Abstract

Prior research and the popular press have anecdotally reported inadequate nursing home staffing levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maintaining adequate staffing levels is critical to ensuring high-quality nursing home care and an effective response to the pandemic. We therefore sought to examine nursing home staffing levels during the first nine months of 2020 (compared with the same period in 2019), using auditable daily payroll-based staffing data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. We found that the total number of hours of direct care nursing declined in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic, as did the average nursing home census. When we accounted for changes in census, the number of nurse staff hours per resident day remained steady or, if anything, increased slightly during the pandemic. The observed increases in staff hours per resident day were small but concentrated in nursing homes operating in counties with high COVID-19 prevalence, in nursing homes with low Medicaid census (which typically have more financial resources), and in not-for-profit nursing homes (which typically invest more in staffing). These findings raise concerns that although the number of staff hours in nursing homes did not decline, the perception of shortages has been driven by increased stresses and demands on staff time due to the pandemic, which are harder to quantify.

Since the first outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, nursing homes have remained an epicenter of the pandemic, with more than one-third of US COVID-19 deaths occurring in nursing homes.1 Nursing home staff, many of whom provide direct care to residents, have also been hard hit by COVID-19, with high rates of infection and many deaths.1

Maintaining adequate staffing levels is critical to ensuring high-quality nursing home care2,3 and is an effective response to the pandemic.4 However, low wages and difficult work environments have made maintaining adequate staffing levels in nursing homes a chronic problem.5 Staffing difficulties were exacerbated during the pandemic6,7 because of job-specific factors such as the high COVID-19 exposure risk that is the nature of the job, shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) for nursing home staff,8 staff-reported exposure to the virus requiring quarantine, and staff burnout, among other challenges. These issues disproportionately affected female and minority workers,9 who are overrepresented in a sector that was also hit by day care, school, and elder care closures in addition to the COVID-19 exposure risk related to everyday activities.

Prior national research8,10 has noted staff shortages in nursing homes during the pandemic, with 15–20 percent of nursing homes reporting a shortage, most commonly among nurse aides. However, these reports have relied on self-reported data from nursing homes, which are prone to error and bias. This has left significant uncertainty about whether nursing homes have experienced staff shortages and the magnitude of those shortages, if any. Even in the absence of staff shortages, it is possible that nursing home staff perceived shortages because of the increased COVID-19-related stresses and demands on their time, including containing the spread of the virus and the lockdowns that prevented visitors and other forms of help in the homes.

In this article we examine changes in nursing home staffing during the pandemic, using data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Payroll Based Journal (PBJ) system, to which nursing homes are required to submit auditable daily payroll-based staffing and resident census data.

Study Data And Methods

DATA SOURCES

Our main data source is the PBJ system11 from January 2019 through September 2020. Nursing homes are required by Section 6106 of the Affordable Care Act to submit auditable payroll-based staffing and resident census data quarterly.12 These data provide snapshots of both the daily total number of nursing home residents and hours of staffing. Staff hours were included for all direct care staff, both employed and contract: registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants We aggregated the daily PBJ data to seven-day averages of staffing and census for each week in each nursing home. We report findings for the first nine months, or thirty-seven weeks, of 2020.

CMS temporarily suspended reporting requirements for the PBJ system for the first quarter of 2020. There was a decline in the number of nursing homes reporting data in the PBJ system in that quarter (the number of nursing homes reporting staffing data in the first quarter of 2020 was 17.9 percent lower than the number reporting staffing data in the fourth quarter of 2019), but the number of nursing homes reporting staffing data rebounded to close to baseline levels for the second quarter of 2020 (the number of nursing homes reporting staffing data in the second quarter of 2020 was only 1.6 percent lower than the number reporting staffing data in the fourth quarter of 2019). We therefore interpret the results from the first quarter of 2020 with caution.

We supplemented the PBJ data with data from two other sources: county-level COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population (population-based estimates of cumulative cases through May 31, 2020, from the New York Times COVID-19 data, obtained from Social Explorer) and nursing home characteristics from LTCfocus.org13 for 2017, the most recent year available.

