Abstract

Mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene cause cystic fibrosis (CF), a chronic disease that affects multiple organs, including the lung. We developed a CF ferret model of a scarless G551→D substitution in CFTR (CFTRG551D-KI), enabling approaches to correct this gating mutation in CF airways via gene editing. Homology-directed repair (HDR) was tested in Cas9-expressing CF airway basal cells (Cas9-GKI) from this model, as well as reporter basal cells (Y66S-Cas9-GKI) that express an integrated nonfluorescent Y66S-EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) mutant gene to facilitate rapid assessment of HDR by the restoration of fluorescence. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors were used to deliver two DNA templates and sgRNAs for dual-gene editing at the EGFP and CFTR genes, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting of EGFPY66S-corrected cells. When gene-edited airway basal cells were polarized at an air–liquid interface, unsorted and EGFPY66S-corrected sorted populations gave rise to 26.0% and 70.4% CFTR-mediated Cl− transport of that observed in non-CF cultures, respectively. The consequences of gene editing at the CFTRG551D locus by HDR and nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) were assessed by targeted gene next-generation sequencing (NGS) against a specific amplicon. NGS revealed HDR corrections of 3.1% of G551 sequences in the unsorted population of rAAV-infected cells, and 18.4% in the EGFPY66S-corrected cells. However, the largest proportion of sequences had indels surrounding the CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) cut site, demonstrating that NHEJ was the dominant repair pathway. This approach to simultaneously coedit at two genomic loci using rAAV may have utility as a model system for optimizing gene-editing efficiencies in proliferating airway basal cells through the modulation of DNA repair pathways in favor of HDR.

Keywords: gene editing, AAV, ferret, airway, basal cells, cystic fibrosis, CFTR

INTRODUCTION

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a lethal autosomal-recessive disorder caused by mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene.1 CFTR plays an important role in conducting chloride and bicarbonate ions across epithelia to regulate secretory volume, pH, and mucus viscosity of liquid secretions.2,3 Nearly 2,000 distinct CFTR mutations have been identified, of which over 400 are causative for CF (www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/app). Although CF affects multiple organs, chronic lung infection is the primary cause of death.4 While the newly developed CFTR modulator therapies are effective in a large portion of the CF population, these genotype-dependent pharmaceuticals are ineffective in ∼10% of CF patients who have nonsense, frameshift, or splicing mutations resulting in little to no production of CFTR protein, as well as those who cannot tolerate CFTR modulators.5,6 Thus, gene therapy remains an attractive approach for the treatment of CF.

Although no prior gene therapy clinical trial for CF lung disease has achieved desired outcomes, more recent advances in vector development targeting the airways of large animal models that recapitulate the human CF lung phenotype have inspired a resurgence in gene therapy efforts for CF.7–13 While CFTR gene-replacement strategies still remain the primary approach for current and pending CF clinical trials, rapidly emerging gene-editing technologies present new opportunities to advance CF gene therapy from simple gene addition to precise gene correction. CFTR expression is highly regulated by individual cell types in the lung, each having its own potentially unique composition of channels and functions that coordinate clearance and innate immunity.14–17 Gene editing provides a therapeutic solution to restore CFTR function without altering its endogenous patterns of expression in the gene-corrected cells.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) work with a CRISPR-associated protein, such as Cas9 to generate a double stranded DNA break at a desired site in the genome.18,19 Acting as a specific programmable nuclease, the CRSIPR/Cas9 approach enables genetic modification of a gene of interest via homologous recombination (HR), exon skipping, gene disruption, or targeted insertion.20 CRISPR-based gene therapy has shown promise against sickle cell disease by correcting the mutation in hematopoietic stem cells ex vivo,21 and transthyretin amyloidosis by disrupting the disease-causing allele in vivo.22 Gene editing theoretically solves the complexities of CFTR regulation at the cellular level in the lung.

While successful correction of CFTR mutations in postmitotic airway epithelial cells likely leads to durable treatment in CF patients because of the relatively slow turnover rate of these cell types,23 permanent correction is only achievable by targeting self-renewing stem/progenitor cells in the airways. Basal cells are the major multipotent somatic stem cell population in the tracheobronchial airways and responsible for maintenance and repair of the airway epithelium.24–26 In this study, we tested CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HR using recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) to correct the G551D gating mutation in the CFTR gene of proliferating airway basal cell cultures derived from CFTRG551D-KI ferrets (GKI ferrets).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of CFTRG551D-KI ferret model using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HR

Animal experimentation was performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Iowa. The mutagenesis template for HR was a 192-mer single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (ssOND). The sgRNA, gRNA-G551D was designed using online tool CRISPOR (http://crispor.tefor.net). spCas9 protein (from Streptococcus pyogenes), gRNA-G551D, the ssOND, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers for genotyping were generated at Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (IDT, Coralville, IA). The collection of fertilized ferret single-cell embryos (zygotes) and zygote microinjection were conducted as previously described.27 The ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (spCas9/gRNA-G551D) was coinjected with ssOND at 20 ng/μL. G551D-positive kits were determined by PCR-based genotypic analysis following Sanger sequencing confirmation. Sequences of the ssOND, gRNA-G551D, and PCR primers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequence of mutagenesis template, sgRNA targeted site and polymerase chain reaction primers

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| ssONDa | cctctctaactttctgtttttggtaataggacatctccaagtttgcagagaaggacaatatcgtccttggagaaggtggaatcacactgagtggTgATcagcgagcaagaatttccttagcaaggtgaatatcccattattggttcagcgagcatttgttgtaaatatcatgcatgtaaaaattatagacat |

| gRNA-G551Db | gaaggtggaatcacact//gagTGG |

| gRNA-S66b | gcggctgaagcactgca//cgcCGG |

| HR-Fw | aggcgcccctggagatttcc |

| Fw1 | catggtcatgaaggacattc |

| Rev | aactaggaagtagaagcagaagc |

| G551DtgTw | aacagttcctctctaactttctg |

| G551DtgRev | cgaggcatttttcagtttcag |

The oligo mutagenesis template: Upper case indicates the nucleotides different from the original wild-type allele, bold fonts are the D551 codon and underlined nucleotides indicate the BclI site created in the HR template for easy genotypic assay of the G551D mutation.

Cas9/gRNA complex targeted DNA sequences with the PAM in ferret CFTR locus or integrated EGFPY66S in ferret genome: upper cases are the PAM, // mark the cleavage site.

CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; HR, homologous recombination; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif; ssOND, single stranded DNA oligonucleotides.

Viral vectors and primary cell cultures

Lentiviral vectors

LentCas9-Blast (Addgene plasmid #52962) carries an EF1α core promoter driven SpCas9-p2A-BSD expression cassette.28 SpCas9-p2A-BSD is a self-cleaving fusion protein of a SpCas9 (with nuclear localization sequence) and BSD (product of the blasticidin S resistance gene). Lenti-Y66SeGFP-Puro was produced from a derivative of pLenti-CMVGFP-Puro (658-5) (Addgene plasmid #17448),29 in which the EGFP cDNA was replaced by the mutant EGFPY66S, through a single-nucleotide substitution at the Y66 codon.30 VSV-G pseudotyped lentiviral vectors were generated from transfection in HEK293T cells and the functional titers were quantified using TaqMan PCR quantification of viral genome integration following infection of HEK293T, as previously described.31 Titer were expressed as transduction units (TU)/mL.

