Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate caregivers of children with urinary incontinence in terms of the caregiving burden and its associated manifestations.

Methods

Caregivers of children who are being treated for urinary incontinence secondary to neurogenic and non-neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) were evaluated for caregiver burden (Zarit score), depression (Beck Depression Inventory [BDI]), and anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory [BAI]). Additionally, children were evaluated for dysfunctional voiding score. All scores were statistically analyzed for correlation with and relation to the caregiver’s emotional status.

Results

Zarit score was equal in caregivers of children with neurogenic and non-neurogenic LUTD. BDI score was higher in caregivers of patients with neurogenic LUTD, whereas BAI score was higher in caregivers of patients with non-neurogenic LUTD. In the evaluation performed, considering the etiological difference, Zarit score in the group with non-neurogenic LUTD correlated positively with BAI and BDI scores. In the neurogenic bladder group, Zarit score correlated with BDI score.

Conclusion

It is important not only in psychiatric patients, but also in those with other chronic disease processes, to evaluate the mental status of caregivers and to support them in dealing with the problem.

Keywords: Caregiver burden, depression, anxiety, urinary incontinence

MAIN POINTS.

It was found that in children with urinary incontinence, the burden experienced or perceived by the caregivers is high.

The burden experienced by the caregivers leads to analogous results in terms of challenging the family, and this burden is accompanied by changes in mood such as depression and anxiety and is affected by these mood changes.

It is important to evaluate the mental status of the caregivers and to provide psychiatric support to them.

Introduction

The term ‘burden’ is used to define the effect of the difficulties, problems, and negative events caused by the disease and treatment process on the daily lives of families and caregivers.1, 2 The additional problems arising from the disease and treatment process may lead to an increased burden for the caregiver when combined with the ongoing and busy daily life of the caregiving parent and other problems arising from work, family, and social life.3, 4

In chronic diseases in adulthood, it has been demonstrated that social isolation because of difficulties arising from the disease increases the burden of the caregiver and negatively affects their mental health.5, 6 Indeed, in studies performed with the caregivers of adult patients, opinions have been expressed that increased caregiving burden in chronic treatment processes may interrupt and complicate the treatment of the individual cared for.5–7

From this experience obtained from adults, it can be argued that the decrease in the functionality of a child with a chronic disease can cause great difficulty for caregivers, which may be reflected in the treatment, hindering the healing process. For example, urinary incontinence related to lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) is a common medical and social problem in pediatric urology practice.8 LUTD is classified into two subgroups: neurogenic and non-neurogenic.8 Neurogenic LUTD is generally secondary to congenital nervous system pathologies, where spina bifida is the most common anomaly.9 These patients experience voiding-related problems from birth onward, which vary depending on the existing neurological sequel. In this group, urinary incontinence can be controlled with treatment, but it may also be lifelong at the same intensity.9 Dysfunctional voiding in the absence of any neuroanatomical abnormality is defined as non-neurogenic LUTD.10–13 The incidence of symptoms decreases gradually with age in non-neurogenic LUTD, with the rate of complete response to behavioral and medical therapy being high. Previous studies reported that depression symptoms can be more commonly observed in patients with neurogenic LUTD and their caregivers compared with the normal population.14–17 In dysfunctional voiding of non-neurogenic LUTD, where it is normally thought that the symptoms will not be permanent, the burden of the caregiver is likely to be lower than for those with dysfunctional voiding of neurogenic bladder origin. Therefore, the data related to the increased burden in the caregivers of the treated children should be important in terms of both the quality of life and mental health of the caregivers and the sufficiency and effectiveness of the support received by children from their caregivers; however, there are no data regarding this in the literature yet.

Another question to be asked at this point is regarding the increase in the burden of caregiver (s) and possibly related mood disorders caused by the etiology of the disease or the loss of function caused by the prolongation of the disease or treatment process. It is thought that the burden of the caregiver is related to the patient’s degree of dependency on the caregiver to maintain the activities of daily life rather than the diagnosis of the disease itself.18

In this study, we evaluated caregivers of children with urinary incontinence for two different etiological reasons in terms of the caregiving burden and its associated manifestations. We focused on the difference of caregiver burden and whether the effect of increased burden changes in children with chronic permanent urinary incontinence (neurogenic LUTD) and treatable urinary incontinence (non-neurogenic LUTD). According to our knowledge, this is the first study that interrogates and compares the psychiatric aspect of caregivers of children with urinary incontinence in terms of etiological difference.

