Abstract

QT interval, a surrogate measure for ventricular action potential duration (APD) in the surface ECG, is widely used to identify cardiac abnormalities and drug safety. In humans, cardiac APD and QT interval are prominently affected by heart rate (HR), leading to widely accepted formulas to correct the QT interval for HR changes (QT corrected - QTc). While QTc is widely used in the clinic, the proper way to correct the QT interval in small mammals such as rats and mice is not clear. Over the years, empiric correction formulas were developed for rats and mice, which are widely used in the literature. Recent experimental findings obtained from pharmacological and direct pacing experiments in unanesthetized rodents show that the rate-adaptation properties are markedly different from those in humans and the use of existing QTc formulae can lead to major errors in data interpretation. In the present review, these experimental findings are summarized and discussed.

Keywords: rodent cardiac electrophysiology, ECG, QT interval, effective refractory period, action potential duration, rate-adaptation

Introduction

QT interval measurement is an important aspect of any ECG evaluation and interpretation. It has significant clinical importance, as there is a correlation between the QT interval value and the risk of developing ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (Viskin, 2009; Lester et al., 2019). The importance of the QT interval did not come to light for several decades after the first description of the morphology of the human ECG by Willem Einthoven in 1885 (Lester et al., 2019). Louise Wolff, an American cardiologist who described the WPW syndrome with Parkinson and White, was probably the first person to measure the QT interval (G Postema and AM Wilde, 2014). However, the clinical importance of the QT interval was not fully understood until further work by Jervell and Lange-Nielsen in the late 1950s (Jervell and Lange-Nielsen, 1957), and by Romano, Gemme, Pongiglione, and Ward in the 1960s (Romano, 1963; Ward, 1964). Several types of long QT syndrome have since been described, and the recognition of the relationship between QT prolongation and serious ventricular arrhythmias has strengthened. Moreover, a series of patients treated with the antiarrhythmic drug quinidine were reported to have syncope due to ventricular tachycardia in the setting of a prolonged QT interval in 1964 (Selzer and Wray, 1964). The morphology of quinidine-induced ventricular tachycardia had a peculiar undulating appearance which in 1966 was termed Torsades de Pointes (TdP) by Desertennes (Dessertenne, 1966). In the subsequent decades, additional classes of medications including antibiotics and psychotropic drugs were linked to TdP and a number of these agents were subsequently withdrawn by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Fung et al., 2001). Drug-induced prolongation of the QT interval is usually caused by the drug’s ability to inhibit IKr, the rapid component of the delayed rectifier potassium current. In humans, this component is encoded by human ether-a-go-go related gene (hERG) (Redfern et al., 2003). In 2007, the FDA formed an internal review team responsible for overseeing the clinical assessment of QT prolongation for all drugs that the agency reviewed, thus assessment of QT prolongation has rapidly become an essential part of the development of new drugs (Darpo, 2010). Although it recommends correcting of the QT interval for HR, it also concedes that such correction can yield misleading results (Food and Drug Administration, 2005). Moreover, literature-based assessments indicate that only non-rodent mammalian models can mimic QT interval prolongation and TdP caused by human therapeutics (Davis, 1998; De Ponti et al., 2001; Webster et al., 2002; Redfern et al., 2003). IKr plays a small role if any in rodents and most studies agree that these models are inappropriate for the study of drug-induced TdP (Hoffmann and Warner, 2006).

