Abstract

With the rapid development of omics technologies during the last several decades, genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics have been extensively used to characterize gene or protein functions in many organisms at the cell or tissue level. However, metabolomics has not been conducted in reproductive organs, with a focus on meiosis in plants. In this study, we adopted a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based metabolomics approach to reveal the metabolic profile of inflorescences from two Arabidopsis accessions, Columbia (Col) and Landsberg erecta (Ler), and several sterile mutants caused by meiosis defects. We identified 68 dominant metabolites in the samples. Col and Ler displayed distinct metabolite profiles. Interestingly, mutants with similar meiotic defects, such as Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2, exhibited similar alterations in metabolites, including upregulation of energy metabolites and promotion of compounds related to maintenance of genomic stability, cytoplasmic homeostasis, and membrane integrity. The collective data reveal distinct changes in metabolites in Arabidopsis inflorescences between the Col and Ler wild type accessions. NMR-based metabolomics could be an effective tool for molecular phenotyping in studies of aspects of plant reproductive development such as meiosis.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43657-021-00012-3.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Meiosis, Recombination, 1H-NMR, Metabolite

Introduction

Meiosis is a highly conserved process that is required for sexual reproduction in most eukaryotes. It produces haploid gametes following one round of DNA replication with two successive cell divisions. Unlike mitosis, which produces two genetically identical daughter cells, meiosis reshuffles genetic material among progeny via meiotic recombination (Hamant et al. 2006; Mercier et al. 2015; Wang and Copenhaver 2018). It is well established that meiotic recombination is initiated by programmed double-strand breaks (DSBs), which are catalyzed by the topoisomerase-like proteins SPO11-1, SPO11-2, and TOPVIB (Grelon et al. 2001; Stacey et al. 2006; Hartung et al. 2007; Vrielynck 2016). Further resection of the DSB end generates 3 single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs, which invade either sister chromatids or homologous chromosomes (homologs) with the cooperative activities of the RAD51 and DMC1 recombinases (Li et al. 2004; Couteau et al. 1999). The Atrad51 mutant of Arabidopsis displays chromosome entanglement and fragmentation due to the failure of DSB repair (Li et al. 2004). In contrast, all DSBs in meiosis-specific Atdmc1 mutant are considered to be repaired using sister chromatids as a template, which is supported by the finding that Atdmc1 has 10 univalents without chromosome fragments (Couteau et al. 1999). Subsequently, DNA is synthesized using the invaded single end as a primer and the homologous DNA strand as a template (Huang et al. 2016). Previous studies found that Arabidopsis DNA replication factors, such as AtPOL2A (which is required for the elongation of the leading strand), AtPolα, AtPOLD1, and AtRFC1 (which are all required for the synthesis of the lagging strand), have significant functions in meiotic recombination. Similar to Atrad51, both Atrfc1 and Atpol2a fail to repair DSBs and exhibit chromosome fragments (Huang et al. 2016, 2015; Wang et al. 2012, 2019). Consequently, repair of DSBs yields crossovers (COs) or non-crossovers (NCOs). Molecular genetics studies during the past 30 years have made great progress in understanding meiotic progression, especially in meiotic recombination. However, the influence of meiotic recombination on downstream biological processes has attracted little attention.

Previous studies have shown that the metabolic status has a significant impact on meiosis. Meiotic progression requires energy consumption for the dynamic synthesis of macromolecules, including nucleic acids, proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids (Hopper et al. 1974). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the nutritional state influences the meiotic recombination rate (Abdullah and Borts 2001). Acetate sporulation medium can promote meiosis in yeast, while a glucose-rich medium is appropriate for mitosis (Ray and Ye 2013). In addition, different metabolites are required at distinct meiotic stages (Ray and Ye 2013) and meiotic differentiation requires tightly controlled reprogramming of the central metabolism to ensure proper metabolite levels in the successive developmental stages in budding yeast (Walther et al. 2014). In mice, glucose metabolism plays a key role in promoting the nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes in vitro (Herrick et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2016). Moreover, specific metabolites or metabolic pathways can generate signals that influence the initiation of meiosis (Li et al. 2020). Retinoic acid is critical for meiotic initiation in mouse germ cells (Bowles et al. 2006; Koubova et al. 2014). In humans, modulation of metabolic pathways in Sertoli cells that supply physical support and nutrients to germ cells is also important for spermatogenesis (Rato et al. 2012). These findings provide evidence that alterations in the levels of metabolites or metabolic pathways has a role in meiosis.

In addition to molecular genetics studies of meiotic progression, high-throughput analysis of meiosis, such as transcriptomics (Chen et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2011) and proteomics (Osman et al. 2013), have been widely adopted in recent years. However, few studies have employed metabolomics to systematically investigate the impact in meiosis on the metabolome (Li et al. 2020). Metabolomics analysis has become a powerful technology to comprehensively clarify plant development (Wen et al. 2015; Zhu et al. 2018) and for molecular phenotyping (Dai et al. 2010a; Ren et al. 2009; Garcia-Perez et al. 2020). Such approaches have already been successfully applied to study metabolite composition (Xiao et al. 2008; Kusano et al. 2015), systematic responses to abiotic stresses (Wang et al. 2006; Dai et al. 2010b; Zhang et al. 2011), pathogen infection (Kumar et al. 2016; Lima et al. 2010; Choi et al. 2004), and herbivore infestation in host plants (Widarto et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2017). Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H-NMR) spectroscopy features relatively high reproducibility and detectability of the analysis of metabolites with simple sample preparation. The method has become widely used to qualitatively and quantitatively analyze natural metabolic products in many plant species, including chickpea, tomato, rice, banana, apple, and cucumber (Kumar et al. 2016; Gall et al. 2003; Huo et al. 2017; Yuan et al. 2017; Francini et al. 2017; Zhao et al. 2016).

In this study, we used NMR-based metabolomics to investigate the metabolic profiles of Arabidopsis inflorescences and the metabolic differences between two wild-type (WT) accessions and multiple mutants with meiotic recombination defects. We found distinct metabolic changes between WT Columbia (Col) and Landsberg erecta (Ler), which provided a molecular phenotype for the differentiation of these two types of metabolome. We further identified the obvious differences in catabolites of these mutants compared with the WT, especially in energy metabolism and the biosynthesis of compounds related to the stability of the genome, cytoplasmic homeostasis, and the integrity of the cytomembrane. These findings extend the knowledge of the potential changes in metabolomics during reproductive development. The findings also indicate that NMR could be used to reveal metabolic phenotypes in studies of plant reproductive development, such as meiosis.

Results

Assignments for the Metabolites of Arabidopsis inflorescence

Previously, we successfully used the 1H-NMR approach to analyze metabolites in plant tissues, including the roots and leaves of chickpea (Kumar et al. 2016). In this study, we used the same method to investigate the metabolome of Arabidopsis inflorescence and annotated it with typical annotations of the one-dimensional (1D) 1H-NMR spectra and a series of two-dimensional (2D) NMR spectra (Fig. 1). The metabolite resonances were identified using both 1H and 13C data (Table S1), which were further confirmed by literature and in-house data (Fan and Lane 2008; Fan 1996; Cui et al. 2008). Our 1H-NMR data provided strong evidence that a total of 68 major metabolites were identified in Arabidopsis inflorescence. These included 16 amino acids, 11 carbohydrates, 13 organic acids, 4 amines, 9 nucleotide derivatives, 3 choline metabolites, 5 alcohols, 1 lipid, and 6 unknown metabolites (Fig. 1, Table S1). These metabolites and related metabolic pathways seemed to be active in the inflorescence. We also surveyed the expression information of genes that encode proteins associated with these dominant metabolites based on previously published transcriptome data of male meiocytes (Yang et al. 2011). As shown in Table S2, most genes encoding synthetases or catabolic enzymes of corresponding metabolites were actively expressed in meiocytes, supporting the idea that relevant metabolic pathways could be functional in meiocytes.

Fig. 1.

