Abstract

A chromosome-level genome assembly of the bread wheat variety Chinese Spring (CS) has recently been published. Genome-wide identification of regulatory elements (REs) responsible for regulating gene activity is key to further mechanistic studies. Because epigenetic activity can reflect RE activity, defining chromatin states based on epigenomic features is an effective way to detect REs. Here, we present the web-based platform Chinese Spring chromatin state (CSCS), which provides CS chromatin signature information. CSCS includes 15 recently published epigenomic data sets including open chromatin and major chromatin marks, which are further partitioned into 15 distinct chromatin states. CSCS curates detailed information about these chromatin states, with trained self-organization mapping (SOM) for segments in all chromatin states and JBrowse visualization for genomic regions or genes. Motif analysis for genomic regions or genes, GO analysis for genes and SOM analysis for new epigenomic data sets are also integrated into CSCS. In summary, the CSCS database contains the combinatorial patterns of chromatin signatures in wheat and facilitates the detection of functional elements and further clarification of regulatory activities. We illustrate how CSCS enables biological insights using one example, demonstrating that CSCS is a highly useful resource for intensive data mining. CSCS is available at http://bioinfo.cemps.ac.cn/CSCS/.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42994-021-00048-z.

Keywords: Bread wheat, Chinese Spring, Chromatin state, Epigenetics, Database

Introduction

Bread wheat is a global staple food crop that has a large allohexaploid genome. There are abundant regulatory elements in the large noncoding regions. The recent release of a chromosome-level genome assembly for the bread wheat variety Chinese Spring (CS), together with whole-genome identification of gene models, has provided important opportunities for in-depth study of genetic regulatory mechanisms (International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium 2018). Regulatory elements (REs) are DNA elements that can regulate proximal or distant gene activity (Weber 2016; Ong and Corces 2011). Genome-wide identification of REs can facilitate mechanistic studies, especially for large-genome species. Given the short length and degenerative features of REs, detection of REs merely based on the DNA sequence is far from accurate, particularly in large-genome species. In eukaryotic genomes, epigenetic features including DNA accessibility and histone modifications play essential roles in regulating gene activity, and the combinatorial patterns of multiple epigenetic markers across the genome, i.e. chromatin states, are indicative of RE regulatory activity (Cuvier and Fierz 2017; Taudt et al. 2016). ChromHMM has been widely used to identify chromatin states in various animals and plants. In human T cells, 38 epigenomic data sets were integrated to define 51 distinct chromatin states, including promoter-associated, transcription-associated, active intergenic, large-scale repressed and repeat-associated states (Ernst and Kellis 2010, 2012a). A series of chromatin state definition strategies have been developed, including TreeHMM (Biesinger et al. 2013), GATE (Yu 2013), diHMM (Marco et al. 2017), hiHMM (Sohn 2015) and SegWay (Libbrecht 2015). In barley, nine histone modification-associated data sets were used to examine the interplay between chromatin state and gene expression, which revealed a higher-order structure defined by H3K27me1 and H3K27me3 abundance (Baker 2015). In bread wheat, 15 epigenetic data sets were generated and integrated to define the chromatin state and further detect genome-wide REs (Li 2019a).

In this study, we present Chinese Spring chromatin state (CSCS), a platform that provides chromatin state analysis for bread wheat by integrating 15 recently published epigenomic data sets from CS. We defined 15 chromatin states using ChromHMM and provide detailed information for each state and these data sets. Customized analysis tools for new data such as chromatin state distribution, SOM mapping and comparison, GO and motif analysis and JBrowse visualization are also provided in CSCS.

Materials and methods

Integration and processing of epigenomic data sets

A total of 15 recently published wheat epigenomic data sets (Li 2019a), including DNase-seq and ChIP-seq data sets, were collected. These data sets provided essential information including DNA accessibility and histone modifications. The sequencing data were processed as previously described (Li 2019a). In short, the sequencing reads were cleaned using Trim Galore (version 0.4.4) (Martin 2011) and Trimmomatic (version 0.36) (Bolger et al. 2014), Burrows-Wheeler Aligner-MEM (version 0.7.5a-r405) (Li and Durbin 2009) was used to align the remaining clean reads to the reference genome (IWGSC reference sequence, version 1.0), and then the mapped reads were filtered using criteria described in Li (2019a) to ensure homolog specificity and accuracy. MACS (version 1.3.7) was used to call read-enriched regions. The computeMatrix and plotProfile functions in deepTools (Ramírez 2014) were used to analyze and visualize the distribution of epigenomic marks around transcription start sites (TSSs) and transcription termination sites (TTSs).

