Abstract

A commercial latex agglutination assay (LA) and a sandwich enzyme immunoassay (SEIA) (Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) were compared with a competitive binding inhibition assay (enzyme immunoassay [EIA]) to determine the potential uses and limitations of these antigen detection tests for the sensitive, specific, and rapid diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis (IA). Toward this end, well-characterized serum and urine specimens were obtained by using a rabbit model of IA. Serially collected serum or urine specimens were obtained daily from control rabbits or from rabbits immunosuppressed and infected systemically with Aspergillus fumigatus. By 4 days after infection, EIA, LA, and SEIA detected antigen in the sera of 93, 93, and 100% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits, respectively, whereas antigen was detected in the urine of 93, 100, and 100% of the rabbits, respectively. False-positive results for non-A. fumigatus-infected rabbits for EIA, LA, and SEIA were as follows: for serum, 14, 11, and 23%, respectively; for urine, 14, 84, and 90%, respectively. Therefore, although the sensitivities of all three tests were similar, the specificity was generally greater for EIA than for LA or SEIA. Infection was also detected earlier by EIA, by which the serum of 53% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits was positive as early as 1 day after infection, whereas the serum of only 27% of the rabbits tested by LA was positive. Although the serum of 92% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits was positive by SEIA as early as 1 day after infection, the serum of a high percentage (50%) was false positive before infection. The urine of 21% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits was positive by EIA as early as 1 day after infection, and the urine of none of the rabbits was false positive before infection. When EIA results for urine specimens were combined with those for serum, sensitivity was improved (i.e., 67% of rabbits were positive by 1 day after infection and only one rabbit gave a false-positive result). A total of 93% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits were positive for antigen in urine as early as 1 day after infection and the urine of 100% of the rabbits was positive by SEIA. However, before infection, 79% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits were false positive for antigen in urine by LA and 90% were false positive for antigen in urine by SEIA. These data indicate that the EIA has the potential to be used to diagnose IA with both serum and urine specimens and to detect a greater number of infections earlier with greater specificity than the specificities achieved with the commercial tests.

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is a common infectious complication of the immunocompromised host, with high rates of morbidity and mortality (23, 42). IA has been reported to develop in 70% of patients who are granulocytopenic for 34 or more days, and overall mortality ranges from 40 to 100% in this patient population (8, 9, 28, 30, 41). The incidence of IA has risen significantly in recent years because of the increased number of bone marrow and organ transplantations being performed and the concomitant aggressive immunosuppressive regimens being used (6, 20, 25, 28).

An earlier diagnosis of IA has been reported to result in a better patient prognosis because appropriate antifungal therapy can be instituted more rapidly (7, 9, 27, 35, 40). However, early diagnosis of IA can be difficult because of the absence of specific symptoms and because blood cultures are seldom positive even when specialized culturing techniques are used (6, 36). Detection of antibody can be unreliable because anti-Aspergillus species antibodies can be present in healthy individuals and patients most at risk for IA are often deliberately immunosuppressed to prevent rejection of transplanted organs or bone marrow (2, 6, 16, 20, 39). To complicate matters, most antigen detection tests have fallen short of the desired sensitivity or lack specificity (3, 6, 33, 34, 36). The most promising of these tests detect a cell wall-derived polysaccharide antigen of Aspergillus species, galactomannan (GM), in patient serum or urine as an indicator of disease (3, 21, 24, 26). All of these tests, however, were produced in-house so that no standardized test has been available for general clinical use.

Recently, a commercial latex agglutination test (LA; Pastorex Aspergillus; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) and a double-antibody sandwich enzyme immunoassay (SEIA; Pastorex PLATELIA Aspergillus; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur) were developed by using a rat monoclonal antibody to detect the galactofuranose moieties of GM (31, 32, 37, 38). The overall sensitivities of these tests for detection of GM in serum has been reported to range from 28 to 100% for LA and from 83 to 100% for SEIA (15, 18, 22, 38). The specificities for detection of GM in serum have been reported to vary from 16 to 100% for LA and 71 to 89% for SEIA (15, 18, 22, 33, 37, 38). The reasons for this variability in reported sensitivities and specificities appear to be variations in the patient populations examined, the test conditions used, and/or the immunosuppressive regimens used (20, 33). Differences in the sensitivities and specificities of the Pastorex kits may also be due to variations in the length of time that the specimens were stored or the temperature at which the specimens were stored (37). In addition, reports of studies with these kits as well as other noncommercial tests indicate variability in the utilities of these tests for detection of GM in urine versus serum (4, 14, 31). The sensitive and specific detection of GM in urine rather than serum would provide at least two advantages: (i) samples could be obtained more frequently in a noninvasive manner, and (ii) larger sample volumes could be collected and concentrated to potentially increase test sensitivity.

We compared the commercial LA and SEIA with a competitive binding inhibition enzyme immunoassay (EIA) developed in our laboratory for their capacities to detect GM in serum and urine from a panel of well-characterized, uniformly immunocompromised, Aspergillus fumigatus-infected rabbits and their controls in order to evaluate the potential uses and limitations of these tests. This study focused on (i) the kinetics of antigenemia and antigenuria detection by these tests, (ii) a comparison of the utility of GM detection in serum to the utility of GM detection in urine, and (iii) the potential of each test format to provide an earlier and more specific diagnosis of IA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms.

A. fumigatus strain B2570, obtained as lyophilized stock cultures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Mycology Reference Laboratory, was used for rabbit infection studies, for the production of the GM preparations used to coat microtitration plates, and for the production of the antigen used to construct standard curves for the competitive binding inhibition EIA. Control rabbits were infected with one of the following: Candida albicans strain B36, Lecocq, or Q16 (B serotypes) or 3181A, 2730, or B311 (A serotypes), Candida tropicalis 83-48062, Candida parapsilosis B390, Candida krusei 83-056058, Candida glabrata WO755, or Cryptococcus neoformans 9759. All fungi were obtained from the CDC Mycology Reference Laboratory. Other control rabbits were infected with Staphylococcus aureus (a clinical isolate obtained as a gift from Gary Hancock, Hospital Infections Program, CDC) or Escherichia coli (a clinical isolate obtained as a gift from Nancy Strockbine, Division of Bacterial and Mycotic Diseases, CDC). Fungi were grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) slants (Emmon's modification; BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) at 25°C for 48 h (yeasts) or at 35°C for 4 days (A. fumigatus). S. aureus and E. coli were grown for 24 h at 37°C on Trypticase soy agar containing 5% sheep blood (BBL).

Growth of A. fumigatus for production of GM-containing antigen.

A. fumigatus conidia were harvested from the surfaces of SDA slants after 6 days of growth at 37°C by washing with 5 ml of sterile 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 8.1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.9 mM KH2PO4, 0.85% NaCl [pH 7.2]) containing 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). The number of conidia in the resultant wash fluid was determined by using a hemocytometer. Then, 106 conidia were used to seed each 1-liter Erlenmeyer flask containing 300 ml of Czapek-Dox medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 10−6 M CuSO4, 10−4 M CaCl2, and 10−5 M each MnCl2, FeSO4, and ZnSO4. Cultures were grown at 37°C for 48 h with agitation (100 rpm) in a rotary incubator (PsychroTherm; New Brunswick Scientific, New Brunswick, N.J.). Mycelial mats were harvested by vacuum filtration of the suspension through sterile cheesecloth placed in a Büchner funnel, followed by washing with 3 volumes of sterile PBS.

Preparation of GM-containing antigen for generation of standard curves and coating of microtitration plates.