QT interval rate dependence in humans

The QT interval consists of two components: the QRS complex and the T wave, which reflect ventricular depolarization and repolarization, respectively. Duration of the QT interval can vary widely in each individual (Al-Khatib et al., 2003). Many determinants contribute to this variation, including HR, age, sex, autonomic nervous activity, circadian rhythm, drugs, electrolyte variations, myocardial disease, and congenital syndromes (Al-Khatib et al., 2003; Tomaselli Muensterman and Tisdale, 2018). The greatest variation occurs with HR as it is the principal modulator of repolarization duration (Locati et al., 2017). The QT interval dependence on HR reflects the APD dependence on cycle length (CL), a fundamental property of cardiac muscle in humans and large mammals (Franz et al., 1988; Locati et al., 2017). Like APD, QT interval also decreases at shorter CL and prolongs as the CL increases. The kinetics of APD/QT interval adaptation consists of a fast response followed by a gradual course towards a new steady-state value (Franz et al., 1988; Seethala et al., 2011). Mechanisms underlying this adaptive response include inactivation of the L-type calcium current as well as activation of the slow component of the delayed rectifier K+ current (Kv7.1/Iks). In addition, it appears that mechanisms affecting intracellular Na+ accumulation are important determinants of the slow phase of adaptation (Pueyo et al., 2010; O'Hara and Rudy, 2012; Schmitt et al., 2014). ADP and QT interval do not adapt solely on the basis of changes in CL. Exercise and adrenergic stimulation which promote both tachycardia and QT interval shortening are known to induced adaptation beyond that observed during pacing (Seethala et al., 2011). This phenomena involves autonomic stimulation of Kv7.1 (Vyas and Ackerman, 2006). Many QTc formulae have been developed to normalize the QT interval to rate-dependent changes with variable utility in the clinic (Rautaharju et al., 2009; G Postema and AM Wilde, 2014; Locati et al., 2017). The most commonly used correction method in the clinic is the QT Bazett’s formula (G Postema and AM Wilde, 2014; Locati et al., 2017) in which QTc is calculated as the QT interval in seconds divided by the square root of the preceding CL in seconds (Bazett, 1920). When HR is particularly fast or slow, the Bazett’s formula may over or underestimate the baseline QT, respectively. However, regardless of this limitation it still remains the current standard in clinical practice (G Postema and AM Wilde, 2014; Locati et al., 2017).

Myocardial repolarization in rats and mice

Although the overall principles of myocardial excitation are the same in all mammalian species, the role of repolarizing currents markedly differ between humans and rodents (Boukens et al., 2014). This is presumably dictated by the great variations in HR and HR modulation among species. Humans have a resting HR of ≈60 bpm, whereas rats and mice have a HR of on average 6 and 10 times higher, respectively (Kaese and Verheule, 2012; Milani-Nejad and Janssen, 2014; Konopelski and Ufnal, 2016). In addition, while rats and mice can increase their HR by around 40%–50% and 30%–40% respectively, humans can increase their HR by up to 300% (Milani-Nejad and Janssen, 2014; Janssen et al., 2016). These differences require repolarizing K+ ionic currents with different kinetics in order to adapt the APD appropriately. In rats and mice, the major repolarizing K+ ionic currents are the transient outward K+ current (Ito) and ultra-rapid potassium current (Ikur), and the ventricular APD has a triangular shape, with short repolarization and no clear plateau phase (Watanabe et al., 1983; Varró et al., 1993; Knollmann et al., 2001). Importantly, most rodent studies involve direct pacing under anesthesia, or ex-vivo/in-vitro preparations, overlooking the effects of autonomic stimulation. Indeed, there is some evidence that IKs mediates repolarization in rat cardiomyocytes under β-adrenergic stimulation (Xu et al., 2016). In addition, among mice, the most phosphorylated protein upon β1-adrenergic receptor activation of the heart is Kv7.1 (Lundby et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the in-vivo effect of IKs on the QT of mice is questionable considering the notable QT prolongation observed in response to β-adrenergic stimulation (Speerschneider and Thomsen, 2013). Adrenergic stimulation also resulted in phosphorylation of INa (Nav1.5), an additional potential mechanism by which changes in autonomic balance may affect repolarization duration (Lundby et al., 2013). Thus, the mechanisms governing APD in the unanesthetized rodent seem to be far more complex than Ito/IKur -dependent repolarization.

