Abstract

Background:

A history of unethical research and deficit-based paradigms have contributed to profound mistrust of research among Native Americans, serving as an important call to action. Lack of cultural safety in research with Native Americans limits integration of cultural and contextual knowledge that is valuable for understanding challenges and making progress toward sustainable change.

Aim:

To identify strategies for promoting cultural safety, accountability, and sustainability in research with Native American communities.

Method:

Using an integrative review approach, three distinct processes were carried out: (1) appraisal of peer-reviewed literature (Scopus, PubMed, and ProQuest), (2) review of grey literature (e.g. policy documents and guidelines), and (3) synthesis of recommendations for promoting cultural safety.

Results:

A total of 378 articles were screened for inclusion, with 55 peer-reviewed and grey literature articles extracted for full review. Recommendations from included articles were synthesised into strategies aligned with eight thematic areas for improving cultural safety in research with Native American communities.

Conclusions:

Research aiming to understand, respect, and acknowledge tribal sovereignty, address historical trauma, and endorse Indigenous methods is essential. Culturally appropriate, community-based and -engaged research collaborations with Native American communities can signal a reparative effort, re-establish trust, and inform pragmatic solutions. Rigorous research led by Native American people is critical to address common and complex health challenges faced by Native American communities.

Impact statement:

Respect and rigorous methods ensure cultural safety, accountability, and sustainability in research with Native Americans.

Keywords: Native American, culturally safe research, community-based research, best practices, ethics, integrative review

Introduction

Culturally safe research is a fundamental right, particularly among those with a history of alienation and marginalisation (Wilson & Neville, 2009). Cultural safety is a philosophical and conceptual approach that considers how social, political, economic, and historical contexts shape experiences and health outcomes (James et al., 2018). This approach is most needed in research, to reduce risks to individuals, families, and communities (Wilson & Neville, 2009). In research with Native Americans,1 often carried out by non-Native researchers, there has been little to no inclusion of cultural knowledge, methodologies, and priorities. This has contributed to distrust and disinterest in research that could reveal solutions to old and new problems. Within research, cultural safety acknowledges social determinants that underpin health inequities, critically examines power structures that undermine equity, and recognises that colonialism continues to influence Native American health (Curtis et al., 2019).

Despite well documented challenges, Native American communities2 have increasingly exercised their sovereignty, self-determination, and strength of traditional knowledge systems to support collective well-being (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Kading et al., 2019; Kirmayer et al., 2011). Historically, health research with Native Americans has centred settler colonial agendas (Warne & Bane Frizell, 2014). In effect, unethical research has contributed to collective distress, trauma, and mistrust from Native American communities (Pacheco et al., 2013). These experiences in the United States (US) mirror racism, trauma, and violence experienced by Indigenous populations globally. More recently, deficit-based research has further harmed and marginalised Native Americans by emphasising poorer health outcomes, reinforcing problematic stereotypes and generalisations (Brockie et al., 2013; Mashford-Pringle & Pavagadhi, 2020). There is a growing movement to recognise injuries caused by research, adopt just solutions, and rebuild relationships to remedy enduring health inequities. To this end, adoption of Indigenous methodologies is critical to ensure that culturally safe research can occur (McCleland, 2011).

Guiding principles and community-based participatory research (CBPR) methodologies have gained traction in countries with similar colonial histories and have informed development of standardised reporting criteria for research involving Indigenous peoples globally (Huria et al., 2019). However, robust guidance for research with Native Americans has not been integrated into the research enterprise (Claw et al., 2018; First Nations Information Governance Committee [FNIGC], 2020; Maiam nayri Wingara Indigenous Data Sovereignty Collective, 2018; Mashford-Pringle & Pavagadhi, 2020; Rautaki Ltd & Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, n.d.). Use of CBPR with Native Americans increased following the 2010 legal settlement with members of the Havasupai Tribe, whose rights were violated as participants in a 1990s study (Drabiak-Syed, 2010; Harmon, 2010). This timeline presents an opportunity to identify emerging recommendations in the literature and advance efforts to establish tailored guidance. We aimed to identify strategies that ground health research with Native American communities in a manner that promotes cultural safety, accountability, and sustainability.

Methods

Using an integrative review approach (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005), three distinct processes were implemented: (1) review of peer-reviewed literature, (2) review of grey literature, and (3) thematic synthesis of recommendations from the literature to identify strategies for engaging in rigorous, culturally safe research with Native Americans. Reference lists from articles selected for full-text review were also scanned to identify additional relevant literature. Our team, comprised of Native American scholars and non-Native allies, ensured representation of Native American perspectives in all steps of inquiry.

Literature identification

The search strategy for both peer-reviewed and grey literature (Table 1) was developed with a biomedical library scientist and in consultation authors (KH, NN) who have expertise in Native American research. Iterative searches of Scopus, PubMed, and ProQuest databases were performed. Indexed terms and key words were used to acquire peer-reviewed articles focused on best practices and lessons learned from conducting research with Native Americans. Search terms were tailored per database requirements with main subject headings: (1) American Indian/Native American/Alaska Native, (2) community-based participatory research/consumer driven community-based research, and (3) ethics/research ethics. For grey literature, a systematic approach was followed, which included iterative searches of the greylit.org database and targeted websites of relevant organisations, in consultation with senior authors (TB, DAH) who hold expertise in Native American research (Godin et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Peer-reviewed and grey literature search strategy.

| Peer-reviewed Literature |

| Terms applied in Scopus, PubMed, and ProQuest |

| American Natives[mesh] OR Indians, North American[mesh] OR “American Indian*” [tw] OR “Native American*” [tw] OR “American native*” [tw] |

| AND |

| Community-Based Participatory Research[mesh] OR |

| “Community Based Participatory Research” [tw] OR “Consumer Driven Community Based Research” [tw] |

| AND |

| Ethics, Research[mesh] OR “research ethics” [tw] |

| Grey Literature |

| Terms applied in greylit.org database |

| “Native American” OR “American Indian/Alaska Native” OR “Indigenous” OR “Indigenous” |

| Terms applied in targeted website searches |

| When a website search box was available, terms included “Native American” OR “American Indian/Alaska Native” OR “Indigenous” OR “Community-based participatory research” OR “Ethical research conduct.” Reviewers also looked at context across pages of a website, such as Resources or Research pages. |

[mesh] = Medical Subject Heading term.

