Abstract

Objective:

The objective of the study is to demonstrate the innovation and utility of mesenteric tissue culture for discovering the microvascular growth dynamics associated with adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction (SVF) transplantation. Understanding how SVF cells contribute to de novo vessel growth (i.e., neovascularization) and host network angiogenesis motivates the need to make observations at single-cell and network levels within a tissue.

Methods:

Stromal vascular fraction was isolated from the inguinal adipose of adult male Wistar rats, labeled with DiI, and seeded onto adult Wistar rat mesentery tissues. Tissues were then cultured in MEM + 10% FBS for 3 days and labeled for BSI-lectin to identify vessels. Alternatively, SVF and tissues from green fluorescent-positive (GFP) Sprague Dawley rats were used to track SVF derived versus host vasculature.

Results:

Stromal vascular fraction-treated tissues displayed a dramatically increased vascularized area compared to untreated tissues. DiI and GFP+ tracking of SVF identified neovascularization involving initial segment formation, radial outgrowth from central hub-like structures, and connection of segments. Neovascularization was also supported by the formation of segments in previously avascular areas. New segments characteristic of SVF neovessels contained endothelial cells and pericytes. Additionally, a subset of SVF cells displayed the ability to associate with host vessels and the presence of SVF increased host network angiogenesis.

Conclusions:

The results showcase the use of the rat mesentery culture model as a novel tool for elucidating SVF cell transplant dynamics and highlight the impact of model selection for visualization.

Keywords: angiogenesis, mesentery, microcirculation, stromal vascular fraction, vasculogenesis

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The isolation of adipose stromal cells with multi-lineage differentiation potential was first reported in the peer-reviewed literature in 2001.1 In recent years, the use of stromal vascular fraction (SVF) has emerged as an alternative therapeutic strategy to form new vessels, with its use in clinical trials growing exponentially.2 SVF has become an ideal candidate in vascular therapeutics due to the ability to leverage a real-time autologous point-of-care therapeutic approach, thereby avoiding excessive costs related to good manufacturing practice and logistical obstacles related to cell transport, storage, tracing, and inventory. SVF includes multiple cell types and can be thought of as a heterogeneous mixture of leukocytes, erythrocytes, stromal cells, progenitor cells, endothelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells, pericytes, and other cells of the perivascular niche.3,4 Though SVF as a therapeutic has entered into clinical testing for a variety of pathologies such as osteoarthritis,5 chronic heart ischemia,6 angina,7 and pulmonary fibrosis,8 none to date are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). While these clinical trials have shown the beneficial effects of SVF administration, questions regarding treatment timing, cell dose, and duration remain. There is a need to better understand how SVF cells spatially and temporally contribute to neovascularization and blood flow within a vascular bed. The ultimate goal is to deliver cells to influence and promote microvascular growth and function. Since microvascular remodeling is a complex process involving multiple cell types, a heterogeneous cell therapy such as SVF may be more conducive to vascularization than single homogenous cell approaches. A heterogeneous cell composition might provide the unknown optimal milieu of environmental cues.9 As of now, we know that SVF can dramatically affect the presence of new vessels both in vivo and in vitro,10,11 possibly due to engraftment into the host vasculature12 or release of angiogenic growth factors.13 This study will examine the former of the two paradigms and address the knowledge gaps concerning how SVF spatially and temporally incorporates within living tissues and promotes microvascular growth and remodeling.

The identification of SVF dynamics during neovessel formation and integration with host microvascular networks can be thought of as an imaging challenge. Meeting this challenge requires the ability (1) to view SVF cell populations in a real tissue environment at the single-cell level and (2) to view changes in the existing vasculature over time. These experimental challenges require investigators to make decisions related to the imaging technology and the experimental model. Potential in vivo models include two-photon imaging of brain vasculature (cranial window) or the use of dorsal window chamber models via intravital microscopy.14,15 These models incorporate the necessary complexity of microvascular networks in situ; however, they have yet to be used for SVF characterization because of the technical difficulties associated with SVF transplantation, repeated imaging, and the need for invasive survival surgeries.16 In comparison, in vitro studies involving culturing SVF in two-dimensional or three-dimensional substrates represent a simplified environment that allows for easier time-lapse imaging needed to track vessel formation dynamics. Such methods have proven valuable for reductionist studies focused on concentration-dependent and matrix-dependent effects.11,17 However, in vitro methods do not offer a view of an intact host microvascular network and the impact of host-derived cell signaling factors is not considered.

