Abstract

We report a novel method to inhibit epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling using custom morpholino antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) to drive expression of dominant negative mRNA isoforms of EGFR by ASO-induced exon skipping within the transmembrane (16) or tyrosine kinase domains (18 and 21). In vivo ASO formulations induced >95% exon skipping in several models of nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and were comparable in efficacy to erlotinib in reducing colony formation, cell viability, and migration in EGFR mutant NSCLC (PC9). However, unlike erlotinib, ASOs maintained their efficacy in both erlotinib-resistant subclones (PC9-GR) and wild-type overexpressing EGFR models (H292), in which erlotinib had no significant effect. The most dramatic ASO-induced phenotype resulted from targeting the EGFR kinase domain directly, which resulted in maximal inhibition of phosphorylation of EGFR, Akt, and Erk in both PC9 and PC9GR cells. Phosphoproteomic mass spectrometry confirmed highly congruent impacts of exon 16-, 18-, and 21-directed ASOs compared with erlotinib on PC9 genome-wide cell signaling. Furthermore, EGFR-directed ASOs had no impact in EGFR-independent NSCLC models, confirming an EGFR-specific therapeutic mechanism. Further exploration of synergy of ASOs with existing tyrosine kinase inhibitors may offer novel clinical models to improve EGFR-targeted therapies for both mutant and wild-type NSCLC patients.

Keywords: receptor tyrosine kinase, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, antisense oligonucleotides, epidermal growth factor receptor, exon skipping

Introduction

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are cell surface proteins that belong to a subclass of tyrosine kinases [1]; they regulate a range of fundamental cellular processes pertinent to cancer progression, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, and migration [2]. RTKs contain an extracellular domain with ligand binding sites, a transmembrane domain, and an intracellular kinase domain [3]. Under normal physiological conditions, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is activated by ligand-induced dimerization and autophosphorylation of the intracellular kinase domain. In the cancer setting, EGFR signaling can become constitutively activated through kinase domain point mutations or deletions (lung cancer), deletion of the extracellular domain (malignant glioma), or amplification and overexpression (breast, head and neck, and lung cancer) [4]. Current EGFR therapies include the use of extracellularly targeted monoclonal antibodies (mAb; cetuximab, panitumumab) and intracellularly targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; osimertinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, neratinib, vandetanib, and lapatinib) [5,6].

First-generation TKIs (erlotinib and gefitinib) were the first agents to provide a therapeutic benefit in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations, providing a year of progression-free survival with a 30-month overall survival [7]. However, virtually, all patients eventually develop treatment resistance [7,8]. Second-generation EGFR TKIs (afatinib and dacomitinib) provided the first effective treatment of patients with resistance due to T790M mutations, made further effective by the third-generation TKI, osimertinib [9]. Again, these patients ultimately develop resistance (eg, C797S mutation) [10] and fourth-generation TKIs are being tested to provide efficacy in this setting, which will undoubtedly promote yet a further cycle of resistance and need for novel therapies.

Furthermore, TKIs only demonstrate a therapeutic benefit for the 10% to 20% of NSCLC patients whose tumor harbors an EGFR mutation. Far more NSCLC tumors, ∼60%, exhibit overexpression of the wild-type EGFR gene (WT-OE) [11], for which no effective anti-EGFR therapy exists.

To address these existing shortcomings, we have investigated an alternative route of EGFR inhibition by the manipulation of alternative mRNA splicing, a critical and underappreciated phenomenon that contributes to cancer phenotypes [12]. We previously detected endogenously regulated EGFR-dominant negative isoforms [13], leading us to the hypothesis that EGFR inhibition can be regulated by alternative splicing. Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) have been previously designed to inhibit function by the manipulation of alternative splicing in Bcl-x, HER2, and EGFR mRNA [14–16], but have not been previously used to target EGFR pre mRNA. ASOs have now been clinically implemented as an effective and FDA-approved therapy used to treat spinal and Duchenne muscular dystrophy [17–19], demonstrating a potential therapeutic opportunity for ASO-based treatments.

In this study, we describe a novel approach to EGFR inhibition using custom phosphorodiamidate morpholino-based ASOs to (1) induce aberrant splicing of inhibitory isoforms of EGFR through a mechanism we refer to as splicing ablation kinase inhibition (SAKI), (2) demonstrate efficacy of SAKI-induced changes in oncogenic phenotype, EGFR signaling, and global phosphoproteomic expression analyses that mirror TKI treatment, and (3) demonstrate the efficacy of SAKI in both TKI-resistant EGFRmt NSCLC and EGFR WT-OE cell models.

Materials and Methods

Cells

For these studies, we used three NSCLC cell lines: human lung mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells (H292), the EGFRmt human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (PC-9), and the EGFRmt and gefitinib-resistant (T790M) human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (PC9-GR). These cells were provided by the Moffitt Lung Cancer Center of Excellence Cell Line Core.

Materials

ASOs/Morpholinos (Gene Tools, Philomath, OR); RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies Gibco, Grand Island, NY); fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies Gibco); trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) with phenol red (Life Technologies Gibco); Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Life Technologies Gibco); Platinum Hot-Start PCR Master Mix (Cat# 1300012; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription Kit (Cat# 4368813; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA); Macherey Nagel nucleospin RNA/Protein isolation kit (Cat# 740933; Bethlehem, PA); CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Cat# G7570; Promega, Madison, WI); 0.1% crystal violet; and SuperSignal West Pico plus chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL); Phospho-EGF Receptor (Tyr1068) (D7A5) XP Rabbit mAb (Cat# 2234; Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA); Phospho-Akt (Ser473) (D9E) XP Rabbit mAb (Cat# 9271; Cell Signaling); Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody (Cat# 9101; Cell Signaling); and EGF receptor (D38B1) XP Rabbit mAb (Cat# 4267; Cell Signaling).

Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction

Cells were seeded in six-well plates for ∼24 h and treated with ASOs and controls. Treated cells were trypsinized and cell pellets were made. RNA was isolated using the Macherey Nagel nucleospin RNA/Protein isolation kit (Cat# 740933), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. RNA was quantified using the Nanodrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher), and 1,000 ng of RNA was used to make cDNA, which was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription Kit (Cat# 4368813; Applied Biosystems) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with the Platinum hot start PCR master mix (Cat# 13000013; Invitrogen) using the respective primers. Resulted PCR products were run on agarose gel to visualize the bands.

Optimizing ASOs

Custom 25 bp morpholino ASOs were designed to drive the skipping of EGFR exons 16 (EGFRΔex16), 18 (EGFRΔex18), and 21 (EGFRΔex21), by targeting the 3′ and 5′ splice junction of each exon. ASO sequence optimization was performed through sequential four base pair shifts. Designed ASOs were used to treat cells for 48 h; after treatment, RNA was isolated. PCR was performed using the cDNA, and PCR products were separated on agarose gel. Gel band intensities were calculated, and the percentage of skipped product was analyzed. A combination of ASOs was also used for the optimization of treatments.

Cell Titer-Glo assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h. They were treated with EGFR-targeted ASOs and the control ASO for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. Cell viability was measured using the Cell Titer-Glo luminescent cell viability assay (Cat# G7570; Promega) as per the manufacturer's protocol.

Cell survival assay

A certain number of cells were seeded in 12-well plates for 24 h. They were treated with the control and targeted ASOs. After the wells had sufficient colonies, we removed the media and washed the wells with PBS. Cells were fixed with cold methanol for 10 min at −20°C. Methanol was removed, and 0.1% crystal violet was added to each well. The plate was shaken in a rocker for 30 min, and the wells were washed with water until the wash liquid became clear. Pictures of the wells were taken and analyzed. Crystal violet was extracted with methanol, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The readings were used to calculate cell viabilities.

Western blotting

Cell pellets were extracted after treatment and used for protein isolation. A Macherey Nagel nucleospin RNA/Protein isolation kit (Cat# 740933) was used to isolate proteins. Manufacturer's recommendations were followed, and isolated proteins were frozen. Proteins were loaded (30 μg) and run on SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). They were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, blocked using 5% milk, and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After washing the unbound and excess primary antibodies, secondary antibodies were added for 1 h at room temperature. Following the incubation and washings, proteins were detected using SuperSignal West Pico plus chemiluminescent substrate (Cat# 34580; Thermo Fisher) and the Odyssey Fc instrument. β-Actin was used as the loading control.

Scratch assay

Cells (H292, PC9, and PC9GR) were seeded in a 96-well ImageLock plate separately at a density that resulted in 100% confluency the following day. The next day, the wound maker was used to create wounds in all the wells. After wounding, the media were aspirated immediately and washed twice with 1 × PBS. After washing, EGFR ASOs and controls were added with culture media to the respective wells. Finally, plates were placed in the IncuCyte live-cell analysis system and allowed to warm to 37°C for 30 min before scanning. The plates were scanned every 3 h for 3 to 5 days, and data were analyzed.

Sample preparation for proteomics/phosphoproteomics

Cells were lysed in denaturing lysis buffer containing 8 M urea, 20 mM HEPES (pH 8), 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and 1 mM β-glycerophosphate. Protein pellets were resuspended for Bradford assay to estimate total protein content [Pierce™ Coomassie (Bradford) Protein Assay Kit, 23200; Thermo Scientific]. The proteins were reduced with 1/10 volume of 45 mM DTT for 20 min at 60°C and alkylated with 1/10 volume of 110 mM iodoacetamide for 15 min in the dark. Trypsin digestion was carried out at 37°C overnight, followed by additional trypsin the next morning for a 2-h incubation. Tryptic peptides were then acidified with 20% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for a final concentration of 1% TFA and desalted with C18 Sep-Pak cartridges as per the manufacturer's instructions (HyperSep C18 Cartridges, 60108-390; Thermo Scientific).

Tandem mass tag labeling

Lyophilized peptides (400 μg) from each sample were labeled with TMT10plex reagent (TMT10plex™ Isobaric Label Reagent Set, 90110; Thermo Scientific). The label incorporation was checked using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and spectral counting; 98% or greater label incorporation was achieved for each channel. The reaction of the 10 samples was then quenched, pooled, and lyophilized.

High pH reversed-phase peptide separation

Following lyophilization, the peptides were redissolved in 250 μL of aqueous 20 mM ammonium formate, pH 10.0 (bRPLC A solvent). The high pH reversed-phase separation was performed on an XBridge 4.6 mm ID × 100 mm in length column packed with BEH C18 resin, 3.5 μm particle size, and 130 Å pore size (Waters) at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The peptides were eluted as follows: 5% bRPLC solvent B for 10 min; 5% to 15% solvent B over 5 min; 15% to 40% solvent B over 47 min; 40% to 100% solvent B over 5 min; and held at 100% solvent B for 10 min, followed by re-equilibration at 1% solvent B.

