Abstract

Rent-seeking behavior is when individuals or firms acquire above-market returns by exercising economic and political power. We introduce an active-learning exercise, with discussion questions and extensions, to illustrate implications of rent seeking for efficiency, equity, economic justice, and democracy. Students act as corporate decision makers allocating resources among physical, financial, and political investment. Instructors use the results to highlight distinctions between productive and nonproductive activities, and ways in which individual firm incentives may differ from socially optimal firm behavior. This allows for discussions of broader issues, such as how rent seeking can undermine democratic ideals and perpetuate inequality.

Keywords: Rent seeking, Lobbying, Inequality, Pedagogy

Introduction

Rent-seeking behavior is when individuals or firms acquire above-market returns through the exercise of economic and political power. With the rise of winner-take-all markets and politics (Hacker and Pierson 2011), superstar firms (Autor et al 2020), and a changing institutional structure that favors capital at the expense of labor (Cauvel and Pacitti 2022; Levy and Temin 2007), rent seeking is becoming increasingly central to explaining economic and political dynamics (CORE 2022; Bowles and Carlin 2020).

More broadly, understanding the causes and effects of rent-seeking behavior helps fill the gap between economics and politics. The use of economic power—control over rents and affecting a preferred distribution of income—can be used to acquire political power through lobbying and campaign contributions, which leads to favorable policies that further increase economic power. In the run-up to the 2008 financial crisis, this investment in politics helps explain the rise and fall of large financial institutions, which is argued to be the result of a decades-long process of rent-seeking behavior, leading to deregulated markets, in addition to ideological and regulatory capture (Johnson and Kwak 2010). Furthermore, the degree to which financial firms lobbied positively affected the probability of receiving government bailouts (Igan et al. 2011). The Payroll Protection Program, part of the fiscal policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic, was designed to provide forgivable loans to incentivize firms in retaining workers. However, this program was regressive in nature, as the top quintile of households received approximately 75% of its benefits (Autor et al 2022).

Given the central importance of rent seeking for understanding modern economies, it is a valuable topic for instructors to introduce to students. However, it can also be difficult to grasp. As such, active learning tools may be a useful way to help students better understand rent-seeking behavior. Active learning methods have a variety of benefits, including increasing student engagement and participation, requiring students to solve problems and think critically about issues, and presenting opportunities for students to collaborate. There is considerable evidence that active learning methods typically lead to better educational outcomes (Dorestani 2005; Freeman et al. 2014; Salemi 2002; Sheridan and Smith 2020; Tila 2021).

There has already been interest in developing classroom exercises to help students understand rent seeking. Goeree and Holt (1999) initially developed an exercise in which students act as firms competing to gain a telephone license, or other prize awarded by the government, in a lottery-style system where teams have the opportunity to purchase up to 13 applications. Comparing the total application costs across teams to the value of the license provides a stark illustration of the social cost of rent seeking. Bischoff and Hofmann (2002) suggested an extension in which students fill out an in-game questionnaire to provide insights into their decision-making processes, along with minor tweaks to the parameters of the exercise. Strow and Strow (2006) further built upon this work, suggesting a modified version of the exercise in which a real monetary reward is distributed based on the results of a one-round all-pay auction in which students bid their own money. Hall et al. (2019) summarize the economics education literature on rent seeking, including these three exercises, and treatment of the topic in public economics textbooks. Roush and Johnson (2018) modify the Goeree and Holt (1999) exercise by translating it to the context of recruiting in college athletics and adding a new mechanic in which players can pay bribes, but risk punishment if they do so.

Although the existing literature provides a number of exercises to introduce students to the concept of rent seeking, they focus on only one aspect—its inefficiency. We build on the existing literature by arguing that rent seeking also has important implications for equity, economic justice, and democracy. Our objective is to highlight how rent-seeking behavior affects the interactions between firms, markets, and the government, and their joint effects on economic outcomes; and to engage students in discussions about the efficiency of productive and nonproductive activities, as well as the broader issues mentioned above. We view our primary contribution as offering an exercise that can be easily used to introduce students to critical real-world implications of rent seeking across a variety of important outcomes of interest, including, but not limited to, efficiency. Although the exercise was initially developed in line with the approach presented in the textbook by Bowles et al. (2018), it does not require the use of any particular textbook or any specific prior knowledge for students.