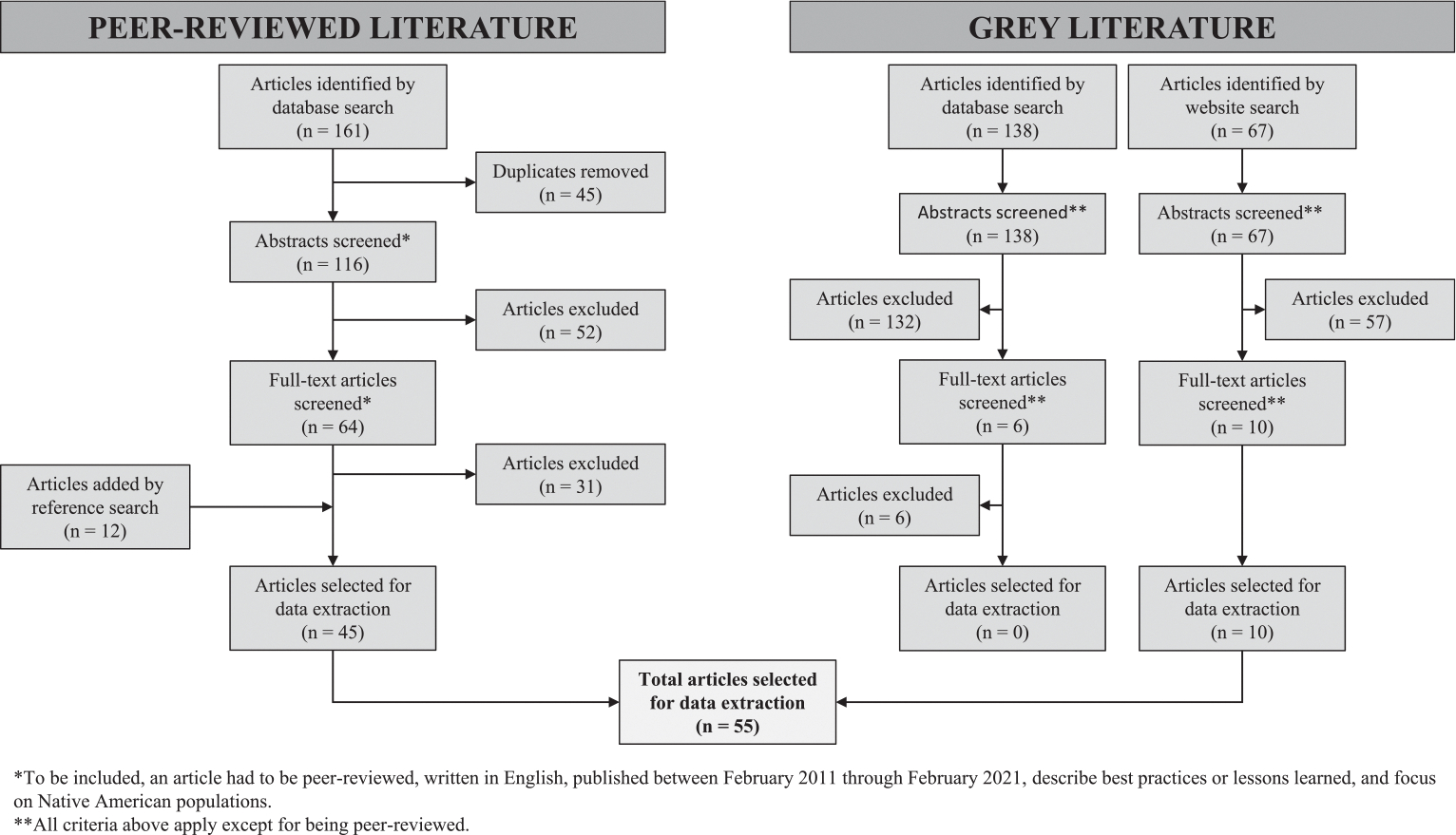

Literature screening

The process for screening identified articles was managed using Covidence and outlined using an adapted PRISMA diagram (Page et al., 2021) (Figure 1). Articles had to fit the following inclusion criteria: (1) peer-reviewed (applied to peer-reviewed literature search only), (2) written in English, (3) published between February 2011 and February 2021, (4) detailed description of best practices or lessons learned (i.e. elaborate on lessons from using a CBPR approach, not simply stating CBPR was used), and (5) focused on Native Americans, exclusively or in addition to other Indigenous populations. For a broad perspective, all article types were considered. Excluded articles primarily focused on describing an intervention or study findings without detailed methodological recommendations.

Figure 1.

Adapted PRISMA diagram for peer-reviewed and grey literature.

Results

Selected studies

The peer-reviewed literature search identified 161 articles. After deduplication, 116 titles and abstracts were screened (DW, LKK), resulting in 64 articles for full-text review. Four authors (DW, KH, LKK, AW) divided and reviewed, resulting in elimination of 31 articles. Native American authors (KH, DAH, TB) were consulted when there was uncertainty. The same four authors cross-checked reference lists of the remaining 33 articles to identify additional relevant literature, yielding 12 more peer-reviewed articles for inclusion. In total, 45 peer-reviewed articles were selected for data extraction.

A search of the greylit.org database yielded 138 results, which were screened by two authors (ED, KN) using established criteria. Full texts of six articles were reviewed and none met inclusion criteria. Websites of 24 organisations were searched using key terms (Table 1) to locate relevant literature (Godin et al., 2015). A total of 67 articles from 16 websites were independently reviewed by two authors (ED, KN) and a Native American author (NN) resolved discrepancies. Ten grey literature articles from six websites were included. In sum, 55 peer-reviewed and grey literature articles were selected for extraction.

Data extraction

Key elements were extracted from selected articles (Supplement). From the 45 peer-reviewed articles, data included: (1) first author’s last name and year published; (2) whether the article stated that the first and/or last author is Native American (signalling a primary writing or thought leadership role); (3) indication that a Native American community was engaged in the research; (4) type of article; and (5) best practices identified and/or lessons learned. Summaries were discussed (by DW, KH, LKK, AW) to achieve consensus, and a Native American author (KH) resolved differences. From the 10 grey literature articles, data included: (1) author, organisation, and year published; (2) article title and brief description of contents; (3) indication that a Native American community was engaged; (4) type of article; and (5) best practices identified and/or lessons learned. Summaries were discussed (by ED, KEN, NN), and a Native American author (NN) resolved differences.

