Abstract

Herpes simplex virus (HSV), an alphaherpesvirus, is highly prevalent in the human population and is known to cause oral and genital herpes and various complications. Represented by acyclovir (ACV), nucleoside analogs have been the main clinical treatment against HSV infection thus far. However, due to prolonged and excessive use, HSV has developed ACV-resistant strains. Therefore, effective treatment against ACV-resistant HSV strains is urgently needed. In this review, we summarized the plant extracts and natural compounds that inhibited ACV-resistant HSV infection and their mechanism of action.

Keywords: herpes simplex virus, antiviral herbs, natural products, acyclovir-resistant, mode of action

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is an alphaherpesvirus belonging to the Herpesviridae family. The virion is made up of large double-stranded DNA, an icosapentahedral capsid, a tegument, and a glycoprotein-filled envelope (Whitley and Roizman, 2001). The viral entry into the host cells begins with the interaction between viral glycoproteins, gB, and gC with cell surface receptors. The fusion of the viral envelope is mediated by glycoproteins, gD, gB, and the heterodimer gH/gL, allowing the viral entry into the host cells (Kukhanova et al., 2014). After the entry of the viral particle, the capsid is trafficked to the nuclear pores along a network of microtubules and subsequently into the nucleus (Mues et al., 2015). VP16 triggers the transcription of six immediate early (IE) genes (ICP0, ICP4, ICP22, ICP27, ICP47, and US1.5) and the activation of early (E) and late (L) genes. With the help of the helicase-primase complex and some viral proteins, such as UL9 and ICP8, the viral DNA unwinds and replicates. The capsid is initially assembled in the nucleus and then transported into the cytoplasm. The virion is trafficked intracellularly, during which the virion forms an outer shell, package, and assemble. Finally, the virion is egressed to infect other cells, resulting in cell-to-cell spread. The replication cycle lasts for 18–20 h, which has been briefly illustrated in Figure 1. After primary infection, HSV virions replicate in large numbers in neuronal cells, enter sensory neuron axons, and hide in the neuronal cell nucleus (Kukhanova et al., 2014). The viruses establish latent infections, which are reactivated by persistent psychological stress and other stimuli (Cohen et al., 1999). HSV infections have become a major public health concern. According to a WHO investigation, more than one billion people worldwide are infected with HSV-1-caused oral herpes, and an estimated 500 million are infected with HSV-2-caused genital herpes (Kushch et al., 2021).

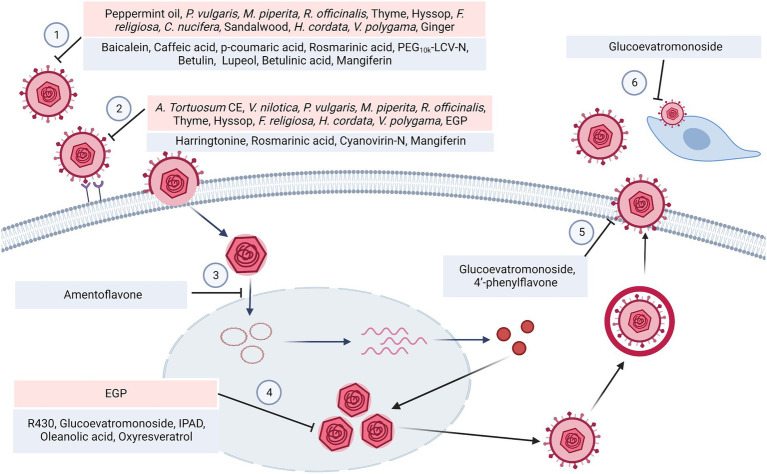

Figure 1.

HSV replication cycle and the steps that were targeted by the phytomedicines mentioned in this review. (1) Plant extracts such as peppermint oil, P. vulgaris extract as well as the phytochemicals such as baicalein, caffeic acid showed virucidal effect. (2) HSV virions requires a set of viral glycoproteins to mediate host cell attachment and entry, which could be suppressed by V. nilotica extract, M. piperita extract, harringtonine and etc. (3) Then the capsids are transported into the nucleus, which could be inhibited by Amentoflavone. (4) The biosynthesis process produced viral DNA, which could be blocked by amentoflavone, R430 and IPAD. The phytomedicines suppressed the helicase-primase complex, Immediate Early genes (ICP0, ICP4, ICP27), Early genes (ICP6, ICP8) and Late genes (UL19, UL27, UL44, US6). (5) Glucoevatromonoside and 4′-phenylflavone exerted the inhibitory effect on virion egression. (6) The cell-to-cell spread could be interfered by glucoevatromonoside.

Acyclovir (ACV) is widely used to treat HSV infections and inhibits HSV-specific DNA polymerase and impedes HSV replication and further infection (Brigden and Whiteman, 1983). Since HSV infection is incurable and recurrent and prolonged, the excessive use of nucleoside analogs such as ACV causes severe side effects, including neurotoxicity and renal impairment (Paluch et al., 2021) and the emergence of drug resistance. ACV resistance was reported to be 7% in immunocompromised patients, but was only 0.27% in healthy immunocompetent adults. The emergence of drug-resistant HSV strains restricts therapeutic options, preventing timely treatment and causing a variety of diseases (Stranska et al., 2005). The mutant of HSV-induced TK led to ACV resistance in 95% of cases, and the mutant of DNA polymerase (DNA-pol) enzymes also accounted for resistance (Field, 2001; Morfin and Thouvenot, 2003). The resources and mechanism of resistance of ACV-resistant HSV strains mentioned in this review were organized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Review of the ACV-resistant strains used in the collected literature.

This review summarizes a number of ACV-resistant HSV strains that have been genetically engineered or isolated from patients (Table 1), medicinal extracts (Table 2), and phytochemicals (Table 3) that exert antiviral effects and mechanisms of action.

Table 2.

Review of the plants that show anti-herpes simplex virus activities with their prospective family, part, type of extract, and mode of action.

| Family | Plant | Part | Extract | Results | Mode of action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Araceae | Arisaema Tortuosum | Leaves | Chloroform | Vero Cells CC50 = 402 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr EC50 = 0.86 μg/ml SI = 467.4 | Inhibiting viral attachment and entry as well as the late events of the HSV-2 replication cycle | Ritta et al., 2020 |

| Asteraceae | Echinacea purpurea | Aerial parts | Not mentioned | HFF Cells CC50 = 1:2 dilution Five ACV-R strains of HSV-1 Median ED50 = 1:100 Ten ACV-R strains of HSV-2 Median ED50 = 1:200 | Probable inhibition of postinfection steps | Thompson, 1998 |

| Caulerpaceae | Caulerpa racemosa | Not mentioned | Hot water | Vero Cells CC50 > 1,000 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr B2006 EC50 = 2.4 ± 0.7 μg/ml, SI > 417 HSV-1 ACVr Field EC50 = 2.2 ± 0.1 μg/ml, SI > 454 | Not mentioned | Ghosh et al., 2004 |

| Cecropiaceae | Cecropia glaziovii Snethl. | Leaves | Ethanol | Vero Cells CC50 > 2.000 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 29R EC50 = 40 μg/ml, SI = 50 | Not mentioned | Petronilho et al., 2012 |

| Fabaceae | Vachellia nilotica | Bark | Methanol | Vero Cells CC50 = 144 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr EC50 = 6.71 μg/ml, SI = 21.5 | Partial virus inactivation; Inhibition of viral attachment | Donalisio et al., 2018 |

| Lamiaceae | Mentha piperita L. | Leaves | Not mentioned | RC-37 Cells TC50 = 0.014% | Virucidal effect | Schuhmacher et al., 2003 |

| Prunella vulgaris | Dried herbs | Aqueous ethanol | RC-37 Cells Prunella 20% ethanol TC50 = 362.4 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 1.3% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% Prunella 80% ethanol TC50 = 192.1 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% | Virucidal effect; Inhibition of viral adsorption | Reichling et al., 2008 | |

| Mentha piperita | Dried leaves | Aqueous ethanol | RC-37 Cells Peppermint 20% ethanol TC50 = 422.4 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 2.4% Peppermint 80% ethanol TC50 = 281.6 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% | |||

| Rosmarinus officinalis | Dried leaves | Aqueous ethanol | RC-37 Cells Rosemary 20% ethanol TC50 = 253.8 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 29.7% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% Rosemary 80% ethanol TC50 = 73.9 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% | |||

| Thymus vulgaris | Dried herbs | Aqueous ethanol | RC-37 Cells Thyme 20% ethanol TC50 = 293.7 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 2.2% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% Thyme 80% ethanol TC50 = 62.3 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0% | |||

| Thymus vulgari (Thyme) | Essential oil | Not mentioned | RC-37 Cells CC50 = 0.007 ± 0.0003% HSV-1 ACVr Aneglotti Infectivity = 4.1 ± 3.2% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 Infectivity = 1.2 ± 0.9% HSV-1 ACVr 496/02 Infectivity = 0.3 ± 0.3% | Virucidal effect | Schnitzler et al., 2007 | |

| Hyssopus officinalis (Hyssop) | Essential oil | Not mentioned | RC-37 Cells CC50 = 0.0075 ± 0.002% HSV-1 ACVr Aneglotti Infectivity = 0.2 ± 0.2% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 Infectivity =0.3 ± 0.3% HSV-1 ACVr 496/02 Infectivity =0.1 ± 0.1% | |||

| Salvia desoleana Atzei & V. Picci | SD1(EO fraction) | Not mentioned | Vero Cells CC50 = 58.11 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr EC50 = 6.58 μg/ml, SI = 8.83 | Inhibition of later step of viral replication cycle | Cagno et al., 2017 | |

| Prunella vulgaris L. | Dried spikes | Water | Vero Cells HSV-1 ACVr DM2.1 EC50 = 25 ~ 50 μg/ml | Not mentioned | Chiu et al., 2004 | |

| Water-ethanol | Vero Cells CC50 > 500 μg/ml | Inhibition of adsorption and penetration | Xu et al., 1999 | |||