MEASURES OF STAFFING

Summaries of nursing home staffing and staffing per resident day were reported across all nursing homes and also stratified by county-level COVID-19 rates.We defined high-COVID-19 counties as those with more than 600 cases per 100,000 population (3,680 nursing homes in 492 US counties, or 25.3 percent of nursing homes in 17.0 percent of counties) and low-COVID-19 counties as those with fewer than 125 cases per 100,000 population (3,738 nursing homes in 1,212 counties, or 25.7 percent of nursing homes in 41.8 percent of counties). We also stratified by a nursing home’s profit status; the percentage of Medicaid residents in each facility, defining high-Medicaid facilities as those with more than 75 percent Medicaid residents (3,993 or 27.4 percent of nursing homes) and low-Medicaid facilities as those with less than 45 percent (3,002 or 20.6 percent of nursing homes); whether the nursing home was hospital based; and nursing home size, defining nursing homes with more than 125 beds (the top quartile of nursing homes) as large and those with fewer than 65 beds (the bottom quartile of nursing homes) as small. Summaries were reported as weekly averages during the study period as well as the change in levels during the thirty-seven weeks in absolute and relative terms. These changes were calculated according to the difference between the average level in January 2020 (the first four weeks of 2020) and September 2020 (the last four weeks of the study period).

LIMITATIONS

There were several limitations to this study. First, the PBJ system only collects data reported on paid hours, so the data might not reflect any fluctuations in the hours of salaried staff, as their pay will not change with an increase in hours. However, four out of five nursing staff members are paid hourly, according to the Current Population Survey.14 The PBJ data may also include paid sick leave. However, recent data suggest that a large proportion of nursing home workers were ineligible for sick leave even under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act, which expanded emergency sick leave.15 The data may also include non–direct care nurses or those doing administrative work.16 Furthermore, although the PBJ data provide information about the number of hours that staff members work, they do not shed light on the difficulty of that work, preventing us from commenting on whether staff work changed qualitatively during the pandemic.

Another limitation stems from the rapid evolution of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although we examined trends in the early months of the US pandemic, it is possible that trends in the first six months do not reflect the reality in nursing homes a year into the pandemic. Nevertheless, this study represents the most accurate assessment to date of changes in nursing home staffing, using the most recent data available.

