mutated KRAS cells primarily relied on induction of global ER stress that resulted in cell apoptosis[86]. Hence, this study demonstrated that lethal ER stress can be induced specifically in cancer cells harboring KRAS mutations as a strategy to control tumor growth. Cancers with activating NRAS mutations, which are found in 30% of pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (pre-B ALL), may also be susceptible to UPR modulation. In an IL-7 receptor-dependent NRASG12D-driven pre-B ALL model, mutated NRAS upregulated XBP1. Ablation of XBP1 induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest, and IRE1α inhibition sensitized cells to abrogation of PI3K/mTOR, a pathway that acts downstream of both IL-7R and RAS signaling[87].

BRAF.

Despite the critical role of BRAF-associated signaling in melanoma, most patients eventually progress after BRAF inhibitor (BRAFi) therapy[88]. PERK activation has been shown to play a critical role in the induction of cytoprotective autophagy and transient survival in BRAFV600E melanoma cells after treatment with BRAFi[89]. Indeed, targeting components of the PERK and autophagy pathways can overcome BRAFi resistance in melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, PERK-directed ERK phosphorylation and induction of ATF4-driven protective autophagy programs mediated BRAFi resistance[90]. Notably, the PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 arm of the UPR also controlled cytoprotective autophagy in MYC-dependent transformation and tumor growth[78, 91], indicating the critical role of PERK in the promotion of autophagy under oncogenic driver activity.

P53.

Besides regulating several biological functions such as DNA repair and apoptosis, P53 controls cell cycle at the G1/S phase. Mutations in this gene force cells to repair their DNA at the G2/M phase, making regulatory proteins in this checkpoint, such as the protein kinase WEE1, an attractive therapeutic target[92]. Treatment with the small-molecule WEE1 inhibitor AZD1775 induced PERK and IRE1α activation only in ovarian cancer cells with mutated, but not intact P53[93]. While PERK-CHOP induced a pro-apoptotic signal, IRE1α triggered a pro-survival program in this context. Hence, concomitant treatment with AZD1775 and the IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 in mice bearing patient-derived ovarian cancer xenografts with mutant P53 resulted in additive therapeutic benefit[93]. Although genetic knockdown of P53 did not evoke UPR activation, future studies should focus on defining the specific P53 mutations that sensitize tumors to combined WEE1 and IRE1α inhibition.

Tumor aneuploidy.

Aneuploidy is a chromosomal somatic copy number alteration associated with poor prognosis in many types of cancer. Recent reports linked UPR activation with aneuploidy in cancer cells and demonstrated that soluble factors from aneuploid cells can induce XBP1s in BMDMs, inducing suppressive factor production and repression of T cell function[94].

Concluding remarks

Tumors exploit the UPR to mitigate ER proteotoxic stress, making it a relevant target for therapeutic intervention. Indeed, various UPR modulators are currently undergoing human clinical trials: The IRE1α inhibitor MKC8866 is being tested in patients with solid cancer as a single agent and in treatment-refractory metastatic breast cancer patients in combination with paclitaxel (NCT03950570), and preliminary results indicate acceptable tolerability of the drug[95]. Preclinical research has demonstrated the efficacy of PERK inhibitors in multiple tumor models[96–100]. However, early generations of PERK inhibitors demonstrated significant issues in both selectivity and pancreatic toxicity, which depended on type-I IFN expression[101, 102]. Newer generations of PERK inhibitors demonstrate superior selectivity and improved safety profiles[18, 103]. PERK inhibitors, including HC-5404-FU and NMS-03597812 are undergoing phase I clinical trials in patients with solid tumors (NCT04834778) or with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (NCT05027594), respectively. Additionally, targeting BiP with the ruthenium-based small molecule KP1339 stimulated ICD in a colon cancer cell line-derived 3D spheroid and, in a phase I clinical study, induced disease control in 26% of patients with advanced solid tumors[104, 105]. Inducing irresolvable, lethal, ER stress in malignant cells by activating the UPR may represent another strategy for tumor control. For example, HA15 is a BiP inhibitor tested in preclinical models of melanoma that inhibited tumor growth by inducing cell apoptosis and autophagy due to terminal ER stress[106]. Other compounds triggering the UPR have been identified, such as the IRE1α-XBP1s activator IXA4, the PERK activator MK-28, and the ATF6 activator AA147[107], but their in vivo anti-tumor activity still needs to be defined.

