Abstract

Background/purpose

There is controversial evidence on the best choice for root-end filling materials in follow-up periods and treatment protocols. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of different root-end filling materials in modern surgical endodontic treatment.

Materials and methods

A total of 16 studies with a minimum follow-up of 12-months were qualified to be reviewed, involving randomized control trials and observational studies in PubMed, Cochrane library and Scopus until September 1, 2021. The outcome of modern surgical endodontic treatment was assessed based on clinical and radiographic success. Direct comparisons were combined to estimate indirect comparisons, and the estimated effect size was analyzed using the odds ratio (OR). The comparative effectiveness of all materials for target outcomes were shown as P-score.

Results

Within this network meta-analysis, mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) had superior effects among all root-end filling materials at 12-months follow-up. (MTA: OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.84–4.91; P-score, 0.86; reference material, gutta-percha). In further sensitivity analyses, MTA, calcium silicate-based root repair material (RRM) and super EBA cement (Super EBA) were associated with significantly higher success rates at 12-months follow-up. (MTA: OR, 5.62; 95% CI, 1.58–19.99; P-score, 0.88; RRM: OR, 5.23; 95% CI, 1.05–25.98; P-score, 0.74; Super EBA: OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.06–15.04; P-score, 0.54; reference material, gutta-percha).

Conclusion

MTA remains the best choice for root-end filling materials of modern surgical endodontic treatment at the 12-month follow-up. Comparative randomized clinical trials in the long-term follow-up are warranted in future investigations.

Keywords: Endodontic surgery, Evidence-based dentistry, Meta-analysis, Root-end filling materials

Introduction

Teeth with post-treatment apical periodontitis can be managed by either nonsurgical endodontic retreatment or surgical approach; Surgical endodontic treatment may be indicated when a nonsurgical retreatment is less likely to improve the previous results.1

In the procedures involving surgical endodontic treatment, the traditional techniques have been performed with beveled root resection, using a straight surgical handpiece performed only root-end resection or utilized amalgam as the root-end filling material.1, 2, 3 In contrast, modern techniques which incorporate the use of magnification devices, root-end resection with minimal or no bevel, retrograde cavity preparation with ultrasonic/sonic tips and root-end filling with more biocompatible materials, are proved to provide higher success rates when compared to traditional techniques.1,2,4

The placement of root-end fillings is one of the key steps in managing the root end, providing a hermetic physical seal, and in this way to prevent the egress of microorganisms or their by-products from the root canal system into the peri-radicular tissue.5 Peri-radicular curettage alone, without root-end fillings, does not eliminate the cause of leakage.2 Many studies had analyzed the clinical outcome of surgical endodontic treatment, and most of them implied that the choice of root-end filling materials is a prognostic factor for clinical outcome of endodontic surgery.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

As new materials roll out, several studies have also compared the clinical outcome of surgical endodontic treatment using different root-end filling materials. However, the previous systematic reviews and meta-analysis often compared the pooled percentages of success between studies,9,11 so that the heterogeneity of study designs, follow-up periods and treatment protocols between the included articles may affect the statistical results. Tang et al. had reported a systematic review of the literature addressing the outcomes of mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) in endodontic surgery, which showed its superiority compared with gutta-percha (GP) and amalgam but not intermediate restorative material (IRM).14 Another article published by Ma et al. and the recently updated article by Li et al. included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) which compared different root-end filling materials, but there was a paucity of the comparison between different materials under the same surgical protocol.15,16 As a result, there is still limited evidence on the best material for root-end fillings.

Because the methodological heterogeneity is inevitable between the included articles, the aim of this study is to evaluate the efficacy outcome of different root-end filling materials used in modern surgical endodontic treatment, with the aid of network meta-analysis (NMA).

Material and methods

Current network meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension guidelines for Network Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-NMA)17,18 and Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (Table S1.1 and Table S1.2).19 Registered protocol was available in the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/w8vbn).

Data sources and search strategy

A systematic publication review was conducted and retrieved from PubMed, Scopus, and Cochrane library from inception to November 1, 2021, using the following keywords comprised of “root-end filling material,” “retrograde filling material,” and “surgical endodontic treatment,” along with a list of all interventions and possibly relevant terms (Table S2). Gray literature and manual searches were performed for potentially eligible articles from the reference lists of review articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Targets of this systematic review and network meta-analysis were clinical studies that reported the outcome of modern surgical endodontic treatment in patients with persistent periapical periodontitis using different root-end filling materials. The inclusion criteria were following:

-

1.

Randomized controlled trials (RCT) and observational cohort studies (CS) were included in the study design.

-

2.

With the aid of magnification, endodontic surgery by modern technique was consisted of local anesthesia, a full mucoperiosteal flap elevation, osteotomy, curettage of soft tissues adjacent to the root, root-end resection with minimal or no bevel, retrograde cavity preparation to a 3–4 mm depth by ultrasonic/sonic tips.1,2,4

-

3.

