Abstract

Two classes of low-affinity receptors for the Fc region of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (FcγR) are constitutively expressed on resting human neutrophils. These receptors, termed FcγRIIa (CD32) and FcγRIIIb (CD16), display biallelic polymorphisms which have functional consequences with respect to binding and/or ingestion of targets opsonized by human IgG subclass antibodies. The H131-R131 polymorphism of CD32 influences binding of human IgG2 and, to a lesser extent, human IgG3 to neutrophils. The neutrophil antigen (NA1-NA2) polymorphism of CD16 influences the efficiency of phagocytosis of bacteria opsonized by human IgG1 and IgG3. These polymorphisms may influence host susceptibility to certain infectious and/or autoimmune diseases, prompting interest in the development of facile methods for determination of CD32 and CD16 genotype in various clinical settings. We previously reported that genomic DNA from saliva is a suitable alternative to DNA from blood in PCR-based analyses of CD32 and CD16 polymorphisms. In the present study, we utilized for the first time this salivary DNA-based methodology to define CD32 and CD16 genotypes in 271 Caucasian and 118 African-American subjects and to investigate possible linkage disequilibrium between certain CD32 and CD16 genotypes in these two ethnic groups. H131 and R131 gene frequencies were 0.45 and 0.55, respectively, among Caucasians and 0.59 among African-Americans. NA1 and NA2 gene frequencies were 0.38 and 0.62 among Caucasians and 0.39 and 0.61 among African-Americans. Since FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb synergize in triggering neutrophils, we also assessed the frequency of different CD32 and CD16 genotype combinations in these two groups. In both groups, the R/R131-NA2/NA2 genotype combination was more common than the H/H131-NA1/NA1 combination (threefold for Caucasians versus sevenfold for African-Americans). Whether individuals with the combined R/R131-NA2/NA2 genotype are at greater risk for development of infectious and/or autoimmune diseases requires further investigation, which can be conveniently performed using DNA from saliva rather than blood.

Membrane receptors for the Fc region of immunoglobulin G (IgG) (FcγR) provide an important link between the humoral and cellular elements of the immune system. Three main classes of leukocyte FcγR are currently recognized, including FcγRI (CD64), FcγRII (CD32), and FcγRIII (CD16). FcγRI is a high-affinity receptor capable of binding human IgG1, IgG3, and IgG4 in monomeric form. FcγRII and FcγRIII, on the other hand, are low-affinity receptors which bind IgG1 and IgG3 in complexed or aggregated form. Among FcγR, only the FcγRII class is capable of binding human IgG2 efficiently (41).

Each class of FcγR is encoded by multiple genes, all of which are located on the long arm of chromosome 1 (26). In addition, alternative RNA splicing results in the generation of multiple transcripts, including soluble and membrane-bound receptor forms. Circulating neutrophils, a key element of host defense against acute bacterial infection, constitutively express FcγRIIa, a 40-kDa integral membrane glycoprotein, as well as FcγRIIIb, a 50- to 80-kDa phosphatidylinositol-linked glycoprotein, the latter of which is numerically predominant on these cells (9, 17). Both of these receptors display genetically defined structural polymorphisms which affect phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets.

A biallelic polymorphism in the A gene encoding FcγRII results in the generation of two distinct allotypes whose structures differ at amino acid residues 27 and 131. Only the amino acid substitution at position 131 significantly affects the ligand binding affinity and specificity of FcγRIIa. The allotype containing histidine at position 131 (H131) binds human IgG2 efficiently, whereas the allotype containing arginine (R131) at this same position does not (3, 24, 32, 36, 45). FcγRIIa-H131 also binds human IgG3 more efficiently than does FcγRIIa-R131 (5, 24).

A second polymorphism, involving FcγRIIIB, is responsible for the biallelic neutrophil-specific antigen (NA1 and NA2) system (15). The NA1 and NA2 allotypes of FcγRIIIB differ by five nucleotides and four amino acids, with NA2 containing two additional N-linked glycosylation sites. These differences have been shown to influence the capacity of FcγRIIIB to interact with human IgG. Hence, neutrophils from individuals who are homozygous for the NA1 allele display greater phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets than do neutrophils from NA2-homozygous donors (30, 32). Both IgG1 and IgG3 antibodies appear to react more readily with the NA1 allotype than with the NA2 allotype (5).