Solvent A was composed of 5 mM ammonium formate in 2% acetonitrile at pH 10. Solvent B was 5 mM ammonium formate in 90% acetonitrile at pH 10. Three percent of the total separated peptides were concatenated into 24 fractions for protein expression and were dried in a vacuum centrifuge. The remaining 97% of peptides were concatenated into 12 fractions for phosphopeptide enrichment and were lyophilized.

Immobilized metal affinity chromatography enrichment

Fractionated peptides were redissolved in immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) loading buffer containing 85% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. The phosphopeptides in each fraction were enriched using IMAC resin (Cell Signaling Technology) on a KingFisher robot (Thermo Fisher). Briefly, the IMAC resin was washed once with loading buffer and the peptides were incubated with 130 μL of IMAC resin for 30 min at room temperature, with gentle agitation. After incubation, the IMAC resin was washed twice with loading buffer, followed by a single wash with wash buffer containing aqueous 80% acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. The phosphopeptides were eluted with elution buffer containing, 2.5% ammonia in aqueous 50% acetonitrile. The phosphopeptides were dried using vacuum centrifugation and then resuspended in 20 μL of LC loading solvent [2% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (FA)] for LC-MS/MS.

Liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

A nanoflow ultra-high performance liquid chromatograph and an electrospray benchtop orbitrap mass spectrometer (RSLC Q Exactive HF-X; Thermo, San Jose, CA) were used for tandem mass spectrometry peptide sequencing experiments. Peptides were first loaded onto a precolumn (100 μm ID × 2 cm in length packed with C18 reversed-phase resin, 5 μm particle size, and 100 Å pore size) and washed for 8 min with aqueous 2% acetonitrile containing 0.1% FA (solvent A).

The trapped peptides were eluted onto a C18, 75 μm ID × 25 cm, 2 μm, 100 Å analytical column (Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA) using a 120-min program at a flow rate of 300 nL/min of 5% solvent B (above) for 8 min; 5% to 38.5% solvent B over 90 min; and 50% to 90% solvent B over 7 min and held at 90% for 5 min, followed by 90% to 5% solvent B in 1 min, and re-equilibrated for 10 min. Solvent A was composed of 98% ddH2O and 2% acetonitrile containing 0.1% FA. Solvent B was 90% acetonitrile and 10% ddH2O containing 0.1% FA. Twenty tandem mass spectra were collected in a data-dependent manner following each survey scan. The resolution settings were 60,000 and 45,000 for MS1 and MS/MS, respectively. The isolation window was 0.8 Th, with a 0.2 offset.

Data analysis

MaxQuant (version 1.5.2.8) was used to quantify the tandem mass tag reporter ion intensities. Spectra were assigned and quantitated using MaxQuant [20]. Data were further normalized using IRON [21] (iron_generic—proteomics) against the median sample (findmedian—spreadsheet—pearson). Biological replicates were averaged, and log2 ratios were calculated between treatment and control averages. t-Tests were then calculated from the individual biological replicates. Rows were determined to be differentially expressed if the following criteria were met: row maps to a human protein, log2 ratio ≥ ∼0.585 (1.5-fold) and P value <0.05.

Scores for each two-group comparison were calculated as the geometric mean of the |log2 ratio| and −log10(P value) and were assigned the sign of the log2 ratio. Scores were then summed to generate a SumScore, with which to rank the upregulated and downregulated proteins. Pathway enrichment of differentially expressed proteins was performed against the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) [22,23] gene lists using a Fisher's exact test after first filtering to remove any row mapping to proteins from multiple genes.

Results

Optimization of in vitro ASOs in PC9 and PC9GR cell lines demonstrates ASO target sequence spatial relationship with splicing efficacy

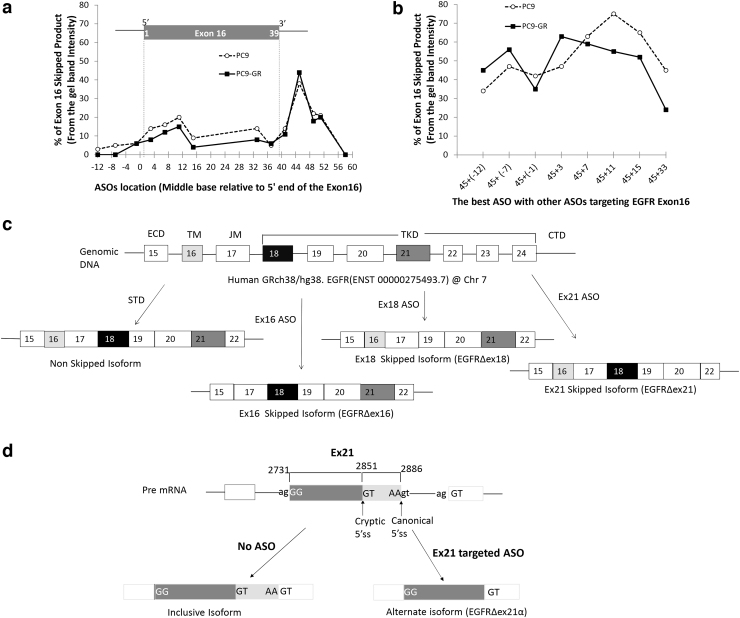

To investigate the impact of ASO target sequence on splice-switching efficacy, we used the “in vitro” formulation of ASOs, which refers to a specific chemical formulation of commercially available ASOs. These in vitro ASOs require the concomitant use of transfection agents and result in less effective splice switching, thereby providing a wide dynamic range in which we could investigate the impact of target sequence on ASO efficacy. In vitro ASOs placed within the 5′ splice site (to the right of exon 16) resulted in maximum exon exclusion (Fig. 1a, location 45).

