Abstract

Elucidating taste sensing systems in chickens is an important step toward understanding poultry nutrition. Amino acid taste receptors, type 1 taste receptors 1 and 3 (T1R1 and T1R3, respectively), are expressed in chicken taste cells, and chicken T1R1/T1R3 is activated by L-alanine (L-Ala) and L-serine (L-Ser), but not by L-proline (L-Pro). However, it is not clear whether chickens have a gustatory perception of L-amino acids. Here, we found that chickens conditioned to avoid either L-Ala, L-Ser, or L-Pro solutions could successfully learn to avoid the corresponding L-amino acid solution in the conditioned taste aversion (CTA) test. Because CTA is a well-established learning paradigm generated specifically by pairing gustatory perception and gastrointestinal malaise, the present study suggests that chickens can sense L-amino acids by gustatory perception. In addition, we found that the expression of the T1R1 and T1R3 genes was significantly downregulated in response to chronic exposure to L-Ala solution, but not to acute oral stimulation. Taken together, the present study suggests that chickens have a gustatory perception of L-amino acids, and the expression of T1R1/T1R3 mRNAs in the oral cavity can be regulated by L-amino acid intake. Since chickens can detect L-Pro solutions, additional amino acid receptors, other than T1R1/T1R3, may be involved in L-amino acid taste detection in chickens.

Keywords: amino acid, chicken, taste, taste receptor, umami

Introduction

The sense of taste plays an important role in detecting nutrients and toxic substances in food and controls the feeding behavior of animals. Therefore, elucidating the sense of taste in chickens will improve our understanding of poultry nutrition and feeding strategies in the poultry industry. Umami is one of the five basic tastes (sweet, umami, bitter, sour, and salty) and is elicited by some L-amino acids (Roper and Chaudhari, 2017). Since L-amino acids are components of dietary protein, which is one of the three major nutrients in feed, oral L-amino acid taste sensing may play a major role in food choice in chickens. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate whether chickens have gustatory perception of L-amino acids.

Heterodimers of taste receptor type 1, 1 and 3 (T1R1/T1R3), and metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 and 4 (mGluR1 and mGluR4, respectively) in mammals are candidates for umami taste receptors (Chaudhari et al., 2000; Zhao et al., 2003; Yasumatsu et al., 2014). While human T1R1/T1R3 is activated exclusively by L-glutamate and L-aspartate, rodent T1R1/T1R3 is activated by various L-amino acids (Toda et al., 2013). Therefore, the repertoire of L-amino acids that elicit gustatory perception depends on the species.

T1R1, T1R3, mGluR1, and mGluR4 mRNAs are expressed in the oral tissues of chickens (Yoshida et al., 2015), and T1R1 and T1R3 are expressed in chicken taste cells (Yoshida et al., 2019; Yoshida et al., 2021a). Moreover, chicken T1R1/T1R3 is activated by L-alanine (L-Ala) and L-serine (L-Ser) but not by L-proline (L-Pro) (Baldwin et al., 2014). However, whether chickens can detect L-amino acids using the taste sense is not yet understood. The conditioned taste aversion (CTA) test is a well-established learning paradigm characterized by a specific association between gustatory perception and gastrointestinal malaise (Delay et al., 2015). Previously, we found that chickens could learn to avoid the mixture solution of monosodium L-glutamate (MSG) and inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP) (Yoshida et al., 2018a) and oleic acid solution (Kawabata et al., 2021) by the CTA test. In the present study, we used the CTA test to investigate whether chickens could detect L-amino acid solutions using gustatory perception. We tested the gustatory perception of chickens to L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro as the affinities of these L-amino acids to chicken T1R1/T1R3 have previously been characterized (Baldwin et al., 2014). Exposure to a bitter solution has been reported to affect the oral mRNA levels of bitter taste receptors and downstream signaling molecules in chickens (Cheled-Shoval et al., 2014). Therefore, we also investigated the effects of exposure to L-Ala solution on the mRNA levels of L-amino acid taste receptors T1R1 and T1R3, and their downstream signaling molecules, including transient receptor potential, subfamily M, member 5 (TRPM5), which is involved in membrane depolarization of taste cells in mice (Zhang et al., 2007), and calcium homeostasis modulator 1 and 3 (CALHM1 and CALHM3, respectively), which are involved in neurotransmitter release from taste cells to taste nerves in mice (Ma et al., 2018). Because L-Ala has the strongest activity for chicken T1R1/T1R3 among the three amino acids, L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro (Baldwin et al., 2014), we chose L-Ala for the exposure experiment.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

L-Ala, L-Ser, L-Pro, LiCl, and NaCl were obtained from the FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan). They were dissolved in reverse osmosis water prior to the experiments. L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro solutions were used as L-amino acid taste stimuli. A LiCl solution was used to induce gastrointestinal malaise in animals. An NaCl solution (saline) was used as the control solution for the LiCl solution.

