Abstract

A surface immunofluorescence assay (SIFA) using live spirochetes was analyzed and compared with Western blot (WB), fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), microhemagglutination (MHA-TP), and Treponema pallidum immobilization (TPI) assays for detecting serum antibodies to T. pallidum in patients with syphilis, in disease controls, and in healthy subjects. SIFA and WB were 99% sensitive (99 of 100 positive specimens) and specific (140 of 140 negative specimens); FTA-ABS showed a sensitivity and a specificity of 90 and 89% (90 of 100 positive and 125 of 140 negative specimens), respectively. MHA-TP showed a sensitivity of 84% (84 of 100 positive specimens) and a specificity of 98.5% (138 of 140 negative specimens). Finally, TPI had a sensitivity of 52% (52 of 100 positive specimens) and a specificity of 100% (140 of 140 negative specimens). The T. pallidum SIFA was therefore highly specific, showing no equivocal reactivities with control sera, and sensitive. The results suggest the possible use of SIFA as a confirmatory test in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis.

The diagnosis of syphilis depends on clinical findings, examination of lesions for treponemes, and/or serologic tests. Serologic tests are divided into nontreponemal and treponemal tests. Nontreponemal tests are useful for screening, while treponemal tests are used as confirmatory tests. In practice, two or three assays are performed in series for the serologic diagnosis of syphilis (22, 28). First, sera are screened in a microflocculation assay, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test (VDRL), using nontreponemal antigens (25). Reactive sera are then tested for antibodies specific for Treponema pallidum antigens by using the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay (FTA-ABS) or the microhemagglutination assay (MHA-TP) (12, 22, 28). Since the mid-1980s, the Western blot assay (WB), set up with boiled sodium dodecyl sulfate extracts of T. pallidum, has been introduced as an alternative to the other confirmatory methods (5, 13, 15). In addition, among the treponemal tests, several enzyme immunoassays have been described and evaluated, showing sensitivities and specificities similar to those of FTA-ABS and MHA-TP (9, 11, 23, 37).

Currently, the T. pallidum immobilization test (TPI), the first treponemal antibody test developed (by Nelson and Mayer in 1949 [26]), is limited to mostly research purposes, since it is complex and technically difficult. The test is based on the ability of the patient's antibody to bind to the surface of T. pallidum (2) and to immobilize living spirochetes in the presence of complement, as observed by dark-field microscopy. TPI is accepted as a specific test for syphilis, though it is less sensitive than the newer treponemal tests (30).

Previous observations from our laboratory showed the high specificity of surface immunofluorescence assay (SIFA) performed with live Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes for the detection of serum-specific antibodies against surface antigens of the Lyme disease agent (7). In this study, we investigated the sensitivity and specificity of SIFA both for the detection of specific antibodies against T. pallidum and for the serologic diagnosis of syphilis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study groups.

One hundred patients (74 males and 26 females) between 21 and 68 years of age (mean age, 37.2 years) suffering from syphilis were studied. The diagnosis, based on clinical and laboratory data, was early syphilis for 46 patients (i.e., primary syphilis for 26 patients and secondary syphilis for 20 patients), early latent syphilis for 50 patients, and late syphilis for 4 patients. Sixteen patients with primary syphilis and three with secondary syphilis were human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive.

The stage classification of syphilis was made by following the guidelines proposed by Norris and Larsen (28). One serum sample, obtained at the time of the clinical diagnosis, was used for serologic study. Fifty sera from healthy blood donors, 20 sera from patients suffering from Lyme disease (16) previously serologically characterized in our laboratory, and 20 sera from patients suffering from leptospirosis (obtained from M. S. Nuncio, Instituto Nacional de Saude, Aguas De Moura, Portugal) were studied as controls and disease controls, respectively. In addition, 50 serum samples positive by VDRL and negative by MHA-TP, WB, and TPI were also included in the study. These sera were defined as biological false-positive (BFP) reactors (3, 4, 14, 18, 31), since they were from subjects without clinical signs or symptoms of syphilis, i.e., 10 healthy, pregnant women, 15 patients suffering from dermatological diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematosus or chicken pox), 15 patients with HIV infection, 5 patients with viral hepatitis showing autoimmune reactions, and 5 patients with diabetes mellitus.

Source of T. pallidum.

Treponema pallidum subsp. pallidum (Nichols strain), originally purchased from the Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark, was maintained in adult male New Zealand White rabbits by testicular passage (24). Infected rabbits were individually housed, maintained at 16 to 18°C, and given antibiotic-free food and water ad libitum. Each treponemal suspension was prepared from infected rabbit testicles from 10 to 14 days after inoculation (24).

