Abstract

Hip arthroscopy has been proven to effectively treat labral tears in the setting of femoroacetabular impingement. Anchors used for this treatment have constantly evolved and improved to ensure safety and minimal invasion. However, acetabular drilling and anchor placement are technically challenging due to the concavity of the acetabular articular surface, limited angles for anchor insertion, and finite bone availability in the anterior and posterior column. Inadequate technique can result in protruding anchors, which may lead to full-thickness articular cartilage damage, manifesting in pain, mechanical symptoms, and impaired function. This Technical Note demonstrates arthroscopic removal of protruding anchors and management of the iatrogenic grade IV cartilage damage. In this description, the technical pearls and pitfalls of acetabular anchor placement to treat labral pathology are presented along with the aforementioned technique.

Technique Video

Arthroscopic video presenting an approach to revision hip arthroscopy with removal of problematic anchors in the setting of anchor arthropathy caused by cartilage penetration. Patients with previous hip arthroscopy are assessed clinically in correlation to diagnostic imaging. Magnetic resonance arthrogram is evaluated to determine possible causes of pain. Anchors used to treat labral pathology can be observed to penetrate acetabular cartilage, as well as other sources of articular pathology. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed after standard access to the joint and establishment of the anterolateral (AL), mid-anterior (MA), and distal anterolateral accessory portal (DALA), which allows for evaluation of the lesions and operative planning. Penetrating anchors are removed using the most efficient method to preserve articular cartilage. In this video, a probe is sufficient to mobilize the exposed anchor intra-articularly and an arthroscopic grasper is used to remove it. Cartilage defects may result from penetrating anchors, which may benefit from micro-drilling and biologic injections trans- or postoperatively. Anchor arthropathy, with its devastating effects, can be avoided with a careful anchor placement surgical technique when treating labral pathology.

The importance of the hip labrum in creating a suction seal effect in the hip joint has been demonstrated in previous studies.1,2 Arthroscopic restoration of labral function has been shown to lead to significantly improved short- to long-term patient-reported outcomes, as well as pain reduction and decreased likelihood of conversion to total hip arthroplasty.3,4 However, hip arthroscopy remains a challenging procedure with a steep learning curve; iatrogenic damage to articular surfaces may be caused during many different steps of the procedure, which may lead to a low survivorship rate.5

Suture anchors, consisting of a metal, polyether-ether ketone, bioabsorbable (poly-L-lactic acid), or all-suture anchors, have vastly evolved over the past 2 decades as a method of fixation of the labrum to the acetabular bone. Careful placement of the anchor should be directed in such a way that the anchors remain close to the acetabular rim without penetrating the articular cartilage. However, suture anchors should not be placed too far from the cartilage in such a way that it causes eversion of the labrum.6,7 While considered safe, there have been reports of complications associated with the use of suture anchors.

A mechanical condition caused by a protruding anchor, known as anchor arthropathy, may lead to mechanical erosion of the acetabular and femoral head articular cartilage, or to anchor fragmentation, leading to loose bodies that may potentially cause further chondral injury.8,9 Ultimately, this condition may lead to progressively worsening pain and limited range of motion and activity for the patient, who is typically unresponsive to nonsurgical treatment and will require a revision arthroscopy. This Technical Note presents arthroscopic treatment to remove protruding anchors and manage chondral injury resulting from anchor arthropathy. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. This study was carried out in accordance with relevant regulations of the US Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Details that might disclose the identity of the subjects under study have been omitted. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB ID: 5276).

Surgical Technique (With Video Illustration)

Indication

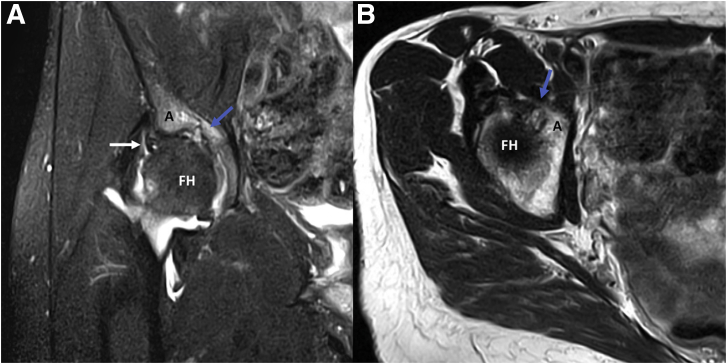

Physical examination includes assessment of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome using the lateral, anterior, and posterior impingement tests.10 Views for radiographic evaluation include the supine and upright anteroposterior pelvic, false profile, and modified Dunn 45°.11 Preoperative magnetic resonance arthrogram is performed to determine labral retearing or other extra and intra-articular defects, presence of loose bodies, and protrusion of anchors to the acetabular cartilage (Fig 1). Nonoperative treatment is conducted and includes measures such as physical therapy, activity modification, rest, and anti-inflammatory medications. Revision hip arthroscopy treatment is recommended after 3 months of failed conservative measures and progression of symptoms.