Methods

Participants

The study included caregivers of pediatric patients over five years of age who are being treated for urinary incontinence secondary to neurogenic (n = 60) and non-neurogenic (n = 60) LUTD. In the selection of children diagnosed with neurogenic LUTD whose caregivers were included in the study, the inclusion criteria were absence of any mental disabilities or mobilization problems. All children were mobile either with a wheelchair or spontaneously. In the non-neurogenic LUTD group, the inclusion criteria were diagnosis for at least 1 year and lack of response or response below 50% to treatment with the protocol appropriate for the subgroup of voiding dysfunction.12

Caregivers with pre-diagnosed psychiatric problems were excluded from the study.

Measures

Information related to pediatric dysfunctional voiding was obtained when the children and caregivers were together, whereas the evaluations relating to the caregivers were obtained while ensuring that the caregivers were alone, away from the children.

Sociodemographic Characteristics Data Form

The authors created a questionnaire including information on sociodemographic features of children and caregivers. The form applied to all caregivers and children.

Dysfunctional Voiding and Incontinence Symptom Score (DVSS)

A 14-item DVSS created by Akbal et al19 was applied to all patients to assess the severity of the voiding dysfunction. This scoring system numerically evaluates the complaints relating to urinary incontinence at night, daytime, or both night and daytime. The scale includes questions for additional urinary problems that can be observed in LUTD and also interrogates the life quality of the children. This scoring system was developed in Turkey and the primary language of the symptom score is Turkish. An increased score is associated with an increase in the severity of the voiding dysfunction.19

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

The 21-item BDI was applied to assess the severity of the depression of caregivers.20 The scale was developed by Beck et al,20 and a Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Hisli.21 Possible total scores from the scale range from 0 to 63. Severity of depression increases with increasing scores.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

The 21-item BAI was applied to caregivers to assess the anxiety score of caregivers. The scale was developed by Beck et al,22 and a Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Ulusoy.23

Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale

The 22-item Zarit Caregiver Burden Scale was applied to caregivers to assess the burden of caregiving.7 The scale was developed by Zarit et al,7 and a validity and reliability study was carried out by Özlü et al.24

Ethical Considerations

Ethics committee approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Uludağ University School of Medicine for the study (Approval Date: March 4, 2020; Approval Number: 2020-04/1). Verbal and written consent was received from caregivers who agreed to participate in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 13.0 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). The distribution of the data was examined with the Shapiro-Wilk test. For non-normally distributed data, the Mann-Whitney U test was used for two-group comparisons and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons of more than two groups. The relationships between the variables were examined with the Spearman correlation coefficient. Categorical data were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-square test and Yantes corrected chi-square test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In the sociodemographic evaluation, girls were the majority in the non-neurogenic LUTD group (P = 0.029). The rate of having siblings was low in patients in the neurogenic LUTD group (P = 0.028), and these patients had an extended family structure (P = 0.040). Apart from urinary system disorders, the rate of systemic chronic diseases and DVSS was high in the neurogenic LUTD group. Other demographic characteristics of the patients are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Patients with Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction

| Non-neurogenic (n = 60) | Neurogenic (n = 60) | Total (n = 120) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, [IQR]a, years) | 10 (7–15) | 10 (7–16) | 10 (7–10) | 0.320b |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 43 (57) | 32 (43) | 75 (100) | 0.029c |

| Male | 17 (38) | 28 (62) | 45 (100) | |

| Family, n (%) | ||||

| Nuclear family | 54 (54) | 46 (46) | 100 (100) | 0.040c |

| Extended family | 6 (30) | 14 (70) | 20 (100) | |

| Number of siblings, n (%) | ||||

| Singleton | 10 (33) | 20 (66) | 30 (100) | 0.028c |

| Sibling | 50 (55) | 40 (45) | 90 (100) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 12 (24) | 38 (76) | 50 (100) | |

| Orthopedic | 6 | 23 | 29 | 0.021c |

| Nervous | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Cardiovascular | 6 | 10 | 16 | |

| DVVS | 9 (4–33) | 15 (5–46) | 0.001b |

Abbreviation: DVSS, dysfunctional voiding and incontinence symptom score.