Multiple UPR-related gene signatures have been developed to test their association with clinical outcome and prognosis in cancer patients [1, 108, 109]. Most of these signatures have been generated from bulk RNA sequencing data and thus incompletely capture differences in UPR signaling that occur at the single-cell level. Hence, current advances in single-cell technologies combined with Cellular Indexing of Transcriptomes and Epitopes by Sequencing (CITE-seq)[110] provide an exciting opportunity to analyze heterogeneous UPR signatures in diverse cell types co-existing in the same TME. Generation of cell type-specific UPR signatures may therefore provide new opportunities to identify novel factors associated with response and/or resistance to therapy, better understand tumor cell clonal evolution, and discern mechanisms underlying the dichotomous impact of UPR signaling in cancer.

Defining the precise ER stress signals that are activated in different neoplasms based on their location, subtype, genetic make-up, infiltrating immune populations, and prior treatment status, should make UPR-targeting drugs more effective and enable the use of these agents for personalized cancer treatment, especially in combination with other immunotherapeutic modalities (See Outstanding Questions).

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS:

Could the magnitude of ER stress determine the neoantigen repertoire of cancer cells during tumor progression and/or therapy?

Can discrete genetic or metabolic vulnerabilities in cancer cells be exploited to enhance responsiveness to UPR-targeted therapies or chemo-immunotherapy combinations?

Does differential activation of ER stress sensors contribute to distinct intratumoral immune landscapes, including immunologically “cold” versus “hot” tumor states?

Can single-cell UPR-derived gene signatures be developed to predict response or resistance to immunotherapy or targeted cancer therapy?

HIGHLIGHTS:

ER stress-driven activation of ATF6, IRE1α, and PERK coordinates complex pro- and anti-tumor signaling pathways.

Persistent ER stress signaling can shape the function of intratumoral immune cells and dictate anti-tumor immunity.

Discrete genetic vulnerabilities, including alterations in AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A), coactivator associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1), and proto-oncogene MYC, among others, sensitize cancer cells to UPR-targeted therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

C.S. has been supported by the Mentored Investigator Award of the Ovarian Cancer Research Alliance [648859], and by the Cancer Research Institute-Irvington Institute Postdoctoral Fellowship [Award #3443]. Research in the Rodriguez laboratory has been supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01-CA184185, R01-CA233512, R01-CA262121, P01-CA250984 Project #4, and P30-CA076292; and by Florida Department of Health grant #20B04. Research in the Cubillos-Ruiz laboratory has been supported by US Department of Defense Grants W81XWH-16-1-0438, OC190443, OC200166 and OC200224; NIH grants R01NS114653 and R21CA248106; Stand Up to Cancer, The Pershing Square Foundation, and The Mark Foundation for Cancer Research.

GLOSSARY:

- Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6)

ATF6 is an ER localized bZIP family transcription factor encoded by ATF6. In response to ER stress, ATF6 translocates to the nucleus to direct adaptive and prosurvival transcriptional programs

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

The ER is a central cellular organelle that governs the optimal folding and modification of transmembrane and secreted proteins. Disruption of ER homeostasis causes “ER stress”

- Inositol requiring enzyme 1 α (IRE1α)

Encoded by ERN1, IRE1α is an ER-localized dual enzyme with ribonuclease and kinase activities. Normally activated under ER stress, IRE1α coordinates degradation of excess mRNA via regulated IRE1 dependent decay (RIDD) while inducing the activation of the multitasking transcription factor XBP1s. These functions aim at restoring ER proteostasis

- Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are an immature myeloid subset that exerts protumor and immunosuppressive functions