Fig 1.

(A) Coronal T2 image of a fat-saturated magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA) of the right hip, where a labral tear can be visualized (white arrow). (B) Axial T2 image of a fat-saturated MRA of the right hip. Hyperintense images produced by the protruding anchors can be seen in both views, disrupting articular cartilage of the acetabulum (blue arrow). (A, acetabulum; FH, femoral head.)

Patient Preparation and Positioning

Under general anesthesia, the patient is placed in the supine position on a post-less traction.12 The feet are protected with extra-padding, and the patient is adequately positioned and secured. The operative leg is positioned in neutral rotation and adduction, whereas the contralateral leg is placed at 30° of abduction. The operative table is then fixed at 10 to 15° of Trendelenburg inclination.

Portal Placement

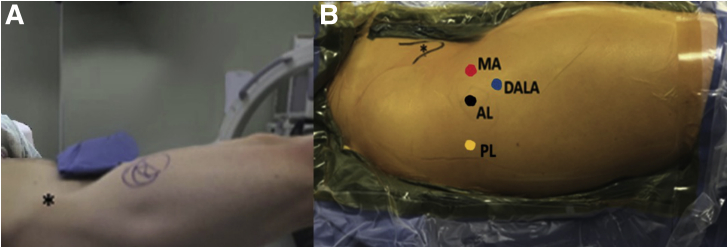

The anterolateral portal is created using fluoroscopic guidance as previously described at the 12-o’clock position.13 The remaining 3 portals, mid-anterior, distal anterolateral accessory, and posterolateral are created under direct visualization.14 Routine portal placement is shown in Figure 2.

Fig 2.

(A) The patient is placed in the modified supine position and the anterior inferior iliac spine is marked (∗). (B) The right hip is shown, with patient’s head to the left and feet to the right. The 4 portals used are identified: anterolateral (AL), mid-anterior (MA), distal anterolateral accessory (DALA), and posterolateral (PL). (This figure was previously published by Sabetian et al. under the terms of https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.)

Diagnostic Arthroscopy and Articular Cartilage Assessment

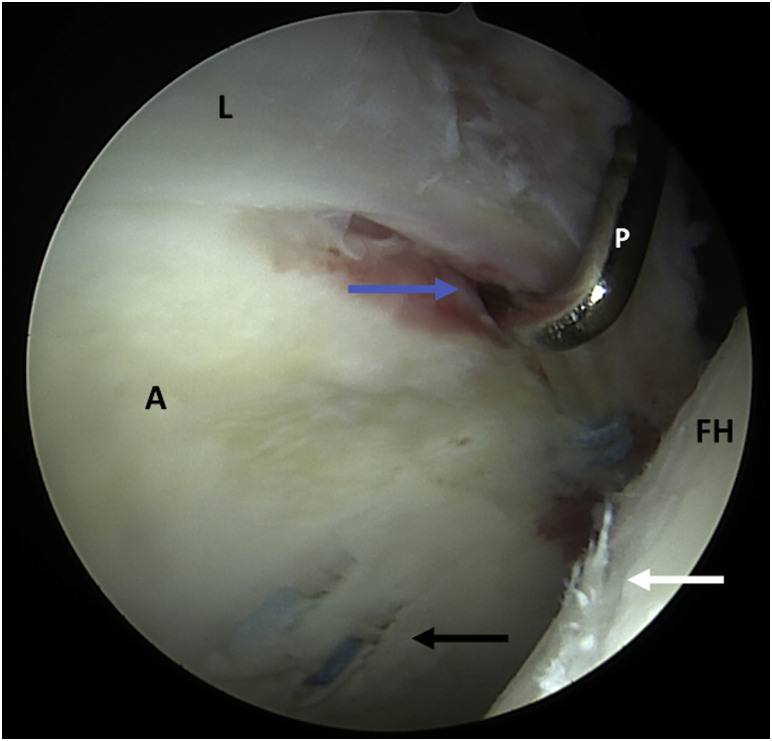

A systematic assessment is performed through a diagnostic arthroscopy to assess the intra-articular cartilage, labrum, and ligamentum teres. Notable procedures performed during the previous surgery are assessed, including the placement and function of suture anchors for labral repair. Acetabular cartilage is assessed with an arthroscopic probe to determine detachment of the chondral surface at the chondrolabral junction, as well as full- and partial-thickness tears in articular cartilage (Fig 3). Outerbridge and acetabular labrum articular disruption classifications are used to grade chondral defects,15,16 which can be caused by protruding anchors in the acetabulum.

