Abstract

Advocates for structural change in the food system see opportunity in alternative food systems (AFS) to bolster sustainability and equity. Indeed, any alternative to industrial labor practices is assumed to be better. However, little is known about what types of jobs are building AFS or job quality. Failing to understand job quality in AFS risks building a sustainable but exploitative industry. Using a unique and large data set on job openings in AFS, this paper narrows this gap by providing an assessment of labor demand and job quality for AFS in the United States between 2010 and 2019. Job advertisements are matched to 2018 Standard Occupation Codes to characterize work. Wages are compared to living wage standards and median incomes by occupation and local labor market. Considering living wage tests and local labor market competitiveness together, the potential for high job quality in AFS is mixed. Optimistically, higher prices in occupation that are close to consumers and experiencing significant labor demand, like food service and sales, saw more competitive wages. However, these roles frequently failed to offer living wages. Farm work occupations underperformed compared to local labor markets. In addition, uncompetitive senior-level jobs may indicate low-quality career pathways for leadership roles charting paths forward in AFS. These results suggest more institutional action are necessary to enhance labor quality within these spaces and more broadly across the food system. These results also raise questions about who is able to participate in AFS development and whether barriers to participate may replicate equity blind spots.

Keywords: Alternative food systems, Labor quality, Living wage, Local labor markets, Sustainable food systems, Local food systems

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored deeply problematic pre-existing conditions within the industrial food system. This system of production, aggregation, distribution, and provision is associated with decreased public health, environmental degradation, heightened carbon emissions, loss of small farms and food businesses, and inequitable labor practices (Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Feenstra 1997; UCLA Labor Center 2022). Before the pandemic though, job quality in this industry was one of the least compensated and safe jobs in the United States (Food Chain Workers Alliance and Solidarity Research Cooperative 2016). Advocates for a more sustainable and equitable food system see opportunity in alternative food systems (AFS), which aim to create structural change in the food system to combat some or all of the harms associated with industrial agriculture, including poor job quality. These efforts—which are still evolving—represent a myriad of possible alternatives to industrial agriculture. However, AFS discourses frequently ignore labor issues (Allen 2004) and little is known about the AFS labor market. Failing to understand job quality trends in AFS, especially as these efforts grow in number and scale, risks expanding an exploitative food system rather than dismantling it, posing a direct threat to AFS' ability to fulfill its goals of creating positive structural change in the food system.

Using a unique and large data set of job opening advertisements, this paper analyzes contemporary (2010–2019) trends in job type and quality in AFS in the United States. The paper uses the Bureau of Labor Statistics' (BLS) 2018 Standard Occupation Codes (SOC) to identify occupations in demand in AFS. Next, the paper assesses job quality in AFS by comparing job openings' advertised compensation with county-level living wage standards for a single person and the median income for that occupation within its local labor market. These analyses show that a many occupations are in demand in AFS, reflecting the myriad ways AFS develop. The majority of firms advertising job openings are small, and engage in direct-to-consumer projects, though occupations dealing with scaling up activities are increasing. In considering living wage tests and local labor market competitiveness together, the potential for high job quality in AFS is mixed. While some important roles in food service and retail are competitive, entry-level roles in these areas struggle to earn living wages. For many other important occupations in farming, food production, community and social service, and management, AFS wages underperform based on living wage and competitive metrics. These results suggest that job quality may be a barrier to equitable AFS development. Policy intervention is needed to bolster job quality if AFS are to live up to their potential.

In the following sections, the literature review documents existing case study evidence foreshadowing job quality as a potential barrier to social equity in AFS and highlighting the need for a national assessment. The paper concludes with recommendations for policy, practice, and future research that connect economic equity with sustainability priorities.

Literature review

Alternative to what?

Alternatives to industrial agrifood systems are needed, as the latter harms public health (Fryar et al. 2012) and natural resources, increases carbon emissions, often yields monopolistic market consolidation, and tends to create poor working conditions the 21.5 million workers in the US engaged in food production, processing, distribution, retail, or food service (Food Chain Workers Alliance and Solidarity Research Cooperative 2016; Shierholz 2014). Jobs on industrial farms and processing plants are generally unsafe and poorly compensated (Getz et al. 2008; Villarejo et al. 2000; Cain et al. 2016). Poor labor conditions are embedded into the system; for example, farmworkers are excluded from legal protections for minimum wage, overtime pay, unemployment insurance, collective organizing and bargaining, and occupational health that most American workers enjoy (Rodman et al. 2016). Where such legal protections do exist at the state level, they tend to be poorly enforced. Workplace harassment, wage theft, and anti-union sentiments are commonplace, with few opportunities for recourse (Prado et al. 2021; Rodman et al. 2016). As a result, food systems jobs often fall to those with the least amount of power to change their working conditions or jobs—people of color, immigrants, and women (Holmes 2013; Farhang and Katznelson 2005).

Alternative food systems (AFS) are the many efforts to build systems that limit, halt, or even reverse the negative impacts of industrial agrifood systems. In contrast to “local,” “organic,” or other labels, AFS is a concept that de-emphasizes requirements for a particular farm size, local or regional geography, or production practice. Instead, AFS is a nebulous term, and evolves alongside efforts to build alternatives; however, commitments to community economic development, equity, and sustainability1 are central tenets to AFS because they comprise the potential benefits of an alternative to industrial food systems (Biewener 2016; Allen 2004). Finally, AFS and industrial agriculture are not strict binaries. AFS and industrial agriculture may influence each other, and even overlap (Allen 2004; Sbicca, 2015).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the problem of undervalued and mistreated workers in industrial and AFSs came to the fore. At the same time, efforts to build AFS picked up momentum in response to supply chain issues and recognition of inequality within the food chain (Graddy-Lovelace 2020; Raja 2020). However, food systems workers have been at the forefront of historic and recent efforts to improve working conditions, especially through unionization in industrial food settings (Fischer-Daly 2021; Cobble 1992; Martin 2003; Hall 2015).2 Workers have also built AFS arrangements that uphold better working conditions, such as cooperatives (White 2018).

The labor required to build alternative food systems

A wide range of intellectual and physical work is required to implement AFS arrangements across food supply chains. This includes, for example, new farming strategies like cooperative regenerative agriculture (White 2020), new meat processing strategies such as mobile slaughtering facilities that serve many small farmers collectively (Angioloni et al. 2016), innovative distribution strategies like food hubs (Cleveland et al. 2014), equitable food purchasing commitments by food service organizations (Lo and Delwiche 2016), and community composting and mobile operations to redirect waste (Veggie Rescue 2021).

Labor is an essential component of how alternatives are built. Rather than joining global supply chains that typically bring products to consumers, AFS firms often must develop new supply chains and infrastructure (Dunning 2016). As a result, much of this work is relatively experimental and small in terms of production or distribution abilities3 (Tewari et al. 2018; Schrock et al. 2019). Job openings in AFS reflect the range of ways people build alternatives, raising the first research question this paper addresses: what jobs are in demand to establish and operate AFS?

Is job quality a barrier to AFS development?

The ability of AFS to uphold its central tenets to yield economic development, equity, and sustainability benefits at the same time is contested. AFS may be an opportunity to connect ecological sustainability with social and economic justice (Feenstra 1997; Born and Purcell 2006; Alkon and Agyeman 2011). However, case studies undercut this vision, finding that AFS projects are inclined to prioritize sustainability at the expense of potentially replicating economic inequality (Biewener 2016; Daftary-Steel et al. 2015; Sbicca 2015; Soper 2020; Slocum 2006). With respect to labor, AFS are criticized for relying on free and underpaid work, poor working conditions, and exacerbating inequality based on race, class, and gender (Alkon and Agyeman 2011; Allen 2016; Janssen 2010; Myers and Sbicca 2015; MacAuley and Niewolny 2016; Minkoff-Zern 2017; Shreck et al. 2006; Guthman 2008; Gray 2013; Weiler 2021).4

AFS’ sociocultural values have been critiqued for contributing to poor labor conditions by overlooking economic equality and emphasizing conservative, white, middle-class consumer values (Fourat et al. 2020; Minkoff-Zern 2017; Slocum 2006). Allen (2004) has shown how alternative agrifood movements valorized individual farmers while relegating farmworkers to production inputs. This thread can be traced back to slavery in the United States (Farhang & Katznelson 2005). Through this discourse, working conditions and expertise are ignored, and food system workers are considered low-skilled and undeserving of proper compensation, with little to contribute in terms of building better alternatives (Weiler et al. 2016).

