Abstract

Purpose

Data specific to the epidemiology, clinical features, and management of chronic urticaria (CU) in the geriatric population remain limited and not well understood. We aim to systematically review the prevalence, clinical manifestations, treatment, and clinical course of elderly patients with CU.

Patients and methods

Original articles that included data of elderly (aged >60 years) with CU that were published until February 2021 were searched in PubMed, Scopus, and Embase using predfefined search terms. Related articles were evaluated according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations.

Results

Among the included 85 studies and 1,112,066 elderly CU patients, most (57.4%) were women. The prevalence of elderly CU in the general population ranged from 0.2–2.8%, and from 0.7–33.3% among all CU patients. Compared to adult CU, elderly CU patients had a higher percentage of wheal alone (73.9%), and lower rate of positive autologous serum skin test and atopy. Gastrointestinal diseases were the most common comorbidity (71.9%), and there was a high rate of malignancies and autoimmune diseases. Second generation H1-antihistamines were commonly used, and achievement of complete control was most often reported. Omalizumab was prescribed in 59 refractory patients, and a significant response to treatment was reported in most patients. The treatment of comorbidities also yielded significant improvement in CU.

Conclusion

Elderly CU was found to be different from adult CU in both clinical and laboratory aspects. H1- antihistamines are effective as first-line therapy with minimal side-effects at licensed doses. Treatment of secondary causes is important since the elderly usually have age-related comorbidities.

Keywords: prevalence, clinical manifestations, treatment, chronic urticaria, elderly, systematic review

Introduction

People are now living longer due to new innovations in both technology and modern medicine.1 The result has been a doubling of global life expectancy over the past century, and an increase in the aging population worldwide.2 The World Health Organization and the United Nations define elderly as age ≥60 years and age ≥65 years, respectively.3,4 Thus, elderly-specific medical care has become and will continue to be a top priority of global public health.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is one of the most common pruritic conditions in the older population.5,6 CU is characterized by the presence of recurrent wheal, with or without angioedema, occurring at least twice a week for longer than 6 weeks.7 CU can be classified into two subtypes: chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) and chronic inducible urticaria (CIndU).7 The pathogenesis of CU is still unclear, but it is thought to be related to histamine, other mediators, and cytokines that are released from activated mast cells by degranulation.7–9 Among all patient with CU, 4.1–5.5% are elderly.10−12 Moreover, several systemic and autoimmune diseases have been reported to be associated with CU in the elderly population, including hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, atopic dermatitis and other allergic diseases, cardiac and cerebral vascular disease, and cancer.11,13–20 CU can also affect various aspects of patient quality of personal and social life, including sleep disorders, anxiety and depression, sexual dysfunction, and decreased work performance.21–23

Our current understanding of CU in the elderly is still limited since the number of studies describing the clinical manifestations and responses to treatment of CU in the geriatric population with CU remains comparatively small. The International EAACI/GA2 LEN/EuroGuiDerm/APAAACI Guideline for the Definition, Classification, Diagnosis and Management of Urticaria recommends second generation H1-antihistamine (sgAH1) as the first-line treatment for CU.7 If disease control is inadequate after 2–4 weeks of treatment, increasing the dose up to 4-fold of the standard dose of sgAH1s is recommended. For antihistamine-refractory patients, omalizumab and cyclosporine (CsA) are the treatments of choice.7 However, the use of some antihistamines and other medications to treat older patients with CU can be limited due to several factors. In recalcitrant cases, other differential diagnoses related to underlying medical conditions should be considered. In an effort to bridge this knowledge gap, this systematic review was conducted to investigate the reported epidemiology, clinical features, treatments, and clinical course in elderly CU from all available studies.

Methods

Protocol and Registration

The protocol of this systematic review has been reviewed and approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board (SIRB), Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand with SIRB Protocol No. 107/2564 (Exempt), and followed the standard protocol of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).24 Studies published until February 2021 were searched in the PubMed, Scopus, and Embase databases. The search terms were “urticaria and elderly”, “urticaria and aging”, and “urticaria and geriatric”.

Eligibility Criteria for Systematic Review

Case reports, case series, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective cohort, retrospective cohort, and other types of studies that reported the epidemiology and clinical manifestation of CU in patients aged equal to or greater than 60 years were included. Due to the relatively limited number of studies of CU in the elderly, we included the studies performed in patients aged equal to or greater than 60 years, case reports and case series, aiming to collect data from available published evidence as much as possible. Treatment data was also extracted, but it was not part of the inclusion criteria (ie, studies that described only epidemiology and clinical manifestation without a description of treatment were eligible). Five investigators (KK, CR, KM, ST, and SP) independently screened all titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles. Potentially eligible articles were reviewed in full-text to determine their final eligibility. That process was also independently conducted by the same five reviewers. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus among the five reviewers.

Data Extraction

The following data were independently extracted by the same five investigators (KK, CR, KM, ST, and SP): 1) first author’s name and the year of publication; 2) number of reported patients; 3) epidemiology; 4) clinical manifestations; 5) laboratory investigations; and 6) treatment and clinical course. Response to treatment was classified into four groups, as follows: i) complete control was defined as free of symptoms on continuation of treatment; ii) marked improvement was defined as symptoms having improved considerably, but that some symptoms were still present during treatment; iii) partial improvement was defined as partial reduction of severity of symptoms during treatment; and iv) no improvement was defined as no improvement of symptoms while on medications.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics, including mean plus/minus standard deviation and number and percentage, were used to describe demographic data, clinical manifestation, prevalence, laboratory findings, treatment, and clinical course. All data were analyzed using PASW Statistics for Windows (version 18.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

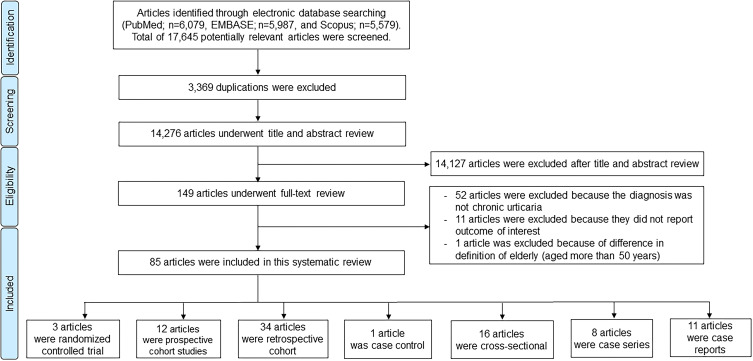

From the three databases that were searched, 17,645 articles were identified (6,079 from PubMed, 5,579 from Scopus, and 5,987 from Embase). Of those, 3,369 duplicate articles were excluded. The remaining 14,276 articles underwent title and abstract review. This process eliminated 14,127 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 149 articles underwent full-text review. Of those, 85 articles (three randomized controlled trials, 12 prospective cohort studies, 34 retrospective cohort studies, one case control study, 16 cross-sectional studies, eight cases series, and 11 case reports) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included for systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature review process in this systematic review. Eighty-five articles were suitable for the inclusion criteria and were included in our systemic review. There were three randomized controlled trials, 12 prospective cohorts, 34 retrospective cohorts, one case-control, 16 cross-sectional, eight case series, and 11 case reports.

Proportion of the Elderly Among All Patients with CU, and the Prevalence of CU Among the Elderly

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of elderly among all CU patients from a single-center cohort ranged from 0.7% to 18.0%,10,12,20,25–28 while the reported percentage in general population ranged from 14.1% to 33.3%.19,29–34 Only two studies reported the percentage of elderly among all CSU patients in the general population (15.6% and 31.5%),34,35 while the percentage of elderly among CSU patients from single-center studies ranged from 6.7% to 21.7%.20,36–42 The percentage of elderly CIndU patients was reported in five studies.32,34,43–45 The highest proportion was described in a general population study (16.3%).32 The prevalence of elderly CU in the general population was reported to range from 0.2% to 2.8%29,33,35,46 (Table 2).

Table 1.