Outcome of endodontic surgery is evaluated by clinical and radiographic results following criteria described by Rud et al., Molven et al., Gutmann and Harrison.20, 21, 22

-

4.

The comparison included two or more different root-end filling materials or compared with placebo (smoothing resection root surface without placing root-end fillings).

-

5.

Studies reporting the relationship between root-end filling materials and the outcomes of interest were evaluated at least one-year follow-up.

The exclusion criteria and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded in network meta-analysis:

-

1.

In vitro or ex vivo studies, case reports, review articles or expert opinions.

-

2.

Outcome assessments were less than one-year follow-up.

-

3.

The outcome assessment was not according to the criteria described by Rud et al., Molven et al., Gutmann and Harrison.

-

4.

Without comparators for root-end fillings.

-

5.

Surgical endodontic treatment protocols were inconsistent, performed without applying the modern technique.

-

6.

Those in which interested outcomes were not reported

Data extraction and bias assessment

Two authors (YC Chao and HJ Jhou) independently selected trials that met the inclusion criteria, and extracted the relevant data from the manuscripts, among the included studies. In cases of discrepancy, a third author (PH Chen) was consulted to achieve decisions after a deliberate group discussion. Study information regarding studies, participants, and treatment characteristics was obtained. If available data are lacking, corresponding authors were contacted for data collection.

Risk of bias (ROB) was performed by two authors (YC Chao and HJ Jhou) according to the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for the assessment of nonrandomized studies for meta-analysis (Table S3).23 The Cochrane risk of bias tool was used for randomized control studies.24 Any disagreement among the reviewers was resolved by a third author (PH Chen).

Outcome definition

We extracted outcomes for the success rates between each treatment regimen in 12-months period, and long-term period (defined as following time more than 24-months). Outcome of endodontic surgery is evaluated by combined clinical and radiographic results. Regardless of radiographic evaluation, presenting clinical symptoms such as pain and/or swelling, tenderness to percussion or palpation, or sinus tract were classified as failure, by contrast, incomplete healing and complete healing cases were classified as success (Table S4).

Statistical analysis

The symmetry and geometry of the evidence were examined by producing a network plot with nodes for the number of study participants and connection sizes corresponding to the number of studies.25 The pooled odds ratio (OR) with 95% CIs was calculated for dichotomous variables. Because of the presumed heterogeneity among the included studies, with regards to either the sample source or intervention approaches, we used a random effects model in meta-analysis and frequentist models in the NMA to compare the effect sizes between studies with the different materials.26 All comparisons were set as two-tailed, and a P-value statistically significant cutoff point was set at 0.05.

To provide a more relevant clinical application, each material was sorted based on their comparative effectiveness and we calculated the relative ranking probabilities between the treatment effects of all materials for the target outcomes. In the frequentist NMA, a P-score was adopted from the concept of the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), defined as the percentage of the mean rank of each material relative to an imaginary intervention that was the best.27 When the P-score was larger, the material had a higher rank with regards to the success rate.28

Forest plots represented the summary of these results within the NMA, including the relative mean effects, 95% CIs, and P-scores for all interventions.29 We evaluated potential inconsistencies between the direct and indirect effects within the NMA by design-by-treatment interaction model for global inconsistency and node-splitting technique for local inconsistency.30,31 Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05 for both analyses. Network transitivity was evaluated by visually inspecting the tables with study association characteristics that may influence the treatment effects, such as the differences in the characteristics of enrolled patients, study designs, interventions, and outcome measurements.32 Sensitivity analyses were performed by excluding high risk-of-bias studies and based on different types of magnification devices. We further applied the GRADE approach (grading of recommendation, assessment, development, and evaluation) to assess the quality of evidence regarding the outcomes, including the 12-months and long-term outcome. Comparison-adjusted funnel plots were constructed, and Egger's test was applied to evaluate publication biases and small study effects.33 All network meta-analyses were performed using the statistical package Netmeta (Version 1.2-1) in R Project 4.1.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria).34

Ethical statement

There was no human trial in this systematic review and network meta-analysis, and the approval from the ethics committee does not apply.

Consent statement

Because this study is a systematic review with network meta-analysis, the informed consent does not apply.

Results

Systematic literature review

Fig. 1 presents the whole flowchart of the current NMA. After the initial screening procedure, a total of 33 articles were considered for full-text review; 17 of which were removed based on exclusion criteria (Table S5). In Total, there were 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria and were subject to data extraction, methodologic quality assessment, and data synthesis and analysis.3,6, 7, 8,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of studies selection.

