Abstract

It has been more than 80 years since researchers in child psychiatry first documented developmental delays among children separated from family environments and placed in orphanages or other institutions. Informed by such findings, global conventions, including the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, assert a child’s right to care within a family-like environment that offers individualised support. Nevertheless, an estimated 8 million children are presently growing up in congregate care institutions. Common reasons for institutionalisation include orphaning, abandonment due to poverty, abuse in families of origin, disability, and mental illness. Although the practice remains widespread, a robust body of scientific work suggests that institutionalisation in early childhood can incur developmental damage across diverse domains. Specific deficits have been documented in areas including physical growth, cognitive function, neurodevelopment, and social-psychological health. Effects seem most pronounced when children have least access to individualised caregiving, and when deprivation coincides with early developmental sensitive periods. Offering hope, early interventions that place institutionalised children into families have afforded substantial recovery. The strength of scientific evidence imparts urgency to efforts to achieve deinstitutionalisation in global child protection sectors, and to intervene early for individual children experiencing deprivation.

Introduction

Societies have always faced the question of whether and how to care for children who do not have access to a safe family environment; however, absolute numbers provided by reports suggest the question has arguably never been larger. The UN’s 2006 World Report on Violence against Children1 estimates that 133–275 million children every year witness violence between primary caregivers on a regular basis, whereas at least 150 million girls and 73 million boys are victims of forced sexual activity.1 Among the most vulnerable are “children outside of family care”.2–4 UNICEF estimates that up to 100 million children live on the street, while 1.2 million are victims of sex and labour trafficking;5 the UN’s 2007 Paris Principles on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups estimates that “hundreds of thousands” of children have been enlisted in various roles to serve armed forces worldwide.6 What might the science of early development tell us about appropriate strategies to meet the needs of these children?

In 1915, JAMA published an article entitled “Are institutions for infants really necessary?”,7 in which the author made a simple claim that children do best in family environments. It states, “Strange to say, these important conditions have often been overlooked, or, at least, not sufficiently emphasised, by those who are working in this field”.7 Following the publication of this article nearly a century ago, scientific studies began to document stunted cognitive, social, and physical development among children placed in institutions during key developmental years.8–12 In 1989, the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child13 (endorsed by nearly all countries, although not in the USA) drew upon scientific findings to generate international normative standards, asserting that “the child, for the full and harmonious development of his or her personality, should grow up in a family environment, in an atmosphere of happiness, love, and understanding”.

Despite strong rhetoric and evidence, the practice of raising children in large institutions persists in every region of the world, with estimates suggesting that at least 8 million children worldwide are now growing up in institutional settings.14 In some locations, the practice even seems to be increasing. For example, in 2004, the Chinese Government launched the construction of new large-scale orphanages to house children who had lost parents to HIV/AIDS.15 The question remains: is the global child protection community still inadequately prioritising core developmental needs for individualised caregiving in family-like environments?

In this Review, we discuss the worldwide phenomenon of child institutionalisation as a social strategy to raise children lacking access to safe family care. With a comprehensive search strategy, we assess scientific evidence on the developmental effects of early institutional care. Within this vast body of evidence, many decades of observational data and a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT; 2000 to present)16 document profound developmental delay across nearly all domains among children who spend their early years in institutional care. Furthermore, the data suggest that there might be particular windows of time in early childhood, commonly termed sensitive periods, when the effects of intervention are most substantial, and after which deficits become increasingly intractable. These findings have implications for policy and practice that aim to care for vulnerable children worldwide while protecting them from the worst forms of institutionalisation.

Global child institutionalisation

Significance

Findings on the effects of early institutionalisation might yield broader insights into the developmental effects of early deprivation and adversity. Children growing up in institutions represent a small share of the much larger number of children who need protective services. Yet the experiences of these children might offer more general insights about the effects of early psychosocial deprivation. These insights, in turn, have relevance to our understanding of the more globally prevalent problem of child neglect. Indeed, in the USA, 2012 data from the Department of Health and Human Services documented that 78.3% of children receiving child protective services were victims of neglect, more than the percentages of children experiencing physical, sexual, psychological, and medical abuse combined.17 Research presented here on the developmental effects of early psychosocial deprivation in institutions could also lend insight to spur future work on neglect and development more broadly. It might also suggest that societies still relying on large institutions are failing to grasp core needs that must inform child protection strategies more generally.

Definition of child institutionalisation

In the context of this Review, an institution is defined as any large congregate care facility in which round-the-clock professional supervision supplants the role of family-like caregivers. Institutions might house children having no family care for reasons of orphaning, abandonment, or abuse, in addition to children with disabilities, mental or physical illness, or other special needs. This Review excludes settings that could be deemed hospitals or medical facilities for disorders that need continual specialist care—although it should be noted that advocates of deinstitutionalisation in various medical fields call for the political and social support needed to make home-based and community-based care feasible for a wider range of children.18 Drawing on the definition used by UNICEF, this Review defines childhood as the period from 0 to 17 years of age and early childhood as the period from 0 to 8 years of age.

Inevitably, facilities termed institutions are highly diverse. The US federal Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) designates institutions as substitute care facilities that house more than 12 children,18 and similarly small institutional homes have been studied in South Africa and elsewhere.19 However, many international institutions are much larger, with populations in the hundreds.20 Yet even within this diversity, the Eurochild working group21 notes an empirical tendency for institutions to acquire some shared and fundamentally depriving characteristics, including a tendency to isolate children from the broader social world and an inability to offer the consistent and personalised caregiver attention thought to underlie healthy social and emotional growth (panel 1). Some deem these empirical findings inherent to institutional care. In a report in 2007, UNICEF22 quoted disability rights activist Gunnar Dybwad stating that: “four decades of work to improve the living conditions of children with disabilities in institutions have taught us one major lesson: there is no such thing as a good institution”.

Panel 1: What makes an institution?

A European Commission22 expert group report suggests that institutions across diverse settings tend to acquire common characteristics harmful to developing children. Among these are: depersonalisation, or a lack of personal possessions, care relationships, or symbols of individuality; rigidity of routine, such that all life activities occur in repetitive, fixed daily timetables unresponsive to individual needs and preferences; block treatment, with most routine activities performed alongside many children; and social distance, or isolation from extra-institutional society.

Counting unseen children

Efforts to quantify and describe worldwide child institutionalisation are limited by the scarcity of high-quality data. In 2009, UNICEF23 documented more than 2 million institutionalised children aged 0–17 years using available data, a figure that they assert “severely underestimates” the actual scale of child institutionalisation. They suggest a handful of reasons for underdocumentation. For example, many institutions are unregistered, while under-reporting is widespread and many countries do not routinely collect or monitor data on institutionalised children. UNICEF23 also notes increasing child institutionalisation in settings of economic transition and severe poverty where monitoring capacity might be weaker. The UN’s World Report on Violence against Children1 cites an estimate of 8 million institutionalised children aged between 0 and 17 years, although it again notes that undercounting and limited monitoring suggests that the actual figure could be far higher.