Animals

The use of animals throughout the study was approved by the Committee for Laboratory Animal Care and Use at the Kyushu University (approval no. A30-335-1) and Experimental Animal Committee guidelines at the Ibaraki University (approval no. 21190). Animal use was in compliance with the Guide for Animal Experiments issued by the Kyushu University and Ibaraki University, Law Concerning the Human Care and Control of Animals (Law No. 105; October 1, 1973), Japanese Government Notification on the Feeding and Safekeeping of Animals (Notification No. 6; March 27, 1980), and ARRIVE guidelines. Fertilized eggs or chicks of the Rhode Island Red (RIR) strain were obtained from the National Livestock Breeding Center Okazaki Station (Okazaki, Japan). Chicks and their offspring were used in these experiments. The chicks were maintained in a box brooder with a heating system (Showa Furanki, Saitama, Japan) at a temperature of approximately 30°C under 24 h lighting. The chicks were provided with normal tap water ad libitum, except during the water deprivation period of each experiment. The chicks used for experiments 1 and 2 were supplied with commercial layer feed (Feed One Birdie; Kashima Shiryo Co. Ltd., Kashima, Japan) ad libitum, and the chicks used for experiment 3 were given free access to a different commercial layer feed (Powerlayer 17Y; JA Kitakyushu Kumiai Shiryo, Fukuoka, Japan) during the entire experimental period. The chicks were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital sodium solution or cervical dislocation, followed by decapitation.

Experiment 1: Conditioned Taste Aversion (CTA) Test

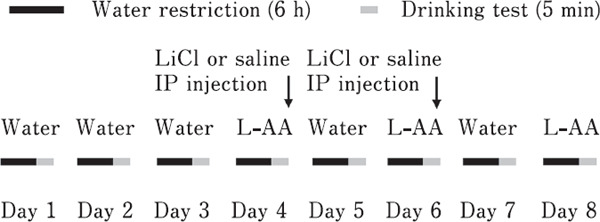

CTA tests were conducted as previously reported (Yoshida et al., 2018a; Kawabata et al., 2021). Thirty-six 5-day-old chicks (mixed males and females) were used at the start of the CTA tests. CTA tests were performed for eight consecutive days (Fig. 1). During the test, chicks were supplied with commercial layer feed ad libitum and water was restricted for 6 h before the tests throughout the experimental period. From days 1 to 3, the chicks were presented with normal tap water for 5 min. On day 4, the chicks were presented with L-amino acid solutions (0.3 M L-Ala, L-Ser, or L-Pro), and immediately intraperitoneally (IP) injected with 230 mg/kg bodyweight of 0.24 M LiCl solution to induce gastrointestinal malaise or the same volume of saline as a control. On day 5, the chicks were provided with normal tap water. On day 6, the chicks were presented with L-amino acid solutions, and LiCl solution or saline was immediately IP injected to induce gastrointestinal malaise or as control, respectively. On day 7, the chicks were provided with normal tap water. On day 8, the chicks were presented with L-amino acid solutions. Water and L-amino acid solution intakes were calculated by subtracting the weights of the solution bottles after the experiments from their weights at the start of the experiments.

Fig. 1.

Experimental procedure of the conditioned taste aversion (CTA) test. Throughout the experimental period, which included the training period, chickens were deprived of water for 6 h (from 9:00 am to 3:00 pm) and then presented water or L-amino acid solutions for 5 min. After the training period for water drinking (days 1 to 3), chickens were provided with L-amino acid solutions and administered an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of LiCl or saline on days 4 and 6. Water or L-amino acid solution intakes for 5 min were measured from days 5 to 8.

Preference ratios were calculated as L-amino acid solution intake/total fluid intake (L-amino acid intake + water intake), as previously reported (Kawabata et al., 2022). We used the water intake on day 5 and L-amino acid solution intake on day 6 to calculate the preference ratio after the first conditioning. The water intake on day 7 and L-amino acid solution intake on day 8 were used to calculate the preference ratio after the second conditioning.

According to our observations, the 0.3 M L-amino acid solutions used in the present study had no specific visual color or olfactory cues. Our previous study also suggested that the viscosity of the solution itself does not induce CTA (Kawabata et al., 2021).

