Abstract

Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is a cytoprotective protein for the retina. We hypothesize that this protein acts on neuronal survival and differentiation of photoreceptor cells in culture. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the neurotrophic effects of PEDF and its fragments in an in vitro model of cultured primary retinal neurons that die spontaneously in the absence of trophic factors. We used Wistar albino rats. Cell death was assayed by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry through TUNEL assay, propidium iodide, mitotracker, and annexin V. Immunofluorescence of cells for visualizing rhodopsin, CRX, and antisyntaxin under confocal microscopy was performed. Neurite outgrowth was also quantified. Results show that PEDF protected photoreceptor precursors from apoptosis, preserved mitochondrial function and promoted polarization of opsin enhancing their developmental process, as well as induced neurite outgrowth in amacrine neurons. These effects were abolished by an inhibitor of the PEDF receptor or receptor-derived peptides that block ligand/receptor interactions. While all the activities were specifically conferred by short peptide fragments (17 amino acid residues) derived from the PEDF neurotrophic domain, no effects were triggered by peptides from the PEDF antiangiogenic region. The observed effects on retinal neurons imply a specific activation of the PEDF receptor by a small neurotrophic region of PEDF. Our findings support the neurotrophic PEDF peptides as neuronal guardians for the retina, highlighting their potential as promoters of retinal differentiation, and inhibitors of retinal cell death and its blinding consequences.

Keywords: amacrine, apoptosis, PEDF, photoreceptors, retina, rhodopsin

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The importance of pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), as both a neurotrophic factor and an antiangiogenic agent, for the retina has been well-documented (Barnstable and Tombram-Tink, 2004; Bouck, 2002; Becerra and Notario 2013; Polato & Becerra, 2016). Moreover, its deficiency is associated with progression of retinodegenerative diseases, such as retinitis pigmentosa, age-related macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy (Holekamp et al., 2002; Ogata et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2006).

PEDF is a glycoprotein and a member of the superfamily of serine protease inhibitors (SERPIN) that belongs to the subgroup of ‘non-inhibitory’ serpins (Becerra et al., 1995; Steele et al., 1993). The monolayer of cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) secretes PEDF in an apicolateral fashion to be deposited in the interphotoreceptor matrix where it acts on survival of PHRs and is responsible for its avascularity (Tombran-Tink et al., 1995; Dawson et al., 1999; Becerra et al., 2004; Cai et al., 2006; Michalczyk et al., 2018). We have mapped the regions that confer the neurotrophic and antiangiogenic activities to the multifunctional PEDF polypeptide. The region spanning between amino acid residue positions 44–77 of the human sequence, termed 34-mer, contains the antiangiogenic domain, while a region spanning between positions 78–121, 44-mer, contains the neurotrophic domain (Becerra, 2006). Furthermore, a smaller synthetic mimotope, the 17-mer peptide (98–115 positions), designed from the 44-mer peptide, recapitulates the neurotrophic properties of the full-length PEDF protein of about 398 residues (Kenealey et al., 2015; Valiente-Soriano et al., 2020). The distinct 34-mer peptide is an antiangiogenic mimotope of PEDF devoid of neurotrophic activity (Amaral & Becerra, 2010; Becerra et al., 1995). PEDF elicits its cytoprotective effects by binding and activating its receptor PEDF-R (Notari et al., 2006). Retinal cells express the gene for PEDF-R termed patatin-like phospholipase-2 (Pnpla2) (Notari et al., 2006). The pattern of Pnpla2 expression in the mouse retina by laser capture microdissection reveals that the different layers of the retina express this gene (Dixit et al., 2020). In the albino rat, retina PEDF-R distributes at higher levels in the inner segments of PHRs than in the rest of the tissue (Notari et al., 2006; Subramanian et al., 2010). The PEDF-R protein, also known as calcium-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2), is an enzyme with phospholipase A2 activity that liberates fatty acids and lyso-phospholipids from phospholipids (Jenkins et al., 2004; Notari et al., 2006). Specifically, it hydrolyzes the sn-2 acyl bond of phospholipids, thus releasing polyunsaturated fatty acids, preferentially docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) (Pham et al., 2017). While PEDF binding stimulates the PEDF-R enzymatic activity (Notari et al., 2006), its inhibition by the selective PEDF-R inhibitor atglistatin abolishes the PEDF survival effects in retinal R28 cells (Kenealey et al., 2015). Interestingly, the phospholipase A2 inhibitor bromoenol lactone (BEL) inhibits PEDF-R activity, blocks the PEDF-mediated survival effects on serum-starved retinal R28 cells and hinders DHA-mediated prevention of oxidative-stress-induced apoptosis of PHRs in vitro (German et al., 2013; Subramanian et al., 2013). These similarities imply a direct action of PEDF on PHRs, likely via stimulation of PEDF-R to generate DHA as its neurotrophic lipid mediator. However, the direct effects of PEDF on PHRs and its mechanism of action on PHR development are unknown.

Most of the research to evaluate the effects of PEDF on PHRs has been performed in animal models of retinal degeneration in vivo (Polato & Becerra, 2016). However, the complexity of the interactions that occur in the native retina makes it difficult to evaluate the subcellular changes involved in biochemical pathways triggering the PEDF effects on PHRs, which remain to be elucidated. Purified neuronal retinal cultures are ideal to perform these types of studies. We have previously established primary cultures of purified neurons enriched in PHRs and amacrine neurons cultured in a complete chemically defined medium (Politi et al., 1988). As it occurs in vivo, in the absence of their specific trophic factors, PHRs in these cultures undergo a developmental programmed cell death (Politi et al., 1988). Conversely, addition of growth factors, such as glial-derived factor (GDNF) (Politi et al., 2001a), fibroblast growth factor (FGF) (Fontaine et al., 1998), or the lipid molecule docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) reverses this process to prevent death of PHRs in culture (Politi et al., 2001b). In addition to protecting PHRs against death by apoptosis, DHA promotes their differentiation in these cultures (Rotstein et al., 1997, 1998). However, the neurotrophic potential of PEDF has not yet been tested in this primary cell culture system.

Using neuronal retinal cell cultures, we examined the effects of PEDF on PHR development and survival. Here, we provide evidence that PEDF and its 17-mer, and 44-mer–derived peptides protect PHRs, promote their differentiation and stimulate axonal outgrowth, selectively in amacrine cells. We discuss how the findings provide a more comprehensive view of the intracellular molecular events elicited by PEDF and its derived peptides on isolated PHRs and amacrine neurons in vitro.

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Protein, peptides, and reagents

Recombinant human PEDF was produced and purified as outlined previously (Stratikos et al., 1996). Human PEDF-R peptide P1 and human PEDF peptides 34-mer, 44-mer, and 17-mer were synthesized as described (Kenealey et al., 2015) (see Table 1). Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium (DMEM) (31600034), Hanks’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) (14170112), trypsin (15090046), gentamicin (15750060), distilled water (15230147), and penicillin-streptomycin (15140122) were from Gibco (US). Poly-ornithine (P3655), insulin (I4011), trypsin inhibitor (T6522), hydrocortisone (H0888), putrescine (P5780), apotransferrine (T1147), CDP-coline (90756), CDP-ethanolamine (C0256), progesterone (P8783) were from Sigma (US).

Table 1: Peptide sequence.

Protein sequences of the peptide fragments used in this paper.

| P1 | TSIQFNLRNLYRLSKALFPPEPLVLREMCKQGYRDGLRFL |

| 34-mer | FFVPVNKLAAVSNFGYDLYRVRSSMSPTTN |

| 44-mer | VLLSPLSVATALSALSLGADQRTESIIHRALYYDLISSPDIHGT |

| 17-mer | QRTESIIHRALYYDLIS |

2.2 |. Animals

One-day-old albino Wistar rats (Weight between 9 and 13 g) that were either bred in the animal facilities of INIBIBB and NIH or purchased through Charles River (Frederick, US) were used in all the experiments without distinction of sex. Breeders were between 3 and 8 months old, and kept as breeding pairs of one male and one female until birth. They were subject to 14 hr of light and 10 hr of darkness a day and were housed in One Cage 2100 Ventilated Cages (Lab Products Inc.). Food and water were provided ad libitum.

Euthanasia was performed by decapitation, without any prior anesthesia. All proceedings concerning animal use were done in accordance with the guidelines published in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All animals were housed and handled in accordance with the ARVO statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, USA guidelines, and following the protocols approved by the Institutional Committee for the Care of Laboratory Animals from the Universidad Nacional del Sur (Argentina).

2.3 |. Neuronal cell cultures

Culture dishes and wells were pretreated with poly-ornithine diluted in borate buffer (0.1 mg/ml) for at least an h, and then with 25% Schwannoma conditioned medium overnight. This medium contains a neurite promoting factor and was collected from confluent cultures of Schwannoma (RN22) cells after incubating them for 24 hr with DMEM (Adler, 1982). Pure neuronal retinal cultures were obtained according to previously established procedures (Politi et al., 1988; Rotstein et al., 1996). Briefly, retinas were extracted from 1-day-old pups, dissected, pooled together and dissociated under mechanical and trypsin digestion. Cells were then re-suspended in a chemically defined medium and seeded on 35 or 60 mm-diameter dishes (Greiner Bio-One 627160 and 628160, US, respectively), according to the experimental design. No a priori sample size calculation was performed, because of the exploratory nature of the experiments and since no live animals were involved, but retinal tissue was collected from rats for assays. Each experiment was performed in multiples within a litter, then replicated in different litters, with each dish acting as a separate sample unit. No sample size calculation was performed. Multiple animals were used for each experiment and their retinas were pooled after dissection.

The culture medium used in the present work was described previously (Politi et al., 1988) and consisted of DMEM supplemented with penicillin (100,000 U/l), glutamine (2 mM), cytidine 5’-diphosphocholine (2.56 mg/L), cytidine 5’-diphosphethanolamine (1.28 mg/L), hydrocortisone (100 nM), and the N1 supplement at twice the concentrations recommended by Bottenstein and Sato (i.e. insulin (16.6 × 10–7 M), progesterone (4 × 10–8 M), putrescin (2 × 10–4 M), selenium (6 × 10–8 M), and transferrin (12.5 × 10–8 M). (Bottenstein & Sato, 1979). Cultures were incubated at 36.5° in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

2.4 |. Immunocytochemical assays

At day 5 after seeding, the cultures were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, P6148) for 30 min at 25°C, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min, incubated with primary antibodies for 1 hr, followed by secondary antibodies conjugated to either Cy2, Cy3 (Jackson Immunoresearch), Alexa 488 or 555 (Invitrogen, US), diluted in PBS (all of the antibody combinations and concentrations can be found in Table 2 in the appendix). Anti-CRX antibody was a generous donation from Cheryl Craft (University of Southern California - Los Angeles, US) (Zhu & Craft, 2000). Nuclei were visualized with either Hoescht 33342 (Invitrogen, H3570) (20 μM); 4,6-d iamidinole-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Sigma, D9542) (35 μM) or TO-PRO-3 (Invitrogen, T3605) (2 μM), incubated for 1 hr. Between permeabilization and antibody incubations, samples were washed three times with PBS for at least 5 min each time. Unless specified, all incubations were done at 25°C. Any deviation from this protocol is indicated in their individual sections below.