Recent evidence suggests that certain FcγRIIA and/or FcγRIIIB allotypes may contribute to increased susceptibility to certain infectious or autoimmune diseases (4, 11, 34, 35). This has spawned interest in the development of rapid methods for determining FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotypes in various clinical settings. The majority of techniques reported to date have employed genomic DNA from peripheral blood in the performance of such analyses. We recently reported that DNA isolated from saliva is a satisfactory alternative to DNA from blood in PCR-based analyses of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotype (43). To date, however, neither we nor other groups have employed salivary DNA to define CD32 and/or CD16 genotype in various ethnic groups. Hence, the focus of the present study was to employ salivary DNA to determine the distribution of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotypes in a large population of Caucasian and African-American subjects. Moreover, inasmuch as FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB can function synergistically in triggering neutrophil responses (10, 31, 33, 40, 44), we considered the possibility that certain genotype combinations may be less favorable than others in supporting IgG-mediated neutrophil responses. Accordingly, we also compared the frequencies of different FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotype combinations in our Caucasian and African-American populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

Whole-saliva samples were obtained from 118 unrelated African-American (43 male, 75 female) and 271 Caucasian (132 male, 139 female) adult subjects using a collection method described previously (43). All participants were randomly recruited, nonweighted volunteers, selected without regard to oral or general health status. Seventy-eight of the African-American samples were generously provided by Jonathan Korostoff, University of Pennsylvania, again without regard to health status. Informed written consent was obtained from each donor prior to sample acquisition. Caucasian and African-American subjects participating in this study confirmed (by self-reporting) that all four of their grandparents were of Caucasian and African-American descent, respectively. The saliva specimens were either stored at 4°C and DNA extracted within 2 h of isolation or stored at −70°C until processed.

Isolation of DNA from saliva.

DNA was isolated from saliva using a commercial DNA purification kit (QIAamp blood kit; Qiagen, Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) as described in detail elsewhere (43). We previously reported that salivary DNA was a suitable alternative to DNA from peripheral venous blood as a template for PCR-based analysis of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotype, with genotype results being completely concordant when using either source of DNA. Moreover, FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotype results were concordant with phenotype results obtained by flow cytometric analysis.

Determination of FcγRIIA genotype.

FcγRIIA genotype analysis was performed by means of a nested-PCR technique. Briefly, a 1-kb FcγRIIA gene-specific fragment containing the G/A polymorphism at nucleotide 494 was initially amplified by PCR using sense (P63) and antisense (P52) primers described previously (43). This initial PCR was performed in a Perkin-Elmer thermal cycler (Model 2400; Foster City, Calif.) using 45 ng of DNA, 200 μM (each) primer, 1.75 mM MgCl2, and 0.8 U of Expand enzyme (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) in a volume of 30 μl of buffer supplied with the DNA polymerase. The first cycle consisted of 5 min of denaturation at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, and 72°C for 1 min. In the final cycle, extension time was increased to 7 min at 72°C. Following completion of the first PCR, 17 μl was removed and electrophoresed in 2% agarose to confirm the presence of the expected 1-kb product.

The remaining product from the first PCR was divided into two parts and employed in a second-step PCR utilizing primers specific for the H131 or R131 allele. Sense primers used in these two parallel reactions were as follows: P4A (H131 specific), 5′-GAAAATCCCAGAAATTTTTCCA-3′; P5G (R131 specific), 5′-GAAAATCCCAGAAATTTTTCCG-3′. The antisense primer (P13) used in both reactions was as follows: 5′-CTAGCAGCTCACCACTCCTC-3′. Each of the allele-specific PCR assays included 0.6 μl of the first PCR product, 0.5 μM sense (P5G or P4A) and antisense (P13) primer, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and 0.49 U of Expand in a final volume of 18 μl of reaction buffer. The amplification protocol consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles consisting of 95°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s; and then 72°C for 7 min. The products of the H131- and R131-specific PCRs were evaluated in ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gels for the presence of a band at ∼290 bp. Each run included DNA samples from individuals previously genotyped as either H/H131, H/R131, or R/R131.

Determination of FcγRIIIB genotype.

Genotype analysis of the NA1 and NA2 alleles of the FcγRIIIB gene was performed by PCR employing allele-specific sense and antisense oligonucleotide primers as described elsewhere (6, 8), with some modification. The NA1 sense primer (5′-CAGTGGTTTCACAATGTGAA-3′) contained a mismatch at position 4 from the 3′ end in order to prevent mispriming. The sequence of the NA1 antisense primer was as follows: 5′-CATGGACTTCTAGCTGCACCG-3′. The primers were designed in accordance with published sequences (22, 27). NA1-specific PCR assays included 54 ng (sample or genotype controls) of DNA, 200 μM dNTPs, 1.75 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM sense and antisense primer, and 0.49 U of Expand enzyme in a volume of 18 μl of buffer provided with the DNA polymerase. The NA1-specific amplification protocol, which amplifies a 142-bp product, included 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and then 72°C for 7 min to facilitate primer extension. In the NA2-specific PCR, the following sense and antisense primers were employed: 5′-CTCAATGGTACAGCGTGCTT-3′ (sense) and 5′-CTGTACTCTCCACTGTCGTT-3′ (antisense). The NA2-specific PCR assays included 54 ng of template DNA (including genotype controls), 200 μM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 μM sense and antisense primer, and 0.49 U of Expand in a volume of 18 μl. The NA2-specific PCR protocol, which generates a 169-bp product, included 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min; followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, then 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s; and then 72°C for 7 min to promote primer extension. The products of the two allele-specific PCR assays were resolved in a 2.5% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized under UV illumination.