Characteristics of the included studies

Study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The sample size of enrolled studies ranges from 33 to 441 patients (39–427 teeth) with persistent apical periodontitis at 12-months follow-up. The total participants in RCTs and observational cohort studies are 1433 and 958 teeth respectively at 12-months follow-up; 192 and 93 teeth respectively in long-term follow-up. The root-end filling materials compared in our studies includes gutta-percha (GP), intermediate restorative material (IRM), super EBA cement (Super EBA), calcium silicate-based root repair material (RRM), and mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA). The company of materials used in each included study are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of enrolled studies.

| Authors (year) | Design (country) | Population (teeth number) | Teeth type | Materials (Company) | Root-end preparation | Magnification | Significant outcome predictors | Follow up periods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chong et al.35 (2003) | RCT (United Kingdom) | Completed 12-months follow-up: 122 patients/teeth IRM: 58 teeth ProRoot MTA: 64 teeth Completed 24-months follow-up: 108 patients/teeth IRM: 47 teeth ProRoot MTA: 61 teeth |

Only 1 affected tooth/patient was included. Single-rooted anterior teeth and premolar teeth or mesial-buccal root of maxillary molar. |

1. IRM (Dentsply Sirona, Konstanz, Germany) 2. ProRoot MTA (Loma Linda University, CA, USA) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope | – | 1. 12 months 2. 24 months |

| Lindeboom et al.36 (2005) | RCT (Netherlands) | Total: 100 patients/teeth IRM: 50 teeth ProRoot MTA: 50 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars mandibular: anteriors, premolars | 1. IRM (Dentsply International, Milford, DE, USA) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Ultrasonic device | 3.5X Loupe | – | 12 months |

| Christiansen et al.6 (2009) | RCT (Denmark) | Total: 46 teeth in 39 patients GP: 21 teeth ProRoot MTA: 25 teeth |

Incisor, canine, or premolar. | 1. Smoothing gutta-percha 2. ProRoot MTA, White (Dentsply sirona, Johnson City, TN, USA) |

1. Smoothing of the orthograde GP 2. Ultrasonic device |

Microscope (OPMI Pico; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) | with/without buccal bone fenestration | 12 months |

| Wälivaara et al.37 (2009) | RCT (Sweden) | Total: 147 teeth in 131 patients, with 4 teeth excluded due to root fracture. GP: 77 teeth IRM: 66 teeth |

Incisors, canines, premolars, molars. | 1. Ultrafil thermoplasticized gutta-percha with AH plus sealer 2. IRM (Dentsply Sirona, Konstanz, Germany) |

Ultrasonic device | 2.3X Loupe | – | 12–38 months |

| Wälivaara et al.38 (2011) | RCT (Sweden) | Total: 194 teeth in 153 patients IRM: 96 teeth Super EBA: 98 teeth |

Incisors, canines, premolars, molars. | 1. IRM (Dentsply Sirona, Konstanz, Germany) 2. Super-EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co, Skokie, IL) |

Ultrasonic device | 2.3X Loupe | – | 12–21 months |

| Song et al.39 (2012) | RCT (South Korea) | Total: 192 patients/teeth Super EBA: 102 teeth ProRoot MTA: 90 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars, molars mandibular: anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. Super EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co, Skokie, IL) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope (OPMI PICO; Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) | – | 12 months |

| Kim et al.41 (2016) | RCT (South Korea) | Total: with 48-months follow-up: 182 patients/teeth; Completed 12- and 48-months follow-up: 153 teeth Super EBA: 86 teeth ProRoot MTA: 67 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars, molars mandibular: anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. Super EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co, Skokie, IL) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope (OPMI PICO; Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) | – | 1. 12 months 2. 48 months |

| Wälivaara et al.43 (2016) | RCT (Sweden) | Total: 166 teeth in 158 patients IRM: 80 teeth MTA Angelus: 86 teeth |

Maxillary: incisors, canine, premolars, molars mandibular: incisors, canines, premolars, molars. | 1. IRM (Dentsply Sirona, Konstanz, Germany) 2. MTA Angelus (Angelus, Londrina, PR, Brazil) |

Ultrasonic device | 2.3X or 4.2X Loupe | – | 12–25 months |

| Kruse et al.42 (2016) | RCT (Denmark) | Total: 39 teeth in 33 patients completed 12- and 72-months follow-up GP: 20 teeth ProRoot MTA: 19 teeth |

Only included the root-filled single-rooted teeth. MTA group included 10 maxillary premolars, 6 maxillary incisors, and 3 mandibular premolars; while GP group included 9 maxillary premolars, 1 maxillary canine, 7 maxillary incisors, 2 mandibular premolars, and 1 mandibular canine. |

1. Smoothing gutta-percha 2. ProRoot MTA, White (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

1. Smoothing of the orthograde GP 2. Ultrasonic device |

Microscope (OPMI Pico; Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) | – | 1. 12 months 2. 72 months |

| Zhou et al.44 (2017) | RCT (China) | Total: 158 patients/teeth ProRoot MTA: 87 teeth RRM: 71 teeth |

Anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) 2. iRoot BP Plus Root Repair Material (BP-RRM; Innovative BioCeramix Inc, Vancouver, BC, Canada) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope (Opmi PROergo; Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) |