Representative 850 MHz 1H-NMR spectrum of Arabidopsis inflorescence extract. The X-axis represents the chemical shift of the NMR peaks. The top, middle, and bottom images are continuous spectra from 0.5 to 10 ppm. Numbers on each peak indicate each metabolite identified. U1-U6 refers to the metabolites that were undetermined by NMR and available data. Annotations with number and details of metabolites are provided in Table S1

Multivariate Data Analysis for Arabidopsis Inflorescence Extracts

To determine the statistically significant differences in metabolomics among all genotypes tested, we performed multivariate data analyses on the 1H-NMR data from two reference accessions and six mutants. Initially, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on 1H-NMR spectral data. The scores plot (Fig. 2) showed three calculated principal components (PC1, PC2 and PC3) with a total of 42.7%, 21.4%, and 1.8% of variations from the eight samples, respectively. Replicates of the samples from the same phenotypes were clustered closely together, indicating the excellent reproducibility in the sample preparations and NMR measurements. Significant differences were observed between the mutant samples and the corresponding controls. Atrad51-3, Atpol2a-2, and Atrfc1-2 displayed similar defects in meiotic recombination, and were clustered adjacent to one another, implying a potential relationship between meiosis and metabolic changes. Together, these data indicate that the 1H-NMR-based metabolomic technique is an effective approach for profiling the metabolic states of Arabidopsis inflorescence and their discrepancies among genotypes.

Fig. 2.

PCA score plot of 1H-NMR spectral data of Arabidopsis inflorescence extracts from Col-0 and Ler ecotypes and Atspo11-1–3, Atrad51-3, Atdmc1, Atrfc1-2, Atpol2a-2, Atmmd1 mutants (number of biological replicates: 7, 9, 6, 6, 9, 9, 6, and 6, respectively)

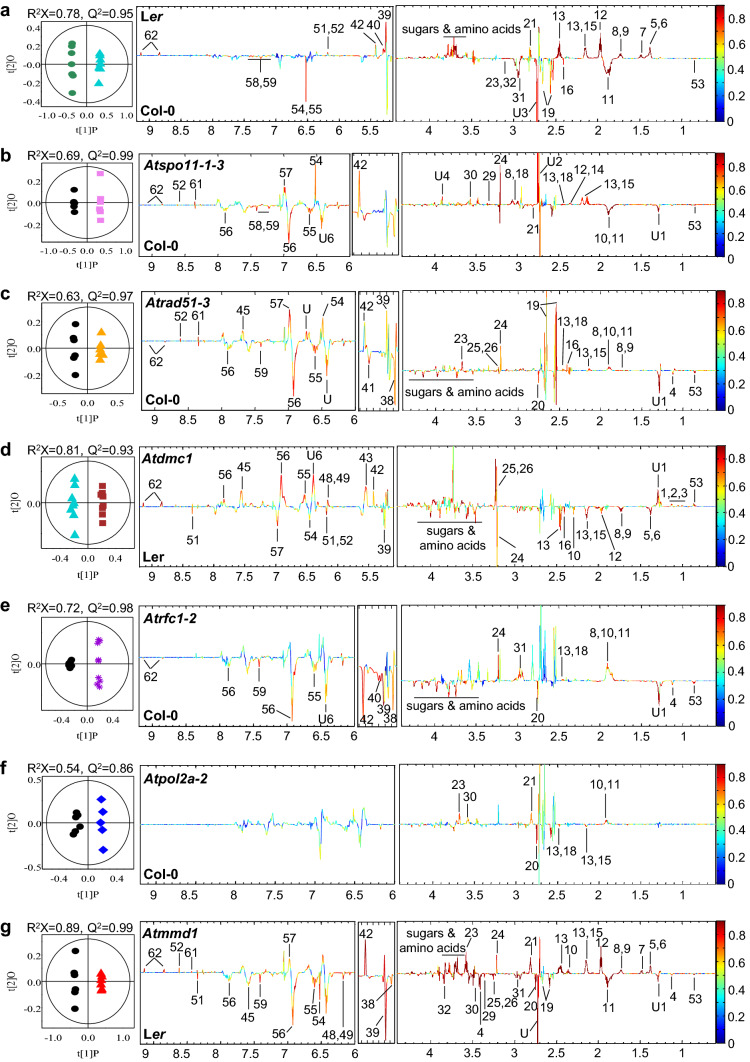

To gain a better insight into the detailed significance of metabolites contributing to the alteration, we conducted a pairwise comparative orthogonal projections to latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) with one orthogonal and one predictive component calculated for all models derived from two classes of samples (Fig. 3). We defined a correlation coefficient of |r|> 0.70 as the cutoff value for statistical significance based on the discrimination significance at the level of p < 0.05 (Cloarec et al. 2005). The remarkable metabolite level changes between each pair of samples are shown in Table 1. The main metabolic pathways affected by the significantly changed metabolites are presented in Fig. 4.

Fig. 3.

Pairwise comparison between mutants and correspondent controls by OPLS-DA; a, Ler vs Col-0; b, Atspo11-1–3 vs Col-0; c, Atrad51-3 vs Col-0; d, Atdmc1 vs Ler; e, Atrfc1-2 vs Col-0; f, Atpol2a-2 vs Col-0; g, Atmmd1 vs Ler. Left panels are scores plots corresponding to total metabolic profiling. The quality of the model is described by the parameters R2X, representing the total explained variation for X, and Q2, indicating the predictability of the model related to its statistical validity. Right panels are loading plots corresponding to differential metabolites contributing to the class discrimination. The variables in the loading plots with a warm color (e.g., red) have more significant contributions to intergroup differences than those with a cool color (e.g., blue). Annotation with number and details of metabolites are provided in Fig. 1 and Table S1

Table 1.

Significantly changed metabolites in the inflorescence of Arabidopsis thaliana compared to the correspondent controls

| Metabolite | Ler vs Col-0 R2X = 0.78 Q2 = 0.95 |

Atspo11-1–3 vs Col-0 R2X = 0.69 Q2 = 0.99 |

Atrad51-3 vs Col-0 R2X = 0.63 Q2 = 0.97 |

Atdmc1 vs Ler R2X = 0.81 Q2 = 0.93 |

Atrfc1-2 vs Col-0 R2X = 0.72 Q2 = 0.98 |

Atpol2a-2 vs Col-0 R2X = 0.54 Q2 = 0.86 |

Atmmd1 vs Ler R2X = 0.89 Q2 = 0.99 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipid | − 0.83a | − 0.85 | − 0.85 | + 0.86 | − 0.85 | – | − 0.85 |

| Amino acids | |||||||

| Isoleucine | – | – | – | + 0.76 | – | – | – |

| Leucine | – | – | – | + 0.78 | – | – | – |

| Valine | – | – | – | + 0.81 | – | – | – |

| Threonine | + 0.92 | – | – | − 0.85 | – | – | + 0.90 |

| Alanine | + 0.93 | – | – | – | – | – | + 0.91 |

| Lysine | + 0.85 | – | + 0.84 | − 0.89 | + 0.81 | – | + 0.89 |

| Citrulline | + 0.85 | – | + 0.84 | − 0.89 | – | – | + 0.89 |

| Arginine | − 0.93 | − 0.90 | + 0.85 | – | + 0.80 | + 0.75 | − 0.92 |

| Glutamate | + 0.92 | + 0.79 | – | − 0.85 | – | – | + 0.95 |

| Glutamine | + 0.91 | + 0.83 | + 0.81 | − 0.86 | + 0.75 | − 0.75 | + 0.97 |

| Methionine | + 0.91 | + 0.83 | + 0.81 | − 0.86 | – | − 0.75 | + 0.97 |

| Histidine | – | + 0.72 | – | − 0.83 | – | – | + 0.78 |

| Tyrosine | − 0.84 | − 0.78 | – | – | – | – | + 0.74 |

| Phenylalanine | − 0.82 | − 0.79 | − 0.79 | – | – | – | − 0.82 |

| Aspartate | + 0.83 | − 0.78 | – | – | – | + 0.81 | + 0.93 |

| Organic acids | |||||||

| 4-aminobutyrate | – | − 0.90 | + 0.85 | − 0.75 | + 0.80 | + 0.75 | + 0.91 |

| Lactate | + 0.92 | – | – | − 0.85 | – | – | + 0.90 |

| Succinate | − 0.83 | – | + 0.82 | − 0.82 | – | – | – |

| 2-ketoglutarate | – | + 0.79 | + 0.76 | – | + 0.73 | − 0.72 | – |

| Citrate | − 0.80 | – | + 0.86 | – | – | – | − 0.81 |

| Fumarate | − 0.88 | – | − 0.73 | + 0.80 | − 0.70 | – | − 0.83 |

| Formate | – | + 0.76 | + 0.73 | – | – | – | + 0.81 |

| Cis-aconitic acid | − 0.88 | + 0.76 | + 0.74 | − 0.70 | – | – | − 0.83 |

| Amines | |||||||

| Dimethylamine | – | – | − 0.83 | – | − 0.84 | − 0.78 | − 0.91 |

| Dimethylglycine | − 0.90 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Ethanolamine | − 0.90 | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.91 |