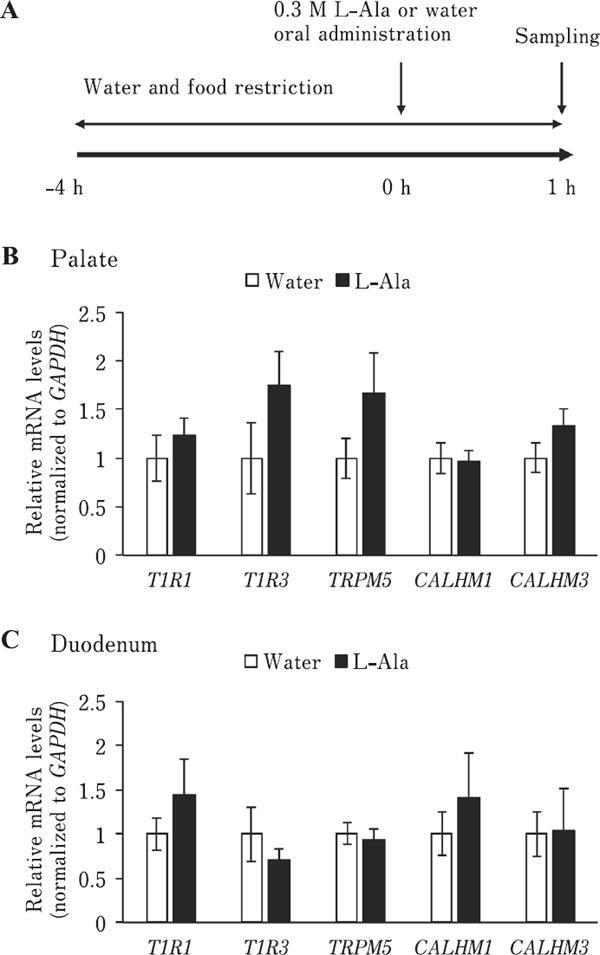

Experiment 2: Single Oral Stimulation by L-Ala Solution

Twelve 7-day-old chicks (males and females) were used at the start of the experiment. The chicks were fasted and water-deprived for 4 h before the experiment until 1 h after oral administration. The chicks were orally administered 4 mL of 0.3 M L-Ala solution or water, and 1 h later, the palate and duodenum were collected (Fig. 7A). Only 2% of taste buds are distributed in the tongues of chickens, while 69% are distributed in the palates (Ganchrow and Ganchrow, 1985). Thus, we used the palate as the main taste organ in the chickens. The collected samples were used for quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis to measure the expression levels of mRNAs related to L-amino acid taste sensing.

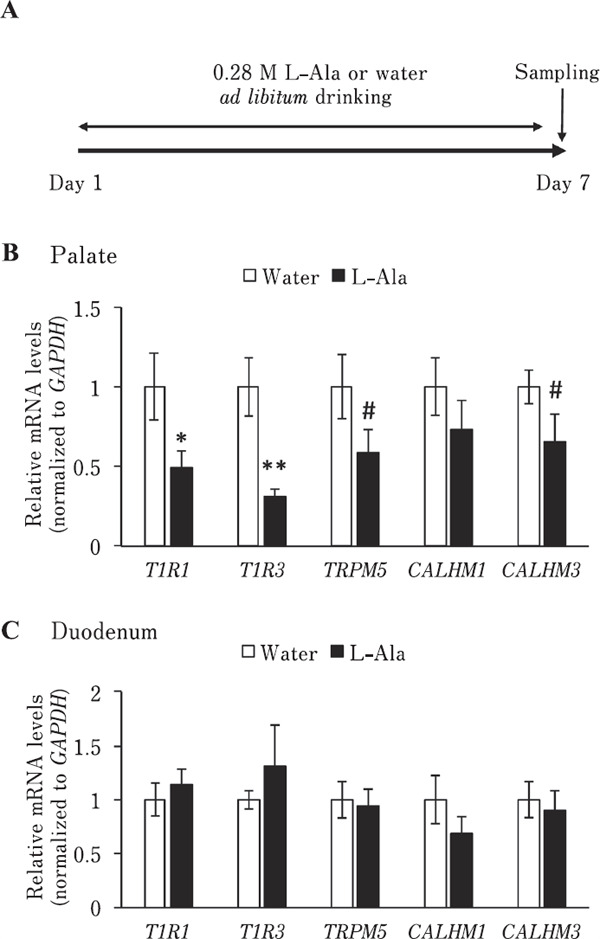

Experiment 3: Chronic Exposure to L-Ala Solution for One Week

Fourteen 10–13-day-old chicks (males and females) were used at the start of the experiment. Chicks were divided into two groups (water and L-Ala) according to their bodyweight. The chicks were given free access to commercial layer feed and water, for the water group, or 0.28 M L-Ala solution, for the L-Ala group, for 1 week. The palate and duodenum were then collected (Fig. 8A). The collected samples were used for qRT-PCR analysis to measure the expression of mRNAs related to L-amino acid taste sensing.

qRT-PCR

The palate, tongue tip, and base of the oral cavity were collected from four 4-week-old chickens (males and females) to analyze the expression of CALHM1 and CALHM3 in the oral cavity. Tongue tips, where only a few taste buds are located, were collected in accordance with our previous report (Kudo et al., 2008). Total RNA was isolated from the palate, tongue tip, and base of the oral cavity from 4-week-old chickens and from the palate and duodenum from chickens subjected to L-Ala or water exposure for 1 week using ISOGEN II reagent (Nippon Gene, Tokyo, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genomic DNA was removed using DNase I (Nippon Gene) following the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. The PCR mixture had a total volume of 10 µL and consisted of 5.0 µL 2 × OneStep SYBR RT-PCR Buffer 4 (Takara Bio, Otsu, Japan), 0.4 µL PrimeScript 1 step Enzyme Mix 2 (Takara Bio), 0.2 µL forward primer (10 µM), 0.2 µL reverse primer (10 µM), 0.2 µL ROX Reference Dye II (50×) (Takara Bio), 1.0 µL total RNA (100 ng/µL), and 3.0 µL RNase Free dH2O (Takara Bio). The PCR reactions were conducted under the following conditions: 42°C for 5 min, 95°C for 10 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 34 s, followed by a melting curve analysis from 60°C to 95°C. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Table 1. The primers used in the present study.

