Background:

Using the hand questionnaire (HAND-Q) patient-reported outcome measure, the effects of upper extremity surgery on patients’ perception of their sex life were explored. The hand is a uniquely sexual organ, and we hypothesized that self-reported measures of disease severity, quality of life, and emotional impact would correlate with sexual dissatisfaction among patients receiving treatment for hand/upper extremity conditions.

Methods:

Patients were prospectively enrolled for hand questionnaire participation. Patients with valid responses to the following questions were included: functionality, hand appearance satisfaction, symptom severity, emotional dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, and treatment satisfaction. Composite scores were created and scored. Sexual dissatisfaction composite scores were compared through Spearman correlation coefficient analysis to quality of life, emotional dissatisfaction, hand appearance, symptom severity, and hand functionality.

Results:

High levels of diminished quality of life correlated with sexual dissatisfaction (rs = 0.748, P < 0.001). Increased emotional dissatisfaction correlated with sexual dissatisfaction (rs = 0.827, P < 0.001). Increased satisfaction with hand appearance negatively correlated with sexual dissatisfaction (rs = –0.648, P = 0.001). Increased levels of dissatisfaction with hand functionality correlated with sexual dissatisfaction (rs = 0.526, P = 0.005).

Conclusions:

The correlation between sex life and quality of life may allow surgeons to improve patient satisfaction when treating hand/upper extremity issues. The relationship between sex life and emotional dissatisfaction emphasizes the impact that sexual dissatisfaction has on patients’ lives. Evaluating the relationship between hand appearance and sexual dissatisfaction may indicate that patient self-perception of hand attractiveness plays a role in sex life.

Takeaways

Question: What effects do patient-reported outcomes have on patient sexual satisfaction following hand surgery?

Findings: In total, 204 patients responded to the sexual satisfaction component of the HAND-Q. In those whose hand problems affected their sex life, sexual dissatisfaction was correlated with decreased quality of life and decreased emotional, appearance, and functional satisfaction.

Meaning: The sexual dissatisfaction scale of HAND-Q allows for a unique evaluation of outcomes from the patient perspective following hand surgery, which is often not discussed despite its correlation with overall quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

In modern medicine, patients have become key stakeholders in their healthcare decisions.1,2 While traditional methods, such as radiographic imaging and postoperative complication rates, have been used by surgeons to interpret surgical outcomes for decades, recent literature describes the incorporation of patient satisfaction into this evaluation.3,4 Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) have since emerged as a fundamental method for assessing patient morbidity, as well as satisfaction with care.2,5

With this patient-centered focus becoming the standard of care, the patient–physician relationship has simultaneously evolved. Many studies have documented a transition that emphasizes relationship-building. Physicians can provide better treatment when an emphasis is placed on communication of patient preferences, visit expectations, and overall goals for both patient and provider.6 However, more socially taboo topics, such as sexual function, are often ignored. A questionnaire administered to 526 orthopedic surgeons and residents evaluated their ability to discuss sexual function with patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty.7 This study found that 78% of respondents almost never addressed sexual function, mostly because patients did not ask and because physicians were unaware of possible issues. This survey characterizes a universal healthcare problem defined by unclear guidelines and an unestablished standard of care for proper discussion of sexual function.

The creation of the hand questionnaire (HAND-Q) introduces an extensive survey to the list of preexisting upper extremity PROMs that uniquely expands on basic outcomes’ questions and delves deeper into the personal lives of patients undergoing a multitude of surgeries.8,9 HAND-Q was developed using internationally accepted patient-reported outcome and quality-of-life measurements.10,11 It was formulated by the creators of BREAST-Q, FACE-Q, BODY-Q, CLEFT-Q, SCAR-Q, and ACNE-Q ; validated; and widely implemented as a PROM. Similar to these existing PROMs, HAND-Q is one of the newest members of the Q-Portfolio of condition-specific PROMs that aim to investigate the impact of surgery patients’ quality of life.12–17 HAND-Q is generalized to many upper-extremity conditions involving the hand while thoroughly assessing various categories of relevant outcomes, including hand functionality satisfaction, hand appearance satisfaction, symptom severity, emotional dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, and overall treatment satisfaction.