Today, this discourse prevents farmworkers from getting more rights, and farmworkers on smaller-scaled AFS farms may actually struggle more to earn decent wages and have safe working conditions. An FLSA amendment extended some workforce protection coverage to farmworkers on large farms, but not small farms (Rodman et al., 2016).5 Thus, while policy-makers and the public may support smaller-scale production, workers may benefit more from positions at industrialized firms through access to higher wages, benefits, and rights (Lo and Delwiche 2016; Shreck et al. 2006; Harrison and Getz 2015).6

Failing to offer good jobs curtails AFS’ ability to further equity goals or to expand. Good jobs are defined as providing (at a minimum) living wages, benefits (including paid sick days and vacation), safe working environments, training, job security, opportunities for advancement, and the ability to collectively bargain (Liu 2012; Biewener 2016; Lowe 2021). Poor wages or limited career paths may disincentivize job seekers from contributing their talents and ideas to develop better food systems. As the COVID-19 pandemic and the Great Resignation have underscored, AFS efforts will struggle to retain skilled workers without competitive wages and good working conditions, limiting their ability to succeed (Lange-Kubick 2021).

One area of interest in understanding AFS' ability to offer good jobs is the role of job satisfaction, which may supersede other factors in calculating job quality (Sull et al. 2022). For some, working in AFS, ostensibly to further its equity and sustainability goals, may offer satisfaction that offsets subpar wages or working conditions: a kind of “psychic income.” Though this contravenes certain capitalistic conditions that many have argued are fundamental distortions to the food system (Guthman 2008), a psychic income may have negative impacts in AFS. Savvy employers may exploit this logic to lower wages and lessen labor costs. Wealthier job seekers will be better able to accept psychic incomes without financial burden, and are therefore more likely to participate in AFS development, which will deepen equity blind spots and reinforce privilege (Alkon 2013; Pisani and Guzman 2016; Biewener 2016). As a result, poor wages and limited career paths may be a barrier to the development of AFS that are genuinely aligned with AFS’ core commitment to equity.

A second area of interest lies in whether higher prices for food products with AFS labeling (i.e. organic, local, non-GMO) may be leveraged into worker gains. Studies have found that consumers are more willing to pay a higher the higher prices associated with AFS products (Thilmany et al. 2008), while others found that AFS farms spend proportionately more on labor, with higher average wages per hour worked (Jablonski et al. 2021). A willingness to pay a higher price may translate to greater profits that are passed onto farmworkers. However, increased costs associated with AFS production may offset these profits, actually decreasing employee wages (Hardesty and Leff 2010). Other researchers have found that prices have little impact on farmworker incomes (Costa and Martin 2020). These arguments may be extended to workers elsewhere in the food system.

In light of these critiques and questions, and as AFS efforts increase, AFS job quality is an important factor to examine to evaluate if AFS can meet its stated goals. However, a dearth of data limits our understanding of AFS job quality and its role in AFS development. Those working between the farm and the fork, in occupations such as food production, sales, logistics, and food service, are rarely studied (Burmeister and Tanaka 2017). Some scholars have argued that a lack of national data on small farm labor, as opposed to small farm owners, has intentionally hidden inequitable labor practices on small farms (Moskowitz 2014; Arcury and Quandt 2009).7 This paper lessens these gaps by providing a national-level examination of labor demand and job quality in AFS job advertisements between 2010 and 2019.

Data and methods

Alternative food systems job data

Examinations of AFS job quality have been limited to case studies largely because data on AFS labor is not available. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Census of Agriculture does not disaggregate data from industrial farms versus AFS farms. As a result, to assess AFS jobs, this paper examines labor demand in AFS. This paper uses job opening advertisements posted between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2019, from Good Food Jobs.8 Good Food Jobs is the premier job search engine for AFSs openings in the United States. The website has posted over 40,000 jobs since it started in 2010. Each opening is vetted by a co-founder to ensure compliance with the company’s editorial policy. Their founder described the companies that seek to advertise an opening with them by saying, “our identity as a small, alternative, grassroots organization has attracted companies of the same ilk.” The editorial policy is subject to interpretation, and some standards have evolved over time,9 but it prioritizes the following principles: food justice, ecological justice, and anti-racism. The company has not posted “industrial agriculture” jobs, but has posted openings at large corporations. The dataset contains the posting date, location, company description, and job description. This data reflects labor demand in AFS.

Information about the hiring organization, and job wages, benefits, skills, and responsibilities were extracted from job advertisements when present. Some postings represented multiple openings; an observation for each position was added when the posting provided enough information. However, the dataset is an under-representation of total jobs that could have been filled. Other postings advertised multiple openings for the same position; in this case the posting was not duplicated but the presence of multiple openings was recorded. Unpaid positions (5.2% of postings), businesses for sale (less than 1%), and postings lacking adequate information (less than 1%) were removed, resulting in 38,572 advertisements representing 44,782 openings (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Job postings in alternative food systems 2010–2019

Wage information was available for 39% of postings. Compensation was standardized into hourly and annual incomes, accounting for seasonal and contract work and whether a range of compensation or hours was offered. For jobs with a range of possible compensation and hours, the minimum and maximum generated four possible scenarios. A similar process for openings with ranges in hours or wages generated two wage scenarios. For all postings with wage variability due to hours or compensation, all scenarios were averaged and used for primary analyses (Table 1).

Table 1.

AFS openings by full-time status

| Job type | Job openings | With wage info |

|---|---|---|

| Full-time | 31,165 (81%) | 11,404 (30% of all posts) |

| Part-time | 7407 (19%) | 3662 (9.5% of all posts) |

| Total | 38,572 (100%) | 15,066 (39% of all posts) |

Openings are distributed across the country, with fewer postings in Nevada and the USDA Plains region (United States Department of Agriculture 2019). This is consistent with other sources on AFS activities (Low et al. 2015) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Maps of AFS job postings by year and aggregated across the decade (2010–2019)

Characterizing AFS job openings as occupations

Each opening was matched to a Detailed 2018 SOC to characterize work involved in AFS. The BLS created the SOC classification system to classify work into 867 SOCs, which have a title and description. Jobs with the same Detailed SOC have similar duties and can be combined into increasingly general SOC groups. There are 459 Broad SOC groups, 98 Minor SOC groups, and 23 Major SOC groups (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2017).

An example of SOC code application: a pickle maker is characterized by the Detailed SOC 51-3092, titled “Food Batchmaker,” alongside ice-cream and peanut butter makers. Food Batchmakers are within the Broad SOC 51-3090, “Miscellaneous Food Processing Workers,” alongside Detailed SOC 51-3091 (“Food and Tobacco Roasting, Baking, and Drying Machines”—i.e. coffee roasters), Detailed SOC 51-3093 (“Food Cooking Machine Operators and Tenders”—i.e. frying machine operator), and Detailed SOC 51-3099 ( “Food Processing Workers, All Other”). Miscellaneous Food Processing Workers are combined with other Broad SOCs, including Broad SOC 51-3020, “Butchers and Other Meat, Poultry, and Fish Processing Workers,” and Broad SOC 51-3010, “Bakers,” into the Minor SOC 51-3000, “Food Processing Workers.” The Food Processing Workers Minor SOC is within Major SOC 51-0000, “Production Occupations.”

The Managerial Major SOC comprises Detailed SOCs that manage roles in other Major SOCs. For example, the Detailed SOC Food Service Managers is in the Managerial Occupations Major SOC. Food Service Managers manage occupations in the Major SOC group Food Preparation and Serving Occupations. For this study Detailed SOCs within the Managerial Major SOC are analyzed with the Major SOC group they manage, except for “General and Operations Managers” and “Chief Executives,” which are too general to be allocated to another Major SOC.10

A rule-based coding program matched openings to Detailed SOCs. Advertisements were sorted by title and compared to Detailed SOC titles. The closest match became the first “guess” (multiple guesses were allowed). Skills and responsibilities in job descriptions were used to confirm whether the job matched a Detailed SOC descriptions and example occupation titles from BLS and example SOC titles from the Occupational Information Network (O*NET11). Manual categorization was used to break ties, and every job posting within a SOC was manually checked for consistency and accuracy. Outliers were manually re-coded as necessary. This approach is consistent with similar approaches to this matching problem (Russ et al. 2016).

