Abstract

Background

Imatinib is an active agent for some patients with melanoma harbouring c-KIT alterations. However, the genetic and clinical features that correlate with imatinib sensitivity are not well-defined.

Methods

We retrospectively evaluated 38 KIT-altered melanoma patients from five medical centres who received imatinib, and pooled data from prospective studies of imatinib in 92 KIT-altered melanoma patients. Baseline patient and disease characteristics, and clinical outcomes were assessed.

Results

In the pooled analysis (N = 130), alterations in exons 11/13 had the highest response rates (38% and 33%); L576P (N = 23) and K642E (N = 12) mutations had ORR of 52% and 42%, respectively. ORR was 38% (mucosal), 25% (acral), and 8% (unknown-primary). PFS appeared longer in exon 11/13 vs. exon 17 alterations (median 4.3 and 4.5 vs. 1.1 months; p = 0.19), with similar superiority in OS (median 19.7 and 15.4 vs. 12.1 months; p = 0.20). By histology, median PFS was 4.5 months (mucosal), 2.7 (acral), and 5.0 (unknown-primary) [p = 0.36]. Median OS was 18.0 months (mucosal), 21.8 (acral), 11.5 (unknown-primary) [p = 0.26]. In multivariate analyses, mucosal melanoma was associated with higher PFS and exon 17 mutations were associated with reduced PFS.

Conclusion

This multicenter study highlights KIT-alterations sensitive to imatinib and augments evidence for imatinib in subsets of KIT-altered melanoma.

Subject terms: Melanoma, Mutation, Cancer genetics

Introduction

Although the incidence of melanoma has increased over the past decade, mortality has declined with advances in systemic therapies [1]. The identification of molecular alterations amenable to targeted therapies has transformed the treatment approaches in melanoma. c-KIT, a type III transmembrane tyrosine kinase, is an established albeit uncommon molecular target in melanoma with mutations found in acral, mucosal, and skin with chronic sun damage [1]. Given the critical role of c-KIT in cellular differentiation and proliferation across several tumour subtypes, small molecule inhibitors targeting c-KIT in metastatic melanoma have been investigated [2–4].

Imatinib mesylate is a small molecule inhibitor of c-KIT that was first studied in the setting of patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia and gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) and subsequently in several phase II trials in melanomas with KIT mutations and amplifications [2–4]. Findings from these studies suggested that a subset of tumours harbouring KIT mutations (although generally not amplifications) could experience dramatic benefit, but responses were quite heterogeneous [4]. Based on studies of imatinib in GIST, alterations in exons 9 and 11 would be expected to be more sensitive to imatinib than alterations in exons 17 and 18 in melanoma; however, this has not yet been definitively shown [5]. There remains a need to identify the genetic and clinical markers of benefit, to better select patients for imatinib therapy.

The rarity of KIT mutations in melanoma has posed challenges in further investigating the sensitivity of individual mutations to KIT inhibition. Alterations in KIT occur in only 1–7% of melanoma overall [6–9]; however they are more frequently observed in the less common subtypes of melanoma, including mucosal melanomas (10–20%), acral melanomas (10–20%), as well as melanomas arising from chronically sun-damaged skin (1–2%) [10–13]. Another challenge of studying KIT mutations arises from the wide distribution of mutations across exons 9, 11, 13, 17, and 18 [14]. Moreover, in contrast to GIST, where most KIT alterations are deletions or insertions in the gene, in melanoma, most KIT mutations are missense mutations and have a diverse exon distribution [15]. Thus, the activity of imatinib and other KIT inhibitors for many individual KIT mutations in melanoma, and their interaction with histologic subtype remains poorly defined.

In this retrospective cohort study, we assessed patients with KIT-mutated melanomas from five academic centres in the USA and Australia treated with imatinib. To augment this analysis, we obtained publicly available records from prospective studies of imatinib in patients with advanced melanoma and KIT mutations. We analysed the association of KIT mutations and clinical/pathologic features associated with benefit from imatinib.

Methods

Patients

After institutional review board approval, deidentified medical data was collected from 5 participating institutions in the United States and Australia. Patients whose tumours harboured a KIT alteration and received 1 or more doses of imatinib mesylate for treatment of advanced melanoma were included. Patients with exclusively KIT amplifications (without concurrent KIT mutations) were not included. To provide additional power to identify differences in histologic and mutation subtypes, we included publicly available individual patient-level data from prospective clinical trials [2–4].

