Abstract

Objective:

Patient satisfaction is an increasing priority for health care facilities in ensuring reimbursement for services, high-quality access to care, and transparent communication. Cumulatively, these metrics guide patient-centered care and facilitate optimal service delivery. The purpose of this scoping review was to evaluate measures of patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments.

Materials and Methods:

This scoping review was guided by the Arksey and O'Malley methodological framework. Analysis was performed based on the multidimensional hierarchical model of perceived service-quality conceptual framework. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement was used to organize included publications and to display search processes in a flow diagram. An academic reference librarian conducted a literature search, using electronic databases that included PubMed,® Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, EMBASE,® and Web of Science.

Results:

A total of 384 publications were initially identified and screened; 26 met the eligibility criteria and were included in the synthesis. Discrepancies in the use of patient-satisfaction measures among studies were found in only 1 study demonstrating holistic assessment.

Conclusions:

There is a need for consistent measurement of patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments. Future studies may evaluate development of a satisfaction tool to measure patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments comprehensively.

Keywords: acupuncture, acupressure, patient satisfaction, questionnaire, surveys, scales

INTRODUCTION

Focus on patient satisfaction with health care has steadily increased throughout the past decade. Patient-satisfaction surveys are considered to be indicators of health care quality worldwide. Thus, health care organizations as well as scientific studies administer these instruments to patients to gain an understanding of consumers' experiences of health care, encompass patient perspectives in care delivery, and improve patient outcomes.1 Within the growing health care competitive marketplace, hospitals use patient-satisfaction measures to reimburse providers and to build patient loyalty.2 Patients publicly report their reviews online about their experiences within health care systems and about encounters with providers. The transparency of patients' subjective judgments increases competition among health care services, providers, and systems.

Patient satisfaction has been researched extensively; however, there is often a need for standardized instruments within specialty health care services (such as acupuncture) to facilitate scientific conclusions.3–5 Often, satisfaction measures lack validated psychometric properties, and surveys are developed by investigators for studies.4 To confound this issue, the definition of patient satisfaction is not consistent. For example, the measurement of satisfaction with acupuncture pain treatments have been assessed with pain scores post-treatment,6–14 satisfaction with pain control,15,16 satisfaction with levels of sedation,17 and the effect pain has on both a patient's ability to cope and that patient's quality of life.18–20 Other measures of patient satisfaction are overall contentment with treatment delivery, including the setting in which treatment occurred,21 interaction with health care providers,22 and technique of the individual who delivered the care.23–25

Often, these measurements are not informed by theory or conceptual frameworks and lack scientific methodologies. This review was guided by the following question: “What is known from existing research about the measurement of patient satisfaction for acupuncture services?” The purpose was to identify a need for developed measures and inform quantitative tools to be used for acupuncture research on patient satisfaction.