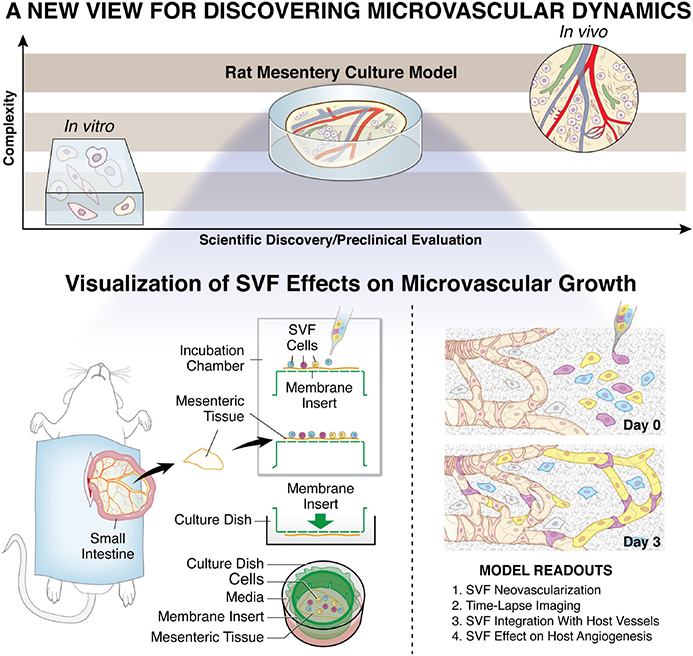

Within the last decade, our laboratory has developed the rat mesentery ex vivo culture model to bridge the gap between in vitro and in vivo (Figure 1). Traditionally used for intravital microscopy because it is 20–40 μm thick, the rat mesentery is relatively easy to image with common epifluorescent microscopes. The thinness also makes it ideal for continued culturing and despite being excised, mesenteric windows survive up to at least 7 days.18 We have shown that the culture model enables time-lapse investigation of cell–cell interactions at specific locations across blood and lymphatic microvascular networks.18–21 The physiological relevance of the model is supported by demonstration of the functional effects of pericytes on endothelial cell sprouting, smooth muscle cell contraction along arterioles, and the maintenance of in vivo-like endothelial cell phenotypes along capillary sprouts during angiogenesis.18,22,23 The objective of this study was to showcase the use of the rat mesentery culture model as a platform for visualizing SVF cell dynamics and effects on the host vasculature (Figure 1). Our results confirm that SVF can be translated onto the mesentery tissue and integrated into the networks when cultured for 3 days, thus offering a new view for SVF-derived vasculogenesis and interactions with the host vasculature. The SVF formed unique networks that connected with the pre-existing host networks. In addition, SVF-induced host microvascular network angiogenesis and examples of individual cells were observed to be integrated along individual host vessel segments. This study demonstrates the therapeutic potential of SVF and the importance of SVF interaction with the host microvascular network. The results further showcase the use of the rat mesentery culture model for visualizing SVF neovessel formation, time-lapse dynamics, and SVF effects on a live tissue. The comprehensive readouts will serve to guide our understanding of SVF transplantation.

FIGURE 1.

The rat mesentery culture model enables the visualization of SVF effects on microvascular growth. A gap in complexity exists between common three-dimensional in vitro cell culture methods and in vivo systems. The rat mesentery culture model fills this gap by maintaining tissue complexity, while enabling observation over a short time course. For the visualization of SVF dynamics, SVF can be pipetted onto tissues prior to culture. Mesenteric tissues are surgically removed, rinsed in buffered saline, and placed in media. Post cell seeding, tissues are inverted into a culture well and covered with media. Readouts include SVF neovascularization, time-lapse imaging, SVF integration with host vessels, and effects on host network angiogenesis. SVF, stromal vascular fraction

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Animal use

The University of Florida Animal Care and Use Committee approved all experimental protocols. Adult male Wistar rats were anesthetized via intramuscular injection with ketamine (80 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (8 mg/kg body weight). Adult male Wistar rats were used to be consistent with previously published studies in our laboratory using the rat mesentery culture model. Sprague Dawley EGFP rats (Rat Resource and Research Center; 800–1000 g) were anesthetized via isoflurane. The specific strain and weight of Sprague Dawley EGFP rats were used because of availability through a collaboration at the time of the study. Adult Fischer 344 rats were used for immunolabeling endothelial cells and pericytes; rats were anesthetized via intramuscular injection with ketamine (80 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (8 mg/kg body weight). Post tissue harvesting and/or SVF isolation, all rats were euthanized by intracardiac injection of Beuthanasia (0.2 ml).

2.2 |. Rat mesentery tissue harvesting, SVF transplantation, and culture

Rat mesenteric tissues were harvested and cultured according to a previously established protocol.20,24 To harvest mesenteric tissues, the abdominal region was shaved and then sterilized with 70% isopropyl and iodine alcohol before an incision was made along the linea alba. The mesentery was exteriorized onto a sterile plastic stage using cotton tip applicators to first remove the cecum and subsequently the ileum and jejunum. Vascularized mesenteric tissues were excised and rinsed once in sterile saline (0.9% NaCl; Baxter) and then immersed in minimum essential media (MEM; Gibco) containing 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin (PenStrep; Gibco) at 37°C. Isolated SVF cells were suspended in 10% FBS + MEM solution at a concentration of 10 million cells/ml. Tissues were then spread onto a polycarbonate filter membrane (pore size = 5 μm) on a cell crown. 100 μl of SVF solution was transferred to the surface of each mesenteric window before incubating for 20 min so the SVF cells were attached to the tissue (Figure 1). Cell crowns were then inverted into a six-well plate with the fat of the tissue pressing against the bottom of the well. 3 ml of culture media composed of 10% FBS + MEM was then added to each well on top of the filter. Tissues were cultured in standard incubation conditions (5% CO2, 37°C) for 3 days.

2.3 |. Adipose tissue harvesting and SVF isolation

A scalpel was used to make a Y-shaped incision into the skin from the bottom of the previous incision of the linea alba to each of the inner thighs along the midline, stopping above the knee. The skin was carefully removed from the subcutaneous adipose and muscle layers using the scalpel and microscissors. Hemostats were used to hold the skin back as the separation was advanced to the coxal region. The center skin flap of the pelvic region was removed in a similar fashion. The inguinal fat pad was removed in a continuous strip from one hip and leg to the other and placed in a 50 ml conical tube containing sterile saline at 37°C.

