Abstract

Our studies of the humoral responses of tuberculosis (TB) patients have defined the repertoire of culture filtrate antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis that are recognized by antibodies from cavitary and noncavitary TB patients and demonstrated that the profile of antigens recognized changes with disease progression (K. Samanich et al., J. Infect. Dis. 178:1534–1538, 1998). We have identified several antigens with strong serodiagnostic potential. In the present study we have evaluated the reactivity of cohorts of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-negative, smear-positive; HIV-negative, smear-negative; and HIV-infected TB patients, with three of the candidate antigens, an 88-kDa protein, antigen (Ag) 85C, and MPT32, and compared the reactivity of the same patient cohort with the 38-kDa antigen and Ag 85A. We have also compared the reactivity of native Ag 85C and MPT32 with their recombinant counterparts. The evaluation of the reactivity was done by a modified enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay described earlier (S. Laal et al., Clin. Diag. Lab. Immunol. 4:49–56, 1997), in which all sera are preadsorbed against Escherichia coli lysates to reduce the levels of cross-reactive antibodies. Our results demonstrate that (i) antigens identified on the basis of their reactivity with TB patients' sera provide high sensitivities for serodiagnosis, (ii) recombinant Ag 85C and MPT32, expressed in E. coli, show reduced reactivity with human TB sera, and (iii) of the panel of antigens tested, the 88-kDa protein is the most promising candidate for serodiagnosis of TB in HIV-infected individuals. Moreover, these results reaffirm that both the extent of the disease and the bacterial load may play a role in determining the antigen profile recognized by antibodies.

Recent estimates by the World Health Organization suggest that approximately 30 million deaths were attributable to tuberculosis in the years 1990 to 1999 (21). A third of the world's population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and about eight million individuals developed clinical tuberculosis last year (21). This global resurgence of tuberculosis has made it imperative that improved vaccines, diagnostics, and drugs be devised to control the current epidemic.

Over 90% of the tuberculosis cases occur in the developing countries, where clinical diagnosis of tuberculosis is based primarily on microscopic examination of smears for acid-fast bacilli and occasionally on chest X-rays. Acid-fast bacillus smears are positive only during advanced tuberculosis, when there are at least 5 × 103 to 6 × 103 bacilli/ml of sputum. Moreover, smear-positive cases constitute only about 50% of pulmonary tuberculosis cases and the sensitivity of the acid-fast bacillus smear ranges from 22 to 78% of culture-proven cases in different studies (13). Culture of bacteria is the “gold standard” for tuberculosis diagnosis, but M. tuberculosis has a long generation time and growth from patient body fluids and subsequent biochemical analysis for species identification requires several weeks. The use of radiometric systems in conjunction with nucleic acid probes has reduced the detection time considerably, but even these procedures require a minimum of 1 week before a definitive laboratory diagnosis can be made (26). Moreover, these techniques are too expensive and technologically complex for widespread application in laboratories in developing countries. Simple diagnostic assays that are rapid, inexpensive, and do not require highly trained personnel or a complex technological infrastructure are essential for global control of tuberculosis (11).

Extensive efforts to devise a sensitive and specific serodiagnostic test for tuberculosis (TB) have been made by researchers at several laboratories (7, 12). The most promising results for serodiagnosis of TB were obtained with the use of the 38-kDa PhoS protein of M. tuberculosis, which provides very high specificity (>98%) (3, 7). However, the sensitivity with this antigen varied from 45 to 80% for different cohorts, and studies have shown that anti-38-kDa protein antibodies are present primarily in patients with advanced, recurrent, and chronic disease (3, 6, 10). Moreover, the 38-kDa antigen was poorly recognized by serum antibodies from HIV-infected TB patients (28). Antigens (Ag) 85A and B have also been studied for development of serodiagnosis, but as was observed for the 38-kDa antigen, antibodies to both these proteins appear primarily in patients with extensive disease (24, 29). Also, Ag 85B is poorly recognized by antibodies from HIV-infected TB patients (18), although Ag 85A has been reported to be recognized by antibodies from some HIV-infected TB patients (30).

Based on 2-dimensional (2-D) fractionation of the culture filtrate proteins of M. tuberculosis grown in vitro in bacteriological medium and immunoblotting with TB patient sera, members of our group, along with others, recently defined the repertoire of antigens recognized by antibodies from TB patients (25). Our studies provided evidence that the profile of culture filtrate antigens recognized by antibodies from TB patients changes during disease progression. Thus, we demonstrated that of the >100 proteins present in the culture filtrates, only ∼26 to 28 proteins were well recognized by patients with advanced cavitary disease who have anti-38-kDa protein antibodies (25). Patients who lack anti-38-kDa protein antibodies showed reactivity with only a subset of the above-mentioned immunogenic culture filtrate proteins. Thus, this subset of antigens can be expected to provide better sensitivities than the 38-kDa protein or other antigens that elicit antibodies only during advanced disease. Four of the proteins in this subset that are potential candidates for devising serodiagnosis for TB could be identified: Ag 85C, MPT32, an 88-kDa protein, and MPT51 (25).