Child institutionalisation has received the most attention in former Soviet states, where prevalence of this practice is thought to be greatest. UNICEF reports that in 2009, slightly more than 800 000 children younger than 18 years were reported to be living in institutions in central and eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS)—more than any other region.23 In 2002, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) sector survey24 of institutions in 20 eastern European and former Soviet countries estimated roughly 1.3 million institutionalised children younger than 17 years of age—more than twice the officially reported figure of 714 910. The report also notes that the 13% decrease in child institutionalisation in these countries since the fall of the Soviet Union fails to account for concurrent plummeting birth rates; the rate of institutionalisation per livebirth has risen by 3% in the 20 surveyed countries.24

The practice of child institutionalisation extends far beyond the former Soviet Union. Indeed, UNICEF reports that the country group with the second largest number of documented institutionalised children (just over 400 000) is the 34 most developed countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).23 Looking at the whole of Europe, researchers from the University of Birmingham compiled results from a survey of 33 European countries (excluding Russian-speaking countries) done by the WHO Regional Office for Europe and data from the UNICEF Social Monitor and documented a total of 43 842 (about 1.4 per 1000) children aged between 0 and 3 years housed in institutional care.25 The highest rates of early childhood institutionalisation was reported in Bulgaria (69 in 10 000 children), Latvia (58 in 10 000), and Belgium (56 in 10 000). France (2980) and Spain (2471) were both among the top five with the greatest absolute number of institutionalised children aged 0–3 years.25 In North American OECD states, child protection data are somewhat opaque. The US Department of Health and Human Services reports that on Sept 30, 2011, 9% (34 656) of the 400 540 children in public care in the USA were living in settings defined as institutions.26 Notably, some institutions represent small residential care homes for children with medical and psychological needs, quite distinct from large institutions described elsewhere. The figure provided also does not capture whether institutional placement was temporary or sustained. Despite scarce numbers, the report indicates that a significant institutionalisation problem remains in the USA.

In much of the rest of the world, UNICEF’s best available data are limited and uncertain. A 2009 report by UNICEF states that “numbers in the Latin America/Caribbean, Middle East/north Africa, eastern/southern Africa, and east Asia/Pacific regions are likely to be highly underestimated due to the absence of registration of institutional care facilities”, with rough estimates from official reported figures for each region ranging from 150 000 to 200 000. No estimates were made for west or central Africa and south Asia due to “lack of data”.24 However, various sources suggest substantial rates of institutionalisation in settings in which data are scarce. In Latin America and the Caribbean, one detailed public sector report has emerged from Brazil,27 where the government reported providing public funding to more than 670 institutions housing about 20 000 children as of 2004. Meanwhile, many other informal, private, and NGO institutions exist without government funding.27 In Asia, the Chinese Government has been building institutions for children orphaned by HIV/AIDS since 2004.15 News reports of a deadly fire in a private orphanage in central China have drawn attention to the existence of unregulated institutions in the country.28 In sub-Saharan Africa, where an estimated 90% of orphans and vulnerable children are cared for by extended family members,29 some reports note a rise in institutional care because family networks are overburdened and some donor funding for Africa’s perceived orphan crisis flows into institutional care facilities.30

Drivers of institutionalisation

Although worldwide data are scarce, findings from a 2005 EU survey indicate distinct drivers of institutionalisation across developed and less-developed countries. In EU states classified as developed (Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Portugal, and Sweden), abuse or neglect was the most prevalent reason for institutionalisation (69% of children), with a small proportion institutionalised owing to abandonment (4%) or disability (4%). However, in EU countries undergoing economic transition (Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Slovakia, and Turkey), abandonment was the most commonly reported reason for early-childhood institutionalisation (32%), followed by disability (23%), with a somewhat smaller proportion attributed to abuse or neglect (14%) or orphaning (6%). In both settings, roughly a quarter of children were institutionalised for “other” reasons.31 Notably, there might be much overlap between abandoned and disabled children in settings of stigma against disability, or in countries in which there is little structural support for families to meet special needs. Further data for causes of institutionalisation have emerged from Brazil, where a survey of 589 publicly funded institutions suggests a pattern similar to that seen in EU countries in economic transition. Abandonment, whether due to poverty (24%) or “other reasons” (18%), was the most frequently cited reason for institutionalisation, with lesser shares attributed to abuse or orphaning. Thus, what little data exist suggest that drivers of institutionalisation differ with societal variables such as poverty levels.

A diverse range of characteristics might make some children more vulnerable to institutionalisation than others. Notably, few children who are institutionalised fit the common cultural conception of an orphan—ie, a child who has lost both parents (what UNICEF defines as a double orphan). In 2003, data from 33 European countries suggested that 96% of institutionalised children had one or more living parents.31 However, many of these children might still meet the UN definition of orphanhood, which also includes single orphans (who have lost only one parent). In 2011, Belsey and Sherr32 provided an excellent discussion on the need for more careful differentiation of maternal versus paternal and single versus double orphans to characterise patterns of vulnerability.32 Importantly, most orphans are not institutionalised. Most of the 151 million orphans worldwide identified by UNICEF in 2011 remain in family care.33 In sub-Saharan Africa, even orphans who have lost both parents to AIDS (double orphans) receive care from extended family in 90% of cases.29 Nevertheless, despite a need for more and clearer data, orphans seem to remain more vulnerable to institutionalisation than do non-orphans in many settings, and various other markers of social and economic vulnerability could put children at further risk (panel 2).

Panel 2: Children at risk.

As evidenced by data for “drivers of institutionalisation” at national and regional levels, key risk factors for institutionalisation include poverty, loss of a parent, and the experience of child abuse. Yet various additional characteristics might put children at heightened risk, many representing markers of social inequality and vulnerability. UNICEF notes that the institutionalisation of millions of disabled children globally currently violates the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities22 whereas European mental health professionals call attention to the “overuse” of institutional care for mentally ill children in post-communist countries, as well as for many vulnerable European children without mental illness.25 In settings of stigma, children with HIV might be especially vulnerable. Additional data suggest higher rates of institutionalisation in Roma children from Romania24 and among children of African descent in Brazil.27 Institutionalisation remains a multifactorial problem affecting children from various backgrounds.

Developmental costs of institutionalisation

The prevalence of child institutionalisation worldwide is alarming in view of scientific evidence for the developmental risks of institutional care. For more than 80 years, observational studies have shown severe developmental delays in nearly every domain among institutionalised children compared with non-institutionalised controls. Contemporary meta-analyses have reported significant deficits in intelligence quotient (IQ),34 physical growth,35 and attachment36 among institutionalised and post-institutionalised children from more than 50 countries. The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP)16 provided the first RCT data comparing longitudinal outcomes among young institutionalised children (younger than 2 years at baseline) randomised into high-quality foster care (n=68) to outcomes among those remaining in Romanian state institutionalised care (n=68). The study is limited by its contextual specificity since it examines only institutions in Bucharest; nevertheless it offers the strongest evidence to date that institutional care has a causal effect on rates of developmental deficits and delays. This evidence counters critics who have long claimed that delays among institutionalised children merely reflect the risk factors (poverty, perinatal deprivation, and higher rates of illness) that resulted in their institutionalisation in the first place.37 As such, we will draw significantly upon its findings. In 2007, the English-Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study38 published detailed results through to 17 years of age on the developmental outcomes of 144 children who were adopted to the UK from Romanian institutions before the age of 2 years. The outcomes were compared with those of never-institutionalised domestic adoptees from the UK, with analysis indicating persistent developmental deficits associated with institutional care experienced past 6 months of age. Unfortunately, studies of individuals institutionalised as older children or adolescents are scarce (for a recent exception, see Whetten and colleagues39). This summary of key findings most clearly shows the effects of institutionalisation in early childhood (very early childhood institutionalisation). Yet, looking only at the first 3 years of life is highly illustrative given a broader child development literature describing the existence of sensitive periods in the first months and years of life, in which children are especially vulnerable to the vagaries of their environments (figure 1, figure 2).