2.5 |. Microscopy

Images were acquired using laser confocal scanning microscopy, using the DMIRE2/TSCSP2 microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 63X water objective, and processed using LCS software (Leica), the confocal microscopes Olympus FV1000, Zeiss 700 and Zeiss 880 and the fluorescence microscope Eclipse E600 (Nikon). The images were analyzed and processed using the ImageJ software program and ZEN, the proprietary software of Zeiss. We analyzed three dishes per condition with 10 fields chosen at random per dish for each experiment.

2.6 |. Addition of PEDF and derived peptides

PEDF and its derived peptides, 17-mer, 44-mer, and 34-mer were diluted in HBSS and aliquots were added to the cultures at 10 nM final concentration 48 hr after seeding the cells. The 17-mer and 44-mer peptides from the neurotrophic domain were the effectors and the 34-mer peptide from the antiangiogenic domain of PEDF was used as a negative control. For suppressing the effects of PEDF and its derived peptides, a fragment of the ligand-binding site of PEDF-R, the P1 blocking peptide, diluted in HBSS was added at a P1-PEDF molar ratio of 10:1. Alternatively, a selective inhibitor of PEDF-R, Atglistatin (Sigma, SML1075) at a 3.5 μM concentration (aliquoted and diluted in DMSO) was used. Both blocking peptide and inhibitor were preincubated in the cultures for 1 hr before adding the effectors. Preliminary experiments with 10 nM and 100 nM PEDF showed that 10 nM PEDF was the optimum PEDF concentration to promote survival of photoreceptors. The reported affinity of the PEDF/PEDF-R interactions is within this value (Kd of ~3 –10 nM PEDF) and the concentration of 10 nM PEDF has been used in assays with other cells such as R28 cells, which efficacy is blocked with 10-fold molar excess of P1 peptide or in the presence of 3.5 μM atglistatin (Kenealey et al., 2015; Notari et al., 2006; Subramanian et al., 2013).

2.7 |. Immunolabeling of PEDF-R (In vitro)

Cells were cultured in 4-chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 154526). The fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated in 0.5% BSA in PBS containing antibodies for PEDF-R (Sigma-Millipore, ABD66, US, diluted at 1:100) at 25°C for 1 hr.

For membrane marker detection, fixed and permeabilized cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml Wheat Germ Agglutinin (WGA) coupled to the fluorophore Alexa 555 in HBSS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, W32464, US) at 25°C for 10 min, following the manufacturer’s instructions. Then the images of cells were captured with the microscopes Zeiss 700 and 880. Z-stacks images were acquired with a 0.6 μm step size. The resulting stacks were then processed with the ZEN software.

2.8 |. Immunolabeling of PEDF-R (In vivo)

Eyes of rats at PN1 of age were enucleated, fixed in formalin solution, neutral buffered, 10% (Sigma, HT501128), for at least 72 hr, embedded in paraffin and then sectioned. A few eye sections were placed on slides and stained with H&E Mayer’s hematoxylin for histology. Other sections were deparaffinated by submerging them in xylene for 5 min, followed by sequential 5 min washes in decreasing concentrations of ethanol (100%, 95%, 70% and 50%) diluted with distilled water. Then, the sections on the slides were washed three times with PBS, and incubated with blocking solution (0.5% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, in PBS) for 30 min at 25°C. The slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-PEDF-R antibody (Protein Tech, 55190–1-AP, US) diluted 1:1,000 in PBS containing 0.5% BSA. After three washes with PBS, the sections were incubated with the secondary antibody (Invitrogen A11001, US) diluted 1:200 in PBS containing DAPI at 1:1,000 dilution for 1 hr at 25°C. The sections were washed another three times with PBS, mounted and imaged in the confocal microscope Olympus FV1000. Three different eyes from two different animals were processed and images were acquired. Additional sections were stained with H&E Mayer’s hematoxylin for histological analysis purposes.

2.9 |. Evaluation of neuronal cell death

Cell death was determined by incubating the cultures with 7.5 μg/ml of propidium iodide (PI) (Sigma, P4170, US), diluted in the media for 30 min at 37°C. Then, the cultures were washed twice with PBS, fixed, permeabilized, counterstained either with DAPI or TO-PRO-3, and analyzed by using phase-contrast, or laser scanning confocal microscopy, as described above. PI-labeled cells were considered non-viable.

Apoptosis was determined by TUNEL assay with the ApopTag® Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Sigma, S7110, US), following the manufacturer’s instructions, and nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (diluted 1:100), incubated for 15 min.

To evaluate cell death by Flow Cytometry, we used APO-BrdU™ TUNEL Assay Kit (Invitrogen, A23210, US), following the manufacturer’s instructions. These samples, along with positive and negative controls provided with the kit were analyzed in a Cytoflex NUV LX Flow Cytometer (Beckmann-Coulter). Additionally, we used the Annexin V-M itotracker kit (Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Apoptosis Kit, with Mitotracker™ Red & Annexin V Alexa Fluor™ 488, Thermofisher, V35116, US) for flow cytometry, following the manufacturer’s instructions. In both cases, DAPI was used to counterstain dead cells. Flow Cytometry data were analyzed with CytExpert (Beckmann-Coulter, US) and FlowJo (BD Biosciences) software. Thresholds between quadrants were set by using the positive and negative control samples provided in the kit.

2.10 |. Mitochondrial assays

Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed by MitoTracker Red CMXRos (Invitrogen, M7512) prepared and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, Mitotracker was added at a 200 nM concentration to the cell cultures and incubated for 30 min. The cultures were then washed with PBS, fixed, permeabilized, and their nuclei were counterstained with DAPI or TO-PRO-3 as described above, and cell labeling was then analyzed with a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse 600) or by confocal microscopy. For quantification, fluorescence intensity was thresholded by using an ND40 filter in the Nikon Eclipse or by increasing the offset in the confocal microscope. Cells with intense and discreet signal located on the axon hillock were selected as healthy.

2.11 |. Rhodopsin determination

Rhodopsin expression in PHRs was assessed by immunocytochemistry by using the Rho4d2 and Rho1d4 (MABN15 from Sigma-Millipore, and a generous gift of Dr. Robert Molday, respectively) (Laird & Molday, 1988). Both showed equivalent staining patterns.

2.12 |. Neurite outgrowth

To determine neurite outgrowth, pretreatment of dishes with the Schwannoma (RN22) conditioned medium was omitted, since, as described above, this medium contains a neurite promoting factor and is known to promote neurite outgrowth (Adler R, 1982). The cells were fixed, permeabilized as described above and incubated with anti-Acetylated Tubulin or Tuj1 for 1 hr. The length of the longest neurite and diameter of each cell were measured using ImageJ. The length was then divided by the diameter of its respective cell. Ratios were then plotted using GraphPad Prism (Version 8.2.0).

2.13 |. Western blotting

Cell cultures were lysed with RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 89900) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then the lysates were kept frozen at −80°C until use. Protein concentration in the lysates was quantified by the Bradford assay (Invitrogen, 23225). An equal amount of protein for each lysate was loaded into NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NP0301). The electrophoretic run was performed for 90 min at 125 volts with MOPS as the running buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, NP0001). The proteins in the gel were then transferred to a membrane using the iBlot 2 membrane transfer device (Invitrogen, IB21001). The transference was verified by Ponceau Red (Sigma P7170) staining for 2 min followed by washes with distilled water.

The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA diluted in TBST buffer (137 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, 0,1% Tween 20, pH 7.4) then incubated sequentially with anti-ATGL antibody (ABD66, Sigma-Millipore, 1:1,000 dilution in TBST with 1% BSA) overnight at 4°C. After three washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (Kindle Biosciences, R1005 and R1006, US; diluted at 1:10,000) for 1 hr, followed by incubation for 1 min with the Hi/Lo Digital-ECL Western Blot Detection Kit (Kindle Biosciences, R1004). Images of the immunoassayed blots were acquired with the Kwik Quant Imager (Kindle Biosciences, D1001, US). Then the membranes were stripped with Stripping Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 46430, US) for 10 min, then washed three times with PBS and incubated with anti-GAPDH (Genetex GTX627408, US) (diluted at 1:10,000) in the same manner as above. Images were acquired as described above.

2.14 |. RNA extraction and RT-PCR

The RNA extraction was performed from both, tissues and isolated cells in culture, with the RNAeasy minikit (Qiagen, 74106) according to the instructions of the manufacturer, including the optional step with RNAse-free DNAse (Qiagen, 79254). RNA extracted from whole retinas was stored at −80°C until processed in the same manner as the RNA samples belonging to cultures. For RT-PCR, the samples were run in the ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System with the QuantiTect SYBR Green (Qiagen, 204143). Amplification cycles were run 40 times with a first step at 95°C for 15 s, followed by a second step of 60 s at 60°C with a 1.6°C/s change at each step. The relative mRNA expression was calculated using the comparative threshold method (Ct-method) with 18S for normalization. For the housekeeping gene, 18S, we used the sample at a 1:1,000 dilution in RNAse-free water (Qiagen, 129112), Pnpla2 samples were undiluted. Each of the two biological samples were assayed for PCR in triplicate. RT-PCR primers were specifically designed to amplify the following cDNAs: Pnpla2 Forward: (5’-TGTGGCCTCATTCCTCCTAC-3’), Pnpla2 Reverse (5’-TGAGAATGGGGACACTGTGA-3’), 18s Forward (5’-GGTTGATCCTGCCAGTAGC-3’),18s Reverse (5’-GCGACCAAA GGAACCATAAC-3’). The efficiency was approximately 90% to each pair of primers. Accession numbers are: XM032891430 for Pnpla2, and AH001747 for 18S.

2.15 |. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by GraphPad Prism (Version 8.2.0), using either Student t-test or one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s multiple comparison test or Dunnet’s multiple comparison test, as suggested by the software. Data are shown as mean ±SEM of at least three independent experiments. Differences were considered significant at p < .05 (*); p < .01 (**), p < .001 (***), and p < .0001 (****).