Study Results

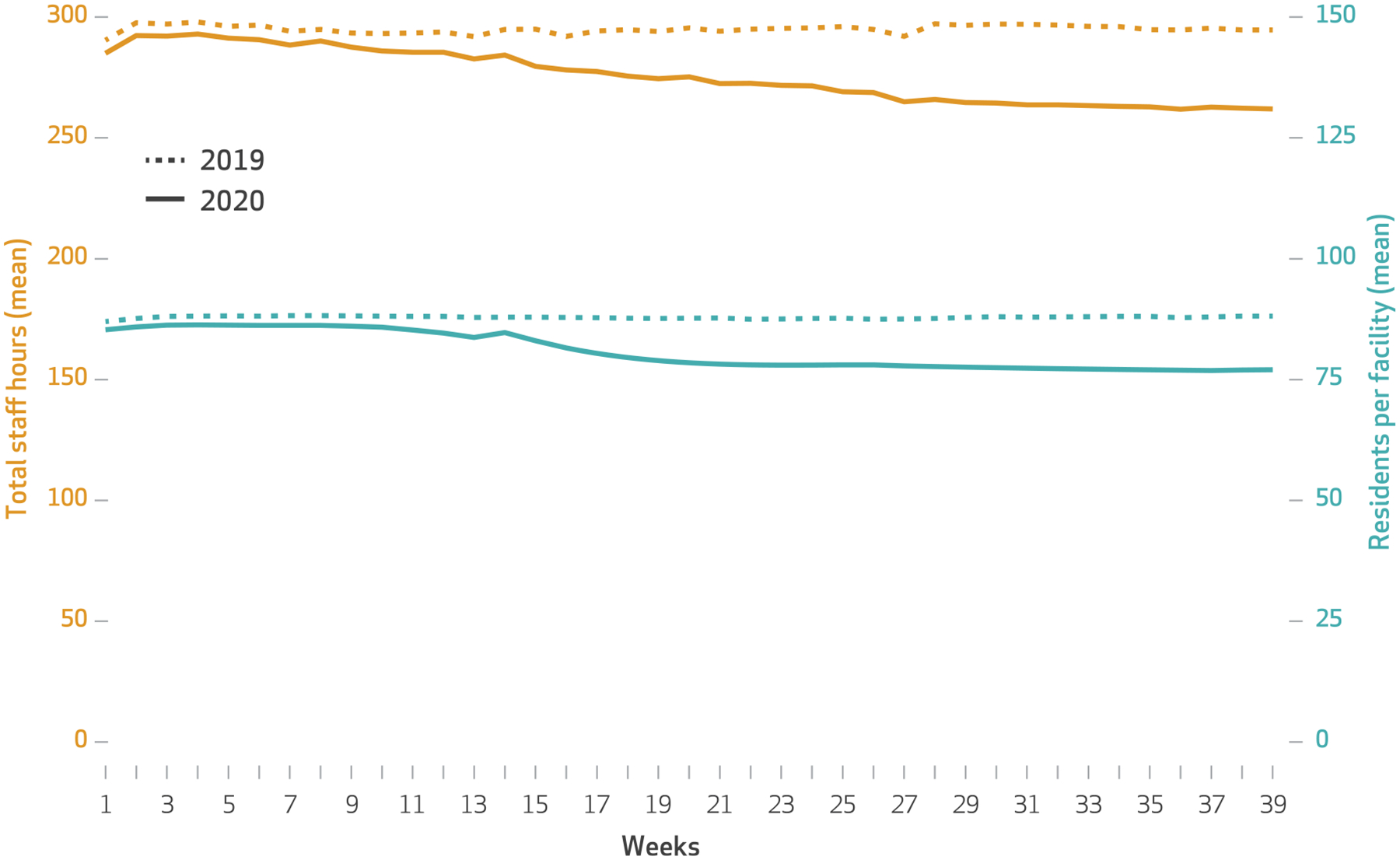

Across 14,554 US nursing homes, average nursing home resident census began to decline in March 2020. By the end of September 2020, nursing home census had declined an average of nine residents per nursing home, going from an average of eighty-six residents in January 2020 to seventy-seven residents in September 2020, for a drop of 10.5 percent. In comparison, during the same period in 2019, nursing home census increased by 0.3 residents, or 0.3 percent (exhibit 1).

EXHIBIT 1.

Numbers of total staff hours and nursing home residents in US nursing homes during the first 39 weeks of 2019 and 2020

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Payroll-Based Journal system. NOTE Total staff hours include hours of registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants.

The average total number of nurse staff hours per day in nursing homes also dropped between January and September 2020, going from 291 hours down to 262 hours, for a decline of 28.4 hours or a relative decline of 9.8 percent. In 2019 there was a small decrease in staff hours of one hour or 0.3 percent during the same period.