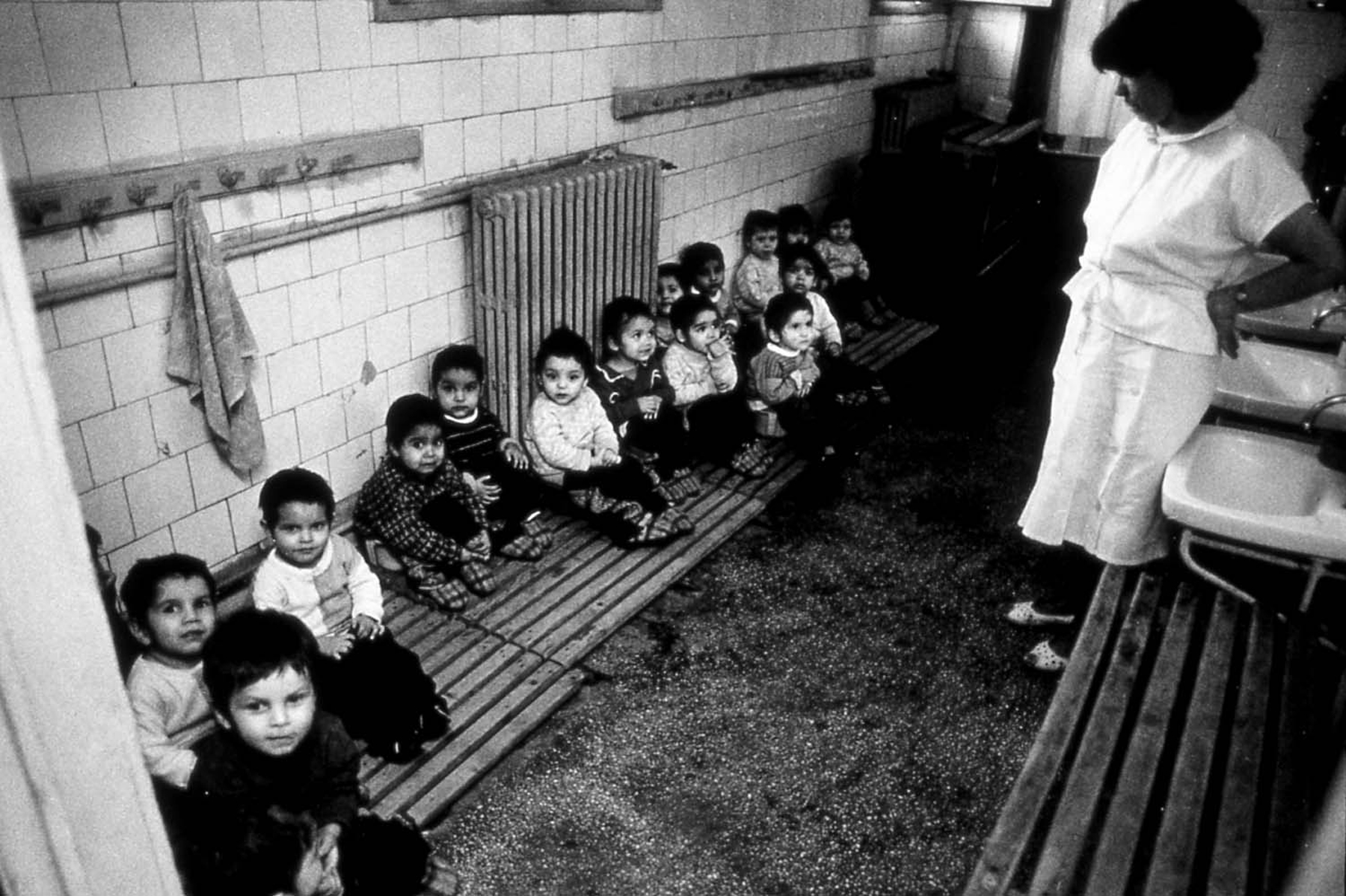

Figure 1: Children in a state-run institution in Bucharest, Romania.

Photograph courtesy of Michael Carroll.

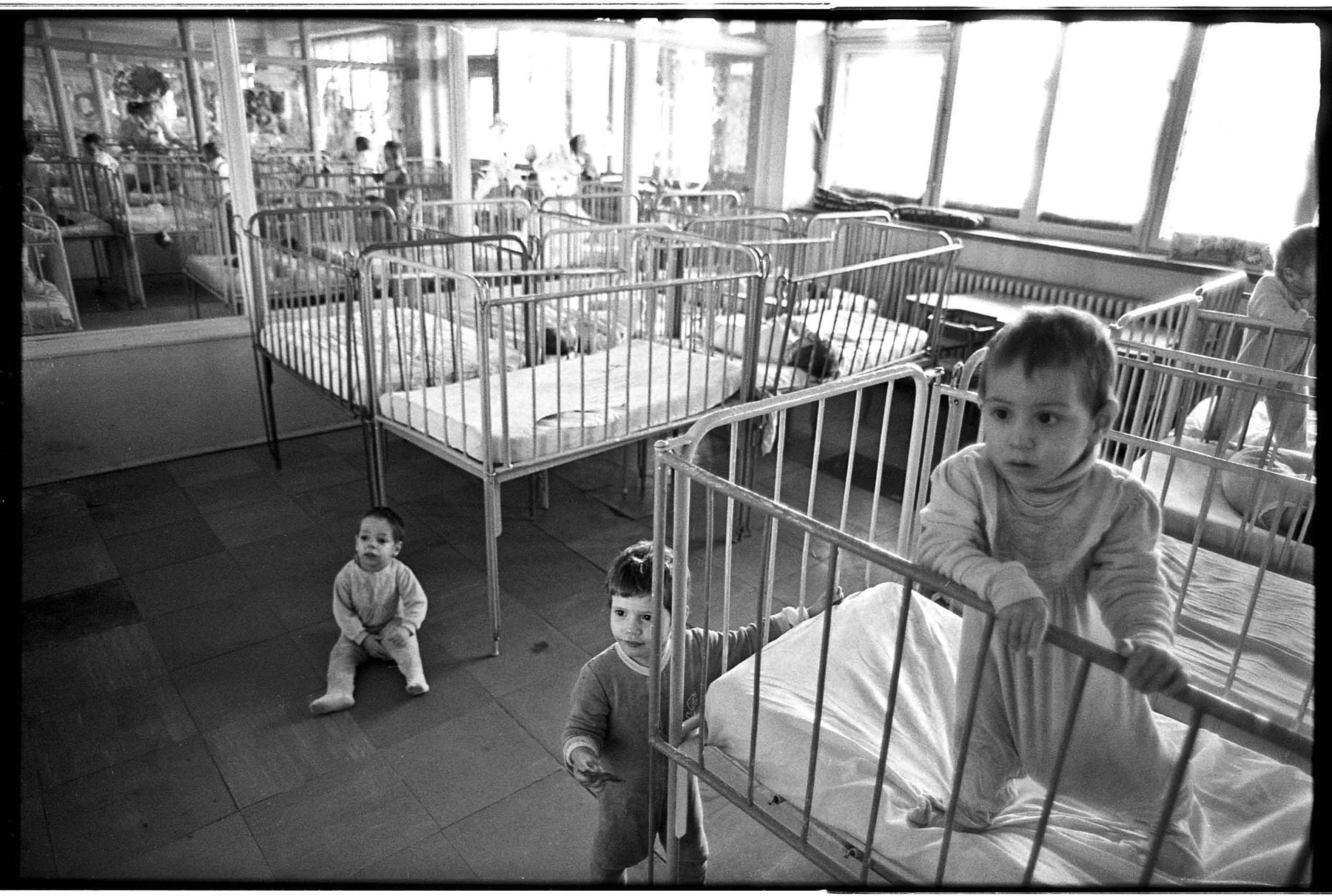

Figure 2: Sleeping quarters in a state-run institution in Bucharest, Romania.