Statistical analyses.

The distributions of FcγRIIA (H/H131, H/R131, R/R131) and FcγRIIIB (NA1/NA1, NA1/NA2, NA2/NA2) genotypes among Caucasian and African-American subjects were compared using the chi-square test (contingency table analysis). Gene frequencies were compared to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium according to the method described by Smith (37).

RESULTS

We previously demonstrated that DNA isolated from whole saliva using a commercially available isolation kit (QIAmp blood kit) is a suitable alternative to DNA isolated from blood when employed as a template for PCR-based analyses of biallelic polymorphisms of CD32 and CD16 (43). In this earlier study, complete concordance was observed between genotype results obtained using salivary DNA and those obtained using blood DNA. Moreover, genotype results were concordant with phenotype results obtained by means of flow cytometry. In the present study, we utilized genomic DNA from saliva to examine the distribution of CD32 and CD16 genotypes, both individually and in combination, from 271 Caucasian and 118 African-American subjects.

Distribution of CD32 and CD16 genotypes in Caucasians and African-Americans.

The distributions of the H131 and R131 alleles of CD32 and the NA1 and NA2 alleles of CD16 among Caucasians and African-Americans are shown in Table 1. Frequencies of the H/H131, H/R131, and R/R131 genotypes among 118 African-Americans were 18.6, 44.9, and 36.4%, respectively. A similar distribution was observed among 271 Caucasian subjects. Despite a slight increase in the frequency of the H/H131 genotype in Caucasians compared with African-Americans (23.6 versus 18.6%, respectively), differences in the distribution of genotypes between the two ethnic groups were not significant (as determined by a chi-square test employing a 3 × 2 contingency table). In each ethnic group, the R/R131 genotype was more common than the H/H131 genotype.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of FcγRIIA (CD32) and FcγRIIIB (CD16) genotypes among Caucasian and African-American subjects

| Subject group | No. of subjects with genotype:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD32b

|

CD16c

|

|||||

| H/H131 | H/R131 | R/R131 | NA1/NA1 | NA1/NA2 | NA2/NA2 | |

| African-Americans (n = 118) | 22 | 53 | 43 | 22 | 48 | 48 |

| % Ta | 18.6 | 44.9 | 36.4 | 18.6 | 40.7 | 40.7 |

| Caucasians (n = 271) | 64 | 115 | 92 | 38 | 129 | 104 |

| % T | 23.6 | 42.4 | 33.9 | 14.0 | 47.6 | 38.4 |

% T, percentage of total subjects of indicated ethnicity.

Distribution of CD32 genotypes did not differ significantly between Caucasian and African-American subjects (χ2 = 1.183, P < 0.5534).

Distribution of CD16 genotypes did not differ significantly between Caucasian and African-American subjects (χ2 = 2.116, P < 0.3471).

We also examined the distribution of CD16 genotypes in these two ethnic groups. Once again, no significant differences were observed (as determined by chi-square test) between Caucasians and African-Americans. In both groups, the NA2/NA2 genotype was >2-fold more common than the NA1/NA1 genotype (40.7 versus 18.6%, respectively, for African-Americans, and 38.4 versus 14.0% for Caucasians).

Several methods have been used to determine the distribution of CD32 and/or CD16 genotypes in various ethnic groups, including Caucasians and African-Americans. These methods included DNA sequence analysis, single-stranded conformational polymorphism, PCR-based analysis using allele-specific oligonucleotide probes, and PCR-based analysis using allele-specific primers (2, 23, 28, 34), in each instance employing genomic DNA obtained from peripheral blood. We compared CD32 and CD16 genotype results, obtained using salivary DNA, with those reported previously using peripheral blood DNA. As indicated in Table 2, reported frequencies of the H131 and R131 genes of CD32 among Caucasian subjects showed little variation. The greatest variation was noted between the results of the present study and those reported by Reilly and coworkers (28). However, in our study the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was not met (P = 0.0206). Modest variation was also noted with respect to gene frequencies of the H131 and R131 alleles reported for subjects of African-American descent. Similar frequencies of the H131 and R131 alleles (0.45 and 0.55, respectively) were reported in a group of 77 subjects of African-American descent (2). For the present study, the African-American group met the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (P = 0.4477).

TABLE 2.