Washed mycelial mats (total wet weight, 109.32 g) were suspended in 2 liters of 0.02 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.0) in a 4-liter Erlenmeyer flask, and the mixture was autoclaved at 121°C for 45 min. After being cooled to ambient temperature, the autoclaved material was centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min, and the resultant pellet was resuspended in the same buffer to a volume of 1 liter and placed in a Waring blender (Waring, Inc., Waring, Pa.). The suspension was blended for 5 min at a speed setting of 5 and was then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min. The resultant pellet was resuspended in 600 ml of freshly prepared and deaerated 0.4 N NaOH containing 0.01 M NaBH4 and was transferred to a 1-liter polypropylene bottle (Nalgene Labware Div., Nalge/Sybron Corp., Rochester, N.Y.). The sample was purged with N2, stirred on ice for 22 h, and then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was removed, adjusted to pH 6.5 with glacial acetic acid, and kept overnight at 4°C.

On the following day, the mixture was centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 20 min to remove the thick precipitate formed upon neutralization. The supernatant was adjusted to pH 7.0 with 1 N NaOH and was centrifuged again, but at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was then concentrated in an ultrafiltration cell (TCF 10; Amicon Corp., Beverly, Mass.) under positive N2 pressure in the cold (4°C) by using a PM10 membrane (molecular weight cutoff, 10,000; Amicon). The concentrated retentate (125 ml) was dialyzed for 24 h against five, 2-liter changes of deionized water. The sample was then centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min and the supernatant, which contained GM, either was column fractionated as described below or was frozen in an acetone-dry ice bath. Dry GM was recovered after lyophilization of the frozen supernatant.

Column chromatographic fractionation of Aspergillus GM-containing antigen.

The GM-containing supernatant described in the previous section was fractionated by column chromatography, and the compositions of the column fractions were analyzed. A column (1.6 by 50 cm) of Superose 6 preparative grade resin (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) was equilibrated with 0.01 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) that contained 0.1 M NaCl. Two milliliters of the GM-containing preparation was loaded onto the column and was eluted with equilibration buffer at 0.25 ml/min. Two-milliliter fractions were collected, and the UV absorbance at 280 nm was recorded. Fractions of the GM-containing preparation were assayed for total carbohydrate by the phenol-sulfuric acid method (10) and for total protein by the assay described by Bradford (5).

Preparation of cell walls for immunization of rabbits.

Mycelial mats were washed once by centrifugation in cold 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) at 8,000 × g for 20 min. The cells were resuspended in 2 volumes of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.0) and were disrupted for 3 min at high speed in a Braun MSK homogenizer (Bronwill Scientific Co., Rochester, N.Y.) containing 20 ml of 0.5-mm glass beads (Bio Spec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). During homogenization, the Braun homogenizer was cooled to less than 10°C by liquid CO2 injected around the base of the homogenizer flask. The cell walls and the remaining unbroken cells were then decanted from the glass beads. The residual glass beads were washed twice with a total of 25 ml of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 7.0), and the washes were pooled with the liquid phase. The pooled mixture was then centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min, and the pellet was washed three times by centrifugation with 1 volume of 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) that contained 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) and was resuspended in cold 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5; 1:1 [vol/vol] ratio of buffer to cell walls). The suspension was then homogenized once again in the Braun homogenizer by using two 30-s homogenization cycles and two 30-s cooling intervals. Observation of the resultant mixture by phase-contrast microscopy (magnification, ×1000) confirmed that greater than 98% of the cells were disrupted by this method. The cell wall suspension was then decanted, and the remaining glass beads were washed twice with 0.1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and 10% sucrose (TTS buffer). The combined cell wall suspension and washes were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 30 min, and the resultant pellet was washed three times by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min with TTS buffer. The pellet was resuspended in 1 volume of TTS buffer, and the suspension was gently stirred overnight at 100 rpm and 4°C.

The suspension was then transferred to 50-ml polycarbonate tubes (Oak Ridge tubes; Nalgene), and the tubes were centrifuged at 5,500 × g for 30 min. The less homogeneous layers of material at the tops and bottoms of the tubes were discarded, and the more homogeneous, central layer of cell walls was removed and washed three times by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 30 min in 1 volume of TTS buffer. The pelleted cell walls were then washed three times by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 20 min in 1 volume of 0.14 M NaCl (1:1 [vol/vol] ratio of pellet to buffer) and then six times in 1 volume of distilled H2O. The pellet was resuspended in 20 ml of distilled H2O to form a thin slurry, frozen in an acetone-dry ice bath, and lyophilized.

Polyclonal antibody production.

Female New Zealand White rabbits (weight, 2 to 3 kg) were immunized with A. fumigatus cell walls, prepared by suspending 5 mg of lyophilized cell walls in 5 ml of 0.85% sterile saline and then adding 2 ml of this suspension to one vial of Ribi adjuvant (Ribi Immunochemicals, Hamilton, Mont.). The vial was shaken vigorously to form a cell wall-adjuvant emulsion. The rabbits were initially injected once in the following sites on day 0: 0.2 ml intramuscularly in each hind leg, 0.1 ml subcutaneously at the neck, 0.3 ml intradermally at six sites along the back, and 0.2 ml intraperitoneally. One week later, 750 μg of cell walls suspended in 0.1 ml of physiological saline was administered intravenously, and this was repeated at weekly intervals for 6 weeks. Serum was obtained beginning on day 18 after immunization and was collected at biweekly intervals. Serum samples were tested by an indirect EIA, and those with titers of greater than 512,000 were pooled for use as labeled antibody.

Antibody purification and labeling.

Polyclonal antibody was purified and labeled by the method of Wilson and Nakane (43) as modified by Gray (12). Briefly, antibodies were precipitated with ammonium sulfate and were dialyzed against three changes of 0.1 M Tris–0.11 M NaCl buffer (pH 8.2). DEAE-Sephadex A-25 (Pharmacia) was rehydrated in the same Tris buffer, and a column volume of 40 ml was used for each 50 ml of precipitated antibody. Dialyzed antibodies in Tris buffer were applied to the column, and the unbound fractions, which contained immunoglobulin G (IgG), were concentrated to one-half of their original volume with a YM-30 membrane (Amicon, Danvers, Mass.). Concentrated antibodies were then dialyzed against three, 500-ml changes of PBS (pH 7.2). Purified IgG was then labeled with horseradish peroxidase (HRPO; Sigma), after oxidation of the HRPO by using a 50:1 molar ratio of NaIO4 to HRPO (43). Excess NaIO4 was removed on a Sephadex G-25 column (1 by 25 cm) equilibrated with 0.005 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.4). The purified IgG was then added dropwise to the oxidized HRPO solution with constant gentle agitation. The reaction was allowed to proceed for 2 h at 23°C, and then a 4-mg/ml solution of NaCNBH3 was added to give a final concentration of 0.004 mg of NaCNBH3 per mg of IgG. This reaction was allowed to continue overnight at 4°C to produce a stable HRPO-IgG conjugate. Solid NaBH4 was then added to a final concentration of 2 mg per ml to stop the reaction. The conjugated IgG was dialyzed against three, 20-volume changes of PBS (pH 7.2) at 4°C overnight.

Experimental model of invasive aspergillosis.