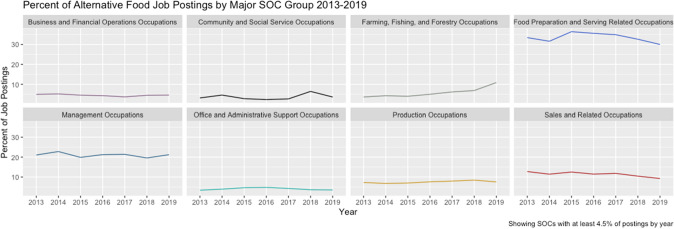

To test the accuracy of the rule-based coding, each advertisement was coded with the machine learning algorithm created by the U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the Industry and Occupation Computerized Coding System (NIOCCS). The SOCs assigned by NIOCCS were compared to SOCs assigned with the rule-based method. Strong to moderate kappa agreement with NIOCCS SOC was expected at the Major SOC level (Buckner-Petty et al. 2019; Schmitz and Forst 2016). NIOCCS SOCs had moderate to substantial agreement at the Major SOC level (Light's Kappa = 0.62, p < 0; percent agreement = 69%) and weak agreement at the Minor SOC (Light's Kappa = 0.50, p < 0; percent agreement = 53%) (McHugh 2012). This is level of agreement is acceptable because the NIOCCS algorithm was designed for health occupations only. In addition, jobs with disagreeing SOCs had titles with compound words or two words, where rule-based coding was more accurate. Out of 867 Detailed SOCs, 235 Detailed SOCs were identified; 143 Detailed SOCs had more than fifteen openings. Figure 3 shows labor demand by Major SOC for jobs with and without wage data. Jobs with wage data may differ from jobs without it, but similar distributions suggests that jobs with wage data are a useful snapshot. Across the decade the composition of labor demand in stayed relatively stable, with minor fluctuations.12

Fig. 3.

Distribution of Labor Demand in AFS from 2010–2019 for openings with and without compensation data

Living wage comparisons

One assessment of job quality is whether wages cover cost-of-living expenses. Cost-of-living expenses vary by geography; analyzing job quality with local cost-of-living conditions changes assessments of labor conditions (Grimes et al. 2019). Each opening with wage information was compared to the living wage for that county and year for a single individual—the most generous living wage calculation—accounting for employer contributions towards housing, healthcare, transportation, and food. For analysis, living wages were calculated following Nadeau and Glasmeier (2019), with a few exceptions. First, healthcare data was from the 2018 BLS Consumer Expenditure Surveys. Second, Decennial Census, American Community Survey, and Federal Communications Commission data were used to estimate cellphone and internet costs.13 Finally, local taxes are included.

Labor market comparisons

Another way to examine job quality is comparing AFS wages for a Detailed SOC to wages for the same Detailed SOC in the same labor market in other industries. Each AFS job opening with wage data was compared to the normalized distribution of hourly wages for its Detailed SOC across all industries in its respective labor market using data provided by the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OES) program of the BLS.

Labor markets were defined using OES geographies, and included Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs) and non-metropolitan areas, as well as MSA divisions for the eleven largest MSAs. An MSA is defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as containing “a core urban area of 50,000 or more population. Each MSA consists of one or more counties and includes the counties containing the core urban area, as well as any adjacent counties that have a high degree of economic and social integration (as measured by commuting to work) with the urban core” (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2020). MSA divisions are component geographies of MSAs. In New England, OES uses NECTAs and NECTA divisions which are analogous to MSAs and MSA divisions for the rest of the country but are defined in terms of cities and towns rather than counties. The OES definitions are proxies for labor markets because they are defined in terms of communities that have a high degree of economic and social integration. Data at the MSA and NECTA division was used when possible, but comparisons were made at the MSA level to allow for variation within MSAs while preserving the accuracy of MSA division-level comparisons. Out of 571 possible labor markets, 439 had one or more job openings; there were 159 labor markets with fifteen or more job openings across the decade.14

In cases where wages were suppressed in the OES data at the Detailed SOC level, Broad SOC data was used. This imputation strategy was used when either (a) the title was the same for the Broad and Detailed SOCs or (b) there were only two Detailed SOCs within the Broad SOC. In cases where the data was not available at the MSA or NECTA division level but was available at the MSA or NECTA level, the MSA or NECTA level was used. Finally, a small amount of OES data was suppressed for Detailed and Broad SOCs at division and MSA geographies; the Major SOC wages were used. There were 15,066 job postings with wage data. Of these, 14,848 openings were compared to the median hourly wage in their labor market for their Detailed SOC level, with 4% of median wages imputed from the Broad or Major SOCs.

The OES survey insufficiently samples the agriculture and forestry industry, so data from the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS) was used for agricultural production roles. NASS conducts quarterly surveys about farm labor for farms with at least $1000 in annual sales for fifteen multi-state regions and the single-state regions of California, Florida, and Hawaii (National Agricultural Statistics Service 2021).15

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test compares compensation in AFS jobs to compensation with compensation in the same occupations in other industries within the local labor market. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test is a nonparametric test that may be used to compare the distributions of paired observations.16 This test compared compensation between AFS jobs and median hourly wages in all industries, accounting for labor market and occupation (Datta and Satten 2008). This method allows for the distribution of pair-wise differences to differ between clusters. All observations were adjusted for inflation to January, 2020 dollar values. The same test compared compensation between AFS jobs and all industries for each Detailed SOC, accounting for local labor markets when there were at least fifteen observations. There were 180 distinct Detailed SOCs with wage information, and 97 Detailed SOCS with at least fifteen observations. There were no limitations on the number of labor markets allowed; of the Detailed SOCs with more than 15 observations, the number of labor market clusters ranged from 6 clusters (16 observations) to 180 clusters (680 observations). The Datta–Satten method for Wilcoxon-signed rank test accounts for cluster size by assigning equal weight to each cluster (instead of each paired difference) (Jiang et al. 2017). Significance values are shown with a correction for multiple comparisons using the Holm method (Chen et al. 2017). The null hypothesis is that AFS wages are not distributed significantly differently than wages in the same occupations and labor markets in other industries.

Results

What jobs are in demand to establish and operate AFS?

Labor demand was concentrated in work directly involved in the food chain, especially occupations in Food Preparation and Serving (37% of all job openings), Sales (13%), Farming (10%), and Production (8%). Openings within the Food Preparation and Serving and Sales Major SOCs were primarily entry-level. For food service, openings were in restaurants and cafes in front and back of house jobs. In sales, openings concentrated in retail roles at specialty food and beverage stores, consumer cooperatives, and at farmers' markets. Wholesale sales occupations were less common, but were offered at food production companies, catering and food delivery services, and food hubs.

Farm work made up 10.2% of job openings, with vegetable farmworkers being the most common occupation. The majority of farms were small to medium-sized,17 ranging from 0.25 acres to 87,000 acres, with a median of 12.5 acres and an average of 271. Not all acreage was in production. Most farms grew vegetables (88%), but half produced animal and vegetable products.

Production occupations (food processing) made up 8% of openings. Produced goods included baked goods, cuts of meat, preserved foods (i.e. jam), pre-processed (i.e. chopped carrots), fermented goods (i.e. yogurt), and alcoholic beverages. Openings were primarily at private companies, though several were cooperatively owned. Twelve percent of production job openings were on farms; the majority were dairies or farms with vegetable processing capacity.

Lower but prominent levels of openings for occupations in Business and Financial Operations, Community and Social Service, Office and Administrative Support, and Manager occupations suggests these are important supports for AFS operations. Table 2 outlines job total labor demand (TLD), or the percent of total job openings by Major SOC, and describes the location and types of firms in each occupation category.18

Table 2.

Job openings by major SOC group

| Major SOC title | Total labor demand* (%) | Cumulative labor demand** (%) | Description of labor demand |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Preparation and Serving | 36.5 | 36.5 | 4916 Firms in 49 states, primarily in restaurants and cafes. 3% of were located on farms |

| Sales | 13.4 | 49.9 | 2020 Firms in 50 states, primarily in retail stores. 14% were on farms |

| Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | 10.2 | 60.1 | 1807 Farms in 50 states had openings |

| Production | 8.3 | 68.4 | 1493 Firms in 46 states, primarily at private companies. 12% were on farms |

| Business and Financial Operations | 7.4 | 75.8 | 1347 Firms in 46 states at a range of organizations. 7% were on farms |

| Community and Social Service | 5.4 | 81.2 | 980 Firms in 50 states, primarily at non-profits. 7% were on farms |

| Office and Administrative Support | 4.5 | 85.7 | 992 Firms in 35 states at a range of organizations. 7% were on farms |

| Management | 3.7 | 89.4 | 926 Firms in 49 states at a range of organizations. 10% were on farms |

| Transportation and Material Moving | 3.3 | 92.7 | 686 Firms in 43 states at a range of organizations. 9% were on farms |

| Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media | 2.0 | 94.7 | 428 Firms in 39 states at a range of organizations. 8% were on farms |

| Educational Instruction and Library | 1.9 | 96.6 | 457 Firms in 43 states at non-profit and government organizations. 5% were on farms |

| Life, Physical, and Social Science | 1.4 | 98.0 | 321 Firms in 45 states at a range of organizations. 4% were on farms |

| Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance | 0.7 | 98.7 | 204 Firms in 33 states at a range of organizations. 11% were on farms |

| Personal Care and Service | 0.5 | 99.2 | 104 Firms in 24 states at private companies. 8% were on farms |

| Healthcare Practitioners and Technical | 0.3 | 99.5 | 83 Firms in 23 states at government agencies. 0% were on farms |

| Computer and Mathematical | 0.2 | 99.7 | 71 Firms in 18 states at a range of organizations. 8% were on farms |

| Installation, Maintenance, and Repair | 0.1 | 99.8 | 19 Firms in 10 states at a range of organizations. 16% were on farms |

| Legal | < 0.1 | ~ 100 | 7 Firms in 4 states at a range of organizations. 0% were on farms |

| Construction and Extraction | < 0.1 | ~ 100 | 3 Firms in 3 states. 0% were on farms |

| Architecture and Engineering | < 0.1 | 100 | 9 Firms in Firms in 5 states. 9% were on farms |

