Abstract

The hexanucleotide repeat expansion GGGGCC [r(G4C2)exp] within intron 1 of C9orf72 causes genetically defined amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia, collectively named c9ALS/FTD. , the repeat expansion causes neurodegeneration via deleterious phenotypes stemming from r(G4C2)exp RNA gain- and loss-of-function mechanisms. The r(G4C2)exp RNA folds into both a hairpin structure with repeating 1 × 1 nucleotide GG internal loops and a G-quadruplex structure. Here, we report the identification of a small molecule (CB253) that selectively binds the hairpin form of r(G4C2)exp. Interestingly, the small molecule binds to a previously unobserved conformation in which the RNA forms 2 × 2 nucleotide GG internal loops, as revealed by a series of binding and structural studies. NMR and molecular dynamics simulations suggest that the r(G4C2)exp hairpin interconverts between 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 internal loops through the process of strand slippage. We provide experimental evidence that CB253 binding indeed shifts the equilibrium toward the 2 × 2 GG internal loop conformation, inhibiting mechanisms that drive c9ALS/FTD pathobiology, such as repeat-associated non-ATG translation formation of stress granules and defective nucleocytoplasmic transport in various cellular models of c9ALS/FTD.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) represent a spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases with a common genetic cause, a hexanucleotide repeat expansions of GGGCC, or r(G4C2)exp, within intron 1 of chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72). Collectively named c9ALS/FTD, these neurodegenerative diseases are characterized by progressive loss of motor neurons leading to impairment of movement, paralysis, and ultimately death. (1,2) The r(G4C2)exp RNA is the source of two pathological mechanisms: (3,4) (i) sequestration of RNA binding proteins (RBPs) by r(G4C2)exp in foci and (ii) generation of toxic dipeptide repeats (DPRs) via repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation. (5)

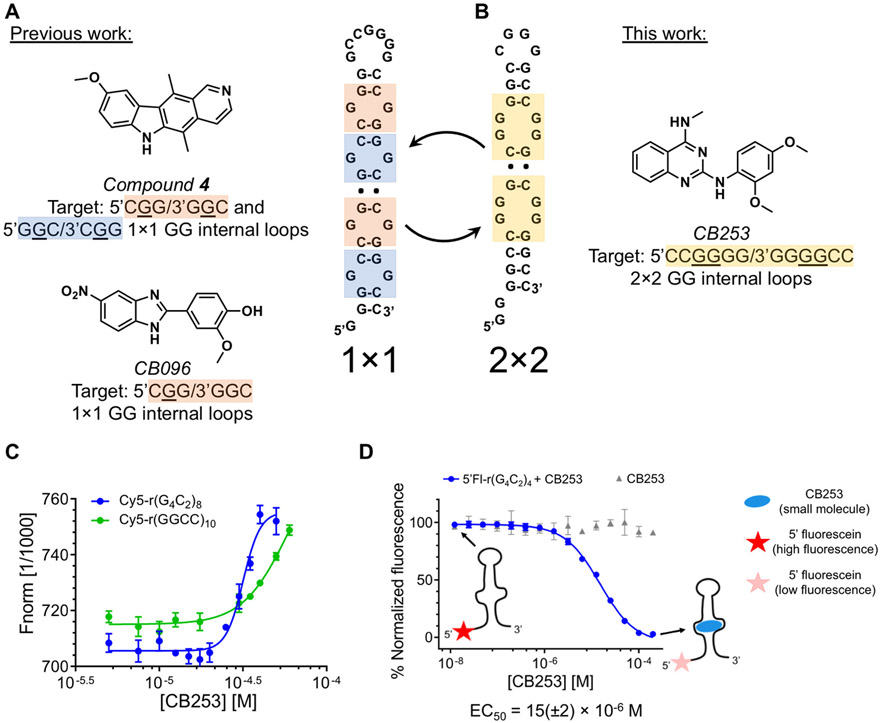

Small molecules that target RNA and affect biology are emerging across a broad spectrum of human diseases. (6-8) Small molecules, (9-12) peptides, (13) and antisense nucleotides (ASOs), (14-16) all with different modes of action, (8,17,18) have been explored in the context of alleviating c9ALS/FTD pathologies. (19) Small molecules recognize well-defined three-dimensional (3D) structural features within an RNA target, which often comprises a dynamic ensemble of interconvertible conformations. (20) The hexanucleotide repeat expansion associated with c9ALS/FTD adopts various structures (21-25) including a hairpin with an array of 1 × 1 GG internal loops (stabilized by Li+ and Na+ ions) (9,11,26) and G-quadruplexes (stabilized by K+ ions). (10,27,28) Interestingly, the hairpin form of r(G4C2)exp displays two different 1 × 1 GG internal loops (Figure 1A,B), 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG (where Gs represent loop nucleotides). As such, these structures have been considered bona fide targets for small molecules. (21) Notably, the hairpin form is a biologically relevant fold that undergoes RAN translation in vitro and in cellulis. (11) Various small molecules have been reported to inhibit RAN translation, including the ellipticine derivative that stabilizes both 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG loops (11) and the benzimidazole CB096 that selectively interacts with 5′CGG/3′GGC (Figure 1A). (29) In addition, small molecules targeting the G-quadruplex form have also been reported. (12) Collectively, these studies suggest that the r(G4C2)exp RNA conformational ensemble (20,30-32) exhibits different structural features that can be stabilized via conformational selection by distinct chemotypes (33)in vitro and in cellulis. (34)

Figure 1.

Identification and validation of CB253, a lead molecule targeting r(G4C2)8 hairpin. (A) Chemical structures of established small molecules that target r(G4C2)exp. Ellipticine-based derivative compound 4 and benzimidazole CB096, selectively bind 1 × 1 GG internal loops, where CB253 targets 2 × 2 GG internal loops (B). (C) CB253 selectively binds the r(G4C2)8 hairpin (EC50 = 30(±4) μM) over the fully base paired r(GGCC)10, as determined by microscale thermophoresis (MST). Data points include the mean values ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. (D) Binding isotherms for CB253 and 5′ Fl-r(G4C2)4, where Fl indicates fluorescein. Data are reported as the mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

Herein, we further explore the ligandability of the r(G4C2)exp hairpin RNA and its conformational ensemble with small molecules. In particular, we report the identification of the 2,4-diaminoquinazoline small molecule CB253 (Figure 1B) that binds a novel structural form of the r(G4C2)exp dynamic ensemble. Various nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and biophysical investigations suggest that CB253 does not interact with 1 × 1 GG internal loops but rather selectively binds 2 × 2 GG internal loops. Experimental 1H and 19F NMR measurements on native and mutant constructs suggest that the r(G4C2)exp hairpin is a bistable RNA, (35,36) with a major population possessing 1 × 1 GG internal loops, and a minor population displaying 2 × 2 GG internal loops. In addition, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on a model G4C2 RNA duplex revealed 2 × 2 GG internal loops to be stable for 8 μs, confirming NMR observation of 2 × 2 GG internal loops as a stable conformation of the dynamic ensemble. Furthermore, these simulations predict that the interconversion between 2 × 2 GG and 1 × 1 GG internal loops occurs via a strand slippage mechanism, which can be exploited by small-molecule interactions. We propose that CB253 binds and stabilizes these 2 × 2 GG internal loops within the r(G4C2)exp ensemble. Finally, we demonstrate the biological relevance of this stabilizing interaction, as CB253 directly engages cellular r(G4C2)exp and selectively rescues various c9ALS/FTD pathological hallmarks in transfected cells and in c9ALS/FTD patient-derived lymphoblastoid cells.

RESULTS

Identification and Validation of CB253 as a r(G4C2)exp Hairpin Binder

We previously reported the identification of small molecules from an RNA-focused library of nitrogen-rich containing heterocycles that specifically bind r(G4C2)8 hairpin via a TO-PRO-1 dye displacement assay. (37) In addition to the previously identified benzimidazole derivative CB096 (29) (Figure 1A), the 2,4-diaminoquinazoline CB253 (Figure 1B) dose dependently displaced TO-PRO-1 from the r(G4C2)8 hairpin. (29) A direct binding assay by microscale thermophoresis (MST) was used to measure CB253′s affinity for 5′-labeled Cy5-r(G4C2)8, yielding an EC50 of 30(±4) μM (Figures 1C and S1A). In contrast, no saturable binding was observed for the fully paired RNA r(GGCCC)10, d(G4C2)8, and triplet repeating RNAs r(CAG)12 and r(CUG)12 (Figures S1B and S2). Collectively, these results indicate that CB253 specifically binds Cy5-r(G4C2)8 hairpins. The binding interaction between CB253 and r(G4C2)4 was further confirmed by biolayer interferometry (BLI), an assay similar to surface plasmon resonance that measures binding kinetics. (38) These studies afforded an on-rate (kon) of ~3 × 104 M−1 × s−1, an off-rate (koff) of ~2.3 × 10−1 s−1, and a Kd of 21(±4) μM (Figure S3A). Steady-state analysis of the BLI data is in good agreement with kinetic analysis and affinities measured by MST, yielding a Kd of 18(±4) μM (Figure S3B).

