Abstract

The specificity of antibody binding to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharides (Pnc PSs) measured by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) was studied by inhibition of antibody binding by homologous and heterologous PSs. We found extensive cross-reactivity of antibody binding to type 6B, 19F, and 23F PSs but not to type 14 PS, even after treatment with cell wall PS (CPS). The cross-reactive antibody was highly prevalent in sera of infants and adults with naturally acquired antibody, but not in sera of infants and adults immunized with pneumococcal vaccines. However, a type 11A antibody response was seen after vaccination with heterologous PSs. Monoclonal antibodies prepared against a type 6B PS-tetanus toxoid conjugate recognized also other than the specific type of PS in the EIA, implying the possible existence of a cross-reactive epitope. Remarkable differences in specificity among type 6B PS preparations from different manufacturers were found. Moreover, different lots of type 11A PS from the same manufacturer showed differences in specificity. The results suggest that some Pnc PS preparations may contain cross-reactive epitopes or impurities, other than CPS, that are common to many types of Pnc PS. The specificity of antibodies, especially in sera from nonimmunized subjects, measured by EIA can be questioned.

Streptococcus pneumoniae has been divided into 90 different serotypes on the basis of the structure of the polysaccharide (PS) capsule (8). Serologically related PSs are designated as serogroups on the basis of their reactions with cross-reactive antibodies in rabbit typing antisera (9, 14). Antibodies to pneumococcal (Pnc) capsular PSs are thought to be group specific and to provide immunity against homologous and cross-reactive serotypes within a serogroup. Some Pnc PSs, for instance 6B and 6A, are structurally very similar and are thought to result in cross-immunity (22). However, there is evidence that antibodies induced by 6B are not always functional with 6A (19).

Immunogenicity of pneumococcal vaccination is traditionally assessed by estimating the type-specific antibody response by radioimmunoassay or, more recently, by enzyme immunoassay (EIA). There is much interest in new pneumococcal conjugate vaccines that are in phase III studies. Specific and accurate assays are needed to define serological correlates of protection to be used in future vaccine development and quality control. It is known that Pnc PS preparations contain impurities such as non-type-specific cell wall PS (CPS) (27). There is evidence that antibodies to CPS do not confer protection (16) and thus should be preadsorbed to optimize the specificity of the EIA (6, 12, 17). Although efforts have been made to improve the EIA methodology (B. Plikaytis, G. Carlone, D. Goldblatt, and participating laboratories, Abstr. Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., abstr. P 52, p. 71, 1998), there is evidence of a low correlation between the antibody concentration measured by EIA and functional measurements of antibodies (19, 25), especially in sera of nonvaccinated individuals (3).

Cross-reactions are known to occur between pneumococci and other streptococci with chemically similar PS capsules (13). Since PSs from many sources are composed of common monosaccharides, cross-reactivity is not unexpected (23). Also, conformational epitopes in polysaccharides have been described as antigenic determinants (30). Structures in pneumococcal PSs that are cross-antigenic among serogroups have been demonstrated (7). Furthermore, an infection by one serotype of S. pneumoniae has previously been shown to induce the production of an antibody that is reactive with other serotypes (heterotypic antibody) (18), thus implying possible cross-reactivity among pneumococcal serotypes. More recently, several groups have reported non-type-specific pneumococcal antibodies (4, 31; M. H. Nahm, Abstr. Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., p. 59, 1998).

We have found similar evidence of cross-reactivity between several groups of Pnc PSs, even after treatment with CPS. Because pneumococcal-antibody measurements should be type specific, we have further characterized the nature of the cross-reactivity. We have examined the prevalence, nature, and opsonophagocytic capacity of these cross-reactive pneumococcal antibodies in sera from infants and adults immunized with pneumococcal vaccines and from infants and adults with naturally acquired antibody. To determine whether the antibody binding specificities of the different Pnc PS preparations were equivalent, some of the experiments were done with preparations from four different sources. Furthermore, we have similarly tested the cross-reactivity of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) prepared against Pnc PS.

(Part of this material was presented at the International Symposium on Pneumococci and Pneumococcal Diseases, Helsingør, Denmark, 13 to 17 June 1998.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pneumococcal antisera.

Sera used in the experiments are described in Table 1. For inhibition EIAs, serum samples obtained before (day zero) and 1 month after (day 28) vaccination of 23 healthy adults were used. Eleven subjects were vaccinated with a 23-valent PS vaccine (PS; Merck, Sharp & Dohme, West Point, Pa.). Twelve subjects received a diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine (PncD; Connaught Laboratories Inc., Swiftwater, Pa.) (20). In addition, 24 healthy infants were vaccinated at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with a conjugate of diphtheria toxoid and Pnc PSs 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F (PncD01; Connaught Laboratories Inc.) (1), and sera collected at 7 months were used. To study naturally acquired pneumococcal antibodies, sera from 49 nonimmunized infants, obtained at 6, 7, or 14 months of age, were available (1).

TABLE 1.

Pneumococcal antisera used in the inhibition EIA and in the EIA for antibody to 11A PS

| EIA type | Vaccine | Vaccinees | No. of serum specimens available | Specimens collected at: |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibition | PS | Adults | 11 | d0,a d28b |

| PncD | Adults | 12 | d0,a d28b | |

| PncD at 2, 4, and 6 mo | Infants | 24 | 7 mo | |

| None | Infants | 49 | 6, 7, 14 moc | |

| Specific for IgG to 11A PS | PncD at 2, 4, and 6 mo; PncD at 14 mo | Infants | 12 | 14 mo (pre), 15 mo (post) |

| PncD at 2, 4, and 6 mo; PS at 14 mo | Infants | 11 | 14 mo (pre), 15 mo (post) | |

| PncD/T conjugate | Adults | 11 | d0, d28 | |

| PS | Adults | 10 | d0, d28 | |

| PRP-D/PRP-D and MenACYW | Adults | 12 | d0, d28 |

d0, day zero (adult preimmunization sera).

d28, day 28 (adult postvaccination sera).