Fat was placed onto a large petri dish and diced into fine pieces before being transferred into an empty 50 ml conical tube for weighing. Once weight was measured, a 0.15% collagenase type 1 (Thermo Fisher) and DPBS solution heated to 37°C was prepared. Collagenase solution was pushed through a 0.22 μm filter with a syringe for sterilization at a ratio of 2 ml per 1 g of fat. In the event that the fat weighed <3 g, 5 ml was used to ensure enough volume was in the conical tube containing the diced adipose. The collagenase/adipose mixture was then transferred to a shaker set to 150 rpm and digested for 45 min at 37°C. After digestion, the mixture was centrifuged for 10 min at 600 g to separate the cells from the collagenase and the undigested fat. The top layer of undigested fat was transferred to a new conical tube containing the same volume of fresh filtered collagenase and transferred back to the incubator for a second digestion. The collagenase solution was then removed from the centrifuged tube and the bottom layer of cells was resuspended in 5 ml of 5% FBS + DPBS. The resuspended mixture was filtered through a 250 μm cytostrainer into a new 50 ml conical tube then centrifuged at 600 G for 5 min. Media was removed and 5 ml of ACK lysing buffer (Thermo Fisher) was added to the cells through a 0.22 μm filter for sterilization. The solution was then gently shaken in the dark at room temperature for 3 min. Immediately afterwards, 5 ml of 5% FBS + DPBS was added to the solution to neutralize the lysing buffer. This solution was filtered through a 70 μm filter into a new conical tube and the centrifuged for 5 min at 600 g. The media was removed, and the remaining SVF was resuspended with 1 ml of 5% FBS + DPBS. 10 μl of the SVF solution was added to 10 μl of trypan blue, mixed, and then added to a disposable slide for cell counting with a Countess™ II Automated Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher).

2.4 |. Immunohistochemistry

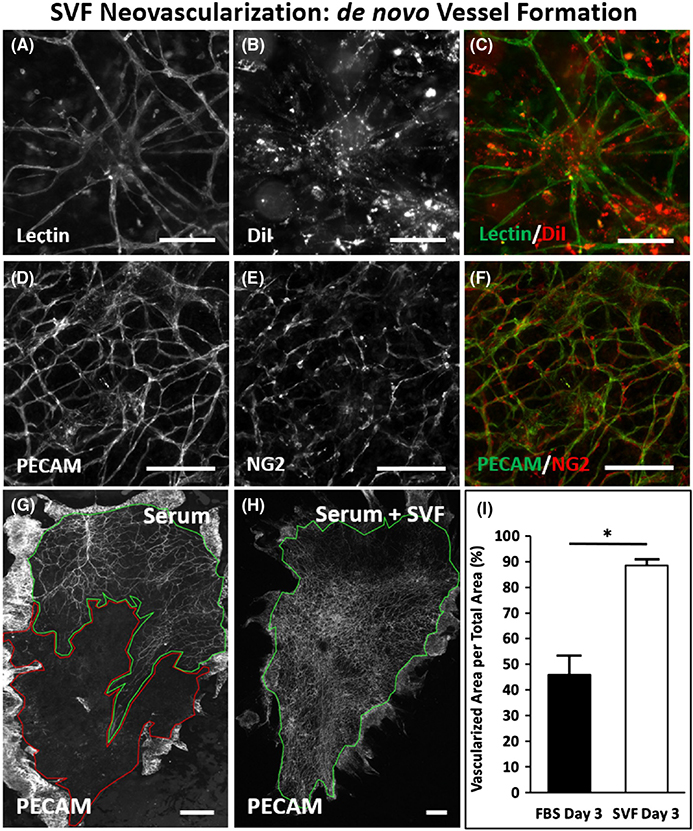

Cultured tissues were fixed in methanol for 30 min at −20°C. Tissues were spread on glass slides before being rinsed three times for 10 min in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS) +0.1% saponin. Fat around the windows was removed and a hydrophobic barrier was applied around the tissue before being labeled for either platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM; endothelial cell marker) or PECAM plus Neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2; pericyte marker): Tissues were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a primary antibody solution of 1:200 mouse monoclonal biotinylated anti-PECAM antibody (CD31 antibody, BD Pharmigen) with 1:100 rabbit polyclonal anti-NG2 antibody (Millipore/Chemicon). Tissues were then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a secondary antibody solution of 1:500 CY3-conjugated Streptavidin secondary (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) and 1:100 goat anti-rabbit CY2-conjugated antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). Antibodies were diluted in antibody buffer solution comprised of PBS (Sigma-Aldrich) + 0.1% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich) + 2% bovine serum albumin (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories) + 5% normal goat serum (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories). After each antibody incubation period, the tissues were submerged in PBS + 0.1% saponin for 3 × 10 min washes. The representative images shown in Figure 2 were obtained from experiments involving tissues and SVF harvested from adult Fischer 344 rats.

FIGURE 2.

SVF formation of new vessels via neovascularization. (A–C) Example of cluster and outgrowth pattern of SVF-derived cells after 3 days in culture. DiI labeled SVF cells identify lectin-positive central hubs with spoked vascular branching. (D–F) PECAM and NG2 labeling of SVF formed vessels, indicating the presence of endothelial cells and vascular pericytes. (G,H) Images comparing the vascular area per tissue area for tissues cultured with serum and serum plus SVF. Green outline indicates vascularized area. Red outline indicates avascular area. (I) Quantitative analysis of percent vascularized area was significantly higher in the SVF-treated tissues compared to serum alone (n = 4 tissues from two rats per group). *represents p < .05. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Scale bars = 100 μm (A–F), 2 mm (G,H). SVF, stromal vascular fraction

2.5 |. Cell and vascular network tracking studies

In order to investigate the fate of the SVF and the microvascular networks to which they were transplanted, cell tracking models were implemented. For the first experimental model, DiI solution was mixed with MEM to make a 5 μl/ml labeling solution. Isolated adult male Wistar SVF cell suspension was centrifuged, aspirated, and resuspended in the DiI solution. The SVF was then incubated for 5 min at 37°C followed by 10 min incubation at 4°C. The SVF suspension was centrifuged at 600 g for 5 min and the labeling media was replaced with suspension media. Cells were then centrifuged again and washed for two more times before being seeded onto Wistar tissues according to the protocol above. After 3 days, BSI-Lectin conjugated to FITC (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to media in a 1:40 ratio, transferred to the well containing the seeded tissue, and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After incubation, the supplemented media was removed, and the tissues were subsequently rinsed with label-free media. To preserve DiI labeling, tissues were fixed in methanol-free 4% formaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature.

