Abstract

Immunomodulators that remodel the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment have been combined with anti-programmed death 1 (α-PD1) or anti–programmed death ligand 1 (α-PDL1) immunotherapy but have shown limited success in clinical trials. However, therapeutic strategies to modulate the immunosuppressive microenvironment of lymph nodes have been largely overlooked. Here, we designed an albumin nanoparticle, Nano-PI, containing the immunomodulators PI3Kγ inhibitor (IPI-549) and paclitaxel (PTX). We treated two breast cancer mouse models with Nano-PI in combination with α-PD1, which remodeled the tumor microenvironment in both lymph nodes and tumors. This combination achieved long-term tumor remission in mouse models and eliminated lung metastases. PTX combined with IPI-549 enabled the formation of a stable nanoparticle and enhanced the repolarization of M2 to M1 macrophages. Nano-PI not only enhanced the delivery of both immunomodulators to lymph nodes and tumors but also improved the drug accumulation in the macrophages of these two tissues. Immune cell profiling revealed that the combination of Nano-PI with α-PD1 remodeled the immune microenvironment by polarizing M2 to M1 macrophages, increasing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells, decreasing regulatory T cells, and preventing T cell exhaustion. Our data suggest that Nano-PI in combination with α-PD1 modulates the immune microenvironment in both lymph nodes and tumors to achieve long-term remission in mice with metastatic breast cancer, and represents a promising candidate for future clinical trials.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women worldwide (1). Despite the advances in treatments for primary breast cancer, which have led to a 90% 5-year survival rate (2), patients with distal metastasis still lack effective treatment options (3) and have a 5-year survival rate of 13 to 28% (4). Most recently, anti–programmed death 1 (α-PD1) or anti–programmed death ligand 1 (α-PDL1) immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy has been approved as standard treatment option for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) but only showed a 50% overall response rate and 9 to 17% complete response rate (CR) (5-7). It is hypothesized that the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment is one of the main contributing factors for the poor responses to the combined immunotherapy and chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer (8-13).

Various immunomodulators have been developed to remodel the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment to boost the efficacy of α-PD1/α-PDL1 immunotherapy and chemotherapy (9-13). Previous studies have shown that microenvironmental signals can differentiate tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to either proinflammatory M1 macrophages or immunosuppressive M2 macrophages (10-14). In tumor sites, M2 macrophages promote cancer progression and metastasis (11, 12, 14), hinder the efficacy of α-PD1/α-PDL1 immunotherapy, and are often correlated with poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer (10-13). Although different immunomodulating approaches have been explored to inhibit M2 macrophages at tumor sites, some of these immunomodulators failed to improve the clinical efficacy of α-PD1/α-PDL1 immunotherapy (15), whereas some others are currently under clinical trials (10, 11, 13). For instance, a promising target, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase γ (PI3Kγ), is known to control the switch between M1/M2 macrophage polarization regulating the immune response to cancer immunotherapy (16, 17). Recently, a PI3Kγ inhibitor (IPI-549), in combination with albumin-5 based paclitaxel (Nab-PTX, Abraxane) and α-PDL1 antibody, has been evaluated for the treatment of breast cancer in clinical studies (18). Early data from this clinical evaluation indicate improved anticancer efficacy [in PDL1+ patients: progression-free survival (PFS), 11.0 months; in PDL1− patients: PFS, 7.3 months] in 41 patients with TNBC in comparison with historical IMpassion130 trial using combination of Abraxane and α-PDL1 (in PDL1+ patients: PFS, 7.4 months; in PDL1− patients: PFS, 5.6 months), but these two trials were conducted at different times and were not compared head-to-head. It remains to be seen whether the combination of these three drugs in the larger phase 3 trial can enhance their efficacy.

However, current strategies mainly focus on regulating the tumor microenvironment, whereas very few studies therapeutically target the immunosuppressive lymph nodes, which play a crucial role in initiating the progression and metastasis of cancer (19, 20). Primary breast tumors secrete immunomodulatory cytokines during cancer progression and metastasis. This leads to lymphangiogenesis and recruitment of immunosuppressive cells to tumor-draining lymph nodes. Such effects prime the microenvironment to attract tumor cells from the primary site to lymph nodes via lymphatic vessels (21, 22). These seeded tumor cells in lymph nodes further recruit immunosuppressive cells to help tumor cell colonization and proliferation in the metastatic niche of the lymph nodes, leading to their dissemination to distant organs via lymphatic or hematogenous routes (23, 24). Therefore, simultaneously modulating the immunosuppressive microenvironment in lymph nodes and tumors may cut off their interplay during tumor progression and metastasis, thus improving the efficacy of immunotherapy for metastatic breast cancer.

Immunosuppressive M2 macrophages not only dominate the protumor immune response at tumor site but also play a key role in tipping the balance from anticancer immunity to immune tolerance in the lymph node microenvironment, which further facilitates cancer progression and metastasis (11, 23, 25, 26). Several clinical studies have shown that infiltration of M2 macrophages in lymph nodes correlates with metastasis and poor prognosis (27-31). However, most current immune modulators, after intravenous (IV) or oral (PO) administration, have limited accumulation in either the lymph nodes or tumor sites, which hinders their clinical efficacy.

In this study, we designed a nanomedicine to deliver immunomodulators, in combination with α-PD1, to remodel the microenvironment in both lymph nodes and tumors for achieving long-term tumor remission in metastatic breast cancer mouse models. An albumin nanoparticle was generated to encapsulate PI3Kγ inhibitor (IPI-549) and PTX (Nano-PI), where PTX combined with IPI-549 enhanced the repolarization of M2 to M1 macrophages and enabled the formation of stable albumin nanoparticle. Nano-PI was evaluated for delivery of two drugs to macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumors. The efficacy of Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 was tested in both transgenic mouse with spontaneous breast cancer and mouse xenograft breast cancer models. The modulation of the immune microenvironment by Nano-PI in both lymph nodes and tumors was extensively investigated using cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF). The therapeutic advantage of our nanomedicine (Nano-PI) to achieve long-term tumor remission provides a strong rationale for future clinical evaluation in patients with metastatic breast cancer.

RESULTS

Tumors and lymph nodes of PyMT transgenic mice with spontaneous metastatic breast cancer showed an increased M2 macrophage infiltration

We monitored the total macrophage population, as well as M1 and M2 macrophage frequencies in both tumor and lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice (FVB/NJ) with spontaneous breast cancer and lung metastasis (32). Macrophage infiltration was observed in breast tumor lesions (25.1 ± 0.5%) compared to that in the normal fat pad (6.2 ± 1.0%), whereas the M2 phenotype was threefold higher in tumors (82.0 ± 5.3%) than in fat pads of control mice (27.3 ± 2.8%) (Fig. 1A). In addition, M2 macrophages were 3.9-fold higher in the lymph nodes of tumor-bearing mice than in those of naive mice (83.2 ± 2.5% versus 21.5 ± 1.6%, P = 0.001), although the total number of macrophages in the lymph nodes from tumor-bearing mice and normal mice was similar (Fig. 1B). These results were validated through immunofluorescence staining, which showed higher amounts of M2 macrophages in both the tumors and lymph nodes (Fig. 1, C and D). This increase in M2 macrophages in both tumors and lymph nodes in the PyMT spontaneous metastatic breast cancer model is consistent with clinical observations in patients with breast cancer (27-30). Thus, our observations suggest that the modulation of M2 macrophages in both tumors and lymph nodes may lead to better treatment outcomes in metastatic breast cancer.

Fig. 1. Increased M2 macrophage infiltration in tumors and lymph nodes in tumor-bearing mice and combination of IPI-549 and PTX enhanced M2 to M1 macrophage repolarization to inhibit MTC growth.

(A and B) Representative images of flow cytometry and quantification of F4/80+CD11b+ (macrophages), CD80+CD206− (M1 phenotype), and CD80−CD206+ (M2 phenotype) in tumor (PyMT-tumor), normal fat pad (N-fat pad), normal lymph nodes (N-LNs), and lymph nodes in tumor-bearing mice (PyMT-LNs). n = 3. Data are means ± SD. ***P < 0.001. (C and D) Confocal microscopy images of macrophages (red) with M2 phenotype (green) in tumor and lymph nodes of PyMT mice. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 100 μm. (E to H) Concentrations of TNF-α, IL-12, IL-10, and TGF-β in M2 macrophage cell–cultured medium (derived from the bone marrow–derived macrophages), as measured by ELISA, after treatment with PTX (5 μM), IPI (IPI-549,5 μM), DOX (doxorubicin, 5 μM), GEM (gemcitabine, 5 μM), PI (PTX, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM), DI (doxorubicin, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM), and GI (gemcitabine, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM). n = 3. Data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (I) Schematic of 3D MTCs. (J and K) Tumor growth curves and images of the 3D MTCs showing anticancer effect of single-drug treatment with PTX, IPI, DOX, or GEM at the concentration of 5 μM, and the combination treatment with PI (PTX, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM), DI (doxorubicin, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM), or GI (gemcitabine, 2.5 μM plus IPI-549, 2.5 μM). PBS treatment served as the control, n = 3. Data are means ± SD. ***P < 0.001. Significant differences as compared with PBS-treated group (***P < 0.001).

