Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to test the mediation effect of narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and self-compassion in the relationship between attachment dimensions and psychopathology.

Methods

The sample included 203 students, of whom 134 (66%) were women and 69 (34%) men with ages between 18 and 36 years [(mean: 20.73 (SD = 2.86)]. In this study, inventory of experiences in close relationships, Beck depression scale, Beck anxiety scale, narcissistic personality inventory, vulnerable narcissism scale, and self-compassion scale were used.

Results

Anxious attachment was positively correlated with vulnerable narcissism and narcissistic personality traits, negatively with self-compassion, and positively with depression and anxiety. However, avoidant attachment was negatively correlated with vulnerable narcissism and narcissistic personality traits. Self-compassion was negatively associated with vulnerable narcissism, depression, and anxiety. When mediating effects were tested, it was found that narcissistic personality traits and vulnerable narcissism had mediating effects both in the relationship between anxious attachment and anxiety and in the relationship between anxious attachment and depression.

Conclusion

As it is known that insecure attachment is associated with the development of many psychopathologies in terms of preventive mental health, it is thought that it will be important to consider the dimensions of self-compassion and narcissism in the prevention programs to be carried out. Considering the mediating effect of self-compassion, targeting the development of an individual’s non-judgmental attitude toward himself or herself can prevent possible psychological problems and create a buffering effect.

Keywords: Parenting, narcissism, depression, anxiety, compassion

MAIN POINTS.

Anxious attachment is positively related to the symptoms of depression and anxiety and it is negatively related to self-compassion.

Avoidant attachment dimension is negatively related to vulnerable narcissism.

Self-compassion appears to have a predictive effect on depression, anxiety, and vulnerable narcissism.

As it is known that insecure attachment is associated with the development of many psychopathologies in terms of protective mental health, it is thought that it will be important to consider the dimensions of self-compassion and narcissism in prevention programs.

Given the mediating effect of self-compassion, targeting the development of non-judgmental attitudes toward oneself can prevent possible psychological distress and create a buffering effect.

Introduction

Bartholomew proposed a 2-dimensional model of adult attachment,1 according to which 4 types of attachment styles can be established: Secure (positive self and positive others), dismissive (positive self and negative others), preoccupied (negative self and positive others), and fearful (negative self and negative others). To integrate these different approaches, Brennan et al.2 conducted exploratory data analysis with 323 items used in the previous attachment style scales. The results supported the 2-dimensional attachment model. Accordingly, all attachment items were grouped under the anxious and avoidant dimensions. Brennan et al2 also examined earlier adult attachment theories and concluded that anxious and avoidant attachment are two basic dimensions in most attachment models.

Mikulincer and Shaver3 reviewed studies in both clinical and non-clinical samples and found that insecure attachment was associated with many different mental disorders in individuals, from mild distress to severe personality disorders and even schizophrenia.

Some researchers argue that secure attachment develops with the affirmation of the child’s emotions and forms the basis of emotion regulation in adulthood.4 The mother’s response when the baby is distressed is highly predictive for secure attachment and has been associated with less behavioral problems, low reactivity levels, and better emotion regulation.4,5

Insecure attachment can therefore be seen as a general predisposition to mental disorders, with certain symptomatology depending on genetic, developmental, and environmental factors. However, attachment styles alone are not considered sufficient to explain psychopathology.6

Narcissism and Vulnerable Narcissism

Crawford et al7 found that attachment anxiety is associated with “emotional disorder,” which is a component of personality disorders, including anxiety, identity confusion, cognitive distortions, self-harm, and narcissism.

Attachment studies associated lack of warmth and need from parents in childhood with self-related disorders, including lack of self-adaptation, doubts about internal consistency, unstable self-esteem, and an excessive need for approval from others.8 The individual’s negative self-beliefs increases the risk of development of mental disorders. Childhood experiences are among the factors leading to the development of narcissism in the personality and self-concept literature. The structure of narcissism has emerged with psychodynamic theories and is a personality trait most often defined as grandiose and vulnerable narcissism.9

Self-compassion

Another variable that is thought to have a mediating effect on the relationship between attachment dimensions and psychopathology is self-compassion. Neff10 defined self-compassion as “being open to and acting on one’s own suffering, nurturing compassion toward oneself, having an understanding, showing a non-judgmental attitude toward one’s inadequacies and failures.” Some researchers have stated that the origins of self-compassion are influenced by early relationships with primary caregivers.11 Individuals with high attachment anxiety often have a negative view of themselves and have difficulty regulating their emotions.12 Neff and McGeehee13 found that secure attachment was associated with higher self-compassion, but attachment dimensions with high attachment anxiety were associated with lower self-understanding. Similarly, Raque-Bogdan et al14 found a relationship between attachment anxiety and lower self-compassion.

