Abstract

Interleukin 7 (IL-7) protein has been reported to be important in the development of cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL) responses. However, other studies also support a partial Th2 phenotype for this cytokine. In an effort to clarify this unusual conflict, we compared IL-7 along with IL-12 (Th1 control) and IL-10 (Th2 control) for its ability to induce antigen (Ag)-specific CTL and Th1- versus Th2-type immune responses using a well established DNA vaccine model. In particular, IL-7 codelivery showed a significant increase in immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) levels compared to IgG2a levels. IL-7 coinjection also decreased production of Th1-type cytokine IL-2, gamma interferon, and the chemokine RANTES but increased production of the Th2-type cytokine IL-10 and the similarly biased chemokine MCP-1. In herpes simplex virus (HSV) challenge studies, IL-7 coinjection decreased the survival rate after lethal HSV type 2 (HSV-2) challenge compared with gD plasmid vaccine alone in a manner similar to IL-10 coinjection, whereas IL-12 coinjection enhanced the protection, further supporting that IL-7 drives immune responses to the Th2 type, resulting in reduced protection against HSV-2 challenge. Moreover, coinjection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env and gag/pol genes plus IL-12 or IL-7 cDNA enhanced Ag-specific CTLs, while coinjection with IL-10 cDNA failed to influence CTL induction. Thus, IL-7 could drive Ag-specific Th2-type cellular responses and/or CTL responses. These results support that CTLs could be induced by IL-7 in a Th2-type cytokine and chemokine environment in vivo. This property of IL-7 allows for an alternative pathway for CTL development which has important implications for host-pathogen responses.

Interleukin 7 (IL-7) is a bone marrow stromal cell-derived cytokine, known primarily as a pre-B-cell growth factor (12, 32). It has been reported that IL-7 can promote the differentiation of T cells and affect the viability or growth of early adult and fetal T cells (31, 47). IL-7 can also help promote the proliferation of T cells (30) and enhance cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte (CTL)- and lymphokine-activated killer activities (1, 19). In particular, IL-2-independent IL-7 activity is involved in enhancement of CTL responses (2, 4). In contrast, IL-12 induces Th1-type immune responses by eliciting the maturation of type 1 T cells from uncommitted Th0 cells, promoting NK activity, and maturating CTLs (9, 10, 24, 36). IL-12, a heterodimeric cytokine consisting of p40 and p35, is known to be produced mainly from macrophages and B cells. However, a major Th2-type cytokine, IL-10, a cytokine secreted mainly from Th2-type cells as well as B cells and monocytes (7, 8), has been known to inhibit cell-mediated immune responses by interfering with the activation of macrophages and NK cells, as well as IL-2- and gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-producing Th1 cells (16).

Recent evidence from many different studies indicates that induction of CTL responses is dependent upon the presence of Th1-type cytokines. We previously reported in our DNA vaccine studies that codelivery with plasmid DNAs expressing Th1-type cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, IL-12, and IL-18) enhances CD8-mediated CTL responses, while coinjection with plasmid DNAs expressing Th2-type cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10) has no effect on CTL induction (22, 23). The Th1-type cytokine coinjection also enhances antigen (Ag)-specific Th-cell proliferative responses in several DNA vaccine models (3, 23, 41, 42). It has been reported that Th1-versus Th2-type cellular responses are directly correlated with protection from pathogenic infections, including herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection and leshimaniasis (15, 39, 41, 42). Moreover, a CD8-mediated CTL response has also been reported to be an important immune correlate in protection against some viral infections (14, 17). However, Th1-type cellular responses and CD8-mediated CTL responses are generally thought to be related in their immune induction as well as in protective immunity.

In this study we observed that coinjection of IL-7 cDNA drove Ag-specific Th2-type cellular responses in a manner similar to IL-10 coinjection. Furthermore, similar to IL-12 coinjection, IL-7 codelivery enhanced Ag-specific CD8-mediated CTL responses in vivo. IL-7 and IL-10 coinjection also enhanced production of MCP-1 but decreased RANTES production, while IL-12 showed the opposite effect. Thus, this study supports that in vivo induction of CD8-mediated CTL responses by IL-7 is not dependent solely on Th1-type cytokine and chemokine environments and supports a unique role for this cytokine in T-cell biology.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female inbred BALB/c mice (4 to 6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, Ind.). Their care was under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, Md.) and protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

DNA plasmids.

The DNA vaccines pgD (pAPL-gD2) encoding HSV type 2 (HSV-2) gD protein, pCEnv expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Env protein, and pCGag/Pol expressing HIV-1 Gag/Pol protein were previously described (22, 34, 46). The PCR-generated IL-7 gene was cloned into pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). The expression vectors pCDNA3-IL-12 p35, pCDNA3-IL-12 p40, and pCDNA3-IL-10 were previously constructed in our laboratory (22, 23). Plasmid DNA was produced in bacteria and purified by double-banded CsCl preparations.

Reagents and cell lines.

HSV-2 strain 186 (a generous gift from P. Schaffer, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) was propagated in the Vero cell line (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.). Recombinant HSV-2 gD protein was obtained from G. H. Cohen and R. J. Eisenberg of University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. Human rhabdomyosarcoma and mouse mastocytoma P815 cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Recombinant vaccinia viruses (vMN462:env, VV:gag, and vSC8) were obtained from the National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program.

DNA inoculation of mice.

The quadriceps muscles of BALB/c mice were injected with pgD constructs formulated in 100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline and 0.25% bupivacaine-HCl (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) using a 28-gauge needle (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). pCDNA3-IL-7, pCDNA3-IL-10, pCDNA3-IL-12 p35, and pCDNA-IL-12 p40 expression cassettes were mixed with pgD, pCEnv, and pCGag/Pol plasmid solutions prior to injection.