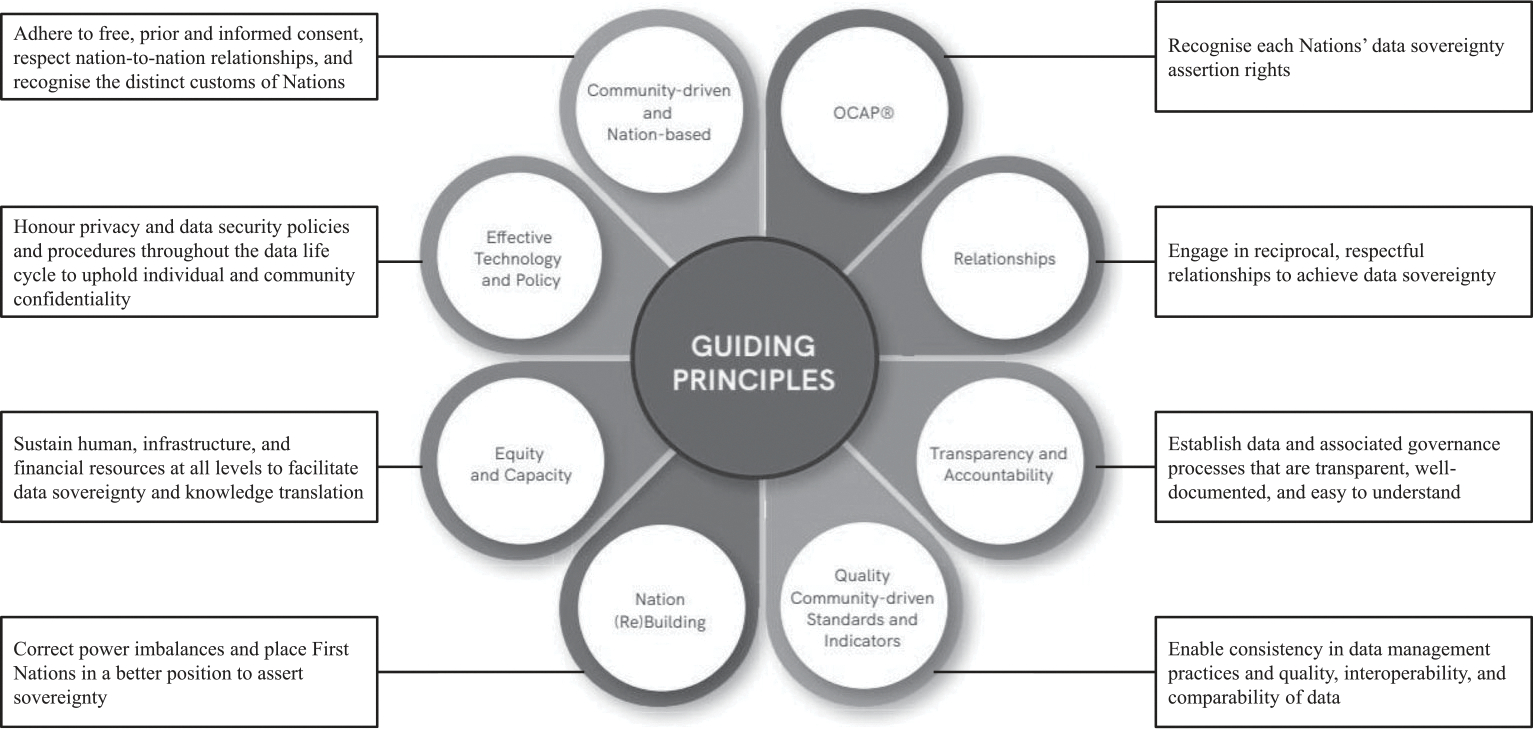

Synthesis of recommendations

FNIGC’s (2020) First Nations Data Governance Strategic Framework (Figure 2) served as an a priori organisational framework for thematic synthesis of best practices and lessons learned extracted from the literature (Supplement). This framework was chosen because it provides a foundation for ethical, respectful research engagement with sovereign Indigenous Nations and is aligned with elements included in the recently published CONSIDER checklist from Huria and colleagues (2019). Findings were thematically organised within the framework by three authors (DW, KH, LKK) for the peer-reviewed literature and two (ED, KEN) for the grey literature, respectively. KH and NN resolved any differences. Thematic synthesis of all recommendations (Table 2) is summarised below.

Figure 2.

Guiding principles from FNIGC’s First Nations data governance strategic framework.

Table 2.

Thematic analysis of review findings.

| BEST PRACTICES | CHALLENGES AND LESSONS LEARNEDS |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Community-driven and Nation-based | |

| Theme 1: Native American Led/Tribe Specific | |

| • Engage Native American researchers, especially in leadership roles • Ensure tribal oversight, engage a cultural broker or advisor • Value and leverage Indigenous knowledge – elders’, traditional, or spiritual/religious knowledge – more than scientific knowledge from Western paradigms • Include Native American language and community driven standards in projects |

• Time is necessary for engagement and development of trust |

| Theme 2: Tribal History | |

| • Understand unique tribal histories and political standings • Establish programmes grounded in an understanding of power and history and that build upon community strengths and cultural restoration |

• Lack of knowledge or appreciation for tribal histories, cultures, and diversity • Failure to understand local contextual issues |

| Theme 3: Community-based Participatory Research | |

| • Prioritise issues of concern to the community • Use community–academic partnerships with efforts informed by local community perspectives • Hire a local team to build community research capacity • Establish a tribal/community advisory board comprised of community members with appropriate experience and knowledge to guide research • Incorporate culturally appropriate methods, such as smudge, offering tobacco |

• Varying definitions of what constitutes community-based participatory research (CBPR) and varied methodological fidelity • CBPR gone wrong is rarely published nor the evolutionary steps of building relationships with communities • Continuing CBPR outside of funding windows is difficult |

| Ownership, Control, Access, and Possession (OCAP) | |

| Theme 1: Tribal Governance | |

| • Establish tribal resolutions for authorising research conducted within tribal jurisdictions and memoranda of agreement to address issues related to community collaboration • Engage tribal IRB* and ethical review processes • Establish institutional infrastructure, such as NIH’s Tribal Advisory Committee (TAC), to provide a venue for exchange of information between tribes and non-tribal institutions engaged in research with Native American communities |

• Researchers try to avoid tribal government review processes by conducting research with urban Native American communities • Limited or absent sharing of research updates and/or reporting of findings to community |

| Theme 2: Data Sovereignty | |

| • Establish data control and ownership agreements directed by tribal and community leaders • Understand that sovereign, federally recognised tribes have the right to decide when, if, and how to share data • Develop and implement plans for adherence to ethical guidelines between project partners in data ownership, management, and protection • Disseminate findings to community in accessible formats (e.g. newsletters with updates, publications using appropriate language) |

• The ethical principle of respect must recognise tribal sovereignty and tribes’ inherent right to govern research that takes place on their lands, including decision-making related to data ownership and use, as well as dissemination (e.g. review of publications) • The ethical principle of justice requires that sample selection must consider distributive justice and ensure that Native American communities are neither excluded from nor exploited in research |

| Theme 3: Secondary Data | |

| • Acknowledge that human subjects review may be necessary for secondary data analysis • Include a statement in consent forms about future and/or additional use of data, if that is part of the plan |

• Any re-analysis of data may compromise trust, standards of confidentiality, and data quality established in initial data collection efforts |

| Relationships | |

| Theme 1: Trust vs. Mistrust | |

| • Prioritise building and maintaining trust • Build trusting relationships that rely on frameworks of resilience and positive change rather than deficits • Use a CBPR approach to aid in developing trust through equitable distribution of all aspects of research and shared decision-making |

• Distrust of researchers and western medical model • Helicopter research (i.e. researchers collect data, then have limited to no involvement with the community as data are analysed and disseminated) creates distrust • History of tribes being misrepresented by researchers and grant writers • Tendency to pathologise Native American individuals and communities |

| Theme 2: Authentic Partnerships | |

| • Prioritise and foster collaboration, establish shared goals, respect cultural and local knowledge, and privilege community needs through genuine partnerships • Create opportunities for partners to learn from each other; well-crafted collaborative practice results in positive outcomes for both parties • Decolonise research to instil a balance between Indigenous and Western frameworks and methods |

• Previous negative experiences, in which results were used to support legal claims that did not benefit tribes, undermine partnership • Potential stigmatisation through the discovery of “negative” findings |

| Transparency and Accountability | |

| Theme 1: Confidentiality | |

| • Establish confidentiality agreements with tribes, at their request and guidance, if needed • Communicate research engagement practices • Engage community members or leaders to inform decisions about using self-identified tribal affiliation or tribal enrolment as an inclusion criterion for research participants |

• Ensuring confidentiality in small communities when community members are employed in research can be challenging, and considering a risk assessment matrix may be useful • Traditional methods of reporting qualitative research, such as combining data into themes and removing a participant’s name, may be perceived as disrespectful to the knowledge and experiences contributed to the research by elder study participants |

| Theme 2: Consent | |

| • Establish community consent in the form of memorandum of understanding/agreement (MOU/MOA) • Have a tribal advisory board review research material, and engage a tribal IRB to conduct human subjects review |

• Difficult to ascertain appropriate mechanisms for establishing community approval outside of tribal jurisdictions • Complexity and unique nature of consent regarding the jurisdiction of Native American communities when members/citizens live outside of tribal lands (e.g. in a proximal urban setting) • History of ethical violations undermines the principle of informed consent |

| Theme 3: Ethical Review and Monitoring Processes | |

| • Engage in ethical reflective practice as researchers • Respect tribal leaders’ dual roles of protecting people from research harms and advancing health research • Develop plans for adherence to ethical guidelines between project partners in data ownership, management, and protection • Uphold bioethics principles important to Native American research, including respect tribal sovereignty, promote transparency, hear community priorities, learn from each other, and take collective action |