Recombinant adeno-associated virus

AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) was produced as previously described by pseudopackaging an rAAV2 genome into AAV6 capsid.32 Titer was determined by TaqMan PCR as DNase I-resistant particles (DRP) per microliter. The rAAV genome carries two sets of homology templates and sgRNAs, enabling a dual-correction of the mutations of G551D in CFTR and Y66S in EGFP by homology-directed repair (HDR). The expression of sgRNAs was driven by the human U6 snRNA promoter. gRNA-G551D was the one used in the generation of the CFTRG551D-KI ferret model. gRNA-S66 (sequence is presented in Table 1) specifically recognized the sequence of the EGFPY66S with the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) placed within the S66 codon, which prevented cleavage at the wild-type (WT) EGFP sequence (Y66).

The HR template for G551D correction was an 811 bp sequence containing CFTR exon-12 with the non-CF G551 codon at the center. Silent mutations within the HR donor fragment substituted three nucleotides near and within the PAM sequence targeted by the gRNA-G551D; this created a new restriction enzyme site (BspEI), which was used to confirm HDR and prevented the CRISPR-mediated cleavage of the HR template and repaired sequence. The HDR template for Y66S correction was a shortened EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein) sequence harboring a 90 bp truncation at 3′ end (EGFP-630), as previously described.33 This sequence does not produce a fluorescent protein product.33

Proliferating ferret airway basal cells

As previously described,34 primary tracheal cells were dissociated and collected from the trachea of homozygote GKI ferret (GK/GK143, male, 84 days old). Airway basal cells from GKI ferret were expanded in PneumaCult™-Ex Plus medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) for six continuous passages before being cryopreserved as the P6 frozen stocks for future studies.

Polarized ferret airway epithelial cultures

1.5 × 105 basal cells were seeded onto 6.5-mm, polyester Transwell® inserts (Corning, Corning) that were precoated with collagen IV (Sigma, St. Louis). Seeding occurred in PneumaCult-Ex Plus medium. At 24 h postseeding, medium was replaced with PneumaCult ALI medium (StemCell Technologies) in both apical and basal chambers. Cultures were then air-lifted the following day to facilitate differentiation of the polarized ferret airway epithelium (FAE) at an air–liquid interface (ALI) for at least 3 weeks.35 Matured FAE-ALI cultures (transepithelial electric resistance >1,000 Ω/cm2) were used for Ussing chamber assays.36 The basal chamber medium was replaced twice a week during the culturing period.

Short-circuit current measurements in Ussing chambers

The ALI culture inserts were placed under VCC MC8 voltage/current clamps in self-contained P2300 Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) for short-circuit current (Isc) measurement using an asymmetric chloride buffer system, as previously described.37 One hundred micromolars amiloride, 100 μM 4,4′-diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid, 100 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX)/10 μM forskolin (Forsk), and 50 μM GlyH-101 were sequentially added to the apical chamber, and the changes in current were recorded during the experiment.

Establishment of the Cas9-expressing airway basal cell pools

Cas9-GKI cell pool

The P6 GKI airway basal cells were infected with Lenti-Cas9-Blast at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1.5 TU/cell. Selection for blasticidin S-resistant cells was started 2 days after lentiviral infection in PneumaCult-Ex Plus medium supplemented with 10 μg/mL blasticidin S. All the cells of mock-infected control died within 2 days after exposure to blasticidin S, allowing for rapid selection of a blasticidin S-resistant polyclonal pools of Cas9-expressing cells within a week.

Y66S-Cas9-GKI cell pool

Cas9-GKI basal cells (5 days after blasticidin S selection) were infected with Lenti-Y66SeGFP-Puro at an MOI of 1.5 TU/cell to enable the expression of Y66S-EGFP. Selection with puromycin at 1 μg/mL was started 2 days after infection. The double-resistant cell pool, Y66S-Cas9-GKI, was obtained after exposure to blasticidin S and puromycin for 1 week.

Gene editing and assessments

Of the Cas9-GKI, 2 × 105 cells or Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cell pool were seeded onto a well of a six-well plate. The next day, cells were infected with AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) at an MOI of 5 × 104 DRP per cell. The rAAV infected Cas9-GKI cells were then lysed at 3 days postinfection. Genomic DNA was extracted for PCR to assess gene editing at the CFTRG551D locus. The rAAV-infected Y66S-Cas9-GKI cells were subjected to limited expansion before the assessment of dual-gene editing of EGFPY66S and CFTRG551D loci. At 3 days postinfection, cells were transferred to two 100 mm dishes for expansion. The culture attained confluency after 1 week, from which ∼3 × 107 cells were obtained.

Ten days postinfection, 9/10th of the total cell population (2.7 × 107 cells) was used for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to collect the EGFPY66S-corrected cells (green) and to determine the gene correction efficiency. The viable green cells obtained from FACS and the remaining portion (1/10th) of unsorted cells were put back into culture. Two days later (12 days post-rAAV infection), cells from both sorted and unsorted populations were used for genomic DNA extraction and polarization of FAE-ALI cultures.

The PCR primer set HR-Fw/Rev, located outside the CFTR homology sequence carried in the rAAV-targeted vector, was used to amplify an 887 bp product from the genomic DNA obtained from rAAV-transduced cells. The PCR products were cloned into pCR4blunt-Topo (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 48 plasmid clones were randomly picked for Sanger sequencing. A 243 bp amplicon that covered exon-12 was obtained by PCR using the 887 bp product as template and an internal primer set G551DtgFw/G551DtgRev. This 243 bp amplicon was evaluated by deep sequencing to quantify variants using an Illumina platform; sequencing was performed by BGI Americas Corporation (Cambridge, MA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using GraphPad Prism 8. Values and error bars show means ± standard error of the mean, statistical significance was determined using a Student's t-test with p < 0.05 being significant.

RESULTS

Generation of the CFTRG551D ferret model via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in ferret zygotes

CFTRG551D is the third most common CF-associated mutation found in 2–5% of patients with CF. The G551D codon resides in the ATP-binding pocket within the nucleotide-binding domains-1 of CFTR protein. The substitution of aspartate (D) for glycine (G) abolishes ATP-dependent gating of the channel. The CFTR potentiator VX-770 (ivacaftor; KALYDECO®) restores channel gating of the mutant protein. We have previously described the generation of a G551D ferret model (CFTRG551D-GM) by somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT). CFTRG551D-GM Ferret recapitulates the human CF disease phenotype and is also responsive to the CFTR potentiator VX-770.38 While this model is advantageous for testing CFTR gene replacement therapies, its use in testing gene editing is limited due to an ∼50% reduction in expression of G551D-CFTR mRNA from the targeted locus.

This reduction was caused by the insertion of the neo (neomycin resistance) expression cassette located in intron-13, which was needed to select HR-targeted mutant fibroblasts for SCNT following rAAV transduction. Thus, we developed the second generation ferret model (CFTRG551D-KI) containing a scarless G551D knock-in without an integrated antibiotic resistance gene using CRISPR-mediated mutagenesis in ferret zygotes. Of note, to maintain our capacity to use the same gRNA-G551D for the later gene editing studies and reduce the chances of altering mRNA secondary structure that might otherwise impact CFTR expression, we decided not to disrupt the gRNA-G551-targeted sequence in the mutagenesis oligo template.

In the mutagenesis template, there were three of the nucleotide differences from the WT CFTR sequence. Two of the base changes were used to covert the G551 codon to D551, a third base for silent mutation was placed in the G550 codon. These substitutions generated a new BclI restriction endonuclease site not present in the original G551 allele and facilitated genotype of G551D mutation by PCR and BclI digestion (Fig. 1A). The CRISPR approach demonstrated much higher efficiency to knock in the mutation than the previous method using rAAV-mediated HR.38 A total of 81 kits were born in 10 litters, of which 21 kits (25.9%) were positive for the G551D mutation. As expected, six kits that bore mutations in both CFTR alleles (G551D/G551D or G551D/indel) suffered from meconium ileus (complication of CF) and were euthanized.

