Abstract

The iron chelator desferrioxamine (DFO) B is widely used in the therapy of patients with iron overload. As a side effect, DFO may favor the occurrence of fulminant Yersinia infections. Previous work from our laboratory showed that this might be due to a dual role of DFO: growth promotion of the pathogen and immunosuppression of the host. In this study, we sought to determine whether conjugation of DFO to hydroxyethyl starch (HES-DFO) may prevent exacerbation of Yersinia infection in mice. We found HES-DFO to promote neither growth of Yersinia enterocolitica nor mitogen-induced T-cell proliferation and gamma interferon production by T cells in vitro. Nevertheless, in vivo HES-DFO promoted growth of Y. enterocolitica possibly due to cleavage of HES and release of DFO. The pretreatment of mice with DFO resulted in death of all mice 2 to 5 days after application of a normally sublethal inoculum of Y. enterocolitica, while none of the mice pretreated with HES-DFO died within the first 7 days postinfection. However, some of the HES-DFO-treated mice died 8 to 14 days postinfection. Thus, due to the delayed in vivo effect HES-DFO failed to trigger Yersinia-induced septic shock, which accounts for early mortality in DFO-associated septicemia. Moreover, our data suggest that DFO needs to be taken up by host cells in order to exert its immunosuppressive action. These results strongly suggest that HES-DFO might be a favorable drug with fewer side effects than DFO in terms of DFO-promoted fulminant infections.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a gram-negative bacterium which is pathogenic for humans and rodents (23, 25). Infection with this pathogen causes a wide range of clinical manifestations including enterocolitis and mesenteric lymphadenitis (28). In immunocompromised patients or patients with iron overload, Yersinia causes systemic infections with abscesses in spleen and liver (27, 33, 37).

Previous work from this laboratory showed that desferrioxamine (DFO) may play a dual role in pathogenesis of Yersinia infection: growth and virulence promotion of Y. enterocolitica by iron provision to the pathogen and immunosuppression of the host. In fact, iron-loaded DFO (ferrioxamine [FO]) can be taken up and used as an iron source by Yersinia (16, 36). The genes encoding FO uptake have been characterized and are considered part of the virulence factors required for high-level pathogenicity of Yersinia (10, 11).

On the other hand, DFO exerts effects on various components of the immune system of the host. DFO inhibits proliferation of T and B lymphocytes and cytokine production of macrophages and modulates interaction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with yersiniae (3, 21). In keeping with these observations, we and others have demonstrated that DFO increases pathogenicity of Y. enterocolitica in mice, resulting in fatal septicemia and shock (5, 39, 40). Moreover, fatal septicemia with Yersinia and other microorganisms including the fungus Rhizopus sp. has been reported for patients undergoing DFO therapy (13, 15, 40).

In an attempt to find drugs with comparable iron binding capacity but reduced Yersinia virulence-enhancing properties, DFO B has been compared with DFO G in terms of its biological properties for bacteria and host cells (3, 5). DFO G was found to have fewer immunosuppressive properties and to exert less enhancement of virulence of Yersinia in vivo (5). Thus, DFO G might be a favorable alternative to DFO B in clinical DFO therapy.

Moreover, studies have been conducted with DFO bound to hydroxyethyl starch (HES) and have indicated that HES-DFO improves safety without interference with the iron binding efficacy of DFO (22, 29, 32). In accordance with these results, HES-DFO was found to significantly attenuate systemic oxidant injury, resulting in less toxicity to the lung and kidney in early sepsis (30, 34). Therefore, this study is focused on the immunological effects of HES-DFO on T cells and the virulence-modulating effect of HES-DFO on Y. enterocolitica in vitro and in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice aged 6 to 8 weeks (Charles River Wiga, Sulzfeld, Germany) were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions (positive-pressure cabinet) and provided food and water ad libitum.

Bacteria.

Y. enterocolitica serotype O3 strain Y-108 (yersiniabactin-negative wild-type strain) (23) and Y. enterocolitica serotype O8 strain WA-314 (yersiniabactin-positive wild-type strain), both harboring the virulence plasmid pYV, were passaged in mice and cultured as described previously (6). The WA-foxA mutant strain, which lacks the foxA gene encoding the FO receptor FoxA, was derived from the WA-314 strain (11). The Escherichia coli strain HK97 (aroB fhuA fhuE::λplacMu; enterobactin-negative mutant with an insertionally inactivated gene of the FO E receptor) (20, 43, 44) and plasmid pFU2 encoding the DFO receptor FoxA of WA-314 (11) were kindly provided by K. Hantke (Tübingen, Germany).

Siderophores.