Although rent seeking can take many forms, some of which may be socially beneficial (such as a patent race), the exercise we present focuses on the use of political power. Students act as corporate decision makers, allocating firms’ resources among physical, financial, and political investment, competing with one another to earn the highest total return over a five-round game. Instructors then use the results to highlight the distinction between firm activities that are socially beneficial—leading to increased efficiency, output growth, and employment—and those that are not productive. The ways in which individual firm incentives may differ from socially optimal firm behavior can also be emphasized. Like the other classroom exercises on rent seeking summarized above, our exercise provides a striking illustration of the inefficiency of rent seeking by highlighting the social opportunity cost. However, our exercise is designed to encourage students to also consider outcomes through lenses of equity and democracy. This provides an opportunity to engage students in discussions of broader issues, such as the ways in which rent seeking can undermine democratic ideals and perpetuate inequality. Moreover, our exercise also shows that certain types of financial activities can have the same opportunity cost as rent seeking, providing a useful entry point for discussion of issues related to shareholder primacy and financialization.

Below, we discuss the mechanics of the exercise, along with a menu of discussion questions and potential extensions of the game, which are designed to highlight the social and political ramifications of rent seeking, in addition to efficiency issues.

Exercise Mechanics

The exercise takes the form of a game, which we generically and intentionally call the “Chief Executive Game.” Although we considered more descriptive names that highlight the purpose of the exercise (“The Rent-Seeking Game”), we did not want the title to influence students’ decisions in the game itself. As the name suggests, students take on the role of a firm’s CEO, competing with one another to see who can earn the highest return by the end of the five-round game. Instructors can choose to incentivize students by giving a reward to the winning student, or having them play with their own money as Strow and Strow (2006) suggest. However, we have found that students are sufficiently engaged and compete strategically even when no prize is offered.

Students are broken into teams, with each team representing an individual corporation. Although we use the term “teams” for convenience, students can compete individually or in groups, depending on the class size. In our experience, 8–12 teams are ideal, as this generates sufficient variation in strategy and competition for rents while limiting the amount of time that needs to be spent by the instructor tracking students’ choices and the resulting outcomes.

The goal for each team is to have the highest possible stock price for their corporation at the end of five rounds. In each round, students must allocate a budget across three types of activities:

Physical investment, which acts as a proxy for efforts by firms to increase productive capacity, improve productivity, or develop new products (purchasing physical capital or undertaking research and development).

Stock buybacks, which directly increase a company’s stock price and can serve as a proxy for other types of financial activity unrelated to the firm’s production.

Rent-seeking activities, which are lobbying efforts and political investment to gain a favorable government contract or policy (tax cuts, trade protection, price floors, barriers to entry in their industry, or non-enforcement of antitrust law).

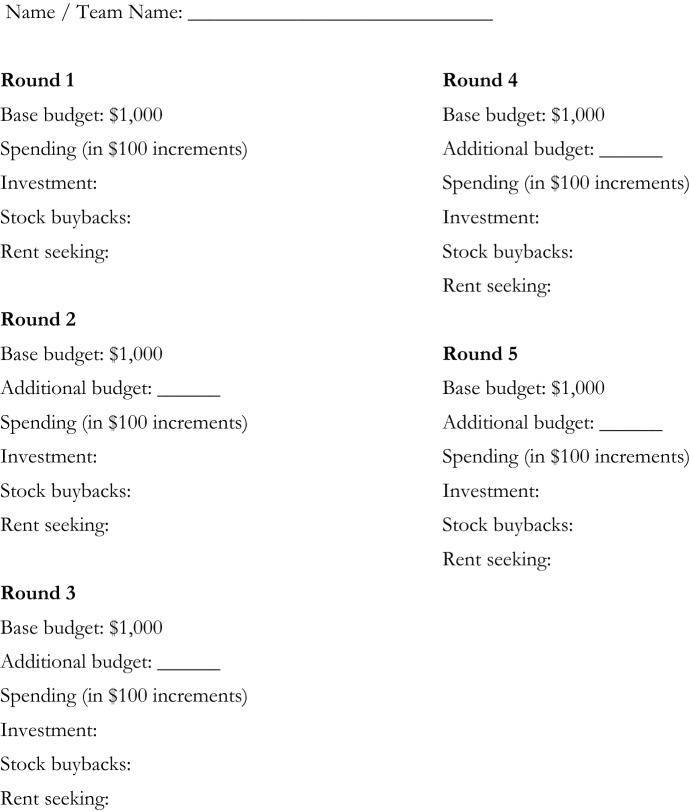

Students have a baseline budget of $1000 in each round, but they can earn additional funds to spend in some cases, described below. To simplify choices for students and make computation easier, funds can only be spent in $100 increments (unless students have $50 remaining in their budget, in which case they can spend the extra amount).

Each firm’s share price begins at a baseline of 100 points and increases if the firm successfully completes an investment project, uses funds to repurchase its own stock, or wins a rent from the government. The payoffs of each activity are as follows:

Physical investment increases the firm’s stock price by 35 points for each $100 spent in three separate rounds. If a team spends $100 on physical investment in Round 1, Round 2, and Round 3, their stock price would increase by 35 points after Round 3. To simplify the accounting done by the instructor, we don’t allow students to increase spending on an investment project after it has already begun. Teams also receive additional funds to spend in the following round—$0.50 for each dollar invested in three successive rounds. For example, if $100 is invested in the first three rounds, this firm receives an additional $50 to spend in the fourth round.1

Stock buybacks increase the stock price by 10 in the following round for each $100 spent.