Our observation that the profile of antigens recognized by patient antibodies is influenced by the stage of tuberculosis (17, 25) and the information that antibody responses to the 38-kDa antigen vary in different cohorts (5, 6) suggested that valid comparisons of potential serodiagnostic antigens can be made only if the same cohort is used for assessment of the different candidate antigens under study. In the present study, we report the reactivity of a cohort of 54 HIV-negative TB patients with three culture filtrate antigens, Ag 85C, MPT32, and an 88 kDa protein, which were previously identified to be strongly seroreactive (25). The reactivity of the same patient cohort with two antigens previously proposed as candidates for serodiagnosis for TB, the 38-kDa antigen and Ag 85A, was assessed for comparative purposes (7, 9). The same cohort was also evaluated for reactivity with two of these antigens expressed as recombinant proteins (Ag 85C and MPT32). We also report the reactivity of serum samples from 51 HIV-positive TB patients with four of the same antigens (Ag 85C, MPT32, and the 88-kDa and 38-kDa proteins).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

The individuals from whom serum samples were obtained for this study belonged to the following groups (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinical details of subjects tested

| Infection status of subjects (n) | No. of patientsa

|

Total no. of serum samples | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smear positive

|

Smear negative | |||

| Cavitary | Noncavitary | |||

| HIV negative, TB positive, PPD skin test result unknown (54) | 34 | 8 | 12 | 54 |

| HIV positive, pre-TB, PPD skin test result unknown (42)b | NA | NA | NA | 71 |

| HIV positive, TB-positive, PPD skin test result unknown (37)b | 4 | 17 | 16 | 37 |

| HIV negative, TB negative, PPD skin test positive (30) | NA | NA | NA | 30 |

| HIV negative, TB negative, PPD skin test negative (19) | NA | NA | NA | 19 |

| HIV positive, TB negative, PPD skin test result unknown (34) | NA | NA | NA | 34 |

All smear-negative patients were noncavitary. NA, not applicable.

28 patients are included in both groups.

(i) HIV-negative TB patients.

A total of 54 HIV-negative, culture-positive TB patients were included in this group. Of these, 42 patients were sputum smear positive for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), and 12 patients were sputum smear negative. Thirty-four of the 42 smear-positive patients had cavitary lesions, whereas the remaining 8 smear-positive patients were noncavitary. All 12 smear-negative TB patients lacked any evidence of cavitation.

(ii) HIV-positive TB patients.

This cohort of 51 HIV-positive TB patients is derived primarily from HIV-positive individuals who were being routinely monitored for their CD4 counts and developed TB during the course of HIV disease progression (16). As a result, multiple serum samples, obtained prior to clinical manifestation of tuberculosis (pre-TB) were available from several individuals, and are referred to herein as pre-TB serum samples. A total of 108 serum samples, of which 71 were obtained pre-TB and 37 were obtained at the time of clinical presentation with TB (at-TB) were tested in this study. For 28 patients, both pre-TB and at-TB serum samples were available.

Of the 37 HIV-positive TB patients for whom serum samples obtained at-TB were tested, 21 were AFB smear positive. However, in contrast to the HIV-negative, smear-positive TB patients, only 4 of 21 HIV-positive, smear-positive TB patients had cavitary disease. The remaining 17 smear-positive patients either showed signs of infiltration or no radiological changes upon chest X-ray. Sixteen HIV-positive TB patients were sputum smear negative, and none of them showed any evidence of cavitary disease.

TB-negative controls.

The control populations included (i) 30 HIV-negative, TB-negative, purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test-positive, healthy individuals, 16 of whom were immigrants from countries where Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination is given at birth; (ii) 19 HIV-negative, TB-negative, PPD skin test-negative healthy individuals; and (iii) 34 HIV-positive, TB-negative, asymptomatic individuals with CD4 cell counts of >800/ml whose PPD reactivity was unknown.

Antigens.

The details of the purification procedures used for obtaining purified Ag 85A and C have been described earlier (1). Briefly, late-log-phase culture filtrate proteins of M. tuberculosis grown in glycerol-alanine salts (GAS) medium were precipitated with a saturated 40% (NH4)SO4 solution. The precipitated material was dialyzed against buffer containing 10 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM ditheothreitol (DTT), and 1 mM EDTA and applied to a phenyl-Sepharose column (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The individual proteins of Ag 85 complex proteins were eluted using buffer A containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.6), 1 mM DTT, and 1 mM EDTA, followed by a linear gradient composed of 100% of buffer A to 100% of buffer A containing 50% ethylene glycol.