Fig 3.

Intraoperative images during a revision diagnostic arthroscopy visualized with a 70° arthroscope from the anterolateral (AL) portal, assessing the articular surface of the acetabulum (A) and femoral head (FH), as well as the labrum (L). The labrum is assessed with a probe (P) introduced through the mid-anterior portal, finding a combined Seldes 1 and 2 tear (blue arrow). Anchors used to repair the labrum on previous surgery are visualized protruding through the acetabular surface (black arrow), which results in chondral damage to the femoral head is as signaled with the white arrow.

Other pathologic conditions, such as retearing of the labrum, residual acetabular overcoverage and femoral cam morphology, intra-articular loose bodies, subspine impingement, acetabular notch osteophytes, and instability, also are treated arthroscopically during the procedure.

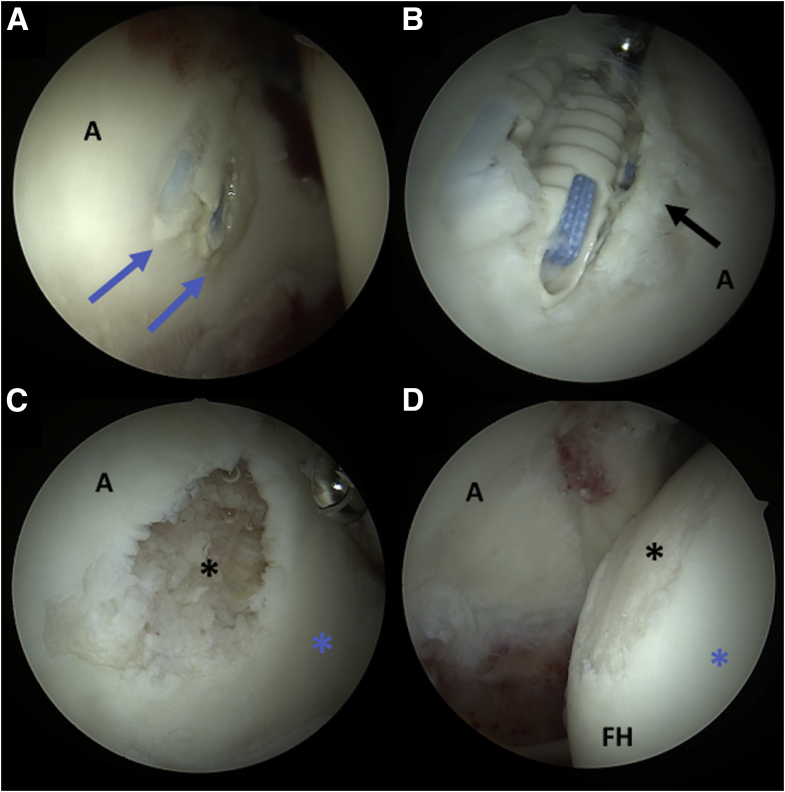

Identification and Removal of Protruding Anchors

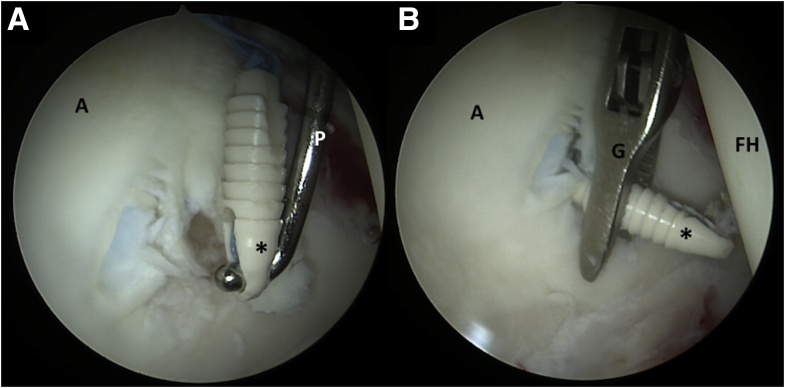

All unviable and unstable cartilage around the edges of the lesion is removed with the use of an arthroscopic shaver. This exposes the protruding anchors and the resulting iatrogenic cartilage injury (Fig 4 A-D). Treatment options for removal of anchor-induced arthropathy are shown on Table 1. In the presented case, the anchors were mobilized and completely exposed through the defect with the use of an arthroscopic probe, and an alligator grasper was then used to perform an en bloc removal (Fig 5 A and B). A ring curette was used to scrape the loose edges of the cartilage and to create perpendicular borders around the lesion (Video 1). Arthroscopic lavage of the hip to remove debris that could cause synovitis or third body wear is then performed.

