Abstract

Purpose:

How care delivery influences urban-rural disparities in cancer outcomes is unclear. We sought to understand community oncologists’ practice settings to inform cancer care delivery interventions.

Methods:

We conducted secondary analysis of a national dataset of providers billing Medicare from June 1, 2019 to May 31, 2020 in 13 states in the central U.S. We used Kruskal-Wallis Rank and Fisher’s Exact tests to compare physician characteristics and practice settings among rural and urban community oncologists.

Findings:

We identified 1963 oncologists practicing in 1492 community locations; 67.5% practiced in exclusively urban locations, 11.3% in exclusively rural locations, and 21.1% in both rural and urban locations. Rural-only, urban-only, and urban-rural spanning oncologists practice in an average of 1.6, 2.4, and 5.1 different locations, respectively. A higher proportion of rural community sites were solo practices (11.7% vs 4.0% (p<0.001) or single specialty practices (16.4% vs 9.4%, p<0.001); and had less diversity in training environments (86.5% vs 67.8% with <2 medical schools represented, p<0.001) than urban community sites. Rural multi-specialty group sites were less likely to include other cancer specialists.

Conclusions:

We identified two potentially distinct styles of care delivery in rural communities, which may require distinct interventions: 1) innovation-isolated rural oncologists, who are more likely to be solo providers, provide care at few locations, and practice with doctors with similar training experiences; and 2) urban-rural spanning oncologists who provide care at a high number of locations and have potential to spread innovation, but may face high complexity and limited opportunity for care standardization.

Keywords: Community oncology, cancer care, rural disparities, healthcare access

INTRODUCTION

Rural cancer patients often experience poorer outcomes compared to urban patients.1–3 These geographic disparities in cancer outcomes may be driven by differences in the quality of care they receive. A recent comparison of rural and urban patients’ cancer outcomes demonstrated that when rural cancer patients are provided the same care protocols as urban patients, rural cancer patients experience similar survival rates.4

Numerous evidence-based practices are demonstrated to improve cancer outcomes, but many are under-utilized among rural cancer providers.1–3, 5, 6 Although geographic disparities in use of evidence-based practice are widely documented, less is known about why evidence-based cancer care practices are less likely to be adopted in rural care settings or how best to increase their uptake. Some individual physician characteristics known to differ between urban and rural physicians, such as years in practice, gender, and specialty, are associated with adoption of evidence-based practice.7–11 However, these associations are variable, suggesting contextual factors may play a role. A key principle of implementation science, the scientific study of systematic approaches to accelerate successful uptake of evidence-based care, is understanding the context in which care is delivered.12, 13 Implementation science frameworks identify context as the necessary conditions for adoption of evidence-based practice, including both the physical and social environments in which care is delivered.13, 14 These can include: structural characteristics of the “firm” or organization in which care is delivered, such as its size and subsequent specialization as size and competition increase; relational characteristics of the individuals within the organization—shared characteristics which facilitate common goals, leading to congruence of practice patterns; and social networks outside the organization, which support adoption of innovation.15–18 Without an understanding of the practice context, including the characteristics, and potential interactions, of those providing care, implementation of evidence-based interventions may fail.19 Thus, understanding the social and physical context in which rural oncologists care for cancer patients is critical to reducing geographic disparities.

Up to 80% of cancer care is delivered in non-academic settings.20 Because of the limited number of academic practices and their concentration in urban centers, most rural patients in the U.S. receive their care in community settings.21, 22 Community settings differ from academic settings in mission, organizational structure, and provider characteristics.23 Academic settings have a tripartite mission of clinical care, teaching and research,24 while community practices have a primary mission to provide clinical care, although some may be involved in teaching or research to a limited degree. Organizationally, community oncology practices tend to be smaller,25 and are less likely to have specialized providers26 than academic practices. Because of their mission and size, they are funded differently and experience different pressures to maintain financial viability.20 Physicians within them “select” between academic and community practice environments and may have different individual characteristics.23 All of these differences may be associated with quality of care.7–9, 27 However, the degree to which community practice locations in rural and urban areas, and the physicians within them, may differ is unknown, because any difference may be obscured by characteristics of academic medical centers and physicians, which are often outliers in their size, specialization and resources,20 and almost exclusively located in urban areas.

Thus, the objectives of this study were to 1) describe the characteristics of community oncologists and the community practice settings in which they deliver care and 2) compare characteristics of community cancer care delivery settings between rural and urban areas.

METHODS

Study design and data.

We conducted a cross-sectional study describing community practice site characteristics and the oncologists who deliver care in community practices, by rural and urban settings. We used data from the Physician Compare National Downloadable File.28 Physician Compare is a publicly-available dataset created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that provides near real time demographic information about U.S. physicians who billed for Medicare-covered services in the prior 12 months; we captured data from Physician Compare in May 2020. These data included detailed information about physicians’ practice locations, which could have been inpatient or outpatient facilities. The study was conducted under the umbrella of a wider protocol,29 approved by the University of Kansas Institutional Review Board.

Study sample.

We included oncologists practicing in a 13-state region in the Central U.S. (Arkansas, Colorado, Iowa, Indiana, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas, Wisconsin, and Utah) in which we were planning an intervention. We chose these states because they represent populations with higher than average rurality,30 have a disproportionately high burden of cancer morbidity,2 and are understudied in health services research, particularly with regard to cancer care delivery.31–33 Oncologists were identified based on self-reported primary specialty of medical oncology, hematology, or hematology/oncology. We excluded oncologists who billed for Medicare-covered services exclusively within academic practice settings. We defined academic practice settings as those with formal affiliations with a medical school designated by the Association of American Medical Colleges, a process consistent with the Joint Commission’s designation of academic practices.24 Community practices could include private practices, not-for-profit practices or hospitals, government-chartered facilities, or community hospitals. Practice locations were addresses at which the provider billed Medicare for care at least once during the study year and could include inpatient or outpatient settings.