To obtain purified native MPT32 glycoprotein, the concentrated culture filtrate of M. tuberculosis was dried and resuspended in loading buffer (50 mM KH2PO4 [pH 5.7], 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MnCl2, and 1 mM DTT) and applied to a column packed with Sepharose 4B conjugated to concanavalin A (Sigma). Nonmannosylated products were eluted with 3 column volumes of the loading buffer, and the retained mannosylated products, including MPT32, were eluted with loading buffer containing 1 M methyl-α-mannopyranoside. The glycosylated proteins were precipitated with a 80% saturated (NH4)2SO4 solution suspended in 50 mM NaHPO4 (pH 7.0)–500 mM (NH4)2SO4–1 mM DTT and dialyzed against the same solution. This suspension was applied to a phenyl-Sepharose column and MPT32 was eluted with a linear gradient of 500 to 0 mM (NH4)2SO4. Fractions containing MPT32 were pooled, concentrated, and rerun over the phenyl-Sepharose column to obtain the purified protein.

The 38-kDa antigen was purified from mid- to late-log-phase culture filtrate as follows: the supernatant from precipitation with 40% saturated (NH4)2SO4 solution was brought to a final concentration of 70% saturated (NH4)2SO4 and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The precipitate, containing the 38-kDa antigen, was suspended in and dialyzed against 10 mM NH4CO3 and lyophilized. This material was dissolved in a solution of 1.6% isopropanol and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), and applied to a 1- by 25-mm diphenyl high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (Vydac, Hesperia, Calif.). Material was eluted from the column with a linear gradient of 98% buffer A (0.1% TFA)–2% buffer B (90% isopropanol, 0.1% TFA) to 15% buffer A–85% buffer B using HPLC system (600E HPLC system; Waters, Milford, Mass.). The pure 38-kDa antigen was eluted with approximately 30% isopropanol.

The preparation of the 88-kDa protein has been described before (17). Briefly, culture filtrate proteins were size fractionated with a preparative sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) system (Prep Cell; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) on a 10% preparative tube gel containing a 6% stacking gel. The running buffer contained 25 mM Tris (pH 8.3), 192 mM glycine, and 0.01% SDS. The proteins were separated by using an increasing wattage gradient and eluted from the bottom of the tube gel with 5 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.8). Individual fractions were assayed by 1-D SDS-PAGE and pooled accordingly. SDS was removed from the concentrated fractions by elution through an Extracti-gel (Pierce) column. The fractions were evaluated for reactivity with pooled sera from cavitary TB patients and PPD skin test-positive healthy controls. The fraction containing the highest-molecular-weight proteins contained the 88-kDa antigen, and this was the only strongly seroreactive antigen in this fraction (16, 17).

Recombinant antigens.

Recombinant Ag 85C and MPT32 were produced in and purified from E. coli. The gene fragment encoding the mature Ag 85C was amplified by PCR using the primers CATATGTTCTCTATAGGCCCGGTCTT (forward) and TCGAGATGGCTGGCTTGCTGGCTC (reverse). The underlined sequence represents an NdeI site. The amplified gene product was ligated into a SmaI site of pBluescript II SK(−) and recovered by digestion with NdeI and SalI. This DNA fragment was ligated into the NdeI-SalI site of the E. coli expression vector pBAce (4) and transformed into E. coli DH5α. The Ag 85C gene was expressed in E. coli using phosphate minimal medium (4). E. coli cells producing the recombinant Ag (rAg 85C) were harvested and lysed by passing through a French press cell. The rAg 85C was purified from the lysate by precipitation with a 60% saturated (NH4)2SO4 solution, followed by solubilization and separation by hydrophobic interaction chromatography using the procedure employed for the native Ag 85C (1).

The gene fragment encoding the mature MPT32 was amplified by PCR using the primers CATATGGATCCGGAGCCAAGCGCCCCCGGT and CTCGAGTCAGGCCGGTAAGGTCCGCTGCGGTGT (forward and reverse, respectively). The underlined sequences indicate the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites for the forward and reverse primer, respectively. The amplified gene product was ligated into the pBluescript II SK(−) and recovered by digestion with NdeI and XhoI. This DNA fragment was ligated into the NdeI-XhoI site of pET23b and the recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3)/pLysS (27). The recombinant gene was expressed via isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) induction for 4 h. The E. coli cells were harvested, lysed, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was precipitated with a 40% saturated solution of (NH4)2SO4. This precipitate was suspended in 50 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.5)–500 mM (NH4)2SO4–1 mM DTT, dialyzed against the same, and applied to a 2.5- by 20-cm phenyl-Sepharose column and eluted with a linear gradient of a decreasing concentration of (NH4)2SO4 (500 to 0 mM). Fractions containing the recombinant MPT32 (rMPT32) were pooled, dialyzed against 10 mM NH4CO3, and lyophilized. This material was suspended in a solution containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, and 0.02% NaN3; applied to a 2.6- by 60-cm Sephacryl S-200 HPLC column (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden), and eluted with the same buffer. A final purification step was performed by preparative SDS-PAGE using a 15% polyacrylamide gel and the Whole Gel Eluter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Electroelution was performed in 10 mM NH4CO3.

ELISA with M. tuberculosis antigens.