Neff15 argued that sensitive parenting helps a person to feel compassion and understanding for herself in stressful moments and to develop self-soothing strategies to relieve distress. Therefore, self-compassion has been associated with lower psychopathology and higher psychological well-being.16

Considering the current findings, this study aimed to test the mediating role of 2 sub-dimensions, narcissism and vulnerable narcissism, and self-compassion in the relationship between attachment dimensions (avoidant/anxious) and psychopathology (depression/anxiety).

Methods

Study Model

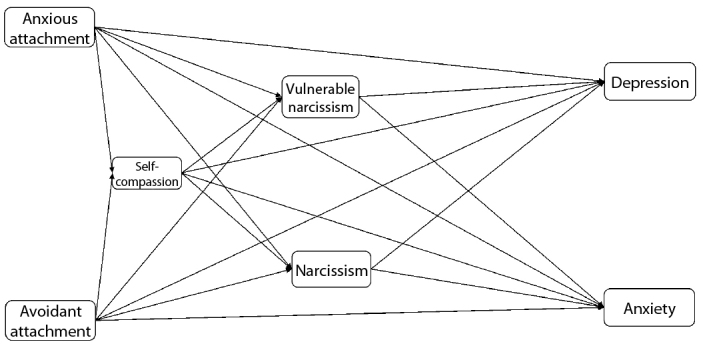

This study was designed according to the relational scanning model to reveal the relationships between attachment dimensions, self-compassion, vulnerable narcissism, narcissism, anxiety, and depression (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothetical Model

Participants

The lower limit for the sample size of the study was calculated as 129 with the G * Power 3.1.9.2 package program (Heinrich Heine University; Dusseldorf, Germany) (f2 = 0.15, α = .05, number of predictor variables = 4). The study group included 203 university students studying in various faculties and departments in the fall semester of the academic year 2018–2019 at Namık Kemal University. Of them, 134 (66%) of the individuals in the study group were women and 69 (34%) men, and their ages were between 18 and 36 [(mean: 20.73 (SD = 2.86)] years. All the participants signed an informed consent form before participating. Ethics committee approval of the study was obtained from Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee on May 20, 2019 (Approval Number: #T2019-6).

Data Collection Tools

Beck Depression Scale

The scale developed by Beck et al17 evaluates somatic, emotional, cognitive, and motivational symptoms seen in depression. The scale includes 21 symptoms. Each item in the scale is scored between 0 and 3. The lowest score that can be obtained from the scale is 0, and the highest score is 63. A high total score indicates a high level of depression. The scale was adapted to Turkish by Tegin.18 The split-half test reliability coefficient of the Turkish scale was 0.78 for the student group and 0.61 for depressive patients.18 The test-retest reliability coefficient of the scale was 0.65. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale for this research sample was calculated as 0.90.

Beck Anxiety Scale

It was developed by Beck et al19 to evaluate the frequency of anxiety. Turkish adaptation studies of the scale were conducted by Ulusoy et al.20 The scale, evaluated by 4-point grading, includes 21 items and indicates that higher the score a person gets, higher the anxiety level. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale for this research sample was calculated as 0.94.20

Narcissistic Personality Inventory

The scale developed by Ames et al21 has 16 items and 7 sub-dimensions: Exhibitionism, exploitativeness, entitlement, self-sufficiency, vanity, and authority. The scores obtained from the scale are between 0 and 16. Atay22 conducted the Turkish adaptation study of the scale. High scores indicate a high narcissistic tendency. The internal reliability value of this scale was stated as 0.65.22 The internal consistency coefficient of the scale calculated in this study was 0.63.