*Percent of job openings 2010–2019

**Cumulative percent of job openings 2010–2019

Aside from farm work itself, almost all occupation categories had some openings on farms, suggesting a diversification, growth, and added complexity for AFS farms. Farms advertised openings for community-engaged, restaurant, sales, and food processing occupations. Farms also need support from many occupations, such as business and financial support occupations or office and administrative support. This result also corroborates findings that AFS work is also building new supply chains and infrastructures: many wholesale sales occupations on farms were for food hubs that aggregate, process, and redistribute food products in place of traditional supply chains.

Several Detailed SOCs contributed outsized levels of TLD. Just 14 Detailed SOCs account for over 50% of TLD (Table 3). Further emphasizing the outsized role that Food Preparation and Serving occupations play in AFS, seven of the most common occupations are within this category. However, two important Detailed SOCs within this list are Community and Social Service Specialists and General Managers. Each provides insight into the unique work required for AFS development.

Table 3.

Most common Detailed SOCs in AFS from 2010 to 2019

| Detailed SOC title | Major SOC title | Total labor demand* | Cumulative labor demand** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chefs and Head Cooks | Food Preparation and Serving | 7.86 | 7.86 |

| First-Line Supervisors of Food Preparation and Serving Workers | Food Preparation and Serving | 5.03 | 12.89 |

| Farmers, Ranchers, and Other Agricultural Managers | Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | 4.78 | 17.67 |

| Cooks, Restaurant | Food Preparation and Serving | 4.34 | 22.01 |

| Food Preparation Workers | Food Preparation and Serving | 3.68 | 25.69 |

| Food Service Managers | Food Preparation and Serving | 3.22 | 28.91 |

| Bakers | Production | 3.13 | 32.05 |

| Retail Salespersons | Sales and Related | 3.06 | 35.07 |

| Community and Social Service Specialists, All Other | Community and Social Service | 2.97 | 38.04 |

| First-Line Supervisors of Retail Sales Workers | Sales and Related | 2.75 | 40.79 |

| General and Operations Managers | Management | 2.74 | 43.53 |

| Fast Food and Counter Workers | Food Preparation and Serving | 2.69 | 46.23 |

| Cooks, Short Order | Food Preparation and Serving | 2.66 | 48.89 |

| Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse | Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | 2.57 | 51.45 |

*Percent of job openings 2010–2019

**Cumulative percent of job openings 2010–2019

Community and Social Service Specialists are directly engaged in work that aims to fulfill the goals of AFS. Community health work engaged with nutrition, food access, and gardening at schools, community gardens, and farmers' markets. Other specialists supported land conservation, farmland access, sustainable farming practices, and farmer training programs. Economic development specialists provided local and regional branding and small business incubation support. Finally, community organizers advocated on farming practices or policy arenas at the regional and national level.

General and Operations Managers are often in new, small, and growing initiatives, as they are supervisory roles in which the responsibilities are too varied to be categorized neatly (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2017). Indeed, many of these openings were at novel, AFS-specific arrangements such as food hubs, farmers markets, farm-to-institution programs, cooperative associations (for growers and consumers), and small businesses.

Job quality: living wage comparison

For a single person with no family members—the most generous possible calculation of a living wage—67% of job openings with wage data offered an hourly living wage. Some jobs offered free housing or food; accounting for this, 70% of jobs offered an hourly living wage. Annually, 57% of jobs offered living wages; 73% of full-time jobs and 5% of part-time. Openings advertised financial benefits like 401K contributions 17% of the time, 19% advertised paid time off, and 21% advertised health insurance. These may be underestimates, as firms could have chosen not advertise benefits.

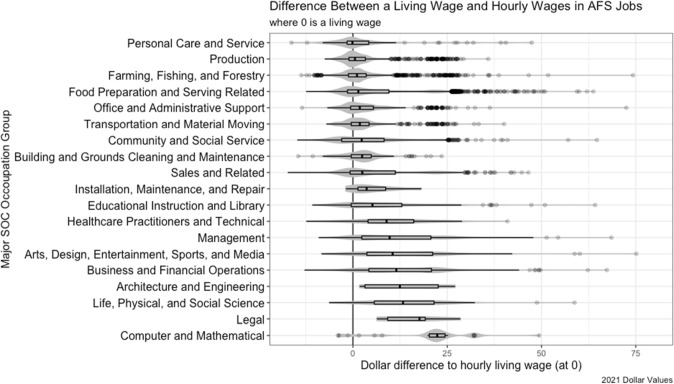

Within Major SOC groups with the most openings, Production, Farming, and Food Preparation and Service struggled to meet living wage thresholds, despite being essential to the food chain. Openings in Sales and Business and Financial Operations fared better, offering wages around or above a living wage. Figure 4 shows the distribution of differences between advertised hourly wages and corresponding living wages by Major SOC. A distribution coalescing around the vertical line at zero shows wages clustering at a living wage; the boxplots show the median difference between wages and living wages.

Fig. 4.

Difference between a living wage and hourly wages in AFS jobs

At the Detailed SOC level, unsurprisingly, senior roles are often offered living wages, while mid and entry-level roles struggle. These trends are shown for the fourteen most common Detailed SOCs in Table 4, but extend to entry level roles across AFS. When an occupation earns (on average) $0.78 less an hour than a living wage—like Fast Food and Counter Workers do—it amounts to $1435.20 less earnings annually, or 11% of someone’s annual income if they were living at or below the federal poverty line in 2019 (U.S. Census Bureau 2021). Food Preparation Workers, Short Order Cooks, Retail Salespersons, Farmworkers, and Community and Social Service Specialists were other Detailed SOCs struggling to meet living wages.

Table 4.

Most common SOCs’ living wage attainment rates

| SOC Category* | % Offered LW | Median distance to LW (w/o outliers) | Average distance to LW (w/o outliers) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Preparation and Service | 63% | $1.44 ($0.52) | $5.56 ($2.26) |

| Chefs and Head Cooks | 90% | $13.94 ($8.87) | 13.83 ($11.59) |

| First-Line Supervisors | 80% | $4.51 ($3.33) | $7.76 (5.52) |

| Cooks, Restaurant | 51% | $0.04 ($0.34) | $0.47 ($0.45) |

| Food Preparation Worker | 47% | − $0.38 (− $0.08) | $0.05 (− $0.16) |

| Food Service Managers | 94% | $19.83 (12.97) | $17.48 (14.08) |

| Fast Food and Counter Workers | 31% | − $1.97 (− $0.82) | − $0.03 (− $0.78) |

| Cooks, Short Order | 46% | − $0.45 ($0.23) | $0.20 ($0.15) |

| Sales and Related | 68% | $2.49 ($1.42) | $6.39 ($3.53) |

| Retail Salespersons | 47% | − $0.72 (− $0.57) | $0.34 (− $0.36) |

| First-Line Supervisors | 74% | $3.10 ($ 2.93) | $6.11 ($5.00) |

| Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | 78% | $1.09 ($0.80) | $2.30 ($0.80) |

| Farmers, Ranchers, and Other Agricultural Managers | 89% | $4.02 ($3.42) | $6.47 ($4.01) |

| Farmworkers and Laborers (crop, nursery, and greenhouse) | 70% | − $0.04 (− $0.02) | − $0.04 (− $0.18) |