Wheat chromatin state definition

The previously developed ChromHMM (version 1.17) software (Ernst and Kellis 2012), which is based on a multivariate Hidden Markov Model, was used to aggregate the multiple chromatin marks into genome segments representing various combinatorial presence/absence patterns, which were defined as chromatin states. The LearnModel command of ChromHMM was used to construct a chromatin state model and genome segmentation using binarized data obtained from the aligned reads, and the OverlapEnrichment command of ChromHMM was used to calculate the fold enrichments of chromatin states relative to genomic features and transposable elements. To determine the optimal number of chromatin states, CompareModels was used to compare different models. According to the results, 18 was the most appropriate number, but 3 of the 18 chromatin states have almost no epigenetic markers (please refer to states 16–18 in Fig.S1), so the final number of chromatin states was set to 15.

Self-organization mapping (SOM) training

The bigWigAverageOverBed command of the UCSC Genome Browser was used to calculate the average signal value of each epigenomic mark in each segment, which was used for self-organizing map training using the ERANGE software (Version 3.3) (Mortazavi 2008). The size of SOM maps was set to 30 by 45. The trails parameter was set to 10, and the timestep parameter was set to one-third of the numbers of segments.

In SOM analysis of uploaded bigWig files, the bigWigAverageOverBed command was used to calculate the average signal value of the input data in each segment, and then the mapsom command in the ERANGE software was used to map the new data to the trained SOM map, and the diffmap command was used for SOM comparison for two epigenomic data sets.

Custom analysis of chromatin state distribution

Users can obtain the chromatin state distribution for genome-wide intensities (bigwig files) or functional genomic loci (BED files). For genomic signal analysis, the bigWigAverageOverBed command was used to calculate the average signals of input genomic intensities in each chromatin state segment, and then the groupby program in BEDTools was used to get the chromatin state distribution by calculating the average signals for each chromatin state. For genomic loci analysis, the intersect program in BEDTools was used to calculate the overlapped regions between input loci and segments in chromatin states, and then the groupby program in BEDTools was used to calculate the chromatin state distribution.

Correlation analysis for epigenomic data sets

The plotCorrelation command in the deepTools software was used to calculate the Spearman’s correlation coefficient between input genomic signals and epigenomic data sets in our database, and the results were visualized as a heatmap.

Motif analysis

Motif analysis for input genes or genomic loci was provided by Plant Regulomics (Ran 2020) with the suggested calculation method. In short, the motifs present in 1000-bp windows centered at the peak center or transcription start site (TSS) of genes were scanned using the MotifScan software (Sun 2018), and then compared to the control regions selected from the genome. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical testing of enrichment.

GO analysis

GO (Gene Ontology) analysis for genes of interest was performed as previously published (Ran 2020). The modified Fisher’s exact test, FDR, Bonferroni correction and Benjamini–Hochberg methods were used for multiple test correction.

Database construction

The CSCS database was constructed on an Apache server based on the Linux system. PHP and JavaScript were used for the web interface, and Python and R scripts were used for data processing and statistical analysis.