In another experiment, SVF from GFP rats was transplanted onto unlabeled Adult Wistar tissues. The six-well plates containing these tissues were then placed into a culture chamber mounted on a microscope stage to maintain a temperature of 37°C. Two to four microvascular networks were imaged per tissue every 24 h using an inverted epifluorescent microscope. After 3 days, tissues were labeled with TRITC lectin according to the same protocol above and imaged again.

The third tracking experimental group used adult male Wistar SVF on GFP tissues. The time-lapse was performed as described above. Following a 3-day culture, TRITC lectin labeling of the whole tissue was performed as described above and imaged again.

2.6 |. Image acquisition

Images were acquired using 4× (dry, NA = 0.1), 10× (dry, NA = 0.3), and 20× (oil, NA = 0.8) objectives on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti2) coupled with an Andor Zyla sCMOS camera. Image analysis and quantification were done using ImageJ 2.0.0-rc-54 (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).25

2.7 |. Statistical analysis

Two statistical comparisons were made in this study. In order to evaluate the effects of SVF on tissue vascular area, a comparison was made using a two-tailed Student's t-test between two experimental groups: FBS alone (control) and SVF + FBS. In order to evaluate the effects of SVF, a comparison was made using a paired t-test between the vascularized areas of native vessels in GFP tissues at Day 0 and Day 3. Results were considered statistically significant when p ≤ .05. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaStat ver. 3.5 (Systat Software). Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. SVF formation of new vessels via neovascularization

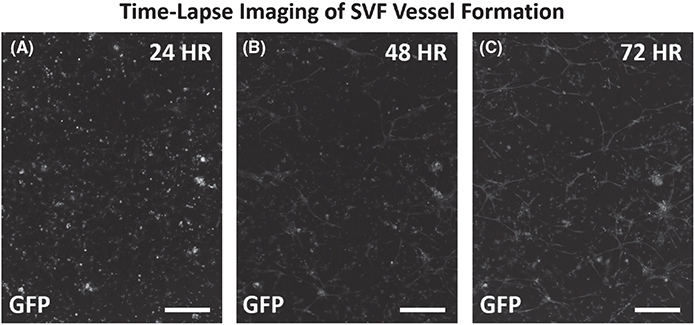

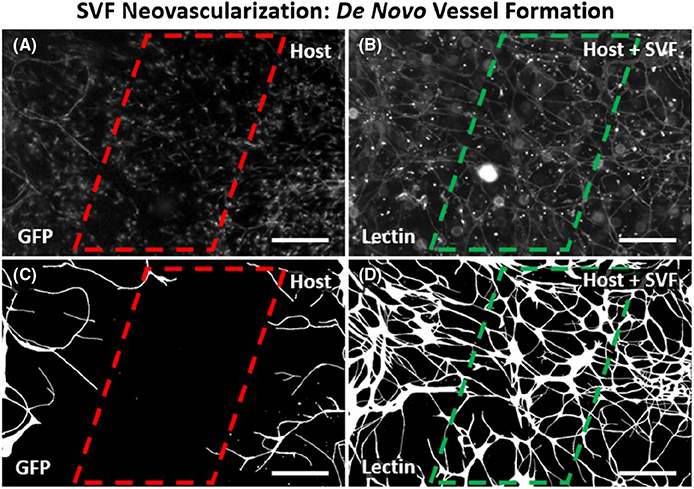

Visualization of microvascular growth dynamics using the rat mesentery culture model enables identification of SVF-derived neovascularization. Lectin labeling of tissues after DiI-positive SVF transplantation and culture for 3 days revealed clusters of vessels with a central hub and radial outgrowth (Figure 2A–C). This unique pattern was unlike the typical branching hierarchy of mesenteric vessels and resembled the aggregation and sprouting dynamics reported for SVF vessel formation in vitro.11 Positive DiI labeling identified the central hub structure and the radial spoke structures indicating SVF origin (Figure 2B). Lectin co-labeling of the radially patterned segments isolated from nearby host networks characterized by hierarchical branching suggests that the segments were SVF-derived. PECAM and NG2 labeling of the apparent hub and spoke patterned structures confirmed that vessel segments contained endothelial cells and vascular pericytes (Figure 2D–F). NG2 labeling revealed pericytes along vessels extending from the central hub aggregates and the branching vessels that connected the hubs (Figure 2E). After 3 days of culture, the SVF-treated tissues displayed a dramatic increase in percentage of vascularized area, indicative of new vessel formation (Figure 2G–I). The vascular coverage increased nearly twofold compared with serum stimulation alone (88.5 ± 2.2% vs. 45.9 ± 6.9%, p = .0004) (Figure 2G–I). Lectin labeling of the networks in the SVF-transplanted tissues identified an intact network with no apparent distinction between the host and SVF-derived vessels. The apparent increased vascularized areas were also covered with branching capillary networks. SVF neovascularization is further supported by comparing the locations of host vessels versus host and SVF vessels. Such a comparison was made possible by transplantation of wild-type SVF on GFP tissues (Figure 4). After 3 days in culture, areas void of GFP-positive vessel segments were observed between GFP-positive host networks. This same region contained GFP-negative, lectin-positive vessels, indicating SVF neovascularization had formed connections between the networks. SVF-derived neovascularization is also supported by time-lapse imaging of SVF from transgenic GFP rats which was used to track vasculogenesis over time (Figure 4). SVF tracking revealed three phases involved in initial vessel formation: initial segment formation, segment network formation, and the connection of branched segment networks (Figure 3A–C). Segments were defined by the apparent elongation of individual cells and segment networks were classified as networks made up of two or more connected segments.

FIGURE 4.