| Production | 59% | $0.54 ($0.21) | $2.69 ($0.50) |

| Bakers | 50% | − $0.05 ($0.20) | $1.07 ($0.38) |

| Community and Social Service | 60% | $2.32 ($1.48) | $4.03 ($2.45) |

| Community and Social Service Specialists | 49% | − $0.69 ($0.83) | $1.52 ($0.58) |

| Managers | 89% | $9.74 ($7.25) | $ 11.833 ($10.05) |

| General and Operations Managers | 86% | $6.30 ($5.35) | $9.46 ($7.69 |

*Includes relevant managers

Job quality: labor market comparison

Overall, AFS occupations were offered less compensation than their local labor market counterparts in other industries (p < 0.0001). A Detailed SOC was categorized as “competitive” if the AFS wage distribution was higher than the median distribution of wages for that occupation in all other industries, accounting for the local labor market, and the difference was statistically significant. Conversely, “not competitive” Detailed SOCs’ wages were lower than the median and statistically different. “No different” Detailed SOCs’ wages were not statistically different from the median distribution for that occupation in all other industries (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Paired Wilcoxon signed-ranked test results for Detailed SOCs clustered by labor market

| Major SOC | Status^ | Detailed SOC | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media | No different | Graphic Designers | |

| Merchandise Displayers and Window Trimmers | |||

| Writers and Authors | |||

| Not competitive | Public Relations Managers | **** | |

| Public Relations Specialists | ** | ||

| Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance | No different | Landscaping and Groundskeeping Workers | |

| Not competitive | First-Line Supervisors of Landscaping, Lawn Service, and Groundskeeping Workers | **** | |

| Business and Financial Operations | No different | Accountants and Auditors | |

| Buyers and Purchasing Agents, Farm Products | |||

| Meeting, Convention, and Event Planners | |||

| Project Management Specialists and Business Operations Specialists, Other | |||

| Purchasing Managers | |||

| Not competitive | Financial Managers | ** | |

| Fundraisers | ** | ||

| Fundraising Managers | **** | ||

| Human Resources Managers | * | ||

| Logisticians | * | ||

| Management Analysts | * | ||

| Market Research Analysts and Marketing Specialists | **** | ||

| Marketing Managers | **** | ||

| Wholesale and Retail Buyers, Except Farm Products | ** | ||

| Community and Social Service | Not competitive | Community and Social Service Specialists, Other | **** |

| Health Education Specialists | **** | ||

| Social and Community Service Managers | **** | ||

| Educational Instruction and Library | No different | Career/Technical Education Teachers, Postsecondary | |

| Farm and Home Management Educators | |||

| Not competitive | Self-Enrichment Teachers | * | |

| Farming, Fishing, and Forestry | No different | Agricultural Equipment Operators | |

| Graders and Sorters, Agricultural Products | |||

| Not competitive | Farmers, Ranchers, and Other Agricultural Managers | **** | |

| Farmworkers and Laborers, Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse | **** | ||

| Farmworkers, Farm, Ranch, and Aquacultural Animals | ** | ||

| First-Line Supervisors of Farming, Fishing, and Forestry Workers | **** | ||

| Food Preparation and Serving Related | No different | Bartenders | |

| Cooks, Other | |||

| Cooks, Fast Food | |||

| Cooks, Institution and Cafeteria | |||

| Cooks, Restaurant | |||

| First-Line Supervisors of Food Preparation and Serving Workers | |||

| Food Servers, Nonrestaurant | |||

| Food Service Managers | |||

| Competitive | Food Preparation Workers | **** | |

| Counter Attendants, Cafeteria, Food Concession, and Coffee Shop | **** | ||

| Cooks, Short Order | **** | ||

| Dishwashers | **** | ||

| Hosts and Hostesses, Restaurant, Lounge, and Coffee Shop | *** | ||

| Waiters and Waitresses | *** | ||

| Chefs and Head Cooks | *** | ||

| Dining Room and Cafeteria Attendants and Bartender Helpers | ** | ||

| Cooks, Private Household | * | ||

| Healthcare Practitioners and Technical | Not competitive | Dietitians and Nutritionists | * |

| Life, Physical, and Social Science | No different | Agricultural and Food Science Technicians | |

| Conservation Scientists | |||

| Food Scientists and Technologists | |||

| Not competitive | Political Scientists | * | |

| Social Scientists and Related Workers, All Other | * | ||

| Management | Not competitive | Chief Executives | **** |

| General and Operations Managers | **** | ||

| Office and Administrative Support | No different | Bookkeeping, Accounting, and Auditing Clerks | |

| Customer Service Representatives | |||

| First-Line Supervisors of Office and Administrative Support Workers | |||

| Office and Administrative Support Workers, Other | |||

| Office Clerks, General | |||

| Production, Planning, and Expediting Clerks | |||

| Shipping, Receiving, and Inventory Clerks | |||

| Stock Clerks and Order Fillers | |||

| Not competitive | Administrative Services Managers | ** | |

| Executive Secretaries and Executive Administrative Assistants | * | ||

| Secretaries and Administrative Assistants, Except Legal, Medical, and Executive | * | ||

| Personal Care and Service | No different | Recreation Workers | |

| Tour Guides and Escorts | |||

| Ushers, Lobby Attendants, and Ticket Takers | |||

| Production | No different | Bakers | |

| Butchers and Meat Cutters | |||

| Cooling and Freezing Equipment Operators and Tenders | |||

| Extruding, Forming, Pressing, and Compacting Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders | |||

| Food and Tobacco Roasting, Baking, and Drying Machine Operators and Tenders | |||

| Food Batchmakers | |||

| Helpers—Production Workers | |||

| Meat, Poultry, and Fish Cutters and Trimmers | |||

| Production Workers, Other | |||

| Not competitive | First-Line Supervisors of Production and Operating Workers | **** | |

| Industrial Production Managers | **** | ||

| Separating, Filtering, Clarifying, Precipitating, and Still Machine Setters, Operators, and Tenders | *** | ||

| Sales and Related | No different | Advertising and Promotions Managers | |

| Demonstrators and Product Promoters | |||

| First-Line Supervisors of Retail Sales Workers | |||

| Sales Representatives, Services, Other | |||

| Sales Representatives, Wholesale and Manufacturing, Except Technical and Scientific Products | |||

| Not competitive | Sales Managers | **** | |

| Competitive | Retail Salespersons | **** | |

| Cashiers | ** | ||

| Transportation and Material Moving | No different | First-Line Supervisors of Material-Moving Machine and Vehicle Operators | |

| Packers and Packagers, Hand | |||

| Not competitive | First-Line Supervisors of Transportation and Material Moving Workers, Except Aircraft Cargo Handling Supervisors | * | |

| Transportation, Storage, and Distribution Managers | **** | ||

| Competitive | Driver/Sales Workers | *** |

Statistically significant Detailed SOCs, clustered by labor market, with at least 15 observations in each Detailed SOC

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.000

^Status signifies if the AFS distribution of wages were significantly different than the median distribution for that occupation in all other industries. “No different” means the difference in distributions were not significantly different. A statistically significant difference was categorized as competitive or not competitive, where “competitive” means AFS occupations outperformed other industries and “not-competitive” means AFS occupations underperformed

Across all Detailed SOCS, 12 AFS occupations were offered wages that were more competitive than their local labor markets. Nine of the competitive occupations were in the Food Service and Preparation Major SOC, with two in Sales and one in Transportation. Five of the 14 most common Detailed SOCs were competitive. Chefs and Head Cooks were competitive, but so were several occupations that struggled to meet living wage thresholds: Food Preparation Workers, Fast Food and Counter Workers, Short Order Cooks, and Retail Salespeople.

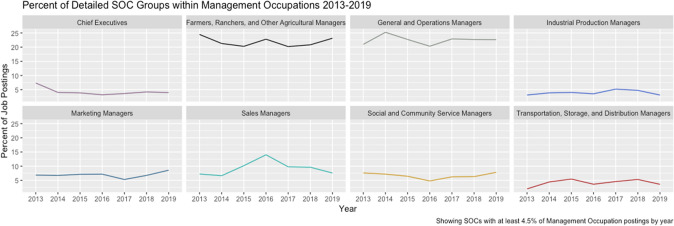

Thirty-four AFS occupations were not competitive. This category included most occupations in the Farming and Business and Financial Operations Major SOCs, all occupations within the Community and Social Service and Management Major SOCs, and a selection of occupations from the Transportation, Sales, Production, and Office and Administrative Support Major SOCs. Among the most common Detailed SOCs, Community and Social Service Specialists and Farmworkers and Laborers (Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse) were not competitive, which is consistent with their struggles to offer living wages. However, General Managers and Farmers, Ranchers and Other Agricultural Managers were less competitive than their counterparts in other industries despite offering living wages.