• Many communities do not have the resources to create and sustain an ethical review process • History of ethical violations including forced sterilisation and misuse of tissue samples for research that goes against the wishes and belief systems of tribes |

| Quality Community-driven Standards and Indicators | |

| Theme 1: Indigenous vs. Western Methodologies | |

| • Promote understanding of Indigenous methodologies and primacy of Indigenous knowledge and worldviews • Use Indigenous methods alone or in conjunction with appropriate Western methods • Address health from a positive ecological perspective • Incorporate traditional cultural practices into prevention and health promotion strategies • Engage community members in data analysis and interpretation • Promote an asset-based framework |

• Prioritising Western models over Indigenous models • Culturally adapted interventions are generally described and understood through Western theoretical systems potentiating colonial ideals • Promotion of evidence-based interventions might be perceived as a colonising behaviour in instances where the interventions were developed for and tested with majority populations • Publication outlets and available measures tend toward pathology, reductionism, and deficit models rather than the resiliency-framed, holistic, and spirituality models favoured by communities |

| Theme 2: Planning | |

| • Plan with the community and include plans for an extended timeline and for potential leadership changes in the community • Proactively budget time and resources for measurement development when planning research • Recognise that many communities have limited resources and competing priorities; as a result, researchers may encounter delays in implementation of projects • Prepare for data sharing/use discussions at the outset of the project in collaboration with community partners |

• The length of time to complete research, particularly randomised controlled trials, can be disheartening to communities, especially considering urgent needs • Time demands on community members must be considered • Some common validated measures fail to capture important constructs in ways that are reliable and valid in Native American cultural contexts; however, highly tailored novel measures may introduce unknown errors of reliability, dimensionality, and other psychometric indices • Measures validated in Native American communities, as well as community-level measures that consider the unique cultural and socioecological contexts of tribal settings and use appropriate Native American theories to guide their development, are lacking |

| Nation (Re)Building | |

| Theme 1: Tribal Sovereignty | |

| • Recognise tribal sovereignty and adhere to tribal research oversight processes, including tribal resolutions, tribal research oversight committees, and the development of tribal research codes • Appreciate the role of tribal IRBs, as research oversight is a right of tribes as sovereign nations, and they are necessary due to federal and tribal differences in how human subjects research is defined • Protect community knowledge, culture, and self-governance |

• High-quality Native American data are limited, in part because Native populations are small and rarely represented in national epidemiological surveys, which limits tribal leaders’ ability to make informed decisions on behalf of their communities • Gaps in understanding of tribal policies and the policy-making processes necessary for research partnerships and the development of multilevel policy interventions to facilitate them • The federal definition of research in the US fails to protect tribal sovereignty when informed consents are not obtained in ethnographic research involving interviews with tribal members |

| Theme 2: Tribal Research Infrastructure | |

| • Build tribal research infrastructure by hiring and training a local team • Consider that research led by Native American researchers may be a more culturally appropriate approach to the design and execution of research involving Native Americans • Repair research relationships that have been upset or damaged • Prioritise dissemination of progress reports and findings to research participants and community |

• Absence of processes that enable tribal governments to express concerns about research related harms • Funding models often do not consider the additional time required to build relationships and respectfully start a project • Infrastructure and capacity are not universally distributed across communities |

| Equity and Capacity | |

| Theme 1: Capacity | |

| • Increase the number of Native American researchers with adequate funding and infrastructure • Support capacity building within communities • Prioritise increasing research capacity as an outcome of the research process • Value the expertise of community members in the cultural and political context relevant to data collected in their communities |

• Long-term sustainability and maintaining community buy-in can be challenging due to lack of resources • Tribal employee retention can be an issue • Competing demands on time and resources can result in research not being a priority |

| Theme 2: Academic Institutions and Funding Agencies | |

| • Offer training to academic researchers on how to work with Native American communities • Provide access to funding and sustainable methods of engagement • Reconceptualise intervention research time frames beyond the typical three-to-five-year grant funding cycle to an enhanced understanding of how change in complex systems occurs over a time span of decades, not years • Account for how people locally define and understand their own context and the nature of outside researchers before intervention • Create a project registration database for research that involves collaboration with Native American communities to support the use of CBPR • Revise tenure processes in universities to recognise CBPR |

• Federal regulations require review by an accredited IRB; however, when a Native American community does not have its own accredited IRB, the default IRB of record (often from the researcher’s institution) may not have the cultural or contextual knowledge to ensure that the community’s needs are sufficiently prioritised • Grant administration processes that require academic institutions to sponsor or partner undermine the ability of tribal nations and organisations to carry out research programmes • Research with tribal communities takes a long time and can slow career progress for academics due to the structure of tenure evaluations • Grant requirements are not aligned with the context and needs of Native American communities (e.g. strengths-based, timelines) |

| Effective Technology and Policy | |

| Theme 1: Data Management | |

| • Train community members to manage data • Develop an agreement, directed by the tribe(s) or Native American community(is), for data use and/or sharing, even when the data are managed by another entity, to afford legal protections against the potential risk of a data breach or misuse of data |

• Native Americans are often not represented or misrepresented in national epidemiological surveys |

| Theme 2: Institutional Review and Belmont Principles * | |

| • Implement plans for adherence to ethical guidelines between project partners in data ownership, management, and protection • Include modules on group harms to tribes and on conflict of interest when training researchers • Understand that tribal sovereignty means tribes can establish additional research protections, and this is acknowledged in the Common Rule* |

• Federal regulations that govern human subjects research protect individuals from research harm but do not adequately specify protections for community level harms • Available human subjects training modules fail to resonate with community members due to use of jargon, lack of cultural and contextual relevance, and absence of discussion about community risks and benefits • Absence of research ethics trainings tailored to needs of Native Americans can be a barrier to research participation • The principle of beneficence necessitates consideration of benefits and harms to Native American communities participating in research |

Key terms and acronyms: Belmont Principles = foundational ethical principles for research in the US, IRB = Institutional Review Board, Common Rule = common federal research regulations in the US.

Community-driven and nation-based

A community-driven and nation-based approach prioritises and values local perspectives and expertise, tribal histories, and sovereignty and jurisdictions of tribal nations. This involves decolonising research practices and blending Indigenous and Western methods within a CBPR framework to enhance trust (Engage for Equity Research Team, 2017; Jernigan et al., 2015; Rasmus et al., 2019; Simonds & Christopher, 2013; Stanton, 2014). Appropriate solutions are more likely identified when community is involved (Julian et al., 2017; Wendt et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2014). In short, outside researchers must avoid “solving” externally identified problems with externally identified solutions. Responding to a community-identified issue starts with formative research and a systems-thinking, local approach.

Ownership, control, access, and possession

Anchored in sovereignty and self-determination, the principles of ownership, control, access, and possession (OCAP®) (FNIGC, 2020) reinforce tribes as rightful owners of their data, with unmitigated access and control of which data will be collected and where it will be stored (Around Him et al., 2019; Chadwick et al., 2014; CRCAIH, 2019; Crump et al., 2020; Gachupin, 2019c; Harding et al., 2012; Hardy et al., 2016; Johansson et al., 2015). Bolstering OCAP fosters ethical relationships and supports Indigenous data sovereignty, or the “right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership, and application of data, information, and knowledge about its peoples, lands, and resources” (Carroll et al., 2017).