The Reported Prevalence of Chronic Urticaria, Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria, and Chronic Inducible Urticaria in Elderly Patients Relative to All Reported Cases of These Disorders

| Study (year) | Study design | Country | Population | Elderly patients among all reported patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/Total (%) | ||||

| Chronic urticaria | ||||

| Juhlin (1981)12 | Retrospective cohort | Sweden | University Hospital | 18/330 (5.5) |

| Greene et al (1985)244 | Prospective cohort | USA | Department of Dermatology Mayo Clinic |

9/50 (18.0) |

| Mekkes et al (1986)25 | Retrospective cohort | Netherland | Dermatology clinic University Hospital |

3/109 (2.8) |

| Barlow et al (1993)26 | Retrospective cohort | UK | Urticaria clinic St John’s Dermatology Centre |

1/135 (0.7) |

| Hashiro et al (1994)27 | Cross-sectional | Japan | Outpatient clinic Hospital |

5/30 (16.7) |

| Gaig et al a (2004)29 | Cross-sectional | Spain | Spanish population National telephone directory survey |

10/30 (33.3) |

| Chen et al b (2012)19 | Retrospective cohort | Taiwan | Taiwan population National Health Insurance Research Database |

3,615/12,720 (28.4) |

| Krupashankar et al (2012)28 | Prospective cohort | India | University Hospital | 5/80 (6.3) |

| Magen et al (2013)63 | Retrospective cohort | Israel | Allergy consultation Secondary and tertiary care |

124/1,319 (9.4) |

| Ban et al (2014)11 | Retrospective cohort | South Korea | Allergy clinic University Hospital |

37/837 (4.4) |

| Chuamanochan et al (2016)10 | Retrospective cohort | Thailand | Urticaria clinic University Hospital |

67/1,622 (4.1) |

| Chu b (2017)30 | Retrospective cohort | Taiwan | Taiwan population National Health Insurance Research Database |

40,816/177,879 (23.0) |

| Eun et al (2018)31 | Prospective cohort | Korea | Korean Population National Health Insurance Service - National Sample Cohort |

447/2,980 (15.0) |

| Seo et al c (2019)32 | Retrospective cohort | Korea | Korean Population Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database |

41,882/174,579 (24.0) |

| Wertenteil et al d (2019)33 | Cross-sectional | USA | Multihealth system data analytics and research platform | 22,900/69,570 (32.9) |

| Jankowska-Konsur et ale (2019)34 | Cross-sectional | Poland | Poland Population Recruitment from multi centers all over the country |

154/1,091 (14.1) |

| Chung et al (2020)74 | Retrospective cohort | Korea | Outpatient clinic University Hospital |

26/329 (7.9) |

| Napolitano et al (2021)45 | Retrospective cohort | Italy | Dermatology unit University Hospital |

153/1,970 (7.8) |

| Chronic spontaneous urticaria | ||||

| Yang et al (2005)41 | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | Dermatological Clinics University Hospital |

5/75 (6.7) |

| Hiragun et al (2013)38 | Retrospective cohort | Japan | University Hospital | 22/117 (18.8) |

| Magen et al (2013)63 | Retrospective cohort | Israel | Allergy consultation secondary and tertiary care | 92/1,051 (8.8) |

| Vikramkumar et al (2014)42 | Cross-sectional | India | Department of Dermatology | 5/48 (10.4) |

| Lapi et al f (2016)35 | Retrospective cohort | Italy | Italian population The Health Search IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database |

4,242/13,479 (31.5) |

| Curto-Barredo et al (2018)36 | Retrospective cohort | Spain | Urticaria unit Hospital |

119/549 (21.7) |

| Nettis et al (2018)40 | Retrospective cohort | Italy | Secondary care centers | 32/322 (9.9) |

| Curto-Barredo et al (2019)37 | Retrospective cohort | Spain | Urticaria unit Hospital |

99/549 (18.0) |

| Jankowska-Konsur et al e (2019)34 | Cross-sectional | Poland | Poland Population Recruitment from multi centers all over the country |

104/667 (15.6) |

| Jo et al (2019)39 | Retrospective cohort | South Korea | University Hospital | 79/970 (8.1) |

| Chronic inducible urticaria | ||||

| Dover et al c (1988)43 | Retrospective cohort | England | Dermatology Hospital | 1/44 (2.3) |

| Katsarou-Katsari et al (2008)44 | Retrospective cohort | Greece | Skin allergy division Hospital |

10/62 (16.1) |

| Seo et al g (2019)32 | Retrospective cohort | Korea | Korean Population Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database |

3,290/20,191 (16.3) |

| Jankowska-Konsur et al e (2019)34 | Cross-sectional | Poland | Poland Population Recruitment from multi centers all over the country |

46/383 (12.0) |

| Napolitano et al (2021)45 | Retrospective cohort | Italy | Dermatology Unit University Hospital |

26/451 (5.8) |

Notes: aGaig et al conducted a population-based study among adults in Spain. Population sample was randomly selected from a national telephone directory. The phone survey was performed with each individual employing the Computer-assisted Telephone Interview technique. bThe database from National Health Insurance Research of Taiwan represented approximately 99.9% of Taiwan’s population. cDover et al reported the prevalence of delayed pressure urticaria in hospital for diseases of the skin and the dermatology institute. dElectronic health records data for a demographically heterogenous population-based sample of >55 million patients. The database is from 27 participating integrated health care organizations, representing over 55 million unique persons (17% of the population across all four census regions of the United States). eThis nationwide, multi-center, cross-sectional questionnaire-based study was performed under the auspices of the Polish Dermatological Society. Ten chronic urticaria patients were recruited by each of 102 dermatologists and allergists from different regions of Poland to achieve a good representation of patients from the whole country. fThe database from the Health Search IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database (HSD) contained the computer-based patient records from about 1,000 general practitioners (GPs) throughout Italy. Included in this study were almost 1 million electronic patient records which met standard quality criteria. They were selected on a geographical basis to represent the whole Italian population. gThe database from Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service covers 97.0% of the Korean population. Not all types of urticaria were included in the study of Seo et al. The reported subtypes of chronic inducible urticaria were cholinergic urticaria and cold/heat urticaria, as shown in this table. Prevalence of dermographism was also reported but not included in this current study, as it was not symptomatic dermographism, which is chronic inducible urticaria subtypes.

Table 2.

The Reported Prevalence of Chronic Urticaria in the Elderly Population

| Study (year) | Study design | Country | Population | Reported chronic urticaria among all elderly patients N/Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic urticaria | ||||

| Gaig et ala (2004)29 | Cross-sectional | Spain | Spanish population National telephone directory survey |

10/1,047 (1.0) |

| Lapi et alb (2016)35 | Retrospective cohort | Italy | Italian population The Health Search IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database |

13,476/488,145 (2.8) |

| Wertenteil et alc (2019)33 | Cross-sectional study | USA | Multihealth system data analytics and research platform | 22,900/9,757,210 (0.2) |

| Gaber et al (2020)46 | Prospective cohort | Egypt | Outpatient clinic University Hospital |

2/260 (0.8) |

Notes: aGaig et al conducted a population-based study among adults in Spain. Population sample was randomly selected from a national telephone directory. The phone survey was performed with each individual employing the Computer-assisted Telephone Interview technique. bThe database from the Health Search IMS Health Longitudinal Patient Database (HSD) contained the computer-based patient records from about 1,000 general practitioners (GPs) throughout Italy. Included in this study were almost 1 million electronic patient records which met standard quality criteria. They were selected on a geographical basis to represent the whole Italian population. cElectronic health records data for a demographically heterogenous population-based sample of >55 million patients. The database is from 27 participating integrated health care organizations, representing over 55 million unique persons (17% of the population across all four census regions of the United States).

Epidemiological Data

Clinical features and demographic data of the elderly with CU are summarized in Table 3. Women accounted for 57.4%, 63.9%, and 57.9% of elderly CU, CSU, and CIndU, respectively. The mean age at presentation among all CU patients was 70.4±6.2 years. Most presented with wheal alone (73.9%), followed by wheal with angioedema (25.9%). Only 0.2% presented with wheal and anaphylaxis. The average duration of disease prior to diagnosis was 1.9±3.6 years. Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and allergic dermatitis were the three most common associated atopic diseases. Cold urticaria, symptomatic dermographism, and cholinergic urticaria were found in 10.9%, 7.3%, and 3.5% of elderly CU patients, respectively.

Table 3.