| Target gene | Accession no. | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1R1 | XM_015297004.1 | CCCTGGCAGCTCCTACAAAA | TACGAATGTTCCCGTTGGC | 88 |

| T1R3 | XM_425740.3 | TGTTACGACCGCAGTGAGAG | GGGAACTCTGTGAGCAGGAC | 335 |

| TRPM5 | XM_003641321.3 | ATAAAGCCGTGTCTCCCGTG | ACTGCTGCAGTATTTGGTCTC | 127 |

| CALHM1 | XM_015288733.2 | TTTCGGATGGTCTTCCAGTTCC | CAGGGACAGTTGAAATCAAAGGC | 119 |

| CALHM3 | XM_025152006.1 | TTAGCCCTGGCTAGCGTAAAG | CACGAACATGATCCCCAAGC | 99 |

| GAPDH | NM_20435.1 | ACTGTCAAGGCTGAGAACGG | ACCTGCATCTGCCCATTTGA | 99 |

Total RNA was isolated from the palate and duodenum of chicks with single oral L-Ala or water stimulation using the ISOGEN II reagent (Nippon Gene), and cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers used are listed in Table 1. The PCR mixture had a total volume of 10 µL and consisted of 5.0 µL SsoFast Eva-Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), 0.2 µL forward primer (10 µM), 0.2 µL reverse primer (10 µM), 1.0 µL cDNA template (synthesized from 50 ng total RNA), and 3.6 µL ultrapure water. The PCR reactions were conducted under the following conditions: 95°C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 58°C for 5 s, followed by a melting curve analysis from 60°C to 95°C. GAPDH was used as an internal control.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (2011; Redmond, WA, USA). An unpaired t-test, with or without Bonferroni correction, was used for testing. The Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Gustatory Perception of L-Amino Acid Solutions in Chickens

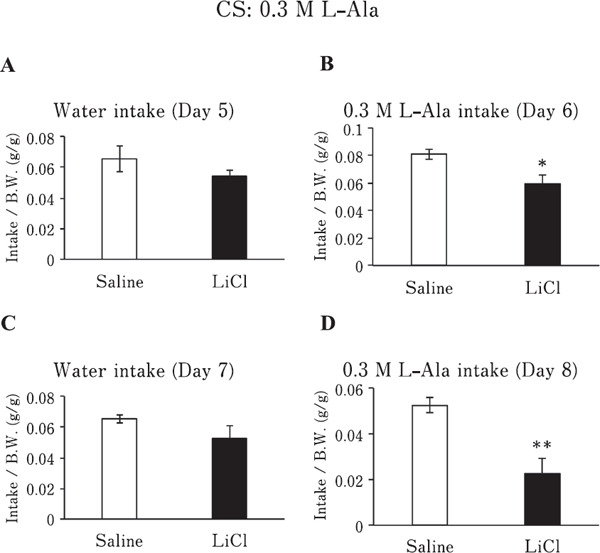

Chickens conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Ala solution by an IP injection of LiCl showed significantly reduced 0.3 M L-Ala solution intakes after the first conditioning (Fig. 2B; P <0.05) and second conditioning (Fig. 2D; P<0.01), compared with those of the saline-injected group. In contrast, the water intake of the LiCl and saline groups did not significantly change (P>0.05) after the first conditioning (Fig. 2A) or second conditioning (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Water or 0.3 M L-Ala solution intake/bodyweight (BW) of chickens conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Ala solution (conditioned stimulus; CS) by LiCl or given saline (control). (A & C) Water intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 5 (A) or day 7 (C). (B & D) 0.3 M L-Ala solution intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 6 (B) or day 8 (D). Values represent mean±SE (saline; n=6, LiCl; n=6). * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, unpaired t-test.