Conceptual Framework

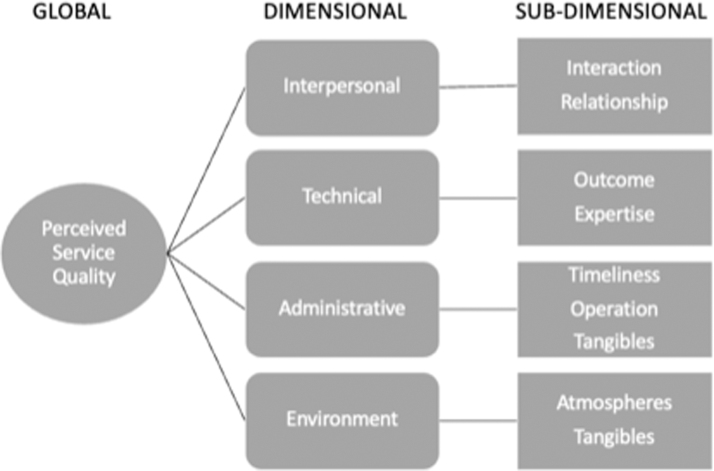

Dagger et al. developed the Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality (HMHSQ) conceptual model to guide health care metrics in evaluating efforts to improve patient satisfaction.26 The HMHSQ conceptual model encompasses varying dimensions and levels in which patients assess heath care services (Fig. 1). The framework is comprised of 3 overarching levels: (1) global; (2) dimensional; and (3) sub-dimensional. Each level of the model differentiates and coincides with dimensional (interpersonal, technical, administrative, environment) and sub-dimensional categories (interaction, relationship, outcome, expertise, timeliness, operation, tangibles, atmosphere) to include all services a patient experiences and evaluates.4,16,26 The HMHSQ conceptual framework was utilized to evaluate each of the studies included in this review to inform development of a uniform measure that may be utilized in future research to assess patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments globally.

FIG. 1.

Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality conceptual model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

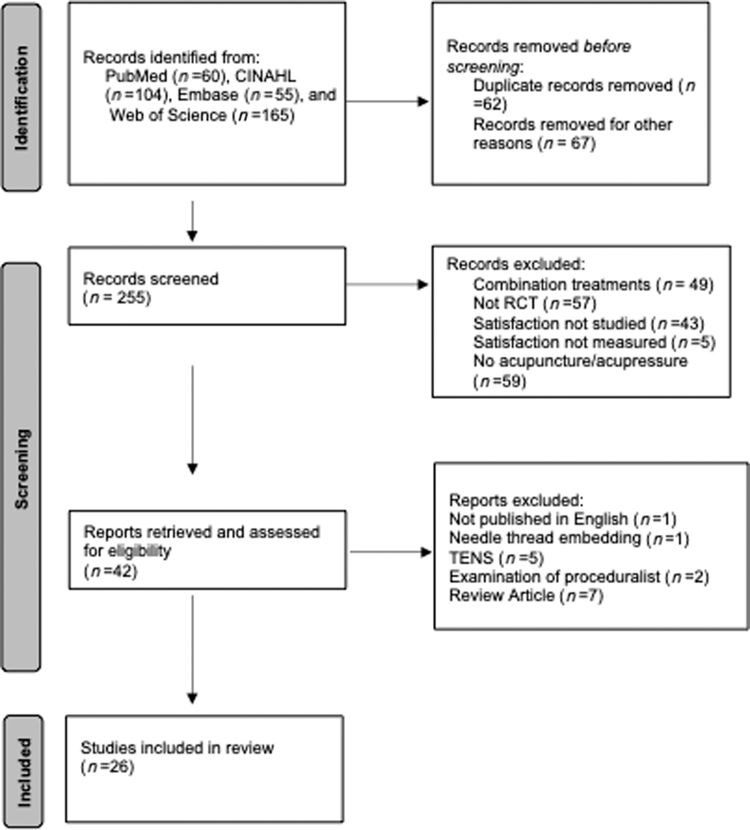

Given the variability in existing literature on patient-satisfaction measures targeting acupuncture services, a scoping review was conducted. Scoping reviews facilitate a comprehensive summary of evidence to inform practice and recommend future research directives.27 The Arksey and O'Malley28 methodological framework guided this scoping review, with enhancements directed by Colquhoun et al. and Levac et al.27,29 This 5-stage approach was initiated with a broad research question, identification of relevant studies, selection of applicable studies, data charting, and a summary of results.28 The search strategy was developed and implemented by a medical librarian at the Annette and Irwin Eskind Family Biomedical Library at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, and included the following databases: PubMed®; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; EMBASE®; and Web of Science. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework guided the organization of selected publications and the display of the search process within a flow diagram (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.

The authors developed a study protocol to establish inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening. Three reviewers conducted the initial screening independently and all selected studies for inclusion were reviewed by the lead author. Identified studies were limited to acupuncture studies that reported on patient satisfaction. Included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in English during the past 10 years in scholarly peer-reviewed journals. Studies utilizing needle acupuncture, electroacupuncture (EA), or acupressure were included for analysis.