Time-lapse imaging of initial SVF vessel formation. (A–C) Example images of GFP-positive SVF cells over the initial vessel development time course. GFP sourced SVF was seeded onto tissues at the start of the culture duration. (A) At 24 h the GFP cells appeared unassembled. (B) By 48 h GFP structures were observed in assembled segments. (C) By 72 h assembled segments formed connections. In some regions, a central hub with outward radial segment growth was identified. Scale bars = 250 μm. GFP, green fluorescent positive; SVF, stromal vascular fraction

FIGURE 3.

Observation of host microvasculature versus SVF-derived vessels confirms neovascularization. (A,B) Images of GFP-positive host vessels and all vessels in the same tissue region after 3 days in culture. Tissues were harvested from GFP transgenic rats allowing for identification of host tissue vessel segments. Lectin labeling identifies all vessels including the host vessels and new SVF-derived vessels. GFP-negative, lectin-positive segments indicate SVF origin. (C,D) Corresponding processed images more clearly show connected vessel segments because lectin and GFP labeling also identifies non-vascular interstitial cells. Vessel segments were defined by continuous labeling and connection within a network. Observation of lectin-positive segments spanning the gap between GFP-positive vessel labeling supports the formation of SVF-derived vessels. Scale bars = 100 μm. GFP, green fluorescent positive; SVF, stromal vascular fraction

3.2 |. SVF association with host vessels and effect on angiogenesis

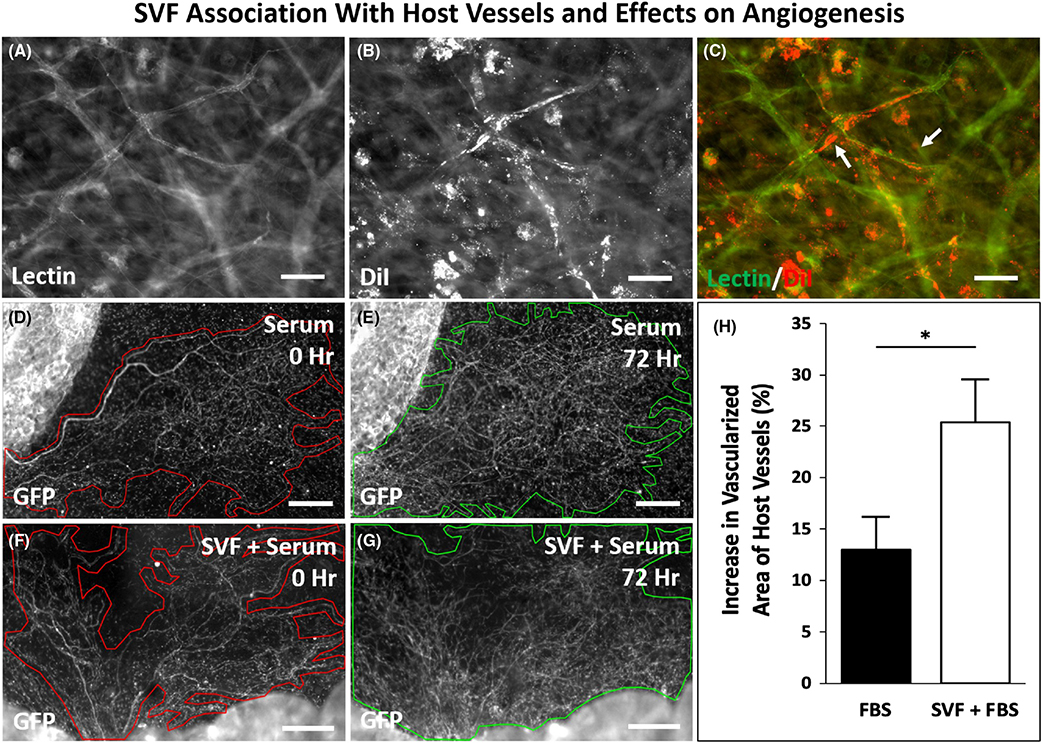

The visualization of microvascular growth dynamics using the rat mesentery culture model also enables observation of SVF associating with host vessels and SVF effects on angiogenesis. In support of the potential for SVF association along host vessels, examples of DiI-positive SVF cells were observed along lectin vessels (Figure 5A–C). DiI-positive cells were also observed in the interstitial space not associated with vessels. These cells associated with vessels were only observed to be present along capillaries and not observed along larger diameter arterioles, larger diameter venules, or initial lymphatic vessels (data not shown). The different vessel types were identified based on previously described characteristic morphologies and position within a network consistent.18,21 Finally, to determine the effect of SVF on host tissue angiogenesis, vascularized area measurements were compared for GFP host tissues with wild-type SVF versus no SVF transplantation control groups (Figure 4D–G). For this experiment, GFP only identified the native, host-derived networks and comparison of Day 0 versus Day 3 vascularized area per tissue allowed for the quantification of network expansion due to angiogenesis. Day 3 tissues treated with SVF displayed a significant increase in vascular coverage compared to tissues treated with serum alone (25.3 ± 4.2 % vs. 13.0 ± 3.2%, p = .0017) indicating a proangiogenic effect (Figure 4H).

FIGURE 5.

SVF can associate with host vessels and stimulate host network angiogenesis. (A–C) Example of DiI-positive SVF-derived cells along DiI-negative, lectin-positive vessel segments. (D–H) Analysis of the effect of SVF on host network angiogenesis. DiI-positive cells can also be observed not-associated with vessels in the interstitial space. (D–H) Representative network images of tissues harvested from GFP transgenic rats at 0 and 72 h for two experimental groups: cultured with serum (FBS) and cultured with serum (FBS) + wild-type SVF. Outlines identify circumscribed vascular areas per network. (H) Quantification of the percent increase in the vascularized area of native GFP vessels after 3 days in culture with serum alone or serum plus SVF (n = 6 tissues from two rats per group). *represents p < 0.05; values are shown as mean ± SEM. Scale bar = 50 μm. GFP, green fluorescent positive; SVF, stromal vascular fraction

4 |. DISCUSSION

Stromal vascular fraction implantation in vivo has been shown to result in the formation of patent microvessels.28–30 Yet, current SVF therapies have not reached their full potential due to the lack of understanding concerning the processes related to how SVF contributes to the growth and remodeling of a vascular network. The infancy of SVF research and our lack of information surrounding the mechanisms of SVF function motivates the need to view the relative contributions of SVF effects on host network angiogenesis, host vessel integration, and neovessel formation. Discovery of SVF dynamics will guide new paradigms for research and therapeutic design.