The binding selectivity of CB253 to the r(G4C2)exp hairpin was further assessed using Fluorescence Recovery by Oligonucleotide Competition (FROC) experiments. FROC measures the fluorescence recovery of a 5′ fluorescein-labeled r(G4C2)4 construct (hereafter 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4) complexed with a small molecule in the presence of a folded competitor RNA oligonucleotide. Dose-dependent addition of CB253 to 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 hairpin triggered saturable quenching of the fluorescein signal yielding an EC50 of 15(±2) μM (Figure 1D), supporting the BLI and MST binding analyses. To determine if the interaction of CB253 with 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 is selective, we measured fluorescence with various competitor RNA oligonucleotides, which would elicit fluorescent recovery if they disrupted the CB253 and 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 complex (Figure S4A). Importantly, fully base-paired RNA oligonucleotide competitors r(GCGC)4, r(GGCC)4, r(AUAU)4, and r(AAUU)4 were inactive in these FROC studies, suggesting that the interaction between CB253 and 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 is specific (Figure S4B). As an additional control, unlabeled r(G4C2)4 and competitor RNAs were mixed and recorded at the EC50 value of CB253 bound to 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 (Figure S4C). CB253 could only be competed off the CB253–5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 complex by the addition of unlabeled r(G4C2)4 hairpin (blue curve), whereas ~20-fold excess of all competitor oligonucleotides did not affect the CB253–5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 complex (note that higher concentrations of RNA competitors interfered with the fluorescence signal of the 5′Fl-r(G4C2)4 free form). In conclusion, these extensive binding and competition results indicate that CB253 specifically interacts with the r(G4C2)exp hairpin.

CB253 Interacts with the r(G4C2)exp Hairpin, as Studied by 1D 1H Imino Proton NMR Spectroscopy

We next studied the binding of CB253 to r(G4C2)8 by 1D imino proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Figure 2). Previous data showed that the resonance at ~12.5 ppm (green circle) corresponds to the imino protons in the closing base pairs of the 5′CGG/3′GGC internal loop within the r(G4C2)8 hairpin. Upon addition of two equivalents of CB253, this initial RNA population underwent slow exchange, triggering the emergence of a new set of imino proton peaks (purple circles) at ~12.1 and 12.0 ppm (for the bound state of the closing GC base pairs), and at 11.4 and 10.0 ppm. Following the addition of six equivalents of CB253, the peak at 12.5 ppm disappeared altogether, suggesting a shift in equilibrium to the CB253 bound form of r(G4C2)8 (Figure 2). Addition of more equivalents of CB253 induced precipitation. These same structural changes were observed for r(G4C2)4 hairpin treated with two equivalents of CB253, suggesting that the repeat size does not affect the small molecule’s binding mode (Figure S5). Further, no change was observed in the 1D NMR spectrum of fully base paired r(GGCC)10 upon the addition of CB253 (Figure S6).

Figure 2.

Binding of CB253 to the r(G4C2)8 hairpin investigated by 1D imino proton NMR spectroscopy. Representative 1D imino proton spectra recorded upon dose-dependent addition of CB253 to the r(G4C2)8 hairpin. Upon addition of two equivalents of CB253, imino proton peaks (purple circles) emerge in slow exchange with the apo r(G4C2)8 hairpin RNA population showcased by green circles. Signal saturation occurs at a 6:1 ratio, indicating the stoichiometry of the complex. 1D NMR spectrum is representative of two independent experiments.

We further explored the stoichiometry of CB253’s interaction with r(G4C2)8 by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. In agreement with NMR studies, saturation was achieved upon addition of six equivalents of compound. The CD spectra suggest at least two binding modes, as evidenced by distinct changes in the spectra that saturate at 260 nm after the addition of 1–3 equivalents of CB253 followed by another significant change in the spectra upon addition of 4–6 equivalents (Figure S7).

CB253 Does Not Target 1 × 1 GG Internal Loops within the r(G4C2)exp Hairpin

Previous studies have shown that the r(G4C2)exp hairpin form consists of 1 × 1 GG internal loops with alternating 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG loops, which feature 5′Gsyn/3′Ganti and/or 5′Ganti/3′Gsyn conformations that exhibit a characteristic 1D imino proton fingerprint at ~11.5 and 10.5 ppm. (9,11,24,39-42) Consequently, small molecules that disrupt the structure of 1 × 1 GG internal loops within r(G4C2)exp hairpins should perturb these unique 1D imino proton peaks.

We previously have shown that model r(G4C2)2 duplexes recapitulate the 1D spectra of r(G4C2)4 and r(G4C2)8 and can allow the identification of a small molecule’s binding site. (29) To precisely determine if 1 × 1 GG internal loop sites within the r(G4C2)exp hairpin are targeted by CB253, two model duplexes were employed featuring either a single 5′CGG/3′GGC (Figure S8A) or 5′GGC/3′CGG (Figure S8B) motif. Surprisingly, no change was observed in the 1D imino spectra of either construct upon dose-dependent addition of CB253 (Figure S8). These results surprisingly suggested that CB253 does not interact with 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG internal loops within model duplexes.

To explore this perplexing result, we measured the binding affinity of CB253 for r(CGG)16, which forms an array of 5′CGG/3′GGC loops, and for r(GGC)16, which forms an array of 5′GGC/3′CGG loops, both of which are also found in r(G4C2)exp (Figure S9A,S9B). No saturable binding was observed in MST studies upon dose-dependent addition of CB253 to either RNA. Further, no changes were observed in the 1D imino proton spectra of either r(GGC)8 or (CGG)8 RNA upon addition of up to 2 equivalents of CB253 (Figure S9C,D). We hypothesized that CB253 must bind and stabilize an alternate conformation within the r(G4C2)exp hairpin unavailable to r(GGC)16 and r(GGC)16, a transient conformation that cannot be detected by conventional 1D/2D NMR methods with RNA alone (31,43-46) but is selectively populated and observable upon addition of the small molecule CB253. (33)

Secondary Structure Prediction Indicates Alternative RNA Folds within the r(G4C2)exp Hairpin Population

To investigate alternative secondary structures available to r(G4C2)8, we employed free-energy minimization using the software RNA structure. (47,48) As expected, the most stable (lowest free energy) structure predicted featured an array of the two 1 × 1 GG internal loops 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG (highlighted in orange and blue, respectively, in Fold 1; Figure 3A). Particularly, the most stable fold (ΔG37 °C° = −30.5 kcal/mol, Figure 3A) has five 1 × 1 GG internal loops and a single 5′CGGG/3′CGG 2 × 1 GG internal loop (highlighted in purple) capped by a CGGG tetraloop. The second most stable fold is predicted to be only 0.1 kcal/mol less stable (ΔG37 °C° = −30.4 kcal/mol; Fold 2; Figure 3A), differing by rearranging the apical 2 × 1 GG internal loop into a 5′CGG/3′GGC 1 × 1 GG internal loop with an extended GCCGGGG hairpin. Intriguingly, two other stable folds were predicted by RNA structure that feature three 2 × 2 GG internal loops (highlighted in yellow; Folds 3 and 4; Figure 3A), ~3 kcal/mol less stable than the lowest free-energy structures (ΔG37 °C° = −29.7 kcal/mol and ΔG37 °C° = −27.0 kcal/mol). Notably, only 1 × 1 GG internal loops, not 2 × 2 loops, were predicted to form in r(CGG)16 and r(GGC)16 (Figure S9), supporting observations from NMR studies (Figure S9C,D). Similar structures were predicted for r(G4C2)4; however, the lowest free-energy structure had 2 × 2 GG internal loops (ΔG37 °C° = −11.3 kcal/mol) rather than 1 × 1 loops (Folds 2 and 3; ΔG37 °C° = −9.9 kcal/mol and ΔG37 °C° = −9.8 kcal/mol, respectively; Figure S10). Interestingly, previous computational (49) and experimental (50) studies have evaluated the thermodynamic properties and stability of 2 × 2 GG noncanonical base pairs within internal loops. Both studies proposed that these 2 × 2 GG internal loops adopt Ganti–Gsyn base pairs that stably stack in the helix.

Figure 3.