FIG. 1.

Optimization of ASO target sequence and schematic diagram of human EGFR with its expected splice variants. To optimize exon 16 skipping, we systematically designed and tested in vitro ASOs centered on every fourth base pair near the 5′ and 3′ ends of exon 16. The x-axis shows the base pair location of the center of each ASO target relative to the start of exon 16. PC9 (dashed line) and PC9-GR (solid line) cells were exposed to 5 μM of EGFR ASOs for 48 h and quantified with respect to percent EGFR exon 16 skipped product (skipped/total) relative to the wild-type isoform by RT-PCR. We first examined (a) single ASOs, which revealed a distinct peak in efficacy for both cell lines centered on exon base pair 45 located with the 5′ splice site of intron 16 and a secondary peak within the 5′ exon centered on base pair 11. We then examined whether the ASO centered on base pair 45 could be combined with a second ASO to provide a synergistic effect (b). Synergy was detected using a second ASO when it targeted the 5′ end of the exon (nonoverlapping) and a decreased efficacy when the second ASO was located near the original ASO (base pair 33) thought to be capable of sterically competing with the first ASO. (c) ASO targeting of exons 16 and 18 resulted in mRNA expression of the expected isoforms. In contrast, ASO targeting of exon 21 resulted in the use of a cryptic 5′ splice site formed within exon 21 that results in persistent inclusion of the 5′ portion of exon 21 (d). ASO, antisense oligonucleotide; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction.

In addition, in vitro ASOs targeting the region spanning the 3′ upstream intron and 5′ edge of the exon also resulted in modest splice switching (Fig. 1a). To assess for a potential synergistic effect of ASOs, we assessed the splicing efficacy of the most effective ASO in combination with other ASOs. Overall splicing efficacy was increased when the 5′ splice site ASO was combined with other effective 3′ ASOs, resulting in up to 80% splice switching in the PC9/PC9GR cell lines (Fig. 1b). Splicing efficacy either did not improve or decreased when ASO targets overlapped any portion of the same sequence, suggesting evidence for steric inhibition when applying ASOs with overlapping or competing target sequences.

Dose-dependent exon skipping was observed in H292, PC9, and PC9-GR cells

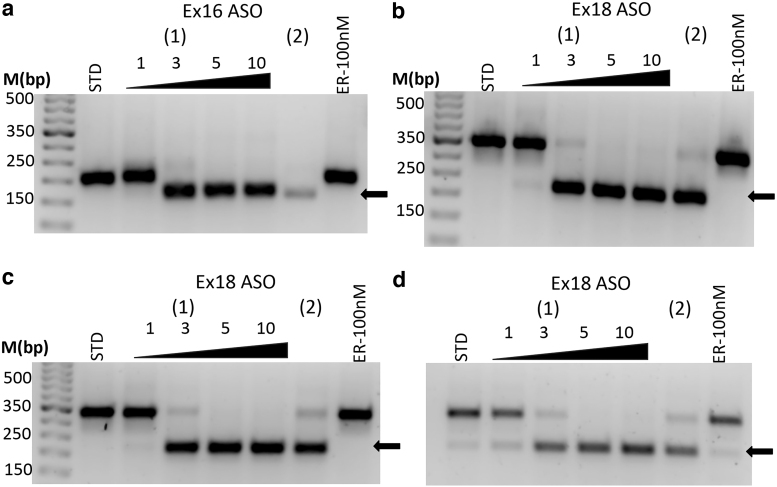

For subsequent investigations, we switched to the commercially available morpholino “in vivo” ASOs and found that the in vivo morpholino formulations provided dramatically increased, dose-dependent efficacy at comparable doses without the need for transfection agents. ASO administration resulted in dose-dependent exon skipping of exons 16 (EGFRΔex16/Fig. 1c) and 18 (EGFRΔex18/Fig. 1c), which resulted in complete exon skipping by 5 μM concentration in H292 cells (EGFR WT-OE, Fig. 2a, b). Similar results were observed with exon 18 in both PC9 (Fig. 2c) and PC9GR cells (Fig. 2d). Complete skipping of exon 16 in PC9 and PC9-GR cells was also observed at 5 μM (Supplementary Fig. S1).

FIG. 2.

In vivo ASOs induce dose-dependent complete skipping of targeted exons in multiple NSCLC cell lines. The in vivo ASO formulation showed significantly improved efficacy compared to the in vitro formulation (Fig. 1) and was able to induce complete targeted exon skipping in H292 cells of exon 16 (a) and exon 18 (b) and exon 18 in both PC9 (c) and PC9-GR (d). ASOs were used as 0, 1, 3, 5, and 10 μM concentrations for 48 h. (1) Represents the optimized ASO and (2) is a secondary ASO at 5 μM. Arrow (lower bands) represents the skipped product. No effect was observed with erlotinib (ER). NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung cancer.

In contrast, when we used human umbilical vascular endothelium cells (HUVEC) as control cell lines, we did not observe any skipping at mRNA levels (Supplementary Fig. S2a). The in vivo ASO formulations were used for all other experiments. Interestingly, ASOs targeting EGFR Ex21 did not form fully skipped isoform due to the use of a cryptic 5′ splice site (EGFRΔex21α; Supplementary Fig. S3 and Fig. 1d). Sequences of the novel mRNA isoforms were verified by Sanger DNA sequencing (GENEWIZ, South Plainfield, NJ).