Enhanced M2 to M1 macrophage repolarization and inhibition of tumor spheroid growth by the combination of IPI-549 with PTX

Because previous studies reported that chemotherapy may either increase recruitment of M2 macrophages (33, 34) or induce M2 to M1 macrophage polarization (35, 36), we screened for an optimal combination of IPI-549 and chemotherapeutic drugs that could effectively repolarize M2 macrophages to the M1 phenotype (fig. S1). Bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) were pretreated with interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13 to polarize them to M2 macrophages and then treated with various combinations of drugs. As shown in Fig. 1 (E to H), the combination of IPI-549 with PTX enhanced M2 to M1 macrophage polarization as depicted by an increase in M1 markers [tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) and IL-12] and a decrease in M2 markers [IL-10 and transforming growth factor–β (TGF-β)] in comparison with either IPI-549 or PTX alone. However, combinations of IPI-549 with other chemotherapeutic agents (doxorubicin and gemcitabine) did not show such an effect.

We also established three-dimensional (3D) multicellular tumor spheroids (MTCs) by coculturing breast cancer 4T1 cells with M2 macrophages derived from RAW264.7 cells, at a ratio of 7:3 to further investigate the synergistic effect of IPI-549 and PTX against cancer cell growth in the presence of M2 macrophages (Fig. 1I). The combination of IPI-549 and PTX completely inhibited 3D MTC growth (Fig. 1, J and K), whereas the combination of IPI-549 with doxorubicin and gemcitabine did not show any improvement compared with a single drug treatment. In addition, a single agent alone, such as IPI-549, PTX, doxorubicin, or gemcitabine, showed limited inhibition of 3D MTC growth (Fig. 1, J and K). In addition, PTX and IPI-549 demonstrated a synergistic effect in inhibiting MTC growth in a coculture of 4T1 cancer cells and M2 macrophages, in comparison with single drug treatment alone at the different concentrations as indicated by a combination index (CI) of 0.7 (less than 1) (fig. S2, C to G). However, the combination of IPI-549 with different chemotherapeutic agents, such as PTX, doxorubicin, and gemcitabine, did not show improvement in inhibiting 3D 4T1 cell tumor spheroids without macrophages compared to the single drug treatments (fig. S2, A and B). These data suggest that the synergistic antitumor effect of IPI-549 and PTX is macrophage dependent.

Nanoparticle of IPI-549 and PTX (Nano-PI) enhanced the accumulation of IPI-549 and PTX in macrophages located in both tumors and lymph nodes

To repolarize immunosuppressive macrophages, the small molecules should be delivered to the macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumors. Free IPI-549 and PTX have limited accumulation in tumor and lymph nodes and thus have low macrophage distribution within these tissues. Previously, we have shown that albumin nanoparticles of PTX (Abraxane, Nano-P) can specifically accumulate in TAMs (37). Therefore, we designed the albumin nanoparticles co-encapsulated with IPI-549 and PTX (Nano-PI). We hypothesized that the molecular interaction between the two drugs might have helped to encapsulate them together because of the existing high binding affinity between PTX and albumin, whereas IPI-549 alone cannot be encapsulated in the albumin nanoparticle. Characterization of Nano-PI revealed a diameter of 143.5 ± 2.0 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.125 ± 0.0158 and spherical morphology (Fig. 2, A and B). The drug loading capacities in Nano-PI suspension were 8.1 ± 0.04% (PTX) and 4.3 ± 0.04% (IPI-549), whereas the encapsulation efficiencies of Nano-PI were 88.0 ± 2.8% (PTX) and 83.8 ± 5.4% (IPI-549). The drug recovery yield after processing was 90.7 ± 4.7% (PTX) and 73.3 ± 11.9% (IPI-549). The final drug ratio in Nano-PI was 2:1 (PTX: IPI-549, w/w), which exerted an additive effect on macrophage repolarization and synergistic tumor growth inhibition (figs. S2 and S3). Nano-PI was stable within the dilution to PTX concentration of 2 × 10−4 mg/ml [in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] and to 4 × 10−4 mg/ml [in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS)], respectively (Fig. 2, C and D, and fig. S4A). The in vitro drug release profiles of Nano-PI in plasma at 37°C show that both PTX and IPI-549 were released more slowly as compared to free drug (fig. S4, B and C). Furthermore, Nano-PI promoted macrophage repolarization from the M2 to M1 phenotype, leading to a more potent inhibition of cancer cell migration than PTX or IPI-549 alone (fig. S5).

Fig. 2. Nano-PI characterization and enhanced accumulation in both tumors and lymph nodes in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.

(A) Size distribution of Nano-PI (PTX, 0.2 mg/ml) detected by dynamic light scattering (n = 3). (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging of Nano-PI. Scale bar, 200 nm. (C and D) Stability of Nano-PI as measured by size distribution with different dilutions (PTX concentration from 2 × 10−3 to 2 × 10−5). (E and F) PTX and IPI-549 concentration in plasma, lymph nodes, tumor, and fat pad after intravenous injection of free PTX and IPI-549 (PTX/IPI), intravenous injection of albumin formulation of PTX (Nano-P) plus oral or intraperitoneal injection of IPI-549 [Nano-P + IPI (PO) or Nano-P + IPI (IP)], and Nano-PI at the dose of PTX (5 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (2.5 mg/kg) into 14- to 15-week-old MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice with spontaneous breast cancer (3 mice per group, 10 tumors, and 8 fat pad tissues were analyzed for each mouse). Data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Significant difference as compared with PTX/IPI (free drug) group.

Next, we evaluated whether intravenous administration of Nano-PI could enhance drug accumulation in the tumors and lymph nodes in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice with spontaneous breast cancer. Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was performed to quantify the drug concentration in tissues (Fig. 2, E and F, and fig. S6). As shown in Fig. 2 (E and F) and table S1, Nano-PI resulted in an increased accumulation of both PTX and IPI-549 in tumors and lymph nodes compared to that of free drug (PTX/IPI, IV). This was demonstrated by a 2.4- and 2.2-fold increased area under the curve (AUCtissue) of PTX and IPI-549 in tumors and a 2.0- and 2.2-fold increased AUCtissue in lymph nodes as compared with free drug. In addition, Nano-PI increased the accumulation of IPI-549 in tumor and lymph node by 2.3- and 2.5-fold (AUCtissue) in comparison with the clinically used combination of PTX albumin nanoparticle (Nano-P, IV) and IPI-549 (PO) (Nano-P/IPI, PO) or Nano-P (IV) plus IPI-549 [intraperitoneal (IP)] (Fig. 2, E and F, and table S1).

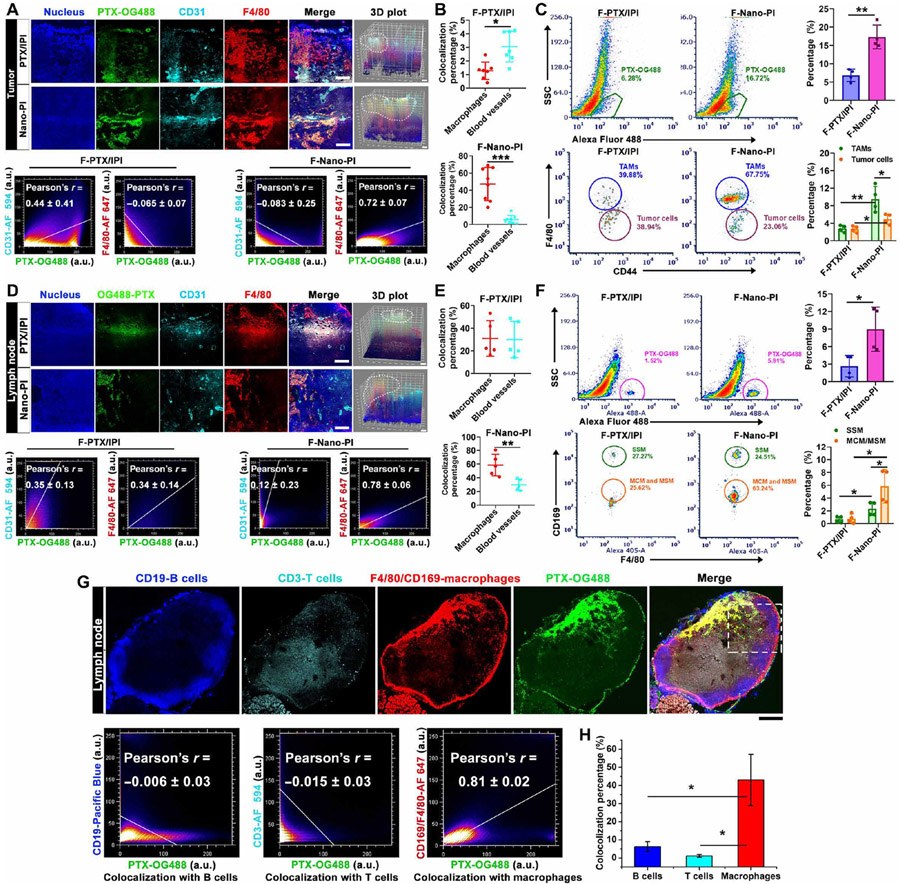

To evaluate whether Nano-PI efficiently delivered the drug to macrophages in both tumors and lymph nodes, we prepared Nano-PI encapsulated with fluorescent OG488-labeled PTX and IPI-549 (F-Nano-PI). We then visualized drug distribution in different types of cells in both tumors and lymph nodes after intravenous administration by confocal imaging and flow cytometry. F-Nano-PI (green) predominantly distributed in macrophages in tumors as indicated by the colocalization with macrophages (red) (Fig. 3, A and B, and fig. S6). Flow cytometry analysis further proved that F-Nano-PI increased drug accumulation in tumors (from 6.9 ± 1.5% to 17.3 ± 2.8%) as compared to free drug (F-PTX/IPI). Free drugs were evenly distributed in tumor cells (39.88%) and TAMs (38.94%), whereas F-Nano-PI was distributed more in TAMs (67.75%) than in tumor cells (23.06%) (Fig. 3C and fig. S7).

