Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to examine the long-term efficacy of a short-term acceptance and commitment therapy-based (ACT) group psychotherapy on patients with psychosis in a community mental health center (CMHC).

Methods

A total of 6 group-based ACT sessions were applied to 16 people diagnosed with psychotic disorders who met the inclusion criteria. They were evaluated at the start of, end of, and 6 months after the therapy using the acceptance and action questionnaire, the psychotic symptom rating scales, and the quality-of-life scale.

Results

At the end of the 6 session group therapy and 6-month follow-up, a statistically significant decrease was found in patients’ psychotic symptoms and experiential avoidance as well as a statistically significant increase in their quality of life (P < .001).

Conclusion

According to the results, ACT can be said to be an effective method for managing psychotic symptoms, reducing experiential avoidance, and improving the quality of life in patients diagnosed with psychotic disorders in CMHCs.

Keywords: Acceptance and commitment therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, group psychotherapy, psychotic disorders

MAIN POINTS.

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has been shown to be effective in psychosis.

The results of this study indicated initial findings about the efficacy of ACT in community mental health center (CMHC) in Turkey for short term and 6 month follow-up.

ACT has been found to reduce psychotic symptoms, experiential avoidance and increase quality of life with an acceptable drop rate.

According to these results, ACT can be a successful therapeutic approach, especially in CMHC.

Introduction

Psychotic disorders are associated with self-stigmatization and decreased quality of life in addition to delusions and hallucinations.1 Chronic psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder have been reported to be associated with loss of occupational and social functioning in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5).2 Psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia are one of the causes of the world’s leading mental disabilities.3 It has a lifelong prevalence in the community between 0.5% and 1.6% and is associated with a high rate of disability.4 Psychotic disorders that cause significant disabilities can be considered as a public health problem.5

Targeting not only psychotic symptoms but also increasing the quality of life and social and occupational functioning have been suggested in management of psychosis.6 The addition of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to pharmacotherapy has been shown to increase the effectiveness of treatment. Adding CBT to routine treatment has been found to be more effective at reducing both positive and negative symptoms compared with people who receive pharmacotherapy alone.7 Although antipsychotic drugs are particularly effective at treating psychosis, their effect on cognitive symptoms is controversial, and side effects reduce treatment compliance.6,8 Therefore, pharmacological treatment and mental-social approaches such as psychotherapy being used together have been suggested for treating psychotic disorders.9,10

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a relatively new psychotherapy, includes psychopathology hypotheses and interventions based on contextual behavioral sciences and relational frame theory. ACT treats psychopathology or clinical problems using a model defined as psychological inflexibility and proposes solutions based on the model.11 According to this model, cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance are 2 basic elements of psychological inflexibility.12 Both cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance cause one’s behavioral repertoire to narrow and behaviors that are inconsistent with the long-term goals of the person. These factors play a fundamental role in the emergence of psychopathology. The purpose of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility, which is the opposite of psychological inflexibility, and the skills like recognizing thoughts and feelings without judgment, and acting in accordance with values.11,13

According to ACT, what is important for functionality in psychotic disorders is the relationship individuals have with these symptoms, not the presence of psychotic symptoms.14 By using strategies such as mindfulness, defusion, and acceptance, ACT aims to reduce experiential avoidance related to psychotic symptoms and to increase the quality of life.9,15,16 Various studies have shown the effectiveness of ACT on psychosis. In a meta-analysis of four controlled studies, ACT was found to be effective at reducing negative symptoms and rehospitalization. 15 A review of 11 randomized controlled studies found ACT to be effective against anxiety, depression, and hallucinations in patients with psychosis.9 Short-term group therapy, which includes 2 to 4 sessions of ACT-based group therapies for psychosis, has been found effective both at the end of treatment and during follow-up in 3 studies.15–17

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of ACT-based group psychotherapy, a current practice in psychotherapies, on experiential avoidance levels, delusions, hallucinations, and quality of life in patients with psychosis. The patients were followed up at a community mental health center (CMHC) after 6 months. The hypothesis of our study was that ACT-based short-term group psychotherapy was effective at reducing the experiential avoidance levels, delusions, and hallucinations and increasing the quality of life of patients with chronic psychotic disorders.