| Choline metabolites | |||||||

| Choline | – | + 0.86 | + 0.78 | − 0.80 | + 0.74 | – | + 0.88 |

| Phosphocholine (PC) | – | – | + 0.80 | + 0.83 | – | – | − 0.86 |

| GPC | – | – | + 0.80 | + 0.83 | – | – | − 0.86 |

| Alcohol | |||||||

| O-methyl scyllo-insitol | − 0.80 | – | – | – | – | + 0.83 | + 0.90 |

| Ethanol | – | – | − 0.81 | – | − 0.82 | – | − 0.95 |

| Methanol | – | + 0.77 | – | – | – | – | − 0.84 |

| Inositol | – | + 0.73 | – | – | – | + 0.75 | − 0.94 |

| Carbohydrate | – | ||||||

| Fructose | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Trehalose | – | – | − 0.73 | – | − 0.72 | – | − 0.83 |

| α-glucose | + 0.88 | – | + 0.69 | − 0.71 | − 0.82 | – | − 0.91 |

| α-arabinose | + 0.84 | – | – | – | − 0.88 | – | – |

| α-galactose | – | – | − 0.81 | – | – | – | – |

| Sucrose | + 0.78 | + 0.73 | + 0.70 | + 0.70 | − 0.85 | – | + 0.89 |

| UDP-glucose | – | – | – | + 0.75 | – | – | – |

| Aglycone | – | − 0.77 | − 0.76 | + 0.82 | − 0.71 | – | − 0.85 |

| Nucleoside | – | ||||||

| Uridine monophosphate | – | – | – | + 0.81 | – | – | + 0.83 |

| Cytidine monophosphate | – | – | – | + 0.81 | – | – | + 0.83 |

| Uracil | – | – | + 0.75 | + 0.77 | – | – | − 0.73 |

| Inosine | + 0.77 | – | – | − 0.79 | – | – | − 0.80 |

| Inosine monophosphate | + 0.77 | + 0.64 | + 0.73 | − 0.79 | – | – | + 0.81 |

| Methyl-nicotinate | + 0.89 | + 0.72 | − 0.76 | + 0.90 | − 0.68 | – | + 0.88 |

aCorrelation coefficient values obtained from OPLS-DA of treatment groups

+ and − indicate a significant increase and decrease, respectively, of metabolite levels in the treatment groups compared to the controls; − no change

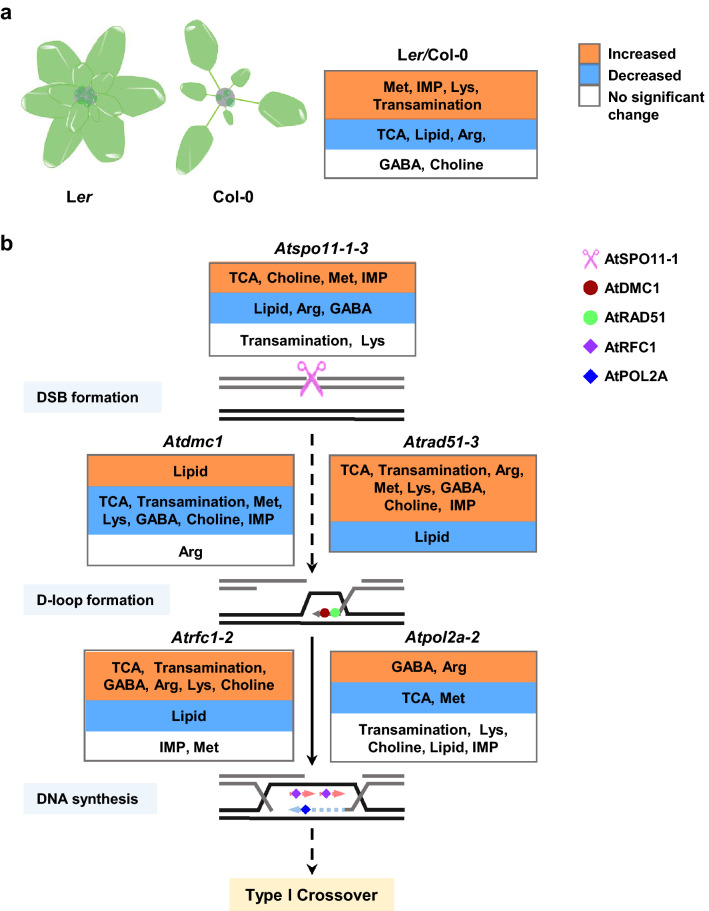

Fig. 4.

Metabolic changes between the mutants and correspondent controls obtained from OPLS-DA. Metabolites with orange boxes denote significant increases and those with blue boxes denote significant decreases. The bold-lettered metabolites were detected in this study. Metabolite identities are listed in the abbreviations list

Metabolic Difference Between the Two Accessions of Col-0 and Ler

Since the six mutants used here were generated from the two accessions of Col-0 and Ler respectively, we first compared the metabolome differences between the two reference accessions. The OPLS-DA loading plot indicated a distinct metabolic difference between Ler and Col-0 (Fig. 3a). Twenty-six metabolites showed significant changes between these two accessions. These differences were emphasized by the significant elevation of carbohydrates (sucrose, glucose, and arabinose), transamination-related metabolites (Asp, Gln, and Glu), and nucleoside metabolites (inosine and inosine monophosphate (IMP)), and by the reduction of lipids, tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates (citrate, cis-aconitic acid, a-ketoglutarate, succinate, and fumarate) and shikimate-mediated metabolites (Phe and Tyr) in the Ler background (Figs. 3a and 4). In addition, Ler seemed to be more active in transamination and the synthesis of purine metabolites and amino acids of the pyruvate family (Ala) and aspartate family (Lys, Thr, and Met) (Fig. 4). We then compared the 26 catabolites with the 36 previously identified different catabolites using ultra-performance liquid chromatography to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF MS) -based untargeted metabolic fingerprinting of crude acetone extracts from inflorescences collected from WT accessions Col-0 and Ws-3 (Sotelo-Silveira et al. 2015). Only two catabolites (phenylalanine and sucrose) overlapped. Moreover, a comparison of the 26 catabolites with the reported differential catabolites from leaves between Ler and Col-0 using 1H-NMR (Ward et al. 2003) revealed overlaps only with fumarate and glucose. Taken together, the result did reflect the potential difference in catabolites between Col and Ler. The differential metabolites between Col-0 and Ler could be used as controls for subsequent comparisons among mutants.

Metabolic Profiling of Atspo11-1–3 Defective of Double Strand Break Formation and Fertility

As described above, meiotic recombination begins with the programmed DSB generated by AtSPO11-1. The Atspo11-1 mutant harbored 10 univalents instead of the five bivalents in the WT, due to the inability to form DSB. This results in the failure of homolog pairing, synapsis, and recombination, thus leading to sterility (Grelon et al. 2001). We first compared the metabolites between Col-0 and the Atspo11-1–3 mutant. The score plot and loading plot displayed a significant metabolic difference (Fig. 3b). The levels of sucrose and TCA cycle intermediates (cis-aconitic acid and α-ketoglutarate) were significantly higher in Atspo11-1–3 than in Col-0, suggesting a possibly enhanced activity of the TCA cycle. Additionally, the decreased contents of Phe and Tyr in Atspo11-1–3 (Fig. 4) indicated a decrease in shikimate metabolism through which the aromatic amino acids Phe and Tyr are produced. Regarding transamination metabolites and related derivatives, the levels of Glu and Gln were increased and the levels of Asp, 4-aminobutyrate (GABA), and Arg were decreased in Atspo11-1–3 (Fig. 4). Considering the increase in α-ketoglutarate and cis-aconitic acid, and the reduction of GABA and Arg, the results indicated that in Atspo11-1–3 most transamination products fed into the TCA cycle. In addition, other detected alterations included the elevation of Met, choline, His, IMP, formate and methyl nicotinate and the reduction of lipids (Fig. 4).