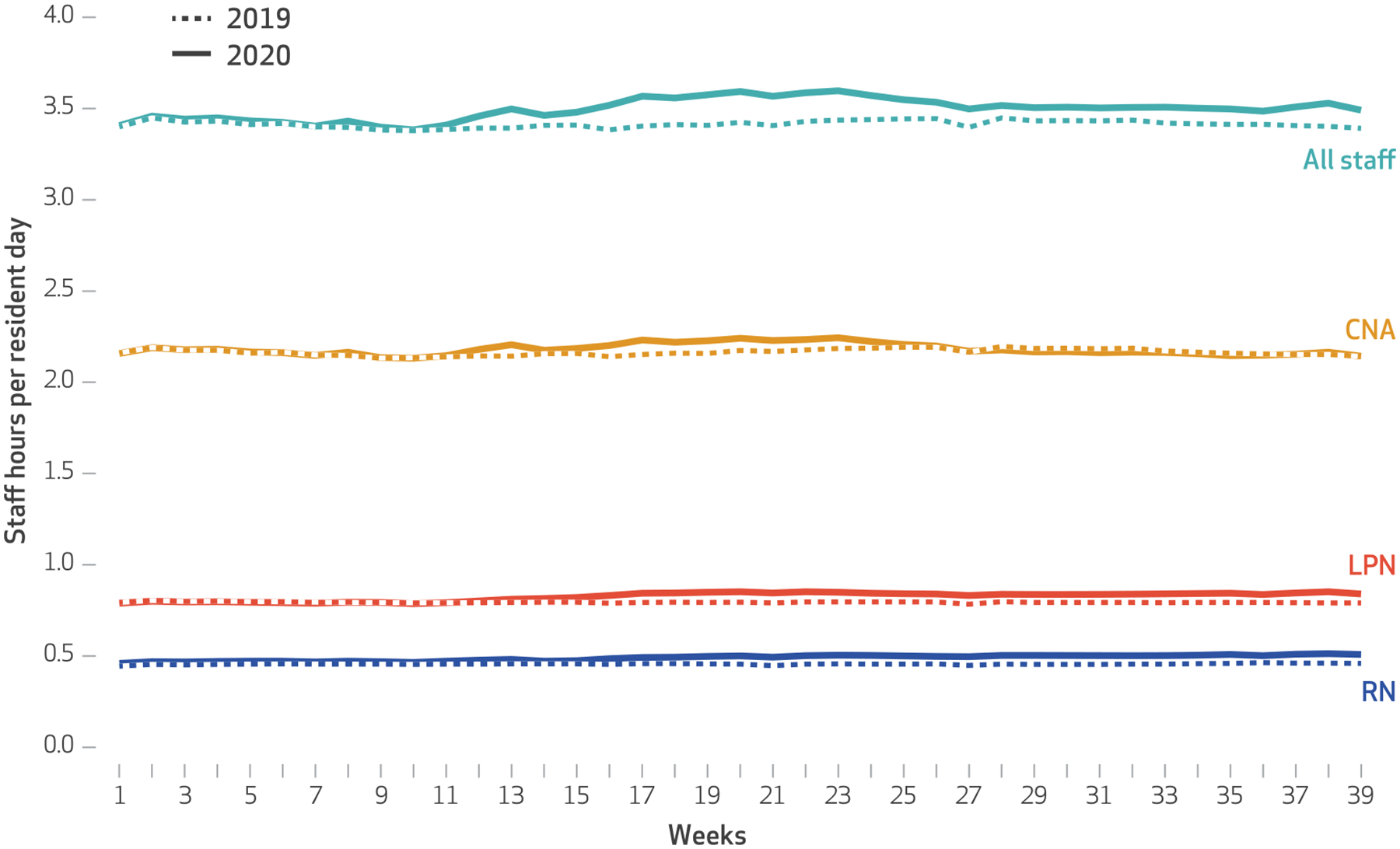

Trends in nurse staff hours per resident day, a measure that accounts for the changes in nursing home census, show that nursing home staffing increased slightly between January and September 2020, as well as relative to the same period in 2019, going from 3.4 hours per resident day in January 2020 to 3.5 hours per resident day in September 2020. This translates to an absolute increase of 5.7 minutes per resident day and a relative increase of 2.8 percent (exhibit 2). The changes in staffing were small and similar in absolute terms across registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants (ranging from a decrease of 0.5 minutes per resident day for certified nursing assistants to an increase of 3.2 minutes per resident day for licensed practical nurses).

EXHIBIT 2.

Nurse staff hours per resident day in US nursing homes in the first 39 weeks of 2020

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Payroll-Based Journal system. NOTE Staff hours include registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and certified nursing assistants (CNAs).

When comparing changes in staff hours per resident day for employed versus contract staffing, we found small increases in hours per resident day for both groups. Employed nursing home staff increased from 3.3 hours per resident day in January 2020 to 3.4 in September 2020, for a relative increase of 1.0 percent. Contract nursing home staff, which make up a small proportion of nursing home staff, on average, increased from 0.11 hours to 0.14 hours per resident day during the same period, a relative increase of 28.9 percent (data not shown).