| Moraceae | Ficus religiosa L. | Bark | Water | Vero Cells CC50 = 1,530 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr EC50 = 6.28 ± 0.04 μg/ml, SI = 243.6 | Virucidal effect | Ghosh et al., 2016 |

| Chloroform | Vero Cells CC50 = 809.6 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr EC50 = 13.50 ± 0.50 μg/ml, SI = 59.97 | Inhibition of viral attachment and entry; Limitation of viral progeny production | ||||

| Palmae | Cocos nucifera Linn. | Husk fiber | Water | Crude extract: HEp-2 Cells MNTC = 100 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VI = 1.81, PI = 98.4, VII = 3.2, PI>99.9 Vero Cells MNTC = 100 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VI = 3, PI>99.9, VII = 3.13, PI>99.9 Fraction II: HEp-2 Cells MNTC = 25 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VI = 1, PI = 90.0, VII = 5.0, PI>99.9 Vero Cells MNTC = 100 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VI = 3.25, PI>99.9, VII = 4.59, PI>99.9 | Virucidal effect | Esquenazi et al., 2002 |

| Rubiaceae | Nauclea latifolia Smith | Root bark | CH2Cl2/MeOH (50:50) mixture | Vero Cells CC50 > 100 μg/ml HSV-2 ACVr IC50 = 5.38 μg/ml | Inhibition of post-infection stage | Donalisio et al., 2013 |

| Santalaceae | Santalum album (Sandalwood) | Essential oil | Not mentioned | RC-37 Cells CC50 = 0.0015 ± 0.0001% HSV-1 ACVr Aneglotti Infectivity = 0.2 ± 0.2% HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 Infectivity =1.1 ± 0.8% HSV-1 ACVr 496/02 Infectivity =0.3 ± 0.2% | Virucidal effect | Schnitzler et al., 2007 |

| Saururaceae | Houttuynia cordata | Not mentioned | Water | Vero Cells CC50 > 100 mg/ml HSV-1 ACVr AR EC50 = 1.11 mg/ml SI = 90.09 | Virucidal effect; Inhibition of virus entry (target gD); Inhibition of HSV-induced NF-κB activation | Hung et al., 2015 |

| Verbenaceae | Lippia Graveolens | Essential oil | Not mentioned | HEp-2 Cells CC50 = 735 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr EC50 = 55.9 μg/ml, SI50 = 13.1 | Not mentioned | Pilau et al., 2011 |

| Vitex polygama Cham. | Fruits | Ethyl acetate | HEp-2 Cells MNTC = 50 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VII = 0.83, PI = 85.2 | Virucidal effect; Slight intracellular inhibition | Goncalves et al., 2001 | |

| Leaves | HEp-2 Cells MNTC = 25 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VII = 0.58, PI = 73.7 | Intracellular inhibition | ||||

| VPAF-1 | HEp-2 Cells MNTC = 100 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr VII = 0.91, PI = 87.7 | Inhibition of viral attachment | ||||

| Zingiberaceae | Zingiber officinale (Ginger) | Essential oil | Not mentioned | RC-37 cells CC50 = 0.004 ± 0.001% HSV-1 ACVr Angelotti infectivity 0.2 ± 0.1%, HSV-1 ACVr 1246/99 infectivity 0.3 ± 0.2%, HSV-1 ACVr 496/02 infectivity 0.1 ± 0.1% | Virucidal effect | Schnitzler et al., 2007 |

Table 3.

A review of the bioactive natural products reported to have potent anti-HSV properties.

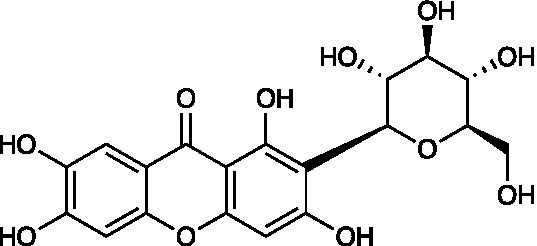

| Chemical class | Compound | Structure | Results | Mode of action | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

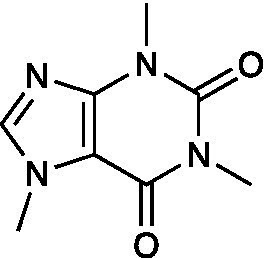

| Alkaloid | Caffeine |

|

HSV-1 ACVr TK-deficient EC50 = 1.10 ± 0.14 mg/ml HSV-1 PAAr EC50 = 1.11 ± 0.08 mg/ml | Not mentioned | Yoshida et al., 1996 |

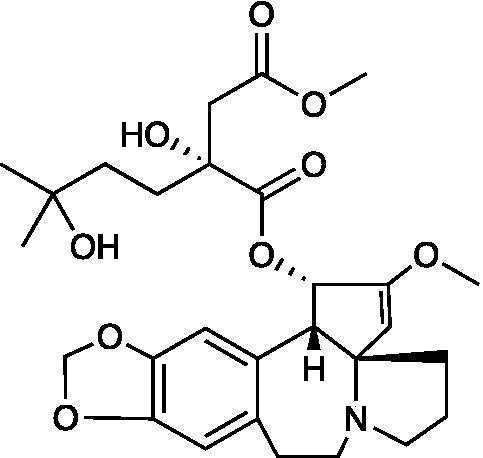

| Harringtonine |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 239.6 ± 26.3 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 IC50 = 0.1584 ± 0.009 μM, SI = 1512.63 HSV-1 ACVr Blue IC50 = 0.1320 ± 0.007 μM, SI = 1815.15 | Inhibition of viral membrane fusion and virus entry targeting HVEM | Liu Y. et al., 2021 | |

| R430 |

|

HiPSC Cells CC50 = 7.39 μM HSV-1 ACVr TK-deletion EC50 = 0.71 μM HSV-1 ACVr PAAr IC50 = 0.95 μM | Inhibition of transcription and translation of the viral IE gene ICP4 and DNA polymerase | McNulty et al., 2016; D'Aiuto et al., 2018 | |

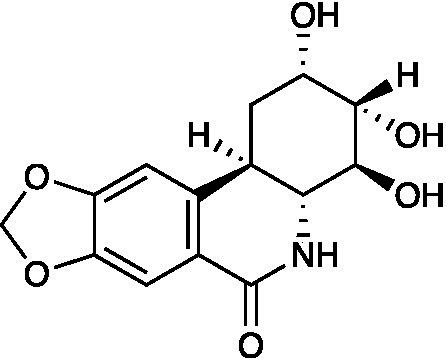

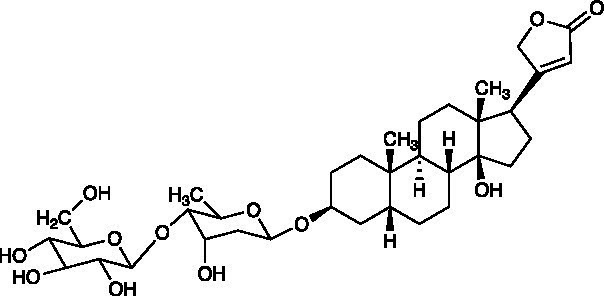

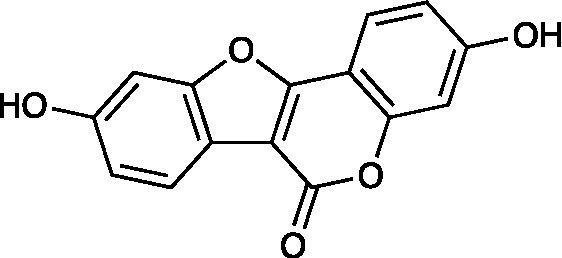

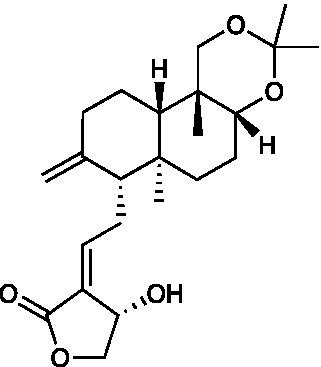

| Cardenolide | Glucoevatromonoside |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 273.95 ± 46.46 μM GMK-AH1 Cells CC50 > 250 μM HSV-1 ACVr 29R IC50 = 0.06 ± 0.01 μM, SI = 4.566 | Inhibition of viral protein synthesis (ICP27, UL42, gB, and gD); Reduction of viral cell-to-cell spread | Bertol et al., 2011 |

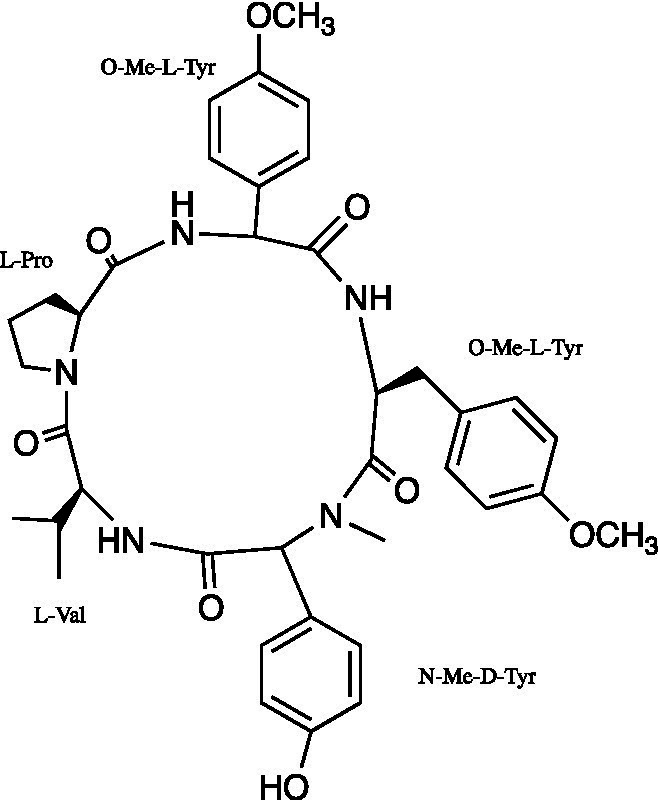

| Cyclic pentapeptide | Aspergillipeptide D |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 208.723 ± 9.717 μM HSV-1 ACVr 106 EC50 = 10.486 ± 0.929 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 EC50 = 8.277 ± 1.249 μM HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 7.9875 ± 0.616 μM | Inhibition of intercellular spread targeting gB | Wang et al., 2020 |