Rate-adaptation studies of ADP and QT interval in rodents

As mentioned above the basic electrophysiological components governing ADP in the rodent myocardium are relatively well known. Still, in-vivo rate-dependence of the APD and QT are rather poorly defined in these species. As already mentioned, one possible explanation for this is the technical challenge in performing advanced EP studies in unanesthetized rodents. In addition, results may vary substantially depending on the used methodology (i.e., type of anesthesia, type of perfused solution) and indeed, data regarding the electrophysiological properties of rodents show marked variations in the literature (Kaese and Verheule, 2012). Although the determinants of the rate-dependence of APD differ between small rodents and humans (as described above) there are various publications supporting the notion that typical rate-adaptation still exists in rodents (Table 1). However, various publications have demonstrated no rate-adaptation or even atypical rate-adaptation (i.e., increased APD at shorter CL). This variability raise the question whether discrepancies between studies might be secondary to differences in techniques (e.g., techniques that interfere with endogenous autonomic modulation such as anesthetics, large doses of exogenous catecholamines, overcontrolling for circadian rhythm). In any case, these discrepancies stresses the importance of obtaining data from unanesthetized rodents under physiological conditions in order to arrive at reliable conclusions. Another major challenge and source of uncertainty in evaluations of the relationship between HR and repolarization of rodent and particularly mice is identification of the end of the T wave. Because of the high HRs, motion artifact, and other sources of signal noise with telemetry devices, obtaining clean ECG signals in conscious rodents can be particularly challenging. As well, the end of the negative murine T wave is more subtle and therefore elusive to automated software detection than in humans and other mammals with more overt, positive T waves.

TABLE 1.

Summary of studies in which QT interval, ERP and APD rate relation were evaluated in rats and mice.

Typical rate adaptation ↓ Flat rate adaptation ↔ Atypical rate adaptation ↑

Discussion

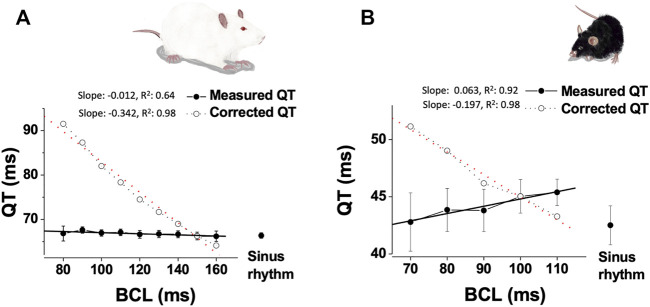

The dependence of QT interval of HR is debatable in rats and mice (Hayes et al., 1994; Ohtani et al., 1997; Mitchell et al., 1998; Kmecova and Klimas, 2010; Speerschneider and Thomsen, 2013; Roussel et al., 2016; Mulla et al., 2018). For example, Mitchell et al. (Mitchell et al., 1998) used the natural daily variation in HR in unanesthetized mice and found a strong correlation between the QT interval and HR, where slower HRs were associated with longer QT intervals. In contrast, Roussel et al. (Roussel et al., 2016) examined the same natural daily variation in HR as well as changes induced by tachycardic agents (norepinephrine or nitroprusside) and concluded that increased HR was not associated with apparent shortening of the QT interval. Nevertheless, at least for the circadian data it might be possible that analysis of light and dark phases separately for QT-RR relationships may over-control for endogenous changes in rate and repolarization mediated by circadian fluctuations in rhythm and autonomic modulation. Sudhir et al. (Sudhir et al., 2020) recently explored adaptation of QT to physical stress in mice overexpressing SUR2A, a regulatory subunit of sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive K + (KATP) channels. Although the results show highly complex pattern of changes over time in both transgenic and control mice, only corrected QT intervals (using Mitchell’s formula) are presented in the study, limiting ability to evaluate the effects of exercise on the native QT interval. In rats, a QT interval correction formula suggested by Kmecova and Klimas (Kmecova and Klimas, 2010) was validated using pharmacological manipulations affecting HR. Interestingly, adrenergic stimulation with isoproterenol as well as selectively manipulation of the HR by ivabradine, did not affect the QT interval in this study. Technical challenges largely limited direct pacing experiments as a mean of evaluating QT rate-dependence in rodents. However, Mulla et al. (2018) managed to explore the QT interval of freely moving rats and mice during atrial pacing at various CL values through a unique chronically implanted device. The findings of this work indicated absence of conventional rate-adaptation of the QT interval over a wide range of physiologically relevant frequencies. Moreover, ventricular ERP (a surrogate of ventricular APD) also demonstrated absence of typical rate-dependence. Calculating the QTc interval according to the formulae suggested by Kmecova and Klimas (Kmecova and Klimas, 2010) for rats and by Mitchell et al. (1998) for mice, resulted in marked difference between the measured QT interval and the QTc interval for a wide range of atrial pacing rates in both species (Figure 1). At the present, it is hard to conclude what is the optimal way of QT correction in rodent and if correction is required at all. However, it appears that the existing and widely use correction formulas can introduce marked errors. This issue seems specifically relevant for Mitchell formula for mice that appears to overcorrect QT, indicating a great need for a better QT correction formula for mice. Overall, we suggest that any correction formula used should be validated in that species under baseline conditions using comparable analytic methods and measurement techniques as those applied during/after experimental treatments. As well, we suggest that as a standard, corrected QT results should be presented along with those for uncorrected QT. Importantly, to the best of our knowledge direct data on the relationship between QT and HR in the unanesthetized Guinea pig are lacking in literature. Given the existence of Ikr and Iks in the myocardium and their broad utility for QT prolongation studies, we believe that understanding the precise HR-QT relationship of this animal model in future studies will be of high value as well.