Fig. 3. Nano-PI enhanced delivery to macrophages in both tumors and lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.

(A) Representative tumor confocal microscopic images and 3D mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) plot (area within dashed box) show the drug (green) distribution, and pixel-by-pixel Pearson’s correlation r value (means ± SD, n = 4) of drug colocalization with blood vessels (α-CD31) and macrophages (α-F4/80). Tumor samples were collected 4 hours after intravenous injection of Nano-PI encapsulated with fluorescent PTX-OG488 and IPI-549 (F-Nano-PI) or free PTX-OG488 plus IPI-549 (F-PTX/IPI) in MMTV-PyMT mice. The macrophages, blood vessels, and nucleus were stained with F4/80 (red), CD31 (cyan), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 200 μm. Area within dashed box to show the overlay of F-PTX/IPI with blood vessels (white) or macrophages (yellow), a.u., arbitrary units. (B) Quantification of overlay of drug with blood vessel and macrophages in tumors. F-PTX/IPI (n = 8), Nano-PI (n = 7). (C) Representative images of flow cytometry and quantifications of drug (PTX-OG488) distribution in TAMs (F4/80) and tumor cells (CD44) within tumor tissues collected 4 hours after intravenous injection of F-Nano-PI and F-PTX/IPI in MMTV-PyMT mice (n = 4). (D) Representative lymph node confocal images and 3D MFI plot show the drug (green) distribution, and pixel-by-pixel Pearson’s correlation r value (means ± SD, n = 4) of drug with blood vessels (α-CD31) and macrophages (α-F4/80). Lymph node samples were collected 4 hours after intravenous injection of F-Nano-PI and F-PTX/IPI in MMTV-PyMT mice. The macrophages, blood vessels, and nucleus were stained with F4/80 (red), CD31 (cyan), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 200 μm. Area within dashed box to show the overlay of F-PTX/IPI with blood vessels (white) or macrophages (yellow). (E) Quantification of overlay of drug with blood vessels (α-CD31) and macrophages (α-F4/80) in lymph nodes (n = 5). (F) Representative images of flow cytometry and quantifications of drug (PTX-OG488) in SSM (CD169) and MCM/MSM (F4/80) cells within lymph nodes 4 hours after intravenous injection of F-Nano-PI and F-PTX/IPI in MMTV-PyMT mice, n = 4 independent experiments. (G) Confocal microscopic imaging shows the drug (green) distribution within lymph nodes, and pixel-by-pixel Pearson’s correlation r value (means ± SD, n = 6) of drug colocalization with B cells, T cells, and macrophages (area within dashed box), and (H) quantification of colocalization of drug with B cells, T cells, and macrophages 4 hours after administration of F-Nano-PI and F-PTX/IPI in MMTV-PyMT mice (n = 3). The macrophages, B cells, T cells, and nucleus were stained with F4/80 and CD169, CD19, CD3, and DAPI, respectively. Data are means ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

In lymph nodes, Nano-PI also enhanced drug accumulation in macrophages as indicated by the strong colocalization of F-Nano-PI (green) with macrophages (red) but not with B or T cells (Fig. 3, D to G, and fig. S8). Furthermore, F-Nano-PI was distributed more in medullary sinus macrophages (MSMs) and medullary cord macrophages (MCMs) than in subcapsular sinus macrophages (SSMs) (Fig. 3, F to H). In contrast, the distribution of the free drug (PTX-OG488) in lymph nodes was lower and less colocalized in macrophages. Collectively, our data suggested that Nano-PI enhanced the delivery of PTX and IPI-549 to lymph nodes and tumors especially to the macrophages in these tissues in comparison with free drugs.

Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 led to complete long-term remission and eliminated lung metastasis in PyMT transgenic mice

The antitumor efficacy of Nano-PI in combination with α-PD1 treatment was evaluated in transgenic MMTV-PyMT mice with spontaneous breast cancer and lung metastasis (32, 38-40). The MMTV-PyMT mouse grew 1 to 15 mammary tumor foci and developed multiple lung metastases lesions in 8 to 10 weeks. They were sacrificed when the largest tumor lesion reached 2 cm in diameter. Drug treatment began when mice were 9 to 10 weeks old when the multifocal mammary adenocarcinomas had reached a total volume of 80 to 110 mm3 for all lesions (Fig. 4A). Combination treatment of Nano-PI [PTX (10 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (5 mg/kg) via five IV doses] and α-PD1 antibodies (100 μg per mouse, three doses by IP injection) eradicated tumor growth and achieved complete tumor remission (100% CR) over 183 days after birth (Fig. 4B and fig. S9, A and B), eliminated lung metastasis (Fig. 4C), and resulted in 100% mouse survival (Fig. 4D). The average total tumor volume per mouse in the vehicle group reached 12020.4 ± 2404.1 mm3 on an average of 88 days after birth, and the median survival time was 88 days (50% of mice died or were sacrificed as predetermined to reach the end points) (Fig. 4B). The current clinically tested regimen, IPI-549 (PO) combined with Nano-P (IV) and α-PD1 (IP), resulted in delaying tumor growth and a median survival of 123 days but did not achieve complete cancer remission (0% CR). Other treatment groups including Nano-P (IV), Nano-P (IV) plus α-PD1, IPI-549 (PO) plus α-PD1, and Nano-PI (IV) only did not achieve complete tumor remission (Fig. 4, A to D). The antitumor efficacy of Nano-PI plus α-PD1 was confirmed again using the same dosing regimen as described above compared with the three-drug combination of Nano-P, IPI-549 (IP), and α-PD1 (fig. S9C). Nano-PI plus α-PD1 exhibited complete tumor remission (>130 days), whereas the combination of Nano-P and IPI-549 (IP) and α-PD1 showed only a partial response (fig. S9, D to F).

Fig. 4. Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 achieved long-term complete remission and eliminated lung metastasis in MMTV-PyMT mice.

(A) Illustration of dosing scheme shows that MMTV-PyMT mice were administrated with different treatments at day 66 after birth and observed for 183 days after birth. (B) Total tumor volume changes as calculated by the sum of all tumors in each mouse (n = 10) after different treatments: mouse serum albumin (vehicle, IV), Nano-P (10 mg/kg, IV), Nano-P (10 mg/kg, IV) plus α-PD1, IPI-549 (15 mg/kg, PO) plus α-PD1, Nano-P (5 mg/kg, IV) plus IPI-549 (5 mg/kg, PO), and α-PD1, Nano-PI (PTX, 10 mg/kg; IPI-549,5 mg/kg), Nano-PI (PTX, 10 mg/kg; IPI-549, 5 mg/kg) plus α-PD1. The drug treatment was given intravenously once every 3 days for five doses. α-PD1 was administered intraperitoneally once every 3 days for three doses (100 μg per mouse) (C) H&E and Bouin’s staining and quantification of metastatic nodules in the lung on the 183rd day after birth. The red circle shows the metastatic lesions. (D) Survival rate of MMTV-PyMT mice after treatment (n = 10). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. Statistically significant differences as compared with Nano-P plus α-PD1 group (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (E) Schematic depicting treatment schedule for tumor rechallenge in the MMTV-PyMT mice with tumor remission after treatment of Nano-PI plus a-PD1 on 210 days after birth as described in Fig. 4A, and wild-type FVB/NJ female mice served as control. (F) Changes in tumor volumes were measured for 38 days after tumor inoculation. (G) Illustration of dosing scheme showing that MMTV-PyMT mice were treated with different treatments at 80 days after birth. (H) Total tumor volume changes as calculated by the sum of all tumors in each mouse (n = 10) after IV dose of vehicle, PTX/IPI-549 (PTX, 5 mg/kg; IPI-549,2.5 mg/kg, IV) plus α-PD1, and Nano-PI (PTX, 5 mg/kg; IPI-549,2.5 mg/kg, IV) for five times plus α-PD1 (100 μg per mouse, IP) for three times. (I) H&E and Bouin’s staining and quantification analysis show metastatic nodules of the lung on the 113th day after birth. Red circles show the metastasis lesions. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). #P < 0.05. Statistically significant differences as compared with PTX/IPI-549 plus α-PD1 group (**P < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). (J) Survival rate after treatment of different formulations at a low dose (n = 10).