Quality of root fillings, tooth type and size of the lesion | 12 months |

| Safi et al.45 (2019) | RCT (USA) | Total: 120 patients/teeth ProRoot MTA: 57 teeth RRM: 63 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, posteriors mandibular: anteriors, posteriors. | 1. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) 2. Endosequence Root Repair Material (RRM; Brasseler, Savannah, GA) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope | Lesion size, root canal filling quality, root-end filling material depth and root fracture | 15 months |

| von Arx et al.3 (2007) | CS (Switzerland) | Total: 191 patients/teeth, but only 106 teeth were included Super EBA: 55 teeth ProRoot MTA: 51 teeth (Retroplast: 85 teeth, which were not included) |

Maxillary: incisors/canine, premolars, molars mandibular: incisors/canines, premolars, molars. | 1. Super EBA (Staident International, Staines, UK) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Sonic driven microtips | Endoscope | Pain at initial examination | 12 months |

| Song et al.7 (2011) | CS (South Korea) | Total: 427 teeth in 441 patients IRM: 102 teeth Super EBA: 111 teeth ProRoot MTA: 214 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars, molars mandibular: anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. IRM (Dentsply International, Milford, DE, USA) 2. Super EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co, Skokie, IL) 3. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope | Sex, tooth position, lesion type, root-end filling material (only within MTA versus IRM) | 12 months |

| von Arx et al.8 (2012) | CS (Switzerland) | Total: 170 patients/teeth, but only 93 teeth were included Super EBA: 49 teeth ProRoot MTA: 44 teeth (Retroplast: 77 teeth, which were not included) |

Maxillary: incisors/canine, premolars, molars mandibular: incisors/canines, premolars, molars. | 1. Super EBA (Staident International, Staines, UK) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Sonic driven microtips | Endoscope | Mesial-distal bone level at 3-mm versus beyond 3-mm from the CEJ; Root-end filling with ProRoot MTA versus Super EBA | 60 months |

| Song et al.40 (2013) | CS (South Korea) | Total: 344 patients/teeth IRM: 8 teeth Super EBA: 186 teeth ProRoot MTA: 150 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars, molars mandibular: anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. IRM (Caulk Dentsply, Milford, DE) 2. Super EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co, Skokie, IL) 3. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Tulsa Dental, Tulsa, OK) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope | Age, sex, tooth position, arch type, lesion type, and type of post-operative restoration | 12 months |

| Sutter et al.46 (2020) | CS (Switzerland) | Total: 81 patients/teeth Super EBA: 72 teeth ProRoot MTA: 9 teeth |

Maxillary: anteriors, premolars, molars mandibular: anteriors, premolars, molars. | 1. Super EBA (Harry J. Bosworth Co., Skokie, IL, USA) 2. ProRoot MTA (Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) |

Ultrasonic device | Microscope | Tooth type | 12 months |

CS, observational cohort study; RCT, randomized controlled trial; NR, not reported. GP, gutta-percha; IRM, intermediate restorative material; MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate; RRM, calcium silicate-based root repair material; Super EBA, super EBA cement; EBA, ethoxy benzoic acid; PA, periapical film; CBCT, cone-beam computerized tomography.

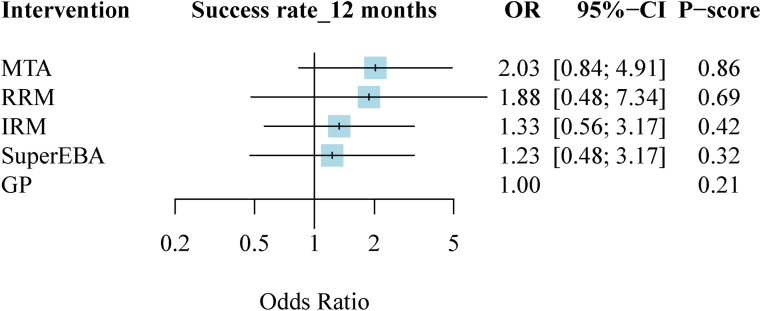

Outcome measure: clinical and radiographic success at 12-months follow-up

15 studies (five treatment nodes, 2391 patients) were found to investigate success rate with different root-end filling materials at 12-months follow-up in the current NMA (the network structure figure is shown in Fig. 2).3,6,7,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 Fig. 3 presented results of success rate at 12-months follow-up. MTA was associated with the highest success rate and the first ranking among all different root-end filling materials. (MTA: OR, 2.03; 95% CI, 0.84–4.91; P-score, 0.86; reference material, GP). Fig. S1 showed head-to-head comparison details of outcomes.

Figure 2.

Network plot of comparisons in success rate at 12-months follow-up. GP, gutta-percha; IRM, intermediate restorative material; MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate; RRM, calcium silicate-based root repair material; super EBA, Super EBA cement; EBA, ethoxy benzoic acid.

Figure 3.