DFO (DFO mesylate; Desferal) was donated by Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), and HES-DFO was provided by Biomedical Frontiers, Inc. (Minneapolis, Minn.). HES-DFO consists of DFO that has been covalently attached to HES (22). The resulting polymeric iron chelator is polydisperse with an average molecular mass of 70,000 Da. The aqueous solution of HES-DFO was at a total chelator concentration of 40 mM (pH 6.0 to 6.6). This is equivalent to 26 mg of DFO/ml in chelating capacity. Both DFO and HES-DFO were dissolved in distilled water and sterile filtered prior to use. Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 ml of 8 mM DFO or HES-DFO 1 h prior to challenge with Y. enterocolitica as described previously (6, 40). Control mice were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4.

Bioassay for utilization of DFO B (DFO) and HES-DFO.

To determine the ability of the bacteria [Y. enterocolitica O8 strains WA-314 and WA-foxA; Y. enterocolitica O3 strain Y-108; E. coli HK97(pFU2)] to utilize DFO and HES-DFO as an iron carrier in vitro, the strains were grown in NB medium (8 g of nutrient broth and 5 g of NaCl per 1 liter of distilled water) to an optical density of 0.5 at a wavelength of 600 nm. Thirty microliters of the bacteria was seeded in 10 ml of 0.6% H2O top agar on 1% NB agar, both containing the iron chelator α-α′-dipyridyl at a concentration of 200 μM (24). The iron-chelating compounds were provided by filter papers soaked with 12 μl of a solution containing 4 mM DFO or HES-DFO. The filter papers were placed on the agar surface, and the diameters (mean values of five separate determinations) of the zone of enhanced bacterial growth around the filter paper were determined after 24 h of culture at 26°C (Yersinia) and 37°C (E. coli), respectively. Additionally, iron-loaded chelators FO B (FO) and FO B-HES (HES-FO) were used under the same conditions.

The presence of iron-loaded chelators in sera of DFO- and HES-DFO-treated mice was monitored. For this purpose, mice were killed 1, 4, and 12 h after injection with DFO and HES-DFO, respectively. Sera were prepared and used in the bioassay described above to determine the in vitro feeding properties of the serum after injection of DFO and HES-DFO in order to reveals the presence of DFO in the serum.

Animal infection.

For infection of mice, frozen stocks of Y. enterocolitica O3 strain Y-108 were thawed and diluted in PBS to the appropriate concentration as stated below. Suspensions containing various numbers of bacteria were administered intravenously to mice 1 h after pretreatment with 1 ml of 8 mM DFO, HES-DFO, or PBS. Briefly, three groups of mice (eight per group) were challenged with a normally sublethal inoculum of Y. enterocolitica O3 strain Y-108 (0.2 50% lethal dose = 1.2 × 105 CFU). The optimization of the various compounds used in these experimental settings has been described previously (5). The actual number of bacteria administered was determined by plating 0.1 ml of serial dilutions of the inoculum on Mueller-Hinton agar and counting CFU after a 36-h incubation at 26°C. The survival of mice was observed for 12 days. In parallel experiments, mice were killed at days 2, 4, and 12 postinfection and the numbers of bacteria reisolated from spleen were determined. For this purpose, the spleen was aseptically removed and homogenized in sterile PBS-bovine serum albumin-Tergitol. Serial 1:10 dilutions of the homogenate were plated on Mueller-Hinton agar, and after a 36-h incubation at 26°C, CFU were counted.

Cell culture medium.

Cells were cultured in Click/RPMI 1640 medium (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine (Life Technologies GIBCO BRL, Berlin, Germany), 10 mM HEPES (Biochrom), 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 100 U of penicillin (Biochrom) per ml, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (Biochrom).

Cell suspensions and culture conditions.

Spleens from mice were removed aseptically, and single-cell suspensions were prepared; 2 × 105 splenic mononuclear cells (SMNC) were cultivated in round-bottom microtiter plates (Nunc, Wiesbaden, Germany) and incubated with serial dilutions of either DFO, HES-DFO, FO, or HES-FO. Simultaneously, 3 μg of concanavalin A (ConA; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) per ml of medium was added to the wells for mitogenic induction of T-cell activation and proliferation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Proliferation assay.

Triplicate cultures of SMNC were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (ICN Biochemicals, Eschwege, Germany) per well for 6 h after 2 days of incubation. The samples were collected using a cell harvester (Harvester 96; EG & G Wallac, Turku, Finland) and counted in a microplate liquid scintillation and luminescence counter (1450 MicroBeta TriLux; EG & G Wallac). To determine the relative inhibition of proliferation by the siderophores, cultures containing only ConA were taken as the 100% proliferation value. All experiments were repeated and revealed comparable results.

Cytokine assays.

