Abstract

Preclinical research has sought to understand the role of the orexin system in cocaine addiction given the connection between orexin producing cells in the lateral hypothalamus and brain limbic areas. Exogenous administration of orexin peptides increased cocaine self-administration whereas selective orexin-1 receptor antagonists reduced cocaine self-administration in non-human animals. The first clinically available orexin antagonist, suvorexant (a dual orexin-1 and orexin-2 receptor antagonist), attenuated motivation for cocaine and cocaine conditioned place preference, as well as cocaine-associated impulsive responding, in rodents. This study aimed to translate those preclinical findings and determine whether suvorexant maintenance altered the pharmacodynamic effects of cocaine in humans. Seven non-treatment seeking subjects with cocaine use disorder completed this within-subject human laboratory study, and a partial data set was obtained from one additional subject. Subjects were maintained for at least three days on 0, 5, 10 and 20 mg oral suvorexant administered at 2230 h daily in random order. Subjects completed experimental sessions in which cocaine self-administration of 0, 10 and 30 mg/70 kg of intravenous cocaine was evaluated on a concurrent progressive ratio drug versus money choice task. Subjective and physiological effects of cocaine were also determined. Cocaine functioned as a reinforcer and produced prototypic dose-related subjective and physiological effects (e.g., increased ratings of “Stimulated” and heart rate). Suvorexant (10, 20 mg) increased self-administration of 10 mg/70 kg cocaine and decreased oral temperature but did not significantly alter any other effects of cocaine. Future research may seek to evaluate the effects of orexin-1 selective antagonists in combination with cocaine.

Keywords: Humans, Self-Administration, Orexin, Cocaine, Suvorexant

1. Introduction

Orexin, also known as hypocretin, neuropeptides are produced by cells located almost exclusively in the lateral hypothalamus, but this system sends projections throughout the brain including the locus coeruleus, the forebrain, hindbrain and the posterior hypothalamus (see Barson and Leibowitz, 2017 for a review). Two different orexin receptors have been identified, orexin-1 (Ox1) and orexin-2 (Ox2) (Barson and Leibowitz, 2017; Boss and Roch, 2015). Two endogenous orexin neuropeptides have also been identified, orexin-A, which activates both Ox1 and Ox2 receptors, and orexin-B, which is more selective for Ox2 receptors (Matsuki and Sakurai, 2008). Given its location in the brain and its centrality to networks (e.g., the limbic system) that regulate motivation and reward, the orexin system has been recognized for its ability to control sleep, waking, homeostatic food intake and other adaptive behaviors (Barson and Leibowitz, 2017; Boutrel et al., 2013), as well as motivation for drugs and non-homeostatic food intake (Barson and Leibowitz, 2017; Boutrel et al., 2013; Harris et al., 2005; Hoyer and Jacobson, 2013). This effect is largely driven by extrahypothalamic transmission to limbic brain regions like the nucleus accumbens and ventral tegmental area, where orexin administration increases extracellular dopamine levels (e.g., Korotkova et al., 2003; Patyal et al., 2012).

The orexin system is increasingly being recognized for its role in cocaine-associated behaviors (see Hoyer and Jacobson, 2013; James at al., 2017; 2021; Khoo and Brown, 2014 for reviews). Acute exogenous administration of orexin peptides increases cocaine self-administration and cocaine-induced dopamine signaling in preclinical models (España et al., 2011; Foltin and Evans, 2018). Opposite effects have been observed following antagonism of the orexin system. Such antagonism has been achieved primarily by genetic manipulation or by acute pharmacological pretreatment with orexin specific antagonists (see Barson and Leibowitz, 2017 and James et al., 2017 for reviews). Numerous preclinical studies have demonstrated genetic knockout/knockdown of orexin function reduces effortful responding maintained by cocaine doses (e.g., on a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement), cocaine-seeking behavior and cocaine-induced dopamine signaling, relative to controls (Bernstein et al., 2018; Schmeichel et al., 2018; Shaw et al., 2017; Steiner et al., 2018).

Pharmacological antagonism of orexin receptors also attenuates motivation for cocaine, escalation of cocaine intake, response to cocaine cues and reinstatement of cocaine seeking behavior relative to vehicle in preclinical models (Bentzley et al., 2015; Borgland et al., 2009; Brodnik et al., 2015; Foltin and Evans, 2018; Gentile et al., 2018a; 2018b; Hollander et al., 2012; Levy et al., 2017; Martin-Fardon and Weiss, 2014; Pantazis et al., 2022; Prince et al., 2015; Schmeichel et al., 2017; Steiner et al., 2013). Several of these studies have shown administration of SB334867, a selective Ox1 antagonist, attenuates cocaine self-administration under high work requirements (e.g., under fixed ratio 5 or progressive ratio schedules of reinforcement) relative to vehicle (e.g., Borgland et al., 2009; Brodnik et al., 2015; Hollander et al., 2012; Prince et al., 2015). These findings with rodents were translated to non-human primates in a study showed administration of SB334867 reduced cocaine taking under several schedules of reinforcement, including a progressive ratio schedule, and blocked reinstatement of extinguished cocaine responding in female rhesus monkeys (Foltin and Evans, 2018).

Preclinical studies have demonstrated dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs) also effectively attenuate abuse-related effects of cocaine, suggesting both Ox1 and Ox2 receptors may contribute to cocaine-associated maladaptive behaviors (Gentile et al., 2018a; 2018b; Steiner et al., 2013). In the earliest study, the DORA almorexant blocked expression of cocaine conditioned place preference (Steiner et al., 2013). Two subsequent studies evaluated how another DORA, suvorexant (Belsomra®; Norman and Anderson, 2016), altered the reinforcing effects of cocaine, as well as other cocaine-associated behaviors (Gentile et al., 2018a; 2018b). In the first study, suvorexant administration dose-dependently attenuated motivation for ≈0.36 mg/kg/injection cocaine on a progressive ratio schedule. Suvorexant also reduced cocaine conditioned place preference and limited cocaine-induced elevations in striatal dopamine levels by up to 20% relative to vehicle in rats (Gentile et al., 2018a). Suvorexant did not alter cocaine-induced locomotor activity in that study, indicating reductions in responding were not due to somnolence.