Female New Zealand White rabbits (weight, 2 to 3 kg) were immunosuppressed by subcutaneous injection of 25 mg of cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan; Mead-Johnson, Princeton, N.J.) per kg of body weight and 15 mg of cortisone acetate (Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, Ind.) per kg 2 days before infection. The rabbits were given an additional 15 mg of cortisone acetate per kg 1 day before and on the day of infection. The rabbits were infected intravenously with 107 A. fumigatus conidia washed from SDA slants after 4 days of growth at 37°C. Blood was collected daily and was placed into Isolator tubes (Wampole, Inc., Cranbury, N.J.) for subsequent culture on SDA plates and into untreated tubes for preparation of serum. Urine was collected daily from the metabolic cages that housed the rabbits, and 0.5 ml was plated onto SDA for CFU determination. The remaining urine was centrifuged for 10 min at 2,700 rpm in a Beckman TJ-6 centrifuge (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.), and the supernatant was frozen until it was used. Fecal pellets were also collected, weighed, homogenized in sterile saline, and plated onto SDA to determine the numbers of CFU per gram. At experiment termination (day 3 or 4 after infection), the rabbits were euthanatized by lethal injection and were necropsied. The organs were removed, weighed, and homogenized in sterile PBS in a Waring blender (hearts, lungs, and kidneys) or in a tissue homogenizer (Stomacher 80; Seward Medical Co., London, United Kingdom) (spleens and livers) prior to plating onto SDA for determination of the number of CFU per gram. Portions of the organs were reserved, fixed in formalin, and embedded in paraffin prior to histochemical staining of thin sections with hematoxylin-eosin or Gomori methenamine silver stain.

Immunosuppressed and nonimmunosuppressed control rabbits were infected intravenously with 1 × 107 yeast cells or 1 × 108 bacteria and intraurethrally or intragastrically with 2 × 108 yeast cells or bacteria (specific strains are described above in the section entitled Microorganisms).

Competitive binding inhibition EIA.

Microtitration plates (Immulon II; Dynatech Industries, Inc., McLean, Va.) were coated with 100 μl of a 10-ng/ml solution of GM-containing antigen in PBS and were incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates could be stored for up to 3 weeks at 4°C with no detectable deterioration of results. Immediately before use, the plates were washed three times in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and residual moisture was removed by vigorously tapping inverted plates repeatedly onto several layers of paper towels.

Urine samples were dialyzed against two changes of 100-fold volumes of PBS prior to use. Urine or serum (0.5 ml) was mixed with an equal volume of 0.1 M EDTA (pH 7.0) in 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, boiled in a water bath for 10 min, cooled on ice, and centrifuged for 30 min at 13,000 rpm (model 5403; Eppendorf, Inc., Newton, Conn.). The supernatant (0.2 ml) was then mixed with 0.2 ml of a 1:3,000 dilution of HRPO-labeled anti-GM antibody, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 25°C in a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube. One hundred microliters of the mixture was then added in triplicate to wells of the precoated 96-well microtitration plate, and the plate was incubated for 30 min at 25°C. The plates were washed four times with PBS-T to remove unbound antibody. One hundred microliters of a 50:50 mixture of tetramethylbenzidine substrate and H2O2 solution (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) was added, and the plate was read immediately at an absorbance of 650 nm in a kinetic microtitration plate reader (UV Max; Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.). The results were reported as percent inhibition of labeled antibody binding relative to labeled antibody binding in control wells that contained preinfection serum or urine. Samples that gave inhibition values greater than 1.51 standard deviations (SDs) above the mean percent inhibition for negative control serum samples (mean ± SD percent inhibition = 2.18 ± 4.84 [n = 14], or 9.5% inhibition) and 1.78 SD above the mean percent inhibition for negative control urine samples (mean ± SD percent inhibition = 2.77 ± 3.5 [n = 9], or 9.0% inhibition) were designated positive.

Standardization of EIA results.

Each microtitration plate contained preinfection serum or preinfection urine as negative control samples, and absorbance values for these samples were used as the baseline values from which to calculate percent inhibition. The inhibition EIA was standardized by using known quantities of the GM-containing antigen. The conversion of percent inhibition to nanograms per milliliter was calculated from a standard curve constructed by using known quantities of antigen preparation that were serially diluted in negative control serum or urine. A positive EIA result was therefore designated as a value above 18 ng/ml (or >9.0% inhibition) for urine samples or as a value above 18.8 ng/ml (or >9.5% inhibition) for serum samples. Because the alkaline extract of mycelial cell walls used to construct the standard curve and to coat the microtitration plates contained proteins, mannoproteins, and other carbohydrates to which our polyclonal antibodies reacted, as well as GM, and because the total carbohydrate content of the alkaline extract was determined to be 28% by weight, the EIA therefore detected approximately 5 ng of total carbohydrate per ml and smaller amounts of GM (see Fig. 1).

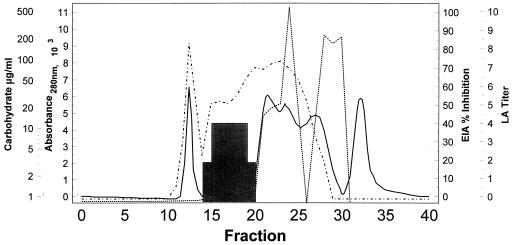

FIG. 1.

Column fractionation of GM-containing antigen preparation made from alkali-extracted mycelial cell walls. This preparation was used to construct standard curves and to coat microtitration plates for the inhibition EIA. Total protein is represented by the solid line (denoting spectrophotometric absorbance at 280 nm), total carbohydrate (CHO; phenol-sulfuric acid determination) is designated by the dotted line, the reactivities of the fractions in the inhibition EIA are designated by the dashed line (EIA), and the reactivities of the fractions with the Pastorex Aspergillus LA monoclonal antibody are designated by the shaded area (LA titer).

LA.

The Aspergillus LA (Pastorex Aspergillus; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 300 μl of serum or dialyzed urine was mixed with 100 μl of treatment reagent in a 0.5-ml polyethylene Eppendorf tube, mixed with a vortex mixer, and heated in a boiling water bath for 3 min. The mixture was then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Forty microliters of the supernatant was added to 10 μl of latex reagent, and these components were mixed with a plastic applicator stick on the surface of the reaction card provided by the manufacturer. The cards were then rotated at 160 rpm on a clinical rotator (model 3623; Thomas, Inc., Philadelphia, Pa.) for 5 min. The results were read immediately as the degree of agglutination present. Although the LA is designed so that the results are reported as positive or negative by the presence or absence of agglutination, we were able to further stratify agglutination reactions into those with 75 to 100% agglutination (assigned a reading of +4), those with 50 to 75% agglutination (+3), those with 25 to 50% agglutination (+2), and those with 25% or less agglutination (+1). By definition, all values greater than or equal to 1 were considered positive.

SEIA.

The SEIA (PLATELLA Aspergillus; Sanofi Diagnostics Pasteur) was performed as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, 300 μl of serum or urine was placed into a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube, and 100 μl of treatment solution from the kit was added. The tubes were vortex mixed for 2 s and were then placed into a boiling water bath for 3 min. After cooling to ambient temperature, the tubes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Supernatants from heat-treated test samples (50 μl) and 50 μl of HRPO-conjugated anti-GM monoclonal antibody were delivered into wells of a microtiter plate that had been coated by the manufacturer with monoclonal antibody. The plates were sealed with adhesive film, incubated for 90 min at 37°C, and then washed five times with the wash solution provided as part of the commercial SEIA kit. Two hundred microliters of substrate-chromogen solution was then added to each well, and the plate was incubated for 30 min in the dark at ambient temperature. The reaction was stopped by adding 100 μl of 1.5 M sulfuric acid. The absorbance of each well was then read at 450 nm in a microtitration plate reader (SpectraMax; Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.). Standards, supplied by the manufacturer and run on each test plate, were treated identically to the test samples and were used to determine test sample positivity or negativity. The positivity index for each sample was calculated as the ratio of the absorbance of the test sample to the absorbance of the serum sample included in the test kit. The manufacturer considers an index of 1.5 or greater to be a true-positive result and indices of between 1 and 1.5 to be borderline positive results. Therefore, for the purposes of this study, we considered any samples with an index of 1 or greater to be positive unless stated otherwise.

Statistical analyses.

Means are expressed plus or minus the standard error of the mean for the number of experiments or animals designated. A P value of <0.05 by the Student t test or by chi-square analysis was considered significant.