- Protein kinase (PKR)-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK)

PERK is a dual protein and lipid kinase which, in response to ER stress, regulates induction of alternative translation and downstream prosurvival signaling

- Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

TAMs are macrophage residing in the tumor, which in most cancer types exert protumor functions

- Tumor microenvironment (TME)

A localized niche within solid malignant masses containing cancerous and non-cancerous cells

- Unfolded protein response (UPR)

A signaling pathway that can induce either adaptive or pro-apoptotic cellular responses depending on the nature, magnitude, and duration of the ER stress

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: J.R.C-R. is a scientific consultant for NextRNA Therapeutics, Inc., and Autoimmunity Biologic Solutions, Inc. P.R. and J.R.C-R. hold patents on the targeting of ER stress pathways for the treatment of disease.

REFERENCES:

- 1.Chen X and Cubillos-Ruiz JR (2021) Endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer 21, 71–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantovani A, et al. (2017) Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14, 399–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan D, et al. (2016) STAT3 and STAT6 Signaling Pathways Synergize to Promote Cathepsin Secretion from Macrophages via IRE1alpha Activation. Cell Rep 16, 2914–2927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, et al. (2021) XBP1 regulates the protumoral function of tumor-associated macrophages in human colorectal cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6, 357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batista A, et al. (2020) IRE1alpha regulates macrophage polarization, PD-L1 expression, and tumor survival. PLoS Biol 18, e3000687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinon F, et al. (2010) TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat Immunol 11, 411–418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilardini Montani MS, et al. (2020) KSHV infection skews macrophage polarisation towards M2-like/TAM and activates Ire1 alpha-XBP1 axis up-regulating pro-tumorigenic cytokine release and PD-L1 expression. Br J Cancer 123, 298–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Conza G, et al. (2021) Tumor-induced reshuffling of lipid composition on the endoplasmic reticulum membrane sustains macrophage survival and pro-tumorigenic activity. Nat Immunol 22, 1403–1415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raines LN, et al. (2022) PERK is a critical metabolic hub for immunosuppressive function in macrophages. Nat Immunol 23, 431–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovanelli P, et al. (2019) Dendritic Cell Metabolism and Function in Tumors. Trends Immunol 40, 699–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, et al. (2015) ER Stress Sensor XBP1 Controls Anti-tumor Immunity by Disrupting Dendritic Cell Homeostasis. Cell 161, 1527–1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu Y, et al. (2022) Reactivation of dysfunctional dendritic cells by a stress-relieving nanosystem resets anti-tumor immune landscape. Nano Today 43, 101416 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guttman O, et al. (2022) Antigen-derived peptides engage the ER stress sensor IRE1alpha to curb dendritic cell cross-presentation. J Cell Biol 221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu C, et al. (2021) Tim-3 adaptor protein Bat3 is a molecular checkpoint of T cell terminal differentiation and exhaustion. Sci Adv 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Condamine T, et al. (2016) Lectin-type oxidized LDL receptor-1 distinguishes population of human polymorphonuclear myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer patients. Sci Immunol 1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Condamine T, et al. (2014) ER stress regulates myeloid-derived suppressor cell fate through TRAIL-R-mediated apoptosis. J Clin Invest 124, 2626–2639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegde S, et al. (2021) MDSC: Markers, development, states, and unaddressed complexity. Immunity 54, 875–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohamed E, et al. (2020) The Unfolded Protein Response Mediator PERK Governs Myeloid Cell-Driven Immunosuppression in Tumors through Inhibition of STING Signaling. Immunity 52, 668–682.e667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thevenot PT, et al. (2014) The stress-response sensor chop regulates the function and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors. Immunity 41, 389–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halaby MJ, et al. (2019) GCN2 drives macrophage and MDSC function and immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Sci Immunol 4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Y, et al. (2018) Lnc-chop Promotes Immunosuppressive Function of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Tumor and Inflammatory Environments. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 200, 2603–2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tcyganov EN, et al. (2021) Distinct mechanisms govern populations of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in chronic viral infection and cancer. J Clin Invest 131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu M, et al. (2022) PERK reprograms hematopoietic progenitor cells to direct tumor-promoting myelopoiesis in the spleen. J Exp Med 219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blank CU, et al. (2019) Defining ‘T cell exhaustion’. Nat Rev Immunol 19, 665–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thommen DS and Schumacher TN (2018) T Cell Dysfunction in Cancer. Cancer Cell 33, 547–562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Song M, et al. (2018) IRE1alpha-XBP1 controls T cell function in ovarian cancer by regulating mitochondrial activity. Nature 562, 423–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma X, et al. (2019) Cholesterol