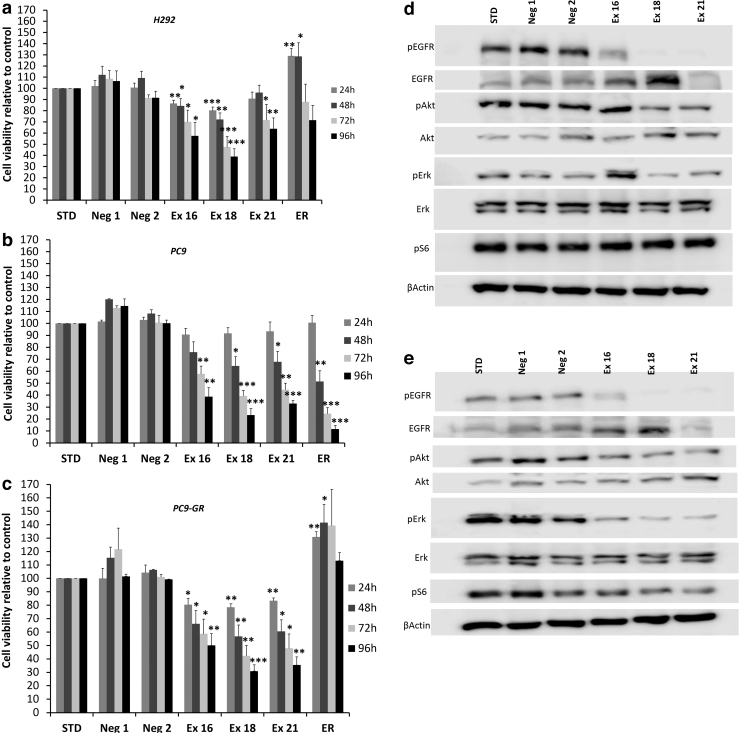

Cell growth was reduced in response to EGFR ASOs

Cell growth was reduced in response to ASOs as confirmed by cell viability, scratch, and colony-forming assays. Cell viability was significantly reduced with the induction of EGFRΔex16, EGFRΔex18, and the EGFRΔex21α isoforms. Cell viability decreased over time, with a maximum effect noted at 96 h for all three cell lines used (Fig. 3a–c). Interestingly, no significant effect on cell viability was observed in HUVEC control cell lines treated with EGFR ASOs (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

FIG. 3.

ASO-induced skipping of exons 16, 18, and 21 results in reduced in vitro cell viability and EGFR signaling inhibition in H292, PC9, and PC9-GR cells. Cell viability was assessed in (a) H292, (b) PC9, and (c) PC9-GR cell lines measured using Cell Titer Glo Assay (Promega) and revealed that ASO targeting of exon 18 resulted in the largest reduction in cell viability across all three cell lines, whereas erlotinib only reduced viability in PC9 cells. Western blot analysis of (d) PC9 cells and (e) PC9-GR cells revealed that ASOs directed to the tyrosine kinase domain (exons 18 and 21) resulted in more profound suppression of EGFR signaling than targeting the transmembrane domain (exon 16). Blots show results for phosphorylation of EGFR on tyrosine (Y) 1,068, Akt at serine (S) 473, Erk targets at threonine (T) 202/tyrosine (Y) 204, and S6 at serine (S) 235/236. Cells were treated with 5 μM concentrations of the indicated ASOs and 100 nM erlotinib (ER). Neg1 and Neg2 are custom negative controls, and STD refers to the company-provided standard negative control. All the treatments lasted 48 h. Asterisks indicate two-tailed t-test significance using thresholds of *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

A cell survival assay further confirmed the cell viability reduction in response to EGFR ASOs targeting exons 16, 18, and 21 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Decreased growth and migration were observed in response to ASOs as assessed by scratch assay, especially in PC9 and PC9 GR cells (Supplementary Fig. S5). Interestingly, induction of EGFRΔex18, and EGFRΔex21α isoforms resulted in the robust reduction in cell migration.

EGFR pathway signaling was reduced in response to EGFR ASOs

EGFR and its downstream targets were downregulated in response to EGFR ASOs (Fig. 3d, e). Phosphorylated EGFR (pEGFR), phosphorylated Akt (pAkt), and phosphoErk (pErk) levels were significantly reduced when ASO targeted exons 18 and 21 in PC9 cells, and to a far lesser extent for exon 16 (Fig. 3d). pAkt and pErk were significantly reduced in response to the induction of EGFRΔex16, EGFRΔex18, and EGFRΔex21α isoforms in PC9-GR cells. The induction of EGFRΔex18 isoform and cryptic splice site isoform resulting from partial skipping of exon 21 (EGFRΔex21α) both significantly decreased pEGFR levels in PC9-GR cells (Fig. 3e).