To test the long-term efficacy of Nano-PI plus α-PD1 in the mice with tumor remission, we next performed tumor rechallenge implantation on day 210 after birth on the PyMT mice with tumor remission by implanting (subcutaneously) PyMT cancer cells (5 × 106 cells/ml) in the mammary fat pads and without further treatment (Fig. 4E). The mice with long-term tumor remission that were initially treated with Nano-IP and α-PD1 completely rejected tumor growth from the implanted PyMT cancer cells for 38 days, whereas naive mice (FVB/NJ mice, control group) showed tumor growth of ~400 m3 (Fig. 4F). These data did not suggest treatment of Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 completely cured the PyMT spontaneous breast cancer mice because we observed that endogenous tumor lesions started to grow around 200 days after birth. In addition, we detected the total memory T and B cell populations in the peripheral blood, bone marrow, lymph nodes, spleen, and lung at the end of the tumor rechallenge experiments (248 days after birth). Compared with the control group, the mice with long-term tumor remission and previous treatment had higher central memory T cells (CD3+CD62L+CD44+) and effector memory T cells (CD3+CD62L−CD44+) (fig. S10, A to F). Furthermore, we also measured four memory-related B cell subsets: MB1 (CD19+CD73+CD80+), MB2 (CD19+CD73+PDL2+), MB3 (CD19+PDL2+CD80+), and MB4 (CD19+CD73+CD80+PDL2+) (fig. S10, G to L). Mice with long-term tumor remission also had higher amounts of these four subtypes of B cells in the lymph nodes, spleen, bone marrow, peripheral blood, and lungs. These data suggest that Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 may have induced higher total memory cells, which probably contribute to its long-term anticancer efficacy. However, we only measured total immune memory cells, but not antigen-specific memory cells, due to unknown antigens in this model.

We further tested the antitumor efficacy of Nano-PI at a lower dose in comparison with a combination of free PTX and IPI-549 by intravenous administration (five doses). Nano-PI [PTX (5 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (2.5 mg/kg), IV] plus α-PD1 (100 μg per mouse, three doses, IP) or the combination of free PTX (5 mg/kg, IV) and IPI-549 (2.5 mg/kg, IV) plus α-PD1(100 μg per mouse, three doses, IP) were administered to MMTV-PyMT mice (Fig. 4G). Compared to combination of free PTX and IPI-549, Nano-PI treatment inhibited tumor growth (Fig. 4H) and lung metastasis (Fig. 4I) and resulted in 100% survival at the end of observation (Fig. 4J). Last, we also evaluated the anticancer efficacy of Nano-PI and α-PD1 treatment in an orthotopic metastatic breast tumor model by implanting 4T1 cells into the mammary fat pad of BALB/c mice (41). Nano-PI [three doses, once every 3 days, PTX (10 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (5 mg/kg)] in combination with α-PD1 exhibited the most anticancer efficacy on tumor growth and lung metastasis, compared with either single administration of Nano-P or IPI-549 or a combined administration (fig. S11).

Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 remodeled tumor immune microenvironment by promoting M2 to M1 macrophage repolarization, increasing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, decreasing Tregs, and preventing T cell exhaustion in tumors

To explore the details of how Nano-PI remodeled the tumor immune microenvironment, we first used CyTOF to monitor tumor immune cell profiles in MMTV-PyMT spontaneous breast cancer 10 days after the last treatment. The Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment altered the M1 and M2 frequencies, resulting in fivefold reduction in M2 macrophages and a twofold increase in M1 macrophage population (M1, 15.87%; M2, 3.2%), in comparison with intravenous injection of Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 (M1, 24.37%; M2, 16.4%) or the vehicle group (M1, 8.4%; M2, 22.55%) (Fig. 5A). Nano-PI plus α-PD1 reduced expression of immunosuppressive M2 macrophage markers (CD206 and CD115) and decreased expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-4 in immune cells (Fig. 5B) (42, 43). In addition, flow cytometry analysis from the same mouse experiments showed that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment decreased M2 macrophages by fourfold and increased M1 macrophages by three- to fourfold in tumor tissues (Fig. 5, C to E, and fig. S12A). The immunofluorescence staining further demonstrated that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment induced the most efficient M2 to M1 macrophage repolarization in tumors in comparison with other treatment groups, where Nano-PI plus α-PD1–treated tumors had very low M2 macrophages as indicated by the minimal staining of M2 macrophage marker, but an increase of M1 macrophages in tumors (Fig. 5F). Moreover, Nano-PI treatment at a lower dose [Nano-PI, PTX (5 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (2.5 mg/kg)] was also confirmed to repolarize macrophages from M2 to M1 in orthotopic breast cancer using 4T1 breast cancer mice (fig. S13A) and MMTV-PyMT (fig. S12A).

Fig. 5. Nano-PI plus α-PD1 remolded tumor immune microenvironment in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.

(A) tSNE visualization and quantification of all immune cells in tumor by cytometry by time of flight (CyTOF) test from MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice 10 days after treatment with vehicle (IV), a combination of Nano-P (10 mg/kg, IV) and IPI-549 (5 mg/kg, IP) plus α-PD1, and Nano-PI (PTX, 10 mg/kg; IPI-549, 5 mg/kg) plus α-PD1 for five times and α-PD1 by IP at 100 μg per mouse for three times. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Relative gating scheme was shown in fig. S15, and the relative panels were listed in table S3. (B) tSNE visualization of the expression of CD206, CD115, IL-4, and IL-10 in tumor from MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice following the same treatment and CyTOF analysis in (A). (C to E) Flow cytometry quantification of M1 (F4/80+CD80+) and M2 (F4/80+CD206+) macrophage percentage among total macrophages and M1/M2 ratio in tumor of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice following the same treatment in (A). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). *P < 0.05. Statistically significant differences as compared with vehicle group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Representative images were shown in fig. S12A. (F) Confocal microscopic imaging shows the changes of macrophage phenotypes in tumor tissues after the same treatment in Fig. 4B. The total macrophages. M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, and nucleus were stained with F4/80 (red), CD80 (cyan), CD206 (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 400 μm.

In addition, we also analyzed the immune cell infiltration in tumors of PyMT mice by flow cytometry (2 million cells per sample) 10 days after the last treatment. Although drug treatments did not significantly change the total number of immune cells (CD45+) infiltrated in tumors, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 and the Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 treatments decreased macrophage infiltration to 20 and 17%, respectively, compared to 27% of macrophage infiltration in vehicle-treated group. Furthermore, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 and the Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 treatments increased T cell infiltration to 14 and 7.4%, respectively, compared to 2% in the vehicle-treated group. Last, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 and the Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 treatments increased B cell infiltration to 8.9 and 6.8%, respectively, compared to 3.2% in the vehicle-treated group (fig. S14).

To investigate how the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment altered T cell immunity in the tumors of both PyMT mice (Fig. 6A) and 4T1 orthotopic breast cancer mice (fig. S13, B and C), we first performed analysis of subtypes of T cells by CyTOF. The results revealed that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment resulted in a 6.6- and 11-fold increase of CD4+ T cells and a 2.5- and 3.4-fold increase of CD8+ T cells, compared to Nano-P combined with IPI-549, α-PD1, and vehicle treatment groups, respectively (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment decreased regulatory T cells (Tregs) in tumors by 20-fold (0.8%) compared with the vehicle group (19.5%) in PyMT mice. Similar results by flow analysis were also observed in orthotopic breast cancers using 4T1 cells (fig. S13C). Last, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment prevented T cell exhaustion in the tumor tissues confirmed by the decreased expression of exhaustion markers (CTLA-4, PD1, TIM-3, and FR4) (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6. Nano-PI plus α-PD1 prevents T cell exhaustion and activates DCs in tumors of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice.

(A) tSNE visualization of the expression of CTLA-4, PD1, TIM-3, and FR4 of T cells in tumor from MMTV-PyMT mice following the same treatment and CyTOF analysis as in (Fig. 5A). (B) tSNE visualization of the expression of CD103 in DCs in tumors from MMTV-PyMT mice following the same treatment and CyTOF analysis as in (Fig. 4A). (C) Representative flow cytometric images and quantification of DCs (CD11C+CD103+) and activated DCs (CD80+CD86+) in tumor of MMTV-PyMT mice. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). Statistically significant differences as compared with the vehicle group (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus vehicle, &P < 0.05). (D to F) ELISA analysis shows the granzyme B, IL-12, and IFN-γ in tumor of MMTV-PyMT mice with the same dosage regimen in (C). Data are means ± SD (n = 9). ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. Statistically significant differences as compared with the vehicle group (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

In addition, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment also increased the percentage of dendritic cells (DCs) among immune cells (Fig. 5A) and CD103+-positive DCs, which helped induce CD8+ T cell–mediated antitumor immunity (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, characterization of DCs in tumors by flow cytometry revealed that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment increased the total DC (CD11C+CD103+) population by 8.9 ± 2.0% compared to 3.2 ± 0.5% in vehicle-treated group. This treatment also elevated activated DC (CD80+CD86+) percentage by 1.7- to 3.8-fold compared with Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 and vehicle groups, which are crucial for T cell activation (Fig. 6B). Last, Nano-PI and α-PD1 treatment also increased the concentration of granzyme B, IL-12, and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) in tumors, indicating a high amount of activated antigen-presenting cells (DCs or macrophages) and the cytotoxic T cells (Fig. 6, D to F).

Fig. 7. Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 remodels the immune microenvironment in lymph nodes of PyMT mice.