Referred to as sera from nonimmunized infants.

For measurement of antibody responses to type 11A PS, we had serum samples from 23 healthy infants vaccinated at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with a conjugate of diphtheria toxoid and Pnc PSs 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F (PncD10; Connaught Laboratories Inc.) (1). Twelve of these infants were boosted at 14 months of age with a conjugate of diphtheria toxoid and Pnc PSs 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F (PncD03; Connaught Laboratories Inc.), and 11 were given the PS vaccine (1). Sera obtained before (at 14 months) and after (at 15 months) the boosting were included. In addition, we included preimmunization (day zero) and postimmunization (day 28) serum samples from 10 healthy adults immunized with Pnc PSs 1, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F conjugated to either tetanus toxoid or diphtheria toxoid (PncD/T conjugate; Pasteur Mérieux Sérums & Vaccins, Marcy l'Etoile, France, and Connaught Laboratories Inc.) and from 10 healthy adults vaccinated with a second 23-valent PS vaccine (Pneumo-23; Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, Marcy l'Etoile, France) (T. Wuorimaa, H. Käyhty, O. Leroy, and J. Eskola, Abstr. Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., abstr. P 106, p. 77, 1998). For controls, preimmunization (day zero) and postimmunization (day 28) sera of 12 adults vaccinated with either a Haemophilus influenzae type b-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine (PRP-D) (11) or PRP-D and MenACYW, but not with any pneumococcal vaccine, were included from our previous studies.

MAbs.

MAbs were made at the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands) by immunizing NIH mice twice with Pnc PS 6B or 14 conjugated to tetanus toxoid (5, 24). MAbs were of the immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype and did not react with a CPS preparation from Statens Seruminstitut (Copenhagen, Denmark). The specificity of the MAbs was tested by EIA using purified pneumococcal PSs and by colony blotting. The affinity of the MAbs was tested as described previously (2).

Reagents.

Unless otherwise stated, capsular polysaccharides of S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 11A, 14, 18C, 19F, and 23F were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.). Two lots of 11A PS were used, lot 79268 and lot 963596. In addition, PS 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F preparations from three other manufacturers, namely the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (Bilthoven, The Netherlands), SmithKline Beecham (Rixensart, Belgium), and Pasteur Mérieux Connaught were used. For simplicity, these manufacturers are referred to as A, B, and C, in random order. CPS used for adsorption was from Statens Seruminstitut. Capsular PSs from group A meningococcus (MenA) and from H. influenzae type b (PRP) were obtained from Connaught Laboratories Inc.

Colony blot analysis of MAb binding.

Colony blotting was done by a modification of a method described previously (15). S. pneumoniae serotypes 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F (reference strains received from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.), as well as serotypes 6A and 11A (reference strains from the World Health Organization [WHO] Collaborating Center for Reference and Research on Streptococci, Praque, Czech Republic), were grown in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract. The bacterial concentration was determined by performing viable-cell counts on blood agar plates. Bacterial suspensions were plated onto Todd-Hewitt–yeast extract plates. The colonies were blotted onto nitrocellulose filter papers, which were placed in blocking buffer (1% bovine serum albumin [Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.] in phosphate-buffered saline) containing MAb 10H8/6B or 1F6/14. A peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse Ig (Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) was used as a conjugate.

EIA.

An EIA for IgG antibodies to Pnc PS was performed as described earlier by Käyhty et al. (10) with one exception; a different conjugate, an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-human IgG (Sigma Immunochemicals, St. Louis, Mo.), was used. The results are expressed as micrograms of protein per milliliter calculated on the basis of the officially assigned IgG values for the 89-SF reference serum (21; S. A. Quataert, C. S. Kirch, K. Diakun, and D. V. Madore, Abstr. Int. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., abstr. P28, p. 67, 1998). The same coating concentrations were used for PS of the same serotype regardless of the source of PS. The EIA for IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies to Pnc PS was performed as previously described (26) except that the monoclonal mouse anti-human IgG2 antibody (HP6002) was received from Scott Johnson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Inhibition EIA.

A single dilution of each serum sample was used in the inhibition EIA. Sera were diluted 1:100 or more, to yield an optical density (OD) at 405 nm of approximately 1.5, in 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) in phosphate-buffered saline containing 10 μg of CPS per ml. After distribution of the diluted sera into separate glass tubes, 30 μg of either homologous or heterologous capsular PSs was added per ml and the tubes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After inhibition, the EIA for IgG, and in some experiments for IgG1 and IgG2, was performed as described above. The results are expressed as ODs at 405 nm, determined as an average of duplicate results after correction by subtracting the OD value of the blank. An equally diluted serum sample inhibited with only CPS served as a normal-signal control. The percentage of inhibition was calculated as follows: (OD of antibodies bound after inhibition with PS/OD of antibodies bound after inhibition with CPS only) × 100. The success of adsorption of antibodies to CPS was determined by testing serum samples in wells coated with CPS (12). To examine the effect of the PS concentration used for inhibition, an inhibition EIA was done with two adult prevaccination sera, using 1:100 dilutions of sera and eight different concentrations (from 0 to 100 μg/ml) of Pnc PSs 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F for inhibition.

Opsonophagocytosis assay.

Opsonophagocytic activities of the samples were determined by a modification of the method described earlier by Romero-Steiner et al. (3, 25). Instead of differentiated HL-60 cells, fresh human polymorphonuclear leukocytes were used. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy adult volunteers by dextran sedimentation and Ficoll-Paque density gradient centrifugation. S. pneumoniae serotype 11A (a reference strain obtained from the WHO Collaborating Center for Reference and Research on Streptococci) was grown in THB supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract and kept frozen (−70°C) in aliquots of THB with 15% glycerol.

Statistical methods.