Study measures.

Rurality was assessed at the physician and site location levels. Rurality was defined using the dichotomous Health Resources and Services Administration’s Federal Office of Rural Health Policy assignment of rural health service areas which determines eligibility for federal programs.34 The geographic schema blends components of several other schema, designating rural areas as those which are located in non-metropolitan areas (<50,000 individuals) and incorporates additional census tracts within large metropolitan areas which do not have easy geographical assess to central areas, according to the Goldsmith modification.35 Community practice sites were identified as rural if their physical street address was located in a ZIP code designated as rural by HRSA. All others were considered urban. Individual physicians were categorized as rural only, urban only, or both rural and urban (referred to as urban-rural spanning), based on the location of the practice site(s) from which they billed for their services during the 12-month observation period.

We assessed multiple characteristics of community oncologists, as well as the individual locations at which they billed for Medicare-covered services. We extracted or derived physicians’ sex, specialty, number of years in practice, the states in which they delivered care, and the number of affiliations each physician had with a) community practice locations; b) hospitals; and c) Medicare billing groups, defined as all the providers billing under a single Internal Revenue Service tax identification number (TIN). Practice locations were derived from addresses where the oncologist actually billed, whereas hospital affiliations were self-reported through Medicare.

For locations where community oncologists delivered care, we determined the organization size, defined as the total number of oncology and non-oncology providers delivering Medicare-covered services at each site, and the oncology group size, defined as the number of oncology providers. Both measures were derived from Physician Compare by counting the number of providers with the same physical address. We also assessed whether the practice site was located in a state that expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act, because Medicaid expansion has been associated with reduced cancer mortality.36 To assess potential for external referral networks and interdisciplinary boundary spanning, associated with diffusion of innovation,16 we created a practice-level measure of the number of distinct physician specialty types practicing at each site. We assumed the greater number of other specialties, the higher likelihood of innovation adoption.16 To assess homophily in training, associated with synchronization of practice patterns,37 we calculated the distinct medical schools attended by physicians within a site. We assume the greater the variation in training environments, the lower the homophily.

Analysis.

We geocoded each practice and mapped it onto a U.S. map, distinguishing between rural and urban practice locations. We used bivariate statistics to describe community oncologist and individual practice site characteristics by geographic indicators. We compared continuous and count characteristics of rural, urban, and urban-rural spanning oncologists using a Kruskal-Wallis rank test because assumptions for Analysis of Variance were violated. We compared characteristics of rural and urban practice locations using Fisher’s exact tests. We defined statistical significance at α=0.05. All analyses were performed in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics.