Rent-seeking activities function as an auction, as in Strow and Strow (2006), in which the government rewards the highest bidder. The team that spends the most on rent seeking in a given round gains a 110-point increase in their stock price and an additional $500 to spend in the following round.2 However, only one team can win the rent-seeking policy in each round. In the event that two or more teams spend the same amount on rent seeking in a given round, the winner is chosen randomly.3

The stock price mechanic is obviously an abstraction, and we do not pretend that the activity perfectly describes the relationships among firm activities, their revenue and budgets, and stock market outcomes. However, using stock prices as the outcome of interest serves two purposes. First, it greatly simplifies the execution of the activity. We initially experimented with a game in which payoffs were monetary and directly tied to each team’s budget for the following round. However, we found that this led to additional complications in the execution of the game both for students, who had to do arithmetic between each round to determine their budget and decide how to spend fractions of a dollar; and for instructors, who were faced with more difficult accounting to track the outcomes of the game. Creating an outcome variable separate from the budget simplified things considerably. The second benefit is pedagogical. Bringing stock prices into the game creates a natural opening for discussions of shareholder primacy, financialization, short-term and long-term investment decisions and differences, and the incentives of corporate decision-makers, many of whom are incentivized through stock options to maximize share prices. Instructors who are not interested in bringing discussion of financialization into class could run a simplified version of the exercise excluding the stock buyback option. However, in our experience simplifying the game too much reduces student engagement and makes the lessons too transparent.

The payoffs can be flexible but should be based on a few important considerations. First, the reward for successful rent seeking is large. Incentivizing students to undertake rent seeking efforts is necessary to illustrate one of the central lessons of the activity: the large social and economic opportunity costs of rent seeking. The more funds students allocate to this option, the more this point is emphasized. Second, by gaining an additional $500 in their budget, the team that wins the first rent is able to outbid any other team to secure the rent in Rounds 2 and 3 (following Round 3 a team that spent $1000 on physical investment in the first three rounds will have the same budget). This illustrates how individuals or firms can gain an inside track through rent seeking to maintain power and competitive advantages in markets without adding to the economy’s productive capacity. It also demonstrates how those with more financial resources are most likely to benefit from rent seeking.

The payoffs are also designed such that there is not necessarily a dominant strategy. A team that spends its full budget on physical investment in the first three rounds will have a stock price of 450 following Round 3. Successfully winning rents in the first three rounds leads to a minimum stock price of 430 following Round 3, with additional funds that could be spent on stock buybacks or physical investment. While the team that wins the rent in the first three rounds is likely to be in the lead following Round 3, going all in on rent seeking in Round 1 is not necessarily an optimal strategy because there is risk involved; a team that spends $1000 on rent seeking in Round 1 could end up with nothing if another team does the same. Thus, there are two viable paths to success through the first three rounds of the game, one involving risk and the other requiring patience: allocating the full budget to lobbying or to physical investment. Reflection on these two strategies highlights how both of these activities can be privately beneficial for firms, but where only one is socially beneficial (increasing the productive capacity of the economy) and the other socially costly (allocating funds away from activities that increase productive capacity). Following Round 3, teams following these two strategies would have the same budget, and no one team is guaranteed to be able to outbid any other for the rent. This keeps the game competitive to ensure students remain engaged.

The instructor begins the exercise by explaining the setup of the game and then giving teams time to think over and discuss (if working in groups) their overall strategy and allocate their budget for Round 1. During this time, the instructor should talk individually with each team to answer questions and make sure they understand all parameters of the exercise. In our experience, this also ensures that every student is engaged in the exercise and has the opportunity to ask clarifying or strategic questions. The instructor should refrain from telling students which strategy to pursue. However, it is helpful to gauge students’ thoughts to make sure that they fully understand the choices and tradeoffs. In our experience, this is typically enough to generate a diverse set of strategies among teams. We have found that some teams allocate all of their budget to rent seeking, others allocate all of their budget to physical investment, and some diversify. Once students make their choices for Round 1, they write them on a piece of paper before sharing them with the class. This prevents teams from changing strategies once they begin to hear what others are doing. The instructor then announces the winner of the rent and records the budget allocations in an automated spreadsheet that calculates budgets and stock prices based on students’ choices.4 Instructors can ask students to monitor and verify the spreadsheet entries to prevent mistakes. This process is repeated for the remaining rounds, typically with less discussion and strategizing required between each subsequent round until the game is over.