Distribution of FcγRIIA genotypes in Caucasians and African-Americans

| Ethnic group | No. of subjects with FcγRIIA genotype (%):

|

Gene frequency

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H/H131 | H/R131 | R/R131 | H131 | R131 | |

| Caucasians | |||||

| Present study (n = 271) | 64 (23.6) | 115 (42.4) | 92 (33.9) | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| Osborne et al. (23) (n = 35) | 8 (23.0) | 19 (54.0) | 8 (23.0) | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Reilly et al. (28) (n = 47) | 14 (30.0) | 24 (51.0) | 9 (19.0) | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| Botto et al. (2) (n = 259) | 57 (22.0) | 120 (46.3) | 82 (31.7) | 0.45 | 0.55 |

| African-Americans | |||||

| Present study (n = 118) | 22 (18.6) | 53 (44.9) | 43 (36.4) | 0.41 | 0.59 |

| Salmon et al. (34) (n = 100) | 27 (27.0) | 50 (50.0) | 23 (23.0) | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| Reilly et al. (28) (n = 50) | 7 (14.0) | 30 (60.0) | 13 (26.0) | 0.44 | 0.56 |

Reported frequencies of the NA1 and NA2 genes of CD16 among Caucasian subjects exhibited only minor variation (Table 3) among three studies, one of which (6) included a population of German descent. Similar NA1 and NA2 gene frequencies (0.365 and 0.635, respectively) were reported in a Danish population (39). Somewhat greater, albeit modest, variation was observed in the NA1 and NA2 gene frequencies reported herein and those previously reported by Hessner and coworkers with respect to subjects of African-American descent (13). For both the Caucasians (P = 0.8516), and African-Americans (P = 0.1337), the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was met.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of FcγRIIIB genotypes in Caucasians and African-Americans

| Ethnic group | No. of subjects with FcγRIIIB genotype (%):

|

Gene frequency

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NA1/NA1 | NA1/NA2 | NA2/NA2 | NA1 | NA2 | |

| Caucasians | |||||

| Present study (n = 271) | 38 (14.0) | 129 (47.6) | 104 (38.4) | 0.38 | 0.62 |

| Hessner et al. (13) (n = 90) | 10 (11.0) | 46 (51.0) | 34 (38.0) | 0.37 | 0.63 |

| Bux et al. (6) (n = 160) | 19 (11.9) | 73 (45.6) | 68 (42.5) | 0.35 | 0.65 |

| African-Americans | |||||

| Present study (n = 118) | 22 (18.6) | 48 (40.7) | 48 (40.7) | 0.39 | 0.61 |

| Hessner et al. (13) (n = 99) | 16 (16.0) | 30 (30.0) | 53 (54.0) | 0.31 | 0.69 |

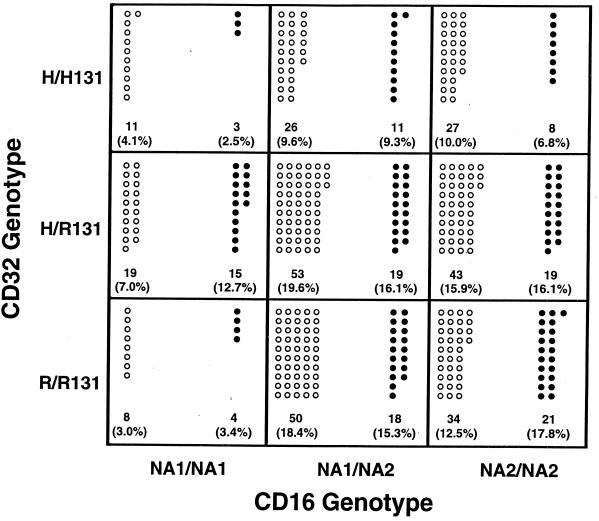

Distribution of combined CD32-CD16 genotypes in Caucasians and African-Americans.

Both CD32 and CD16 play a role in phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized targets by human neutrophils and may act synergistically in promoting neutrophil function. Neutrophils obtained from individuals who are homozygous for the H131 allele of CD32 manifest greater phagocytic activity toward IgG2- and IgG3-opsonized targets than do neutrophils from individuals who are homozygous for the R131 allele. Similarly, neutrophils from donors who are homozygous with respect to the NA1 allele of CD16 display greater phagocytosis of IgG1- and IgG3-opsonized targets than do neutrophils from NA2 homozygous donors. It might be anticipated, therefore, that certain combinations of CD32 and CD16 genotypes may be more favorable than others in supporting phagocytosis of IgG-coated targets. This prompted us to examine the distribution of CD32-CD16 genotype combinations in our Caucasian and African-American populations.