3 |. RESULTS

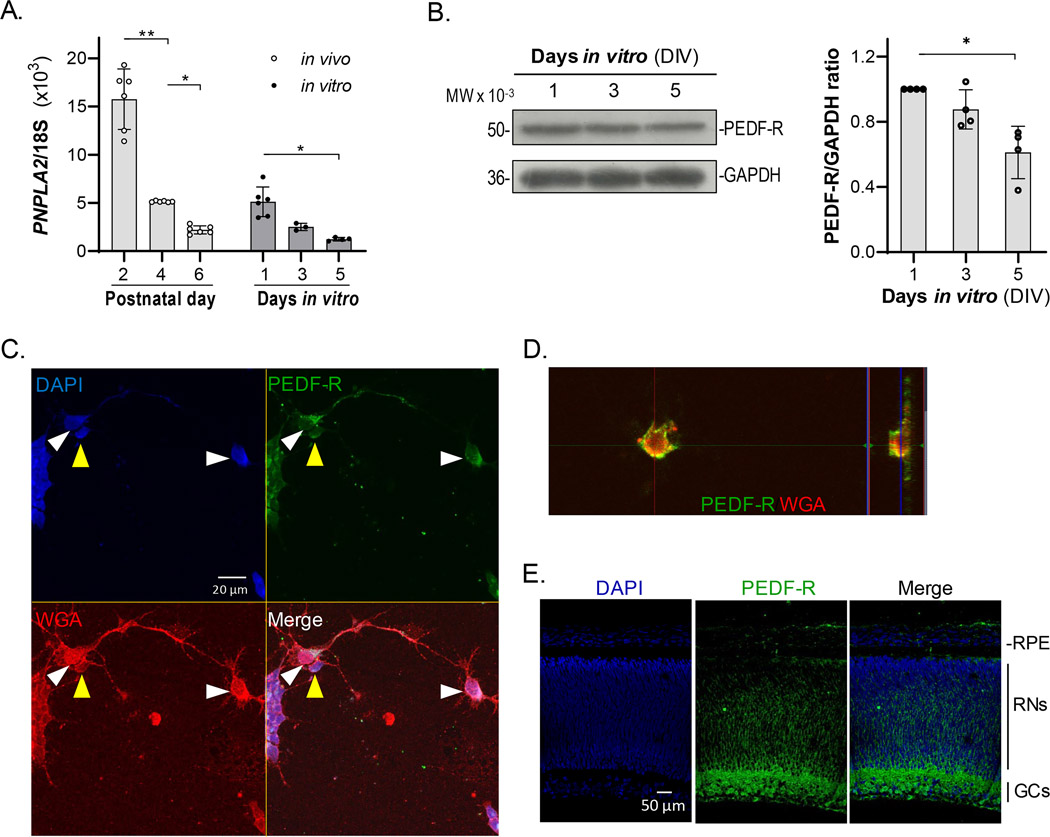

3.1 |. PEDF-R is present in primary retinal neurons in culture

We cultured primary neurons obtained from retinas of one day old (PN1) rats and examined the presence and relative abundance of the receptor for PEDF. As shown in Figure 1a, we assessed the expression of the Pnpla2 gene in primary retinal neuronal cultures at 1, 3, and 5 days in vitro (DIV), and compared the Pnpla2 expression levels with those in the whole retina, at 2, 4, and 6 post-natal (PN) days. Given that the cell cultures were from rats at PN1, the in vitro 1, 3, and 5 days (DIV1, DIV3 and DIV5) corresponded to their equivalents in vivo PN2, PN4, and PN6, respectively. RT-PCR revealed that the maximum Pnpla2 transcription values (Pnpla2/18S ratio) were obtained at PN2 in vivo and in its equivalent, first day in vitro (DIV1) (Figure 1a). Pnpla2 expression levels were lower for the in vitro than the in vivo cells. The Pnpla2 transcription values in the in vivo retina then rapidly and significantly decreased from about 15.7 at day PN2 to nearly one third and one seventh (5.7 and 2.2) at PN4 and PN6, respectively. The ratios obtained from in vitro experiments, also decreased from about 4 in the first day in vitro (DIV1) down to nearly one third (1.25) in the 5th day in vitro (DIV5). Then we assessed the production and distribution of PEDF receptor (PEDF-R) protein in pure neuronal cultures. Western blot assays of neuronal cell cultures at the same intervals showed that the protein followed a similar pattern to that of the mRNA (Figure 1b), decreasing with time in culture. Immunocytochemical evaluation of PEDF-R in retinal neurons in vitro revealed that it had a patched distribution in the cytoplasm around the nucleus and along the axons, colocalizing with the plasma membrane marker, wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), in both of the cell types that are known to be enriched in the cultures, amacrine and PHRs (Figure 1c). A similar colocalization was observed when comparing the staining patterns of PEDF-R and another plasma membrane marker, anti Na+-K+ pump (Figure S1). Orthogonal projection by confocal microscopy revealed that this protein was localized mainly in the plasma membrane (Figure 1d). We conclude that PEDF-R is present in both amacrine and photoreceptor cells, located primarily on the cell membrane.

FIGURE 1.

Expression of Pnpla2 and distribution of PEDF-R. (a) RNA expression of Pnpla2 in retina cells in culture in vitro and in vivo. Data were collected by RT-PCR with RNA obtained from retinal cultures at DIV1, 3 and 5 and their equivalent of in vivo retinas of 2, 4-, and 6-day old pups, and plotted to show the Pnpla2/18s ratios as a function of the days in vitro or age in vivo (± SD) (n = 3; n corresponds to the number of animals or number of independent cell culture preparations). Statistical analysis was performed with a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s Test. *p < .05, **p < .01. (b) PEDF-R protein in the cell cultures determined by western blot of protein extracts from cell cultures at DIV1 (lane 1), DIV3 (lane 2), and DIV5 (lane 3), stained with anti-PNPLA2 antibody (50 kDa band) and anti-GAPDH (36 kDa band). (n = 3; n = number of independent cell culture preparations). Statistical analysis was performed with a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s Test. *p < .05. (c) Photomicrograph of DIV5 retinal neuronal cultures immunostained with PEDF-R (green), the membrane marker Wheat Germ Agglutinin (red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). Pictures show amacrine cells (white arrowheads) and photoreceptor cells (yellow arrowheads) (Bar: 20 μm). (d) Orthogonal projection of a Z-Stack showing the colocalization area of PEDF-R (Red) with the membrane marker WGA (Green), taken from the previous culture in panel (c). (e) Photomicrograph of a section of a retina from a neonatal rat (PN1) immunostained with anti-PEDF-R antibody (Green) and counterstained with DAPI (Blue), showing PEDF-R presence in the retina layers. (Bar: 50 μm)

We also examined the distribution of PEDF-R in the native retina of a rat retina at PN1 by immunofluorescence with a specific antibody to PEDF-R. Histology of the retina (Figure S2) shows that most of the main components are present, albeit underdeveloped with a ganglionar layer and part of the inner nuclear layer that is not yet fully differentiated, and lacking the classical stratified pattern of the mature retina. Immunofluorescence showed that PEDF-R was detected in the retina of rat at PN1, primarily in the cell membrane as well, being more intense in the retinal ganglion layer, from which it radiates to the subjacent posterior layers (Figure 1e).

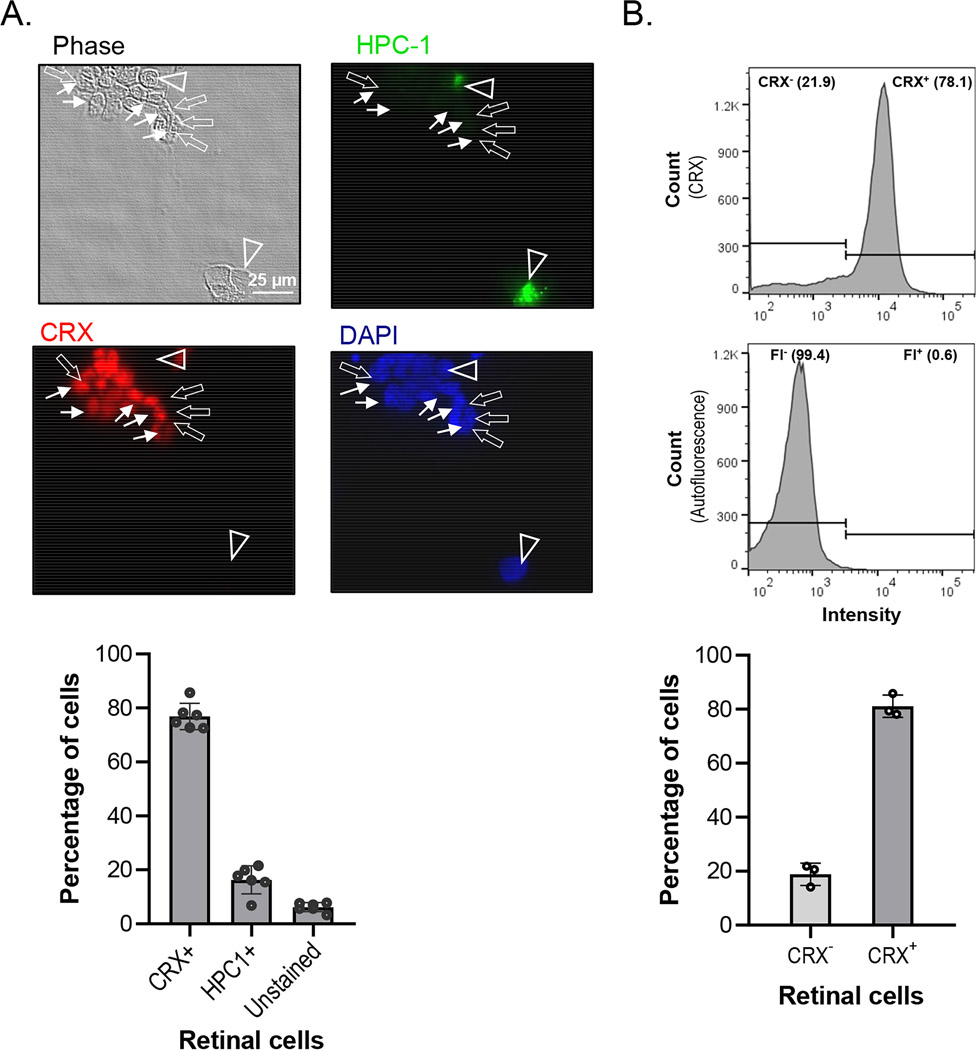

3.2 |. Photoreceptor and amacrine neurons were identified in the primary retinal cultures

Neuronal cell types were identified by their morphology using phase contrast microscopy and by immunocytochemistry. Under the microscope, we identified individual cell types as follows: 1) PHRs have a small (5–10 μm) round and dark cell body bearing a single neurite at one end with or without an outer segment-like process; 2) Amacrine neurons have either single or multiple neurites, a bigger cell body (around 10–30 μm) and a broad morphological heterogeneity. PHRs were identified by immunocytochemistry with anti-CRX antibody (Figure 2a). CRX is a transcription factor expressed at early stages of development of PHRs. Amacrine neurons were identified by immunocytochemistry with the monoclonal Anti-HPC1 antibody (Figure 2a). HPC-1 reacts with a 35 kDa polypeptide, identical to syntaxin and labels the plasma membrane of the amacrine cell soma and the inner plexiform layer in rat retina and other central neurons (Akagawa & Barnstable, 1986; Barnstable et al., 1985). Figure 2a shows that immunostaining of the PHR marker CRX, encompass the vast of majority of the cells in culture, representing nearly 80% of the total amount of cells in culture and the amacrine neurons marked HPC-1 labels about 15% of the cells (Figure 2a). The remaining unstained cells were confirmed as dead by phase and DAPI. Flow cytometry assay of samples labeled with anti-CRX antibody revealed a relative abundance of events (80%) in line with the values observed by immunocytochemistry (Figure 2b). These observations indicate that the retinal primary cultures are composed mainly of photoreceptors with a lower percentage of amacrine neurons.

FIGURE 2.