Modeling of r(G4C2)8’s structure by free-energy minimization suggests multiple stable conformations. (A) Secondary structures of the four lowest energy folds predicted by free-energy minimization. The lowest free-energy (LFE) structure, Fold 1, comprises five 1 × 1 GG internal loops (highlighted in orange and blue) and a 2 × 1 GG/G asymmetric internal loop (highlighted in purple). Fold 2 features six 1 × 1 GG internal loops (orange and blue) and an extended heptaloop. Folds 3–5 all feature 2 × 2 GG internal loops (highlighted in yellow and green). (B) 1D imino proton spectrum of a model RNA duplex featuring a single 2 × 2 GG internal loop in the presence and absence of CB253. The addition of CB253 triggered the emergence of imino proton peaks highlighted in purple circles. 1D NMR spectrum is representative of two independent experiments. (C) CB253 binds an RNA model that folds into a single structure with three 2 × 2 GG internal loops (highlighted in orange) with an EC50 of 37(±4) μM, as assessed via MST. Data are reported as the mean ± SD and are representative of two independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

CB253 Stabilizes 2 × 2 GG Internal Loops in r(G4C2) Repeat Models

Collectively, our binding studies, NMR data, and secondary structure prediction data suggest that CB253 might bind and stabilize an alternative structure formed by r(G4C2)exp, namely, 2 × 2 GG internal loops (highlighted in yellow; Figure 3A). To determine if this is indeed the case, we studied a model duplex that contains a single 2 × 2 GG internal loop (5′CCGGGG/3′GGGGCC) by NMR spectroscopy, akin to a previous report. (50) Addition of CB253 to the duplex model yielded new imino proton peaks that fully recapitulate the signals detected for the r(G4C2)4 and r(G4C2)8 hairpins, namely, at ~12.1, 12.0, 11.3, and 10.0 ppm (indicated by purple circles in Figure 3B). Further, analysis of 1D imino proton spectra indicated that binding saturation was reached at two equivalents CB253. This 2:1 binding stoichiometry agrees with both NMR and CD spectroscopy studies of r(G4C2)8 and CB253 (Figures 2 and S7). That is, the alternative fold of r(G4C2)8 forms three 2 × 2 GG internal loops; binding of two CB253 molecules per loop affords an expected saturation at six equivalents of small molecule.

To gain additional insight into the structure of the complex formed by CB253 and the 2 × 2 GG internal loop, we acquired and analyzed Nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) spectra. Off-diagonal peaks between the ~11.3 and 9.6 ppm resonances were observed, corresponding to exchangeable protons (NH) that interact with water but can only be observed through stabilizing hydrogen bond interactions within the RNA–small molecule complex (Figure S11). Although these aromatic protons appeared to have interactions with a set of peaks in the aromatic region, there were no interactions with other aromatic or ribose-sugar residues within the RNA structure. They did exhibit strong NOEs to the methyl groups of CB253, as indicated by the 2D NMR spectra recorded in 100% D2O (Figure S11B). The intensity of the peaks in combination with a shorter mixing time (125 ms) suggests that these peaks are intramolecular NOEs (Figure S11C). However, these peaks are not observable in NMR spectra recorded on CB253 in the absence of RNA, implying that the 2 × 2 GG internal loops stabilize a protonated state of CB253, which is essential for binding to the 2 × 2 GG. Due to the dynamic nature of this complex (spectra acquired at 278 K), we were unable to decipher specific atomic interactions between the 2 × 2 GG loop and CB253. However, we can conclude that the complex is stabilized by two hydrogen bonds (H-bonds), as evidenced by the observation of new peaks at ~11.3 and 9.6 ppm upon the addition of CB253. To strengthen these findings, we designed and studied a model r(G4C2) repeat with three 2 × 2 GG loops that are not predicted to convert into 1 × 1 by the addition of an ultrastable GAAA hairpin loop (Figure 3C). The binding of CB253 to this construct via MST yielded an EC50 of 37(±4) μM, in agreement with the EC50 value previously determined for r(G4C2)8 (Figures 3C and S12). In conclusion, CB253 selectively binds 2 × 2 GG internal loops that can form in r(G4C2)exp, through either intrinsic folding into 2 × 2 GG internal loops that are stabilized by CB253 or as a new RNA structure induced by CB253 binding.

r(G4C2)exp Model Duplexes Consist of a Minor 2 × 2 GG Internal Loop Population

To gain insight into whether r(G4C2) repeats interconvert between 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG internal loops or this interconversion is induced by CB253 binding, we employed a simplified r(G4C2)2 duplex model construct previously reported by our group (Figure 4A). (29) The duplex fully recapitulates the 1D imino proton spectra of r(G4C2)4 and r(G4C2)8 hairpins and is predicted to form both 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG internal loops with the same thermodynamic stabilities (ΔG37 °C° = −15.1 kcal/mol) as well as other two folds (Figure 4A). Despite their predicted equivalent thermodynamic stabilities, the two distinct 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG internal loop structures are not observed by 1D imino proton NMR spectroscopy. Instead, we only observe imino resonance peaks for G–C base pairs (Figure S13A). The absence of noncanonical G–G peaks that encapsulate 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG internal loops suggests that this construct is interconverting between both states, as dynamic interconversion between multiple states has been shown to broaden NMR signals beyond detection, known as “NMR intermediate exchange.” (51) These exchange processes prevent traditional 1D imino proton characterization of this construct in the absence of ligand. Regardless, the addition of CB253 to the r(G4C2)2 model duplex still yielded the same 1D imino proton NMR changes observed upon its titration into r(G4C2)4 and r(G4C2)8 (Figure S13A). Notably, the new peaks at ~11.4 and ~10.0 ppm, specific for CB253 in the complex with 2 × 2 GG internal loops, could only be detected at temperatures below 15 °C (Figure S13B).

Figure 4.

CB253 binds 2 × 2 GG internal loops formed by r(G4C2)exp, either by conformational selection or induced fit. (A) Modeling of folds formed by a r(G4C2)2 duplex by free-energy minimization. (B) Monitoring the slow exchange equilibrium between the 1 × 1 GG and 2 × 2 GG internal loop populations by means of replacing cytosine residue at position 6 with 5-fluoro C (5FC) via 1D imino proton and 19F NMR spectroscopy. (C) Addition of CB253 to 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 RNA duplex recapitulates the imino proton peaks specific for the 2 × 2 GG internal loop (purple circles). Saturation of the NMR signal is indicative of the stoichiometry of the complex (2:1 small molecule:RNA). 1D NMR spectrum is representative of two independent experiments. (D) Addition of CB253 to 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 RNA duplex selectively affects the 19F NMR peak at −166.75 ppm (highlighted in purple). Signal saturation indicates a 2:1 CB253:RNA ratio, as observed in C. Each 19F NMR spectrum is representative of two independent experiments.

Since 1D imino proton NMR spectroscopy of the RNA alone suggested dynamic interconversion between 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG internal loop structures, we incorporated modified 19F nucleotides (52,53) such that 19F NMR spectroscopy could be employed. (36,54,55) Using 19F NMR, the interconversion among distinct populations can be monitored and validated using either 5-fluoro cytosine (5FC) and/or 5-fluoro uridine (5FU). (56,57) The 19F nucleus is an excellent NMR atomic reporter, with a comparable size to 1H, easy incorporation in oligonucleotide sequences, commercial availability, and comparable sensitivity to 1H nucleus and to structural rearrangements, (57-59) including in response to external stimuli such as temperature, metal ions, and small molecules. Previous work has validated the use of this atomic reporter to study the interconversion of designed bistable RNAs, where it has been shown to minimally affect both the melting temperature and thermodynamic stability of the RNA ensemble. (54)

Here, we replaced the C6 residue in the r(G4C2)2 duplex, part of the loop closing base pairs whether adopting 1 × 1 GG or 2 × 2 GG internal loops, with 5FC (C6 highlighted in purple in Figure 4B). Before embarking on 19F NMR studies, we first analyzed the effect of 5FC substitution on the RNA’s imino proton spectrum. Only one significant difference was identified, shifting of the N1-H imino proton peak of the paired G upfield by ~0.4 ppm, as previously reported. (29,57) Further, replacement of C by 5FC at position 6 did not alter the binding properties of CB253 to the 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 duplex, as determined by comparing their 1H 1D NMR spectra (Figure 4C).

In the absence of small molecules, two 19F NMR peaks were observed at −166.25 and −166.75 ppm, with a signal intensity ratio of ~70–30%, respectively (Figure 4D). This finding indicates a slow exchange between two distinct conformations in the proximity of 5FC6. These distinct folding states are simultaneously adopted in solution but evade detection in traditional 1D imino experiments due to their interconversion and subsequent exchange with water. The two 19F NMR peaks are not due to H-deuterium (D) isotope exchange (54,57) of the 5FC6 residues as the peaks were not significantly affected upon increasing the D content from 10 to 100% (Figure S14).