Photograph courtesy of Michael Carroll.

Physical growth

Children in institutional care worldwide consistently show growth suppression, with specific deficits such as decreased weight, height, and head circumference.35,40 Proposed mechanisms include nutritional deficiency, prevalent illness, low birthweight, and adverse prenatal exposures. Notably, paediatric HIV infection, which can cause growth suppression if inadequately treated, is thought to be more prevalent among institutionalised children than among community-based peers in many settings.41 For instance, although figures likely in part reflect uneven detection, in 1990 following the fall of Romania’s Ceaușescu regime, 62.4% of all HIV infections in the country were in institutionalised children.42 The persistence of growth deficits among institutionalised children after controlling for variables such as disease burden and nutrition have led researchers to posit that children experience some amount of psychosocial growth suppression, or stunting; this phenomenon is thought to result from stress-mediated suppression of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor 1 (GF/IGF-1) induced by the institutional environment.43 Additionally, decreased head circumference among neglected children could arise from an excess of neural pruning in response to under-stimulation.44 Supporting this contention, the ERA study noted that duration of deprivation longer than 6 months among its 144 participants was associated with smaller head circumference independent of nutritional status.45 In 2007, a meta-analysis to quantify growth deficits reported a combined effect size of exposure to institutional care on height of d=−2.23 (95% CI −2.62 to −1.84) among 2640 children in regions including eastern Europe, South America, and Asia. However, the variable age of the children at assessment complicates interpretation. Within this same study, meta-analysis of a subset of 893 children (eight studies) removed from institutions before 3 years of age found that longer duration of institutionalisation was associated with more substantial height deficits (d=1.71, 95% CI 0.82–2.60).35 A review by Johnson estimated that infants and toddlers lose 1 month of linear growth for every 2–3 months spent in an institution.46

The ERA study47 noted that institutionalised Romanian adoptees had a mean head circumference and height that was more than 2 standard deviations below the mean for age-matched children in the general UK population, and 51% (55 of 108 children) of the adoptees were below the third percentile for weight at the time of entry to the UK. Longitudinally, more complete catch-up in height and weight was reported in children removed from institutions before 6 months of age compared with children removed after 6 months at age. Similarly, children in the younger than 6 month group showed significantly reduced head circumference at 11 years of age if they were undernourished (t[30]=10.12, p<0.001), but not if they were of normal weight (t[16]=1.74, p=0.10). By contrast, children older than 6 months had reduced circumference irrespective of nutritional status.45 At 15 years of age, a greater reduction in head circumference was significantly and independently related to duration of institutionalisation (n=196, b=−0.895, p<0.001).48 Using a randomised controlled trial design, the BEIP49 reported similar patterns in which placement of institutionalised children into foster care produced better recovery in height and weight than in head circumference. Among predictors of poorer catch-up in height and weight was removal from institutional care after 12 months of age (Z=−1.13[0.49], p<0.05 for height; Z=−1.79[0.57], p≤0.01 for weight). Further indicating the importance of these findings, Johnson and co-workers reported that greater catch-up in height was a significant independent predictor of a greater increase in verbal IQ.49

Cognitive functioning

IQ has been the most studied developmental outcome. In 2008, a meta-analysis assessed the effects of institutionalisation on IQ (or development quotient [DQ] for infants) in data from 42 studies of more than 3888 children in 19 countries. Institutional care, when compared with family-based care, had a significant combined effect size on IQ/DQ of d=1.10 (95% CI 0.84–1.36, p<0.01), with variable age at assessment. Mean IQ or DQ in children exposed to early institutional care was 84.40 (SD 16.79, n=2311, k=47), which was more than a full SD lower than the mean (104.20) of the age-matched controls (SD 12.88, n=456, k=16). Again, early age at time of exposure to institutional care was associated with greater effects on IQ or DQ of the children. Young children institutionalised during the first 12 months of life had significant deficits in IQ/DQ when compared with family-raised peers; this difference was also significantly larger than that observed when comparing children placed in institutions after 12 months with children raised in families ([d=1.10, k=24, and d=−0.01, k=9] Q[df=1]=13.00, p<0.001). Interestingly, longer total stay in institution was not associated with a significantly greater effect on IQ/DQ; at least in these studies, timing of exposure had a more significant effect on later cognitive outcomes than did length of exposure.34 Differences in caregiver–child ratios between the institutions were not particularly related to differences in effect sizes for IQ, even when comparing the worst subset of ratios to the best.34

Since 2008, additional data have proved consistent with earlier findings. The ERA study reported significantly lower IQ at time of adoption among adoptees to the UK from Romanian institutions compared with age-matched adoptees from within the UK. However, by age 11 years, post-institutionalised children adopted before 6 months of age had IQs statistically equivalent to never-institutionalised UK adoptees, whereas children removed after 6 months remained significantly behind.50

IQ at age 11 years was significantly and independently affected by duration of institutionalisation (F=29.15, p=0.001) and by undernutrition (F=9.58, p=0.002).45 The BEIP noted significantly marked cognitive deficits among institutionalised children at baseline (n=124, age <2 years), who had a mean DQ of 74.26, which was 29 points, or more than two standard deviations, below the mean for age-matched and sex-matched peers from families in the community (n=66, DQ=103.43, p<0.001).51 During follow-up, the study reported significant differences between children randomly assigned to remain in institutional care and those assigned into foster care, with an effect size of 0.62 at 42 months (t[116]=3.39, p=0.001) and 0.47 at 54 months (t[108]=2.48, p=0.015). While results at 8 years were less robust, probably because of movement of children between care settings, early foster care placement remained significantly predictive of a pattern of stable, typical IQ scores over time.52

Although in-depth examination of more detailed cognitive function testing is beyond the scope of this Review, many studies have documented a significant effect of institutionalisation on delays in specific domains of cognitive functioning including memory, attention, learning capacity and, perhaps most importantly, executive functions.38,53,54 Several groups reported persistent deficits in several domains of executive function despite removal from institutional care and placement into a family.54–57