The antibody concentrations are expressed as geometric-mean concentrations (GMCs). The paired two-sample t test was applied for determination of significance of differences between pre- and postimmunization sera, using log-transformed data.

RESULTS

The specificity of antibodies reacting with the Pnc PS antigens was assessed by three types of experiments. First, the inhibition of antibody binding to Pnc PS antigens by homologous and heterologous PSs was analyzed. In some of the experiments, Pnc PS preparations from different manufacturers were compared. Second, the specificity of the binding of murine MAbs to Pnc PS antigens was examined. Third, the specificity of the antibody response in human pneumococcal vaccine recipients was studied.

Inhibition of anti-PS binding by homologous and heterologous PSs.

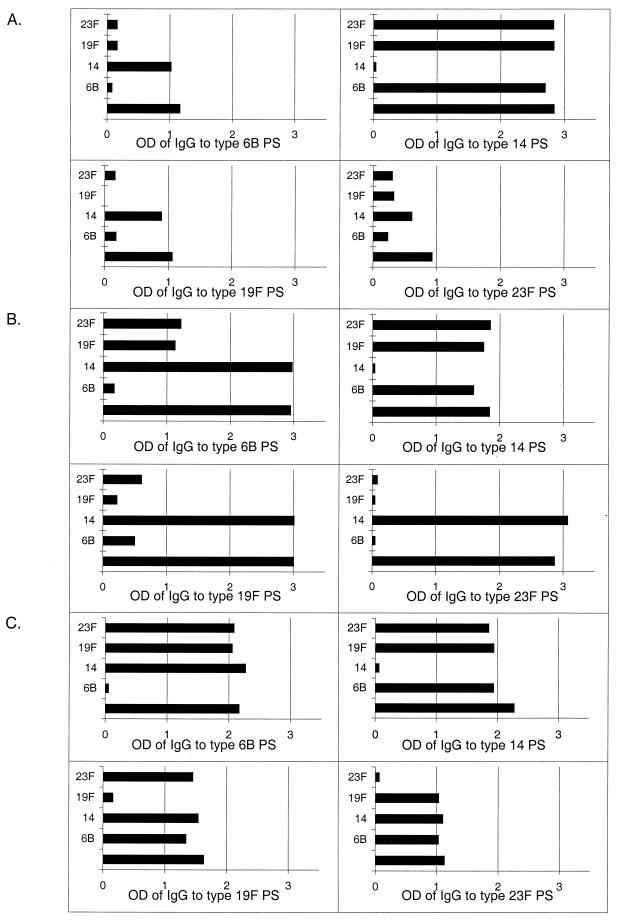

The specificity of antibody binding to Pnc PSs of types 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F was studied by performing inhibition assays with soluble homologous and heterologous PSs. In preliminary experiments, we found that in some adult and infant sera the binding of antibody to type 6B, 19F, or 23F PS was inhibited not only with the homologous PS but also with a heterologous PS of type 6B, 19F, or 23F. In contrast, the binding of antibody to PS of types 6B, 19F, or 23F was not inhibited with type 14 PS; furthermore, antibody binding to type 14 PS was inhibited only with type 14 PS. This implies that the antibodies to PS type 14 were serotype specific. MenA or H. influenzae type b PS did not inhibit antibody binding to type 6B, 14, 19F, or 23F PS (data not shown). Detectable antibody to CPS in the test sera had been inhibited by addition of CPS before performance of the EIA (data not shown). To summarize the preliminary experiments, we found extensive cross-reactivity of antibody binding to type 6B, 19F, and 23F PSs but not to Pnc type 14, MenA, or H. influenzae type b capsular PS, even after exhaustive neutralization with CPS. Such cross-reactivity was seen in sera of nonimmunized adults and infants but not in sera taken after vaccination, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Typical examples of inhibition experiments. (A) Serum from a nonimmunized infant (6 months). (B) Serum from a nonimmunized adult. (C) Serum from an adult after vaccination with the 23-valent PS vaccine. OD values of antibodies to 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F (y axis) measured by EIA are presented after inhibition with CPS and type 6B, 14, 19F, or 23F PS (x axis). A sample inhibited with CPS only (bottom bars) served as a normal signal.

To define the prevalence of the cross-reactive anti-Pnc PS type 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F antibodies in relation to previous exposure to Pnc PS immunization, inhibition EIA was performed with sera from nonimmunized infants and adults, with sera from 7-month-old infants immunized at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with the PncD conjugate vaccine, and with postvaccination sera from adults immunized with either the PncD conjugate vaccine or a 23-valent PS vaccine (Table 2). Addition of the homologous PS to sera prior to EIA caused 92, 94, 91, and 91% (mean [n = 49]) inhibition of antibody binding to 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F, respectively, compared to that for the sample treated with CPS only (data not shown). The antibodies binding to 6B, 19F, and 23F PSs in most of the sera from nonimmunized infants and adults were inhibited (at least a 50% reduction in OD) not only by the homologous PS but also by heterologous PSs of these three types. In contrast, in all cases anti-PS type 14 antibodies were inhibited only by the homologous PS (Table 2). All postimmunization sera from 7-month-old infants immunized at 2, 4, and 6 months of age with the PncD conjugate vaccine contained antibodies that were inhibited by the homologous PS only. Similarly, antibodies in adult postvaccination sera were in most of the cases inhibited only by the homologous PS (Table 2). This is considerably less inhibition than for the adult preimmunization sera. Cross-reactive antibodies observed in adult postimmunization sera were probably not induced by vaccination; a more than twofold increase in the level of specific antibodies was noticed in only 3 of the 11 cases of cross-reactivity.

TABLE 2.