Induces CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab 30, 143–156 e145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma X, et al. (2021) CD36-mediated ferroptosis dampens intratumoral CD8(+) T cell effector function and impairs their antitumor ability. Cell Metab 33, 1001–1012 e1005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu S, et al. (2021) Uptake of oxidized lipids by the scavenger receptor CD36 promotes lipid peroxidation and dysfunction in CD8(+) T cells in tumors. Immunity 54, 1561–1577 e1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao Y, et al. (2019) ER stress-induced mediator C/EBP homologous protein thwarts effector T cell activity in tumors through T-bet repression. Nat Commun 10, 1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hurst KE, et al. (2019) Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Contributes to Mitochondrial Exhaustion of CD8(+) T Cells. Cancer immunology research 7, 476–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakraborty P, et al. (2022) Carbon monoxide activates PERK-regulated autophagy to induce immunometabolic reprogramming and boost anti-tumor T cell function. Cancer Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng Z. z., et al. (2021) ER stress and its PERK branch enhance TCR-induced activation in regulatory T cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 563, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franco A, et al. (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum stress drives a regulatory phenotype in human T-cell clones. Cell Immunol 266, 1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dong H, et al. (2019) The IRE1 endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor activates natural killer cell immunity in part by regulating c-Myc. Nat Immunol 20, 865–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reimold AM, et al. (2001) Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature 412, 300–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benhamron S, et al. (2014) Regulated IRE1-dependent decay participates in curtailing immunoglobulin secretion from plasma cells. Eur J Immunol 44, 867–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang CH, et al. (2018) Phosphorylation of IRE1 at S729 regulates RIDD in B cells and antibody production after immunization. J Cell Biol 217, 1739–1755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tang CH, et al. (2018) Secretory IgM Exacerbates Tumor Progression by Inducing Accumulations of MDSCs in Mice. Cancer Immunol Res 6, 696–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi C, et al. (2022) A novel prognostic signature in osteosarcoma characterised from the perspective of unfolded protein response. Clin Transl Med 12, e750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhu K, et al. (2021) Identification of a novel signature based on unfolded protein response-related gene for predicting prognosis in bladder cancer. Hum Genomics 15, 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang D, et al. (2017) Comprehensive Analysis of the Unfolded Protein Response in Breast Cancer Subtypes. JCO Precis Oncol 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, et al. (2017) Tumorigenic and Immunosuppressive Effects of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Cancer. Cell 168, 692–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi W, et al. (2019) Unravel the molecular mechanism of XBP1 in regulating the biology of cancer cells. J Cancer 10, 2035–2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, et al. (2014) XBP1 promotes triple-negative breast cancer by controlling the HIF1alpha pathway. Nature 508, 103–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia Z, et al. (2019) Hypoxic ER stress suppresses beta-catenin expression and promotes cooperation between the transcription factors XBP1 and HIF1alpha for cell survival. J Biol Chem 294, 13811–13821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Y, et al. (2022) FOXK2 promotes ovarian cancer stemness by regulating the unfolded protein response pathway. J Clin Invest [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang K, et al. (2020) The UPR Transducer IRE1 Promotes Breast Cancer Malignancy by Degrading Tumor Suppressor microRNAs. iScience 23, 101503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lhomond S, et al. (2018) Dual IRE1 RNase functions dictate glioblastoma development. EMBO Mol Med 10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bujisic B, et al. (2017) Impairment of both IRE1 expression and XBP1 activation is a hallmark of GCB DLBCL and contributes to tumor growth. Blood 129, 2420–2428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rozpedek W, et al. (2016) The Role of the PERK/eIF2alpha/ATF4/CHOP Signaling Pathway in Tumor Progression During Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Curr Mol Med 16, 533–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chitnis NS, et al. (2012) miR-211 is a prosurvival microRNA that regulates chop expression in a PERK-dependent manner. Mol Cell 48, 353–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu Z, et al. (2016) miR-216b regulation of c-Jun mediates GADD153/CHOP-dependent apoptosis. Nat Commun 7, 11422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kroemer G, et al. (2022) Immunogenic cell stress and death. Nat Immunol 23, 487–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhattacharya S, et al. (2013) Anti-tumorigenic effects of Type 1 interferon are subdued by integrated stress responses. Oncogene 32, 4214–4221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kriss CL, et al. (2012) Overexpression of TCL1 activates the endoplasmic reticulum stress response: a novel mechanism of leukemic progression in mice. Blood 120, 1027–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang CH, et al. (2014) Inhibition of ER stress-associated IRE-1/XBP-1 pathway reduces leukemic cell survival. J Clin Invest 124, 2585–2598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kusio-Kobialka M, et al. (2012) The