Methods

This study was conducted at the Karaman State Hospital CMHC between February 2019 and November 2019. Because no ethics committee existed in Karaman at that time, approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Necmettin Erbakan University Meram School of Medicine (approval #14562952-050/271, dated February 8, 2019). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants, and the study was conducted within the framework of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample

The sample included individuals between the ages of 18 and 65 years, who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. When scanning the files of clients, 120 people were determined to meet the criteria. A total of 20 people who met the inclusion criteria and voluntarily agreed to participate in the study were included in the pre-evaluation interview, of whom 2 refused to participate in the study because they found the therapy program and session durations too long. The remaining 18 people were included in the study in 2 groups; however, 1 person from each group did not complete the therapy program; therefore, the therapy program was completed with 16 people. Of these, 1 had been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder and the rest with schizophrenia. All the patients continued their treatment with effective doses of antipsychotic drugs before and during the study. During the intervention and follow-up sessions, there were no changes made to their drug treatment. The sample’s mean time since being diagnosed was 18.75 (SD = 7.30) years, and the mean number of hospitalizations was 3.06 (SD = 1.73). One of the included patients, took single antipsychotic medication, whereas the others used 2 or more. In addition, 5 took antidepressants and 3 used mood stabilizers.

Data Collection

Inclusion Criteria for the Study

- Being between the ages of 18 and 65 years,

- Agreeing to participate in the study with written informed consent,

- Being able to read and write enough to fill the scales used in the study,

- Meeting DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Exclusion Criteria

- Primary neurological disorder or intellectual disability,

- Presence of cognitive disorders such as dementia and delirium,

- Already using psychoactive substances,

- The presence of a physical disability that prevented from participating in the sessions.

Data Collection Tools

Sociodemographic Form

This is a semi-structured form prepared to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample. The form included questions about the participants’ age, sex, marital status, medical and psychiatric history, and treatment.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-2 (AAQ-2)

The AAQ-2 was developed to measure experiential avoidance based on the psychological inflexibility model. It is composed of a 7-point Likert-type scale. The participants rated how well the statements described them between 1 (never true) and 7 (always true). Higher scores on the scale indicated higher experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility.18 The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Yavuz et al.19

Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS)

PSYRATS was developed by Haddock et al20 for evaluating auditory hallucinations, delusions, and the relationship individuals have with these symptoms. It includes 2 separate scales, one that evaluates delusions and the other that evaluates auditory hallucinations. The semi-structured interview form is scored by the clinician during the interview. The delusions scale (PSYRATS-d) includes 6 items. This scale evaluates the amount and duration of one’s experiences with delusions, belief/doubt, level and intensity of distress, and impairment in functionality resulting from delusions. The auditory hallucinations scale (PSYRATS-h) has 11 items. This scale evaluates frequency, duration, location, loudness, and beliefs about the source of auditory hallucinations as well as the amount and level of their negative content, the amount and intensity of distress, and level of disruption in functionality they cause, and the controllability of auditory hallucinations. All subscale items are scored between 0 and 4, with only the item related to the controllability of auditory hallucinations being reverse scored. Higher scores obtained from the scales indicate greater symptoms. The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Sevi et al.21

The Quality-of-life Scale (QLS) for Schizophrenic Patients

This scale was developed by Heinrich et al.22 The QLS aims to evaluate schizophrenic outpatients’ social adaptability. The scale has 21 items and 4 dimensions, these dimensions being intrapsychic foundations, instrumental role, interpersonal relations, and common objects and activities. This scale is applied using a structured interview. Each item is scored between 0 and 6. Higher scores indicate higher quality of life and better adjustment, whereas lower scores indicate lower quality of life and poor adjustment. The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Soygür et al.23

Application

The groups were planned to include 8–10 people. After evaluating the patients who applied, group therapy sessions were started once the groups reached enough members, and 2 therapy groups were formed. The first group started their group therapy sessions with 10 people and the second group with 8 people. The groups were not determined according to the sociodemographic characteristics or the clinical statuses of the patients. The clients did not change their medication treatment during the therapy program. From the first therapy group, 1 patient was excluded because he had also received individual psychotherapy for his obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and 1 person from the second group left because the group therapy schedule was not appropriate for him.