Brain characteristics

Several investigators reported signs of decreased connectivity between areas supporting higher cognitive function among children exposed to early institutional care. A small diffusion tensor imaging study recorded significantly reduced fractional anisotropy in the left uncinate fasciculus of children placed in Romanian institutions at birth and removed between 17 and 60 months of age (five girls and two boys; mean age 9.7; range 2.6 years at testing) compared with family-reared, typically developing controls (four girls and three boys; mean age 10.7, range 2.8 years) in models including age and sex as a covariate when significant. Importantly, in an attempt to isolate the effects of institutional exposure per se from confounding risks, children were excluded from the post-institutionalised group for reasons including history of premature birth, prenatal or perinatal difficulties, major current or historical medical illnesses, or evidence of intrauterine alcohol or drug exposure. Despite the small size of this study and absence of age-matched and sex-matching of controls, it provides indication of deficits warranting further research.58 Another diffusion tensor imaging study reported more pervasive connectivity deficits in children previously institutionalised in Eastern Europe (n=10) or central Asia or Russia (n=7). Unfortunately, countries are not provided. Significantly decreased fractional anisotropy was noted in frontal, temporal, and parietal white matter (including parts of the uncinate and superior longitudinal fasciculi) compared with age-matched controls. Among other findings, white matter abnormalities (measured by reduced functional anisotropy) in the right uncinate fasciculus were significantly correlated with duration of institutionalisation (R=0.604, p=0.01) and with both inattention (R=0.499, p=0.004) and hyperactivity scores (R=0.504, p=0.004).59

Other studies used MRI to assess volumetric differences. One such study examined 31 adoptees who had mean age 10.9 years (SD 1.63) at the time of assessment who were adopted as toddlers from institutions in Romania, Russia, and China. Smaller superior–posterior cerebellar lobe volumes, and poorer performance on memory and executive function tasks were reported in these children compared with age-matched, typically developing controls.60 Meanwhile, reported effects on volume of the amygdala, a region supporting emotional learning and reactivity, have been inconsistent. Some investigators have reported significant increases in amygdala volume and activity in institutionalised children compared with never-institutionalised controls.61,62 Among these two studies, Tottenham and colleagues61 reported that an increase in amygdala volume was significantly associated with older age of deinstitutionalisation after adjusting for current age (r[31]=0.54, p<0.001), as was lower IQ (R[32]=0.34, p<0.05). The other study by Mehta and colleagues62 found that the overall larger amygdala size was dominated by effects on the right amygdala, and that longer period of institutionalisation was actually associated with smaller volume in the left amygdala.62 By contrast, the BEIP study63 reported no difference, whereas Hanson and colleagues64 noted a significant reduction in amygdala volume in institutionally deprived children. Further work is needed to clarify the potential role of this region in mediation of neurodevelopmental effects of deprivation.

Considering prospects for volumetric recovery after deprivation, BEIP researchers noted partial catch-up in white matter volume by age 11 years among children randomised into foster care compared with community controls; no white matter volume catch-up was seen in children assigned to standard institutional care. Foster care intervention did not seem to have an effect on total cortical volume and total grey matter. MRIs done once in children aged 8–11 years old showed reduced size compared with community controls, with no significant gains compared with children assigned to stay in institutions. These findings suggest that foster care intervention had a slightly beneficial effect on white but not grey matter.63

In addition to connectivity and size, some studies have investigated neural function. Tottenham and colleagues65 used functional MRI to compare 22 adoptees from east Asian and eastern European institutions to never-institutionalised controls aged about 9 years. When shown faces expressing fear, previously institutionalised children showed greater activity in the emotion-processing region of the amygdala (consistent with observations of structural change) and corresponding decreases in cortical regions devoted to higher perceptual and cognitive function. Changes in electroencephalogram findings in institutionalised children were recorded in the BEIP. Foster care placement had a beneficial effect on neural function, and it was reported that age at family placement made the difference between complete recovery and unabated impairment (panel 3).66

Panel 3: Sensitive periods in child development.

BEIP researchers used electroencephalograms (EEG) to compare institutionalised children with community controls before randomisation (baseline). They found that institutionalised children had significantly greater slow-frequency (theta) activity—associated with less developed brains—and less high-frequency (alpha/beta) activity indicative of neural maturation. By age 8 years, remarkable evidence of intervention timing effects emerged. Children in the foster care group who had been removed from institutions before the age of 2 years displayed a pattern of brain activity indistinguishable from the never-institutionalised group of community controls, with higher mature alpha activity and lower less mature theta activity. Children in the foster care group placed after 24 months of age had the opposite pattern, and indeed remained indistinguishable from children assigned to remain in institutional care-as-usual group (CAUG). These findings suggest that there might be a sensitive period for the development of neural structures underlying increased alpha power in the EEG signal. For figure see Vanderwert and colleagues.66

Social-emotional and psychological development

In the domain of social-emotional development, studies have largely focused on documenting unfavourable attachment patterns, which are believed to be associated with later psychopathology and behavioural difficulties. Increases in insecure or disorganised attachment (the style most predictive of later difficulties) and decreases in secure attachment (the most protective style) have been reported among children institutionalised in early childhood across a range of settings in countries including Greece,67 Spain,68 Ukraine,69 and Romania.70–72 The ERA study72 noted a particular predominance of an attachment style classified as insecure-other among formerly institutionalised children, a style characterized by atypical, non-normative, age-inappropriate behaviour (eg, strong approach and attachment maintenance with strangers, extreme emotional over-exuberance, nervous excitement, silliness, coyness, or excessive playfulness with parent and stranger alike). This insecure-other style was seen in 51.3% of children adopted out of Romanian institutions after 6 months of age, compared with only 38.5% of children adopted from institutions before 6 months of age and 16.3% of children adopted from within the UK. Follow-up at ages 6 and 11 years showed that insecure attachment significantly predicted rates of psychopathology and social service use.73 BEIP researchers reported that children randomised into foster care had significantly higher scores on a continuous measure of attachment security at age 42 months compared with children remaining in institutions. These higher scores were also seen in both girls (F[1,61]=31.2, p<0.001) and boys (F[1,61]=7.8, p=0.007). Secure attachment predicted significantly reduced rates of internalising disorders in both sexes. In girls, the protective effect of secure attachment fully mediated the effects of foster care intervention on rates of internalising disorders.74

Additional work has examined emergent psychopathology in post-institutionalised children. The ERA study75 reported that by mid-childhood, children who had been adopted into UK homes after 6 months of age frequently displayed what Rutter and colleagues75 term “institutional deprivation syndrome”, proposed to be a novel constellation of impairments including inattention or hyperactivity, cognitive delay, indiscriminate friendliness, and quasi-autistic behaviours. In a study of children still living in Romanian institutions, Ellis and colleagues76 noted that longer duration of institutionalisation was significantly associated with anxiety or affective symptoms (F[3,47]=6.49, p<0.01). A potential difference in patterns of psychological disorders might exist between boys and girls. BEIP researchers noted that at 54 months of age, girls in foster care had fewer internalising disorders (eg, depression and anxiety) than girls remaining in institutions (OR 0.17, p=0.006), whereas intervention effect on internalising disorders in boys was not significant (OR 0.47, p=0.150), despite significant effects on other measures of psychological wellbeing.74 Again, this reduction in anxiety and depression in girls was significantly mediated by attachment security, which predicted lower rates of internalising disorders in both sexes.77

Timing matters

Published work on early institutionalisation offers consistent evidence of developmental sensitive periods, or time periods in which experiences have especially marked and durable effects on longitudinal outcomes. Considering the mechanism of sensitive periods in brain development specifically, Fox and colleagues78 noted that human brains have their greatest total number of synapses in infancy. During development, human brains undergo a process of pruning unused connections, while confirming those most stimulated to specialise to environmental cues. The genome provides a timeframe in which networks must be confirmed to allow development to advance.79 Children who experience an abnormally small range of social and environmental stimulation might undergo excessive or aberrant neuronal pruning. This model explains repeated findings that children institutionalised during earlier months or removed into family care later experienced worse impairment.34,49,50,66 Unfortunately, deprivation during neurodevelopmental sensitive periods could have lifelong consequences. As discussed, early months are also important for children establishing patterns of attachment important for ongoing psychosocial development, with similarly foundational developmental processes likely occurring across many domains in the earliest months of life. Thus, early intervention is crucial.