PERK-eIF2alpha phosphorylation arm is a pro-survival pathway of BCR-ABL signaling and confers resistance to imatinib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia cells. Cell Cycle 11, 4069–4078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jang JE, et al. (2020) PERK/NRF2 and autophagy form a resistance mechanism against G9a inhibition in leukemia stem cells. Journal of experimental & clinical cancer research : CR 39, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Avivar-Valderas A, et al. (2011) PERK integrates autophagy and oxidative stress responses to promote survival during extracellular matrix detachment. Mol Cell Biol 31, 3616–3629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Conod A, et al. (2022) On the origin of metastases: Induction of pro-metastatic states after impending cell death via ER stress, reprogramming, and a cytokine storm. Cell Rep 38, 110490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Obiedat A, et al. (2019) Transcription of the NKG2D ligand MICA is suppressed by the IRE1/XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response through the regulation of E2F1. FASEB J 33, 3481–3495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Obiedat A, et al. (2020) The integrated stress response promotes B7H6 expression. J Mol Med (Berl) 98, 135–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coleman OI, et al. (2018) Activated ATF6 Induces Intestinal Dysbiosis and Innate Immune Response to Promote Colorectal Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 155, 1539–1552.e1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu F, et al. (2020) Activating transcription factor 6 regulated cell growth, migration and inhibiteds cell apoptosis and autophagy via MAPK pathway in cervical cancer. Journal of reproductive immunology 139, 103120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sicari D, et al. (2019) Mutant p53 improves cancer cells’ resistance to endoplasmic reticulum stress by sustaining activation of the UPR regulator ATF6. Oncogene 38, 6184–6195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu CY, et al. (2018) ER stress-related ATF6 upregulates CIP2A and contributes to poor prognosis of colon cancer. Mol Oncol 12, 1706–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cho J, et al. (2020) The ATF6-EGF Pathway Mediates the Awakening of Slow-Cycling Chemoresistant Cells and Tumor Recurrence by Stimulating Tumor Angiogenesis. Cancers 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Denoyelle C, et al. (2006) Anti-oncogenic role of the endoplasmic reticulum differentially activated by mutations in the MAPK pathway. Nat Cell Biol 8, 1053–1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dang CV (2012) MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149, 22–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Genovese G, et al. (2017) Synthetic vulnerabilities of mesenchymal subpopulations in pancreatic cancer. Nature 542, 362–366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xie H, et al. (2018) IRE1alpha RNase-dependent lipid homeostasis promotes survival in Myc-transformed cancers. J Clin Invest 128, 1300–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhao N, et al. (2018) Pharmacological targeting of MYC-regulated IRE1/XBP1 pathway suppresses MYC-driven breast cancer. J Clin Invest 128, 1283–1299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheng X, et al. (2019) IRE1alpha-XBP1s pathway promotes prostate cancer by activating c-MYC signaling. Nat Commun 10, 323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fritsch C, et al. (2012) Genome-wide search for novel human uORFs and N-terminal protein extensions using ribosomal footprinting. Genome Res 22, 2208–2218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stoneley M, et al. (1998) C-Myc 5’ untranslated region contains an internal ribosome entry segment. Oncogene 16, 423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shi Y, et al. (2016) Therapeutic potential of targeting IRES-dependent c-myc translation in multiple myeloma cells during ER stress. Oncogene 35, 1015–1024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 78.Hart LS, et al. (2012) ER stress-mediated autophagy promotes Myc-dependent transformation and tumor growth. J Clin Invest 122, 4621–4634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tameire F, et al. (2019) ATF4 couples MYC-dependent translational activity to bioenergetic demands during tumour progression. Nat Cell Biol 21, 889–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suresh S, et al. (2021) CARM1/PRMT4: Making Its Mark beyond Its Function as a Transcriptional Coactivator. Trends Cell Biol 31, 402–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Karakashev S, et al. (2018) CARM1-expressing ovarian cancer depends on the histone methyltransferase EZH2 activity. Nat Commun 9, 631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lin J, et al. (2021) Targeting the IRE1α/XBP1s pathway suppresses CARM1-expressing ovarian cancer. Nature Communications 12, 5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jones S, et al. (2010) Frequent mutations of chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Science 330, 228–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Xu S and Tang C (2021) The Role of ARID1A in Tumors: Tumor Initiation or Tumor Suppression? Front Oncol 11, 745187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zundell JA, et al. (2021) Targeting the IRE1α/XBP1 Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Response Pathway in ARID1A-Mutant Ovarian Cancers. Cancer Research 81, 5325–5335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shimomura I, et al. (2021) Selective targeting of KRAS-driven lung tumorigenesis via unresolved ER stress. JCI Insight 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Appelmann I, et al. (2020) Interplay between PI3K/mTOR Signaling and IRE1a-XBP1 Promotes Survival of Pre-B NRASG12D all Cells Providing a Therapeutic Vulnerability for the “Undruggable” Driver RAS. Blood 136, 47–48 [Google Scholar]