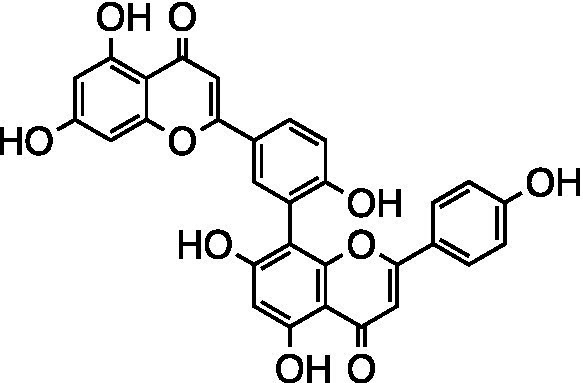

| Flavonoid | Amentoflavone |

|

Vero Cells CC50 > 100 μM HSV-1 ACVr 106 EC50 = 11.11 ± 0.71 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 EC50 = 28.22 ± 2.51 μM HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 25.71 ± 3.97 μM | Inhibition of early viral infection; Reduction of viral nuclear transport by inhibiting cofilin-mediated F-actin assembly | Li et al., 2019 |

| Baicalein |

|

Vero Cells CC50 > 200 μmol/l HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 18.6 μmol/l, SI > 10.8 Hacat Cells CC50 > 200 μmol/l HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 14.8 μmol/l, SI > 13.5 | Inactivation of viral particles; Suppression of NF-κB activation | Luo et al., 2020 | |

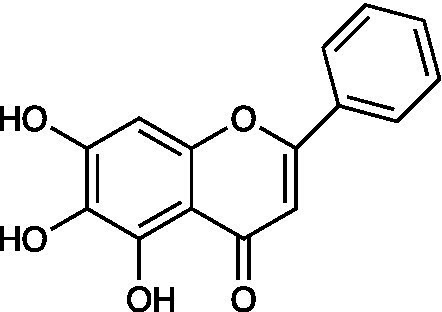

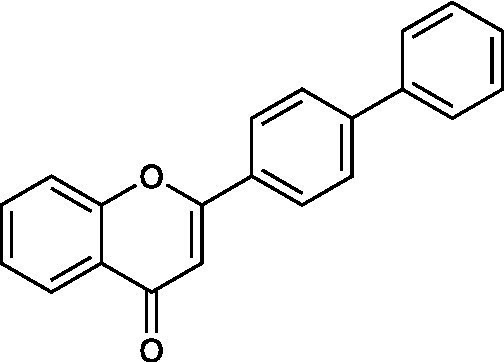

| 4′-phenylflavone |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 510 ± 46 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr A4-3 IC50 = 15 ± 1.4 μg/ml | Inhibition of a late step of viral replication; Reduction of the release of progeny viruses | Hayashi et al., 2012 | |

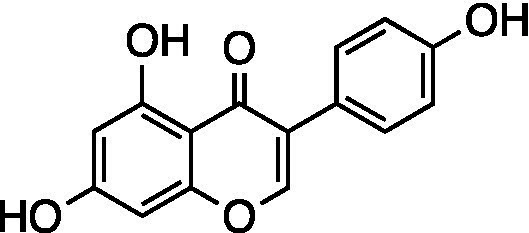

| Genistein |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 54.41 ± 5.39 μM GMK-AH1 Cells CC50 = 98.17 ± 14.78 μM HSV-1 ACVr 29R IC50 = 7.76 ± 0.76 μM, SI = 7.01 | Reduce HSV-1 protein expression | Argenta et al., 2015 | |

| Coumestrol |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 105.3 ± 22.33 μM GMK-AH1 Cells CC50 > 1,000 μM HSV-1 ACVr 29R IC50 = 3.34 ± 0.68 μM, SI = 31.52 | Inhibition of the early stages of viral infection; Reduction of HSV-1 protein expression | ||

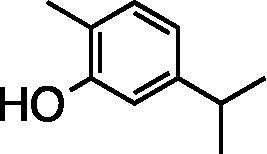

| Phenolics | Carvacrol |

|

HEp-2 Cells CC50 = 250 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr EC50 = 28.6 μg/ml, SI50 = 8.7 | Inhibition of postinfection stage | Pilau et al., 2011 |

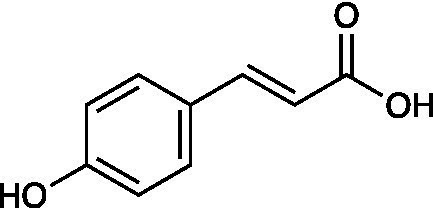

| Caffeic acid |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 = 150 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 1 IC50 = 100 μg/ml, SI = 1.5 HSV-1 ACVr 2 IC50 = 90 μg/ml, SI = 1.7 | Virucidal effect | Astani et al., 2014 | |

| p-coumaric acid |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 ≥ 1,000 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 1 IC50 = 7 μg/ml, SI ≥ 143 HSV-1 ACVr 2 IC50 = 10 μg/ml, SI ≥ 100 | Virucidal effect | ||

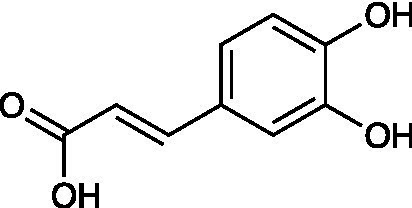

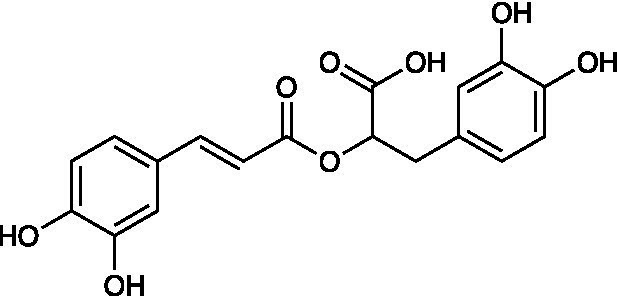

| Rosmarinic acid |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 = 200 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 1 IC50 = 10 μg/ml, SI = 20 HSV-1 ACVr 2 IC50 = 8 μg/ml, SI = 25 | Virucidal effect; Inhibition of viral attachment | ||

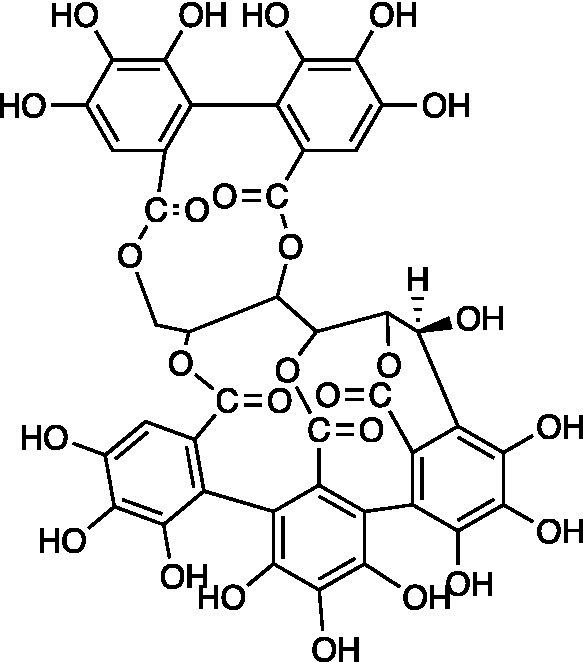

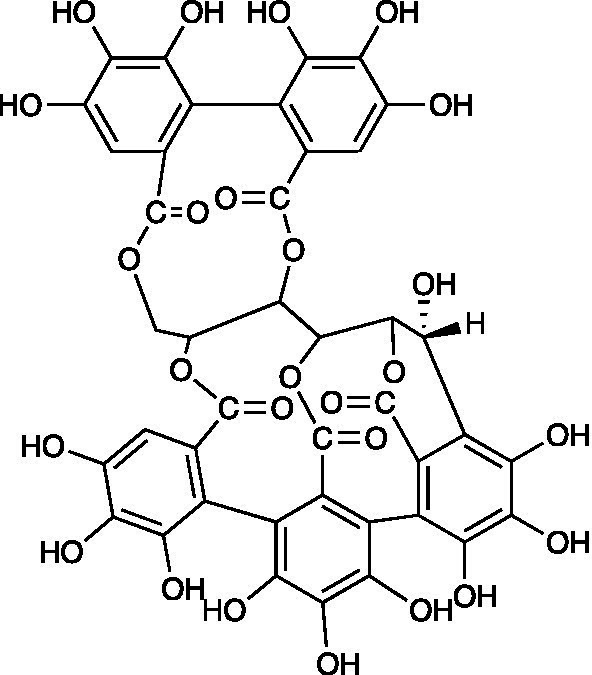

| Polyphenolic | Castalagin |

|

MDBK Cells HSV-1 ACVr R-100 IC50 = 0.04 ± 0.002 μM HSV-2 ACVr PU IC50 = 0.43 ± 0.03 μM | Not mentioned | Vilhelmova-Ilieva et al., 2014 |

| Vescalagin |

|

MDBK Cells HSV-1 ACVr R-100 IC50 = 0.06 ± 0.003 μM HSV-2 ACVr PU IC50 = 0.46 ± 0.0.02 μM | |||

| Grandinin |

|

MDBK Cells HSV-1 ACVr R-100 IC50 = 0.04 ± 0.02 μM HSV-2 ACVr PU IC50 = 0.29 ± 0.02 μM | |||