Forest plot at 12-months follow-up. GP, gutta-percha; IRM, intermediate restorative material; MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate; RRM, calcium silicate-based root repair material; Super EBA, super EBA cement; EBA, ethoxy benzoic acid; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

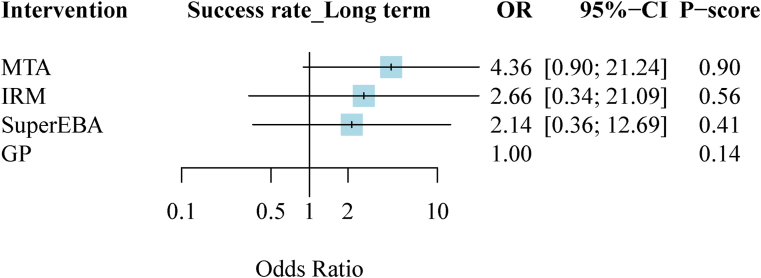

Outcome measure: clinical and radiographic success in long-term follow-up

Four studies (four treatment nodes, 393 patients) were found to investigate success rate with different root-end filling materials in long-term follow-up in the current NMA (the network structure figure is shown in Fig. 4).8,35,41,42 Fig. 5 presented results of success rate in long-term follow-up. MTA was associated with the highest success rate and the first ranking among all different root-end filling materials. (MTA: OR, 4.36; 95% CI, 0.90–21.24; P-score, 0.90; reference material, GP). Fig. S1 showed head-to-head comparison details of outcomes.

Figure 4.

Network plot of comparisons in success rate at long-term follow-up. GP, gutta-percha; IRM, intermediate restorative material; MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate; Super EBA, super EBA cement; EBA, ethoxy benzoic acid.

Figure 5.

Forest plot at long-term follow-up. GP, gutta-percha; IRM, intermediate restorative material; MTA, mineral trioxide aggregate; Super EBA, super EBA cement; EBA, ethoxy benzoic acid; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Risk of bias evaluation

In RCTs using the ROB scale, we found that 86.7% (425/490 items), 5.1% (25/490 items), and 8.2% (40/490 items) of the included studies had overall low, unclear, and high risks of bias, respectively. Vague reporting with “allocation concealment” or “incomplete outcome data” was the main reason for such bias. In cohort studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, we found that one of the studies scored 6, and the others scored 8 (Table S3).

Transitivity and inconsistency

The assumption of network transitivity was established with patient populations across included studies (Table 1). In the outcome of clinical and radiographic success at 12-months follow-up, global inconsistency existed with statistical significance between design inconsistency in design-by-treatment interaction model. Local inconsistency was also observed with statistical significance in the node-splitting model (Fig. S2).

Sensitivity analysis

To evaluate the possible reasons for the inconsistency, we conducted two sensitivity analyses. The sensitivity analyses in long-term follow-up outcome were omitted owing to limited in enrolled studies.

After excluding high risk-of-bias studies, four studies were excluded in the 12-months follow-up outcome.37,38,43,46 The remaining 11 included studies (five treatment nodes, 1836 teeth) had a constant follow-up period of around 12 months and were enrolled in first sensitivity analysis.

Considering the possible heterogeneity caused by treatment-related factors, four studies using loupes as magnification devices were excluded in the 12-months follow-up group.36, 37, 38,43 In the remaining 11 included studies (five treatment nodes, 1902 teeth) enrolled in second sensitivity analysis, endoscopes or microscopes were used as magnification devices.

In both sensitivity analyses, MTA, RRM and Super EBA were associated with significantly better success rates in the 12-months follow-up than the other root-end filling materials. (MTA: OR, 5.62; 95% CI, 1.58–19.99; P-score, 0.88; RRM: OR, 5.23; 95% CI, 1.05–25.98; P-score, 0.74; Super EBA: OR, 3.99; 95% CI, 1.06–15.04; P-score, 0.54; reference material, GP). According to the P-score value, MTA was ranked with the greatest success rate among different types of the materials in both sensitivity analyses. RRM had a similar effect with MTA and was ranked as the second choice. Both sensitivity analyses results disclosed no existing inconsistency (Fig. S3).

Publication bias and GRADE assessment

Funnel plots of publication bias across the included studies revealed general symmetry, and the results of Egger's test indicated no significance which might suggest that there was no evidence of potential small-study effects or publication bias (Fig. S4). GRADE approach figures for rating the quality of treatment effect estimate were presented in Fig. S5.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first network meta-analysis to analyze the effectiveness of different root-end filling materials using with surgical endodontic treatment in modern techniques. In line with previous meta-analyses by von Arx et al. and Tsesis et al., our results suggest that MTA remains the best choice of root-end filling materials compared to the competitor materials, based on currently available evidence.9,47 With the aid of NMA, we could combine the direct evidence and the indirect evidence to show the ranking of new root-end filling materials compared to baseline data of MTA and GP in the future.