Metabolic Changes in Atrad51-3 and Atdmc1 Mutants

In Arabidopsis, AtRAD51 plays a critical role in DNA repair in both meiotic and somatic cells (Li et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2014). The Atrad51 mutant is sterile and shows chromosome fragmentation due to the failure of DSB repair (Li et al. 2004). The Atdmc1 mutant is sterile and has 10 univalents without chromosome fragmentation (Couteau et al. 1999). All DSBs are thought to be repaired using sister chromatids as a template. Compared with the corresponding control, the scores and coefficient-coded loadings plots showed that both AtRAD51 and AtDMC1 had significant effects on the metabolome in inflorescence (Figs. 3c, d). Similar to the metabolites affected by AtSPO11-1, the sucrose content and its decomposition products including glucose, citrate, cis-aconitic acid, a-ketoglutarate, and succinate, were also increased in Atrad51-3 (Figs. 3c, 4). In contrast, most of the sugar metabolites, excluding sucrose, were reduced in Atdmc1, indicating a weaker ability to catabolize sucrose in Atdmc1. The increases in Leu, Val, and Ile in Atdmc1 imply that more pyruvate is transformed into alanine amino acids instead of entering the TCA cycle (Fig. 4). Meanwhile, the level of lipid had the opposite change tendency compared with the TCA cycle intermediates in either Atdmc1 or Atrad51-3, suggesting that in both mutants, the TCA cycle might promote the degradation of lipids, since acetyl-CoA, the main degradation product of lipid, is the precursor of the TCA cycle (Fig. 4). In addition to sugar metabolism, Atrad51-3 and Atdmc1 also exhibited different or even opposite changes in other metabolic pathways, such as the transamination, choline metabolism and nucleotide metabolism pathways (Fig. 4). For example, in Atrad51-3, the transamination activity was enhanced, as indicated by the elevation of Gln content (Fig. 4). At the same time, the enhancement of the transamination activity likely promoted the synthesis of related derivatives. Indeed, the levels of Lys and Met derived from Asp were increased and the levels of GABA and Arg, synthesized with Glu as a precursor, were also increased in Atrad51-3 (Figs. 3c, 4). However, all these metabolites showed a reduced or unchanging tendency in Atdmc1. Regarding choline metabolites, choline levels were increased in both Atrad51-3 and Atspo11-1–3, but decreased in Atdmc1 (Fig. 4). Considering the contrasting changes in choline and its degradation product, dimethylamine (DMA), we hypothesized that the catabolism of choline could be inhibited in Atrad51-3 (Fig. 4). Additionally, more glycolysis intermediates could be transformed into choline via phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and glycine metabolism. Moreover, similar to Atspo11-1–3, we found that the mutation of AtRAD51 led to an increase in IMP (Figs. 3c, 4). It is also noteworthy that the deletion of AtDMC1 specifically resulted in the reduction of purine metabolites (IMP and inosine) and an increase in pyrimidine metabolites, including uridine monophosphate (UMP), cytidine monophosphate (CMP) and uracil (Figs. 3d, 4), which are different from either Atspo11-1–3 or Atrad51-3. Taken together, these results indicated that AtRAD51 and AtDMC1 might have distinct roles in the metabolism of Arabidopsis inflorescence.

Metabolic Profiling Affected by AtRFC1 and AtPOL2A

We previously demonstrated that DNA replication factors, such as AtRFC1, AtPolα, AtPOL2A, and AtPOLD1, are required for meiotic recombination (Huang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2012, 2019). Here, we analyzed the effects of AtRFC1 and AtPOL2A on metabolism. Both AtRFC1 and AtPOL2A are essential for mitosis, and their null alleles are lethal for embryos. The two Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2 mutants used in this study are weak alleles, which have relatively normal vegetative growth, but are defective in meiotic recombination (Huang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2012). As shown in Fig. 4, Atrfc1-2 significantly decreased sucrose content, suggesting a lower ability to transfer sucrose to inflorescences, or an enhanced ability to metabolize sucrose. Meanwhile, the other metabolic processes were very similar between Atrfc1-2 and Atrad51-2 (Figs. 3c, e), consistent with the similar phenotypes in the meiotic defects of the two mutants. Compared with Col-0, the TCA cycle could be activated in Atrfc1-2, as supported by the increased level of TCA intermediate a-ketoglutarate, which is similar to Atspo11-1–3 and Atrad51-3 but opposite to Atdmc1 (Figs. 3b-d). In Atrfc1-2, we found elevated levels of Gln, an indicator of transamination activity, and increased levels of GABA, Arg, and Lys (Fig. 4), possibly due to the enhancement of transamination activity. This was also similar to the alterations observed in Atrad51-3, but all metabolites showed the opposite tendency or no significant change in Atdmc1 (Fig. 3d). In addition, similar to Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 also had elevated choline content and reduced ethanol and methyl-nicotinate levels (Fig. 4). Accordingly, some reactions may have been weakened to reduce ethanol synthesis in Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2. Additionally, we also identified some other metabolites altered in Atrad51-3, but not in Atrfc1-2, such as purine and pyrimidine metabolism (Fig. 4).

In Atpol2a-2, a relative minority of metabolites was significantly altered compared with Col-0 (Fig. 3f and Table 1). However, the altered metabolites, including the increased GABA and Arg, and the decreased DMA in Atpol2a-2 were also similar to either Atrad51-3 or Atrfc1-2 (Fig. 4). Together, these results suggest that metabolic profiling changes in Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2 inflorescences are more similar to each other.

Similarity and Difference of Metabolic Changes Among Atspo11-1–3, Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2 Mutants

The above analyses focused on the metabolites affected by individual genes. Since the genes we selected have some common or distinct roles in the meiotic process, such as recombination, it was of interest to determine whether the similarity or difference in the function of the genes can be associated with the alteration of metabolites or related pathways. We performed pairwise comparative OPLS-DA among the Atspo11-1–3, Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2 mutants (Fig. S1). The significantly altered metabolites are listed in Table S3. These analyses did not include Atdmc1. On the one hand, the background of Atdmc1 was Ler, which differed from the other four Col-0 mutants. On the other hand, based on the initial comparison (Fig. 4), Atdmc1 showed a distinct pattern of metabolic changes compared with the other mutants.

As mentioned above, Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2 failed to repair DSBs, and showed similar chromosome fragmentation morphologies. First, we compared the metabolome of Atspo11-1–3 with those of Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2 (Figs. S1a–c). In particular, the levels of Met and choline in Atrad51-3 were higher than those in Atspo11-1–3 (Fig. S1a and Table S3). Among the decreased levels of metabolites, we found shikimate-mediated metabolites (Phe and Tyr) and pyrimidine metabolites (UMP, uracil, and CMP) in Atrad51-3 vs Atspo11-1–3. When we compared either Atrfc1-2 or Atpol2a-2 with Atspo11-1–3, more aspects were similar to each other (Figs. S1b-c), consistent with the association of meiotic defects with similar chromosome meiotic behaviors. Specifically, the levels of Met, Lys, choline, and IMP were higher in both Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2 than in Atspo11-1–3 (Figs. S1b–c and Table S3), similar to the situation in Atrad51-3. Taken together, these data agree with the similar defects in fertility and meiosis in Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2 mutants. We further compared the metabolomes of Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2. Very few metabolic changes were detected (Figs. S1d–e and Table S3). These findings suggest that AtRAD51, AtRFC1, and AtPOL2A may have a similar effect on metabolite production in Arabidopsis inflorescence. Given that Atspo11-1–3 is also sterile, the greater similarity observed among Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2 likely correspond to the potential correlation between the indicator metabolites and genes with similar gene functions.

Distinct Metabolic Profiling Affected by a Specific Meiotic Histone Reader AtMMD1

Both mitosis and meiosis require chromosome condensation, which is mediated by the condensin complex (Kalitsis et al. 2017). In Arabidopsis, the PHD finger protein AtMMD1/AtDUET is required for the progression of meiotic chromosome condensation and directly regulates the expression of the condensin gene CAP-D3 (Wang et al. 2016; Andreuzza et al. 2015). In Atmmd1, the formation and repair of DSBs seem to be unaffected, but there are defects in chromosome condensation during diakinesis and metaphase I followed by cell death before cytokinesis (Wang et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2003). Analysis of metabolic alterations caused by Atmmd1 (Fig. 3g), we found that Atmmd1 showed reduced TCA activity (Fig. 4), as observed in Atdmc1, but was completely different from those in Atspo11-1–3, Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2 (Figs. 3b-e). Although Atmmd1 showed similar changing trends in specific metabolites, the variation tendencies of the corresponding upstream or downstream intermediates were comparable. For example, Atmmd1 showed a similar elevation of transamination activity to Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2, but the increased activity in Atmmd1 did not lead to an increase in Arg (Fig. 4). In addition, similar to Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2, increased GABA levels were also found in Atmmd1 (Fig. 4). However, the increase in GABA was accompanied by unchanged Glu in Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2 and Atpol2a-2, suggesting a positive transformation from Glu to GABA. In contrast, in Atmmd1, the increase in GABA was accompanied by an increase in the Glu level and a decrease in Arg and TCA intermediates (Fig. 4), indicating a negative transformation from Glu to GABA. We also found increased levels of Met and Lys in Atmmd1, which is similar to the changes observed in all other mutants (Fig. 4, Table S3). Although the choline level in Atmmd1 was increased as in Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2, the ethanolamine (EA) level was only decreased in Atmmd1 (Fig. 4). These findings indicated that the defect in the transformation from choline to EA contributes to the increase of choline in Atmmd1. Increased IMP levels were also found in Atmmd1, accompanied by an increase in UMP and CMP, and reduced levels of inosine and uracil (Fig. 4), suggesting that the transformation of nucleoside monophosphate into nucleoside by removing a phosphate molecule could be inhibited in Atmmd1. Additionally, we did not find a reduction in inosine and uracil in Atmmd1 as observed in Atrad51-3, Atrfc1-2, and Atpol2a-2 (Figs. 3c, e–f), suggesting that the accumulation of IMP in these mutants is different within Atmmd1 (see “Discussion” for details). The collective findings indicate that although Atmmd1 is defective in meiosis, it has a unique phenotype of meiocyte cell death, which could be a major reason for the different changes in metabolites compared with other mutants.