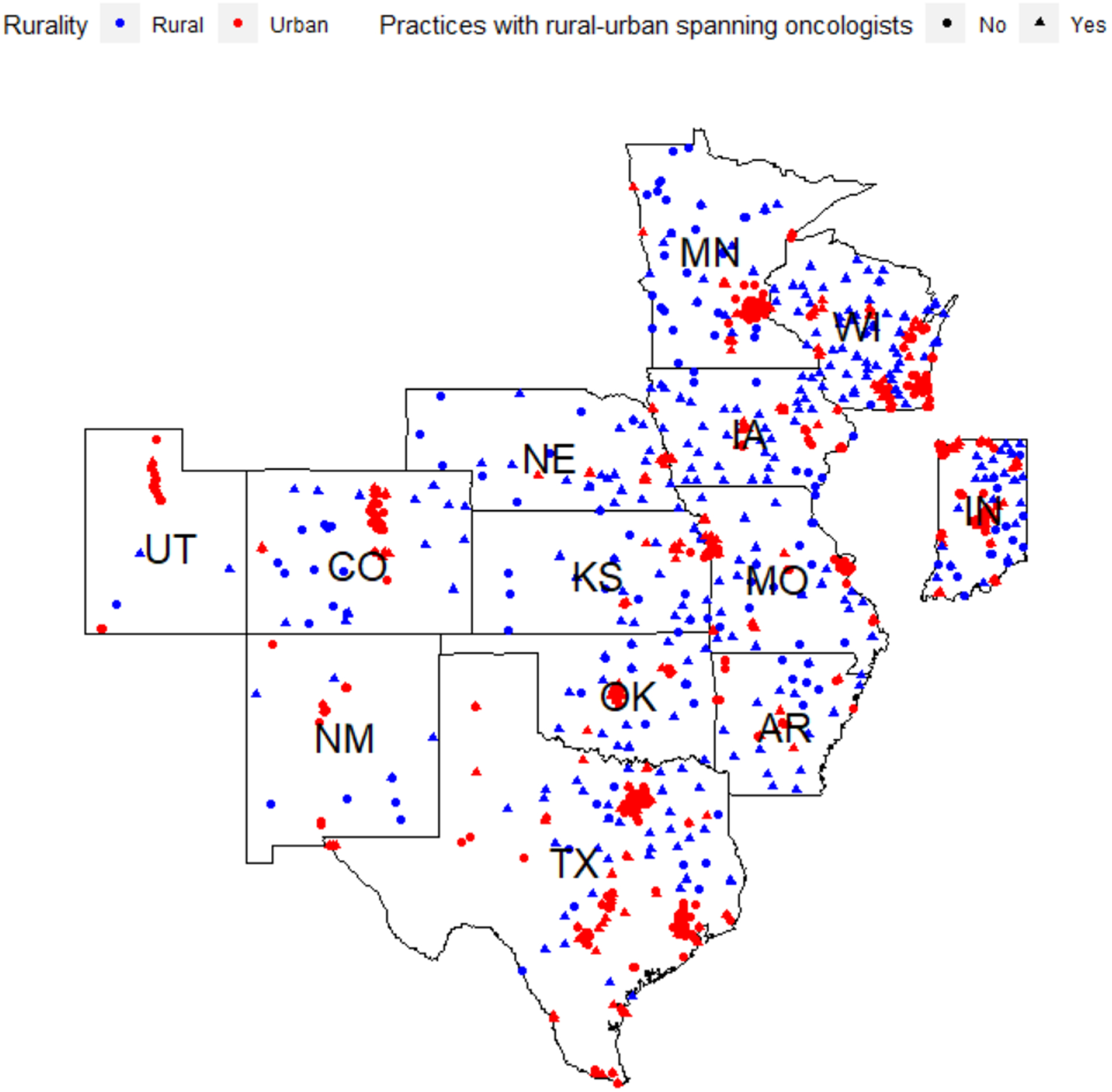

Our sample included 1963 unique community oncologists practicing in 1492 unique practice locations in the Central U.S. Among oncologists in the central U.S., 222 (11.3%) billed in rural settings only, 1326 (67.5%) in urban settings only, and 415 (21.1%) billed in both rural and urban settings (Table 1). Distributions of rural oncologists varied across states. Seven of the 13 states—Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, and New Mexico—had higher proportions of rural-only oncologists than other states. Seven states—Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin—had higher proportions of urban-rural-spanning oncologists. Only Texas and Utah had a markedly greater proportion of urban-only oncologists. Figure 1 shows the locations where the 1492 community oncologists provide care, distinguished by their rurality and demarcating the practice locations where care is provided by an urban-rural spanning oncologist.

Table 1:

Central US community oncologist characteristics in May 2020, by urban-rural care delivery setting

| (n=1963) | (n=222, 11.3%) | (n=1326, 67.5%) | (n=415, 21.1%) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 604 (30.8%) | 68 (30.6%) | 436 (32.9%) | 100 (24.1%) | 0.003 |

| Male | 1359 (69.2%) | 154 (69.4%) | 890 (67.1%) | 315 (75.9%) | |

| Primary Specialty | |||||

| Medical Oncology | 643 (32.8%) | 70 (31.5%) | 446 (33.6%) | 127 (30.6%) | 0.526 |

| Hematology | 41 (2.1%) | 2 (0.9%) | 30 (2.3%) | 9 (2.2%) | |

| Hematology/Oncology | 1279 (65.1%) | 150 (67.6%) | 850 (64.1%) | 279 (67.2%) | |

| Years in practice | |||||

| Median | 24 | 26 | 23 | 26 | <0.001 |

| Practice site locations | |||||

| 1 | 791 (40.3%) | 142 (64.0%) | 649 (48.9%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 2 | 406 (20.7%) | 52 (23.4%) | 256 (19.3%) | 98 (23.6%) | |

| 3 | 189 (9.6%) | 14 (6.3%) | 105 (7.9%) | 70 (16.9%) | |

| 4 | 191 (9.7%) | 9 (4.1%) | 125 (9.4%) | 57 (13.7%) | |

| 5 | 171 (8.7%) | 2 (0.0%) | 125 (9.4%) | 44 (10.6%) | |

| ≥6 | 215 (11.0%) | 3 (1.4%) | 66 (5.0%) | 146 (35.2%) | |

| Median | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Hospital affiliations | |||||

| 0 | 82 (4.2%) | 4 (1.8%) | 69 (5.2%) | 9 (2.2%) | |

| 1 | 448 (22.8%) | 32 (14.4%) | 380 (28.7%) | 36 (8.7%) | |

| 2 | 331 (16.9%) | 24 (10.8%) | 248 (18.7%) | 59 (14.2%) | |

| 3 | 338 (17.2%) | 51 (23.0%) | 212 (16.0%) | 75 (18.1%) | |

| 4 | 253 (12.9%) | 25 (11.3%) | 158 (11.9%) | 70 (16.9%) | |

| 5 | 511 (26.0%) | 86 (38.7%) | 259 (19.5%) | 166 (40.0%) | |

| Median | 3 | 3.5 | 2 | 4 | <0.001 |

| Practice billing group affiliations | |||||

| 1 | 1758 (89.6%) | 203 (91.4%) | 1249 (94.2%) | 306 (73.7%) | |

| 2 | 181 (9.2%) | 19 (8.6%) | 67 (5.1%) | 95 (22.9%) | |

| 3 | 21 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (0.8%) | 11 (2.7%) | |

| ≥4 | 3 (0.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.7%) | |

| Median | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Practice state* | <0.001 | ||||

| Arkansas | 62 (3.2%) | 7 (3.2%) | 41 (3.1%) | 14 (3.4%) | |

| Colorado | 146 (7.4%) | 18 (8.1%) | 112 (8.5%) | 16 (3.9%) | |

| Indiana | 186 (9.5%) | 33 (14.9%) | 113 (8.5%) | 40 (9.6%) | |

| Iowa | 90 (4.6%) | 14 (6.3%) | 41 (3.1%) | 35 (8.4%) | |

| Kansas | 71 (3.6%) | 17 (7.7%) | 35 (2.6%) | 19 (4.6%) | |

| Minnesota | 202 (10.3%) | 40 (18.0%) | 147 (11.1%) | 15 (3.6%) | |

| Missouri | 134 (6.8%) | 23 (10.4%) | 71 (5.4%) | 40 (9.6%) | |

| Nebraska | 54 (2.8%) | 18 (8.1%) | 19 (1.4%) | 17 (4.1%) | |

| New Mexico | 49 (2.5%) | 9 (4.1%) | 26 (2.0%) | 14 (3.4%) | |

| Oklahoma | 82 (4.2%) | 10 (4.5%) | 42 (3.2%) | 30 (7.2%) | |

| Texas | 711 (36.2%) | 24 (10.8%) | 549 (41.4%) | 138 (33.3%) | |

| Wisconsin | 170 (8.7%) | 12 (5.4%) | 99 (7.5%) | 59 (14.2%) | |

| Utah | 47 (2.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 38 (2.9%) | 7 (1.7%) |

Note: All cell contents represent frequencies with column percentages in “n (%)” format. Rural oncologists were defined as those delivering Medicare-covered services exclusively in community practice sites located in areas associated with Federal Office of Rural Health Policy designated rural zip codes.