As the popularity of PROMs has grown, systematic reviews have evaluated their development and psychometric properties.18–21 Their findings show that many commonly used PROMs, such as the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand, do not fulfill international validation guidelines by failing to implement patient input into their development.21,22 Furthermore, most PROMs were developed using psychometric methods that are now outdated. As a result, these PROMs are not accurate when measuring change over time.21 In addition, other studies have assessed surgical outcomes for various upper extremity pathologies using different PROM instruments.23,24 They demonstrate that established upper extremity PROMs are brief and generalized, therefore limiting their ability to capture the impact of upper extremity disease and surgical history on patient outcomes. These issues were addressed during the development and validation of HAND-Q. As part of the second phase of its development, a field test version HAND-Q was administered to 1277 participants from six countries with a broad range of hand conditions from April 2018 to January 2021. Using a modern psychometric analysis in the Rasch measurement theory analysis, each HAND-Q scale was evaluated for redundancy, psychometric performance, and construct validity. The results of this field test yielded the final version of HAND-Q, which contains 14 scales, each with strong reliability and validity indicators.25

One unique facet of HAND-Q is a scale pertaining to sexual dissatisfaction, as this topic is often overlooked in assessing the impact of hand/upper extremity disease on patients’ lives. The authors believe that this section of HAND-Q offers a new instrument to initiate conversation about a topic that many patients may be hesitant to discuss with their healthcare providers. Sparse literature exists on the implications of sexual dissatisfaction in treatment outcomes, especially in reference to the upper extremity. However, one study on breast augmentation demonstrates the effectiveness of PROMs in facilitating a conversation on sex, while also demonstrating surgical impacts on sexual dissatisfaction and the patient experience as a whole.26

The goal of this study was to interpret the effects of upper extremity surgery on patients’ perception of their sex life and overall experience using early data from the HAND-Q phase II field test. The authors hypothesized that the hand is a uniquely sexual organ and that self-reported measures of disease severity, quality of life, and emotional impact would correlate with sexual dissatisfaction among patients actively receiving treatment for conditions of the hand/upper extremity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients presenting to a single, board-certified, and hand/microsurgery fellowship-trained orthopedic surgeon at an outpatient hand clinic were given the option to complete the HAND-Q while waiting to be seen. Consenting patients were consecutively enrolled in the Phase II HAND-Q Pilot Multicenter International Validation Study. All patients with valid responses to the following question types were included: functionality, hand appearance satisfaction, symptom severity, emotional dissatisfaction, sexual dissatisfaction, and treatment satisfaction. Individual questions from such categories evaluated by HAND-Q answered on a scale of 1–4 are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 1. (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows selected individual questions from HAND-Q assessing patients’ hand functionality, symptom severity, and treatment satisfaction, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C201.)

Composite scores (CSs) were then created for each individual section by collating scores from individual questions. CSs for each section were calculated by summing all recorded patient answers, ranging from 1 to 4, for each question in the section, and dividing by the maximum score attainable for each section, then multiplying by 100, which established a generalizable CS scale (0–100). To be included in the CS analysis, patients were required to answer, at a minimum, all but one question.

Interpretation of CS varies for each individual section: sexual dissatisfaction [range, 0 (not at all bothered) to 100 (extremely bothered)], diminished quality of life [range, 0 (not at all) to 100 (very much)], emotional dissatisfaction [range, 0 (never) to 100 (always)], hand appearance satisfaction [range, 0 (very dissatisfied) to 100 (very satisfied)], symptom severity [range, 0 (none) to 100 (severe)], and hand functionality [range, 0 (not at all difficult) to 100 (extremely difficult)].

T-test analysis was used to compare sexual dissatisfaction CS for men versus women. Next, individual sexual dissatisfaction CSs for each patient were compared with their CSs for diminished quality of life through Spearman correlation coefficient analysis. This same method was applied to compare sexual dissatisfaction CS to each of the following categories: emotional dissatisfaction, hand appearance satisfaction, symptom severity, and hand functionality. A P value of less than 0.05 was set as threshold for statistical significance.