Fifty-one AFS occupations were no different than other industries, indicating that their wage status is likely not based on working within AFS specifically. This includes five of the most common Detailed SOCS: First-Line Supervisors in Food Preparation and Service, Restaurant Cooks, Food Service Managers, Bakers, and First-Line Supervisors in Sales.

Discussion

How does labor demand reflect the ways people build and sustain alternative food systems?

The majority of labor demand was for work directly involved in the food chain, with food service occupations comprising a particularly large proportion of labor demand (37%). While potentially reflecting high turnover, this is consistent with research documenting a large and growing proportion of job growth in food service (Grimes et al. 2019). In AFS, chef-driven restaurants may be well-suited AFS participants because chefs are comfortable using difficult to cook, expensive, or lesser-known items and have menu flexibility. Openings on farms may help farms diversify revenue streams with agritourism and secure higher prices.

AFS farms may have unique drivers for labor. Contrary to industrial farms, AFS farms were smaller (averaging 271 acres versus 444 acres for all farms nationally (United States Department of Agriculture 2020), and produced both animal and vegetable products. High demand for farmworkers is consistent with their ongoing labor shortage, which may be driven by an increase in the number of small farms19; further, AFS farming practices are labor-intensive (Weil et al. 2017; Bauman et al. 2018; United States Department of Agriculture 2020; Zahniser et al. 2018). Immigration policy also impacts AFS farms (Harrison and Getz 2015).

Consistent with research that growing in size and scale is difficult for AFS (Angioloni et al. 2016; Dunning 2016; Tewari et al. 2018), the results suggest that between 2010 and 2019, AFS was made up of many, small businesses that rely on direct-to-consumer sales, but that AFS infrastructure that may enable broader and deeper production and distribution may be developing. First, there was high demand for direct-to-consumer sales positions at specialty food and beverage stores, consumer cooperatives, and farmers markets; conversely there was fewer Wholesale Sales, Buyer and Transportation openings. High demand for General Managers at food hubs, farm-to institution programs, and cooperative associations that are designed to build AFS infrastructure suggests growth in fledgling AFS enterprises and a need for someone to take on leadership responsibilities that a founder can no longer handle themselves. Supporting this is the small but substantial labor demand for Production occupations that may enable scale by adding value and extending the shelf-life of goods. Finally, demand for Business and Financial Operations, Office and Administrative Support reflects business' need to build out support services with growth. Building AFS is still underway with ample room to build on existing efforts as well as identify new possibilities. As the COVID-19 pandemic showed, when the rigidity of larger supply chains broke down, many novel AFS arrangements emerged to connect farmers without markets to consumers without food, like allowing small farms to donate or sell food to schools despite not having government contracts.

One important area of development for AFS was within Community and Social Service organizations, and Community Social Service Specialists in particular. The loci of this work—community health and economic vitality, sustainable farming, and policy advocacy—reflect long-term challenges for the food system that are often the inspiration for AFS work. Future research should investigate how non-profit and community engaged work may be influencing AFS development.

Is job quality as a barrier to equitable AFS development?

This paper examined two metrics of job quality in AFS. The first examined whether advertised wages in AFS job openings met or exceeded county-level living wage standards for a single person—the most generous possible calculation of a living wage. At a national level, another living wage comparison is not available. However, one case study by the Seattle Regional Food Policy Council found that only 20% of non-farm food system workers earn a living wage, meaning that AFS living wage attainment rates in this paper pose a significant improvement compared to non-AFS work (Regional Food Policy Council and University of Washington 2011). The second metric was whether the wages were competitive compared to the median income for that occupation and labor market. At the Detailed SOC level, the results were mixed on this metric, especially in light of living wage attainment rates: few jobs were both competitive and met living wage thresholds.

Higher prices for AFS products may have translated into increased wages for occupation categories closest to consumers: food service and sales. In the Food Preparation and Serving Major SOC, AFS wages for entry-level and senior positions were competitive, suggesting AFS-specific wage increases for workers across the career ladder. In contrast, wages in AFS occupations in sales reflect a more equitable distribution of compensation, where entry-level roles are offered competitive wages, their supervisors are offered wages consistent with other industries, and their managers are offered not competitive (but still high) wages. One reason may be that “locally sourced” products have higher prices, which is consistent with evidence that consumers express a higher willingness to pay for locally branded foods (Thilmany et al. 2008). Restaurants further benefit from higher consumer prices and profit margins compared to retail settings (Jayaraman 2014; The Food Industry Association 2021).

However, if higher consumer prices supported competitive wages in food service and sales settings, it has not spurred competitive wages across AFS, and it has not consistently shifted wage compensation above living wages for the small subset of competitive entry-level roles. A reliance on individual consumption patterns will not lead to wage enhancement across the food system. All competitive entry-level roles in the Food Preparation and Service Major SOC were offered living wages less than 50% of the time, with negative median and average differences between offered wages and living wage thresholds. Competitive entry-level sales roles were offered living wages between 25% (cashiers) and 62% of the time (delivery/sales workers); 41% of retail salespersons were offered living wages.

The challenge of relying on higher prices to raise wages is starkly depicted when considering AFS farming occupations. AFS Farmworker and Laborer (Crop, Nursery, and Greenhouse) wages increased faster than inflation, from $10.41 per hour in 2011 to $13.25 per hour in 2019 (2020-dollar values), likely as a result of increased demand nationally for these positions (Zahniser et al. 2018). Despite this, AFS farmworkers underperformed compared to their labor markets and frequently did not earn a living wage. Given the current proportion of a consumer food dollar that reaches farmworkers, consumer food prices would need to increase dramatically for farmworkers to see a substantial wage increase without additional policy supports. Costa and Martin (2020) found that farmworkers earn just $0.10 for every food dollar spent in the United States “even though most, and in some cases all, of the work it takes to prepare fresh fruits and vegetables for retail sale takes place on farms.” If AFS farmworkers receive a similar proportion, too little of our food dollars reach farmworkers for a price support alone to fix the structural job quality issues in the food system.20 Because AFS farming is more labor intensive and relies on skilled workers, the problem is more pronounced: a failure to provide competitive and living wages that maintain the labor pool poses a structural barrier to equity and AFS development.

These results provide an important, but perhaps overly optimistic, snapshot into working conditions on small farms, which “remain one of the most understudied groups, especially as compared to how much time and attention is spent studying farm business owners” (Arcury & Quandt 2009, p. 147). Migrant labor, unpaid family labor, and internship labor are common on AFS farms, operate under unfavorable labor conditions (Rissing et al. 2021; Biewener 2016; Arcury and Quandt 2009), and are not included in this analysis. However, uncompetitive AFS wages are consistent with literature showing larger (often industrial) farms providing (relatively) higher wages, benefits, and safer working conditions for “on the books” roles in order to follow labor regulations (Lo and Delwiche 2016).21 Indeed, non-family workers on small farms experience limited legal protections (Gray 2013). In sum, relying on higher prices for AFS goods deepens a reliance on white, educated, middle-class consumers with the resources to “vote with their forks,” and further ignores working conditions and worker power, especially for workers of color who are more likely to hold underpaid jobs in the food system (McClintock 2013; Food Chain Workers Alliance and Solidarity Research Cooperative 2016; Harrison and Getz 2015).

Further, the specter of subsidizing wages with “psychic incomes” raises the question of whether white, middle-class consumer values are bleeding into AFS development work more broadly, by creating differential access to participate in AFS development. If AFS are already biased toward white, middle-class values, people who espouse those values are more likely to get a high “psychic income” from participating; they are also more likely to be able to accept a job offering uncompetitive wages. Poor job quality presents a structural barrier to AFS development and growth by deterring job seekers from applying to AFS jobs and by creating bias in who is able (and willing) to pursue a career in AFS. This challenge intensifies in the context of careers—senior roles like chief Executives, managers,22 and several first-line supervisor occupations23 were not competitive. In addition, many managerial positions are barely above living wages for a single person without children. These positions do not provide financial sustainability for individuals in the long term, especially those interested in building families. Future research should examine how social and community organizations may deepen or combat this potential risk. Community and Social Services programming is often provided non-profits with strong social missions that may rely significantly on the prospect of psychic incomes. The non-profit space has long histories of being populated by white women who have on the one hand been left out of other, higher-paying workplaces, and on the other hand have upheld racial barriers to entry (Odendahl and O'Neill 1994). The intersection of jobs offering psychic incomes and inequality in this space may be important for understanding how to overcome barriers preventing equitable AFS development.