A total of 6 sessions of ACT-based group therapy was administered by 1 therapist and 3 co-therapists once a week consecutively. Session duration was set between 90 and 120 minutes based on group size. The intervention protocol was created by a therapist experienced in ACT by examining 2 existing protocols.16,24 The therapy protocol created for this study was composed of the following sections: psychoeducation, interventions for cognitive processes, behavioral interventions, and relapse prevention. The practitioner therapist has received theoretical and supervisory training in ACT. The co-therapists are clinical psychologists and nurses experienced with psychosis. Before each session, the therapists and co-therapists held meetings about the planned interventions or the performance of the session, with the therapist informing the co-therapists. The session contents are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Content of the Group Therapy Sessions

| Session 1: Introducing everyone and introducing the participants to the principles of group therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and the psychosis model |

| Session 2: Introducing the concept of values and determining personal values |

| Session 3: Applying defusion and acceptance interventions within the framework of personal values; determining which exercises to perform between sessions |

| Session 4: Applying defusion and acceptance-based interventions within the framework of personal values; determining which exercises to perform between sessions |

| Session 5: Evaluating problems related to interpersonal relations; applying defusion and acceptance interventions; determining which exercises to perform between sessions |

| Session 6: Summarizing and reviewing what has been learned and achieved in previous sessions |

The patients were evaluated with face-to-face interviews with the 4 scales a total of 3 times: once before the first session (t0), once at the end of therapy (t1), and once 6 months after the completion of therapy (t2). The procedures involved from selecting the patients to collecting the final data were completed between March and September 2019.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using the SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The groups’ compliance to normal distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histogram graphics. The Friedman test, which is a nonparametric alternative to the analysis of variance test, was used for one-way ordinal variables to evaluate 3 ordinal variables. In addition, the variables t0, t1, and t2 were evaluated in pairs using the Wilcoxon signed ranks test, a nonparametric alternative to the t-test for ordinal variables25 with P < .05 being considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

The mean age of the patients (n = 16) was 45.75 (SD = 7.24) years. The sample consisted of 14 (87.5%) men and 2 (12.5%) women. A total of 8 patients lived with their spouses and/or children, 4 with their parents, 2 alone, and 2 in a nursing home; 6 were single, 7 married, and 3 widowed/divorced. The average educational level of the sample was 9.25 (SD = 3.56) years. Of the 16 patients, 3 whose data had been evaluated attended 5 sessions, whereas the others attended 6 sessions. The 16 people who completed the program attended an average of 5.81 sessions.

Changes Regarding Scale Scores

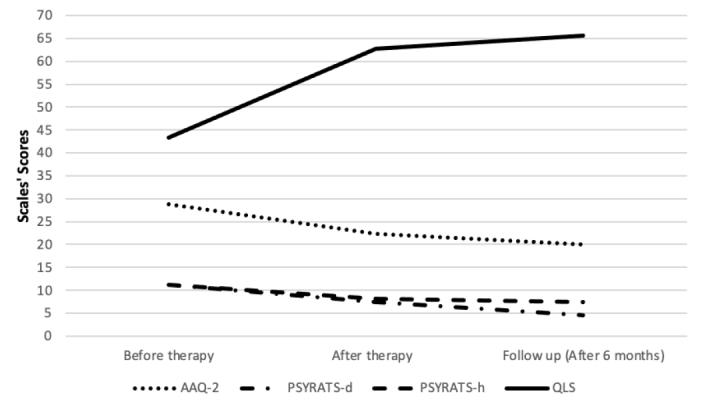

As the number of patients was small (n = 16), the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results and histogram graphics were examined together; and the evaluated scale scores were found to be not normally distributed; therefore, nonparametric tests were chosen. A statistically significant change was found in the scores from the AAQ-2, QLS, PSYRATS delusional and auditory hallucinations subscales, all of which were evaluated 3 times during the therapy/follow-up process using the Friedman test (P < .01). Because auditory hallucinations were initially detected in 7 patients, the changes in scores from the PSYRATS auditory hallucination subscale were only evaluated for these individuals. The significance levels of the descriptive statistics for scale scores regarding ordinal measurements, Friedman tests, and Wilcoxon signed ranks tests are given in Table 2. The changes in scale scores are shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean, SD | 45.75 (7.24) |

| Sex | |

| Men, n (%) | 14 (87.5) |

| Women, n (%) | 2 (12.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Single, n (%) | 6 (37.5) |