RESULTS

Composition of EIA antigen and its reactivity with monoclonal and polyclonal anti-GM antibodies.

Figure 1 shows the elution profile of the cold alkali-extracted GM-containing antigen as it was column fractionated. The reactivities of these column fractions with the polyclonal anti-cell wall antibodies used in the inhibition EIA and the monoclonal anti-GM antibody provided in the LA (and SEIA) kit are also shown. As demonstrated in Fig. 1, the polyclonal antibodies used in the inhibition EIA reacted not only with GM (fractions 14 to 20) but also with other carbohydrate moieties (most notably, fractions 20 to 26), as well as with protein moieties (fractions 11 to 14 and 20 to 29). In contrast, the LA antibody reacted with GM alone (fractions 14 to 20). Therefore, the antibodies used in the inhibition EIA recognized multiple antigenic epitopes of A. fumigatus, including some not recognized by the monoclonal LA antibody.

Culture positivity of organs and other specimens from A. fumigatus-infected rabbits during disease progression.

A. fumigatus was recovered from the feces and urine of a minority of infected rabbits beginning on days 2 and 3, respectively (Table 1). By contrast, A. fumigatus was recovered from the blood of the majority (13 of 15 [87%]) of rabbits on day 1 after infection and from 13 and 50% of rabbits on days 2 and 4, respectively. Disseminated disease was confirmed by positive culture of specimens from deep tissues at days 3 and 4 after infection. Kidneys from all rabbits (15 of 15 [100%]), regardless of whether rabbits were euthanized on day 3 or 4, were culture positive, as were the spleen, liver, and lungs of all rabbits (7 of 7) euthanized on day 4. Compared with rabbits euthanized on day 4, rabbits euthanized on day 3 demonstrated a reduced percentage of culture-positive spleens, livers, and lungs (75 to 88%) and a somewhat higher percentage of culture-positive hearts (71 versus 57%). The highest mean number of CFU recovered per gram of tissue was from the kidney and spleen, followed by the liver and lung; the lowest mean number of CFU was recovered from the heart (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Culture positivity of organs or other specimens from A. fumigatus-infected rabbits during disease progression

| Day and parameter | Urine | Blood | Feces | Left kidney | Right kidney | Spleen | Liver | Lung | Heart |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | |||||||||

| No. (%) culture positivea | 0/12 (0) | 0/14 (0) | 0/12 (0) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD no. of CFU (n)b | 0 ± 0 (12) | 0 ± 0 (14) | 0 ± 0 (15) | ||||||

| Range of CFU | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | ||||||

| Day 1 | |||||||||

| No. (%) culture positive | 0/15 (0) | 13/15 (87) | 0/15 (0) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD no. of CFU (n) | 0 ± 0 (15) | 8.0 ± 21.0 (15) | 0 ± 0 (15) | ||||||

| Range of CFU | 0–0 | 0–80 | 0–0 | ||||||

| Day 2 | |||||||||

| No. (%) culture positive | 0/15 (0) | 2/15 (13) | 1/15 (7) | ||||||

| Mean ± SD no. of CFU (n) | 0 ± 0 (15) | 0.05 ± 0.16 (15) | 1.4 ± 5.5 (15) | ||||||

| Range of CFU | 0–0 | 0–0.6 | 0–21.4 | ||||||

| Day 3 | |||||||||

| No. (%) culture positive | 1/15 (7) | 3/14 (21) | 1/15 (7) | 8/8 (100) | 8/8 (100) | 6/8 (75) | 6/8 (75) | 7/8 (88) | 5/7 (71) |

| Mean ± SD no. of CFU (n) | 0.13 ± 0.52 (15) | 0.04 ± 0.07 (14) | 0.45 ± 1.73 (15) | 4.9 ± 13.4 (8) | 2.9 ± 2.1 (8) | 3.8 ± 4.4 (8) | 3.3 ± 4.7 (8) | 1.8 ± 2.9 (8) | 0.08 ± 0.07 (7) |

| Range of CFU | 0–2.0 | 0–0.2 | 0–6.7 | 0.11–38.0 | 0.55–6.0 | 0–11.0 | 0–13.3 | 0–8.4 | 0–0.18 |

| Day 4 | |||||||||

| No. (%) culture positive | 1/7 (14) | 3/6 (50) | 1/7 (14) | 7/7 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 7/7 (100) | 4/7 (57) |

| Mean ± SD no. of CFU (n) | 0.29 ± 0.77 (7) | 0.37 ± 0.51 (6) | 1.36 ± 3.59 (7) | 7.1 ± 7.3 (7) | 7.8 ± 7.4 (7) | 11.2 ± 8.3 (7) | 2.7 ± 1.9 (7) | 2.0 ± 1.2 (7) | 0.14 ± 0.22 (7) |

| Range of CFU | 0–2.0 | 0–0.8 | 0–9.5 | 0.44–17.0 | 1.2–18.0 | 1.5–23.0 | 0.61–5.8 | 0.38–3.0 | 0–0.6 |

Number (percent) of rabbits whose organ or other specimen was culture positive.

Mean ± SD number of CFU per milliliter for blood and urine and per gram (wet weight) for organs and feces for the number (n) of rabbits indicated in parentheses; rabbits were euthanatized and necropsied on day 3 or 4 after infection.

Detection of antigenemia in A. fumigatus-infected rabbits.

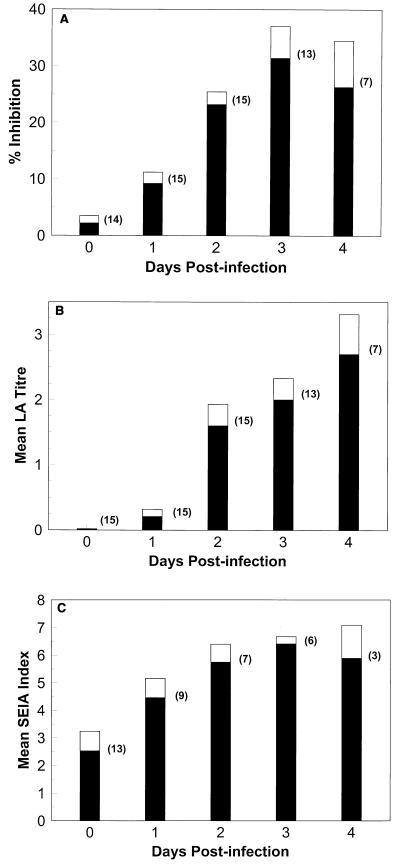

Figures 2A, B, and C depict the detection of antigenemia by EIA, LA, and SEIA, respectively, during the course of disease progression in rabbits infected systemically with A. fumigatus. All assays detected an increase in the amount of antigen present in the serum of infected rabbits over time (days 1 to 4; Fig. 2A, B, and C), corresponding to increased disease severity (Table 1). The increase in the amount of detectable antigen over time was consistent when each rabbit was monitored individually (data not shown). A slight but insignificant reduction in the mean percent inhibition results for the EIA and in the mean SEIA index values at day 4 after infection relative to those at day 3 after infection was noted when mean test values for all rabbits were expressed (Fig. 2A and C).

FIG. 2.

Reactivities of serum samples from Aspergillus-infected rabbits by day after infection. Rabbits were infected on day 0 with 107 A. fumigatus conidia. (A) Mean percent inhibition by EIA for serum samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection; (B) mean LA titer for serum samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection; (C) mean SEIA index for serum samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection. Shaded portions, means; unshaded portions, standard errors.