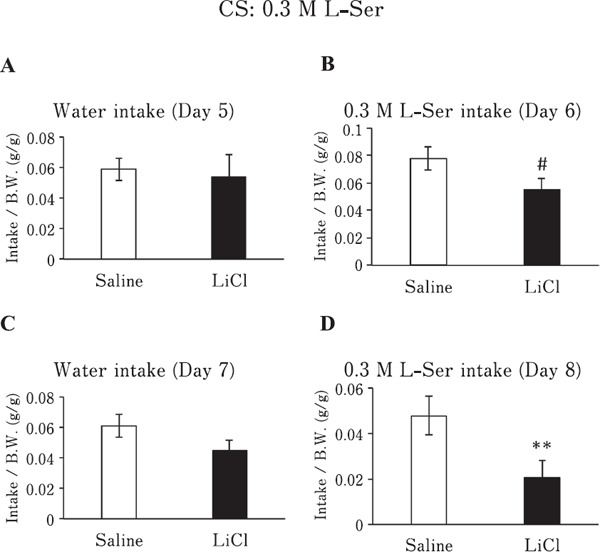

Chickens, conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Ser solution, tended to avoid 0.3 M L-Ser solution after the first conditioning (Fig. 3B; P<0.1), and significantly avoided it after the second conditioning (Fig. 3D; P<0.01), as L-Ser intake was significantly lower than that in the saline-injected group. Conversely, the water intake of the LiCl and saline groups did not sig-nificantly change (P>0.05) after the first (Fig. 3A) or second conditionings (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Water or 0.3 M L-Ser solution intake/BW of chickens conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Ser solution (CS) by LiCl or given saline. (A & C) Water intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 5 (A) or day 7 (C). (B & D) 0.3 M L-Ser solution intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 6 (B) or day 8 (D). Values represent mean±SE (saline; n=6, LiCl; n=7). # P<0.1 and ** P<0.01, unpaired t-test.

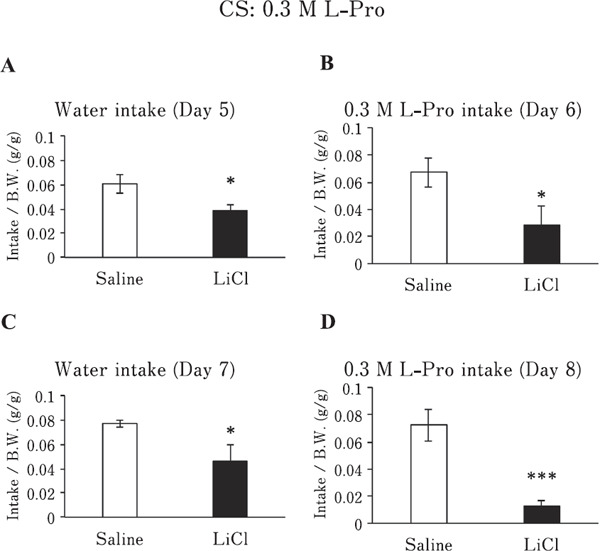

Chickens, conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Pro solution, significantly reduced their intake of the 0.3 M L-Pro solution after the first conditioning (Fig. 4B; P<0.05) and second conditioning (Fig. 4D; P<0.001), compared with that of the saline-injected group. Surprisingly, water intake of the LiCl and saline groups was also significantly affected (P<0.05) after the first (Fig. 4A) and second conditionings (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Water or 0.3 M L-Pro solution intake/BW of chickens conditioned to avoid 0.3 M L-Pro solution (CS) by LiCl or given saline. (A & C) Water intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 5 (A) or day 7 (C). (B & D) 0.3 M L-Pro solution intake/BW of chickens injected with LiCl or saline on day 6 (B) or day 8 (D). Values represent mean±SE (saline; n=6, LiCl; n=5). * P<0.05 and *** P<0.001, unpaired t-test.

Since water intake was slightly affected by conditioning when L-Pro solution was used (Fig. 4A, 4C), we calculated preference ratios to evaluate the effects of LiCl conditioning on preference for L-amino acid solutions or water (Fig. 5). We found that preference for the L-amino acid solutions was not changed by the first LiCl conditioning (Fig. 5A; P>0.05) for L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro, but was significantly decreased by the second LiCl conditioning (Fig. 5B; P<0.01 for L-Ala, P<0.05 for L-Ser, P<0.01 for L-Pro).

Fig. 5.

Preference ratios of L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro solu-tions for chickens conditioned to avoid the corresponding L-Ala, L-Ser, or L-Pro solutions by LiCl or saline with the first conditioning (A) and second conditioning (B). Preference ratios were calculated as L-amino acid solution intake/(L-amino acid solution intake + water intake). Preference ratios with the first conditioning were calculated using L-amino acid solution intake on day 6 and water intake on day 5 (A). Preference ratios with the second conditioning were calculated using L-amino acid solution intake on day 8 and water intake on day 7 (B). Values represent mean±SE (L-Ala: saline; n=6, LiCl; n=6; L-Ser: saline; n=6, LiCl; n=7; L-Pro: saline; n=6, LiCl; n=5). * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, unpaired t-test.

Exposure to L-Ala Solution Downregulated Oral mRNA Transcripts Involved in Umami Taste Sensing in Chickens