The rationale for excluded nonrandomized studies (n = 57) was to ensure thorough assessment of level-one evidence. Interventions with combination treatments, such as acupuncture + massage, were excluded. Upon full-text review, studies missing details on patient satisfaction measures were also excluded.

A combination of the following search terms was used for each database: acupuncture; acupressure; electroacupuncture; acupoint; patient satisfaction; questionnaire; surveys; and scales.

A data-charting matrix was developed to organize selected studies for analysis as directed by Arksey and O'Malley28 (Supplementary Table S1; supplementary data are available online at www.liebertonline.com/ACU). Information was recorded and categorized into the following groups: study citation; design; aim; acupuncture treatment; sample and setting; survey utilized for satisfaction measure; level of HMHSQ; and findings. The HMHSQ conceptual model was utilized to describe findings (stage 4) and synthesize results (stage 5) from publications with a focus on 3 dimensions of patient-satisfaction measurement.26 The focus of this scoping review was on the method with which patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments was measured.

RESULTS

A total of 26 articles were retained for this review and charted analytically (Supplementary Table 1). The initial search identified 384 publications for screening. After assessing for duplicates and identifying other reasons studies met exclusion criteria, such as combination treatments, 255 publications were included for further analysis. Evaluation of abstract reviews led to the exclusion of 213 studies due to combination treatments, nonrandomized controlled methods, no measure or evaluation of patient satisfaction, and type of acupuncture treatments. A total of 42 full-text studies were reviewed for eligibility; 16 were excluded because they were not published in English, did not include or need EA/acupressure techniques, patient satisfaction was focused on the procedures versus on treatment, or the publications were review articles rather than original studies. No additional studies were included after review of the references in the articles.

Study Characteristics

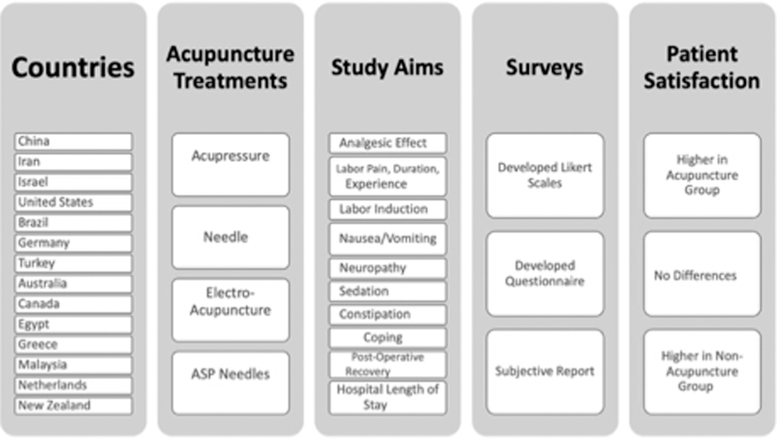

Twenty-six RCTs were conducted in varying settings, across multiple countries, including: China (n = 4); Iran (n = 4); Israel (n = 3); United States (n = 3); Brazil (n = 2); Germany (n = 2); Turkey (n = 2); Australia (n = 1); Canada (n = 1); Egypt (n = 1); Greece (n = 1); Malaysia (n = 1); The Netherlands (n = 1); and New Zealand (n = 1). See Figure 3. One of the studies was a multicenter trial conducted in China and Iran.30 Varying sample sizes were also noted and ranged from 12 to 450. More than half of the studies included blinding within the design (n = 14).7,9,10,12,13,15,16,19,22,24,25,31–33 Acupuncture treatment styles also varied with studies utilizing acupressure (n = 10)6,8–10,14,16,20,21,32,34 and needles (n = 9).12,13,18,19,25,30,31,33,35 The remaining studies included EA (n = 6)7,15,17,22–24 and Aiguille Semi-Permanente® needles (n = 1).11

FIG. 3.

Study characteristics (N = 26 studies). ASP, Aiguille Semi-Permanente® needles.