Following the conclusion of the game, the instructor can show students the total amounts spent on physical investment, stock buybacks, and rent seeking. This illustration of the opportunity cost of both rent seeking and stock buybacks can serve as an entry point for discussions about the private incentives and social consequences of these different activities. Therefore, our exercise provides the same illustration of rent-seeking behavior’s social inefficiency as in Goeree and Holt (1999) and the various exercises extending it. However, ours has the added benefit of providing a clearly defined social opportunity cost, as the funds spent on rent seeking and stock buybacks represent foregone physical investment, not just lower resulting funds for firms.

The game takes approximately 30 minutes to complete. The remaining class time can be used to run additional variations of the game or to reflect on the game and discuss the implications of rent seeking and stock buybacks. This discussion can take a number of different directions depending on time constraints, students’ interests, and the goals of the instructor. Various options for discussion are outlined in the following section.

Discussion and Extensions

This exercise can be useful in any course wherein the instructor wants to discuss the economics of rent seeking, financialization, or both. A basic understanding of fundamental economic concepts, such as opportunity cost and economic decision making, is useful for framing the discussion, but beyond this the activity requires little in the way of prior knowledge to be effective. As such, the exercise can be used in introductory economics courses, even towards the beginning.5 The focus on firm-level decisions makes the activity a natural fit in a microeconomics course, but the discussion can easily be tailored to highlight aggregate outcomes for a macroeconomics class as well. Given the usefulness of rent seeking and lobbying in explaining many economic outcomes, and the role of policy discussions, there are many other contexts in which the activity could be applicable: to highlight the issues associated with lobbying and political investment in a political economy or public economics courses, to give context to discussions of financial regulation in a money and banking class, or to frame discussion of trade negotiations in an international economics class. Rent seeking also has important implications for the environment (MacKenzie 2017) and gender inequality (Braunstein 2008) that instructors can highlight, either in introductory courses or courses that are more focused on those issues.

Because there are many forms a discussion on these issues could take depending on the context, we do not offer a single outline for instructors to follow. Instead, we offer a menu of sufficiently broad themes that instructors can use to meet their goals, along with discussion questions for each. Below is a list of questions we have had students consider, but we encourage professors to tailor the questions to their own objectives and interests.

Social Costs and Benefits

Consider the amount that was spent on rent seeking and stock buybacks in the game. Is this a socially desirable or economically efficient outcome? Why or why not?

What are the social benefits of physical investment? What about stock buybacks and rent seeking?

What is the opportunity cost of rent seeking and stock buybacks?

How do incentives for CEOs, shareholders, and politicians differ from those for the broader macroeconomy (workers and households)?

Based on the game, do you think lobbying for a tax cut would lead to more job creation? Why or why not?

Following the game, it can be useful to introduce students to the distinction between rent seeking, wherein individuals or firms try to gain a greater share of existing wealth, and profit-seeking activities, which increase returns by generating new wealth. As discussed above, one of the key insights of the activity is that there are different options available to firms to generate returns. The three options in the game represent broad categories of firm activities: profit seeking (physical investment), financial (stock buybacks), and rent seeking. As the game illustrates, all three can be privately beneficial for firms. However, only profit-seeking activities are socially beneficial. For example, investments in physical capital increase aggregate demand and employment in the short run, and improve productivity, contributing to faster economic growth and a higher standard of living in the long run. Society benefits when firms undertake these activities. The same cannot be said for stock buybacks or rent seeking, although they can be beneficial for individual firms, executives, and shareholders.6 As such, these activities have a social opportunity cost. Moreover, in many cases rent seeking can lead to policies that actively reduce efficiency, such as price floors, trade protections, and barriers to entry.

CEO Incentives, Shareholder Primacy, and Short-Term vs. Long-Term Corporate Decision Making

How would your approach to the game differ if your goal was to maximize your stock price after each round, or else you may be fired?

Should firms consider their responsibilities to customers, employees, and society, or should their only responsibility be to maximize returns for their owners and shareholders?

Based on our game, is a short-run or long-run focus for firms likely better for the economy as a whole?

One key element of the game’s structure is the timing of benefits for physical investment. Students must engage in physical investment for three consecutive terms before they receive a return. This is meant to reflect the long-term nature of some types of physical investment, especially research and development efforts. It can be useful to contrast this with the dominant corporate paradigm of shareholder primacy, which posits that the main, and perhaps only, goal of corporations should be to maximize returns for shareholders, some of whom may hold stocks for only a short amount of time (Stout 2013).7 Executive compensation is increasingly designed to align the incentives of corporate decision makers with those of shareholders by including sizable stock options in compensation packages (Sonenshine et al. 2016). If executive compensation packages and contracts are not well-designed, corporations may seek to maximize short-term stock prices, potentially to the detriment of long-term outcomes for the firm and various stakeholders (Stout 2013).