EIA detected antigenemia as early as 1 day after infection in 53% (8 of 15) of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits (Table 2), with only one false-positive result at day 0 (preinfection). LA was positive for antigenemia in 27% (4 of 15) of infected rabbits by 1 day postinfection, with no false-positive results detected preinfection (Table 2). In contrast, SEIA detected antigenemia in 92% (11 of 12) of infected rabbits by 1 day after infection but gave false-positive results for 50% (5 of 10) of rabbits whose samples were obtained on day 0 (preinfection). By days 3 and 4 after infection, both EIA and LA detected antigenemia in 93% (14 of 15) of infected rabbits, whereas SEIA detected antigenemia in 100% (12 of 12) of the A. fumigatus-infected rabbits (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Cumulative number of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits whose serum and/or urine became positive for antigen by a given day after infection

| Day after infection | No. of rabbits antigen positive/total no. of rabbits (%)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIA

|

LA

|

SEIA

|

|||||

| Serum | Urine | Botha | Serum | Urine | Serum | Urine | |

| 0b | 1/14 (7) | 0/9 (0) | 1/14 (7) | 0/15 (0) | 11/14 (79)c | 5/10 (50)c | 9/10 (90)c |

| 1 | 8/15 (53) | 3/14 (21) | 10/15 (67) | 4/15 (27) | 13/14 (93) | 11/12 (92) | 10/10 (100) |

| 2 | 14/15 (93) | 9/15 (60) | 14/15 (93) | 13/15 (87) | 15/15 (100) | 12/12 (100) | 10/10 (100) |

| 3 | 14/15 (93) | 11/15 (73) | 14/15 (93) | 14/15 (93) | 15/15 (100) | 12/12 (100) | 10/10 (100) |

| 4 | 14/15 (93) | 14/15 (93) | 15/15 (100) | 14/15 (93) | 15/15 (100) | 12/12 (100) | 10/10 (100) |

Rabbits were positive for antigenemia and/or antigenuria.

Data are for serum and urine specimens collected prior to A. fumigatus infection (day 0 or earlier).

Significantly (P < 0.001) more false-positive results by LA and/or SEIA than by EIA.

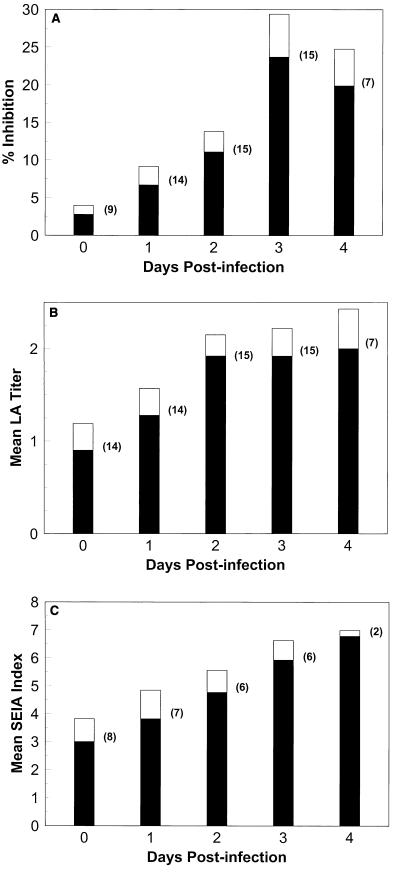

Detection of antigenuria in A. fumigatus-infected rabbits.

Figures 3A, B, and C depict the detection of antigenuria by EIA, LA, and SEIA, respectively, during the course of invasive disease progression in rabbits experimentally infected with A. fumigatus. All three assays detected an increase in the amount of antigen in the urine of infected animals over time (Fig. 3A, B, and C), correlating with increased disease progression (Table 1). EIA detected antigenuria as early as 1 day after infection in 21% (3 of 14) of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits, with no false-positive results for samples obtained on day 0 (preinfection) (Table 2). LA and SEIA detected antigenuria in 93% (13 of 14) and 100% (10 of 10) of rabbits, respectively, by day 1; however, LA was false positive for 79% (11 of 14) of rabbits and SEIA was false positive for 90% (9 of 10) of rabbits prior to infection (day 0) (Table 2). The rates of antigenuria detection were 73, 100, and 100% for EIA, LA, and SEIA, respectively, by day 3 after infection and 93 to 100% for all tests by day 4 after infection (Table 2).

FIG. 3.

Reactivities of urine samples from Aspergillus-infected rabbits by day after infection. Rabbits were infected on day 0 with 107 A. fumigatus conidia. (A) Mean percent inhibition by EIA for urine samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection; (B) mean LA titer for urine samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection; (C) mean SEIA index for urine samples from the number of rabbits indicated in parentheses for a given day after infection. Shaded poritons, means; unshaded portions, standard errors.

Diagnosis of IA with antigenemia and antigenuria data for A. fumigatus-infected rabbits combined.

When EIA data for urine and serum were combined (i.e., where rabbit serum and/or urine was positive on a given day; see Table 2), use of results for both specimens gave the highest sensitivity for detection and also gave good specificity (67% positive by day 1 after infection, 93% positive by days 2 and 3, and 100% positive by day 4, with only one false-positive sample on day 0). In contrast, combination of the results obtained for serum with those obtained for urine did not improve the ability of LA or SEIA to diagnose IA because the low specificity of the results for urine lowered the specificity of the results for serum in both tests. For the same reason, combination of the LA or SEIA results with those of EIA also did not improve the specificity; therefore, use of the data obtained by EIA alone for serum and urine combined was sufficient to result in an improved means of diagnosis.

Sensitivities and specificities of EIA, LA, and SEIA for detection of antigenemia and antigenuria in rabbits.

Table 3 depicts the number of rabbits (including the numbers of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits described above, uninfected rabbits, and those infected with other fungi or bacteria) that were either true positive or false positive by EIA, LA, and SEIA by day 4 after infection. The percentages of rabbits that tested true positive for antigenemia by EIA, LA, and SEIA were equivalent (93, 93, and 100%, respectively). The percentage of false-positive results was greatest for SEIA (23%), but this percentage was not significantly different (P > 0.05) from those for EIA (14%) or LA (11%) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Number of rabbits testing true or false positive by EIA, LA, and SEIA

| Test | No. of rabbits with the indicated result/total no. of rabbits (%)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum

|

Urine

|

|||

| True positive | False positive | True positive | False positive | |

| EIA | 14/15 (93) | 3/21 (14) | 14/15 (93) | 3/21 (14) |

| LA | 14/15 (93) | 4/36 (11) | 15/15 (100) | 26/31 (84)b |

| SEIA | 12/12 (100) | 6/26 (23) | 10/10 (100) | 19/21 (90)b |

| SEIAc | 10/11 (91) | 1/31 (3) | 8/9 (89) | 11/27 (41)b |

Cumulative number of A. fumigatus-infected and control rabbits that tested true or false positive over the total number of rabbits tested by day 4 after infection.

Significantly greater number of false-positive results by LA and SEIA than by EIA (P < 0.001).

Use of the criterion for SEIA that more than one sample from serially collected specimens be positive for true positivity or false positivity.

The percentages of rabbits true positive for antigenuria by EIA, LA, and SEIA were also equivalent (93, 100, and 100%, respectively); however, the percentages of false-positive results were significantly (P < 0.001) greater for LA (84%) and SEIA (90%) than for EIA. Therefore, although EIA accurately detected antigenuria as well as antigenemia, LA and SEIA accurately detected antigenemia alone.

Others have suggested (38) that SEIA be considered true positive only when more than one sample from serially collected specimens is positive. Using this criterion when examining serum specimens, we found that although the number of true-positive rabbits fell from 100 to 91% (Table 3; SEIA), the proportion of false-positive rabbits was significantly (P < 0.05) reduced from 23 to only 3%. Even more striking, when examining urine specimens we found that although the proportion of true-positive rabbits fell from 100 to 89%, the proportion of false-positive rabbits fell significantly (P < 0.05) from 90 to 41%. No significant differences between SEIA results were observed whether a positive cutoff value of 1.0 or 1.5 was used.