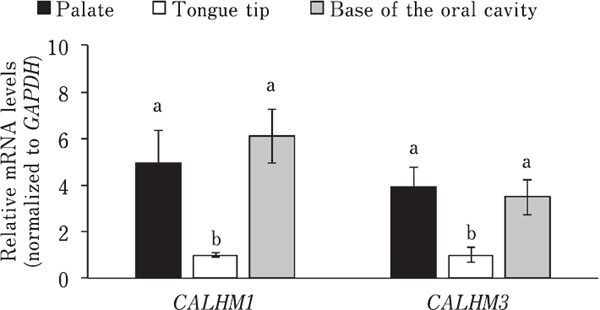

Bitter taste stimuli may affect oral mRNA expression related to bitter taste sensing in chickens (Cheled-Shoval et al., 2014). Therefore, we investigated whether oral mRNA expression related to L-amino acid taste sensing is regulated by oral L-amino acid stimulation in chickens. First, we confirmed that CALHM1 and CALHM3, which are involved in mammalian umami taste signaling (Ma et al., 2018), were more highly expressed in the palate and base of the oral cavity, where the taste buds are mainly located, than in the tongue tip, where only a few taste buds are located (Kudo et al., 2008) (Fig. 6). We found that single oral stimulation with L-Ala solution did not significantly affect (P>0.05) the mRNA expression of T1R1, T1R3, TRPM5, which is involved in the mammalian umami taste signaling pathway (Zhang et al., 2007) and expressed in chicken palate (Yoshida et al., 2018b), CALHM1, and CALHM3 in both the palate and duodenum of chickens (Fig. 7B, 7C). In contrast, we found that chronic exposure to L-Ala solution for one week significantly downregulated the oral mRNA expression of T1R1 (P<0.05) and T1R3 (P<0.01), specifically in the palate, but not of TRPM5, CALHM1, and CALHM3 (P>0.05) in neither the palate nor duodenum in chickens (Fig. 8).

Fig. 6.

Relative mRNA levels of CALHM1 and CALHM3 were significantly higher in the palate and base of the oral cavity compared with that in the tongue tip in chickens. Values represent mean relative mRNA levels (normalized to GAPDH)±SE (n=4). Bars without a common letter differ significantly, P<0.05, paired t-test with Bonferroni correction.

Fig. 7.

Single oral administration with L-Ala solution didn't significantly affect oral mRNA tanscripts involved in umami taste sensing in chickens. (A) Experimental procedure for single oral ad mini stration of 0.3 M L-Ala solution or water. Chickens were deprived of water and food for 4 h before the experiment until 1 h after oral stimulation. The palate and duodenum were collected 1 h after administration. (B & C) Relative mRNA levels of T1R1, T1R3, TRPM5, CALHM1, and CALHM3 in the palate (B) and duodenum (C) were not significantly different between the chickens orally stimulated by L-Ala solution or water. Values represent mean relative mRNA levels (normalized to GAPDH)±SE (n=6). P>0.05, unpaired t-test.

Fig. 8.

Chronic exposure to L-Ala solution significantly downregulated oral mRNA transcripts involved in umami taste sensing in chickens. (A) Experimental procedure for chronic exposure of chickens to 0.28 M L-Ala solution or water. After ad libitum exposure to 0.28 M L-Ala or water for 1 week, the palate and duodenum were collected. (B) Relative mRNA levels of T1R1 and T1R3, but not TRPM5, CALHM1, and CALHM3 were significantly downregulated by chronic 0.28 M L-Ala stimulation in the palate. (C) Relative mRNA levels of T1R1, T1R3, TRPM5, CALHM1, and CALHM3 in the duodenum were not significantly different between the chickens stimulated by chronic 0.28 M L-Ala or water ex posure. Values represent mean relative mRNA levels (nor malized to GAPDH)±SE (n=7). # P< 0.1, * P<0.05, and ** P<0.01, unpaired t-test.

Discussion

In the present study, we applied a shorter water-deprivation time (6 h) than in our previous study (maximum 24 h; Yoshida et al., 2018) to minimize the adverse effects of water deprivation. As a longer water deprivation time of 24 h can stabilize the short-time water intake of chicks, the shorter water-deprivation time used in the present study may decrease the stability of water intake volumes. Conversely, LiCl injection decreased L-amino acid solution intake relative to that in response to saline injection within the same days, suggesting that the chicks were conditioned to avoid L-amino acid solutions by LiCl injection, despite slight instability in their water intake volumes. Furthermore, we observed that the preference ratio for L-amino acid solutions was significantly lower in the LiCl-injected groups than in the saline-injected groups. These results suggest that chickens have a gustatory perception of L-amino acids.

The present study showed that chickens can detect L-Ala, L-Ser, and L-Pro by gustatory perception. Since a previous study demonstrated that chicken T1R1/T1R3 is activated by L-Ala and L-Ser, but not by L-Pro (Baldwin et al., 2014), chickens were considered to detect L-amino acids via addi-tional L-amino acid taste receptors, other than the T1R1/T1R3 heterodimer, for at least L-Pro detection. In mice, gustatory neural responses to umami stimuli are not completely diminished in T1R1- or T1R3-knockout mice (Damak et al., 2003; Kusuhara et al., 2013), and the taste cells of T1R3-knockout mice are still activated by umami stimuli (Maruyama et al., 2006). In fact, recent studies suggest that mGluRs are involved in the detection of various L-amino acids in taste cells isolated from T1R3-knockout mice (Choudhuri et al., 2016). Taste cells of mice can also respond to L-amino acids through the calcium sensing receptor (CaSR) (Bystrova et al., 2010). Thus, novel combinations of the proposed or unidentified receptors may be involved in L-amino acid taste detection in mice. Our previous study demonstrated that T1R1 and T1R3 are rarely co-expressed with one another in chicken taste cells, although small populations of taste cells expressing both T1R1 and T1R3 have been found (Yoshida et al., 2021a). Additionally, our previous work suggests that the mRNA of mGluR1, but not mGluR4, is highly expressed in the palate of chickens (Yoshida et al., 2018a). Thus, further analyses of the role of mGluRs and CaSR in chicken L-amino acid detection are needed to fully understand L-amino acid taste sensing systems in chickens.