Proportions of sera with cross-reactivity of antibody binding to type 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F PSs

| Sera | Proportion (%) of sera with cross-reactivitya to:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6B | 14 | 19F | 23F | |

| Nonimmunized | ||||

| Adult prevaccination serab | 11/14 (79) | 0/14 (0) | 10/14 (71) | 7/12 (58) |

| Sera from nonimmunized infants (6, 7, 14 mo) | 4/6 (67) | 0/6 (0) | 4/6 (67) | 4/6 (67) |

| Immunized | ||||

| Adult postvaccination serac | 4/17 (24) | 0/17 (0) | 4/17 (24) | 2/17 (12) |

| Sera from immunized infants (7 mo)d | 0/12 (0) | 0/11 (0) | 0/12 (0) | 0/11 (0) |

Cross-reactivity (≥50% reduction in OD) was tested with sera from adults and infants, both nonimmunized and immunized. For the various Pnc PS types, the number of sera used in the inhibition experiments differed, as indicated, because only sera that had enough antibodies to the specified Pnc PS were suitable.

Sera obtained before (day zero) immunization with either PS vaccine or PncD conjugate.

Sera obtained 28 days after immunization with either PS vaccine or PncD conjugate.

Sera obtained from 7-month-old infants who had been immunized with PncD conjugate at 2, 4, and 6 months.

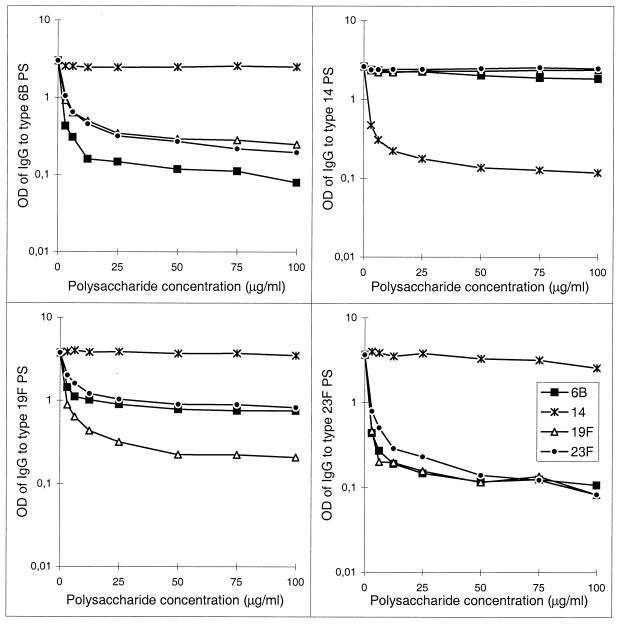

The effect of the PS concentration used in the inhibition EIA on antibody binding was tested for two adult prevaccination serum samples diluted 1:100 and treated with different concentrations of Pnc PSs. The inhibition was dose dependent (Fig. 2). A plateau was reached at a PS concentration ≥30 μg/ml. Thus, the concentration of 30 μg/ml used in the inhibition EIA was the concentration that completely inhibited antibody binding. The concentrations of heterologous PSs needed for inhibition were somewhat higher than the concentration of the homologous PS. This was most notable in the 6B and 19F EIAs (Fig. 2). The difference in the levels of bound antibody after inhibition with heterologous and with homologous PSs probably represents the amount of specific antibody.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of IgG antibody binding to type 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F PSs as a function of the 6B, 14, 19F, or 23F PS concentration used for inhibition. As an example, results of an experiment done with a 100-fold-diluted serum sample from a nonimmunized adult are shown.

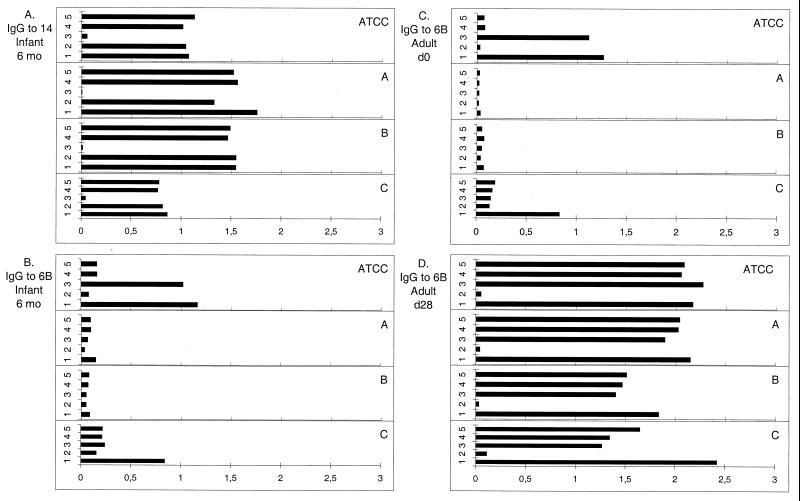

Comparison of different PS preparations.

The capsular PS preparations from different manufacturers are purified differently. To investigate whether this affects the nature of the Pnc PS preparations and the results, the specificities of preparations of type 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F PSs from four different manufacturers (ATCC, A, B, and C) were compared by inhibition EIA (examples are shown in Fig. 3). The inhibition was tested using PSs from the same manufacturer for both inhibition and coating. Inhibition EIA was done with sera from nonimmunized infants (n = 4), sera collected at 7 months postvaccination from infants given the PncD conjugate (n = 7), and pre- and postvaccination sera from adults vaccinated with the PS vaccine (n = 8) or with the PncD conjugate (n = 8). Binding to PS of type 14 was serotype specific regardless of the PS source (Fig. 3A), except for one preparation (data not shown). For serotypes 19F and 23F, no PS preparation-specific differences in specificity were observed (data not shown). However, we found remarkable differences between PS 6B preparations. Four sera from nonimmunized infants were tested; three had previously been found to contain cross-reactive antibodies, i.e., antibodies binding to ATCC 6B PS that could be inhibited by heterologous PS, and one had been serotype specific. The three sera showed no or very-low-level antibody binding to PS 6B from manufacturers A and B but high-level antibody binding to PS 6B from manufacturer C and the ATCC (Fig. 3B). In the case in which the antibody binding was serotype specific, the anti-6B binding levels were similar regardless of the PS source (ATCC or manufacturer A, B, or C). Similarly, most of the sera from nonimmunized adults that had been found to contain cross-reactive antibodies to ATCC 6B also contained serotype-specific antibody to the 6B preparation from manufacturer A (Fig. 3C). Accordingly, the proportions of adult preimmunization sera containing cross-reactive antibodies to PS 6B from the ATCC or manufacturer A were 11 of 14 and 1 of 14, respectively. The antibody binding to 6B PS from manufacturer B was not as specific for adult preimmunization sera as it had been for sera from nonimmunized infants. For postimmunization sera of both infants and adults, antibody binding was specific for PS 6B preparations from all the four manufacturers (Fig. 3D).