For determination of cytokine production, 2 × 106 spleen cells were cultured in the presence of 3 μg of ConA per ml in 2 ml of cell culture medium in 12-well macroculture plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). DFO, HES-DFO, FO, or HES-FO was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. After 48 h, supernatants were collected and used in the cytokine assays. Gamma interferon (IFN-γ) levels were determined by capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described recently (6, 7, 46). Briefly, ELISA microtiter plates (Greiner, Solingen, Germany) were coated with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (AN-18.17.24). After blocking of nonspecific binding sites, supernatants were added to wells and incubated overnight. After several wash steps, biotin-labeled anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (R4-6A2) was added. Finally, an avidin-biotin-alkaline phosphatase complex (Strept ABComplex/AP; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was added. For signal development, p-nitrophenyl phosphate disodium (Sigma) was added, and the optical density was determined at wavelengths of 405 and 490 nm with an ELISA reader. The levels of IFN-γ from T-cell culture supernatants were finally determined from the straight-line portion of the standard curve by using recombinant murine IFN-γ (kindly provided by G. Adolf).

Statistics.

Data were analyzed for statistical significance by unpaired Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Promotion of Y. enterocolitica growth by DFO (FO) and HES-DFO (HES-FO).

HES-DFO represents a high-molecular-weight form of the siderophore DFO B (DFO), generated by covalent binding of DFO to HES (22). The different molecular mass, which may be relevant for an effective uptake of the siderophore by Yersinia, prompted us to compare promotion of growth of different Yersinia strains by these siderophores using a modified filter disk feeding bioassay (5). This modified assay reveals growth enhancement or growth suppression of Yersinia depending on the ability or inability, respectively, to utilize iron from the siderophore.

The results of the feeding experiments are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Y. enterocolitica O8 strain WA-314 produces an endogenous, Yersinia-specific siderophore (yersiniabactin) and additionally expresses a functional DFO B receptor (FoxA). Growth of the WA-314 strain was promoted by iron-loaded FO (halo diameter of enhanced bacterial growth; 44.8 ± 3.0 mm) as well as by iron-free DFO (39.8 ± 2.6 mm). In contrast, HES-FO and HES-DFO suppressed growth of the WA-314 strain under test conditions (halo diameter of growth inhibition, 9.8 ± 1.3 and 11.6 ± 2.3 mm, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Utilization of FO and high-molecular-weight HES-FO by Y. enterocolitica O3/Y-108, O8/WA-314, and FO receptor mutant (WA-foxA) and E. coli HK97(pFU2) as determined by the feeding bioassaya

| Bacterial strain | Diam (mm) of growth enhancement zone (+) or growth inhibition zone (−)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFO | HES-DFO | FO | HES-FO | |

| Y. enterocolitica | ||||

| WA-314 | +39.8 ± 2.6* | −11.6 ± 2.3* | +44.8 ± 3.0 | −9.8 ± 1.3 |

| WA-foxA | −21.0 ± 2.5* | −14.0 ± 3.5* | +26.4 ± 4.2 | −10.4 ± 1.7 |

| Y-108 | +26.2 ± 3.3* | −9.8 ± 1.8* | +30.2 ± 3.3 | −8.2 ± 1.5 |

| E. coli HK97 (pFU2) | +32.4 ± 3.0* | 0 | +31.4 ± 3.7 | 0 |

Results are means ± standard deviations of five independent investigations. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between DFO and HES-DFO for each strain. Strains were grown on α-α′-dipyridyl-containing NB agar to restrict iron supply. Diameters of zones of enhanced or decreased growth around siderophore-containing filter papers were determined after 24 h of culture. Supplemental iron was provided by filter papers soaked with 12 μl of 4 mM solutions of siderophores FO and HES-FO, respectively. DFO and HES-DFO are the corresponding iron-free derivatives of these siderophores.

TABLE 2.

Utilization of FO and high-molecular-weight HES-FO by E. coli HK97(pFU2) as determined by the feeding bioassaya

| Pretreatment of mice | Diam (mm) of growth enhancement zone

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 4 h | 24 h | |

| PBS | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| DFO | +42.4 ± 2.6* | 0 | 0 |

| HES-DFO | +23.8 ± 2.3* | 26.2 ± 3.3* | 11.6 ± 1.1* |

Results are means ± standard deviations of five independent investigations. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between DFO and HES-DFO for each time point. Strains were grown on α-α′-dipyridyl-containing NB agar to restrict iron supply. Diameters of zones of enhanced growth around siderophore-containing filter papers were determined after 24 h of culture. Filter papers soaked with 12 μl of serum from mice 1, 4, and 24 h after administration of PBS, DFO, and HES-DFO, respectively, were added.