VDRL.

A commercial kit was used by following the manufacturer's instructions (Behring AG, Marburgan der Lahn, Germany). The results were read under light microscopy at a ×100 magnification.

FTA-ABS.

Serum samples were tested by a fluorescent T. pallidum-specific assay (Trepo Spot IF, BioMerieux SA, Marcy l'Etoile, France) by using microscope slides coated with T. pallidum (Nichols strain) whole antigen. Sera were preliminarily screened by following the plus (+) score system proposed by the manufacturer. Afterwards, all the samples scored as 1+ were retested by using serial twofold dilutions starting from 1/5 up to 1/40. Since the 1+ sera were positive at a dilution of <1:20, they were considered negative according to the previously reported data of Larsen and coworkers (21). The specimens scoring above the 1+ level were retested by diluting samples from 1:10 up to 1:640. A reaction was considered positive when at least 80% of the spirochetes gave a brilliant green fluorescence at a serum dilution of ≥1:20.

MHA-TP.

Quantitative MHA-TP testing (MHA-TP, Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan) was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, which had an established cutoff of a 1:80 dilution.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and WB.

Treponemal suspensions obtained from infected rabbit testicles were diluted in sample buffer to 109 organisms per ml, as determined by dark-field microscopy examination at a magnification of ×400. The separation of T. pallidum polypeptides was performed with a Laemmli buffer system (19) by using a 12% acrylamide gel as described elsewhere (6). The WB procedure of Towbin et al. (35) was performed as described elsewhere (6). After electrophoretic transfer, the blots were incubated for 12 h at room temperature with sera diluted 1:100 in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20. Antigen-antibody complexes were detected with peroxidase-labeled rabbit antiserum to total human immunoglobulin (Ig) (Dako, Copenhagen, Denmark) diluted 1:500 in phosphate-buffered saline and with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) as the enzyme substrate.

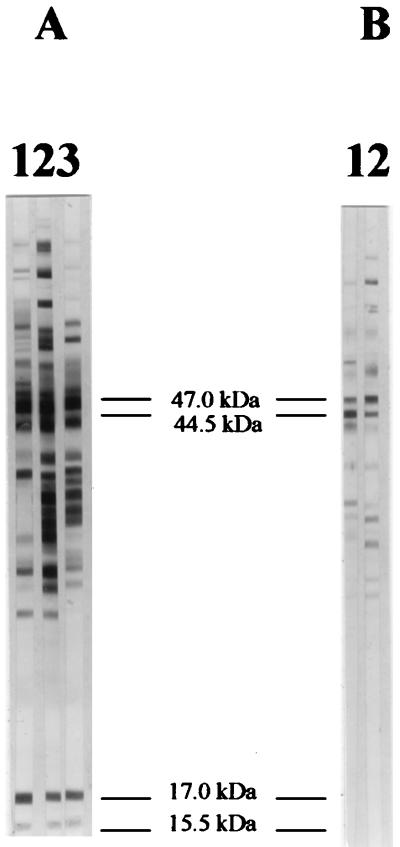

A test was considered positive when at least three of four T. pallidum specific bands with apparent molecular masses of 15.5, 17, 44.5, and 47 kDa were present (5, 27). A test was considered negative when no band or fewer than three of the above-mentioned T. pallidum antigens were recognized (5). The apparent molecular weight of each band was determined by comparative plotting of the positions of Rainbow low-molecular-weight standards (Amersham-Pharmacia, Amersham, United Kingdom). Positive and negative control sera were run with test specimens. The positive control was prepared by pooling 20 different sera from patients suffering from syphilis at different stages: each individual serum sample was positive by both WB and MHA-TP (titer range, 640 to 5,120) as well as the serum pool that was positive by WB and MHA-TP (titer = 1,280). As a negative control, a serum pool of 20 samples from healthy blood donors was used. This serum pool was negative by both MHA-TP (titer < 80) and WB.

TPI.

TPI was performed by following the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (36). Briefly, treponemes were extracted from rabbit testis in basal medium (36) under anaerobic conditions and were incubated with serum samples (with or without added complement) in anaerobic jars at 35°C for 16 to 18 h. All sera were tested in duplicate to ensure the validity of the procedure. A test was considered negative if the difference between the average number of motile treponemes, determined by dark-field microscopy (magnification, ×400), of the two “test” tubes and the “control” tube (i.e., the tube without complement added) was 20% or less. A test was considered positive if the difference between the average count of motile spirochetes in the two test tubes and the control tube was 50% or greater. In order to be validated, in the control tube at least 70% active motile treponemes had to be read. Specimens were always tested in a blind fashion.