FIG. 3.

Amount of antibodies binding to PS preparations from different manufacturers (ATCC, A, B, and C). Inhibition experiments were done with serum from an unimmunized infant and antibodies to type 14 PS (A), serum from a nonimmunized infant and antibodies to type 6B PS (B), serum from a nonimmunized adult and antibodies to type 6B PS (C), or serum from a vaccinated adult and antibodies to PS type 6B (D). OD values of antibodies (y axis) were obtained after addition of CPS and type 6B, 14, 19F, or 23F PS from the corresponding manufacturer (x axis). The inhibitor was CPS only (bar 1), 6B (bar 2), 14 (bar 3), 19F (bar 4), or 23F (bar 5).

Specificity of IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies to Pnc PS.

To investigate the IgG subclass composition of the cross-reactive antibody, inhibition EIAs were performed with seven adult preimmunization sera. IgG1 and IgG2 antibody binding to type 6B, 11A, 14, 19F, and 23F PSs was studied after inhibition with homologous and heterologous PSs. Antibody to Pnc PSs is predominantly of the IgG2 subclass, even after conjugate vaccination (26), and thus the majority of the cross-reactive antibody was IgG2 (data not shown). However, in sera that also had IgG1, cross-reactive antibody in both the IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses was found, although for a few sera the cross-reactivity was specifically attributable to the IgG2 subclass (data not shown).

Type specificity of MAbs.

We used MAbs to study whether there was a cross-reactive epitope in the structures of different types of Pnc PS. The specificity of MAbs obtained by immunization of mice with monovalent type 6B or type 14 PS-tetanus toxoid conjugates was tested by EIA using CPS and Pnc PSs of serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 8, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, and 23F. Data for serotypes to which reactivity was found are shown in Table 3. Two MAbs (both of high affinity) specific for serotype 14 recognized only the homologous PS in the EIA. This is in accordance with our findings for human antibodies and implies that type 14 PS is specific. Clones 10H8 and 14A2, specific for PS type 6B, did not recognize type 6A PS. Clone 10H8 (of high affinity), specific for 6B, recognized not only 6B but also 11A, 19F, and 23F coated on the wells of microtiter plates. Clone 14A2 (of low affinity), specific for 6B, also recognized 11A, though the level of binding was very low. This was surprising since the epitope specificities of MAbs 10H8 and 14A2 had been mapped with chemically synthesized fragments representing partial structures of the repeating unit of 6B PS and had been shown to contain the 6B, but not the 6A, epitope. Two lots of 11A PS were tested as described below. Interestingly, the epitope for the 6B-specific MAbs 10H8 and 14A2 was not present in lot 963596 of type 11A PS. The specificity of MAbs to 6B (10H8) and 14 (1F6) was also monitored by colony blotting using bacteria of serotypes 6A, 6B, 11A, 14, 19F, and 23F; in each case, only the specific serotype was recognized. To summarize the specificity of the MAbs, we found that MAbs to type 6B PS cross-reacted with also other than the specific PS type in the EIA, but not on intact bacteria.

TABLE 3.

Titers of MAbs to Pnc PS of types 6B and 14 measured by EIA

| Titer of MAbs to Pnc typea:

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pnc PS in EIA | 6B

|

14

|

||

| Clone 10H8 | Clone 14A2 | Clone 1F6 | Clone 1F2 | |

| 4 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 6A | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 6B | 106,098 | 85,806 | <100 | <100 |

| 9V | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 11A | ||||

| Lot 79268 | 9,818 | 395 | <100 | <100 |

| Lot 963596 | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 14 | <100 | <100 | 43,335 | 66,423 |

| 18C | <100 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 19F | 89,183 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

| 23F | 28,536 | <100 | <100 | <100 |

MAbs were made by immunization of mice with conjugates of tetanus toxoid and Pnc PS of either type 6B or type 14. The lowest dilution used was 1:100.

Specificity of the antibody response to vaccination as measured by EIA.