All 26 studies utilized different scales, indicating a lack of homogeneity among patient-satisfaction measures. Most of the studies developed their own patient-satisfaction tools in varying Likert formats (n = 18).6,7,9,11–16,19,21,22,24,25,30–32,35 One study developed a questionnaire related to applied methods specific to patient satisfaction with massage and acupressure treatments.8 Seven of the studies used validated measures that included: the Patient Satisfaction with Sedation Instrument (PSSI)17; the Clinical Satisfaction with Sedation Instrument (CSSI)17; a visual analogue scale (VAS)10; the Pharmaceutical Care Satisfaction Questionnaire (PCSQ)18; the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale (MCSRS)34; a verbal rating scale (VRS)33; and the Health-Related Quality of Life instrument (HRQoL).20 One study used a subjective report to ask if participants felt satisfied or dissatisfied with EA.23

Study Aims

Most of the studies evaluated analgesic effects of acupuncture interventions (n = 13).6,10–15,19,21,22,24,31,33 Three studies utilized acupressure as an intervention for labor pain and duration as well as for childbirth experience.8,9,34 Moreira de Sá and colleagues evaluated the effect of EA on labor induction.23 The remaining trials assessed acupuncture for relieving symptoms of nausea/vomiting (n = 2) as well as for addressing neuropathy (n = 1), therapeutic sedation (n = 2), constipation (n = 1), coping (n = 1), postoperative recovery (n = 1), and hospital length of stay (n = 1).7,16–18,20,25,30,32,35 Patient-satisfaction results were closely divided. Thirteen studies reported higher satisfaction levels in the acupuncture treatment groups7,9,10,12,13,15,20–23,30–33 and 14 studies reported no differences in satisfaction.8,14,16–19,11,21,24,25,34,35 Only 1 study reported higher satisfaction in the nontreatment group.6 Overall, the results of these studies showed acupuncture treatments to safe, with no reported adverse events.

The HMHSQ Conceptual Model

None of the studies discussed the use of a theory or conceptual framework for their methods or analyses. There was no consistent dimension present but at least one of the HMHSQ dimensions was included in all the studies (Table 1). An overwhelming majority (n = 17) of the studies assessed only 1 aspect of patient satisfaction with a focus on sub-dimensional, outcome criteria.6–14,15,16,20,21,30–33 The dimensional level was included in 3 of the satisfaction surveys.23–25 Five of the studies included a combination of dimensional and sub-dimensional measures.17,19,22,34,35 Only 1 study included all the HMHSQ dimensions to ensure a global patient-satisfaction measure; however, this measure was specific to pharmaceutical services.18

Table 1.

Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality Conceptual Framework

| HMHSQ elements | Sub-dimensional | Dimensional | Dimensional & sub-dimensional | Global |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies (N = 26) | n = 17 | n = 3 | n = 5 | n = 1 |

| Reference citations* | 6–16,20,21,30–33 | 23–25 | 17,19,22,34,35 | 18 |

Reference citations are in the text of the article.

HMHSQ, Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality.

Sub-Dimensional (Outcome)

Measurement of patient satisfaction concentrated on treatment outcomes associated with study aims, including symptom relief (n = 8).6,10,13,15,16,20,31,33 Seven of the studies assessed overall satisfaction with care.7,11,12,14,21,30,32 Similarly, 1 study assessed satisfaction related to entire labor experience with the addition of acupressure.9 Only 1 study measured satisfaction related to the acupuncture intervention (n = 1).8

Dimensional (Technical)

Three of the studies assessed patient satisfaction from the dimensional, technical lens of the HMHSQ conceptual framework.23–25 Ntritsou and colleagues assessed the analgesic effect of EA and developed a 6-point Likert scale specifically requesting feedback on the procedure technique.24 Similarly, Schaible and colleagues examined the effect of acupuncture on tolerance of a diagnostic procedure.25 The survey developed for that study asked participants to rate level of satisfaction with the overall procedural technique. With the same objective of assessing procedural technique, Moreria de Sá et al. conducted interviews with participants inquiring about satisfaction or dissatisfaction with EA to induce labor.23