Results

CSCS scheme

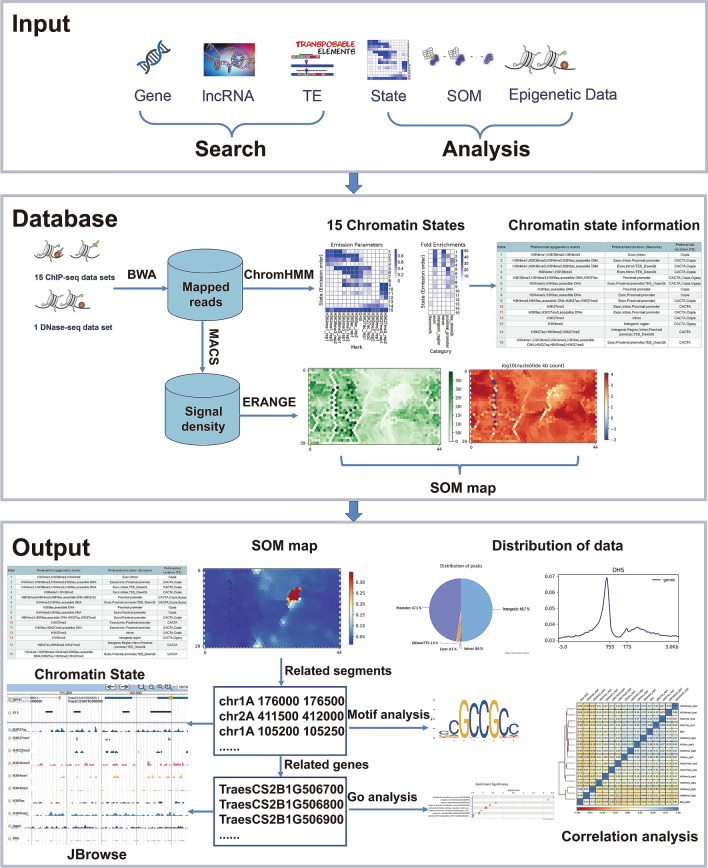

Figure 1 presents the data processing pipeline and the organization principles of CSCS. Briefly, a DNase-seq data set characterizing chromatin openness and 14 ChIP-seq data sets profiling chromatin modifications including H3K4me1, H3K36me3, H3K4me3, H3K9ac, H3K27ac, H3K9me2 and H3K27me3 were collected. The genome was partitioned into consecutive 500 bp bins, and the bins with at least one histone mark were selected, which were further classified into 15 chromatin states based on the combination of chromatin features using a multivariate Hidden Markov Model (Ernst and Kellis 2012). Table S1 summarizes the data collection statistics. For any input genes, lncRNAs and transposable elements (TEs), CSCS returns the associated chromatin states and epigenetic marks. For any input genomic signals or genomic loci, CSCS returns the chromatin state distribution for the submitted data. CSCS also provides SOM results for all collected epigenomic data sets. The chromatin bins with different chromatin architectures were mapped to a size of 1350 units of the SOM map. Each unit contained chromatin bins defined as similar states with similar chromatin signatures. Users can get the mapping results for their own data in our trained SOM maps. All the function and tools provided by CSCS were summarized on the homepage (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of CSCS

Fig. 2.