Fig 4.

Intraoperative images during a revision diagnostic arthroscopy with the patient in a supine position, visualized through the anterolateral (AL) portal. (A) Anchors used during previous surgery to repair the labrum are evidenced protruding and causing anchor arthropathy (blue arrows). (B) Arthroscopic image showing articular cartilage damage caused by the protruding anchors are further uncovered with the use of a probe (black arrow). (C) Extensive chondral damage through subchondral bone is evidenced after removal of the protruding anchors (black star); intact acetabular cartilage is marked with a blue star. (D) Damage caused by protruding anchors has extended to the articular surface of the femoral head (identified with a black star), surrounded by undamaged cartilage (blue star). (A, acetabulum; FH, femoral head.)

Table 1.

Treatment Options of Anchor-Induced Arthropathy

No visible cartilage penetration

|

Fig 5.

Intraoperative images during removal of protruding anchors visualized with a 70° arthroscope from the anterolateral (AL) portal. (B) An arthroscopic probe (P) is introduced through the midanterior portal and used to expose and mobilize anchors used for labral repair in a previous procedure, which have protruded through articular cartilage (black star). (B) An arthroscopic grasper (G) is used to complete the en bloc removal of the anchors. (A, acetabulum; FH, femoral head.)

Micro-Drilling

Typically, Outerbridge type III and IV lesions are treated with a micro-drilling procedure.17 Indications and contraindications for this procedure are found in Table 2. To perform this, a micro-drilling pick or a 70° curved drill guide with a flexible drill (Arthrex, Naples, FL) is introduced into the joint from the portal offering a perpendicular trajectory to the lesion (mid-anterior or distal anterolateral accessory portal). The drill bit is assembled to reach the desired depth and set on forward speed to reduce the risk of breakage. It is recommended to begin from the periphery of the defect and work towards the center, placing holes 3 to 4 mm apart to avoid subchondral plate fractures. After drilling, the shaver is used to remove debris that may have accumulated in the joint during drilling. Fluid irrigation is ceased to ensure bleeding from each micro-drilled hole.

Table 2.

Surgical Indications for Micro-drilling

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Rehabilitation

Following surgery, rehabilitation includes 2 weeks of bracing with limiting flexion range of motion to 90°. In addition, patients are limited to 20 lbs of weight-bearing on the operative extremity for 6 weeks. Patients begin physical therapy the day after surgery and started with passive range of motion using a stationary bike. They then progress to full strength activity over a 3- to 4-month period.

Discussion

Acetabular anchor placement can lead to iatrogenic complications when repairing or reconstructing the labrum. A misdirected anchor can cause damage by penetrating the articular cartilage during drilling or anchor placement. It may also internally detach a segment of the articular cartilage without piercing entirely through the articular cartilage (bubbling). Furthermore, if the anchor is exposed and becomes free, it may act as a loose body that potentially could cause chondral injury throughout the articular surface. Acetabular cartilage lesions may lead to femoral head lesions, leading to advanced stages of osteoarthritis expeditiously. Pearls to avoid cartilage damage during anchor placement are found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pearls to Avoid Cartilage Damage During Anchor Placement

| Drill through the DALA portal |

| Adequate rim preparation using wand and burr |

| Use flexible drill bit |

| Visualize articular surface during drilling and anchor placement |

| Sound the drilled hole with a flexible wire to palpate distal cortex |

| Use small-diameter, suture anchors |

DALA, distal anterolateral accessory.

