SUMMARY

The DNA-PKcs kinase mediates the repair of DNA double strand breaks via classical non-homologous end joining (NHEJ). DNA-PKcs is also recruited to active replication forks, although a role for DNA-PKcs in the control of fork dynamics is unclear. Here we identified a crucial role for DNA-PKcs in promoting fork reversal, a process that stabilizes stressed replication forks and protects genome integrity. DNA-PKcs promotes fork reversal and slowing in response to several replication stress-inducing agents in a manner independent of its role in NHEJ. Cells lacking DNA-PKcs activity show increased DNA damage during S-phase and cellular sensitivity to replication stress. Notably, prevention of fork slowing and reversal via DNA-PKcs inhibition efficiently restores chemotherapy sensitivity in BRCA2-deficient mammary tumors with acquired PARPi resistance. Together, our data uncover a new key regulator of fork reversal and show how DNA-PKcs signaling can be manipulated to alter fork dynamics and drug resistance in cancer.

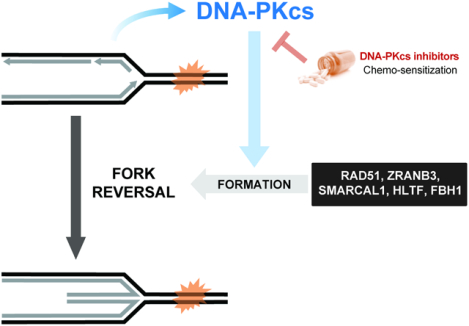

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

Dibitetto et al. find that DNA-PKcs plays a NHEJ-independent function in controlling replication fork speed. By promoting fork slowing and reversal, DNA-PKcs prevents excessive DNA damage during replication stress. DNA-PKcs inhibition in BRCA1/2-deficient cancer cells with acquired fork stability prevents fork slowing and restores cellular sensitivity to chemotherapy.

INTRODUCTION

The remodeling of stalled replication forks via fork reversal is key to prevent replication-associated DNA damage and protect genome stability (Berti et al., 2020). The inability to promote FR is associated with unrestrained DNA synthesis, increased chance of fork collisions and DNA breaks following DNA replication stress (Bai et al., 2020; Berti et al., 2013; Couch et al., 2013; Zellweger et al., 2015). Mechanistically, fork reversal occurs when newly synthesized DNA strands reanneal in a reaction catalyzed by RAD51 and other DNA translocases, such as SMARCAL1, ZRANB3, HLTF and FBH1 (Bai et al., 2020; Bétous et al., 2012; Fugger et al., 2015; Vujanovic et al., 2017; Zellweger et al., 2015). Regressed forks are highly dynamic intermediates that slow-down fork progression and delay fork restart (Berti et al., 2020). While fork reversal is believed to function as a protective mechanism for stressed replication forks, in certain contexts they also create the substrate for nascent strand degradation and genomic instability (Kolinjivadi et al., 2017; Lemaçon et al., 2017; Mijic et al., 2017; Taglialatela et al., 2017). Therefore, fork reversal requires tight regulation and the action of fork protection mechanisms (Liao et al., 2018). The need to control the nucleolytic processing of nascent DNA strands is highlighted by the fact that aggressive and genetically unstable cancers frequently display loss of factors involved in fork protection (e.g. BRCA1/2) (Schlacher et al., 2011, 2012).

Despite recent progress in the study of fork reversal, our current understanding of the genetic and molecular basis of this mechanism remains incomplete. In particular, little is known about the upstream events leading to fork reversal, including how specific replication structures are sensed and engaged by translocases to initiate fork regression. The DNA damage sensor kinases ATR, ATM and DNA-PKcs are candidates for this role given their ability to sense various DNA structures, including stalled replication forks and hard-to-replicate regions (Maréchal and Zou, 2013; Vidal-Eychenié et al., 2013). While the ATR and ATM kinases have been implicated in fork remodeling, with roles in forming and stabilizing reversed forks (Mutreja et al., 2018; Schmid et al., 2018), a role for the DNA-PKcs sensor kinase in replication fork remodeling remains unexplored. The DNA-PK complex, formed by the catalytic subunit DNA-PKcs and the KU70/80 heterodimer, is a key mediator of Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ), a mechanism for repairing DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) during V(D)J recombination (Helmink and Sleckman, 2012; Lieber, 2010; Ma et al., 2002). In addition to its role in NHEJ, DNA-PKcs has been recently described to play non-canonical functions in RNA processing, transcriptional regulation and regulation of the inflammatory response (Ferguson et al., 2012; Goodwin et al., 2015; Harding et al., 2017; Shao et al., 2020).

Here we found that DNA-PKcs is a key player in the control of fork dynamics and formation of reversed replication forks. DNA-PKcs inhibition or depletion, but not depletion of the NHEJ effector LIG4, impairs fork slowing and reversal in response to drugs that perturb DNA replication and results in increased replicative DNA damage and sensitivity to replication stress-inducing agents. DNA-PKcs inhibition in a mouse cellular model of human BRCA2-deficient breast cancer with acquired chemoresistance efficiently restored drug sensitivity by impairing fork slowing. Our study identifies a novel non-canonical role for DNA-PKcs in promoting fork slowing and reversal that is crucial to maintain genome stability and ensure cell survival following genotoxic stress.