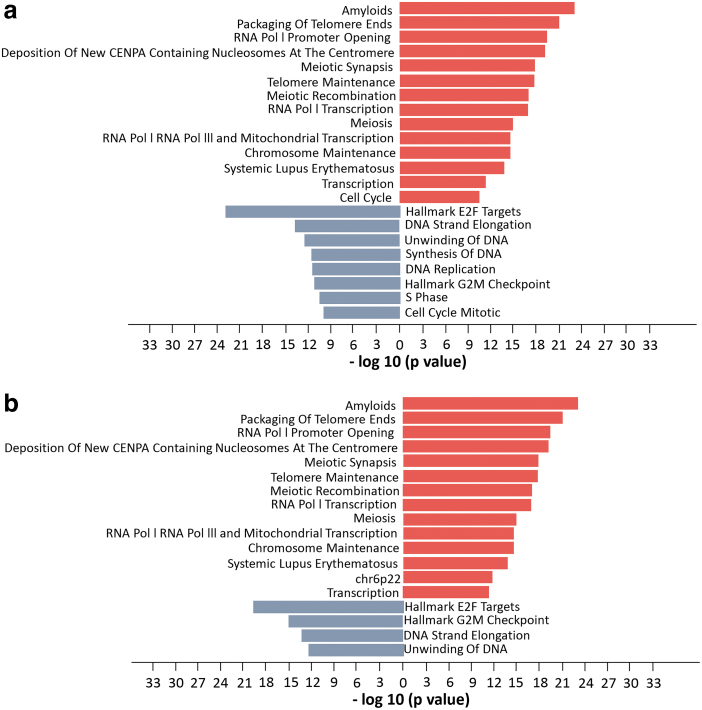

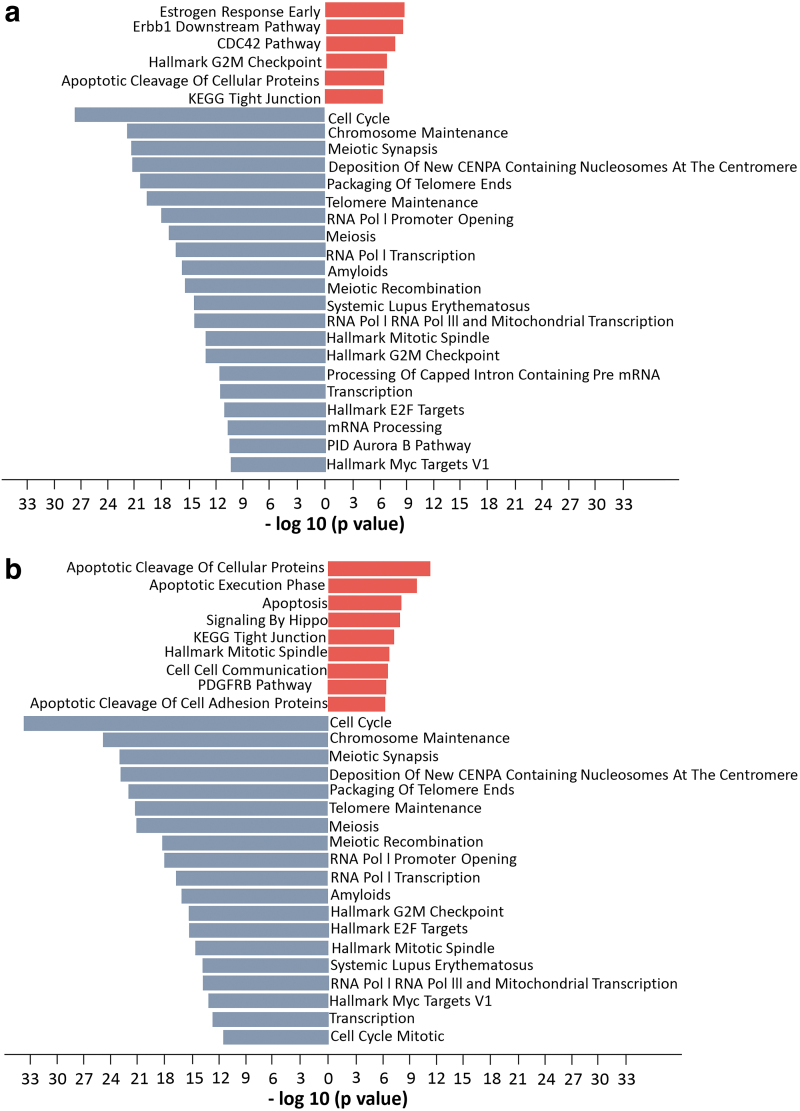

Expression proteomics and phosphoproteomics show that EGFR ASOs activate pathways related to cell proliferation

Pathway enrichment of differentially expressed proteins significantly (P value <10e−10) indicated ASO- and erlotinib-induced changes in cell cycle, mitosis, and G2/M checkpoint inhibition pathways. Proteomic analysis revealed that 13 out of 14 upregulated pathways and 4 out of 8 downregulated pathways overlapped in ASO-treated and erlotinib-treated PC9 cells, including cell growth-related pathways such as DNA replication, transcription, and the cell cycle (Fig. 4). Interestingly, phosphoproteomic pathway enrichment showed that several pathways related to cell growth were significantly downregulated in both ASO-treated and erlotinib-treated PC9 cells (Fig. 5), whereas most of these downregulated pathways were upregulated according to protein expression (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Pathway enrichment analysis of (a) combined proteomic analysis following EGFR ASO 16, 18, and 21 treatment compared with standard ASO control (STD) in PC9 cells. Comparable pathway enrichment was observed following (b) direct inhibition of EGFR using erlotinib treated relative to STD. Analysis was performed using the DE proteins. Figures represent pathways that enriched for increased (red) and decreased (blue) protein expression. All pathways have negative log10 P values >10. DE, differentially expressed.

FIG. 5.