There are different treatment options to remove anchors, which depend on the type of anchor—hard (threaded or barbed) or soft—and the amount of protrusion. In any case, the goal of the removal is to preserve as much cartilage as possible. Hard, threaded anchors may be removed by a reverse screwing motion in the opposite direction of its insertion. Hard, barbed anchors may be removed through their insertion point using an arthroscopic grasper. If the anchors may not be removed retrogradely, they may be removed through anterograde advancement for its removal in the central compartment. If difficult to remove in either direction, one option is to burr down the exposed surface of the anchor, which carries the risk of compromising the labral fixation or provoking an intra-articular loose implant. Finally, if the anchor is protruding completely, it may be removed en bloc with the use of an arthroscopic grasper; however, this may generate a large chondral defect.18,19 Anchor arthropathy may have devastating effects in the post-operative recovery, as well as the short- to long-term survivorship of the hip joint. While the learning curve in hip arthroscopy may be steep, a careful surgical technique should avoid penetrating anchors at all costs, in the pursuit of the best possible outcome in the patients’ treatment.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: B.G.D. reports grants and other from the American Orthopaedic Association, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Amplitude, personal fees and nonfinancial support from Arthrex, DJO Global, and Medacta; grants, personal fees, nonfinancial support, and other from Stryker, grants from Breg, personal fees from Orthomedica, grants and nonfinancial support from Medwest Associates, grants from ATI Physical Therapy, personal fees and nonfinancial support from St. Alexius Medical Center, grants from Ossur; and nonfinancial support from Zimmer Biomet, DePuy Synthes Sales, Medtronic, Prime Surgical, and Trice Medical, outside the submitted work. Moreover, B.G.D. has patents issued and receives royalties for the following: method and instrumentation for acetabular labrum reconstruction (8920497), licensed by Arthrex; adjustable multi-component hip orthosis (8708941), licensed by Orthomerica and DJO Global; and knotless suture anchors and methods of suture repair (9737292), licensed by Arthrex. Finally, B.G.D. is a board member of the American Hip Institute Research Foundation, AANA Learning Center Committee, Journal of Hip Preservation Surgery, and Arthroscopy and has had ownership interests in the American Hip Institute, Hinsdale Orthopedic Associates, Hinsdale Orthopedic Imaging, SCD#3, North Shore Surgical Suites, and Munster Specialty Surgery Center. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

This study was performed at the American Hip Institute Research Foundation.

Supplementary Data

Arthroscopic video presenting an approach to revision hip arthroscopy with removal of problematic anchors in the setting of anchor arthropathy caused by cartilage penetration. Patients with previous hip arthroscopy are assessed clinically in correlation to diagnostic imaging. Magnetic resonance arthrogram is evaluated to determine possible causes of pain. Anchors used to treat labral pathology can be observed to penetrate acetabular cartilage, as well as other sources of articular pathology. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed after standard access to the joint and establishment of the anterolateral (AL), mid-anterior (MA), and distal anterolateral accessory portal (DALA), which allows for evaluation of the lesions and operative planning. Penetrating anchors are removed using the most efficient method to preserve articular cartilage. In this video, a probe is sufficient to mobilize the exposed anchor intra-articularly and an arthroscopic grasper is used to remove it. Cartilage defects may result from penetrating anchors, which may benefit from micro-drilling and biologic injections trans- or postoperatively. Anchor arthropathy, with its devastating effects, can be avoided with a careful anchor placement surgical technique when treating labral pathology.