The Reported Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Patients with Chronic Urticaria (CU), and Compared Between the Two Subtypes of CU – Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria and Chronic Inducible Urticaria

| Clinical features: N/Total (%) | CUa | CSU | CIndU |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1,112,066) | (N=891) | (N=1,568) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 61,170/106,669 (57.4) | 276/432 (63.9) | 873/1,509 (57.9) |

| Age at presentation, mean±SD, years | 70.4±6.2 | 71.6±6.7 | 69.9±3.8 |

| Symptoms | |||

| Wheal alone | 305/413 (73.9) | 236/312 (75.6) | NA |

| Wheal with angioedema | 107/413 (25.9) | 76/312 (24.4) | NA |

| Wheal with anaphylaxis | 1/413 (0.2) | 0/312 (0.0) | 1/1 (100.0) |

| Duration of disease prior diagnosis, mean±SD, years | 1.9±3.6 | 1.9±3.7 | NA |

| Personal history of atopyb | |||

| Allergic rhinitis | 44/233 (18.9) | 9/100 (9.0) | 9/27 (33.3) |

| Asthma | 84,519/982,862 (8.6) | 4/101 (4.0) | 2/27 (7.4) |

| Atopic Dermatitis | 57,163/985,228 (5.8) | 15/162 (9.3) | 4/27 (14.8) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis | 2/73 (2.7) | 0/7 (0.0) | 1/27 (3.7) |

| Unspecified atopy | 18/144 (12.5) | 8/105 (7.6) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Family history of atopy | |||

| Allergic rhinitis | 5/74 (6.8) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Asthma | 2/74 (2.7) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Atopic Dermatitis | 1/74 (1.4) | 0/1 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Types of chronic inducible urticaria | |||

| Cold urticaria | 18/165 (10.9) | NA | 7/154 (4.6) |

| Symptomatic dermographism | 25/344 (7.3) | NA | 25/344 (7.3) |

| Cholinergic urticaria | 1,468/42,006 (3.5) | NA | 3/124 (2.4) |

| Delayed pressure urticaria | 4/126 (3.2) | NA | 2/124 (1.6) |

| Heat urticaria | 3/154 (2.0) | NA | 2/153 (1.3) |

| Solar urticaria | 2/125 (1.6) | NA | 1/124 (0.8) |

| Aquagenic urticaria | 1/153 (0.7) | NA | 1/153 (0.7) |

| Comorbidityb,c | |||

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 708,417/985,284 (71.9) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Coronary and other vascular diseases | |||

| Cardiac/cerebral vascular diseases | 72/196 (36.7) | 52/169 (30.8) | 19/26 (73.1) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Metabolic diseases | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 3/7 (42.9) | 2/6 (33.3) | 1/1 (100.0) |

| Hypertension | 183,473/986,035 (18.6) | 103/264 (39.0) | 20/27 (74.1) |

| Obesity | 5/30 (16.7) | 0/4 (0.0) | 5/26 (19.2) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 34/271 (12.6) | 34/271 (12.6) | NA |

| Unspecified metabolic syndrome | 21/67 (31.3) | 21/67 (31.3) | NA |

| Musculoskeletal diseases | |||

| Osteoporosis | 3/7 (42.9) | 3/7 (42.9) | NA |

| Gout | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Avascular hip necrosis | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Thyroid diseases | |||

| Hyperthyroidism | 1/1 (100.0) | NA | NA |

| Hypothyroidism | 5/9 (55.6) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Grave’s disease | 4/9 (44.4) | 2/6 (33.3) | NA |

| Hashimoto’s thyroid diseases | 22/106 (20.8) | 21/105 (20.0) | NA |

| Parathyroid adenoma | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Unspecified thyroid diseases | 28/142 (19.7) | 24/116 (20.7) | 4/26 (15.4) |

| Systemic diseases | |||

| Raynaud phenomena | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | NA |

| Anemia | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Unspecified autoimmune diseases | 8/70 (11.4) | 8/69 (11.6) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| High myopia | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Genitourinary disorders | |||

| Benign prostate hyperplasia | 3/30 (10.0) | 3/30 (10.0) | 3/26 (11.5) |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 6/96 (6.3) | 6/96 (6.3) | NA |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases | 2/31 (6.5) | 1/5 (20.0) | 1/26 (3.8) |

| Psychiatric problems | |||

| Dementia | 4/67 (6.0) | 4/67 (6.0) | NA |

| Unspecified psychiatric problems | 5/130 (3.9) | 2/103 (1.9) | 2/26 (7.7) |

| Dermatologic diseases | |||

| Psoriasis | 4/96 (4.2) | 4/96 (4.2) | NA |

| Contact dermatitis | 3/96 (3.1) | 3/96 (3.1) | NA |

| Malignancy | |||

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 6/10 (60.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Genitourinary cancer | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Bronchioalveolar cancer | 2/6 (33.3) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Thyroid cancer | 2/6 (33.3) | 2/6 (33.3) | NA |

| Malignant melanoma | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Hematologic malignancy | 35/3,625 (1.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | NA |

| Unspecified malignancy | 459/3,714 (12.4) | 11/99 (11.1) | NA |

| Possible causes of urticaria | |||

| Stress | 27/99 (27.3) | 27/99 (27.3) | NA |

| Aspirin intolerance | 8/42 (2.0) | 1/5 (20.0) | 0/4 (0.0) |

| Parasitic infection | 6/129 (4.7) | 0/4 (0.0) | NA |

| Collagen vascular disease | 4/124 (3.2) | NA | NA |

| Insect bite | 3/126 (2.4) | 1/1 (100.0) | 1/27 (3.7) |

| Paronychia | 1/1 (100.0) | NA | NA |

| Unspecified drug allergy | 12/132 (9.1) | 1/8 (12.5) | NA |

| Unspecified food allergy | 1/33 (3.0) | 0/7 (0.0) | 1/26 (3.9) |

| Laboratory investigations | |||

| Positive ASST | 125/263 (47.5) | 107/195 (54.9) | 1/3 (33.3) |

| Positive SPT | 1/9 (11.1) | 0/4 (0.0) | 1/1 (100.0) |

| Positive Basophil histamine release test | 5/13 (38.5) | 4/9 (44.4) | NA |

| Leukocytosis | 4/82 (4.9) | 4/70 (5.7) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Positive HBsAg | 8/75 (10.7) | 8/68 (11.8) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Positive anti-HCV | 0/70 (0.0) | 0/68 (0.0) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Total serum IgE | |||

| Elevated IgE | 8/19 (42.1) | 7/16 (43.8) | 1/1 (100.0) |

| IgE level, mean±SD, kU/L | |||

| ImmunoCAP method (normal range 0–119 kU/L) d | 477.3±288.8 | 477.3±288.8 | NA |

| Pharmacia CAP System IgE FEIA methode (normal range 0–100 kU/L) | 164.9±210.4 | 194.5±269.7 | NA |

| Nephelometry methodf (normal range 0–100 kU/L) | 125 | 125 | NA |

| Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 22/82 (26.8) | 18/71 (25.4) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Elevated D-dimer | 2/4 (50.0) | NA | NA |

| Elevated prothrombin fragment | 3/4 (75.0) | NA | NA |

| Abnormal C3 | 0/18 (0.0) | 0/7 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Abnormal C4 | 2/18 (11.1) | 0/7 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Abnormal CH50 | 1/11 (0.0) | 0/5 (0.0) | NA |

| Abnormal C1-INH | 0/13 (0.0) | 0/7 (0.0) | NA |

| Positive antinuclear antibodies | 13/81 (16.0) | 13/69 (18.8) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Positive anticentromere antibodies | 2/2 (100.0) | NA | NA |

| Positive Anti-FcεRI antibodies | 2/3 (66.7) | 2/3 (66.7) | NA |

| Abnormal free T3 | 0/22 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Abnormal free T4 | 4/31 (12.9) | 3/20 (15.0) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Abnormal TSH | 6/33 (18.2) | 3/19 (15.8) | 0/2 (0.0) |

| Positive antithyroid peroxidase antibodies | 40/150 (26.7) | 25/110 (22.7) | 1/2 (50.0) |

| Positive antithyroglobulin antibodies | 42/124 (33.9) | 31/86 (36.1) | 0/1 (0.0) |

| Abnormal urinalysis | 10/64 (15.6) | 10/63 (15.9) | NA |

| Abnormal stool examination | 6/85 (7.1) | 4/77 (5.2) | NA |

Notes: aIt should be noted that the CU group included all CU patients aged above 60 years. Studies that reported specifically for CSU or CIndU subtypes were also included in the subgroups of CSU and CIndU. bOne patient could have more than one personal history of atopy or one comorbidity. Comorbidity and history of atopy were only showed information from papers which mentioned about each disease. cIt should be noted that the studies of Urbach, Lindelof et al, and Chen et al reported only the number of patients with malignancy, other comorbidities were not identified. dTotal IgE level measured by ImmunoCAP method were reported in three studies, Ban et al (n=37), Romano et al (n=1), and Nettis et al (n=32), which reported about CU, CSU, and CSU, respectively. Referring to the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the normal range of total IgE based on ImmunoCAP method is 0–119 kU/L. eTotal IgE level measured by Pharmacia CAP method was reported in only one study, Staubach et al (n=4), which reported about CSU. fTotal IgE level measured by Nephelometry method was reported in only one study, Kulthanan et al (n=1), which reported about CSU.