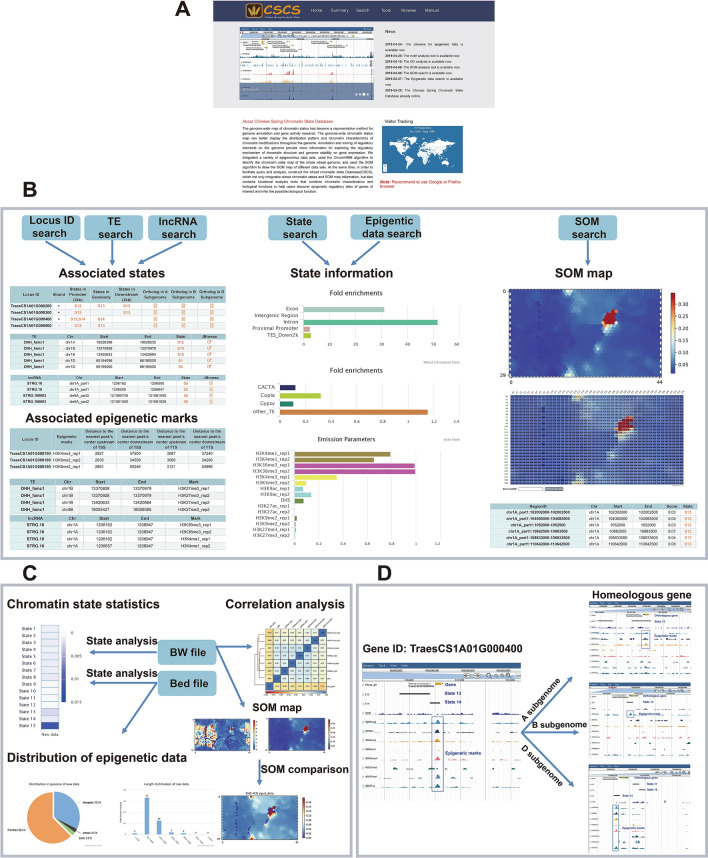

Construction of CSCS. A Homepage of CSCS. B Search function of CSCS. C Analysis tools of CSCS. D Visualization in JBrowse

Search function

CSCS accepts inputs of gene IDs, lncRNAs and TEs (Fig. 2B). For gene ID searches, the associated chromatin states in promoters, gene bodies and downstream regions of query genes are returned. Orthologues of input genes in different wheat subgenomes are also provided. The associated epigenetic marks and distance between query genes and marks are also displayed. All the epigenetic marks of query genes and their orthologues can be visualized through JBrowse. For lncRNA and TE searches, the associated chromatin state and epigenetic marks are provided, and JBrowse provides detailed visualization.

The detailed information for each state can be retrieved, including relative fold enrichment for genomic regions and TEs, and emission parameters of different epigenetic marks in this state. For epigenetic data searches, the information for processed epigenomic data sets is provided, including the data set source, emission parameters in each chromatin state, and distribution in the genome and around genes.

For SOM searches, the mapping of input epigenetic marks in our trained SOM map is returned (Fig. 2B). In the SOM map results, the regions with chromatin states and related genes in each unit could be downloaded via clicking the scores of the corresponding unit in the SOM map table. The segments in each unit can be sent to motif analysis by clicking the ‘motif analysis’ button on the page.

Analysis tools

CSCS provides analysis tools for genome-wide intensities (bigWig files), genomic loci or gene lists (Fig. 2C). When a bigWig file with genomic signals is uploaded, the genomic signal analysis tool provides the average signal in each chromatin state and the correlation of user input data with our curated data sets; all information is presented in a heatmap. In addition, the SOM analysis tool provides SOM mapping results showing units with high signals in the user input data. Moreover, users can compare two genomic signal data sets by comparing corresponding SOM maps, with manipulations including subtraction (SUB), addition (ADD), maximum (MAX) and minimum (MIN). All relevant chromatin regions can be retrieved by clicking on a unit in the resulting SOM map. Motif and GO enrichment analyses for the segments of interest and related genes in the SOM maps are also provided. When a list of genomic loci (BED file) is uploaded, the distribution of chromatin states, genomic features and lengths of the input data are listed. The motif and GO enrichment tools are also provided for input genomic loci or gene lists.

To make the platform more user-friendly, we also provide ID conversion and genomic loci conversion functions for different versions of the IWGSC reference genomes.

Visualization in JBrowse

Visualization of chromatin states and associations with genes and epigenetic marks in the genome are shown in JBrowse. All the homeologues in different wheat subgenomes related to the input gene are provided, and users can compare the detailed differences in chromatin states and epigenetic marks among the homeologues through JBrowse (Fig. 2D).