References

- 1.Ferguson S.J., Bryant J.T., Ganz R., Ito K. The influence of the acetabular labrum on hip joint cartilage consolidation: a poroelastic finite element model. J Biomech. 2000;33:953–960. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nepple J.J., Philippon M.J., Campbell K.J., et al. The hip fluid seal—Part II: The effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection, and reconstruction on hip stability to distraction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22:730–736. doi: 10.1007/s00167-014-2875-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maldonado D.R., Kyin C., Chen S.L., et al. In search of labral restoration function with hip arthroscopy: outcomes of hip labral reconstruction versus labral repair: A systematic review. HIP Int. 2021;31:704–713. doi: 10.1177/1120700020965162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyin C., Maldonado D.R., Go C.C., Shapira J., Lall A.C., Domb B.G. Mid- to long-term outcomes of hip arthroscopy: A systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2021;37:1011–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schüttler K.F., Schramm R., El-Zayat B.F., Schofer M.D., Efe T., Heyse T.J. The effect of surgeon’s learning curve: Complications and outcome after hip arthroscopy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138:1415–1421. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly B.T., Weiland D.E., Schenker M.L., Philippon M.J. Arthroscopic labral repair in the hip: Surgical technique and review of the literature. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1496–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Philippon M.J., Schroder e Souza B.G., Briggs K.K. Labrum: Resection, repair and reconstruction sports medicine and arthroscopy review. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2010;18:76–82. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181de376e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhee K.J., Kim K.C., Shin H.D., Kim Y.M. Revision using modified transglenoid reconstruction in recurred glenohumeral instability combined with anchor-induced arthropathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15:1494–1498. doi: 10.1007/s00167-007-0329-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ríos D., Martetschlager F., Millett P.J. Comprehensive arthroscopic management of shoulder osteoarthritis. Acta Ortop Mex. 2012;26:310–315. [in Spanish] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin H.D., Kelly B.T., Leunig M., et al. The pattern and technique in the clinical evaluation of the adult hip: The common physical examination tests of hip specialists. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clohisy J.C., Carlisle J.C., Beaulé P.E., et al. A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 4):47–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabetian P.W., Owens J.S., Maldonado D.R., et al. Circumferential and segmental arthroscopic labral reconstruction of the hip utilizing the knotless pull-through technique with all-suture anchors. Arthrosc Tech. 2021;10:e2245–e2251. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2021.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maldonado D.R., Chen J.W., Walker-Santiago R., et al. Forget the greater trochanter! Hip joint access with the 12 o’clock portal in hip arthroscopy. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8:e575–e584. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perets I., Hartigan D.E., Chaharbakhshi E.O., Walsh J.P., Close M.R., Domb B.G. Circumferential labral reconstruction using the knotless pull-through technique-surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2017;6:e695–e698. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia S., Nowak D.D., Briggs K.K., Patterson D.C., Philippon M.J. Outerbridge grade IV cartilage lesions in the hip identified at arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:814–819. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suarez-Ahedo C., Gui C., Rabe S.M., Chandrasekaran S., Lodhia P., Domb B.G. Acetabular chondral lesions in hip arthroscopy: Relationships between grade, topography, and demographics. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:2501–2506. doi: 10.1177/0363546517708192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maldonado D.R., Chen J.W., Lall A.C., et al. Microfracture in hip arthroscopy. Keep it simple. Arthrosc Tech. 2019;8:e1063–e1067. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsuda D.K., Bharam S., White B.J., Matsuda N.A., Safran M. Anchor-induced chondral damage in the hip. J Hip Preserv Surg. 2015;2:56–64. doi: 10.1093/jhps/hnv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grutter P.W., McFarland E.G., Zikria B.A., Dai Z., Petersen S.A. Techniques for suture anchor removal in shoulder surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1706–1710. doi: 10.1177/0363546510372794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Arthroscopic video presenting an approach to revision hip arthroscopy with removal of problematic anchors in the setting of anchor arthropathy caused by cartilage penetration. Patients with previous hip arthroscopy are assessed clinically in correlation to diagnostic imaging. Magnetic resonance arthrogram is evaluated to determine possible causes of pain. Anchors used to treat labral pathology can be observed to penetrate acetabular cartilage, as well as other sources of articular pathology. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed after standard access to the joint and establishment of the anterolateral (AL), mid-anterior (MA), and distal anterolateral accessory portal (DALA), which allows for evaluation of the lesions and operative planning. Penetrating anchors are removed using the most efficient method to preserve articular cartilage. In this video, a probe is sufficient to mobilize the exposed anchor intra-articularly and an arthroscopic grasper is used to remove it. Cartilage defects may result from penetrating anchors, which may benefit from micro-drilling and biologic injections trans- or postoperatively. Anchor arthropathy, with its devastating effects, can be avoided with a careful anchor placement surgical technique when treating labral pathology.

Arthroscopic video presenting an approach to revision hip arthroscopy with removal of problematic anchors in the setting of anchor arthropathy caused by cartilage penetration. Patients with previous hip arthroscopy are assessed clinically in correlation to diagnostic imaging. Magnetic resonance arthrogram is evaluated to determine possible causes of pain. Anchors used to treat labral pathology can be observed to penetrate acetabular cartilage, as well as other sources of articular pathology. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed after standard access to the joint and establishment of the anterolateral (AL), mid-anterior (MA), and distal anterolateral accessory portal (DALA), which allows for evaluation of the lesions and operative planning. Penetrating anchors are removed using the most efficient method to preserve articular cartilage. In this video, a probe is sufficient to mobilize the exposed anchor intra-articularly and an arthroscopic grasper is used to remove it. Cartilage defects may result from penetrating anchors, which may benefit from micro-drilling and biologic injections trans- or postoperatively. Anchor arthropathy, with its devastating effects, can be avoided with a careful anchor placement surgical technique when treating labral pathology.