RESULTS

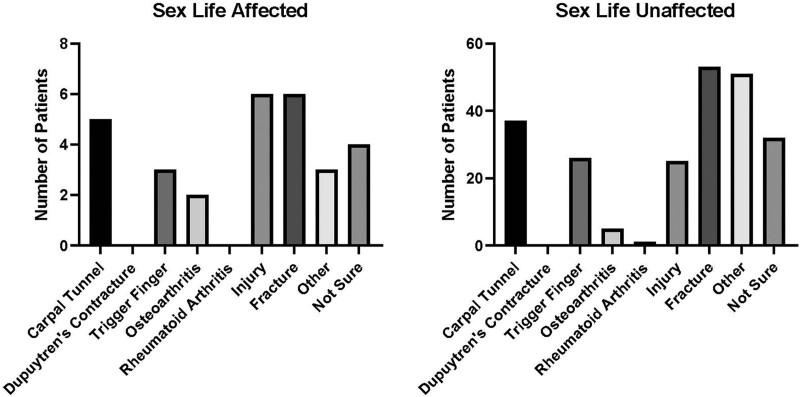

A total of 204 participants who completed the HAND-Q survey had valid responses to the initial sexual dissatisfaction section question, “Does your hand problem affect your sex life?” (did not affect sex life, n = 140; did affect sex life, n = 37; prefer not to answer, n = 27). Patients answering “did affect sex life” were then given the option to continue to the sexual dissatisfaction section of the survey. (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows selected individual questions from HAND-Q assessing patients’ hand functionality, symptom severity, and treatment satisfaction, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C201.) Of the 37 participants who selected “did affect sex life,” only 29 answered the minimum number of questions required for study inclusion. To summarize, 18.1% of the study group stated that their hand problems affected their sex life, while 68.6% of the patients were not dissatisfied with their sex life after treatment. A breakdown of the various upper extremity conditions that patients experienced is described in Figure 1 and Table 1. Although the sample size of this subgroup analysis does not provide significant power to compare differences in the procedure groups, there was a similar distribution of upper extremity pathology for those who had their sex life affected and those who did not.

Fig. 1.

Patients in this study underwent various upper extremity procedures. These graphs depict the breakdown of surgical procedures for those who reported sexual dissatisfaction (A) and those who did not report sexual dissatisfaction (B).

Table 1.

Breakdown of Surgical Procedures for Sexual Dissatisfaction Cohort and Those Unaffected

| Condition | No. Patients with Sex Life Affected, n (%) | No. Patients with Sex Life Unaffected, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel | 5 (17.2) | 37 (16.1) |

| Trigger finger | 3 (10.3) | 26 (11.3) |

| Osteoarthritis | 2 (6.9) | 5 (2.2) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Injury | 6 (20.7) | 25 (10.9) |

| Fracture | 6 (20.7) | 53 (23.0) |

| Other | 3 (10.3) | 51 (22.2) |

| Not sure | 4 (13.8) | 32 (13.9) |

The average total age of those meeting criteria who answered “did affect sex life” was 43.52 (n = 29). The average age of men (40.58, n = 12) and women (45.59, n = 17) was not significantly different (P = 0.418). The mean sexual dissatisfaction CS for all patients meeting criteria for a valid response (CS = 68.21, n = 29) was comparable between men and women (male CS = 67.08, n = 12; female CS = 69, n = 17; P = 0.844), where a higher score indicated more dissatisfaction with their hand in reference to their sex life.

To determine whether there was a relationship between patients’ feelings about their sex life and overall satisfaction, spearman correlation coefficient analysis was used to study the relationships between patients’ individual sexual dissatisfaction CS and the various other sections of HAND-Q.