Y. enterocolitica strain WA-foxA is a mutant derived from WA-314 defective in the FO B receptor FoxA but still able to take up iron by the yersiniabactin siderophore system. Growth of the Y. enterocolitica WA-foxA strain was promoted by FO (26.4 ± 4.2 mm) but not by HES-FO. DFO (halo diameter of growth inhibition; 21.0 ± 2.5 mm) as well as HES-DFO (14.0 ± 3.5 mm) suppressed growth of the WA-foxA strain (Table 1).

Y. enterocolitica O3 strain Y-108 was used as a Yersinia strain that lacks the yersiniabactin siderophore system while still being able to take up FO by the FO receptor FoxA. Growth of the Y-108 strain was promoted by FO (30.2 ± 3.3 mm) and DFO (26.2 ± 3.3 mm), whereas both HES-FO and HES-DFO exhibited a slight inhibition of growth of the Y-108 strain (9.8 ± 1.8 and 8.2 ± 1.5 mm, respectively).

E. coli strain HK97(pFU2) has been used as an additional indicator strain for a selective FO uptake, as reported previously (5, 20). Under the test conditions, both FO and DFO showed growth enhancement (halo diameter of enhanced bacterial growth, 31.4 ± 3.7 and 32.4 ± 3.0 mm, respectively) on E. coli strain HK97(pFU2), whereas HES-FO and HES-DFO exhibited no effect on growth enhancement.

The DFO-FO bioassay using E. coli strain HK97(pFU2) as indicator strain was used to detect DFO-FO in sera of mice after DFO treatment. To investigate the effect of parenterally applied DFO in comparison to HES-DFO on bacterial growth, we determined whether sera taken from mice injected with DFO or HES-DFO could provide iron to bacteria by using the bioassay described above (Table 2). The bioassay was done with E. coli strain HK97(pFU2), because both Yersinia strains (WA-314 and Y-108) showed some background growth when incubated with sera from mice, as reported previously (5). As shown in Table 2, serum obtained from mice 1 h after treatment with HES-DFO showed a significantly smaller growth-promoting effect on bacteria (23.8 ± 2.3 mm) than did serum from mice injected with DFO (42.4 ± 2.6 mm). As in vitro DFO-FO, but not HES-DFO–HES-FO, promotes growth of E. coli HK97(pFU2), the results suggest the presence of free DFO-FO in serum from mice injected with HES-DFO. Moreover, while DFO-FO was no longer detectable after 2 to 4 h, it was still present in sera of mice 24 h after injection with HES-DFO (Table 2).

DFO-modulated proliferation and cytokine production of T cells.

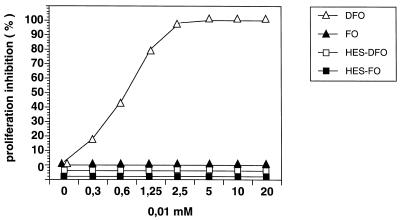

In accordance with previous results (5), ConA-induced proliferation of T cells could be entirely inhibited in a dose-dependent manner by DFO as determined by [3H]thymidine uptake (Fig. 1). Blocking of ConA-stimulated proliferation by DFO could be reversed by the addition of equimolar concentrations of ferric iron (data not shown). In contrast, inhibition of T-cell proliferation was not observed with HES-DFO or HES-FO (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of ConA-induced proliferation of SMNC by serial dilutions of DFO B (DFO), FO B (FO), HES-DFO, and HES-FO, respectively. Values from cultures containing SMNC and ConA only were taken as 100%.

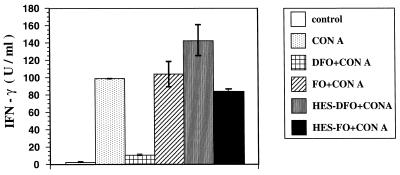

The effect of DFO, FO, HES-DFO, and HES-FO on IFN-γ production by T cells was investigated by ELISA-based determination of IFN-γ concentrations in supernatants of ConA-stimulated T cells. The data depicted in Fig. 2 show that DFO at a 100 μM concentration inhibited the ConA-induced IFN-γ production of T cells by 90% (P < 0.001). As observed for T-cell proliferation, the addition of an equimolar concentration of ferric ions abolished this effect (data not shown). In contrast, HES-DFO showed only an insignificant effect on ConA-induced IFN-γ production by T cells (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

IFN-γ production by splenic T cells of BALB/c mice after coincubation with 100 μM DFO, FO, HES-DFO, and HES-FO. T cells were stimulated with 3 μg of ConA per ml in the presence of irradiated feeder cells in macroculture wells. Supernatants were harvested 24 h later and used in an IFN-γ-specific ELISA (see Materials and Methods). The values shown are the means ± standard deviations from triplicates.