Visualizing cell dynamics across temporal and spatial scales is a key challenge in advancing our understanding of the microvasculature. Imaging cellular in vitro systems does not accurately mimic the complexity of real vascular networks and imaging of in vivo systems is often limited to end time points. To this end, in vitro models are valuable for reductionist experiments investigating what players are important for vessel formation and in vivo models are essential for evaluating functional effects. For example, in vitro studies have shown the importance of the extracellular matrix environment; SVF cultured on collagen, gelatin, and laminin formed monolayers while SVF cultured on Matrigel formed microvascular networks.11 As an in vivo example, a study by Koh et al. demonstrated that SVF injection can cause neovascularization via cell re-assembly and increase blood perfusion post hindlimb ischemia.28 Previous studies utilizing SVF therapy to improve tendon, cardiac, and nerve regeneration also emphasize the ability of SVF to form new vessels and integrate with nearby host vasculature.6,31,32 Questions regarding how cell assembly dynamics and contributions of new vessel formation effect angiogenesis motivate the need to visualize SVF during these processes.

This study presents the rat mesentery culture model as a tool for visualizing SVF during microvascular growth in real, intact, multicellular microvascular networks over the time course of a few days. Advantages of the tissue culture model include the ability to view an entire microvascular network, the use of a standard epifluorescent microscope, the ease of adding SVF cells, and the use of multiple tissues per rat. As a thin (20–40 μm), translucent tissue, the mesentery provides an intact tissue ideal for observation at the whole tissue, network, and cellular levels. Observation of DiI and GFP-labeled SVF identified segment formation and structures consisting of a central hub with segments projecting radially. These central aggregates of cells and their projections labeled positively for endothelial and pericyte markers. Important for the utility of the mesentery culture model, the process occurs over several days. SVF-derived hubs interconnect with each other and establish branching capillary network. The characterization of the DiI- and GFP-derived segments as vessels is supported by (1) the formation of similar DiI-positive SVF segments and structures in initially avascular areas, (2) the co-labeling of these structures for lectin and PECAM, and (3) similar evidence of SVF vessel segment formation dynamics observed in vitro.11

Labeling of SVF versus the host microvasculature enabled the visualization of SVF neovasculogenesis. This is important because chronic in vivo cell therapy studies involving transplantation or injection of mesenchymal stem cells or circulating stem cell types have suggested cells incorporate into the existing vasculature at rates of ~0%–10% but do not assemble to form new vessels.26,27,33,34 In comparison, our results show that SVF-derived vessels can cause a dramatic increase in vascular area in a tissue via cell assembly. We speculate that since SVF contains various stem cell populations, the dramatic differences in effects on microvascular growth might be attributed to SVF's mixture of multiple cell types. These differences motivate future studies to (1) compare the advantages between specific stem cell therapy approaches and (2) elucidate the roles of specific sub-cell populations.35

Our results also support the ability of SVF cells to associate with host vessels, though future studies will be needed to quantify the percentage of integration per host vessel type and the percentages of integration of vascular pericytes or endothelial cells. Isolated GFP-positive vessel segments derived from GFP SVF were observed interconnecting with lectin-positive, GFP-negative network regions (data not shown), suggesting that SVF cells can also integrate with host networks as pre-assembled endothelial segments. As support for integration of pericytes, examples of DiI-positive SVF cells were observed wrapping and elongating along lectin-positive vessels in characteristic pericyte locations. Interestingly, SVF cells were not observed on vessels with larger diameters (arterioles and venules) nor lymphatic vessels (data not shown). These findings were made possible by viewing the hierarchy of intact microvascular networks. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the percentages of integration and whether SVF preferably integrates as one cell type or another.

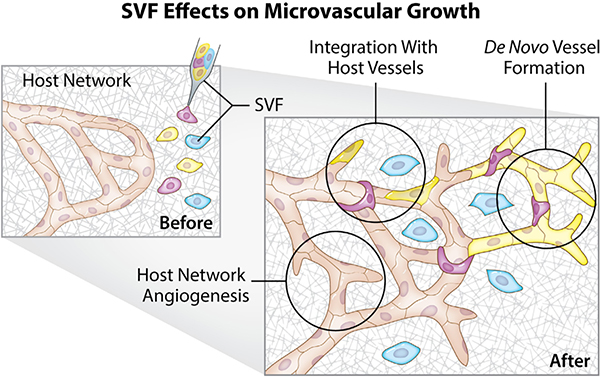

The SVF effects on microvascular growth observed in this study (Figure 6) further emphasize the need to also evaluate the relative contributions of neovascularization, vessel integration, or host network angiogenesis. Comparison of the quantification of SVF presence on vascularized tissue area (Figure 2) and host network vascular area growth (Figure 5) suggests that neovascularization might be the most dramatic contributor to microvascular growth. However, questions regarding the relative dynamics remain. How does, for example, initial microvascular network size or the area of initial avascular regions influence SVF dynamics? Do SVF cells prefer to populate avascular regions? What are the paracrine mechanisms for interstitial residing SVF cells on host network angiogenesis? How far can SVF cells migrate? Our examples of visualizing SVF in the current study provide some information and highlight the utilization of the model for follow-up studies focused on further characterization of cell dynamics.

FIGURE 6.