(A) CyTOF analysis of all immune cells in lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT mice following the same treatment as in Fig. 6A. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Relative gating scheme was shown in fig. S15. (B to D) Flow cytometry quantification of M1 (F4/80+CD80+) and M2 (F4/80+CD206+) macrophage populations in lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice with the same dosage regimen as described in Fig. 6A. Data are means ± SD (n = 3). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01. Significant differences as compared with vehicle group (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). The flow cytometric images are in fig. S12B. (E) Whole–lymph node scanning by a Nikon A1 si confocal microscope shows the changes of macrophage phenotypes in lymph nodes following the treatment in Fig. 4B. The total macrophages, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, and nucleus were stained with F4/80 (red), CD80 (cyan), CD206 (green), and DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 400 μm. (F to H) ELISA analysis shows the amount of granzyme B, IL-12, and IFN-γ in the lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice following the treatment in Fig. 4B. Data are means ± SD (n = 4). &P < 0.05, &&P < 0.01, #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. Significant differences as compared with vehicle group (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 remodeled the immune microenvironment in lymph nodes by promoting M2 to M1 macrophage polarization, increasing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, increasing B cells, and decreasing TIM-3+ T cells

We next analyzed the immune cell subpopulation alterations in the lymph nodes of MMTV-PyMT mice 10 days after treatment by CyTOF and flow cytometry. The CyTOF analysis showed that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment decreased M2 macrophages frequency by 3-fold and increased M1 macrophages frequency by 2.5-fold compared to vehicle group (Fig. 7A). Flow cytometry analysis further confirmed these findings and showed a 5- to 14-fold decrease in M2 macrophages and a 2- to 3-fold increase in M1 macrophages from the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment compared to the Nano-P plus free IPI-549 treatment and vehicle control treatment (Fig. 7, B to D, and fig. S12B). In addition, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment increased CD4+ T and CD8+ T cell frequencies and decreased TIM-3–positive T cell frequency in the lymph nodes compared with both the Nano-P with IPI-549 and α-PD1 treatment and the vehicle treatment (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment also increased B cell frequency by more than twofold in the lymph nodes as compared to the other groups (Fig. 7A).

In addition, the total number of each immune cell subpopulation in lymph nodes of PyMT mice 10 days after treatment was also monitored using flow cytometry with 2 million cells from each sample. The data showed that the total number of each immune cell subpopulation in the lymph nodes was altered after treatment of Nano-PI plus α-PD1 compared to Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1 or vehicle treatments (fig. S16). Macrophage infiltration, as a percentage of total cells, was slightly decreased from 18.2% (control) to 16.4% (Nano-P, IPI, and α-PD1) and 12.2% (Nano-PI plus α-PD1) in the lymph nodes. T cell infiltration, as a percentage of total cells, was increased from 13.4% (control) to 18.9% (Nano-P, IPI, and α-PD1) and 24.4% (Nano-PI plus α-PD1) in the lymph nodes. Furthermore, B cell infiltration was also enhanced from 8.7% (control) to 13.9% (Nano-P, IPI, and α-PD1) and 16.5% (Nano-PI plus α-PD1) in the lymph nodes. Last, natural killer (NK) cell infiltration, as a percentage of total cells, was increased from 1.3% (control) to 4.0% (Nano-P, IPI, and α-PD1) and 5.0% (Nano-PI plus α-PD1) in the lymph nodes (fig. S16).

Furthermore, confocal microscopic images of the whole lymph node showed that the Nano-PI plus α-PD1 treatment decreased M2 macrophages and increased M1 macrophages as compared to other treatments and the vehicle treatment (Fig. 7E). Last, the Nano-PI plus α-PD1–treated group showed significantly increased (P < 0.05) antitumor cytokine production (granzyme B, IL-12, and IFN-γ) in the lymph nodes compared with the other treatment groups (Fig. 7, F to H). These results indicate that the Nano-PI with α-PD1 treatment successfully remodeled the microenvironment of lymph nodes that contributed to their anticancer efficacy in PyMT mice.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the combination of α-PD1/α-PDL1 immunotherapy and chemotherapy has been approved to treat metastatic breast cancer. However, the improvement in PFS time by 2 to 4 months in patients with TNBC is only marginal compared with chemotherapy alone (5, 6). In one such clinical trial, the PFS in pembrolizumab (α-PD1)–chemotherapy combination–treated patients was 9.7 months compared with PFS of 5.6 months in the chemotherapy only–treated group (5). Although the PFS in atezolizumab (α-PDL1) plus Abraxane–treated patients was 7.4 months compared to the PFS of 4.8 months in the Abraxane only–treated patients in the IMpassion130 trial (6, 7), the follow-up IMpassion131 trial using atezolizumab (α-PDL1) plus PTX failed to improve PFS compared to PTX alone in patients with TNBC (44). This led to the withdrawal of atezolizumab (α-PDL1) for the treatment of TNBC.

The immunosuppressive microenvironment in tumors may hinder the efficacy of α-PD1/α-PDL1 immunotherapy and chemotherapy (10-13). A clinical trial (MARIO-3) is ongoing to evaluate a PI3Kγ inhibitor (IPI-549) to improve the efficacy of atezolizumab (α-PDL1) and PTX albumin formulation (Nab-PTX, Abraxane) by remodeling the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment in patients with breast cancer. The initial results of this clinical study (MARIO-3) showed improvement of anticancer efficacy in the IPI-549 plus Nab-PTX and atezolizumab groups in 41 patients with TNBC compared to those of the atezolizumab plus Abraxane group (18). Although MARIO-3 and Impassion130 clinical studies were not designed for a head-to-head comparison, the efficacy improvements of IPI-549 plus Abraxane and atezolizumab groups in MARIO-3 are encouraging especially in the PDL-negative patients (6).

In a preclinical xenograft model, the combination of oral IPI-549 and α-PD1 inhibited tumor growth only for a short term, without complete eradication of the tumors (17). We observed similar improvements where the three-drug combination immunotherapy of α-PD1, IPI-549, and Nano-P showed better efficacy in delaying tumor growth than the two-drug combination immunotherapy of α-PD1 and Nano-P or α-PD1 and IPI-549 in PyMT transgenic mice (Fig. 4B). However, these combinations did not achieve complete remission (CR, 0%). In contrast, Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 treatment achieved complete tumor remission in all the mice (CR, 100%) and eliminated lung metastasis for 180 days in PyMT transgenic mice. Most treatment options rarely result in complete eradication of tumor growth and metastasis in aggressive metastatic breast cancer with long-term efficacy. The better efficacy of Nano-PI is a result of the enhanced delivery of both IPI-549 and PTX to macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumors, which results in complete remodeling of the immune microenvironment. Because PyMT transgenic mice with spontaneous cancer better mimic human metastatic breast cancer (32, 38, 45) than orthotopic or subcutaneous cancer models, the efficacy of Nano-PI and α-PD1 obtained using this model may have a better clinical translational potential and thus warrants future testing in clinical trials. In addition, because the Nano-PI formulation can be manufactured using an already established process used for Abraxane, it can be readily made available for clinical testing.

Reprograming the immunosuppressive microenvironment in both tumors and lymph nodes is critical for treating metastatic breast cancer (11, 14, 19, 20). However, previous efforts have mainly focused on the tumor site to improve the efficacy of immunotherapy and chemotherapy rather than targeting the immunosuppressive microenvironment in the lymph nodes (11, 19, 20). A recent study demonstrated that PD1/PDL1 interaction in tumor-draining lymph nodes, but not in tumor sites, correlated with prognosis in patients with melanoma, highlighting the importance of immune modulation in lymph nodes (46). Our data showed that immunosuppressive M2 macrophages infiltrated the lymph nodes of breast tumor–bearing mice (Fig. 1, A to C). Delivery of IPI-549 and PTX to macrophages in the lymph nodes and tumors contributed to the better efficacy of Nano-PI. In contrast, intravenous administration of both free drugs (IPI-549 and PTX) demonstrated limited drug accumulation in the macrophages of the tumor and lymph nodes, which exhibited much lower anticancer efficacy (Fig. 4, A to D). Nano-PI shifted the immune microenvironment from suppressive protumorigenic to immunogenic tumoricidal in the tumor and lymph nodes. We show that, compared with other treatment groups, Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 treatment promoted M2 to M1 macrophage polarization, increased CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, increased DCs, decreased Tregs, reduced T cell exhaustion, and enhanced production of antitumor cytokines (granzyme B, IL-12, and IFN-γ) (Figs. 5 to 7). Thus, these results suggest that simultaneous modulation of the immune microenvironment in both the tumor and lymph nodes is critical for long-term efficacy in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer.

More specifically, we hypothesized that both IPI-549 and PTX need to be delivered to macrophages in both tissues to remodel the lymph node and tumor microenvironment. Although various nanoformulations may increase the accumulation in TAMs after intravenous injection (47, 48), few reports show that nanoparticles can enhance drug accumulation in the macrophages of lymph nodes after intravenous administration (49). Many previous reports only explore nanomaterial’s lymph node targeting through the afferent lymph after intradermal or subcutaneous injection (49, 50). In this study, we demonstrated that intravenous administration of Nano-PI enhanced drug delivery not only to tumors but also to lymph nodes and predominantly the macrophages in these two tissues. The lymph node–homing property of albumin nanoparticles may be related to the albumin recycling properties, estimated at 97%, leading to their extravasation from blood circulation to the interstitium and then recycling back to blood circulation through the lymphatic system (51). This ability to accumulate in lymph nodes combined with the tumor-homing ability of Nano-PI, combined with α-PD1, resulted in complete long-term tumor remission (CR, 100%). In contrast, the combination of these two free drugs with α-PD1 produced much weaker anticancer efficacy (CR, 0%).

There are several limitations in our study. Because albumin nanoparticles could not encapsulate IPI-549 alone (Nano-I), it is not feasible to compare the combination of Nano-I and Nano-P with Nano-PI. Therefore, it is not clear whether the co-delivery of IPI-549 and PTX is necessary, although MS imaging showed that some colocalization of these two drugs in tumors and lymph nodes suggests that this is the case (fig. S7). In addition, although Nano-PI increased the drug delivery to macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumors, the mechanism of delivery for albumin nanoparticles is unclear and requires further investigation. Furthermore, although Nano-PI clearly altered the immune microenvironment in both lymph nodes and tumors, more mechanistic investigation is required to elucidate the interplay between the immune microenvironment in the lymph nodes and tumors during tumor progression and metastasis. This investigation would improve the antitumor efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with metastatic breast cancer.