Column percentages for practice state may sum to >100% because oncologists may practice in multiple states included in our analysis or have dual specialization.

Equivalence among groups for years in practice, practice site locations, hospital affiliation, and billing group affiliations are tested with a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test of medians.

Figure.

Practice Locations of 1,492 Community Oncologists in the Central U.S. by Rurality and Geographic Practice Spanning

Oncologist Characteristics.

Table 1 describes characteristics of oncologists by practice setting: rural only, urban only or urban-rural spanning. Overall, 30.8% of community oncologists in the region were female; a smaller proportion of female oncologists practiced only in rural sites (30.6%) than only in urban sites (32.9%) and the smallest proportion spanned rural and urban practices (24.1%) (p=.003). There was no evidence of a difference in the distribution of medical oncology subspecialty across geography (p=0.526), with one-third of oncologists reporting a primary specialty of medical oncology and the remainder reporting hematology-oncology or hematology alone. Community oncologists practicing in rural locations were in practice for longer (median years in practice: 26 for both rural-only and urban-rural spanning oncologists and 23 for urban-only oncologists; P<.001).

Oncologists’ Billing Patterns.

Most physicians (61.0%) billed Medicare at one or two locations, but rural-only physicians billed at fewer sites (Median practice locations: Rural-only=1; Urban-only=2; Urban-rural spanning=4; P<.001), while more than one third of urban-rural spanning physicians billed for oncology services at more than six practice locations within the study year (Table 1). Almost 29% of urban practicing oncologists had only one hospital affiliation, whereas a smaller proportion of rural-only oncologists had a single hospital affiliation. Both types of rural-serving oncologists had a higher median number of hospital affiliations than oncologists practicing in only urban areas (Median number of affiliations: Rural-only=3.5; Urban-rural spanning =4; Urban-only=2; P<.001). A higher proportion of urban-rural spanning oncologists had >1 billing group (P<.001). Median number of billing groups was 1 across all types of oncologists, but a lower proportion of urban-rural spanning oncologists had only one billing group (73.7% vs. 91.4% for rural-only and 94.2% for urban-only oncologists, rank score p<0.001).

Practice Characteristics.

Table 2 describes characteristics of locations where the oncologists billed. Among the 1492 community oncology practice locations, 505 (33.8%) and 987 (66.2%) were located in rural and urban settings, respectively. Most rural and urban practice sites had 6 or more unique community providers of any specialty who billed for Medicare-covered services from that site during the study period. However, a higher proportion of rural practice locations had only a single oncology provider serving the location with no other providers (11.7% rural solo oncologist locations vs. 4.0% urban solo oncologist locations; P<.001). There were multiple medical specialties represented at the majority of rural and urban practice locations, but a higher proportion of rural sites were single-specialty oncology groups (16.4%) compared to urban sites (9.4%) (P<.001). Of the groups, a higher proportion of rural locations (53.3%) were served by a single oncology provider than urban locations (30.7% , p<0.001). A significantly greater proportion of rural sites were made up of practicing oncologists trained in the same medical program, (63.0%) compared to urban sites (41.3%) (P<.001).

Table 2:

Characteristics of 1492 locations where community oncologists billed for Medicare-covered services, by urban-rural setting

| Total(n=1492 oncology-providing locations) | Rural(n=505) | Urban(n=987) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Based on 43957 Physicians Billing at n=1492 Practice Locations | ||||

| Practice size (all physicians, any specialty) | ||||

| 1 provider | 98 (6.6%) | 59 (11.7%) | 39 (4.0%) | <0.001 |

| 2–5 providers | 288 (19.3%) | 104 (20.6%) | 184 (18.6%) | |

| ≥6 providers | 1106 (74.1%) | 342 (67.7%) | 764 (77.4%) | |

| Specialty mix | ||||

| Oncology only | 176 (11.8%) | 83 (16.4%) | 93 (9.4%) | <0.001 |

| Multiple specialty | 1316 (88.2%) | 422 (83.6%) | 894 (90.6%) | |

| Medicaid expansion state | ||||

| Yes | 622 (41.7%) | 223 (44.2%) | 399 (40.4%) | 0.18 |

| No | 870 (58.3%) | 282 (55.8%) | 588 (59.6%) | |

| Based on 1963 Oncologists Billing at n=1492 Practice Locations | ||||

| Oncology Group Size | ||||

| 1 oncologist | 572 (38.3%) | 269 (53.3%) | 303 (30.7%) | <0.001 |

| 2–5 oncologists | 688 (46.1%) | 207 (41.0%) | 481 (48.7%) | |

| ≥6 oncologists | 232 (15.6%) | 29 (5.7%) | 203 (20.6%) | |

| Medical Schools Represented among Oncologists Within Site Location | ||||

| 1 | 726 (48.6%) | 318 (63.0%) | 408 (41.3%) | <0.001 |

| 2 | 380 (25.5%) | 119 (23.5%) | 261 (26.5%) | |

| 3 | 139 (9.3%) | 43 (8.5%) | 96 (9.7%) | |

| ≥ 4 | 247 (16.6%) | 25 (5.0%) | 222 (22.5%) | |

Note:

”Oncology only” refers to medical oncology, hematology, and hematology-oncology specialties, which were used to identify the study population of oncologists.

Practice size is all physicians (including non-oncologists) in a location

Table 3 provides a breakdown of the specialties represented in the subset of 1316 practice locations with multiple specialties represented. Except for pathology, which was represented in similar proportions in rural and urban multi-specialty settings, urban practice locations had higher proportions of each cancer specialty, as well as pediatrics, geriatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and internal medicine. Family medicine was the only specialty represented in a greater proportion at rural locations.