Abbreviations: Anti-FcεRI, anti-FcepsilonRI; ASST, autologous serum skin test; C3, complement C3; C4, complement C4; CH50, total hemolytic complement; C1-INH, complement 1 esterase inhibitor; CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CU, chronic urticaria; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus; Ig, immunoglobulin; NA, not available/not applicable; SD, standard deviation; SPT, skin prick test; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Severity of CU was reported in 19 studies, mostly moderate-to-severe disease activity.11,20,40,47–62 Urticaria activity score (weekly total score 42) was used in 13 studies, and the average score among all studies was 22.1±12.2.20,40,48,53–55,57–63 The other scores used to report severity were Visual Analog Scale (VAS; total score 10),54 Urticaria Activity Score (UAS; total score 9),50 Urticaria Activity Score (UAS; total score 15),11 Urticaria Severity Score (USS; total score 93),51 and Treatment Score (TS; total score 5).49,53 Twelve CSU studies reported severity using Urticaria Activity Score (UAS; weekly total score 42) with an average score among studies of 26.1±12.2.40,53–55,57–60,62 Severity of CIndU was reported in heat urticaria, which showed a temperature threshold of 38°C, and in cold urticaria which showed 22 mm for the wheal and 40 mm for the flare by cold stimulation test.52,56

Elderly CU Patients Suffer from Various Age-Related Comorbidities

The reported comorbidities of study patients are shown in Table 3. Unspecified gastrointestinal (GI) disease was the most commonly reported comorbidity among elderly CU patients (71.9%), with the majority of cases collected from a large national database (Korean Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service: HIRA).64 The reported prevalence of coronary and cerebral vascular disease were also high at 36.7%. The prevalence of dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in elderly CU patients was 42.9%, 18.6%, 16.7%, and 12.6%, respectively. Thyroid diseases were reported in 20 studies,10,20,37,45,49–51,53,61,62,65–74 and some of them were related to autoimmune disorders. For example, Grave’s disease and Hashimoto’s disease was reported in 44.4% and 20.8% of aging CU, respectively. Other common comorbidities were osteoporosis (42.9%), Raynaud phenomena (33.3%), gout (20.0%), avascular hip necrosis (20.0%), systemic lupus erythematosus (20.0%), and anemia (20.0%). Malignancies were also reported at a high rate. Most malignancies were unspecified but, among those that were specified, GI cancer was the most prevalent (60.0%). Other possible causes or aggravating factors of CU were paronychia (100.0%), stress (27.3%), unspecified drug allergy (9.1%), parasitic infection (4.7%), collagen vascular disease (3.2%), unspecified food allergy (3.0%), insect bite (2.4%), and aspirin intolerance (2.0%).

Laboratory results in Elderly with CU

As shown in Table 3, a positive autologous serum skin test (ASST) was found in 47.5% of elderly CU patients, which was less than in elderly CSU patients (54.9%). A Basophil histamine release test was reported in six studies,50,61,75–78 and the result was positive in five of 13 tested patients (38.5%). There were 22 studies that reported the level of total serum IgE, and 16 of those studies reported the IgE value. The average level among those 16 studies was higher than the normal upper limit.11,20,37,40,49,50,52,55,57,61,62,76,79–82 The other six studies reported only whether the level was elevated or not. The value was elevated in 42.1% of patients,58,69,75,83–85 and this rate was similar to the 43.8% rate reported in elderly CSU. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was increased in 26.8% and 25.4% of elderly CU and CSU, respectively. Positive D-dimer was found in 50.0% of elderly CU patients, and elevated prothrombin fragment was found in 75.0%.86 Antinuclear antibody (ANA) was reported in 13 studies10,45,51,56,58,63,65,69,79,82,83,85,87 with an average positivity rate of 16.0% among those studies. Anti-FcεRI antibody was reported in one study (66.7% positive).72 Abnormal thyroid hormone was common since it was reported in five of 21 studies.65,71–73,77 No study reported abnormal free T3, but 13.0% of elderly CU patients had abnormal free T4 hormone, and 18.2% had abnormal thyroid stimulating hormone. Twenty-four studies reported thyroid autoantibodies with a positivity rate of antithyroid peroxidase antibodies of 26.4%, and a positivity rate of antithyroglobulin antibodies of 15.6%.10,11,40,50,51,55,56,60,63,65–67,69–73,77,78,82,83,85,88,89

Treatments for CU

Among the elderly who achieved complete control with the use of AH1, sgAH1 was most often used at a regular dose (24 of 34 patients), whereas first generation H1-antihistamine (fgAH1) was prescribed at a high dose (2 of 2 patients). Side-effects of antihistamines were reported in one study. A combination of multiple high-dose fgAH1, which were hydroxyzine (dose: 25–200 mg/day), diphenhydramine (dose: 25–200 mg/day), and doxepin (dose: 25–125 mg/day), showed no additional benefit and caused severe sedation. Treatment in those cases was later changed to omalizumab.60 Omalizumab was prescribed in 15 studies. Complete control was observed in 59 of 89 patients, and the prescribed dose ranged from 150 to 300 mg every 2–4 weeks. Fifty patients from five studies received omalizumab alone.48,76,81,90,91 Others received omalizumab in combination with other treatments, including with H1-antihistamine (AH1) in seven patients from five studies,49,50,57,58,61 and systemic corticosteroid in two patients from one study.55,60 Side-effects of omalizumab were reported in three studies.62,81,90 Two patients experienced nausea, two patients reported asthenia that spontaneously resolved within 48 hours, and one patient had pain at the injection site.

Treatment of Secondary Causes Should Be Considered a Strategy for Controlling CU

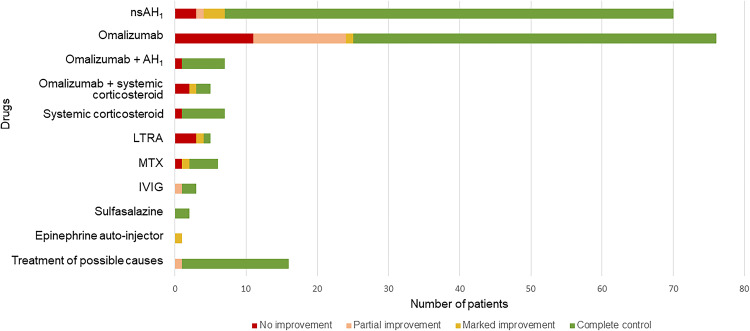

Treatment of secondary causes was also effective for controlling CU in the elderly. Thirty-nine studies described the treatment of secondary causes and the outcomes of treatment (Figure 2 and Table 4). More specifically, the following treatments, prescriptions, or procedures improved CU symptoms in the elderly: treatment for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection,63 treatment for Strongyloides infection,92 treatment for thyroid diseases,73,88 prescription of immunosuppressants for malignancies,79,83,93 prescription of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)53,54,60 or sulfasalazine to treat recalcitrant CSU,94 and surgical removal of adenoma/neoplasms.69,84,85,89,95–97

Figure 2.

Treatments and responses to treatment among elderly with chronic urticaria.

Notes: Some patients received more than one type of treatment.

Abbreviations: AH1,H1-antihistamine; fgAH1, first generation H1-antihistamine; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not available/not applicable; sgAH1, second generation H1-antihistamine.

Table 4.

The Reported Treatment for and Clinical Course of Chronic Urticaria in the Elderly

| Study (year) | N = Elderly CU/ Total | Treatment | Duration of treatment | Treatment response | Follow-up after treatment and outcome | Side-effects after treatment | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH1 | Corticosteroids | LTRA | Omalizumab | Immunosuppressant | Others | |||||||||

| fgAH1 | sgAH1 | Unspecified AH1 | Systemic | Topical | ||||||||||

| Prospective Cohort Studies | ||||||||||||||

| Leznoff et al (1983)67 | N = 1 of 17 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Levothyroxine (dose: 0.2 mg/d) for euthyroid patient who had autoimmune thyroiditis | NA | Partial improvement | NA | NA |

| Rumbyrt et al (1995)88 | N = 1 of 7 | NA | NA | NA | Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: NA) with no improvement | NA | NA | NA | NA | Previous use of - Famotidine (dose: NA) with no improvement - Doxepin (dose: NA) with no improvement -Thyroxine (0.05 mg/d) for euthyroid patient who had autoimmune thyroiditis |

At least 4 weeks | Complete control then discontinued thyroxine | Longer than 1 year of rare hive, with use of Hydroxyzine (dose: NA, as needed) | NA |

| O’Donnell et al (1998)54 | N = 1 of 10 | NA | - Cetirizine (dose: 10 mg twice daily) | Previous use of 0 (dose: NA) with no improvement | NA | NA | NA | NA | No | - IVIG (dose: 0.4 g/kg/d for 5 days) | 5 days | Partial improvement | 6 months | Headache |

| Sanada et al (2005)242 | N = 5 of 25 | NA | Previous use of - Ebastine (dose: 20 mg/d) with no improvement - Ebastine (dose: 20 mg/d) |