Summary schematic of observed SVF effects on microvascular network growth using the rat mesentery culture model. On Day 0, before SVF and host network remodeling, SVF cells were transplanted onto cultured tissues. The rat mesentery culture model enabled the viewing of SVF and host network cells over time. Characterization of cell, vessel, and network dynamics during culture supports that SVF can contribute to microvascular growth via (1) de novo vessel formation, (2) integration or association of individual cells along host vessels, and (3) stimulation of host network angiogenesis. SVF, stromal vascular fraction

The scope of this study focused on demonstrating the capability of the rat mesentery culture model for viewing the locations of SVF neovascularization, SVF time-lapse vessel segment assembly, and SVF effects on the host microvasculature. As SVF-related areas of research are still in their early stages, these types of images are highly valuable. Novel findings reported herein show that SVF can assemble into new vessels that fill avascular tissue regions and connect to host networks. In vitro studies have suggested that SVF forms aggregates that develop into a central hub structure from which radial vessel sprouting occurs.11 Our ex vivo results support these initial dynamics and subsequently show that these hubs can interconnect with other nearby hubs, form networks, and connect to the host microvasculature. Consequently, our view of SVF's effect on microvascular growth helps link in vitro observations to an intact microvascular system. The results of the current study motivate follow-up evaluation of SVF-derived vessel functionality, endothelial junctional structure, the size of SVF-derived vessels, and additional microvascular remodeling metrics. Another advantage of the tissue culture model is the presence of lymphatic vessels, immune cells, and nerves.18,21,36 Additional follow-up studies could also include investigation of SVF fate and functional relationships within these systems.

Use of the rat mesentery culture model allows for the incorporation of a variety of methods used to investigate the microvascular dynamics of SVF transplantation. Despite the unique view that the mesentery culture model provides, there are still several challenges associated with this study's characterization of SVF dynamics. DiI labeling is valuable for tracking the original transplanted cells, but it is a membrane marker and, consequently, each new generation of cell has less vibrant labeling making long-term observation difficult. Other limitations are the lack of perfusion and the limited options for transgenic rats. In a recent study, we demonstrated the ability to perfuse the networks in culture, yet future studies are needed to incorporate perfusion with SVF transplantation. Model development can also include the culturing of SVF on mouse mesentery tissue. The mouse mesentery tissue is typically avascular, yet our laboratory has recently demonstrated a method to stimulate vascularization and the feasibility of culturing the tissues analogous to the rat mesentery culture model.37 Future studies using cell-specific lineage or knockout transgenic mice strains could probe the roles of specific SVF cell populations. Future work could also adapt the model to investigate pathological conditions or the influence of aging. For example, whether in rat or mouse, tissues and/or SVF can be harvested from disease strains to evaluate cell versus host tissue effects. Regarding aging, a study by Aird et al. showed that SVF constructs from old donors had reduced perfused vascular networks compared with SVF taken from young donors following 4-week subdermal implantation.38 Utilization of the multiple readouts made possible by the rat mesentery culture model would allow for determination of the specific SVF effects that might be compromised.

5 |. PERSPECTIVES

Stromal vascular fraction transplantation represents a promising microvascular growth platform and advancing our understanding of SVF effects requires the ability to visualize SVF integration during microvascular growth. The challenges associated with dynamically viewing multiple cell types across an intact network motivates the need for models that fill the gap created by in vivo and in vitro limitations. In this study, we demonstrate the ability to visualize SVF de novo vessel formation and integration with a host microvasculature via time-lapse observations of mesenteric tissues in an ex vivo setting.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health under award number R01AG049821 to W.L.M. and award numbers NIH AG053585 and P30ES030283 to A.J.L. The authors want to thank Dr. Christine Schmidt and her Biomimetic Materials & Neural Engineering Lab in the J. Crayton Pruitt Family Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Florida for their generous sharing of the GFP transgenic rats. A special additional thanks goes to Stacey L. Porvasnik and Dr. Nora Hlavac for their help with coordinating the tissue harvesting.

Abbreviations:

- ACK

ammonium-chloride-potassium

- BSI

bandeiraea simplicifolia

- CO2

carbon dioxide

- DPBS

dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline

- EGP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FDA

food and drug administration

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- MEM

minimum essential media

- NaCl

saline

- NG2

nueron-glial antigen

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PECAM

platelet endothelial cell adhesion marker

- PenStrep

penicillin-streptomycin

- SVF

stromal vascular fraction

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zuk PA, Zhu M, Mizuno H, et al. Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 2001;7(2):211–228. doi: 10.1089/107632701300062859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laloze J, Fiévet L, Desmoulière A. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in regenerative medicine: state of play, current clinical trials, and future prospects. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021;10(1):24–48. doi: 10.1089/wound.2020.1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rohrich RJ, Wan D. Making sense of stem cells and fat grafting in plastic surgery: the hype, evidence, and evolving U.S. Food and Drug Administration Regulations. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(2):417e–424e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dongen JA, Harmsen MC, Stevens HP. Isolation of stromal vascular fraction by fractionation of adipose tissue. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1993:91–103. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9473-1_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fodor PB, Paulseth SG. Adipose derived stromal cell (ADSC) injections for pain management of osteoarthritis in the human knee joint. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36(2):229–236. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comella K, Parcero J, Bansal H, et al. Effects of the intramyocardial implantation of stromal vascular fraction in patients with chronic ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):158. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-0918-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qayyum AA, Mathiasen AB, Helqvist S, et al. Autologous adipose-derived stromal cell treatment for patients with refractory angina (MyStromalCell Trial): 3-years follow-up results. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):360. doi: 10.1186/s12967-019-2110-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ntolios P, Manoloudi E, Tzouvelekis A, et al. Longitudinal outcomes of patients enrolled in a phase Ib clinical trial of the adipose-derived stromal cells-stromal vascular fraction in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(6):2084–2089. doi: 10.1111/crj.12777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson A, Hodgson-Garms M, Frith JE, Genever P. Multiplicity of mesenchymal stromal cells: finding the right route to therapy. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1112. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunes SS, Maijub JG, Krishnan L, et al. Generation of a functional liver tissue mimic using adipose stromal vascular fraction cell-derived vasculatures. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2141. doi: 10.1038/srep02141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zakhari JS, Zabonick J, Gettler B, Williams SK. Vasculogenic and angiogenic potential of adipose stromal vascular fraction cell populations in vitro. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2018;54(1):32–40. doi: 10.1007/s11626-017-0213-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelm NQ, Beare JE, Yuan F, et al. Adipose-derived cells improve left ventricular diastolic function and increase microvascular perfusion in advanced age. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0202934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsiao ST, Asgari A, Lokmic Z, et al. Comparative analysis of paracrine factor expression in human adult mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose, and dermal tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(12):2189–2203. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biel NM, Lee JA, Sorg BS, Siemann DW. Limitations of the dorsal skinfold window chamber model in evaluating anti-angiogenic therapy during early phase of angiogenesis. Vasc Cell. 2014;6(17). doi: 10.1186/2045-824X-6-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seynhaeve AL, Ten Hagen TL. High-resolution intravital microscopy of tumor angiogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1464:115–127. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3999-2_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prunier C, Chen N, Ritsma L, Vrisekoop N. Procedures and applications of long-term intravital microscopy. Methods. 2017;128:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maijub JG, Boyd NL, Dale JR, Hoying JB, Morris ME, Williams SK. Concentration-dependent vascularization of adipose stromal vascular fraction cells. Cell Transplant. 2015;24(10):2029–2039. doi: 10.3727/096368914X685401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stapor PC, Azimi MS, Ahsan T, Murfee WL. An angiogenesis model for investigating multicellular interactions across intact microvascular networks. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304(2):H235–H245. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00552.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azimi MS, Motherwell JM, Murfee WL. An ex vivo method for time-lapse imaging of cultured rat mesenteric microvascular networks. J Vis Exp. 2017;(120):55183. doi: 10.3791/55183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azimi MS, Myers L, Lacey M, et al. An ex vivo model for anti-angiogenic drug testing on intact microvascular networks. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0119227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azimi MS, Motherwell JM, Hodges NA, et al. Lymphatic-to-blood vessel transition in adult microvascular networks: a discovery made possible by a top-down approach to biomimetic model development. Microcirculation. 2020;27(2):e12595. doi: 10.1111/micc.12595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motherwell JM, Azimi MS, Spicer K, et al. Evaluation of arteriolar smooth muscle cell function in an ex vivo microvascular network model. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):2195. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02272-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motherwell JM, Anderson CR, Murfee WL. Endothelial cell phenotypes are maintained during angiogenesis in cultured microvascular networks. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5887. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24081-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sweat RS, Sloas DC, Murfee WL. VEGF-C induces lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis in the rat mesentery culture model. Microcirculation. 2014;21(6):532–540. doi: 10.1111/micc.12132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasband WS (1997–2012) ImageJ. U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones VM, Suarez-Martinez AD, Hodges NA, Murfee WL, Llull R, Katz AJ. A clinical perspective on adipose-derived cell therapy for enhancing microvascular health and function: implications and applications for reconstructive surgery. Microcirculation. 2021;28(3):e12672. doi: 10.1111/micc.12672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Azimi MS, Motherwell JM, Dutreil M, et al. A novel tissue culture model for evaluating the effect of aging on stem cell fate in adult microvascular networks. Geroscience. 2020;42(2):515–526. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00178-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koh YJ, Koh BI, Kim H, et al. Stromal vascular fraction from adipose tissue forms profound vascular network through the dynamic re-assembly of blood endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(5):1141–1150. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leblanc AJ, Touroo JS, Hoying JB, Williams SK. Adipose stromal vascular fraction cell construct sustains coronary microvascular function after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302(4):H973–H982. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00735.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karagergou E, Dionyssopoulos A, Karayannopoulou M, et al. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction aids epithelialisation and angiogenesis in an animal model. J Wound Care. 2018;27(10):637–644. doi: 10.12968/jowc.2018.27.10.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu LY, Ma M, Cai JF, et al. Effects of local application of adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction on tendon-bone healing after rotator cuff tear in rabbits. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131(21):2620–2622. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.244120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadi R, Sanaei N, Ahsan S, Masoumi-Verki M, Khadir F, Mokarizadeh A. Stromal vascular fraction combined with silicone rubber chamber improves sciatic nerve regeneration in diabetes. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18(4):212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendel TA, Clabough EB, Kao DS, et al. Pericytes derived from adipose-derived stem cells protect against retinal vasculopathy [published correction appears in PLoS One. 2013;8(9). doi: 10.1371/annotation/679017bf-abd5-44ce-9e20-5e7af1cd3468]. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65691. doi: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cronk SM, Kelly-Goss MR, Ray HC, et al. Adipose-derived stem cells from diabetic mice show impaired vascular stabilization in a murine model of diabetic retinopathy. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4(5):459–467. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2014-0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tracy EP, Steilberg V, Rowe G, et al. State of the field: cellular therapy approaches in microvascular regeneration [published online ahead of print, 2022 Feb 18]. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2022;322:H647–H680. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00674.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodges NA, Barr RW, Murfee WL. The maintenance of adult peripheral adult nerve and microvascular networks in the rat mesentery culture model. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;346:108923. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suarez-Martinez AD, Peirce SM, Isakson BE, et al. Induction of microvascular network growth in the mouse mesentery. Microcirculation. 2018;25(8):e12502. doi: 10.1111/micc.12502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aird AL, Nevitt CD, Christian K, Williams SK, Hoying JB, LeBlanc AJ. Adipose-derived stromal vascular fraction cells isolated from old animals exhibit reduced capacity to support the formation of microvascular networks. Exp Gerontol. 2015;63:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2015.01.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.