Figure 1.

Generation of scarless G551D knock-in ferret model. (A) Schematic of the gene targeting and genotyping strategies. Red box indicates the mutagenesis ssOND template aligned to the homologous sequence at the CFTR locus. The difference in sequences between the G551D knock-in and the WT CFTR allele is outlined with lower cases red letters. The D551 codon in the donor ssOND template contains a BclI restrictive endonuclease site (red box) not contained with the WT allele. Gray arrows show the gRNA alignment to the ferret genomic sequence that recognizes both the WT and KI alleles while the red arrow marks the site of Cas9 cleavage (7-bp upstream of the G551 codon). Forward (Fw1) and reverse (Rev) primers used for amplification of the locus are marked by blue arrows. Example of genotypic analysis used to identify the G551D KI genotype (lanes 1 and 3), indicated by the BclI digestion of the PCR products. (B) Sequencing results of PCR amplified genomic DNA from founder animals. The PCR products positive for digestion by BclI were cloned into a plasmid pCR4blunt-Topo and 8 to 12 individual clones were randomly selected for Sanger sequencing. Shown are the representative sequence chromatographs from two kits, K7 and I8. Kit K7 was determined to be a G551D heterozygote, CFTRG551D-KI/WT, with two CFTR genotypes found (a precise G551D knock-in without undesired mutations and the WT G551 sequence). Kit I8 was a compounded heterozygote CF ferret with a CFTRG551D-KI/KO genotype (a precise G551D KI one allele and NHEJ-mediated mutation disrupting CFTR in the second allele). Of note, I8 was a chimera as two CFTR KO genotypes −5 and +1 were found at the non-G551D allele. (C) Short circuit current (Isc) measurements. Well-differentiated FAE-ALI cultures were generated from primary tracheal airway basal cells derived from a homozygous F2 offspring CFTRG551D-KI/G551D-KI (GKI) ferret. FAE-ALI were treated with 1 μM VX-770 (added apically) or mock-treated with DMSO (vehicle) during Ussing chamber analysis and compared to WT FAE-ALI cultures. Shown are the representative traces of the current changes of the VX770- or mock-treated GKI FAE-ALI cultures during the course of the experiment following the sequential addition of ion channel blockers (amiloride and DIDS), CFTR activators (Forsk and IBMX), and CFTR inhibitor (GlyH-101). (D) Quantification of Isc. Isc changes (ΔIsc) in response to each drug were calculated by subtracting the Isc before and after drug-addition. Data represent the means ± SEM (WT, N = 20; Mock treated, N = 14; VX770 treated, N = 20 transwells). Student's t-test was used for statistical comparison between the mock treated and VX770 treated groups. No statistically significant difference exists between the two means of the Isc changes in response to amiloride (p = 0.68) or DIDS (p = 0.40), but the changes in response CFTR activators (p < 0.0001) and CFTR inhibiter (p < 0.0001) are statistically significant. ALI, air–liquid interface; CF, cystic fibrosis; CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; DIDS, 4,4′-diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid; FAE, ferret airway epithelium; Forsk, forskolin; IBMX, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine; KO, knockout; NHEJ, nonhomologous end joining; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SEM, standard error of the mean; ssOND, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides; WT, wild-type; KI, knockin.

PCR products of the remaining 15 surviving kits were cloned into a plasmid pCR4blunt-Topo for Sanger sequencing. All of the 15 kits sequenced had at least one G551D mutations, and 10 kits (66.7%) also had undesired indels generated by nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ). For example, the kit I8 was a compounded heterozygote containing G551D and knockout genotypes, which evidently was a chimera and did not suffer from meconium ileus (Fig. 1B). Kit K7 was determined to have a heterozygote G551D mutation (CFTRG551D-KI/WT) with roughly equal reads of G551D-KI and WT sequences obtained and no undesired off-target mutations in either allele (Fig. 1B).

Of the total 21 kits born, there was a high frequency (76.2%) of simultaneous modification of both CFTR alleles (16 of 21 kits). Kit K7 animal was male and thus chosen as the founder for breeding expansion with WT ferrets (CFTRWT/WT). Germline transmission of the G551D mutation was confirmed in the F1 offspring. Further crossbreeding of F1 CFTRG551D-KI/WT male and female animals successfully generated F2 homozygote CFTRG551D-KI/G551D-KI ferrets (GKI ferrets).

To assess the function of G551D-CFTR in FAE, we seeded primary tracheal GKI basal cells onto Transwell inserts and polarized differentiated these cultures at an ALI. Following differentiation, short circuit currents (Isc) were measured in Ussing chambers following the sequential addition of non-CFTR ion channel antagonists, cAMP agonists (to activate CFTR), and CFTR inhibitor GlyH-101. Similar to CFTRG551D-GM cultures,38 GKI FAE-ALI cultures demonstrated a low basal level of Cl− current upon Forsk and IBMX stimulation, which was inhibited after the addition of GlyH-101. Treatment of GKI FAE-ALI cultures with VX-770, cAMP-induced Cl− current was enhanced 5.9-fold and achieved 66% that observed in WT FAE-ALI cultures (Fig. 1C, D). Thus, VX-770 potentiates gating of ferret G551D-CFTR in a similar manner to the human mutant.

HDR corrects the G551D mutation in CF ferret airway basal cells

Our main objective was to develop a model system for optimizing editing the CFTR G551D mutation in primary ferret airway basal cells for applications in autologous cell therapy. rAAV vectors are widely used as a gene transfer agent for human gene therapy. Although rAAV cannot accommodate all the components required for CRISPR-mediated HDR, due to its limited package capacity, it may be practical to use a dual-AAV delivery system39,40 (e.g., one AAV vector encoding Cas9 and second encoding the sgRNA expression cassette with donor HR template). To simplify variables that impact cotransduction and maximize the efficacy, we incorporated an spCas9 expression cassette into primary GKI basal cells using a lentivirus (LentCas9-Blast). This enabled studies to use a single rAAV vector [AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2)] for the gene-editing experiments (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Correction of the G551D CFTR mutation in ferret airway basal cells. (A) Schematic of the homologous sequences between the G551D allele and HR template within the rAAV vector. The AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) vector carries two sets of HR templates and gRNAs for dual-gene editing of CFTR and a mutant EGFP genes (the latter is described in subsequent figures). PCR primers for targeted amplicon sequencing are marked with arrows. Primer set HR-Fw/Rev or Fw1/Rev specifically amplified products from the ferret genomic DNA, not from the rAAV genome. G551DtgFw/G551DtgRev was an internal primer set used to amplify a 245 bp amplicon that was used for deep sequencing analysis of gene-edited alleles. The Cas9/gRNA-G551D complex recognized the same sequence in the original WT and G551D alleles (an aqua filled box marks the PAM sequence and the red arrow points to the cleavage site), but not the HR template where changes in six nucleotides (blue fonts, lower cases) reinstalled the D551 codon and eliminated the BclI site (open red box), as well as created a new BspEI site (open blue box) by silent substitutions. The G551 or D551 codon in the original WT allele, G551D allele, and the HR template are underlined. (B) Digestion of the PCR products by BclI or BspE1. Cas9-GKI basal cells were infected with rAAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) at an MOI of 50K DRP per cell. At 3 days postinfection, genomic DNA was extracted from infected or noninfected cells and PCR products were amplified using the primer sets HR-Fw/Rev or Fw1/Rev, as indicated. Shown is a gel of PCR products following digestion with BspE1, blue arrow points the digestion products, or with BclI, red arrow points the digestion products. BspE1 cleavage and lack of BclI cleavage indicate genome modification by HDR at the desired site. DRP, DNase I-resistant particles; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; HDR, homology-directed repair; HR, homologous recombination; MOI, multiplicity of infection; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif; rAAV, recombinant adeno-associated virus.

rAAV6 was the most efficient at transducing primary ferret airway basal cells in comparison to other AAV serotypes (rAAV1, rAAV2, rAAV5, rAAV8, and rAAV9, data not shown), with ∼90% transduction efficiency at an MOI of 5 × 104 DRP per cell. We infected Cas9-GKI cells with AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) and evaluated gene editing by PCR of genomic DNA compared to noninfected control cells. We used two primer sets that amplified CFTR exon-12 using flanking intronic sequences not contained in the rAAV HR template (Fig. 2A).