| Protein | MAP 30 | Not mentioned | No detectable toxic effect on WI-38 Cells HSV-1 ACVr DM21 EC50 = 0.1 μM HSV-1 ACVr PAAr EC50 = 0.1 μM HSV-2 ACVr Kost EC50 = 0.3 μM HSV-2 ACVr 8,708 EC50 = 0.3 μM | Not mentioned | Bourinbaiar and Lee-Huang, 1996 |

| GAP31 | Not mentioned | No detectable toxic effect on WI-38 Cells HSV-1 ACVr DM21 EC50 = 0.5 μM HSV-1 ACVr PAAr EC50 = 0.5 μM HSV-2 ACVr Kost EC50 = 0.6 μM HSV-2 ACVr 8,708 EC50 = 0.8 μM | |||

| Cyanovirin-N | Not mentioned | Vero Cells CC50 = 1.456 ± 0.340 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 IC50 = 0.014 ± 0.002 μM, SI = 104.00 HSV-1 ACVr Blue IC50 = 0.010 ± 0.003 μM, SI = 145.60 HSV-1 ACVr 106 IC50 = 0.030 ± 0.013 μM, SI = 48.53 | Inhibition of viral entry | Lei et al., 2019 | |

| LCV-N | Not mentioned | Vero Cells CC50 = 1.747 ± 0.097 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 IC50 = 0.007 ± 0.001 μM, SI = 249.57 HSV-1 ACVr Blue IC50 = 0.005 ± 0.001 μM, SI = 349.40 HSV-1 ACVr 106 IC50 = 0.022 ± 0.003 μM, SI = 79.41 | Not detected | ||

| PEG10k-LCV-N | Not mentioned | Vero Cells CC50 = 9.48 ± 1.403 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 IC50 = 0.181 ± 0.047 μM, SI = 52.30 HSV-1 ACVr Blue IC50 = 0.218 ± 0.008 μM, SI = 43.48 HSV-1 ACVr 106 IC50 = 0.642 ± 0.028 μM, SI = 14.76 | Virucidal activity | ||

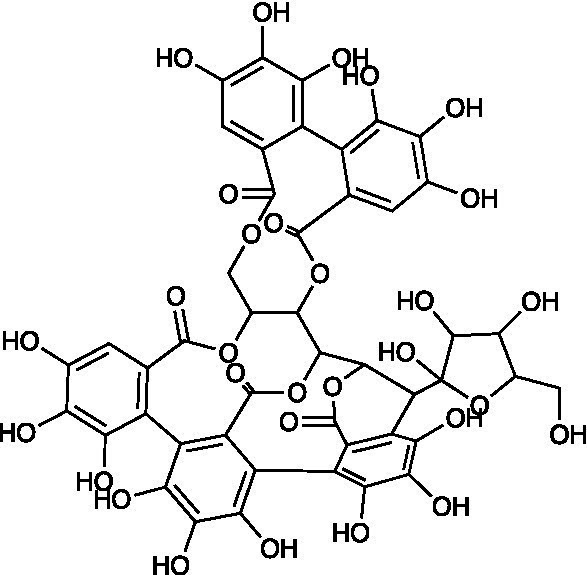

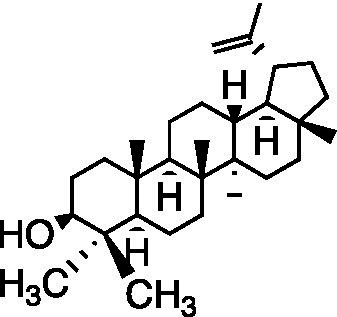

| Pentacyclic triterpenoid | Oleanolic acid |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 39.05 ± 0.561 μM SH-SY5Y Cells CC50 = 20.5 ± 0.325 μM HaCaT Cells CC50 = 37.06 ± 0.401 μM HSV-1 ACVr 153 EC50 = 13.06 ± 0.512 μM HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 13.09 ± 0.642 μM HSV-1 ACVr 106 EC50 = 12.89 ± 0.681 μM | Inhibition of the immediate early stage of infection targeting UL8 | Shan et al., 2021 |

| Polysaccharide | EGP | Not mentioned | Vero Cells CC50 > 1,000 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 153 EC50 = 1.24 ± 0.32 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr Blue EC50 = 1.48 ± 0.31 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr 106 EC50 = 1.11 ± 0.27 μg/ml | Inhibition of the early stages of viral infection and viral biosynthesis | Jin et al., 2015 |

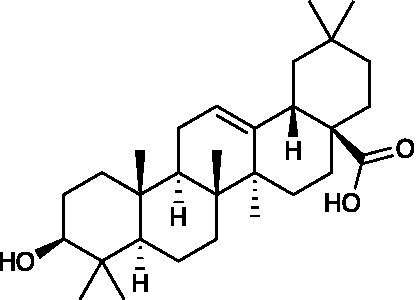

| Terpene | Betulin |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 = 22 μg/ml | Virucidal effect | Heidary Navid et al., 2014 |

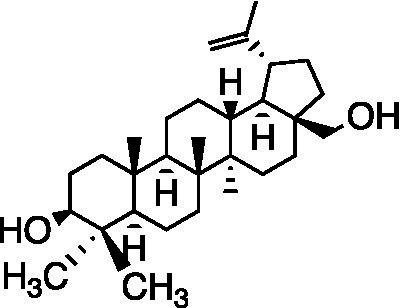

| Lupeol |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 = 5 μg/ml | |||

| Betulinic acid |

|

RC-37 Cells CC50 = 5 μg/ml | |||

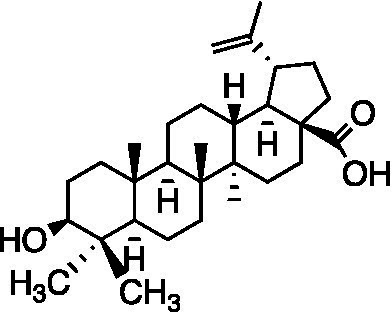

| IPAD |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 39.71 μM HSV-1 ACVr ACGr4 IC50 = 17.89 μM, SI = 2.22 HSV-1 ACVr dlsptk IC50 = 16.86 μM, SI = 2.36 HSV-1 ACVr dxplll IC50 = 17.12 μM, SI = 2.32 | Inhibition of viral biosynthesis | Priengprom et al., 2015 | |

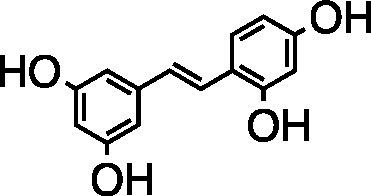

| Stilbenoid | Oxyresveratrol |

|

Vero Cells CC50 = 237.5 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr TK-deficient IC50 = 25.5 ± 1.5 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr PAAr IC50 = 21.7 ± 2.6 μg/ml | Inhibition of late protein production (gD, gC) | Chuanasa et al., 2008 |

| Xanthone | Mangiferin |

|

Vero Cells CC50 > 500 μg/ml HSV-1 ACVr AR-29 IC50 = 2.9 μg/ml | Virucidal effect; Inhibition of viral adsorption | Rechenchoski et al., 2020 |

EC50: half-maximal effective concentration; CC50: half-maximal cytotoxic concentration; IC50: half maximal inhibitory concentration; TC50: half toxic concentration; SI: selectivity index; SI50: selectivity index (SI=SI50); MNTC: maximum nontoxic concentration; VI: virucidal index; PI: percentage of inhibition; VII: viral inhibition index.

Medicinal plant extracts with anti-herpes simplex virus activities

The crude hydroethanolic extract (RCE40) from the leaves of Cecropia glaziovii Senthl. inhibited the replication of HSV-1 ACVr strain 29R, with an EC50 of 40 μg/ml and a selectivity index (SI) of 50. The antiherpes properties of RCE40 might be attributed to their phenolic composition (Petronilho et al., 2012).

The water extract of Cocos nucifera L. husk fiber that is rich in catechin exhibited inhibitory activity against HSV-1 ACVr. The fraction exhibited higher antiviral activity than the crude extract. Mechanistically, the antiviral activity has been attributed to inactivating the extracellular virus with a vircidual effect (Esquenazi et al., 2002). Furthermore, extracts containing catechin and condensed tannins have been reported to inhibit HSV adsorption and replication (De Bruyne et al., 1999; Serkedjieva and Ivancheva, 1999).

Peppermint oil, an essential oil extracted from the leaves of Mentha piperita L., mainly consists of methanol (42.8%), menthone (14.6%), isomenthone (5.9%), menthylacetate (4.4%), cineole (3.8%), limonene (1.2%) and carvone (0.6%). Peppermint oil inhibited HSV-1, HSV-2, and HSV-1 ACVr infection in a dose- and time-dependent manner. It showed an obvious virucidal effect when mixed with HSV prior to infection, which implies its direct interaction with the viral envelope and glycoproteins (Schuhmacher et al., 2003). This finding suggests that peppermint oil might be used topically as a virucidal agent in the treatment of recurrent herpes infections.

Viracea, a proprietary formula, is a blend of benzalkonium chloride and phytochemicals derived from the aerial parts of Echinacea purpurea, which was found to have significant antiviral activity against 25 different ACV-susceptible strains (13 strains of HSV-1 and 12 strains of HSV-2) and 15 ACV-resistant strains (5 strains of HSV-1 and 10 strains of HSV-2), with a therapeutic index in the range of 50–100. Instead of benzalkonium chloride, which was speculated to be a stabilizer, the phytochemicals had anti-HSV activity after the adsorption and penetration step (Thompson, 1998).

Lamiaceae ethanolic extracts from Prunella vulgaris L., dried leaves of Mentha × piperita L., Rosmarinus officinalis L., and dried herbs of Thymus vulgaris L. inhibited the infectivity of ACV-susceptible strains and HSV-1 ACVr strain Angelotti (ACV-resistant with a single point mutant in the DNA polymerase gene) and 1246/99 (ACV-resistant patient isolate with a single point mutant in the coding sequence of the TK gene) with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 0.05–0.82 μg/ml, which exerted the potential topical antiviral effect in the treatment of recurrent herpes labialis. Time-on-addition assays suggested that 80% prunella and peppermint ethanolic extracts had direct inactivation of free HSV particles and suppression of virus attachment to host cells. Additionally, the antiherpetic activity of the extracts was thought to be related to the amount and composition of phenolics in the plants (Reichling et al., 2008).