Pathway enrichment analysis of (a) combined phosphoproteomic analysis following EGFR ASO 16, 18, and 21 treatment compared with standard ASO control (STD) in PC9 cells reveals inhibition of cell cycle and transcription and upregulation of apoptosis and EGFR (Erbb1) downstream pathways. Comparable pathway enrichment was observed following (b) direct inhibition of EGFR using erlotinib treated relative to STD. Analysis was performed using the DE proteins. Figures represent pathways that are formed only using upregulated DE proteins (red) and downregulated DE proteins (blue). All pathways were selected based on negative log10 P values >10.

In addition to these pathways, proteins involved in apoptosis and apoptotic cleavage pathways were hyperphosphorylated, further confirming the involvement of cell growth (Fig. 5). The EGFR downstream signaling pathway was significantly hypophosphorylated in cells treated with EGFR ASOs (Supplementary Fig. S6), confirming EGFR-specific inhibition by EGFR-targeted ASO treatment. Most phosphorylation sites on EGFR were hypophosphorylated following both ASO and erlotinib treatment; however, S1026 and S1081 were unique serine sites that were significantly hypophosphorylated in EGFR ASO-treated cells, while hyperphosphorylated in erlotinib-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Discussion

In this study, we describe a novel, splicing-based approach to inhibit EGFR (SAKI) and demonstrate its ability to inhibit in vitro oncogenic phenotypes and EGFR signaling in both TKI-resistant EGFRmt and EGFR WT-OE NSCLC cell models.

We successfully optimized custom ASO sequences to drive the exclusion of exons 16 (transmembrane domain), 18, and the 5′ half of 21 (tyrosine kinase domain) to generate new mRNA EGFR isoforms with predicted dominant negative activity (Fig. 1c). We were unable to directly detect expression of the skipped protein isoforms due to technical limitations because of the small size of excluded exons relative to the full-length protein. We also conducted mass spectrometry to investigate the expression of EGFR novel isoforms at the protein level, but were not able to identify peptide fragment mapping to the novel isoforms in post hoc proteomic analysis. This could be due to technical limitations of mass spectrometry when focusing on a small target region or could indicate a lack of protein-level expression of the proposed EGFR isoforms.

However, if the dominant negative EGFR isoforms are not expressed at the protein level, it is not immediately clear how ASOs would be able to otherwise drive EGFR-specific changes in signaling, while maintaining stable EGFR total protein expression, which would suggest that simple knockdown or nonsense-mediated degradation of EGFR protein is not the mechanism of ASO-mediated EGFR inhibition. Finally, we did not observe toxicity in HUVEC, suggesting specificity by tissue type, which would be necessary to confer a therapeutic benefit.

There are several preclinical studies to develop ASOs that target oncogenes, such as HER2 and Bcl-x, but there are no reported studies on the EGFR gene [14,15]. Our data indicate that EGFR signaling can be inhibited in NSCLC mtEGFR as well as WT-OE EGFR using EGFR-targeted morpholino-based ASOs. The application of ASOs in the treatment of genetic diseases dates back three decades. Although we focused on the use of ASOs to exclude targeted exons, ASOs are also capable of altering mRNA isoforms by selection of alternative 5′ transcription start sites, exon inclusion, and intron retention.

The first FDA-approved ASO drug was fomivirsen, a phosphorothioate-modified oligonucleotide, which was approved in 1998 for cytomegalovirus retinitis [24]. Mipomersen was the first FDA-approved systemically delivered ASO (in 2013) [25], and it was used to treat familial hypercholesterolemia by reducing the ApoB gene [26]. In 2016, two ASO drugs were approved by the FDA: eteplirsen, for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and nusinersen, for spinal muscular atrophy [19,27,28].

Nusinersen is a 2′-O-methoxyethyl phosphorothioate derivative ASO that acts by including exon 7 in the SMN2 gene, which enhances the SMA full-length protein [28,29]. Eteplirsen is the only FDA-approved morpholino-based oligomer, and it is able to induce skipping of exon 51 of the dystrophin gene. Morpholino-derived ASOs have added advantages, such as higher stability and easy delivery. The ASOs were produced by morpholino-based chemistry (Genetool), and they are designed to skip certain exons of EGFR during the splicing process. These morpholino oligos consist of methylenemorpholine rings and nonionic phosphorodiamidate linkages. This uncharged backbone makes them stable to nucleases [30,31]. Vivo-morpholinos used in our research are uniquely designed with octa-guanidine dendrimers for improved delivery without transfection reagents [30].

Further studies are warranted to explore the synergistic effect of ASOs and TKIs, for example, whether the addition of ASOs to TKIs is capable of preventing or delaying development of known pathways of TKI resistance. Although we focused our ASO-based approach on EGFR, other oncogenes could also be investigated, particularly those which are currently considered undruggable targets. Finally, in vivo studies and pharmacokinetic modeling will be required to further assess the potential for EGFR-targeted ASOs before its consideration in clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the Analytical Microscopy Core and the Proteomics & Metabolomics Core staff at Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute for their assistance. Moffitt core facilities are funded, in part, by the NCI through a Cancer Center Support Grant (P30-CA076292). We are also thankful to the Moffitt Scientific Editing Department for assistance in editing the article.

Author Disclosure Statement

T.R. holds a patent related to the therapeutic use of antisense oligonucleotides.

Financial Information

Timothy Robinson: DOD LCRP Career development grant.

Eric Welsh and Lancia N.F. Darville: Account: 5P30 CA076292-22 (PI: J. Cleveland Source: NIH/NCI Dates: February 18, 1998, to January 31, 2022 Title: H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute Support Grant).