RESULTS

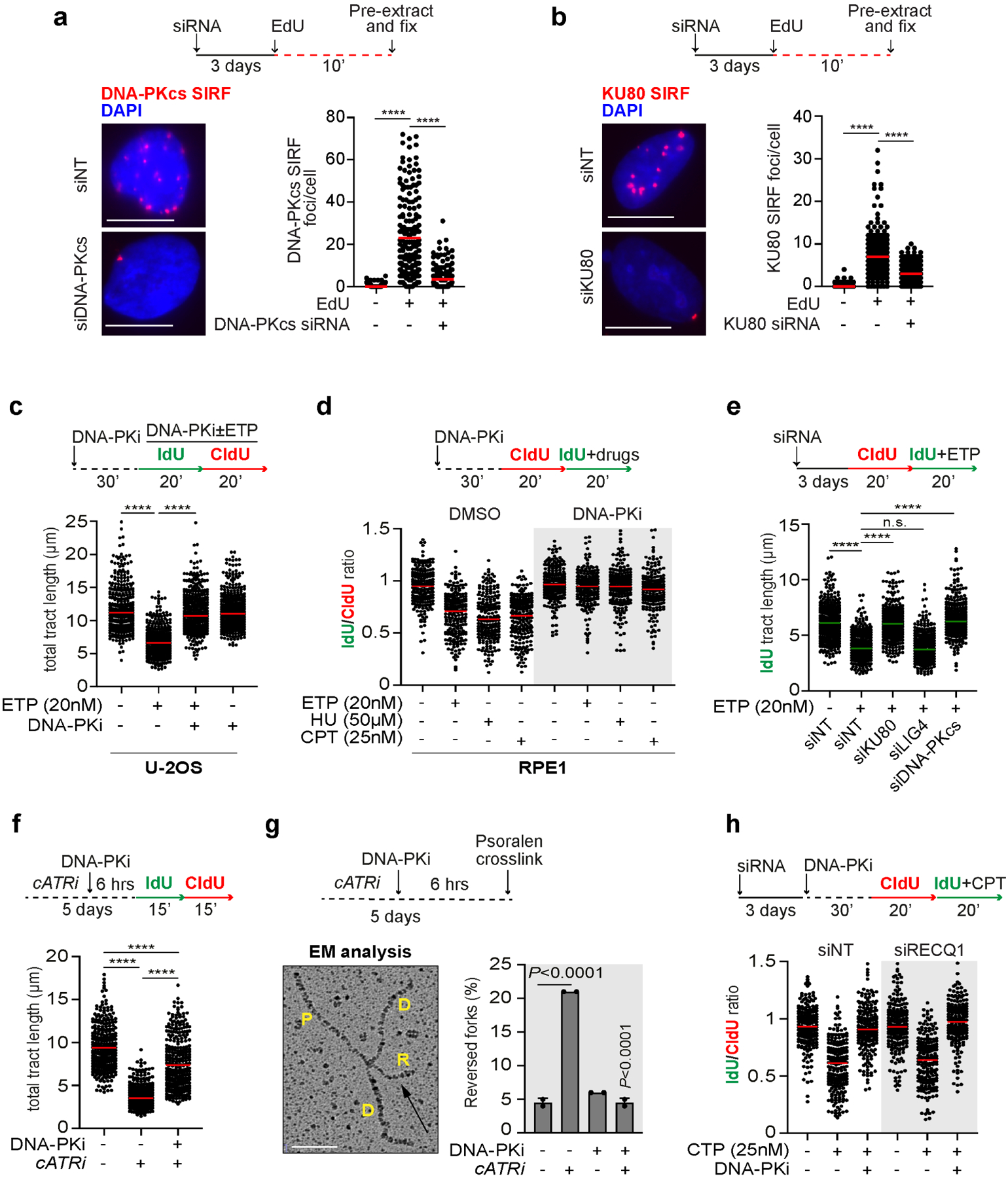

DNA-PKcs promotes fork slowing and reversal

To investigate a potential role for DNA-PKcs in the regulation of replication forks, we initially verified the ability of DNA-PKcs and KU to associate with replication forks using SIRF (in situ protein interaction with nascent DNA replication forks) (Roy et al., 2018). Consistent with published iPOND data (Nakamura et al., 2021; Ribeyre et al., 2016; Wessel et al., 2019), we observed robust recruitment of DNA-PKcs and KU80 to sites of DNA replication (Fig. 1a, b; Fig. S1a, b). We then used DNA fiber assay to analyze fork dynamics after treatment with etoposide (ETP), a drug known to induce fork slowing and reversal (Zellweger et al., 2015), and found that DNA-PKcs inhibition prevented ETP-induced fork slowing in U-2OS cells (Fig. 1c). Similar results were consistently observed in RPE1 and HeLa cells (Fig. 1d; Fig. S1c), where DNA-PKcs inhibition also prevented fork slowing induced by hydroxyurea (HU) and camptothecin (CPT) (Fig. 1d), suggesting a general requirement for DNA-PKcs in drug-induced fork slowing. DNA-PKcs association with replication forks did not increase after replication stress (Fig. S1d), consistent with a model in which DNA-PKcs associates with active forks to surveil DNA replication and trigger fork slowing upon replication stress. Depletion of DNA-PKcs, KU80, but not LIG4, also prevented ETP-induced fork slowing (Fig. 1e; Fig. S1e), indicating that the role of DNA-PKcs in the control of fork dynamics is independent of its role in NHEJ. Moreover, DNA-PKcs also controlled fork slowing after replication stress induced by chronic treatment with low-dose of the ATRi AZD6738 (cATRi) (Fig. 1f) (Dibitetto et al., 2020). Since fork reversal promotes replication stress-induced fork slowing (Berti et al., 2020), we examined the effect of DNA-PKi on the accumulation of reversed forks (RFs) using Electron Microscopy (EM) (Fig. 1g). Consistent with a role for DNA-PKcs in promoting fork reversal, DNA-PKcs inhibition completely abrogated cATRi-induced fork reversal (Fig. 1g). Loss of RF intermediates was unlikely caused by RECQ1-mediated branch migration since DNA-PKcs inhibition impaired drug-induced fork slowing in both WT and RECQ1-depleted cells (Fig. 1h; Fig. S1f). These results indicate that DNA-PKcs is broadly required for fork remodeling and is likely controlling early steps in fork reversal.

Figure 1. The DNA-PKcs-KU complex is broadly required for replication stress-induced fork slowing and reversal.

a) DNA-PKcs SIRF assay in RPE1 cells treated according to the indicated scheme. Dot plot shows the number of foci and the median from 180 cells in 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test. Scale bar 15 μm.

b) KU80 SIRF assay in RPE1 cells treated according to the indicated scheme. Dot plot shows the number of foci and the median from 180 cells in 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test. Scale bar 15 μm.

c) DNA fiber analysis in U-2OS cells treated according to the depicted scheme. At least 350 individual fibers for each condition were scored. Dot plot and median of total tract length are shown (n=3). **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test.

d) DNA fiber analysis in RPE1 cells treated according to the depicted scheme. Dot plot shows the IdU/CldU ratio from 200 individual fibers scored from 2 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test.

e) DNA fiber analysis in U-2OS cells transfected with the indicated siRNA and treated according to the indicated scheme. 300 individual fibers for each condition were scored. Dot plot and median of total tract length are shown (n=3). **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test.

f) DNA fiber analysis of U-2OS cells treated for 5 days with cATRi (AZD6738 0.4μM) followed by 6 hours with 5μM NU7441. 300 individual fibers for each condition were scored. Dot plot and median of total tract length are shown (n=3). **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test.

g) EM analysis of reversed forks following the same conditions as in (f). Electron micrograph represents a reversed replication fork. P, parental strand; D, daughter strand; R, regressed arm. The graph-bar shows the mean of reversed forks frequency from two independent EM experiments. P-values are calculated with unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

h) DNA fiber analysis in RPE1 cells treated according to the indicated scheme. Dot plot shows the individual IdU/CldU ratios and the median from 200 individual fibers scored from 2 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 One-way Anova test.

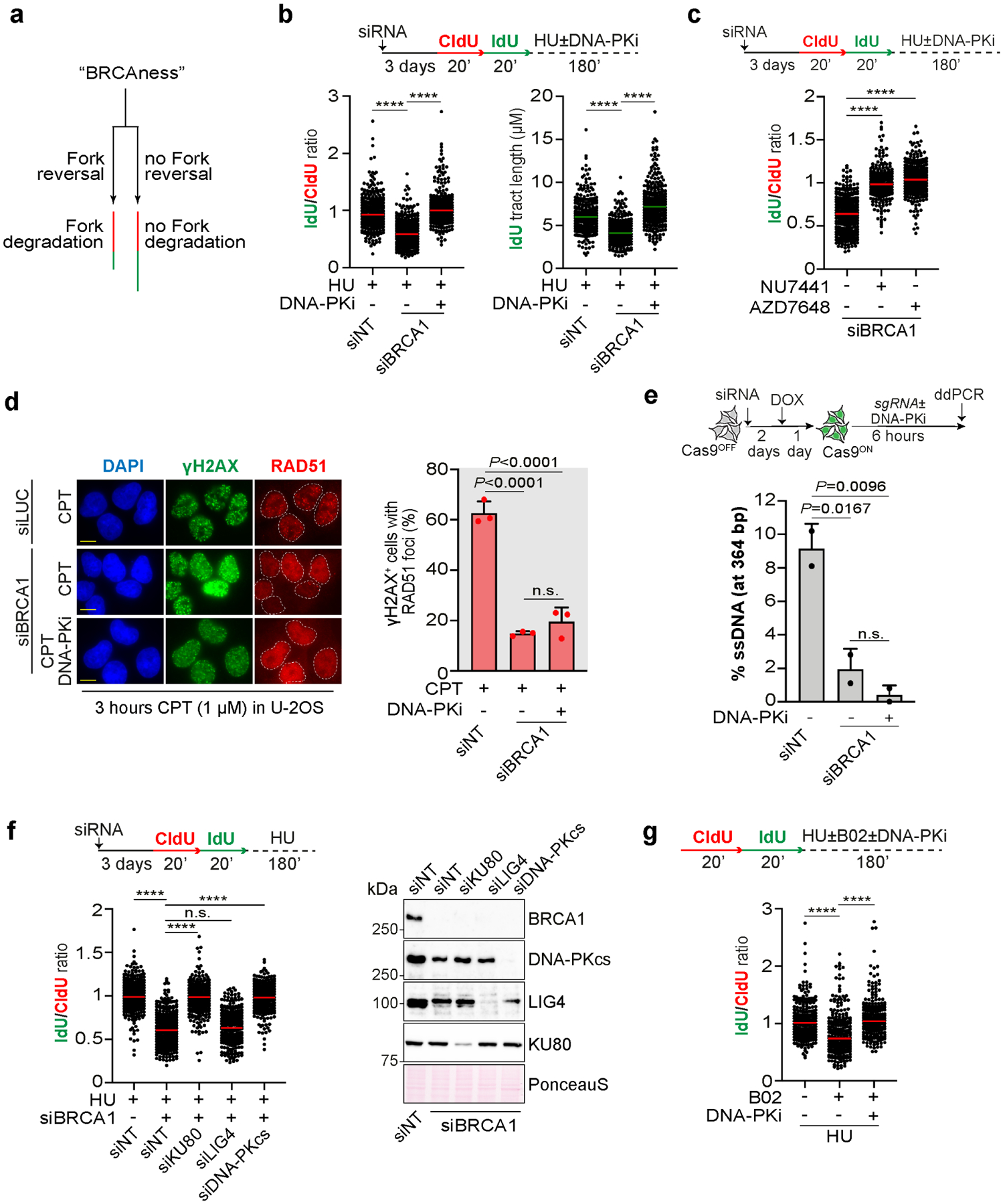

DNA-PKcs-mediated fork reversal leads to fork degradation upon BRCA deficiency

Previous works showed that blocking fork reversal prevents fork degradation in cells deficient for fork protection factors such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Lemaçon et al., 2017; Mijic et al., 2017; Taglialatela et al., 2017). Based on our findings, we postulated that DNA-PKcs inhibition should also prevent fork degradation in these cells. Using a DNA fiber assay for monitoring fork degradation (Fig. 2a), we found that inhibition of DNA-PKcs prevents fork degradation in BRCA1-depleted cells after HU treatment (Fig. 2b, c). Loss of fork degradation was unlikely associated with restoration of fork protection, since DNA-PKcs inhibition failed to restore the recruitment of the recombination and fork protection factor RAD51 at replication-damaged sites in BRCA1-depleted cells (Fig. 2d). Moreover, DNA-PKcs inhibition did not significantly affect ssDNA accumulation in BRCA1-deficient cells at Cas9-induced breaks (Fig. 2e), suggesting that DNA-PKcs is not involved in nuclease regulation at DNA ends in cells lacking BRCA1 activity. Consistent with previous results in Figure 1e, the role of DNA-PKcs in counteracting fork degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells was also dependent on KU80, but independent of LIG4 (Fig. 2f). Moreover, consistent with a general dependency on DNA-PKcs for nascent strand degradation, DNA-PKcs inhibition efficiently rescued fork degradation in cells treated for a short period with the RAD51 inhibitor B02 (Fig. 2g), which also disrupts fork protection (Taglialatela et al., 2017).