In the past few decades, anticancer nanomedicines were designed by using the enhanced permeability and retention effect in tumors and long systemic circulation. However, a poor clinical translation of those nanomedicines’ efficacy from preclinical xenograft models to patients with cancer has been debated (37, 52, 53). In this study, we used different design criteria to devlop a nanomedicine (Nano-PI), which is drug specific, nanocarrier specific, target cell specific, and disease specific. Nano-PI overcame the limitation of low accumulation of IPI-549 and PTX in the macrophages of lymph nodes and tumors. This was achieved because albumin nanoparticles can deliver drugs into the macrophages of these two tissues. Specifically, Nano-PI was able to target M2 macrophages, which are one of the major immunosuppressive factors that require regulation to treat metastatic breast cancer. This nanoparticle design, as shown in Nano-PI, may enhance immunotherapy efficacy of αPD1/PDL1 to achieve long-term complete tumor remission and shows promise at providing better clinical translation in patients with cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The objective of our study was to use nanomedicine to deliver immunomodulators to macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumor sites to remodel the immunosuppressive microenvironment for immunotherapy of metastatic breast cancer in combination with α-PD1. We screened and optimized the IPI-549 and PTX based on macrophage repolarization potential and tumor growth inhibition property and then prepared the albumin-based nanomedicine Nano-PI for co-delivery of IPI-549 and PTX to macrophages in both lymph nodes and tumors, which were evaluated by in vivo pharmacokinetics, flow cytometric analysis, and confocal imaging in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice (n = 3 to 4 mice per group). The antitumor efficacy of Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 was evaluated in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice with spontaneous metastatic breast cancer (n = 10 replicates per group) and an orthotopic 4T1 xenograft breast cancer mouse model (n = 8 replicates per group). Then, the immune cell profilings of microenvironment in tumors and lymph nodes (n = 3 to 9 mice per group) were investigated by CyTOF, flow cytometry analysis, confocal imaging, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Furthermore, we rechallenged the Nano-PI plus α-PD1-treated PyMT mice (n = 4 mice per group) by reinoculation of PyMT cancer cells and showed the potential of the formulation to impart long-term memory immune cells. Mice were randomly assigned to different treatment groups without blinding, and tumor size was monitored using a vernier caliper. The number of replicates for each experiment is presented in the figure legends. Animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Michigan.

Preparation and characterization of Nano-PI

PTX (12 mg) and IPI-549 (8 mg) were dissolved in 1 ml of chloroform and then added dropwise into 100 mg of mouse serum albumin dissolved in 20 ml of Milli-Q water to generate a milky emulsion using a rotor-stator homogenizer. The Nano-PI nanosuspension was obtained after running five to six cycles at 30,000 psi on a high-pressure homogenizer (Nano DeBEE) at 4°C. The organic solvent was removed using a rotary evaporator at 25°C. After filtering (0.22 μm), the Nano-PI suspension was lyophilized and stored at −20°C. Nano-P was prepared following the same procedures but with a PTX–to–mouse albumin ratio of 1:5. The size distribution and morphology were measured by dynamic light scattering and JEOL2010F transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The drug concentration in Nano-PI was detected by LC-MS/MS. The encapsulation efficiency (EE), drug loading capacity (DL), and drug recovery yield (Y) were calculated by the following equations

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where Wd represents the amount of drug in Nano-PI suspension, Wf represents the amount of free drug, Wn represents the amount of Nano-PI suspension, Wt represents the total amount of drug in the Nano-PI suspension after the process, and Wa represents the total drug added. The free drug was separated from Nano-PI formulation by a Nanosep centrifugal device [molecular weight-cutoff (MWCO), 3 kDa] with a centrifugation speed of 10,000 rpm/min for 10 min.

Macrophage polarization

BMDMs were isolated from the femurs and tibias of BALB/c mice (female, 7 weeks old). Briefly, after euthanizing the mice, the femurs and tibia of the hind legs were collected, and the bone marrow cells were gently flushed with precooled RIPA 1640. After centrifugation, cells were resuspended in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 2 mM l-glutamine, 10% FBS, macrophage colony-stimulating factor (10 ng/ml; PeproTech Inc.), penicillin (50 U/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml) and seeded into sterile plastic petri dishes (10 ml) at a density of 5 × 106 cells per dish. The medium was replaced on day 3, and on day 7, the BMDM cells were harvested and used for further experiments. BMDM and RAW 264.7 cells were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (100 ng/ml), IFN-γ (50 ng/ml), IL-4 (20 ng/ml), and IL-13 (10 ng/ml) to generate M1/M2 macrophages (54). Macrophage morphology was observed using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus). In addition, the cells and the supernatant medium in each well were collected; the expression of CD80, inducible nitric oxide synthase (INOS), and CD206 was separately measured using Western blotting; and the secretion of cytokines, including TNF-α, TGF-β, IL-12, and IL-10, was detected by ELISA.

3D MTCs

4T1 cells and M2 macrophages derived from RAW264.7 cells were mixed in the ratio of 7:3 and then seeded into an ultralow-attachment 96-well plate (Corning) at a density of 5000 cells per well and cultured for 30 hours to form the tumor spheroids. These tumor spheroids were separately incubated with 300 μl of complete medium supplemented with PTX (5 μm), gemcitabine (5 μM), doxorubicin (5 μM), and IPI-549 (5 μM), as well as the combination of IPI-549 and PTX (2.5 μM + 2.5 μM), IPI-549 and gemcitabine (2.5 μM + 2.5 μM), and IPI-549 and doxorubicin (2.5 μM + 2.5 μM) for 14 days. The volumes ([major axis] × [minor axis]2/2) of the MTCs were monitored every other day using an Olympus IX83 motorized inverted microscope with cellSens Dimension software (Olympus), and images were captured using the CellInsight CX5 High-Content Screening Platform (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at ×4 magnification.

Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of PTX and IPI-549 delivered by Nano-PI in MMTV-PyMT mice

PyMT mice (female, 14 to 15 weeks old) with 10 to 16 spontaneous tumors each were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 12) and administered the following formulations: PTX/IPI-54 (IV), Nano-P (IV) plus IPI-549 (PO), Nano-P (IV) plus IPI-549 (IP), or Nano-PI (IV) at the PTX and IPI-549 dosage of 5 and 2.5 mg/kg, respectively. PTX and/or IPI-549 were dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400 and mixed with 50% sterile saline (0.9%, w/v), and Nano-P and Nano-PI were suspended in sterile saline. Blood was collected at 0.5, 4, 7, and 24 hours after administration, and plasma was isolated after centrifugation (13,300 rpm for 10 min). Subsequently, mice were euthanized, and major organs including the liver, spleen, lung, lymph node, fat pad, and tumor were collected, weighed, and homogenized. For accurate detection of drug distribution, we randomly dissected 10 tumors and 8 fat pads at different locations from each mouse. Subsequently, the contents of PTX and IPI-549 in the tissue homogenate and plasma were detected by LC-MS using an ABI-5500 Qtrap (Sciex) mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization source, which was interfaced with a Shimadzu high-performance liquid chromatography system with an Xbridge C18 column (50 × 2.1 mm L × I.D., 3.5 μm). Results are represented as the amount of PTX or IPI-549 normalized per gram per milliliter of tissue.

Anticancer efficacy in MMTV-PyMT transgenic mice

PyMT mice (9 to 10 weeks old) with spontaneous tumors were randomly assigned to six groups (n = 17), and the total tumor size of each group was in the range of 80 to 110 mm3. The mice were then treated with vehicle, Nano-P, Nano-P plus α-PD1, IPI-549 plus α-PD1, Nano-P plus IPI-549 and α-PD1, and Nano-PI and Nano-PI plus α-PD1. IPI-549 was dissolved in 10% DMSO in 40% PEG 400, mixed with 50% sterile saline, and orally administered daily at 15 mg/kg or injected intraperitoneally at 5 mg/kg every 3 days. Nano-P and Nano-PI suspended in sterile saline were intravenously administered at PTX and IPI-549 dosages of 10 and 5 mg/kg, respectively. α-PD1 (100 μg per mouse) was administered (IP) on days 66, 69, and 72 after birth. To assess the advanced properties of Nano-PI–mediated oncotherapy, PyMT mice (11 to 12 weeks old) with an average tumor size of 150 mm3 were randomly assigned to three groups (n = 17) and then intravenously administered with the vehicle, PTX/IPI-549 (dissolved in 10% DMSO + 40% PEG 400 + 50% sterile saline), and Nano-PI at the PTX and IPI-549 dosage of 5 and 2.5 mg/kg, respectively. Body weight, tumor number, and tumor volume were measured and recorded every 3 days. Three (normal dose batch)/4 days (half dose batch) after the last administration, three mice from each group were euthanized, and the tumor and lymph nodes were collected for flow cytometry analysis. On days 85 (normal dose batch) and 111 (half dose batch), another four mice from each group were euthanized, and the lungs were harvested, washed, and fixed in the Bosin fixative (Sigma-Aldrich). After repeated rinsing, lung organs with metastatic tumor nodules were photographed. Then, the excised lung organs were fixed, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), followed by imaging using an inverted fluorescence microscope to investigate further inhibition of tumor lung metastasis.