The extant preclinical data support the premise that the orexin system plays a key role in the effects of cocaine in rodents and monkeys. These preclinical findings suggest orexin system antagonism selectively reduces cocaine taking (i.e., it does not disrupt sleep/waking or regular food intake) and ameliorates other maladaptive cocaine-associated behaviors. To our knowledge, no published studies have evaluated the role of the orexin system, including orexin antagonism, in the pharmacodynamic effects of cocaine in humans. The purpose of this experiment was to translate preclinical research into humans and determine how maintenance on placebo and suvorexant (5, 10 and 20 mg/day) influenced self-administration of intravenous cocaine (0, 10 and 30 mg/70 kg) using a sophisticated human laboratory design. Subjective, performance and physiological effects of cocaine were also evaluated as a function of suvorexant maintenance. We hypothesized suvorexant would attenuate motivation for cocaine on a concurrent progressive ratio drug versus money choice task, as well as other abuse-related effects of cocaine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

To be eligible for the study, subjects had to be healthy and without contraindications to cocaine and suvorexant. Subjects also had to report recent use of smoked or intravenous cocaine, meet diagnostic criteria for cocaine use disorder according to a computerized Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID) that was reviewed by a psychiatrist and provide a benzoylecgonine positive urine sample during screening to verify current cocaine use status. Screening procedures for all subjects included a medical history questionnaire, laboratory tests (i.e., blood chemistry screen, complete blood count and urinalysis), electrocardiogram and a brief psychiatric examination. Subjects were excluded from participation if a study physician deemed the screening results to be abnormal. Subjects were excluded if they had histories of serious physical disease (e.g., persistent hypertension, myocardial infarction, seizures), current physical disease or current or past histories of serious psychiatric disorder/substance use disorder (e.g., physiologic dependence on opioids, alcohol or benzodiazepines; schizophrenia; major depression; bipolar disorder), that in the opinion of a study physician would have interfered with study participation. Female subjects had to be using an effective form of birth control (e.g., birth control pills, IUD, condoms or abstinence) in order to participate.

A total of seven subjects (3 women; 2 White, 4 Black, 1 Multiethnic [White and Latinx]) provided sober, written informed consent to participate and completed this within-subject, placebo-controlled, inpatient study. An additional subject (a Black woman) provided a partial data set before needing to be discharged from the study at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Six additional subjects signed consent to enroll in the study. Of these, 4 were not admitted to the inpatient unit and 2 were admitted to the inpatient unit but left before completing the study. For these 2 admitted subjects, one was discontinued due to an inability to insert a venous catheter for dosing and the other exceeded safety parameters during the medical safety session so they had no usable data for the present analysis. Subjects weighed 74 ± 14 kg on average (± SD), had BMIs of 25 ± 4, were 45 ± 5 years of age at screening and had 12 ± 3 years of education. Drug Abuse Screening Test (Skinner, 1982) scores were 10 ± 5. Subjects reported using cocaine 19 ± 8 days in the month prior to screening. Subjects also reported experience with other drugs. Seven subjects were daily cigarette smokers (10 ± 8 cigarettes/day). Four subjects reported weekly alcohol use (21 ± 15 standard drinks/week). In the month prior to screening, subjects reported cannabis use (n=5) and opioid use (n=1). Aside from meeting criteria for cocaine use disorder, some subjects also met criteria for alcohol use disorder (n=3; not physiologically dependent) and cannabis use disorder (n=2). All subjects were paid for their participation. The Medical Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky approved this study, which was conducted in accordance with all relevant guidelines, including the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. General Procedures

Subjects were enrolled as inpatients at the University of Kentucky Chandler Medical Center Inpatient Clinical Research Unit (CRU) for approximately one month and completed one drug-free practice, one medical safety and twelve experimental sessions. During inpatient admission, subjects received standard caffeine-free hospital meals. Urine samples were collected daily and expired breath samples were collected prior to each session to confirm drug and alcohol abstinence, respectively. Pregnancy tests were conducted daily on urine samples from the female subjects. All pregnancy tests were negative throughout their participation. When not in session, subjects could smoke cigarettes ad libitum if CRU staff was available to escort them to the designated smoking area.

During the medical safety session, subjects received each of the doses of intravenous cocaine to be tested in subsequent experimental sessions (i.e., 1 infusion of 0, 10 and 30 mg/70kg cocaine) in ascending order, separated by 60-min. If predetermined cardiovascular parameters (see Lile et al., 2020) were exceeded during this session, the subject would have been discharged from the study, but only one subject was excluded as noted above.

2.2.1. Drug Maintenance Days.

Drug maintenance began on the day immediately after the medical safety session and continued throughout the protocol. Placebo or suvorexant was administered orally at 2230 h. Subjects were maintained on placebo or suvorexant (5, 10 and 20 mg/day) in random order. After at least three days of maintenance on the first assigned condition, subjects completed a block of three experimental sessions, described below. Maintenance on the assigned condition continued across experimental session days. Upon completion of these three experimental sessions, subjects underwent a drug washout period for three nights (i.e., placebo capsules were administered at 2230h). Subjects then began maintenance on the next assigned condition, which also lasted at least three days before the second block of three experimental sessions was completed. This pattern continued twice more and after completing all twelve experimental sessions, subjects were discharged from the study.

2.2.2. Experimental Sessions.

Subjects who smoked cigarettes were allowed to smoke a cigarette between approximately 0730 and 0800 h prior to starting experimental sessions at 0900 h and were not allowed to smoke again until the session ended approximately 6.5 h later. Sessions consisted of a Sampling Phase and a Self-Administration Phase, which were separated by an approximately three-hour break in which lunch was available.

2.2.2.1. Sampling Phase.

Subjects completed a sampling phase in each experimental session to acquaint them with the effects of the cocaine dose available during that session. Baseline subjective and physiological measures were completed at approximately 0900 h. At approximately 1000 h, the intravenous cocaine dose (0, 10 or 30 mg/70 kg) available during that session was administered. Cocaine dosing order was random for each subject and suvorexant dosing condition. Immediately after dosing and at 15-minute intervals for the next 60 minutes, subjective measures were completed. Physiological measures were collected at 2-minute intervals after dosing. Commodity Purchase Tasks and a Cognitive Battery were completed 15 minutes after administration of the sampling dose. The sampling phase ended at approximately 1030 h.

2.2.2.2. Self-Administration Phase.

The self-administration phase began at approximately 1330 h. During this phase, subjects were given 10 opportunities to choose between 1/10th of the cocaine dose administered during the sampling phase and USD $0.50 on a progressive ratio task (see below). At each of the 10 opportunities, subjects were forced to make a choice for either 1/10th of the cocaine dose or money (i.e., the sum of cocaine and money choices in each session was always 10). The earned cocaine dose was administered at approximately 1430 h (e.g., if a subject made 5 choices for drug, 50% of the sampled dose was administered at 1430 h rather than 10% of the sampled dose after the completion of each ratio) and subjects then completed subjective measures and physiological measures (including temperature) at 15-minute intervals for 60 minutes. Session ended at approximately 1530 h.