The nine possible combinations of CD32-CD16 genotypes were similarly distributed among Caucasians and African-Americans (Fig. 1). Consistent with the low frequency of the NA1 allele in both ethnic groups (Table 3), few NA1/NA1 homozygous individuals were represented, regardless of CD32 genotype. The majority of NA1 homozygotes identified in each group (68% of African-Americans and 50% of Caucasians) were heterozygous with respect to the H131 and R131 alleles of CD32. Among the least common genotypes found in either ethnic group was the combination of H/H131-NA1/NA1, which is considered the “most favorable” genotype on the basis of functional studies. In contrast, the “least favorable” combination of R/R131-NA2/NA2 was three- to sevenfold more common than the H/H131-NA1/NA1 combination in Caucasians and African-Americans, respectively. No statistically significant associations were found for either Caucasians or African-Americans.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of FcγRIIA (CD32)-FcγRIIIB (CD16) genotype combinations in Caucasian and African-American subjects. Open circles represent Caucasian subjects, while closed circles represent African-American subjects. Numbers in parentheses represent the percentages of subjects of specified ethnic background exhibiting the indicated genotype combination. A 3 × 2 contingency table χ2 test was performed (degrees of freedom = 4) for the two-locus comparison. P values are not corrected for multiple comparisons. Caucasians (n = 271) − χ2 = 4.740; P = 0.3150; African-Americans (n = 118) − χ2 = 6.857; P = 0.1436.

DISCUSSION

Efficient phagocytosis and intracellular killing of bacteria typically require opsonization of the organism by specific IgG antibodies and complement, the former of which are recognized by FcγR expressed on the leukocyte membrane. Allelic polymorphisms of the two classes of low-affinity FcγR constitutively expressed on neutrophils have been shown to influence the ability of these receptors to bind human IgG subclass antibodies. Neutrophils from individuals who are homozygous for the H131 allele of FcγRIIA ingest and kill IgG2-opsonized bacteria more efficiently than do neutrophils from individuals homozygous for the R131 allele (3, 29, 32, 36, 46, 47). It has been suggested that the H131-R131 polymorphism may influence susceptibility to certain types of bacterial infection, particularly those in which IgG2 antibodies are thought to play an important protective role (42, 47). Indeed, FcγRIIA genotype has been reported to be associated with susceptibility to, and severity of, recurrent upper respiratory tract and meningococcal infections (4, 11, 25, 35). FcγRIIA genotype may also be a determinant of susceptibility to certain types of autoimmune disease, notably, systemic lupus erythematosus, at least in some ethnic groups (2, 21, 34, 38).

Functional differences have also been noted with respect to the NA1 and NA2 alleles of FcγRIIIB, particularly as regards phagocytosis of targets opsonized by IgG1 and IgG3 subclass antibodies (5, 30, 32, 33). Neutrophils from NA1-homozygous individuals manifest greater phagocytic activity toward IgG-opsonized targets than do neutrophils from NA2 homozygotes, despite comparable ligand binding. Hence, the NA1-NA2 polymorphism appears to affect phagocytosis of IgG-coated targets via a ligand-independent mechanism (7). The extent to which the NA1-NA2 polymorphism of FcγRIIIB influences susceptibility to infection is unclear. However, a recent report suggests that the NA2/NA2 genotype is associated with a higher rate of disease recurrence in patients with adult periodontitis (18). The NA2 allele also appears to be a risk factor for development of serious gastrointestinal or genitourinary complications in patients with chronic granulomatous disease (12). Finally, in a recent study of patients with multiple sclerosis, Myhr and coworkers (19) observed that patients homozygous for the NA1 allele of FcγRIIIB manifested a more benign course of disease than did patients who were heterozygous or homozygous for the NA2 allele.

Evidence linking allelic polymorphisms of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB with increased susceptibility to infectious and/or autoimmune disease has stimulated interest in the development of methods for determining FcγR genotype in various patient populations. A number of methods for determining either FcγRIIA (16, 23, 28) or FcγRIIIB (6, 13) genotype have been reported, all of which employed DNA isolated from peripheral blood. We recently reported that DNA isolated from whole saliva can be utilized in place of DNA extracted from blood in PCR-based analyses of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB polymorphisms (43). In the present study, we employed salivary DNA to determine FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB genotype in a population of Caucasian and African-American subjects. In both groups, gene frequencies for the H131 and R131 alleles of FcγRIIA, as well as the NA1 and NA2 alleles of FcγRIIIB, were similar to those reported previously (Tables 2 and 3). These results offer further support for the use of salivary DNA in the performance of such analyses.

Recent evidence suggests that FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB may interact synergistically in triggering IgG-mediated neutrophil responses (40). Cross-linking of FcγRIIIB with F(ab′)2 fragments of monoclonal antibody 3G8 (specific for FcγRIIIb) enhances FcγRIIA-mediated phagocytosis (31). Moreover, simultaneously engaging both FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb by means of receptor-specific monoclonal antibodies bound to erythrocytes produces a greater phagocytic response than is seen following ligation of either receptor alone, even when the total number of receptors ligated is equal (10). Conversely, blocking FcγRIIa through pretreatment with monoclonal antibodies results in depression of FcγRIIIb-mediated calcium fluxes, respiratory burst activity, and degranulation (1, 14, 20).