Figure 2. DNA-PKcs promotes fork degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells.

a) Schematic of a DNA fiber assay to monitor fork degradation in BRCA-deficient cells.

b) DNA fiber analysis in U-2OS cells transfected with the indicated siRNA according to the depicted scheme. Dot plot shows the IdU/CldU ratio and the individual IdU tract length from 300 individual fibers and the median from 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 unpaired One-way Anova test.

c) DNA fiber assay performed as in (b). Dot plot shows IdU/CldU ratio from 300 individual fibers from 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 unpaired One-way Anova test.

d) RAD51 foci analysis in U-2OS cells transfected with the indicated siRNA and treated as indicated. Bar graph shows the percentage of γH2AX+ and RAD51+ cells from 3 independent biological replicates. P-values were calculated with the One-way Anova test. Scale bar 10μm.

e) Resection assay. ssDNA was measured at Cas9-induced breaks in U-2OS TetON-eGFP-Cas9 cells transfected with the indicated siRNA. Bar graph shows the percentage of ssDNA at 364bp from Cas9 site from 2 independent biological replicates. P-values are calculated with unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

f) DNA fiber analysis in U-2OS cells done as in (b). Dot plot shows the IdU/CldU ratio and the individual IdU tract length from 300 individual fibers and the median from 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 unpaired One-way Anova test.

g) DNA fiber analysis in U-2OS cells done following the depicted scheme. Dot plot shows IdU/CldU ratio from 300 individual fibers and the median from 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 unpaired One-way Anova test.

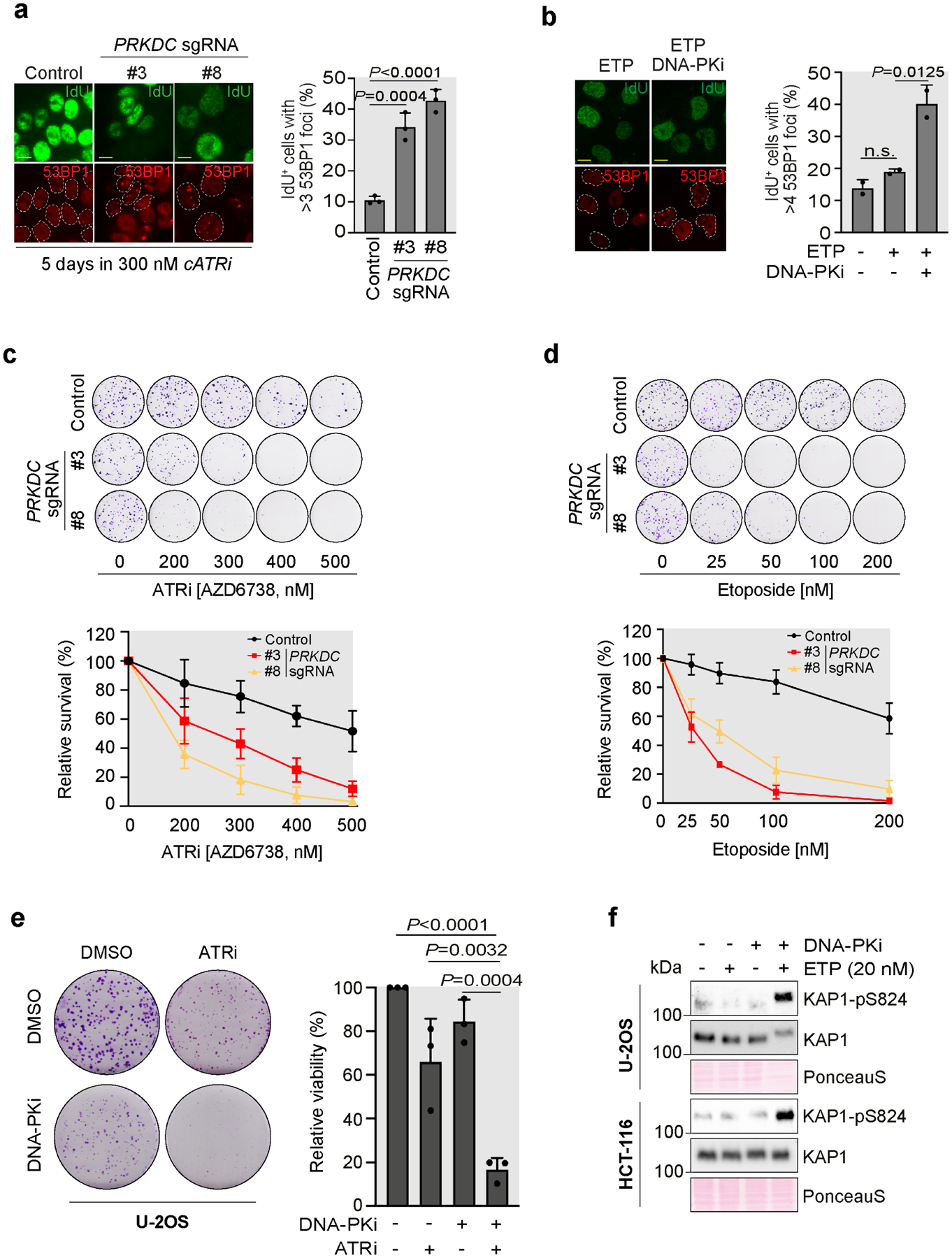

DNA-PKcs-mediated fork reversal prevents DNA damage and maintains genome integrity during replication

In light of our findings, we hypothesized that DNA-PKcs-mediated fork reversal could protect replicating cells from deleterious fork collisions and genome instability. This would be in sharp contrast with the role of DNA-PKcs in promoting NHEJ, which drives lethal chromosomal rearrangements upon replication-induced one-ended DSBs (Adamo et al., 2010; Balmus et al., 2019; Bunting et al., 2010; Dibitetto et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2011). To test our hypothesis, we generated HCT-116-derivative cells where DNA-PKcs was stably depleted by CRISPR-Cas9 (Fig. S2a) and confirmed that these cells do not undergo cATRi-induced fork slowing (Fig. S2b). Consistent with our hypothesis, knock-down of DNA-PKcs increased the number of 53BP1 foci induced by cATRi in S-phase cells (Fig. 3a), which indicates the presence of replication-born DNA damage. Similar results were obtained when DNA-PKcs was inhibited upon treatment with low doses of ETP (Fig. 3b). Consistent with the increased DNA damage observed upon loss of DNA-PKcs activity, DNA-PKcs-deficient, but not control, cells showed high sensitivity to low doses of the ATR inhibitor AZD6738 in combination with low doses of ETP (Fig. 3c, d). Similar results were also obtained via DNA-PKcs chemical inhibition, which synergistically inhibited cell growth in combination with cATRi (Fig. 3e), and induced DSB signaling in combination with low ETP doses in U-2OS and HCT-116 cells (Fig. 3f).

Figure 3. DNA-PKcs-mediated fork reversal prevents replication-associated DNA damage and is associated with increased tolerance to replication stress.

a) IdU+ cells with >3 53BP1 foci in HCT-116 control or PRKDC depleted clones treated as indicated. Plotted values are the mean of 3 independent biological replicates ±SD. P-values were calculated with the One-way Anova test. Scale bar 10μm.

b) IdU+ cells with >4 53BP1 foci in U-2OS cells treated or mock with NU7441 (5μM) as indicated. Plotted values are the mean of 2 independent biological replicates ±SD. P-values were calculated with the One-way Anova test. Scale bar 10μm.

c) Clonogenic survival assay in HCT-116 control or PRKDC depleted clones treated with the indicated concentrations of AZD6738 for 12 days. The graph shows relative survival curves from 3 independent biological replicates ±SD.

d) Clonogenic survival assay in HCT-116 control or PRKDC depleted clones treated with the indicated concentrations of ETP for 12 days. The graph shows relative survival curves from 3 independent biological replicates ±SD.

e) Clonogenic survival assay in U-2OS cells treated with ATRi AZD6738 (0.4μM) with or without the DNA-PKi NU7441 (2.5μM) for 10 days. The graph shows relative survival curves from 3 independent biological replicates ±SD. P-values relative to control cells were calculated with the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

f) Immunoblot analysis of U-2OS and HCT-116 cells treated with ETP (20nM) and NU7441 (5μM).