2.3. Experimental Session Measures

The reinforcing effects of intravenous cocaine were assessed using a progressive ratio task. Subjects were able to earn drug doses or money by responding on a computer mouse according to a progressive ratio schedule. Cocaine and money were available on concurrent, independent progressive ratio schedules as described previously (Stoops et al., 2012). The initial ratio to obtain a reinforcer was 400 clicks. The response requirement for each subsequent choice of that specific reinforcer increased by 100 (i.e., 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000, 1100, 1200, 1300 responses if a subject responded exclusively for cocaine or money). The dependent measures for this task were number of drug choices, out of a maximum of 10 (or 100% of the sampling dose), and breakpoint, out of a maximum of 1300 responses.

Subjective measures were an Adjective Rating Scale (Oliveto et al. 1992), a locally developed Drug-Effect Questionnaire (Rush et al. 2003) and the Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (Dudish-Poulsen and Hatsukami, 1997). Physiological measures (i.e., blood pressure and heart rate) were recorded using a digital monitor. Temperature was measured using a digital oral thermometer.

Subjects completed a battery of cognitive-behavioral tasks 15 minutes after the cocaine sampling dose in each experimental session. These included the:

n-Back, which measured working memory and working memory capacity (Jaeggi et al. 2010). In this task, subjects were presented with a sequence of numbers and asked to indicate when the current stimulus matched the one from “n” steps earlier. Two settings were used in this study, the 1-back and the 2-back (i.e., matching 1 and 2 stimuli back, respectively). The primary outcome of this task was percentage of correct responses.

5-Trial Adjusting Delay Discounting Task, which assessed discounting rates for cocaine and money (Koffarnus and Bickel, 2014). In this task, subjects made a series of 5 choices between an immediately available, smaller reinforcer and a larger reinforcer at various delays. Subjects were told that all choices were hypothetical. The primary outcome of this task was the delay discounting rate (log 10 transformed k).

Visual-Probe Task, which measured attentional bias to cocaine images as an indicator of cocaine cue response (i.e., allocation of attention to cocaine cues) (e.g., Lubman et al. 2000; Townshend and Duka, 2001). The visual-probe task consisted of a total of 80 trials (40 critical trials and 40 filler trials) presented in randomized order. During critical trials of interest, cocaine-related images (n = 10) were presented adjacent to matched, non-cocaine-related, neutral images (n = 10). Immediately after presentation of the images, a visual probe (an “X”) appeared in the same location as one of the images and response time (msec) to the probe was measured. Attentional bias was inferred from differences in response times to probes that replaced cocaine versus neutral images during critical trials. Slower response times to probes that replaced neutral images, relative to when the probe replaced a cocaine-related image, were interpreted as the subject’s attention being focused on the cocaine image. An attentional bias score was calculated from response time (RT) data in the visual-probe task as described previously (i.e., RTCocaine – RTNeutral; Bolin et al., 2017; Marks et al., 2014) such that negative scores would suggest a cocaine-cue attentional bias. The attentional bias score served as the primary outcome measure for data analysis.

Finally, subjects completed hypothetical commodity purchase tasks for chocolate, cigarettes, alcohol and the sampled cocaine dose 15 minutes after administration of the cocaine sampling dose. Results from purchase tasks will be reported elsewhere.

2.4. Measures Completed Outside of Experimental Sessions

Subjects also completed a range of measures outside of experimental sessions. These included:

Weight in kg measured on a digital scale daily.

Sleep using The Saint Mary’s Hospital Sleep Questionnaire (SMHSQ; Ellis et al., 1981), a validated self-report measure of sleep quantity and quality, completed immediately prior to Sessions 1, 4, 7 and 10 (i.e., the first experimental session for each suvorexant maintenance condition). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse et al., 1989) was also included but based on errors in administration, data from this measure were uninterpretable and will not be discussed further.

Side effects measured daily using the Udvalg for Kliniske UndersØgelser (UKU), which is a standardized, validated rating scale that assesses over 50 potential side effects (e.g., sedation, akathisia, weight change) associated with administration of centrally acting drugs (Lingjaerde et al., 1987. It also includes a global assessment of how these side effects interfere with functioning.

2.5. Drug Administration

All drugs were administered in a double-blind fashion. Only study investigators and the Investigational Drug Service staff had access to dose orders to maintain the blind. These individuals did not interact with subjects during experimental sessions, nor did they collect experimental data. Suvorexant doses (5, 10 and 20 mg, Merck, Rahway, NJ) were prepared from commercially available drug in a gelatin capsule backfilled with cornstarch. Placebo capsules contained only cornstarch. The three-day minimum maintenance period on each dose with once daily dosing was selected to reach steady state suvorexant levels based upon published clinical pharmacology data (Lee-Iannotti and Parish, 2016). The highest target dose of 20 mg suvorexant was selected because it is the maximum daily recommended dose (Lee-Iannotti and Parish, 2016).

Cocaine doses (0, 10 and 30 mg/70 kg) were aseptically prepared by dissolving cocaine HCl USP (Medisca, Irving, TX) in 1 mL 0.9% sodium chloride and filtering the solution through 0.22 μm filters into a sterile, pyrogen-free vial. The sampling doses for administration (10 and 30 mg/70 kg) were drawn up into syringes within 24 h of an experimental session. The 0 mg dose contained only 0.9% sodium chloride. A total of 10 potential self-administration doses were also prepared within 24 h of an experimental session (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10 mg/70 kg labeled Dose 1 through 10 for the 10 mg/70 kg sampling condition). Each dose was administered via a catheter in the non-dominant arm over 30 sec.

Doses were not administered if a subject’s heart rate was ≥ 90 bpm, systolic pressure was ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic pressure was ≥ 90 mmHg or if clinically significant and/or prolonged ECG abnormalities were detected. No clinically significant or prolonged ECG abnormalities were detected during any subject’s participation.

2.6. Data Analysis

Progressive ratio task data were analyzed as number of drug choices using a two-factor repeated mixed-effects model, allowing for use of the non-completing subject’s partial data set, with Suvorexant Dose (0, 5, 10 and 20 mg/day) and Cocaine Dose (0, 10 and 30 mg/70 kg) as the factors (Prism 9, GraphPad, San Diego, CA). F values from the Geisser-Greenhouse corrected mixed-effects model were used to determine statistical significance with a threshold of p < 0.05. Subjective and physiological measures were analyzed as peak effect (i.e., the maximum score observed in the 60 minutes following administration of the cocaine sampling dose) in the same fashion as the progressive ratio task data. Cognitive-behavioral task outcomes completed 15 minutes after the sampling dose were also analyzed in the same fashion as the progressive ratio task data.