The two primer sets HR-Fw/Rev and Fw1/Rev produced 887 and 714 bp products, respectively, with gain of a BspEI site diagnostic for HDR events and loss of a BclI site diagnostic for HDR or indels produced by NHEJ (Fig. 2B). A small proportion of HDR was observed as evident by BclI cutting, while the fraction of PCR product that lost BclI cutting appeared more abundant was likely caused by indels at the target site (Fig. 2B).

To confirm correction of the G551D codon, we cloned the 887 bp PCR product and randomly picked 48 clones for Sanger sequencing. Of the total 43 readable sequences, 62.79% were unmodified, 23.26% contained indels surrounding the CRISPR cut site, and 13.95% had undergone HDR (Fig. 3A). Within the 13.95% of clones that converted the D551 codon to G551, there were no undesired mutations in exon-12 or the flanking intronic sequence and all retained the six nucleotide changes associated with the new BspE1 site. Of the 10 NHEJ/indel sequences, 4 were identical with one extra “T” insertion right at the CRISPR cut site, 2 sequences contained a 15 bp deletion, and other 4 harbored deletions of 1, 2, 4, and 11 bp.

Figure 3.

Next-generation sequence analysis G551D locus in gene editing Cas9-GKI airway basal cells. (A) Analyses of the target locus Sanger sequencing. The 887 bp PCR product using the primer set HR-Fw/Rev was cloned to pCR4Blunt-Topo. Analysis was based on 43 readable sequences from 48 randomly picked clones. (B–D) Analyses of the target locus using deep sequencing. A 245 bp amplicon for deep sequencing by NSG was produced by PCR using the 887 bp product as template and a nested internal primer set G551DtgFw/G551DtgRev. Reports were generated using the online tool CRISPResso2 to analyze 27,755,676 reads from the alignment to the reference sequences: (B) Summary of the variant analysis of the 27,010,538 aligned reads, (C) the mutation types in the reads of imperfect HDR G551 sequences, and (D) the mutation types in the reads of mutants with indels generated by NHEJ.

To further analyze sequence details of gene editing, a 243 bp amplicon containing CFTR exon-12 from the combined products of three biologic replicates was used for targeted gene next-generation sequencing (NGS) on an Illumina platform. NGS generated 27,755,676 reads for alignment with the reference sequences using CRISPResso2 (https://crispresso.pinellolab.partners.org). Among the total 27,010,538 aligned reads, 64.22% were unmodified sequences (G551D). Sequencing analyses demonstrated that 22.57% of modified alleles had indels generated at the cut site and 13.21% modified alleles contained the corrected G551 codon, of which 99.45% were perfectly corrected and 0.55% were associated with additional modifications (Fig. 3B).

Because of small sample size, Sanger sequencing was not able to reveal the imperfect G551 correction that accounted for 0.07% of the total aligned reads. This analysis also detailed the types of mutations that occurred with imperfect HDR (Fig. 3C) and NHEJ (Fig. 3D). Both were composed of various deletions, insertions, and substitutions, as well as the combinations of insertions and substitutions or deletions and substitutions. However, no combination of insertions/deletions or deletions/insertions/substitutions were found by NSG.

Of the total 6,098,062 sequences that incurred NHEJ, the majority were insertional mutations, which was 3.5-fold higher than those with deletions (76.26% vs. 21.71%). Very few reads (1.03%) contained substitutions. A recurrent +1 bp insertion at the CRISPR/Cas9 cut site was the most frequent genotype (75.31%) in all NHEJ mutants sequenced and accounted for nearly all (98.42%) of the insertional only mutants. The second most frequent NHEJ genotype (7.62%) was a −15 bp deletion. These +1 and −15 genotypes were also the majority of NHEJ mutants seen from Sanger sequencing.

By contrast, the mutations, including substitution (34.90%), deletion (32.48%), and their combination were more frequently seen in the imperfect HDR reads, while insertion only mutations accounted for only 18.54%. As there was no major recurrent genotype found for the imperfect HDR reads, we reasoned the cause to be random errors from DNA synthesis during HDR or artifacts from the PCR amplification, although the error rate using high fidelity Taq polymerase was expected to be minimal.

Dual-gene editing in CF ferret airway basal cells

The high rate of NHEJ mutations suggested the need to improve CRISPR-mediated gene correction of airway basal cells. As CFTR expression is silent in basal cells, an easily assessable reporter would be extremely useful for approach optimization. We hypothesized that coediting at a second reporter locus would be enriched in basal cells correctly edited at the CFTR locus. Previously, we used the EGFPY66S as reporter to indicate the gene correction using RNA-mediated and rAAV-mediated HR in transformed cells and primary cells of transgenic mice.30,33 This reporter harbors a single base substitution at the Y66 codon [TAC (tyrosine)→TCC (serine)] in the EGFP cDNA and rendered the mutant protein nonfluorescent. Repair of this mutation restores fluorescence to the EGFP protein.30,33