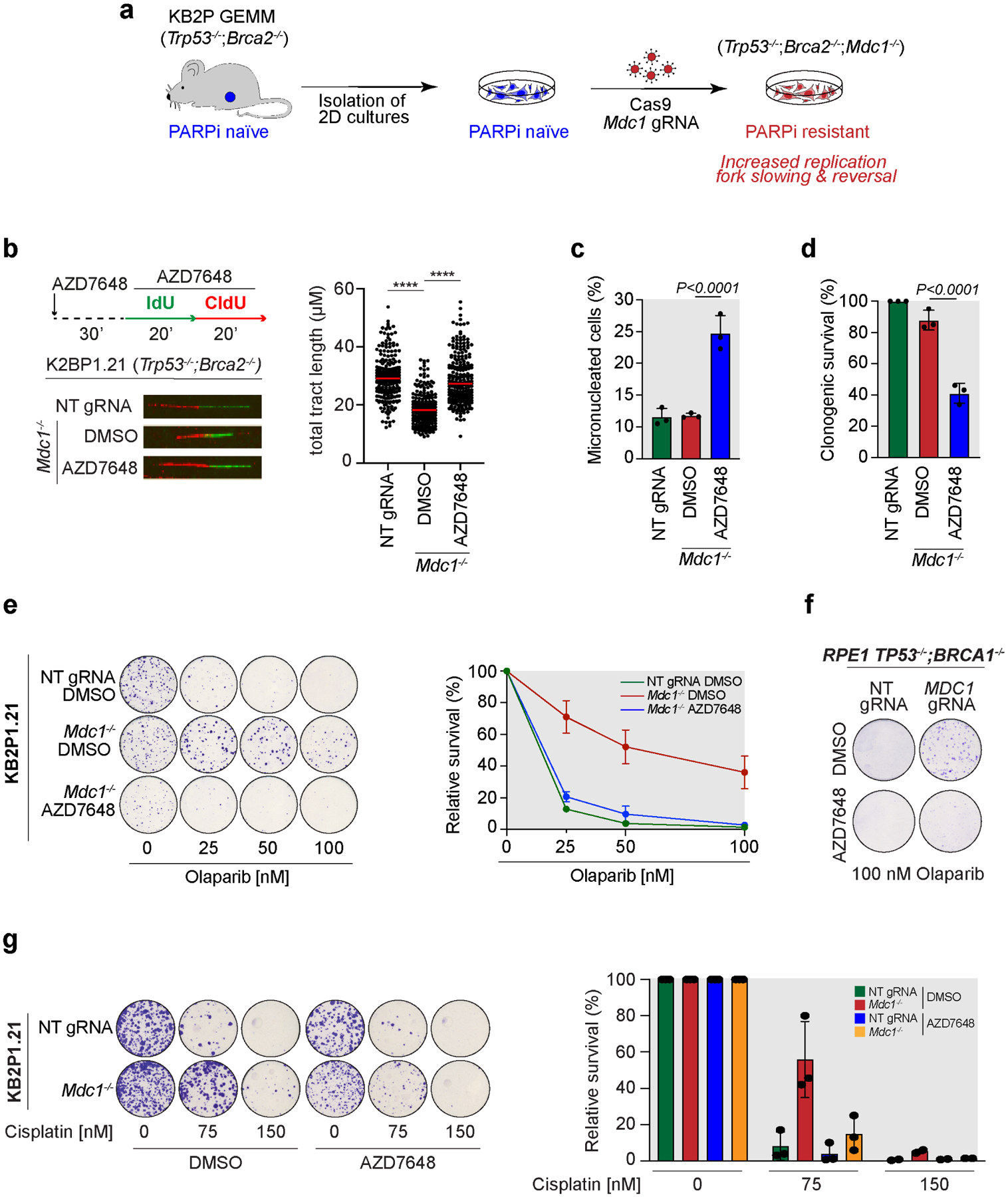

DNA-PKcs inhibition restores PARPi sensitivity in BRCA2-deficient mammary tumors with acquired chemoresistance

A recent genome wide CRISPR knock-out screen performed by the Rottenberg Lab found that loss of Mdc1, a DNA damage response scaffolding protein, promotes PARPi resistance in Brca2−/− cells (KB2P1.21) (Liptay et al. 2022; Preprint at bioRxiv) (Fig. 4a). Mechanistically, loss of Mdc1 increased drug tolerance by promoting fork reversal and actively reducing fork speed (Liptay et al. 2022; Preprint at bioRxiv). In this scenario, we asked if DNA-PKcs was required for fork slowing observed in KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− cells. Strikingly, DNA fiber analysis revealed that fork slowing was abolished by treatment with the DNA-PKcs inhibitor AZD7648 in KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− cells (Fig. 4b). Thus, our findings consistently show that DNA-PKcs is required for fork slowing and reversal induced by chemical (Figs. 1–2) and genetic (Fig. 4b) perturbations, and further establish DNA-PKcs as a central player in the control of fork dynamics. Moreover, consistent with the strict requirement for fork slowing during DNA replication in KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− cells, DNA-PKi AZD7648 treatment elevated genomic instability in the absence of any additional genotoxins, as shown by the significant increase of micronucleated cells (Fig. 4c) and decrease in cellular proliferation (Fig. 4d). Importantly, AZD7648 treatment did not have noticeable effects on cellular viability in KB2P1.21 Trp53−/− ;Brca2−/− cells where replication forks travel at normal speed (Fig. S3a).

Figure 4. Loss of DNA-PKcs-mediated fork remodeling restores PARPi sensitivity in BRCA2-deficient mammary tumor cells with acquired chemoresistance.

a) General workflow of Mdc1 knock-out in KB2P1.21 (Trp53−/−;Brca2−/−) cells according to Liptay et al. (manuscript submitted).

b) DNA fiber analysis in KB2P1.21 NT gRNA and Mdc1−/− cells treated according to the depicted labeling scheme. Dot plot shows the total tract length from 200 individual fibers and the median for each condition scored from 3 biological replicates. **** p<0.001 unpaired One-way Anova test.

c) Bar graph showing the percentage of micronucleated KB2P1.21 NT gRNA and Mdc1−/− cells treated, or mock treated, with AZD7648 (2μM) for 48 hours. Plotted values are the mean of 3 independent biological replicates ±SD. P-values were calculated with the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

d) Clonogenic survival assay of KB2P1.21 NT gRNA and Mdc1−/− cells treated, or mock treated, with AZD7648 (2μM) for 10 days. Plotted values are the mean of 3 independent biological replicates ±SD. P-values were calculated with the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test.

e) Clonogenic survival assay in KB2P1.21 NT gRNA and Mdc1−/− cells treated with the indicated concentrations of Olaparib with or without AZD7648 (2μM) for 12 days. The graph shows relative survival from 3 independent biological replicates ±SD.

f) Clonogenic survival assay in RPE1 TP53−/−;BRCA1−/− NT gRNA and MDC1−/− cells treated with 100nM Olaparib with or without AZD7648 (2μM) for 12 days.

g) Clonogenic survival assay in KB2P1.21 NT gRNA and Mdc1−/− cells treated with the indicated concentrations of cisplatin with or without AZD7648 (2μM) for 10 days. The graph shows relative survival from 3 independent biological replicates ±SD.

The Rottenberg Lab recently proposed that active fork slowing and reversal can stabilize stressed forks and increase PARPi resistance in KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− cells (Liptay et al. 2022; Preprint at bioRxiv). For this reason, we postulated that the effect of DNA-PKcs inhibition in preventing fork slowing would revert PARPi resistance. By analyzing PARPi sensitivity in KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− cells, we found that combination of DNA-PKi AZD7648 with low doses of PARPi Olaparib completely disrupted PARPi resistance, restoring cellular sensitivity to the same level as in the parental KB2P1.21 line (Fig. 4e). This effect was also reproduced in human RPE1 TP53−/−;BRCA1−/−;MDC1−/− cells (Fig. 4f), but not in KB1P Trp53−/−;Brca1−/−;Tp53bp1−/− cells, which exploit HR restoration rather than fork stabilization as a mechanism of chemoresistance (Fig. S3b). Moreover, DNA-PKcs inhibition also restored sensitivity to cisplatin (Fig. 4g), another anti-cancer agent frequently used in BRCA-mutated triple-negative breast cancer (Rottenberg et al., 2021).

DISCUSSION

Here we report a crucial role for DNA-PKcs in replication fork reversal. This novel non-canonical role for DNA-PKcs is independent of LIG4 and, therefore, independent of NHEJ repair. Strikingly, DNA-PKcs is required for fork slowing in response to a range of chemical and genetic perturbations to DNA replication, supporting the centrality of DNA-PKcs in fork reversal. Since inhibition of DNA-PKcs promotes fork breakage and sensitivity to replication stress (Fig. 3), DNA-PKcs-mediated fork reversal seems important to stabilize stressed forks. Thus, our findings highlight how DNA-PKcs action can differently regulate genome stability depending on the context it operates. In response to replication-born DSBs, DNA-PKcs drives toxic NHEJ leading to lethal chromosomal rearrangements (Adamo et al., 2010; Balmus et al., 2019; Bunting et al., 2010; Dibitetto et al., 2020; Patel et al., 2011). In the context of replicative stress, we propose that DNA-PKcs acts proactively to promote fork reversal, prevent fork breakage and secure genomic integrity.

While our results establish the first connection between DNA-PKcs and the control of fork reversal, previous reports have documented the involvement of DNA-PKcs and other NHEJ factors in the restart of stalled and collapsed forks (Chen et al., 2019; Teixeira-Silva et al., 2017; Ying et al., 2016). While we cannot exclude a potential role for NHEJ proteins in counteracting fork processing, our results in BRCA1-deficient or RECQ1-deficient cells strongly suggest that DNA-PKcs and KU act upstream to regulate the formation of RFs. Based on these observations, and on our data showing the strong pre-association of the DNA-PK complex with unstressed forks, it is tempting to speculate that DNA-PK may associate with replication forks independently of its mode of interaction with DNA ends. Therefore, we do not favor the involvement of DSB ends or the end of regressed arms of an already formed RF in the recruitment of DNA-PKcs. While the nature of such mode of association of DNA-PKcs with active replisomes remains unknown, our findings are in line with the model that the DNA-PK complex dynamically associates with regions nearby active DNA synthesis to preemptively sense aberrant DNA replication intermediates, and act at early steps leading to the decision to promote fork reversal and slow down replication.