For weight and the UKU, data from the observation completed immediately before beginning the experimental session block (i.e., the morning before sessions 1, 4, 7 and 10 for weight, the afternoon before sessions 1, 4, 7 and 10 for the UKU) were analyzed using a one-factor mixed-effects analysis with Suvorexant Dose (0, 5, 10 and 20 mg/day) as the factor. Data from the SMHSQ items were analyzed using a one-factor repeated mixed-effects model with Suvorexant Dose (0, 5, 10 and 20 mg/day) as the factor.

3. Results

Table 1 shows F values for outcomes that had effects which reached statistical significance.

Table 1:

Summary Table of F Values (Geisser-Greenhouse corrected degrees of freedom) for measures with a statistically significant effect.

| Measure | Suvorexant Dose Main Effect F Value | Cocaine Dose Main Effect F Value | Suvorexant and Cocaine Dose Interaction Effect F Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Drug Choices | 4.12 (2.22, 15.56) * | 16.76 (1.75, 12.22) *** | 2.28 (1.42, 8.29) |

| Breakpoint | 4.21 (2.40, 16.77) * | 18.32 (1.80, 12.58) *** | 2.14 (1.44, 8.42) |

| Adjective Rating Scale (Stimulant) | 0.39 (1.93, 13.52) | 21.15 (1.26, 8.83) *** | 1.422 (1.62, 9.47) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Active/Alert/Energetic) | 2.18 (1.03, 7.20) | 6.82 (1.08, 7.55) * | 1.06 (1.12, 6.54) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Irregular/Racing Heartbeat) | 2.54 (1.43, 9.98) | 13.91 (1.07, 7.51) ** | 2.22 (1.56, 9.10) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Like Drug) | 2.59 (1.25, 8.72) | 6.01 (1.13, 7.89) * | 1.945 (1.28, 7.44) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Performance Improved) | 0.89 (1.54, 10.74) | 4.06 (1.72, 12.06) * | 2.11 (1.43, 8.35) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Rush) | 0.31 (1.45, 10.16) | 18.21 (1.10, 7.67) ** | 1.382 (1.89, 11.01) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Stimulated) | 0.86 (2.09, 14.60) | 10.01 (1.02, 7.14) * | 1.44 (1.15, 6.69) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Talkative/Friendly) | 0.90 (1.42, 9.93) | 6.26 (1.06, 7.39) * | 0.87 (1.31, 7.64) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Willing to Pay For) | 0.55 (1.49, 10.42) | 15.76 (1.55, 10.86) ** | 1.70 (1.39, 8.12) |

| Drug Effect Questionnaire (Willing to Take Again) | 1.53 (1.26, 8.79) | 13.95 (1.45, 10.14) ** | 2.33 (1.27, 7.43) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 4.12 (0.93, 6.52) | 19.72 (1.19, 8.31) ** | 0.10 (3.99, 23.25) |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 1.16 (2.35, 16.47) | 10.81 (1.97, 13.81) ** | 0.57 (2.83, 16.98) |

| Heart Rate | 1.27 (1.79, 12.50) | 15.82 (1.63, 11.42) *** | 0.79 (2.08, 12.15) |

| Temperature | 6.41 (2.62, 18.33) ** | 0.16 (1.05, 7.34) | 1.22 (1.71, 9.99) |

Bolded values are statistically significant.

denotes p < 0.05,

denotes p < 0.01,

denotes p < 0.001.

F values without any asterisks are not statistically significant.