Influence of DFO and HES-DFO on virulence of Y. enterocolitica.

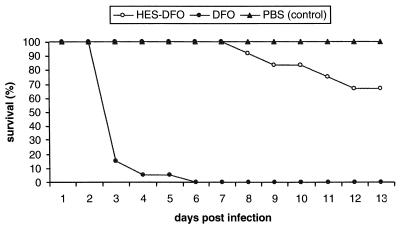

In order to analyze the effects of DFO and HES-DFO on virulence of Y. enterocolitica for mice, BALB/c mice were sublethally infected with Y. enterocolitica strain 108-P 1 h after administration of DFO, HES-DFO, or PBS. As shown in Fig. 3, all mice injected with DFO before Y. enterocolitica infection died by days 2 to 5 from fulminant Y. enterocolitica infection leading to septic shock with necrosis of liver tissue (data not shown). In contrast, none of the controls (PBS) or HES-DFO-treated mice died during the early phase of the infection. However, at days 7 to 12 postinfection some mice injected with HES-DFO died from severe Yersinia infection leading to formation of macroabscesses in liver, lung, and spleen, while all of the control mice survived (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Survival of mice after Y. enterocolitica infection modulated by 1 ml of 8 mM DFO (n = 20; black dots) or HES-DFO (n = 12; open circles). All control mice pretreated with PBS did survive the Y. enterocolitica infection (n = 15; black triangles).

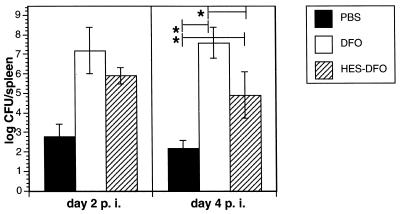

In an attempt to explain this different kinetics of survival after Yersinia infection in DFO- or HES-DFO-treated mice, additional experiments were conducted in which mice were killed at various intervals after the infection and the numbers of yersiniae in spleens were determined. As shown in Fig. 4, mice treated with DFO had significantly higher bacterial counts in the spleen compared to controls (P < 0.001) or HES-DFO-treated mice (P < 0.05) on day 4 postinfection. However, HES-DFO-treated mice also had significantly higher bacterial counts in the spleen than controls (P < 0.001). On day 12 postinfection, no bacteria were detectable in spleen or liver of control mice (PBS pretreatment).

FIG. 4.

Effects of in vivo administration of PBS, DFO, and HES-DFO on clearance of Y. enterocolitica from the spleen of sublethally (0.7 × 105 CFU) infected BALB/c mice determined on days 2 and 4 postinfection (p.i.). Results are means ± standard deviations of eight animals. The asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

These data suggest that DFO and, to a lesser degree, HES-DFO promote virulence of Y. enterocolitica in mice. The profound effect of DFO seems to lead to Yersinia-induced septic shock causing death in mice during the first few days after infection, whereas HES-DFO appears not to favor the development of septic shock. However, HES-DFO causes exacerbation of Yersinia infection leading to a severe course of infection and death at a later phase of the infection (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Iron restriction encountered in the body fluids of mammals by invading microorganisms is part of the nonspecific host defense against bacterial pathogens. A highly efficient iron acquisition system is therefore an essential feature for successful multiplication of pathogenic bacteria in the host. Several species of pathogens use low-molecular-weight iron-chelating compounds (siderophores) such as DFO for iron uptake (8, 17, 19). As DFO is widely used in deferration therapy in humans with iron overload (31), a severe side effect of DFO treatment is an increased susceptibility of the patients to microbial infections (13, 15, 18, 39, 40, 47). In this study, we compared the effects of the high-molecular-weight form of DFO (HES-DFO) and DFO on bacterial growth, cellular immune response in terms of T-cell proliferation, and cytokine production in vitro. Moreover, we determined the effects of both siderophores on Yersinia infection in vivo.

For DFO and HES-DFO, the results of the in vitro siderophore feeding experiments demonstrate a different impact on growth of the Yersinia strains. Y. enterocolitica O8 strain WA-314 is able to utilize iron-loaded DFO (FO) as an iron source via the FO receptor FoxA (11, 42). Moreover, the WA-314 strain expresses an endogenous siderophore-mediated iron uptake system, the yersiniabactin system (12, 35, 38). WA-foxA lacks the FO receptor but is still able to take up iron via the yersiniabactin system. In contrast, Y. enterocolitica O3 strain Y-108-P is able to utilize FO but is devoid of the yersiniabactin system. Consistently, the results of the in vitro feeding experiments indicate that HES-FO cannot be used as an iron source via FoxA by yersiniae, whereas unmodified FO is able to provide iron to those strains expressing the FO receptor FoxA. This is most probably due to blocking of transmembranous DFO-FO uptake by conjugation to HES. Moreover, the results obtained with the mutant strain WA-foxA incubated either with FO or with HES-FO showed impaired bacterial growth when HES-FO was applied. As WA-foxA is not able to take up FO but still can utilize the endogenous siderophore yersiniabactin, the results may suggest that WA-foxA is provided with iron by yersiniabactin competing with iron-loaded FO. Moreover, it is tempting to speculate that yersiniabactin is hindered in chelating iron from FO if the HES moiety is linked to the FO molecule.