Table 3.

Distribution of Medical Specialties in the Subset of 1316 Multi-specialty Group Practices in the Central U.S. where Oncologists Provide Care

| Total | Rural Practice Locations | Urban Practice Locations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | P-value | |||

| Multispecialty Group Practices | 1316 (88.2%) | 422 (83.6%) | 894 (90.6%) | |

| Specialty Mix | ||||

| Surgical Oncology | 111 (8.4%) | 12 (2.8%) | 99 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Radiation Oncology | 384 (29.2%) | 98 (23.2%) | 286 (32.0%) | |

| Pathology | 162 (12.3%) | 54 (12.8%) | 108 (12.1%) | |

| Medical Genetics & Genomics | 3 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.3%) | |

| Urology | 883 (67.1%) | 252 (59.7%) | 631 (70.6%) | |

| Gastroenterology | 395 (30.0%) | 84 (19.9%) | 311 (34.8%) | |

| Pulmonary Disease | 405 (30.8%) | 105 (24.9%) | 300 (33.6%) | |

| Otolaryngology | 327 (24.8%) | 100 (23.7%) | 227 (25.4%) | |

| Thoracic Surgery | 150 (11.4%) | 21 (5.0%) | 129 (14.4%) | |

| Colorectal Surgery | 108 (8.2%) | 8 (1.9%) | 100 (11.2%) | |

| Pediatric Medicine | 196 (14.9%) | 34 (8.1%) | 162 (18.1%) | |

| Geriatric Medicine | 83 (6.3%) | 6 (1.4%) | 77 (8.6%) | |

| Internal Medicine | 799 (60.7%) | 246 (58.3%) | 553 (61.9%) | |

| Family Medicine | 749 (56.9%) | 269 (63.7%) | 480 (53.7%) | |

| OB/GYN | 502 (38.1%) | 145 (34.4%) | 357 (39.9%) | |

Column percentages for specialty may sum to >100% because multiple specialists may practice in a location or have dual specialization. Fisher’s Exact test assumptions are not met due to specialists practicing in multiple locations.

DISCUSSION

We described community oncologist and practice location characteristics for nearly 2000 community oncologists practicing across 1492 unique practice locations in the Central U.S. We sought to assess how rural and urban community practice locations and oncologists may differ from each other. We found that rural-serving community oncologists in this area, whether rural-only or urban-rural spanning, are more likely to be male, have greater number of years of experience, and have more hospital affiliations than urban-only physicians. Our analysis also provides insights into what is distinct about urban-rural spanning physicians compared to urban physicians (number of practice sites and billing groups and an even higher proportion of male oncologists). Further, our analysis suggests two distinct styles of rural cancer care delivery: (1) A higher proportion of rural oncologists in the Central U.S. are in solo provider practices, bill under a single entity, and, in a given year, bill from 1–2 locations, although they maintain a greater number of hospital affiliations, remaining fairly isolated from other physicians, compared to urban community oncologists; (2) In contrast, urban-rural spanning oncologists provide care at a large number of locations and under a greater number of different billing groups, potentially interacting with many different physicians. The patterns of geographic boundary spanning appear to aggregate at the state levels, suggesting dominant models of rural care provision (rural only or urban-rural spanning) by state.

Our results are similar in some ways to studies that include academic physicians. Differences in demographic characteristics of community oncologists in rural and urban areas mirrors that of all physicians, inclusive of academic practice, with patterns of physician sex and practice experience significantly varying between rural-serving and urban oncologists.7, 38 As with studies inclusive of academic practices,25, 39 rural community oncology practice locations are smaller than urban community oncology locations and are more likely to be solo oncology locations. However, our work extends understanding of rural community practice locations in that we demonstrate that, beyond the solo providers, many rural oncology care delivery sites do include multiple specialties. These may represent private multi-specialty groups like some found in Kansas40 or they may represent hospitals, whether or not the oncologists are employees. Nonetheless, the specialty mix appears different between rural and urban multi-specialty sites. Others have reported that specialists are more likely to locate in urban areas,38 but our findings demonstrate the effect this selection has on the practice settings in rural communities. A smaller proportion of specialists of any kind (except pathologists) practice in rural settings, which could limit multi-disciplinary cancer care. Moreover, the mix and volume of specialties within the multi-specialty sites that are in rural settings appear to be different. Rural multi-specialty locations have a higher concentration of family medicine physicians, potentially limiting the organization of tumor boards, which are associated with higher quality cancer care,41–43 and limiting the breadth and depth of referral networks.8, 44 It may also deter use of aggressive treatments in patients with multiple comorbidities. Because inter-provider communication is shaped by situational awareness,45 oncologists in rural multi-specialty environments may know more about, or give more weight to, the impact of a cancer patients’ other chronic conditions, and know less about or give less weight to the potential benefits of aggressive cancer treatment options when considering treatment options.

Although we found significant differences among geographic samples in this descriptive analysis, whether these characteristics influence quality of care has not been tested. Nonetheless, we can theorize how physician and practice characteristics we found may impact care quality for these two different styles of rural cancer care delivery. First, both types of rural-serving physicians have been in practice longer and are more likely to be male. Years of experience has been thought to be associated with clinical inertia, with approximately 20 years serving as a cut point for a decline in quality of care, although this relationship has not always held true.7, 8 In addition, although not affecting acute care outcomes,10 female physicians have been shown to engage in longer and more patient-centered communication,9 which may impact chronic disease outcomes46 such as cancer treatment. These characteristics may suggest that support for innovation adoption and patient-centered care may be needed among rural oncologists. Our dataset did not include other important physician factors shown to affect quality of care, particularly board certification,44 which could impact rural communities disproportionately and deserves further study. Still, these considerations of individual characteristics may also be influenced by practice dynamics, which have been demonstrated to have a more consistent and larger impact on quality, particularly for acute and chronic disease management.44, 47 Most rural-only physicians provide care at one or two locations typically affiliated with large groups of non-cancer specialists, many of whom share training backgrounds. Although shared training experiences promote shared cognition which can facilitate internal coordination and synchronous practice, they do not necessarily promote adoption of new practices, especially if external networks are limited, as in rural-only practices. Diffusion of innovation is a social process that occurs through the adopter’s communication network.48 Closed networks, such as solo practice settings, homophilious single-specialty groups, or even larger multi-disciplinary groups comprised of members with similar backgrounds and little cross-practice interaction, may limit the introduction of new ideas and approaches. In contrast, the practice sharing behavior of urban-rural spanning oncologists may facilitate sharing of ideas.