Since MTA was developed at Loma Linda University by Professor Mahmoud Torabinejad and colleagues in the early 1990s, it has undergone numerous in vitro and in vivo investigations showing superior performances of cytocompatibility, bioactivity, sealing ability and antimicrobial effects.48 Although with some weak points of long setting time and problems in handling properties, MTA has been widely applied in endodontics with stable clinical success. Recent clinical studies show not only short-term success but also long-term follow-ups of MTA using as the root-end filling material. Çalısxkan et al. recorded a success rate of 80% in 90 anterior teeth subjected to endodontic microsurgery with two to six years follow-up.49 von Arx et al. recorded a healing rate of 81.5% in a sample of 119 teeth subjected to ten years follow-up.50 Pallarés-Serrano A. et al. also reports the mean healing rate of 81% in 111 teeth using MTA as root-end fillings subjected to endodontic microsurgery after five to nine years follow-up.51

Recently, various calcium silicate-based cements for endodontics have emerged, aimed at overcoming shortcuts of ProRoot MTA. Several studies have proved that RRM are also biocompatible materials with good sealing ability which is suitable for root-end filling.52, 53, 54 Clinical studies showed high success rates similar to MTA while applying RRM in modern endodontic surgery.55, 56, 57 In the animal model performed by Chen et al., EndoSequence Root Repair Material even achieved a better tissue healing response than MTA at the resected root surface histologically.58 Besides, there are also many studies interested in using Biodentine as a root-end filling material, but still need more clinical evidence and comparative studies presently.59,60

Among the four excluded studies with high risk-of-bias in the first sensitivity analysis,37,38,43,46 three studies by Wälivaara et al. were excluded in the group of 12-months follow-up, owing to wide-range of the follow-up times (see Table 1) and lacking of allocation concealment. Besides, the types of magnification devices are another factor to be considered, so we also conducted another sensitivity analysis based on it. In a previous systematic review, no significant difference was found in outcomes among patients treated with magnifying loupes, a surgical microscope, or an endoscope.61 However, in the meta-analysis by Tsesis et al., the use of either an operative microscope or endoscope could significantly improve the outcome compared with loupes in low risk of bias studies.9 The results of two sensitivity analyses in our study show that by excluding studies with heterogeneity in protocols or treatment-related factors, the 95% confidence intervals became more concentrated; And the ranking of root-end filling materials became significant.

Modifications have been made to increase the strength of the evidence in our network meta-analysis. First, we strictly followed standardized guidelines based on the PRISMA statement to improve reporting of systematic reviews. For evaluating the outcome of surgical endodontic treatment, patient-related factors, tooth-related factors, and treatment related factors must be taken into consideration.62 With strict inclusion criteria of modern surgical endodontic treatment, the variations caused by treatment-related factors were under control in the present study. By including the comparative studies instead of comparing the pooled success rate of respective materials, variations from the patient-related factors and the tooth-related factors were kept to the minimum. Second, we show the effectiveness of different root-end filling materials achieved in modern surgical endodontic treatment, compared with the baseline of gutta-percha groups. Third, we conducted two sensitivity analyses to evaluate possible reasons of inconsistency; Factors that could increase inconsistency were successfully identified and excluded, so the ranking in different root-end filling materials became significant.

Nevertheless, the present network meta-analysis still has some limitations. To confirm the efficacy and validity of the outcome in a short-term follow-up, one should take careful notice of the well-designed clinical trials of microsurgery comparing the short-term and long-term follow-up.12,63,64 However, there are only three included studies that conform to the follow-up periods more than four years in our results.8,41,42 Within the limitations of this study, there was no statistically significant difference for success rates between root-end filling materials in long-term follow-up group under our present evidence.