SIFA.

Serum samples were tested by SIFA as previously reported (7, 32), with slight modifications. Sera were inactivated at 56°C for 1 h, diluted 1:20 in a suspension of 100% motile treponemes extracted from infected rabbit testicles (108 bacteria/ml) in the medium described by Stamm and Bassford (34), and incubated under an atmosphere of 95% N2–5% CO2 at 37°C for 1 h. After the incubation period, the viability of treponemes was checked again by dark-field microscopy. In order to validate the test, at least 99% of treponemes had to be motile. The suspension was then pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 min, and washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline. The treponemes were diluted to a final concentration of 107 bacteria/ml, spotted (10 μl) onto microscope slides, air dried, and fixed with cold acetone for 10 min. Igs bound to T. pallidum surface-exposed antigens were detected by using fluorescein-conjugated rabbit anti-human total Ig (Dako), diluted 1:40 in phosphate-buffered saline. The results were read under UV light microscopy at a magnification of ×400.

RESULTS

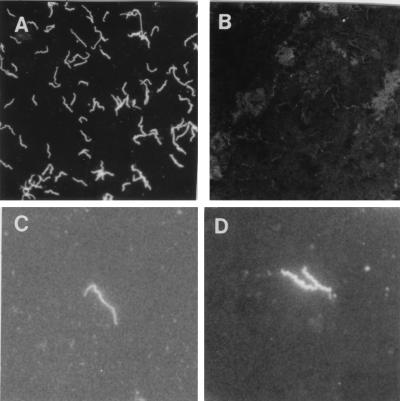

Antibodies against T. pallidum surface-exposed antigens were easily detectable in sera from syphilitic patients by SIFA. Positive sera induced a bright fluorescence of treponemes that appeared slightly more slender than bacteria stained by FTA-ABS (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Photomicrograph of T. pallidum stained by SIFA. Living spirochetes were incubated with T. pallidum-positive (A) and -negative (B) human serum samples. Magnification, ×320. (C and D) T. pallidum stained by SIFA and by FTA-ABS, respectively, at a higher magnification (×800). The spirochetes stained by SIFA appear slightly more slender than those stained by FTA-ABS.

The results obtained in the various stages of syphilitic infection by SIFA are reported in Table 1 and compared with the results obtained by the other serologic methods. SIFA, WB (Fig. 2), and VDRL were the most sensitive methods in the early stage of syphilis, since 45 out of 46 serum samples were positive by these methods; the serum sample negative by these tests was from a patient showing a chancre lesion from which treponemes were identified by dark-field microscopy. It is interesting that 6 out of 16 HIV-infected patients with primary syphilis and 1 out of 3 HIV-infected patients with secondary syphilis were positive by SIFA, WB, and VDRL but negative by FTA-ABS and MHA-TP. All (n = 50) serum samples from patients with early latent syphilis were positive by SIFA, WB, FTA-ABS, and VDRL, whereas 92% (46 of 50) and 72% (36 of 50) of the sera were positive by MHA-TP and TPI, respectively. Late-syphilis sera were positive by all the tests. Tables 2 to 5 report the comparison of results obtained by SIFA with results obtained by the other treponemal tests (WB, FTA-ABS, MHA-TP, and TPI) in testing specimens from syphilis patients, healthy donors, Lyme disease patients, and leptospirosis patients and in testing BFP samples. The sensitivity and specificity of SIFA and of the other methods were as follows. SIFA and WB were 99% sensitive (99 of 100 positive specimens) and specific (140 of 140 negative specimens, including 50 BFP reactors, 50 healthy blood donors' samples, 20 samples of patients with Lyme disease, and 20 samples of patients suffering from leptospirosis). FTA-ABS showed a sensitivity and a specificity of 90 and 89%, respectively (90 of 100 positive and 125 of 140 negative specimens). MHA-TP showed a sensitivity of 84% (84 of 100 positive specimens) and a specificity of 98.5% (138 of 140 negative specimens). Finally, TPI showed a sensitivity of 52% (52 of 100 positive specimens) and a specificity of 100% (140 of 140 negative specimens).

TABLE 1.