If FcγRIIa and FcγRIIIb cooperate in facilitating neutrophil responses, it might be anticipated that allelic polymorphisms of one or both of these two receptors might influence the outcome of such interactions. In this context, Salmon and coworkers demonstrated that cross-linking FcγRIIIb activates FcγRIIa for phagocytosis but that this effect is greater when employing neutrophils from donors homozygous for the NA1 allele than when using neutrophils from donors homozygous for the NA2 allele (33). Receptor cooperativity was observed even when employing erythrocytes opsonized with human IgG2, which does not bind to FcγRIIIb. These findings raise the possibility that certain combinations of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB alleles may be associated with greater or lesser susceptibility to infections, including those in which IgG2 plays a key protective role. Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been observed that the combination of homozygosity of the R131 allele of FcγRIIA and the NA2 allele of FcγRIIIB is associated with susceptibility to meningococcal infection in patients with terminal complement protein deficiency (11, 25).

The majority of studies performed to date have examined either FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIB genotype in various patient populations. Hence, there is little published information available regarding the frequency of various allelic combinations of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in different ethnic groups. Functional studies characterizing the ability of different FcγR allotypes to bind human IgG subclasses would suggest that the most favorable genotype combination is FcγRIIA-H/H131–FcγRIIIB-NA1/NA1, while the least favorable combination is FcγRIIA-R/R131–FcγRIIIB-NA2/NA2.