Example illustrating CSCS usage

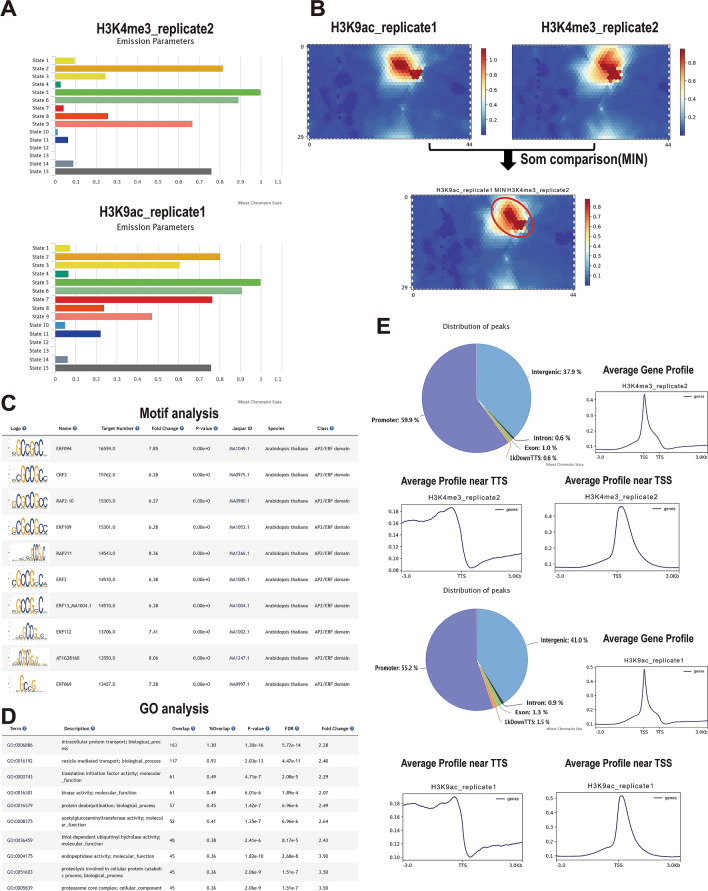

Here we show an example demonstrating the usage of CSCS. H3K4me3 and H3K9ac are epigenetic marks associated with active transcription(Ramírez-González et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2015; Wang 2009). To examine the relationship between these two histone marks, we searched epigenomic data sets associated with these two marks in CSCS. Figure 3A shows that these two marks were present in regions with similar distributions of chromatin states. Additionally, the units with high signals were similar in the SOM maps for H3K4me3 and H3K9ac (Fig. 3B). The MIN operation in the SOM compare tool was used to generate the common units based on the minimum score between H3K4me3 and H3K9ac, and are displayed in the comparative SOM map (Fig. 3B). All these results can be downloaded from CSCS. Motif analysis showed that the AP2/ERF domain binding site was the top enriched motif of the segments enriched in the common units (Fig. 3C). GO analysis of the genes related to these segments showed that they are mainly involved in transcription (Fig. 3D). These results suggested that H3K4me3 and H3K9ac target genes are associated with transcriptional regulation.

Fig. 3.

A case study of CSCS usage. A Chromatin state distribution of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 marked epigenomic data sets. B SOM comparative analysis of H3K9ac and H3K4me3. C Motif analysis results for segments in common units of the SOM maps for H3K9ac and H3K4me3. And the species column refers to the plant species in which the motif was originally identified as collected in a public database. D GO analysis results for genes related to common segments in the comparative SOM map of H3K9ac and H3K4me3. E Distribution of H3K9ac and H3K4me3 peaks in proximal and distal regions

Figure 3E displays the distribution of these two marks in relation to genes. It is worth noting that both markers have > 37% peaks localized to intergenic regions, representing putative distant regulatory elements, typically enhancers. This is consistent with studies in maize and wheat reporting the presence of H3K9ac in distant Res (Oka 2017; Li 2019b). The role of H3K4me3 in distant regulation in plants is still controversial. Previous studies in animals suggested that H3K4me3 is mostly localized in promoters (Guenther (2007)), although recent reports in mammals have indicated that H3K4me3 is also localized to super-enhancers with strong activation activity (Chen 2015). However, in plants, H3K4me3 has not been widely associated with distant regulatory activity. Here, we revealed that a large proportion of H3K4me3 localized to intergenic regions in wheat, suggesting that this mark may participate in distant gene activation in wheat.

Future plan

CSCS enables comprehensive exploration of wheat epigenomic data sets. The platform can provide clues for wheat research and link newly generated data with our collected data sets. The accuracy of RE definitions is dependent on the number of data sets integrated. We will integrate newly generated epigenomic data sets in the future, which will provide more detailed information.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 Table S1. Summary of wheat epigenomic data sets collected (XLSX 9 KB)

Supplementary file2 Figure S1. The heatmap of the emission parameters. Each row represents a different state, and each column represent a different marker for definition of 18 states. The darker blue color represents a greater probability of observing the mark in the state. (DOCX 121 KB)

Acknowledgements

We thank Huang Tao for the maintenance and help of the high-throughput computer cluster.