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) used was described previously (17). All sera were depleted of cross-reactive antibodies prior to use in any ELISA (17). Briefly, 200 μl of E. coli Y1090 (Promega, Madison, Wis.) lysates (suspended at 500 μg/ml) were used to coat wells of ELISA plates (Immulon 2; Dynex, Chantilly, Va.) and the wells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The serum samples (diluted 1:10 in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]-Tween 20) were exposed to eight cycles of absorption against the E. coli lysates.

Fifty microliters of the individual antigens, suspended at a concentration of 2 μg/ml in coating buffer (except for the purified 38-kDa antigen, which was used at 6 μg/ml), were allowed to bind overnight to wells of ELISA plates. After three washes with PBS, the wells were blocked with 7.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, Utah)–2.5% BSA in PBS for 2.5 h at 37°C. Fifty microliters of each serum sample was added per well at predetermined optimal dilutions (1:50 for Ag 85C and Ag 85A, 1:150 for the MPT32, and 1:200 for both the semipurified 88-kDa antigen and the purified 38-kDa antigen). The antigen-antibody binding was allowed to proceed for 90 min at 37°C. The plates were washed six times with PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%) and 50 μl of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG; Zymed, Calif.), diluted 1:2,000 in PBS-Tween 20, was added per well. After 60 min the plates were washed six times with Tris-buffered saline (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl) and the Gibco BRL Amplification System (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used for development of color. The optical density (OD) at 490 nm was read after the reaction was stopped with 50 μl of 0.3 M H2SO4. The cutoff in all ELISA assays was determined by using the mean OD for the TB-negative control group (PPD skin test-positive; PPD skin test-negative; and HIV-infected, asymptomatic individuals) plus 3 standard deviations (SD).

RESULTS

Reactivity of sera from HIV-negative TB patients with native antigens of M. tuberculosis.

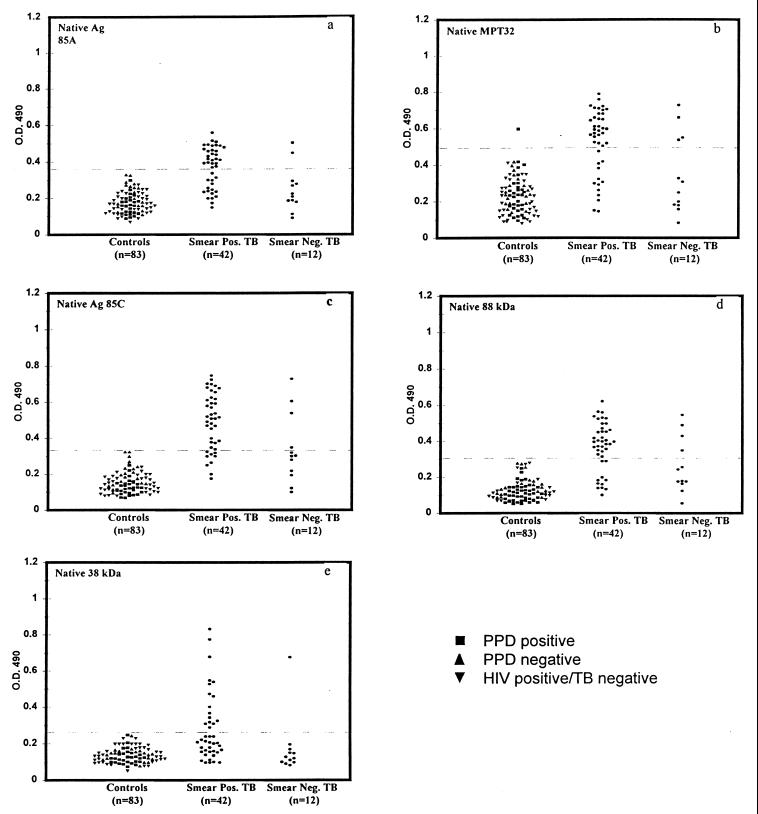

The reactivity of serum samples from 54 HIV-negative TB patients and 83 healthy controls with MPT32, Ag 85C, and the 88-kDa protein was compared to their reactivity with Ag 85A and the 38-kDa protein. Regardless of the PPD skin test status or HIV infection status the three groups of controls (HIV-negative, TB-negative PPD skin test-positive individuals; HIV-negative, TB-negative PPD skin test-negative individuals; and HIV-positive, TB-negative individuals) showed similar reactivity with each of the antigens and were therefore considered as one group for calculating the cutoff (Fig. 1). Except for MPT32, with which 1 out of 83 healthy control serum samples showed reactivity, none of the healthy control serum samples were reactive with any of the antigens, providing specificities ranging from 98 to 100% with each of the antigens (Fig. 1). Of the 42 smear-positive TB patients, serum samples from 69% (29 out of 42) of patients had antibodies to MPT32, serum samples from 79% (33 out of 42) of patients had antibodies to Ag 85C, and serum samples from 74% (31 out of 42) of patients had antibodies to the semipurified 88-kDa antigen. In the same cohort, only 62% (26 out of 42) of the patients had antibodies to the Ag 85A, and 38% (16 out of 42) of the patients had antibodies to the 38-kDa antigen (Fig. 1). Thus, all three of the antigens identified to be seroreactive in TB patients in our previous studies provided higher sensitivities in the smear-positive TB patients (Table 2).