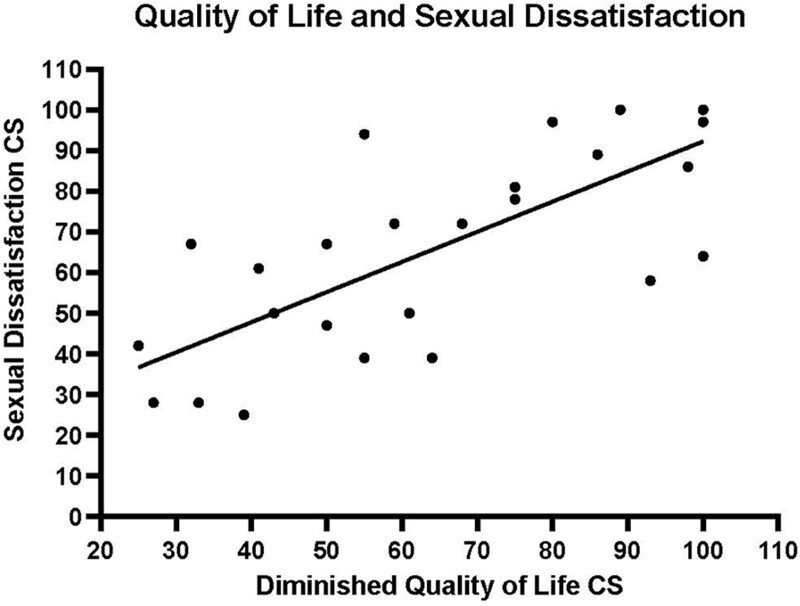

High levels of self-reported diminished quality of life strongly correlated to sexual dissatisfaction (Fig. 2, rs = 0.748, P < 0.001). This analysis elicits an overarching relationship where higher levels of sexual dissatisfaction are related to a worse overall quality of life. The following analyses delve into specific relationships between surgical outcomes and sexual dissatisfaction.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between quality of life and sexual dissatisfaction.

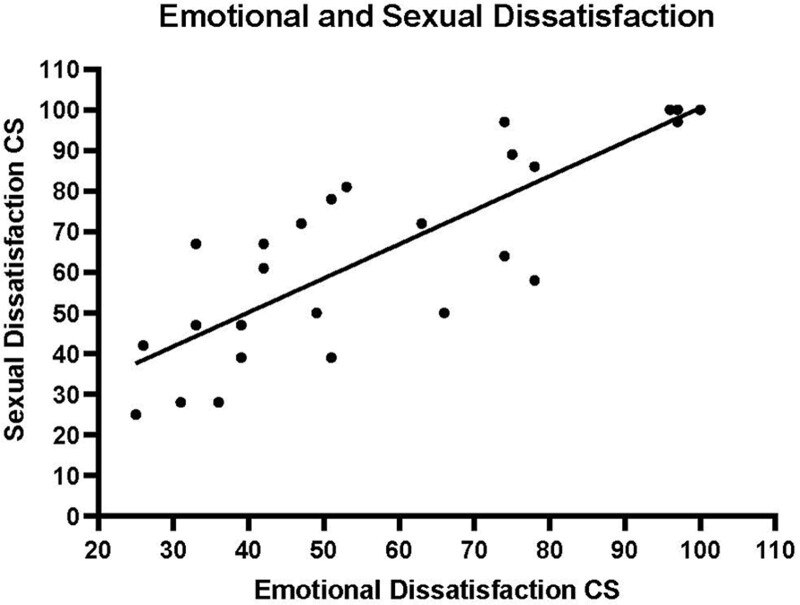

While evaluating surgical outcomes in terms of patient-reported levels of satisfaction, multiple similar relationships were discovered. Increasing levels of emotional dissatisfaction demonstrated a strong correlation with sexual dissatisfaction (Fig. 3, rs = 0.827, P < 0.001). This figure illustrates that patients who reported higher levels of sexual dissatisfaction also experienced more emotional dissatisfaction.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between emotional dissatisfaction and sexual dissatisfaction.

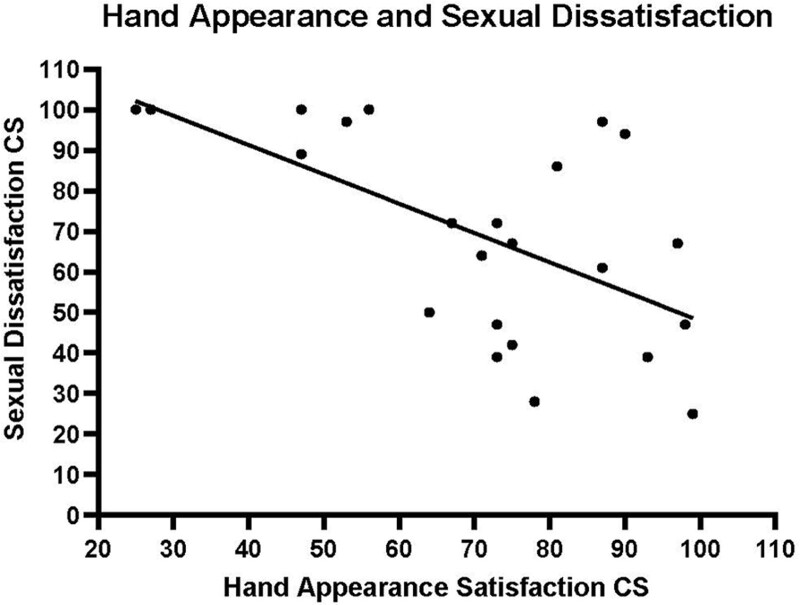

Increased satisfaction with hand appearance demonstrated a strong negative correlation with sexual dissatisfaction (Fig. 4, rs = –0.648, P = 0.001). In agreement with past relationships, patients who reported higher levels of sexual dissatisfaction also experienced a decreased level of satisfaction with the appearance of their hands.