Overall sensitivity and specificity of EIA, LA, and SEIA for detection of antigenemia and antigenuria for all samples tested.

The overall sensitivity and specificity for each of the assays for all samples tested (serum, n = 167; urine, n = 198) at all time points and for all rabbits were then calculated. The final overall test sensitivity and specificity for the EIA were 73 and 85%, respectively, for serum, 55 and 92%, respectively, for urine, and 63 and 89%, respectively, when data for serum and urine were combined (Table 4). Overall EIA specificity could be improved to 98% for serum and 97% for urine if the cutoff values for positivity were raised from 9.0 to 16.2% inhibition for serum and from 9.5 to 13% inhibition for urine. Unfortunately, whereas test specificity was improved by the higher positive cutoff values, test sensitivity fell to 63% for serum, 45% for urine, and 54% when data for serum and urine were combined (Table 4). Therefore, the original cutoff values for positivity were retained.

TABLE 4.

Overall sensitivity and specificity of EIA, LA, and SEIA for all samples tested by a given day after infection

| Day after infection | % Sensitivity/% specificity

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIA

|

LA

|

SEIA

|

|||||||

| Serum | Urine | Both | Serum | Urine | Both | Serum | Urine | Both | |

| 0a | 0/93 | 0/95 | 0/94 | 0/93 | 0/51 | 0/65 | 0/65 | 0/26 | 0/41 |

| 1 | 47/67 | 21/89 | 34/87 | 27/92 | 93/11 | 89/57 | 89/100 | 86/17 | 88/58 |

| 2 | 93/83 | 53/100 | 73/94 | 87/92 | 93/30 | 90/65 | 100/83 | 100/50 | 100/67 |

| 3 | 85/88 | 67/92 | 75/90 | 85/85 | 80/0 | 82/48 | 100/100 | 100/25 | 100/57 |

| 4 | 71/86 | 82/90 | 78/89 | 83/75 | 86/30 | 85/56 | 100/100 | 100/57 | 100/84 |

| All daysb | 73/85 | 55/92 | 63/89 | 67/89 | 88/38 | 78/60 | 96/84 | 95/31 | 96/56 |

| All days (high)c | 63/98 | 45/97 | 54/97 | 47/91 | 63/64 | 55/76 | 96/86 | 90/92 | 93/89 |

Specimens were collected prior to infection (day 0 or earlier).

Overall test sensitivities and specificities for serum specimens (n = 167), urine specimens (n = 198), or both types of specimens for all days tested by using the standard positive cutoff values described in Materials and Methods.

Overall test sensitivities and specificities for serum specimens (n = 167), urine specimens (n = 198), or both types of specimens for all days tested by using the high-positive cutoff values described in the Results section.

We found that the inhibition EIA could be used to detect GM in urine as well as in serum, although the use of serum gave a higher overall sensitivity than the use of urine (73 versus 55%) and the use of urine gave a higher overall specificity than the use of serum (92 versus 85%) (Table 4). GM was detected earlier in serum than in urine (the serum of 53% of rabbits by day 1 versus the urine of 21% of rabbits by day 1) (Table 2). This increased rate of detection of GM in serum remained until day 4 after infection (at which time both the serum and urine of 93% of rabbits were positive). The maximum detection of GM in serum coincided with the greatest number of CFU recoverable from blood (Table 1) and declined with a decrease in the number CFU in blood but was delayed by 1 day (i.e., the peak number of CFU recoverable from blood occurred on day 1 after infection [13 of 15 rabbits were culture positive; mean = 8 CFU/ml] and peak overall EIA sensitivity for GM detection was on day 2 [93% sensitivity]). The large number of culture-positive blood specimens collected 1 day after infection may be the result of the intravenous route of infection used, whereas the fact that the rate of positivity for the samples progressively increased between days 2 and 4 probably reflected true shedding of organisms from deep tissue sites. The overall sensitivity for the detection of GM in urine increased over time, paralleling the recoverable number of CFU and disease progression.

The final overall test sensitivity and specificity for LA were 67 and 89%, respectively, for serum, 88 and 38%, respectively, for urine, and 78 and 60%, respectively, when data for serum and urine were combined (Table 4). Raising the positive cutoff value from +1 to +2 increased the overall test specificity to 91% for serum, 64% for urine, and 76% for serum and urine combined. However, the corresponding test sensitivities fell to 47% for serum, 63% for urine, and 55% for serum and urine combined (Table 4). Therefore, a positive cutoff value of +1 was retained.

The final overall test sensitivity and specificity for SEIA were 96 and 84%, respectively, for serum, 95 and 31%, respectively, for urine, and 96 and 56%, respectively, for serum and urine combined (Table 4). When a cutoff value for positivity of 1.5 or greater rather than a value of 1 or greater was used, the postinfection sensitivity of SEIA was unchanged or decreased to 96% for serum, 90% for urine, and 93% for serum and urine combined. The specificity of SEIA before and after infection was changed very little by the new cutoff value (86% for serum) but was dramatically increased to 92% for urine and 89% for serum and urine combined. Overall test sensitivities and specificities were therefore raised to 96 and 86%, respectively, for serum, 90 and 92%, respectively, for urine, and 93 and 89%, respectively, for serum and urine combined. These results indicate that the more stringent positive cutoff value of 1.5 should be used when urine specimens are to be evaluated. Despite the excellent sensitivity achieved for serum samples by SEIA when either positive cutoff value was used, the relatively low preinfection specificity (65 to 70%) remained.

DISCUSSION

We compared a commercial LA and SEIA with a competitive binding inhibition EIA developed in our laboratory for their capacities to detect GM in serum and urine obtained from a panel of well-characterized, uniformly immunocompromised, and A. fumigatus-infected rabbits and their controls to determine the potential utility and limitations of these tests for the diagnosis of aspergillosis. The kinetics of antigenemia and antigenuria detection in Aspergillus-infected rabbits by all three tests mirrored disease progression, as the mean detectable levels of GM increased with time after infection. The proportion of Aspergillus-infected rabbits with GM-positive serum or urine also increased with time to reach 93 to 100% of all rabbits for all tests. However, a major advantage of EIA was its capacity to detect GM in serum as early as 1 day after infection in 53% of rabbits, whereas GM was detected by LA in only 27% of rabbits at this same time point. If EIA results for both serum and urine were combined, GM could be detected in 67% of rabbits as early as 1 day after infection. Because earlier detection has been associated with a better prognosis for Aspergillus-infected patients (1, 6, 9, 35), it can be speculated that use of EIA may better reduce patient morbidity and/or mortality compared to use of LA, especially if data collected for both serum and urine are used. Others have suggested that LA is inadequate for early detection of aspergillosis compared to SEIA (37, 38). However, the reduced preinfection specificity of SEIA compared to that of LA observed in our study suggests that SEIA may give rise to more false-positive diagnoses.

Although SEIA detected GM in the serum of 92% of rabbits 1 day after infection, SEIA demonstrated such poor specificity (i.e., false-positive results were obtained for 50% of rabbits before Aspergillus infection) that the advantage provided by the high sensitivity was confounded. This is in contrast to the high specificities of EIA and LA, in that serum from one or no rabbits, respectively, was false positive before Aspergillus infection. Other researchers have also reported that the sensitivity of SEIA is greater than that of LA, that SEIA can provide a diagnosis earlier than LA, but that SEIA is also more prone to false-positive results (31, 33, 35, 38). Therefore, it has been suggested that at least two consecutive specimens positive by SEIA must be obtained from a given patient before the test can be considered true positive (34, 38). We have confirmed these observations. If individual rabbits were tested before A. fumigatus infection, 50% (5 of 10) had false-positive SEIA results for serum. Despite this low preinfection specificity, if serial samples were monitored over time and if data for non-A. fumigatus-infected rabbits were added to the equation, the overall test specificity was significantly higher (i.e., only 23% [6 of 26] of the rabbits had false-positive results, and the overall sample specificity was 84 to 86% for serum, depending upon the positive cutoff value used).