Results obtained by T. pallidum SIFA, WB, FTA-ABS, MHA-TP, TPI, and VDRL in serum samples from patients with syphilis

| Stage of syphilis | No. of samples | No. with serologic test result (% positive)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIFA | WB | FTA-ABS | MHA-TP | TPI | VDRL | ||

| Primary | 26 | 25 (96) | 25 (96) | 17 (65) | 17 (65) | 0 | 25 (96) |

| Secondary | 20 | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 19 (95) | 17 (85) | 12 (60) | 20 (100) |

| Early latent | 50 | 50 (100) | 50 (100) | 50 (100) | 46 (92) | 36 (72) | 50 (100) |

| Late | 4 | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | 4 (100) |

FIG. 2.

WB analysis of human sera with T. pallidum whole-cell preparation. (A) Sample from a positive serum pool (lane 1) and two serum samples from patients with early latent syphilis (lanes 2 and 3). These samples clearly recognized four T. pallidum bands of 15.5, 17.0, 44.5, and 47.0 kDa. These bands are considered diagnostic for T. pallidum infection when at least three of them are detected (5, 27). (B) Lanes 1 and 2 were probed with two sera defined as BFP reactors since they were positive by VDRL but negative by MHA-TP and TPI. Also, WB was negative since the sera recognized only two of the four above-mentioned T. pallidum bands (the 47.0- and 44.5-kDa bands). The apparent molecular masses of individual T. pallidum proteins are shown in the middle.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of FTA-ABS and SIFA reactivities in sera from patients with syphilis, in sera defined as BFP reactors, in sera from healthy blood donors, and in sera from patients with Lyme disease or leptospirosis

| Specimen source or type | No. tested | No. of specimens showing the following FTA-ABS and SIFA results, respectively

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | + and − | − and + | − and − | |||

| Syphilis patients | 100 | 90 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 91 |

| BFP reactor | 50 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 37 | 74 |

| Blood donors | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Lyme disease patients | 20 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 18 | 90 |

| Leptospirosis patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

TABLE 5.

Comparison of TPI and SIFA reactivities in sera from patients with syphilis, in sera defined as BFP reactors, in sera from healthy blood donors, and in sera from patients with Lyme disease or leptospirosis

| Specimen source or type | No. tested | No. of specimens showing the following TPI and SIFA results, respectively

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | + and − | − and + | − and − | |||

| Syphilis patients | 100 | 52 | 0 | 47 | 1 | 53 |

| BFP reactor | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Blood donors | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Lyme disease patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

| Leptospirosis patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

DISCUSSION

The reliability of immunological reactions between antibodies and surface-exposed antigens of the spirochete B. burgdorferi that are caused by using living organisms and SIFA has been previously shown by members of our group (7) and subsequently confirmed by Cox et al. (8). In this study, we compared SIFA for the detection of antibodies against T. pallidum with other treponemal serologic tests. The sensitivity of SIFA and WB was 99%; in contrast, FTA-ABS and MHA-TP were less sensitive, with values of 90 and 84%, respectively. In fact, FTA-ABS and MHA-TP failed to recognize antitreponemal antibodies in 7 out of 19 specimens from HIV-infected patients suffering from primary or secondary syphilis, in contrast with SIFA, WB, and VDRL. The reliability of syphilis serology in patients with HIV infection has been questioned (10, 17, 33), and the need for a good test for this group of patients is well known, because of the false-negative results that can be obtained by using the classic treponemal serologic methods. TPI was the least sensitive method, showing a sensitivity of 52%, in agreement with previous reported data (30). The specificity of SIFA was analyzed by testing sera from several control groups. None of these sera was found to be reactive by SIFA (specificity, 100%). Similar results were obtained by WB and TPI. MHA-TP showed high specificity (98.5%), whereas FTA-ABS was less specific (89%), since several BFP samples and sera from patients with Lyme disease gave false-positive reactions. These data are in agreement with those reported by other authors (3, 4, 14, 18, 20).

When the SIFA-positive sera were tested by WB, all of them clearly recognized at least three out of the four T. pallidum bands with apparent molecular masses of 15.5, 17.0, 44.5, and 47.0 kDa, which are considered diagnostic for T. pallidum infection (5, 27). In addition, the sera recognized several other variable bands. It is known that none of the four T. pallidum bands considered diagnostic for T. pallidum infection is surface exposed (1, 27). Therefore, the antibodies reactive in SIFA were not those involved in the recognition of these T. pallidum antigens by WB. On the other hand, it is unlikely that the rare outer membrane proteins of T. pallidum described by Blanco et al. (1) and by Radolf et al. (29) could be reliably identified by WB, at least under our experimental conditions, due to their scanty representation on the bacterial surface (1, 29). In fact, it has been shown that T. pallidum surface proteins can be reliably detected by WB only by using enriched outer membrane protein preparations (1, 29). Notwithstanding this, the specificity of SIFA was demonstrated in our study by comparing the T. pallidum SIFA results with T. pallidum WB results obtained in detecting other diagnostic, albeit not surface-exposed, T. pallidum proteins.