| Married, n (%) | 7 (43.75) |

| Widowed or divorced, n (%) | 3 (18.75) |

| Residential status (lives with) | |

| Spouse and/or children | 8 (50.0) |

| Parent(s) | 4 (25.0) |

| Nursing home | 2 (12.5) |

| Alone | 2 (12.5) |

| Education level, years, mean (SD) | 9.25 (3.56) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Schizophrenia, n (%) | 15 (93.75) |

| Schizoaffective disorder, n (%) | 1 (6.25) |

| Years since first diagnosis, years, mean (SD) | 18.75 (7.30) |

| Number of times hospitalized, mean (SD) | 3.06 (1.73) |

| Current treatment | |

| Single antipsychotic, n (%) | 1 (6.25) |

| Two or more antipsychotics, n (%) | 15 (93.75) |

| Antidepressant, n (%) | 5 (31.25) |

| Mood stabilizer, n (%) | 3 (18.75) |

SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Changes in the scales’ scores

AAQ-2, Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; PSYRATS-d, The Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale for Delusions; PSYRATS-h, The Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale for Auditory Hallucinations; QLS, Quality-of-Life Scale.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics for Scale Scores, Mean and Standard Deviation, Significance Levels for Friedman Tests and Wilcoxon Signed Rank Tests

| Face-to-face interview | Before therapy (t0) | End of therapy (t1) | 6-month follow-up (t2) | P (Friedman) | P (Wilcoxon t0–t1) | P (Wilcoxon t1–t2) | P (Wilcoxon t0–t2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAQ-2 (n = 16) | 28.75 (8.52) | 22.25 (8.97) | 20.06 (10.02) | < .001 | .008 | .102 | .001 |

| PSYRATS-d (n = 16) | 11.25 (2.67) | 7.38 (3.83) | 4.62 (4.62) | < .001 | .001 | .004 | < .001 |

| PSYRATS-h (n = 7) | 11.19 (9.09) | 8.12 (8.12) | 7.38 (5.34) | .009 | .108 | .465 | .018 |

| QLS (n = 16) | 43.37 (9.60) | 62.69 (6.38) | 6562 (10.26) | < .001 | < .001 | .165 | < .001 |

| QLS-1 (n = 16) | 16.88 (3.16) | 24.81 (2.536) | 26.69 (3.30) | < .001 | < .001 | .016 | < .001 |

| QLS-2 (n = 16) | 3.19 (2.43) | 5.81 (2.20) | 7.750 (4.60) | < .001 | < .001 | .009 | < .001 |

| QLS-3 (n = 16) | 17.87 (4.06) | 24.87 (2.70) | 23.50 (3.92) | < .001 | < .001 | .049 | .001 |

| QLS-4 (n = 16) | 5.94 (1.84) | 7.19 (1.38) | 7.688 (1.35) | < .001 | < .001 | .054 | .001 |

AAQ-2, Acceptance And Action Questionnaire; PSYRATS-d, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale for Delusions; PSYRATS-h, Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale for Auditory Hallucinations; QLS, Quality-of-Life Scale; QLS-1, being intrapsychic foundations; QLS-2, instrumental role; QLS-3, interpersonal relations; QLS-4, common objects and activities.

P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effectiveness of ACT-based group psychotherapy on chronic psychotic disorders. When analyzing the obtained data and evaluating the intervention and follow-up sessions together, a statistically significant change was found for all the measures. The fact that 16 out of 18 patients completed the therapy program and that those who completed the program attended an average of 5.81 out of the 6 sessions suggested that the protocol could be applied to patients with psychosis. These results can be interpreted as the effectiveness of ACT-based group therapy in the treatment and care of chronic psychosis with the effects lasting at least 6 months.

Our study evaluated the change in the relationship between auditory hallucinations and delusions (which are accepted as positive psychotic findings) and the patients’ relationship with these findings using PSYRATS; and a statistically significant decrease was found in both scale scores over time. According to the obtained results, changes can be interpreted as having occurred in the quality and quantity of auditory hallucinations and delusions in patients (that is, the patients’ auditory hallucinations decrease, and dysfunctional attitudes toward these findings change). The patients’ dysfunctional relationship with psychotic symptoms may be associated with the emergence of avoidance behaviors and decreased functionality. Experiential avoidance and cognitive fusion have been shown to be effective in sustaining and increasing psychotic symptoms.26 ACT primarily aims not to change patients’ psychotic symptoms but their relationships with these behaviors. 16 Although not the primary goal, changes in symptoms occur as a secondary effect.12 Similar to our study, others have shown symptom levels to decrease as a result of ACT interventions.9 The findings resulting from the therapy sessions can be said to be in line with the ACT perspective.