Experiences in Close Relationships Inventory-II (ECR-II)

In the scale developed by Fraley et al,23 there are a total of 36 items in 7-point Likert type, 18 of which are in anxiety sub-factor and 18 of them in avoidance sub-factor. Scores from each sub-dimension were between 18 and 126, and it was stated that as the score obtained from the scale increased, avoidant attachment or attachment anxiety increased. The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Sümer et al.24 The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the avoidance sub-dimension was 0.90, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the anxiety sub-dimension was 0.86. Test-retest reliability coefficients of the scale regarding avoidance and anxiety dimensions are 0.81 and 0.82, respectively. In this study, the internal consistency coefficient for the anxiety sub-dimension of the attachment styles scale was 0.88, 0.78 for the avoidance sub-dimension and 0.84 for the overall scale.

Self-Compassion Scale

Neff10 developed the self-compassion scale. In the original scale prepared to measure the characteristics of the self-compassion structure, respondents were asked to rate them on a 5-point Likert-type scale regarding a specified situation. A high total score means that the level of self-compassion is high. The 26-item self-understanding scale consists of 6 subscales: Self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, consciousness, and over-identification. The Turkish validity and reliability studies of the scale were conducted by Deniz et al.25 The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient calculated on the basis of item analysis for the reliability of the scale is 0.89; the internal consistency coefficient was calculated as 0.89, and the test-retest correlation coefficient as 0.83. However, criterion-related validity of the self-compassion scale was found to be r = 0.62 between SCS and RSES, r = 0.45 between SWLS, r = 0.41 between positive emotion, and r = −0.48 between negative emotion. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale for this research sample was calculated as 0.89.

Vulnerable Narcissism Scale

The scale developed by Hendin and Cheek26 is used to measure the vulnerable and grandiose dimension of narcissism. The original scale consists of 10 items. Participants were asked to rate each item between 1 and 5 according to its power to describe their own feelings and behaviors on the basis of self-reports. High scores indicated an increased level of vulnerable narcissism. Turkish standardization studies of the scale were conducted by Sengul et al.27 The Turkish form of the scale consisted of 8 items. The internal consistency coefficient of the scale for this study sample was calculated as 0.62.

Statistical Analysis

It was observed that the data collection kit prepared for data collection took 10–15 minutes to respond. The hypothetical model in the study was tested with the SPSS 24.0 version (IBM Corp.; Armonk, NY, USA). The compatibility of the model with the data was evaluated by looking at the t values of the path coefficients to the latent variables. In the preliminary analyzes, it was determined that kurtosis values of the variables were between 0.09 and 1.54, and the skewness values were within acceptable limits between 0.11 and 1.08.

Path Analysis

Path analysis, which is accepted as one of the structural equation modeling techniques today, is a data analysis technique introduced by geneticist Wright as a result of a series of empirical studies in the 1920s.28

In this study, the mediating effects of some potential mediator variables in the relationship between dependent and independent variables were tested. The “bootstrap” method proposed by Shrout and Bolger29 was used to reveal a supportive data on the significance of indirect effects and to evaluate the significance level of indirect effects.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

The mean and standard deviation values of the variables included in the model determined within the scope of the research and the correlations between variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations Among Variables, Mean and Standard Deviation Scores

| Variables | Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECR II anxious attachment sub-dimension | 64.40 (18.92) | - | |||||

| ECR II avoidant attachment sub-dimension | 63.13 (15.37) | 0.13 | - | ||||

| Total score of narcissistic personality inventory | 5.51 (2.85) | 0.09 | −0.21a | - | |||

| Total score of self-compassion scale | 74.92 (16.44) | −0.32a | −0.12 | 0.04 | - | ||

| Total score of vulnerable narcissism scale | 23.25 (5.13) | 0.36a | −0.09 | 0.22a | −0.31a | - | |

| Total score of Beck depression scale | 37.39 (11.18) | 0.35a | 0.11 | 0.09 | −0.48a | 0.22a | - |

| Total score of Beck anxiety scale | (38.05 13.96) | 0.32a | 0.16b | −0.02 | −0.33a | 0.17b | 0.57a |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; ECR, experiences in close relationship.

P < .01.

P < .05.

According to the results of Pearson correlation analysis, the lowest correlation coefficient was found between narcissistic personality traits and Beck anxiety score (r = 0.02, P = .806), the highest correlation coefficient was found between Beck anxiety score and Beck depression score (r = 0.57, P = .000).