FIG. 1.

Reactivity of sera from HIV-negative, smear-positive, and smear-negative TB patients with native Ag 85A, MPT32, Ag 85C, the 88-kDa antigen, and the 38-kDa antigen.

TABLE 2.

Proportion of specimens from patients and controls containing antibodies to various antigens of M. tuberculosis

| Infection status (n) | % of specimens containing antibodies toa:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native 38-kDa Ag | Native Ag 85A | Native MPT32 | Native Ag 85C | Native 88-kDa Ag | MPT32-, Ag 85C, and 88-kDa Ag | |

| HIV negative, TB positive (smear positive) | 38 (16/42) | 62 (26/42) | 69 (29/42) | 79 (33/42) | 74 (31/42) | 81 |

| HIV negative, TB positive (smear negative) | 8 (1/12) | 17 (2/12) | 33 (4/12) | 33 (4/12) | 33 (4/12) | 50 |

| HIV positive, Pre-TB (42) | 12 (5/42) | NDb | 29 (12/42) | 36 (15/42) | 74 (32/42) | ND |

| HIV positive, at-TB (smear positive) (21) | 14 (3/21) | ND | 24 (5/21) | 19 (4/21) | 66 (14/21) | ND |

| HIV positive, at-TB (smear negative) (16) | 19 (3/16) | ND | 12 (2/16) | 19 (3/16) | 62 (10/16) | ND |

| TB negative (controls) (83) | 0 (0/83) | 0 (0/83) | 2 (1/83) | 0 (0/83) | 0 (0/83) | 2 (1/83) |

| Specificity | 100 | 100 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 98 |

Data in parentheses are the number of specimens containing antibodies to the indicated antigen/the number of specimens tested.

ND, not done.

In the cohort of smear-negative TB patients, 33% (4 out of 12 patients) possessed anti-MPT32, 33% (4 out of 12 patients) had anti-Ag 85C, and 33% (4 out of 12 patients) had anti-88-kDa protein antibodies (Fig. 1). In contrast, only 2 out of 12 (17%) serum samples from the same cohort had antibodies to Ag 85A antigen, and serum from only 1 out of 12 patients (8%) was reactive with the 38-kDa antigen (Table 2).

The additive reactivity of sera with different antigens was computed from the above data (Table 2). For smear-positive patients, the maximum sensitivity of antibody detection (81%) was achieved by combining the reactivity with Ag 85C, the 88-kDa antigen, and MPT32 (Table 2), although this was only slightly higher than the results obtained with Ag 85C or the 88-kDa protein alone. All patients who had circulating antibodies to Ag 85A or to the 38-kDa protein also had antibodies to Ag 85C, MPT32, and/or the 88-kDa protein, and the sensitivity of antibody detection did not increase by taking reactivity with the former antigens into account. However, for the smear-negative patients, the combined reactivity with the MPT32, Ag 85C, or the 88-kDa protein raised the sensitivity to 50% (Table 2). There was no further increase in the sensitivity of antibody detection in the smear-negative patients if reactivity of sera with Ag 85A or the 38-kDa antigen was taken into consideration (Table 2).

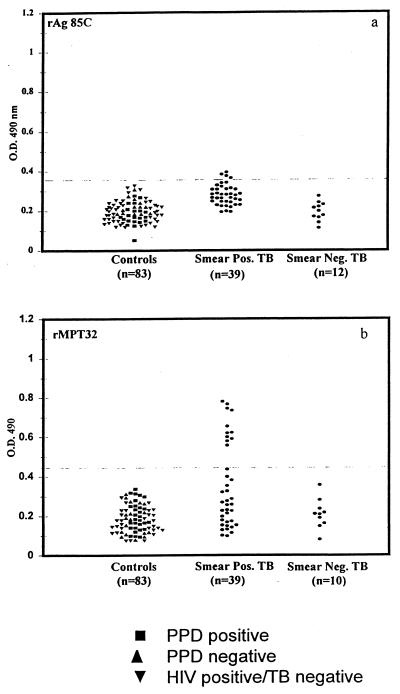

Reactivity of sera from HIV-negative TB patients with recombinant MPT32 and Ag 85C.