When evaluating the data obtained from the QLS and its subscales, a statistically significant increase was found in the overall functionality and its sub-dimensions through the therapy program. The performed intervention could be hypothesized to have provided improvement in different areas of functionality. In another randomized controlled study, ACT applications were added to the treatment of some patients with schizophrenia, whereas others continued their previous treatment. As a result, decreased symptom-related social functioning was found to occur less in patients who had ACT added to their treatment.18 A total of 2 meta-analyses showed interventions based on acceptance and mindfulness or ACT-based interventions to increase functionality,27,28 and our results were consistent with the literature.

Data have been compared in pairs at 3 measurement points. Between the measurements applied before and after the intervention sessions (t0 to t1), a significant decrease in scores were found for the AAQ-2 and PSYRATS-d and a significant increase in scores for QLS and its subscales. This result was consistent with our hypothesis; thus, ACT therapy could be said to be effective at reducing experiential avoidance and delusions and at increasing the quality of life in psychotic disorders over the short period of approximately 2 months from the beginning to end of the therapy. A similar result was not found for the PSYRATS-h scores. The reason for this situation could be due to only evaluating 7 people with auditory hallucinations. Significant results can be found if the applied protocol is repeated over a larger sample.

When assessing the results between the scales applied at the end of the intervention (t1) and those at the follow-up session (t2) scores from the AAQ-2, PSYRATS-d, and PSYRATS-h were found to have either significantly decreased or not changed. A significant increase or no difference was found for the scores from QLS and its subscales. In summary, some measurements improved, but no measurements regressed. This result can be interpreted as showing the therapy’s effectiveness to continue into the post-therapy period. The literature also contains studies showing the effects of ACT to continue post-therapy. 9,17,19

Our study has found a decrease in experiential avoidance as assessed by the AAQ-2 alongside the therapy. Studies have stated that experiential avoidance is related to both positive symptoms and may be related to functionality in psychotic disorders.26,29,30 The applied group therapy protocol has been found to reduce experiential avoidance, and this has also been demonstrated in other studies.9

The 2 most important limitations of our study were the absence of a control group and the small sample size. Another important limitation was that the follow-up period was limited to 6 months. Longer follow-up periods can provide sturdier information on disorders that become chronic and worsen in clinical processes such as psychotic disorders.

In conclusion, the group ACT sessions applied for short-term psychosis have been found to reduce experiential avoidance and increase the quality of life in patients with psychotic symptoms. The patients’ high attendance rates in the sessions also suggested the applied protocol to be acceptable. We believe that in institutions such as CMHCs where interventions such as psychotherapy come to the fore, a group therapy protocol can make positive changes in the quality of life of the patients with psychotic symptoms and can be applied alongside pharmacotherapy. In future studies, this protocol may be repeated with larger samples and with a control group for further statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Cite this article as: Burhan HŞ, Karadere E. Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for patients with psychosis being monitored at a community mental health center: a six-month follow-up study. Alpha Psychiatry. 2021;22(4):206-211.