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was performed as previously described (41, 42). The ELISA titers were determined as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution showing the same optical density (OD) as sera of naive mice. For the determination of relative levels of gD-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype, anti-IgG1 and -IgG2a conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Zymed, San Francisco, Calif.) were substituted for anti-IgG–HRP.

Th-cell proliferation assay.

The Th-cell proliferation assay was performed as previously described (42, 43).

Th1- and Th2-type cytokines and chemokines.

A 1-ml aliquot containing 6 × 106 splenocytes was added to wells of 24-well plates. Then, 1 μg of HSV-2 gD protein/ml was added to each well. After 2 days of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, cell supernatants were secured and then used for detecting levels of IL-2, IL-10, IFN-γ, RANTES, and MCP-1 using commercial cytokine kits (Biosource International, Camarillo, Calif., and R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) by adding the extracellular fluids to the cytokine- or chemokine-specific ELISA plates.

Intravaginal HSV-2 challenge.

Three weeks after the last DNA injection, animals were challenged intravaginally with 200 50% lethal doses (LD50) of HSV-2 strain 186 (7 × 105 PFU), the LD50 was previously determined (41). Before inoculation of the virus, the intravaginal area was swabbed with a cotton-tipped applicator (Hardwood Products Company, Guiford, Maine) soaked with 0.1 M NaOH solution and then cleaned with dried cotton applicators. Mice were then examined daily to evaluate survival rates.

CTL assay.

A 5-h 51Cr release assay was performed using vaccinia virus-infected target cells as previously described (22, 23). Briefly, splenocytes were stimulated for 2 days with concanavalin A at 2 μg/ml. The effector cells were then stimulated with relevant virus-vaccinia infected target cells, which were fixed with 0.1% glutaraldehyde, for 3 to 4 days. Vaccinia virus-infected target cells were prepared by infecting 3 × 106 p815 cells for 5 to 12 h at 37°C. The target cells were labeled with 100 μCi of Na251CrO4 per ml for 2 h and used to incubate the stimulated splenocytes for 5 h at 37°C. Supernatants were harvested, and radioactivity was counted on an LKB CliniGamma gamma counter. The percent specific lysis was determined as (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximum release − spontaneous release) × 100. Maximum release was determined by lysis of target cells in 1% Triton X-100. An assay was not considered valid if the value for the spontaneous release counts was in excess of 20% of the maximum release value.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done using the paired Student t test and analysis of variance. Values between different immunization groups were compared. P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

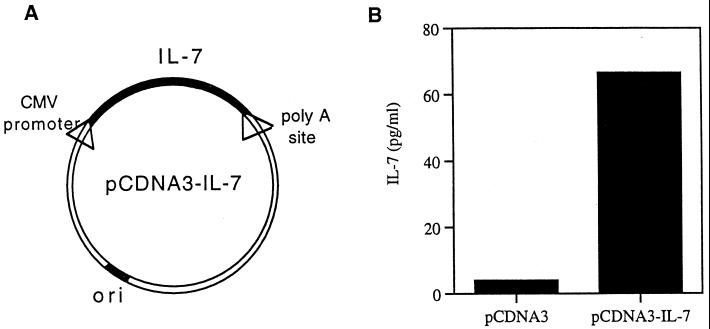

Construction of pCDNA3-IL-7 and its in vitro expression.

The IL-7 gene was subcloned into the pCDNA3 backbone (Fig. 1A). To confirm whether the pCDNA3-IL-7 plasmid construct expresses IL-7 in vitro, rhabdomyosarcoma cells were transfected with IL-7 plasmid constructs and then cell supernatants were obtained after 6 days of incubation. Supernatant was analyzed for the presence of IL-7 by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 1B, IL-7 was observed to be present at a concentration of 66.5 pg/ml in supernatants of cells previously transfected with IL-7 plasmid DNAs, compared to a background level of detection in the plasmid backbone control (pCDNA3).

FIG. 1.

(A) Construction of IL-7 expressing vector pCDNA3-IL-7. (B) In vitro expression of pCDNA3-IL-7 vector. Rhabdomyosarcoma cells were transfected with DNA vectors using Lipofectin transfection protocols. After 7 days of transfection, cell supernatant was obtained and then reacted with anti-IL-7 Ab, followed by addition of cell supernatant and then anti-IL-7—HRP conjugate for sandwich ELISA. On the basis of a standard curve, the OD was converted to the concentration of IL-7. CMV, cytomegalovirus.

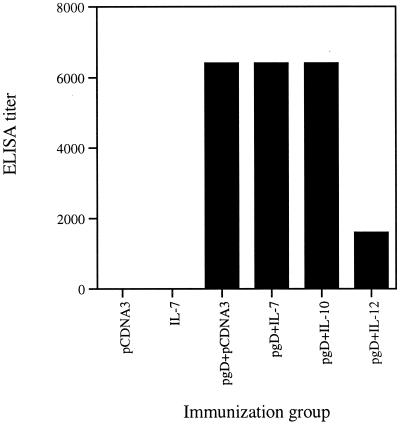

Antibody responses.