In view of the reactivity of native Ag 85C and MPT32 with the TB patient sera, the reactivity of the same sera with the recombinant versions of these antigens was evaluated. Serum samples from 39 out of 42 smear-positive patients and all 12 smear-negative patients were tested for reactivity with the rAg 85C expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2). In contrast to the reactivity observed with native Ag 85C (Fig. 1), serum samples from only 4 out of 39 smear-positive patients and from none of the smear-negative patients showed reactivity with recombinant Ag 85C (Fig. 2). Serum samples from the same 39 smear-positive patients and 10 out of 12 smear-negative patients were also assessed for reactivity with the rMPT32 expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2). Only 11 out of 39 (28%) serum samples from the smear-positive patients showed reactivity with the recombinant MPT32 expressed in E. coli (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Reactivity of sera from TB patients and healthy controls with recombinant Ag 85C and recombinant MPT32.

Reactivity of sera from HIV-positive TB patients with native antigens of M. tuberculosis.

Pre-TB sera from 74% of the HIV-positive TB patients possessed anti-88-kDa protein antibodies (16) (Table 2). Sera from the same cohort were tested for reactivity with MPT32, Ag 85C, and the 38-kDa antigen. In contrast to the results obtained with the 88-kDa antigen, pre-TB sera from only 29% (12 out of 42) of the HIV-positive TB patients had anti-MPT32, 36% (15 out of 42) had anti-Ag 85C, and 12% (5 out of 42) had anti-38-kDa protein antibodies (Table 2).

Members of our group and others have earlier reported that at -TB, ∼65% of the patients have anti-88-kDa protein antibodies (16). When the reactivity of the serum samples from smear-positive and smear-negative patients in this cohort was calculated separately, 66% of the former and 62% of the latter possessed anti-88-kDa protein antibodies (Table 1). In contrast to the results obtained with the 88-kDa antigen, sera from the HIV-positive, smear-positive TB patients showed poor reactivity with MPT32, Ag 85C, and the 38-kDa protein. Moreover, in contrast to the HIV-negative TB patients, the HIV-positive, smear-positive and smear-negative patients showed similar responses (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our earlier studies, in which the immunogenic culture filtrate proteins of M. tuberculosis were mapped, identified several proteins that were predicted to have strong serodiagnostic potential on the basis of their reactivity with sera from patients at different stages of disease progression (25). In the present study, we evaluated the reactivity of three of these antigens, an 88-kDa protein, Ag 85C, and MPT32, with a cohort of smear-positive and smear-negative TB patients in order to compare the antibody assay with the sputum smear test. Our results show that in the HIV-negative, smear-positive TB patients, antibodies to Ag 85C, MPT32, and the 88-kDa antigen are detectable in more than 80% of the patients. This is a significant improvement over the sensitivities obtained for the same cohort with the 38-kDa protein or Ag 85A, both of which were previously shown to be the most successful candidates for developing serodiagnosis for TB (7, 9). In the smear-negative cohort, although antibodies were detectable in only a small proportion of patients with the use of individual antigens, combining the reactivity with all three antigens raised the sensitivity to ∼50%. Although this is significantly lower than the sensitivity in the smear-positive patients, it is higher than sensitivities achieved with any other antigen studied so far and represents an improvement over AFB smear-based diagnosis.

In contrast to the HIV-negative, smear-positive TB patients, sera from the HIV-positive, smear-positive TB patients showed poor reactivity with MPT32, Ag 85C, and the 38-kDa antigen (Table 2). Earlier studies with HIV-positive TB patients have also reported poor reactivity of these patients with the 38-kDa protein (28). Since ∼70% of the same HIV-positive TB patients possess anti-88-kDa protein antibodies, and since the presence or absence of these antibodies did not correlate with either the CD4 numbers or the CD4/CD8 ratios (16), the lower reactivity of HIV-positive TB patient sera with MPT32, the 38-kDa protein, and Ag 85C is probably unrelated to immune dysfunction caused by HIV infection. One obvious difference between the smear-positive, HIV-negative and HIV-positive TB patients was the lack of cavitary lesions in a vast majority of the latter group. It is known that extensive extracellular bacterial replication occurs during growth in cavities, and the expression of antigens like the 38-kDa protein, Ag 85C, and MPT32 by the in vivo bacteria is possibly enhanced in the cavitary environment. This hypothesis is further strengthened by the observation that the anti-88-kDa protein antibodies are present ∼75% of serum samples obtained from HIV-positive TB patients during the pre-TB stages of the disease (16). The presence of anti-88-kDa protein antibodies from sera of patients lacking anti-38-kDa protein antibodies and from pre-TB sera of HIV-positive TB patients, suggests that this protein is expressed in vivo prior to the production of cavitary lesions. Surprisingly, sera from smear-negative HIV-positive TB patients showed better reactivity with the 88-kDa protein than sera from smear-negative, HIV-negative TB patients (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The reasons for this are not clear, but it has been shown that sputum smear-negative, HIV-positive TB patients can have very high levels of bacillary replication in their lungs even in the absence of any cavitary lesions (8). Possibly, the differences in the alveolar bacterial loads between smear-negative HIV-negative TB patients and HIV-positive TB patients may account for the better anti-88-kDa protein responses seen in the latter group of patients.