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Necmettin Erbakan University Meram School of Medicine (Approval Date: February 8, 2019; Approval Number: #14562952-050/271).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the individuals who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - H.Ş.B.; Design - H.Ş.B.; Supervision - H.Ş.B.; Resources - H.Ş.B.; Materials - H.Ş.B.; Data Collection and/or Processing - H.Ş.B.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - H.Ş.B., E.K.; Literature Search - H.Ş.B., E.K.; Writing - H.Ş.B., E.K.; Critical Review - H.Ş.B., E.K.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Wake S, Roebuck S, Boyden P. The evidence base of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in psychosis: a systematic review. J Context Behav Sci. 2018;10:1–13. 10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013:991. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radua J, Ramella-Cravaro V, Ioannidis JPA, et al. What causes psychosis? An umbrella review of risk and protective factors. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(1):49–66. 10.1002/wps.20490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rössler W, Joachim Salize H, Van Os J, Riecher-Rössler A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):399–409. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knapp M, Mangalore R, Simon J. The global costs of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):279–293. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soygür H, Alptekin K, Atbaşoğlu EC, Herken H, eds. Şizofreni ve Diğer Psikotik Bozukluklar [Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders]. Ankara: Türkiye Psikiyatri Derneği Yayınları; 2007:518. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garety PA, Fowler D, Kuipers E. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant symptoms. Schizophr Bull. 1979;26(1):73–86. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharma T. Cognitive effects of conventional and atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:44–51. 10.1192/S0007125000298103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yıldız E. The effects of acceptance and commitment therapy in psychosis treatment: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2019;56(1):1–19. 10.1111/ppc.12396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haram A, Jonsbu E, Fosse R, Skårderud F, Hole T. Psychotherapy in schizophrenia: a retrospective controlled study. Psychosis. 2018;10(2):110–121. 10.1080/17522439.2018.1460392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yavuz F. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT): an overview. Turkiye Klin J Psychiatry. 2015;8:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayes SC. Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behav Ther. 2016;35(4):639–665. 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80013-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes SC, Pistorello J, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a unified model of behavior change. Couns Psychol. 2012;40:976–1002. 10.1177/0011000012460836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD, Hayes SC. Is it the symptom or the relation to it? Investigating poten-tial mediators of change in acceptance and com-mitment therapy for psychosis. Behav Ther. 2010;41(4):543–554. 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tonarelli SB, Pasillas R, Alvarado L, Dwivedi A, Cancellare A. Acceptance and commitment therapy compared to treatment as usual in psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. African J Psychiatry. 2016;19:1–5. 10.4172/2378-5756.1000366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas N, Shawyer F, Castle DJ, Copolov D, Hayes SC, Farhall J. A randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for psychosis: study protocol. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:198. 10.1186/1471-244X-14-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach P, Hayes SC, Gallop R. Long-term effects of brief acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. Behav Modif. 2012;36(2):165–181. 10.1177/0145445511427193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, et al. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II: a revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behav Ther. 2011;42(4):676–688. 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yavuz F, Ulusoy S, Iskin M, et al. Turkish version of Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II): a reliability and validity analysis in clinical and non-clinical samples. Bulletin Clin Psychopharmacol. 2016;26(4):397–408. 10.5455/bcp.20160223124107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddock G, McCarron J, Tarrier N, Faragher EB. Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: the psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS). Psychol Med. 1999;29(4):879–889. 10.1017/S0033291799008661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sevi OM, Tekinsav Sütcü S, Güneş B. The assessment of the auditory hallucinations and delusions: the reliability and the validity of Turkish version of the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS). Türk Psikiyatri Derg. 2016;27(2):119–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):388–398. 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soygür H, Aybaş M, Hınçal G, Aydemir Ç. Şizofreni hastaları için yaşam niteliği ölçeği: Güvenirlik ve yapısal geçerlik çalışması [Quality of life scale for schizophrenic patients: study of the reliability and construct validity]. Dusunen Adam. 2000;13(4):204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oliver J, Morris E, Johns L, Byrne M. ACT for Life Group Intervention for Psychosis Manual. Institute of Psychiatry; 2011:40. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pallant J. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS. 2nd ed. Allen & Unwin; 2015:318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstone E, Farhall J, Ong B. Life hassles, experiential avoidance and distressing delusional experiences. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49(4):260–266. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaudiano BA, Busch AM, Wenze SJ, Nowlan K, Epstein-Lubow G, Miller IW. Acceptance-based behavior therapy for depression with psychosis: results from a pilot feasibility randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(5):320. 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Louise S, Fitzpatrick M, Strauss C, Rossell SL, Thomas N. Mindfulness-and acceptance-based interventions for psychosis: our current understanding and a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2018;192:57–63. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burhan HŞ, Şafak Y. Relationship of models of consistency and psychological flexibility with persecutory delusions. JCBPR. 2019;8(3):179–189. 10.5455/JCBPR.41475 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cansiz A, Nalbant A, Yavuz KF. Investigation of psychological flexibility in patients with schizophrenia. J Cogn Psychother Res. 2020;9(2):82–93. [Google Scholar]