The polysaccharide from Eucheuma gelatinae (EGP) had comprehensive antiviral activity not only for standard experimental strains but also for clinical HSV-1 ACVr strains 106 (ACV-resistant with TK mutant), 153 (ACV-resistant with TK mutant), and Blue (ACV-resistant with TK deletion). EGP exerted its antiviral activities mainly in the early stages of HSV-1 infection, involving direct inactivation of the virions and interference in virus adsorption as a consequence of interactions between EGP and viral glycoproteins. The PCR results showed that the RNA synthesis of the HSV-1 early gene UL52 and the late gene UL27 was suppressed by EGP. In addition, the intracellular genome copy number in the EGP-treated group significantly declined, indicating that EGP inhibited viral DNA synthesis. In addition, EGP not only suppressed the synthesis of HSV-1 capsid protein VP5 but also affected cellular localization through indirect immunofluorescence and Western blot assays (Jin et al., 2015).

Essential oils from ginger (Zingiber officinale), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis), and sandalwood (Santalum album) are complex mixtures of low-molecular-weight molecules and the active components of lipophilic carbohydrates. EO inhibited the infection of HSV-1 ACVr strains 1246/99, Angelotti, and 496/02 (ACV-resistant patient isolate with a single point mutant in the coding sequence of the TK gene). The essential oils prior to infection caused significant reductions in infectivity and proved their virucidal activity by adding the oils at different times during the HSV infection cycle (Schnitzler et al., 2007). In addition, the essential oil from Salvia desoleana Atzei & V. Picci, which contains linalyl acetate and alpha terpinyl acetate, suppressed both HSV-2 and HSV-2 ACVr in the postinfection stage. It revealed that the EO might interfere with later steps of the virus replication cycle (e.g., uncoating, genome replication, virus assembly or exit, cell-to-cell spread) by virus inactivation and time-of-addition assays (Cagno et al., 2017). The antiviral effect of EO was totally due to the active fraction SD1, which was characterized by mono- and sesquiterpene hydrocarbons. Considering the limitation that short-term systemic bioavailability of the essential oils and high effective dosage might lead to cytotoxicity, other anti-HSV agents should be added alongside topical treatment against recurrent infection.

Acacia nilotica (L.) has been used as a traditional healer to treat sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as syphilis, gonorrhea, and other HIV/AIDS-related diseases (Kambizi and Afolayan, 2001; Chinsembu, 2016). The methanolic extract of Vachellia nilotica, known by the taxonomic synonym A. nilotica, exerted antiviral activity against HSV-2 and HSV-2 ACVr. The methanolic bark extract, which was mostly composed of saponins and flavonoids with traces of tannins, exerted a dual-mode of action against HSV-2 infection, which interfered with early steps of the virus replication cycle instead of targeting the cell surface, including inactivation of virus extracellular particles and inhibition of virus attachment (Donalisio et al., 2018).

Vitex polygama Cham. is used as a diuretic in traditional medicine. The flavonoid-rich ethyl acetate extract of Vitex polygama Cham. possessed potential activity against HSV-1 ACVr, the leaf extract possessed the most pronounced antiviral ability by inhibiting intracellular spread, and the fruit extract exhibited a virucidal effect. VPAF-1, the fraction further extracted with organic reagents, was proven to reduce viral propagation by preventing HSV-1 ACVr from attaching to cellular receptors (Goncalves et al., 2001).

Ficus religiosa L. belongs to the genus Moraceae and is used to treat diabetes, inflammation, and sexually transmitted infections (Singh et al., 2011; Choudhari et al., 2013). The water bark extract of this plant effectively exhibited a virucidal effect against both HSV-2 MS (ACV-sensitive) and HSV-2 ACVr strain replication. The chloroform extract inhibited the early stage of the HSV-2 replicative cycle and interfered with viral attachment and penetration through the time-of-addition assay and attachment assay. In addition, the chloroform extract limited the production of viral progeny based on the result of the viral yield reduction assay (Ghosh et al., 2016). These findings suggest that bioactive metabolites of F. religiosa were identified as natural therapeutic substances for genital herpes, especially in HSV-2 ACVr strains.

The sulfated polysaccharide fraction, which is isolated from the hot water extract of Caulerpa racemose (HWE), has a molecular weight of 5–10 kDa and more than two SO3− groups for each sugar residue. HWE exhibited anti-herpetic activity against HSV-1/F, HSV-2/G, and HSV-1 ACVr strain B2006 (ACV-resistant with TK deficient) and field (ACV-resistant with TK deficient), with EC50 values in the range of 2.2–4.2 μg/ml, without any cytotoxic effects (Ghosh et al., 2004).

The Prunella vulgaris polysaccharide fraction (PPV) significantly reduced the antigen expression of both ACV-sensitive HSV and HSV-1 ACVr strain DM2.1 (ACV-resistant with TK deficiency) according to immunostaining and flow cytometric analyses of HSV-1 and HSV-2 antigens (Chiu et al., 2004). An anionic polysaccharide from Prunella vulgaris (PVP), which was isolated by hot water extraction, ethanol precipitation, and gel permeation column chromatography, was reported to possess anti-HSV activity against HSV-1 ACVr strain DM2.1 and PAAr (ACV-resistant with DNA polymerase mutant) and HSV-2 ACVr strain Kost (ACV-resistant with TK altered). According to the viral binding assay, PVP could compete with cell receptors to exert its inhibitory effect (Xu et al., 1999). These investigations provide the possibility that P. vulgaris developed as a self-applicable ointment for cold sores and genital herpes.

Houttuynia cordata is an herbal medicine of the family Saururaceae that shows anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antioxidative activities (Chen et al., 2003; Lu et al., 2006), as well as antiviral activity against influenza virus, SARS-CoV, and HSV (Lau et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011). The water extracts of H. cordata (HCWEs) showed low cytotoxicity in Vero cells and inhibited HSV-1 ACVr strain AR (ACV-resistant with TK mutant) infection. The molecular mechanisms of HCWEs involve anti-HSV activity through inhibition of viral entry, interfering with viral replication by suppressing viral late genes, and inhibiting HSV-induced NF-κB activation (Hung et al., 2015).

The study investigated the antiviral activity of the extract of Arisaema tortuosum (Wall.) Schott leaves, which have a medicinal history in India to treat piles, snake bites, and parasitic infections. Comparing seven fractions extracted by different solvents, chloroform extract (CE) exhibited the greatest antiviral activity against HSV-2 ACVr strains by inhibiting viral attachment and entry as well as the late steps in the replication cycle. The main components identified by HPLC-PDA-MS/MS analysis are apigenin and luteolin, which inhibit cell-to-cell virus spread and the production of viral progeny (Ritta et al., 2020).

Table 2 concluded the medicinal plant extracts mentioned in this review with their families, extract solvent, and antiviral efficacy (including the IC50, EC50, and mode of action).

Bioactive components that show anti-herpes simplex virus activities

Terpenes

Andrographolide and its derivatives were confirmed to have antiviral activities against HIV, HBV, and HSV by interacting with viral receptors, coreceptors, and enzymes related to viral replication (Jadhav and Karuppayil, 2021). 3,19-isopropylideneandrographolide (IPAD) is an andrographolide analog isolated from Andrographis paniculata Nees. IPAD exerted an inhibitory effect against both HSV wild types (HSV-1 and HSV-2) and HSV-1 ACVr strain ACGr4 (ACV-resistant with TK deficiency), dlsptk (ACV-resistant with TK deletion), and dxpIII (phosphonoacetic acid and phosphonoformate resistance). The inhibitory effects of IPAD are involved in the replication cycle by inhibiting the synthesis of viral DNA and the late protein gD. Furthermore, the synergistic effects of ACV and IPAD on HSV wild types and HSV-1 ACVr were determined by CPE reduction assay (Priengprom et al., 2015). The triterpene extract (TE) of birch bark and its major pentacyclic triterpenes (betulin, lupeol, and betulinic acid) were found to be active in suppressing HSV-1 strain KOS and two clinical isolates HSV-1 ACVr in a dose-dependent manner using plaque reduction assays. Unlike ACV, TE, and triterpenes achieved minor virucidal activity and antiviral effects in the early phase of infection (Heidary Navid et al., 2014).

Oleanolic acid, a pentacyclic triterpenoid that widely exists in natural products, possesses antitumor, anti-inflammatory, and hepatoprotective activities (Baer-Dubowska et al., 2021; Hosny et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Oleanolic acid exerted potent antiviral activity against the ACV-sensitive strain HSV-1/F and three HSV-1 ACVr strains (Blue, 106 and 153). Mechanistic studies demonstrated that oleanolic acid suppressed viral replication by downregulating the mRNA expression of the viral helicase-primase complex that is composed of UL5, UL52, and UL8. The in vivo study carried out on the HSV-1-infected zosteriform model suggested that oleanolic acid relieved skin lesions (Shan et al., 2021), which indicated that oleanolic acid could be a promising therapeutic target for HSV-1-related skin lesions, particularly in ACV-resistant individuals.

Phenolics

The essential oil of Lippia graveolens (Mexican oregano) inhibited the infection of ACV-sensitive HSV-1 and HSV-1 ACVr strains at different time points of viral replication. The main component carvacrol exhibited more significant antiviral activity only when the cells were post-treated, with a different mode of action as essential oil (Pilau et al., 2011).

Melissa officinalis (lemon balm), belonging to the Lamiaceae family, is reported to exert antioxidant and antibacterial effects (Canadanović-Brunet et al., 2008). The aqueous extract of Melissa officinalis interfered with the early steps of virus replication against both HSV-1 KOS and two clinical isolates of HSV-1 ACVr strains. Among the phenolic compounds isolated from Melissa leaves, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, and rosmarinic acid were the main contributors by inactivating the virus and inhibiting virus attachment and penetration (Astani et al., 2014).