3.1. Progressive Ratio Task

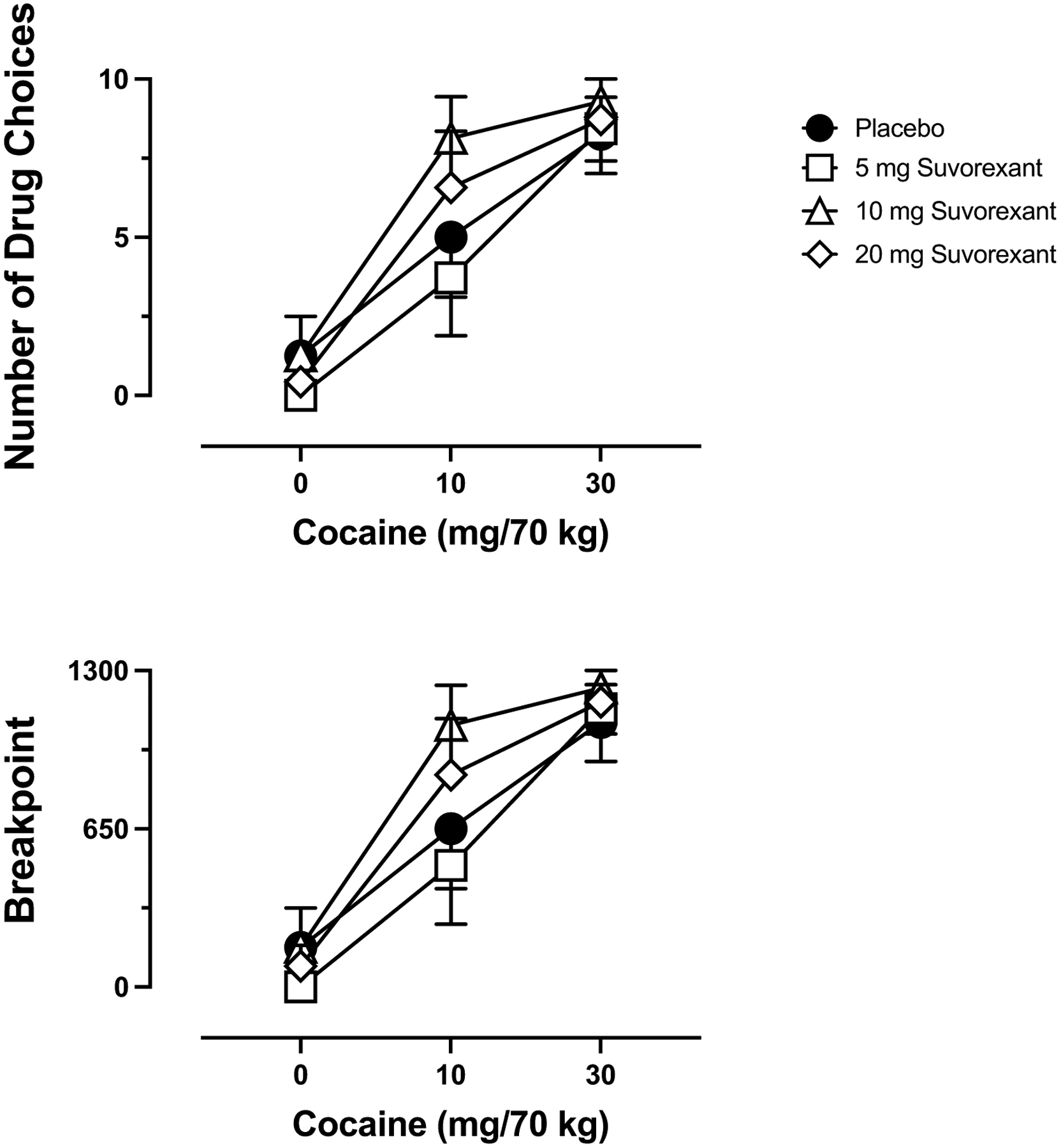

Significant main effects of Suvorexant Dose and Cocaine Dose were observed for Number of Drug Choices and Breakpoint on the Progressive Ratio Task. There was no interaction of Suvorexant Dose and Cocaine Dose on this outcome. As shown in Figure 1, cocaine produced dose-related increases in Number of Drug Choices and Breakpoint with near maximal intake/responding observed at the 30 mg/70 kg dose regardless of suvorexant dose. Relative to 0 mg suvorexant, the low suvorexant dose (5 mg) reduced 10 mg/70 kg cocaine choice/responding by approximately 25% whereas the two highest suvorexant doses (10 and 20 mg) increased choice/responding of/for that dose by approximately 60% and 30%, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Dose-response function for cocaine following maintenance on placebo (circles), 5 mg suvorexant (squares), 10 mg suvorexant (triangles) and 20 mg suvorexant (diamonds) for Number of Drug Choices out of 10 maximum (top panel) and break point (bottom panel) on the Progressive Ratio Task. X-axis: Intravenous cocaine dose in mg/70 kg. Brackets indicate 1 S.E.M.

3.2. Subjective Measures

Significant main effects of Cocaine Dose were observed for the Stimulant Subscale of the Adjective Rating Scale and nine items from the Drug-Effect Questionnaire (Active/Alert/Energetic; Irregular/Racing Heartbeat; Like Drug; Performance Improved; Rush; Stimulated; Talkative/Friendly; Willing to Pay For; Willing to Take Again). There were no other significant main effects of Cocaine Dose, nor were there any significant effects of Suvorexant Dose or interactions of Suvorexant Dose and Cocaine Dose on the subjective measures. Figure 2 shows representative data for Like Drug and Stimulated, indicating that active cocaine doses produced dose-related increases on these subjective measures, regardless of suvorexant maintenance condition.

Fig. 2.

Peak effect dose-response functions for cocaine following maintenance on placebo (circles), 5 mg suvorexant (squares), 10 mg suvorexant (triangles) and 20 mg suvorexant (diamonds) for subjective ratings of Like Drug (left graph) and Stimulated (right graph) out of 100 maximum. X-axis: Intravenous cocaine dose in mg/70 kg. Brackets indicate 1 S.E.M.

3.3. Cognitive-Behavioral Tasks

There was no effect of Suvorexant Dose or Cocaine Dose, nor was there an interaction of Suvorexant Dose and Cocaine Dose, on any of the Cognitive-Behavioral Tasks.

3.4. Physiological Measures

A significant main effect of Cocaine Dose was observed for Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure, as well as Heart Rate. As shown Heart Rate in Figure 3, cocaine produced dose-related increases regardless of suvorexant condition. A significant main effect of Suvorexant Dose was observed for Temperature. As shown in Figure 3, the two higher suvorexant doses decreased oral temperature across all cocaine dose conditions. There were no other statistically significant effects observed for any physiological measures.

Fig. 3.

Peak effect dose-response functions for cocaine following maintenance on placebo (circles), 5 mg suvorexant (squares), 10 mg suvorexant (triangles) and 20 mg suvorexant (diamonds) for Heart Rate (top graph) and Temperature (bottom graph). X-axis: Intravenous cocaine dose in mg/70 kg. Brackets indicate 1 S.E.M.

3.5. Measures Completed Outside of Experimental Sessions

There was no effect of Suvorexant Dose on weight, items from the SMHSQ or items from the UKU.

4. Discussion

This study found that 1) intravenous cocaine produced prototypic reinforcing, subjective and physiological effects and 2) maintenance on higher suvorexant doses, including the highest clinically recommended daily dose, enhanced the reinforcing effects of low-dose cocaine. Because cocaine was available on a concurrent progressive ratio drug versus money choice schedule, and progressive ratio schedules are often considered measures of motivation (Arnold and Roberts, 1997; Hodos, 1961; Katz, 1990; Richardson and Roberts, 1996; Stafford et al., 1998), this result suggests that suvorexant maintenance increased motivation to choose cocaine over money in humans. It is important to note suvorexant maintenance may also have enhanced motivation for high dose cocaine, but given maximal intake observed at that dose (i.e., a ceiling effect), such an effect cannot be determined from these data. Beyond these main findings, which will be discussed further below, suvorexant-cocaine dose combinations were safe and tolerable and suvorexant maintenance did not change other subjective, cognitive-behavioral or physiological effects of cocaine. A decrease in temperature was observed, likely due to antagonism of orexin’s vasoconstrictive effects (e.g., Meusel et al., 2022), indicating suvorexant was physiologically active during experimental sessions.

Cocaine functioned as a robust reinforcer with near maximal drug intake observed at the highest dose tested, regardless of suvorexant maintenance condition. This finding is consistent with the body of human laboratory research examining the reinforcing effects of cocaine which has found that cocaine maintains high degrees of self-administration in humans that is often difficult to disrupt with pharmacological pretreatment or maintenance (for a review, see Regnier et al., 2022). Further, as has been shown in numerous other human laboratory studies, intravenous cocaine produced positive and stimulant-like subjective effects and increased cardiovascular output (e.g., Foltin et al., 1995; Lile et al., 2016; 2020; Walsh et al., 2010).

Suvorexant maintenance did not change any of the effects of cocaine, beyond its reinforcing effects, nor did cocaine or suvorexant impact cognitive-behavioral outcomes. These results are not necessarily unexpected because the abuse related effects of cocaine are difficult to alter using a pharmacological agent alone in humans (e.g., Foltin et al. 2015). Furthermore, the effects of cocaine on cognitive-behavioral performance can be subtle and variable (Strzelecki et al., 2022). Moreover, the impairing effects of suvorexant on cognition appear to be most pronounced within 4–5 h of administration (e.g., Landry et al., 2022), but experimental sessions in this study started approximately 10.5 h after the last suvorexant dose. Our findings do not align with those of Suchting and colleagues (2020) who showed suvorexant ameliorated cognitive performance deficits in individuals with cocaine disorder. Importantly, however, the individuals in our study completed the cognitive-behavioral battery after cocaine dosing whereas Suchting and colleagues conducted sessions when subjects were abstinent form cocaine.