It is not understood why SEIA gave such a high percentage of false-positive results compared to the percentage obtained by other tests when preinfection samples were tested. Cyclophosphamide, a common immunosuppressive agent and one of two used in the present animal model of IA, has been reported to cause false-positive SEIA results (13). Others have reported that false-positive SEIA reactions occur most often within the 30 days following bone marrow transplantation, when patients are receiving strong immunosuppressive therapy (17, 33, 38). Therefore, because many of the rabbits (and all of the A. fumigatus-infected rabbits) used in the current study were intentionally immunosuppressed before infection, such treatment may have increased the number of false-positive SEIA results. Alternatively, the high rate of false-positive SEIA results suggests that the galactofuranose-specific rat monoclonal antibodies used in the SEIA kit cross-react with the same sugar or a closely related carbohydrate that is a normal constituent of serum. Other researchers (34) have demonstrated cross-reactivity of the SEIA monoclonal antibodies with exoantigens obtained from a variety of fungi as well as with serum samples obtained from patients with positive blood cultures for several bacterial genera. However, LA gives fewer false-positive results with serum and uses the same rat monoclonal antibody, although in a different test format.

In contrast to the results of SEIA, the results of EIA and LA for serum specimens demonstrated high specificities when samples were collected from A. fumigatus-infected or control rabbits (i.e., for LA and EIA, 0 and 7% false-positive A. fumigatus-infected rabbits, respectively, 11 and 14% false-positive A. fumigatus-infected and control rabbits, respectively, and 89 or 85% overall specificity for all serum samples, respectively). LA, however, had low specificity (79 to 84% false-positive results for rabbits and 38 to 64% overall specificity, depending upon the positive cutoff value used) when urine was tested, which may indicate that cyclophosphamide affected the specificity of LA for urine specimens (13) but not for serum specimens. The cross-reactivity of LA with antigens of certain other fungi, including airborne contaminants, has also been reported (17).

SEIA had poor specificity for detection of GM in urine from A. fumigatus-infected rabbits and their controls (90% of rabbits had false-positive results). Only when serial specimens were collected from all rabbits over time was specificity increased to 31 or 92%, depending upon the positive cutoff value used. In contrast, EIA demonstrated high specificity for GM detection in urine from A. fumigatus-infected rabbits (0% of rabbits had false-positive results) and their controls (14% of rabbits had false-positive results) and gave an overall specificity in tests with urine of 92 or 97%, depending upon the positive cutoff value used. Therefore, EIA could be used to detect antigenuria as well as antigenemia even when few serial samples are available. LA and SEIA, especially when they are used with urine specimens, may require serial positive samples and confirmation of suspected IA by at least a characteristic chest roentgenogram or computed tomographic image (7, 19) in the absence of a positive culture or histopathology result because of poor specificity.

Other researchers (15, 31) have also indicated that detection of GM by LA or SEIA is more specific when serum rather than urine is used. Whereas Haynes and Rogers (15) reported a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 90% for LA with serum, the same test gave false-positive results for 42% of urine specimens obtained from control patients. These results suggest that galactofuranose may be a breakdown product of a related carbohydrate that occurs naturally in urine or that the LA monoclonal antibody cross-reacts with other carbohydrate breakdown products.

Stynen et al. (31) reported that SEIA was better suited for detection of GM in serum than detection of GM in urine because test sensitivity for serum was 100%, whereas test sensitivity for urine was only 71%. In contrast, Ansorg et al. (4) found urine to be superior to serum for the detection of GM after modification of LA by concentrating the urine and using a longer reaction time. Under these conditions, antigenuria preceded antigenemia and was more persistent. Sensitivities for autopsy-proven and clinically suspected aspergillosis were 43% for serum and 57% for urine; the specificity, however, was only 53% for both serum and urine.

An inhibition EIA format was used in the present study. Attempts to design an SEIA were not successful because of the high background reactivities of the reagents (data not shown). It is speculated that anti-idiotypic antibodies were produced during the immunization process so that background readings were excessively high; therefore, an inhibition format gave superior test results. Others have also reported that an inhibition EIA format could be used for the detection of GM in urine as well as in serum. Early work by DuPont et al. (11), using an inhibition EIA format as well as a radioimmunoassay, showed that urine was superior to serum for detection of GM. The serum of only 33% of A. fumigatus-infected rabbits (and 17% of patients) gave positive results, but the urine of 100% of these rabbits (and 54% of patients) was positive for the antigen. Furthermore, whereas positive results for serum did not occur until 48 h after infection, positive results for urine occurred as early as the day after infection and urine antigen levels increased with disease progression (11).

Although EIA, LA, and SEIA are all designed to detect GM, the A. fumigatus antigen used to construct standard curves and to coat the microtitration plates for EIA contained 28% carbohydrate and 72% protein, as analyzed by phenol-sulfuric acid analysis (10) and the Bradford assay (5), respectively. In contrast, purified GM (LA) or GM standards diluted in serum (SEIA), both of which were supplied by the manufacturers, contained 100% carbohydrate and have been characterized as purified GM with multiple repeating side chains of galactofuranose (21). The proteins in the commercial GM preparations have been destroyed by repeated treatment with hydrazine and nitrous acid (20).

Although the antibodies used in the inhibition EIA were highly reactive to proteins present in column fractions of the GM-containing antigen preparation (Fig. 1) and protein antigens of A. fumigatus have been reported to be produced in vivo (29), the proteins in the test samples were probably not responsible for any significant inhibition in EIA because samples were boiled before use to dissociate antigen-antibody complexes and precipitate proteins. The resulting precipitate was removed by centrifugation so that the proteins could not react in the EIA. Milder methods for the dissociation of antigen-antibody complexes may lead to the better detection of protein antigens by the antibodies used in this inhibition EIA.

Whereas the antibodies used in the inhibition EIA recognized the purified GM antigen supplied with the LA (and SEIA) kits (Fig. 1), other carbohydrates were also recognized. This was not the case, however, for the LA (and SEIA) monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1). The broader spectrum of antigen reactivity exhibited by the inhibition EIA antibodies may be responsible for some of the differences in the sensitivity and the specificity for the detection of IA observed by EIA compared to those for the commercial kits. Therefore, differences in the compositions of the antigens used, the use of polyclonal antibodies that react with carbohydrate moieties not recognized by the LA and SEIA monoclonal antibodies, and the different test formats used may all contribute to the observed differences in test results obtained by inhibition EIA compared to those obtained by LA and SEIA. Indeed, even when the same antigen and same monoclonal antibody used in LA and SEIA were used, differences in the test formats led to different test results, as observed by us and others (33, 35, 36). By using a double-antibody SEIA, test sensitivity was increased but test specificity was decreased. The use of a higher cutoff value for urine specimens and the use of serial positive samples helped to increase the specificity of SEIA, but the high proportion of false-positive samples preinfection was still problematic.