NA | NA | NA | - All cases: Montelukast (dose: 10 mg/d) | NA | NA | NA | NA | Complete control | NA | NA |

| NA | Previous use of - Ebastine (dose: 20 mg/d) with no improvement - Ebastine (dose: 20 mg/d) |

Previous use of - Betamethasone (dose: 0.5 mg/d orally) with no improvement |

Marked improvement | |||||||||||

| Previous use of - Hydroxyzine (dose: 50 mg/d) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Homochlorcyclizine (dose: 30 mg/d) with no improvement - Homochlorcyclizine (dose: 30 mg/d) |

NA | No improvement | |||||||||||

| NA | Previous use of - Olopatadine (dose: 20 mg/d) with no improvement - Olopatadine (dose: 20 mg/d) |

Previous use of - Betamethasone (dose: 0.5 mg/d orally) with no improvement |

No improvement | |||||||||||

| NA | Previous use of - Loratadine (dose: 10 mg/d) - Ebastine (dose: 10 mg/d) with no improvement - Loratadine (dose: 10 mg/d) - Ebastine (dose: 10 mg/d) |

NA | No improvement | |||||||||||

| Kaplan et al a (2008)50 | N = 2 of 12 | - Hydroxyzine (dose: 25–50 mg every 6 hours as needed, total 100–175 mg/d) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - All cases: Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks | No | NA | 4 months | No improvement | NA | NA |

| - Hydroxyzine (dose: 25–50 mg every 6 hours as needed, total 175 mg/d in the first 4 week then tapered dose until stop at week 8) | Complete control | |||||||||||||

| Uysal et al (2014)61 | N = 3 of 27 | NA | All cases: - Desloratadine or fexofenadine; (dose: recommended dose for 3–4 times) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks then extend to 5 weeks | Previous use of - MTX (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | 112 days | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | NA | NA |

| - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks then extend to 7 weeks | Previous use of - AZA (dose: NA) with no improvement |

78 days | ||||||||||||

| - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks then extend to 7 weeks | Previous use of - AZA (dose: NA) with no improvement |

62 days | ||||||||||||

| Retrospective cohort studies | ||||||||||||||

| McGirt et al (2006)94 | N = 2 of 19 | Previous use of - Hydroxyzine (dose: maximum 25 mg nightly) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Cetirizine (dose: maximum 10 mg/d) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 10 mg/d for 3 days; 2–3 times) with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: 10 mg/d once for 5 months) |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Sulfasalazine (dose: start at 500 mg/d then increased by 500 mg each week until 2 g/d) for total 12 months | 12 months | Complete control then tapered off of sulfasalazine, sgAH1 | 3 months | NA |

| NA | Previous use of - Cetirizine (dose: 10 mg/d) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Prednisolone dose pack (dose: NA) for 5 courses with no improvement |

- Sulfasalazine (dose: start at 500 mg/d then increased by 500 mg each week until 2 g/d) for total 11 months | 11 months | Complete control then discontinued sulfasalazine | NA | ||||||||

| Perez et al (2010)241 | N = 1 of 16 | NA | Previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, dose: above the recommended dose) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 20 mg/d) with no improvement | NA | NA | NA | Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) with no improvement - MTX (dose: 5 mg weekly) |

Previous use of 0 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement - Folic acid (dose: 5 mg weekly) |

NA | Marked improvement | NA | NA |

| Mitzel-Kaoukhov et al (2010)53 | N = 2 of 6 | NA | Previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, dose: 4-fold of the recommended dose) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | All cases: previous use of - LTRA (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | All cases: previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Histaglobin (dose: NA) with no improvement - IVIG (dose: 2 mg/kg every 4 weeks) for 11 cycles |

10 months | Complete control then discontinued | 14 months | No |

| Previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, dose: 8-fold of the recommended dose) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: high dose) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Dapsone (dose: NA) with no improvement - IVIG (dose: 2 mg/kg every 4 weeks) for 4 cycles then remission but 4 months later |

11 months | Complete control then discontinued | 2 months then relapse occurred so IVIG was reinitiated for other 5 cycles | Impairment of pre-existing HT, disappeared after extending the treatment period of IVIG from 2 to 3 days | |||||||

| Sagi et al (2011)83 | N = 5 of 8 | All cases: previous use of - fgAH1 (unmentioned name, high dose) with no improvement |

All cases: previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, high dose) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement - Systemic corticosteroid (dose: 30–40 mg/d) for multiple courses then tapered down (dose: NA) - Systemic corticosteroid (dose: 30–40 mg/d) for multiple courses then tapered down (dose: NA) - Systemic corticosteroid (dose: 30–40 mg/d) for multiple courses then tapered down until off |

NA | NA | NA | - MTX (dose: 15 mg weekly) for 1 month then tapering down to 10 and 5 mg oral weekly for 1 and 1 month, respectively) | - Folic acid (dose: 5 mg weekly) | 3 months | Complete control then discontinued MTX and folic acid | 8 months | No |

| - MTX (dose: 15 mg weekly) for 3 months then currently in the process of tapering down to 10 mg oral weekly for 2 months, without recurrence of urticaria) | 5 months | Complete control (still in the MTX tapering process) | NA | Elevated liver enzyme (Twice the normal values) – resolved after reducing MTX dosage | ||||||||||

| - MTX (dose: 15 mg oral weekly) for 3 months | 3 months | Complete control then discontinued MTX and folic acid | 2 months | No | ||||||||||

| - MTX (dose: 7.5 mg oral weekly) for 2 months | 2 months | No improvement then discontinued MTX and folic acid due to poor compliance | 2 months | Fatigue | ||||||||||

| - MTX (dose: 15 mg oral weekly) for 1 month then change to 15 mg IM weekly for 4 months | 5 months | Complete control then tapering MTX down but relapse occurred and required a constant dose of MTX 15 mg/week | NA | Gastrointestinal discomfort – resolved after changing to MTX IM route | ||||||||||

| Magen et al (2013)20 | N = 49 of 92 | - fgAH1 (unmentioned name; dose: NA) in 8 of 46 patients |

- sgAH1 (unmentioned name; dose: NA) in 49 of 49 patients |

NA | - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) in 2 of 49 patients | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 12 months | Complete control in 34 of 46 patients | NA | NA |

| Magen et al (2013)63 | N = 1 of 9 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Amoxicillin (dose: 2 g/d) - Clarithromycin (dose: 1 g/d) - Omeprazole (dose: 40 mg/d) for treatment of H. pylori infection |

2 weeks | Complete control then discontinued H. pylori infection treatment | NA | NA |

| Song et al (2013)55 | N = 4 of 16 | NA | All cases: previous use of - Cetirizine (dose: 60–80 mg/d) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 15 mg/d) for 10 courses with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: NA) for short courses Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 10 mg/d) for >20 courses with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: NA) Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 5–20 mg/d) for >20 courses with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: NA) tapered dose then off shortly after start omalizumab Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 5–10 mg/d) for >20 courses with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: NA) tapered dose then off shortly after start omalizumab |

NA | NA | All cases: - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks |

NA | NA | 24 months | Complete control and continued with omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4–8 weeks | NA | No |

| 2 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab and went into spontaneous remission then discontinued prednisolone |

Flare of urticaria after first dose of omalizumab injection | ||||||||||||

| 2 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab | No | ||||||||||||

| 24 months | Complete control and continued with omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4–8 weeks | No | ||||||||||||

| Romano et al (2015)62 | N= 1 of 9 | Previous use of - Cinnarizine (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of -AH1 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Systemic steroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - LTRA (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

- Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks | Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | 5 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab | 42 months | Pain at injected site |

| Sugiyama et al (2015)73 | N = 2 of 40 | NA | Previous use of - Olopatadine (dose: 5 mg/d) with partial improvement - Olopatadine (dose: 5 mg/d) NA |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | All cases: - Triiodothyronine (dose: 25 g/d) for Hashimoto’s disease |

3 months | Complete control then discontinued triiodothyronine | >10 months of complete control then recurrence occurred after triggered by upper respiratory tract infection; symptom was well-controlled with olopatadine 2.5 mg/d | NA |

| NA | ||||||||||||||

| Kulthanan et al (2017)57 | N = 1 of 13 | NA | Previous use of - Desloratadine (dose: 20 mg/d) - Levocetirizine (10 mg/d) with no improvement - Desloratadine (dose: 5–10 mg/d) |

NA | Previous use of - Prednisolone (5–10 mg/d) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Montelukast (dose: NA) with no improvement |

- Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks | Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) - HCQ (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of 0 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