Urban-rural spanning physicians may face different challenges to delivering high quality cancer care, however. Although they are more likely to be introduced to innovations by the higher exposure to more physicians and other cancer specialists in their urban practice, they also travel, provide care on a part-time basis, and face a wide array of physical environments. Similar to other studies,49 we found that approximately 60% of oncologists in the central U.S. practice in multiple locations. However, to our knowledge, no previous research has acknowledged the large number of practice sites some physicians cover in a single year. More than a third are providing cancer care in six or more locations and the average number of locations they serve is five. The number of practice settings, hospital systems and billing groups could greatly increase complexity of care delivery, limit standardization of practice, and disrupt behavioral regulation strategies to prompt guideline-based care. Limited time at a given practice site could also dampen the physicians’ motivation and investment in facilitating high standards of care and structural changes to ensure evidence-based practice. Finally, care could be fractured if a high number of unique oncologists are providing sporadic care from these clinics. Nonetheless, their effect on the practices they visit is unknown. Additional research is needed to compare the level of quality practice-spanning physicians achieve at each location and to assess whether and when they spark innovation in care delivery, widen referral networks, or transport best practice to the sites they visit.

Our analysis differs from many in that it acknowledges the existence of urban-rural spanning oncologists, which has not often been studied as a unique practice context. Although traveling oncologists have been recognized as delivering cancer care for more than 30 years in Iowa,50 they rarely are acknowledged in cancer care delivery research. Workforce studies tend to merely count physicians;51 most quality of care analyses attribute physicians to their main practice site;25 and evaluations of rural care delivery tend to overlook this practice style,52 rendering these physicians invisible. That 21% of oncologists practice in both rural and urban locations is not trivial—almost two-thirds of rural-serving oncologists span locations, outnumbering rural-only oncologists—and justifies a research agenda. First, our analysis does not explain why oncologists are spanning communities. Whether this is explained by moonlighting, occasional vacation coverage, or driven by regular outreach to multiple practices across geographic boundaries is not known, but could influence quality of care. Moreover, understanding to whom they provide access by describing the kinds of rural populations they serve—merely wealthy retirement communities or rural populations with greatest need—should be assessed. Whether urban-rural spanning providers can be leveraged for disseminating innovations and how best to support them also should be studied. For example, network analyses that compare the quality and breadth of referral networks of rural-only, urban-rural spanning, and non-rural oncologists could reveal key contributors to differences in quality of care as other research suggests that referral networks may be a key contributor to quality of cancer care.8, 44 At the least, understanding their involvement in clinical trial research bases or other research networks may provide some guidance about the potential impact of the care they deliver. Nonetheless, rather than consider their unique circumstances an anomaly, intentionally targeting the 21% of oncologists who span practice settings could potentially have a large impact on rural care delivery, particularly in states where the practice style predominates. Acknowledging the marked increase in access that they provide,53, 54 their growth in recent decades,53 the variety of inpatient and outpatient locations in which these oncologists practice, and unique care delivery needs associated with it will likely be essential to closing geographic disparities. Further, acknowledging that as many as one in five oncologists are practicing as urban-rural-spanning physicians suggests that we may need to better prepare oncologists in training for this possibility and provide them with the resources and tools to provide mobile care so that they not only expand access to care but ensure they increase the quality of that care.

Finally, our study identified more rural oncology care delivery locations in the central U.S. than other national estimates, tempering, but not erasing, recent concerns about the mismatch of the cancer care workforce to the cancer burden in the U.S.25, 55 There are two key differences that may explain this. We identified oncologists at their practice location, rather than through their billing group, which is more centralized, and may obscure some of the care being delivered in rural communities. By assessing where they bill, rather than their home base, we found that one third of oncologists in the central U.S. are providing at least some care in rural areas, Secondly, we used a different geographic schema to assign rurality, which has been shown to more generously classify rural locations as rural.56 Our approach suggests that more cancer care may be delivered in rural communities than previously considered and underscores the need to recognize these different delivery modes in research, training, and implementation strategies.

Limitations

Our work is not without limitations. First, we limited our study to 13 states in the central U.S., which has a particular socio-geographic context, so it should not be construed to be representative of the entire U.S., especially since regional variations have been noted.57 In addition, we identified oncologists and practice locations based on Medicare billing. While considered to be accurate, as it is used for payment, we would not expect it to identify oncologists providing care exclusively to children or other non-Medicare billing oncologists. Relatedly, the dataset represents physicians who billed Medicare at least once in the study year. It does not indicate how much care they provide or whether the volume of service they provide meets the needs of the communities they serve. Likewise, we did not assess the burden of cancer in the area studied. Shih et al., have demonstrated a supply mismatch between the cancer care delivery workforce and the burden of cancer in the U.S., i.e., areas with most need are least likely to have oncology providers, resulting in further travel distances or forgone care for mostly rural patients.55 Because we identified oncologists by where they practice rather than their primary practice location, our analysis suggests that the degree of the supply mismatch may not be as great as Shih et al, estimated. Nonetheless, the supply mismatch implies that both rural and urban-rural spanning oncologists may be faced with high demand and the degree to which urban-rural spanning oncologists are extending care to high cancer burden areas should be explored.