The activation of umami taste receptors leads to the release of calcium ion from the endoplasmic reticulum, triggering the activation of TRPM5 in mammalian umami taste sensing systems (Zhang et al., 2007). Opening of the TRPM5 channel leads to depolarization of taste cells and neurotransmitter release from the CALHM1/3 channel (Ma et al., 2018). TRPM5 is highly expressed in the chicken palate (Yoshida et al., 2018b), and the present study demonstrates that CALHM1 and CALHM3 are highly expressed in the taste tissues of chickens. Mammalian taste receptor cells, namely type II taste cells, lack synaptic vesicles and proteins related to neurotransmission, such as voltage-gated calcium channels, presynaptic SNARE proteins (i.e., SNAP25), and neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs) (Clapp et al., 2006; DeFazio et al., 2006). Recent studies reveal that type II taste cells use a novel neurotransmission system through the CALHM1/CALHM3 channel-mitochondrial signaling complex (Ma et al., 2018; Romanov et al., 2018). However, we previously showed that a large proportion of chicken taste receptor cells that express T1R3, but not T1R1, also express SNAP25 and NCAM, unlike mammalian type II taste cells (Yoshida et al., 2021b). Therefore, further studies are required to understand whether chicken taste receptor cells use the CALHM1/CALHM3 channel-mitochondrial signaling complex, as shown in mammals.

The present study demonstrates that chronic exposure to L-Ala solution for one week significantly downregulates the oral mRNA levels of T1R1 and T1R3 in chickens, compared with those in the control treatment. Our results suggest that oral umami taste sensing systems are regulated in response to chronic L-amino acid intake in chickens, rather than to acute L-amino acid stimulation. As a high-fat diet has been reported to significantly downregulate the expression of T1R3 mRNA in rat taste buds (Chen et al., 2010), our results suggest that nutritional status may modulate oral taste-sensing systems. Therefore, our study raises the possibility that L-amino acid intake can regulate oral umami taste sensing systems in chickens.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that chickens have a gustatory perception of L-amino acids, and oral umami taste sensing systems can be regulated by L-amino acid intake. However, the present study has some limitations. The entire repertoire of L-amino acids that elicits gustatory perception in chickens is still unknown. Whether chickens prefer L-amino acids in feeds and the roles of L-amino acid taste receptors other than T1R1/T1R3 are also unknown. Therefore, further studies on L-amino acid taste sensing systems in chickens are required. Nevertheless, the present results suggest that L-amino acid taste is important for understanding feeding behaviors in poultry farming.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants to F. Kawabata from JSPS KAKENHI (#21H02338), Y. Yoshida from JSPS KAKENHI (#21K14957), and S. Tabata from JSPS KAKENHI (#18H02330).