Identification and quantification of retinal neurons in culture. (a) Cells from rat retinas at PN1 were cultured from six batches of cells in two different laboratories (from P. Becerra’s and L. Politi’s laboratories). Cultures were prepared in duplicate wells and immunofluorescence for labeling CRX and HPC-1 was performed. Representative images of immunofluorescence of retinal cells in culture at DIV5 labeled with anti-Crx (CRX+, arrows) and anti-HPC-1 (HPC1+, arrowheads) with cell nuclei stained with DAPI are shown. (Bar: 25 μm). Images from 8 different fields per well were acquired for quantification of CRX+ and HPC1+ labeled cells and the percentages were calculated relative to the number of DAPI labeled nuclei in each field and shown in the plot. (n = 6) (b) Flow cytometry of rat retinal cells at DIV5 that were CRX-immunostained (Top histogram), and compared with cells without fluorophore as control (Bottom histogram). Histograms were gated to show the relative abundance of CRX-positive and negative populations, compared to their fluorescence control. A plot with quantification of the percentages of CRX+ events in cultures from independent litters is shown (n = 3)

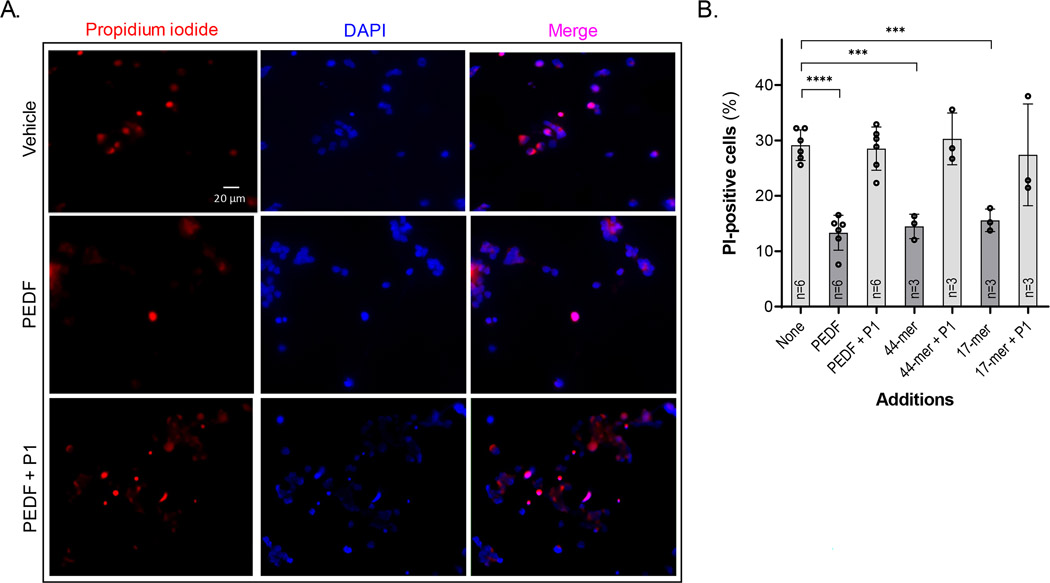

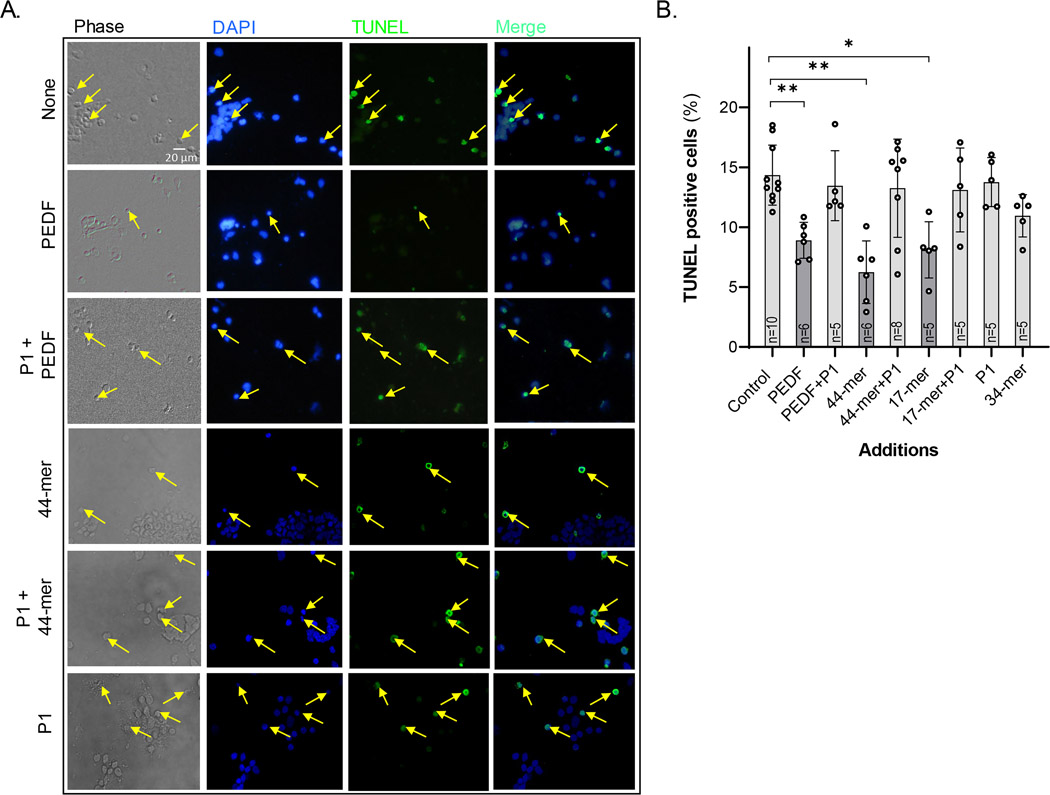

3.3 |. PEDF, and the 44-mer and 17-mer fragments protected retinal neurons from cell death

Previous work has shown that in the absence of trophic factors, PHRs degenerate during time in culture (Rotstein et al., 1996, 1998). To evaluate the potential pro-survival effects of PEDF and its derived peptides, neuronal cultures were incubated with either PEDF, the 17-mer and 44-mer (neurotrophic) peptides, or the 34-mer (antiangiogenic) peptide at DIV 2. Then cell death was determined at DIV5 by measuring cells that had nuclei labeled with propidium iodide (PI) (Figure 3a) and terminal deoxyribonucleotidyl transferase (TDT)-mediated dUTP-d igoxigenin nick end labeling (TUNEL) (Figure 4). PI, a small fluorescent molecule that binds DNA but cannot passively traverse into cells with an intact plasma membrane, was used to discriminate dead cells, in which plasma membranes become permeable regardless of the mechanism of death, from viable cells with intact membranes. While control cultures (treated with vehicle alone) had about 29% of PI-positive cells, those treated with 10 nM PEDF, 44-mer peptide or 17-mer peptide had lower percentage of non-viable cells (13%, 15%, and 16%, respectively) (Figure 3b). In contrast, when the cultures were treated with effectors preincubated with 100 nM of blocking P1 peptide, the percentage reverted (29%, 30%, and 27%, respectively) (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides in the prevention of cell death. (a) Fluorescence photomicrographs of 5-day (DIV5) cultures supplemented with vehicle (control)-, PEDF-, and PEDF +P1, showing PI (red) stained neurons (arrows), and counterstained with DAPI (blue) (Bar: 20 μm). (b) Percentages of PI-positive nuclei in cultures treated without (None) or with PEDF; and PEDF-derived peptides, preincubated or not with the blocking peptide, P1, as indicated in the x-axis. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s test. ***p < .001, ****p < .0001 (n, number of independent cell culture preparations per condition is indicated in each bar)

FIGURE 4.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides in apoptosis prevention. (a) Photomicrographs of DIV5 cultures showing TUNEL (green label) positive neurons (arrows), and counterstained with DAPI (blue) (Bar: 20 μm); (b) Percentages of TUNEL-positive nuclei relative to control samples. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s test. *p < .05, **p < .01, (n, number of independent cell culture preparations per condition is indicated in each bar)

TUNEL of free 3’-hydroxyl termini of double-stranded DNA fragments in situ was performed to detect DNA damage in cells. Control cultures had approximately 8%–12% of TUNEL-positive cells, and most of them displayed fragmented or pyknotic nuclei (Figure 4a). Additions of PEDF, 44-mer or 17-mer peptides (10 nM) decreased the number of TUNEL-positive cells, being 62 ± 6.2%, 45 ± 6.5%, 59 ± 0.9%, respectively, of that of the control value (Figure 4b). In all cases, preincubation of the effectors with a 10-fold molar excess of the blocking P1 peptide abolished these effects. The antiangiogenic 34-mer peptide and the P1 peptide alone had no protective effect on these cultures (Figure 4b).

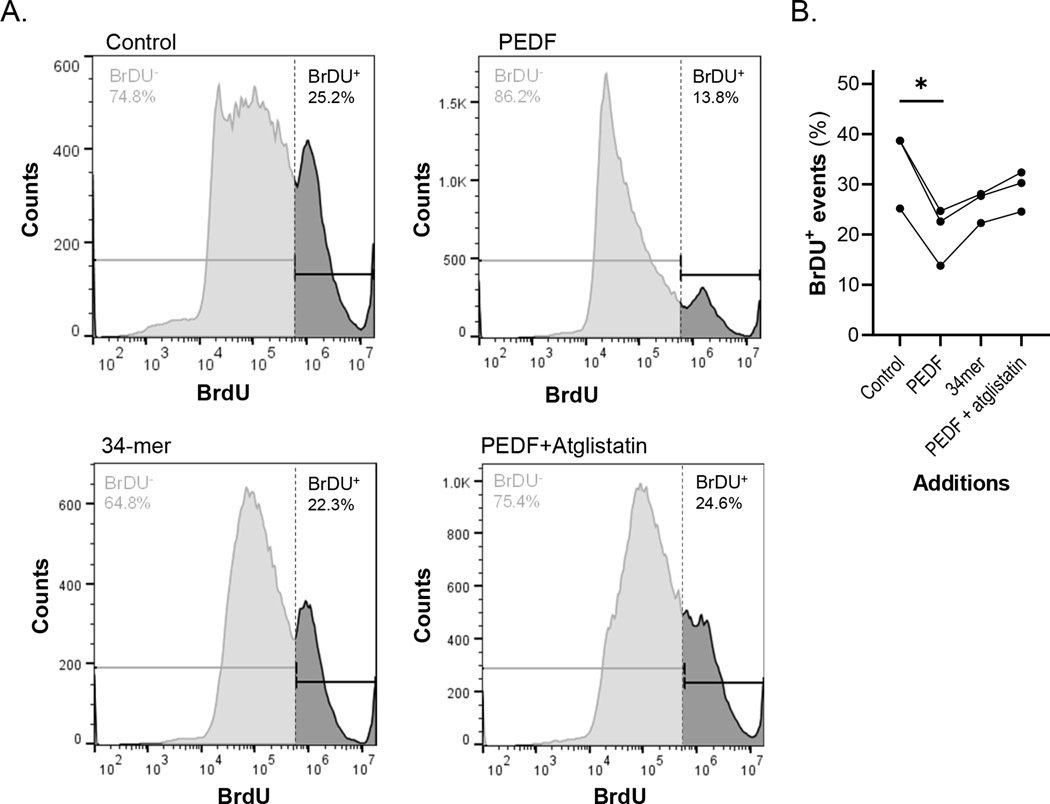

Flow Cytometry analysis to evaluate prevention of DNA fragmentation-related apoptosis in cultures treated with PEDF and the peptides was also performed. Figure 5 shows that PEDF decreased the percentage of TUNEL-BrDU positive cells. This effect was reversed when the cultures were pre-incubated with atglistatin, an inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of PEDF-R prior to PEDF addition. In contrast, control conditions and 34-mer treated-cultures had similar percentages of TUNEL-positive cells (as indicated by their BrdU intensity).