Historical research data breaches and misuse have led to widespread mistrust of the research enterprise and are due, in part, to a lack of understanding that tribal sovereignty, or the understanding that federally recognised tribes have the right to govern themselves and have jurisdiction over their lands and members, also establishes tribes as rightful owners of their data (Hardy et al., 2016). Data use and/or sharing agreements directed by tribal representatives are important (James et al., 2014). Such agreements typically encompass the lifecycle of the research process from relationship building to dissemination, with data storage governed and regulated by tribal authority (Hardy et al., 2016; Pacheco et al., 2013). Agreements should include development of tribal resolutions and memoranda of agreement for research conducted within tribal jurisdictions between tribal entities and research institutions (Goins et al., 2011). These agreements establish parameters of accountability between partners to ensure adherence to ethical guidelines which are grounded in tribal data ownership, management, and protection (Crump et al., 2020; Hardy et al., 2016). Accordingly, human subjects’ approval through a tribal Institutional Review Board (IRB) or other authorised community entity is also imperative (Pacheco et al., 2013). Additional approvals, often by tribal IRBs, of grant submissions, manuscripts, and changes in research ensure tribal oversight and help maintain integrity (Around Him et al., 2019; Morton et al., 2013).

Relationships

Research with Native Americans requires building in adequate time to develop respectful and meaningful relationships with community members and key stakeholders, which creates cultural safety and trust (Angal et al., 2016; Brockie et al., 2017; Brockie et al., 2019; Elliott et al., 2016; Hicks et al., 2012; Hoeft et al., 2014; Rasmus et al., 2019; Ravenscroft et al., 2015). CBPR methodologies are commonly recommended, given the focus on authentic relationship building. The formative phase encompasses 6–12 months to establish a tribal advisory board, have frequent dialogue regarding data collection methods, and develop research tools (Blacksher et al., 2016; Brockie et al., 2017; Gachupin, 2019a; Gachupin et al., 2019; Jernigan et al., 2020; Julian et al., 2017; Morales et al., 2016; Pacheco et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2019; Walters et al., 2019). Brockie et al. (2019) articulated the relationship building process via a conceptual model that contributes to authentic partnerships.

Authentic partnerships with Native Americans are achieved when research stems from community needs and involves the community in all aspects (Jernigan et al., 2015; Rasmus et al., 2019; Simonds & Christopher, 2013; Stanton, 2014). Respecting cultural and local knowledge and understanding tribal etiquette are important components in this process (Brockie et al., 2017; Crump et al., 2020; Fleischhacker et al., 2011; Julian et al., 2017; Jumper-Reeves et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2011). Providing a cultural healing response aligned with community values is particularly important when studying sensitive topics and can strengthen relationships (Engage for Equity Research Team, 2017; Gachupin, 2019a). Clear communication with tribal partners about timelines, logistics for collaboration, resources, and plans for long term sustainability is vital to ensure authentic partnership (Allen & Mohatt, 2014; Chadwick et al., 2014; Christopher et al., 2011; Garrison et al., 2019; Jumper-Reeves et al., 2014; Parker et al., 2019; Skewes et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2019; Wendt et al., 2019).

Transparency and accountability

An open, honest partnership begins at the onset of a research project with thoughtful development of plans to prioritise ethical reflective practice and adherence to bioethical principles important to Native Americans. Team members should undergo training on tribal sovereignty, data ownership, and historical harms within Native American research (Gachupin, 2019c; Jetter et al., 2015; National Institutes of Health Tribal Health Research Office [NIHTHRO], 2017; Pearson et al., 2019; Parker et al., 2019). Training should also include the complex and unique nature of consent processes based on tribal jurisdictions (Garrison & Cho, 2013; Harding et al., 2012). Additionally, researchers have an obligation to obtain confidentiality agreements and facilitate understanding for communities as needed (NIHTHRO, 2017). These agreements may be included in a tribal resolution and/or obtained through an NIH Certificate of Confidentiality. Overall, expectations should be discussed early and often to promote transparency and accountability.

Quality community-driven standards and indicators

Collaborating with the community to develop research plans facilitates incorporation of community values and definitions of success (Brockie et al., 2019; Garrison et al., 2019; Goins et al., 2011; Julian et al., 2017; Pacheco et al., 2013; Pearson et al., 2014). Guiding principles help articulate values, facilitate behaviours, and increase research capacity. They also promote use of asset-based frameworks, moving away from deficit-based approaches common in research. Additionally, they ensure stakeholders have the same objectives from the beginning and should be re-visited in later stages of the research project (Angal et al., 2016; Claw et al., 2018; Wilkinson et al., 2016).

Nation (re)building

Engaging tribes in research must involve respect for tribal sovereignty and recognition that health outcomes and infrastructure vary across tribes. Therefore, research should promote Native American led initiatives (Blanchard et al., 2017; Gachupin, 2019b; Garrison et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2011) and work to support nation (re)building as a culturally safe approach to account for those differences (Claw et al., 2018; Johansson et al., 2015). Nation (re) building should include processes to enhance tribal research infrastructure and develop research budgets informed by tribes/communities (Elliott et al., 2016). Inclusive authorship on scientific publications also strengthen research capacity and infrastructure, as does the provision of opportunities for community members to obtain advanced degrees and take on the role of investigator (Ravenscroft et al., 2015). Additional activities may involve hiring and training local people, engaging tribal leaders in the research process beyond authorisation, and disseminating research findings to communities in an understandable manner (Around Him et al., 2019; Brockie et al., 2017; 2019; Elliott et al., 2016; Gachupin, 2019a; Goins et al., 2011; Morales et al., 2016; Morton et al., 2013; Walters et al., 2019). Further, adhering to tribal regulatory guidelines to monitor all processes, often through tribal IRBs, honours tribes as sovereign nations and helps correct power imbalances (NCAI Policy Research Center & MSU Center for Native Health Partnerships, 2012).

Equity and capacity

Leveraging opportunities for training and capacity building bolsters investment in the success of Native Americans, making this an essential component of the research process (Chadwick et al., 2014; Christopher et al., 2011; Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health [CRCAIH], 2019; Elliott et al., 2016; Hicks et al., 2012). Mentoring and training Native Americans to lead successful research programmes and bolstering training in Indigenous methodologies must be a priority to foster culturally safe research. Relatedly, community members with cultural expertise are often overlooked despite capacity to make invaluable contributions to research, further justifying the use of an asset-based approach.

Training and capacity building efforts cannot be strengthened or sustained without specific funding mechanisms. Funding agencies must account for the additional time needed to conduct high-quality CBPR (NIHTHRO, 2017). Academic institutions must follow suit and take these circumstances into consideration for tenure and promotion requirements (Yuan et al., 2014). Taken together, these practices can help promote research that builds trust and benefits Native American communities (Angal & Andalcio, 2015; Kelley et al., 2013; Wendt et al., 2019).

Effective technology and policy

Training community members to manage data is an expression of tribal sovereignty. When training Native and non-Native researchers, the adaptation of human subjects modules to focus on cultural restoration, community strengths, and acknowledgement of history and to include lessons on group harms ensures that researchers have the confidence, trust, and ability to assess benefits and risks of research with Native Americans (Pearson et al., 2014). Additionally, recent revisions to the Common Rule acknowledge that tribes have the right to stipulate additional research protections (Hull & Wilson, 2017).

Discussion

Culturally safe research is imperative, especially for populations who have experienced research harms. Moreover, such an approach is critical in undertaking essential research to improve health outcomes. Native Americans have faced longstanding differences in health outcomes and been subject to research primarily led by non-Native researchers. Recommendations for promotion of cultural safety in research have emerged for Native American communities, those in nursing and midwifery, and the broader research enterprise (Table 3). This integrative review shows that the most recent literature has focused on establishing relationships with tribal communities. However, there is less literature on how to sustain engagement throughout and beyond a research project. Such an approach is important to address embedded inequities in resource allocation and power relationships. Establishing guidelines for cultural safety in research with Native Americans will contribute to restoring trust, improving engagement, and promoting research led by Native American investigators. Ensuring planning for cultural safety starts long before data collection, with the preparation/planning phase and, importantly, in the training of researchers. Long-term strategies for engagement should be proactively developed rather than an afterthought.