Discussion

An NMR-based metabolomics approach revealed distinct metabolic changes between the inflorescences of two Arabidopsis accessions, Col and Ler, compared to several meiosis-defective mutants. Due to the low sensitivity of NMR (Garcia-Perez et al. 2020), the samples we used were inflorescences covering stages 1–12. The difference in metabolites between Col and Ler inflorescences reflects the true developmental difference. These two genotypes had distinct patterns of apical inflorescences (Fig. 5a). The major difference between Col and Ler is that Ler is an Aterecta mutant (Torii et al. 1996). Aterecta encodes a receptor kinase and may play a role in regulating catabolism in inflorescences. As sink organs, most of the carbohydrates in the inflorescences are transferred from leaves as sucrose and then degraded through the TCA cycle (Chen et al. 2012; Sweetlove et al. 2010). Compared with Col, increased sucrose, but decreased TCA cycle intermediates, were found in Ler inflorescences, suggesting that the compact inflorescence of Ler might have less ability to catabolize carbohydrates. The elevation of transamination-related metabolites might indicate an enhancement of nitrogen utilization efficiency in Ler. Our results also reveal that the metabolism of meiosis-defective mutants is significantly changed compared with that in the WT. Although we realized that the majority of the samples were non-meiocytes, we cannot preclude those changes that likely occurred after meiosis and the gene expression information demonstrated that the relevant metabolic pathways are active in meiocytes. There is still a possibility that these changed metabolites may be caused by gene mutations or the disturbance of gene expression in the mutants, which have direct and indirect roles in meiosis and post-meiotic pollen development, respectively. Specifically, mutants showing similar meiotic defects usually exhibit similar changes in their metabolites. To simplify the metabolic phenotypes affected by ecotypes and the genes examined, we integrated the major altered metabolites into the two accessions and the classical meiotic DSB repair (DSBR) model (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Integration of metabolic change with the phenotypic difference between the inflorescences of Ler and Col-0, and the DSBR model. a Phenotypic difference between inflorescences of Ler and Col-0, and the metabolic change in the inflorescences of these two ecotypes. b Integration of metabolic profile into the DSBR model. Meiotic recombination is a conserved process that initiates from the formation of DSBs catalyzed by AtSPO11-1. A 3′ single-strand DNA overhang is produced by resecting the DSB ends. The overhang can invade into a non-sister chromatid with the help of AtRAD51 and AtDMC1 to form a D loop. AtPOL2A and AtRFC1 assist in synthesizing the leading strand and lagging strand, respectively, in the Type I CO pathway. Metabolites in the orange boxes denote significant increases in relevant recombination-defective mutants. Metabolites in blue boxes denote significant decreases and those in white boxes represent no significant change. Metabolite identities are listed in the abbreviation list

According to the DSBR model, meiotic recombination initiates from the programmed DSBs generated by SPO11 in various organisms, including plants. Our metabolomics data revealed obvious metabolic differences between Atspo11-1–3 and Col-0, highlighted by the increased levels of TCA intermediates, choline, Met, and IMP, and by the reduced levels of lipid, Arg and GABA (Fig. 5). The findings indicate that the loss of DSB affects sugar, lipid, protein, and nucleic acid metabolism. The underlying mechanism is unclear and requires further investigation.

Following the formation of DSBs, the DSB ends are further resected by the Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1 (MRN) protein complex to yield 3′ ssDNA tails and form nucleoprotein filaments with RAD51 and DMC1. These mediate the invasion of ssDNA into the double helix of a homolog to form a D loop (Wang and Copenhaver 2018). RecA-related recombinases, such as RAD51 and DMC1, are highly conserved in eukaryotes. RAD51 is required for both mitosis and meiosis, whereas DMC1 is thought to be meiosis-specific. Regarding the metabolomics data, in Atdmc1, there was a decrease in metabolites related to TCA and transamination accompanied by the downregulation of GABA, Met, Lys, choline, and IMP, and the upregulation of lipids (Fig. 5). In contrast, all these metabolites showed the opposite change in Atrad51-3 (Fig. 5). The finding agreed with their clearly different meiotic phenotype in chromosome behavior. The comparison of Atrad51-3 with Atspo11-1–3 revealed a similar upregulation of TCA-related metabolites and a reduced lipid level, consistent with the fact that lipid degradation has a feedback mechanism to promote TCA activity. We also observed increased IMP and unchanged inosine, the degradation product of IMP, in Atspo11-1–3 and Atrad51-3 (Fig. 4). A previous study in mice demonstrated that the accumulation of IMP could lead to meiotic arrest in mice (Downs 1994). Therefore, we speculate that coordinated interdependence could exist between IMP and meiosis. In organisms, IMP can be synthesized by the de novo pathway via 5-phosphoribosyl diphosphate (PRPP) or produced from AMP through irreversible hydrolytic deamination catalyzed by AMP deaminase (Xu et al. 2005). The markedly elevated level of IMP might explain the decreased AMP in Atrad51-3 and Atspo11-1–3. Removing AMP can drive the equilibrium of 2ADP ⇌ ATP + AMP toward ATP synthesis to create a high-energy potential (Bauschjurken and Sabina 1995). Remarkably, we found the same change in increased Met and choline levels in Atrad51-3 and Atspo11-1–3. Both choline and Met were beneficial for the integrity of the membrane, as choline is the precursor of phosphatidylcholine, which is the major component of cell membranes (Stechow et al. 2013) and Met is the precursor for the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), which is also necessary for the biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine (Stechow et al. 2013). Therefore, the increased choline and Met levels may indicate a change in membrane integrity in Atspo11-1–3 and Atrad51-3. SAM also acts as a donor for the methylation of histones, DNA and RNA (Yang and Bedford 2013; Meng et al. 2018). The methylation status of histones and DNA has a direct effect on genome stability (Hale et al. 2016; Cao and Jacobsen 2002). In Arabidopsis, CO hot spots have been associated with low DNA methylation and high trimethylated histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) (Melamedbessudo and Levy 2012; Mirouze et al. 2012; Drouaud et al. 2013) indicating an interdependence between Met metabolism and CO formation. The similarity between Atdmc1 and Atspo11-1–3 is a decrease in GABA. In plants, GABA can contribute to the carbon–nitrogen balance and function as an osmoregulatory and cytosolic pH regulator (Bouché and Fromm 2004). Although Atspo11-1–3 and Atdmc1 have similar meiotic chromosome behaviors, Atspo11-1–3 shared more metabolic changes with Atrad51-3 compared with Atdmc1, suggesting that AtSPO11 and AtDMC1 have distinct roles in metabolism.

Single-end invasion facilitates DNA synthesis, AtPOL2A and AtRFC1 are required for leading and lagging strand synthesis, respectively (Huang et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2012). As indicated by PCA analysis, Atrad51-3, Atpol2a-2, and Atrfc1-2 showed similar metabolic profiles (Fig. 2), such as energy metabolism, transamination activity, choline metabolism, and levels of GABA, Arg,and Lys (Fig. 5). All three mutants showed interactions between non-homologs and chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis. Similar meiotic defects along with similar metabolic profiles suggest that the metabolic changes in these mutants might result from chromosomal fragments directly or indirectly. In addition, Atspo11-1–3 and Atdmc1 show univalent but not chromosomal fragmentation during meiosis and exhibit different metabolic changes in general with Atrad51-3, Atpol2a-2 or Atrfc1-2, further suggesting a relationship between mutant phenotypes and metabolic changes. In contrast to Atspo11-1–3 and Atdmc1, transamination activity was enhanced in Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2. Transamination has dual roles in the synthesis and degradation of amino acids in many organisms (Popov et al. 2007). The benefit of transamination is that it allows the transfer of an amino group without the formation of ammonia, which is toxic to cells (Popov et al. 2007). The alteration of transamination-related metabolites was opposite in Atdmc1 compared with those in Atrad51-3 and Atrfc1-2 (Fig. 5). Moreover, regarding Arg, which differentially expressed between Atrfc1-2 and Atdmc1 (Fig. 4), another study showed that ovarian cancer cells, with debilitated DNA repair ability, accumulated more Arg (Poisson et al. 2015), implying that Arg levels are negatively correlated with DNA repair ability in cells.