New frontiers

Advances in cellular and molecular biology and neuroscience will push our understanding of the developmental consequences of early adversity into new arenas. In the BEIP, the effects of institutionalisation on cellular ageing were investigated, and DNA specimens were used to assess telomere length when children were between 6 and 10 years of age. Children with longer exposure to institutional care were reported to have significantly shorter telomeres in middle childhood.80 Another analysis reported that functional polymorphisms in brain-derived neurotrophic factor and serotonin transporter genes modified the effects of foster care placement on rates of indiscriminate behaviour, suggesting genetic underpinnings of a possible plasticity phenotype that enabled some children to benefit more from intervention.81 Time will afford greater understanding of how childhood adversity can change human DNA, and how genes change longitudinal effects of adversity.

Implications of findings

In this Review, we present evidence from a vast body of child development research suggesting that there is no appropriate place in contemporary child protection systems for the large, impersonal child-care institutions documented in many studies, at least for young children. Across diverse contexts, studies have shown that institutionalised children have delays or deficits in physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development. Developmental catch-up among fostered and adopted children suggest hope for recovery with targeted intervention, particularly in the earliest months and years of life. There is also reason to believe that a change towards developmentally informed protection strategies, although difficult, is possible in settings of limited resources and political resistance. BEIP researchers noted some gains in function among children randomly assigned to remain in state institutions who were later moved into a new Romanian state foster care system, even though state foster families received far less monitoring and support than did BEIP families.82 While replete with their own challenges and pitfalls, and by no means a panacea for vulnerable children, there is hope that foster care programmes in poor states undergoing economic and political transition can confer real benefits to children.

Yet, however clear the development literature, deinstitutionalisation remains politically and socially challenging and is fraught with pitfalls for children and professionals alike. Institutions also, in many settings, represent staging grounds for international adoption, a practice evoking passionate political support and detraction across national contexts and involving major social and economic interests. Institutions represent foci of economic interests aside from the adoption processes. In December, 1998, institutions employed a documented 41 200 Romanians; deinstitutionalisation therefore had profound economic and political effects on community, at times producing resistance (Bogdan S, Executive Director of Solidarite Enfants Roumains Abandonnes; Personal communication; Nov 12, 2014). Expert working groups with the WHO and European Council83 stress that deinstitutionalisation is not simply a matter of removing children from group homes, but a policy-driven process aimed at the transformation of child protection services to focus on family-level and community-level support. Experiences in Rwanda highlight this reality, with efforts to close down orphanages opened after the 1994 genocide requiring broad investment from the national government and UNICEF into the design of robust family-based child protection systems, and political will extending to the adoption of an orphan by the Prime Minister.84 In Ethiopia, deinstitutionalisation efforts have often been undertaken by NGOs; such decentralised approaches can open additional funding streams but also pose challenges around coordinating a cohesive national plan for non-institutional child protection.85 Other case studies from Uruguay, Chile, Argentina, Italy, and Spain similarly stress the complexity and uniqueness of this transformation in each socio-political environment.86

In view of the complexity of transforming social services, some argue that a moratorium on institutions will do more harm than good to vulnerable children, since some states will have few other options for child protection. Nevertheless, economic data make institutionalisation an undesirable option for poor states. Cost-effectiveness analyses from diverse contexts have reported that institutions are consistently more costly than family-based or community-based care, in terms of both direct outlays and indirect costs.21,87 In perhaps the most detailed report, researchers at the University of Natal, South Africa, compared kinship-based, community-based, and institutional models of orphan care in South Africa, and reported that “the most cost-effective models of care are clearly those based in the community”, while institutional models were, by comparison, “very expensive”.19 Furthermore, the aforementioned difficulties in dismantling existing structures makes institutionalisation a poor interim strategy for a state working towards a more develop mentally grounded child protection strategy—once opened, institutions are hard to close.83 No one is more affected by the challenges of deinstitutionalisation than the children who must hang on through difficult transitions. In view of the human and economic costs of institutional care, and the vast number of children within families needing services, institutionalisation appears to be a damaging and inadequate response to child protection needs, representing system failures in child sectors.

Tasks ahead

Despite some clear lessons from published work, there remains a challenging road ahead for researchers and practitioners interested in deinstitutionalisation, and for children in need of care. Among the most immediate barriers to knowledge and action towards deinstitutionalisation is the absence of consistent practices for documentation and monitoring of children in institutional care worldwide. Leadership is needed at an international level to craft consistent definitions and monitoring of standards, and encourage uptake of standards across NGO, UN, public, and private sectors. Additionally, to build upon findings compiled in this Review, further research is needed to explore the relative merits of various alternative care strategies that could be used to keep children out of institutions. A review of findings on this topic to date would represent a welcome addition to the scientific literature. In most contexts, alternative strategies will likely require the involvement of well-designed foster care and family reunification programmes, limited use of small group homes for specialised and transitional care, and responsible domestic and international adoption policies. Such areas of social policy are often hotly contested and shaped by many considerations beyond the child; however, comprehensive information about what is at stake for children might help practitioners to ensure that needs are met. Non-institutional strategies will require careful management with attention to screening, training, and monitoring of care providers, and are not without their own pitfalls.

In view of the high costs of deinstitutionalisation for children and societies, and the imperfection of alternative strategies, further work could focus on understanding the processes by which children lose access to safe family care and on implementation of preventive measures. Worldwide, particular attention must be paid to children in settings of conflict, community violence, and political instability; such settings might pose special challenges for those seeking to build the cohesive child protection strategies needed to avoid institutional responses. As explored by Betancourt and colleagues,88 appropriate responses should focus not only on the risks of trauma in conflict, but also on factors that create resilience among children, families, and communities. Intervention will prove particularly challenging in situations in which government protection has broken down and risk to child protection workers is great.

Notably, most countries currently institutionalise children with disabilities and other special medical or social needs at higher rates than other children. Relatively few studies have investigated the lives of institutionalised children with other special needs (for an exception, see the St Petersburgh-USA Orphanage Research Team89). As new efforts towards child deinstitutionalisation unfold, particular attention must be given to the needs of children with disabilities and special medical or social needs to ensure that plans are made to provide for those needs. Such attention will require assimilation of lessons from past experience (for a useful collection on efforts to advance community-based services for those with disabilities, see Johnson and Traustadottir90), careful data collection, and further research to document and provide for the needs of institutionalised children with disabilities.