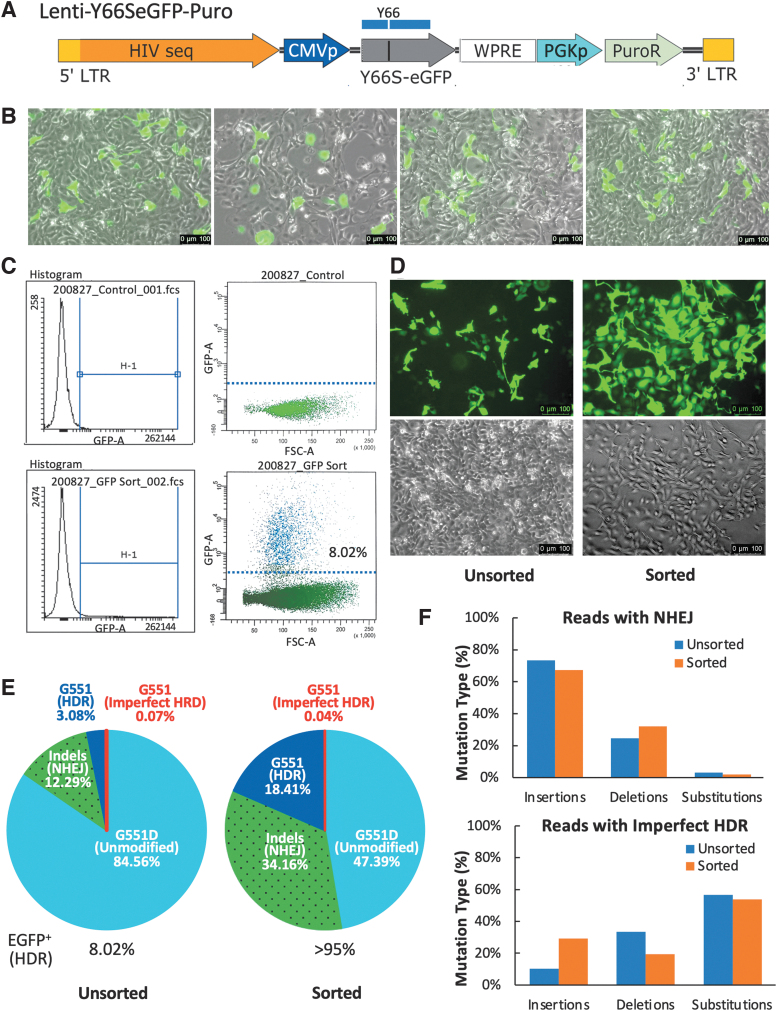

In this study, Cas9-GKI basal cells were transduced with Lenti-Y66SeGFP-Puro lentivirus (Fig. 4A) and double-resistant polyclonal pools of cells (Y66S-Cas9-GKI) were obtained following a week selection with blasticidin S and puromycin. To validate the gene-editing approach, Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells were then transduced with the rAAV vector harboring both CFTR-G551 and EGFP-Y66 homology templates and two gRNA expression cassettes targeting both mutations [AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2)]. Restoration of EGFP fluorescence was visible 1 day following infection and ∼10% cells recovered fluorescence by 3 days postinfection (Fig. 4B). At 10 days postinfection, FACS analysis demonstrated that 8.02% of Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells had recovered EGFP fluorescence (Fig. 4C). The viable green cells (EGFPY66-corrected) were collected by FACS were put back in culture.

Figure 4.

Dual-correction of the CFTRG551D and EGFPY66S in ferret airway basal cells. (A) Lenti-Y66SeGFP-Puro. Blue box indicates the region of truncated EGFP-630 sequence used for the HR template within rAAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2). (B) The restoration of EGFP fluorescence in rAAV-infected Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells. Images were captured at 3-days postinfection before transferring the infected cells onto 100-mm dish for expansion. The corrected rate (9.5% ± 1.6%) was estimated by counting the numbers of green cells over the total cells from four randomly picked images as shown. (C) FACS. The correction efficiency of EGFPY66S was determined by FACS and analyzed using FlowJo™ v10.8.1 (Ashland, OR). (D) Representative images of the unsorted cells and Y66S-corrected cells recovered by FACS. Images were captured 12 days post-rAAV infection (2 days after FACS), before seeding onto Transwell® inserts for FAE-ALI cultures. (E, F) Analyses of deep sequencing results at the G551D locus for the unsorted and sorted cells. (E) Summary of the alignments and (F) the mutation types in the reads of imperfect HDR G551 sequences and mutants with indels generated by NHEJ. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

We also continued to culture a small fraction (1/10th) of unsorted cells. The purity and expansion of sorted fraction were checked visually 2 days after sorting. As expected, >95% cells were strongly fluorescent (Fig. 4D). There was no notable difference of EGFP-positive cells at 3 and 12 days postinfection for unsorted cells (Fig. 4B vs. D). Both sorted and unsorted populations were then seeded onto separate Transwell inserts to generate polarized FAE-ALI cultures and noninfected Y66S-Cas9-GKI FAE-ALI cultures were also generated as controls. Genomic DNA was extracted from the remaining portion of unsorted and sorted AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2)-infected basal cells for PCR to obtain the 243 bp amplicon for NGS as described above for rAAV-infected Cas9-GKI cells.

Analyses of the deep sequencing data revealed that the G551 (HDR-corrected, including imperfect HDR) sequences accounted for 3.15% of the total reads from the unsorted cell population and 18.45% of the total aligned reads from FACS-sorted EGFP fluorescent populations (Fig. 4E). Similar to the analyses of the Cas9-GKI cells, insertional mutations at the G551D locus were most common results of NHEJ and substitution mutations were the most common result of imperfect HDR reads, in both the sorted and unsorted cell populations (Fig. 4F). The ∼6-fold enrichment of the G551 sequences in the EGFP fluorescent basal cells suggests a high frequency of simultaneous HDR at the two genetic loci. However, in both the unsorted (U) and sorted (S) populations, HDR correction of EGFPY66S (U 8.02% vs. S > 95%) was more efficient than that at the CFTR locus (U 3.15% vs. S 18.45%, including imperfect HDR sequences) (Fig. 4E).

The lower correction rate of CFTRG551D in unsorted Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells (3.15%), compared to unsorted Cas9-GKI basal cells (13.21%), suggests the possibility of HDR substrate competition, since one rAAV genome was used for HDR at both sites. This hypothesis is supported by a larger difference in the abundance of NHEJ-related versus HDR-related sequences in the unsorted Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells (3.9-fold; 12.29% vs. 3.15%, respectively), compared to gene editing of just CFTR in Cas9-GKI basal cell (1.7-fold; 22.57% vs. 13.21%, respectively). With a 11.8-fold enrichment in EGFP fluorescent HDR-corrected basal cells by FACS and a 3.15% frequency of CFTR HDR events in unsorted basal cells, if all the CFTR HDR events were within EGFP+ sorted basal cells, the frequency of HDR at the CFTR locus would have been 37% (11.8-fold enrichment × 3.15% CFTR HDR).

Given that the observed frequency of CFTR HDR in EGFP+ sorted basal cells was 18.45%, we estimate that ∼50% of the CFTR HDR events occurred in nonfluorescent basal cells, and the HDR efficiency at the CFTR gene was ∼50% less than that at the eGFP gene.

Correction of CFTR function in CRISPR-edited differentiated ferret airway basal cells

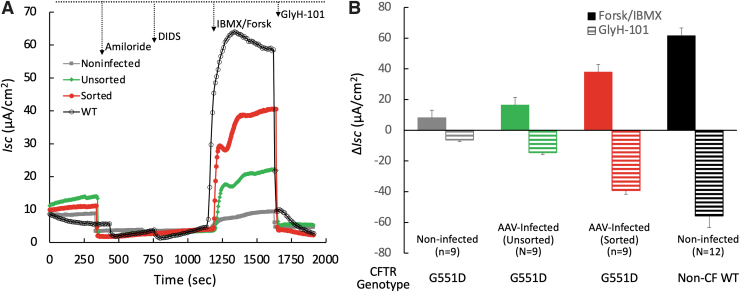

To assess functional correction of CFTR in gene-edited basal cells, rAAV-infected Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells (FACS-sorted and unsorted) were used to generate differentiated FAE-ALI cultures. FAE-ALI cultures generated from noninfected Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells were used as control. CFTR-mediated short circuit current (Isc) was then assessed on differentiated cultures in Ussing chambers. Typical traces of the Isc from three different types of FAE-ALI cultures are presented in Fig. 5A. These traces demonstrated expected responses to non-CFTR ion channel antagonists, cAMP agonists, and CFTR inhibitor, indicating that the manipulations of lentiviral and rAAV vectors infections in ferret airway basal cells did not alter their ability to differentiate into a functional pseudostratified epithelium.

Figure 5.