Because the MAb to 6B PS, produced by immunizing mice with a monovalent 6B PS conjugate, was found to bind 11A PS, a further objective was to assess whether human immunization with Pnc PS also induces antibody binding to heterologous types of PS. Accordingly, a heterologous antibody response to type 11A PS, as well as to types 4, 7F, 9V, and 18C, could be determined easily because these types were not included in the 4-valent conjugate vaccines studied in our laboratory (1). As expected, infants (n = 11) boosted with the 23-valent PS vaccine (which included 11A PS) showed significantly (P < 0.001) higher GMCs of 11A (Table 4), 4, 7F, 9V, and 18C (data not shown) in postimmunization sera than in preimmunization sera. However, infants boosted with the PncD conjugate (n = 12), which contained PSs of types 6B, 14, 19F, and 23F, also showed a significantly higher postimmunization than preimmunization GMC of anti-11A PS (P < 0.01) (Table 4) but not of anti-4, -7F, -9V, or -18C PS (data not shown). In both groups the antibody response to the vaccine types was good, as shown previously (1). A significant response to 11A PS was also observed after vaccination of adults (n = 10) with a PncD/T conjugate that did not contain type 11A PS (P < 0.05). For control, data from adults vaccinated with a 23-valent PS vaccine and from adults who had not received any pneumococcal vaccination are shown in Table 4. However, when the antibody assays were repeated using a different lot of 11A PS for coating (lot 963596), no increase in the GMC of anti-11A PS in sera of infants boosted with the 4-valent conjugate vaccine was measured (Table 4). For the other vaccine groups, no such differences between the two lots were observed, although we found differences for some individual sera (data not shown). Furthermore, the concentrations tended to be lower, though not significantly, when lot 963596 of 11A PS was used (Table 4). The specificity of 11A antibodies in sera collected at 15 months postvaccination from infants boosted with either PncD or PncPS and in pre- and postvaccination sera of adults vaccinated with the PS conjugate was further analyzed by inhibition EIA using lot 963596 of 11A PS. Antibodies to 11A PS induced by vaccination with the PS vaccine containing the 11A PS were type specific, whereas in cases in which an increase in 11A antibody was seen after vaccination with the heterologous PSs, the antibodies to 11A were cross-reactive with PS of types 6B, 19F, and 23F, but not with PS of type 14 (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Type 11A antibody concentrations in infants before and after boosting with either PncD conjugate vaccine or PS vaccine and in adults before and 1 month after vaccination with PncD/T conjugate or PS vaccine

| Lot no. of PS 11A used in EIA | Vaccinees and vaccine | 11A PS in vaccine | n | GMC of 11A antibody, μg/ml (95% confidence intervals)

|

No. (%) with >2-fold increase in GMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prea | Postb | |||||

| 79268 | Infants | |||||

| PncD | No | 12 | 0.28 (0.16–0.50) | 2.79c (0.96–8.12) | 8 (73) | |

| PS | Yes | 11 | 0.24 (0.18–0.33) | 1.26d (0.60–2.67) | 8 (73) | |

| Adults | ||||||

| PncD/T | No | 10 | 1.32 (0.72–2.41) | 2.38e (1.13–5.03) | 2 (20) | |

| Controlf | No | 12 | 2.69 (1.89–3.82) | 2.67 (1.82–3.90) | 0 (0) | |

| PS | Yes | 10 | 1.38 (0.73–2.61) | 3.82c (1.65–8.87) | 7 (70) | |

| 963596 | Infants | |||||

| PncD | No | 12 | 0.13 (0.06–0.30) | 0.15 (0.07–0.33) | 1 (8) | |

| PS | Yes | 11 | 0.09 (0.06–0.16) | 0.84d (0.37–1.89) | 9 (90) | |

| Adults | ||||||

| PncD/T | No | 10 | 0.88 (0.45–1.71) | 1.45e (0.69–3.07) | 2 (20) | |

| Controlf | No | 12 | 4.20 (2.91–6.07) | 4.02 (2.62–6.17) | 0 (0) | |

| PS | Yes | 10 | 1.18 (0.52–2.69) | 3.03c (1.05–8.70) | 8 (80) | |

For infants, preboost samples were obtained at 14 months; for adults, prevaccination samples were obtained on day zero.

For infants, postboost samples were obtained at 15 months; for adults, postvaccination samples were obtained on day 28.

Difference in GMCs of IgG before and after vaccination or boost is significant (P < 0.01, paired two-sample t test).

Difference in GMCs of IgG before and after vaccination or boost is significant (P < 0.001, paired two-sample t test).

Difference in GMCs of IgG before and after vaccination or boost is significant (P < 0.05, paired two-sample t test).

Control group members (n = 12) had not received any pneumococcal vaccinations.

To evaluate the functional activity of the 11A antibodies induced by heterologous PSs, their capacity to opsonize type 11A pneumococci was determined. Sera from four infants boosted with PncD (11A not included) were used. Despite having high concentrations of antibody to 11A PS lot 79268 (the concentration of antibody to 11A was equal to that of the control sera), the sera had no detectable opsonic activity against 11A (data not shown). As a control, we examined six sera from adults or infants (at 15 months) vaccinated with the 23-valent PS vaccine (which included 11A). Five of six sera showed high opsonic activity against 11A.

DISCUSSION

In the present article we describe naturally acquired pneumococcal antibodies that can bind to capsular PS preparations from many types of S. pneumoniae in an EIA. We found that the binding of antibody to Pnc PS in the EIA was inhibited not only by the homologous PS but also by heterologous PSs. Cross-reactivity was highly prevalent in sera of both nonvaccinated adults and infants. In contrast, except for 3 (of 17) cases, cross-reactive antibody was not detected in sera of subjects who had antibody responses to vaccination with either Pnc PS or a conjugate pneumococcal vaccine. However, a significant antibody response to type 11A PS was detected even in sera of both adults and infants who had not received vaccines containing 11A PS. These antibodies to 11A PS induced by heterologous PS were not specific, and their binding was inhibited by several heterologous PSs. These data suggest that even postimmunization responses measured by EIA can in rare cases involve nonspecific-antibody production. An unexpected finding was that MAbs evoked by vaccination with the 6B PS-tetanus toxoid conjugate bound other types of PS as well in EIAs.

Although a high concentration of antibody to 11A was measured by EIA, we found that these antibodies did not opsonize type 11A pneumococci. Accordingly, there have been several reports of sera with lower levels of opsonophagocytic activity than had been presumed on the basis of the antibody concentration (4, 19, 25, 31). Furthermore, there was remarkable variation between two lots of 11A PS; in some of the sera, the nonopsonic, heterologously induced antibodies that were measured by EIA using one lot could not be measured using another lot. Even though the specificity of lot 963596 seemed to be higher, antibody to this lot in sera of some individuals was still inhibited by heterologous PSs. It was also noteworthy that two PS 6B preparations showed remarkably less cross-reactive antibody binding than two others. The results suggest that in some sera there were ineffective antibodies directed against epitopes or impurities common to different PS types and that the epitopes were not present in all PS preparations. This suggests that the epitopes are not PS specific. In addition, pneumococcal vaccines may stimulate the production of antibodies to these epitopes. As an exception, we found antibodies against type 14 PS to be clearly specific, as described also by Yu et al. (31). This is in agreement with a study reporting that the levels of antibody to type 14 PS in nonvaccinated individuals do not correlate with levels of antibody to other types of PS and thus may not be cross-reactive (4).