In the present study, we examined the distribution of FcγR allelic combinations in our Caucasian and African-American populations (Fig. 1). Given the predominance of the R131 allele of FcγRIIA and the NA2 allele of FcγRIIIB in both ethnic groups of subjects, a relatively small percentage of Caucasians and African-Americans, our finding that few individuals in either group exhibit the “preferred” genotype is not surprising. On the other hand, 12.5% of Caucasians and 17.8% of African-Americans genotyped exhibited the least favorable genotype combination. The reverse situation may apply among Japanese and Chinese subjects, among whom the H131 and NA1 alleles are predominant (18, 48). The significance of the interplay between specific alleles of FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB in defining susceptibility to other infectious or autoimmune diseases has not been established and awaits further investigation. The results of the present study indicate that such genotype analyses can be conveniently performed using DNA isolated from whole saliva, thus avoiding the need to collect peripheral venous blood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the assistance of Paul Creighton (Children's Hospital of Buffalo) and Jonathan Korostoff (University of Pennsylvania) in obtaining saliva specimens from African-American subjects. We also thank Robert Dunford for vital assistance in performing statistical analyses.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant DE10041 (M.E.W.) from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boros P, Odin J A, Muryoi T, Masur S K, Bona C, Unkeless J C. IgM anti-FcgammaR autoantibodies trigger neutrophil degranulation. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1473–1482. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botto M, Theodoridis E, Thompson E M, Beynon H L C, Briggs D, Isenberg D A, Walport M J, Davies K A. FcγRIIa polymorphism in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): no association with disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;104:264–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.33740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredius R G M, de Vries C E E, Troelstra A, van Alphen L, Weening R S, van de Winkel J G J, Out T A. Phagocytosis of Staphylococcus aureus and Haemophilus influenzae type b opsonized with polyclonal human IgG1 and IgG2 antibodies: functional hFcγRIIa polymorphism to IgG2. J Immunol. 1993;151:1463–1472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredius R G M, Derkx B H F, Fijen C A P, de Wit T P M, de Haas M, Weening R S, van de Winkel J G J, Out T A. Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32) polymorphism in fulminant meningococcal septic shock in children. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:848–853. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bredius R G M, Fijen C A P, de Haas M, Kuijper E J, Weening R S, van de Winkel J G J, Out T A. Role of neutrophil FcγRIIa (CD32) and FcγRIIIb (CD16) polymorphic forms in phagocytosis of human IgG1- and IgG3-opsonized bacteria and erythrocytes. Immunology. 1994;83:624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bux J, Stein E L, Santoso S, Muller-Eckhardt C. NA gene frequencies in the German population, determined by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers. Transfusion. 1995;35:54–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35195090663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chuang F Y S, Sassaroli M, Unkeless J C. Convergence of Fcγ receptor IIA and Fcγ receptor IIIB signalling pathways in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2000;164:350–360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.1.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Haas M, Kleijer M, van Zeieten R, Roos D, von dem Borne A E G K. Neutrophil FcγIIIb deficiency, nature and clinical consequences: a study of 21 individuals from 4 families. Blood. 1995;86:2403–2413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Haas M, Vossebeld P J M, von dem Borne A E G K, Roos D. Fcγ receptors of phagocytes. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126:330–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edberg J C, Kimberly R P. Modulation of Fcγ and complement receptor function by the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol-anchored form of FcγRIII. J Immunol. 1994;152:5826–5835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fijen C A P, Bredius R G M, Kuijper E J. Polymorphism of IgG Fc receptors in meningococcal disease. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:636. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_1-199310010-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foster C B, Lehrnbecher T, Mol F, Steinberg S M, Venzon D J, Walsh T J, Noack D, Rae J, Winkelstein J A, Curnutte J T, Chanock S J. Host defense molecule polymorphisms influence the risk for immune-mediated complications in chronic granulomatous disease. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:2146–2155. doi: 10.1172/JCI5084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hessner M J, Curtis B R, Endean D J, Aster R H. Determination of neutrophil antigen gene frequencies in five ethnic groups by polymerase chain reaction with sequence-specific primers. Transfusion. 1996;36:895–899. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.361097017176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huizinga T W, van Kemenade F, Loenderman L, Dolman K M, von dem Borne A E, Tetteroo P A, Roos D. The 40-kDa Fc gamma receptor (FcγRII) on human neutrophils is essential for the IgG-induced respiratory burst and IgG-induced phagocytosis. J Immunol. 1989;142:2365–2369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huizinga T W J, Kleijer M, Tetteroo P A T, Roos D, von dem Borne A E G K. Biallelic neutrophil Na-antigen system is associated with a polymorphism on the phospho-inositol-linked Fcγ receptor III (CD16) Blood. 1990;75:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang X-M, Arepally G, Poncz M, McKenzie S E. Rapid detection of the FcγRIIA-H/R131 ligand-binding polymorphism using an allele-specific restriction enzyme digestion (ASRED) J Immunol Methods. 1996;199:55–59. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(96)00164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimberly R P, Salmon J E, Edberg J C. Receptors for immunoglobulin G. Molecular diversity and implications for disease. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:306–314. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T, Westerdaal N A C, Miyazaki A, van der Pol W-L, Suzuki T, Yoshie H, van de Winkel J G J, Hara K. Relevance of immunoglobulin G Fc receptor polymorphism to recurrence of adult periodontitis in Japanese patients. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3556–3560. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3556-3560.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myhr K-M, Raknes G, Nyland H, Vedeler C. Immunoglobulin G Fc-receptor (FcγR) IIA and IIIB polymorphisms related to disability in MS. Neurology. 1999;52:1771–1776. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.9.1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naziruddin B, Duffy B F, Tucker J, Mohanakumar T. Evidence for cross-regulation of Fc gamma RIIIB (CD16) receptor-mediated signaling by Fc gamma RII (CD32) expressed on polymorphonuclear neutrophils. J Immunol. 1992;149:3702–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norsworthy P, Theodoridis E, Botto M, Athanassiou P, Beynon H, Gordon C, Isenberg D, Walport M J, Davies K A. Overrepresentation of the Fc gamma receptor type IIA R131/R131 genotype in caucasoid systemic lupus erythematosus patients with autoantibodies to C1q and glomerulonephritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1828–1832. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199909)42:9<1828::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ory P A, Clark M R, Kwoh E E, Clarkson S B, Goldstein I M. Sequences of complementary DNAs that encode the NA1 and NA2 forms of Fc receptor III on human neutrophils. J Clin Investig. 1989;84:1688–1691. doi: 10.1172/JCI114350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osborne J M, Chacko G W, Brandt J T, Anderson C L. Ethnic variation in frequency of an allelic polymorphism of human FcγRIIA determined with allele specific oligonucleotide probes. J Immunol Methods. 1994;173:207–217. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)90299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parren P W H I, Warmerdam P A M, Boeije L C M, Arts J, Westerdaal N A C, Vlug A, Capel P J A, Aarden L A, van de Winkel J G J. On the interaction of IgG subclasses with the low affinity FcγRIIa (CD32) on human monocytes, neutrophils and platelets: analysis of a function polymorphism to human IgG2. J Clin Investig. 1992;90:1537–1546. doi: 10.1172/JCI116022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Platonov A E, Shipulin G A, Vershinina I V, Dankert J, van de Winkel J G J, Kuijper E J. Association of human Fc gamma RIIa (CD32) polymorphism with susceptibility to and severity of meningococcal disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:746–750. doi: 10.1086/514935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu W Q, De Bruin D, Brownstein B H, Pearse R, Ravetch J V. Organization of the human and mouse low-affinity FcgammaR genes: duplication and recombination. Science. 1990;248:732–735. doi: 10.1126/science.2139735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravetch J V, Perussia B. Alternative membrane forms of Fc gamma RIII (CD16) on human natural killer cells and neutrophils. Cell type-specific expression of two genes that differ in single nucleotide substitutions. J Exp Med. 1989;170:481–497. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.2.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reilly A F, Norris C F, Surrey S, Bruchak F J, Rappaport E F, Schwartz E, McKenzie S E. Genetic diversity in human Fc receptor II for immunoglobulin G: Fcγ receptor IIA ligand-binding polymorphism. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1:640–644. doi: 10.1128/cdli.1.6.640-644.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez M E, van der Pol W-L, Sanders L A M, van de Winkel J G J. Crucial role of FcγRIIa (CD32) in assessment of functional anti-Streptococcus pneumoniae antibody activity in human sera. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:423–433. doi: 10.1086/314603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salmon J E, Edberg J C, Kimberly R P. Fc gamma receptor III on human neutrophils. Allelic variants have functionally distinct capacities. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:1287–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI114566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salmon J E, Brogle N L, Edberg J C, Kimberly R P. Fcγ receptor III induces actin polymerization in human neutrophils and primes phagocytosis mediated by Fcγ receptor II. J Immunol. 1991;146:997–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salmon J E, Edberg J C, Brogle N L, Kimberly R P. Allelic polymorphisms of human Fc gamma receptor IIA and Fc gamma receptor IIIB. Independent mechanisms for differences in human phagocyte function. J Clin Investig. 1992;89:1274–1281. doi: 10.1172/JCI115712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salmon J E, Millard S S, Brogle N L, Kimberly R P. Fcγ receptor IIIb enhances Fcγ receptor IIa function in an oxidant-dependent and allele-sensitive manner. J Clin Investig. 1995;95:2877–2885. doi: 10.1172/JCI117994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salmon J E, Millard S, Schachter L A, Arnett F C, Ginzler E M, Gourley M F, Ramsey-Goldman R, Peterson M G E, Kimberly R P. FcγRIIA alleles are heritable risk factors for lupus nephritis in African Americans. J Clin Investig. 1996;97:1348–1354. doi: 10.1172/JCI118552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanders L A M, van de Winkel J G J, Rijkers G T, Voorhorst-Ogink M M, de Haas M, Capel P J A, Zegers B J M. Fcγ receptor IIa (CD32) heterogeneity in patients with recurrent bacterial respiratory tract infections. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:854–861. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders L A M, Feldman R G, Voorhorst-Ogink M M, de Haas M, Rijkers G T, Capel P J A, Zegers B J M, van de Winkel J G J. Human immunoglobulin G (IgG) Fc receptor IIA (CD32) polymorphism and IgG2-mediated bacterial phagocytosis by neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1995;63:73–81. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.73-81.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith C A B. A note on testing the Hardy-Weinberg law. Ann Hum Genet. 1970;33:377–381. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song Y W, Han C W, Kang S-W, Baek H-J, Lee E B, Shin C H, Hahn B H, Tsao B P. Abnormal distribution of Fcγ receptor type IIa polymorphisms in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:421–426. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199803)41:3<421::AID-ART7>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffensen R, Gulen T, Varming K, Jersild C. Fc gamma RIIIB polymorphism: evidence that NA1/NA2 and SH are located in two closely linked loci and that the SH allele is linked to the NA1 allele in the Danish population. Transfusion. 1999;39:593–598. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1999.39060593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unkeless J C, Shen Z, Lin C-W, DeBeus E. Function of human FcγRIIA and FcγRIIIB. Semin Immunol. 1995;7:37–44. doi: 10.1016/1044-5323(95)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Pol W L, van de Winkel J G J. IgG receptor polymorphisms: risk factors for disease. Immunogenetics. 1998;48:222–232. doi: 10.1007/s002510050426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Winkel J G J, Capel P J A. Human IgG Fc receptor heterogeneity: molecular aspects and clinical implications. Immunol Today. 1993;14:215–221. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90166-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Schie R C A A, Wilson M E. Saliva: a convenient source of DNA for analysis of bi-allelic polymorphisms of Fcγ receptor IIA (CD32) and Fcγ receptor IIIB (CD16) J Immunol Methods. 1997;208:91–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vossebeld P J, Homburg C H, Roos D, Verhoeven A J. The anti-FcγRIII mAb 3G8 induces neutrophil activation via a cooperative action of FcγRIIIb and FcγRIIa. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:465–473. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warmerdam P A M, van de Winkel J G J, Vlug A, Westerdaal N A C, Capel P J A. A single amino acid in the second Ig-like domain of the human Fcγ receptor II is critical for human IgG2 binding. J Immunol. 1991;147:1338–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson M E, Bronson P M, Hamilton R G. Immunoglobulin G2 antibodies promote neutrophil killing of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1070–1075. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.3.1070-1075.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson M E, Kalmar J R. FcγRIIa (CD32): a potential marker defining susceptibility to localized juvenile periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1996;67:323–331. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.3s.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yap S-N, Phipps M E, Manivasagar M, Bosco J J. Fc gamma receptor IIIB-NA gene frequencies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and healthy individuals of Malay and Chinese ethnicity. Immunol Lett. 1999;68:295–300. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(99)00061-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]