Partial functional correction of CFTR-mediated Cl− transport in polarized epithelial cultures derived from gene-edited Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells. (A) Representative Isc traces from Ussing chamber studies. Channel antagonists and agonists were sequentially added during the experiment as marked: (1) Amiloride (ENaC channel blocker), (2) DIDS (Non-CFTR anion channel blockers), (3) Forsk and IBMX (CFTR activators), and (4) GlyH-101 (CFTR inhibitor). (B) Quantitation of CFTR channel function. CFTR-mediated Cl− transport was quantified as the ΔIsc following activation by forsk/IBMX and inhibition by GlyH101. The non-CF (WT) cultures were established from P12 and P14 expanded WT ferret tracheal basal cells. Data represent the means ± SEM (N is indicated for each group).

CFTR-mediated Cl− conductance was quantitated as the change in Isc (ΔIsc) following the addition of cAMP agonists and the CFTR inhibitor GlyH101 (Fig. 5B). ΔIsc-GlyH101 responses from noninfected Y66S-Cas9-GKI cultures were 11.3% that of non-CF FAE-ALI cultures. This low level of Cl− channel activity was similar to that observation in FAE-ALI cultures derived from the original GKI basal cell stock (Fig. 1C). We observed increased CFTR-mediated Isc in FAE-ALI cultures from both two populations of the rAAV-infected Y66S-Cas9-GKI basal cells. FAE-ALI cultures derived from unsorted Y66S-Cas9-GKI edited basal cells demonstrated 2.3-fold higher ΔIsc-GlyH101 responses than control unedited cultures. Although the rate of G551D correction in this cell population was only 3.08%, this gave rise to 26.0% of the ΔIsc-GlyH101 observed in non-CF cultures.

FAE-ALI cultures derived from sorted EGFPY66-corrected basal cells with 18.4% G551 correction demonstrated 70.4% functional rescue in CFTR activity (ΔIsc-GlyH101) compared to non-CF cultures. The 6.2-fold increase ΔIsc-GlyH101 responses was comparable to the improvement achieved by treatment with the CFTR potentiator VX770 (5.9-fold, Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

Previously, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 approach to manipulate the ferret genome in zygotes, through which we successfully knocked in a CRE-responsive reporter expression cassette into a predetermined site at the ROSA locus via homology-independent targeted integration (HITI), which utilizes a NHEJ repair mechanism.27 In this study, the CRISPR/Cas9 approach was utilized to facilitate the mutagenesis by HDR to generate a scarless CFTRG551D-KI knock-in ferret. Of note, we observed a high rate of simultaneous modification in both two CFTR alleles, with NHEJ-mediated mutations in two-thirds of the G551D-KI kits. These undesired mutations were found in both the non-HDR allele and the allele bearing the G551D mutation, indicating that NHEJ-mediated mutagenesis was highly efficient even when the HR template was provided.

Ongoing studies are evaluating the phenotype of homozygous CFTRG551D-KI ferrets. Here, we sought to generate vector tools and model systems to evaluate the efficiency of gene editing ferret CFTRG551D with the eventual goal of applying this technology in vivo in the ferret model.

While HDR was effective in proliferating airway epithelial cells, the observed 13.21% correction rate of the G551D mutation by HDR (including imperfect HDR events) was lower than the undesired mutagenesis rate (22.57%) caused by NHEJ in the Cas9-GKI basal cells. Thus, basal cell NHEJ mechanism appears to dominate over HR when rAAV is harboring the HR template. This was similar to that observed in RNP/ssODN-injected ferret zygotes, where HDR corrected the G551D mutation at one allele, but mutated the second CFTR allele by NHEJ. Modulation of cellular DNA repair pathways to favor HDR over NHEJ could improve gene editing efficiencies. Several approaches using chemical and genetic modulation have proposed for enhancing HDR pathways,41 such as inhibiting the key enzymes and proteins involved in NHEJ,42–44 directly modulating the HDR pathway,45,46 and overexpressing RAD52 and dn53BP1,47 or RAD18 (a ubiquitin ligase involved in HDR and post-DNA replication repair).48

Semi high-throughput combinatorial screening using chemical and/or genetic agents that modulate these NHEJ and HDR pathways would benefit from the mutant EGFP reporter system we reported here. Thus, we created a system capable of rapidly evaluating HDR efficiencies at two loci in primary basal cells, while reducing the variables associated with codelivery of a Cas9-expressing rAAV vector. The rAAV vector and Y66S-Cas9-GKI reporter basal cells developed here constitute such a model system for the optimization HDR approaches.

Our study was conducted in polyclonal pools of Cas9-expressing GKI basal cells, a requirement for the maintenance of CFTR function following differentiation. The difference in HDR correction rates for G551D (3.15%) and Y66S (8.02%) in the total population of unsorted rAAV-infected Y66S-Cas9 GKI basal cells could be due to many factors, but not the level of Cas9 expression or rAAV infection, given that a Cas9 expression cassette was integrated into the genome and a single rAAV vector harbored both HR templates. The high frequency of simultaneous gene editing at two loci (52.61% of CFTR mutagenesis rate in the EGFPY66S-corrected cells, of which 18.45% was from HDR) suggests that inefficient cleavage by Cas9/gRNA-G551D was unlikely responsible for the lower HDR rate.

Factors that may have impacted lower HDR rates of CFTR may include target gene location in the genome, its epigenetic landscape, and/or nuclear three-dimensional topology, which could differentially impact access of the HR template to the EGFP and CFTR loci. Of note, the lentiviral integration of the Y66S-EGFP cassette was random and studies have shown that lentiviruses preferentially integrate into regions of transcriptionally active chromatin.49 Thus, FACS isolation of EGFP fluorescent basal cells could have enriched for HDR events if they occurred more efficiently at transcriptionally active loci. However, since the CFTR gene is silent in basal cells and HDR events at the CFTR locus were enriched sixfold in EGFP fluorescent basal cells, this cannot completely explain the discrepancy in editing at the two loci.

Previous studies have attempted to site-specifically integrate a CFTR minigene via HDR in airway epithelial cells using helper-dependent adenoviral vectors (HD-Ad) to deliver both the donor template and programmable nuclease (CRISPR/Cas9 or TALENs) within the same vector.50,51 These studies have shown that the vector genome is unstable following nuclease excision of the donor template, thus limiting availability for effective HDR. This is also likely true for the application of rAAV vectors. Thus, a rAAV genome harboring two HR templates may not be capable of participating in two HDR events. Indeed, when AAV2/6.tempG551Y66-gRNA(2) was used to correct only the G551D mutation in Cas9-GKI cells, a 13.21% (including imperfect HDR events) correction rate was achieved—a rate much higher than the 3.15% correction of CFTRG551D observed in Y66S-Cas9-GKI cells where dual correction was conducted using the same construct.

However, in Y66S-Cas9-GKI cells, the combined HDR rate at both CFTRG551D and EGFPY66S loci (11.17%) was more similar to the single CFTR targeting approach in Cas9-GKI cells (13.21%).

Another hypothesis to explain differences in editing efficiency of EGFP and CFTR could be substrate competition, which may have led to more favorable homology recombination at the EGFPY66S loci in the same infected cell because the GC content of the HR template for EGFP correction is much higher than that for CFTR (74% vs. 38%). In support of this hypothesis, higher GC content has been reported to elevate mutation and recombination rates in the yeast and the efficiency of gene editing positively correlates with GC content at the target sites.52,53

A third possible explanation of the higher correction rate of EGFPY66S is the potential for multiple lentiviral vector integration events. We used an MOI of 1.5 TU/cell for lentiviral infection and would thus expect EGFPY66S alleles to be less than the two CFTR copies per cell. However, it is possible that puromycin selection enriched cells with multiple copies of the EGFPY66S expression cassette.