The game can be modified to highlight how a focus on the short term instead of the long term can impact firms’ decisions. Under this variation of the game, the team with the lowest stock price at the end of each round is eliminated. The likely outcome of this change is to disincentivize physical investment, which does not yield a return for the first two rounds. Although the game can be re-run with this variation in the rules, we have found that students who have played through the game can think through how a rule change would impact the outcome without actually playing through the game again. Therefore, simply asking students to consider the possibility is sufficient. However, instructors who wish to emphasize this point more fully may benefit from taking the time to run through this extension in full.

Financialization

Do all financial transactions benefit the economy?

Based on the game, how might increased financial activity affect total physical investment? What implications would this have for households and workers?

In recent decades, the financial sector has increased in size relative to GDP and become increasingly divorced from real economic activity, a phenomenon referred to as financialization. A sizable literature has explored the economic effects of financialization, finding that it has led to reduced investment, less spending on research and development, lower productivity, macroeconomic instability, lower bargaining power for workers, and growing inequality (Tori and Onaran 2017; Tridico and Pariboni 2017; Balder 2018; Hein 2019; Koehler et al. 2019; Pariboni and Tridico 2019; Stockhammer and Kohler 2020; Cauvel and Pacitti 2022). The game can serve as a useful entry point for discussion by highlighting the opportunity cost of financial activity by non-financial corporations. Instructors can supplement the micro-level illustration in the game with macro-level data on financialization and a discussion of its impact based on recent research.

Inequality and Economic Justice

Who is most likely to benefit from rent seeking? Why?

Imagine a variation of the game in which one person started with twice as much money as everyone else. What would be the most likely outcome in terms of rent seeking?

What are the implications of rent seeking for inequality?

Was the outcome of the game fair? Why or why not?

Is rent seeking likely to lead to outcomes that are economically just? In other words, will it generate a distribution of resources that you would consider to be fair?

In cases wherein firms have a common interest that benefits them at the expense of workers, what is the likely outcome of rent seeking?

The version of the exercise described above begins with a level playing field. Outcomes are likely to be driven partly by skill (thinking through the various options to see which have the highest payouts and probability of success) and partly by luck (the random selection of the rent winner if the highest bid is shared by two or more teams), but each team has an equal chance of winning at the beginning of the game. However, the game also illustrates how unequal outcomes can snowball over time, as those who succeed in the early rounds of the game through successful physical or political investment have a clear advantage in winning rents in later rounds. As such, the game highlights how rent seeking can exacerbate and perpetuate inequality.

A variation of the game can highlight this point even more fully. In this variation, teams are assigned different baseline budgets. For example, one team can have a baseline budget of $2000, while 50% of the remaining teams have a baseline budget of $1000, and the remaining 50% have a baseline budget of $500, though the exact levels or distribution is not crucial. Students will quickly see that those with the most resources are most likely to engage in and benefit from rent seeking. This can be a useful illustration of rent seeking’s role in maintaining inequality. However, as with the variation described above, we have found that playing through the game again with a new set of rules is not necessary as students understand the lesson based on the thought experiment alone.

Instructors wishing to discuss these issues further might encourage students to think of yet another variation of the game in which those with the largest budgets share common interests that would negatively affect those with lower budgets. This setup can help to explain rising inequality as partially the result of corporations seeking policies that redistribute wealth from labor to capital. Mishel and Bivens’ (2021) article on wage-suppression policies contains many useful examples of policies that can inform this discussion.

Democracy

Consider a variation of the game in which one party would receive massive benefits from a policy that would impose a small cost on everyone else. What do you think the likely outcome of rent seeking would be in this case?

Is rent seeking likely to generate socially-optimal policies?

What are the implications of rent seeking for democracy? Do all citizens have similar abilities to influence policy?

A final variation of the game, which is likely best posed as a thought experiment because students’ choices may be unrealistic in a game with no real consequences, can further highlight how rent seeking distorts policy. In this variation, students are asked to consider a policy that would take one additional dollar from every citizen in taxes and redistribute it among the 10 richest households in the country. The outcome will depend on whether more money is spent lobbying in favor of or against this policy. Students will likely recognize that the policy is likely to pass because the 10 beneficiaries would have more of an incentive to pay for lobbying than those who pay the costs, for whom the policy has little effect and coordination would be more difficult. Although policies are rarely framed this way, many have similar distributional effects, such as changes to marginal income tax rates, price floors, and licenses.