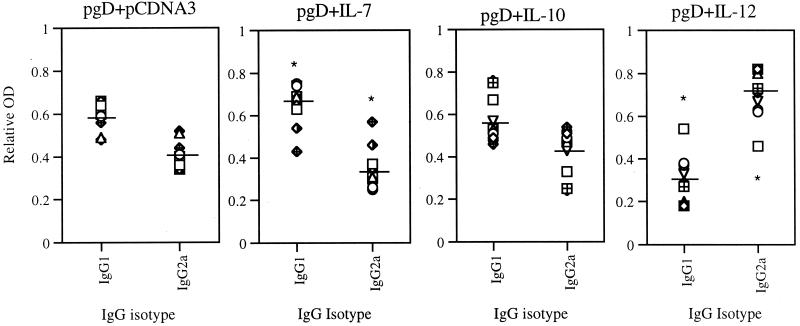

To determine if coinjection of gD DNA vaccines with expression vectors encoding IL-7, IL-10 (Th2 control), and IL-12 (Th1 control) might influence humoral immune responses against gD, sera obtained 2 weeks after the second DNA inoculation were tested in ELISA. As shown in Fig. 2, gD DNA vaccine induced systemic gD-specific IgG levels to a significant level. When the vaccine was coinjected with IL-7 and IL-10, we observed no modulation of gD-specific antibody (Ab) responses compared to those with the pgD vaccine alone. The ELISA titer of pgD plus pCDNA3, pgD plus IL-7, and pgD plus IL-10 was shown to be 6,400. However, coinjection with IL-12 cDNA decreased gD-specific Ab responses to levels significantly lower than those with pgD vaccine alone. However, there was some difference in the IgG isotype pattern (Fig. 3). It has been known that IgG1 and IgE are Th2-associated Abs, whereas IgG2a is a Th1-associated isotype Ab (44). After coimmunization with gD DNA vaccine plus IL-7 cDNA, Ag-specific IgG1 isotype production was enhanced to significantly higher levels than with pgD vaccine alone, while IgG2a isotype production was inhibited significantly more than with pgD vaccine alone. However, Th2-type cytokine IL-10 coinjection showed an IgG isotype pattern similar to that of the gD DNA vaccine alone, whereas IL-12 coinjection showed a pattern opposite to that with IL-7 coinjection. This reflects that IL-7 drives Ag-specific immune responses towards a Th2-type bias.

FIG. 2.

Levels of systemic gD-specific IgG in mice immunized with pgD vaccine plus IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs. Each group of BALB/c mice (n = 10) was immunized with 60 μg of pgD vaccine and/or 40 μg of IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNA at 0 and 2 weeks. Mice were bled 2 weeks after the second immunization, and then equally pooled sera were serially diluted to determine ELISA titer. The OD was measured at 405 nm.

FIG. 3.

Anti-gD IgG isotype patterns after IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNA coinjection. Each group of BALB/c mice (n = 10) was immunized with pgD vaccine (60 μg) plus IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs (40 μg) at 0 and 2 weeks. Mice were bled 2 weeks after the second immunization, and then each serum were diluted to 1:100 for reaction with gD. The OD was measured at 405 nm. Relative OD was calculated as each IgG subclass OD/total OD value. Horizontal lines represent the means (n = 10) of relative OD values of each mouse IgG subclass. ∗, Statistically significant at a P value of <0.05 using Student's t test, compared to each corresponding isotype of gD DNA vaccine alone.

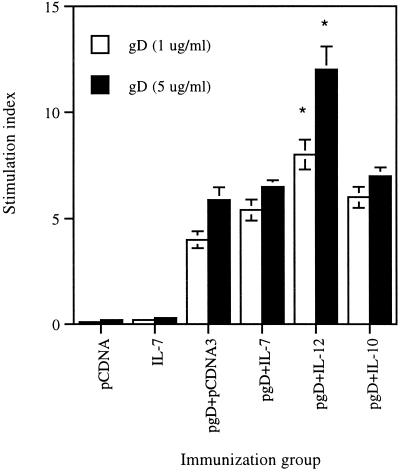

Th-cell proliferation responses.

Th cells play an important role in eliciting both humoral and cellular immune responses via expansion of Ag-stimulated B cells and expansion of CD8+ T cells, respectively. As a specific indicator of CD4 activation, T-cell proliferation was examined. To investigate if IL-7 possesses Ag-specific Th-cell proliferative activity, we coimmunized a pgD plasmid with plasmid DNAs encoding IL-7, IL-10 (Th2 control), or IL-12 (Th1 control). The gD-2 protein (1 and 5 μg/ml) was used for Ag specific stimulation of T cells collected from vaccinated animals. For a positive control, 5 μg of phytohemagglutinin (PHA) per ml was used as a polyclonal stimulator. As shown in Fig. 4, gD DNA vaccine-stimulated cells enhanced the Th-cell proliferative response over that with the negative control. Coinjection with IL-7 and IL-10 cDNAs had no significant influence over induction of gD-specific Th-cell proliferative responses. However, coinjection with IL-12 cDNA enhanced Th-cell proliferation levels significantly more than gD DNA vaccine alone or coimmunized with IL-7 or IL-10 plasmids.

FIG. 4.

Th-cell proliferation levels after in vitro stimulation with gD proteins. Each group of mice (n = 2) was immunized with 60 μg of pgD vaccine plus 40 μg of IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs at 0 and 2 weeks. Two weeks after the last DNA injection, two mice were sacrificed and spleen cells were pooled. Splenocytes were then stimulated with 1 and 5 μg of gD-2 proteins per ml and, as a positive control, with 5 μg of PHA per ml. After 3 days of stimulation, cells were harvested and counts per minute were counted. Samples were assayed in triplicate. The PHA control sample showed a stimulation index of 50 to 60. The experiments were repeated two more times with similar results. ∗, Statistically significant at a P value of <0.05 using the paired Student t test, compared to pgD vaccine alone. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Levels of Th1 and Th2 cytokines.