Path Analysis

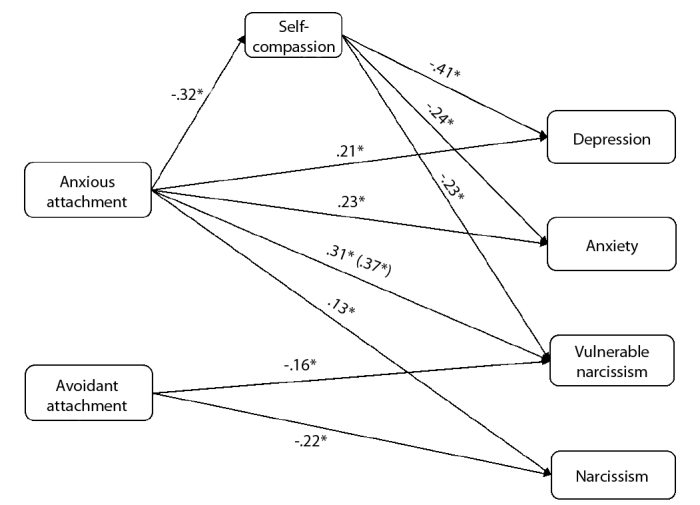

After testing the hypothetical model to be tested within the scope of the research, standardized path coefficients related to the model are given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Standardized Path Coefficients for the Hypothetical Model *P < .05. The value in parentheses reflects the state when other variables have no effect.

When the standardized path coefficients in the model were examined, anxious attachment had a statistically significant predictive effect on vulnerable narcissism (β = .31, P = .00), narcissistic personality traits (β = .13, P = .011), self-compassion (β = −.32, P = .00), depression (β = .21, P = .001), and anxiety (β = .23, P = .002). Avoidant attachment had a statistically significant predictive effect on vulnerable narcissism (β = −.16, P = 0.011) and narcissistic personality traits (β = −.22, P = .001), and self-compassion had a statistically significant predictive effect on fragile narcissism (β = −.23, P = .000), depression (β = −0.41, P = .000), and anxiety (β = −.24, P = .000).

In addition, it was observed that the path coefficient from anxious attachment to vulnerable narcissism was not affected by other variables (β = .37, P = .000), but remained statistically significant when the effects of other variables were considered (β = .32, P = .000). It can be stated that self-compassion has a partial mediating effect on the relationship between narcissism and anxious attachment.

When the variances explained in the model were evaluated, it was determined that anxious attachment, self-understanding, and avoidant attachment together explained 20% of vulnerable narcissism; anxious attachment, self-compassion, and avoidant attachment together explained 6% of narcissistic personality traits; anxious attachment, self-compassion, avoidant attachment, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality traits together explained 29% of depression and anxious attachment, self-compassion, avoidant attachment, vulnerable narcissism, and narcissistic personality traits together explained 18% of anxiety.

Testing the Mediation Effect

In this study, the significance levels of indirect effects were also tested with the bootstrapping method. The criterion for the significance of the indirect effect was that the estimation intervals for the indirect effect did not contain 0. If the indirect effect range did not include 0, the indirect effects were statistically significant; if it did, it was not statistically significant.30 The findings are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bootstrap Test Resultsa

| Path | Mediator(s) | Path coefficient (β) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxious attachment/ vulnerable narcissism | Self-compassion | 0.31b (0.37b) | [0.031, 0.145] |

| Anxious attachment/ anxiety | Self-compassion, narcissism, & vulnerable narcissism | 0.23b (0.32b) | [0.009, 0.175] |

| Anxious attachment/ depression | Self-compassion, narcissism, & vulnerable narcissism | 0.21b (0.34b) | [0.064, 0.233] |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

β = Standardized.

Only indirect effects determined to be statistically significant are reported. Bootstrap was made over 1,000 samples (Hayes, 2009).

P < .05. The value in parentheses reflects the state when other variables have no effect.

As a result of mediation tests, self-compassion in the relationship between anxious attachment and vulnerable narcissism; self-compassion, narcissistic personality traits, and vulnerable narcissism in the relationship between anxious attachment and anxiety, self-compassion, narcissistic personality traits, and vulnerable narcissism were found to have mediating effects.

Discussion

This study aimed to test the mediating role of narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and self-compassion in the relationship between attachment dimensions and psychopathology. In this study, attachment dimensions were evaluated in 2 sub-dimensions as anxious and avoidant, and among psychopathological conditions, depression and anxiety were examined.