Fig. 4.

Relationship between hand appearance and sexual dissatisfaction.

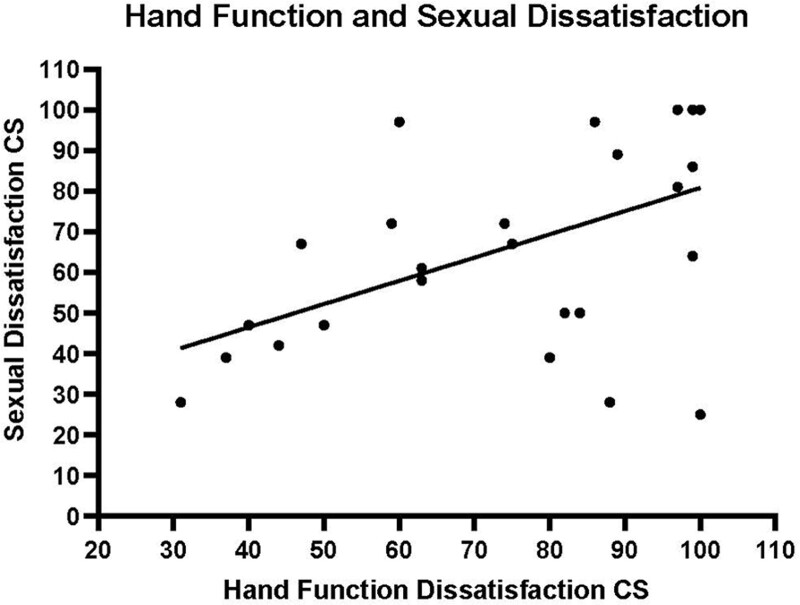

Along with a significant correlation to hand appearance, increased levels of dissatisfaction with hand functionality were also found to be correlated to sexual dissatisfaction (Fig. 5, rs = 0.526, P = 0.005). Therefore, patients who reported higher levels of sexual dissatisfaction also had decreased ability to use their hands.

Fig. 5.

Relationship between hand function and sexual dissatisfaction.

No evidence was found of a correlation between disease severity and sexual dissatisfaction (rs = –0.108, P = 0.562). This indicates that the severity of the hand condition has no relationship with sexual dissatisfaction.

DISCUSSION

A fundamental aspect of patients’ lives is the ability to give and receive sexual pleasure. Patients may be uncomfortable discussing issues that arise in their sexual life, which was demonstrated in our study. Of the 204 participants, 27 individuals selected the option “prefer not to answer” for the sexual dissatisfaction section, while eight of the 37 who selected “did affect sex life” chose not to fully answer all the questions in this section. Although reasoning for these decisions was not identified, it is inferred that participants were uncomfortable with the detailed questions related to sexual function.

Clinicians may also be uncomfortable initiating conversations about sex, especially in a surgical clinic setting without being trained to do so. This was demonstrated in a questionnaire administered to orthopedic surgeons and residents evaluating their ability to discuss sexual function with patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty.7 Although minimal research has been conducted in this field, this topic permeates into other specialties of medicine.

A recent systematic review highlighted ten articles that describe the ineffectiveness of communication about sexual healthcare between patients and nurses.27 In journals from across the world, it has been reported that nurses believe sexual healthcare is a private matter as opposed to a priority. Furthermore, nurses actively avoid initiating these conversations. Another Dutch study surveyed plastic surgeons to determine whether the topic of sexual function was discussed in their clinics.28 Most surgeons indicated that they rarely or never discussed sexual function with their patients, and the majority of them felt that their knowledge on the subject was insufficient.

This literature highlights a disconnect between patients and healthcare providers when it comes to discussing sex. However, when patients were administered the HAND-Q, which contained the option to elaborate on sexual dissatisfaction, many patients willingly expressed their feelings. It appears that a PROM medium can help to facilitate the dialogue on sexual function and sexual dissatisfaction for some patients.