Finally, findings supporting the view that children removed from institutional care and placed into families later in life (ie, during a sensitive period) experience especially persistent challenges suggest a need to develop new intervention strategies that can be used with older children. The incorporation of neuroscientific investigations into this research would provide insights into the effects of early adversity on neural function later in life, and into the global consequences of any neurodevelopmental differences on physical, cognitive, and emotional wellbeing.

Conclusion

We have analysed robust evidence about the often devastating developmental consequences of institutionalisation in early childhood. Studies also offer hope, showing that children placed into family care, including forms of care deliverable in settings of poverty and economic transition, can experience developmental recovery across most domains. Timing effects based on proposed sensitive periods show a need for urgent intervention and policy change; when it comes to removing children from harmful institutions, time is of the essence. Such changes in policy will require difficult tasks such as dismantling economically and socially entrenched structures, and building viable alternatives. With a robust evidence base to guide transformations, political will and social organisation are now needed to overcome remaining barriers to deinstitutionalisation.

Supplementary Material

Search strategy and selection criteria.

We searched multiple databases including PubMed and Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Library for articles published in English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. Emphasis was placed on articles published since 2005, although older relevant earlier articles were not excluded but interpreted accordingly. We used MeSH terms on the exposure of interest “orphanage” or “institutionalisation”, in combination with outcomes of interest “human development” (which included prenatal, perinatal, infant, child, and adolescent development) or “psychosocial development”, as well as numerous free search terms on outcomes including “IQ”, “intelligence”, “cognition”, “social”, “emotional”, “psychological”, “child development”, “child behaviour”, “neurodevelopment”, and others. Additional sources were drawn from the references of other articles included in the Review. When necessary, we contacted key authors to make sure that no relevant sources were missed.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by the Nelson Laboratory at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School provided a living stipend for AEB during the preparation and writing of the manuscript. CAB receives a grant from National Institutes of Mental Health (MH091363). The stipend was not contingent on the generation of a report, and had no influence on its writing or submission.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pinheiro PS. World report on violence against children. Geneva: United Nations Secretary-General’s Study On Violence Against Children, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boothby N, Balster RL, Goldman P, et al. Coordinated and evidence-based policy and practice for protecting children outside of family care. Child Abuse Negl 2012; 36: 743–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boothby N, Wessells M, Williamson J, et al. What are the most effective early response strategies and interventions to assess and address the immediate needs of children outside of family care? Child Abuse Negl 2012; 36: 711–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maholmes V, Fluke JD, Rinehart RD, Huebner G. Protecting children outside of family care in low and middle income countries: what does the evidence say? Child Abuse Negl 2012; 36: 685–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF. State of the World’s Children 2006. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UNICEF. The Paris principles: principles and guidelines on children associated with armed forces or armed groups. http://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/ParisPrinciples310107English.pdf (accessed Jan 19, 2015).