Dimensional (Environment, Technical, Administrative, Interpersonal) and Sub-Dimensional (Atmosphere, Outcome/Expertise, Interaction/Relationship)

Five of the studies included a varying combination of HMHSQ dimensional and sub-dimensional elements (Table 2).17,19,22,34,35 One of these studies focused satisfaction measures on 1 dimensional element and 1 sub-dimensional element.35 Herman developed a 2-item questionnaire surrounding the environment and atmosphere in which participants received acupuncture in an inpatient setting. A total of 3 HMHSQ elements were included in a study by Teoh and colleagues with a focus on dimensional, interpersonal, and technical as well as sub-dimensional outcomes.22 This developed Likert (0–10 scale) survey assessed patient satisfaction with EA's effect on overall sedation and analgesia during a procedure as well as the procedure per se. Four HMHSQ elements were assessed by Eberl and colleagues, including dimensional, interpersonal, and technical aspects as well as sub-dimensional interaction, outcome, and expertise aspects.17 Two validated tools specific to patients undergoing outpatient endoscopy or colonscopy were utilized within a study including the PSSI and CSSI.36 Implementation of these tools enabled assessment and comparison of EA with respect to satisfaction with the overall procedure as well as with the endoscopist. Another study also utilized a validated tool that encompassed 6 of the HMHSQ elements, including 2 dimensional (interpersonal and technical) aspects as well as 4 sub-dimensional (interaction, relationship, outcome, and expertise) elements.34

Table 2.

Hierarchical Model of Health Service Quality Combination of Dimensional and Sub-Dimensional Elements

| Study 1st author, yr, & ref. # (n = 5) | Dimensional elements | Sub-dimensional elements |

|---|---|---|

| Eberl, 202017 | Interpersonal & technical | Interaction & outcome, expertise; |

| Herman, 201235 | Environment | Atmosphere |

| Samuels, 201219 | Administrative | Outcome |

| Mahmoudikohani, 201934 | Interpersonal & technical | Interaction, relationship & outcome; expertise |

| Teoh, 201822 | Interpersonal & technical | Outcome |

yr, year.

The MCSRS was used in a study to assess patient satisfaction with the overall experience of childbirth and attainment of expectations with the addition of acupressure.37

Global

Of the 26 studies included in this scoping review, only 1 utilized a validated survey that encompassed all of the HMHSQ conceptual elements, thus, providing a global measurement of patient satisfaction.18 Lai and colleagues applied the Malaysia Patient Satisfaction with Pharmaceutical Care Questionnaire (PSPCQ) to assess auricular acupuncture's effect in a methadone-maintenance treatment program.38 This validated and reliable tool consists of 20 items, with an emphasis on interaction with the patients and comprehensive care management. Participants were asked to provide a score of 1–5 on a Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction.

Limitations

This scoping review provided a large overview of measures utilized to assess patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments. The search was limited to RCTs published in English during the past 10 years. Inclusion of non-English language and all clinical trial resources may have provided additional studies for analysis, thus potentially excluding relevant studies.

DISCUSSION

The most-prominent finding of this scoping review was the lack of homogeneity and utilization of validated measures to assess patient satisfaction with acupuncture treatments. Use of validated and reliable patient-satisfaction tools appeared to capture more of the HMHSQ elements.17,34 Only 1 study provided a global patient-satisfaction assessment in line with the HMHSQ conceptual model.18 These findings demonstrated a need for uniformity, clinical specificity, and comprehensive assessment tools for measuring patients' experiences with acupuncture interventions. Future research should develop such tools. Qualitative research to study patient satisfaction with acupuncture would be essential for guiding survey-questionnaire development.