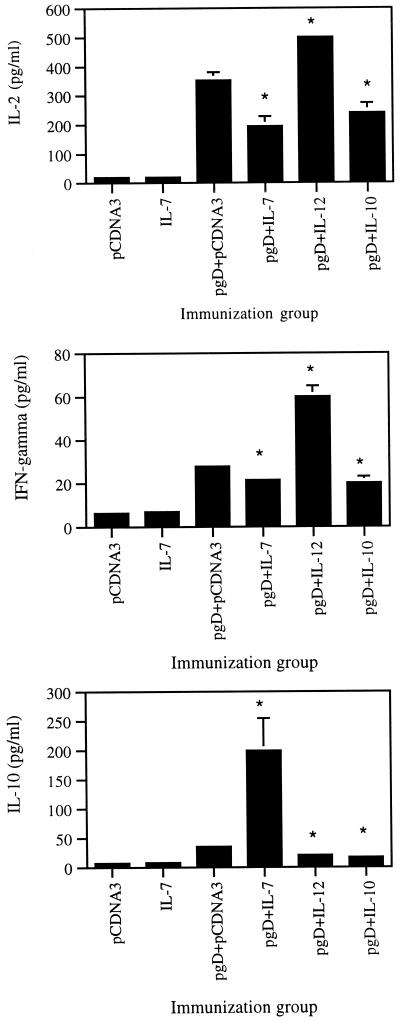

Levels of Th1 (IL-2 and IFN-γ) versus Th2 (IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10) cytokines have been a major parameter for our understanding of the polarization of immune responses. Th1 immune responses are thought to drive induction of cellular immunity, whereas Th2 immune responses preferentially drive humoral immunity. We examined the effects of coinjection of gD DNA vaccine with and without IL-7 cDNA along with plasmid DNAs expressing IL-10 (Th2 control) and IL-12 (Th1 control) on production of IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ. As shown in Fig. 5, the gD DNA vaccine enhanced IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ production in an Ag-dependent fashion compared to the negative control. However, IL-7 and IL-10 coinjection decreased IL-2 and IFN-γ production from splenocytes after stimulation in vitro with gD Ag, while only IL-7 coinjection enhanced IL-10 production significantly more than pgD vaccine alone. In contrast, IL-12 coinjection showed the opposite effect in that IL-12 enhanced IL-2 and IFN-γ production but inhibited IL-10 production. This finding further supports that IL-7 has similarity to a Th2-type cytokine.

FIG. 5.

Levels of production of IL-2, IL-10, and IFN-γ from splenocytes in mice immunized with pgD plus IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs. Each group of mice (n = 2) was immunized with 60 μg of pgD vaccine and/or 40 μg of IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs at 0 and 2 weeks. Two weeks after the last DNA injection, two mice were sacrificed and spleen cells were pooled. Splenocytes were stimulated with 1 μg of gD-2 proteins/ml for 2 days. Samples were assayed in triplicate. Bars represent mean released cytokine concentrations and standard deviations. The experiments were repeated two more times with similar results. ∗, Statistically significant at a P value of <0.05 using the paired Student t test, compared to pgD vaccine alone.

Th1 versus Th2 chemokines.

Recently, there have been reports that β chemokines (C-C type), including RANTES, MIP-1α, and MCP-1, play a role in differentiating immune responses to Th1 and Th2 types. The relationship of Th1- versus Th2-type cytokine production to β-type chemokine production in vivo is unknown. We investigated the levels of chemokines (RANTES and MCP-1) induced by coinjection with pgD plus IL-7, IL-10 (Th2 control), and IL-12 (Th1 control) cDNAs. As shown in Fig. 6, gD DNA vaccine alone enhanced production of RANTES and MCP-1 in an Ag-specific manner. Coinjection with IL-7 and IL-10 enhanced MCP-1 production significantly more than pgD vaccine alone. In contrast, RANTES production was dramatically inhibited by IL-7 and IL-10 coinjection. Coinjection with IL-12, however, showed the opposite effect on production of RANTES and MCP-1. This suggests that RANTES production is enhanced by Th1-type cytokine coinjection but decreased by Th2-type cytokine coinjection, whereas MCP-1 production is up-regulated by Th2-type cytokine coinjection, but inhibited by Th1-type cytokine coinjection. IL-7, in this context, clearly behaved more similarly to a Th2-type cytokine than to a Th1-type cytokine.

FIG. 6.

Levels of production of RANTES and MCP-1 from splenocytes in mice immunized with pgD plus IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs. Each group of mice (n = 2) was immunized with 60 μg of pgD vaccine plus 40 μg of IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNA at 0 and 2 weeks. Two weeks after the last DNA injection, two mice were sacrificed and spleen cells were pooled. Splenocytes were stimulated with 1 μg of gD-2 proteins/ml for 2 days. Samples were assayed in triplicate. Bars represent mean released chemokine concentrations and standard deviations. The experiments were repeated two more times with similar results. ∗, statistically significant at a P value of <0.05 using the paired Student t test, compared to gD DNA vaccine alone.

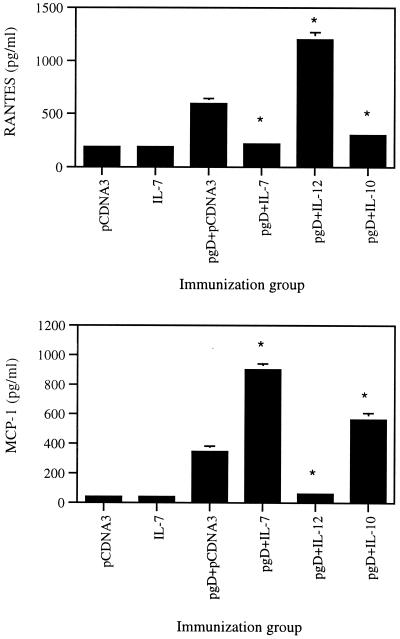

Effects on protection against HSV-2 challenge.