The unique contribution of this study is the ability of the data resource used to provide insights into the patterns of cancer care delivery and the groupings of providers by organizations and locations, rather than merely the individual attributes of the providers delivering care. Nonetheless, the Physician Compare dataset only offers a limited number of physician and practice characteristics. Future studies should assess additional patient, physician, and organizational attributes, specifically in the context of rural cancer care delivery, using a wider theoretical model of care quality inclusive of the technical, relational, process, and patient-evaluated measures of quality, as relationships between attributes and quality could depend on how quality is measured. For example, inclusion of provider race and ethnicity could allow examination of the differences in quality based on provider-patient racial concordance. Inclusion of place of residency could allow a better assessment of training homophily. Release of licensed data available to CMS but not included in Physician Compare, such as board certification58 could strengthen the websites’ ability to direct the public to high quality care providers.

Finally, we studied rural physicians, not the rural population. Although patient characteristics have been shown to be less influential in affecting quality of acute and chronic care, such as cancer treatment, than in screening and preventative care,44, 47 understanding the patient panels each type of rural-serving oncologist treats remains an important aspect of assessing quality of cancer care in rural areas. Levels of adherence to screening and preventive care could raise acuity of cancer diagnoses and decrease eligibility for certain treatments and potential interactions of patient characteristics and rurality have not been well studied,57 although our team is addressing this in forthcoming work. Still, the proportion of physicians providing care in a geographic region says little about the proportion of the population they serve,38 so noting that 30% of oncologists provide care to approximately 20% of the population does not necessarily mean that coverage is adequate or signal that there is an inefficient oversupply of physicians. Future work should include patient-level characteristics, particularly indicators of social determinants of health, as we continue to explore the potential differential impact on quality of care among these three provider types to better understand the need to include patient-level behavioral risk factors adjustment in quality reporting datasets.

CONCLUSION

Rural-serving community oncologists differ from urban community oncologists in characteristics that may affect quality of cancer care and adoption of innovation. Although access to cancer care in rural communities may be higher than other studies have shown, we identified two distinct styles of care delivery in rural communities that likely present challenges for quality of care in different ways. Different interventions to improve care quality may be needed to target relatively isolated rural-only oncologists than those needed for urban-rural spanning physicians who travel to numerous sites to deliver care. Future studies should define oncologists by their geographic practice style to compare their impact and identify what may be needed to support the care they deliver.

Funding sources:

This research was supported by the Kansas Institute for Precision Medicine funded by NIGMS (P20GM130423).

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no real or perceived conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henley SJ, Anderson RN, Thomas CC, Massetti GM, Peaker B, Richardson LC. Invasive Cancer Incidence, 2004–2013, and Deaths, 2006–2015, in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Counties - United States. MMWR Surveill Summ. Jul 07 2017;66(14):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver KE, Geiger AM, Lu L, Case LD. Rural-urban disparities in health status among US cancer survivors. Cancer. Mar 01 2013;119(5):1050–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spencer JC, Wheeler SB, Rotter JS, Holmes GM. Decomposing Mortality Disparities in Urban and Rural U.S. Counties. Health Serv Res. Dec 2018;53(6):4310–4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger JM, Moseley A, Symington B, Chavez-MacGregor M, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Geographic distribution and survival outcomes for rural cancer patients treated in clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology. May 20 2018;36(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villanueva C, Chang J, Ziogas A, Bristow RE, Vieira VM. Ovarian cancer in California: Guideline adherence, survival, and the impact of geographic location, 1996–2014. Cancer Epidemiol. Dec 2020;69:101825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenbaum A, Wiggins C, Meisner AL, Rojo M, Kinney AY, Rajput A. KRAS biomarker testing disparities in colorectal cancer patients in New Mexico. Heliyon. Nov 2017;3(11):e00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. Feb 15 2005;142(4):260–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellis SD, Nielsen ME, Carpenter WR, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist overuse: urologists’ response to reimbursement and characteristics associated with persistent overuse. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. Apr 7 2015;18(2):173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. Aug 14 2002;288(6):756–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, Orav EJ, Blumenthal DM, Jha AK. Comparison of Hospital Mortality and Readmission Rates for Medicare Patients Treated by Male vs Female Physicians. JAMA Intern Med. Feb 1 2017;177(2):206–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freiman MP. The rate of adoption of new procedures among physicians. The impact of specialty and practice characteristics. Med Care. Aug 1985;23(8):939–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. Apr 23 2011;6:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nilsen P, Bernhardsson S. Context matters in implementation science: a scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Serv Res. Mar 25 2019;19(1):189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williamson OE. The Economics of Organization - the Transaction Cost Approach. American Journal of Sociology. 1981;87(3):548–577. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82(4):581–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson EC, Batalden PB, MM G. Quality by Design: A Clinical Microsystems Approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhoeven DC, Chollette V, Lazzara EH, Shuffler ML, Osarogiagbon RU, Weaver SJ. The Anatomy and Physiology of Teaming in Cancer Care Delivery: A Conceptual Framework. J Natl Cancer Inst. Apr 6 2021;113(4):360–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards N, Barker PM. The importance of context in implementation research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. Nov 1 2014;67 Suppl 2:S157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kirkwood MK, Hanley A, Bruinooge SS, et al. The State of Oncology Practice in America, 2018: Results of the ASCO Practice Census Survey. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2018;14(7):e412–e420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williamson HA Jr., Hart LG, Pirani MJ, Rosenblatt RA. Market shares for rural inpatient surgical services: where does the buck stop? J Rural Health. Spring 1994;10(2):70–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Wang D, Demidenko E, Goodman D. Geographic access to cancer care in the U.S. Cancer. Feb 15 2008;112(4):909–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Desch CE, Blayney DW. Making the Choice Between Academic Oncology and Community Practice: The Big Picture and Details About Each Career. J Oncol Pract. May 2006;2(3):132–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joint Commission International. Academic Medical Center Hospital Accreditation. https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/accreditation/accreditation-programs/academic-medical-center/.