Interquartile range (25–75).

Mann-Whitney U test.

Chi-square test.

The caregiver of patients in the non-neurogenic LUTD group was usually the mother. In the neurogenic LUTD group, the caregiving was equally distributed between parents (P = 0.037). The Zarit caregiver burden score was equal in both patient groups (P = 0.29). The BDI score was higher in the caregivers of patients with neurogenic LUTD (P = 0.031), whereas the BAI score was higher in the caregivers of patients with non-neurogenic LUTD (P = 0.010). Demographic characteristics and BAI, BDI, and Zarit caregiver burden scores of caregivers are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation of Demographic Characteristics and BDI and BAI Scores of Caregivers

| Non-neurogenic (n = 60) | Neurogenic (n = 60) | Total (n = 120) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of the caregiver (median, [IQR]a, year) | 38 (28–49) | 39 (27–56) | 38 (27–56) | 0.170b |

| Caregiver, n (%) | ||||

| Mother | 45 (59) | 31 (41) | 76 (100) | 0.037c |

| Father | 15 (34) | 29 (66) | 44 (100) | |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||||

| Married | 56 (51) | 53 (49) | 109 (100) | 0.260c |

| Single | 4 (36) | 7 (64) | 11 (100) | |

| Educational status, n (%) | ||||

| Elementary school | 18 (50) | 18 (50) | 36 (100) | 0.750d |

| High school | 38 (52) | 35 (48) | 73 (100) | |

| University | 4 (36) | 7 (64) | 11 (100) | |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||

| Employed | 20 (42) | 28 (58) | 48 (100) | 0.130c |

| Unemployed | 40 (56) | 32 (44) | 72 (100) | |

| BAI score (median) | 19 (0–43) | 12 (0–38) | 11 (0–43) | 0.010b |

| BDI score (median) | 12 (0–41) | 18 (0–56) | 13 (0–56) | 0.031b |

| Zarit score (median) | 20 (5–49) | 25 (3–77) | 24 (3–77) | 0.290b |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory.

Interquartile Range (25–75).

Mann-Whitney U test.

Chi-square test.

Kruskal-Wallis test.

When the DVSS scores of the patients and the BDI and BAI scores of the caregivers were evaluated in terms of their correlation with the Zarit caregiver burden scores, independent of the etiology, the increase in the Zarit caregiver burden score correlated positively with the increase in DVSS and the BDI and BAI scores (Table 3). In addition, it was determined that DVSS had a positive correlation with BDI and BAI scores (r = 0.492 and r = 0.372, respectively; P < 0.01).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the Relationship of Caregiver Burden Scores with DVSS, BAI Scores, and BDI Scores Independent of the Etiology

| r | P a | |

|---|---|---|

| DVSS | 0.617 | < 0.001 |

| BAI Score | 0.425 | < 0.001 |

| BDI Score | 0.459 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory, DVSS: dysfunctional voiding and incontinence symptom score.

Spearman’s correlation.

In the evaluation performed considering the etiological difference, the Zarit caregiver burden score in the group with non-neurogenic LUTD correlates positively with the BAI and BDI scores. In the neurogenic bladder group, caregiving burden scores did not correlate with BAI score but did correlate with BDI score. DVSS and caregiving burden scores showed a positive correlation in both groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Evaluation of the Relationship of Caregiving Burden Score with DVSS, BAI, and BDI Scores in the Evaluation Carried out Considering the Etiological Difference

| Lower urinary tract dysfunction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-neurogenic | Neurogenic | |||

| r | P | r | P | |

| Patients | ||||

| DVSS | 0.46 | <0.001a | 0.64 | <0.001a |

| Caregiver | ||||

| BAI | 0.45 | <0.001a | - | 0.142a |

| BDI | 0.36 | <0.001a | 0.40 | <0.001a |

Abbreviations: BAI, Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; DVSS, dysfunctional voiding and incontinence symptom score.