To delineate which peak corresponds to the 1 × 1 GG and 2 × 2 GG internal loop-containing population, we studied the effects of previously validated small molecules with defined modes of binding to the hairpin form of r(G4C2)exp. Compound 4, which exclusively stabilizes 5′CGG/3′GGC and 5′GGC/3′CGG 1 × 1 GG internal loops within r(G4C2)exp hairpins, mostly via stacking interactions, (11) exhibited no binding saturation by MST with a 5′ Cy5-labeled construct exclusively featuring 2 × 2 GG internal loops (Figure S15). By NMR spectroscopic analysis, the addition of compound 4 to 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 should stabilize a single 19F NMR peak, corresponding to the 1 × 1 GG internal loop population (Figure S16A). Indeed, the 5FC6 introduction in 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 did not alter the mode of binding of compound 4 by 1D imino proton NMR (Figure S16B). The intensity of the 19F NMR peak at −166.25 ppm is lowered (green dots, Figure S16C) and a new peak emerges at −167.25 ppm, corresponding to 5FC6-r(G4C2)2–compound 4 complex (blue dots, Figure S16C), while the peak at −166.75 ppm did not change (purple dots, Figure S16C). Consequently, the 19F NMR peak at −166.25 ppm was assigned to the 1 × 1 GG internal loop-containing population within 5FC6-r(G4C2)2, the major form present in solution (~70%).

To confirm that CB253 indeed binds to the 2 × 2 GG internal loop, the small molecule was titrated into 5FC6-r(G4C2)2. Indeed, the 19F peak at −166.75 ppm was dramatically sharpened, indicating stabilization also observed in 1D imino proton studies. Further, CB253 shifted the equilibrium between the two conformations, reaching saturation at two equivalent and accounting for ~90% of the population (purple dots, Figure 4D). Additionally, a stepwise disappearance of the −166.25 ppm peak corresponding to the 1 × 1 GG internal loop population was observed (green dots, Figure 4D).

The 19F NMR data presented above suggest significant stabilization of the 5FC6G9/G95FC6 closing base pairs of 5FC6-r(G4C2)2. To assess further if the stabilization of the 2 × 2 GG internal loop-containing population is indeed a result of CB253 treatment and not binding or local rearrangements located at position C6, two additional control experiments were performed. The C5 and C11 within r(G4C2)2 were replaced by 5FCs, yielding 5FC5-r(G4C2)2 and 5FC11-r(G4C2)2, respectively (Figures S17 and S18). Although 5FC5 and 5FC11 form base pairs in both the 1 × 1 and 2 × 2 GG loop conformations, their base-pairing partner and hence its microenvironment changes upon rearrangement. That is, significant changes in the 19F NMR signal should be observed upon the addition of CB253. In agreement, the 19F NMR peaks of 5FC5-r(G4C2)2 and 5FC11-r(G4C2)2 are affected upon addition of CB253, consistent with major conformational rearrangements across the r(G4C2)2 construct (Figures S17 and S18). In conclusion, the 5FC6-r(G4C2)2 model duplex construct suggests that the r(G4C2)2 RNA is bistable, consisting of an equilibrium between a major 1 × 1 and a minor 2 × 2 GG internal loop-containing population at room temperature, which can further be modulated upon addition of CB253.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations of the Strand Slippage within r(G4C2)exp Duplex

To gain a deeper understanding of the conformational landscape experienced by the r(G4C2)2, MD simulations were performed. A model RNA duplex, r(GGGGCCGGGGCC)2, initially having two 2 × 2 GG internal loops, was generated with all four G loop nucleotides in the anti-orientation (Figure 5A). This initial conformation was stable for more than 8 μs, creating a noticeable ensemble. After this point, the dynamic nature of the construct became apparent as the RNA adopted a variety of conformations including base flipping at the terminal sites (Figure 5B) and internal loops (Figure 5C). The first major conformational transformation was observed approximately 9 μs into the simulations: slippage of G1 at one end of the RNA duplex (Figure 5D). Next, a series of transformations occurred in the loop regions where G4:G22 [Strand 1 (5′-GGGGCCGGGGCC-3′): Strand 2 (5′GGGGCCGGGGCC-3′) as indicated in bold] adopted the anti-syn orientation (Figure 5E). After 20 μs, G21 [Strand 1 (5′-GGGGCCGGGGCC-3′): Strand 2 (5′-GGGGCCGGGGCC-3′) as indicated in bold] flipped out, and a second slippage was observed at the other end of the duplex (Figure S19A). As G7 [Strand 1 (5′-GGGGCCGGGGCC-3′) as indicated in bold] flipped out of the helix (Figure S19B), reshuffling of the bases was observed creating a stable state which lasted nearly 2.7 μs. Breathing-out of the backbone then allowed G7 to rotate back inside the helix, resulting in a helix with three 1 × 1 GG internal loops (Figure 5F). Two of these loops, formed by G4:G22 and G10:G16, adopted an anti-syn configuration, while the third formed by G7:G19 adopted an anti-anti configuration (~23 μsec into the simulation). The middle loop, G7:G19, stayed in its initial configuration for more than 10 μs and then switched to syn-anti, creating an RNA helix with three 1 × 1 GG internal loops adopting the anti-syn, syn-anti, and anti-syn orientations, respectively (Figure 5G). Simulations were continued after this point on for more than 65 μs, and no further conformational changes were observed (see Movies S1 and S2). This simulation depicted a mechanism for slippage in a dynamic construct imitating r(G4C2) repeat expansions. In addition, this simulation the stability of 2 × 2 GG loops, as this specific conformation was stable for ~9 μs, suggesting that this structure is adopted by the r(G4C2) RNA as a portion of its dynamic ensemble. This result agreed with previous studies, (60) which revealed that stable, NMR detectable structures within the RNA ensemble can have MD lifetimes of 1 μs.

Figure 5.

Major conformational transitions observed in r(G4C2)2 from MD simulation (t = 65 μs). (A) A model RNA system, r(GGGGCCGGGGCC), which initially contained two 2 × 2 GG internal loops in anti-conformation, was designed to study the transformation from 2 × 2 GG to 1 × 1 GG internal loops. The dynamic nature of this construct produced various conformations including base flipping at the terminal sites (B) and internal loops (C). (D) First major conformational transformation, slippage at one end of the RNA duplex occurred around 10 μs. (E) Next, a series of transformations in the loop regions show G4:G22 adopted the anti-syn orientation. Reshuffling of the bases created slippage at both ends of the RNA helix around 20 μs, resulting in three 1 × 1 GG internal loops (F) in which G4:G22 and G10:G16 adopted the anti-syn configuration, while G7:G19 adopted the anti-anti configuration. (G) Middle loop switched to syn-anti conformation around 33 μs, creating an RNA duplex with three 1 × 1 GG internal loops adopting anti-syn, syn-anti, and anti-syn orientations, respectively. Time stamps are provided below each figure corresponding to conformational transformations observed in the MD trajectory (see Movies S1 and S2).

Strand Slippage Is Sequence Specific

Having confirmed the ability of the r(G4C2)2 model duplex and r(G4C2) repeat hairpins to interconvert between 1 × 1 GG and 2 × 2 GG internal loops, we investigated the generality of the strand slippage process experimentally. First, we tested r(CGGCGG)2 and r(GGCGGC)2 model duplexes, which bear the same nucleotide composition as the r(G4C2)2 model duplex but generate only 1 × 1 GG internal loops, which we observed as stable peaks in the 1D imino proton occurring between 10.5 and 11 ppm (Figure S20). This observation was also confirmed using free-energy minimization (Figure S20). As expected, the addition of CB253 (up to two equivalents) did not affect the 1D imino proton spectra of these duplexes (Figure S20). Next, we studied the potential population interconversion of r(C2G4)2 (duplex; Figure S21), where free-energy minimization indicated various potential folds, including one with a single 2 × 2 GG internal loop (Figure S21A). Upon addition of CB253 to the r(C2G4)2 duplex (Figure S21B), a new set of 1D imino proton peaks appeared akin to studies of the r(G4C2)2 duplex (CG/GC closing base pairs at approximately 12.5, 12.4, 12.3, and 12.2 ppm and 2 × 2 GG noncanonical base pairs at approximately 11.6 and 10.0 ppm; Figures S21C,S21D). Further, using a 5FC7-r(C2G4)2 model duplex, we observed a significant stabilization of the 2 × 2 GG containing population upon addition of CB253 (Figure S22A), from ~23% of the population in the 2 × 2 GG internal loop conformation in the absence of CB253 to ~92% in its presence (Figures S22B,C). Similar results were obtained for the r(C2G4)4 hairpin construct (Figure S23), where CB253 thermally stabilizes the 2 × 2 GG loop by ~10 °C (Figure S24). Unsurprisingly, replacing GC base pairs within the RNA with AU pairs precluded interconversion to the 2 × 2 GG loop and ablated binding of CB253 (Figures S25A,B).