Policy and practice recommendations

AFS jobs struggle to meet living wage thresholds and to be competitive with jobs in other industries. Policy intervention is needed to bolster job quality if AFS are to live up to their potential. Fischer-Daly (2021) and others have shown that labor organizing in the food system can successfully link economic and food justice (Fischer-Daly 2021; Myers and Sbicca 2015; Minkoff-Zern 2014). These efforts demonstrate the importance of building worker power in the food system, which can push beyond a middle-class consumer model of social change.

However, consumers and institutions can support worker power by supporting workplace justice, union drives, and pro-worker legislation. Institutions should commit to not only buying more AFS products, allowing AFS firms to more quickly grow, but also to integrate wage quality standards into their partnership expectations. Policy programs at the local level have been successful in supporting this. For example, the Good Food Purchasing program provides transparency and requires commitments to sustainability and labor equity in its sourcing programs (Lo and Delwiche 2016).

Finally, efforts to shift the food system must also engage local, state, and federal policy makers. Extending labor protections and wage standards that most American workers already enjoy by removing farmworker exemptions is an essential first step (Lester 2020; Grimes et al. 2019; Rodman et al. 2016). Worker protections and supports should include: minimum wage raises indexed to inflation, unemployment insurance, overtime pay, paid sick leave, mandated and paid rest periods for farm workers (including meal times); improved workplace health and safety standards, and an abolished tipped minimum wages in food service. Labor protection laws already on the books, such as the right to organize and anti-wage theft laws, should be better enforced (Food Chain Workers Alliance and Solidarity Research Cooperative 2016). For future policy formation and feedback processes, stakeholders beyond middle-class consumers and farmers must be actively and equitably recruited to participate, particularly farm workers. Several groups, such as the Food Justice Certification Project provides an example of public consultation processes (Food Justice Certification 2022).

AFS firms can elect to prioritize worker wages as a business strategy. Occupation structures that recognize worker skill and organize work around supporting skill see better worker wages and better productivity. Further, increasing minimum wages has not been shown to decrease jobs in the restaurant sector (Lester 2020; Forsythe 2019; Lowe 2021). Policy supports to bolster these efforts might include enforcing anti-trust laws for industrial agriculture and shifting subsidies away from industrial agriculture will improve AFS' competitive advantage by combatting food system consolidation (Clapp 2019; Graddy-Lovelace and Naylor 2021).

Limitations

Who decides to post which job opening may introduce bias into this dataset. It seems likely that difficult to fill jobs are more likely to be posted on a national website, which costs money to advertise, than an easily-filled job through the local community. Difficult-to-fill jobs may require specific skill sets, have unique requirements (such as living on a farm), require living in rural areas, or they may be underpaid.

They may even be underpaid precisely because firms are strategically relying on a psychic income to lower real wages. Future research should be to look into whether or how this bias may also be targeting certain demographics, such as women, or people of color, that may be more inclined to accept a lower paid job. The website was created by two well-educated white women, and this may have impacted how jobs are selected for publication or how they are advertised. However, and conversely, the website does screen for job quality, meaning even worse jobs may not have been posted. A final possible bias is that there were fewer posts from early years of website development.

The wage information in this dataset is limited in a few ways. First, only 39% of job openings provided wage information. The data does not include wages for business owners, including farm owners, nor does it reflect unpaid labor, which is common on small farms. Finally, undocumented workers are common on small farms, and exempt from many labor protections and data reporting mechanisms (Costa and Martin 2020; Harrison and Getz 2015). Because of these trends, the farm labor patterns shown here are optimistic. Despite this, no other national datasets on labor in AFS exist; therefore, this data offers a valuable snapshot into work in this space: limiting wage transparency is a mechanism for preventing labor market arbitrage to the disadvantage of workers. A second limitation is that the wages analyzed are for job advertisements and have not necessarily been filled or filled at that compensation level. It was not possible to observe negotiations that take place through the hiring process. These job advertisements are compared to actual wages of workers in OES data, so this comparison is not exact.

The living wage analyses are conservative, as living wages are calculated for a single person without children and would not be enough to sustain families. However, this strengthens the argument that AFS jobs struggle to offer true living wages.

Lastly, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test uses median hourly wages for each labor market. When using a paired differences test, the median hourly wages value is repeated within each local labor market for a given year. Thus, although the comparison of wages accounts for local labor market conditions, the labor markets are not independent clusters. This bias is less significant in the context of this research problem because independent clustering is typically a problem when only selected clusters are used to generalize to a much larger population. Here, all clusters with fifteen observations are used, so the results are not generalized to other clusters.

Conclusion

There is limited data on labor in AFS, despite several case studies identifying job quality as an issue. This paper narrows this gap by assessing labor demand between 2010 and 2019 and job quality by analyzing living wage attainment rates and local labor market competitiveness.

A wide range of occupations are in demand in AFS, reflecting the myriad ways AFS are already being built. Most jobs are directly engaged in food systems work, though business and support occupations are involved. Labor demand reflects many small firms engaged in direct-to-consumer oriented projects, but with increasing activity in the infrastructure development for AFS to grow. Social and community service-oriented work is an important area of AFS development warranting further study.

In considering living wage tests and local labor market competitiveness together, the potential for high job quality in AFS is mixed. Entry-level jobs in food service and retail have a higher floor in AFS compared to the same jobs in other industries. Both entry and senior-level positions in AFS Food Service occupations perform better than their counterparts in other industries, while AFS Sales occupations display signs of wage compression. However, these gains should not be overstated, as they are limited to a few roles and have wage levels that are not substantially higher than the base living wage. Reliance on higher prices for AFS in food service and retail jobs to anchor higher wages does not extend across food chain workers, and poses concerns about whether AFS currently caters too much to high-income customers and individual behavior change without attending to structural deficiencies in the current food system.

For many other important occupations in farming, food production, community and social service, and management, AFS wages underperform based on living wage and competitive metrics. This includes higher-level management occupations, suggesting that careers in AFS development may also cater to wealthier privileged individuals interested in a “psychic income.” This likely biases who participates, how they participate, and increases the risk that AFS development will replicate inequitable blind spots present in our current food system.

AFS growth is needed to move toward an environmentally secure future. However, the ability to grow and expand this industry should not come at the expense of economic equity. Low wages may undermine industry performance and innovation by creating untenable working conditions and livelihoods. In addition to policies enhancing wages and labor protections, funders and community groups engaged in sustainability in AFS must become advocates (and made accountable) to raising wage standards and working conditions.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Dorothy Neagle and Taylor Cocalis for sharing the Good Food Jobs data and their enthusiasm for this research. I also want to thank Bill Lester, Nichola Lowe, Nikhil Kaza, Gabriel Cumming, and Andrew Whittemore for their encouragement and suggestions. The paper also benefitted from generous feedback from three anonymous reviewers.

Abbreviations

- AFS

Alternative food systems

- BLS

Bureau of Labor Statistics

- MSA

Metropolitan Statistical Area

- NASS

National Agricultural Statistics Service

- NIOCCS

NIOSH Industry and Occupation Computerized Coding System

- NIOSH

U.S. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

- O*NET

Occupational Information Network

- OES

Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics

- SOC

Standard Occupation Code

- TLD

Total labor demand

- USDA

United States Department of Agriculture

Sophie Kelmenson

is a Postdoctoral Fellow in City and Regional Planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research and publications focus on equity and sustainability, often in the context of food systems.

Appendix

Distribution of Manager Detailed SOCs to the Major SOC groups they manage

See Table 6.

Table 6.