This thought experiment can explain why policies often represent the interests of small groups rather than the general public, serving as an entry to discussions about the relationship between capitalism and democracy. Other points in this discussion could include the theory of rational ignorance (Downs 1957) and research on the prevalence (O’Connell and Narayanswamy 2022) and effectiveness of lobbying (Lewis 2013; Kang 2016; McKay 2018; Butler and Miller 2021; Chalmers and Macedo 2021), the degree to which opinions of different groups impact policy (Gilens and Page 2014), and issues such as the revolving door and regulatory capture (Johnson and Kwak 2010; Bowles et al. 2018).

Potential Reforms

What policies could be implemented to limit the negative effects of rent-seeking behavior?

Those wishing to end the lesson on an optimistic note might consider focusing on potential policy reforms that could limit rent seeking and promote more democratic outcomes. Strow and Strow (2006) describe a number of examples, such as tax simplification, congressional term limits, and rotating committee chairpersons, which students could analyze and discuss. Students can also be encouraged to think of creative solutions.

Conclusion

Understanding the economic causes and consequences of rent-seeking behavior is critical to understanding how modern economies operate. Our Chief Executive Game is an easy-to-implement classroom exercise that actively engages students in discussions about the economics of rent seeking by letting them act as corporate decision makers. We highlight the key issues associated with rent-seeking behavior—social costs and benefits, long- and short-term incentives, financialization, inequality, democracy, and reforms—and provide discussion questions and extensions that promote critical classroom discussion. This exercise allows professors to dive deeper into the mechanics of how and for whom economies work, offering students a more comprehensive and realistic picture of modern economic dynamics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank three anonymous referees and participants at the Western Economic Association International 97th Annual Conference for providing helpful comments.

Appendix: Classroom Materials

The Chief Executive Game

In this game, you will play the role of a company’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO). Your goal is to maximize your company’s stock price and have the highest stock price at the end of the game.

Each firm’s stock value begins at 100.

- The game is played over 5 rounds. In each round, your job is to decide how to allocate your $1000 budget (in $100 increments, unless you have $50 remaining in your budget in which case you can spend it), which does not carry over from round to round. You have three options on which to spend your budget:

- Investment: Increasing productive capacity or developing new products allows you to earn higher profits, but it takes time before it increases your firm’s revenue.

- This increases your stock price by 35 points for each $100 spent in three separate rounds (if you spend $1000 on investment in Round 1, Round 2, and Round 3, your stock price would increase by 350 points after round 3). This benefit is earned only once, after the third round of investment. (Hint: Given that there are only five rounds, there is no benefit to starting an investment project after the third round.)

- For the sake of simplicity, once you have begun an investment project, you are not able to increase or decrease spending on it above the amount you initially spent. However, you can abandon it, in which case you don’t get any return for what you’ve already spent.

- Stock buybacks: You can immediately increase the price of your firm’s stock by buying shares yourself (directly increasing demand).

- This increases your stock price by 10 for each $100 spent.

- Rent-seeking activities: You can use funds to lobby the government for a favorable policy or contract in order to earn an above-market return. However, only one firm can benefit from rent seeking in each round.

- The firm that spends the most money on rent seeking wins the rent, which is modeled in the game as an increase of 110 points in the stock price.

- In the event of a tie, the winner of the rent is chosen randomly.

The budget for each round is $1000. However, those who successfully win a rent receive an additional $500 to spend in the following round. Similarly, those who successfully complete an investment project get an additional $0.50 for each dollar invested (for example, if $100 is invested in the first three rounds, this firm receives an additional $50 to spend in the fourth round).

Remember to think strategically—your goal is to achieve the highest stock price that you can!

The Chief Executive Game

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Footnotes

Students can only make a physical investment once, leaving two rounds where they must make a different investment choice, ensuring a diversity of strategies.

Admittedly the constant, one-period return to rent seeking is a simplification, as the payoffs to these types of activities can vary in duration. For example, rent-seeking behavior can influence returns in the short run. Kang (2016) finds the average return to lobbying expenditures within the two-year duration of a Congress to be 130%, thus generating returns more quickly than typical research and development efforts. However, in some cases more prolonged efforts may be needed to affect certain policies (Johnson and Kwak 2010). Instructors wishing to capture this nuance can consider adding a mechanism similar to what is used for physical investment, or even a more complicated system in which the time horizon is unknown. We prefer the more direct approach of telling students that we make some abstractions to simplify the exercise to most clearly emphasize the learning outcomes for the core topics.

We experimented with an approach, similar to Goeree and Holt (1999), in which there is some uncertainty in rent-seeking outcomes. We considered a probabilistic model with expected values for different types of investment, but found that these not only complicated the explanation, implementation, and execution of the game, but were likely to distract students from the central lessons of the exercise.

An automated spreadsheet template that can be shown on a projector, an instruction sheet, and a game play sheet that allows students to record their choices are available for download from this shared folder: https://bit.ly/CEOgame The handouts can also be found in the appendix.