4 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | NA | No |

| Napolitano et al (2018)93 | N = 1 of 1,493 | NA | NA | Previous use of 0 (dose: 4 times of licensed dose) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: NA) with partial improvement |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer | NA | Complete control | NA | NA |

| Napolitano et al (2021)45 | N = 26 of 451 | NA | - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, recommended dose) in 23 of 26 patients - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, double dose) in 3 of 26 patients with SD |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Complete control in 26 of 26 patients | NA | No |

| Martina et al (2021)90 | N = 62 of 62 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 4 weeks | NA | NA | 3 months | - Complete control in 44 of 62 patients - Partial improvement in 11 of 62 patients - No improvement in 7 of 62 patients |

NA | asthenia; spontaneously resolved within 48 hours (2 patients) |

| Case Series | ||||||||||||||

| Manganoni et al (2007)89 | N = 1 of 4 | Previous use of - Oxatomide (dose: 60 mg/d) with no improvement |

NA | NA | Previous use of - Betamethasone (dose: 2 mg/d orally) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: total thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma | NA | Complete control | 60 months | NA |

| Godse (2011)48 | N = 1 of 5 | NA | Previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, dose: 4 times of recommended dose) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 4 weeks | NA | NA | 4 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | NA | NA |

| Groffik et al (2011)49 | N = 1 of 9 | NA | Previous use of - sgAH1 (unmentioned name, dose: 4 times of recommended dose) with no improvement |

NA | Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (dose: NA) for long-term with no improvement |

NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 2 weeks | NA | NA | 2 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | NA | NA |

| Metz et al (2011)52 | N = 1 of 7 | NA | Previous use of - Loratadine (recommended dose) - Cetirizine (recommended dose) - Desloratadine (2–6 fold of recommended dose) - Ebastine (recommended dose) - Rupatadine (2–6 fold of recommended dose) - Levocetirizine (recommended dose) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | Previous use of - Montelukast (dose: NA) |

- Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 2 weeks | NA | Previous use of - Ranitidine (dose: NA) - Antibiotics (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

3 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab | NA | NA |

| Kirkpatrick et al (2012)51 | N = 1 of 6 | NA | NA | Previous use of 0 (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | No | - Levothyroxine (dose: 150 g/d) for hypothyroidism due to post I131 for Grave’s disease | 1 month | Complete control, then continue levothyroxine same dose | 24 months. After that, levothyroxine was tapered to 125 g/d but relapsed occurred within 3 weeks, so dose was increased to 150 g/d again; complete control | NA |

| Ivyanskiy et al (2012)76 | N = 3 of 19 | NA | NA | All cases: previous use of 0 (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | All cases: - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks |

No Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) with no improvement Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) - AZA (dose: NA) - MMF (dose: NA) with no improvement in all treatment |

No Previous use of - TNF-α inhibitor (dose: NA) with no improvement Previous use of - TNF-α inhibitor (dose: NA) with no improvement |

6 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | NA | No |

| 9 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | |||||||||||||

| 4 months | Partial improvement then discontinued omalizumab | |||||||||||||

| Armengot-Carbo et al (2013)81 | N = 5 of 15 | NA | NA | Previous use of 0 (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement NA Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement NA Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks for 3 months then 300 mg sc every 4 weeks for other 3 months | Previous use of - CsA (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of -AH2 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement Previous use of -AH2 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement Previous use of -AH2 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement NA Previous use of -AH2 (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

6 months | Partial improvement |

NA | Nausea |

| - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks for 3 months | 3 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab | Nausea | |||||||||||

| - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 2 weeks for 3 months then 150 mg sc every 4 weeks for other 3 months | 6 months | Complete control | No | |||||||||||

| - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 4 weeks for 6 months | 6 months | Complete control | No | |||||||||||

| - Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks for 3 months | 3 months | No improvement then discontinued omalizumab | No | |||||||||||

| Zubrinich et al (2019)92 |

N = 1 of 4 |

NA | NA | Previous use of - unspecified AH1 (dose: NA) with partial improvement |

Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: NA) with partial improvement |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Ivermectin (dose: NA) for treatment of Strongyloides infection | NA | Complete control | 10 months | NA |

| Case reports | ||||||||||||||

| Urbach (1942)97 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: neoplasm removal for rectal carcinoma | NA | Complete control | NA | NA |

| Anderson et al (1991)95 | N = 1 of 1 | Previous use of - Hydroxyzine (dose: NA) with no improvement |

- Terfenadine (dose: NA) | NA | Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) for short course with no improvement |

Previous use of - Hydrocortisone cream (dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: neoplasm removal for colon carcinoma | NA | Complete control | 60 months | NA |

| Amoroso et al (1997)69 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | NA | Previous use of - Betamethasone (dose: 4 mg IV) - Betamethasone (dose: 0.5 mg/d orally) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: total thyroidectomy for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis | NA | Complete control | 18 months | NA |

| Zhang et al (2004)79 | N = 1 of 1 | Previous use of - Chlorpheniramine (dose: 12 mg/d) with no improvement |

NA | NA | - Prednisolone (dose: 10 mg/d) for 3 months and 1 week | NA | NA | NA | - Melphalan (dose: 2 mg) for 1 week followed by - Cyclophosphamide (dose: 50 mg/d) for 3 months for IgA Myeloma |

NA | 3.25 months | Complete control then discontinued prednisolone, melphalan, and cyclophosphamide | NA, symptom relapsed when myeloma relapsed | NA |

| Wong et al (2010)56 | N = 1 of 1 | Previous use of - Diphenhydramine (dose: 50 mg once) with complete control |

- Cetirizine (dose: 10 mg/d) for prophylaxis | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Epinephrine auto-injector (dose: NA) | 24 months | Marked improvement but 2 months later she acquired another hymenoptera sting, and within 2 weeks developed systemic urticaria when exposing to cold temperature | NA | NA |

| Baroni et al (2012)85 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | Previous use of 0 (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Systemic corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Topical corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: radical prostatectomy for prostate adenocarcinoma | NA | Complete control | 24 months | NA |

| Hui-Hui et al (2012)84 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | Previous use of - Loratadine (dose: NA, taken once every other day) for 4 months with partial improvement |

NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: right middle lobectomy for lung cancer removal | NA | Complete control | 6 months | NA |

| Zimmer et al (2016)82 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | Previous use of -AH1 (unmentioned name, dose: up to 4 times of licensed dose) with no improvement |

NA | NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 4 weeks | NA | NA | 4 months | Marked improvement then discontinued omalizumab | 5 months, then relapse occurred | No |

| Sussman et al (2016)60 | N = 1 of 1 | Previous use of - Hydroxyzine (dose: 25–200 mg/d) - Diphen-hydramine (dose: 25–200 mg/d) - Doxepin (dose: 25–125 mg/d) with no improvement in all treatment but caused sedation |

Previous use of - Cetirizine (dose: 10–40 mg/d) - Loratadine (dose: 10 mg/d) with no improvement in all treatment - Cetirizine (dose: 20 mg/d) |

Previous use of 0 (dose: NA dosage as needed) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: 5–40 mg/d) with no improvement - Prednisolone (dose: tapering doses from before study until discontinued) |

NA | Previous use of - Montelukast (dose: 10 mg/d) with no improvement |

- Omalizumab 150 mg sc every 4 weeks | Previous use of - HCQ (dose: 400 mg/d) for 2 months - CsA (dose: 300 mg/d) for 2 months with no improvement in all treatment |

Previous use of - Ranitidine (dose: 300 mg/d) with no improvement - IVIG (dose: NA, discontinued due to hemolytic reaction) Both with partial improvement |

36 months | Marked improvement after 1 week then continued same dose of omalizumab but stopped taking prednisolone, resulting in low daily UAS7 scores. After 36 months, symptoms became severe, required longer courses and doses of prednisolone. Moreover, omalizumab was increased to 300 mg sc every 4 weeks to maintain low UAS7. | NA | NA |

| Kasperska-Zajac et al (2016)91 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | Previous use of 0 (high dose) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Prednisolone (dose: up to 15 mg) for the past 3–10 years with no improvement |

NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc | NA | NA | NA | Complete control after 1 dose of omalizumab then continued with omalizumab 150–300 mg every 5–6 weeks | NA | No |

| Aldasouqi et al (2018)96 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | - Surgery: parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism caused by large parathyroid adenoma | NA | Complete control | NA | NA |

| Pannofino (2018)58 | N = 1 of 1 | NA | - Rupatadine (dose: 10 mg twice daily) for 20 days then continue with 10 mg/d for 6 months then discontinued | Previous use of - unspecified AH1 (dose: NA) with no improvement |

Previous use of - Oral corticosteroid (unmentioned name, dose: NA) with no improvement | NA | NA | - Omalizumab 300 mg sc every 4 weeks | NA | NA | 6 months | Complete control then discontinued omalizumab | 12 months | NA |

Notes: aIt should be noted that the study of Kaplan et al included 12 CU patients (with 2 elderly patients) to be received placebo for 4 weeks and then omalizumab for 16 weeks. Omalizumab was injected every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks, dosed according to the patient’s body weight, and serum IgE at the screening visit.