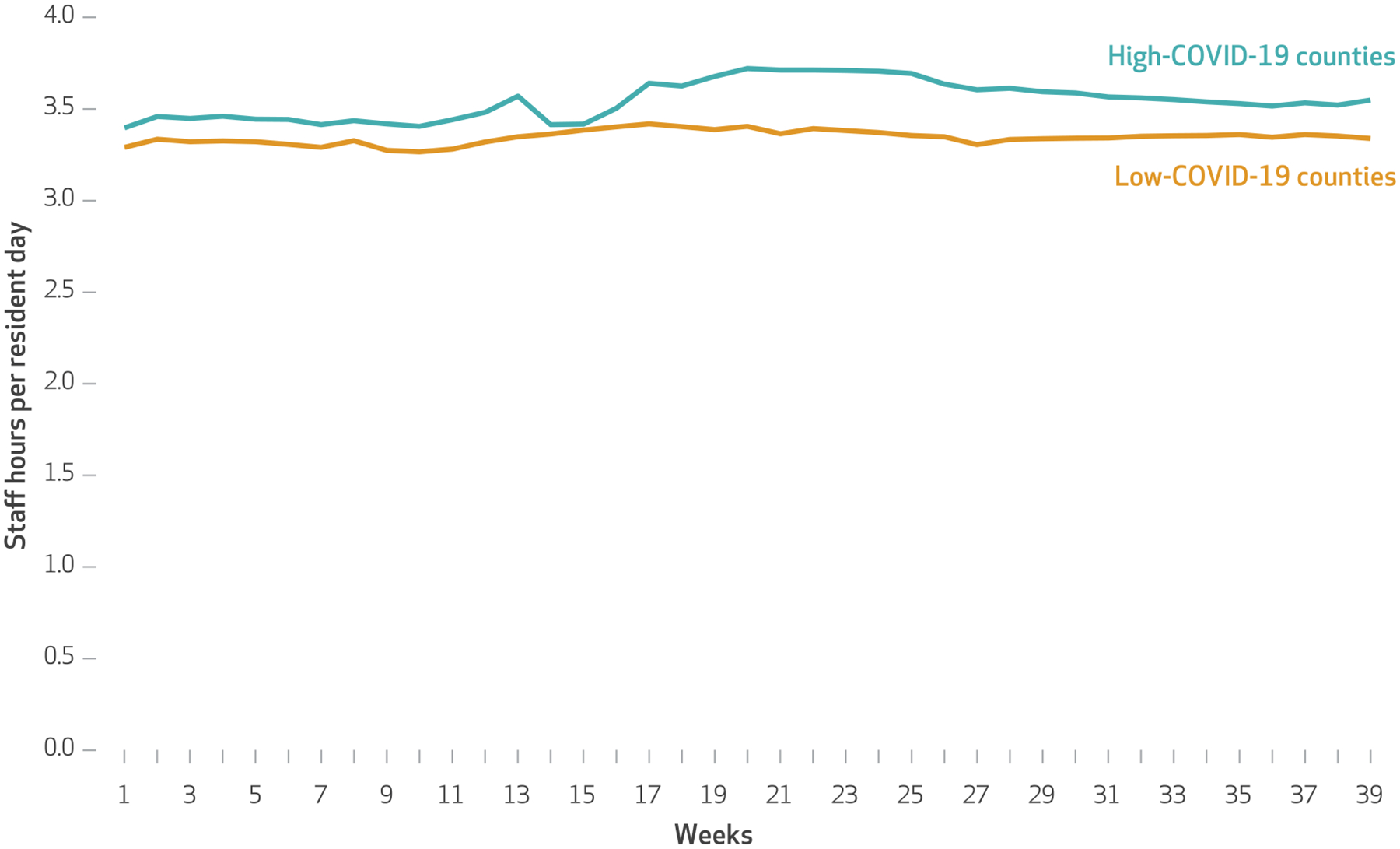

These increases in staff hours per resident day were driven by counties that had high COVID-19 case rates (exhibit 3). In those counties, staff hours increased by 5.3 minutes per resident day, on average, between January and September 2020 compared with an increase of 1.9 minutes per resident day in low-COVID-19 counties. The larger increase in staffing levels in nursing homes in high-COVID-19 counties was driven by a larger decline in the average nursing home census in those counties compared with nursing homes in low-COVID-19 counties. Nursing homes in high-COVID-19 counties had a decline in the census of 11.3 percent compared with a decline of 9.2 percent in low-COVID-19 counties (data not shown).

EXHIBIT 3.

Nurse staff hours per resident day in nursing homes located in counties with high and low numbers of COVID-19 cases per population in the first 39 weeks of 2020

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Payroll-Based Journal system, and New York Times county-level cumulative COVID-19 cases through May 31, 2020 (from Social Explorer). NOTES Staff hours include hours for registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants. “High-COVID-19 counties” refers to those with more than 600 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population, and “low-COVID-19 counties” refers to those with fewer than 125 cases per 100,000 population.