Spearman’s correlation.

Discussion

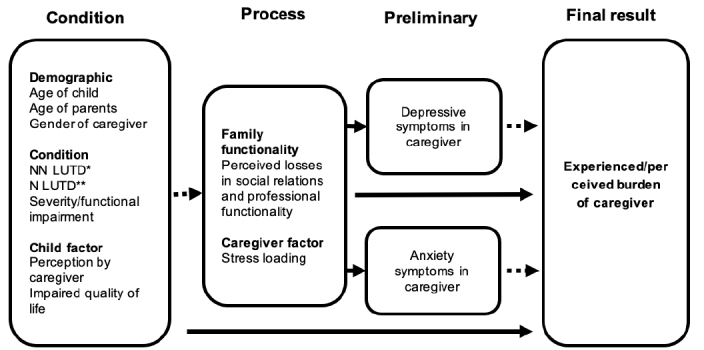

It has been reported in previous studies that those who provide care for an individual who will struggle with a chronic disease throughout their life are negatively affected economically, psychologically, and socially.25 In addition, patients in whom the expected treatment response could not be achieved and patients who acquired the disease in the prenatal period are unlikely to respond to a treatment, which can also increase the burden of the caregiver.26–28 Therefore, we based our hypothesis on the idea that the burden experienced/perceived by the caregiver might be independent of the etiology but rather result from the functional losses in the child, the subsequent stress burden, and the consequences of this stress burden. The considerations on which we based our comparisons are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematization of the Considerations on Which Comparisons Were Based

Abbreviations: NN LUTD, non-neurogenic lower urinary tract disorder; N LUTD: neurogenic lower urinary tract disorder.

Our findings showed that care is shared between mother and father in the neurogenic LUTD group. However, the obligation to provide care in the non-neurogenic LUTD group is largely fulfilled by the mother. This difference, which has not been mentioned in the literature, can be attributed to the fact that the difficulties faced by the patients with neurogenic bladder are known by the mother and father since their birth so that the burden is shared from the very beginning and that the responsibility in the other group always rests on one of the parents because there is always hope for a response to treatment.

Our results indicated that the severity of voiding dysfunction was significantly higher in the neurogenic LUTD group than the other group. Therefore, at first glance, it can be predicted that the burden of the neurogenic LUTD group will be higher, but our data revealed that the burden of the caregivers in both groups is equal. These data support our view that the burden is independent of the etiology and is related to the losses in the functionality of the family and the stress loading potentially created by these losses, as seen in the results from the caregiver burden scale. As a matter of fact, the findings obtained from the studies conducted in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders are in this direction.23, 24

The fact that the increase in caregiver burden is parallel to the increase in DVSS clearly reveals the deterministic nature of the symptom severity and the subsequent outcomes. Moreover, the increase in DVSS is parallel to the increase in depression and anxiety symptoms in both groups. However, our data showed that the increase in depression symptoms was higher in the neurogenic LUTD group compared with anxiety symptoms, whereas the increase in anxiety symptoms was more pronounced in the non-neurogenic LUTD group. This difference may be attributed to the fact that depression is mostly related to losses, whereas anxiety is related to future concerns. Although a child with neurogenic LUTD indicates certain losses for the family from birth, the lack of results despite the hope of response to treatment in patients with non-neurogenic LUTD brings along future concerns.

According to our findings, it was also detected that the increase in the depression score measured with BDI was parallel with the increase in the caregiver burden measured with Zarit et al.7 These data are consistent with the literature findings that depression increases the caregiver burden.29 In addition, the same parallelism applies to the increased BAI score in the non-neurogenic LUTD group. Considering the relationships between depression and anxiety, the importance of investigating anxiety symptoms, which have not been emphasized much in the literature, becomes evident in this group.30 The mood change, which is in line with the caregiver burden in the neurogenic bladder group, is likely to be depression.