Ellagitannins are plant-derived polyphenol compounds with pharmacological activities, including antitumor and antibacterial activities (Ismail et al., 2016; Puljula et al., 2020). Three ellagitannins (castalagin, vescalagin, and grandinin) were proven to exhibit antiviral effects against HSV-1 ACVr strain R-100 (ACV-resistant with a TK enzyme-encoding gene mutant) and HSV-2 ACVr strain PU (ACV-resistant with TK deficiency) through the focus forming units (FFU) reduction test and CPE inhibition test. In addition, the tested ellagitannins had combined effects with ACV on the replication of HSV-1 ACVr and HSV-2 ACVr strains, and the inhibitory mechanism was different from ACV (Vilhelmova-Ilieva et al., 2014).

Xanthones

Mangiferin, a polyphenol with a C-glycosylxanthone structure, can be discovered in mango trees (Mangifera indica) and is used as a treatment for burns and pruritus and exerts neuroprotective effects (Lee et al., 2009; Liu T. et al., 2021). Mangiferin was reported to have great in vitro and in vivo antiviral activity against HSV-1 ACVr strain AR-29 and HSV-1 strain KOS with low toxicity. Further mechanistic studies showed that mangiferin exerted its antiherpetic effect mainly by exerting a virucidal effect and inhibiting viral adsorption (Rechenchoski et al., 2020).

Cardenolides

Cardiac glycosides are naturally derived compounds and are widely used in the treatment of heart failure (Kelly, 1990). After screening 65 cardenolide derivatives, the natural cardenolide compound glucoevatromonoside, which was isolated from the Brazilian cultivar of Digitalis lanata, exhibited potent anti-HSV activity against the HSV-1 strain KOS, HSV-2 strain 333, and HSV-1 ACVr strain 29R with low IC50 values of 0.13 ± 0.01, 0.04 ± 0.00, and 0.06 ± 0.01 μM, respectively. It reduced the expression of the viral proteins ICP27, UL42, gB, and gD by downregulating the K+ concentration into cells that is essential for viral protein synthesis, thus interfering with virus release and viral spread (Bertol et al., 2011).

Flavonoids

Amentoflavone (AF), a naturally existing biflavonoid, was proven to exert antiviral activity against HSV-1 strain F and three HSV-1 ACVr strains (Blue, 106 and 153) through CPE and plaque assays. Mechanistically, AF completely reduced viral gene production (UL54, UL52, and UL27) and protein levels (ICP0, gD, and VP5) of HSV-1 strain F and three HSV ACVr strains. Furthermore, AF affected cofilin-mediated F-actin remodeling, which was essential for HSV-1 viral entry and reduction of viral nuclear transport (Li et al., 2019).

4’-Phenylflavone is a synthetic flavonoid that exerted antiviral activity against HSV-1 strain KOS, HSV-2 strain UW 268, and HSV-1 ACVr strain A4-3 (ACV-resistant with TK deletion) in vitro and in vivo by interfering with late stages in viral replication and reducing the release of progeny viruses. Synergistic therapy with 4′-phenylflavone and ACV remarkably improved the lesion scores and survival rates of HSV-infected mice, indicating the antiherpetic effect of the drug combination (Hayashi et al., 2012).

Soybean (Glycine max) isoflavonoids have great biological activity related to estrogenic responses. Genistein and coumestrol inhibited the infection of HSV-1 strain KOS, HSV-2 strain 333, and HSV-1 ACVr strain 29R. Coumestrol affected multiple steps in the HSV replication cycle, including adsorption and penetration, by reducing the expression of the viral proteins UL42 and gD. In comparison, genistein showed no effect on early stages but reduced the expression of viral proteins UL42, gD, and ICP27 (Argenta et al., 2015).

Baicalein is a flavonoid isolated from the root of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi with biological activity against cancer and inflammatory diseases. Baicalein inhibited the replication of both HSV-1 strain F and HSV-1 ACVr strain Blue in Vero and HaCaT cells. Further mechanistic analysis elucidated that baicalein inactivated viral particles and suppressed NF-κB activation, which contributed to the protective effect of baicalein on HSV-1 infection. Furthermore, oral administration of baicalein also reduced HSV-1-induced lethality and viral loads and ameliorated symptoms in both the nose and trigeminal ganglia in an HSV-1 intranasal infection model (Luo et al., 2020).

Proteins

MAP30 and GAP31 were derived from the Himalayan tree Gelonium multiflorum and Chinese bitter melon Momordica charantia. These two proteins were found to be effective in inhibiting the HSV-1 ACVr strain DM21 and PAAr and the HSV-2 ACVr strain Kost (ACV-resistant with TK altered) and 8,708 (ACV-resistant with TK altered) without toxicity to human embryonic cells. However, the detailed mechanism remains to be defined (Bourinbaiar and Lee-Huang, 1996).

Cyanovirin-N (CV-N), the cyanobacterial protein isolated from Nostoc ellipsosporum, and its two chemically modified derivatives LCV-N and PEG10k-LCV-N were reported to possess antiviral activity against HSV-1 ACVr strains 153, Blue, and 106. According to the WST-8 assay, PEG10k-LCV-N had the lowest cytotoxicity, but it showed reduced activity against ACV-resistant HSV strains compared with CV-N and LCV-N, and the detailed mechanism still needs to be explored. However, the anti-HSV-1 potency of CV-N was confirmed due to the presence of an intact sugar binding site on the BM domain for viral glycoprotein interaction, which suggests that it is a viral entry inhibitor of HSV-1 and HIV (Barrientos et al., 2006; Xiong et al., 2010; Lei et al., 2019).

Alkaloids

Caffeine inhibited the plaque formation of HSV-2 and HSV-1 ACVr strain B2006 (TK deficient) and PAAv in vitro. Caffeine gel treatment decelerated the development of skin lesions in mice caused by HSV-2 and reduced the virus yield of the skin infected with ACV-resistant HSV-1 strains in vivo (Yoshida et al., 1996).

Harringtonine (HT), a natural alkaloid isolated from Cephalotaxus harringtonia, possessed antiviral effects against two HSV-1 ACVr strains (Blue and 153) and three ACV-sensitive strains. A further study showed that HT reduced the expression of HVEM, thereby affecting viral membrane fusion and viral entry (Liu Y. et al., 2021).

Transdihydrolycoricidine (R430) is a lycorane-type alkaloid derivative from the Amaryllidaceae family that showed more potent antiviral activity against HSV-1 ACVr strains TK mutant and PAAr compared to ACV. R430 influenced the early stages of the HSV-1 lytic phase principally by reducing the transcription and translation of the viral immediate early (IE) gene ICP4 and DNA polymerase, which may be a consequence of upregulation of STAT3 (D'Aiuto et al., 2018).

Steroids

Artocarpus lakoocha is used to treat HSV and varicella-zoster virus infection (Sangkitporn et al., 1995). Oxyresveratrol obtained from the heartwood of Artocarpus lakoocha Roxburgh exhibited antiherpes activity against HSV-1 strain 7401H and HSV-1 ACVr strain B2006 (ACV-resistant with TK deficiency) and PAAv by inhibiting the early gene products ICP6 and ICP8 as well as the late viral proteins gC and gD. The combination of oxyresveratrol and ACV showed a synergistic effect against HSV-1 according to isobologram analysis. In addition, 30% oxyresveratrol ointment treatment prolonged the survival rate and delayed mouse skin lesion development in HSV-1-infected mice (Chuanasa et al., 2008).

Peptides

Aspergillipeptide D is a cyclic pentapeptide isolated from the fungal strain Aspergillus SCSIO 41501. Aspergillipeptide D exerted a significant antiviral effect against three HSV-1 ACVr strains, Blue, 153, and 106, by reducing the mRNA expression of UL27 and the late viral gB protein encoded by UL27. Furthermore, Aspergillipeptide D interfered with the expression and localization of gB in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus, suggesting that it mainly affected gB in viral intercellular spread instead of viral entry (Wang et al., 2020).

Table 3 summarized phytochemicals mentioned in this review with their chemical class, structure and activity against ACV-resistant HSV strains (including the IC50, EC50 and the mode of action).

Conclusion

HSV infection is an urgent public health issue. The nucleoside analog ACV is the most effective clinical treatment that interferes with viral replication and alleviates HSV infection. However, excessive and prolonged use of ACV has led to the emergence of ACV-resistant HSV strains. Thus, it is urgent to develop an effective antiviral therapy with low toxicity to handle ACV-resistant strains (Li et al., 2022). In this review, medicinal plant extracts from 13 families, including Araceae, Asteraceae, Caulerpaceae, Cecropiaceae, Fabaceae, Lamiaceae, and Moraceae, and phytochemicals such as alkaloids, flavonoids, phenolics, terpenes and others, were concluded to exert antiviral properties against ACV-resistant HSV infection, and the mechanism of action were summarized in Figure 1. Most plant extracts that can inhibit ACV-resistant HSV infection are classified into heat-clearing and detoxifying drugs in Traditional Chinese Medicine, with a history of external use to treat sores. The majority of the active components exerted virucidal effects and viral entry inhibition, including blocking viral attachment and fusion. In addition, some phytomedicines prevented the intranuclear biosynthesis of viral proteins and cellular reinfection by progeny viruses. Nevertheless, only a few substances interfered with nuclear transportation and virion egress. In contrast to ACV, these natural products mainly interfered with the early stages of the HSV replication cycle rather than the later stages, demonstrating their potential to treat ACV-resistant HSV infection. Unfortunately, there is no candidate in clinical development or in clinical use against ACV-resistant HSV infection.

Overall, the medicinal plant and phytomedicines mentioned in this review might be promising options for treating ACV-resistant HSV infection, although further studies are needed to exploit sufficient theoretical support for antiviral therapy, such as structure optimization, the synergistic effect of medicinal plants and ACV, and confirmation of the evidence from in vitro and animal-based studies.

