INTRODUCTION

An estimated 74 million people in the United States live in a jurisdiction that allows Medical Aid in Dying (MAID), and another 87 million reside in 14 states where MAID is on the legislative agenda. 1 As interest in MAID increases, there is a corresponding need for empirical research.

Most research on patients pursuing MAID in the United States has focused exclusively on data from the Pacific Northwest (Oregon and Washington), which is not representative of the entire United States. Although one study showed that individuals with higher income and education access MAID more frequently, 2 no studies have described the demographic and clinical characteristics of individuals pursuing MAID in all jurisdictions that publicly report MAID data. We aggregated data from all nine United States jurisdictions with MAID laws and publicly available records from 1998 to 2020.

METHODS

This study qualified for institutional review board exemption. Nine jurisdictions with legal MAID have published reports. Two investigators reviewed all reports and developed a data abstraction guide. Descriptive statistics were reported. Rates of death by MAID were created using CDC WONDER data.

RESULTS

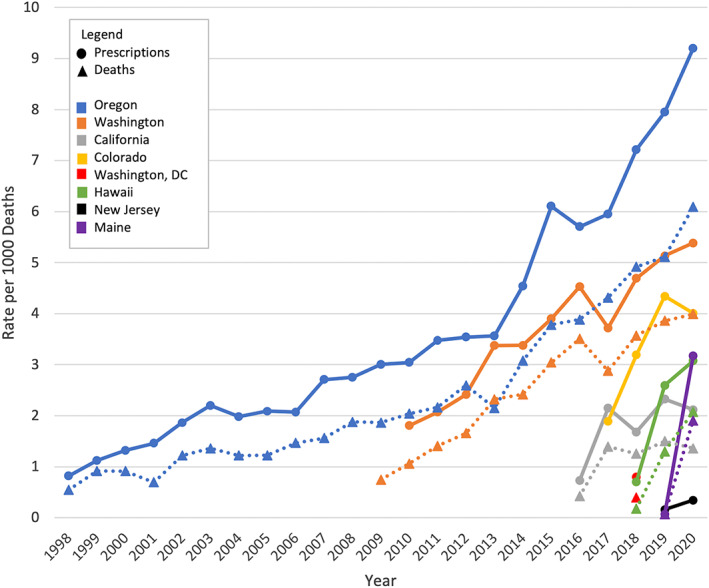

Over 23 years, 5329 patients died by MAID, while 8451 received a prescription. More men than women died by MAID (53.1% vs. 46.9%), and non‐Hispanic white individuals (95.6%) died by MAID more than other racial and ethnic groups. The median age of MAID death was 74. Most (72.2%) had at least some college education and most (74%) had a cancer diagnosis. Most prescription recipients (88.6%) were non‐Hispanic white; 43.3% were 65 or older. Nearly three‐quarters (71.6%) of prescription recipients had at least some college education, and cancer was the most common diagnosis (69.3%) (Table 1). As MAID laws mature, use of MAID increases within the states (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Frequencies and percentages of individuals who died by MAID and individuals who received a MAID prescription

| Characteristics | Category | MAID deaths a | Percentage of deaths | MAID Rx b | Percentage of Rx |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1035 | 53.10% | 2367 | 49.40% |

| Female | 914 | 46.90% | 2252 | 47.00% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.00% | 172 | 3.60% | |

| Race/ethnicity | Non‐Hispanic white | 1864 | 95.60% | 4244 | 88.60% |

| Non‐white | 85 | 4.40% | 351 | 7.30% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.00% | 196 | 4.10% | |

| Age | 18–34 | 155 | 8.00% | 194 | 4.00% |

| 35–44 | |||||

| 45–54 | |||||

| 55–64 | 341 | 17.50% | 519 | 10.80% | |

| 65–74 | 598 | 30.70% | |||

| 75–84 | 538 | 27.60% | 2074 | 43.30% | |

| 85+ | 316 | 16.20% | |||

| Missing | 1 | 0.10% | 2004 | 41.80% | |

| Marital status | Single | 157 | 8.10% | 219 | 4.60% |

| Married | 876 | 44.90% | 1294 | 27.00% | |

| Other | 872 | 44.70% | 1216 | 25.40% | |

| Missing | 44 | 2.30% | 2062 | 43.00% | |

| Underlying medical condition | Cancer | 1442 | 74.00% | 3322 | 69.30% |

| Neurological disease | 212 | 10.90% | 522 | 10.90% | |

| Other | 295 | 15.10% | 809 | 16.90% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.00% | 138 | 2.90% | |

| Insurance status | Public insurance | 1732 | 88.90% | 2980 | 62.20% |

| Private insurance | |||||

| Uninsured | 217 | 11.10% | 569 | 11.90% | |

| Other/Unknown | |||||

| Missing | 0 | 0.00% | 1242 | 25.90% | |

| Family informed | Yes | 1717 | 88.10% | 2910 | 60.70% |

| No | 188 | 9.60% | 184 | 3.80% | |

| Unknown/other | 282 | 5.90% | |||

| Missing | 44 | 2.30% | 1415 | 29.50% | |

| Medication | Sedative | 1311 | 67.30% | 1593 | 33.20% |

| Cardiotonic, opioid, sedative | 572 | 29.30% | 1534 | 32.00% | |

| Other | 22 | 1.10% | 520 | 10.90% | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0.00% | 195 | 4.10% | |

| Missing | 44 | 2.30% | 949 | 19.80% | |

| Hospice enrollment | Hospice/Palliative care c | 1699 | 87.20% | 3022 | 63.10% |