- 25.Kirkwood MK, Hanley A, Bruinooge SS, et al. The State of Oncology Practice in America, 2018: Results of the ASCO Practice Census Survey. J Oncol Pract. Jul 2018;14(7):e412–e420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levit LA, Byatt L, Lyss AP, et al. Closing the Rural Cancer Care Gap: Three Institutional Approaches. JCO Oncol Pract. Jul 2020;16(7):422–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis SD, Karim SA, Vukas RR, Marx D, Uddin J. Four Needles in a Haystack: A Systematic Review Assessing Quality of Health Care in Specialty Practice by Practice Type. Inquiry. Jan-Dec 2018;55:46958018787041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Compare National Downloadable Data Files. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/?redirect=true. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- 29.Ball J, Thompson J, Wulff-Burchfield E, et al. Precision community: a mixed methods study to identify determinants of adoption and implementation of targeted cancer therapy in community oncology. Implementation Science Communications. 2020/08/31 2020;1(1):72. [Google Scholar]

- 30.United States Census Bureau. Geographic Areas and Rural Data: Nation and Region. Rural America [https://gis-portal.data.census.gov/arcgis/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=7a41374f6b03456e9d138cb014711e01. Accessed January 21, 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the Case for Investment in Rural Cancer Control: An Analysis of Rural Cancer Incidence, Mortality, and Funding Trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. Jul 2017;26(7):992–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthukrishnan M, Sutcliffe S, Hunleth JM, Wang JS, Colditz GA, James AS. Conducting a randomized trial in rural and urban safety-net health centers: Added value of community-based participatory research. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. Jun 2018;10:29–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorospe JR. Introducing the Institutional Development Award (IDeA) Program. NGMS Feedback Loop Blog--National Institute of General Medical Sciences [Accessed January 21, 2020, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Resources & Services Administration. Defining Rural Population. https://www.hrsa.gov/rural-health/about-us/definition/index.html.

- 35.Goldsmith HF, Puskin DS, Stiles DJ. Improving the Operational Definition of “Rural Areas” for Federal Programs. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration,; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lam MB, Phelan J, Orav EJ, Jha AK, Keating NL. Medicaid Expansion and Mortality Among Patients With Breast, Lung, and Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. Nov 2 2020;3(11):e2024366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA. Sep 23 2009;302(12):1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG. Physicians and rural America. West J Med. Nov 2000;173(5):348–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Squires D, Blumental D. Do Small Physician Practices Have a Future? In: The Commonwealth Fund, ed. Improving Healthcare Quality. Vol 2021. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ashley Clinic. About Us. Ashley Clinic [https://www.ashleyclinic.com/about-us/, 2021.

- 41.Quyyumi FF, Wright JD, Accordino MK, et al. Factors Associated with Multidisciplinary Consultations in Patients with Early Stage Breast Cancer. Cancer Invest. 2019;37(6):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Specchia ML, Frisicale EM, Carini E, et al. The impact of tumor board on cancer care: evidence from an umbrella review. BMC Health Serv Res. Jan 31 2020;20(1):73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samarasinghe A, Chan A, Hastrich D, et al. Compliance with multidisciplinary team meeting management recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. Dec 2019;15(6):337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reid RO, Friedberg MW, Adams JL, McGlynn EA, Mehrotra A. Associations between physician characteristics and quality of care. Arch Intern Med. Sep 13 2010;170(16):1442–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Communication Between Clinicians. PSNet: Patient Safety Network. Vol 2021. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berthold HK, Gouni-Berthold I, Bestehorn KP, Bohm M, Krone W. Physician gender is associated with the quality of type 2 diabetes care. J Intern Med. Oct 2008;264(4):340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB. Delivery of preventive services to older adults by primary care physicians. JAMA. Jul 27 2005;294(4):473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Acemoglu D, Asuman Ozdaglar, Yildiz E. Diffusion of Innovations in Social Networks. Paper presented at: 50th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC-ECC), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xierali IM. Physician Multisite Practicing: Impact on Access to Care. J Am Board Fam Med. Mar-Apr 2018;31(2):260–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gruca TS, Nam I, Tracy R. Trends in medical oncology outreach clinics in rural areas. J Oncol Pract. Sep 2014;10(5):e313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stitzenberg KB. Oncology Workforce Studies: Moving Beyond the Head Count. J Oncol Pract. Jan 2015;11(1):38–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Campbell NC, Ritchie LD, Cassidy J, Little J. Systematic review of cancer treatment programmes in remote and rural areas. Br J Cancer. Jun 1999;80(8):1275–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ward MM, Ullrich F, Matthews K, et al. Access to chemotherapy services by availability of local and visiting oncologists. J Oncol Pract. Jan 2014;10(1):26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tracy R, Nam I, Gruca TS. The influence of visiting consultant clinics on measures of access to cancer care: evidence from the state of Iowa. Health Serv Res. Oct 2013;48(5):1719–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shih YT, Kim B, Halpern MT. State of Physician and Pharmacist Oncology Workforce in the United States in 2019. JCO Oncol Pract. Jan 2021;17(1):e1–e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellis SD, Castro KM, Adjei BA, Sesay D, Geiger AM. Rural Practice Participation in Cancer Care Delivery Research within the NCI Community Oncology Research Program. AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting. Online: AcademyHealth; Under Review. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson JA, Chollet-Hinton L, Keighley J, et al. The need to study rural cancer outcome disparities at the local level: a retrospective cohort study in Kansas and Missouri. BMC Public Health. Nov 24 2021;21(1):2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Services CfMaM. Provider Data Catalog: Doctors and Clinicians Data Dictionary: Performance Year 2019. In: Services CfMaM, ed. Vol Performance Year 2019. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2019. [Google Scholar]