Consistent with the literature, the results showed that as the anxious attachment increased, the symptoms of depression and anxiety increased as well.31,32 One possible explanation is that children whose needs are not regularly met during infancy may have a reduced sense of trust in others and may experience anxiety and depression as a result of their inability to develop emotion regulation strategies.33 The results of the study showed that when anxious attachment increased, vulnerable narcissism also increased. In previous studies, similar results regarding anxious attachment among attachment dimensions and narcissism have been observed.34 Anxiously attached individuals are known to be hypersensitive to attachment figures and possible threats.6

It is understandable that individuals who are concerned that they will not get a sensitive response from others when they need it, show hypersensitivity and exaggerated perception. Contrary to what might be expected, anxious attachment is also positively associated with the narcissistic traits scale, which measures the grandiose characteristics of narcissism, but the strength of this relationship is lower than with vulnerable narcissism. This low relationship found suggests that features such as claiming rights and authority can be used as a defense mechanism against anxiety.

Another finding related to anxious attachment is that it is negatively related to self-compassion. Individuals with anxious attachment try to maintain intimacy with the attachment figure and tend to exaggerate the feeling of negativity when they fail, and thus believe that they are inadequete.3 This may lead to a lower level of self-compassion. Similarly, Wei et al35 have found a relationship between attachment anxiety and lower self-compassion. Another result of the study was that self-compassion had a partial mediating effect on the relationship between anxious attachment and vulnerable narcissism. This may indicate that the low self-compassion of an anxiously attached individual may lead to a lack of kindness toward themselves and as a result of this, feeding into vulnerable narcissism dominated by the belief of inadequacy.

Considering the characteristics of the avoidant attachment dimension, such as fear of establishing intimacy and avoidance of attachment, it is an expected result that this attachment dimension where individuality is at the forefront is negatively related to vulnerable narcissism in which there are negative views about themselves.36 A relationship between avoidant attachment, anxiety, and depression was not found. A possible explanation for this may be that they are reluctant to seek help from others and tend to show themselves better because they doubt the interest of others when they need it. As individuals tend to blame themselves more in anxious attachment, it is possible to see the relationship with psychological symptoms more clearly.

Self-compassion appears to have a predictive effect on depression, anxiety, and vulnerable narcissism. As self-compassion increases, vulnerable narcissism, depression and anxiety decrease. One possible explanation for the negative correlation of self-compassion with anxiety and depression is the view that self-compassion has an effect on developing functional strategies to relieve distress and can be a protective factor against psychological symptoms by increasing emotional flexibility.20 The result that self-compassion mediates the relationship between anxious attachment and depression, which is another finding of the study, is consistent with the present findings.

Some limitations should be considered when evaluating the results of this study. The study was conducted only with university students, so it cannot be generalized to a larger population. Future research should evaluate variables associated with attachment and psychopathology in a variety of samples, with a wider age range and cultural diversity. In addition, the cross-sectional design and correlation analysis of the study do not provide information about causality. Self-report scales were used to evaluate variables in the study. There are discussions about the reliability of attachment scales in the literature.37 It is thought that it will be important for future studies to use evaluation tools such as clinical interviews.

As it is known that insecure attachment is associated with the development of many psychopathologies in terms of protective mental health, it is thought that it will be important to consider the dimensions of self-compassion and narcissism in prevention programs. Given the mediating effect of self-compassion, targeting the development of non-judgmental attitudes toward oneself can prevent possible psychological distress and create a buffering effect.38

Footnotes

Cite this article as: Set Z. Mediating role of narcissism, vulnerable narcissism, and self-compassion in the relationship between attachment dimensions and psychopathology. Alpha Psychiatry. 2021;22(3):147-152.

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee of Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University (Approval Date: May 20, 2019; Approval Number: T2019-6).