Potential survey topics specific to acupuncture and in line with the HMHSQ conceptual model would incorporate dimensional and sub-dimensional elements to ensure a global-satisfaction measure. Exemplar topics pertaining to interpersonal concepts would focus on the patients' interaction with acupuncturists, such as perception of friendliness and listening to patient needs. Technical, outcome, and expertise questions would include how the acupuncturist explained the treatment plan, addressed questions, and ensured patient understanding as well as overall therapeutic benefit. Administrative, timeliness, operations, and tangibles would address the ease with which the patient was able to schedule an appointment, obtain care within the dedicated time, and disposition experience. Finally, questions pertaining to the environment and atmosphere in which the treatment was provided would inquire about the facilities in which acupuncture was provided, such as cleanliness, comfort, wait time, and hours when services were provided.

CONCLUSIONS

This review provided a summary of the many acupuncture therapies available to patients with multiple medical conditions. The safety profile of acupuncture remains a constant theme in the literature and is supported by the current findings, as no adverse events were reported in any of the studies. As health care has evolved to ensure patient satisfaction and as acupuncture is integrated with current treatments, there is a need for validated and reliable measures to assess patient satisfaction. Development of these patient-satisfaction measures should be informed by theories/conceptual frameworks to ensure global assessments specific to acupuncture treatments. Furthermore, development of such measures would allow for uniform assessment of patient satisfaction pertaining to acupuncture interventions. Following development, high-quality RCTs and qualitative measures should be conducted to ensure validation and reliability of developed tools.