FIGURE 5.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides in DNA fragmentation prevention. (a) Flow Cytometry analysis of DIV5 cultures treated without (control), or with PEDF; PEDF +Atglistatin; or 34-mer peptide by TUNEL with BrDU. Histograms of Counts (number of events, Y axis) as a function of BrDU intensity (X axis). Each histogram has a vertical line delimiting low versus high BrDU intensity events, set at 1.4 × 105 arbitrary intensity units. (b) Flow cytometry of three cultures from independent batches of cells was performed. Percentages of TUNEL-BrDU positive cells in each condition, compared within their own batch were plotted. Each data point corresponds to the percentage of events in threshold area for high BrDU labeling (BrDU+) from an individual culture Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s test. *p < .05 n = 3 flow cytometry assays with three independent cell cultures

Altogether, these results show that PEDF and its neurotrophic fragments, 44-mer and 17-mer, specifically prevented neuronal retinal cell death and DNA damage, and implicated the PEDF/PEDF-R axis in promoting retinal cell survival.

3.4 |. PEDF inhibitory effects on early events of cell death in the low FSC cell population

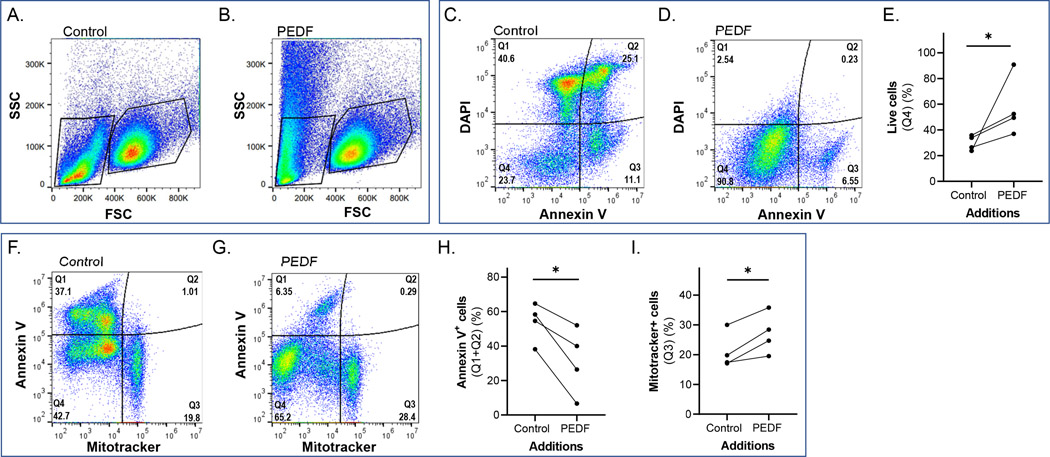

Flow Cytometry analysis of the cultures revealed the presence of two cell populations, distinct in size as measured by the FSC parameter (Figure 6a, b). The low FSC cell population likely corresponded to PHRs, which differs in cell size from amacrine neurons and are the main neuronal cell types previously described in the primary retinal cell cultures used here (Politi et al., 1988).

FIGURE 6.

Flow Cytometry assays of control and PEDF-treated cultures at DIV5. (a, b) Forward-Side Scattering plots of DIV5 Vehicle-(Control), and PEDF-treated cultures, respectively, showing the low- and high- forward scatter (FSC) neuronal populations. The low-FSC population was selected for flow cytometry analyses and shown in the rest of the panels. (c, d) The low-FSC population for control and PEDF treated cultures was labeled with DAPI (Y axis) and annexin V (X axis), and representative plots are shown for control and PEDF in panels (c) and (d), respectively. (e) Flow cytometry of four individual batches of cell cultures per condition were performed and percentages of annexin V-negative and DAPI-negative cells (Q4, corresponding to live cells) in vehicle (control) and PEDF-treated cells were plotted comparing each control with its PEDF-treated counterpart. Each data point corresponds to the percentage of events in Q4 from an individual culture (n = 4). (f, g) The low-FSC population for control and PEDF-treated cultures was labeled with annexin V (Y axis) and Mitotracker (X axis) and plots are shown for control and PEDF, in panels (f) and (g), respectively. (h, i) Flow cytometry of four individual batches of cell cultures per condition were performed (n = 4). (h) Percentage of high annexin-V events (Q1 + Q2, Y-axis) were plotted comparing each control-with its PEDF-treated counterpart from each culture. Each data point corresponds to the percentage of events in Q1+Q2 from an individual culture. (i) Percentage of high Mitotracker events (Q3) in the low-FSC population compared to their respective control sample. Each data point corresponds to the percentage of events in Q1+Q2 from an individual culture. Statistical analysis was performed using a ratio-paired t-test. *p < .05

Annexin V, a phospholipid-binding protein, was used to detect the redistribution of phosphatidyl serine (PS) that occurs from the inner to the outer leaflet of plasma membrane lipid bilayers during early events of cell death. DAPI, a fluorescent stain that binds strongly to A-T-rich regions in DNA, was also used as it inefficiently traverses intact cell membranes and therefore, preferentially stains dead cells. Analysis of the low FSC population, the PHRs, under control conditions indicated that a minority of the cells were negative for annexin V and DAPI staining (Figure 6c, Q4) while the remaining (Figure 6c, Q1-Q3) were positive for either or both, implying that this population underwent cell death. In contrast, when the cultures were treated with PEDF a significant percentage of cells were negative for annexin V and DAPI staining (Figure 6d Q4), indicating PEDF-mediated protection against cell death (Figure 6e); mainly shown by the decrease in annexin V-positive events when treated with PEDF (Figure 6h). These results imply that PEDF prevented phosphatidyl serine flipping and loss of structural integrity of the plasma membrane consistent with inhibition of early events of PHR cell death.

3.5 |. PEDF and the 44-mer fragment selectively increased mitochondrial membrane potential in PHRs

To evaluate mitochondrial involvement in PEDF-induced cell survival, we determined MitoTracker-positive cells among the cells in the low FSC population of presumptive PHRs by flow cytometry. MitoTracker Red CMXRos, a cell permeable probe that contains a mildly thiol-reactive chloromethyl moiety, was used to stain mitochondria in live cells because it passively diffuses across the plasma membrane to accumulate in active mitochondria in a membrane potential-dependent fashion. The results showed that, on the one hand, a minority of the cells in controls exhibited intense MitoTracker staining along with no annexin V staining (Figure 6f, Q3). This observation indicated that a few cells preserved healthy mitochondria and no presence of PS in the outer membrane. On the other hand, the majority of cells showed a weaker MitoTracker staining (Figure 6f, Q1 and Q4) with half of them having high annexin V staining (Figure 6f, Q1), indicating that part of this population had its mitochondrial function and cell membrane compromised. In contrast, when the cultures were treated with PEDF a significantly higher percentage of the low-SFC population (presumptive PHRs) were heavily stained with MitoTracker (compare Q3 of Figure 6f and Figure 6g; Figure 6i) and almost none of these cells were annexin V-positive (Figure 6g, Q1, Q2), thus indicating that PEDF preserved their mitochondrial function.

3.6 |. Effects of PEDF on the population of the high FSC cell population

The population of larger sized cells, presumptively amacrine neurons, were negatively stained for DAPI and annexin V under both control conditions and PEDF-treated conditions (Figs. S3a, S3b, Q4), indicating that they had intact cell membranes. Nearly all these neurons exhibited intense MitoTracker staining, indicating that they had healthy mitochondria even in the absence or presence of PEDF (Figures S3c and S3d, Q3). In this regard, it is important to mention that the chemically defined medium used for these cultures contains insulin, which we have previously demonstrated is a trophic factor for these neurons (Politi et al., 2001c).

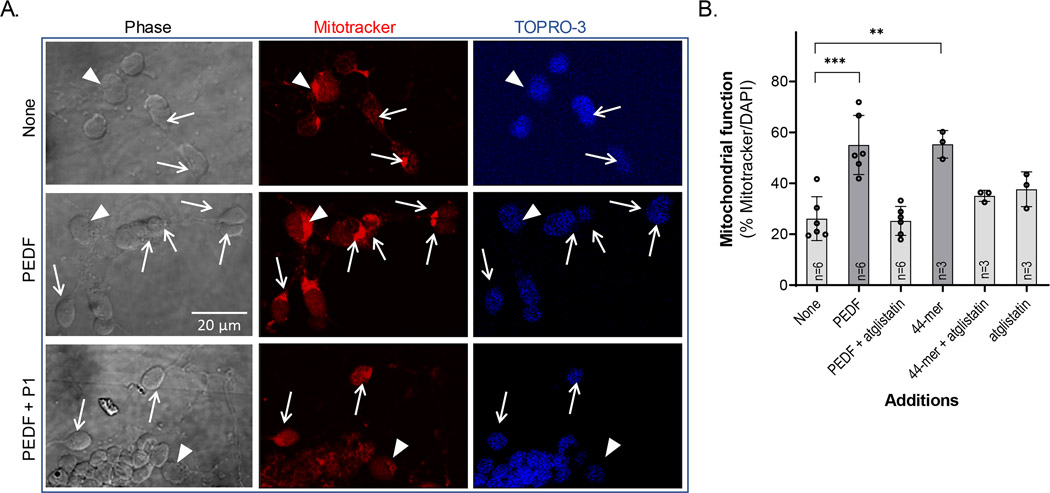

3.7 |. Cytochemical examination of mitochondria of neuronal retinal cells treated with PEDF

Neuronal cultures stained with MitoTracker showed brilliant punctate red dots in the cytoplasmic areas around the nucleus and in the axon hillock (Figure 7a), illustrating preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential in both, amacrine neurons and PHRs (arrows in Figure 7a). Amacrine neurons and PHRs were identified as indicated in Materials and Methods. In control cultures, 26% of PHRs (white arrows) retained active mitochondria by day DIV5, and this value was more than double (55%) when cultures were incubated with PEDF or with 44-mer (Figure 7b). The increases in MitoTracker-positive cells were blocked by the inhibitor atglistatin peptide (Figure 7a). The amacrine neurons retained active mitochondria, regardless of the absence or presence of PEDF or its derived factors (cells labeled with white arrowheads in Figure 7a).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides in the preservation of mitochondrial activity. (a) Phase and fluorescence photomicrographs of DIV5 vehicle- (control), PEDF-, and PEDF+P1-treated cultures showing MitotTracker (red) and TO-PRO-3 (blue) stained cells. Arrowheads point toward amacrine neuronal cells (Ams) and arrows mark PHR cells with active mitochondria. Note that Ams showed brilliant (active) mitochondria regardless of PEDF supplementation, while PHRs depend on PEDF to retain their active mitochondria. Both neuronal cell types were identified as indicated in Materials and Methods. (Bar: 20 μM). (b) Percentage of PHRs bearing active mitochondria in cultures treated with HBSS (control); PEDF and PEDF with and without atglistatin. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s test. **p < .01, ***p < .001 (n, number of independent cell culture preparations per condition is indicated in each bar)