In summary, our metabolomics data provide evidence that mutants with defects in meiotic DSB repair exhibited common metabolic profiling, emphasized by the improvement of energy metabolites and promotion of the synthesis of compounds related to maintaining genomic stability, cytoplasmic homeostasis and membrane integrity. Given that meiosis is highly conserved among different organisms, the phenomena we found in plants could serve as a reference for other organisms. Moreover, we also recognized that NMR suffers from relatively poor sensitivity compared to mass-spectrometric (MS) approaches and it is difficult to collect enough meiocytes for analysis. Thus, to better understand the effect of meiotic recombination on metabolism, it is feasible to use NMR in combination with LC/GC–MS to study the metabolome in meiocytes in the future.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana plants, including two reference accessions Columbia-0 (Col-0) and Landsberg erecta (Ler), and Atspo11-1–3 (SALK_146172) (Stacey et al. 2006), Atrad51-3 (SAIL_873_C08) (Pradillo et al. 2012), Atdmc1 (Yao et al. 2020), Atrfc1-2 (SALK_140231) (Wang et al. 2012), Atpol2a-2 (Huang et al. 2015), and Atmmd1 (Yang et al. 2003), were used in this study. They were grown in soil (9:1:3, peat moss: perlite: vermiculite) at 22 °C under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark). All plants were grown simultaneously under the same environmental conditions.

Sample preparation and NMR measurements

Six to eleven biological replicates of inflorescence flowers, covering stages 1–12, were collected from the main stems of 6-week Arabidopsis plants. Each replicate was from a pot plant with approximately 60 plants. Homozygous plants for each genotype were segregated from the progenies of the heterozygous plants. The samples were then individually ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using a bead beater (Retsch GmbH, Retsch-Allee, Germany). Metabolites were extracted as previously described (Liu et al. 2017). Briefly, the powdered tissues (approximately 80 mg) were mixed with 0.6 mL of CH3OH/H2O (v/v = 2:1) and a 5 mm tungsten carbide bead was added to each sample. After vortexing, the mixture was homogenized using a Tissue Lyser (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and sonicated for 15 min in an ice bath. The supernatant was collected after centrifugation for 10 min at 16,099g at 4 °C. The above extraction procedure was repeated twice and all the supernatants were combined into one sample. After removal of methanol under vacuum, the samples were lyophilized. The freeze-dried extracts were redissolved in 0.6 mL phosphate buffer (0.1 M K2HPO4/NaH2PO4, pH 7.4) containing 80% D2O and 0.002% sodium 3-trimethlysilyl [2,2,3,3-D4] propionate (TSP). After 10 min of centrifugation (16,099g, 4 °C), 550 μL of supernatant from each sample was transferred into a 5 mm NMR tube for metabolite analysis.

1H-NMR spectra of the inflorescence extracts were acquired at 298 K on an AVIII 850 spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Germany) operating at 850.15 MHz for 1H and 212.5 MHz for 13C. A standard water-suppressed one-dimensional NMR spectrum was recorded using the noesypr1d pulse sequence (RD-90°-t1-90°-tm-90°-acquisition) with a recycle delay of 2 s and a mixing time (tm), of 80 ms. Typically, the 90° pulse length was set to approximately 10 μs and t1 was 3 μs. A total of 64 transients were collected into 32 K data points for each spectrum with a spectral width of 20 ppm. All spectra were referenced to the chemical shift of the TSP (δ0.00). For the purpose of metabolite assignment, a range of two-dimensional NMR spectra were recorded for selected samples including 1H-1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY), 1H-1H total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY), J-resolved spectroscopy (JRES), 1H-13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy (HSQC) and 1H-13C heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation (HMBC) (Kumar et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2017).

Multivariate Data Analysis

1H-NMR spectra were manually corrected for phase and baseline distortions using the TOPSPIN software (V3.0, Bruker Biospin) and the spectral region of δ 0.5–9.5 was uniformly integrated into equal buckets with width of 0.003 ppm (1.8 Hz) using the AMIX software (v3.8.3, Bruker Biospin). The region δ 4.67–5.15 was discarded for imperfect water suppression.

The spectral integration of all buckets was normalized to the weight of the extracts used for the measurements. Principal component analysis (PCA) was initially performed on the mean-centered NMR data for an overview using SIMCA-P software (v12.0, Umetrics, Umea, Sweden). The orthogonal projection to latent structure with discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) (Cloarec et al. 2005) was conducted using the NMR data as X-matrix and the class information as Y-matrix with unit variance scaling and sevenfold cross-validation. In the OPLS-DA models, score plots and loading plots correspond to total metabolic profiling and differential metabolites contributing to class discrimination, respectively. The quality of the model was described by the parameters R2X, representing the total explained variation for X and Q2, indicating the predictability of the model related to its statistical validity. The qualities of the OPLS-DA models were evaluated with the coefficient of variation (CV)-analysis of variance (ANOVA) approach, with P < 0.05 as significant (Cloarec et al. 2005). The loadings obtained from the OPLS-DA were back-transformed from NMR spectral integration of all buckets (Wang et al. 2007) and color-coded plotted with the absolute values of coefficients (|r|) using an in-house developed MATLAB script. In such a coefficient plot, the observed phase of the resonance signals represents the relative changes (increase or decrease) in the concentration of metabolites. The variables with a warm color (e.g. red) show more significant contributions to intergroup differences than those with a cool color (e.g. blue). These semi-quantitative data were statistically analyzed by classical one-way ANOVA using the SPSS software (version 13.0; IBM Corp., NY, USA) with a Tukey post-test (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yanpeng An at the School of Life Sciences of Fudan University for helpful discussions regarding the experimental data.

Abbreviations

- DSBs

Double-strand breaks

- COs

Crossovers

- NCOs

Non-crossovers

- Col-0

Columbia-0

- Ler

Landsberg erecta

- 1H-NMR

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance

- LC–MS

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

- GC–MS

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry

- PCA

Principal component analysis

- OPLS-DA

Orthogonal projection to latent structure with discriminant analysis

- COSY

Correlation spectroscopy

- TOCSY

Total correlation spectroscopy

- JRES

J-resolved spectroscopy

- HSQC

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy

- HMBC

Heteronuclear multiple-bond correlation

- Ala

Alanine

- Arg

Arginine

- α-KG

α-Ketoglutarate

- cAA

cis-Aconitic acid

- Cho

Choline

- Cit

Citrate

- DMA

Dimethylamine

- EA

Ethanolamine

- Eth

Ethanol

- Fruc

Fructose

- Fum

Fumarate

- GABA

4-Aminobutyrate

- Glc

Glucose

- Glu

Glutamate

- Gln

Glutamine

- His

Histidine

- Ile

Isoleucine

- Lac

Lactate

- Tyr

Tyrosine

- Phe

Phenylalanine

- Thr

Threonine

- Suc

Sucrose

- Succ

Succinate

- Val

Valine

- 6PGL

6-Phosphogluconate

- E-4-P

Erythrose-4-phosphate

- PRPP

5-Phosphoribosyl diphosphate

- PEP

Phosphoenolpyruvate

- Ici

Isocitrate

- F-1,6-2P

Fructose-1, 6-biphosphate

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

- IMP

Inosine monophosphate

- UMP

Uridine monophosphate

- CMP

Cytidine monophosphate

- DMA

Dimethylamine

- SAM

S-adenosylmethionine

- AMP

Adenosine monophosphate

- ADP

Adenosine diphosphate

- ATP

Adenosine triphosphate

Author contributions

YXW and LMZ designed the research; YXW, LMZ and YW performed the experiments; XL, HKW, YXW and LMZ analyzed the data; and XL and HKW drafted the manuscript. YXW and LMZ have revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation of China (31570314 and 31925005) and by funds from the State Key Laboratory of Genetic Engineering at Fudan University.

Data availability

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Xiang Li and Hongkuan Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Limin Zhang, Email: zhanglm@wipm.ac.cn.