We have used versions of this exercise three times, in both introductory classes and an upper-level elective at both a private liberal arts college and a regional comprehensive public university, with class sizes ranging from 11 to 24. We did not observe major differences across these contexts or any common misunderstandings. We expect that the exercise would work well in classes of up to 40 students, either in person or online (for example, using breakout groups in Zoom to allow students to work in teams), but it may be difficult to administer in large lecture halls. Since this is a relatively new exercise, we have not explicitly requested or received student feedback, though we were satisfied with its implementation and students’ participation and engagement with the content. Our own observations suggested that every student was actively engaged in the game and that it was effective in explaining the key concepts.

There is some disagreement in the literature about whether stock buybacks are socially efficient. At the micro-level, a case can be made that stock buybacks may be socially useful if they improve stock valuation (to be in line with internal valuations) or send appropriate signals regarding firm behavior, if the firm has excess cash, or if they are used as a tool to assist with risk management (Chen and Obizhaeva 2022). However, macro-level research seems to indicate that the practice as a whole has net-negative effects (Tori and Onaran 2017; Tridico and Pariboni 2017; Balder 2018; Hein 2019; Stockhammer and Kohler 2020). Instructors may choose to emphasize different aspects of buybacks, or exclude them entirely, to tailor the game to their pedagogical objectives.

Highlighting the shift to more short-term focused investing, data shows that the average holding period for a stock declined from a peak of roughly 8 years in the 1950s to about 5.5 months in 2020 (Chatterjee and Adinarayan 2020).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aaron Pacitti, Email: apacitti@siena.edu.

Michael Cauvel, Email: michael.cauvel@maine.edu.

References

- Autor David, Cho David, Crane Leland D, Goldar Mita, Lutz Byron, Montes Joshua, Peterman William B, Ratner David, Villar Daniel, Yildirmaz Ahu. The $800 Billion Paycheck Protection Program: Where Did the Money Go and Why Did It Go There? Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2022;36(2):55–80. doi: 10.1257/jep.36.2.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autor David, Dorn David, Katz Lawrence F, Patterson Christina, Van Reenen John. The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2020;135(2):645–709. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjaa004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Balder John M. Financialization and Rising Income Inequality: Connecting the Dots. Challenge. 2018;61(3):240–254. doi: 10.1080/05775132.2018.1471384. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bischoff Ivo, Hofmann Kai. Classroom Game on the Theory of Rent Seeking: Some Practical Experience. Southern Economic Journal. 2002;69(1):195–199. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles Samuel, Carlin Wendy. What Students Learn in Economics 101: Time for a Change. Journal of Economic Literature. 2020;58(1):176–214. doi: 10.1257/jel.20191585. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles Samuel, Edwards Richard, Roosevelt Frank, Larudee Mehrene. Understanding Capitalism: Competition, Command, and Change. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein Elissa. The Feminist Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society: An Investigation of Gender Inequality and Economic Growth. Journal of Economic Issues. 2008;42(4):959–979. doi: 10.1080/00213624.2008.11507198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butler Daniel M, Miller David R. Does Lobbying Affect Bill Advancement? Evidence from Three State Legislatures. Political Research Quarterly. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10659129211012481. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cauvel Michael, Pacitti Aaron. Bargaining Power, Structural Change, and the Falling U.S. Labor Share. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics. 2022;60(March):512–530. doi: 10.1016/j.strueco.2022.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers Adam William, Macedo Francisco Santos. Does It Pay to Lobby? Examining the Link between Firm Lobbying and Firm Profitability in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy. 2021;28(12):1993–2010. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2020.1824012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, Saikat, and Thyagaraju Adinarayan. 2020. Buy, Sell, Repeat! No Room for 'Hold' in Whipsawing Markets. Reuters, August 3. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-short-termism-anal/buy-sell-repeat-no-room-for-hold-in-whipsawing-markets-idUSKBN24Z0XZ.

- Chen Alvin, Obizhaeva Olga A. Stock Buyback Motivations and Consequences: A Literature Review. Charlottesville: CFA Institute Research Foundation; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CORE. 2022. The Economy. https://www.core-econ.org.