Th1-type cellular responses are considered important for enhanced protection from HSV-2 challenge (27, 41, 42). In contrast, Th2-type cellular responses are suggested to bias animals to be more susceptible to HSV infection (41). To investigate whether IL-7 drives Ag-specific Th1- or Th2-type cellular responses, we coimmunized mice with gD DNA vaccine plus plasmid DNAs expressing IL-7, IL-10 (Th2 control), and IL-12 (Th1 control). The mice were then challenged intravaginally with 200 LD50 of HSV-2 (strain 186). As shown in Fig. 7, IL-7 and IL-10 (Th2 control) coinjection made animals exhibit increased susceptibility for HSV-2 infection compared to pgD vaccine alone. However, coinjection with IL-12 as a Th1-type control protected all mice from the lethal challenge with HSV-2, decreasing their susceptibility to lethal challenge.

FIG. 7.

Protection of mice from HSV-2 challenge by IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNA coinjection. Mice (n = 8 per group) were immunized with pgD vaccines (60 μg) plus IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs at 0 and 2 weeks. After 3 weeks following the second injection, mice were challenged intravaginally with 200 LD50 of HSV-2 strain 186 and then checked for 30 days to determine survival rates. □, pCDNA3; ◊, IL-7; ○, pgD plus pCDNA3; ▵, pgD plus IL-7; ⊞, pgD plus IL-12; ●, pgD plus IL-10. ∗, statistically significant at a P value of 0.05 using analysis of variance, compared to pgD plus IL-12.

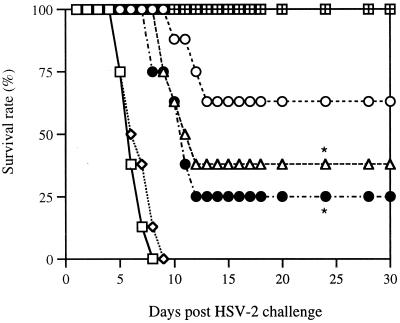

CTL responses.

To determine whether IL-7 could enhance Ag-specific CTL activity in vivo, we used a well-established CTL model system of HIV-1 constructs encoding Env and Gag/Pol, as a lack of CTL responses against gD in BALB/c mice has been reported previously (6, 11, 28, 42). We coimmunized with pCEnv and pCGag/Pol plus IL-7, IL-10 (Th2 control), and IL-12 (Th1 control) plasmid DNAs. As shown in Fig. 8A, coinjection with pCEnv plus IL-7 cDNA enhanced CTL activities to 28% (50:1) and 17% (25:1), significantly higher than pCEnv alone. In contrast, coinjection with pCEnv plus IL-10 cDNA showed no effect on CTL induction. On the other hand, a dramatically enhanced CTL activity was observed with pCEnv plus IL-12 coinjection. Similarly, coinjection with pCGag/Pol plus IL-7 cDNA enhanced CTL activities to 29% (50:1) and 26% (25:1), significantly higher than pCGag/Pol alone (Fig. 8B). In contrast, coinjection with pCGag/Pol plus IL-10 cDNA showed no effect on CTL induction. However, a dramatically enhanced CTL activity was observed in pCGag/Pol plus IL-12 coinjection. This finding again confirms that IL-7 enhances Ag-specific CD8-mediated CTL responses in an Ag-specific manner.

FIG. 8.

Induction of CTL activity after coinjection with IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs. Each group of BALB/c mice (n = 2) was immunized with pCEnv (A) or pCGag/Pol (B) vaccine (60 μg) plus 40 μg of IL-7, IL-10, and IL-12 cDNAs at 0 and 2 weeks. Two weeks after the last DNA injection, mice were sacrificed and spleen cells were pooled. The CTL assay measuring the chromium release from specific and irrelevant vaccinia virus-infected targets was performed on splenocytes harvested from immunized mice with in vitro stimulation induced on the splenocytes. Effector/target ratios were chosen from 50:1 to 12.5:1. Recombinant vaccinia viruses vMN462, VV, and vSC8 were used to infect p815 to prepare specific and irrelevant target cells, respectively. The experiments were repeated three times with similar results. □, pCDNA3; ◊, vaccine plus pCDNA3; ○, vaccine plus IL-12; ▵, vaccine plus IL-7; ⊞, vaccine plus IL-10.

DISCUSSION

The pathological significance of Th1- versus Th2-type immune responses has been observed in several pathogenic infection models (13, 15, 37, 39, 41, 48). In these models, susceptibility studies combined with use of cytokine subsets have suggested that Th1-type responses enhance protection from pathogenic infections while Th2-type responses increase susceptibility. It has been known that Th1 cells enhanced inflammatory responses and up-regulate CTL activity. For example, coinjection with Th1-type cytokine IL-2, -12, -15, and -18 cDNAs enhances Ag-specific T-cell proliferation and CTL responses (18, 22, 23). However, Th2-type cytokines IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 have shown no influence over Ag-specific CTL induction in vivo (23). A prototypic Th2-type cytokine, IL-4, plays a key role in suppressing Th1-type cytokine expression and CTL functions of activated CD8+ T cells in vivo and in vitro (5, 33, 40).