- 7.Chapin H Are institutions for infants really necessary? J Am Med Assoc 1915; LXIV: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldfarb W Infant rearing as a factor in foster home placement. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1944; 14: 162–66. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldfarb W Psychological privation in infancy and subsequent adjustment. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1945; 15: 247–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldfarb W Effects of psychological deprivation in infancy and subsequent stimulation. Am J Psychiatry 1945; 102: 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bowlby J Forty-four juvenile thieves: their characters and home-life. Int J Psychoanal 1944; 25: 19–52. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spitz RA. Hospitalism; an inquiry into the genesis of psychiatric conditions in early childhood. Psychoanal Study Child 1945; 1: 53–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.UN General Assembly. Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations Treaty Series 1989; 1577: 3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Save the Children UK. Keeping children out of harmful institutions: why we should be investing in family-based care. London: Save the Children UK; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Q, Li X, Kaljee LM, Fang X, Stanton B, Zhang L. AIDS orphanages in China: reality and challenges. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009; 23: 297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson CA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Romania’s abandoned children: deprivation, brain development and the struggle for recovery. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2012. http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2012.pdf (accessed Jan 19, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services. Section 1.2B.7: Placements. Child Welfare Manual. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desmond C, Gow J. The cost-effectiveness of six models of care for orphan and vulnerable children in South Africa. Durban, South Africa: Health Economics and HIV/AIDS Research Division, University of Natal, Durban, South Africa, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morrison L Ceausescu’s legacy: Family struggles and institutionalization of children in Romania. J Fam Hist 2004; 29: 168. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa M De-institutionalisation and quality alternative care for children in Europe: Lessons learned and the way forward. Eurochild Working Paper. 2006. http://www.bevaikunamu.lt/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/DI_Lessons_Learned.pdf (accessed Nov 23, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNICEF. Promoting the rights of children with disabilities. UNICEF Innocenti Digest 13. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.UNICEF. Progress for children: a report card on child protection. Geneva: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carter R Family matters: a study of institutional childcare in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. London: EveryChild; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Browne K, Hamilton-Giachritsis C, Johnson R, Ostergren M. Overuse of institutional care for children in Europe. BMJ 2006; 332: 485–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Health and Human Services. Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Report #19: FY 2011. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva E O Direito à Convivência Familiar e Comunitária: os Abrigos para Crianças e Adolescentes no Brasil. Brasília: Ipea/Conanda, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Associated Press. China orphanage fire kills At least 7 children. Huffington Post, Jan 4, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monasch R, Boerma JT. Orphanhood and childcare patterns in sub-Saharan Africa: an analysis of national surveys from 40 countries. AIDS 2004; 18 (suppl 2): S55–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richter LM, Norman A. AIDS orphan tourism: a threat to young children in residential care. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud 2010; 5: 217–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Browne KD, Hamilton-Giacritsis CE, Johnson R, Chou S. Young children in institutional care in Europe. Early Childhood Matters 2005; 105: 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belsey MA, Sherr L. The definition of true orphan prevalence: trends, contexts and implications for policies and programmes. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud 2011; 6: 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 33.UNICEF. The State of the World’s Children 2013: Children with Disabilities. Geneva: United Nations Children’s Fund; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ijzendoorn MH, Luijk MPCM, Juffer F IQ of children growing up in children’s homes: a meta-analysis on IQ delays in orphanages. Merrill-Palmer Q 2008; 54: 341–66. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F. Plasticity of growth in height, weight, and head circumference: meta-analytic evidence of massive catch-up after international adoption. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007; 28: 334–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van den Dries L, Juffer F, van Ijzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Fostering security? A meta-analysis of attachment in adopted children. Child Youth Serv Rev 2009; 31: 410–21. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, et al. Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project.Dev Psychopathol 2003; 15: 885–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rutter M, Beckett C, Castle J, et al. Effects of profound early institutional deprivation: an overview of findings from a UK longitudinal study of Romanian adoptees. Eur J Dev Psychol 2007; 4: 332–50. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whetten K, Ostermann J, Whetten RA, et al. , and the Positive Outcomes for Orphans (POFO) Research Team. A comparison of the wellbeing of orphans and abandoned children ages 6–12 in institutional and community-based care settings in 5 less wealthy nations. PLoS One 2009; 4: e8169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller L The growth of children in institutions. In: Preedy VR, ed. Handbook of growth and growth monitoring in health and disease. New York: Springer, 2012: 709–20. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richter LM, Sherr L, Adato M, et al. Strengthening families to support children affected by HIV and AIDS. AIDS Care 2009; 21 (suppl 1): 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hersh BS, Popovici F, Apetrei RC, et al. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Romania. Lancet 1991; 338: 645–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson DE, Gunnar MR. Growth failure in institutionalized children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2011; 76: 92–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nelson CA 3rd, Bos K, Gunnar MR, Sonuga-Barke EJS. The neurobiological toll of early human deprivation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2011; 76: 127–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, Kreppner J, et al. Is sub-nutrition necessary for a poor outcome following early institutional deprivation? Dev Med Child Neurol 2008; 50: 664–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson D The impact of orphanage rearing on growth and development. In: Nelson CA, ed. The effects of adversity on neurobehavioral development: Minnesota symposia on child psychology. New York: Erlbaum and Associates, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutter M, and the English and Romanian Adoptees (ERA) Study Team. Developmental catch-up, and deficit, following adoption after severe global early privation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1998; 39: 465–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Schlotz W, Rutter M VII.. Physical growth and maturation following early severe institutional deprivation: do they mediate specific psychopathological effects? Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2010; 75: 143–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson DE, Guthrie D, Smyke AT, et al. Growth and associations between auxology, caregiving environment, and cognition in socially deprived Romanian children randomized to foster vs ongoing institutional care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010; 164: 507–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beckett C, Maughan B, Rutter M, et al. Do the effects of early severe deprivation on cognition persist into early adolescence? Findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Child Dev 2006; 77: 696–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH; BEIP Core Group. The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48: 210–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nelson CA 3rd, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science 2007; 318: 1937–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Schlaak MF, et al. Neurodevelopmental effects of early deprivation in postinstitutionalized children. Child Dev 2010; 81: 224–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McDermott JM, Westerlund A, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA. Early adversity and neural correlates of executive function: implications for academic adjustment. Dev Cogn Neurosci 2012; 2 (suppl 1): S59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bos KJ, Fox N, Zeanah CH, Nelson CA 3rd. Effects of early psychosocial deprivation on the development of memory and executive function. Front Behav Neurosci 2009; 3: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Güler OE, Hostinar CE, Frenn KA, Nelson CA, Gunnar MR, Thomas KM. Electrophysiological evidence of altered memory processing in children experiencing early deprivation. Dev Sci 2012; 15: 345–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Loman MM, Johnson AE, Westerlund A, Pollak SD, Nelson CA, Gunnar MR. The effect of early deprivation on executive attention in middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013; 54: 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eluvathingal TJ, Chugani HT, Behen ME, et al. Abnormal brain connectivity in children after early severe socioemotional deprivation: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Pediatrics 2006; 117: 2093–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Govindan RM, Behen ME, Helder E, Makki MI, Chugani HT. Altered water diffusivity in cortical association tracts in children with early deprivation identified with Tract-Based Spatial Statistics (TBSS). Cereb Cortex 2010; 20: 561–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bauer PM, Hanson JL, Pierson RK, Davidson RJ, Pollak SD. Cerebellar volume and cognitive functioning in children who experienced early deprivation. Biol Psychiatry 2009; 66: 1100–06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, et al. Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Dev Sci 2010; 13: 46–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mehta MA, Golembo NI, Nosarti C, et al. Amygdala, hippocampaland corpus callosum size following severe early institutional deprivation: the English and Romanian Adoptees study pilot. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2009; 50: 943–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheridan MA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH, McLaughlin KA, Nelson CA 3rd. Variation in neural development as a result of exposure to institutionalization early in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012; 109: 12927–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanson JL, Nacewicz BM, Sutterer MJ, et al. Behavior problems after early life stress: contributions of the hippocampus and amygdala. Biol Psychiatry 2014; published online May 23. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Millner A, Gilhooly T, Zevin JD, Casey BJ. Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Dev Sci 2011; 14: 190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vanderwert RE, Marshall PJ, Nelson CA 3rd, Zeanah CH, Fox NA. Timing of intervention affects brain electrical activity in children exposed to severe psychosocial neglect. PLoS One 2010; 5: e11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vorria P, Papaligoura Z, Dunn J, et al. Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2003; 44: 1208–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Román M, Palacios J, Moreno C, López A. Attachment representations in internationally adopted children. Attach Hum Dev 2012; 14: 585–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dobrova-Krol NA, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer F. The importance of quality of care: effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on preschoolers’ attachment and indiscriminate friendliness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51: 1368–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Marcovitch S, Goldberg S, Gold A, et al. Determinants of behavioural problems in romanian children adopted in Ontario. Int J Behav Dev 1997; 20: 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fisher L, Ames EW, Chisholm K, Savoie L. Problems reported by parents of Romanian orphans adopted to British Columbia. Int J Behav Dev 1997; 20: 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Connor TG, Marvin RS, Rutter M, Olrick JT, Britner PA, and the English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team. Child-parent attachment following early institutional deprivation. Dev Psychopathol 2003; 15: 19–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rutter M, Colvert E, Kreppner J, et al. Early adolescent outcomes for institutionally-deprived and non-deprived adoptees. I: disinhibited attachment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007; 48: 17–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.McLaughlin KA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. Attachment security as a mechanism linking foster care placement to improved mental health outcomes in previously institutionalized children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012; 53: 46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, et al. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns: effects of institutional deprivation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2010: 1–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ellis BH, Fisher PA, Zaharie S. Predictors of disruptive behavior, developmental delays, anxiety, and affective symptomatology among institutionally reared Romanian children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004; 43: 1283–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McGoron L, Gleason MM, Smyke AT, et al. Recovering from early deprivation: attachment mediates effects of caregiving on psychopathology. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012; 51: 683–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fox SE, Levitt P, Nelson CA 3rd. How the timing and quality of early experiences influence the development of brain architecture. Child Dev 2010; 81: 28–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knudsen EI. Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J Cogn Neurosci 2004; 16: 1412–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Drury SS, Theall K, Gleason MM, et al. Telomere length and early severe social deprivation: linking early adversity and cellular aging. Mol Psychiatry 2012; 17: 719–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Drury SS, Gleason MM, Theall KP, et al. Genetic sensitivity to the caregiving context: the influence of 5httlpr and BDNF val66met on indiscriminate social behavior. Physiol Behav 2012; 106: 728–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fox NA, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2011; 52: 919–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mulheir G, Browne K. De-institutionalising and transforming children’s services: A Guide to Good Practice. Birmingham, UK: WHO Collaborating Centre for Child Care and Protection, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bloemen S Rwanda moves to close down children’s institutions and improve its childcare system. UNICEF News, 2012: 30. [Google Scholar]

- 85.FHI. Improving Care Options for Children in Ethiopia through Understanding Institutional Child Care and Factors Driving Institutionalization. Washington, DC: FHI & UNICEF, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 86.UNICEF. Children in Institutions: the Beginning of the End? Florence: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Browne K A European survey of the number and characteristics of children less than three years old in residential care at risk of harm. Adopt Foster 2005; 29: 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Betancourt TS, Khan KT. The mental health of children affected by armed conflict: protective processes and pathways to resilience. Int Rev Psychiatry 2008; 20: 317–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team. The effects of early social-emotional and relationship experience on the development of young orphanage children. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2008; 73: vii–viii, 1–262, 294–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Johnson K, Traustadottir R, eds. Deinstitutionalization and people with intellectual disabilities: in and out of institutions. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.