In conclusion, the results obtained in the present study demonstrate that antibodies reactive with the surface-exposed antigens of live T. pallidum organisms are highly specific for syphilitic infection, showing no equivocal reactivities with the various control sera used. This observation confirms previous data regarding the specificity of antibodies reactive with the surface antigens of the spirochete B. burgdorferi in patients suffering from Lyme disease (7). In contrast with B. burgdorferi SIFA, which proved sensitive only for late Lyme disease (7), the T. pallidum SIFA was highly sensitive for both early and late syphilis. These results therefore suggest the possibility of using the T. pallidum SIFA as a confirmatory test in the serologic diagnosis of syphilis.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of MHA-TP and SIFA reactivities in sera from patients with syphilis, in sera defined as BFP reactors, in sera from healthy blood donors, and in sera from patients with Lyme disease or leptospirosis

| Specimen source or type | No. tested | No. of specimens showing the following MHA-TP and SIFA results, respectively

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | + and − | − and + | − and − | |||

| Syphilis patients | 100 | 84 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 85 |

| BFP reactor | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Blood donors | 50 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 49 | 98 |

| Lyme disease patients | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 19 | 95 |

| Leptospirosis patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

TABLE 4.

Comparison of WB and SIFA reactivities in sera from patients with syphilis, in sera defined as BFP reactors, in sera from healthy blood donors, and in sera from patients with Lyme disease or leptospirosis

| Specimen source or type | No. tested | No. of specimens showing the following WB and SIFA results, respectively

|

% Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + and + | + and − | − and + | − and − | |||

| Syphilis patients | 100 | 99 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 100 |

| BFP reactor | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Blood donors | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 100 |

| Lyme disease patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

| Leptospirosis patients | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 100 |