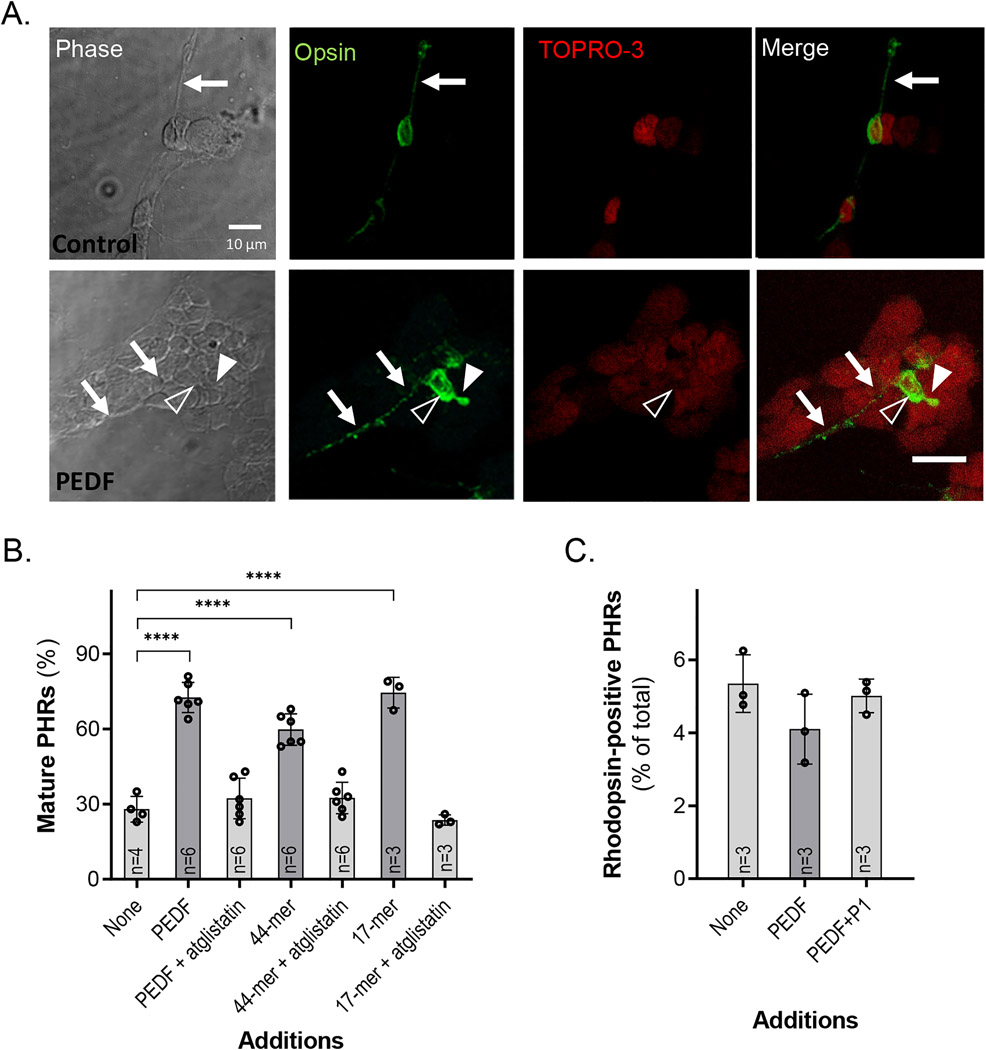

3.8 |. PEDF promoted opsin apical localization on PHRs

At DIV5 and in the absence of neurotrophic factor, most rhodopsin-positive PHRs showed a diffuse opsin distribution along the cell membranes, both in the cell body and axons, reflecting an immature stage of differentiation (Figure 8a and S2a). During PHR development and differentiation, rhodopsin tends to gradually fade away from the axons (Figure S4b), until it is solely located in the cell body. Later, rhodopsin starts to polarize toward the apical region (Figure S4c), where it finally constitutes a rhodopsin-positive structure (Figure S4d). However, under control conditions at DIV5, only 28% of PHRs reached this rather mature state of differentiation (Figure 8b). Remarkably, addition of PEDF dramatically increased the percentage of PHRs having rhodopsin positive apical processes to about 72.5% (Figure 8b). The effects of the 17-mer and 44-mer fragments mimicked those of PEDF; which were blocked by atglistatin (Figure 8b). These results imply that PEDF and the 44-mer and 17-mer fragments promoted PHR differentiation and proper rhodopsin localization. However, the number of PHRs containing rhodopsin remained the same in control cultures as in those with PEDF and peptides (Figure 8c).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides on rhodopsin distribution in PHRs during development. (a) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence photomicrographs of DIV5 cultures showing opsin (green) distribution, counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (red) in control (no PEDF) and PEDF-treated PHRs. Note that in control cultures, rhodopsin is homogenously distributed in both the cell body and neurites (arrows), while in PEDF-treated conditions, rhodopsin is concentrated in the cell body and in the outer segment-like structure (arrowheads) (Bar: 10 μm); (b) Percentages of rhodopsin-positive PHRs only labeled in the cell body. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett’s test. ****p < .0001 (n, number of independent cell culture preparations per condition is indicated in each bar). (c) Percentages of rhodopsin positive PHRs in control; PEDF and PEDF +P1 treated cultures (n, number of independent cell culture preparations per condition is indicated in each bar)

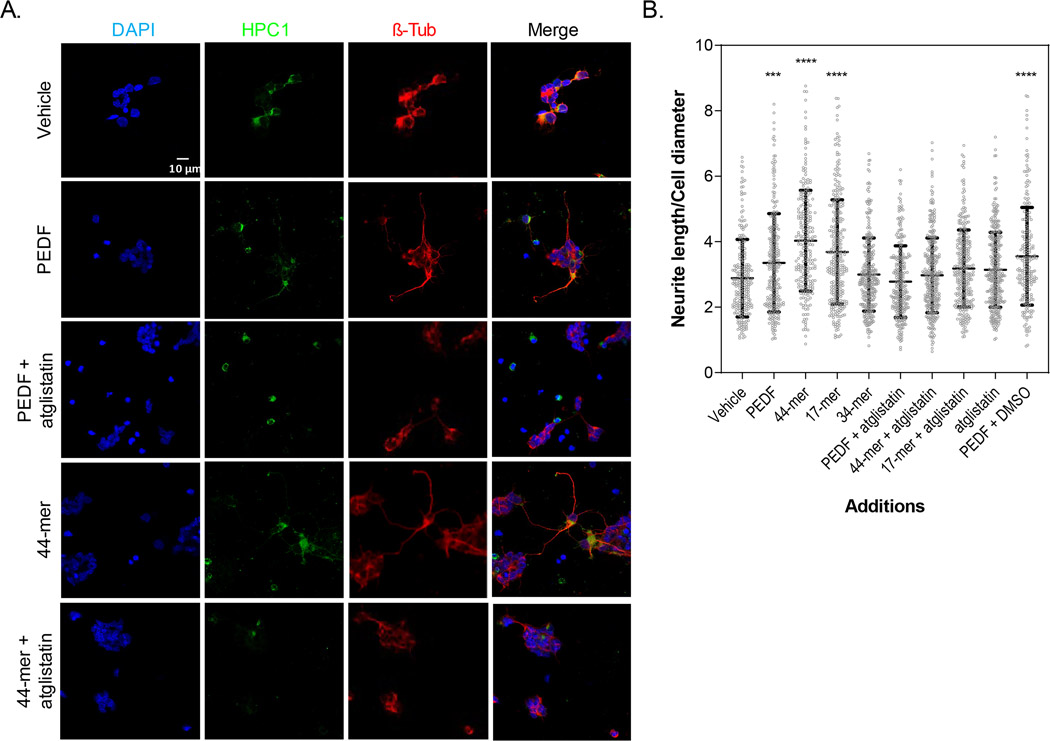

3.9 |. The 44-mer and 17-mer fragments promoted neurite outgrowth

Like PEDF, the 44-mer and 17-mer peptides also exhibited an effect on neurite outgrowth, which was driven particularly by amacrine neurons, as shown by immunocytochemistry using antibodies against βIII Tubulin and HPC-1, biomarkers for neurons and early amacrine cell development, respectively (Figure 9a). PEDF, and the 44-mer and 17-mer fragments increased the average ratio of neurite length to their cell diameters to 3.3, 4.0, and 3.6 length/diameter ratio, respectively, from 2.8 in length/diameter ratio for control cultures treated with vehicle (Figure 9b). The inhibitor of PEDF-R atglistatin decreased the average of neurite length/diameter ratios of neurons treated with PEDF, 44-mer and 17-mer to 2.8, 2.9, and 3.1 in length/diameter ratio, respectively. Addition of DMSO, the vehicle used for atglistatin, did not alter the PEDF efficacy, and the 34-mer did not induce neurite outgrowth. Moreover, cultures incubated with 10-fold molar excess of the blocking P1 peptide over PEDF showed no effect of PEDF on neurite outgrowth, evidencing that the longest neurites corresponded to those of PEDF-treated cultures (Figure S5). These observations demonstrated that the 44-mer and 17-mer fragments, like PEDF, specifically promoted neurite outgrowth in amacrine neurons in culture.

FIGURE 9.

Effects of PEDF and its derived peptides on neurite outgrowth. (a) Fluorescence photomicrographs of DIV5 cultures showing HPC-1 positive (green) amacrine neurons, labeled with ß-Tubulin (red) and counterstained with DAPI (blue), for neurite outgrowth in control; PEDF, 44-mer; and PEDF plus atglistatin-treated cultures. (Bar: 10 μm). (b) Dot-plot showing neurite length measurements under different treatments, as indicated in the x-axis. Statistical analysis was performed using a one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Tukey’s test. ***p < .001, ****p < .0001, respect to control (None). (n = 3; n = number of independent cell culture preparations)

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the neurotrophic effects of PEDF fragments in a model of cultured primary retinal neurons that undergo programmed cell death in the absence of trophic factors in vitro. The results show that full-length human PEDF protein and the small 44-mer and 17-mer peptides (78–121 and 98–114 residue positions of human PEDF, respectively) prevent cell death and promote differentiation of rat retinal PHRs and amacrine neurons in vitro. Moreover, the PEDF-mediated effects on PHR cell survival and differentiation are associated to prevention of plasma membrane disruption, phosphatidyl serine flipping, DNA damage and preservation of mitochondrial membrane potential, and implying that PEDF inhibits early cell death processes. In addition to promoting apical localization of opsin in PHRs the 17-mer and 44-mer peptides selectively stimulate axonal outgrowth in retinal amacrine neurons. Noteworthy, the antiangiogenic peptide 34-mer (44–77 positions) lack these activities. Interestingly, the distribution of PEDF receptors (PEDF-R) in plasma membranes explain the diverse activities mediated by PEDF/PEDF-R interactions in both PHRs and amacrine neurons, which agrees with a cell-context dependency of the pleiotropic functions of PEDF mediated by PEDF-R activation.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report demonstrating the neurotrophic activities of PEDF in a primary cell culture system for the retina. Previous studies have demonstrated PEDF neurotrophic activities on retinal ganglion cells in culture using mixed cell cultures enriched in this cell type from adult rat retina or retinas from 7-day-old mice. PEDF protects retinal ganglion cells from glutamate- and trophic factor withdrawal-mediated cytotoxicity (Pang et al., 2007) and hypoxic insult (Unterlauft et al., 2012) and promotes axon growth in these cells (Vigneswara et al., 2013). Regarding the cultures in the present study, most PHRs undergo programmed cell death at the time of synaptogenesis and during development of retinal neurons in culture, which is equivalent to the biological process of their counterparts in the native retina in vivo. PHRs rely on the supply of trophic factors from specific regions of the retina for their survival and development, and to guarantee the correct placement of the PHR layer (Adler 1986; Watanabe et al., 1992). PEDF is one of these factors, and plays a critical role as a survival-promoting factor for PHRs in vivo (Cayouette et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2019; Comitato et al., 2018; Hernández-Pinto et al., 2019; Kenealey et al., 2015; Miyazaki et al., 2008; Murakami et al., 2008) and in vitro, as demonstrated here.