Charles E. Chalfant: National Institutes of Health grants R01 DK126444 (to Charles E. Chalfant). This work was also supported by research grants from the Veteran's Administration [VA Merit Review I, BX001792 (Charles E. Chalfant) and a Senior Research Career Scientist Award, IK6BX004603 (Charles E. Chalfant)]. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T and Sudarsanam S. (2002). The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298:1912–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blume-Jensen P and Hunter T. (2001). Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature 411:355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hubbard SR. (1999). Structural analysis of receptor tyrosine kinases. Prog Biophys Mol Bio 71:343–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yarden Y and Pines G. (2012). The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nat Rev Cancer 12:553–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li SQ, Schmitz KR, Jeffrey PD, Wiltzius JJW, Kussie P and Ferguson KM. (2005). Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell 7:301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saadeh CE and Lee HS. (2007). Panitumumab: a fully human monoclonal antibody with activity in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Pharmacother 41:606–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gonzalez-Larriba JL, Lazaro-Quintela M, Cobo M, Domine M, Majem M and Garcia-Campelo R. (2017). Clinical management of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer patients after progression on previous epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors: the necessity of repeated molecular analysis. Transl Lung Cancer Res 6 (Suppl 1):S21–S34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yoshida T, Song L, Bai Y, Kinose F, Li J, Ohaegbulam KC, Munoz-Antonia T, Qu X, Eschrich S, et al. (2016). ZEB1 mediates acquired resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One 11:e0147344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Janne PA, Son J, Voccia I, Uttenreuther-Fischer M and Park. K (2015). Phase II study of BI1482694 in patients (pts) with T790M-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after treatment with an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (EGFR TKI). Ann Oncol 26:145. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Niederst MJ, Hu HC, Mulvey HE, Lockerman EL, Garcia AR, Piotrowska Z, Sequist LV and Engelman JA. (2015). The allelic context of the C797S mutation acquired upon treatment with third-generation EGFR inhibitors impacts sensitivity to subsequent treatment strategies. Clin Cancer Res 21:3924–3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Di Maria MV, Veve R, Bremnes RM, Baron AE, Zeng C and Franklin WA. (2003). Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. J Clin Oncol 21:3798–3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oltean S and Bates DO. (2014). Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer. Oncogene 33:5311–5318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robinson TJ, Dinan MA, Dewhirst M, Garcia-Blanco MA and Pearson. JL (2010) SplicerAV: a tool for mining microarray expression data for changes in RNA processing. BMC Bioinformatics 11:108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wan J, Sazani P and Kole R. (2009). Modification of HER2 pre-mRNA alternative splicing and its effects on breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer 124:772–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Taylor JK, Zhang QQ, Wyatt JR and Dean NM. (1999). Induction of endogenous Bcl-xS through the control of Bcl-x pre-mRNA splicing by antisense oligonucleotides. Nat Biotechnol 17:1097–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ciardiello F, Caputo R, Troiani T, Borriello G, Kandimalla ER, Agrawal S, Mendelsohn J, Bianco AR and Tortora G. (2001). Antisense oligonucleotides targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibit proliferation, induce apoptosis and cooperate with cytotoxic drugs in Human cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer 93:172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bauman J, Jearawiriyapaisarn N and Kole R. (2009). Therapeutic potential of splice-switching oligonucleotides. Oligonucleotides 19:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gao QQ, Wyatt E, Goldstein JA, LoPresti P, Castillo LM, Gazda A, Petrossian N, Earley JU, Hadhazy M, et al. (2015). Reengineering a transmembrane protein to treat muscular dystrophy using exon skipping. J Clin Invest 125:4186–4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Silver Spring, MD. grants accelerated approval to first targeted treatment for rare Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutation [news release] FDA. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-first-targeted-treatment-rare-duchenne-muscular-dystrophy-mutation Accessed December 13, 2019.

- 20. Tyanova S, Temu T and Cox J. (2016). The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc 11:2301–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Welsh EA, Eschrich SA, Berglund AE and Fenstermacher. DA (2013). Iterative rank-order normalization of gene expression microarray data. BMC Bioinformatics 14:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES and Mesirov JP. (2005). Geneset enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdottir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP and Tamayo P. (2015). The molecular Signatures database hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1:417–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roehr B. (1998). Fomivirsen approved for CMV retinitis. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 4:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Product label approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Association for Kynamro, no NDA. 203568. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/203568s000lbl.pdf Accessed May 10, 2013.

- 26. Disterer P, Al-Shawi R, Ellmerich S, Waddington SN, Owen JS, Simons JP and Khoo B. (2013). Exon skipping of hepatic APOB pre-mRNA with splice-switching oligonucleotides reduces LDL cholesterol in vivo. Mol Ther 21:602–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. approves first drug for spinal muscular atrophy FDA. www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm534611.htm?source=govdelivery&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery Accessed January 3, 2017.

- 28. Ottesen EW. (2017). ISS-N1 makes the First FDA-approved drug for spinal muscular atrophy. Transl Neurosci 8:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Singh RN and Singh NN. (2018). Mechanism of splicing regulation of spinal muscular atrophy genes. Adv Neurobiol 20:31–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morcos PA, Li Y and Jiang S. (2008). Vivo-Morpholinos: a non-peptide transporter delivers Morpholinos into a wide array of mouse tissues. Biotechniques 45:613–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moulton JD. (2017). Making a morpholino experiment work: controls, favoring specificity, improving efficacy, storage, and dose. Methods Mol Biol 1565:17–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.