In summary, we used uniform, well-characterized specimens from an animal model of IA to compare the utility of EIA, LA, and SEIA for the diagnosis of IA. The results reported here suggest that EIA could be used to diagnose aspergillosis by use of both serum and urine specimens and could detect a greater number of infections in rabbits at an earlier time point and with greater specificity than the commercial tests. LA could be used to diagnose aspergillosis with serum but not urine, although LA was not as sensitive as EIA for the early detection of IA. Lastly, SEIA, while highly sensitive for the detection of GM in serum and urine, lacked specificity. The final analysis will be to compare these tests by use of well-characterized human clinical specimens. These studies are under way.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aisner J, Schimpff S C, Wiernik P H. Treatment of invasive aspergillosis: relation of early diagnosis and treatment to response. Ann Intern Med. 1977;86:539–543. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-5-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andriole V T. Infections with Aspergillus species. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(Suppl.2):S481–S486. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.supplement_2.s481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andriole V T. Aspergillus infections—problems in diagnosis and treatment. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:47–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansorg R, Heintschel von Heinegg E, Rath P M. Aspergillus antigenuria compared to antigenemia in bone marrow transplant recipients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:582–589. doi: 10.1007/BF01971310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;81:478–480. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckley H R, Richardson M D, Evans E G V, Wheat L J. Immunodiagnosis of invasive fungal infection. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30(Suppl. 1):249–260. doi: 10.1080/02681219280000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caillot D, Casasnovas O, Bernard A, Couaillier J F, Durand C, Cuisenier B, Solary E, Piard F, Petrella T, Bonnin A, Couillault G, Dumas M, Guy H. Improved management of invasive aspergillosis in neutropenic patients using early thoracic computed tomographic scan and surgery. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:139–147. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denning D, Stevens D A. The treatment of invasive aspergillosis: review of surgery and antifungal therapy of 2121 published cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:1147–1201. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denning D W. Therapeutic outcome in invasive aspergillosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23:608–615. doi: 10.1093/clinids/23.3.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubois M, Giles K A, Hamilton J K, Rebers P A, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DuPont B, Huber M, Kim S J, Bennett J E. Galactomannan antigenemia and antigenuria in aspergillosis: studies in patients and experimentally-infected rabbits. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:1–11. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gray G. Antibodies to carbohydrates: preparation of antigens by coupling carbohydrates to proteins by reductive amination with cyanoborohydride. Methods Enzymol. 1978;50:155–160. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(78)50014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashiguchi K, Niki Y, Soejima R. Cyclophosphamide induces false-positive results in detection of Aspergillus antigen in urine. Chest. 1994;105:975–976. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.3.975b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haynes K, Latge J P, Rogers T R. Detection of Aspergillus antigens associated with invasive infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2020–2044. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2040-2044.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haynes K, Rogers T R. Retrospective evaluation of a latex agglutination test for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:670–674. doi: 10.1007/BF01973998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopwood V, Johnson E M, Cornish J M, Foot A B, Evans E G, Warnock D W. Use of the Pastorex Aspergillus antigen latex agglutination test for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:210–213. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kappe R, Schulzeberge A. New cause for false-positive results with the Pastorex Aspergillus latex agglutination test. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2489–2490. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2489-2490.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kappe R, Schulzeberge A, Sonntag H G. Evaluation of eight antibody tests and one antigen test for the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Mycoses. 1996;39:13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1996.tb00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhlman J E, Fishman E K, Siegelman S S. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in acute leukemia: characteristic findings on CT, the CT halo sign, and the role of CT in early diagnosis. Radiology. 1985;157:611–614. doi: 10.1148/radiology.157.3.3864189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Latge J P. Tools and trends in the detection of Aspergillus fumigatus. Curr Top Med Mycol. 1995;6:245–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latge J P, Kobayashi H, Debeaupuis J P, Diaquin M, Sarfati J, Wieruszeski J M, Parra E, Bouchara J P, Fournet B. Chemical and immunological characterization of the extracellular galactomannan of Aspergillus fumigatus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5424–5433. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5424-5433.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manso E, Montillo M, De Sio G, D'Amico S, Discepoli G, Leoni P. Value of antigen and antibody detection in the serological diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994;13:756–760. doi: 10.1007/BF02276061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison V A, Haake R J, Weisdorf D J. Non-Candida fungal infections after bone marrow transplant: risk factors and outcome. Am J Med. 1994;96:497–503. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson T F, Miniter P, Patterson J E, Rappeport J M, Andriole V T. Aspergillus antigen detection in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1553–1558. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees J R, Pinner R W, Hajjeh R A, Brandt M E, Reingold A L. The epidemiological features of invasive mycotic infections in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1992–1993: results of population-based laboratory active surveillance. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1138–1147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiss E, Lehmann P F. Galactomannan antigenemia in invasive aspergillosis. Infect Immun. 1979;25:357–365. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.1.357-365.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rogers T R, Haynes K A, Barnes R A. Value of antigen detection in predicting invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Lancet. 1990;336:1210–1213. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92831-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Salonen J, Nikoskelainen J. Lethal infections in patients with hematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 1993;51:102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1993.tb01601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarfati J, Boucias D G, Latge J P. Antigens of Aspergillus fumigatus produced in vivo. J Med Vet Mycol. 1995;33:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saugier-Verber P, Devergie A, Sulihian A, Ribaud P, Traore F, Bourdeau-Esperou H, Gluckman E, Derouin F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in bone marrow transplant patients: results of a 5 year retrospective study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1993;12:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stynen D, Goris A, Sarfati J, Latge J P. A new sensitive sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect galactofuran in patients with invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:497–500. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.497-500.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stynen D, Sarfati J, Goris A, Prevost M-C, Lesourd M, Kamphuis H, Darras V, Latge J-P. Rat monoclonal antibody against Aspergillus galactomannan. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2237–2245. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2237-2245.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sulahian A, Tabouret M, Ribaud P, Sarfati J, Gluckman E, Latge J P, Derouin F. Comparison of an enzyme immunoassay and latex agglutination test for detection of galactomannan in the diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:139–145. doi: 10.1007/BF01591487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swanink C M A, Meis J F G M, Rijs A J M M, Donnelly J P, Verweij P E. Specificity of a sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for detecting Aspergillus galactomannan. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:257–260. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.1.257-260.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verweij P E, Donnelly J P, De Pauw B E, Meis J F G M. Prospects for the early diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis in the immunocompromised patient. Rev Med Microbiol. 1996;7:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verweij P E, Poulain D, Obayashi T, Patterson T F, Denning D W, Ponton J. Current trends in the detection of antigenaemia, metabolites and cell wall markers for the diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of fungal infections. Med Mycol. 1998;36(Suppl. 1):146–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verweij P E, Rijs A J, De Pauw B E, Horrevorts A M, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A, Meis J F. Clinical evaluation and reproducibility of the Pastorex Aspergillus antigen latex agglutination test for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis. J Clin Pathol. 1995;48:474–476. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.5.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verweij P E, Stynen D, Rijs A J, de Pauw B E, Hoogkamp-Korstanje J A, Meis J F. Sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay compared with Pastorex latex agglutination test for diagnosing invasive aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1912–1914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1912-1914.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Eiff M, Roos N, Fegeler W, von Eiff C, Zuhlsdorf M, Glaser J, van de Loo J. Pulmonary fungal infections in immunocompromised patients: incidence and risk factors. Mycoses. 1994;37:329–335. doi: 10.1111/myc.1994.37.9-10.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Eiff M, Roos N, Schulten R, Hesse M, Zuhlsdorf M, van de Loo J. Pulmonary aspergillosis: early diagnosis improves survival. Respiration. 1995;62:341–347. doi: 10.1159/000196477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walmsley S, Devi S, King S, Schneider R, Richardson S, Ford-Jones L. Invasive Aspergillus infections in a pediatric hospital: a ten year review. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1993;12:673–682. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199308000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walsh T J. Management of immunocompromised patients with evidence of an invasive mycosis. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 1993;7:1003–1026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilson M B, Nakane P K. Recent developments in the periodate method of conjugating horseradish peroxidase (HRPO) to antibodies. In: Knapp W, Holubar K, Wicks G, editors. Immunofluorescence and related staining techniques. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North Holland Biomedical Publishing Co.; 1978. p. 215. [Google Scholar]