Although the antigens employed in this study provide significantly greater sensitivities than those achieved with antigens studied by other investigators, even the combined reactivity with all three proteins failed to diagnose ∼20% of the HIV-negative, smear-positive TB patients and ∼50% of the smear-negative patients. Moreover, except for the 88-kDa protein, none of the antigens tested showed significant reactivity with the sera of HIV-positive TB patients. 2-D and 1-D immunoblot analyses of reactivity of culture filtrate proteins with sera of patients at different stages of disease progression show that besides the three antigens tested, there are additional proteins (that are not yet characterized) that are recognized by antibodies from patients in the relatively early stages of the disease (25) and from those with HIV coinfection (16). It is possible that inclusion of one or more additional seroreactive antigens will further enhance the sensitivity of antibody detection, and we are currently involved in identifying and obtaining these antigens. Another possibility is that antibodies in some patients are complexed to free antigen, leading to their occlusion in antibody detection assays. Other investigators have shown that immune complexes are present in the sera of TB patients, although besides the 38-kDa antigen, it has not so far been possible to identify the antigens in these complexes (2, 19, 20). Assays in which the serum immune complexes can be dissociated to release antibodies prior to testing are also being developed.

In parallel experiments using native and recombinant antigens, the results obtained with the recombinant forms of the antigen 85C and the MPT32 are disappointing. Our studies suggest that native mycobacterial proteins possess B-cell epitopes that elicit antibodies during natural infection and are absent from the recombinant versions. Similar problems were encountered when efforts to use recombinant 12-, 16-, and 38-kDa proteins for serological studies were made (31, 32). Differences between the recombinant and native MPT64 in recognition by T cells have also been reported (22). Recent studies have also shown that deglycosylation of MPT32 decreases its capacity to elicit in vivo or in vitro cellular immune responses in guinea pigs (23). Since the recombinant MPT32 used in this study was expressed in E. coli, the poor reactivity of the sera with this protein may be due to the lack of glycosylation. However, Ag 85C was reported not to be glycosylated (14), and the recombinant Ag 85C possesses the same enzymatic activity as the native protein (1). Also, Ag 85C is recognized by human sera after being run on SDS-PAGE gels, suggesting that conformational epitopes are not important for human antibody recognition. The difference in reactivity between native and recombinant Ag 85C is not explained, but given that purification of large quantities of native proteins from M. tuberculosis for production of serodiagnostic tests is difficult and expensive, cloning into mycobacterial hosts with homology to M. tuberculosis may be necessary.

Despite several attempts, success in the development of serodiagnosis for TB has been limited. In most earlier studies, the choice of antigens used was based on the availability, ease of purification, or immunodominance of the antigens in animal models (15). Although further studies are required, the results with the antigens identified in our studies so far provide evidence that use of antigens selected after a rational analysis of the humoral response of human TB patients should enable the design and development of a specific and sensitive serodiagnostic assay for TB. It will also be necessary to ensure that the antigens are able to distinguish between TB and pulmonary infections caused by other pathogens.

The current requirement for three AFB smears to confirm the diagnosis of TB is a major bottleneck in the TB control programs in developing countries. Smear evaluation is time-consuming, requires a sophisticated infrastructure, and contributes to delay in initiation of treatment. In addition, since results cannot be made available immediately, repeated patient visits are required to obtain specimens and provide results (11). These factors contribute to delayed diagnosis and high dropout rates, with subsequent increased spread of infection. The development of antibody or antigen detection assays based on simple and inexpensive formats such as dipstick assays or flow-through cassettes that are easy to interpret are urgently required. Such assays, which would permit on-the-spot rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis in the absence of laboratory infrastructure, would make a significant contribution to early treatment and control the spread of TB, especially in the developing countries.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sources of support were the Research Center for AIDS and HIV Infection, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and NIH AI36984. The work performed at CSU was supported by contract no. AI-75320 provided by the NIH (NIAID).