CB253′s Mode of Binding to 2 × 2 GG Internal Loops

Various experiments were performed to elucidate CB253’s binding mode. First, the importance of the substitution pattern within the 2,4-diaminoquinazoline scaffold of CB253 was investigated. The binding of nine broadly substituted quinazolines was investigated via MST, none of which have measurable avidity for the RNA (Figure S26A). These results indicate that the precise 2,4-diamino substitution pattern within CB253’s quinazoline scaffold is key for binding the r(G4C2)8 hairpin RNA. Pharmacophore modeling was performed on all quinazoline derivatives to determine essential features for binding, affording two models that predict activity (Figure S26B,C). Features common to both models include two hydrogen bond donors at the N4 of quinazoline (in DHHR1) and the N2 of quinazoline (in DHHR2), two hydrophobic (methoxy) groups, and one aromatic ring (the aniline ring). However, as CB253 was the only active compound in the current data set, these models require further refinement. Collectively, SAR studies and pharmacophore modeling indicate that the quinazoline chemotype and the 2,4-diamino substitution pattern within CB253 are key for the stabilization of 2 × 2 GG internal loops and hence binding of the r(G4C2)exp.

As the 2 × 2 GG internal loop in r(G4C2)2 is dynamic, we were unable to determine the orientation of the individual guanines in the loop using the native RNA sequence in the presence or absence of CB253. We therefore used site-specific chemical modifications to probe the configuration of the loop nucleotides, in particular replacing G3 with N1-methyl guanosine (m1G), yielding 5′GGm1GGCC/3′CCGm1GGG (Figure S27A) within a model duplex construct. The m1G modification restricts the conformational flexibility of 2 × 2 GG noncanonical base pairs by locking m1G-labeled residues into an syn conformation (Figure S27B). (61) Therefore, the duplex construct is predicted to exclusively feature the 5′m1GsynGanti/3′Ganti m1Gsyn conformation, which was confirmed by a sharp peak at ~10.5 ppm present even at 25 °C (Figure S27C). (Note that, depending on the duplex or hairpin construct, this peak is observed at low temperatures only.) Interestingly, addition of up to two equivalents of CB253 had no effect on the imino proton spectrum (Figure S29C), suggesting either the N1-H of G3 forms a key interaction with CB253 or the small molecule does not interact with 2 × 2 GG loops in the 5′m1GsynGanti/3′Gantim1Gsyn conformation.

RNA-Centric Alleviation of c9ALS/FTD Pathobiology by CB253

The biophysical studies above indicate that CB253 binds selectively to r(G4C2)exp and hence may alleviate c9ALS/FTD-associated pathologies. We first investigated CB253’s ability to inhibit RAN translation in HEK293T cells cotransfected to express (G4C2)66-No ATG-GFP (RNA translation) and ATG-mCherry (canonical translation; used for normalization). (11,29) Notably, no toxicity was observed upon treatment of HEK293T cells with up to 25 μM CB253 (Figure S28A). Indeed, CB253 dose dependently inhibited RAN translation, with ~85% inhibited at the 25 μM dose (Figure 6A). Notably, CB253 did not inhibit the canonical translation of GFP, evaluated by transfecting HEK293T cells with plasmid encoding GFP with an ATG start codon (Figure 6A). RT-qPCR confirmed that the decreased GFP signal was not due to transcriptional inhibition, as GFP mRNA levels were not changed upon CB253 treatment of HEK293T cells (Figure 6B). Moreover, CB253 treatment reduced the abundance of the DPR Poly(GP) in the transfected HEK293T model system as assessed by an electrochemical luminescence sandwich assay (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

CB253 ameliorates various cellular c9ALS/FTD-associated pathologies by directly binding r(G4C2)exp. (A) CB253 inhibits RAN translation (mCherry) of r(G4C2)exp selectively in transfected HEK293T cells. Canonical translation corresponds to ATG-GFP. Data are reported as the mean ± SD of three independent measurements each performed in triplicate. ****p < 0.0001. (B) CB253 does not alter r(G4C2)66 mRNA levels in transfected HEK293T cells. Data are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 3). n.s. indicates not significant as determined by an ordinary one-way ANOVA multiple comparison test. (C) CB253 reduces the levels of the toxic dipeptide repeat poly(GP) upon 24 h incubation in transfected HEK293T cells. Poly(GP) levels were measured using an electrochemiluminescent sandwich immunoassay. Data are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 2 independent experiments, each with two biological replicates). *p < 0.05, as determined by a two-tailed Student’s t-test. (D) ASO-Bind-Map in r(G4C2)66-No ATG-GFP transfected HEK293T cells reveals that CB253 directly engages r(G4C2)exp. Data are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 2 independent experiments, each containing four biological replicates). n.s. = not significant; **p = 0.005 as determined by a two-tailed unpaired t- test with Welch’s correction. (E) HEK293T cells stability expressing Lentiviral-S-tdTomato cotransfected with (G4C2)66-Nluc (disease), SV40-Luc (canonical translation for normalization), and ATG-GFP (imaging control) demonstrate that r(G4C2)66-transfection causes mislocalization of the S-tdTomato marker in the cytoplasm. Additional cells were cotransfected with SV40-Luc and ATG-GFP to control for background mislocalization due to transfection. Treatment of r(G4C2)66-expressing HEK293T cells with CB253 rescue S-tdTomato mislocalization. KPT-335 (“KPT”) inhibits nuclear export and was used as a positive control. The ratio of cytoplasmic:nuclear S-tdTomato signal was quantified from n = 3 biological samples for each treatment group and reported above. ****p < 0.0001, as determined by a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. (F) HEK293T cells stably expressing Lentiviral-S-tdTomato cotransfected with (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc [(G4C2)66-induced stress granules], SV40-Luc, and ATG-GFP or transfected with ATG-GFP and treated with 0.5 mM NaAsO2 [chemically induced stress granules] treated with 25 μM CB253 or vehicle (0.1% DMSO). Ataxin-2 (ATXN2) was imaged by immunohistochemistry as a marker for stress granule formation, and the cells were imaged by confocal microscopy. The number of ATXN-2-positive stress granules per nucleus was quantified from n = 3 biological replicates per treatment group. ****p < 0.0001, as determined by an unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction. (G) CB253 dose dependently lowers the toxic dipeptide repeat poly(GP) levels in a patient-derived lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL). Poly(GP) levels were measured by an electroluminescent sandwich immunoassay. Data are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 3 biological replicates). **p < 0.05, as determined by a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons.

Direct binding of r(G4C2)exp by CB253 in cells was studied by ASO-Bind-Map. (62,63) This technique assesses target occupancy by competition between a complementary oligonucleotide, which induces the RNase H-mediated cleavage of target RNA, and the small molecule. (64) Briefly, if a small molecule stabilizes its cognate RNA target, it impedes hybridization of the ASO and hence its degradation. Indeed, 25 μM CB253 inhibited degradation of the r(G4C2)66 transcript in (G4C2)66-No ATG-GFP transfected HEK293T cells, as assessed by measuring transcript levels by RT-qPCR (Figure 6D). No change was observed in (G4C2)66-No ATG-GFP transcript levels in HEK293T cells transfected with a scrambled ASO, with or without treatment of CB253 (purple bars, Figure 6D).

Alleviation of Nucleocytoplasmic Transport Defects and Stress Granule Load in a HEK293T Model of c9ALS/FTD

Toxic RNA and dipeptide repeat species produced by C9orf72 HRE have previously been shown to impair nucleocytoplasmic transport in multiple model systems. (65) To study the effects of CB253 on localization of a fluorescent nucleocytoplasmic transport reporter, HEK293T cells stably expressing Lentiviral-S-tdTomato-NES (aka shuttle or S-tdTomato) that features a canonical nuclear localization signal (NLS) and a nuclear export sequence (NES) were cotransfected with a plasmid expressing (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc (RAN translation), (66) a canonical ATG-GFP (canonically expressed transfection control), and an SV40-Luc plasmid (used to normalize RAN translation in a dual luciferase reporter) and compared the S-tdTomato localization with cells expressing just ATG-GFP and SV40-Luc. As expected, expression of r(G4C2)exp via transfection of (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc shifted localization of S-tdTomato toward the cytoplasm without affecting GFP localization (Figure S28B,C), while transfection of ATG-GFP had little effect on the reporter’s localization (Figure 6E). Upon treatment of HEK293T cells expressing S-tdTomato, (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc, ATG-GFP, and SV40-Luc with 25 μM CB253, a 69 ± 3% rescue of the S-tdTomato cytoplasmic mislocalization was observed (Figure 6E); no effect was observed on GFP localization (Figure S28D). Cells from the same transfection were also screened for their ability to reduce RAN translation in a dual luciferase reporter screen. Upon treatment with 25 μM CB253, we observed a 79 ± 2% reduction of noncanonical translation of (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc with no decrease on canonically translated SV40-Luc (Figure S28E). Notably, similar results were observed in HEK293T cells expressing S-tdTomato cotransfected with (G4C2)66-No ATG-NLuc, ATG-GFP, and SV40-Luc treated with KPT-350 (KPT), an established selective inhibitor of Exportin-1. (67)