PEDF receptors are widely distributed on the cell surface of both PHRs and amacrine neurons at their early stages of development (Figure 1). Several factors can account for the discrepancy between the observed decline in PEDF-R mRNA expression (Figure 1a) and the subtle reduction in its protein expression (Figure 1b) from DIV1 to DIV5, such as post-transcriptional control, translational control, a different rate of RNA and protein degradation, among others. PEDF-R is present in the native newborn rat retina (Figure 1e). In the adult albino rat, it is detected in PHR inner segments (Notari et al., 2006). This observation suggests a likely extensive and cell selective role for PEDF during retina development.

While PEDF preserves mitochondrial activity and cell survival in PHRs, it promotes axonal development in amacrine neurons, an outgrowth effect that is not observed in PHRs. However, given that amacrine neurons do not die in these cultures, it cannot be ascertained whether PEDF acts in neuroprotecting them. Noteworthy, the neurotrophic fragments of PEDF, 17-mer and 44-mer, have the same effects as PEDF. Therefore, PEDF appears to play a critical role in preventing PHR cell death and orchestrating the development and differentiation of the retina and this role can be almost exclusively ascribed to its neurotrophic fragments.

The present study provides insight into a molecular mechanism of action for PEDF on PHR development and amacrine neurite outgrowth. The specific interaction of the neurotrophic domain of PEDF with PEDF-R occurs in the primary neuronal retinal cultures. This conclusion is based on the observed neurotrophic effects of the 44-mer and 17-mer peptides in combination with the attenuation of these effects by blocking the PEDF/PEDF-R interactions (use of blocking P1 peptide) and inhibiting the PEDF-R enzymatic activity (use of atglistatin). The fact that the neurotrophic 44-mer and 17-mer peptides have PEDF-R binding affinity (Kenealey et al., 2015) and the unrelated 34-mer peptide does not, points to the specific requirement of the 17-mer region of PEDF for binding and activity (Kenealey et al., 2015; Figures 2–7). Thus, PEDF action requires the binding to and stimulation of PEDF-R in PHRs and amacrine cells, resembling the PEDF dependency on PEDF-R activation for survival of the rat retinal R28 cell line (Subramanian et al., 2013).

Interestingly, the effects of PEDF on PHR survival and differentiation are similar to those exerted by DHA (Garelli et al., 2006). These similarities are not surprising, given that the PEDF-R has a phospholipase A activity, which PEDF binding enhances its hydrolysis of phospholipids to release fatty acids, among them DHA (Subramanian et al., 2010; Pham et al., 2017). DHA preserves mitochondrial functionality, prevents apoptosis and promotes differentiation of PHRs (Rotstein et al., 1996, 1997, 2003; Politi et al., 2001b; German et al., 2006; German et al., 2013) resembling the effects of PEDF. Furthermore, 4-bromoenol lactone, an inhibitor of calcium-independent phospholipase A2, blocks the DHA-mediated prevention of oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of PHRs (German et al., 2013). Interestingly, 4-bromoenol lactone also inhibits PEDF-R and blocks the PEDF-mediated cytoprotective activity and induction of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2) gene expression in R28 cells (Notari et al., 2006; Subramanian et al., 2013). Thus, it appears that PEDF and DHA are the two faces of the same coin, given that either by adding DHA or by activating PEDF-R, they promote similar survival and differentiation effects on PHRs. These similarities suggest that PEDF activation of PEDF-R leads to DHA release from phospholipids, becoming the biological mediator of the PEDF/PEDF-R interactions, decreasing death and promoting differentiation in PHRs. This hypothesis requires further study. Lipidomics and proteomics profiles of the primary rat retinal cultures treated with PEDF peptides will be instrumental to address the identification of bioactive lipids and proteins of the PEDF actions in PHRs. Different trophic factors can activate MEK/ERK and/or PI3K pathways involved in PHR survival (German et al., 2006), and these pathways are likely candidates for PEDF survival effects in these retinal cultures. We plan to investigate the signaling pathways triggered by PEDF in our cultures in a future study.

In summary, the findings demonstrate that the use of primary neuronal retinal cell cultures are useful to gain understanding of the individual effects of the multimodal PEDF on the diverse cell population of the retina, as shown here for PHRs and amacrine cells. In addition, the findings establish the neurotrophic PEDF peptides as neuronal guardians for the retina, highlighting their potential as promoters of retinal differentiation, and inhibitors of retina cell death and its blinding consequences.

Supplementary Material

Table 2: Immunocytochemistry data.

Antibody combinations used in this paper, along with concentration and incubation time.

| Primary antibody* |

Secondary antibody** |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Company | Cat. Number | Dilution | Name | Company | Cat. Number |

| HPC-1 | Abcam | ab3265 | 1/40 | Goat anti-mouse (Cy2) | Invitrogen | 115-225-146 |

| CRX | Gift of C. Craft. | N/A | 1/400 | Goat anti-rabbit (Alexa 488) | Invitrogen | A11001 |

| PEDF-R (1) | Sigma-Millipore | ABD66 | 1/100 | Goat anti-rabbit (Alexa 555) | Invitrogen | A27039 |

| PEDF-R (2) | Cayman | 10006409 | 1/100 | Goat anti-rabbit (Alexa 555) | Invitrogen | A27039 |

| PEDF-R (3) | R&D | AF5365 | 1/100 | Goat anti-mouse (Alexa 488) | Invitrogen | A28175 |

| Rhodopsin | Sigma-Millipore | MAB5356 | 1/100 | Goat anti-mouse (Alexa 488) | Invitrogen | A28175 |

| Rhodopsin | Gift of R. Molday | N/A | 1/100 | Goat anti-mouse (Cy2) | Jackson Immunoresearch | 115–225-146 |

| Tuj1 | Abcam | ab24610 | 1/300 | Goat anti-mouse (Cy2) | Jackson Immunoresearch | 115-225-146 |

| Acetylated Tubulin | Abcam | ab18207 | 1/300 | Goat anti-rabbit (Cy3) | Jackson Immunoresearch | 115-16-003 |

| Na/K pump | Sigma-Millipore | 06–520 | 1/100 | Goat anti-rabbit/mouse (Alexa 555/488) | Invitrogen | A27039/A28175 |

Primary antibodies were diluted in PBS and the incubation time and temperature were 1 h at 25°C or 16 h at 4°C. The specificity of the antibodies used has been validated previously (see Table S1).

Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:200 in PBS and the incubation time was 1 h at room temperature

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Eye Institute, NIH, U.S.A. [Project #EY000306], and by the National Research Council of Argentina (CONICET): PIP 1122015, to LP and National Agency for Science and Technology (ANPCYT): PICT 2016-0353, to LP), American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology USA (PROLAB award to GM). The authors thank Drs. Robert Molday (University of British Columbia, Canada) and Dr. Cheryl Craft (University of Southern California - Los Angeles, US) for generously providing antibodies to rhodopsin and to CRX, respectively. The authors also thank the laboratory members for continuous encouragement and ideas and the staff of the Politi’s and Becerra’s labs and NEI animal facility, Confocal Microscopy Services and Biological Imaging Core and Flow Cytometry Core facilities for technical support, Marcela Vera, for sharing their expertise with western blotting.

All experiments were conducted in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Funding information

Intramural Research Program of the National Eye Institute, NIH, U.S.A., Grant/Award Number: Project #EY000306; National Agency for Science and Technology (ANPCYT), Grant/Award Number: PICT 2016-0353; National Research Council of Argentina (CONICET), Grant/Award Number: PIP 1122015; American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology USA, Grant/Award Number: PROLAB

Abbreviations:

- Am

amacrine

- DAPI

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- DIV

days in vitro

- FSC

forward-scatter

- PEDF

pigmented epithelium-derived factor

- PEDF-R

PEDF receptor

- PHR

photoreceptor

- PI

propidium iodide

- PN

postnatal

- Pnpla2

patatin-like phospholipase-2

- PS

phosphatidyl serine

- SSC

side-scatter

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

A preprint was posted on bioRxiv on Jan 01, 2021 doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.01.425044