Table 3.

Recommendations for supporting cultural safety in research with Native American communities.

| Native American Communities |

| • Increase research literacy and capacity among community members |

| • Foster community/tribal governance procedures to promote cultural safety in research |

| • Promote collaboration among Native American communities locally and nationally, and with Indigenous communities internationally |

| Nursing and Midwifery |

| • Appreciate antecedent factors that contribute to structural racism, marginalisation, death, and suffering, and how these factors intersect in research with Native American communities |

| • Promote and support Native American health care professionals and community health workers who are of the community in research activities involving Native American communities, given their potential and credibility to be a bridge and help lead this important work |

| • Foster networking and collaboration in research, while drawing increased emphasis on integration of Native American cultural knowledge. |

| Researchers |

| • Work with tribal/community advisory boards to ensure culturally safe research methods and engagement |

| • Recognise collective consent, in the form of a tribal resolution, may be required to authorise research within some tribal jurisdictions |

| • Seek human subjects review from tribal Institutional Review Boards, even though it may not be part of funding requirements |

| • Standardise reporting of studies involving Native American communities to assist in developing an evidence base (e.g. identification of community members and Native American researchers involved in the research, if authorised by community partners) |

| Research Enterprise (e.g. academic institutions, funding agencies) |

| • Understand and acknowledge the importance of cultural safety and tribal sovereignty in research with Native American communities |

| • Acknowledge that tribes have ownership over data within tribal jurisdictions |

| • Include tribal research ethics training in all ethics trainings for IRBs, including those in Native American and non-Native American communities |

| • Support accountable and sustainable engagement in research with Native American communities via considerations in funding mechanisms, evaluation frameworks, and impact assessments (e.g. longer timelines, embedded planning periods) |

| • Promote cultural safety within research with Native American communities in funding announcements and evaluate implementation of such practices as part of project governance |

In undertaking research with Native American communities, it is important to distinguish between a tribally governed community and one without this designation. The literature typically highlights tribes that have clear jurisdictional authority but does not adequately describe the spectrum of governance and/or authority that exists across communities, as many Native Americans reside on lands outside of tribal jurisdiction (Jernigan et al., 2015; U.S. Health and Human Services, 2018; Walters et al., 2019). Likewise, capacity to oversee research varies among communities. Establishing agreements between communities without an IRB (e.g. urban communities, reservations without an IRB) and those with such capacity should be considered to enhance cultural safety in research with Native Americans more broadly (Around Him et al., 2021).

CBPR and other participatory approaches have been widely promoted and are important for research with Native Americans. This may look vastly different depending on the study design (e.g. one vs. multiple communities, national study) and setting (e.g. urban vs. reservation-based, where jurisdictional authority varies). For example, partnerships with a specific community may develop an advisory board comprised of local experts, whereas a multi-tribal study may include representatives from each community and require multiple IRB reviews to accommodate each jurisdiction.

Accountability and sustainability extend beyond the research partnership to institutional responsibilities of both funders and researchers. To promote cultural safety in research with Native Americans, all institutions – particularly academic institutions – need to build capacity, knowledge, researchers, and networks. Implementation of robust standards, guiding principles for engagement, and monitoring mechanisms have potential to support cultural safety. Institutional responsibilities should include training for funders and IRB members on research harms experienced by Native Americans and understanding and respecting tribal sovereignty in research.

Limitations

This manuscript intentionally focused on literature pertaining to Native Americans. Findings are intrinsically bound by geopolitical boundaries of these communities and Native American systems of knowledge. We recognise that even with the inclusion of the grey literature, tribal elders and leaders often provide cultural teachings and guidance to researchers at conferences and gatherings, which are invaluable though not included in this review. We encourage consideration of these venues in future efforts to synthesise best practices for promoting cultural safety in research with Native Americans.

Despite the contextually bound nature of our results, this manuscript has several notable strengths. We used rigorous methods to assess peer-reviewed and grey literature where best practices are often documented. Notably, these findings have been distilled and interpreted by Native American (TNB, KH, DAH, NN) and non-Native authors (ED, KN, DW, LKK, PMD). Although the literature focuses on Native Americans, the recommendations have implications for other Indigenous populations and underscore the need to promote cultural safety in research.

Conclusions

The health outcomes of Native Americans are a source of concern globally, but it is critical that good intentions do not compound injustice borne from centuries of colonialism, neglect, and alienation. To this end, strategic actions are required on the part of funders, academic institutions, and researchers, including resource allocation and refinement of institutional policies and procedures to promote cultural safety. Communicating clearly defined policies and procedures that promote culturally safe research with Native Americans to all partners is imperative. This recalibration in power differentials and approaches will facilitate culturally safe, accountable, and sustainable research with Native Americans going forward.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We respectfully acknowledge the ancestral lands and Indigenous peoples of the world. We are grateful to the Indigenous communities leading us with strength, honour, and resiliency as they engage in the research process. We give thanks to those who contributed to the peer-reviewed and grey literature articles in this review, as we recognise the dedication and commitment it takes to carry out and publish research to improve the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples.

Funding:

D. Around Him was supported by the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation through the Child Trends Impact Plan.

Footnotes

Disclaimer statements

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2021.2015414.

Used throughout to encompass American Indian and Alaska Native peoples in the United States, with “Indigenous” used to reference Indigenous peoples globally.

Used to respectfully encompass the varied cultural, social, economic, and political contexts in which Native Americans live, including reservation, rural, and urban communities, with recognition that tribal sovereignty applies to tribal nations.