In conclusion, the current results of this network meta-analysis indicated that MTA remains the first choice of root-end filling materials. Within further sensitivity analysis, MTA, RRM and Super EBA have significantly better effects compared with baseline data of GP in 12-months follow up. Comparative randomized clinical trials in long-term follow up are warranted in future investigations.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants (TSGH-D-110142) and (TSGH-C02-111025) from the Tri-Service General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. We expressed our most sincere appreciation to all study participants.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2022.05.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Setzer F.C., Shah S.B., Kohli M.R., Karabucak B., Kim S. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature--part 1: comparison of traditional root-end surgery and endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2010;36:1757–1765. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S., Kratchman S. Modern endodontic surgery concepts and practice: a review. J Endod. 2006;32:601–623. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Arx T., Jensen S.S., Hänni S. Clinical and radiographic assessment of various predictors for healing outcome 1 year after periapical surgery. J Endod. 2007;33:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsesis I., Faivishevsky V., Kfir A., Rosen E. Outcome of surgical endodontic treatment performed by a modern technique: a meta-analysis of literature. J Endod. 2009;35:1505–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong B., Pitt Ford T. Root-end filling materials: rationale and tissue response. Endod Top. 2005;11:114–130. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christiansen R., Kirkevang L.L., Hørsted-Bindslev P., Wenzel A. Randomized clinical trial of root-end resection followed by root-end filling with mineral trioxide aggregate or smoothing of the orthograde gutta-percha root filling--1-year follow-up. Int Endod J. 2009;42:105–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song M., Jung I.Y., Lee S.J., Lee C.Y., Kim E. Prognostic factors for clinical outcomes in endodontic microsurgery: a retrospective study. J Endod. 2011;37:927–933. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Arx T., Jensen S.S., Hänni S., Friedman S. Five-year longitudinal assessment of the prognosis of apical microsurgery. J Endod. 2012;38:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsesis I., Rosen E., Taschieri S., Telishevsky Strauss Y., Ceresoli V., Del Fabbro M. Outcomes of surgical endodontic treatment performed by a modern technique: an updated meta-analysis of the literature. J Endod. 2013;39:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Guerrero C., Guauque S.Q., Molano N., Pineda G.A., Nino-Barrera J.L., Marín-Zuluaga D.J. Predictors of clinical outcomes in endodontic microsurgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. G Ital Endod. 2017;31:2–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohli M.R., Berenji H., Setzer F.C., Lee S.M., Karabucak B. Outcome of endodontic surgery: a meta-analysis of the literature-part 3: comparison of endodontic microsurgical techniques with 2 different root-end filling materials. J Endod. 2018;44:923–931. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang S., Chen N.N., Yu V.S.H., Lim H.A., Lui J.N. Long-term success and survival of endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2020;46:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2019.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pinto D., Marques A., Pereira J.F., Palma P.J., Santos J.M. Long-term prognosis of endodontic microsurgery-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2020;56:447. doi: 10.3390/medicina56090447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Y., Li X., Yin S. Outcomes of mta as root-end filling in endodontic surgery: a systematic review. Quintessence Int. 2010;41:557–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma X., Li C., Jia L., et al. Materials for retrograde filling in root canal therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD005517. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005517.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H., Guo Z., Li C., et al. Materials for retrograde filling in root canal therapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005517.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutton B., Salanti G., Caldwell D.M., et al. The prisma extension statement for reporting of systematic reviews incorporating network meta-analyses of health care interventions: checklist and explanations. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:777–784. doi: 10.7326/M14-2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., et al. The prisma 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup D.F., Berlin J.A., Morton S.C., et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (moose) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rud J., Andreasen J.O., Jensen J.E. A follow-up study of 1,000 cases treated by endodontic surgery. Int J Oral Surg. 1972;1:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(72)80014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutmann J.L., Harrison J.W. 1st ed. Blackwell Scientific Publications; Boston, MA, USA: 1991. Surgical endodontics. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molven O., Halse A., Grung B. Incomplete healing (scar tissue) after periapical surgery--radiographic findings 8 to 12 years after treatment. J Endod. 1996;22:264–268. doi: 10.1016/s0099-2399(06)80146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the newcastle-ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., et al. The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.König J., Krahn U., Binder H. Visualizing the flow of evidence in network meta-analysis and characterizing mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2013;32:5414–5429. doi: 10.1002/sim.6001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salanti G. Indirect and mixed-treatment comparison, network, or multiple-treatments meta-analysis: many names, many benefits, many concerns for the next generation evidence synthesis tool. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:80–97. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salanti G., Ades A.E., Ioannidis J.P. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rücker G., Schwarzer G. Ranking treatments in frequentist network meta-analysis works without resampling methods. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0060-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson D., White I.R., Riley R.D. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2012;31:3805–3820. doi: 10.1002/sim.5453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J.P., Jackson D., Barrett J.K., Lu G., Ades A.E., White I.R. Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:98–110. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu-Kang T. Node-splitting generalized linear mixed models for evaluation of inconsistency in network meta-analysis. Value Health. 2016;19:957–963. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salanti G., Del Giovane C., Chaimani A., Caldwell D.M., Higgins J.P. Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaimani A., Higgins J.P., Mavridis D., Spyridonos P., Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in stata. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rücker G. Network meta-analysis, electrical networks and graph theory. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3:312–324. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong B.S., Pitt Ford T.R., Hudson M.B. A prospective clinical study of mineral trioxide aggregate and irm when used as root-end filling materials in endodontic surgery. Int Endod J. 2003;36:520–526. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.2003.00682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindeboom J.A., Frenken J.W., Kroon F.H., van den Akker H.P. A comparative prospective randomized clinical study of mta and irm as root-end filling materials in single-rooted teeth in endodontic surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wälivaara D.A., Abrahamsson P., Sämfors K.A., Isaksson S. Periapical surgery using ultrasonic preparation and thermoplasticized gutta-percha with ah plus sealer or irm as retrograde root-end fillings in 160 consecutive teeth: a prospective randomized clinical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:784–789. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wälivaara D.Å., Abrahamsson P., Fogelin M., Isaksson S. Super-eba and irm as root-end fillings in periapical surgery with ultrasonic preparation: a prospective randomized clinical study of 206 consecutive teeth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Song M., Kim E. A prospective randomized controlled study of mineral trioxide aggregate and super ethoxy-benzoic acid as root-end filling materials in endodontic microsurgery. J Endod. 2012;38:875–879. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Song M., Kim S.G., Lee S.J., Kim B., Kim E. Prognostic factors of clinical outcomes in endodontic microsurgery: a prospective study. J Endod. 2013;39:1491–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim S., Song M., Shin S.J., Kim E. A randomized controlled study of mineral trioxide aggregate and super ethoxybenzoic acid as root-end filling materials in endodontic microsurgery: long-term outcomes. J Endod. 2016;42:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kruse C., Spin-Neto R., Christiansen R., Wenzel A., Kirkevang L.L. Periapical bone healing after apicectomy with and without retrograde root filling with mineral trioxide aggregate: a 6-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Endod. 2016;42:533–537. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wälivaara D.Å.A.P., Fogelin M. Periapical surgery with irm and mta as retrograde root-end fillings‒a prospective randomized clinical study of 186 consecutive teeth. Dentistry. 2016;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou W., Zheng Q., Tan X., Song D., Zhang L., Huang D. Comparison of mineral trioxide aggregate and iroot bp plus root repair material as root-end filling materials in endodontic microsurgery: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Endod. 2017;43:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Safi C., Kohli M.R., Kratchman S.I., Setzer F.C., Karabucak B. Outcome of endodontic microsurgery using mineral trioxide aggregate or root repair material as root-end filling material: a randomized controlled trial with cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation. J Endod. 2019;45:831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2019.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sutter E., Valdec S., Bichsel D., Wiedemeier D., Rücker M., Stadlinger B. Success rate 1 year after apical surgery: a retrospective analysis. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;24:45–49. doi: 10.1007/s10006-019-00815-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.von Arx T., Peñarrocha M., Jensen S. Prognostic factors in apical surgery with root-end filling: a meta-analysis. J Endod. 2010;36:957–973. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson B.R., Fayad M.I., Berman L.H. In: Cohen's pathways of the pulp. 12th ed. Berman L.H., Hargreaves K.M., editors. Elsevier; St. Louis, Missouri: 2020. Periradicular surgery; p. 446. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Çalışkan M.K., Tekin U., Kaval M.E., Solmaz M.C. The outcome of apical microsurgery using mta as the root-end filling material: 2- to 6-year follow-up study. Int Endod J. 2016;49:245–254. doi: 10.1111/iej.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Arx T., Jensen S.S., Janner S.F.M., Hänni S., Bornstein M.M. A 10-year follow-up study of 119 teeth treated with apical surgery and root-end filling with mineral trioxide aggregate. J Endod. 2019;45:394–401. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pallarés-Serrano A., Glera-Suarez P., Tarazona-Alvarez B., Peñarrocha-Diago M., Peñarrocha-Diago M., Peñarrocha-Oltra D. Prognostic factors after endodontic microsurgery: a retrospective study of 111 cases with 5 to 9 years of follow-up. J Endod. 2021;47:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Damas B.A., Wheater M.A., Bringas J.S., Hoen M.M. Cytotoxicity comparison of mineral trioxide aggregates and endosequence bioceramic root repair materials. J Endod. 2011;37:372–375. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lovato K.F., Sedgley C.M. Antibacterial activity of endosequence root repair material and proroot mta against clinical isolates of enterococcus faecalis. J Endod. 2011;37:1542–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma J., Shen Y., Stojicic S., Haapasalo M. Biocompatibility of two novel root repair materials. J Endod. 2011;37:793–798. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shinbori N., Grama A.M., Patel Y., Woodmansey K., He J. Clinical outcome of endodontic microsurgery that uses endosequence bc root repair material as the root-end filling material. J Endod. 2015;41:607–612. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Taha N.A., Aboyounes F.B., Tamimi Z.Z. Root-end microsurgery using a premixed tricalcium silicate putty as root-end filling material: a prospective study. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Arx T., Janner S.F.M., Haenni S., Bornstein M.M. Bioceramic root repair material (bcrrm) for root-end obturation in apical surgery. An analysis of 174 teeth after 1 year. Swiss Dent J. 2020;130:390–396. doi: 10.61872/sdj-2020-05-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen I., Karabucak B., Wang C., et al. Healing after root-end microsurgery by using mineral trioxide aggregate and a new calcium silicate-based bioceramic material as root-end filling materials in dogs. J Endod. 2015;41:389–399. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paños-Crespo A., Sánchez-Torres A., Gay-Escoda C. Retrograde filling material in periapical surgery: a systematic review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2021;26:e422–e429. doi: 10.4317/medoral.24262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tang J.J., Shen Z.S., Qin W., Lin Z. A comparison of the sealing abilities between biodentine and mta as root-end filling materials and their effects on bone healing in dogs after periradicular surgery. J Appl Oral Sci. 2019;27 doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Del Fabbro M., Taschieri S. Endodontic therapy using magnification devices: a systematic review. J Dent. 2010;38:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Friedman S. The prognosis and expected outcome of apical surgery. Endod Top. 2006;11:219–262. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kang M., Jung H., Song M., Kim S.Y., Kim H.C., Kim E. Outcome of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic microsurgery: a meta-analysis. Clin Oral Invest. 2015;19:569–582. doi: 10.1007/s00784-015-1398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Torabinejad M., Corr R., Handysides R., Shabahang S. Outcomes of nonsurgical retreatment and endodontic surgery: a systematic review. J Endod. 2009;35:930–937. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.