A previous study in primary human airway basal cells derived from ΔF508/ΔF508 CF airways has reported that Zinc-finger nucleases-mediated HDR using transfected ssOND or rAAV6-delivered as the HR templates can achieve ∼10.6% and ∼31.0% gene editing efficiency at the ΔF508-CFTR locus, respectively, for edited cells.54 When differentiated into ALI cultures, these cells produced ∼15% (ssOND) and ∼40% (rAAV) cAMP-inducible CFTR Cl− currents observed in non-CF ALI cultures, suggesting a direct correlation between gene-editing frequency and restoration of CFTR current.54 By contract, our study comparing unsorted and sorted (EGFP-targeted enriched) populations of CFTR gene-edited ferret basal cells demonstrated greater CFTR functional correction than gene editing frequency. For example, ALI cultures derived from unsorted basal cells with a 3.1% gene-editing frequency produced 15.6% and 16.7% of the WT ΔIsc Cl− responses to cAMP and GlyH101 treatment, respectively, when baseline currents in unedited parental CF cultures were subtracted from values.

This represents a 5.1- to 5.4-fold greater functional correction than gene-editing frequency. This was also true for sorted ALI cultures, for which functional restoration of CFTR-mediated Cl− transport was 3.0- and 3.6-fold greater than gene-editing frequency for cAMP and GlyH101 responses, respectively. The reason for this difference in the correlation of gene editing frequency versus CFTR functional correction in our study versus those by Suzuki et al.54 remains unclear, but could involve the persistence of certain CFTR-expressing lineages in human versus ferret primary basal cell cultures and their mechanisms of involvement in CFTR-mediated anion conductance.11

Consistent with our findings, others have shown that ALI cultures derived from mixtures of non-CF and ΔF508/ΔF508 primary human airway epithelial cells at a 2:8 ratio (WT:CF) restore ∼70% CFTR-mediated Cl− transport of those 100% WT cultures.55

The ability to correct mutations at an endogenous locus is leading to a new era of personalized medicine. Although gene-editing therapy for CF lung disease is still at a very early stage, many promising approaches are being pursued. Such approaches include HDR,54,56 HITI,54 base editors,57 prime editing,58 and programmable nuclease-mediated integration of a CFTR minigene expression cassette into a genome safe harbor or the CFTR locus.50,51 These approaches are being applied in vitro in primary airway basal cells, iPSCs, and organoid cultures derived from CF patients and demonstrated proof-of-concept for gene therapy. While the CF animal models are ready to facilitate this research toward in vivo gene editing of the lung, the availability of effective airway vectors for delivery of the CRISPR components remains a challenge.

Additional challenges include the fact that HDR is highly cell cycle dependent. Most vector-accessible epithelial cells in the airways are mitotically quiescent and do not support efficient HDR. HITI, base editors, and prime editing are possible solutions to correct mutations in nondividing cells, including quiescent differentiated airway epithelial cells. Although the turnover rates of the human airway epithelial cells remain unclear, terminally differentiated ciliated cells of the mouse airways have a half-life of ∼17 months.23 Since ciliated cells do not express CFTR,16 they are not a viable target for CFTR gene editing. However, if vectors were available to efficiently target secretory cells or pulmonary ionocytes, CFTR gene editing could produce durable functional complementation if these cell types have similar lifespans as ciliated cells.

Nevertheless, permanent correction will only be achieved if stem cell compartments are efficiently targeted (i.e., basal cells in the proximal airways and club cells in the bronchioles).59 Efficient in vivo rAAV transduction of basal cells has yet to be achieved, due to a lack of an exposed apical membrane. However, method of transiently disrupting the columnar cell tight junctional barrier with l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine has proven effective in facilitating basal cell transduction with HD-Ad vectors in multiple species.51,60,61 The large package capacity of HD-Ad is also compatible with single vector applications of current CRISPR-mediated gene-editing systems. Although it is more challenging to edit quiescent basal progenitor cells in vivo, compared to proliferating cells in vitro, the development of robust delivery systems capable of efficient basal cell targeting and correction will translate the current proof-of-concept studies into real therapies for CF patients.

Efficient HDR-based ex vivo CFTR gene editing in airway basal cells is the first step in applying autologous cell-based therapy to the CF airway. Additional requirements for efficient cell-based therapy include maintenance of multipotency during ex vivo expansion, tractable methods of engraftment, and long-term persistence in the recipient airways. Toward this goal, we present the creation of a new CFTRG551D ferret model for which differentiated airway cultures are responsive to the CFTR potentiator VX-770. Our study demonstrates that CFTR gene-editing correction in a small fraction of airway basal cells can restore ∼3- to 6-fold greater functional correction of CFTR than the gene-editing frequency.

Given that NHEJ dominated HR in the presence of a donor rAAV template and CRISPR/Cas9 components, improvements in the current gene-editing approach of proliferating airway basal cells are required before cell therapy applications in the G551D ferret model. The developed primary cell system with an HDR reporter may be useful in optimizing and studying the cell-intrinsic properties responsible for efficient gene editing in primary basal cells.

AUTHORs' CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.Y. and J.F.E. conceived and designed the experiments. K.V., Z.F., S.Y.P., S.C., Y.Z., M.W., and X.S. performed the experiments. X.S. contributed to zygote microinjection and NSG data analysis. Z.Y. and J.F.E. wrote the article. All authors contributed to data analysis, edited the article, and approved submission.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE

No competing financial interests exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health P30 DK054759, P01 HL152960, R01 HL165404, and Federal Contract #75N92019R0014 to John F. Engelhardt, a grant from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to John F. Engelhardt, and a research grant YAN19XX0 from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation to Ziying Yan.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rommens JM, Iannuzzi MC, Kerem B, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: chromosome walking and jumping. Science 1989;245:1059–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pezzulo AA, Tang XX, Hoegger MJ, et al. Reduced airway surface pH impairs bacterial killing in the porcine cystic fibrosis lung. Nature 2012;487:109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kunzelmann K, Schreiber R, Hadorn HB. Bicarbonate in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2017;16:653–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stoltz DA, Meyerholz DK, Welsh MJ. Origins of cystic fibrosis lung disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1574–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Middleton PG, Mall MA, Drevinek P, et al. Elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis with a single Phe508del allele. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1809–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clancy JP, Cotton CU, Donaldson SH, et al. CFTR modulator theratyping: current status, gaps and future directions. J Cyst Fibros 2019;18:22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooney AL, Abou Alaiwa MH, Shah VS, et al. Lentiviral-mediated phenotypic correction of cystic fibrosis pigs. JCI Insight 2016;1:e88730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steines B, Dickey DD, Bergen J, et al. CFTR gene transfer with AAV improves early cystic fibrosis pig phenotypes. JCI Insight 2016;1:e88728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yan Z, Stewart ZA, Sinn PL, et al. Ferret and pig models of cystic fibrosis: prospects and promise for gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2015;26:38–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guggino WB, Cebotaru L. Gene therapy for cystic fibrosis paved the way for the use of adeno-associated virus in gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2020;31:538–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tang Y, Yan Z, Engelhardt JF. Viral vectors, animal models, and cellular targets for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis lung disease. Hum Gene Ther 2020;31:524–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yan Z, McCray PB Jr., Engelhardt JF. Advances in gene therapy for cystic fibrosis lung disease. Hum Mol Genet 2019;28:R88–R94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alton EW, Beekman JM, Boyd AC, et al. Preparation for a first-in-man lentivirus trial in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2017;72:137–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang Q, Engelhardt JF. Cellular heterogeneity of CFTR expression and function in the lung: implications for gene therapy of cystic fibrosis. Eur J Hum Genet 1998;6:12–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang L, Button B, Gabriel SE, et al. CFTR delivery to 25% of surface epithelial cells restores normal rates of mucus transport to human cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. PLoS Biol 2009;7:e1000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montoro DT, Haber AL, Biton M, et al. A revised airway epithelial hierarchy includes CFTR-expressing ionocytes. Nature 2018;560:319–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Plasschaert LW, Zilionis R, Choo-Wing R, et al. A single-cell atlas of the airway epithelium reveals the CFTR-rich pulmonary ionocyte. Nature 2018;560:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jinek M, Chylinski K, Fonfara I, et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012;337:816–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 2013;154:1380–1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cox DB, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: prospects and challenges. Nat Med 2015;21:121–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frangoul H, Altshuler D, Cappellini MD, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia. N Engl J Med 2021;384:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gillmore JD, Gane E, Taubel J, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2021;385:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rawlins EL, Hogan BL. Ciliated epithelial cell lifespan in the mouse trachea and lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;295:L231–L234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rock JR, Onaitis MW, Rawlins EL, et al. Basal cells as stem cells of the mouse trachea and human airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:12771–12775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hong KU, Reynolds SD, Watkins S, et al. In vivo differentiation potential of tracheal basal cells: evidence for multipotent and unipotent subpopulations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L643–L649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hajj R, Baranek T, Le Naour R, et al. Basal cells of the human adult airway surface epithelium retain transit-amplifying cell properties. Stem Cells 2007;25:139–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yu M, Sun X, Tyler SR, et al. Highly efficient transgenesis in ferrets using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homology-independent insertion at the ROSA26 locus. Sci Rep 2019;9:1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods 2014;11:783–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campeau E, Ruhl VE, Rodier F, et al. A versatile viral system for expression and depletion of proteins in mammalian cells. PLoS One 2009;4:e6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tran ND, Liu X, Yan Z, et al. Efficiency of chimeraplast gene targeting by direct nuclear injection using a GFP recovery assay. Mol Ther 2003;7:248–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Choi SH, Reeves RE, Romano Ibarra GS, et al. Detargeting lentiviral-mediated CFTR expression in airway basal cells using miR-106b. Genes (Basel) 2020;11:1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yan Z, Lei-Butters DC, Keiser NW, et al. Distinct transduction difference between adeno-associated virus type 1 and type 6 vectors in human polarized airway epithelia. Gene Ther 2013;20:328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu X, Yan Z, Luo M, et al. Targeted correction of single-base-pair mutations with adeno-associated virus vectors under nonselective conditions. J Virol 2004;78:4165–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu X, Luo M, Guo C, et al. Comparative biology of rAAV transduction in ferret, pig and human airway epithelia. Gene Ther 2007;14:1543–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yan Z, Sun X, Evans IA, et al. Postentry processing of recombinant adeno-associated virus type 1 and transduction of the ferret lung are altered by a factor in airway secretions. Hum Gene Ther 2013;24:786–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zabner J, Smith JJ, Karp PH, et al. Loss of CFTR chloride channels alters salt absorption by cystic fibrosis airway epithelia in vitro. Mol Cell 1998;2:397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan Z, Keiser NW, Song Y, et al. A novel chimeric adenoassociated virus 2/human bocavirus 1 parvovirus vector efficiently transduces human airway epithelia. Mol Ther 2013;21:2181–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sun X, Yi Y, Yan Z, et al. In utero and postnatal VX-770 administration rescues multiorgan disease in a ferret model of cystic fibrosis. Sci Transl Med 2019;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liang SQ, Walkey CJ, Martinez AE, et al. AAV5 delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 supports effective genome editing in mouse lung airway. Mol Ther 2022;30:238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yan Z, Lynch TJ, Engelhardt JF. AAV-mediated gene editing lights up the lung. Mol Ther 2022;30:7–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu M, Rehman S, Tang X, et al. Methodologies for improving HDR efficiency. Front Genet 2018;9:691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maruyama T, Dougan SK, Truttmann MC, et al. Increasing the efficiency of precise genome editing with CRISPR-Cas9 by inhibition of nonhomologous end joining. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:538–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chu VT, Weber T, Wefers B, et al. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol 2015;33:543–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Canny MD, Moatti N, Wan LCK, et al. Inhibition of 53BP1 favors homology-dependent DNA repair and increases CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing efficiency. Nat Biotechnol 2018;36:95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song J, Yang D, Xu J, et al. RS-1 enhances CRISPR/Cas9- and TALEN-mediated knock-in efficiency. Nat Commun 2016;7:10548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pinder J, Salsman J, Dellaire G. Nuclear domain ‘knock-in’ screen for the evaluation and identification of small molecule enhancers of CRISPR-based genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res 2015;43:9379–9392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Paulsen BS, Mandal PK, Frock RL, et al. Ectopic expression of RAD52 and dn53BP1 improves homology-directed repair during CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat Biomed Eng 2017;1:878–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nambiar TS, Billon P, Diedenhofen G, et al. Stimulation of CRISPR-mediated homology-directed repair by an engineered RAD18 variant. Nat Commun 2019;10:3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ciuffi A. Mechanisms governing lentivirus integration site selection. Curr Gene Ther 2008;8:419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xia E, Zhang Y, Cao H, et al. TALEN-mediated gene targeting for cystic fibrosis-gene therapy. Genes (Basel) 2019;10:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou ZP, Yang LL, Cao H, et al. In vitro validation of a CRISPR-mediated CFTR correction strategy for preclinical translation in pigs. Hum Gene Ther 2019;30:1101–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sun Y, Zhang B, Luo L, et al. Systematic genome editing of the genes on zebrafish Chromosome 1 by CRISPR/Cas9. Genome Res 2019;30:118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kiktev DA, Sheng Z, Lobachev KS, et al. GC content elevates mutation and recombination rates in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:E7109–E7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Suzuki S, Crane AM, Anirudhan V, et al. Highly efficient gene editing of cystic fibrosis patient-derived airway basal cells results in functional CFTR correction. Mol Ther 2020;28:1684–1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Farmen SL, Karp PH, Ng P, et al. Gene transfer of CFTR to airway epithelia: low levels of expression are sufficient to correct Cl- transport and overexpression can generate basolateral CFTR. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;289:L1123–L1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vaidyanathan S, Salahudeen AA, Sellers ZM, et al. High-efficiency, selection-free gene repair in airway stem cells from cystic fibrosis patients rescues CFTR function in differentiated epithelia. Cell Stem Cell 2020;26:161–171.e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krishnamurthy S, Traore S, Cooney AL, et al. Functional correction of CFTR mutations in human airway epithelial cells using adenine base editors. Nucleic Acids Res 2021;49:10558–10572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Geurts MH, de Poel E, Pleguezuelos-Manzano C, et al. Evaluating CRISPR-based prime editing for cancer modeling and CFTR repair in organoids. Life Sci Alliance 2021;4:e202000940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. King NE, Suzuki S, Barilla C, et al. Correction of airway stem cells: genome editing approaches for the treatment of cystic fibrosis. Hum Gene Ther 2020;31:956–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cao H, Ouyang H, Grasemann H, et al. Transducing airway basal cells with a helper-dependent adenoviral vector for lung gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther 2018;29:643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bandara RA, Chen ZR, Hu J. Potential of helper-dependent Adenoviral vectors in CRISPR-cas9-mediated lung gene therapy. Cell Biosci 2021;11:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]