FIGURE 1.

Absence of QT interval dependence on HR in paced unanesthetized rodents. (A). Data from instrumented, unanesthetized male SD rats that were subjected to atrial pacing at different CL (n = 10): Mean ± SE of measured QT and calculated QTc (based on the formula of Kmecova and Klimas (Kmecova and Klimas, 2010)), plotted as a function of CL. Linear regression data (slope, R2) are presented for both QT and calculated QTc. (B). Data from instrumented, unanesthetized male C57BL/J mice that were subjected to atrial pacing at different CL (n = 9): Mean ± SE of measured QT and calculated QTc [based on the formula of Mitchell et al. (1998)], plotted as a function of CL. Linear regression data (slope, R2) are presented for both QT and calculated QTc. Experimental findings were adapted from Mulla et al. (2018).

In conclusion, conflicting data still exists regarding the dependence between QT interval and HR in rodents. Multiple physiological and technical complexities and challenges prevents clear conclusions regarding this issue based on the currently available data. However, large body of evidence support the notion that the extensive use of existing correction formulae may introduce significant errors and thus further and more systematic exploration of this issue would be of high value.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Layan Faris for the illustrations in the figure.

Author contributions

WM. drafted manuscript; MM, OL, and YE. edited and revised manuscript; WM, MM, OL, and YE. approved final version of manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Adeyemi O., Parker N., Pointon A., Rolf M. (2020). A pharmacological characterization of electrocardiogram PR and QRS intervals in conscious telemetered rats. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 102, 106679. 10.1016/j.vascn.2020.106679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khatib S. M., Lapointe N. M. A., Kramer J. M., Califf R. M. (2003). What clinicians should know about the QT interval. Jama 289, 2120–2127. 10.1001/jama.289.16.2120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazett H. C. (1920). An analysis of the time relations of electrocardiograms. Heart 7, 353–370. [Google Scholar]