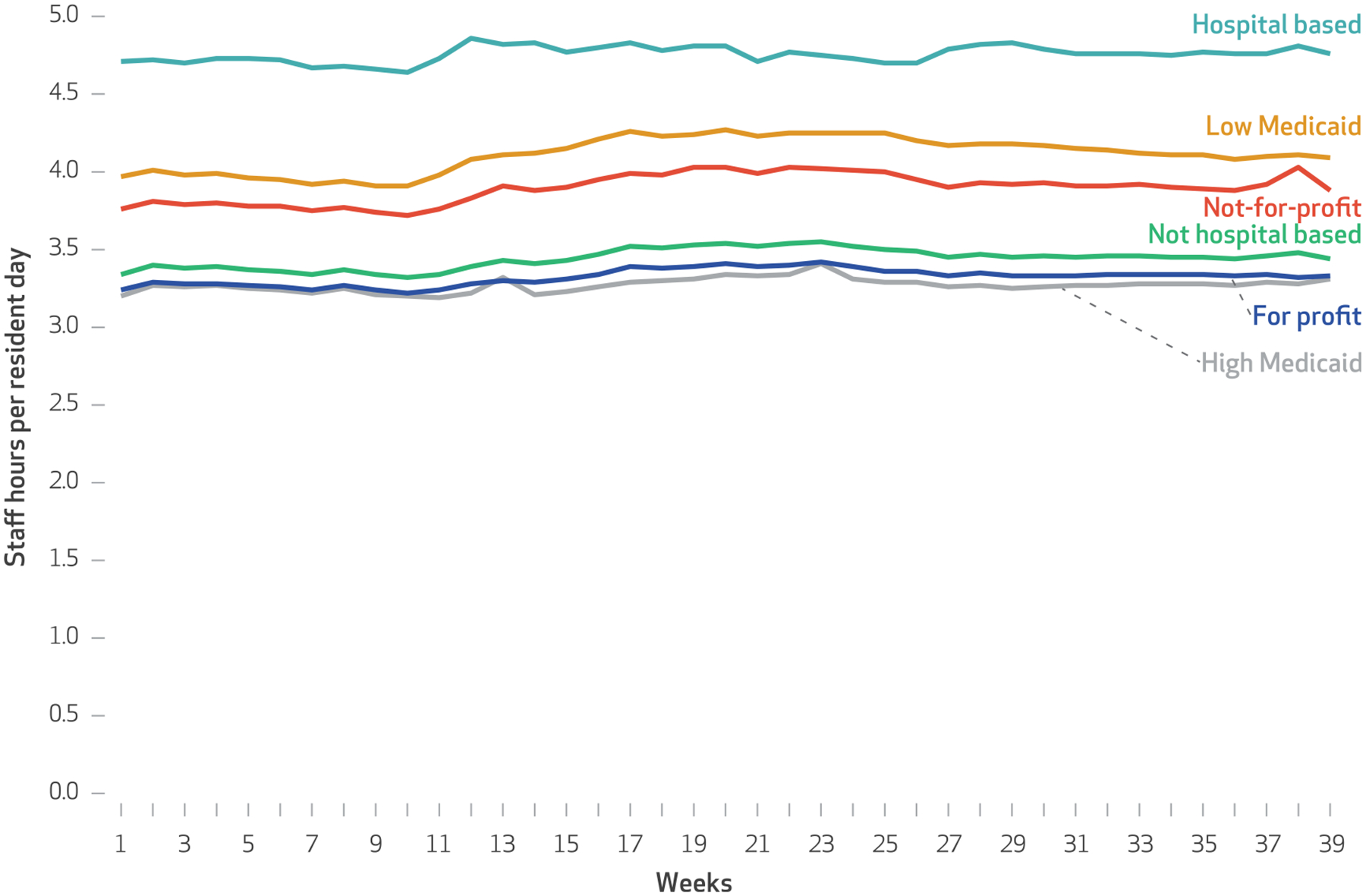

Increases in staff hours per resident day were more than twice as large in not-for-profit nursing homes than in for-profit homes (8.3 versus 3.5 minutes) and in low-Medicaid nursing homes compared with in high-Medicaid nursing homes (6.5 versus 2.3 minutes) (exhibit 4). Hospital-based nursing homes, which typically concentrate on postacute rather than long-term care, had slightly smaller declines in staffing compared with nursing homes that were not hospital based (3.5 versus 4.7 minutes; exhibit 4) and also had a smaller decline in average census than did freestanding nursing homes (6.5 percent versus 10.8 percent, respectively; data not shown). Large and small facilities experienced similar reductions in staff hours per resident day (1.8 percent in large facilities versus 2.0 percent in small facilities; data not shown).

EXHIBIT 4.