In this study, we observed that when codelivered in a DNA form, IL-7 as well as IL-10 (Th2 control) had little influence over Ab titers, whereas IL-12 coinjection (Th1 control) inhibited overall Ab induction. This suggests that IL-7 has little stimulatory effect on humoral responses. However, there was a shift from the IgG2a to the IgG1 isotype with coinjection with IL-7, supporting that IL-7 drives Ag-specific immune responses in somewhat of a Th2 phenotype. Similarly, IL-7 coinjection displayed minimal effects on Th-cell proliferative responses, in a manner similar to a Th2 cytokine control, IL-10. However, IL-12 coinjection dramatically enhanced Th-cell proliferative responses. This suggests that IL-7 has little significant effect on induction of Th-cell proliferation in this vaccine model. This observation is in line with the cytokine production profile we observed. IL-7 coinjection enhanced IL-10 production but inhibited IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion, further confirming that IL-7 has aspects of a Th2 bias. However, IL-10 coinjection inhibited IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion as well as its own production. In contrast, IL-12 coinjection showed the opposite effects. This supports that IL-7 is capable of activating T cells which generate a Th2-type cytokine (IL-10) but negatively influences T cells secreting some Th1-type cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ). In this case, this activity cannot be attributed to backbone CpG motifs, as mixing of gD plasmids with pCDNA3 vector did not demonstrate a similar immune modulatory function or change the challenge outcome (data not shown).

We recently reported that coinjection with a Th1-type cytokine, IL-12, enhances production of RANTES and MIP-1α but suppresses MCP-1 production (42). In contrast, a subunit vaccine consisting of a strong Th2 inducer enhanced production of MCP-1 but suppressed production of RANTES and MIP-1α (43). This indicates that there could be different T cells generating either Th1- or Th2-type chemokines, supporting that chemokine types are also divided into Th1 versus Th2 types. Recent studies also support that chemokine receptors mark T-cell subsets and that chemokines may be involved in the generation of Ag-specific Th1 versus Th2 immune responses (21, 38). Moreover, Th1-cell-mediated ocular inflammatory disease caused by HSV infection was ameliorated by injection with anti-MIP-1α but not anti-MCP-1 (45), again indicating that MIP-1α and MCP-1 might be related to induction of Th1- and Th2-type cell-mediated immune responses, respectively. In this study, we also observed that IL-7 coinjection enhanced production of MCP-1 but inhibited RANTES production from splenocytes after in vitro stimulation with gD, which was correlated with production patterns of Th1-type (IL-2 and IFN-γ) and Th2-type (IL-10) cytokines. This indicates that MCP-1 might be involved in induction of strong Th2-type cellular immune responses. This finding is compatible with previous studies in which coinjection with MCP-1 was found to drive Th2-biased immune responses (20, 26). This is also supported by our unpublished observation that MCP-1 cDNA coinjection resulted in increased susceptibility to HSV-2 infection. Kim and others (21) observed that coinjection with MCP-1 cDNA enhanced Ag-specific CTL responses, indicating that MCP-1 might behave like IL-7 in that it drives both Ag-specific Th2 immune responses and CTL responses in vivo. RANTES might be involved in the promotion of Th1-type responses. This is supported by our unpublished observation that coinjection with RANTES cDNAs enhances protection from HSV-2 challenge. Taken together, these observations indicate that it is likely that RANTES is a Th1-type chemokine while MCP-1 is a Th2-biased chemokine with an unusual effect on CTL competence.

In HSV studies, IL-12 drives Ag-specific Th1-type cellular responses and enhances protective immunity against lethal HSV infection (41, 42). In contrast, Th2-type cellular immunity induced by Th2-type cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10 results in increased susceptibility to HSV infection. It has further been reported that Th1-type CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells, are responsible for protecting animals from HSV challenge (27, 29, 42, 49). In this study, IL-7 cDNA coinjection increased susceptibility to HSV-2 infection in a manner similar to coinjection with IL-10 cDNAs, whereas IL-12 cDNA coinjection increased protection from viral infection. This is in line with a previous finding that administration of recombinant IL-7 protein results in an aggravation of Schistosoma mansoni infection and its related diseases (48). In the S. mansoni infection model, Th1 responses are believed to be protective, while Th2 responses benefit the pathogen at the expense of the host. In particular, IL-7 coinjection enhanced Ag-specific CTL activity in vivo. However, IL-10 coinjection had no effects on induction of CTL function, while IL-12 coinjection enhanced CTL function as expected (23). This reflects that when codelivered with antigen in a DNA form, IL-7 has the ability to enhance Ag-specific CTL functions in vivo. It has previously been reported that IL-7 promotes proliferation of CD8+ T cells (2) and augments in vitro differentiation of memory CTL precursors to effector CTLs as well as in vitro CTL activity (25, 35). Our findings support that IL-7 enhances Ag-specific CTL functions in particular in vivo, where Th2-type cytokine and chemokine environments are driven. This result suggests that the quality of the CTLs induced by IL-7 should be further examined.