In addition, the finding that increased DVSS is parallel to both the depression and anxiety scores and the weight of the caregiver burden suggests that this objective test may be predictive of the degree of the caregiver burden and the possibility of mood impairment in the caregiver. Therefore, it may be the subject of future studies whether this test performed at the first examination of the child can be used as a screening test for caregivers.

This study has several limitations. One of these limitations is the single-center design of the study and families’ homogeneous sociodemographic characteristics. These families are mostly married and have a similar socioeconomic status. Therefore, it has not been possible to evaluate the effects of social and economic factors on caregiving burden, depression, and anxiety. The second important point is that, although the caregiving burdens are found to be equal, additional anomalies of the patients in the neurogenic LUTD group may also affect the depression and anxiety scores. To reduce the effect of these limitations, patients who could be mobilized despite their orthopedic problems in the neurogenic LUTD group were included in the study.

Despite all of these limitations, this is the first time it is emphasized in the literature that the burden of care in patients with non-neurogenic LUTD and the symptoms of depression and anxiety caused by this burden in caregivers are similar to those of patients with neurogenic LUTD. In addition, the determination that increased DVSS in children correlates with an increased burden of care, increased depression, and increased anxiety findings, is important in terms of predicting the problems that caregivers may encounter during the evaluation of children with urinary incontinence. Additionally, all caregivers in whom we detected an increased score of depression and anxiety were directed to specific treatment of these disorders. In further study, we are planning to evaluate the urinary incontinence treatment response of the children after their caregivers complete the specific treatment to assess the effect of mood changes of caregivers on children’s primary disease.

In conclusion, although etiologically different, in both disease groups, the burden experienced or perceived by the caregivers is similar, which leads to analogous results in terms of challenging the family, and this burden is accompanied by changes in mood such as depression and anxiety and is affected by these mood changes. Additionally, the burden of caregivers is similar to caregivers of patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Considering that the rate of depression and anxiety symptoms are higher in the caregivers of individuals with chronic diseases, as also revealed in our study, it can be considered that these issues should be evaluated independently from the etiology and rather in terms of perceived burden. Therefore, it can be concluded that it is important not only in psychiatric patients, but also in other chronic disease processes, to evaluate the mental status of the caregivers and to provide psychiatric support to them in dealing with the problem.

Footnotes

Cite this article as: Altınay Kırlı E, Türk Ş, Kırlı S. The Burden of Urinary Incontinence on Caregivers and Evaluation of Its Impact on Their Emotional Status. Alpha Psychiatry 2021;22(1):43-48.