Abbreviations: AH1, H1-antihistamine; AH2, H2-antihistamine; AZA, azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine; d, day; fgAH1, first generation antihistamine; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin; LTRA, Leukotriene-receptor antagonist; mg, milligram; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; NA, not available/not applicable; sc, subcutaneous; SD, symptomatic dermographism; sgAH1, second generation antihistamine; TNF-α inhibitor, tumor necrosis factor-α inhibitors; UAS7, Weekly Urticarial Activity Score.

Follow-Up Time, Tapering, Relapse, and Mean Duration of Treatment

The follow-up time after completion of treatment was mentioned in 16 studies,51,53,54,58,62,69,73,82–85,88,89,92,94,95 and the average follow-up time was 17.5 months. Some patients who had already achieved complete control continued their previous medication during the follow-up period, such as sulfasalazine and sgAH1, until they could be tapered off.94 Methotrexate (MTX) was tapered off in two patients, but one of them relapsed.83 Four patients continued to receive omalizumab maintenance at the same dose with an attempt to increase the interval between doses.55,60,91 One patient was prescribed fgAH1 as needed, but there was no report of the actual frequency of use.88 Another patient continued levothyroxine for 2 years before tapering, but relapse occurred. The dose was increased back to the initial dose and complete control was re-established.51 The average duration of treatment in this study was 205.8 days (6.9 months).

Discussion

The results of this systematic review revealed some similarities and differences between adult CU and elderly CU. Previously reported prevalence of CU in adult population ranges from 0.1% to 3.4%, which is relatively similar to the 0.2% to 2.8% prevalence of CU in the elderly.33,98 Our review also showed variation between prevalence in various geographic areas. As shown in Table 1, large population and nationwide studies showed a relatively higher prevalence of elderly in the CU population than smaller studies. However, larger studies and smaller studies reported a similar prevalence of CU in the overall elderly population (Table 2).

Even if women formed the majority of this study, which was similar to previous elderly and adult CU reports,10,11,23,99,100 some clinical presentations of elderly patients differed from adult CU. Comparison of the reported demographic and clinical characteristics of elderly patients with CU and those of non-elderly is shown in Table 5. Although the majority of both groups presented with wheal alone, its proportions in the elderly were higher than in adults, ranging from 33% to 87% across the studies, while the prevalence of concurrent angioedema was less.9,10,12,20,37,40,90 Wheal with anaphylaxis in our review was found only in one case report of the elderly with cold urticaria, which was the type that could have concurrent anaphylaxis up to 3.7–38.0%.44,101–107 CSU was the most common subtype among the elderly, similar to adult CU.10,20,26,45,108–111 Concerning CIndU, symptomatic dermographism (SD) was reported as the most common CIndU in both groups.10,20,45,74,108,112 Similar to the report of Ban et al,11 history of atopy, which is known to be associated with CU, was found at a relatively lower rate in this study than adult CU,10,11,20,37,45,64,74,90 in contrast with some previous studies.10,11,18 Regarding comorbidities, Lapi et al35 reported the risk of developing CU to be related to numerous factors. Gastrointestinal diseases, being the most common concomitant disease, together with coronary heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune diseases, thyroid diseases, psychological problems, and malignancies, were all reported at high rates in elderly CU. These findings were consistent with previous studies that reported CU to be associated with increased risk of having metabolic syndrome in both adults and the elderly.20,113–115 Moreover, the risk of developing metabolic syndrome was also found to increase with age.116,117 As reported by Zbiciak-Nylec et al118 that later onset of urticaria symptoms can result from obesity. Similar to previous studies, autoimmune diseases including autoimmune thyroid diseases, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus had been reported in high rates in all age groups of CU patients, but much more in the elderly.17,70,90,119–123 This can be a result from increasing production of autoantibodies with aging, as Ramos-Casals et al124 proposed. In addition, a previous nationwide study reported depression to be common in adult CU, while elderly CU was reported mainly in dementia and other non-specific psychological problems.100

Table 5.

Comparison of the Reported Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Elderly Patients with Chronic Urticaria (CU) with Those of Non-Elderly

| Clinical features: N/Total (%) | Elderly (our systematic review) | Non-elderly |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Data | ||

| Prevalence of CU in population | 22,900/9,757,210 (0.2) – 13,476/488,145 (2.8)29,33,35,46 | 6019/7,555,991 (0.1) – 90/2613 (3.4)9,19,29,30,33,98,134–140 |

| CSU proportion in CU | 127/153 (83.0) – 63/65 (96.9)10,20,45 | 145/220 (66.0) – 215/231 (93.1)26,34,74,108–111,141–146 |

| CIndU proportion in CU | 2/65 (3.1) – 26/153 (17.0)10,20,32,45 | 17/329 (5.2) – 75/220 (34.0)26,74,108–111,141–146 |

| Sex ratio (Male: Female) | 1: 0.9–3.310–12,20–25,30–33,37,39,40,45,90 | 1: 1.0–5.710,12,19,28–30,33,34,36–38,40,41,74,100,109,114,130,131,134,136,139,142–144,147–163 |

| Clinical presentation | ||

| Wheal alone | 10/30 (33.3) – 86/99 (86.9)10,12,20,37,40,90 | 96/330 (29.1) – 77/102 (75.5)12,20,40,107,109,136,141,143,147,149,163–168 |

| Wheal with angioedema | 13/99 (13.1) – 20/30 (66.7)10,12,20,37,40,90 | 17/248 (6.9) – 152/199 (76.4)12,28,36–40,74,109,111,120,136,141,143,147,149,158,159,163,165–173 |

| Wheal with anaphylaxis a | 1/1 (100.0)56 | 0/2,175 (0.0)28,174,175 |

| Personal history of atopy | 2/92 (2.2) – 9/26 (34.6)10,11,20,37,45,64,90 | 171/13,479 (1.3) −101/147(68.7)11,12,28,34–38,74,100,106,114,147,159,160,163,176–179 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Gastrointestinal diseases | 5/104 (4.8) – 708,415/985,278 (71.9)20,64 | 127/12,185 (1.0) – 145/330 (44.0)12,28,100,111,131,178,180–182 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 21/63 (33.3) – 44/92 (47.8)20,90 | 276/12/185 (2.3) – 1,741/11,261 (15.5)100,114,116 |

| Thyroid diseases | 1/67 (1.5) – 19/99 (19.2)10,20,37,45 | 34/13,479 (0.3) – 20/47 (42.5)12,28,30,35–37,67,70,100,153,159,165,170–172,178,183,184 |

| Autoimmune diseases | 8/63 (12.7)90 | 40/12,185 (0.3) –25/209 (12.0)30,100,153,159,170,172 |

| Psychiatric problems | ||

| Anxiety disorders | NA | 266/13,479 (2.0) – 24/30 (80.0)35,139,185–189 |

| Depression & other psychiatric problems | 2/99 (2.0) – 2/26 (7.7)37,45,65 | 121/12,185 (1.0) – 21/30 (70.0)12,30,36,37,100,139,148,154,159,185–187,189–192 |

| Malignancies | ||

| Hematologic malignancy b | 33/3,615 (0.9)19 | 80/36,910 (0.2) – 25/9,105 (0.3)18,19 |

| Other | 415/3,615 (11.5) – 11/92 (12.0)19,20 | 231/9,105 (0.3) – 330/13,479 (2.5)18,19,35,148 |

| Most common subtype of CIndU | Symptomatic dermographism10,20,45 | Symptomatic dermographism10,36,37,74,108,111,193–195 |

| Laboratory investigations | ||

| Positive antinuclear antibodies | 13/63 (20.6) of CSU10 | 248/12,778 (1.9) – 131/195 (67.2) of CSU10,120,155,158,160,196,197 |

| Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 18/63 (28.6)10 | 3/184 (1.6) – 65/133 (48.9)10,74,155,160,165,172,178,198 |

| Elevated total serum IgE c | NA | 14/330 (4.2) – 34/62 (54.8)12,28,36,74,165,199–201 |

| Positive ASST | 11/61 (18.0) – 3/5 (60.0) of CSU20,37,40,42 | 12/45 (26.7) – 49/67 (73.1) of CSU10,28,36,37,40,74,108,111,130,142,150,155,156,160,168,196,202–211 |