Several explanations for the results can be speculated. First, the data on the MAbs suggest the possibility of cross-reactive epitopes for several Pnc PSs. Second, the PS preparations used in the current EIA contain impurities, other than CPS, that are cross-reactive among several types of Pnc PS, as suggested by Yu et al. (31). These cross-reactive epitopes or impurities may not be present in all lots of PS or in preparations purified differently.

A variety of PSs are composed of structurally similar monosaccharides which mediate immunogenicity (29). It is possible that the observed cross-reactivity is a result of a common epitope among the serotypes, since cross-reactive structures among pneumococcal PSs belonging to different serogroups have actually been described (7). In addition, antigenic specificities can also be conferred by conformational epitopes (30). Thus, a possible explanation for the cross-reactivity described here is that a conformational epitope is present in many PSs of different backbones. Pneumococcal 6B and 6A PSs are linear isopolymers with similar structures, differing only in the rhamnose-ribitol bond [α(1→4) for 6B and α(1→3) for 6A]. We found that the MAbs specific for 6B did not bind 6A. Thus, the conformation may be important. The epitope specificity of the MAbs to 6B was due to the disaccharide rhamnose-(1-4)-ribitol phosphate, which makes it 6B specific (W. Jansen, personal communication). However, the MAbs also recognized types other than the specific PS type in the EIA. The fact that lot 963596 of 11A PS did not contain the epitope for the MAbs supports the theory that there was a contaminant in the PS preparations. Furthermore, the epitope for the MAbs may have appeared in the PS only when it was attached to a plastic surface and not on the surface of intact bacteria, since cross-reactivity was not detected by colony blotting.

It has been well established that Pnc PSs contain CPS as a contaminant, and antibodies to CPS should be preadsorbed prior to detection of type-specific responses (6, 12, 17, 27). Because both CPS and capsular PS are covalently attached to peptidoglycan (28), it is possible that impurities other than CPS are present in PS preparations. Studies have shown that some of the cross-reactivity can be associated with low levels of contaminating protein present in various amounts in different Pnc PS preparations (G. van den Dobbelsteen, unpublished data). However, the antibodies to Pnc PS were predominantly of the IgG2 subclass in adults. This implies that the cross-reactive antibodies were directed against PS determinants, since antibodies to PSs are mostly IgG2 (26). Interestingly, pneumococcal conjugate vaccines may stimulate the production of antibodies to these impurities. This might be a rare event, since the only heterologous antibody response detected was to type 11A PS. Consequently, it will not be possible to measure type-specific antibody responses until pure, well-defined PS preparations become available. One possible means of decreasing the cross-reactivity is to include an irrelevant Pnc PS inhibition as one extra step in the EIA (C. Frasch, personal communication). The problem is that we do not know the quality of the cross-reaction. Thus, the amount and quality of the contaminant cannot be monitored, and as observed in this study, alternative PS preparations may contain different contaminants. The adequacy of each new lot or source of PS used should thus be determined separately.

Antibody cross-reactive with type 6B, 19F, and 23F PSs was found more often in sera of nonimmunized subjects than in those of vaccinees. This speaks for a different antigenic stimulus of naturally induced antibody than vaccine-induced antibody. Naturally induced antibodies to pneumococcal PSs are developed by exposure to pneumococci or other bacteria with cross-antigenic structures. Vaccination results in manifold increases in the antibody level compared to the prevaccination level. The concentration of cross-reactive antibody present in preimmunization sera is proportionally so small in postimmunization sera that it is insignificant. Thus, the lack of cross-reactivity evident with postvaccination sera could also be due to a failure to detect it, probably because of a lower concentration or a lower avidity of cross-reactive antibody than of vaccine-induced antibody.

In conclusion, the data from these studies show that a substantial proportion of antibody to pneumococcal PSs measured by EIA is reactive also with PSs other than the type-specific one. Antibodies polyreactive with Pnc PSs have also been reported by others (4, 31; M. H. Nahm, Abstr. Symp. Pneumococci Pneumococcal Dis., p. 59, 1998). The fact that in most cases cross-reactive antibodies were found in sera of nonimmunized subjects should be taken into consideration in subsequent studies measuring naturally induced antibodies to Pnc PS. Moreover, immunogenicity of vaccination is often evaluated by fold increases in the antibody level compared to the prevaccination level. Thus, it is important to understand the specificity of antibodies in preimmunization sera. The development with age, the exact nature of the cross-reactive epitopes, and the biological significance of these cross-reactive antibodies remain to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by WHO grant V23/181/116.