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Ethics Committee of Uludağ University School of Medicine (Approval Date: March 4, 2020; Approval Number: 2020-04/1).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the individuals who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - S.K.; Design - S.K.; Supervision - S.K.; Materials - E.A.K., Ş.T.; Data Collection and/or Processing - E.A.K.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - E.A.K.; Literature Search - Ş.T.; Writing - E.A.K.; Critical Review - S.K.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Dillehay R, Sandys M. Caregivers for Alzheimer’s patients: what we are learning from research. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1990;30(4):263–85. 10.2190/2P3J-A9AH-HHF4-00RG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winefield HR, Harvey EJ. Needs of family care-givers in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20(3):557–566. 10.1093/schbul/20.3.557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver JH, Wellman N. Family caregiver training is needed to improve outcomes for older adults using homecare technologies. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2002;102(6):831–836. 10.1016/S0002-8223(02)90185-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caqueo-Urízar A, Gutiérrez-Maldonado J. Burden of care in families of patients with schizophrenia. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(4):719–724. 10.1007/s11136-005-4629-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perlick DA Rosenheck RR Clarkin JF, et al. Impact of family burden and patient symptom status on clinical outcome in bipolar affective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(1):31–37. 10.1097/00005053-200101000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McPherson HM Dore GM Loan PA, et al. Socioeconomic characteristics of a Dunedin sample of bipolar patients. N Z Med J. 1992;105(933):161–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of the impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6)649–655. 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayan S Topsakal K Gokce G, et al. Efficacy of combined anticholinergic treatment and behavioral modification as a first line treatment for nonneurogenic and non anatomical voiding dysfunction in children: a randomized controlled trial. J Urol. 2007;177(6):2325–2328. 10.1016/j.juro.2007.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein R Bogaert G Doğan HS, et al. EAU/ESPU Guideline on the management of neurogenic bladder in children and adolescent part I diagnostic and conservative treatment. Neurourol Urodynam 2020;39(1):45–57. 10.1002/nau.24248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kakizaki H Kita M Watanobe M, et al. Pathophysiological and therapetic considerations for non-neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction in children. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2016;8(2):75–85. 10.1111/luts.12123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin PF Bauer SB Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. Neurourol Urodynam. 2016;35(4):471–481. 10.1002/nau.22751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chase J Austin P Hoebeke P, et al. The management of dysfunctional voiding in children: a report from the Standardisation Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2010;183(4):1296–1302. 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoebeke P Renson C Petillon L, et al. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with therapy resistant non-neuropathic bladder sphincter dysfunction: a pilot study. J Urol. 2002;168(6):2605–2607. 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64227-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell LE Adzick NS Melchionne J, et al. Spina bifida. Lancet. 2004;364 (9448):1885–1895. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17445-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ulus Y Tander B Akyol Y, et al. Functional disability of children with spina bifida: its impact on parents’ psychological status and family functioning. Dev Neurorehabil. 2012;15(5):322–328. 10.3109/17518423.2012.691119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brei TJ Woodrome SE Fastenau PS, et al. Depressive symptoms in parents of adolescents with myelomeningocele: the association of clinical, adolescent neuropsychological functioning, and family protective factors. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2014;7(4):341–352. 10.3233/PRM-140303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicoliais C Perrin PB Panyavin I, et al. Family dynamics and psychosocial functioning in children with SCI/D from Colombia, South America. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(1):58–66. 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasui C Sakamoto S Sugiura T, et al. Burden of family members of the mentally ill: a naturalistic study in Japan. Compr Psychiatry. 2002;43(3):219–222. 10.1053/comp.2002.32360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akbal C Genc Y Burgu B, et al. Dysfunctional voiding and incontinence scoring system: quantitative evaluation of incontinence symptoms in pediatric population. J Urol. 2005;173(3):969–973. 10.1097/01.ju.0000152183.91888.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT Rush AJ Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. Guildford Press; 1997;229–256. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hisli N. Beck Depresyon envanterinin geçerliliği üzerine bir çalışma. Psikoloji Dergisi. 1988;6:118–122. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT Epstein N Brown G, et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety psychometric properties. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1998;56(6):893–897. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ulusoy M. Beck Anksiyete Envanteri: Geçerlilik ve Güvenilirlilik Çalışması. Dissertation. Bakırköy Psychiatric Hospital; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Özlü A. Şizofreni Hastalarında Bakım Verenlerde Yük ve Yükün Travma Sonrası Gelişimi ile İlgili Özellikler. Master Thesis. Kocaeli University; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Özaras N. Spina bifida and rehabilitation. Turk J Ph Med Rehab. 2015;61:65–69. 10.5152/tftrd.2015.98250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hancı N Sarandöl A Eker S, et al. İki uçlu bozukluk-I ve şizofreni hastalarının bakım veren yük düzeylerinin karşılaştırılması. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2018;19(5):451–458. 10.5455/apd.290636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydın A Eker S Cangür Ş, et al. The association of the level of caregiver burden with the sociodemographic variable and the characteristic of the disorder in schizophrenic patients. NöroPsikiyatri Arşivi. 2009;46:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coşkun ÖK Atabay CE Şekeroğlu A, et al. The relation between caregiver burden and resilience and quality of life in a Turkish Pediatric Rehabilitation Facility. J Pediatr Nurs. 2019;29:E108–E113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridosh MM Sawin KJ Schiffman RF, et al. Factors associated with parent depressive symptoms and family quality of life in parents of adolescents and young adults with and without spina bifida. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2016;9(4):287–302. 10.3233/PRM-160399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kabra AT, Feustrel PJ, Kogan BA. Screening of depression and anxiety in childhood neurogenic bladder. J Pediatr Urol. 2015;11(2):75e1–75e7. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]