Further feeding experiments were performed using serum of mice previously treated with either HES-DFO or DFO. In DFO-injected mice, serum exhibited strong growth promotion (42.4- ± 2.6-mm feeding halo) as revealed by the in vitro feeding assay. However, this effect could be observed only transiently at 1 h after DFO injection, suggesting that free DFO-FO is available only during a short time. In contrast, serum of HES-DFO-treated mice initially exhibited a significantly lower promotion of growth of yersiniae (23.8- ± 2.3-mm feeding halo) 1 h after injection compared to serum of DFO-injected mice. Moreover, this growth-promoting effect was observed for more than 24 h, suggesting that in HES-DFO-treated mice DFO is released from HES-DFO during a period of at least 24 h, probably due to cleavage of HES, e.g., by amylase present in normal serum (45).

Besides growth-promoting effects on yersiniae, we investigated the suppression of T-cell activation by HES-DFO. Inhibition of ConA-stimulated T-cell proliferation and IFN-γ production in vitro was exclusively caused by DFO, not by HES-DFO. IFN-γ is the most crucial and dominant cytokine required for control of Yersinia infection (2). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that production of other cytokines might also be affected by DFO.

Using primary cultures of rat proximal tubular cells, Paller and Hedlund (34) have shown HES-DFO in contrast with DFO to be exclusively confined to the extracellular compartment. In line with this observation and our previous results (3–5), the bioassays argue for an intracellular target of DFO for the impairment of T-cell function. The short half-life of DFO in serum is due to the rapid renal clearance of this compound (1) and possibly due to the intracellular accumulation (14). Both mechanisms may not be true for DFO bound to HES. Thus, conjugation of DFO to HES affects both parts of the dual role of DFO in Yersinia infection, bacterial growth, and immunosuppression.

In vivo DFO induced a septic shock in Yersinia-infected mice leading to death after 2 to 5 days, as suggested by the marked hepatocellular necrosis observed in these mice. Moreover, bacterial counts were dramatically increased in infected organs (e.g., spleen) of DFO-treated mice compared to controls. More strikingly, HES-DFO-treated mice did not develop septic shock after Yersinia infection, as indicated by the survival for more than a week after the infection. Nevertheless, probably due to the release of DFO from HES-DFO and deposition of HES-DFO in certain organs such as the liver, Yersinia infection was finally exacerbated in some HES-DFO-treated mice, in which bacterial counts significantly increased compared to those in control mice. The majority of the HES-DFO-treated mice survived at least 14 days postinfection, and no bacteria could be detected in spleens of those mice.

From these results, we conclude that DFO released from HES-DFO is taken up by host cells and bacteria after injection (26) and thus promotes growth of yersiniae and immunosuppression of the host. Consequentially, these events lead to an acute exacerbation of the Yersinia infection, resulting in early mortality. In fact, DFO-treated mice injected with 0.2 50% lethal dose died after 2 to 3 days. In contrast, the early fulminant course of infection is prevented by HES-DFO, possibly due to the lack of high concentrations of free DFO in serum. Nevertheless, due to cleavage of HES-DFO, and thus slow release of free DFO in HES-DFO-treated mice, a minor but, in the long run, detrimental virulence-enhancing effect on yersiniae also occurs in HES-DFO-treated mice.

On the other hand, additional mechanisms might account for the failure of HES-DFO to promote Yersinia-induced lethal shock. Thus, in other models of septic shock HES-DFO, but not HES alone, prevents early septic shock (30). In fact, HES-DFO significantly attenuates systemic oxidant injury (the degree of protection being most impressive in the lungs and kidneys) by diminishing iron as a catalytic mediator in the production of hydroxyl radicals ( · OH) (34, 41). Activity of the serum amylase on HES-conjugated molecules depends on the molar substitution ratio between the proportions of hydroxyethyl-ether and glucose within the HES macromolecule (9). Therefore, in future studies we intend to investigate HES-DFO molecules with other molar substitutions of the HES moiety to analyze their possible effect on Yersinia infection. Moreover, a more rapid deposition of HES-DFO in liver tissue may influence its bioactivity and possibly the effect on yersinia virulence (42).