Distribution of Manager Detailed SOCs to the Major SOC groups they manage

| Managerial Detailed SOC name | Managerial Detailed SOC | Number | Major SOC Group managed | Major SOC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public Relations Managers | 11-2032 | 181 | Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media Occupations | 27-0000 |

| Facilities Managers | 11-3013 | 13 | Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations | 37-0000 |

| Property, Real Estate, and Community Association Managers | 11-9141 | 13 | Building and Grounds Cleaning and Maintenance Occupations | 37-0000 |

| Marketing Managers | 11-2021 | 573 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Fundraising Managers | 11-2033 | 208 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Financial Managers | 11-3031 | 132 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Human Resources Managers | 11-3121 | 92 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Purchasing Managers | 11-3061 | 72 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Training and Development Managers | 11-3131 | 11 | Business and Financial Operations Occupations | 13-0000 |

| Social and Community Service Managers | 11-9151 | 644 | Community and Social Service Occupations | 21-0000 |

| Computer and Information Systems Managers | 11-3021 | 26 | Computer and Mathematical Occupations | 15-0000 |

| Education Administrators, Postsecondary | 11-9033 | 26 | Educational Instruction and Library Occupations | 25-0000 |

| Education Administrators, Kindergarten through Secondary | 11-9032 | 11 | Educational Instruction and Library Occupations | 25-0000 |

| Farmers, Ranchers, and Other Agricultural Managers | 11-9013 | 1844 | Farming, Fishing, and Forestry Occupations | 45-0000 |

| Food Service Managers | 11-9051 | 1243 | Food Preparation and Serving Related Occupations | 35-0000 |

| Administrative Services Managers | 11-3012 | 174 | Office and Administrative Support Occupations | 43-0000 |

| Personal Service Managers, All Other | 11-9179 | 11 | Personal Care and Service Occupations | 39-0000 |

| Industrial Production Managers | 11-3051 | 368 | Production Occupations | 51-0000 |

| Sales Managers | 11-2022 | 764 | Sales and Related Occupations | 41-0000 |

| Advertising and Promotions Managers | 11-2011 | 41 | Sales and Related Occupations | 41-0000 |

| Transportation, Storage, and Distribution Managers | 11-3071 | 373 | Transportation and Material Moving Occupations | 53-0000 |

| General and Operations Managers | 11-1021 | 1058 | * | 11-0000 |

| Chief Executives | 11-1011 | 386 | * | 11-0000 |

This table presents managers with the Major SOC Group they manage, i.e. Food Service Managers will be presented with the Major SOC Group Food Preparation and Service Occupations, even though Food Service Managers are a Detailed SOC within the Manager Major SOC.

Job postings over time

Fig. 5.

AFS job postings by Major SOC Group by year

Fig. 6.

AFS Manager Postings by year and Major SOC Group 2011–2019

Kolmogorov–Sminov test

See Table 7.

Table 7.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov one-sample test results

| Variable | Test results |

|---|---|

| Hourly | D = 0.99661, p-value < 0.001 |

| Log(hourly) | D = 0.95154, p-value < 0.001 |

| Hourly-median | D = 0.44378, p-value < 0.001 |

| Hourly-mean | D = 0.50631, p-value < 0.001 |

| Log median diff | D = 0.26188, p-value < 0.001 |

| Log mean diff | D = 0.29021, p-value < 0.001 |

A nonparametric test was selected because the differences between AFS hourly compensation and median hourly compensation did not follow a normal distribution, despite several possible transformations, according to the results of a Kolmogorov–Smirnov one-sample test (two-sided, DF = 15,088, p = 0.001). A nonparametric test is needed because hourly wages, as well as differences between hourly wages and comparison groups, did not follow normal distributions. Their logarithmic transformations did not follow normal distributions either. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality was not used because of the sample size constraints for that test.

Labor markets

See Table 8.

Table 8.

Labor markets

| Labor market | Jobs | State(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Anchorage, AK | 11 | AK |

| Alaska nonmetropolitan area | 7 | AK |

| Balance of Alaska nonmetropolitan area aka Railbelt/Southwest Alaska nonmetropolitan area | 3 | AK |

| Southeast Alaska nonmetropolitan area | 2 | AK |

| Fairbanks, AK | 1 | AK |

| Birmingham–Hoover, AL | 61 | AL |

| Tuscaloosa, AL | 25 | AL |

| Montgomery, AL | 5 | AL |

| Huntsville, AL | 3 | AL |

| Northeast Alabama nonmetropolitan area | 3 | AL |

| Northwest Alabama nonmetropolitan area | 2 | AL |

| Southwest Alabama nonmetropolitan area | 2 | AL |

| Auburn–Opelika, AL | 1 | AL |

| Decatur, AL | 1 | AL |

| Dothan, AL | 1 | AL |

| Florence–Muscle Shoals, AL | 1 | AL |

| Memphis, TN–MS–AR | 35 | AR, MS, TN |

| Fayetteville–Springdale–Rogers, AR–MO | 30 | AR |

| Little Rock–North Little Rock–Conway, AR | 13 | AR |

| Springfield, MO | 9 | MO |

| Fort Smith, AR–OK | 7 | AR, OK |

| Central Arkansas nonmetropolitan area aka North Arkansas nonmetropolitan area | 6 | AR |

| East Arkansas nonmetropolitan area | 5 | AR |

| South Arkansas nonmetropolitan area | 1 | AR |

| Phoenix–Mesa–Glendale, AZ aka Phoenix–Mesa–Scottsdale, AZ | 74 | AZ |

| Tucson, AZ | 19 | AZ |

| Prescott, AZ | 7 | AZ |

| Flagstaff, AZ | 5 | AZ |

| Southeast Arizona nonmetropolitan area | 3 | AZ |

| Arizona nonmetropolitan area | 2 | AZ |

| San Francisco–Oakland–Hayward, CA | 3945 | CA |

| Los Angeles–Long Beach–Anaheim, CA | 1011 | CA |

| Santa Rosa–Petaluma, CA aka Santa Rosa, CA | 405 | CA |

| San Jose–Sunnyvale–Santa Clara, CA | 289 | CA |

| San Diego–Carlsbad–San Marcos, CA aka San Diego–Carlsbad, CA | 151 | CA |

| Santa Cruz–Watsonville, CA | 146 | CA |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA aka Sacramento–Roseville–Arden-Arcade, CA | 129 | CA |

| North Coast Region of California nonmetropolitan area | 121 | CA |

| Napa, CA | 119 | CA |

| Salinas, CA | 83 | CA |

| Northern Mountains Region of California nonmetropolitan area | 39 | CA |

| Oxnard–Thousand Oaks–Ventura, CA | 39 | CA |

| Santa Barbara–Santa Maria–Goleta, CA aka Santa Maria–Santa Barbara, CA | 39 | CA |

| Riverside–San Bernardino–Ontario, CA | 17 | CA |

| Chico, CA | 15 | CA |

| North Valley Region of California nonmetropolitan area aka North Valley–Northern Mountains Region of California nonmetropolitan area | 15 | CA |

| Vallejo–Fairfield, CA | 13 | CA |

| Fresno, CA | 11 | CA |

| Bakersfield–Delano, CA aka Bakersfield, CA | 9 | CA |

| San Luis Obispo–Paso Robles–Arroyo Grande, CA aka San Luis Obispo–Paso Robles, CA | 9 | CA |

| Eastern Sierra Region of California nonmetropolitan area aka Eastern Sierra–Mother Lode Region of California nonmetropolitan area aka Mother Lode Region of California nonmetropolitan area | 7 | CA |

| Yuba City, CA | 3 | CA |

| Stockton–Lodi, CA | 2 | CA |

| El Centro, CA | 1 | CA |

| Modesto, CA | 1 | CA |

| Visalia–Porterville, CA | 1 | CA |

| Denver–Aurora–Broomfield, CO aka Denver–Aurora–Lakewood, CO | 254 | CO |

| Boulder, CO | 163 | CO |

| Southwest Colorado nonmetropolitan area aka Western Colorado nonmetropolitan area | 58 | CO |

| North Central Colorado nonmetropolitan area aka Northwest Colorado nonmetropolitan area | 30 | CO |

| Fort Collins–Loveland, CO aka Fort Collins, CO | 22 | CO |

| Eastern and Southern Colorado nonmetropolitan area | 13 | CO |

| Colorado Springs, CO | 4 | CO |

| Greeley, CO | 4 | CO |

| Central Colorado nonmetropolitan area | 1 | CO |

| Grand Junction, CO | 1 | CO |

| Bridgeport–Stamford–Norwalk, CT | 232 | CT |

| Connecticut nonmetropolitan area aka Northwestern Connecticut nonmetropolitan area | 130 | CT |

| Worcester, MA–CT | 92 | CT, MA |

| Capital/Northern New York nonmetropolitan area | 80 | CT, NY |

| Hartford–West Hartford–East Hartford, CT | 79 | CT |

| New Haven, CT | 68 | CT, NY |

| Norwich–New London–Westerly, CT–RI aka Norwich-New London, CT–RI | 57 | CT, RI |

| Eastern Connecticut nonmetropolitan area | 1 | CT |

| Salisbury, MD aka Salisbury, MD–DE | 8 | DE, MD |

| Sussex County, Delaware nonmetropolitan area | 2 | DE |

| Dover, DE | 1 | DE |

| Miami–Fort Lauderdale–West Palm Beach, FL aka Miami–Fort Lauderdale–Pompano Beach, FL | 72 | FL |

| North Port–Bradenton–Sarasota, FL aka North Port–Sarasota–Bradenton, FL | 21 | FL |

| Gainesville, FL | 16 | FL |

| Tampa–St. Petersburg–Clearwater, FL | 13 | FL |