- 88.Luebker SA and Koepsell SA (2019) Diverse Mechanisms of BRAF Inhibitor Resistance in Melanoma Identified in Clinical and Preclinical Studies. Front Oncol 9, 268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ma XH, et al. (2014) Targeting ER stress-induced autophagy overcomes BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma. J Clin Invest 124, 1406–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ojha R, et al. (2019) ER Translocation of the MAPK Pathway Drives Therapy Resistance in BRAF-Mutant Melanoma. Cancer Discov 9, 396–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gui J, et al. (2019) The PKR-Like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase Promotes the Dissemination of Myc-Induced Leukemic Cells. Mol Cancer Res 17, 1450–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Do K, et al. (2013) Wee1 kinase as a target for cancer therapy. Cell Cycle 12, 3159–3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Xiao R, et al. Inhibiting the IRE1α Axis of the Unfolded Protein Response Enhances the Antitumor Effect of AZD1775 in TP53 Mutant Ovarian Cancer. Advanced Science n/a, 2105469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Xian S, et al. (2021) The unfolded protein response links tumor aneuploidy to local immune dysregulation. EMBO Rep 22, e52509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gabrail NY, et al. (2021) A phase 1/2 trial of ORIN1001, a first-in-class IRE1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 39, 3080–3080 [Google Scholar]