- Benoist D., Stones R., Drinkhill M., Bernus O., White E. (2011). Arrhythmogenic substrate in hearts of rats with monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 300, H2230–H2237. 10.1152/ajpheart.01226.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoist D., Stones R., Drinkhill M. J., Benson A. P., Yang Z., Cassan C., et al. (2012). Cardiac arrhythmia mechanisms in rats with heart failure induced by pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H2381–H2395. 10.1152/ajpheart.01084.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berul C. I., Aronovitz M. J., Wang P. J., Mendelsohn M. E. (1996). In vivo cardiac electrophysiology studies in the mouse. Circulation 94, 2641–2648. 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blesa E. S., Langer G. A., Brady A. J., Serena S. D. (1970). Potassium exchange in rat ventricular myocardium: Its relation to rate of stimulation. Am. J. Physiol. 219, 747–754. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.3.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukens B. J., Rivaud M. R., Rentschler S., Coronel R. (2014). Misinterpretation of the mouse ECG:‘musing the waves of Mus musculus . J. Physiol. 592, 4613–4626. 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.279380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch J. R., West T. C., Hoff H. E. (1969). Development of the action potential of the prenatal rat heart. Circ. Res. 24, 19–31. 10.1161/01.res.24.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darpo B. (2010). The thorough QT/QTc study 4 years after the implementation of the ICH E14 guidance. Br. J. Pharmacol. 159, 49–57. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00487.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A. S. (1998). The pre-clinical assessment of QT interval prolongation: A comparison of in vitro and in vivo methods. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 17, 677–680. 10.1177/096032719801701205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ponti F., Poluzzi E., Montanaro N. (2001). Organising evidence on QT prolongation and occurrence of torsades de Pointes with non-antiarrhythmic drugs: A call for consensus. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 185–209. 10.1007/s002280100290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessertenne F. (1966). Ventricular tachycardia with 2 variable opposing foci. Arch. Mal. Coeur Vaiss. 59, 263–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etzion Y., Mor M., Shalev A., Dror S., Etzion O., Dagan A., et al. (2008). New insights into the atrial electrophysiology of rodents using a novel modality: The miniature-bipolar hook electrode. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H1460–H1469. 10.1152/ajpheart.00414.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauconnier J., Bedut S., Le Guennec J.-Y., Babuty D., Richard S. (2003). Ca2+ current-mediated regulation of action potential by pacing rate in rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 57, 670–680. 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00731-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein A., Hecht Z., Varon D., Eyal E., Nebel L., Manoach M. (1991). A correlation between the structure of myocardial cells and prolonged QT interval in young rats. Int. J. Cardiol. 32, 13–22. 10.1016/0167-5273(91)90039-r [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food, and Drug Administration H. (2005). International conference on harmonisation; guidance on E14 Clinical Evaluation of QT/QTc interval prolongation and proarrhythmic potential for non-antiarrhythmic drugs; availability. notice. Fed. Regist. 70, 61134–61135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis Stuart S. D., Wang L., Woodard W. R., Ng G. A., Habecker B. A., Ripplinger C. M. (2018). Age‐related changes in cardiac electrophysiology and calcium handling in response to sympathetic nerve stimulation. J. Physiol. 596, 3977–3991. 10.1113/JP276396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R., Swerdlow C. D., Liem L. B., Schaefer J. (1988). Cycle length dependence of human action potential duration in vivo. Effects of single extrastimuli, sudden sustained rate acceleration and deceleration, and different steady-state frequencies. J. Clin. Invest. 82, 972–979. 10.1172/JCI113706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung M., Thornton A., Mybeck K., Wu J. H.-H., Hornbuckle K., Muniz E. (2001). Evaluation of the characteristics of safety withdrawal of prescription drugs from worldwide pharmaceutical markets-1960 to 1999. Drug Inf. J. 35, 293–317. 10.1177/009286150103500134 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- G Postema P., Am Wilde A. (2014). The measurement of the QT interval. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 10, 287–294. 10.2174/1573403x10666140514103612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy M. E., Pervolaraki E., Bernus O., White E. (2018). Dynamic action potential restitution contributes to mechanical restitution in right ventricular myocytes from pulmonary hypertensive rats. Front. Physiol. 9, 205. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes E., Pugsley M., Penz W., Adaikan G., Walker M. (1994). Relationship between QaT and RR intervals in rats, Guinea pigs, rabbits, and primates. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 32, 201–207. 10.1016/1056-8719(94)90088-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann P., Warner B. (2006). Are hERG channel inhibition and QT interval prolongation all there is in drug-induced torsadogenesis? A review of emerging trends. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 53, 87–105. 10.1016/j.vascn.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett L. A., Kirton H. M., Al‐Owais M. M., Steele D., Lancaster M. K. (2022). Action potential responses to changes in stimulation frequency and isoproterenol in rat ventricular myocytes. Physiol. Rep. 10, e15166. 10.14814/phy2.15166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Ding W., Li L., Zhao D. (2006). Differences in the aging-associated trends of the monophasic action potential duration and effective refractory period of the right and left atria of the rat. Circ. J. 70, 352–357. 10.1253/circj.70.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen P. M., Biesiadecki B. J., Ziolo M. T., Davis J. P. (2016). The need for speed: Mice, men, and myocardial kinetic reserve. Circ. Res. 119, 418–421. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jervell A., Lange-Nielsen F. (1957). Congenital deaf-mutism, functional heart disease with prolongation of the QT interval, and sudden death. Am. Heart J. 54, 59–68. 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90079-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce W., Scholman K. T., Jensen B., Wang T., Boukens B. J. (2021). α1-adrenergic stimulation increases ventricular action potential duration in the intact mouse heart. FACETS 6, 823–836. 10.1139/facets-2020-0081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaese S., Verheule S. (2012). Cardiac electrophysiology in mice: A matter of size. Front. Physiol. 3, 345. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keung E., Aronson R. (1981). Non-uniform electrophysiological properties and electrotonic interaction in hypertrophied rat myocardium. Circ. Res. 49, 150–158. 10.1161/01.res.49.1.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmecova J., Klimas J. (2010). Heart rate correction of the QT duration in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 641, 187–192. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann B. C., Katchman A. N., Franz M. R. (2001). Monophasic action potential recordings from intact mouse heart: Validation, regional heterogeneity, and relation to refractoriness. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 12, 1286–1294. 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.01286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann B. C., Schober T., Petersen A. O., Sirenko S. G., Franz M. R. (2007). Action potential characterization in intact mouse heart: Steady-state cycle length dependence and electrical restitution. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 292, H614–H621. 10.1152/ajpheart.01085.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konopelski P., Ufnal M. (2016). Electrocardiography in rats: A comparison to human. Physiol. Res. 65, 717–725. 10.33549/physiolres.933270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni K., Xie X., Fernandez De Velasco E. M., Anderson A., Martemyanov K. A., Wickman K., et al. (2018). The influences of the M2R-GIRK4-RGS6 dependent parasympathetic pathway on electrophysiological properties of the mouse heart. PloS one 13, e0193798. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester R. M., Paglialunga S., Johnson I. A. (2019). QT assessment in early drug development: The long and the short of it. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 1324. 10.3390/ijms20061324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Deng C.-Y., Xue Y.-M., Yang H., Wei W., Liu F.-Z., et al. (2020). High hydrostatic pressure induces atrial electrical remodeling through angiotensin upregulation mediating FAK/Src pathway activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 140, 10–21. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati E. T., Bagliani G., Padeletti L. (2017). Normal ventricular repolarization and QT interval: Ionic background, modifiers, and measurements. Card. Electrophysiol. Clin. 9, 487–513. 10.1016/j.ccep.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundby A., Andersen M. N., Steffensen A. B., Horn H., Kelstrup C. D., Francavilla C., et al. (2013). In vivo phosphoproteomics analysis reveals the cardiac targets of β-adrenergic receptor signaling. Sci. Signal. 6, rs11. 10.1126/scisignal.2003506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani-Nejad N., Janssen P. M. (2014). Small and large animal models in cardiac contraction research: Advantages and disadvantages. Pharmacol. Ther. 141, 235–249. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell G. F., Jeron A., Koren G. (1998). Measurement of heart rate and QT interval in the conscious mouse. Am. J. Physiol. 274, H747–H751. 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.3.H747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulla W., Gillis R., Murninkas M., Klapper-Goldstein H., Gabay H., Mor M., et al. (2018). Unanesthetized rodents demonstrate insensitivity of QT interval and ventricular refractory period to pacing cycle length. Front. Physiol. 9, 897. 10.3389/fphys.2018.00897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murninkas M., Gillis R., Lee D. I., Elyagon S., Bhandarkar N. S., Levi O., et al. (2020). A new implantable tool for repeated assessment of supraventricular electrophysiology and atrial fibrillation susceptibility in freely moving rats. Am. J. Physiology-Heart Circulatory Physiology 320, H713–H724. 10.1152/ajpheart.00676.