REFERENCES

- 1.Belisle J T, Vissa V D, Sievert T, Takaama K, Brennan P J, Besra G S. Role of the major antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cell wall biogenesis. Science. 1997;276:1420–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharya A, Ranadive S N, Kale M, Bhattacharya S. Antibody-based enzyme linked immunosorbent assay for determination of immune complexes in clinical tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:205–209. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.2.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bothamley G H, Rudd R, Festenstein F, Ivanyi J. Clinical value of the measurement of Mycobacterium tuberculosis specific antibody in pulmonary tuberculosis. Thorax. 1992;47:270–275. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.4.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Craig S P, III, Yuan L, Kuntz D A, McKerrow J H, Wang C C. High level expression in Escherichia coli of soluble, enzymatically active schistosomal hypoxanthine/guanine phosphoribosyltransferase and trypanosomal ornithine decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2500–2504. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel T M, de Murillo G L, Sawyer J A, Griffin A M, Pinto E, Debanne S M, Espinosa P, Cespedes E. Field evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for the serodiagnosis of tuberculosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:662–665. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel T M, Debanne S M. The serodiagnosis of tuberculosis and other mycobacterial diseases by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:1137–1151. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.5.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daniels T M. Immunodiagnosis of tuberculosis. In: Rom W R, Garay S, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown, and Company, Inc.; 1996. pp. 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiPerri G, Cazzadori A, Vento S, Malena M, Bontempini L, Lanzafame M, Allegranzi B, Concia E. Comparative histopathological study of pulmonary tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected and non-infected patients. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1996;77:244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drowart L, Huygen K, De Bruyn J, Yernault J C, Farber C M, Van Vooren J P. Antibody levels to whole culture filtrate antigens and to purified P32 during treatment of smear-positive tuberculosis. Chest. 1991;100:685–687. doi: 10.1378/chest.100.3.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espitia C, Cervera I, Gonzalez R, Mancilla R. A 38-kD Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen associated with infection. Its isolation and serological evaluation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;77:373–377. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foulds J, O'Brien R. New tools for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: the perspective of developing countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:778–783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grange J M. The humoral immune response in tuberculosis: its nature, biological role and diagnostic usefulness. Adv Tuberc Res. 1984;21:1–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Group M R C C E. National survey of notifications of tuberculosis in England and Wales in 1998. Thorax. 1992;47:770–775. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.10.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harth G, Lee B-Y, Wang J, Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Novel insights into the genetics, biochemistry, and immunocytochemistry of the 30-kilodalton major extracellular protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3038–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3038-3047.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laal S. Humoral responses to M. tuberculosis. In: Rom W R, Garay S, editors. Tuberculosis. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown, and Company, Inc.; 1994. pp. 335–342. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laal S, Samanich K M, Sonnenberg M G, Belisle J T, O'Leary J, Simberkoff M S, Zolla-Pazner S. Surrogate marker of preclinical tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus infection: antibodies to an 88 kDa secreted antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:133–143. doi: 10.1086/514015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laal S, Samanich K M, Sonnenberg M G, Zolla-Pazner S, Phadtare J M, Belisle J T. Human humoral responses to antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: immunodominance of high molecular weight antigens. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1996;4:49–56. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.1.49-56.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McDonough J A, Sada E D, Sippola A A, Ferguson L E, Daniel T M. Microplate and dot immunoassays for the serodiagnosis of tuberculosis. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:318–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radhakrishnan V V, Mathai A, Sundaram P. Diagnostic significance of circulating immune complexes in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:128–131. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-2-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raja A, Narayanan P R, Mathew R, Prabhakar R. Characterization of mycobacterial antigens and antibodies in circulating immune complexes from primary tuberculosis. Lab Clin Med. 1995;5:581–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raviglione M C, Snider D E, Kochi A. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis: Morbidity and mortality of a worldwide epidemic. JAMA. 1995;273:220–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roche P W, Winter N, Triccas J A, Feng C G, Britton W J. Expression of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MPT64 in recombinant Mycobacterium smegmatis: purification, immunogenicity and application of skin tests for tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:226–232. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romain F, Horn C, Pescher P, Namane A, Riviere M, Puzo G, Barzu O, Marchal G. Deglycosylation of the 45/47-kilodalton antigen complex of Mycobacterium tuberculosis decreases its capacity to elicit in vivo or in vitro cellular immune responses. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5567–5572. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5567-5572.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sada E, Ferguson L E, Daniel T M. An ELISA for the serodiagnosis of tuberculosis using a 30,000-Da native antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:928–931. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.4.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samanich K M, Belisle J T, Sonnenberg M G, Keen M A, Zolla-Pazner S, Laal S. Delineation of human antibody responses to culture filtrate antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1534–1538. doi: 10.1086/314438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stager C E, Libonati J P, Siddiqi S H, Davis J R, Hooper N M, Baker J F, Carter M E. Role of solid media when used in conjunction with the BACTEC system for mycobacterial isolation and identification. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:154–157. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.154-157.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Studier F W, Rosenberg A H, Dunn J J, Dubendorff J W. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:60–89. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85008-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thybo S, Richter C, Wachmann H, Maselle S Y, Mwakyusa D H, Mtoni I, Anderson A B. Humoral response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific antigens in African tuberculosis patients with high prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Tuberc Lung Dis. 1995;76:149–155. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(95)90558-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Vooren J P, Drowart A, de Cock M, van Onckelen A, H D H M, Yernault J C, Valcke C, Huygen K. Humoral immune response of tuberculous patients against the three components of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG 85 complex separated by isoelectric focusing. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2348–2350. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.10.2348-2350.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Vooren P, Farber C M, Motte S, Debruyn J, Legros F, Yernault J C. Assay of specific antibody response to mycobacterial antigen for the diagnosis of a pleural effusion in a patient with AIDS. Tubercle. 1988;69:303–305. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(88)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verbon A. Development of a serological test for tuberculosis. Trop Geo Med. 1994;46:275–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verbon A, Hartskeerl R A, Moreno C, Kolk A H J. Characterization of B cell epitopes on the 16 K antigen of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]