Author Contributions

Yuta Yoshida, Shotaro Nishimura, Shoji Tabata and Fuminori Kawabata designed the experiments. Yuta Yoshida, Ryota Tanaka, and Shu Fujishiro conducted experiments. Yuta Yoshida and Fuminori Kawabata wrote the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baldwin MW, Toda Y, Nakagita T, O'Connell MJ, Klasing KC, Misaka T, Edwards SC and Liberles SD. Evolution of sweet taste perception in hummingbirds by transformation of the ancestral umami receptor. Science, 345: 929-933. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bystrova MF, Romanov RA, Rogachevskaja OA, Churbanov GD and Kolesnikov SS. Functional expression of the extracellular-Ca2+-sensing receptor in mouse taste cells. Journal of Cell Science, 123: 972-982. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari N, Landin AM and Roper SD. A metabotropic glutamate receptor variant functions as a taste receptor. Nature Neuroscience, 3: 113-119. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheled-Shoval SL, Behrens M, Meyerhof MW, Niv MY and Uni Z. Perinatal administration of a bitter tastant influences gene expression in chicken palate and duodenum. Poultry Science, 62: 12512-12520. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Yan J, Suo Y, Li J, Wang Q and Lv B. Nutritional status alters saccharin intake and sweet receptor mRNA expression in rat taste buds. Brain Research, 1325: 53-62. 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri SP, Delay RJ and Delay ER. Metabotropic glutamate receptors are involved in the detection of IMP and L-amino acids by mouse taste sensory cells. Neuroscience, 316: 94-108. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp TR, Medler KF, Damak S, Margolskee RF and Kinnamon SC. Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25. BMC Biology, 4: 1-9. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damak S, Rong M, Yasumatsu K, Kokrashvili Z, Varadarajan Z, Zou S, Jiang P, Ninomiya Y and Margolskee RF. Detection of sweet and umami taste in the absence of taste receptor T1r3. Science, 301: 850-853. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio RA, Dvoryanchikov G, Maruyama Y, Kim JW, Pereira E, Roper SD and Chaudhari N. Separate populations of receptor cells and Presynaptic cells in mouse taste buds. Journal of Neuroscience, 26: 3971-3980. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delay ER and Kondoh T. Dried bonito dashi: taste qualities evaluated using conditioned taste aversion methods in wild-type and T1R1 knockout mice. Chemical Senses, 40: 125-140. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganchrow D and Ganchrow JR. Number and distribution of taste buds in the oral cavity of hatchling chicks. Physiology & Behavior, 34: 889-894. 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata F, Murayama K, Yoshida Y, Liang R, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Identification of ligands for chicken transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 channel and chemosensory perception of herbal compounds in chickens. Journal of Poultry Science, 59: 286-290. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata F, Yoshida Y, Inoue Y, Kawabata Y, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Research Note: Behavioral preference and conditioned taste aversion to oleic acid solution in chickens. Poultry Science, 100: 372-376. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo K, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Distribution of taste buds in layer-type chickens: scanning electron microscopic observations. Animal Science Journal, 79: 680-685. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara Y, Yoshida R, Ohkuri T, Yasumatsu K, Voigt A, Hübner S, Maeda K, Boehm U, Meyerhof W and Ninomiya Y. Taste responses in mice lacking taste receptor subunit T1R1. Jour nal of Physiology, 591: 1967-1985. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z, Taruno A, Ohmoto M, Jyotaki M, Lim JC, Miyazaki H, Niisato N, Marunaka Y, Lee RJ, Hoff H, Payne R, Demuro A, Parker I, Mitchell CH, Henao-Mejia J, Tanis JE, Matsumoto I, Tordoff MG and Foskett JK. CALHM3 is essential for rapid ion channeL-mediated purinergic neurotransmission of GPCR-mediated tastes. Neuron, 98: 547-561. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama Y, Pereira E, Margolskee RF, Chaudhari N and Roper SD. Umami responses in mouse taste cells indicate more than one receptor. Journal of Neuroscience, 26: 2227-2234. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romanov RA, Lasher RS, High B, Savidge LE, Lawson A, Rogachevskaja OA, Zhao H, Rogachevsky VV, Bystrova MF, Churbanov GD, Adameyko I, Harkany T, Yang R, Kidd GJ, Marambaud P, Kinnamon JC, Kolesnikov SS and Finger TE. Chemical synapses without synaptic vesicles: purinergic neurotransmission through a CALHM1 channel-mitochondrial signaling complex. Science Signaling, 11: eaao1815. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roper SD and Chaudhari N. Taste buds: cells, signals and synapses. Nature Review Neuroscience, 18: 485-497. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda Y, Nakagita T, Hayakawa T, Okada S, Narukawa M, Imai H, Ishimaru Y and Misaka T. Two distinct determinants of ligand specificity in T1R1/T1R3 (the umami taste receptor). Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288: 36863-36877. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasumatsu K, Manabe T, Yoshida R, Iwatsuki K, Uneyama H, Takahashi I and Ninomiya Y. Involvement of multiple taste receptors in umami taste: analysis of gustatory nerve responses in metabotropic glutamate receptor 4 knockout mice. Journal of Physiology, 593: 1021-1034. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kawabata Y, Kawabata F, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Expressions of multiple umami taste receptors in oral and gastrointestinal tissues, and umami taste synergism in chickens. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 466: 346-349. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kawabata F, Kawabata Y, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Short-term perception of and conditioned taste aversion to umami taste, and oral expression patterns of umami taste receptors in chickens. Physiology & Behavior, 191: 29-36. 2018a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kawabata F, Kawabata Y, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Expression levels of taste-related genes in palate and tongue tip, and involvement of transient receptor potential subfamily M member 5 (TRPM5) in taste sense in chickens. Animal Science Journal, 89: 441-447. 2018b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Wang Z, Tehrani KF, Pendleton EG, Tanaka R, Mortensen LJ, Nishimura S, Tabata S, Liu HX and Kawabata F. Bitter taste receptor T2R7 and umami taste receptor subunit T1R1 are expressed highly in Vimentin-negative taste bud cells of chickens. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 511: 280-286. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kawabata F, Nishimura S and Tabata S. The umami receptor T1R1-T1R3 heterodimer is rarely formed in chickens. Scientific Reports, 11: 1-10. 2021a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Kawabata F, Nishimura S and Tabata S. Overlapping distributions of mammalian types I, II, and III taste cell markers in chicken taste buds. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 570: 162-168. 2021b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhao Z, Margolskee RF and Liman E. The transduction channel TRPM5 is gated by intracellular calcium in taste cells. Journal of Neuroscience, 27: 5777-5786. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ and Zuker CS. The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell, 115: 255-266. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]