REFERENCES

- 1.Blanco D R, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Surface antigens of the syphilis spirochete and their potential as virulence determinants. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:11–20. doi: 10.3201/eid0301.970102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanco D R, Walker E M, Haake D A, Champion C I, Miller J N, Lovett M A. Complement activation limits the rate of in vitro treponemicidal activity and correlates with antibody-mediated aggregation of Treponema pallidum rare outer membrane protein. J Immunol. 1990;144:1914–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brauner A, Carlsson B, Sundkvist G, Ostenson C G. False-positive treponemal serology in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complicat. 1994;8:57–62. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(94)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchanan C S, Haserick J R. FTA-ABS test in pregnancy: a probable false-positive reaction. Arch Dermatol. 1970;102:333–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrne R E, Laska S, Bell M, Larson D, Phillips J, Todd J. Evaluation of a Treponema pallidum Western immunoblot assay as a confirmatory test for syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:115–122. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.1.115-122.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cevenini R, Rumpianesi F, Sambri V, La Placa M. Antigenic specificity of serological response in Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis detected by immunoblotting. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:335–337. doi: 10.1136/jcp.39.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cevenini R, Sambri V, Massaria F, Franchini R, D'Antuono A, Borda G, Negosanti M. Surface immunofluorescence assay for diagnosis of Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2456–2461. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2456-2461.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox D L, Akins D R, Bourell K W, Lahdenne P, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Limited surface exposure of Borrelia burgdorferi outer surface lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7973–7978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebel A, Bachelart L, Alonso J-M. Evaluation of a new competitive immunoassay (BioElisa Syphilis) for screening for Treponema pallidum antibodies at various stages of syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:358–361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.358-361.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erbelding E J, Vlahov D, Nelson K E, Rompalo A M, Cohn S, Sanchez P, Quinn T C, Brathwaite W, Thomas D L. Syphilis serology in human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for false-negative fluorescent treponemal testing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1397–1400. doi: 10.1086/517330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farshy C E, Hunter E F, Helsel L O, Larsen S A. Four-step enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detection of Treponema pallidum antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:387–389. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.3.387-389.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farshy C E, Hunter E F, Pope V, Larsen S A, Feeley J C. Four serologic tests for syphilis: results with comparison of selected groups of sera. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:228–231. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.George R W, Pope V, Larsen S A. Use of the Western blot for the diagnosis of syphilis. Clin Immunol Newsl. 1991;8:124–133. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibowski M, Neumann E. Non-specific positive test results to syphilis in dermatological diseases. Br J Vener Dis. 1980;56:17–19. doi: 10.1136/sti.56.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hensel U, Wellensiek H-J, Bhakdi S. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis immunoblotting as a serological tool in the diagnosis of syphilitic infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:82–87. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.1.82-87.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter E F, Russell H, Farshy C E, Sampson J S, Larsen S A. Evaluation of sera from patients with Lyme disease in the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test for syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:233–236. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson P D R, Graves S R, Stewart L, Warren R, Dwyer B, Lucas C R. Specific syphilis serological tests may become negative in HIV infection. AIDS. 1991;5:419–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199104000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus S J, Haserick J R, Lantz M. Fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test reactions in lupus erythematosus. Atypical beading pattern and probable false-positive reactions. N Engl J Med. 1970;333:1247–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197006042822303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsen S A, Hambie E A, Pettit D E, Perryman M W, Kraus S J. Specificity, sensitivity, and reproducibility among the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption test, the microhemagglutination assay for Treponema pallidum antibodies, and the hemagglutination treponemal test for syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:441–445. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.4.441-445.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larsen S A, Farshy C E, Pender B J, Adams M R, Pettit D E, Hambie E A. Staining intensities in the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorption (FTA-Abs) test: association with the diagnosis of syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 1986;13:221–227. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larsen S A, Steiner B M, Rudolph A H. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:1–21. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lefevre J-C, Bertrand M-A, Bauriaud R. Evaluation of the Captia enzyme immunoassays for detection of immunoglobulins G and M to Treponema pallidum in syphilis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1704–1707. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.8.1704-1707.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J N, Whang S J, Fazzan F P. Studies on immunity in experimental syphilis. Treponema pallidum immobilization (TPI) antibody and the immune response. Br J Vener Dis. 1963;39:199–203. doi: 10.1136/sti.39.3.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Musher D. Biology of T. pallidum. In: Holmes K K, Mardh P, Spardling P F, et al., editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill; 1990. pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson R A, Jr, Mayer M M. Immobilization of Treponema pallidum in vitro by antibody produced in syphilitic infection. J Exp Med. 1949;89:369–393. doi: 10.1084/jem.89.4.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norris S J the Treponema pallidum Polypeptide Research Group. Polypeptides of Treponema pallidum: progress toward understanding their structural, functional, and immunologic roles. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:750–779. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.3.750-779.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norris S J, Larsen S A. Treponema and other host-associated spirochetes. In: Murray P R, Baron E J, Pfaller M A, Tenover F C, Yolken R H, editors. Manual of clinical microbiology. 6th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 636–651. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radolf J D, Robinson E J, Bourell K W, Akins D R, Porcella S F, Weigel L M, Jones J D, Norgard M V. Characterization of outer membranes isolated from Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4244–4252. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4244-4252.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rein M F, Banks G W, Logan L C, Larsen S A, Feeley J C, Kellog D S, Wiesner P J. Failure of the Treponema pallidum immobilization test to provide additional diagnostic information about contemporary problem sera. Sex Transm Dis. 1980;7:101–105. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198007000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rompalo A M, Cannon R O, Quinn T C, Hook E W. Association of biological false-positive reactions for syphilis with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:1124–1126. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sambri V, Marangoni A, Massaria F, Farencena A, LaPlaca M, Jr, Cevenini R. Functional activities of antibodies directed against surface lipoproteins of Borrelia hermsii. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39:623–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjovall P. HIV infection and loss of treponemal test reactivity. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 1991;71:458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stamm L V, Bassford P J., Jr Cellular and extracellular protein antigens of Treponema pallidum synthesized during in vitro incubation of freshly extracted organisms. Infect Immun. 1985;47:799–807. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.799-807.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Serologic tests for syphilis. Atlanta, Ga: Communicable Disease Center, Venereal Disease Branch, Public Health Service; 1964. pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young H, Moyes A, Ross J D. Markers of past syphilis in HIV infection comparing Captia Syphilis G anti-treponemal IgG enzyme immunoassay with other treponemal antigen tests. Int J STD AIDS. 1995;6:101–104. doi: 10.1177/095646249500600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]