We thank Sirkka-Liisa Wahlman and Nina Lindholm for technical assistance, Merja Anttila for performing opsonophagocytosis assays, and Tea Nieminen, Tomi Wuorimaa, and Anu Kantele for serum samples. P. Helena Mäkelä is appreciated for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Åhman H, Käyhty H, Lehtonen H, Leroy O, Froeschle J, Eskola J. Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide-diphtheria toxoid conjugate vaccine is immunogenic in early infancy and able to induce immunologic memory. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17:211–216. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199803000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anttila M, Eskola J, Åhman H, Käyhty H. Avidity of IgG for Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B and 23F polysaccharides in infants primed with pneumococcal conjugates and boosted with polysaccharide or conjugate vaccines. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:1614–1621. doi: 10.1086/515298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anttila M, Voutilainen M, Jäntti V, Eskola J, Käyhty H. Contribution of serotype-specific IgG concentration, IgG subclasses and relative antibody avidity to opsonophagocytic activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:402–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coughlin R T, White A C, Anderson C A, Carlone G M, Klein D L, Treanor J. Characterization of pneumococcal specific antibodies in healthy unvaccinated adults. Vaccine. 1998;16:1761–1767. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00139-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Weers O, Beurret M, van Buren L, Oomen L A, Poolman J T, Hoogerhout P. Application of cystamine and N,N′-bis(glycyl)cystamine as linkers in polysaccharide-protein conjugation. Bioconjug Chem. 1998;9:309–315. doi: 10.1021/bc9702011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldblatt D, Jadresic L P, Levinsky R J, Turner M W. Antibody responses to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide: what is being measured? Immunodeficiency. 1993;4:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heidelberger M. Precipitating cross-reactions among pneumococcal types. Infect Immun. 1983;41:1234–1244. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.3.1234-1244.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrichsen J. Six newly recognized types of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2759–2762. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2759-2762.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kauffman F, Lund E, Eddy B E. Proposal for a change in the nomenclature of Diplococcus pneumoniae and a comparison of the Danish and American type designations. Int Bull Bacteriol Nomencl Taxon. 1960;10:31–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Käyhty H, Åhman H, Rönnberg P-R, Tiilikainen R, Eskola J. Pneumococcal polysaccharide-meningococcal outer membrane protein complex conjugate vaccine is immunogenic in infants and children. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1273–1278. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.5.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Käyhty H, Eskola J, Peltola H, Rönnberg P-R, Kela E, Karanko V, Saarinen L. Antibody responses to four Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. Am J Dis Child. 1991;145:223–227. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1991.02160020117030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koskela M. Serum antibodies to pneumococcal C polysaccharide in children: response to acute pneumococcal otitis media or to vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1987;6:519–526. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198706000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee C-J, Koizumi K, Henrichsen J, Perch B, Lin C S, Egan W. Capsular polysaccharides of nongroupable streptococci that cross-react with pneumococcal group 19. J Immunol. 1984;133:2706–2711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lund E, Henrichsen J. Laboratory diagnosis, serology and epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Methods Microbiol. 1978;12:241–262. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran E E, Brandt B L, Zollinger W D. Expression of the L8 lipopolysaccharide determinant increases the sensitivity of Neisseria meningitidis to serum bactericidal activity. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5290–5295. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5290-5295.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musher D M, Watson D A, Baughn R E. Does naturally acquired IgG antibody to cell wall polysaccharide protect human subjects against pneumococcal infection? J Infect Dis. 1990;161:736–740. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musher D M, Luchi M J, Watson D A, Hamilton R, Baughn R E. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in young adults and older bronchitics: determination of IgG responses by ELISA and the effect of adsorption of serum with non-type-specific cell wall polysaccharide. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:728–735. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musher D M, Groover J E, Rowland J M, Watson D A, Struewing J B, Baughn R E, Mufson M A. Antibody to capsular polysaccharides of Streptococcus pneumoniae: prevalence, persistence, and response to revaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:66–73. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahm M H, Olander J V, Magyarlaki M. Identification of cross-reactive antibodies with low opsonophagocytic activity for Streptococcus pneumoniae. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:698–703. doi: 10.1086/514093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieminen T, Eskola J, Käyhty H. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in adults: circulating antibody secreting cell response and humoral antibody responses in saliva and in serum. Vaccine. 1998;16:630–636. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00235-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quataert S A, Kirch C S, Quackenbush Wiedl L J, Phipps D C, Strohmeyer S, Cimino C O, Skuse J, Madore D V. Assignment of weight-based antibody units to a human antipneumococcal standard reference serum, lot 89-S. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1995;2:590–597. doi: 10.1128/cdli.2.5.590-597.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robbins J B, Lee C-J, Rastogi S C, Schiffman G, Henrichsen J. Comparative immunogenicity of group 6 pneumococcal type 6A(6) and type 6B(26) capsular polysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1979;26:1116–1122. doi: 10.1128/iai.26.3.1116-1122.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Glode M P, Vann W, Schiffer M S, Liu T-Y, Parke J C, Huntley C. Cross-reactive antigens and immunity to diseases caused by encapsulated bacteria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1975;56:141–151. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(75)90119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodriguez M E, van den Dobbelsteen G P J M, Oomen L A, de Weers O, van Buren L, Beurret M, Poolman J T, Hoogerhout P. Immunogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 6B and 14 polysaccharide-tetanus toxoid conjugates and the effect of uncoupled polysaccharide on the antigen-specific immune response. Vaccine. 1998;16:1941–1949. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romero-Steiner S, Libutti D, Pais L B, Dykes J, Anderson P, Whitin J C, Keyserling H L, Carlone G M. Standardization of an opsonophagocytic assay for the measurement of functional antibody activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae using differentiated HL-60 cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:415–422. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.4.415-422.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soininen A, Seppälä I, Nieminen T, Eskola J, Käyhty H. IgG subclass distribution of antibodies after vaccination of adults with pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. Vaccine. 1999;17:1889–1897. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sørensen U B S, Henrichsen J. C-polysaccharide in a pneumococcal vaccine. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand Sect C. 1984;92:351–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1984.tb00099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sørensen U B S, Henrichsen J, Chen H-C, Szu S C. Covalent linkage between the capsular polysaccharide and the cell wall peptidoglycan of Streptococcus pneumoniae revealed by immunochemical methods. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:325–334. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Dam J E G, Fleer A, Snippe H. Immunogenicity and immunochemistry of Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1990;58:1–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02388078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wessels M R, Kasper D L. Antibody recognition of the type 14 pneumococcal capsule. Evidence for a conformational epitope in a neutral polysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1989;169:2121–2131. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu X, Sun Y, Frasch C, Concepcion N, Nahm M H. Pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide preparations may contain non-C-polysaccharide contaminants that are immunogenic. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:519–524. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.4.519-524.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]