Supplementary Material

AUTHORs' CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Jackson was responsible for this study's conceptualization, methodology, project administration, and formal analysis, as well as writing the original draft, reviewing it, and editing it. Drs. Reneau and Hande participated in the investigation and formal analysis, as well as writing, reviewing, and editing the article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank medical librarian Rachel Lane Walden, MLIS, for her assistance in developing the search strategy and obtaining relevant publications for review.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No competing financial conflicts exist.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ng JHY, Luk BHK. Patient satisfaction: Concept analysis in the healthcare context. Patient Edu Couns. 2019;102(4):790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hayward D, de Riese W, de Riese C. Potential bias of patient payer category on CG-CAHPS scores and its impact on physician reimbursement. Urol Pract. 2021;8(2):183–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction: A systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gill L, White L. A critical review of patient satisfaction. Leadership in Health Serv. 2009;22:8–19. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Graham B. Defining and measuring patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg. 2016;41(9):929–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolvardi E, Zarmehri B, Bazzaz SMM, et al. Acupressure has not an analgesic effect in patients with renal colic: A randomized controlled trial. Universa Medicina. 2019;38(1):10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 7. El-Deeb AM, Ahmady MS. Effect of acupuncture on nausea and/or vomiting during and after cesarean section in comparison with ondansetron. J Anesth. 2011;25(5):698–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gönenç IM, Terzioğlu, F. Effects of massage and acupressure on relieving labor pain, reducing labor time, and increasing delivery satisfaction. J Nurs Res. 2020;28(1):e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hamidzadeh A, Shahpourian F, Orak RJ, et al. Effects of LI4 acupressure on labor pain in the first stage of labor. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2012;57(2):133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inangil D, Inangil G. The effect of acupressure (GB30) on intramuscular injection pain and satisfaction: Single-blind, randomised controlled study. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(7–8):1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jan AL, Aldridge ES, Visser EJ, et al. Battlefield Acupuncture added no benefit as an adjunct analgesic in emergency department for abdominal, low back or limb trauma pain. Emerg Med Australas. 2021;33:434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Miller E, Maimon Y, Rosenblatt Y, et al. Delayed effect of acupuncture treatment on OA of the knee: A blinded, randomized, controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:792975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oliveira KCP, Ricciardi JBDS, Grillo CM, et al. Acupuncture as a therapeutic resource for treatment of chronic pain in people with haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2020;26(6):e315–e322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mącznik AK, Schneiders AG, Athens J, et al. Does acupressure hit the mark? A three-arm randomized placebo-controlled trial of acupressure for pain and anxiety relief in athletes with acute musculoskeletal sports injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 2017;27(4):338–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen W-T, Chang FC, Chen Y-H, et al. An evaluation of electroacupuncture at the Weizhong acupoint (BL-40) as a means of relieving pain induced by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:592319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. White PF, Zhao M, Tang J, et al. Use of a disposable acupressure device as part of a multimodal antiemetic strategy for reducing postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2012;115(1):31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eberl S, Monteiro de Olivera N, Bourne D, et. al. Effect of electroacupuncture on sedation requirements during colonoscopy: A prospective placebo-controlled randomised trial. Acupunct Med. 2020;38(3):131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lua PL, Talib NS, Ismail Z. Methadone maintenance treatment versus methadone maintenance treatment plus auricular acupuncture: Impacts on patient satisfaction and coping mechanism. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(6):541–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Samuels N, Elstein D, Lebel E, et al. Acupuncture for symptoms of Gaucher disease. Complement Ther Med. 2012;20(3):131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suen KL. Complementary effects of auricular acupressure in relieving constipation symptoms and promoting disease-specific health-related quality of life: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2014;22(2):266–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vernon H, Borody C, Harris G, et. al. Randomized pragmatic clinical trial of chiropractic care for headaches with and without a self-acupressure pillow. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2015;38(9):637–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teoh AYB, Chong CCN, Leung WW, et. al. Electroacupuncture-reduced sedative and analgesic requirements for diagnostic EUS: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(2):476–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gribel GP, Coca-Velarde LG, Moreira de Sá RA. Electroacupuncture for cervical ripening prior to labor induction: A randomized clinical trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;283(6):1233–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ntritsou V, Mavrommatis C, Kostoglou C, et. al. Effect of perioperative electroacupuncture as an adjunctive therapy on postoperative analgesia with tramadol and ketamine in prostatectomy: A randomised sham-controlled single-blind trial. Acupunct Med. 2014;32(3):215–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schaible A, Schwan K, Bruckner T, et al. Acupuncture to improve tolerance of diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy in patients without systemic sedation: Results of a single-center, double-blinded, randomized controlled trial (DRKS00000164). Trials. 2016;17(1):350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dagger TS, Sweeney JC, Johnson LW. A hierarchical model of health service quality: Scale development and investigation of an integrated model. J Serv Res. 2007;10(2):123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Colquhoun HL, Levac D, O'Brien K, et al. Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(12):1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Levac D, Colquhoun HL, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Iravani S, Motlagh AHK, Razavi SZE, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture treatment on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A pilot, randomized, assessor-blinded, controlled trial. Pain Res Manage. 2020;2020:2504674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gilbey P, Bretler S, Avraham Y, et al. Acupuncture for post tonsillectomy pain in children: A randomized, controlled study. Paediatr Anaesth. 2015;25(6):603–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Noll E, Shodhan S, Romeiser JL, et al. Efficacy of acupressure on quality of recovery after surgery: Randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36(8):557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Splieth C. Acupuncture reduces pain and autonomic distress during injection of local anesthetic in children. Clin J Pain. 2016;32(1):82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mahmoudikohani F, Torkzahrani S, Saatchi K, et al. Effects of acupressure on the childbirth satisfaction and experience of birth: A randomized controlled trial. J Body Mov Ther. 2019;23(4):728–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Herman, PM. Acupuncture in the inpatient acute care setting: A pragmatic, randomized control [sic] trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012:2012:309762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vargo J, Howard K, Petrillo J, et al. Development and validation of the Patient and Clinician Sedation Satisfaction Index for colonoscopy and upper endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(2):156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mas-Pons R, Barona-Vilar C, Carreguí-Vilar S, et al. Women's satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: Validation of the Mackey Childbirth Satisfaction Rating Scale [in Spanish]. Gac Sanit. 2012;26(3):236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lai PSM, Chung WW, Toh LS, et al. Development and validation of an ambulatory care patient satisfaction questionnaire to assess pharmacy services in Malaysia. Int J Clin Pharm. 2018;40(5):1309–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.