- Dorestani Alireza. Is Interactive/Active Learning Superior to Traditional Lecturing in Economics Courses? Humanomics. 2005;21(1):1–20. doi: 10.1108/eb018897. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downs Anthony. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman Scott, Eddy Sarah L, McDonough Miles, Smith Michelle K, Okoroafor Nnadozie, Jordt Hannah, Wenderoth Mary Pat. Active Learning Increases Student Performance in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014;11(23):8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilens Martin, Page Benjamin I. Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens. Perspectives on Politics. 2014;12(3):564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goeree Jacob K, Holt Charles A. Rent-Seeking and the Inefficiency of Non-market Allocations. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 1999;13(3):217–226. doi: 10.1257/jep.13.3.217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker Jacob S, Pierson Paul. Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer–and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. New York: Simon and Schuster; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hall Joshua, Matti Josh, Ferreira Neto Amir B. Rent-seeking in the Classroom and Textbooks: Where Are We After 50 Years? Public Choice. 2019;181(1):71–82. doi: 10.1007/s11127-018-0563-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hein Eckhard. Financialisation and Tendencies Towards Stagnation: The Role of Macroeconomic Regime Changes in the Course of and after the Financial and Economic Crisis 2007–09. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 2019;43(4):975–999. doi: 10.1093/cje/bez022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Igan, Deniz, Prachi Mishra, and Thierry Tressel. 2011. A Fistful of Dollars: Lobbying and the Financial Crisis. National Bureau of Economic Research. Working Paper 17076.

- Johnson Simon, Kwak James. 13 Bankers: The Wall Street Takeover and the Next Financial Meltdown. New York: Vintage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Karam. Policy Influence and Private Returns from Lobbying in the Energy Sector. The Review of Economic Studies. 2016;83(1):269–305. doi: 10.1093/restud/rdv029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler Karsten, Alexander Guschanski, Engelbert Stockhammer. The Impact of Financialisation on the Wage Share: A Theoretical Clarification and Empirical Test. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 2019;43(4):937–974. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, Frank, and Peter Temin 2007. Inequality and Institutions in 20th Century America. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 13106.

- Lewis Daniel C. Advocacy and Influence: Lobbying and Legislative Outcomes in Wisconsin. Interest Groups & Advocacy. 2013;2(2):206–226. doi: 10.1057/iga.2013.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie Ian A. Rent Creation and Rent Seeking in Environmental Policy. Public Choice. 2017;171(1):145–166. doi: 10.1007/s11127-017-0401-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKay Amy Melissa. Fundraising for Favors? Linking Lobbyist-Hosted Fundraisers to Legislative Benefits. Political Research Quarterly. 2018;71(4):869–880. doi: 10.1177/1065912918771745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel, Lawrence, and Josh Bivens. 2021. Identifying the Policy Levers Generating Wage Suppression and Wage Inequality. Economic Policy Institute Report. https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/wage-suppression-inequality/.

- O’Connell, Jonathan, and Anu Narayanswamy. 2022. Lobbying Broke All-time Mark in 2021 amid Flurry of Government Spending. The Washington Post, March 12, 2022. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2022/03/12/lobbying-record-government-spending/.

- Pariboni Riccardo, Tridico Pasquale. Labour Share Decline, Financialisation and Structural Change. Cambridge Journal of Economics. 2019;43(4):1073–1102. doi: 10.1093/cje/bez025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roush Justin R, Johnson Bruce K. A College Athletics Recruiting Game to Teach the Economics of Rent-seeking. The Journal of Economic Education. 2018;49(2):200–208. doi: 10.1080/00220485.2018.1438942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salemi Micahel K. An Illustrated Case for Active Learning. Southern Economic Journal. 2002;68(3):721–731. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan Brandon J, Smith Ben. How Often Does Active Learning Actually Occur? Perception versus Reality. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings. 2020;110(May):304–308. [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshine Ralph, Larson Nathan, Cauvel Michael. Determinants of CEO Compensation before and after the Financial Crisis. Modern Economy. 2016;7(12):1455–1477. doi: 10.4236/me.2016.712133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stockhammer Engelbert, Kohler Karsten. Financialization and Demand Regimes in Advanced Economies. In: Mader Philip, Mertens Daniel, van der Zwan Natascha., editors. The Routledge International Handbook of Financialization. London: Routledge; 2020. pp. 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- Stout Lynn A. The Toxic Side Effects of Shareholder Primacy. University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 2013;161(7):2003–2023. [Google Scholar]

- Strow Brian Kent, Strow Claudia Wood. A Rent-Seeking Experiment for the Classroom. Journal of Economics Education. 2006;37(3):323–330. doi: 10.3200/JECE.37.3.323-330. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tila Dorina. Economic Experiments in a Classroom Improve Learning and Attitudes toward Economics: A Case Study at a Community College of the City University of New York. Journal of Education for Business. 2021;96(5):308–316. doi: 10.1080/08832323.2020.1812489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tori, Daniele, and Özlem Onaran. 2017. The Effects of Financialisation and Financial Development on Investment: Evidence from Firm-level Data in Europe. Greenwich Political Economy Research Centre Working Paper 44.

- Tridico Pasquale, Pariboni Riccardo. Inequality, Financialization, and Economic Decline. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics. 2017;41(2):236–259. doi: 10.1080/01603477.2017.1338966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]