Since the ability of cancer cells to promote fork reversal is expected to affect chemotherapy outcomes, we predict that the manipulation of fork reversal through the use of DNA-PKcs inhibitors will find applications in cancer therapy. Cancer cells are known to acquire resistance to PARP inhibitors and other drugs through mechanisms that restore replication fork stability (Gogola et al., 2019), however, the ability to manipulate these mechanisms in cancer therapy has been limited. Important knowledge gaps in our understanding of the required factors involved in the control of fork reversal have prevented progress toward developing efficient chemical approaches that selectively impair fork reversal without causing major undesirable effects in noncancerous cells. Given that DNA-PKcs inhibitors have already been used in clinical trials, mostly as adjuvants in radiotherapy (www.clinicaltrials.gov), we envision that our study will bring important new insights into how these inhibitors may be repurposed for more rationalized therapeutic interventions. Our results exploring the use of DNA-PKcs inhibition to revert PARPi resistance in Brca2-deficient mammary tumor cells provide a defined path forward, and suggest that DNA-PKcs inhibitors would become particularly effective in the treatment of tumors that exploit fork reversal for chemoresistance. In the future, techniques to detect reversed forks and/or measure fork speed directly in tumor biopsies and/or patient-derived cancer organoids could be particularly useful in directing which tumors would be more efficiently targeted by a combination therapy that includes DNA-PKcs inhibitors.

Limitations of the study:

The molecular mechanism by which DNA-PKcs promotes fork reversal remains unknown. Technical limitations prevented us from monitoring how the engagement of translocases at replication forks is affected by DNA-PKcs. We were unable to detect translocases, including SMARCAL1, in our iPOND mass spectrometry analyses despite others being able to do so, which might be due to differences in our experimental conditions that use lower concentrations of HU or CPT. Understanding how DNA-PKcs affects the action of translocases represents an important area for further exploration. In addition, future work will be necessary to map DNA-PKcs signaling in response to replication stress and to identify the target(s) of DNA-PKcs that mediate fork reversal.

STAR METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Marcus Smolka (mbs266@cornell.edu).

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact without restrictions.

Data and code availability

All data is available in the main text, supplemental materials, or via Mendeley at https://doi:10.17632/n3r6jsmryr.1

The paper does not report any original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Source of cell lines used in the study is reported in the Key Resources Table.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-Actin (15G5A11/E2) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#MA1-140; RRID: AB_2536844 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU (B44) | BD Biosciences | Cat#347580; RRID: AB_10015219 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-BrdU [BU/75-(ICR1)] | Abcam | Cat#ab6326; RRID: AB_305426 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-DNA-PKcs | Bethyl Laboratories | Cat#A300-516A; RRID: AB_451041 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Phospho-KAP1 (Ser824) | Bethyl Laboratories | Cat#A300-767A; RRID: AB_669740 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KAP1 | Bethyl Laboratories | Cat#A300-274A; RRID: AB_185559 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KU80 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2753; RRID: AB_ 2257526 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-LIG4 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-271299; RRID: AB_10610371 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-KAP1 | Bethyl Laboratories | Cat#A300-274A; RRID: AB_185559 |

| Alexa Fluor 488 Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H+L) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A11001; RRID: AB_2534069 |

| Alexa Fluor 594 Goat anti-Rat IgG (H+L) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A11007; RRID: AB_10561522 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG - HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#NA931V; RRID: AB_228307 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG - HRP | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#NA934V; RRID: AB_228213 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| AZD6738 (ATRi) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S7693; CAS: 1352226-88-0 |

| B02 (RAD51i) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S8434; CAS: 1290541-46-6 |

| olaparib (PARPi) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S1060; CAS: 763113-22-0 |

| NU7441 (DNA-PKi) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S2638; CAS: 503468-95-9 |

| AZD7648 (DNA-PKi) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S8843; CAS: 2230820-11-6 |

| EdU | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A10044 |

| IdU | Millipore Sigma | Cat#I7125; CAS: 54-42-2 |

| CldU | Millipore Sigma | Cat#C6891; CAS: 50-90-8 |

| Hydroxyurea (HU) | Tokyo Chemical Industry | Cat#H0310; CAS: 127-07-1 |

| Etoposide (ETP) | Selleck Chemicals | Cat#S1225; CAS: 33419-42-0 |

| Camptotechin (CPT) | Millipore Sigma | Cat#C991; CAS: 7689-03-4 |

| Puromycin dihydrochloride | VWR | Cat#AAJ61278; CAS: 58-58-2 |

| 1X ddPCR™ Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) | Bio-Rad | Cat#1863023 |

| DG8™ cartridge | Bio-Rad | Cat#1864008 |

| Droplet generation oil | Bio-Rad | Cat#1863005 |

| DG8™ droplet generator gaskets | Bio-Rad | Cat#1864007 |

| Goat Serum | Millipore Sigma | Cat#G9023 |

| Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI | Vector Laboratories | Cat#H-1200 |

| Fluoromount-G mounting medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#00-4958 |

| Polybrene Infection/Transfection reagent | Millipore Sigma | Cat#TR-1003-G |

| RNAi MAX Transfection reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#13778075 |

| PhosSTOP | Millipore Sigma | Cat#04-906-837-001 |

| Amersham Protran 0.2 mm NC (Nitrocellulose Blotting Membrane) GE | GE Healthcare Life Sciences | Cat#10600001 |

| Sodium deoxycholate | Millipore Sigma | Cat#D6750; CAS: 302-95-4 |

| 1,4-Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Millipore Sigma | Cat#11583786001; CAS: 3483-12-3 |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) | Millipore Sigma | Cat#L4509; CAS: 151-21-3 |

| Triton X-100 | Millipore Sigma | Cat#T9284; CAS: 9002-93-1 |

| Tween-20 | Millipore Sigma | Cat#P1379; CAS: 9005-64-5 |

| Methanol | VWR | Cat#BDH1135; CAS: 67-56-1 |

| Acetic acid glacial | VWR | Cat#97065-042; CAS: 64-19-7 |

| Hydrochloride acid | VWR | Cat#470301; CAS: 7647-01-0 |

| Bovine Serum Albumine (BSA) | Millipore Sigma | Cat#29102 |

| Formaldehyde solution | VWR | Cat#AA33314; CAS: 50-00-0 |

| DMEM | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#11885084 |

| DMEM/F12 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#10565018 |

| Fetal Calf Serum | Cytiva Life Sciences | Cat#SH30073.02 |

| Penicillin/Streptomycin solution | Corning | Cat#30-002-Cl |

| Non-essential aminoacids solution | Corning | Cat#25-025-Cl |

| DPBS solution | Corning | Cat#21-031-CV |

| Trypsin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#25200056 |

| Trypan blue solution | Corning | Cat#25-900-Cl |

| ECL Clarity | Bio-Rad | Cat#1705061 |

| ECL Clarity max | Bio-Rad | Cat#1705062 |

| Microscope frosted slides | VWR | Cat#48300 |

| Microscope slides (DNA fiber assay) | Newcomer Supply | Cat#5070 |

| Crystal violet | Millipore Sigma | Cat#C0775; CAS: 548-62-9 |

| PAGE ruler pre-stained protein ladder | Bio-Rad | Cat#1610374 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Nucleospin™ Tissue Kit | Macherey-Nagel | Cat#740952 |

| Universal Mycoplasma Detection Kit | ATCC | Cat#30-1012K |

| Monarch Plasmid Miniprep Kit | New England Biolabs | Cat#T1010L |

| Experimental models: cell lines | ||

| Human: U-2OS | ATCC | N/A |

| Human: HEK293T | N/A | |

| Human: HeLa | N/A | |

| Human: RPE1 | ATCC | N/A |

| Human: HCT-116 | ATCC | N/A |

| Human: U-2OS-SEC (TeTON-eGFP-Cas9) | (Dibitetto et al. 2020) | N/A |

| Mouse: KB2P1.21 NT sgRNA | Sven Rottenberg lab | N/A |

| Mouse: KB2P1.21 Mdc1−/− clone B5 | Sven Rottenberg lab | N/A |

| Human: RPE1 TP53−/− | (Zimmermann et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Human: RPE1 TP53−/− BRCA1−/− | (Noordermeer et al., 2018) | N/A |

| Human: RPE1 TP53−/− BRCA1−/− MDC1 gRNA | Sven Rottenberg lab | N/A |

| Mouse: KB1P-G3 | (Jaspers et al., 2013) | N/A |

| Mouse: KB1P-G3B1+ NT sgRNA | (Barazas et al., 2019) | N/A |

| Mouse: KB1P-G3+ Tr53bp1−/− | (Barazas et al., 2019) | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Non-Targeting siRNA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#PN465377 |

| DNA-PKcs siRNA | Dharmacon | Cat#D-005030-01-0002 |

| KU80 siRNA | Dharmacon | Cat#D-010491-01-0002 |

| LIG4 siRNA | Dharmacon | Cat#D-004254-01-0002 |

| RECQ1 siRNA | Mycrosinth | |

| BRCA1 siRNA | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#HSS101089 |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Plasmid: PRKDC gRNA1 (BRDN0001149021) | John Doench & David Root lab | Addgene plasmid#77864; RRID: Addgene_77864 |