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Adler R.(1982). Regulation of neurite growth in purified retina cultures: Effects of PNPF, a substratum-bound neurite-promoting factor. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 8(2–3), 165–177. . 10.1002/jnr.490080207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R.(1986). Developmental predetermination of the structural and molecular polarization of photoreceptor cells. Developmental Biology, 117(2), 520–527. 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90319-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akagawa K, & Barnstable CJ (1986). Identification and characterization of cell types in monolayer cultures of rat retina using monoclonal antibodies. Brain Research, 383, 110–120. 10.1016/0006-8993(86)90012-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral J, & Becerra SP (2010). Effects of human recombinant PEDF protein and PEDF-derived peptide 34-mer on choroidal neovascularization. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 51, 1318–1326. 10.1167/iovs.09-4455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnstable CJ, Hofstein R, & Akagawa K.(1985). A marker of early amacrine cell development in rat retina. Developmental Brain Research, 20, 286–290. 10.1016/0165-3806(85)90116-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnstable CJ, & Tombran-Tink J.(2004). Neuroprotective and antiangiogenic actions of PEDF in the eye: Molecular targets and therapeutic potential. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 23(5), 561–577. 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra SP (2006). Focus on molecules: Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF). Experimental Eye Research, 82, 739–740. 10.1016/j.exer.2005.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra SP, Fariss RN, Wu YQ, Montuenga LM, Wong P, & Pfeffer BA (2004). Pigment epithelium-derived factor in the monkey retinal pigment epithelium and interphotoreceptor matrix: Apical secretion and distribution. Experimental Eye Research, 78(2), 223–234. 10.1016/j.exer.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra SP, & Notario V.(2013). The effects of PEDF on cancer biology: Mechanisms of action and therapeutic potential. Nature Reviews Cancer, 13(4), 258–271. 10.1038/nrc3484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra SP, Sagasti A, Spinella P, & Notario V.(1995). Pigment epithelium-derived factor behaves like a noninhibitory serpin. Neurotrophic activity does not require the serpin reactive loop. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270(43), 25992–25999. 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein JE, & Sato GH (1979). Growth of a rat neuroblastoma cell line in serum-free supplemented medium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 76(1), 514–517. 10.1073/pnas.76.1.514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouck N.(2002). PEDF: Anti-angiogenic guardian of ocular function. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 8(7), 330–334. 10.1016/S1471-4914(02)02362-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai J, Jiang WG, Grant MB, & Boulton M.(2006). Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits angiogenesis via regulated intracellular proteolysis of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(6), 3604–3613. 10.1074/jbc.M507401200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayouette M, Smith SB, Becerra SP, & Gravel C.(1999). Pigment epithelium-derived factor delays the death of photoreceptors in mouse models of inherited retinal degenerations. Neurobiology of Diseases, 6(6), 523–532. 10.1006/nbdi.1999.0263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Yang J, Geng H, Li L, Li J, Cheng B, Ma X, Li H, & Hou L.(2019). Photoreceptor degeneration in microphthalmia (Mitf) mice: partial rescue by pigment epithelium-derived factor. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 12(1), dmm035642. 10.1242/dmm.035642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comitato A, Subramanian P, Turchiano G, Montanari M, Becerra SP, & Marigo V.(2018). Pigment epithelium-derived factor hinders photoreceptor cell death by reducing intracellular calcium in the degenerating retina . Cell Death & Disease, 9, 560. 10.1038/s41419-018-0613-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DW, Volpert OV, Gillis P, Crawford SE, Xu H, Benedict W, & Bouck NP (1999). Pigment epithelium-derived factor: A potent inhibitor of angiogenesis. Science, 285(7), 245–248. 10.1126/science.285.5425.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit S, Polato F, Samardzija M, Abu-Asab M, Grimm C, Crawford SE, & Becerra SP (2020). PEDF deficiency increases the susceptibility of rd10 mice to retinal degeneration. Experimental Eye Research, 198, 108121. 10.1016/j.exer.2020.108121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine V, Kinkl N, Sahel J, Dreyfus H, & Hicks D.(1998). Survival of purified rat photoreceptors in vitro is stimulated directly by fibroblast growth factor-2. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(23), 9662–9672. https://dx.doi.org/10.1523%2FJNEUROSCI.18-23-09662.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garelli A, Rotstein NP, & Politi LE (2006). Docosahexaenoic acid promotes photoreceptor differentiation without altering Crx expression. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 47, 3017–3027. 10.1167/iovs.05-1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German OL, Insua MF, Gentili C, Rotstein NP, & Politi LE (2006). Docosahexaenoic acid prevents apoptosis of retina photoreceptors by activating the ERK/MAPK pathway. Journal of Neurochemistry, 98, 1507–1520. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04061.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German OL, Monaco S, Agnolazza DL, Rotstein NP, & Politi LE (2013). Retinoid X receptor activation is essential for docosahexaenoic acid protection of retina photoreceptors. Journal of Lipid Research, 54, 2236–2246. 10.1194/jlr.M039040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Pinto A, Polato F, Subramanian P, Rocha-Muñoz A, Vitale S, de la Rosa EJ, & Becerra SP (2019). PEDF peptides promote photoreceptor survival in rd10 retina models. Experimental Eye Research, 184, 24–29. 10.1016/j.exer.2019.04.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp NM, Bouck N, & Volpert O.(2002). (2002) Pigment epithelium-derived factor is deficient in the vitreous of patients with choroidal neovascularization due to age-related macular degeneration. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 134(2), 220–227. 10.1016/S0002-9394(02)01549-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CM, Mancuso DJ, Yan W, Sims HF, Gibson B, & Gross RW (2004). Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 279, 48968–48975. 10.1074/jbc.M407841200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenealey J, Subramanian P, Comitato A, Bullock J, Keehan L, Polato F, Hoover D, Marigo V, & Becerra SP (2015). Small Retinoprotective Peptides Reveal a Receptor-binding Region on Pigment Epithelium-derived Factor. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290, 25241–25253. 10.1074/jbc.M115.645846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird DW, & Molday RS (1988). Evidence against the role of rhodopsin in rod outer segment binding to RPE cells . Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 29, 419–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalczyk ER, Chen L, Fine D, Zhao Y, Mascarinas E, Grippo PJ, & DiPietro LA (2018). Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) as a regulator of wound angiogenesis. Scientific Reports, 8, 11142. 10.1038/s41598-018-29465-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki M, Ikeda Y, Yonemitsu Y, Goto Y, Kohno R-I, Murakami Y, Inoue M, Ueda Y, Hasegawa M, Tobimatsu S, Sueishi K, & Ishibashi T.(2008). Synergistic neuroprotective effect via simian lentiviral vector-mediated simultaneous gene transfer of human pigment epithelium-derived factor and human fibroblast growth factor-2 in rodent models of retinitis pigmentosa. The Journal of Gene Medicine, 10(12), 1273–1281. 10.1002/jgm.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami Y, Ikeda Y, Yonemitsu Y, Onimaru M, Nakagawa K, Kohno R-I, Miyazaki M, Hisatomi T, Nakamura M, Yabe T, Hasegawa M, Ishibashi T, & Sueishi K.(2008). Inhibition of nuclear translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor is an essential mechanism of the neuroprotective activity of pigment epithelium-derived factor in a rat model of retinal degeneration. American Journal of Pathology, 173(5), 1326–1338. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notari L, Baladron V, Aroca-Aguilar JD, Balko N, Heredia R, Meyer C, Notario PM, Saravanamuthu S, Nueda M-L, Sanchez-Sanchez F, Escribano J, Laborda J, & Becerra SP (2006). Identification of a lipase-linked cell membrane receptor for pigment epithelium-derived factor. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 281(49), 38022–38037. 10.1074/jbc.M600353200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata N, Matsuoka M, Imaizumi M, Arichi M, & Matsumura M.(2004). Decreased levels of pigment epithelium-derived factor in eyes with neuroretinal dystrophic diseases. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 137(6), 1129–1130. 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.11.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang IH, Zeng H, Fleenor DL, & Clark AF (2007). Pigment epithelium-derived factor protects retinal ganglion cells. BMC Neuroscience, 8, 11. 10.1186/1471-2202-8-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TL, He J, Kakazu AH, Jun B, Bazan NG, & Bazan HEP (2017). Defining a mechanistic link between pigment epithelium-derived factor, docosahexaenoic acid, and corneal nerve regeneration. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292(45), 18486–18499. 10.1074/jbc.M117.801472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polato F, & Becerra SP (2016). Pigment epithelium-derived factor, a protective factor for photoreceptors in vivo. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 854, 699–706. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-3-319-17121-0_93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi LE, Lehar M, & Adler R.(1988). Development of neonatal mouse retinal neurons and photoreceptors in low density cell culture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 29, 534–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi LE, Rotstein NP, & Carri NG (2001a). Effect of GDNF on neuroblast proliferation and photoreceptor survival: Additive protection with docosahexaenoic acid. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 42(12), 3008–3015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi LE, Rotstein NP, & Carri N.(2001b). Effects of docosahexaenoic acid on retinal development: Cellular and molecular aspects. Lipids, 36(9), 927–935. 10.1007/s11745-001-0803-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi LE, Rotstein NP, Salvador G, Giusto NM, & Insua MF (2001c). Insulin-like growth factor-I is a potential trophic factor for amacrine cells. Journal of Neurochemistry, 76(4), 1199–1211. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00128.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein NP, Aveldaño MI, Barrantes FJ, & Politi LE (1996). Docosahexaenoic acid is required for the survival of rat retinal photoreceptors in vitro. Journal of Neurochemistry, 66(5), 1851–1859. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66051851.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein NP, Aveldaño MI, Barrantes FJ, Roccamo AM, & Politi LE (1997). Apoptosis of retinal photoreceptors during development in vitro: Protective effect of docosahexaenoic acid. Journal of Neurochemistry, 69(2), 504–513. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020504.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein NP, Politi LE, & Aveldaño MI (1998). Docosahexaenoic acid promotes differentiation of developing photoreceptors in culture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 39, 2750–2758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotstein NP, Politi LE, German OL, & Girotti R.(2003). Protective effect of docosahexaenoic acid on oxidative stress-induced apoptosis of retina photoreceptors. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science, 44(5), 2252– 10.1167/iovs.02-0901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele FR, Chader GJ, Johnson LV, & Tombran-Tink J.(1993). Pigment epithelium-derived factor: Neurotrophic activity and identification as a member of the serine protease inhibitor gene family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 90(4), 1526–1530. 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratikos E, Alberdi E, Gettins PG, & Becerra SP (1996). Recombinant human pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF): Characterization of PEDF overexpressed and secreted by eukaryotic cells. Protein Science, 5, 2575–2582. 10.1002/pro.5560051220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian P, Locatelli-Hoops S, Kenealey J, DesJardin J, Notari L, & Becerra SP (2013). Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) prevents retinal cell death via PEDF Receptor (PEDF-R): Identification of a functional ligand binding site. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(33), 23928–23942. 10.1074/jbc.M113.487884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian P, Notario PM, & Becerra SP (2010). Pigment epithelium-derived factor receptor (PEDF-R): A plasma membrane-linked phospholipase with PEDF binding affinity. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 664, 29–37. 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombran-Tink J, Shivaram SM, Chader GJ, Johnson LV, & Bok D.(1995). Expression, secretion, and age-related downregulation of pigment epithelium-derived factor, a serpin with neurotrophic activity. Journal of Neuroscience, 15(7), 4992–5003. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04992.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unterlauft JD, Eichler W, Kuhne K, Yang XM, Yafai Y, Wiedemann P, Reichenbach A, & Claudepierre T.(2012). Pigment epithelium-derived factor released by Müller glial cells exerts neuroprotective effects on retinal ganglion cells. Neurochemical Research, 37, 1524–1533. 10.1007/s11064-012-0747-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente-Soriano FJ, Di Pierdomenico J, García-Ayuso D, Ortín-Martínez A, Miralles de Imperial-Ollero JA, Gallego-Ortega A, Jiménez-López M, Villegas-Pérez MP, Becerra SP, & Vidal-Sanz M.(2020) Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) fragments prevent mouse cone photoreceptor cell loss induced by focal phototoxicity in vivo. International Journal of Molecular Sciences;21(19):7242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigneswara V, Berry M, Logan A, & Ahmed Z.(2013). Pigment epithelium-derived factor is retinal ganglion cell neuroprotective and axogenic after optic nerve crush injury. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 54, 2624–2633. 10.1167/iovs.13-11803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, & Raff MC (1992). Diffusible rod-promoting signals in the developing rat retina. Development, 114(4), 899–906. 10.1242/dev.114.4.899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SX, Wang JJ, Gao G, Shao C, Mott R, & Ma J.(2006). (2006) Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) is an endogenous antiinflammatory factor. The FASEB Journal, 20(2), 323–325. 10.1096/fj.05-4313fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, & Craft CM (2000). Modulation of CRX transactivation activity by phosducin isoforms. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 20(14), 5216–5226. 10.1128/MCB.20.14.5216-5226.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

A preprint was posted on bioRxiv on Jan 01, 2021 doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.01.425044

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.