References

- Allen J, & Mohatt GV (2014). Introduction to ecological description of a community intervention: Building Prevention through collaborative field based research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 54(1–2), 83–90. 10.1007/s10464-014-9644-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angal J, & Andalcio T (2015). CRCAIH tribal IRB toolkit. Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health. http://www.aihec.org/our-stories/docs/BehavioralHealth/CRCAIH_Tribal_IRB_Toolkit.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Angal J, Petersen JM, Tobacco D, & Elliott AJ (2016). Ethics review for a multi-site project involving Tribal Nations in the Northern Plains. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 11(2), 91–96. 10.1177/1556264616631657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Around Him D, Aguilar TA, Frederick A, Larsen H, Seiber M, & Angal J (2019). Tribal IRBs: A framework for understanding research oversight in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research, 26(2), 71–95. 10.5820/aian.2602.2019.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Around Him D, Gachupin FC, & Freeman WL (2021). Research with American Indian and Alaska Native individuals, tribes, and communities. In Bankert EA, Gordon BG, Hurley EA, & Shriver SP (Eds.), Institutional review board: management and function (3rd ed., pp. 563–580). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Blacksher E, Nelson C, Van Dyke E, Echo-Hawk A, Bassett D, & Buchwald D (2016). Conversations about community-based participatory research and trust: “We are explorers together”. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 10(2), 305–309. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard JW, Tallbull G, Wolpert C, Powell J, Foster MW, & Royal C (2017). Barriers and strategies related to qualitative research on genetic ancestry testing in indigenous communities. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 12(3), 169–179. 10.1177/1556264617704542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie T, Azar K, Wallen G, O’Hanlon Solis M, Adams K, & Kub J (2019). A conceptual model for establishing collaborative partnerships between universities and Native American communities. Nurse Researcher, 27(1), 27–32. 10.7748/nr.2019.e1613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie TN, Dana-Sacco G, López MM, & Wetsit L (2017). Essentials of research engagement with Native American tribes: Data collection reflections of a tribal research team. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 11(3), 301–307. 10.1353/cpr.2017.0035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brockie TN, Heinzelmann M, & Gill J (2013). A framework to examine the role of epigenetics in health disparities among Native Americans. Nursing Research and Practice, 2013(6), 1–9. 10.1155/2013/410395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll SR, Lonebear DR, & Martinez A (2017). Policy brief: Data governance for Native Nation rebuilding. The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute. https://nnigovernance.arizona.edu/policy-brief-data-governance-native-nation-rebuilding [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick JQ, Copeland KC, Daniel MR, Erb-Alvarez JA, Felton BA, Khan SI, Saunkeah BR, Wharton DF, & Payan ML (2014). Partnering in research: A national research trial exemplifying effective collaboration with American Indian Nations and the Indian Health Service. American Journal of Epidemiology, 180(12), 1202–1207. 10.1093/aje/kwu246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Saha R, Lachapelle P, Jennings D, Colclough Y, Cooper C, Cummins C, Eggers MJ, Fourstar K, Harris K, Kuntz SW, Lafromboise V, Laveaux D, McDonald T, Real Bird J, Rink E, & Webster L (2011). Applying Indigenous community-based participatory research principles to partnership development in health disparities research. Family & Community Health, 34(3), 246–255. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318219606f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claw KG, Anderson MZ, Begay RL, Tsosie KS, Fox K, & Garrison NA (2018). A framework for enhancing ethical genomic research with Indigenous communities. Nature Communications, 9(1), 1–7. 10.1038/s41467-018-05188-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health (CRCAIH). (2019). CRCAIH research data management toolkit: Version 2. Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health. https://www.crcaih.org/assets/Resources/Methodology/CRCAIH_ResearchDataToolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Crump AD, Etz K, Arroyo JA, Hemberger N, & Srinivasan S (2020). Accelerating and strengthening Native American health research through a collaborative NIH initiative. Prevention Science, 21 (S1), 1–4. 10.1007/s11121-017-0854-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J, & Reid P (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 1–17. 10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drabiak-Syed K (2010). Lessons from Havasupai Tribe v. Arizona State University Board of regents: Recognizing group, cultural, and dignitary harms as legitimate risks warranting integration into research practice. Journal of Health and Biomedical Law, 6(2), 175–226. 10.13016/dhke-perq. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott AJ, White Hat ER, Angal J, Grey Owl V, Puumala SE, & Kenyon DB (2016). Fostering social determinants of health transdisciplinary research: The Collaborative Research Center for American Indian Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(1), 1–12. 10.3390/ijerph13010024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engage for Equity Research Team. (2017). Promising practices of CBPR and community engaged research partnerships. Engage for Equity. https://engageforequity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Promising-Practices-Guide-12.7.12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- First Nations Information Governance Committee (FNIGC). (2020). A First Nations data governance strategy. https://fnigc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/FNIGC_FNDGS_report_EN_FINAL.pdf

- Fleischhacker S, Vu M, Ries A, & McPhail A (2011). Engaging tribal leaders in an American Indian healthy eating project through modified talking circles. Family & Community Health, 34(3), 202–210. 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31821960bb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachupin FC (2019a). How to build and sustain a tribal IRB. The Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/142/2019/05/IRB-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gachupin FC (2019b). How to conduct research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. The Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention. https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/142/2019/05/IRB-3.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gachupin FC (2019c). How to review research to benefit tribal communities. The Partnership for Native American Cancer Prevention https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/142/2019/05/IRB-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gachupin FC, Lameman B, & Molina F (2019). Guidelines for researchers: A guide to effectively mutually beneficial research partnerships with American Indian tribes, families, and individuals. University of Arizona, Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine. https://in.nau.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/142/2019/05/Guidelines-2019423.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Garrison NA, & Cho MK (2013). Awareness and acceptable practices: IRB and researcher reflections on the Havasupai Lawsuit. AJOB Primary Research, 4(4), 55–63. 10.1080/21507716.2013.770104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison NA, Hudson M, Ballantyne LL, Garba I, Martinez A, Taualii M, Arbour L, Caron NR, & Rainie SC (2019). Genomic research through an Indigenous lens: Understanding the expectations. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics, 20(1), 495–517. 10.1146/annurev-genom-083118-015434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin K, Stapleton J, Kirkpatrick SI, Hanning RM, & Leatherdale ST (2015). Applying systematic review search methods to the grey literature: A case study examining guidelines for school-based breakfast programs in Canada. Cochrane Systematic Reviews, 4(138), E1–E10. 10.1186/s13643-015-0125-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Garroutte EM, Leading Fox S, Geiger SD, & Manson SM (2011). Theory and practice in participatory research: Lessons from the Native Elder Care Study. The Gerontologist, 51(3), 285–294. 10.1093/geront/gnq130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, & Trimble JE (2012). American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse perspectives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 131–160. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding A, Harper B, Stone D, O’Neill C, Berger P, Harris S, & Donatuto J (2012). Conducting research with tribal communities: Sovereignty, ethics, and data-sharing issues. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(1), 6–10. 10.1289/ehp.1103904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy LJ, Hughes A, Hulen E, & Schwartz AL (2016). Implementing qualitative data management plans to ensure ethical standards in multi-partner centers. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 11(2), 191–198. 10.1177/1556264616636233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon A (2010, April 21). Indian Tribe wins fight to limit research of its DNA. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/22/us/22dna.html

- Hicks S, Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila M, Belone L, Lucero J, Magarati M, Mainer E, Martin D, Muhammad M, Oetzel J, Pearson C, Sahota P, Simonds V, Sussman A, Tafoya G, & White Hat E (2012). Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 6(3), 289–299. 10.1353/cpr.2012.0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeft TJ, Burke W, Hopkins SE, Charles W, Trinidad SB, James RD, & Boyer BB (2014). Building partnerships in community-based participatory research: Budgetary and other cost considerations. Health Promotion Practice, 15(2), 263–270. 10.1177/1524839913485962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull SC, & Wilson DR (2017). Beyond Belmont: Ensuring respect for AI/AN communities through tribal IRBs, laws, and policies. American Journal of Bioethics, 17(7), 60–62. 10.1080/15265161.2017.1328531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huria T, Palmer SC, Pitama S, Beckert L, Lacey C, Ewen S, & Smith LT (2019). Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: The CONSIDER statement. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(173), 1–9. 10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James R, Tsosie R, Sahota P, Parker M, Dillard D, Sylvester I, Lewis J, Klejka J, Muzquiz L, Olsen P, Whitener R, Burke W, & Group K (2014). Exploring pathways to trust: A tribal perspective on data sharing. Genetics in Medicine, 16(11), 820–826. 10.1038/gim.2014.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James RD, West KM, Claw KG, EchoHawk A, Dodge L, Dominguez A, Taualii M, Forquera R, Thummel K, & Burke W (2018). Responsible research with Urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. American Journal of Public Health, 108(12), 1613–1616. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, D’Amico EJ, Duran B, & Buchwald D (2020). Multilevel and community-level interventions with Native Americans: Challenges and opportunities. Prevention Science, 21(Suppl 1), 65–73. 10.1007/s11121-018-0916-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan VBB, Peercy M, Branam D, Saunkeah B, Wharton D, Winkleby M, Lowe J, Salvatore AL, Dickerson D, Belcourt A, D’Amico E, Patten CA, Parker M, Duran B, Harris R, & Buchwald D (2015). Beyond health equity: Achieving wellness within American Indian and Alaska Native communities. American Journal of Public Health, 105(Suppl 3), S376–S379. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetter KM, Yarborough M, Cassady DL, & Styne DM (2015). Building research capacity with members of underserved American Indian/Alaskan Native communities: Training in research ethics and the protection of human subjects. Health Promotion Practice, 16(3), 419–425. 10.1177/1524839914548450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Knox-Nicola P, & Schmid K (2015). The Waponahki Tribal Health Assessment: Successfully using CBPR to conduct a comprehensive and baseline Health Assessment of Waponahki Tribal members. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 26(3), 889–907. 10.1353/hpu.2015.0099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian DA, Smith II T, & Hunt RA (2017). Ethical challenges inherent in the evaluation of an American Indian/Alaskan Native circles of care project. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3–4), 336–345. 10.1002/ajcp.12192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jumper-Reeves L, Dustman PA, Harthun ML, Kulis S, & Brown E (2014). American Indians’ cultures: How CBPR illuminated inter-tribal cultural elements fundamental to an adaptation effort. Prevention Science, 15(4), 547–556. 10.1007/s11121-012-0361-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kading ML, Gonzalez MB, Herman KA, Gonzalez JG, & Walls ML (2019). Living a good way of life: Perspectives from American Indian and First Nation young adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 21–33. 10.1002/ajcp.12372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley A, Belcourt-Dittloff A, Belcourt C, & Belcourt G (2013). Research ethics and Indigenous communities. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2146–2152. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirmayer LJ, Dandeneau S, Marshall E, Phillips MK, & Willamson KJ (2011). Rethinking resilience from Indigenous perspectives. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(2), 84–91. 10.1177/070674371105600203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiam nayri Wingara Indigenous Data Sovereignty Collective. (2018). Key principles. Maiam nayri Wingara. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://www.maiamnayriwingara.org/key-principles