Suchting and colleagues also found that suvorexant maintenance ameliorated heart rate and salivary cortisol response following cold-pressor challenge. Suvorexant also improved sleep outcomes. The present study did not assess stress response but our lack of statistically significant findings regarding sleep outcomes (considered in more detail below) are discordant with that prior report (Suchting et al., 2020). The reason for this difference may be attributable to different methodologies (i.e., sleep actigraphy in Suchting et al., 2020, self-report in the present study), cocaine use status (i.e., abstinence in Suchting et al, 2020, active use in the present study) or lack of statistical power in the present study (also considered in more detail below).

The finding that suvorexant maintenance increased self-administration of 10 mg/70 kg cocaine is discordant with prior preclinical literature showing orexin antagonism attenuates the reinforcing and other abuse-related effects of cocaine (Bentzley et al., 2015; Borgland et al., 2009; Brodnik et al., 2015; Foltin and Evans, 2018; Gentile et al., 2018a; 2018b; Hollander et al., 2012; Levy et al., 2017; Martin-Fardon and Weiss, 2014; Pantazis et al., 2022; Prince et al., 2015; Schmeichel et al., 2017; Steiner et al., 2013). Although the reasons for this discrepancy are not known, several likely possibilities include dosing regimen, dosing timing and species differences. In prior rodent and monkey research, the orexin antagonist under study was typically administered acutely and shortly before experimental sessions during which cocaine was available (e.g., Foltin and Evans, 2018; Gentile et al., 2018a; Schmeichel et al., 2017). As such, the reductions in cocaine self-administration observed in those studies could especially be due the timing of dosing and acute and immediate, rather than chronic, antagonism of the orexin system. Chronic treatment may produce different effects, as shown in this study. Consistent with this, repeated treatment with the Ox1 antagonist SB334867 did not affect ongoing cocaine self-administration in an early rodent study (Zhou et al., 2012). Future research will need to be conducted that more closely aligns preclinical and clinical self-administration and pharmacological pretreatment methods to better determine whether species differences contributed to the divergent outcomes.

Negative reinforcement processes could also explain the findings observed with the self-administration of 10 mg/70 kg intravenous cocaine dose such that subjects were attempting to ameliorate undesired effects of suvorexant by taking more cocaine. This explanation is unlikely, however, when considering that 1) suvorexant did not produce any significant side effects as measured on the UKU, 2) suvorexant did not impact daytime sleep or reports of feeling clear headed as measured on the SMHSQ, 3) suvorexant did not produce any decrements in performance on the cognitive-behavioral battery and 4) suvorexant did not produce any negative effects on the subjective measures.

Recruitment and enrollment for this project was severely limited by the COVID-19 pandemic during which our laboratory was shut down for over 6 months, leading to the primary limitation of this experiment: a relatively small sample size. Although the sample size is comparable to that of earlier human laboratory research with cocaine (e.g., Donny et al., 2003; Haney et al., 2011; Rush et al., 2010; Stoops et al., 2012; Walsh et al., 2010), it is notably smaller than that of more recent human laboratory research with cocaine (e.g., Lile et al., 2020; Rush et al., 2021; Stoops et al., 2019). Despite the sample size, significant effects of suvorexant were still observed on cocaine self-administration, supporting the robustness of this outcome.

The small sample size also likely contributed to a lack of power to detect a statistically significant effect of suvorexant maintenance on sleep as assessed by the SMHSQ. Visual inspection of the data from the SMHSQ revealed no effect (i.e., a flat dose effect curve) on nearly all measures, although self-reported number minutes of sleep last night increased, on average, from approximately 360 minutes during placebo maintenance to approximately 400 minutes during 20 mg suvorexant maintenance (note: no appreciable differences were observed on this outcome for 5 and 10 mg suvorexant maintenance). Although this effect was not statistically significant, expert recommendations indicate that a 30-minute increase in self-reported sleep is clinically significant (Sateia et al., 2017), suggesting that suvorexant maintenance may have clinical utility for promoting sleep in individuals with cocaine use disorder. The clinically significant change in self-reported sleep produced by 20 mg suvorexant was not accompanied by changes in subjective or physiological response to cocaine but was associated with a 30% increase in self-administration of 10 mg/kg intravenous cocaine, suggesting any sleep promoting effects of suvorexant in individuals with cocaine use disorder might be offset by increased cocaine intake.

5. Conclusions

Despite great strides in our understanding of the neurobiological underpinnings of the effects of cocaine from preclinical models (see Howell and Cunningham, 2015; Kalivas, 2007; Pierce et al., 2018 for reviews), very little research has advanced these findings into humans, which is likely due to a lack of clinically available pharmacologically selective agents (Czoty et al., 2016; Galaj et al., 2018; Regnier et al., 2022). Without a thorough understanding of how preclinical findings relate to clinical conditions, the field will struggle to identify neurobiological circuits that contribute to the problems posed by cocaine use disorder and to guide treatment based on those clinical neuroscience findings (Czoty et al., 2016). This project sought to translate the promising preclinical findings regarding the role of orexin in the reinforcing and abuse-related effects of cocaine into humans. Although our findings were inconsistent with prior rodent and monkey research, the outcomes point to an overall need to more closely align preclinical and clinical methods to better understand the translational value and increase the utility of these approaches (Deroche-Gamonet, 2020; Field and Kersbegen, 2020; Muller, 2020; Perry and Lawrence, 2020). Specifically, future work should determine the influence of acute and chronic treatment with orexin antagonists, particularly selective Ox1 antagonists (see Khoo and Brown, 2014), on the abuse-related effects of cocaine in homologous non-human animal and human laboratory models.

Highlights.