| Abnormal thyroid function test c | NA | 20/330 (6.1) – 20/66 (30.3)12,38,67,70,78,198,212,213 |

| Abnormal free T3 c | NA | 1/56 (1.8) – 99/165 (60.0)74,214 |

| Abnormal free T4 c | NA | 97/165 (58.8)74 |

| Abnormal TSH c | NA | 2/56 (3.6) – 99/167 (59.3)74,165,171,183,214,215 |

| Positive thyroid autoantibodies | 3/24 (12.5) – 21/63 (33.3)10,11,40 | 3/79 (3.8) – 27/47 (57.5)10,11,36,40,67,70,71,73,74,106,109,120,130,153,155–157,160,161,163,165,168,170–173,183,184,196,198,199,201–203,207,209–237 |

| Positive HBsAg | 8/63 (12.7)10 | 0/121 (0.0) – 2/56 (3.6)10,28,111,128,129,192,238 |

| Duration of disease prior to diagnosis (years) | 0.2–2.039,60,67,69,79,85,87 | 3.2–6.387,172 |

| Treatment | ||

| Response to 1st line (standard dose AH1) | 17.045/99 (45.5) – 23/26 (88.5)37,38,45 | 164/516 (31.8) – 163/248 (65.9)36–39,160,170 |

| Needed 2nd line | 3/26 (11.5) – 24/96 (25.0)37,45 | 36/335 (10.8) – 199/569 (34.9)36,37,170,172 |

| Needed 3rd line | 5/32 (15.6) – 28/95 (29.5)37,40 | 36/361 (10.0) – 93/329 (28.3)36,37,40,74,108,159,172,178 |

Notes: aWheal with anaphylaxis in elderly was found in only one case report of cold urticaria. bIt should be noted that the only retrospective study which reported malignancy in population was from Chen et al cProportion of elevated IgE, abnormal thyroid function test, free T3, free T4, and TSH in elderly patients were reported in only case reports and case series. No prospective or retrospective cohort study was found.

Abbreviations: ASST, autologous serum skin test; CIndU, chronic inducible urticaria; CSU, chronic spontaneous urticaria; CU, chronic urticaria; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; NA, not available/not applicable; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

The high rate of malignancies, both hematologic and non-hematologic, in the present study may be explained by the advanced age. Most studies reported CU patients to be at high risk of developing cancers, and the incidence of cancer also increased with age.19,89,125,126 A possible mechanism is alteration of the immune system by the tumor.126 Age-appropriate malignancy screening is, therefore, strongly encouraged for early detection and treatment, which will improve the outcomes of both cancer and urticaria.89,93,97,126

The high prevalence of thyroid autoantibodies in both geriatric and adult CU suggests the relationship between CU and thyroid autoimmunity,10,11,40,67,70,120,123,127 even though this study and the previous report showed no difference of thyroid autoantibodies between the two groups.11 Focusing on infections, hepatitis B virus was the only infection in this study that was reported at higher prevalence (12.7%) than in previously reported general CU patients (0–3.6%).128,129 There was no difference in other laboratory findings, such as ESR, ANA, and total serum IgE levels. However, elderly CSU was reported to have a relatively lower proportion of positive ASST than adult CSU, as in the study by Magen et al.20

Treatment of CU in elderly patients usually follows the same guidelines as the general population. SgAH1 is recommended as the first-line treatment for elderly CU. The regular dose of SgAH1 is generally sufficient to achieve complete control in most patients, with a higher proportion of response in elderly CU than adults. This was in line with the finding of a lower rate of ASST in the elderly. As ASST positivity correlates with higher severity and longer duration of disease of CSU,127,130–132 geriatric patients may have less severe CU symptoms than adult CU, resulting in fewer associated angioedema and good response to standard treatment. Updosing to a higher dose or 4-times was also reported the good efficacy in SgAH1. For patients who fail on antihistamines, successful symptom control has been achieved by the use of omalizumab 150–300 mg every 2–4 weeks.

Some patients with autoimmune thyroiditis and hypothyroid were treated by levothyroxine, which also helps in improving urticaria.51,67,73 The risks and benefits of these third-line drugs have not been sufficiently explored and additional studies are needed.7,83 Another treatment strategy that significantly improved CU symptoms was treatment of secondary causes concurrent with standard treatments, especially in aging patients in whom autoimmune disorders, malignancies and infections are more common. A systematic review by Kolkhir et al133 found CSU to be quite common in patients with strongyloidiasis. Its pathogenesis may be due to eosinophil and complement activation leading to skin mast cell activation. Magen et al63 and Zubrinich et al92 reported an association between H. Pylori infection, Strongyloides infection, and CU. Treatment with standard antiparasitic drugs yielded complete control.63,92,133 Therefore, treatment of these associated comorbidities, including infection, might result in a better CU control.

Limitations

Most of the included articles were retrospective studies, case reports, and case series, which are inherently classified as having a lower level of evidence (Table 6). Only three randomized controlled trials were eligible to be included in the analysis, hence, the number of control groups was low. Furthermore, only a few studies had a study population consisting only of elderly patients. These limitations further underscore the potential value of this study and make clinicians more aware that more prospective studies are needed on cases of CU in the elderly.

Table 6.

Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment of Included Articles in Systematic Review

| A. Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study, year Ref | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | ||||||||||||||||||

| Staubach et al, 2016239 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kaplan et al, 2005240 | ? | ? | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| Goldsobel et al, 198668 | + | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||

| B. Non-randomized controlled trials | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Study, year Ref | Criteria | Additional criteria in the case of comparative study | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| A stated aim of the study | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective collection of data | End point appropriate to the study aim | Unbiased evaluation of end points | Follow-up period appropriate | Loss to follow-up not exceeding 5% | Prospective calculation of the study size | A control group having the criterion standard intervention | Contemporary groups | Baseline equivalence of groups | Prospective calculation of the sample size | Statistical analyses adapted to the study design | Total | |||||||||||

| Martina et al, 202190 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Napolitano et al, 202145 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Gaber et al, 202046 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Chung et al, 202074 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Seo et al, 201932 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Zubrinich et al, 201992 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Wertenteil et al, 201933 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Jankowska-Konsur et al, 201934 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Jo et al, 201939 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Curto-Barredo et al, 201937 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Eun et al, 201831 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Nettis et al, 201840 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Napolitano et al, 201893 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Chanprapaph et al, 2018160 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Curto-Barredo et al, 201836 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Pannofino, 201858 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Aldasouqi, 201896 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | ||||||||||

| Kulthanan et al, 201757 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Lee et al, 201764 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Chu et al, 201730 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Ali, 2016152 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 20 | ||||||||||

| Chuamanochan et al, 201610 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Kasperska-Zajac et al, 201691 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Lapi et al, 201635 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Zimmer et al, 201682 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | ||||||||||

| Sussman et al, 201660 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | ||||||||||

| Romano et al, 201562 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Sugiyama et al, 201573 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Uysal et al, 201461 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Ban et al, 201411 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Vikramkumar et al, 201442 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Magen et al, 201320 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Song et al, 201355 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Magen et al, 201320 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Lefevre et al, 201375 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Hiragun et al, 201238 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Armengot-Carbo et al, 201381 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Kirkpatrick et al, 201251 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 9 | ||||||||||

| Chen et al, 201219 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Krupashankar et al, 201228 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Ivyanskiy et al, 201276 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | ||||||||||

| Hui-hui et al, 201284 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 6 | ||||||||||

| Baroni et al, 201285 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Groffik et al, 201149 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Godse, 201148 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Asero et al, 201186 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Sagi et al, 201183 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Metz et al, 201152 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Mitzel-Kaoukhov et al, 201053 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Mozena et al, 201072 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Perez et al, 2010241 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Wong et al, 201056 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | ||||||||||

| Staubach et al, 200980 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Kaplan et al, 200850 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 19 | ||||||||||

| Katsarou-Katsari et al, 200844 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Feibelmann, 200771 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Manganoni et al, 200789 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 7 | ||||||||||

| Cebeci et al, 200670 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| McGirt et al, 200694 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Sanada et al, 2005242 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Yang et al, 200541 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| O’Donnell, 200577 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Gaig et al, 200429 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Zhang et al, 200479 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | ||||||||||

| Asero et al, 200378 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| O’Donnell, 199854 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Amoroso, 199769 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | ||||||||||

| Rumbyrt et al, 199588 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | ||||||||||

| Hashiro et al, 199427 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | ||||||||||

| Barlow et al, 199326 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||

| Anderson, 199195 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | ||||||||||

| Lindelof et al, 1990148 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | 10 | ||||||||||