- Mashford-Pringle A, & Pavagadhi K (2020). Using OCAP and IQ as frameworks to address a history of trauma in Indigenous health research. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(10), E868–E873. 10.1001/amajethics.2020.868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland A (2011). Culturally safe nursing research: Exploring the use of an Indigenous research methodology from an indigenous researcher’s perspective. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(4), 362–367. 10.1177/1043659611414141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales CT, Muzquiz LI, Howlett K, Azure B, Bodnar B, Finley V, Incashola T, Mathias C, Laukes C, Beatty P, Burke W, Pershouse MA, Putnam EA, Trinidad SB, James R, & Woodahl EL (2016). Partnership with the confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes: Establishing an advisory committee for pharmacogenetic research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 10(2), 173–183. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton DJ, Proudfit J, Calac D, Portillo M, Lofton-Fitzsimmons G, Molina T, Flores R, Lawson-Risso B, & Majel-McCauley R (2013). Creating research capacity through a tribally based Institutional Review Board. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2160–2164. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health Tribal Health Research Office (NIHTHRO). (2017). Meeting summary: Tribal data sharing and genetics policy development workshop. University of New Mexico Community Environmental Health Program. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/dpcpsi/document/Meeting20Summary_Tribal20Genetic20Research20and20Data20Sharing20Policy20Workshop_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- NCAI Policy Research Center & MSU Center for Native Health Partnerships. (2012). ‘Walk softly and listen carefully’: Building research relationships with tribal communities. National Congress for American Indians and Montana State University. https://www.ncai.org/attachments/PolicyPaper_SpMCHTcjxRRjMEjDnPmesENPzjHTwhOlOWxlWOIWdSrykJuQggG_NCAI-WalkSoftly.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco CM, Daley SM, Brown T, Filippi M, Greiner KA, & Daley CM (2013). Moving forward: Breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2152–2159. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, … Moher D (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71), 1–9. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker M, Pearson C, Donald C, & Fisher CB (2019). Beyond the Belmont principles: A community-based approach to developing an Indigenous ethics model and curriculum for training health researchers working with American Indian and Alaska Native communities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 9–20. 10.1002/ajcp.12360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Parker M, Fisher CB, & Moreno C (2014). Capacity building from the inside out: Development and evaluation of a CITI ethics certification training module for American Indian and Alaska Native community researchers. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 9 (1), 46–57. 10.1525/jer.2014.9.1.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Parker M, Zhou C, Donald C, & Fisher CB (2019). A culturally tailored research ethics training curriculum for American Indian and Alaska Native communities: A randomized comparison trial. Critical Public Health, 29(1), 27–39. 10.1080/09581596.2018.1434482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmus SM, Charles B, John S, & Allen J (2019). With a spirit that understands: Reflections on a long-term community science initiative to end suicide in Alaska. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 34–45. 10.1002/ajcp.12356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rautaki Ltd & Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. (n.d.). Principles of Kaupapa Māori. Rangahau. http://www.rangahau.co.nz/rangahau/27/ [Google Scholar]

- Ravenscroft J, Schell LM, & Cole T (2015). Applying the community partnership approach to human biology research. American Journal of Human Biology, 27(1), 6–15. 10.1002/ajhb.22652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonds VW, & Christopher S (2013). Adapting Western research methods to Indigenous ways of knowing. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), 2185–2192. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skewes MC, Gonzalez VM, Gameon JA, FireMoon P, Salois E, Rasmus SM, Lewis JP, Gardner SA, Ricker A, & Martel R (2020). Health disparities research with American Indian communities: The importance of trust and transparency. American Journal of Community Psychology, 66(3–4), 302–313. 10.1002/ajcp.12445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton CR (2014). Crossing methodological borders: Decolonizing community-based participatory research. Qualitative Inquiry, 20(5), 573–583. 10.1177/1077800413505541 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas LR, Rosa C, Forcehimes A, & Donovan DM (2011). Research partnerships between academic institutions and American Indian and Alaska Native Tribes and organizations: Effective strategies and lessons learned in a multisite CTN study. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(5), 333–338. 10.3109/00952990.2011.596976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Health and Human Services. (2018). Urban Indian Health Program. Retrieved May 28, 2021, from https://www.ihs.gov/sites/newsroom/themes/responsive2017/display_objects/documents/factsheets/UrbanIndianHealthProgram_FactSheet.pdf

- Walls ML, Whitesell NR, Barlow A, & Sarche M (2019). Research with American Indian and Alaska Native populations: Measurement matters. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 18(1), 129–149. 10.1080/15332640.2017.1310640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K, Walls M, Dillard D, & Kaur J (2019). American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) research in the health sciences: Critical considerations for the review of research applications. National Institutes of Health, Tribal Health Research Office. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/Critical_Considerations_for_Reviewing_AIAN_Research_508.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Warne D, & Bane Frizell L (2014). American Indian Health policy: Historical trends and contemporary issues. American Journal of Public Health, 104(suppl 3), S263–S267. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt DC, Hartmann WE, Allen J, Burack JA, Charles B, D’Amico EJ, Dell CA, Dickerson DL, Donovan DM, Gone JP, O’Connor RM, Radin SM, Rasmus SM, Venner KL, & Walls ML (2019). Substance use research with Indigenous communities: Exploring and extending foundational principles of community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64 (1–2), 146–158. 10.1002/ajcp.12363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, & Knafl K (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, Blomberg N, Boiten J-W, Santos LB, Bourne PE, Bouwman J, Brookes AJ, Clark T, Crosas M, Dillo I, Dumon O, Edmunds S, Evelo CT, Finkers R, … Mons B (2016). The FAIR guiding principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3(160018), 1–9. 10.1038/sdata.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D, & Neville S (2009). Culturally safe research with vulnerable populations. Contemporary Nurse, 33(1), 69–79. 10.5172/conu.33.1.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan NP, Bartgis J, & Demers D (2014). Promoting ethical research with American Indian and Alaska Native people living in urban areas. American Journal of Public Health, 104(11), 2085–2091. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.