Study design

Baseline patient demographics (gender, age, race, ethnicity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] performance status, melanoma subtype, site of primary, pathologic stage, prior treatments, brain metastasis, serum lactate dehydrogenase level), mutational status (KIT mutation, KIT amplification, concurrent BRAF/NRAS mutation, other mutations, tumour mutational burden) and treatment details (dose, duration, and reason for discontinuation) were recorded. Metastatic staging adhered to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) eighth edition. When available, these data were also collected from publicly available studies of imatinib as well. The primary objective of this study was to assess the association between mutation status and response to therapy per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours version 1.1 (RECIST 1.1). Secondary objectives included overall survival, defined as the time from the initiation of therapy to the time of death from any cause, and progression-free survival, defined as the time from initiation of therapy to progression of disease using RECIST 1.1.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were summarised with descriptive statistics. Response rate between groups was reported with 95% confidence intervals. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate OS and PFS and the log rank test was used to compare groups. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to assess the association between specific KIT alterations and primary site with PFS and OS. The software used for analysis was R version 4.1.1 (2021-08-10).

Results

Of 38 patients evaluated from a multi-institutional database, most were female (61%) with a median age of 67 (range 39–93) (Table 1). Most patients were non-Hispanic. Mucosal melanoma was the most common subtype represented (N = 25, 66%), followed by acral melanoma (N = 6, 16%) and unknown-primary melanoma (N = 7, 18.4%). Among all patients, median LDH was 214.5 (range 141-2686). At initiation of imatinib, 31 patients (82%) had stage IV disease and 11 patients (28.9%) had brain metastases present. Most patients had a baseline ECOG of 0 (38%) or 1 (45%). All patients except one had received either one (N = 23, 61%) or ≥ two (N = 14, 37%) prior systemic regimens.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of patients.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of patients (n = 38) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 23 (61) |

| Male | 15 (40) | |

| Age, median (range) | 67 (39–93) | |

| Race | White | 26 (68) |

| Black | 2 (5) | |

| Asian | 2 (5) | |

| Unknown | 7 (18) | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 2 (5) |

| Non-hispanic | 31 (82) | |

| Unknown | 5 (13) | |

| Clinical melanoma subtype | Mucosal | 25 (66) |

| Acral | 6 (16) | |

| Cutaneous | 4 (11) | |

| Unknown | 3 (8) | |

| Elevated LDH, n = 26 | 13 (50) | |

| ECOG performance status | 0 | 14 (38) |

| 1 | 17 (45) | |

| 2 | 7 (18) | |

| Stage IV | 31 (82) | |

| Brain metastasis present | 11 (29) | |

| Prior systemic regimens | 0 | 1 (3) |

| 1 | 23 (61) | |

| ≥2 | 14 (37) | |

| Prior immunotherapy | Anti-PD-1 monotherapy | 15 (39) |

| Anti-PD-1/CTLA-4 combination | 18 (47) | |

All patients had a somatic KIT alteration (specifically mutation, focal deletion, or duplication), but no patients had only KIT amplification without mutation. Mutations were distributed across exons 11 (N = 28), 13 (N = 5), and 17 (N = 6) (Supplementary Table 1). Twelve patients (32%) had a L576P mutation (exon 11), four patients (11%) had a K642E mutation (exon 13), four patients (11%) had a D579 deletion (exon 11), two patients (5%) had a D816Y mutation (exon 17), and two patients (5%) had a D820Y mutation (exon 17); all other alterations (N = 11) were observed only once. One patient had two mutations (D820Y, K558E). Three patients had concurrent non-V600 BRAF mutations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of alterations identified in KIT, BRAF, and NRAS.

| Number of patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT | ||||

| Melanoma subtype | Mutation | Amplification | BRAF mutation | NRAS mutation |

| Acral (n = 6) | 6 | 1 (n = 4) | 0 (n = 5) | 0 (n = 5) |

| Mucosal (n = 25) | 25 | 12 (n = 24) | 3 (n = 20) | 1 (n = 20) |

| CSD (n = 4) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 (n = 3) |

| Total | 35 | 13 | 3 | 1 |

Note: n specified when there is missing data.

BRAF mutations (n = 3; N581I, N581S, D594E): 100% response rate, 2 CR (3/3).

NRAS mutation (n = 1; Q61K): 0% response rate, 100% DCR.