| Plasmid: PRKDC gRNA2 (BRDN0001146589) | John Doench & David Root lab (Chen et al., 2017) | Addgene plasmid#77861; RRID: Addgene_77861 |

| Plasmid: pX330.puro | Sandra Martha Gomes Dias lab | Addgene plasmid#110403; RRID: Addgene_110403 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji | (Schindelin et al., 2012) | https://fiji.sc/ |

| ImageLab | Bio-Rad | https://www.bio-rad.com/en-us/product/image-lab-software?ID=KRE6P5E8Z |

| GraphPad Prism 8 | GraphPad Software, Inc | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| LAS (Leica Application Suite) AF Software | Leica | https://www.leica-mycrosystems.com/products/microscope-software/ |

| QuantaSoft™ | Bio-Rad | https://www.bio-rad.com |

Cell culture and cell lines

RPE1, U-2OS, HeLa and HCT-116 cells were grown at 37°C in humidified chambers in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% Bovine Calf Serum (BCS), 1% non-essential amino acids and penicillin/streptomycin solution (100 U/ml). HCT-116-PRKDC depleted clones were generated by transducing HCT-116 parental cells with two distinct sgRNAs targeting the PRKDC gene and a doxycycline-inducible Cas9. Cas9 was then activated by doxycycline treatment for 3 days followed by clone isolation after 10 days of outgrowth. U-2OS-SEC (TeTON-eGFP-Cas9) were previously generated (Dibitetto et al., 2020). eGFP-Cas9 was induced by doxycycline 24 hours prior to sgRNA transfection.

KB2P1.21 (Trp53−/−;Brca2−/−) NT and Mdc1−/− and KB1P-derivative cell lines were grown at 3% O2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium Nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Gibco) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), penicillin/streptomycin solution (50 U/ml), 5 ng/ml cholera toxin (Sigma Aldrich), insulin (5 μg/ml, Sigma Aldrich) and 5 ng/ml murine Epidermal Growth Factor (mEGF, Sigma Aldrich).

Human RPE1 TP53−/− and RPE1 TP53−/−;BRCA1−/− cells were a kind gift from Daniel Durocher and were grown at 3% O2 in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium Nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12; Gibco) and penicillin/streptomycin solution (50 U/ml).

All cell lines were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

METHOD DETAILS

Oligos and plasmids

PRKDC gRNA (BRDN0001149021 and BRDN0001146589) were a gift from John Doench & David Root (Addgene plasmid #77864; RRID:Addgene_77864 and Addgene plasmid #77861; RRID:Addgene_77861 respectively) (Doench et al., 2016).

RNAi

RNAiMAX (Thermo fisher Scientific) was used to deliver siRNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following siRNAs used in this study were purchased from Dharmacon: siDNA-PKcs (#D-005030-01-0002), siKU80 (#D-010491-01-0002), siLIG4 (#D-004254-01-0002). The following siRNAs used in this study were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific: siNT (#PN465377) and siBRCA1 (#HSS101089). siRECQ1 (5’-UUACCAGUUACCAGCAUUATT-3’) was synthetized by Microsynth.

Drugs and reagents

The following chemical reagents were used throughout the study: AZD6738 (Selleck Chemicals; #S7693), B02 (Selleck Chemicals; #S8434), Olaparib (Selleck Chemicals; #S1060), NU7441 (Selleck Chemicals; #S2638), AZD7648 (Selleck Chemicals; #S8843), Etoposide (Selleck Chemicals; #S1225), Camptotechin (Millipore Sigma; #PHL89593), 5-Iodo-2’-deoxyuridine (IdU) (Millipore Sigma; #I7125), 5-Chloro-2’-deoxyuridine (CldU) (Millipore Sigma; #C6891), Hydroxyurea (Tokyo Chemical Industry; #H0310), Doxycycline (Millipore Sigma; #D1822).

Protein extraction and western blot analysis

Cells were lysed in ice-cold modified RIPA buffer (50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% Tergitol, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 5mM EDTA supplemented with complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), 1mM PMSF and 5mM NaF) for 30’ at 4°C. Lysates were then sonicated and cleared by centrifugation. Protein extracts were quantified with Bradford (Bio-Rad), and 20μg of proteins was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes and chemiluminescent signal was acquired with a Chemidoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Images were processed with the ImageLab software (Bio-Rad). The primary antibodies used in this study are listed in the Key Resource Table.

DNA Fiber assay

We analyzed DNA fiber length as previously described (Quinet et al., 2017). In brief, exponentially growing cells were first labeled with 25 μM IdU for 15’ followed by 250 μM CldU 15’ incubation. Cells were then harvested by centrifugation, washed with PBS, and approximately 2,000 cells were spotted onto glass slides. Cells were mixed on the slide with lysis buffer (200mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS) for 3’. After this incubation step, slides were tilted at 30° to allow uniform fiber spreading. Slides were air-dried for 5’, fixed at RT for 10’ in Methanol-Acetic Acid (3:1), and stored at 4°C overnight. The day after, slides were denatured 1 hour in 2.5M HCl, quickly washed in PBS, and blocked for 1 hour in 10% PBS-BSA. Newly replicated DNA was stained for 2 hours with primary antibodies anti-IdU (BD Biosciences; #347580) and anti-CldU (Abcam; #BU1/75 (IC1)). Slides were then washed three times in PBS followed by 1 hour with the secondary antibodies anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 and anti-rat Alexa Fluor 594. Slides were washed three times in PBS, mounted with Fluoromount G (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and sealed with nail polish. Images were acquired using a Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescent microscope with a 63x objective. The images were processed with the ImageJ software. Statistical analysis of fiber length was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was determined by Student t-test if comparing two conditions or one-way ANOVA test for multiple comparisons.

SIRF (in Situ analysis of protein Interactions at DNA Replication Forks)

SIRF assay was performed as previously reported (Roy et al., 2018). Cells were seeded on coverslips and the following day they were pulsed with 25μM EdU for 10’. After the EdU pulse, cells were initially pre-extracted with CSK buffer on ice for 5’ and then fixed with 3.7% Paraformaldehyde at RT for 10’. Coverslips were then washed with PBS and stored O/N at 4°C. The following day cells were permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 5’ and then the Click reaction (100mM Tris pH 8, 100mM CuSO4, 2mg/ml sodium-L-ascorbate, 10mM biotin-azide) was performed for 90’ at 37°C. Slides were then blocked for 1 hour at 37°C with blocking solution (PBS, BSA 2%, glycine 0.15%, Triton X-100 0.1%), followed by incubation with primary antibodies for 1 hour at 37°C (mouse anti-DNA-PKcs 1:500; rabbit anti-KU80 1:200, mouse anti-biotin 1:200, rabbit anti-biotin 1:1000 diluted in blocking solution). After antibody incubation, coverslips were washed 2X with Buffer A for 5’at RT (Duolink kit). Each coverslip was then incubated for 1 hour at 37°C with Duolink PLA probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) diluted in blocking solution. After 2X washes with Buffer A for 5’at RT, probes were ligated for 30’ at 37°C and amplified by polymerase reaction for 100’ at 37°C. Coverslips were then washed 2X with Buffer B for 5’at RT (Duolink kit) and then mounted with DAPI on microscope slides. Images were acquired on multiple stacks using the DeltaVision Elite widefield microscope with a 60X objective. Deconvolution of the images was done using the softWoRx DeltaVision software. The number of foci in each cell was counted with ImageJ and the statistical analysis was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software).

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were seeded on coverslips and subjected to the indicated treatments. On the last day, cells were washed in PBS and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10’. Cells were then permeabilized for 5’ and blocked for 20’ with 10%PBS-BSA at RT. Primary antibodies were diluted in 3%PBS-BSA and incubated for 2 hours at RT. Coverslips were then washed three times 5’ with PBS followed by 1-hour incubation at RT with a secondary antibody (Alexafluor 488, 1:600). Coverslips were washed three times with PBS and then mounted with DAPI on microscope slides. Images were acquired using a Leica DMi8 inverted fluorescent microscope with a 63x objective. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance was determined by two tailed t-test. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-53BP1 (Novusbio; #NB100–304), anti-BrdU (BD Biosciences; #347580), anti-RAD51 (Millipore Sigma; #PC130), anti-H2AX-pS139 (Millipore Sigma; #JBN301). The secondary antibodies used were Goat anti-Mouse 488 IgG-HRP (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #A11001) and Donkey anti-Rabbit 568 IgG-HRP (Thermo Fisher Scientific; #A10042).