Taken together, these results argue for the possibility of modifying DFO in order to generate a drug with comparable iron-binding capacity but fewer side effects on the host and infectious pathogens such as Yersinia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniela Fischer and Sonja Preger for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allain P, Mauras Y, Chaleil D, Simon P, Ang K S, Cam G, Le Mignon L, Simon M. Pharmakokinetics and renal elimination of desferrioxamine and ferrioxamine in healthy subjects and patients with haemochromatosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;24:207–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1987.tb03163.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Autenrieth I B, Beer M, Bohn E, Kaufmann S H, Heesemann J. Immune responses to Yersinia enterocolitica in susceptible BALB/c and resistant C57BL/6 mice: an essential role for gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2590–2599. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2590-2599.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Autenrieth I B, Bohn E, Ewald J H, Heesemann J. Deferoxamine B but not deferoxamine G1 inhibits cytokine production in murine bone marrow macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:490–496. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.2.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Autenrieth I B, Hantke K, Heesemann J. Immunosuppression of the host and delivery of iron to the pathogen: a possible dual role of siderophores in the pathogenesis of microbial infections? Med Microbiol Immunol. 1991;180:135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00206117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Autenrieth I B, Reisbrodt R, Saken E, Berner R, Vogel U, Rabsch W, Heesemann J. Desferrioxamine-promoted virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica for mice depends on both desferrioxamine species and mouse strains. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:562–567. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Autenrieth I B, Tingle A, Reske Kunz A, Heesemann J. T lymphocytes mediate protection against Yersinia enterocolitica in mice: characterization of murine T-cell clones specific for Y. enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1140–1149. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1140-1149.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Autenrieth I B, Vogel U, Preger S, Heymer B, Heesemann J. Experimental Yersinia enterocolitica infection in euthymic and T-cell-deficient athymic nude C57BL/6 mice: comparison of time course, histomorphology, and immune response. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2585–2595. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2585-2595.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bagg A, Neilands J B. Molecular mechanism of regulation of siderophore-mediated iron assimilation. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:509–518. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.4.509-518.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron J F. Pharmacology of low molecular weight hydroxyethyl starch. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1992;11:509–515. doi: 10.1016/s0750-7658(05)80756-7. . (In French.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumler A, Koebnik R, Stojiljkovic I, Heesemann J, Braun V, Hantke K. Survey on newly characterized iron uptake systems of Yersinia enterocolitica. Int J Med Microbiol Virol Parasitol Infect Dis. 1993;278:416–424. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80858-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bäumler A J, Hantke K. Ferrioxamine uptake in Yersinia enterocolitica: characterization of the receptor protein FoxA. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1309–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bearden S W, Fetherston J D, Perry R D. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1659–1668. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1659-1668.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boelaert J R, de Locht M, Van Cutsem J, Kerrels V, Cantinieaux B, Verdonck A, van Landuyt H W, Schneider Y J. Mucormycosis during deferoxamine therapy is a siderophore-mediated infection. In vitro and in vivo animal studies. J Clin Investig. 1993;91:1979–1986. doi: 10.1172/JCI116419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottomley S S, Wolfe L C, Bridges K R. Iron metabolism in K562 erythroleukemic cells. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6811–6815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyce N, Wood C, Holdsworth S, Thomson N M, Atkins R C. Life-threatening sepsis complicating heavy metal chelation therapy with desferrioxamine. Aust N Z J Med. 1985;15:654–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun V, Hantke K. Genetics of bacterial iron transport. In: Winkelmann G, editor. Handbook of microbial iron chelates. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1991. pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V, Winkelmann G. Microbial iron transport: structure and function of siderophores. Prog Clin Biochem Med. 1987;5:67–99. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullen J J, Griffiths E. Iron and infection. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. pp. 69–137. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crosa J H. Genetics and molecular biology of siderophore-mediated iron transport in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:517–530. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.4.517-530.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Deiss K, Hantke K, Winkelmann G. Molecular recognition of siderophores: a study with cloned ferrioxamine receptors (FoxA) from Erwinia herbicola and Yersinia enterocolitica. Biometals. 1998;11:131–137. doi: 10.1023/a:1009230012577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewald J H, Heesemann J, Rüdiger H, Autenrieth I B. Interaction of polymorphonuclear leukocytes with Yersinia enterocolitica: role of the Yersinia virulence plasmid and modulation by the iron-chelator desferrioxamine B. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:140–150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallaway P E, Eaton J W, Panter S S, Hedlund B E. Modulation of deferoxamine toxicity and clearance by covalent attachment to biocompatible polymers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:10108–10112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heesemann J. Chromosomal-encoded siderophores are required for mouse virulence of enteropathogenic Yersinia species. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;48:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heesemann J, Hantke K, Vocke T, Saken E, Rakin A, Stojiljkovic I, Berner R. Virulence of Yersinia enterocolitica is closely associated with siderophore production, expression of an iron-repressible outer membrane protein of 65000 Da and pesticin sensitivity. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:397–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoogkamp Korstanje J A, de Koning J, Heesemann J. Persistence of Yersinia enterocolitica in man. Infection. 1988;16:81–85. doi: 10.1007/BF01644307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyes K P, Porter J B. Subcellular distribution of desferrioxamine and hydroxypyridin-4-one chelators in K562 cells affects chelation of intracellular iron pools. Br J Haematol. 1993;85:393–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelly D A, Price E, Jani B, Wright V, Rossiter M, Walker Smith J A. Yersinia enterocolitis in iron overload. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1987;6:643–645. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198707000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larsen J H. The spectrum of clinical manifestations of infections with Yersinia enterocolitica and their pathogenesis. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1979;5:257–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahoney J R, Jr, Hallaway P E, Hedlund B E, Eaton J W. Acute iron poisoning. Rescue with macromolecular chelators. J Clin Investig. 1989;84:1362–1366. doi: 10.1172/JCI114307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moch D, Schroppel B, Schoenberg M H, Schulz H J, Thorab F C, Marzinzag M, Hedlund B E, Bruckner U B. Protective effects of hydroxyethyl starch-deferoxamine in early sepsis. Shock. 1995;4:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Modell B. Advances in the use of iron-chelating agents for the treatment of iron overload. Prog Hematol. 1979;11:267–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mousa S A, Ritger R C, Smith R D. Efficacy and safety of deferoxamine conjugated to hydroxyethyl starch. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1992;19:425–429. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paitel J F, Guerci A P, Dorvaux V, Lederlin P. Yersinia enterocolitica septicemia, iron overload and deferoxamine. Rev Med Interne. 1995;16:705–707. doi: 10.1016/0248-8663(96)80775-2. . (In French.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paller M S, Hedlund B E. Extracellular iron chelators protect kidney cells from hypoxia/reoxygenation. Free Radic Biol Med. 1994;17:597–603. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelludat C, Rakin A, Jacobi C A, Schubert S, Heesemann J. The yersiniabactin biosynthetic gene cluster of Yersinia enterocolitica: organization and siderophore-dependent regulation. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:538–546. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.538-546.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perry R D, Brubaker R R. Accumulation of iron by yersiniae. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:1290–1298. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.3.1290-1298.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabson A R, Hallett A F, Koornhof H J. Generalized Yersinia enterocolitica infection. J Infect Dis. 1975;131:447–451. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rakin A, Urbitsch P, Heesemann J. Evidence for two evolutionary lineages of highly pathogenic Yersinia species. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2292–2298. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2292-2298.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robins-Browne R M, Prpic J K. Desferrioxamine and systemic yersiniosis. Lancet. 1983;ii:1372. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91136-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robins-Browne R M, Prpic J K. Effects of iron and desferrioxamine on infections with Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1985;47:774–779. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.3.774-779.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roza A M, Slakey D P, Pieper G M, Van Ye T M, Moore Hilton G, Komorowski R A, Johnson C P, Hedlund B E, Adams M B. Hydroxyethyl starch deferoxamine, a novel iron chelator, delays diabetes in BB rats. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;123:556–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Saito K, Yoshioka H, Ito N, Kazama S, Tanizawa H, Lin Y, Watanabe H, Ogata T, Kamada H. Spatiotemporal ESR-CT study on the metabolism of spin-labeled polysaccharide in a mouse. Biol Pharm Bull. 1997;20:904–909. doi: 10.1248/bpb.20.904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauer M, Hantke K, Braun V. Ferric-coprogen receptor FhuE of Escherichia coli: processing and sequence common to all TonB-dependent outer membrane receptor proteins. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2044–2049. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.5.2044-2049.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sauer M, Hantke K, Braun V. Sequence of the fhuE outer-membrane receptor gene of Escherichia coli K12 and properties of mutants. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:427–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schaeffer R C, Jr, Renkiewicz R R, Chilton S M, Marsh D, Carlson R W. Preparation and high-performance size-exclusion chromatographic (HPSEC) analysis of fluorescein isothiocyanate-hydroxyethyl starch: macromolecular probes of the blood-lymph barrier. Microvasc Res. 1986;32:230–243. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(86)90057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slade S J, Langhorne J. Production of interferon-gamma during infection of mice with Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Immunobiology. 1989;179:353–365. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(89)80041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberg E D. Iron withholding: a defense against infection and neoplasia. Physiol Rev. 1984;64:65–102. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1984.64.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]