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuyens D., Stengl M., Dugarmaa S., Rossenbacker T., Compernolle V., Rudy Y., et al. (2001). Abrupt rate accelerations or premature beats cause life-threatening arrhythmias in mice with long-QT3 syndrome. Nat. Med. 7, 1021–1027. 10.1038/nm0901-1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'hara T., Rudy Y. (2012). Quantitative comparison of cardiac ventricular myocyte electrophysiology and response to drugs in human and nonhuman species. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302, H1023–H1030. 10.1152/ajpheart.00785.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obergassel J., O’reilly M., Sommerfeld L. C., Kabir S. N., O’shea C., Syeda F., et al. (2021). Effects of genetic background, sex, and age on murine atrial electrophysiology. EP Eur. 23, 958. 10.1093/europace/euaa369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani H., Kotaki H., Sawada Y., Iga T. (1997). A comparative pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic study of the electrocardiographic effects of epinastine and terfenadine in rats. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 49, 458–462. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacher P., Ungvari Z., Nanasi P., Kecskemeti V. (1999). Electrophysiological changes in rat ventricular and atrial myocardium at different stages of experimental diabetes. Acta Physiol. Scand. 166, 7–13. 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00538.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payet M., Schanne O., Ruiz-Ceretti E. (1981). Frequency dependence of the ionic currents determining the action potential repolarization in rat ventricular muscle. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 13, 207–215. 10.1016/0022-2828(81)90217-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucelik P., Jezek K., Bartak F. (1982). Postnatal development of electrophysiological manifestations of the working ventricular myocardium of albino rats. Physiol. Bohemoslov. 31, 217–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pueyo E., Husti Z., Hornyik T., Baczkó I., Laguna P., Varró A., et al. (2010). Mechanisms of ventricular rate adaptation as a predictor of arrhythmic risk. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 298, H1577–H1587. 10.1152/ajpheart.00936.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapuzzi G., Rindi G. (1967). Inluence of increasing heart rate on the alterations of the cardiac ventricular fibre-cells action potentials induced by thiamine deficiency. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. Cogn. Med. Sci. 52, 277–284. 10.1113/expphysiol.1967.sp001913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautaharju P. M., Surawicz B., Gettes L. S., Bailey J. J., Childers R., Deal B. J., et al. (2009). AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: Part IV: The ST segment, T and U waves, and the QT interval a scientific statement from the American heart association electrocardiography and arrhythmias committee, council on clinical cardiology; the American college of cardiology foundation; and the heart rhythm society endorsed by the international society for computerized electrocardiology. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 53, 982–991. 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redfern W., Carlsson L., Davis A., Lynch W., Mackenzie I., Palethorpe S., et al. (2003). Relationships between preclinical cardiac electrophysiology, clinical QT interval prolongation and torsade de pointes for a broad range of drugs: Evidence for a provisional safety margin in drug development. Cardiovasc. Res. 58, 32–45. 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00846-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano C. (1963). Rare cardiac arrhythmias of the pediatric age. II: Syncopal attacks due to paroxysmal ventricular fibrillation (Presentation of 1st case in Italian pediatric literature). Clin. Pediatr. (Bologna) 45, 656–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel J., Champeroux P., Roy J., Richard S., Fauconnier J., Le Guennec J.-Y., et al. (2016). The complex QT/RR relationship in mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 25388. 10.1038/srep25388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabir I. N., Li L. M., Grace A. A., Huang C. L.-H. (2008). Restitution analysis of alternans and its relationship to arrhythmogenicity in hypokalaemic Langendorff-perfused murine hearts. Pflugers Arch. 455, 653–666. 10.1007/s00424-007-0327-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakatani T., Shirayama T., Yamamoto T., Mani H., Shiraishi H., Matsubara H. (2006). Cardiac hypertrophy diminished the effects of isoproterenol on delayed rectifier potassium current in rat heart. J. Physiol. Sci. 56, 173–181. 10.2170/physiolsci.RP002405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N., Grunnet M., Olesen S.-P. (2014). Cardiac potassium channel subtypes: New roles in repolarization and arrhythmia. Physiol. Rev. 94, 609–653. 10.1152/physrev.00022.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder E. A., Wayland J. L., Samuels K. M., Shah S. F., Burgess D. E., Seward T., et al. (2021). Cardiomyocyte deletion of Bmal1 exacerbates QT-and RR-interval prolongation in scn5a+/dkpq mice. Front. Physiol. 853, 681011. 10.3389/fphys.2021.681011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seethala S., Shusterman V., Saba S., Mularski S., Němec J. (2011). Effect of β-adrenergic stimulation on QT interval accommodation. Heart rhythm. 8, 263–270. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer A., Wray H. W. (1964). Quinidine syncope: Paroxysmal ventricular fibrillation occurring during treatment of chronic atrial arrhythmias. Circulation 30, 17–26. 10.1161/01.cir.30.1.17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu S., Kiyosue T., Sato T., Arita M. (1997). Rate-dependent prolongation of action potential duration in isolated rat ventricular myocytes. Basic Res. Cardiol. 92, 123–128. 10.1007/BF00788629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y., Firek L., Severson D., Giles W. (1994). Short-term diabetes alters K+ currents in rat ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 74, 620–628. 10.1161/01.res.74.4.620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoni Y., Severson D., Giles W. (1995). Thyroid status and diabetes modulate regional differences in potassium currents in rat ventricle. J. Physiol. 488, 673–688. 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speerschneider T., Thomsen M. B. (2013). Physiology and analysis of the electrocardiographic T wave in mice. Acta Physiol. 209, 262–271. 10.1111/apha.12172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhir R., Du Q., Sukhodub A., Jovanović S., Jovanović A. (2020). Improved adaptation to physical stress in mice overexpressing SUR2A is associated with changes in the pattern of Q-T interval. Pflugers Arch. 472, 683–691. 10.1007/s00424-020-02401-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syeda F., Holmes A. P., Yu T. Y., Tull S., Kuhlmann S. M., Pavlovic D., et al. (2016). PITX2 modulates atrial membrane potential and the antiarrhythmic effects of sodium-channel blockers. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 68, 1881–1894. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.07.766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli Muensterman E., Tisdale J. E. (2018). Predictive analytics for identification of patients at risk for QT interval prolongation: A systematic review. Pharmacotherapy 38, 813–821. 10.1002/phar.2146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varró A., Lathrop D., Hester S., Nanasi P., Papp J., Varro A. (1993). Ionic currents and action potentials in rabbit, rat, and Guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Basic Res. Cardiol. 88, 93–102. 10.1007/BF00798257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viskin S. (2009). The QT interval: Too long, too short or just right. Heart rhythm. 6, 711–715. 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.02.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas H., Ackerman M. J. (2006). Epinephrine QT stress testing in congenital long QT syndrome. J. Electrocardiol. 39, S107–S113. 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S., Dybkova N., Rasenack E. C., Jacobshagen C., Fabritz L., Kirchhof P., et al. (2006). Ca 2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates cardiac Na+ channels. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 3127–3138. 10.1172/JCI26620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldeyer C., Fabritz L., Fortmueller L., Gerss J., Damke D., Blana A., et al. (2009). Regional, age-dependent, and genotype-dependent differences in ventricular action potential duration and activation time in 410 Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. Basic Res. Cardiol. 104, 523–533. 10.1007/s00395-009-0019-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallman M., Scheuerer S., Martel E., Pairet N., Jirstrand M., Gabrielsson J. (2021). An integrative approach for improved assessment of cardiovascular safety data. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 377, 218–231. 10.1124/jpet.120.000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton R. D., Benson A., Hardy M., White E., Bernus O. (2013). Electrophysiological and structural determinants of electrotonic modulation of repolarization by the activation sequence. Front. Physiol. 4, 281. 10.3389/fphys.2013.00281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Fitts R. H. (2017). Ventricular action potential adaptation to regular exercise: Role of β-adrenergic and KATP channel function. J. Appl. Physiol. 123, 285–296. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00197.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward O. (1964). A new familial cardiac syndorome in children. J. Ir. Med. Assoc. 54, 103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warhol A., George S. A., Obaid S. N., Efimova T., Efimov I. R. (2021). Differential cardiotoxic electrocardiographic response to doxorubicin treatment in conscious versus anesthetized mice. Physiol. Rep. 9, e14987. 10.14814/phy2.14987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Delbridge L. M., Bustamante J. O., Mcdonald T. F. (1983). Heterogeneity of the action potential in isolated rat ventricular myocytes and tissue. Circ. Res. 52, 280–290. 10.1161/01.res.52.3.280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster R., Leishman D., Walker D. (2002). Towards a drug concentration effect relationship for QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 5, 116–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhao M., Liang S., Huang Q., Xiao Y., Ye L., et al. (2016). The effects of puerarin on rat ventricular myocytes and the potential mechanism. Sci. Rep. 6, 35475. 10.1038/srep35475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ypma J. (1972). Adaptation of refractory period of rat ventricle to changes in heart rate. Am. J. Physiol. 223, 894–897. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.223.4.894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]