| Not enrolled | 172 | 8.80% | 318 | 6.60% | |

| Unknown | 34 | 1.70% | 189 | 3.90% | |

| Missing | 44 | 2.30% | 1262 | 26.30% | |

| Location of Ingestion | Home | 1758 | 90.20% | NR | NR |

| Other | 147 | 7.50% | NR | NR | |

| Missing | 44 | 2.30% | NR | NR | |

| Educational attainment | No HS | 511 | 26.20% | 1133 | 23.60% |

| High school/GED | |||||

| Some college | 392 | 20.10% | 3429 | 71.60% | |

| Associate's | |||||

| Bachelor's | 874 | 44.80% | |||

| Master's | |||||

| Doctorate/Professional | 142 | 7.30% | |||

| Unknown | 30 | 1.50% | 34 | 0.70% | |

| Missing | 0 | 0.00% | 195 | 4.10% |

Deaths by MAID include data from Oregon, Washington DC, and Hawaii.

MAID prescriptions include data from Washington state, California, Colorado, Vermont, New Jersey, and Maine. NR: not reported.

Hospice and palliative care, while different services, were presented as a combined category in California's data, thus they were combined to present national trends.

FIGURE 1.

Rates of MAID prescription and MAID death per 1000 deaths, by state and year

DISCUSSION

Individuals who die under MAID tend to be older, white, educated, and diagnosed with cancer across all jurisdictions where MAID is legal, extending recently published findings from Oregon and Washington. 2 It is unclear whether these apparent differences result from patient preferences or systemic bias; it is plausible that MAID laws, regulations, and clinical processes have been established that unintentionally make it more difficult for patients with less education, from minority backgrounds, or from non‐cancer diagnoses to participate.

Navigating MAID policies and finding MAID providers may be particularly challenging for individuals with limited resources and high symptom burdens towards the end of life. Most MAID requesters must pay for MAID prescriptions out‐of‐pocket, as Medicare and other federal health insurance programs do not cover aid in dying costs. These out‐of‐pocket costs have risen dramatically, and some drugs are off‐patent but lack generic formulations. 3

Individuals with cancer are over‐represented among MAID utilizers. In the United States, cancer accounted for 17.8% of all deaths in 2020, 4 yet 74% of MAID deaths have a diagnosis of cancer. Disparities in hospice use between cancer and non‐cancer populations are well documented. 5 If hospice and palliative care facilitate MAID access, then patients suffering from other life‐limiting illnesses will continue to have challenges accessing MAID, especially given that MAID, like hospice, requires physician certification of limited life expectancy. Non‐cancer diagnoses, such as heart failure and dementia, are difficult to accurately prognosticate compared to cancer diagnoses, 6 , 7 , 8 which contributes to the lack of education and communication surrounding end‐of‐life options, including MAID. Additionally, treatments for cancer, such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, can be terribly burdensome compared to treatments for non‐cancer diagnoses, which may lead patients with cancer and their doctors to be more likely to consider palliative care, hospice, and MAID. Given the recurrent call for hospice and palliative care to be better integrated into non‐cancer settings, 9 so too should conversations about MAID in order to ensure equal access for patients with all diagnoses.

In conclusion, aggregating data reported from nine jurisdictions over a 23‐year period revealed critically important information on who is utilizing MAID throughout the United States, suggesting potential educational and racial and ethnic disparities. More research is needed to elucidate if these differences are resultant of patient preference or systemic bias in how laws have been written, interpreted, and enacted. As more states plan to adopt MAID legislation, data harmonization will help to elucidate how these policies are being implemented and accessed.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Elissa Kozlov contributed to the study concept and design, interpretation of data, and preparation of the manuscript. Molly Nowels contributed to the study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Michael Gusmano contributed to the study concept and design, interpretation of data, and preparation of manuscript. Hamza Habib contributed to the interpretation of data and preparation of manuscript. Paul Duberstein contributed to the study concept, and design, interpretation of data and preparation of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Elissa Kozlov is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K76AG068508).

SPONSOR'S ROLE

There was no sponsor for this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I attest that I have listed everyone who contributed significantly to the work.

Funding information National Institute on Aging, Grant/Award Number: K76AG068508‐01A1

REFERENCES

- 1. Death with Dignity . In Your State. 2022. Accessed April 5, 2022. https://deathwithdignity.org/states/

- 2. Al Rabadi L, LeBlanc M, Bucy T, et al. Trends in medical aid in dying in Oregon and Washington. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198648. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shankaran V, LaFrance RJ, Ramsey SD. Drug Price inflation and the cost of assisted death for terminally ill patients—death with indignity. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):15‐16. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Murphy SL, Kochanek KD, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;427:1‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cagle JG, Lee J, Ornstein KA, Guralnik JM. Hospice utilization in the United States: a prospective cohort study comparing cancer and noncancer deaths. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(4):783‐793. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, Lipson S, Guralnik JM. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289(18):2387‐2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cagle JG, Bunting M, Kelemen A, Lee J, Terry D, Harris R. Psychosocial needs and interventions for heart failure patients and families receiving palliative care support: a systematic review. Heart Fail Rev. 2017;22(5):565‐580. doi: 10.1007/s10741-017-9596-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Garland EL, Bruce A, Stajduhar K. Exposing barriers to end‐of‐life communication in heart failure: an integrative review. Can J Cardiovasc Nurs J Can En Soins Infirm Cardio‐Vasc. 2013;23(1):12‐18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Committee on Approaching Death : Addressing Key End of Life Issues, Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. National Academies Press (US); 2015. Accessed March 21, 2022. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285681/ [PubMed]