Electron Microscopy (EM)

Asynchronous sub confluent U-2OS cells were treated for five days with 0.4uM AZD6738 or DMSO. Cells were collected, resuspended in ice-cold PBS and crosslinked with 4,5′, 8-trimethylpsoralen (10 μg/ml final concentration), followed by irradiation pulses with UV 365 nm monochromatic light (UV Stratalinker 1800; Agilent Technologies). For DNA extraction, cells were lysed (1.28 M sucrose, 40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 20 mM MgCl2, and 4% Triton X-100; Qiagen) and digested (800 mM guanidine–HCl, 30 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 30 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 5% Tween-20, and 0.5% Triton X-100) at 50 °C for 2 h in presence of 1 mg/ml proteinase K. The DNA was purified using chloroform/isoamylalcohol (24:1) and precipitated in 0.7 volume of isopropanol. Finally, the DNA was washed with 70% EtOH and resuspended in 200μl TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer. 100 U of restriction enzyme (PvuII high fidelity, New England Biolabs) were used to digest 6μg of mammalian genomic DNA for 5 h. RNase A (Sigma–Aldrich, R5503) to a final concentration of 250 ug/ml was added for the last 2 h of this incubation. The digested DNA was cleaned up using the Silica Bead DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The Benzyldimethylalkylammonium chloride (BAC) method was used to spread the DNA on the water surface and then load it on carbon-coated 400-mesh nickel grids (G2400N, Plano Gmbh). Subsequently, DNA was coated with platinum using a High Vacuum Evaporator BAF060 (Leica). The grids were scanned using a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2 Spirit; FEI; LaB6 filament; high tension ≤120 kV) and pictures were acquired with a side mount charge-coupled device camera (2600 × 4000 pixels; Orius 1000; Gatan, Inc.) and processed with Digital Micrograph Version 1.83.842 (Gatan, Inc.). For each experimental condition at least 65 replication fork molecules were analyzed with the ImageJ software.

DSB generation through CRISPR-Cas9

For the resection experiment in U-2OS-SEC, DSB2 sgRNAs were synthetized and purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and transfected using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Prior to sgRNA transfection, Cas9-eGFP expression was induced for 24 hours with 1μg/ml doxycycline.

Genomic DNA extraction

U-2OS-SEC (U-2OS-TetON-eGFP-Cas9) cells were harvested after sgRNA transfection and genomic DNA was extracted by Nucleospin™ Tissue Kit (Macherey-Nagel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The day after, a desired volume of genomic DNA was equally mock or digested with BamHI (New England BioLabs) for 4 h at 37°C. Digested and mock digested DNA was precipitated, purified and 5μl were used for each ddPCR reaction.

DNA end resection measurement by Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR)

The ddPCR reaction was assembled as previously described (Dibitetto et al., 2018). In brief, 5μl of genomic DNA, 1X ddPCR™ Supermix for Probes (no dUTP, Bio-Rad), 900nM for each pair of primers, 250nM for each probe, and dH2O to 20μl per sample. Droplets were produced pipetting 20μl of the PCR reaction mix into single wells of a universal DG8™ cartridge® for droplets generation (Bio-Rad). 70μl of droplet generation oil® was also added in each well next to the ones containing the samples. Cartridges were covered with DG8™ droplet generator gaskets (Bio-Rad) and then placed into the droplet generator (QX200™, Bio-Rad). After droplet generation, 40μl of emulsion were transferred from the cartridge to a 96-well ddPCR plate (Bio-Rad). Before PCR reaction, 96-well PCR plates were sealed with peelable foil heat seals at the PCR plate sealer machine (PX1™, Bio-Rad). For PCR reaction, Taq polymerase was activated at 95°C for 5’ and then 39 cycles of 95°C for 30” and 58.7°C for 1’ were made. At the end of the cycles, a 5 minute-step at 90°C was made and then temperature was held at 12°C. After the PCR, FAM and HEX fluorescence was read at the droplet reader (QX200™, Bio-Rad) using QuantaSoft™ software (Bio-Rad). For each sample the number of droplets generated were on an average of 15,000. The number of copies/μl of the target loci was determined setting an empirical baseline threshold identical in all the samples. For the measurement of ssDNA generated by the resection process (% ssDNA) we calculated the ratio (r’) between the number of copies of DSB2 locus (364bp from the Cas9 site) and a control locus on Chr. XXII with or without sgRNA digested or mock with BamHI restriction enzyme. The absolute percentage of ssDNA was then calculated with the following equation: % ssDNA= (r’digested/r’mock)+gRNA-(r’digested/r’mock)-gRNA.

Clonogenic survival assay

800 KB2P1.21, RPE1 and HCT116-derivative cells were seeded on 6cm or 10 cm Petri dishes in the presence of the indicated drugs and grown for 10–14 days. At the end of the experiment, plates were washed with PBS, fixed for 15’ with 3.7% Paraformaldehyde, and stained with Crystal Violet.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was done with the one-way ANOVA test and the two-tailed Student’s t-test using Prism (GraphPad Software). In all cases, n.s. indicates not significant, * (P<0.05), ** (P<0.01), *** (P<0.001), **** (P<0.0001). More details can be found in each figure legend.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

DNA-PKcs and KU associate with replication forks and promote fork reversal

DNA-PKcs promotes nascent strand degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells

DNA-PKcs prevents fork instability and replication-associated DNA damage

DNA-PKcs inhibition restores chemosensitivity in Brca2−/− cells

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Daniel Durocher for sharing RPE1 TP53−/− and RPE1 TP53−/−;BRCA1−/− cells. We thank Fenghua Hu for the access to the Fluorescent Microscope. We thank Beatriz Almeida and Denise Howald for technical assistance. We thank all the members of the Smolka, Rottenberg and Lopes lab for helpful discussions. D.D. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Fleming Research Foundation. M.B.S. was supported by NIH grants RO1-GM097272 and R35-GM141159. S.R. was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_179360), the European Union (ERC AdG-88387) and the Wilhelm Sander Foundation (no. 2019.069.1). A.S. and M.L. were supported by the SNF Project Grant 310030_189206.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Adamo A, Collis SJ, Adelman CA, Silva N, Horejsi Z, Ward JD, Martinez-Perez E, Boulton SJ, and La Volpe A (2010). Preventing Nonhomologous End Joining Suppresses DNA Repair Defects of Fanconi Anemia. Mol. Cell 39, 25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai G, Kermi C, Stoy H, Schiltz CJ, Bacal J, Zaino AM, Hadden MK, Eichman BF, Lopes M, and Cimprich KA (2020). HLTF Promotes Fork Reversal, Limiting Replication Stress Resistance and Preventing Multiple Mechanisms of Unrestrained DNA Synthesis. Mol. Cell 78, 1237–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.04.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmus G, Pilger D, Coates J, Demir M, Sczaniecka-Clift M, Barros AC, Woods M, Fu B, Yang F, Chen E, et al. (2019). ATM orchestrates the DNA-damage response to counter toxic non-homologous end-joining at broken replication forks. Nat. Commun 10, 1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barazas M, Gasparini A, Huang Y, Küçükosmanoglu A, Annunziato S, Bouwman P, Sol W, Kersbergen A, Proost N, De Korte-Grimmerink R, et al. (2019). Radiosensitivity is an acquired vulnerability of PARPI-resistant BRCA1-deficient tumors. Cancer Res. 79, 452–460. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti M, Chaudhuri AR, Thangavel S, Gomathinayagam S, Kenig S, Vujanovic M, Odreman F, Glatter T, Graziano S, Mendoza-Maldonado R, et al. (2013). Human RECQ1 promotes restart of replication forks reversed by DNA topoisomerase I inhibition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 20, 347–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti M, Cortez D, and Lopes M (2020). The plasticity of DNA replication forks in response to clinically relevant genotoxic stress. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 21, 633–651 (2020). doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-0257-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bétous R, Mason AC, Rambo RP, Bansbach CE, Badu-Nkansah A, Sirbu BM, Eichman BF, and Cortez D (2012). SMARCAL1 catalyzes fork regression and holliday junction migration to maintain genome stability during DNA replication. Genes Dev. 26, 151–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.178459.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting SF, Callén E, Wong N, Chen HT, Polato F, Gunn A, Bothmer A, Feldhahn N, Fernandez-Capetillo O, Cao L, et al. (2010). 53BP1 inhibits homologous recombination in brca1-deficient cells by blocking resection of DNA breaks. Cell 141, 243–254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BR, Quinet A, Byrum AK, Jackson J, Berti M, Thangavel S, Bredemeyer AL, Hindi I, Mosammaparast N, Tyler JK, et al. (2019). XLF and H2AX function in series to promote replication fork stability. J. Cell Biol 218, 2113–2123. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201808134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chen JY, Zhang X, Gu Y, Xiao R, Shao C, Tang P, Qian H, Luo D, Li H, et al. (2017). R-ChIP Using Inactive RNase H Reveals Dynamic Coupling of R-loops with Transcriptional Pausing at Gene Promoters. Mol. Cell 68, 745–757. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch FB, Bansbach CE, Driscoll R, Luzwick JW, Glick GG, Bétous R, Carroll CM, Jung SY, Qin J, Cimprich KA, et al. (2013). ATR phosphorylates SMARCAL1 to prevent replication fork collapse. Genes Dev. 27, 1610–1623. doi: 10.1101/gad.214080.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibitetto D, La Monica M, Ferrari M, Marini F & Pellicioli A (2018) Formation and nucleolytic processing of Cas9-induced DNA breaks in human cells quantified by droplet digital PCR. DNA Repair (Amst). 68, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dibitetto D, Sims JR, Ascencao CFR, Feng K, Kim D, Oberly S, Freire R, and Smolka MB (2020). Intrinsic ATR signaling shapes DNA end resection and suppresses toxic DNA-PKcs signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. Cancer 2, 1–14. doi: 10.1093/narcan/zcaa006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, Smith I, Tothova Z, Wilen C, Orchard R, et al. (2016). Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol 34, 184–191. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson BJ, Mansur DS, Peters NE, Ren H, and Smith GL (2012). DNA-PK is a DNA sensor for IRF-3-dependent innate immunity. Elife 2012, 1–17. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugger K, Mistrik M, Neelsen KJ, Yao Q, Zellweger R, Kousholt AN, Haahr P, Chu WK, Bartek J, Lopes M, et al. (2015). FBH1 catalyzes regression of stalled replication forks. Cell Rep. 10, 1749–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.02.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogola E, Rottenberg S, and Jonkers J (2019). Resistance to PARP Inhibitors: Lessons from preclinical models of BRCA-Associated Cancer. Annu. Rev. Cancer Biol 3, 235–254. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030617-050232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin JF, Kothari V, Drake JM, Zhao S, Dylgjeri E, Dean JL, Schiewer MJ, McNair C, Jones JK, Aytes A, et al. (2015). DNA-PKcs-Mediated Transcriptional Regulation Drives Prostate Cancer Progression and Metastasis. Cancer Cell 28, 97–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding SM, Benci JL, Irianto J, Discher DE, Minn AJ, and Greenberg RA (2017). Mitotic progression following DNA damage enables pattern recognition within micronuclei. Nature 548, 466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature23470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmink BA, and Sleckman BP (2012). The response to and repair of RAG-mediated DNA double-strand breaks. Annu. Rev. Immunol 30, 175–202. doi: 10.1146/annurevimmunol-030409-101320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, Boon U, Sol W, Van Deemter L, Zander SA, Drost R, Wientjens E, Ji J, Aly A, et al. (2013). Loss of 53BP1 causes PARP inhibitor resistance in BRCA1-mutated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Discov. 3, 68–81. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolinjivadi AM, Sannino V, De Antoni A, Zadorozhny K, Kilkenny M, Técher H, Baldi G, Shen R, Ciccia A, Pellegrini L, et al. (2017). Smarcal1-Mediated Fork Reversal Triggers Mre11-Dependent Degradation of Nascent DNA in the Absence of Brca2 and Stable Rad51 Nucleofilaments. Mol. Cell 67, 867–881. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanz MC, Dibitetto D, and Smolka MB (2019). DNA damage kinase signaling: checkpoint and repair at 30 years. EMBO J. 38(18):e101801. doi: 10.15252/embj.2019101801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaçon D, Jackson J, Quinet A, Brickner JR, Li S, Yazinski S, You Z, Ira G, Zou L, Mosammaparast N, et al. (2017). MRE11 and EXO1 nucleases degrade reversed forks and elicit MUS81-dependent fork rescue in BRCA2-deficient cells. Nat. Commun 8, 860. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01180-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H, Ji F, Helleday T, and Ying S (2018). Mechanisms for stalled replication fork stabilization: new targets for synthetic lethality strategies in cancer treatments. EMBO Rep. 19, 1–18. doi: 10.15252/embr.201846263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber MR (2010). The mechanism of double-strand DNA break repair by the nonhomologous DNA end-joining pathway. Annu. Rev. Biochem 79, 181–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptay M, Barbosa JS, Gogola E, Duarte AA, Dibitetto D, Schmid JA, Klebic I, Mutlu M, Siffert M, Francica P, et al. (2022). MDC1 counteracts restrained replication fork restart and its loss causes chemoresistance in BRCA1/2-deficient mammary tumors. Preprint at bioRxiv, 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.08.18.504391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Pannicke U, Schwarz K, and Lieber MR (2002). Hairpin opening and overhang processing by an Artemis/DNA-dependent protein kinase complex in nonhomologous end joining and V(D)J recombination. Cell 108, 781–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00671-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal A, and Zou L (2013). DNA damage sensing by the ATM and ATR kinases. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 5, 1–17. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mijic S, Zellweger R, Chappidi N, Berti M, Jacobs K, Mutreja K, Ursich S, Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A, Janscak P, et al. (2017). Replication fork reversal triggers fork degradation in BRCA2-defective cells. Nat. Commun 8, 1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01164-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutreja K, Krietsch J, Hess J, Ursich S, Berti M, Roessler FK, Zellweger R, Patra M, Gasser G, and Lopes M (2018). ATR-Mediated Global Fork Slowing and Reversal Assist Fork Traverse and Prevent Chromosomal Breakage at DNA Interstrand Cross-Links. Cell Rep. 24, 2629–2642. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.08.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Kustatscher G, Alabert C, Hödl M, Forne I, Völker-Albert M, Satpathy S, Beyer TE, Mailand N, Choudhary C, et al. (2021). Proteome dynamics at broken replication forks reveal a distinct ATM-directed repair response suppressing DNA double-strand break ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 81(5), 1084–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer SM, Adam S, Setiaputra D, Barazas M, Pettitt SJ, Ling AK, Olivieri M, Álvarez-Quilón A, Moatti N, Zimmermann M, et al. (2018). The shieldin complex mediates 53BP1-dependent DNA repair. Nature 560, 117–121. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0340-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AG, Sarkaria JN, and Kaufmann SH (2011). Nonhomologous end joining drives poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor lethality in homologous recombination-deficient cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 108, 3406–3411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013715108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinet A, Carvajal-Maldonado D, Lemacon D, and Vindigni A (2017). DNA Fiber Analysis: Mind the Gap! Methods in Enzymology 591, 55–82. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2017.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeyre C, Zellweger R, Chauvin M, Bec N, Larroque C, Lopes M, and Constantinou A (2016). Nascent DNA Proteomics Reveals a Chromatin Remodeler Required for Topoisomerase I Loading at Replication Forks. Cell Rep. 15, 300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg S, Disler C, and Perego P (2021). The rediscovery of platinum-based cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 37–50. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-00308-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S, Luzwick JW, and Schlacher K (2018). SIRF: Quantitative in situ analysis of protein interactions at DNA replication forks. J. Cell Biol 217(4), 1521–1536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201709121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. (2012). Fiji : an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9(7), 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher K, Christ N, Siaud N, Egashira A, Wu H, and Jasin M (2011). Double-strand break repair-independent role for BRCA2 in blocking stalled replication fork degradation by MRE11. Cell 145, 529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlacher K, Wu H, and Jasin M (2012). A Distinct Replication Fork Protection Pathway Connects Fanconi Anemia Tumor Suppressors to RAD51-BRCA1/2. Cancer Cell 22, 106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid JA, Berti M, Walser F, Raso MC, Schmid F, Krietsch J, Stoy H, Zwicky K, Ursich S, Freire R, et al. (2018). Histone Ubiquitination by the DNA Damage Response Is Required for Efficient DNA Replication in Unperturbed S Phase. Mol. Cell 71, 897–910. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z, Flynn RA, Crowe JL, Zhu Y, Liang J, Jiang W, Aryan F, Aoude P, Bertozzi CR, Estes VM, et al. (2020). DNA-PKcs has KU-dependent function in rRNA processing and haematopoiesis. Nature 579, 291–296. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2041-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taglialatela A, Alvarez S, Leuzzi G, Sannino V, Ranjha L, Huang JW, Madubata C, Anand R, Levy B, Rabadan R, et al. (2017). Restoration of Replication Fork Stability in BRCA1- and BRCA2-Deficient Cells by Inactivation of SNF2-Family Fork Remodelers. Mol. Cell 68, 414–430. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira-Silva A, Ait Saada A, Hardy J, Iraqui I, Nocente MC, Fréon K, and Lambert SAE (2017). The end-joining factor Ku acts in the end-resection of double strand break-free arrested replication forks. Nat. Commun 8(1): 1982. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02144-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Eychenié S, Décaillet C, Basbous J, and Constantinou A (2013). DNA structure-specific priming of ATR activation by DNA-PKcs. J. Cell Biol 202, 421–429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201304139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic M, Krietsch J, Raso MC, Terraneo N, Zellweger R, Schmid JA, Taglialatela A, Huang JW, Holland CL, Zwicky K, et al. (2017). Replication Fork Slowing and Reversal upon DNA Damage Require PCNA Polyubiquitination and ZRANB3 DNA Translocase Activity. Mol. Cell 67, 882–890. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel SR, Mohni KN, Luzwick JW, Dungrawala H, and Cortez D (2019). Functional Analysis of the Replication Fork Proteome Identifies BET Proteins as PCNA Regulators. Cell Rep. 28, 3497–3509. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying S, Chen Z, Medhurst AL, Neal JA, Bao Z, Mortusewicz O, McGouran J, Song X, Shen H, Hamdy FC, et al. (2016). DNA-PKcs and PARP1 bind to unresected stalled DNA replication forks where they recruit XRCC1 to mediate repair. Cancer Res. 76, 1078–1088. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellweger R, Dalcher D, Mutreja K, Berti M, Schmid JA, Herrador R, Vindigni A, and Lopes M (2015). Rad51-mediated replication fork reversal is a global response to genotoxic treatments in human cells. J. Cell Biol 208, 563–579. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M, Murina O, Reijns MAM, Agathanggelou A, Challis R, Tarnauskaite Ž, Muir M, Fluteau A, Aregger M, McEwan A, et al. (2018). CRISPR screens identify genomic ribonucleotides as a source of PARP-trapping lesions. Nature 559, 285–289. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0291-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is available in the main text, supplemental materials, or via Mendeley at https://doi:10.17632/n3r6jsmryr.1

The paper does not report any original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.