Antitumor efficacy in 4T1 orthotopic breast cancer mice

An orthotopic breast cancer model was established in female BALB/c mice. Briefly, 4T1 cells and M2 macrophages (viabilities >96%) derived from RAW 264.7 cells were mixed (3:1, rat) and injected into the mammary fat pad of mice (5 × 107 cells/ml). When tumor sizes reached ~120 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to seven groups (n = 11) and received different treatments. The administration was performed as a single treatment or combined with the following regimen for each drug three times. IPI-549 was dissolved in 10% DMSO in 40% PEG 400, mixed with 50% sterile saline, and orally administered daily or injected intraperitoneally at 5 mg/kg. Nano-P and Nano-PI were dissolved in sterile saline and intravenously administered at the PTX and IPI-549 dosages of 10 and 5 mg/kg. Anti-PD1 antibodies (α-PD1) (100 μg per mouse) were administered (IP) on days 5, 8, and 11 after tumor inoculation. Body weights and tumor volumes ([long axis] × [short axis]2/2) were measured and recorded every 3 days. Three days after the last administration, three mice from each group were euthanized, and the tumor and lymph nodes were collected for flow cytometry. Thirteen days after the last administration, all the mice were sacrificed, and the tumors were dissected, weighed, photographed, and stored at −80°C. The tumor inhibition ratio (TIR) was calculated using the following equation: (1 – Wa/Wv) × 100%, where Wa and Wv represent average tumor weights of the administration groups and vehicle groups, respectively. For histological testing, lung tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; w/v), and paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) were prepared. After staining with H&E, breast cancer lung metastasis was analyzed by inverted fluorescence microscopy.

FACS of immune cells in tumors and lymph nodes

PyMT mice (15 weeks old) with more than 10 tumors were euthanized, and the tumors were dissected for preparation of single-cell suspension following the method mentioned above. The cells were then washed, counted, and incubated with SYTOX Green (30 nM) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, the live cells (negative) were sorted out and collected using a Sony MA900 sorter equipped with lasers of 488-nm excitation and 530/30 bandpass.

Tumor rechallenge study in PyMT transgenic mice with tumor remission

The live cells were sorted using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) from single-cell suspensions isolated from PyMT mouse tumors. Then, 100 μl of single-cell suspension (5 × 106 cells/ml) was implanted into the mammary fat pad of FVB/NJ female mice and PyMT mice 132 days after the last administration of Nano-PI combined with α-PD1 (210 days after birth). After 8 days, tumor volumes were measured and recorded every 4 days for the first three times and then changed every 3 days in the following days. At the end, the mice were euthanized, and the lymph nodes, spleen, lung, bone marrow, and blood were collected to prepare single-cell suspensions using the aforementioned methods. The memory T cells and B cells in the lymph nodes, spleen, lung, bone marrow, and blood of PyMT and FVB/NJ mice were detected by flow cytometry analysis.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions obtained from the fat pad, lymph node, tumor, spleen, lung, blood, and bone marrow of the PyMT mice, FVB/NJ mice, and BALB/c mice were incubated with Fc receptor–blocking reagent (BD Biosciences) for 15 min at 4°C and then stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies with appropriate dilutions including anti-CD44–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-F4/80–Pacific Blue, anti-CD31–Spark YG 570, anti-CD45–Spark blue 550, anti-CD45–Pacific Blue, anti-F4/80–phycoerythrin (PE), anti-CD169-PE, anti-CD3–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD3–Spark blue 550, anti-CD19–PE, anti-CD103–Pacific Blue, anti-CD103–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD19–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD335–PE/Dazzle 594, anti-CD103–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD11C–Pacific Blue, anti-CD80–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD80–Spark blue 550, anti-F4/80–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD11b–Alexa Fluor 594, anti-CD169–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD206–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD80–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD206–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD86–PE/Dazzle, anti-CD3–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD19–PE, anti-CD197–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD44–Pacific Blue, anti-CD80–Alexa Fluor 594, anti-CD103–Alexa Fluor 594, anti-CD73–Pacific Blue, anti-PDL2–allophycocyanin (APC)–633, anti-CD3–Spark YG570, anti-CD19–Brilliant violet 421, anti-CD8–Alexa Fluor 594, anti-CD4–Alexa Fluor 532, and anti-CD3–Alexa Fluor 594 for 30 min on ice. All antibodies were purchased from BioLegend, eBioscience, and R&D Systems. For intracellular staining, cells were fixed, permeabilized with permeabilization staining buffer (eBioscience), and then incubated with anti-FoxP3–Alexa Fluor 647. The stained cells were acquired on the Bio-Rad ZE5 Flow Cytometer equipped with four lasers (405, 488, 561, and 640 nm) and 21 fluorescent detectors using BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). All data analyses were performed using the flow cytometry analysis program FCS Express 7 (De Novo Software). Dead cells and doublets were excluded on the basis of forward and side scatter and fixable viability dye.

Confocal microscopy

The tumor and lymph nodes were dissected from PyMT mice (14 weeks old), and cryosections (10 μm thick) were prepared for staining of M2 macrophages. Subsequently, the sections were fixed and preincubated with 5% FBS for 30 min at room temperature, incubated with anti-F4/80–Alexa Fluor 647 and anti-CD206–fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) for 12 hours at 4°C, mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Molecular Probes, P36971), and imaged using a Nikon A1Si confocal microscope equipped with 405-, 488-, 561-, and 640-nm lasers. Nano-PI encapsulating the Oregon Green 488–labeled PTX and IPI-549 was prepared following a similar method for drug distribution. PyMT mice (13 weeks old) were intravenously administered Nano-PI at dosages of Oregon Green 488–labeled PTX (50 mg/kg) and IPI-549 (25 mg/kg). At 5 hours after administration, the tumor and lymph node were dissected to obtain cryosections and incubated with the following antibodies: anti-F4/80–Alexa Fluor 647, anti-CD206–Alexa Fluor 488, anti-CD80–Alexa Fluor 594, anti-CD31–Spark YG 570, anti-CD3–Spark YG570, anti-CD19–Brilliant Violet 421, and anti-CD45R/B220–Brilliant Violet 421 for 12 hours at 4°C. The tumor and lymph node sections were mounted in ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant with DAPI (Molecular Probes) and ProLong Diamond Antifade Mountant (Molecular Probes, P36961), respectively. The drug distribution mediated by Nano-PI was analyzed using a Nikon A1Si confocal microscope.

CyTOF analysis of all immune cells in tumor tissues and lymph nodes

The immune profiles of the tumor and lymph nodes were detected using CyTOF analysis. Single-cell suspensions (3 million cells) of tumors and lymph nodes from PyMT mice treated with different formulations were prepared and then fixed and stained for CyTOF analysis as described previously using an optimized cocktail of 40 metal-conjugated antibodies designed to identify the changes in cell subsets within tumors and lymph nodes. CyTOF antibody conjugation and data acquisition were performed as described previously (55). Briefly, antibodies were conjugated to lanthanide metals (Fluidigm) using the Maxpar Antibody Labeling Kit (Fluidigm). Single-cell suspensions prepared from PyMT mouse tumor and lymph node samples were prepared as described above. Unstimulated cell suspensions were washed once with heavy metal–free PBS and stained with 1.25 μM Cell-ID Cisplatin-195Pt (Fluidigm) at room temperature for 5 min. Fc receptors were blocked with TruStain FcX (anti-mouse CD16/32, BioLegend), and surface staining was performed on ice for 60 min in heavy metal–free PBS with 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.05% sodium azide. The cells were then fixed with 1.6% PFA for 20 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with Invitrogen permeabilization buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at room temperature before intracellular antibody staining at room temperature for 60 min in permeabilization buffer. Cells were left in 62.5 nM Cell-ID Intercalator Iridium-191/193 (Fluidigm) in 1.6% PFA in PBS overnight at 4°C until ready for acquisition on a CyTOF Helios system (Fluidigm). A signal-correction algorithm based on the calibration bead signal was used to correct for any temporal variation in the detector sensitivity. Data were acquired on a CyTOF Helios system (Fluidigm), and cell populations were analyzed by gating with FlowJo/FCS Express software. Cell populations were analyzed by gating with FlowJo/FCS Express software. Global analysis using t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) was performed for unsupervised clustering analysis based on the expression of marked genes in different subsets of immune cells.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were carried out in triplicates unless otherwise noted specifically, and all results are represented as means ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s unpaired t test for comparisons between two groups, and multiple comparisons were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Bonferroni test (SPSS software, version 12.0, SPSS Inc.). All statistical analyses were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 and OriginPro 8 software, and statistical significance is annotated as P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Funding:

This work was supported, in part, by the internal founding of College of Pharmacy at University of Michigan.