It is imperative to understand the vital role of sexual function in discussions between patients and clinicians when determining care, as well as the consequences of such conversations. In one study, Nosek et al29 found highly significant differences in levels of sexual activity and satisfaction between women with and without disabilities. However, there was no difference found in sexual desire between the groups. Interestingly, young adults with limiting disabilities were also found to report adverse sexual health outcomes compared with those without, including feeling distressed/worried about their sex life and experiencing nonvolitional sex.30 These results indicate how self-perceived disabilities can negatively affect sex life and, by association, lead to worse overall health satisfaction.

In one review series, 44 PROM studies assessing the outcomes of large joint reconstruction surgery and the effects on sexuality were appraised and summarized. It was found that total hip replacement increases sexual satisfaction and performance, while also facilitating improved body image and greater self-confidence.31 This review highlights the effectiveness of PROMs in assessing surgical outcomes in a patient-centered way. Unsurprisingly, the functional integrity of the hip is important for sexual function. The authors propose that the hand has an equally profound role.

While studies in various fields provide valuable insight into the effects of physical disability on sexual function and behavior, there is an absence of literature that examines the relationship between hand and upper extremity disability and sexual function. The novelty of the following correlations demonstrates only the presence of their existence, which warrants further investigation.

The relationships between patients’ sexual dissatisfaction and their quality of life, emotional dissatisfaction, hand appearance, and hand function demonstrate connections between sexual dissatisfaction and general well-being. Those who view their hands as disfigured also reported a worse quality of life as well as a worse sex life. These findings agree with past literature and imply that body disfiguration plays a key role in multiple facets of patients’ lives. This may indicate the essential sexual function of the hand, as well as the hand posing as an extension of sexual self-image. Hand pathologies may limit patients’ sexual capabilities and, in turn, their quality of life. Due to limitations in the questionnaire and analysis, the authors can only comment on these existing relationships. HAND-Q was administered once after surgery and, therefore, only allows the authors to assess patients’ sexual experience at a single point in time. Although the evidence in this study demonstrates a correlation, a direct association cannot be concluded. However, further research into the effects of hand and upper extremity surgery on sexual outcomes is warranted.

A limitation of this study is that only 29 of the 37 patients who answered that their hand disability “did affect sex life” completed the questionnaire. Furthermore, unfortunately, an additional 27 patients chose not to answer. Thus, a large volume of patients were not captured by this study, and possibly, different administration techniques could have ameliorated our dropout.

CONCLUSIONS

In a society where the topic of sexual dissatisfaction is considered taboo in conversations between healthcare providers and patients, the implementation of PROMs that specifically address sex offers a novel facet to stimulate this conversation. Incorporating a sexual dissatisfaction component into HAND-Q opened the door for a cross-analysis of various postsurgical patient experiences. This lens allows new relationships to be assessed and poses the concept of the hand as a uniquely sexual organ.

The strong correlation between sex life and quality of life may provide hand surgeons with a way to improve patient satisfaction when treating hand/upper extremity issues. The relationship between sex life and emotional dissatisfaction emphasizes the impact that sexual dissatisfaction has on patients’ lives and further describes the patients’ experience. Finally, evaluating the relationship between hand appearance and sexual dissatisfaction may indicate that patient self-perception of hand attractiveness plays a role in sex life.

The findings in this study show that HAND-Q is a powerful instrument to detect important information regarding the biopsychosocial impact of disease/treatment among hand/upper extremity patients. This survey may provide a method for asking important questions that physicians may have previously avoided in clinic. Sexual dissatisfaction is a relatively novel focus in hand surgery and may aid surgeons in evaluating treatment success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Neil V. Shah, MD, MS, and Hassan M. Eldib, BS, from the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine, State University of New York (SUNY), Downstate Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY.

ETHICAL APPROVAL STATEMENT

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

PATIENT CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 24 October 2022.

Disclosure: Dr. Koehler is a committee member of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH), a paid consultant for Integra LifeSciences, Inc, a paid consultant for Tissium, Inc., a stockholder and member of the medical advisory board for Reactiv, Inc., and a consultant for TriMed, Inc. The other authors have no financial interest to declare.