Author contributions

LX and X-LZ equally contributed to the development of this manuscript. Z-CX assisted to revise the manuscript. All authors wrote the manuscript and designed the tables in the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82204437), NSFC-Joint Foundation of Yunnan Province (No. U1902213), Shanghai science and technology innovation action plan (No. 22YF1445100), and Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No. 2020B1111110003).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Argenta D. F., Silva I. T., Bassani V. L., Koester L. S., Teixeira H. F., Simoes C. M. (2015). Antiherpes evaluation of soybean isoflavonoids. Arch. Virol. 160, 2335–2342. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2514-z, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astani A., Navid M. H., Schnitzler P. (2014). Attachment and penetration of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus are inhibited by Melissa officinalis extract. Phytother. Res. 28, 1547–1552. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5166, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer-Dubowska W., Narożna M., Krajka-Kuźniak V. (2021). Anti-cancer potential of synthetic Oleanolic acid derivatives and their conjugates with NSAIDs. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 26:4957. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164957, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos L. G., Matei E., Lasala F., Delgado R., Gronenborn A. M. (2006). Dissecting carbohydrate-Cyanovirin-N binding by structure-guided mutagenesis: functional implications for viral entry inhibition. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 19, 525–535. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl040, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertol J. W., Rigotto C., de Padua R. M., Kreis W., Barardi C. R., Braga F. C., et al. (2011). Antiherpes activity of glucoevatromonoside, a cardenolide isolated from a Brazilian cultivar of Digitalis lanata. Antivir. Res. 92, 73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.06.015, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinbaiar A. S., Lee-Huang S. (1996). The activity of plant-derived antiretroviral proteins MAP30 and GAP31 against herpes simplex virus in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 219, 923–929. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0334, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigden D., Whiteman P. (1983). The mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of acyclovir--a review. J. Infect. 6, 3–9, The mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics and toxicity of acyclovir — a review, doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(83)94041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagno V., Sgorbini B., Sanna C., Cagliero C., Ballero M., Civra A., et al. (2017). In vitro anti-herpes simplex virus-2 activity of salvia desoleana Atzei & V. Picci essential oil. PLoS One 12:e0172322. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172322, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadanović-Brunet J., Cetković G., Djilas S., Tumbas V., Bogdanović G., Mandić A., et al. (2008). Radical scavenging, antibacterial, and antiproliferative activities of Melissa officinalis L. extracts. J. Med. Food 11, 133–143. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2007.580, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wang Z., Yang Z., Wang J., Xu Y., Tan R. X., et al. (2011). Houttuynia cordata blocks HSV infection through inhibition of NF-kappa B activation. Antivir. Res. 92, 341–345. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.09.005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y. Y., Liu J. F., Chen C. M., Chao P. Y., Chang T. J. (2003). A study of the antioxidative and antimutagenic effects of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. Using an oxidized frying oil-fed model. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo) 49, 327–333. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.49.327, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinsembu K. C. (2016). Ethnobotanical study of plants used in the management of HIV/AIDS-related diseases in Livingstone, Southern Province, Zambia. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2016, 4238625–4238614. doi: 10.1155/2016/4238625, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu L. C., Zhu W., Ooi V. E. (2004). A polysaccharide fraction from medicinal herb Prunella vulgaris downregulates the expression of herpes simplex virus antigen in Vero cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 93, 63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.03.024, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. J., Song J. H., Park K. S., Kwon D. H. (2009). Inhibitory effects of quercetin 3-rhamnoside on influenza a virus replication. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 37, 329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.03.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhari A. S., Suryavanshi S. A., Kaul-Ghanekar R. (2013). The aqueous extract of Ficus religiosa induces cell cycle arrest in human cervical cancer cell lines SiHa (HPV-16 positive) and apoptosis in HeLa (HPV-18 positive). PLoS One 8:e70127. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070127, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuanasa T., Phromjai J., Lipipun V., Likhitwitayawuid K., Suzuki M., Pramyothin P., et al. (2008). Anti-herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) activity of oxyresveratrol derived from Thai medicinal plant: mechanism of action and therapeutic efficacy on cutaneous HSV-1 infection in mice. Antivir. Res. 80, 62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.05.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen F., Kemeny M. E., Kearney K. A., Zegans L. S., Neuhaus J. M., Conant M. A. (1999). Persistent stress as a predictor of genital herpes recurrence. Arch. Intern. Med. 159, 2430–2436. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.20.2430, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aiuto L., McNulty J., Hartline C., Demers M., Kalkeri R., Wood J., et al. (2018). R430: a potent inhibitor of DNA and RNA viruses. Sci. Rep. 8:16662. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33904-y, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruyne T., Pieters L., Witvrouw M., De Clercq E., Vanden Berghe D., Vlietinck A. J. (1999). Biological evaluation of proanthocyanidin dimers and related polyphenols. J. Nat. Prod. 62, 954–958. doi: 10.1021/np980481o, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donalisio M., Cagno V., Civra A., Gibellini D., Musumeci G., Ritta M., et al. (2018). The traditional use of Vachellia nilotica for sexually transmitted diseases is substantiated by the antiviral activity of its bark extract against sexually transmitted viruses. J. Ethnopharmacol. 213, 403–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.11.039, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donalisio M., Nana H. M., Ngane R. A., Gatsing D., Tchinda A. T., Rovito R., et al. (2013). In vitro anti-herpes simplex virus activity of crude extract of the roots of Nauclea latifolia smith (Rubiaceae). BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 13:266. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-266, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbs D. R., Kit S. (1964). Mutant strains of herpes simplex deficient in thymidine kinase-inducing activity. Virology 22, 493–502. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(64)90070-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou S., Kemp S., Darby G., Minson A. C. (1989). The role of herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase in pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 70, 869–879. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-4-869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquenazi D., Wigg M. D., Miranda M. M., Rodrigues H. M., Tostes J. B., Rozental S., et al. (2002). Antimicrobial and antiviral activities of polyphenolics from Cocos nucifera Linn. (Palmae) husk fiber extract. Res. Microbiol. 153, 647–652. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(02)01377-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field H. J. (2001). Herpes simplex virus antiviral drug resistance--current trends and future prospects. Journal of Clinical Virology : the Official Publication of the Pan American Society For Clinical Virology 21, 261–269. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(00)00169-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M., Civra A., Ritta M., Cagno V., Mavuduru S. G., Awasthi P., et al. (2016). Ficus religiosa L. bark extracts inhibit infection by herpes simplex virus type 2 in vitro. Arch. Virol. 161, 3509–3514. doi: 10.1007/s00705-016-3032-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh P., Adhikari U., Ghosal P. K., Pujol C. A., Carlucci M. J., Damonte E. B., et al. (2004). In vitro anti-herpetic activity of sulfated polysaccharide fractions from Caulerpa racemosa. Phytochemistry 65, 3151–3157. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.07.025, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves J. L., Leitao S. G., Monache F. D., Miranda M. M., Santos M. G., Romanos M. T., et al. (2001). In vitro antiviral effect of flavonoid-rich extracts of Vitex polygama (Verbenaceae) against acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus type 1. Phytomedicine 8, 477–480. doi: 10.1078/S0944-7113(04)70069-0, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Hayashi T., Otsuka H., Takeda Y. (1997). Antiviral activity of 5,6,7-trimethoxyflavone and its potentiation of the antiherpes activity of acyclovir. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39, 821–824. doi: 10.1093/jac/39.6.821, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K., Iinuma M., Sasaki K., Hayashi T. (2012). In vitro and in vivo evaluation of a novel antiherpetic flavonoid, 4′-phenylflavone, and its synergistic actions with acyclovir. Arch. Virol. 157, 1489–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1335-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidary Navid M., Laszczyk-Lauer M. N., Reichling J., Schnitzler P. (2014). Pentacyclic triterpenes in birch bark extract inhibit early step of herpes simplex virus type 1 replication. Phytomedicine 21, 1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2014.06.007, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honess R. W., Watson D. H. (1977). Herpes simplex virus resistance and sensitivity to phosphonoacetic acid. J. Virol. 21, 584–600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.21.2.584-600.1977, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosny S., Sahyon H., Youssef M., Negm A. (2021). Oleanolic acid suppressed DMBA-induced liver carcinogenesis through induction of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis and autophagy. Nutr. Cancer 73, 968–982. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2020.1776887, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung P. Y., Ho B. C., Lee S. Y., Chang S. Y., Kao C. L., Lee S. S., et al. (2015). Houttuynia cordata targets the beginning stage of herpes simplex virus infection. PLoS One 10:e0115475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115475, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail T., Calcabrini C., Diaz A. R., Fimognari C., Turrini E., Catanzaro E., et al. (2016). Ellagitannins in cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Toxins 8:151. doi: 10.3390/toxins8050151, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav A. K., Karuppayil S. M. (2021). Andrographis paniculata (Burm. F) Wall ex Nees: antiviral properties. Phytother. Res. 35, 5365–5373. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7145, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F., Zhuo C., He Z., Wang H., Liu W., Zhang R., et al. (2015). Anti-herpes simplex virus activity of polysaccharides from Eucheuma gelatinae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 31, 453–460. doi: 10.1007/s11274-015-1798-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jofre J. T., Schaffer P. A., Parris D. S. (1977). Genetics of resistance to phosphonoacetic acid in strain KOS of herpes simplex virus type 1. J. Virol. 23, 833–836. doi: 10.1128/JVI.23.3.833-836.1977, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambizi L., Afolayan A. J. (2001). An ethnobotanical study of plants used for the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (njovhera) in Guruve District. Zimbabwe. J Ethnopharmacol 77, 5–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00251-3, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. A. (1990). Cardiac glycosides and congestive heart failure. Am. J. Cardiol. 65, E10–E16. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90245-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost R. G., Hill E. L., Tigges M., Straus S. E. (1993). Brief report: recurrent acyclovir-resistant genital herpes in an immunocompetent patient. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 1777–1782. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292405, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukhanova M. K., Korovina A. N., Kochetkov S. N. (2014). Human herpes simplex virus: life cycle and development of inhibitors. Biochemistry (Mosc) 79, 1635–1652. doi: 10.1134/S0006297914130124, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushch A. A., Kisteneva L. B., Klimova R. R., Cheshik S. G. (2021). The role of herpesviruses in development of diseases of the urogenital tract and infertility in women. Vopr. Virusol. 65, 317–325. doi: 10.36233/0507-4088-2020-65-6-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K. M., Lee K. M., Koon C. M., Cheung C. S., Lau C. P., Ho H. M., et al. (2008). Immunomodulatory and anti-SARS activities of Houttuynia cordata. J. Ethnopharmacol. 118, 79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.03.018, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B., Trung Trinh H., Bae E.-A., Jung K., Kim D.-H. (2009). Mangiferin inhibits passive cutaneous anaphylaxis reaction and pruritus in mice. Planta Med. 75, 1415–1417. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185773, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Y., Chen W., Liang H., Wang Z., Chen J., Hong H., et al. (2019). Preparation of a monoPEGylated derivative of cyanovirin-N and its virucidal effect on acyclovir-resistant strains of herpes simplex virus type 1. Arch. Virol. 164, 1259–1269. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-04118-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Song X., Su G., Wang Y., Wang Z., Jia J., et al. (2019). Amentoflavone inhibits HSV-1 and ACV-resistant strain infection by suppressing viral early infection. Viruses 11:466. doi: 10.3390/v11050466, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Wei W., Xu H. (2022). Drug discovery is an eternal challenge for the biomedical sciences. Acta Materia Medica. 1, 1–3. doi: 10.15212/AMM-2022-1001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Song Y., Hu A. (2021). Neuroprotective mechanisms of mangiferin in neurodegenerative diseases. Drug Dev. Res. 82, 494–502. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21783, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., You Q., Zhang F., Chen D., Huang Z., Wu Z. (2021). Harringtonine inhibits herpes simplex virus type 1 infection by reducing herpes virus entry mediator expression. Front. Microbiol. 12:722748. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.722748, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H. M., Liang Y. Z., Yi L. Z., Wu X. J. (2006). Anti-inflammatory effect of Houttuynia cordata injection. J. Ethnopharmacol. 104, 245–249. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.09.012, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Kuang X. P., Zhou Q. Q., Yan C. Y., Li W., Gong H. B., et al. (2020). Inhibitory effects of baicalein against herpes simplex virus type 1. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 10, 2323–2338. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.06.008, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty J., D'Aiuto L., Zhi Y., McClain L., Zepeda-Velazquez C., Ler S., et al. (2016). iPSC neuronal assay identifies Amaryllidaceae pharmacophore with multiple effects against herpesvirus infections. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 7, 46–50. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00318, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfin F., Thouvenot D. (2003). Herpes simplex virus resistance to antiviral drugs. Journal of Clinical Virology : the Official Publication of the Pan American Society For Clinical Virology 26, 29–37. doi: 10.1016/S1386-6532(02)00263-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mues M. B., Cheshenko N., Wilson D. W., Gunther-Cummins L., Herold B. C. (2015). Dynasore disrupts trafficking of herpes simplex virus proteins. J. Virol. 89, 6673–6684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00636-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott A., Fohring B., Kaerner H. C. (1979). Herpes simplex virus type 1 Angelotti and a defective viral genotype: analysis of genome structures and genetic relatedness by DNA-DNA reassociation kinetics. J. Virol. 29, 423–430. doi: 10.1128/JVI.29.2.423-430.1979, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palu G., Summers W. P., Valisena S., Tognon M. (1988). Preliminary characterization of a mutant of herpes simplex virus type 1 selected for acycloguanosine resistance in vitro. J. Med. Virol. 24, 251–262. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890240303, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paluch Z., Trojanek M., Veliskova Z., Mlichova J., Chrbolka P., Gregorova J., et al. (2021). Neurotoxic side effects of acyclovir: two case reports. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 42, 375–382. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parris D. S., Courtney R. J., Schaffer P. A. (1978). Temperature-sensitive mutants of herpes simplex virus type 1 defective in transcriptional and post-transcriptional functions required for viral DNA synthesis. Virology 90, 177–186. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(78)90301-x, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petronilho F., Dal-Pizzol F., Costa G. M., Kappel V. D., de Oliveira S. Q., Fortunato J., et al. (2012). Hepatoprotective effects and HSV-1 activity of the hydroethanolic extract of Cecropia glaziovii (embauba-vermelha) against acyclovir-resistant strain. Pharm. Biol. 50, 911–918. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2011.643902, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilau M. R., Alves S. H., Weiblen R., Arenhart S., Cueto A. P., Lovato L. T. (2011). Antiviral activity of the Lippia graveolens (Mexican oregano) essential oil and its main compound carvacrol against human and animal viruses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 42, 1616–1624. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220110004000049, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priengprom T., Ekalaksananan T., Kongyingyoes B., Suebsasana S., Aromdee C., Pientong C. (2015). Synergistic effects of acyclovir and 3, 19-isopropylideneandrographolide on herpes simplex virus wild types and drug-resistant strains. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 15:56. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0591-x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puljula E., Walton G., Woodward M. J., Karonen M. (2020). Antimicrobial activities of Ellagitannins against , , and. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 25:3714. doi: 10.3390/molecules25163714, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rechenchoski D. Z., Agostinho K. F., Faccin-Galhardi L. C., Lonni A., da Silva J. V. H., de Andrade F. G., et al. (2020). Mangiferin: a promising natural xanthone from Mangifera indica for the control of acyclovir - resistant herpes simplex virus 1 infection. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 28:115304. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115304, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichling J., Nolkemper S., Stintzing F. C., Schnitzler P. (2008). Impact of ethanolic lamiaceae extracts on herpesvirus infectivity in cell culture. Forsch. Komplementmed. 15, 313–320. doi: 10.1159/000164690, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritta M., Marengo A., Civra A., Lembo D., Cagliero C., Kant K., et al. (2020). Antiviral activity of a Arisaema Tortuosum leaf extract and some of its constituents against herpes simplex virus type 2. Planta Med. 86, 267–275. doi: 10.1055/a-1087-8303, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangkitporn S., Chaiwat S., Balachandra K., Na-Ayudhaya T. D., Bunjob M., Jayavasu C. (1995). Treatment of herpes zoster with Clinacanthus nutans (bi phaya yaw) extract. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 78, 624–627. PMID: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler P., Koch C., Reichling J. (2007). Susceptibility of drug-resistant clinical herpes simplex virus type 1 strains to essential oils of ginger, thyme, hyssop, and sandalwood. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 1859–1862. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00426-06, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuhmacher A., Reichling J., Schnitzler P. (2003). Effect of peppermint oil on the enveloped viruses herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in vitro. Phytomedicine 10, 504–510. doi: 10.1078/094471103322331467, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkedjieva J., Ivancheva S. (1999). Antiherpes virus activity of extracts from the medicinal plant Geranium sanguineum L. J. Ethnopharmacol. 64, 59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00095-6, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan T., Ye J., Jia J., Wang Z., Jiang Y., Wang Y., et al. (2021). Viral UL8 is involved in the antiviral activity of Oleanolic acid against HSV-1 infection. Front. Microbiol. 12:689607. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.689607, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh D., Singh B., Goel R. K. (2011). Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Ficus religiosa: a review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 134, 565–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.01.046, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranska R., Schuurman R., Nienhuis E., Goedegebuure I. W., Polman M., Weel J. F., et al. (2005). Survey of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus in the Netherlands: prevalence and characterization. J. Clin. Virol. 32, 7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.04.002, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su C. T., Hsu J. T., Hsieh H. P., Lin P. H., Chen T. C., Kao C. L., et al. (2008). Anti-HSV activity of digitoxin and its possible mechanisms. Antivir. Res. 79, 62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.01.156, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K. D. (1998). Antiviral activity of Viracea against acyclovir susceptible and acyclovir resistant strains of herpes simplex virus. Antivir. Res. 39, 55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00027-8, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valyi-Nagy T., Gesser R. M., Raengsakulrach B., Deshmane S. L., Randazzo B. P., Dillner A. J., et al. (1994). A thymidine kinase-negative HSV-1 strain establishes a persistent infection in SCID mice that features uncontrolled peripheral replication but only marginal nervous system involvement. Virology 199, 484–490. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1150, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilhelmova-Ilieva N., Jacquet R., Quideau S., Galabov A. S. (2014). Ellagitannins as synergists of ACV on the replication of ACV-resistant strains of HSV 1 and 2. Antivir. Res. 110, 104–114. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.07.017, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Q., Zhu Q., Zhou R., Liu J., Peng T. (2011). Identification and characterization of acyclovir-resistant clinical HSV-1 isolates from children. J. Clin. Virol. 52, 107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.06.009, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Jia J., Wang L., Li F., Wang Y., Jiang Y., et al. (2020). Anti-HSV-1 activity of Aspergillipeptide D, a cyclic pentapepetide isolated from fungus aspergillus sp. SCSIO 41501. Virol. J. 17:41. doi: 10.1186/s12985-020-01315-z, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley R. J., Roizman B. (2001). Herpes simplex virus infections. Lancet 357, 1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong S., Fan J., Kitazato K. (2010). The antiviral protein cyanovirin-N: the current state of its production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86, 805–812. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2470-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H. X., Lee S. H., Lee S. F., White R. L., Blay J. (1999). Isolation and characterization of an anti-HSV polysaccharide from Prunella vulgaris. Antivir. Res. 44, 43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(99)00053-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y., Yamamura J., Sato H., Koyasu M., Obara Y., Sekiguchi H., et al. (1996). Efficacy of Cafon gel on cutaneous infection with herpes simplex virus (HSV)-2 and acyclovir-resistant HSV in mice. J. Dermatol. Sci. 13, 237–241. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(97)89474-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Wang H., Xu Y., Luan M., Zhao F., Meng Q. (2021). Advances on the anti-inflammatory activity of Oleanolic acid and derivatives. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 21, 2020–2038. doi: 10.2174/1389557521666210126142051, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]