Yingxiang Wang, Email: yx_wang@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- Abdullah MF, Borts RH. Meiotic recombination frequencies are affected by nutritional states in Saccharomy cescerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(25):14524–14529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201529598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreuzza S, Nishal B, Singh A, Siddiqi I. The chromatin protein DUET/MMD1 controls expression of the meiotic gene TDM1 during male meiosis in Arabidopsis. PLOS Genet. 2015;11(9):e1005396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauschjurken MT, Sabina RL. Divergent N-terminal regions in AMP deaminase and isoform-specific catalytic properties of the enzyme. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;321(2):372–380. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouché N, Fromm H. GABA in plants: just a metabolite? Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9(3):110. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles J, Knight D, Smith C, Wilhelm D, Richman J, Mamiya S, Yashiro K, Chawengsaksophak K, Wilson MJ, Rossant J, Hamada H, Koopman P. Retinoid signaling determines germ cell fate in mice. Science. 2006;312(5773):596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1125691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Jacobsen SE. Role of the Arabidopsis DRM methyltransferases in de novo DNA methylation and gene silencing. Curr Biol. 2002;12(13):1138–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Farmer AD, Langley RJ, Mudge J, Crow JA, May GD, Huntley J, Smith AG, Retzel EF. Meiosis-specific gene discovery in plants: RNA-Seq applied to isolated Arabidopsis male meiocytes. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LQ, Qu XQ, Hou BH, Sosso D, Osorio S, Fernie AR, Frommer WB. Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science. 2012;335(6065):207. doi: 10.1126/science.1213351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YH, Tapias EC, Kim HK, Lefeber AW, Erkelens C, Verhoeven JT, Brzin J, Zel J, Verpoorte R. Metabolic discrimination of Catharanthus roseus leaves infected by phytoplasma using 1H-NMR spectroscopy and multivariate data analysis. Plant Physiol. 2004;135(4):2398–2410. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.041012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloarec O, Dumas ME, Trygg J, Craig A, Barton RH, Lindon JC, Nicholson JK, Holmes E. Evaluation of the orthogonal projection on latent structure model limitations caused by chemical shift variability and improved visualization of biomarker changes in 1H NMR spectroscopic metabonomic studies. Anal Chem. 2005;77(2):517–526. doi: 10.1021/ac048803i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couteau F, Belzile F, Horlow C, Grandjean O, Vezon D, Doutriaux MP. Random chromosome segregation without meiotic arrest in both male and female meiocytes of a dmc1 mutant of Arabidopsis. Plant cell. 1999;11(9):1623–1634. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.9.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Lewis IA, Hegeman AD, Anderson ME, Li J, Schulte CF, Westler WM, Eghbalnia HR, Sussman MR, Markley JL. Metabolite identification via the madison metabolomics consortium database. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(2):162–164. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Xiao C, Liu H, Hao F, Tang H. Combined NMR and LC-DAD-MS analysis reveals comprehensive metabonomic variations for three phenotypic cultivars of Salvia Miltiorrhiza Bunge. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(3):1565–1578. doi: 10.1021/pr901045c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Xiao C, Liu H, Tang H. Combined NMR and LC-MS analysis reveals the metabonomic changes in Salvia miltiorrhiza bunge induced by water depletion. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(3):1460–1475. doi: 10.1021/pr900995m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SM. Induction of meiotic maturation In vivo in the mouse by IMP dehydrogenase inhibitors: effects on the developmental capacity of Ova. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;38:293–302. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080380310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouaud J, Khademian H, Giraut L, Zanni V, Bellalou S, Henderson IR, Falque M, Mézard C. Contrasted patterns of crossover and non-crossover at Arabidopsis thaliana meiotic recombination hotspots. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(11):e1003922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan WMT. Metabolite profiling by one- and two-dimensional NMR analysis of complex mixtures. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 1996;28:161–219. doi: 10.1016/0079-6565(95)01017-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan WM, Lane AN. Structure-based profiling of metabolites and isotopomers by NMR. Prog Nucl Mag Res Sp. 2008;52(2):69–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francini A, Romeo S, Cifelli M, Gori D, Domenici V, Sebastiani L. 1H NMR and PCA-based analysis revealed variety dependent changes in phenolic contents of apple fruit after drying. Food Chem. 2017;221:1206–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Perez I, Posma JM, Serrano-Contreras JI, Boulange CL, Chan Q, Frost G, Stamler J, Elliott P, Lindon JC, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. Identifying unknown metabolites using NMR-based metabolic profiling techniques. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(8):2538–2567. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-0343-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelon M, Vezon D, Gendrot G, Pelletier G. AtSPO11-1 is necessary for efficient meiotic recombination in plants. Embo J. 2001;20(3):589–600. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale CJ, Potok ME, Lopez J, Do T, Liu A, Gallego-Bartolome J, Michaels SD, Jacobsen SE. Identification of multiple proteins coupling transcriptional gene silencing to genome stability in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLOS Genet. 2016;12(6):e1006092. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamant O, Ma H, Cande WZ. Genetics of meiotic prophase I in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57:267–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartung F, Wurz-Wildersinn R, Fuchs J, Schubert I, Suer S, Puchta H. The catalytically active tyrosine residues of both SPO11-1 and SPO11-2 are required for meiotic double-strand break induction in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(10):3090–3099. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick JR, Brad AM, Krisher RL. Chemical manipulation of glucose metabolism in porcine oocytes: effects on nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation in vitro. Reproduction. 2006;131(2):289–298. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper AK, Magee PT, Welch SK, Friedman M, Hall BD. Macromolecule synthesis and breakdown in relation to sporulation and meiosis in yeast. J Bacteriol. 1974;119(2):619–628. doi: 10.1128/JB.119.2.619-628.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Cheng Z, Wang C, Hong Y, Su H, Wang J, Copenhaver GP, Ma H, Wang Y. Formation of interference-sensitive meiotic cross-overs requires sufficient DNA leading-strand elongation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(40):12534–12539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507165112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JY, Copenhaver GP, Ma H, Wang YX. New insights into the role of DNA synthesis in meiotic recombination. Sci Bull. 2016;61(16):1260–1269. doi: 10.1007/s11434-016-1126-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huo Y, Kamal GM, Wang J, Liu H, Zhang G, Hu Z, Anwar F, Du H. 1H NMR-based metabolomics for discrimination of rice from different geographical origins of China. J Cereal Sci. 2017;76:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalitsis P, Zhang T, Marshall KM, Nielsen CF, Hudson DF. Condensin, master organizer of the genome. Chromosome Res. 2017;25(1):61–76. doi: 10.1007/s10577-017-9553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koubova J, Hu YC, Bhattacharyya T, Soh YQ, Gill ME, Goodheart ML, Hogarth CA, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid activates two pathways required for meiosis in mice. PLOS Genet. 2014;10(8):e1004541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar Y, Zhang L, Panigrahi P, Dholakia BB, Dewangan V, Chavan SG, Kunjir SM, Wu X, Li N, Rajmohanan PR, Kadoo NY, Giri AP, Tang H, Gupta VS. Fusarium oxysporum mediates systems metabolic reprogramming of chickpea roots as revealed by a combination of proteomics and metabolomics. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14(7):1589–1603. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusano M, Yang Z, Okazaki Y, Nakabayashi R, Fukushima A, Saito K. Using metabolomic approaches to explore chemical diversity in rice. Mol Plant. 2015;8(1):58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gall G, Colquhoun IJ, Davis AL, Collins GJ, Verhoeyen ME. Metabolite profiling of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) using 1H NMR spectroscopy as a tool to detect potential unintended effects following a genetic modification. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(9):2447–2456. doi: 10.1021/jf0259967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Chen C, Markmann-Mulisch U, Timofejeva L, Schmelzer E, Ma H, Reiss B. The Arabidopsis AtRAD51 gene is dispensable for vegetative development but required for meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10596–10601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404110101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhu S, Shu W, Guo Y, Guan Y, Zeng J, Wang H, Han L, Zhang J, Liu X, Li C, Hou X, Gao M, Ge J, Ren C, Zhang H, Schedl T, Guo X, Chen M, Wang Q (2020) Characterization of Metabolic Patterns in Mouse Oocytes during Meiotic Maturation. Mol Cell 80 (3):525–540 e529. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.09.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lima MR, Felgueiras ML, Graça G, Rodrigues JE, Barros A, Gil AM, Dias AC. NMR metabolomics of esca disease-affected Vitis vinifera cv. Alvarinho leaves J Exp Bot. 2010;61(14):4033–4042. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Du B, Hao F, Lei H, Wan Q, He G, Wang Y, Tang H. Dynamic metabolic responses of brown planthoppers towards susceptible and resistant rice plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2017;15(10):1346–1357. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melamedbessudo C, Levy AA. Deficiency in DNA methylation increases meiotic crossover rates in euchromatic but not in heterochromatic regions in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):5932–5933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120742109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Wang L, Wang J, Zhao X, Cheng J, Yu W, Jin D, Li Q, Gong Z. Methionine adenosyltransferase 4 mediates DNA and histone methylation. Plant Physiol. 2018 doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier R, Mezard C, Jenczewski E, Macaisne N, Grelon M. The molecular biology of meiosis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015;66:297–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze M, Aversano R, Bucher E, Nicolet J, Reinders J, Paszkowski J. Loss of DNA methylation affects the recombination landscape in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(15):5880–5885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120841109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman K, Roitinger E, Yang J, Armstrong S, Mechtler K, Franklin FCH. Analysis of meiotic protein complexes from Arabidopsis and brassica using affinity-based proteomics. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2013;990:215–226. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-333-6_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poisson LM, Munkarah A, Madi H, Datta I, Hensley-Alford S, Tebbe C, Buekers T, Giri S, Rattan R. A metabolomic approach to identifying platinum resistance in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2015;8(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13048-015-0140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popov VN, Eprintsev AT, Fedorin DN, Oiu F, Igamberdiev AU. Role of transamination in the mobilization of respiratory substrates in germinating seeds of castor oil plants. Appl Biochem Micro. 2007;43(3):341–346. doi: 10.1104/pp.44.6.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradillo M, Lopez E, Linacero R, Romero C, Cunado N, Sanchez-Moran E, Santos JL. Together yes, but not coupled: new insights into the roles of RAD51 and DMC1 in plant meiotic recombination. Plant J. 2012;69(6):921–933. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rato L, Alves MG, Socorro S, Duarte AI, Cavaco JE, Oliveira PF. Metabolic regulation is important for spermatogenesis. Nat Rev Urol. 2012;9(6):330–338. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D, Ye P. Characterization of the metabolic requirements in yeast meiosis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Wang T, Peng Y, Xia B, Qu L-J. Distinguishing transgenic from non-transgenic Arabidopsis plants by 1H NMR-based metabolic fingerprinting. J Genet Genomics. 2009;36(10):621–628. doi: 10.1016/s1673-8527(08)60154-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotelo-Silveira M, Chauvin A-L, Marsch-Martínez N, Winkler R, de Folter S. Metabolic fingerprinting of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:365–365. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey NJ, Kuromori T, Azumi Y, Roberts G, Breuer C, Wada T, Maxwell A, Roberts K, Sugimoto-Shirasu K. Arabidopsis SPO11-2 functions with SPO11-1 in meiotic recombination. Plant J. 2006;48(2):206–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stechow L, Ruiz-Aracama A, van de Water B, Peijnenburg A, Danen E, Lommen A (2013) Identification of cisplatin-regulated metabolic pathways in pluripotent stem cells. PLOS One 8 (10):e76476. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sweetlove LJ, Beard KFM, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR, Ratcliffe RG. Not just a circle: flux modes in the plant TCA cycle. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(8):462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torii KU, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Matsuura Y, Yokoyama R, Whittier RF, Komeda Y. The Arabidopsis ERECTA gene encodes a putative receptor protein kinase with extracellular leucine-rich repeats. Plant Cell. 1996;8(4):735. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.4.735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrielynck N. A DNA topoisomerase VI–like complex initiates meiotic recombination. Science. 2016;351(6276):939–943. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T, Letisse F, Peyriga L, Alkim C, Liu Y, Lardenois A, Martin-Yken H, Portais JC, Primig M, Francois J. Developmental stage dependent metabolic regulation during meiotic differentiation in budding yeast. BMC Biol. 2014;12:60. doi: 10.1186/s12915-014-0060-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Copenhaver GP (2018) Meiotic recombination: mixing it up in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69 (1):13.11–13.33. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040431 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Holmes E, Tang H, Lindon JC, Sprenger N, Turini ME, Bergonzelli G, Fay LB, Kochhar S, Nicholson JK. Experimental metabonomic model of dietary variation and stress interactions. J Proteome Res. 2006;5(7):1535–1542. doi: 10.1021/pr0504182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YL, Lawler D, Larson B, Ramadan Z, Kochhar S, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. Metabonomic investigations of aging and caloric restriction in a life-long dog study. J Proteome Res. 2007;6(5):1846–1854. doi: 10.1021/pr060685n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cheng Z, Huang J, Shi Q, Hong Y, Copenhaver GP, Gong Z, Ma H. The DNA replication factor RFC1 is required for interference-sensitive meiotic crossovers in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(11):e1003039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Xiao R, Wang H, Cheng Z, Li W, Zhu G, Wang Y, Ma H. The Arabidopsis RAD51 paralogs RAD51B, RAD51D and XRCC2 play partially redundant roles in somatic DNA repair and gene regulation. New Phytol. 2014;201(1):292–304. doi: 10.1111/nph.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Niu B, Huang J, Wang H, Yang X, Dong A, Makaroff C, Ma H, Wang Y. The PHD finger protein MMD1/DUET ensures the progression of male meiotic chromosome condensation and directly regulates the expression of the condensin gene CAP-D3. Plant Cell. 2016;28(8):1894–1909. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Huang J, Zhang J, Wang H, Han Y, Copenhaver GP, Ma H, Wang Y. The largest subunit of DNA polymerase delta is required for normal formation of meiotic type I crossovers. Plant Physiol. 2019;179(2):446–459. doi: 10.1104/pp.18.00861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J, Harris C, Lewis J, Beale M. Assessment of 1H NMR spectroscopy and multivariate analysis as a technique for metabolite fingerprinting of Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:949–957. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00705-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen W, Li K, Alseekh S, Omranian N, Zhao L, Zhou Y, Xiao Y, Jin M, Yang N, Liu H, Florian A, Li W, Pan Q, Nikoloski Z, Yan J, Fernie AR. Genetic determinants of the network of primary metabolism and their relationships to plant performance in a maize recombinant inbred line population. Plant Cell. 2015;27(7):1839–1856. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widarto HT, Van DME, Lefeber AW, Erkelens C, Kim HK, Choi YH, Verpoorte R. Metabolomic differentiation of Brassica rapa following herbivory by different insect instars using two-dimensional nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Chem Ecol. 2006;32(11):2417–2428. doi: 10.1007/s10886-006-9152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Dai H, Liu H, Wang Y, Tang H. Revealing the metabonomic variation of rosemary extracts using 1H NMR spectroscopy and multivariate data analysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(21):10142–10153. doi: 10.1021/jf8016833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HL, Wang YB, Jiao GZ, Kong DL, Li Q, Li H, Zheng LL, Tan JH. Effects of glucose metabolism during in vitro maturation on cytoplasmic maturation of mouse oocytes. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20764. doi: 10.1038/srep20764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhang HY, Xie CH, Xue HW, Dijkhuis P, Liu CM. EMBRYONIC FACTOR 1 encodes an AMP deaminase and is essential for the zygote to embryo transition in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2005;42(5):743–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Bedford MT. Protein arginine methyltransferases and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(1):37. doi: 10.1038/nrc3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Makaroff CA, Ma H. The Arabidopsis MALE MEIOCYTE DEATH1 gene encodes a PHD-finger protein that is required for male meiosis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(6):1281–1295. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Lu P, Wang Y, Ma H. The transcriptome landscape of Arabidopsis male meiocytes from high-throughput sequencing: the complexity and evolution of the meiotic process. Plant J. 2011;65(4):503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Li X, Chen W, Liu H, Mi L, Ren D, Mo A, Lu P. ATM promotes RAD51-mediated meiotic DSB repair by inter-sister-chromatid recombination in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:839. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.00839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Zhao Y, Yang J, Jiang Y, Lu F, Jia Y, Yang B. Metabolomic analyses of banana during postharvest senescence by 1H-high resolution-NMR. Food Chem. 2017;218:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.09.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang Y, Du Y, Chen S, Tang H. Dynamic metabonomic responses of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) plants to salt stress. J Proteome Res. 2011;10(4):1904–1914. doi: 10.1021/pr101140n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Huang Y, Hu J, Zhou H, Adeleye AS, Keller AA. 1H NMR and GC-MS based metabolomics reveal defense and detoxification mechanism of cucumber plant under nano-Cu stress. Environ Sci Technol. 2016;50(4):2000–2010. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b05011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, Wang S, Huang Z, Zhang S, Liao Q, Zhang C, Lin T, Qin M, Peng M, Yang C. Rewiring of the fruit metabolome in tomato breeding. Cell. 2018;172(1–2):249–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cell. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Not applicable.