Nurse staff hours per resident day in nursing homes with various characteristics in the first 39 weeks of 2020

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Payroll-Based Journal system and from LTCfocus.org. NOTES Staff hours include hours for registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, and certified nursing assistants. “High Medicaid” refers to facilities with more than 75 percent Medicaid residents, and “low Medicaid” to facilities with less than 45 percent.

Discussion

There have been chronic concerns about nursing home staffing during the COVID-19 pandemic, with many anecdotal reports of difficulties maintaining adequate nursing home staff.6–8,10 We used payroll data to examine levels of nursing home staffing during the first nine months of 2020. Although we found that the total number of hours worked by nursing home staff declined during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a concurrent decline in the average nursing home census during the same period.When we accounted for this decline in census, nurse staff hours per resident day remained steady or increased slightly. The observed increases in staffing were small in absolute terms but were concentrated in nursing homes operating in high-COVID-19 counties. They were also concentrated in nursing homes with low Medicaid census, which typically have more financial resources, and in not-for-profit nursing homes, which typically invest more in staffing.

Our analysis using Payroll-Based Journal data provides the most reliable estimates to date of how COVID-19 affected levels of nursing home staffing. Instead of using self-reported data, we used auditable daily payroll-based staffing levels in every Medicare and Medicaid-certified nursing home in the US. The stable levels of staffing we demonstrate do not suggest that the anecdotal and survey-based reports of difficulties in staffing nursing homes during the pandemic are inaccurate.

Some recent reports have questioned the reliability of the Payroll-Based-Journal data we used,16 finding that some nursing homes include hours from administrators who do not directly care for patients. However, nursing home administrators are typically registered nurses, not licensed practical nurses or certified nursing assistants. Our findings of stable or increased staffing levels during the pandemic held across all three types of staff, suggesting that our findings are not due to these reporting practices.

How can we reconcile these discrepant reports? First, nursing homes may be struggling to keep their facilities staffed and also succeeding at doing so. We found that nursing homes increased their reliance on contractors during the pandemic. The pandemic may also have resulted in higher rates of turnover among nursing home staff—rates that were high even before the pandemic.17 Although contactors have helped fill the gaps during the pandemic, they might not completely alleviate the stress on existing employees.18 In addition, contractors and new employees may be less well integrated with existing employed staff, nursing home processes, and residents.

Pandemic-related policies may have helped alleviate staffing shortages. Early in the pandemic, in an acknowledgment that nursing homes were struggling to maintain adequate staffing levels, CMS temporarily suspended the competency requirement for providing direct care to nursing home residents.19 But despite these efforts, there have been persistent reports of shortages.

It is possible that the workload for nurse staffing has increased during the pandemic. In other words, an hour of work during the pandemic may be more difficult than an hour of work in 2019. This may be true for several reasons. As nursing homes banned visitors in an effort to protect the residents from unintentional spread of the coronavirus, they also lost the assistance from caregivers that they often rely on. Family members and friends routinely supply care to nursing home residents, including socioemotional support and personal care, such as helping to feed, bathe, and dress residents.20 Without visits from caregivers, nursing home staff were forced to fill in these activities, adding tasks to their already stretched days. In addition, it is possible that although the number of hours worked remained stable, there were fewer staff members working those hours, resulting in the perception of increased shortages and burnout.

It is also possible that even in the absence of an increase in the quantity of work each staff member had to do, the work itself was made harder by the pandemic. Nursing homes implemented numerous measures for infection control that increased staff work and made day-to-day activities more difficult, which would likely lead to the perception of staff shortages without an observed change in the number of hours per resident day worked. The reports of increased stress and burnout among nursing home staff during the pandemic support this possibility. Also, more staff members could be needed during a pandemic to separately care for patients with and without COVID-19.

Stress and burnout themselves may add to the perception of shortages. Staff have routinely reported shortages of PPE and fears of infecting themselves or their family members while also protecting and caring for nursing home residents.21 Perceptions of staffing shortages may in part reflect the increased pressure under which staff now routinely work in nursing homes.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed nursing homes under substantial pressure, with many reports of inadequate staffing. Despite these reports, on average we found no meaningful declines in staffing during the pandemic and, if anything, a slight increase in staff hours per resident day. Although these findings may be reassuring, the loss of family caregivers because of visitor bans and the cancellation of group activities increased the demands on nursing home staff. At the same time, staff members were putting themselves at risk providing intense and personal care to residents, often without adequate PPE and while mourning the loss of residents they had known and cared for.