Previous work has established a link between nucleocytoplasmic transport defects and the presence of stress granules in c9ALS/FTD. (68) Expanded RNA repeats such as r(G4C2)exp are known to induce the formation of stress granules, leading to RNA/protein membrane-less deposits, further contributing to pathology. (69) Therefore, we utilized the HEK293T-S-tdTomato model system described above to assess the effects of CB253 on the formation of r(G4C2)66-induced stress granules. We observed a 74 ± 7% reduction in Ataxin-2 positive r(G4C2)66-induced stress granule abundance upon treatment with 25 μM CB253 (Figure 6F) with no effect on GFP signal (Figure S28F). To assess if this biological effect is specific to r(G4C2)exp-induced stress granules, we chemically induced stress granule formation with sodium arsenite (NaAsO2), a commonly used chemical stressor that leads to the accumulation of stress granules. (70) As expected, CB253 had no effect on the abundance of stress granules induced by NaAsO2 or GFP signal (Figure S28F), indicating that the observed reduction of (G4C2)66-induced stress granules by CB253 is a result of an RNA-specific mechanism of action (Figure 6F).

Reduction of Poly(GP) in c9ALS/FTD Patient-Derived Lymphoblastoid Cells

The biological activity of CB253 was assessed in a c9ALS/FTD patient-derived lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL). Lymphoblastoid cells were treated with CB253 for 48 h, with no significant toxicity observed when treated with up to 5 μM small molecule (Figure S28G). Under these conditions, CB253 dose dependently inhibited RAN translation, significantly reducing poly(GP) levels, as assessed by an electrochemical luminescence sandwich assay (Figure 6G). Collectively, our results indicate that CB253 is a promising chemical probe that inhibits various c9ALS/FTD-specific pathological mechanisms by directly engaging r(G4C2)exp.

Discussion

Herein, we highlight that the r(G4C2)exp hairpin features a diverse conformational ensemble exhibiting distinct motifs that can be stabilized with small molecules. In particular, the r(G4C2)exp hairpin not only consists of a well-characterized 1 × 1 GG internal loop population but also contains a minor, higher energy folding conformation that features 2 × 2 GG internal loops. We propose that the interconversion between these two folding states occurs via a strand slippage mechanism in r(G4C2) and r(C2G4) repeats, which is not available to r(CGG)exp, r(GGC)exp, r(UG3C2)exp as well as various mutated hairpin and duplex constructs. Although our work describing this process is novel for r(G4C2)exp, strand slippage has been previously demonstrated to occur spontaneously in DNA repeat expansions d(CAG)exp (71,72) and d(TGGAA)exp. (73) Additionally, “slippery” hairpins were reported in vitro for r(CUG)exp (74) and r(CCUG)exp (75) repeat expansions that cause DM1 and myotonic dystrophy type 2 (DM2), respectively.

We report a detailed picture of conformational transformations experienced in r(G4C2) repeat expansions, revealing a mechanism for this repeat to switch between a 2 × 2 GG loop and 1 × 1 loop conformation, as well as the overall stability of the 2 × 2 GG state. Further, we have shown data that suggests these small molecules can conformationally select for these alternative folding states, emphasizing the importance of minor folding populations. CB253 selectively targeted the minor 2 × 2 GG internal loop-containing population within r(G4C2)exp, binding this motif selectively over 1 × 1 GG internal loops and G–C base pairs. The m1G-modified 2 × 2 GG loops did not show changes upon addition of CB253, confirming the importance of the Watson–Crick edge of internal loop guanines for stabilizing the 2 × 2 GG conformation and shifting the dynamic equilibrium away from the more stable 1 × 1 GG internal loops. Conformational changes upon ligand binding have been observed for riboswitches, (76,77) and small molecules can stabilize conformations in the dynamic ensemble adopted by human immunodeficiency virus trans-activation response (HIV-1 TAR) RNA. (78,79) This work contrasts with induced fit ligands, such as cyclic mismatch binding ligands, which have been shown to stabilize unpaired nucleotides contained within 1 × 1 internal loops while unfolding the neighboring canonical base pairs. (80)

Our work adds to the growing examples of ligandable “RNA invisible states,” as the CB253 compound reported here can selectively stabilize an RNA fold that was not observed studying the RNA alone, supporting the notion that the diverse conformational ensemble adopted by RNAs in the solution can be exploited by small-molecule recognition for therapeutic benefit. Here, CB253 selectively inhibited RAN translation and stress granule formation and rescued nuclear transport defects in cellular models of c9ALS/FTD by direct target engagement. These results encourage further exploration into the ligandability of the r(G4C2)exp hairpin’s conformational ensemble to identify novel modes of binding that could be biologically and therapeutically relevant.

Supplementary Material

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health [R35 NS116846 to M.D.D., P01 NS099114-01 to M.D.D. and L.P., R35 NS097273 to L.P., S10 OD021550 for purchase of Bruker Avance III HD 600 MHz NMR spectrometer], Target ALS (to M.D.D.), the Nelson Family Fund (to M.D.D), DFG Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Milton Safenowitz Postdoctoral Fellowship from the ALS Association (ALSA) to A.U, the Huntington’s Disease Society of America (to J.T.B.), the Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation US Fellowship Research grant to S.C., and the Florida Atlantic University startup grant to I.Y.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

- Supporting information Table and Figures; experimental procedures; computational procedure; methods for cellular studies; references (PDF)

- Movie 1 (MP4)