Funding

This study was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB27010302).

Availability of data

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Xiaojuan Ran and Tengfei Tang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Fei Zhao, Email: zhaofei@cemps.ac.cn.

Yijing Zhang, Email: zhangyijing@cemps.ac.cn.

References

- Baker K, et al. Chromatin state analysis of the barley epigenome reveals a higher-order structure defined by H3K27me1 and H3K27me3 abundance. Plant J. 2015;84(1):111–124. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesinger J, Wang YF, Xie XH. Discovering and mapping chromatin states using a tree hidden Markov model. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-S5-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, et al. Broad H3K4me3 is associated with increased transcription elongation and enhancer activity at tumor-suppressor genes. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1149–1157. doi: 10.1038/ng.3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuvier O, Fierz B. Dynamic chromatin technologies: from individual molecules to epigenomic regulation in cells. Nat Rev Genet. 2017;18(8):457–472. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2017.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kellis M. Discovery and characterization of chromatin states for systematic annotation of the human genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28(8):817–825. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J, Kellis M. ChromHMM: automating chromatin-state discovery and characterization. Nat Methods. 2012;9(3):215–216. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, et al. A chromatin landmark and transcription initiation at most promoters in human cells. Cell. 2007;130(1):77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium Shifting the limits in wheat research and breeding using a fully annotated reference genome. Science. 2018 doi: 10.1126/science.aar7191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, et al. The bread wheat epigenomic map reveals distinct chromatin architectural and evolutionary features of functional genetic elements. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):139. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1746-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li E, et al. Long-range interactions between proximal and distal regulatory regions in maize. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2633. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10603-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libbrecht MW, et al. Joint annotation of chromatin state and chromatin conformation reveals relationships among domain types and identifies domains of cell-type-specific expression. Genome Res. 2015;25(4):544–557. doi: 10.1101/gr.184341.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco E, et al. Multi-scale chromatin state annotation using a hierarchical hidden Markov model. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15011. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. Embnet J. 2011;17(1):10–12. doi: 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A, et al. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods. 2008;5(7):621–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oka R, et al. Genome-wide mapping of transcriptional enhancer candidates using DNA and chromatin features in maize. Genome Biol. 2017;18(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1273-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Corces VG. Enhancer function: new insights into the regulation of tissue-specific gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(4):283–293. doi: 10.1038/nrg2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez F, et al. deepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(W1):W187–W191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-González R, et al. The transcriptional landscape of polyploid wheat. Science. 2018;361(6403):eaaar6089. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran X, et al. Plant Regulomics: a data-driven interface for retrieving upstream regulators from plant multi-omics data. Plant J. 2020;101(1):237–248. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn KA, et al. hiHMM: Bayesian non-parametric joint inference of chromatin state maps. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(13):2066–2074. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, et al. Quantitative integration of epigenomic variation and transcription factor binding using MAmotif toolkit identifies an important role of IRF2 as transcription activator at gene promoters. Cell Discov. 2018;4(1):1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41421-018-0045-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taudt A, Colome-Tatche M, Johannes F. Genetic sources of population epigenomic variation. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(6):319–332. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, et al. Genome-wide and organ-specific landscapes of epigenetic modifications and their relationships to mRNA and small RNA transcriptomes in maize. Plant Cell. 2009;21(4):1053–1069. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.065714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B, et al. Plant enhancers: a call for discovery. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21(11):974–987. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P, et al. Spatiotemporal clustering of the epigenome reveals rules of dynamic gene regulation. Genome Res. 2013;23(2):352–364. doi: 10.1101/gr.144949.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T, Cooper S, Brockdorff N. The interplay of histone modifications—writers that read. EMBO Rep. 2015;16(11):1467–1481. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 Table S1. Summary of wheat epigenomic data sets collected (XLSX 9 KB)

Supplementary file2 Figure S1. The heatmap of the emission parameters. Each row represents a different state, and each column represent a different marker for definition of 18 states. The darker blue color represents a greater probability of observing the mark in the state. (DOCX 121 KB)