This human laboratory study tested how orexin antagonism influenced cocaine effects

Orexin antagonism increased cocaine self-administration and decreased temperature

Orexin antagonism did not alter any other effects of cocaine

Acknowledgments:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of the University of Kentucky Laboratory of Human Behavioral Pharmacology for technical assistance, the staff of the University of Kentucky Center for Clinical and Translational Science Clinical Research Unit for medical assistance and the University of Kentucky Investigative Drug Service and Pasadena Pharmacy for preparation of study medications. This study complied with all laws of the United States of America.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest. The authors gratefully acknowledge research support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA048617) and from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001998) of the National Institutes of Health. These funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection or analysis, or preparation and submission of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

References

- Arnold JM, Roberts DC (1997). A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 57, 441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barson JR, Leibowitz SF (2017). Orexin/hypocretin system: Role in food and drug overconsumption. Int Rev Neurobiol, 136, 199–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Aston-Jones G (2015). Orexin-1 receptor signaling increases motivation for cocaine-associated cues. Eur J Neurosci, 41(9), 1149–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DL, Badve PS, Barson JR, Bass CE, España RA (2018). Hypocretin receptor 1 knockdown in the ventral tegmental area attenuates mesolimbic dopamine signaling and reduces motivation for cocaine. Addict Biol, 23, 1032–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin BL, Alcorn III JL, Lile JA, Rush CR, Rayapati AO, Hays LR, Stoops WW (2017). n-Acetylcysteine reduces cocaine cue attentional bias and differentially alters cocaine self-administration based on dosing order. Drug Alcohol Depend, 178, 452–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL, Chang SJ, Bowers MS, Thompson JL, Vittoz N, Floresco SB, Chou J, Chen BT, Bonci A (2009). Orexin A/hypocretin-1 selectively promotes motivation for positive reinforcers. J Neurosci, 29(36), 11215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss C, Roch C (2015). Recent trends in orexin research--2010 to 2015. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 25(15), 2875–2887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutrel B, Steiner N, Halfon O (2013). The hypocretins and the reward function: What have we learned so far? Front Behav Neurosci, 7, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodnik ZD, Bernstein DL, Prince CD, España RA (2015). Hypocretin receptor 1 blockade preferentially reduces high effort responding for cocaine without promoting sleep. Behav Brain Res, 291, 377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res, 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czoty PW, Stoops WW, Rush CR (2016). Evaluation of the “pipeline” for development of medications for cocaine use disorder: A review of translational preclinical, human laboratory, and clinical trial research. Pharmacol Rev, 68, 533–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroshe-Gamonet V (2020). The relevance of animal models of addiction. Addiction, 115, 16–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donny EC, Bigelow GE, Walsh SL (2003). Choosing to take cocaine in the human laboratory: Effects of cocaine dose, inter-choice interval and magnitude of alternative reinforcement. Drug Alcohol Depend, 69, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudish-Poulsen SA, Hatsukami DK (1997). Dissociation between subjective and behavioral responses after cocaine stimuli presentations. Drug Alcohol Depend, 47(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BW, Johns MW, Lancaster R, Raptopoulos P, Angelopoulos N, Priest RG (1981). The St. Mary’s Hospital sleep questionnaire: A study of reliability. Sleep, 4(1), 93–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- España RA, Melchior JR, Roberts DC, Jones SR (2011). Hypocretin 1/orexin A in the ventral tegmental area enhances dopamine responses to cocaine and promotes cocaine self-administration. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 214(2), 415–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Kersbergen I (2020). Are animal models of addiction useful? Addiction, 115, 6–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW, Levin FR (1995). Cardiovascular effects of cocaine in humans: Laboratory studies. Drug Alcohol Depend, 37, 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Evans SM (2018). Hypocretin/orexin antagonists decrease cocaine self-administration by female rhesus monkeys. Drug Alcohol Depend, 188, 318–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Haney M, Rubin E, Reed SC, Vadhan N, Balter R, Evans SM (2015). Development of translational preclinical models in substance abuse: Effects of cocaine administration on cocaine choice in humans and non-human primates. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 134, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaj E, Ewing S, Ranaldi R (2018). Dopamine D1 and D3 receptor polypharmacology as a potential treatment approach for substance use disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 89, 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile TA, Simmons SJ, Barker DJ, Shaw JK, España RA, Muschamp JW (2018a). Suvorexant, an orexin/hypocretin receptor antagonist, attenuates motivational and hedonic properties of cocaine. Addict Biol, 23(1), 247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentile TA, Simmons SJ, Watson MN, Connelly KL, Brailoiu E, Zhang Y, Muschamp JW (2018b). Effects of suvorexant, a dual orexin/hypocretin receptor antagonist, on impulsive behavior associated with cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43(5), 1001–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Rubin E, Foltin RW (2011). Aripioprazole maintenance increases smoked cocaine self-administration in humans. Psychopharmacology, 216, 379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris GC, Wimmer M, Aston-Jones G (2005). A role for lateral hypothalamic orexin neurons in reward seeking. Nature, 437, 556–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodos W (1961). Progressive ratio as a measure of reward strength. Science, 134, 943–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander JA, Pham D, Fowler CD, Kenny PJ (2012). Hypocretin-1 receptors regulate the reinforcing and reward-enhancing effects of cocaine: Pharmacological and behavioral genetics evidence. Front Behav Neurosci, 6, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LL, Cunningham KA (2015). Serotonin 5-HT2 receptor interactions with dopamine function: Implications for therapeutics in cocaine use disorder. Pharmacol Rev, 67(1), 176–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer D, Jacobson LH (2013). Orexin in sleep, addiction and more: Is the perfect insomnia drug at hand? Neuropeptides, 47(6), 477–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Perrig WJ, Meier B (2010). The concurrent validity of the N-back task as a working memory measure. Memory, 18, 394–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Fragale JE, O’Connor SL, Zimmer BA, Aston-Jones G (2021). The orexin (hypocretin) neuropeptide system is a target for novel therapeutics to treat cocaine use disorder with alcohol coabuse. Neuropharmacology, 183, 108359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MH, Mahler SV, Moorman DE, Aston-Jones G (2017). A decade of orexin/hypocretin and addiction: Where are we now? Curr Top Behav Neurosci, 33, 247–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW (2007). Neurobiology of addiction: Implications for new pharmacotherapy. Am J Addict, 16, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL (1990). Models of relative reinforcing efficacy of drugs and their predictive utility. Behav Pharmacol, 1, 283–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoo SY, Brown RM (2014). Orexin/hypocretin based pharmacotherapies for the treatment of addiction: DORA or SORA? CNS Drugs, 28(8), 713–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK (2014). A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: Accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 22, 222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkova TM, Sergeeva OA, Eriksson KS, Haas HL, Brown RE (2003). Excitation of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons by orexins/hypocretins. J Neurosci, 23, 7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landry I, Hall N, Alur J, Filippov G, Reyderman L, Setnik B, Henningfield J, Moline M (2022). Cognitive effects of the dual orexin receptor antagonist Lemborexant compared with suvorexant and zolpidem in recreational sedative users. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 42, 374–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Iannotti JK, Parish JM (2016). Suvorexant: A promising, novel treatment for insomnia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat, 12, 491–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy KA, Brodnik ZD, Shaw JK, Perrey DA, Zhang Y, España RA (2017). Hypocretin receptor 1 blockade produces bimodal modulation of cocaine-associated mesolimbic dopamine signaling. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 234(18), 2761–2776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Johnson AR, Banks ML, Hatton KW, Hays LR, Nicholson KL, Poklis JL, Rayapati AO, Rush CR, Stoops WW, Negus SS (2020). Pharmacological validation of a translational model of cocaine use disorder: Effects of d-amphetamine maintenance on choice between intravenous cocaine and a nondrug alternative in humans and rhesus monkeys. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 28, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lile JA, Stoops WW, Rush CR, Negus SS, Glaser PE, Hatton KW, Hays LR (2016). Development of a translational model to screen medications for cocaine use disorder II: Choice between intravenous cocaine and money in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend, 165, 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingjaerde O, Ahlfors U, Bech P, Dencker S, Elgen K (1987). The UKU side effect rating scale: A new comprehensive rating scale for psychotropic drugs and a cross-sectional study of side effects in neuroleptic-treated patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl, 334, 1–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubman DI, Peters LA, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Deakin JF (2000). Attentional bias for drug cues in opiate dependence. Psychol Med, 30(1), 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks KR, Roberts W, Stoops WW, Pike E, Fillmore MT, Rush CR (2014). Fixation time is a sensitive measure of cocaine cue attentional bias. Addiction, 109(9), 1501–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fardon R, Weiss F (2014). Blockade of hypocretin receptor-1 preferentially prevents cocaine seeking: Comparison with natural reward seeking. Neuroreport, 25(7), 485–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuki T, Sakurai T (2008). Orexins and orexin receptors: From molecules to integrative physiology. Results Probl Cell Differ, 46, 27–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meusel M, Vos J, Krapalis A, Machleidt F, Vonthein R, Hallschmid M, Sayk F (2022). Intranasal orexin A modulates sympathetic vascular tone: A pilot study in healthy male humas J Neurophysiol, 137, 548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller CP (2020). Lasting translation: How to improve animal models for addiction treatment. Addiction, 115, 13–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman JL, Anderson SL (2016). Novel class of medications, orexin receptor antagonists, in the treatment of insomnia - critical appraisal of suvorexant. Nat Sci Sleep, 8, 239–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveto AH, Bickel WK, Hughes JR, Shea PJ, Higgins ST, Fenwick JW (1992). Caffeine drug discrimination in humans: Acquisition, specificity and correlation with self-reports. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 261(3), 885–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis CB, James MH, O’Connor S, Shin N, Aston-Jones G (2022). Orexin-1 receptor signaling in ventral tegmental area mediates cue-driven demand for cocaine. Neuropsychopharmacology, 47, 741–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patyal R, Woo EY, Borgland SL (2012). Local hypocretin-1 modulates terminal dopamine concentration in the nucleus accumbens shell. Front Behav Neurosci, 6, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CJ, Lawrence AJ (2020). An imperfect model is still useful. Addiction, 115, 14–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Fant B, Swinford-Jackson SE, Heller EA, Berrettini WH, Wimmer ME (2018). Environmental, genetic and epigenetic contributions to cocaine addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43, 1471–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince CD, Rau AR, Yorgason JT, España RA (2015). Hypocretin/orexin regulation of dopamine signaling and cocaine self-administration is mediated predominantly by hypocretin receptor 1. ACS Chem Neurosci, 6(1), 138–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnier SD, Lile JA, Rush CR, Stoops WW (2022). Clinical neuropharmacology of cocaine reinforcement: A narrative review of human laboratory self-administration studies. J Exp Anal Behav, 117, 420–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson NR, Roberts DC (1996). Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: A method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods, 66, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Hays LR, Glaser PE, Hays LS (2003). Risperidone attenuates the discriminative-stimulus effects of d-amphetamine in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther, 306(1), 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Alcorn JA 3rd, Bolin BL, Reynolds AR, Hays LR, Rayapati AO (2021). Topiramate-phentermine combinations reduce cocaine self-administration in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend, 218, 108413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Sevak RJ, Hays LR (2010). Cocaine choice in humans during d-amphetamine maintenance. J Clin Psychopharmacol, 30, 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL (2017). Clinical practice guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Sleep Med, 13 (2), 307–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeichel BE, Herman MA, Roberto M, Koob GF (2017). Hypocretin neurotransmission within the central amygdala mediates escalated cocaine self-administration and stress-induced reinstatement in rats. Biol Psychiatry, 81(7), 606–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmeichel BE, Matzeu A, Koebel P, Vendruscolo LF, Sidhu H, Shahryari R, Kieffer BL, Koob GF, Martin-Fardon R, Contet C (2018). Knockdown of hypocretin attenuates extended access of cocaine self-administration in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology, 43, 2373–2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw JK, Ferris MJ, Locke JL, Brodnik ZD, Jones SR, España RA (2017). Hypocretin/orexin knock-out mice display disrupted behavioral and dopamine responses to cocaine. Addict Biol, 22(6), 1695–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA (1982) The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 7,363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford D, LeSage MG, Glowa JR (1998). Progressive-ratio schedules of drug delivery in the analysis of drug self-administration: A review. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 139, 169–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner N, Rossetti C, Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, de Lecea L, Magistretti PJ, Halfon O, Boutrel B (2018). Hypocretin/orexin deficiency decreases cocaine abuse liability. Neuropharmacology, 133, 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzelecki A, Weafer J, Stoops WW (2022). Human behavioral pharmacology of stimulant drugs: An update and narrative review. Adv Pharmacol, 93, 77–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE, Hays LR, Rush CR (2012) Influence of acute bupropion pretreatment on the effects of intranasal cocaine. Addiction 107:1140–1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Strickland JC, Alcorn JA 3rd, Hays LR, Rayapati AO, Lile JA, Rush CR (2019). Influence of phendimetrazine maintenance on the reinforcing, subjective, performance and physiological effects of intranasal cocaine. Psychopharmacology, 236, 2569–2577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchting R, Yoon JH, Miguel GGS, Green CE, Weaver MF, Vincent JN, Fries GR, Schmitz JM, Lane SD (2020). Preliminary examination of the orexin system on relapse-related factors in cocaine use disorder. Brain Res, 1731, 146359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Townshend JM, Duka T (2001). Attentional bias associated with alcohol cues: Differences between heavy and occasional social drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 157(1), 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Donny EC, Nuzzo PA, Umbricht A, Bigelow GE (2010). Cocaine abuse versus cocaine dependence: Cocaine self-administration and pharmacodynamic response in the human laboratory. Drug Alcohol Depend, 106(1), 28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Smith RJ, Do PH, Aston-Jones G, See RE (2012). Repeated orexin 1 receptor antagonism effects on cocaine seeking in rats. Neuropharmacology, 63(7), 1201–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]