Related Digital Media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSGlobalOpen.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin M, Spong A, Doward L, et al. Patient-reported outcomes, patient-reported information: from randomized controlled trials to the social web and beyond. Patient. 2011;4:11–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anker SD, Agewall S, Borggrefe M, et al. The importance of patient-reported outcomes: a call for their comprehensive integration in cardiovascular clinical trials. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2001–2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergman S, Feldman LS, Barkun JS. Evaluating surgical outcomes. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:129–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chow A, Mayer EK, Darzi AW, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures: the importance of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery. 2009;146:435–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvert MJ, Freemantle N. Use of health-related quality of life in prescribing research. Part 1: why evaluate health-related quality of life? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28:513–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frankel RM. Relationship-centered care and the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1163–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harmsen RTE, Nicolai MPJ, Den Oudsten BL, et al. Patient sexual function and hip replacement surgery: a survey of surgeon attitudes. Int Orthop. 2017;41:2433–2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sierakowski K, Dean NR, Pusic AL, et al. International multiphase mixed methods study protocol to develop a cross-cultural patient-reported outcome and experience measure for hand conditions (HAND-Q). BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sierakowski K, Kaur MN, Sanchez K, et al. Qualitative study informing the development and content validity of the HAND-Q: a modular patient-reported outcome measure for hand conditions. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e052780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research et al. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims: draft guidance. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4(79). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen WA, Mundy LR, Ballard TN, et al. The BREAST-Q in surgical research: a review of the literature 2009-2015. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:149–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappos EA, Temp M, Schaefer DJ, et al. Validating facial aesthetic surgery results with the FACE-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:839–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klassen AF, Lipner S, O’Malley M, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure to evaluate treatments for acne and acne scarring: the ACNE-Q. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1207–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klassen AF, Ziolkowski N, Mundy LR, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome instrument to evaluate treatments for scars: the SCAR-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6:e1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Alderman A, et al. The BODY-Q: a patient-reported outcome instrument for weight loss and body contouring treatments. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziolkowski NI, Pusic AL, Fish JS, et al. Psychometric findings for the SCAR-Q patient-reported outcome measure based on 731 children and adults with surgical, traumatic, and burn scars from four countries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:331e–338e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wormald JCR, Geoghegan L, Sierakowski K, et al. Site-specific patient-reported outcome measures for hand conditions: systematic review of development and psychometric properties. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019;7:e2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dacombe PJ, Amirfeyz R, Davis T. Patient-reported outcome measures for hand and wrist trauma. HAND. 2016;11:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd-Hughes H, Geoghegan L, Rodrigues J, et al. Systematic review of the use of patient reported outcome measures in studies of electively-managed hand conditions. J Hand Surg Asian Pac Vol. 2019;24:329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sierakowski K, Evans Sanchez KA, Damarell RA, et al. Measuring quality of life and patient satisfaction in hand conditions: a systematic review of currently available patient reported outcome instruments.tle. Australas J Plast Surg. 2018;1:58–99. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand) [corrected]. The Upper Extremity Collaborative Group (UECG). Am J Ind Med. 1996;29:602–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Y, Chen X, Li Z, et al. Safety and efficacy of operative versus nonsurgical management of distal radius fractures in elderly patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41:404–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin JS, Samora JB. Surgical and nonsurgical management of mallet finger: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:146–163.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sierakowski KL, Dean NR, Evans Sanchez K, et al. The HAND-Q: psychometrics of a new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical and research applications. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2022;10:e3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guimarães PA, Resende VC, Sabino Neto M, et al. Sexuality in aesthetic breast surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39:993–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fennell R, Grant B. Discussing sexuality in health care: a systematic review. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3065–3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dikmans RE, Krouwel EM, Ghasemi M, et al. Discussing sexuality in the field of plastic and reconstructive surgery: a national survey of current practice in the Netherlands. Eur J Plast Surg. 2018;41:707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nosek MA, Rintala DH, Young ME, et al. Sexual functioning among women with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77:107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holdsworth E, Trifonova V, Tanton C, et al. Sexual behaviours and sexual health outcomes among young adults with limiting disabilities: findings from third British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). BMJ Open. 2018;8:e019219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meiri R, Rosenbaum TY, Kalichman L. Sexual function before and after total hip replacement: narrative review. Sex Med. 2014;2:159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.