In conclusion, IL-7 codelivered with Ag in a DNA form drives Ag-specific Th2-type responses. IL-7 also enhances Ag-specific CTL functions in vivo. This supports that CTL induction is not dependent solely on Th1-type cytokine environments. This finding also suggests that the quality of CTL response could be markedly different in this Th2-type system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. H. Cohen and R. J. Eisenberg for providing HSV-2 gD (306t). We also thank P. Schaffer and R. Jordan for providing a stock of HSV-2 for this study. J. I. Sin thanks S. Specter for his advice on this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderson M R, Sassenfeld H M, Widmer M B. Interleukin 7 enhances cytolytic T lymphocyte generation and induces lymphokine-activated killer cells from human peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 1990;172:577–587. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.2.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carini C, Essex M. Interleukin 2-independent interleukin 7 activity enhances cytotoxic immune response of HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:121–130. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow Y H, Chiang B L, Lee Y L, Chi W K, Lin W C, Chen Y T, Tao M H. Development of Th1 and Th2 populations and the nature of immune responses to hepatitis B virus DNA vaccines can be modulated by codelivery of various cytokine genes. J Immunol. 1998;160:1320–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conlon P J, Morrissey P J, Norday R P, Grabstein K H, Prickett K S, Reed S G, Goodwin R, Cosman D, Namen A E. Murine thymocytes proliferate in direct response to interleukin-7. Blood. 1989;74:1368–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Croft M, Carter L, Swain S L, Dutton R W. Generation of polarized antigen-specific CD8 effector populations: reciprocal action of interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-12 in promoting type 2 versus type 1 cytokine profiles. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1715–1728. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz P E, Khalil P L, Dryden T D, Chiou H C, Fink P S, Berberich S J, Bigley N J. A novel immunization method to induce cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses (CTL) against plasmid-encoded herpes simplex virus type-1 glycoprotein D. Vaccine. 1999;17:1091–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Waal-Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor C G, de Vries J. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiorentino D F, Bond M W, Mosmann T R. Two types of mouse T helper cell. IV. Th2 clones secrete a factor that inhibits cytokine production by Th1 clones. J Exp Med. 1989;170:2081–2095. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.6.2081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gately M K, Wolitzky A G, Quinn P M, Chizzonite R. Regulation of human cytolytic lymphocyte responses by interleukin-12. Cell Immunol. 1992;143:127–142. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(92)90011-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Germann T, Gately M K, Schoenhaut D S, Lohoff M, Mattner F, Fischer S, Jin S-C, Schmitt E, Rude E. Interleukin-12/T cell stimulating factor, a cytokine with multiple effects on T helper type 1 (Th1) but not on Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1762–1770. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghiasi H, Cai S, Slanina S, Nesburn A B, Wechsler S L. Vaccination of mice with herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D DNA produces low levels of protection against lethal HSV-1 challenge. Antiviral Res. 1995;28:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00045-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin R G, Lupton S, Schmierer A, Hjerrild K J, Jerzy R, Clevenger W, Gillis S, Cosmann D, Namen A E. Human interleukin 7: molecular cloning and growth factor activity on human and murine B-lineage cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:302–306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.1.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haak-Frendscho M, Brown J F, Iizawa Y, Wagner R D, Czuprynski C J. Administration of anti-IL-4 monoclonal antibody 11B11 increases the resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection. J Immunol. 1992;148:3978–3985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser C, Zipprich F, Leblond I, Wirth S, Hugin A W. Protective immunity from naive CD8+ T cells activated in vitro with MHC class I binding immunogenic peptides and IL-2 in the absence of specialized APCs. J Immunol. 1999;163:330–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis. Evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu D H, Moore K W, Spits H. Differential effects of interleukin-4 and -10 on interleukin-2 induced interferon-gamma synthesis and lymphokine-activated killer activity. Int Immunol. 1992;4:563–569. doi: 10.1093/intimm/4.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu S C, Obeid O E, Collins M, Iqbal M, Chargelegue D, Steward M W. Protective cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses against paramyxoviruses induced by epitope-based DNA vaccines: involvement of IFN-gamma. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1441–1447. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.10.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasaki A, Stiernholm B J, Chan A K, Berstein N L, Barber B H. Enhanced CTL responses mediated by plasmid DNA immunogens encoding costimulatory molecules and cytokines. J Immunol. 1997;158:4591–4601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jicha D L, Mule J J, Rosenberg S A. Interleukin-7 generates anti-tumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes against murine sarcomas with efficacy in cellular adoptive immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1511–1515. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpus W J, Kennedy K J, Kunkel S L, Lukacs N W. Monocyte chemotactic protein 1 regulates oral tolerance induction by inhibition of T helper cell 1-related cytokines. J Exp Med. 1998;187:733–741. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J J, Nottingham L K, Sin J I, Tsai A, Morrison L, Dang K, Hu Y, Kazahaya K, Bennett M, Dentchev T, Wilson D M, Chalian A A, Boyer J D, Agadjanyan M G, Weiner D B. CD8 positive T-cells influence antigen-specific immune responses through the expression of chemokines. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1112–1124. doi: 10.1172/JCI3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J J, Ayyavoo V, Bagarazzi M L, Chattergoon M A, Dang K, Wang B, Boyer J D, Weiner D B. In vivo engineering of a cellular immune response by co-administration of IL-12 expression vector with a DNA immunogen. J Immunol. 1997;158:816–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J J, Trivedi N N, Nottingham L, Morrison L, Tsai A, Hu Y, Mahalingam S, Dang K, Ahn L, Doyle N K, Wilson D M, Chattergoon M A, Chalian A A, Boyer J D, Agadjanyan M G, Weiner D B. Modulation of amplitude and direction of in vivo immune responses by co-administration of cytokine gene expression cassettes with DNA immunogens. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1089–1103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199803)28:03<1089::AID-IMMU1089>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewick R M, Clark S C, Chan S, Loudon R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchieri G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulator factor (NKSF): a cytokine with multiple biologic effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–845. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kos F J, Mullbacher A. IL-2-independent activity of IL-7 in the generation of secondary antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses in vitro. J Immunol. 1993;150:387–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lukacs N W, Chensue S W, Karpus W J, Lincoln P, Keefer C, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L. C-C chemokines differentially alter interleukin-4 production from lymphocytes. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1861–1868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manickan E, Rouse R J D, Yu Z, Wire W S, Rouse B T. Genetic immunization against herpes simplex virus. Protection is mediated by CD4+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1995;155:259–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin S, Moss B, Berman P W, Laskey L A, Rouse B T. Mechanisms of antiviral immunity induced by a vaccine virus recombinant expressing herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D: cytotoxic T-cells. J Virol. 1987;61:726–734. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.3.726-734.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milligan G N, Bernstein D I. Analysis of herpes simplex virus-specific T cells in the murine female genital tract following genital infection with herpes simplex virus type 2. Virology. 1995;212:481–489. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrissey P J, Goodwin R G, Nordan R P, Anderson D, Grabstein K H, Cosman D, Sims J, Lupton S, Acres B, Reed S G. Recombinant interleukin-7, pre-B cell growth factor, has costimulatory activity on purified mature T cells. J Exp Med. 1989;169:707–716. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray R, Suda T, Wrighton N, Lee F, Zlotnick A. Interleukin-7 is a thymocyte growth and maintenance factor for mature and immature thymocytes. Int Immunol. 1989;1:526–531. doi: 10.1093/intimm/1.5.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Namen A E, Lupton S, Hjerrild K, Wignall J, Mochizuki D Y, Schmierer A, Mosley B, March C J, Urdal D, Gillis S. Stimulation of B-cell progenitors by cloned murine interleukin-7. Nature. 1988;333:571–573. doi: 10.1038/333571a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noble A, Macary P A, Kemeny D M. IFN-gamma and IL-4 regulate the growth and differentiation of CD8+ T cells into subpopulations with distinct cytokine profiles. J Immunol. 1995;155:2928–2937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pachuk C J, Arnold R, Herold K, Ciccarelli R B, Higgins T J. Humoral and cellular immune responses to herpes simplex virus-2 glycoprotein D generated by facilitated DNA immunization of mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;226:79–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80475-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plebanski M, Allsopp C E, Aidoo M, Reyburn H, Hill A V. Induction of peptide-specific primary cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses from human peripheral blood. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1783–1787. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson M J, Soiffer R J, Wolf S F, Manley T J, Donahue C, Young D, Hermann S H, Ritz J. Responses of human natural killer (NK) cells to NK cell stimulatory factor (NKSF): cytolytic activity and proliferation of NK cells are differentially regulated by NKSF. J Exp Med. 1992;175:779–788. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Romani L, Mocci S, Bietta C, Lanfaloni L, Puceetti P, Bistoni F. Th1 and Th2 cytokine secretion patterns in murine candidiasis: association of Th1 responses with acquired resistance. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4647–4654. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.12.4647-4654.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay C R, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott P, Natovitz P, Coffman R L, Pearce E, Sher A. Immunoregulation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. T cell lines that transfer protective immunity or exacerbation belong to different T helper subsets and respond to distinct parasite antigens. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1675–1684. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma D P, Ramsay A J, Maguire D J, Rolph M S, Ramshaw I A. Interleukin-4 mediates down regulation of antiviral cytokine expression and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and exacerbates vaccinia virus infection in vivo. J Virol. 1996;70:7103–7107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7103-7107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sin J I, Kim J J, Boyer J D, Higgins T J, Ciccarelli R B, Weiner D B. In vivo modulation of vaccine-induced immune responses toward a Th1 phenotype increases potency and vaccine effectiveness in a herpes simplex virus type 2 mouse model. J Virol. 1999;73:501–509. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.501-509.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sin J I, Kim J J, Arnold R L, Shroff K E, McCallus D, Pachuk C, McElhiney S P, Wolf M W, Pompa-de Bruin S J, Higgins T J, Ciccarelli R B, Weiner D B. Interleukin-12 gene as a DNA vaccine adjuvant in a herpes mouse model: IL-12 enhances Th1 type CD4+ T cell mediated protective immunity against HSV-2 challenge. J Immunol. 1999;162:2912–2921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sin J I, Ayyavoo V, Boyer J, Kim J, Ciccarelli R B, Weiner D B. Protective immune correlates can segregate by vaccine type in a murine herpes model system. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1763–1773. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.11.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Snapper C M, Paul W E. Interferon-gamma and B cell stimulatory factor-1 reciprocally regulate Ig isotype production. Science. 1987;236:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.3107127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tumpey T M, Cheng H, Yan X-T, Oakes J E, Lausch R N. Chemokine synthesis in the HSV-1-infected cornea and its suppression by interleukin-10. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:486–492. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Boyer J D, Srikantan V, Ugen K E, Gilbert L, Phan C, Dang K, Merva M, Agadjanyan M G, Newman M, Carrano R, McCallus D, Coney L, Williams W V, Weiner D B. Induction of humoral and cellular immune responses to the human immunodeficiency type-1 virus in non-human primates by in vivo DNA inoculation. Virology. 1995;211:102–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiles M V, Ruiz P, Imhof B A. Interleukin-7 expression during mouse thymus development. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1037–1042. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolowczuk I, Delacre M, Roye O, Giannini S L, Auriault C. Interleukin-7 in the skin of Schistosoma mansoni-infected mice is associated with a decrease in interferon-gamma production and leads to an aggravation of the disease. Immunology. 1997;91:35–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00229.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yu Z, Manickan E, Rouse B T. Role of interferon-gamma in immunity to herpes simplex virus. J Leukoc Biol. 1996;60:528–532. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.4.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]