Prioritizing vaccinating nursing home residents and staff for coronavirus will help reduce the risk for infection, but with unequal and uneven distribution and take-up of the vaccine along with emerging concerns about whether the vaccines are effective against new variants of virus, the vaccine is only part of the solution. Policies should also focus on increasing support to nursing homes and their staff. Providing staff with widespread access to testing, hazard pay, safe transportation, expanded paid sick leave—including for mental health and quarantining—and ways to safely allow family members back into the nursing home are just a few of the ways to bolster nursing home staff, along with the residents they care for.

Acknowledgments

Rachel Werner was supported in part by Grant No. K24-AG047908 from the National Institute on Aging.

Contributor Information

Rachel M. Werner, Robert D. Eilers Professor of Health Care Management at the Wharton School, a professor of medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, and executive director of the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, all at the University of Pennsylvania, and core faculty at the Center for Health Equity Research and Promotion, Corporal Michael J. Crescenz Veterans Affairs Medical Center, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Norma B. Coe, associate professor in the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy, Perelman School of Medicine, and senior fellow at the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, both at the University of Pennsylvania.

NOTES

- 1.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 nursing home data [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2021. Feb 28 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://data.cms.gov/stories/s/COVID-19-Nursing-Home-Data/bkwz-xpvg/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konetzka RT, Stearns SC, Park J. The staffing-outcomes relationship in nursing homes. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):1025–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antwi YA, Bowblis JR. The impact of nurse turnover on quality of care and mortality in nursing homes: evidence from the Great Recession. Am J Health Econ. 2018;4(2):131–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorges RJ, Konetzka RT. Staffing levels and COVID-19 cases and outbreaks in U.S. nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2462–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donoghue C Nursing home staff turnover and retention: an analysis of national level data. J Appl Gerontol. 2010;29(1):89–106. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirkham C, Lesser B. Special report: pandemic exposes systemic staffing problems at U.S. nursing homes. Reuters [serial on the Internet]. 2020. Jun 10 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-nursinghomes-speci/special-report-pandemic-exposes-systemic-staffing-problems-at-u-s-nursing-homes-idUSKBN23H1L9

- 7.Quinton S. Staffing nursing homes was hard before the pandemic. Now it’s even tougher [Internet]. Washington (DC): Pew Charitable Trusts; 2020. May 18 [cited 2021 Mar17]. Available from: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/05/18/staffing-nursing-homes-was-hard-before-the-pandemic-now-its-even-tougher [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGarry BE, Grabowski DC, Barnett ML. Severe staffing and personal protective equipment shortages faced by nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(10):1812–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Houtven CH, DePasquale N, Coe NB. Essential long-term care workers commonly hold second jobs and double- or triple-duty caregiving roles. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(8): 1657–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu H, Intrator O, Bowblis JR. Shortages of staff in nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: what are the driving factors? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(10):1371–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. PBJ daily nurse staffing [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2020. [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://data.cms.gov/browse?q=payroll+based+journal [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Electronic staffing data submission Payroll-Based Journal: long-term care facility policy manual [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2018. Oct [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/NursingHomeQualityInits/Downloads/PBJ-Policy-Manual-Final-V25-11-19-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown University. LTCfocus [home page on the Internet]. Providence (RI): Brown School of Public Health; [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: http://ltcfocus.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geng F, Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Daily nursing home staffing levels highly variable, often below CMS expectations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1095–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long M, Rae M. Gaps in the emergency paid sick leave law for health care workers [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2020. Jun 17 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from:https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/gaps-in-emergency-paid-sick-leave-law-for-health-care-workers/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silver-Greenberg J, Gebeloff R. Maggots, rape, and yet five stars: how U.S. ratings of nursing homes mislead the public New York Times; [serial on the Internet]. 2021. Mar 13 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/13/business/nursing-homes-ratings-medicare-covid.html [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gandhi A,Yu H, Grabowski DC. High nursing staff turnover in nursing homes offers important quality information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(3):384–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu SF, Lu LX. Do mandatory overtime laws improve quality? Staffing decisions and operational flexibility of nursing homes. Manage Sci. 2017;63(11):3566–85. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2021. Feb 19 [cited 2021 Mar 17]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/summary-covid-19-emergency-declaration-waivers.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaugler JE. Family involvement in residential long-term care: a synthesis and critical review. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9(2):105–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White EM, Wetle TF, Reddy A, Baier RR. Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021;22(1):199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]