- 96.Atkins C, et al. (2013) Characterization of a novel PERK kinase inhibitor with antitumor and antiangiogenic activity. Cancer Res 73, 1993–2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bagratuni T, et al. (2020) Characterization of a PERK Kinase Inhibitor with Anti-Myeloma Activity. Cancers 12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Qin Y, et al. (2021) PERK mediates resistance to BRAF inhibition in melanoma with impaired PTEN. npj Precision Oncology 5, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rozpędek W, et al. (2020) Use of Small-molecule Inhibitory Compound of PERK-dependent Signaling Pathway as a Promising Target-based Therapy for Colorectal Cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 20, 223–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feng Y-X, et al. (2017) Cancer-specific PERK signaling drives invasion and metastasis through CREB3L1. Nature Communications 8, 1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rojas-Rivera D, et al. (2017) When PERK inhibitors turn out to be new potent RIPK1 inhibitors: critical issues on the specificity and use of GSK2606414 and GSK2656157. Cell Death Differ 24, 1100–1110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yu Q, et al. (2015) Type I interferons mediate pancreatic toxicities of PERK inhibition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112, 15420–15425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith A, et al. (2015) Discovery of 1 H -Pyrazol-3(2 H)-ones as Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Protein Kinase R-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase (PERK). Journal of medicinal chemistry 58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Burris HA, et al. (2016) Safety and activity of IT-139, a ruthenium-based compound, in patients with advanced solid tumours: a first-in-human, open-label, dose-escalation phase I study with expansion cohort. ESMO Open 1, e000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wernitznig D, et al. (2019) First-in-class ruthenium anticancer drug (KP1339/IT-139) induces an immunogenic cell death signature in colorectal spheroids in vitro. Metallomics 11, 1044–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cerezo M, et al. (2016) Compounds Triggering ER Stress Exert Anti-Melanoma Effects and Overcome BRAF Inhibitor Resistance. Cancer Cell 30, 183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grandjean JMD and Wiseman RL (2020) Small molecule strategies to harness the unfolded protein response: where do we go from here? J Biol Chem 295, 15692–15711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Feng YX, et al. (2017) Cancer-specific PERK signaling drives invasion and metastasis through CREB3L1. Nat Commun 8, 1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harnoss JM, et al. (2020) IRE1alpha Disruption in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cooperates with Antiangiogenic Therapy by Reversing ER Stress Adaptation and Remodeling the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res 80, 2368–2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stoeckius M, et al. (2017) Simultaneous epitope and transcriptome measurement in single cells. Nat Methods 14, 865–868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Calfon M, et al. (2002) IRE1 couples endoplasmic reticulum load to secretory capacity by processing the XBP-1 mRNA. Nature 415, 92–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Xu Y, et al. (2021) ERalpha is an RNA-binding protein sustaining tumor cell survival and drug resistance. Cell 184, 5215–5229 e5217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hollien J and Weissman JS (2006) Decay of endoplasmic reticulum-localized mRNAs during the unfolded protein response. Science 313, 104–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Haberzettl P and Hill BG (2013) Oxidized lipids activate autophagy in a JNK-dependent manner by stimulating the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. Redox Biol 1, 56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kaneko M, et al. (2003) Activation signal of nuclear factor-kappa B in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress is transduced via IRE1 and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2. Biol Pharm Bull 26, 931–935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Urano F, et al. (2000) Coupling of stress in the ER to activation of JNK protein kinases by transmembrane protein kinase IRE1. Science 287, 664–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Harding HP, et al. (1999) Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature 397, 271–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oyadomari S and Mori M (2004) Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ 11, 381–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cullinan SB, et al. (2003) Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol 23, 7198–7209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, et al. (2012) PERK utilizes intrinsic lipid kinase activity to generate phosphatidic acid, mediate Akt activation, and promote adipocyte differentiation. Molecular and cellular biology 32, 2268–2278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hillary RF and FitzGerald U (2018) A lifetime of stress: ATF6 in development and homeostasis. Journal of Biomedical Science 25, 48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Glembotski CC, et al. (2020) ATF6 as a Nodal Regulator of Proteostasis in the Heart. Frontiers in Physiology 11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Walter F, et al. (2018) ER stress signaling has an activating transcription factor 6α (ATF6)-dependent “off-switch”. The Journal of biological chemistry 293, 18270–18284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]