- Movie 2 (MP4)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): M.D.D. is a founder of Expansion Therapeutics.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balendra R; Isaacs AM C9orf72-mediated ALS and FTD: multiple pathways to disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol 2018, 14, 544–558, DOI: 10.1038/s41582-018-0047-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor JP; Brown RH Jr; Cleveland DW Decoding ALS: from genes to mechanism. Nature 2016, 539, 197, DOI: 10.1038/nature20413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen X; Westergard T; Pasinelli P; Trotti D Pathogenic determinants and mechanisms of ALS/FTD linked to hexanucleotide repeat expansions in the C9orf72 gene. Neurosci. Lett 2017, 636, 16–26, DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd TW; Petrucelli L Insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of Chromosome 9 open reading frame 72 (C9orf72) repeat expansions. J. Neurochem 2016, 138, 145–162, DOI: 10.1111/jnc.13623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cleary JD; Ranum LPW New developments in RAN translation: insights from multiple diseases. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 2017, 44, 125–134, DOI: 10.1016/j.gde.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sztuba-Solinska J; Chavez-Calvillo G; Cline SE Unveiling the druggable RNA targets and small molecule therapeutics. Bioorg. Med. Chem 2019, 27, 2149–2165, DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.03.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connelly CM; Moon MH; Schneekloth JS The emerging role of RNA as a therapeutic target for small molecules. Cell Chem. Biol 2016, 23, 1077–1090, DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costales MG; Childs-Disney JL; Disney MD How we think about targeting RNA with small molecules. J. Med. Chem 2020, 63, 8880–8900, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Z; Zhang Y; Gendron TF; Bauer PO; Chew J; Yang W-Y; Fostvedt E; Jansen-West K; Belzil VV; Desaro P; Johnston A; Overstreet K; Oh S-Y; Todd PK; Berry JD; Cudkowicz ME; Boeve BF; Dickson D; Floeter MK; Traynor BJ; Bryan J; Morelli C; Ratti A; Silani V; Rademakers R; Brown Robert, H.; Rothstein Jeffrey, D.; Boylan Kevin, B.; Petrucelli L; Disney Matthew, D. Discovery of a biomarker and lead small molecules to target r(GGGGCC)-associated defects in c9FTD/ALS. Neuron 2014, 83, 1043–1050, DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamiri B; Reddy K; Macgregor RB; Pearson CE TMPyP4 porphyrin distorts RNA G-quadruplex structures of the disease-associated r(GGGGCC)n repeat of the C9orf72 gene and blocks interaction of RNA-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem 2014, 289, 4653–4659, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.C113.502336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z-F; Ursu A; Childs-Disney JL; Guertler R; Yang W-Y; Bernat V; Rzuczek SG; Fuerst R; Zhang Y-J; Gendron TF; Yildirim I; Dwyer BG; Rice JE; Petrucelli L; Disney MD The hairpin form of r(G4C2)exp in c9ALS/FTD is repeat-associated non-ATG translated and a target for bioactive small molecules. Cell Chem. Biol 2019, 26, 179–190, DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simone R; Balendra R; Moens TG; Preza E; Wilson KM; Heslegrave A; Woodling NS; Niccoli T; Gilbert-Jaramillo J; Abdelkarim S; Clayton EL; Clarke M; Konrad MT; Nicoll AJ; Mitchell JS; Calvo A; Chio A; Houlden H; Polke JM; Ismail MA; Stephens CE; Vo T; Farahat AA; Wilson WD; Boykin DW; Zetterberg H; Partridge L; Wray S; Parkinson G; Neidle S; Patani R; Fratta P; Isaacs AM G-quadruplex-binding small molecules ameliorate c9orf72 FTD/ALS pathology in vitro and in vivo. EMBO Mol. Med 2018, 10, 22–31, DOI: 10.15252/emmm.201707850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q; An Y; Chen ZS; Koon AC; Lau K-F; Ngo JCK; Chan HYEA Peptidylic inhibitor for meutralizing (GGGGCC)exp-associated neurodegeneration in c9ALS-FTD. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2019, 16, 172–185, DOI: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klim JR; Vance C; Scotter EL Antisense oligonucleotide therapies for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Existing and emerging targets. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2019, 110, 149–153, DOI: 10.1016/j.biocel.2019.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy LV; Miller TM RNA-targeted Therapeutics for ALS. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 424–427, DOI: 10.1007/s13311-015-0344-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mis MSC; Brajkovic S; Tafuri F; Bresolin N; Comi GP; Corti S Development of therapeutics for C9ORF72 ALS/FTD-related disorders. Mol. Neurobiol 2017, 54, 4466–4476, DOI: 10.1007/s12035-016-9993-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disney MD Targeting RNA with small molecules to capture opportunities at the intersection of chemistry, biology, and medicine. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 6776–6790, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.8b13419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin W; Rogge M Targeting RNA: a transformative therapeutic strategy. Clin. Transl. Sci 2019, 12, 98–112, DOI: 10.1111/cts.12624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar V; Islam A; Hassan MI; Ahmad F Therapeutic progress in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-beginning to learning. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2016, 121, 903–917, DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganser LR; Kelly ML; Herschlag D; Al-Hashimi HM The roles of structural dynamics in the cellular functions of RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2019, 20, 474–489, DOI: 10.1038/s41580-019-0136-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar V; Hasan GM; Hassan MI Unraveling the role of RNA mediated toxicity of C9orf72 repeats in C9-FTD/ALS. Front Neurosci. 2017, 11, 711 DOI: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ciesiolka A; Jazurek M; Drazkowska K; Krzyzosiak WJ Structural characteristics of simple RNA repeats associated with disease and their deleterious protein interactions. Front Cell Neurosci. 2017, 11, 97 DOI: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haeusler AR; Donnelly CJ; Periz G; Simko EAJ; Shaw PG; Kim M-S; Maragakis NJ; Troncoso JC; Pandey A; Sattler R; Rothstein JD; Wang J C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature 2014, 507, 195, DOI: 10.1038/nature13124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar V; kashav T; Islam A; Ahmad F; Hassan MI Structural insight into C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansions: Towards new therapeutic targets in FTD-ALS. Neurochem. Int 2016, 100, 11–20, DOI: 10.1016/j.neuint.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Božič T; Zalar M; Rogelj B; Plavec J; Šket P Structural diversity of sense and antisense RNA hexanucleotide repeats associated with ALS and FTLD. Molecules 2020, 25, 525 DOI: 10.3390/molecules25030525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X; Goodrich KJ; Conlon EG; Gao J; Erbse AH; Manley JL; Cech TR C9orf72 and triplet repeat disorder RNAs: G-quadruplex formation, binding to PRC2 and implications for disease mechanisms. RNA 2019, 25, 935–947, DOI: 10.1261/rna.071191.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reddy K; Zamiri B; Stanley SY; Macgregor RB Jr; Pearson CE The disease-associated r(GGGGCC)n repeat from the C9orf72 gene forms tract length-dependent uni- and multimolecular RNA G-quadruplex structures. J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 9860–9866, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.C113.452532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conlon EG; Lu L; Sharma A; Yamazaki T; Tang T; Shneider NA; Manley JL The C9ORF72 GGGGCC expansion forms RNA G-quadruplex inclusions and sequesters hnRNP H to disrupt splicing in ALS brains. eLife 2016, 5, e17820 DOI: 10.7554/eLife.17820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ursu A; Wang KW; Bush JA; Choudhary S; Chen JL; Baisden JT; Zhang Y-J; Gendron TF; Petrucelli L; Yildirim I; Disney MD Structural features of small molecules targeting the RNA repeat expansion that causes genetically defined ALS/FTD. ACS Chem. Biol 2020, 15, 3112–3123, DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.0c00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mustoe AM; Brooks CL; Al-Hashimi HM Hierarchy of RNA Functional Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2014, 83, 441–466, DOI: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dethoff EA; Petzold K; Chugh J; Casiano-Negroni A; Al-Hashimi HM Visualizing transient low-populated structures of RNA. Nature 2012, 491, 724, DOI: 10.1038/nature11498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orlovsky NI; Al-Hashimi HM; Oas TG Exposing Hidden High-Affinity RNA Conformational States. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 907–921, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.9b10535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganser LR; Kelly ML; Patwardhan NN; Hargrove AE; Al-Hashimi HM Demonstration that Small Molecules can Bind and Stabilize Low-abundance Short-lived RNA Excited Conformational States. J. Mol. Biol 2020, 432, 1297–1304, DOI: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganser LR; Chu C-C; Bogerd HP; Kelly ML; Cullen BR; Al-Hashimi HM Probing RNA conformational equilibria within the functional cellular context. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 2472–2480.e4, DOI: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Höbartner C; Micura R Bistable secondary structures of small RNAs and their structural probing by comparative imino proton NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol 2003, 325, 421–431, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01243-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fürtig B; Wenter P; Reymond L; Richter C; Pitsch S; Schwalbe H Conformational dynamics of bistable RNAs studied by time-resolved NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 16222–16229, DOI: 10.1021/ja076739r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haniff HS; Graves A; Disney MD Selective small molecule recognition of RNA base pairs. ACS Comb. Sci 2018, 20, 482–491, DOI: 10.1021/acscombsci.8b00049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joy C; Krista W; Charles W; Sae C; Danfeng Y; Henrik P; Jing W; Pu L; Bettina H; Weilei M; Ram V; Lian-She Z; Donald P; Greg C; Michael R; Kevin D; Huddee H; Tim E; Juan G; Michael H; Janette P-W; Scott L; Robert Z; Hong T Label-free detection of biomolecular interactions using bioLayer interferometry for kinetic characterization. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening 2009, 12, 791–800, DOI: 10.2174/138620709789104915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kiliszek A; Rypniewski W Structural studies of CNG repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 8189–8199, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gku536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Błaszczyk L; Rypniewski W; Kiliszek A Structures of RNA repeats associated with neurological diseases. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: RNA 2017, 8, e1412 DOI: 10.1002/wrna.1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kierzek R; Burkard ME; Turner DH Thermodynamics of single mismatches in RNA duplexes. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 14214–14223, DOI: 10.1021/bi991186l [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burkard ME; Turner DH NMR structures of r(GCAGGCGUGC)2 and determinants of stability for single guanosine–guanosine base pairs. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 11748–11762, DOI: 10.1021/bi000720i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salmon L; Yang S; Al-Hashimi HM Advances in the determination of nucleic acid conformational ensembles. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem 2014, 65, 293–316, DOI: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040412-110059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu C-C; Plangger R; Kreutz C; Al-Hashimi HM Dynamic ensemble of HIV-1 RRE stem IIB reveals non-native conformations that disrupt the Rev-binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 7105–7117, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkz498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee J; Dethoff EA; Al-Hashimi HM Invisible RNA state dynamically couples distant motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111, 9485–9490, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1407969111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnieders R; Keyhani S; Schwalbe H; Fürtig B More than proton detection-new avenues for NMR spectroscopy of RNA. Chem. - Eur. J 2020, 26, 102–113, DOI: 10.1002/chem.201903355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bellaousov S; Reuter JS; Seetin MG; Mathews DH RNAstructure: web servers for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W471–W474, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkt290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathews DH RNA secondary structure analysis using RNAstructure. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf 2014, 46, 1–25, DOI: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1206s46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y; Roland C; Sagui C Structure and dynamics of DNA and RNA double helices obtained from the GGGGCC and CCCCGG Hhexanucleotide repeats that are the hallmark of C9FTD/ALS diseases. ACS Chem. Neurosci 2017, 8, 578–591, DOI: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burkard ME; Xia T; Turner DH Thermodynamics of RNA internal loops with a guanosine-guanosine pair adjacent to another noncanonical pair. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 2478–2483, DOI: 10.1021/bi0012181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rangadurai A; Szymaski ES; Kimsey IJ; Shi H; Al-Hashimi HM Characterizing micro-to-millisecond chemical exchange in nucleic acids using off-resonance R1rho relaxation dispersion. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc 2019, 112–113, 55–102, DOI: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2019.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sholokh M; Sharma R; Grytsyk N; Zaghzi L; Postupalenko VY; Dziuba D; Barthes NPF; Michel BY; Boudier C; Zaporozhets OA; Tor Y; Burger A; Mély Y Environmentally sensitive fluorescent nucleoside analogues for surveying dynamic interconversions of nucleic acid structures. Chem. - Eur. J 2018, 24, 13850–13861, DOI: 10.1002/chem.201802297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rovira AR; Fin A; Tor Y Chemical mutagenesis of an emissive RNA alphabet. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 14602–14605, DOI: 10.1021/jacs.5b10420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puffer B; Kreutz C; Rieder U; Ebert M-O; Konrat R; Micura R 5-Fluoro pyrimidines: labels to probe DNA and RNA secondary structures by 1D 19F NMR spectroscopy. Nucleic Acid Res. 2009, 37, 7728–7740, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkp862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Höbartner C; Micura R Bistable secondary structures of small RNAs and their structural probing by comparative imino proton NMR spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol 2003, 325, 421–431, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01243-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hennig M; Scott LG; Sperling E; Bermel W; Williamson JR Synthesis of 5-fluoropyrimidine nucleotides as sensitive NMR probes of RNA structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 14911–14921, DOI: 10.1021/ja073825i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scott LG; Hennig M 19F-Site-Specific-Labeled Nucleotides for Nucleic Acid Structural Analysis by NMR. In Methods in Enzymol, Kelman Z, Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 2016; Chapter 3; Vol. 566, pp 59–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao C; Anklin C; Greenbaum NL Chapter Twelve - Use of 19F NMR Methods to Probe Conformational Heterogeneity and Dynamics of Exchange in Functional RNA Molecules. In Methods Enzymol.; Burke-Aguero DH, Ed.; Academic Press: New York, 2014; 549, 267–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Granqvist L; Virta P Characterization of G-quadruplex/hairpin transitions of RNAs by 19F NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Eur. J 2016, 22, 15360–15372, DOI: 10.1002/chem.201602898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Spasic A; Kennedy SD; Needham L; Manoharan M; Kierzek R; Turner DH; Mathews DH Molecular dynamics correctly models the unusual major conformation of the GAGU RNA internal loop and with NMR reveals an unusual minor conformation. RNA 2018, 24, 656–672, DOI: 10.1261/rna.064527.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou H; Kimsey IJ; Nikolova EN; Sathyamoorthy B; Grazioli G; McSally J; Bai T; Wunderlich CH; Kreutz C; Andricioaei I; Al-Hashimi HM m(1)A and m(1)G disrupt A-RNA structure through the intrinsic instability of Hoogsteen base pairs. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 2016, 23, 803–810, DOI: 10.1038/nsmb.3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang P; Park HJ; Zhang J; Junn E; Andrews RJ; Velagapudi SP; Abegg D; Vishnu K; Costales MG; Childs-Disney JL; Adibekian A; Moss WN; Mouradian MM; Disney MD Translation of the intrinsically disordered protein alpha-synuclein is inhibited by a small molecule targeting its structured mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2020, 117, 1457–1467, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1905057117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Childs-Disney JL; Tran T; Vummidi BR; Velagapudi SP; Haniff HS; Matsumoto Y; Crynen G; Southern MR; Biswas A; Wang Z-F; Tellinghuisen TL; Disney MD A Massively parallel selection of small molecule-RNA motif binding partners informs design of an antiviral from sequence. Chem 2018, 4, 2384–2404, DOI: 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cerritelli SM; Crouch RJ Ribonuclease H: the enzymes in eukaryotes. FEBS J. 2009, 276, 1494–1505, DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06908.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang Y-J; Gendron TF; Grima JC; Sasaguri H; Jansen-West K; Xu Y-F; Katzman RB; Gass J; Murray ME; Shinohara M; Lin W-L; Garrett A; Stankowski JN; Daughrity L; Tong J; Perkerson EA; Yue M; Chew J; Castanedes-Casey M; Kurti A; Wang ZS; Liesinger AM; Baker JD; Jiang J; Lagier-Tourenne C; Edbauer D; Cleveland DW; Rademakers R; Boylan KB; Bu G; Link CD; Dickey CA; Rothstein JD; Dickson DW; Fryer JD; Petrucelli L C9ORF72 poly(GA) aggregates sequester and impair HR23 and nucleocytoplasmic transport proteins. Nat. Neurosci 2016, 19, 668–677, DOI: 10.1038/nn.4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Z-F; Ursu A; Childs-Disney JL; Guertler R; Yang WY; Bernat V; Rzuczek SG; Fuerst R; Zhang YJ; Gendron TF; Yildirim I; Dwyer BG; Rice JE; Petrucelli L; Disney MD The hairpin form of r(G4C2)exp in c9ALS/FTD is repeat-associated non-ATG translated and a target for bioactive small molecules. Cell Chem. Biol 2019, 26, 179–190.e12, DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haines JD; Herbin O; de la Hera B; Vidaurre OG; Moy GA; Sun Q; Fung HY; Albrecht S; Alexandropoulos K; McCauley D; Chook YM; Kuhlmann T; Kidd GJ; Shacham S; Casaccia P Nuclear export inhibitors avert progression in preclinical models of inflammatory demyelination. Nat. Neurosci 2015, 18, 511–520, DOI: 10.1038/nn.3953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang K; Daigle JG; Cunningham KM; Coyne AN; Ruan K; Grima JC; Bowen KE; Wadhwa H; Yang P; Rigo F; Taylor JP; Gitler AD; Rothstein JD; Lloyd TE Stress granule assembly disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Cell 2018, 173, 958–971.e17, DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chew J; Cook C; Gendron TF; Jansen-West K; Del Rosso G; Daughrity LM; Castanedes-Casey M; Kurti A; Stankowski JN; Disney MD; Rothstein JD; Dickson DW; Fryer JD; Zhang YJ; Petrucelli L Aberrant deposition of stress granule-resident proteins linked to C9orf72-associated TDP-43 proteinopathy. Mol. Neurodegener 2019, 14, 9 DOI: 10.1186/s13024-019-0310-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bernstam L; Nriagu J Molecular aspects of arsenic stress. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part B 2000, 3, 293–322, DOI: 10.1080/109374000436355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ni C-W; Wei Y-J; Shen Y-I; Lee IR Long-Range Hairpin Slippage Reconfiguration Dynamics in Trinucleotide Repeat Sequences. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2019, 10, 3985–3990, DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu P; Pan F; Roland C; Sagui C; Weninger K Dynamics of strand slippage in DNA hairpins formed by CAG repeats: roles of sequence parity and trinucleotide interrupts. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 2232–2245, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkaa036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang T-Y; Chang C.-k.; Kao Y-F; Chin C-H; Ni C-W; Hsu H-Y; Hu N-J; Hsieh L-C; Chou S-H; Lee I-R; Hou M-H Parity-dependent hairpin configurations of repetitive DNA sequence promote slippage associated with DNA expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114, 9535–9540, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1708691114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Napierala M; Krzyzosiak WJ CUG repeats present in myotonin kinase RNA form metastable “slippery” hairpins. J. Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 31079–31085, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hale MA; Johnson NE; Berglund JA Repeat-associated RNA structure and aberrant splicing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gene Regul. Mech 2019, 1862, 194405 DOI: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Breaker RR Riboswitches and translation control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018, 10, a032797 DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reining A; Nozinovic S; Schlepckow K; Buhr F; Fürtig B; Schwalbe H Three-state mechanism couples ligand and temperature sensing in riboswitches. Nature 2013, 499, 355–359, DOI: 10.1038/nature12378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Turner BG; Summers MF Structural biology of HIV11. J. Mol. Biol 1999, 285, 1–32, DOI: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lu K; Heng X; Garyu L; Monti S; Garcia EL; Kharytonchyk S; Dorjsuren B; Kulandaivel G; Jones S; Hiremath A; Divakaruni SS; LaCotti C; Barton S; Tummillo D; Hosic A; Edme K; Albrecht S; Telesnitsky A; Summers MF NMR detection of structures in the HIV-1 5′-leader RNA that regulate genome packaging. Science 2011, 334, 242–245, DOI: 10.1126/science.1210460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mukherjee S; Blaszczyk L; Rypniewski W; Falschlunger C; Micura R; Murata A; Dohno C; Nakatani K; Kiliszek A Structural insights into synthetic ligands targeting A-A pairs in disease-related CAG RNA repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 10906–10913, DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkz832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.