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the individuals who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Conflict of Interest: The author has no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The author declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.Bartholomew K. Avoidance of intimacy: an attachment perspective. J Soc Pers Relat. 1990;7(2):147–178. 10.1177/0265407590072001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report Measurement of Adult Attachment: An Integrative Overview. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998:46–76. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(1):11–15. 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schore AN. Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self: the Neurobiology of Emotional Development. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2016:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leerkes EM, Blankson AN, O’Brien M. Differential effects of maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress on social-emotional functioning. Child Dev. 2009;80(3):762–75. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01296.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment in Adulthood: Structure, Dynamics, and Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007:3–116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crawford TN, John LW, Jang KL, Shaver PR, Cohen P, Ganiban J. Insecure attachment and personality disorder: a twin study of adults. Eur J Pers. 2007;21(2):191–208. 10.1002/per.602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park LE, Crocker J, Mickelson KD. Attachment styles and contingencies of self-worth. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30(10):1243–1254. 10.1177/0146167204264000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan KA, Shaver PR. Attachment styles and personality disorders: their connections to each other and to parental divorce, parental death, and perceptions of parental caregiving. J Pers. 1998;66(5):835–878. 10.1111/1467-6494.00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity. 2003;2(3):223–250. 10.1080/15298860309027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilbert P. The Compassionate Mind. London: Constable; 2009:79–123. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 2003;35:53–152. 10.1016/S0065-2601(03)01002-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neff KD, McGehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self and Identity. 2010;9(3):225–240. 10.1080/15298860902979307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raque-Bogdan TL, Ericson SK, Jackson J, Martin HM, Bryan NA. Attachment and mental and physical health: self-compassion and mattering as mediators. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(2):272. 10.1037/a0023041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neff KD. Self-Compassion. New York, NY: William Morrow; 2011:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):545–552. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beck AT, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. Beck depression inventory (BDI). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4(6):561–571. 10.1001/archpsyc.1964.01720240015003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tegin B. Depresyonda Bilişsel Bozukluklar: Beck Modeline Göre Bir İnceleme [Cognitive Dysfunctions in Depression: An Analysis Based on Beck Model]. Dissertation. Hacettepe University; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulusoy M, Sahin NH, Erkmen H. The Beck anxiety inventory: psychometric properties. J Cogn Psychother. 1998;12(2):163–172. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ames DR, Rose P, Anderson CP. The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. J Res Pers. 2006;40(4):440–450. 10.1016/j.jrp.2005.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atay S. The standardization of narcissistic personality inventory into Turkish. Gazi Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi. 2009;11(1):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(2):350. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sümer N, Selçuk E, Günaydın G, Uysal A. A new scale developed to measure adult attachment dimensions: Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R) - psychometric evaluation in a Turkish sample. Türk Psikoloji Yazıları. 2005;8(16):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deniz M, Kesici Ş, Sümer AS. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Self-Compassion Scale. Soc Behav Pers. 2008;36(9):1151–1160. 10.2224/sbp.2008.36.9.1151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendin HM, Cheek JM. Assessing hypersensitive narcissism: a reexamination of Murray’s Narcism Scale. J Res Pers. 1997;31(4):588–599. 10.1006/jrpe.1997.2204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengul BZ, Unal E, Akca S, Canbolat F, Denizci M, Bastug G. Validity and reliability study for the Turkish adaptation of the Hypersensitive Narcis-sism Scale (HSNS). Dusunen Adam. 2015;28(3):231. 10.5350/DAJPN2015280306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spector PE, Brannick MT. Common Method Variance or Measurement Bias? The Problem and Possible Solutions. The Sage Handbook of Orga-nizational Research Methods. Sage Publication; 2009:346–362. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(4):422. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei M, Liao KY, Ku TY, Shaffer PA. Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. J Pers. 2011;79(1):191–221. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosmans G, Braet C, Van Vlierberghe L. Attachment and symptoms of psychopathology: Early maladaptive schemas as a cognitive link? Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17(5):374–385. 10.1002/cpp.667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cantazaro A, Wei M. Adult attachment, dependence, self-criticism, and depressive symptoms: a test of a mediational model. J Pers. 2010;78(4):1135–62. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bradley SJ. Affect Regulation and the Development of Psychopathology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wink P. Two faces of narcissism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(4):590. 10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei M, Liao K, Ku T, Shaffer PA. Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. J Pers. 2011;79:191–221. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li T, Chan DK. How anxious and avoidant attachment affect romantic relationship quality differently: A meta-analytic review. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2012;42(4):406–419. 10.1002/ejsp.1842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(2):350. 10.1037/0022-3514.78.2.350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(1):28–44. 10.1002/jclp.21923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]