Footnotes

Competing interests: A patent application entitled “PI3K inhibitors, nanoformulations, and uses thereof” (63/176,930) related to this study has been filed. Y.S., L.B., F.W., W.G., H.H., R.L., and D.S. are inventors of the patent. The other authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are present in the paper or the Supplementary Materials. Materials can be made available through a material transfer agreement with D.S.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F, Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin 71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J. Clin 71, 7–33 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riggio AI, Varley KE, Welm AL, The lingering mysteries of metastatic recurrence in breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 124, 13–26 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eng LG, Dawood S, Sopik V, Haaland B, Tan PS, Bhoo-Pathy N, Warner E, Iqbal J, Narod SA, Dent R, Ten-year survival in women with primary stage IV breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 160, 145–152 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes J, Cescon DW, Rugo HS, Nowecki Z, Im SA, Yusof MM, Gallardo C, Lipatov O, Barrios CH, Holgado E, Iwata H, Masuda N, Otero MT, Gokmen E, Loi S, Guo Z, Zhao J, Aktan G, Karantza V, Schmid P; KEYNOTE- Investigators, Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy versus placebo plus chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (KEYNOTE-355): A randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 396, 1817–1828(2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, Schneeweiss A, Barrios CH, Iwata H, Diéras V, Hegg R, Im S-A, Shaw Wright G, Henschel V, Molinero L, Chui SY, Funke R, Husain A, Winer EP, Loi S, Emens LA, Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 379, 2108–2121 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FDA lable. TECENTRIQ· (atezolizumab) injection, for intravenous use. Initial U.S. Approval: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emens LA, Breast cancer immunotherapy: Facts and hopes. Clin. Cancer Res 24, 511–520(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binnewies M, Roberts EW, Kersten K, Chan V, Fearon DF, Merad M, Coussens LM, Gabrilovich DI, Rosenberg SO, Hedrick CC, Vonderheide RH, Pittet MJ, Jain RK, Zou W, Howcroft TK, Woodhouse EC, Weinberg RA, Krummel MF, Understanding the tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) for effective therapy. Nat. Med 24, 541–550 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiu SQ, Waaijer SJH, Zwager MC, de Vries EGE, van der Vegt B, Schroder CP, Tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: Innocent bystander or important player? Cancer Treat. Rev 70, 178–189 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doak GR, Schwertfeger KL, Wood DK, Distant relations: Macrophage functions in the metastatic niche. Trends Cancer 4, 445–459 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Green MD, Li S, Sun Y, Journey SN, Choi JE, Rizvi SM, Qin A, Waninger JJ, Lang X, Chopra Z, El Naqa I, Zhou J, Bian Y, Jiang L, Tezel A, Skvarce J, Achar RK, Sitto M, Rosen BS, Su F, Narayanan SP, Cao X, Wei S, Szeliga W, Vatan L, Mayo C, Morgan MA, Schonewolf CA, Cuneo K, Kryczek I, Ma VT, Lao CD, Lawrence TS, Ramnath N, Wen F, Chinnaiyan AM, Cieslik M, Alva A, Zou W, Liver metastasis restrains immunotherapy efficacy via macrophage-mediated T cell elimination. Nat. Med 27, 152–164 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngambenjawong C, Gustafson SH, Pun SH, Progress in tumor-associated macrophage (TAM)-targeted therapeutics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 114, 206–221 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantovani A, Marchesi F, Malesci A, Laghi L, Allavena P, Tumour-associated macrophages as treatment targets in oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 14, 399–416 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long GV, Dummer R, Hamid O, Gajewski TF, Caglevic C, Dalle S, Arance A, Carlino MS, Grob JJ, Kim TM, Demidov L, Robert C, Larkin J, Anderson JR, Maleski J, Jones M, Diede SJ, Mitchell TC, Epacadostat plus pembrolizumab versus placebo plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma (ECHO-301/KEYNOTE-252): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Oncol. 20, 1083–1097 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneda MM, Messer KS, Ralainirina N, Li H, Leem CJ, Gorjestani S, Woo G, Nguyen AV, Figueiredo CC, Foubert P, Schmid MC, Pink M, Winkler DG, Rausch M, Palombella VJ, Kutok J, McGovern K, Frazer KA, Wu X, Karin M, Sasik R, Cohen EEW, Varner JA, PI3Kγ is a molecular switch that controls immune suppression. Nature 539, 437–442 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Henau O, Rausch M, Winkler D, Campesato LF, Liu C, Cymerman DH, Budhu S, Ghosh A, Pink M, Tchaicha J, Douglas M, Tibbitts T, Sharma S, Proctor J, Kosmider N,White K, Stern H, Soglia J, Adams J, Palombella VJ, McGovern K, Kutok JL, Wolchok JD,Merghoub T, Overcoming resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy by targeting PI3Kγ in myeloid cells. Nature 539, 443–447 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eganelisib re-programming macrophages to develop best-in-class next-generation immunotherapy for patients with frontline metastatic TNBC, December 10,2021, Infinity Pharmaceuticals SABCS Presentation; https://investors.infi.com/static-files/db444844-59dc-406d-a9ee-f6b8640b8c55. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotman J, Koster BD, Jordanova ES, Heeren AM, de Gruijl TD, Unlocking the therapeutic potential of primary tumor-draining lymph nodes. Cancer Immunol. Immunother 68, 1681–1688 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andorko JI, Hess KL, Jewell CM, Harnessing biomaterials to engineer the lymph node microenvironment for immunity or tolerance. AAPSJ. 17, 323–338 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaahtomeri K, Alitalo K, Lymphatic vessels in tumor dissemination versus immunotherapy. Cancer Res. 80, 3463–3465 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cochran AJ, Huang RR, Lee J, Itakura E, Leong SP, Essner R, Tumour-induced immune modulation of sentinel lymph nodes. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6, 659–670 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira ER, Jones D, Jung K, Padera TP, The lymph node microenvironment and its role in the progression of metastatic cancer. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol 38, 98–105 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones D, Pereira ER, Padera TP, Growth and immune evasion of lymph node metastasis. Front. Oncol 8, 36 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swartz MA, Lund AW, Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: Linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 210–219 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linde N, Casanova-Acebes M, Sosa MS, Mortha A, Rahman A, Farias E, Harper K, Tardio E, Reyes Torres I, Jones J, Condeelis J, Merad M, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Macrophages orchestrate breast cancer early dissemination and metastasis. Nat. Commun 9, 21 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wehrhan F, Büttner-Herold M, Hyckel P, Moebius P, Preidl R, Distel L, Ries J, Amann K, Schmitt C, Neukam FW, Weber M, Increased malignancy of oral squamous cell carcinomas (oscc) is associated with macrophage polarization in regional lymph nodes—An immunohistochemical study. BMC Cancer 14, 522 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Go Y, Tanaka H, Tokumoto M, Sakurai K,Toyokawa T, Kubo N, Muguruma K, Maeda K, Ohira M, Hirakawa K, Tumor-associated macrophages extend along lymphatic flow in the pre-metastatic lymph nodes of human gastric cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol 23 Suppl 2, S230–S235 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaewkangsadan V, Verma C, Eremin JM, Cowley G, Ilyas M, Satthaporn S, Eremin O, The differential contribution of the innate immune system to a good pathological response in the breast and axillary lymph nodes induced by neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with large and locally advanced breast cancers. J. Immunol. Res 2017, 1049023 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurahara H, Takao S, Maemura K, Mataki Y, Kuwahata T, Maeda K, Sakoda M, Iino S, Ishigami S, Ueno S, Shinchi H, Natsugoe S, M2-polarized tumor-associated macrophage infiltration of regional lymph nodes is associated with nodal lymphangiogenesis and occult nodal involvement in pN0 pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 42, 155–159 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Wang J, Yang C, Wang Y, Liu J, Shi Z, Chen Y, Feng Y, Ma X, Qiao S, A study of the correlation between M2 macrophages and lymph node metastasis of colorectal carcinoma. World J. Surg. Oncol 19, 91 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fantozzi A, Christofori G, Mouse models of breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 8, 212(2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larionova I, Cherdyntseva N, Liu T, Patysheva M, Rakina M, Kzhyshkowska J, Interaction of tumor-associated macrophages and cancer chemotherapy. Onco. Targets Ther 8, 1596004(2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Volk-Draper L, Hall K, Griggs C, Rajput S, Kohio P, DeNardo D, Ran S, Paclitaxel therapy promotes breast cancer metastasis in a TLR4-dependent manner. Cancer Res 74, 5421–5434 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cullis J, Siolas D, Avanzi A, Barui S, Maitra A, Bar-Sagi D, Macropinocytosis of Nab-paclitaxel drives macrophage activation in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res 5, 182–190 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wanderley CW, Colon DF, Luiz JPM, Oliveira FF, Viacava PR, Leite CA, Pereira JA, Silva CM, Silva CR, Silva RL, Speck-Hernandez CA, Mota JM, Alves-Filho JC, Lima-Junior RC, Cunha TM, Cunha FQ, Paclitaxel reduces tumor growth by reprogramming tumor-associated macrophages to an M1 profile in a TLR4-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 78, 5891–5900 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luan X, Yuan H, Song Y, Hu H, Wen B, He M, Zhang H, Li Y, Li F, Shu P, Burnett JP, Truchan N, Palmisano M, Pai MP, Zhou S, Gao W, Sun D, Reappraisal of anticancer nanomedicine design criteria in three types of preclinical cancer models for better clinical translation. Biomaterials 275, 120910 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenow KR, Smalley MJ, Overview of genetically engineered mouse models of breast cancer used in translational biology and drug development. Curr. Protoc. Pharmacol 70, 14.36.11–14.36.14 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maglione JE, Moghanaki D, Young LJ, Manner CK, Ellies LG, Joseph SO, Nicholson B, Cardiff RD, MacLeod CL, Transgenic polyoma middle-T mice model premalignant mammary disease. Cancer Res. 61, 8298–8305 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fluck MM, Schaffhausen BS, Lessons in signaling and tumorigenesis from polyomavirus middle T antigen. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 73, 542–563 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]