Response results for our cohort of patients are described in Supplementary Table 1. Patients with mutations in exons 11 and 13 had similar response rates of 43% and 40%. Of note, no patients with mutations in exon 17 had response or disease control. The highest response rate by histologic subtype was observed for mucosal melanoma (44%) followed by acral melanoma (33%) and unknown-primary melanoma (14%). Of the 11 patients with brain metastasis, 7 were evaluable for intracranial response (2 patients did not have follow up MRI and 2 patients were not started on imatinib at the time of brain metastasis). 1 patient had an intracranial tumour shrinkage to imatinib (though lacking a RECIST-defined response and lacking clinical improvement) while the other 6 patients had PD.

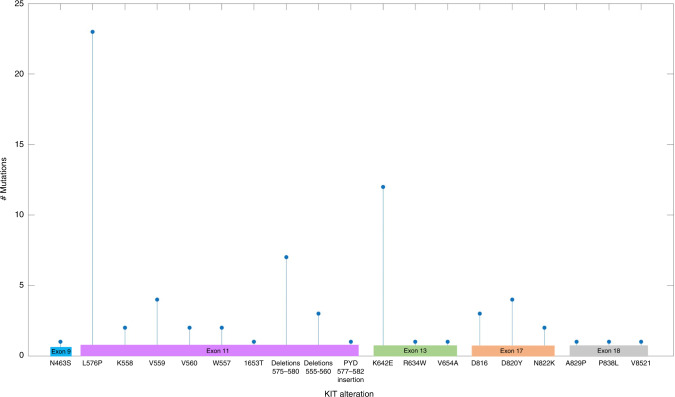

In addition to our cohort of patients, data from three single-arm, open-label phase II trials investigating imatinib in KIT-mutated melanoma were pooled with this study for analysis (Fig. 1) [2–4]. These studies comprised 92 patients treated with imatinib, and had variable degrees of patient-level data available (Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Distribution of KIT alterations.

In this combined cohort, patients with mutations in exons 11 and 13 had the highest response (38% and 33%) and disease control rates (61% and 67%), whereas alterations in exons 9, 17, and 18 were associated with very low response (0%, 7%, and 11%, respectively) and disease control rates (50%, 29%, and 33%, respectively) (Table 3). As previously described, patients with exclusively KIT amplifications and no KIT mutations demonstrated poor response rates (6%). However, patients with concurrent KIT mutation and amplifications had similar response rates of 42% (amplification present) and 30% (amplification absent) and disease control rates of 65% (amplification present) and 53% (amplification absent). When assessing response by histologic subtype, patients with mucosal melanoma demonstrated the greatest response rate (38%), followed by acral melanoma (25%) and unknown-primary melanoma (8%). Mutations in L576P and K642E were the most frequently observed (N = 23, N = 12) and were associated with higher response (52% and 42%) and disease control rates (65% and 92%). Focal deletions and insertions in surrounding regions (e.g., amino acids 575–582, or 555–560) were also associated with reasonable clinical benefit (response in 4 of 11 patients, clinical benefit in 8 of 11). Notably, all 3 patients with concurrent BRAF mutations (N581I, N581S, and D594E, respectively) all responded, with two of the patients exhibiting durable complete responses.

Table 3.

Response by KIT mutations, exons, and melanoma subtype in pooled data analysis.

| Number of patients | Response rate (%) | Disease control rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KIT mutation | A829P | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 100 (1/1) |

| D816a | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| D820Y | 4 | 25 (1/4) | 25 (1/4) | |

| L576P | 23 | 52 (12/23) | 65 (15/23) | |

| K642E | 12 | 42 (5/12) | 92 (11/12) | |

| K558a | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| N822K | 2 | 0 | 50 (1/2) | |

| N463S | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| P838L | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 100 (1/1) | |

| R634W | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| V559a | 4 | 25 (1/4) | 75 (3/4) | |

| V560a | 2 | 100 (2/2) | 100 (2/2) | |

| V654A | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| V8521 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| W557a | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1653T | 1 | 0 | 100 (1/1) | |

| Deletions in amino acids 575-580a | 7 | 29 (2/7) | 57 (4/7) | |

| Deletions in amino acids 555–560a | 3 | 33 (1/3) | 100 (3/3) | |

| PYD577-582 insertion | 1 | 100 (1/1) | 100 (1/1) | |

| Exon | Exon 9 | 4 | 0 | 50 |

| Exon 11 | 61b | 38 (23/61) | 61 (37/61) | |

| Exon 13 | 24 | 33 (8/24) | 67 (16/24) | |

| Exon 17 | 14b | 7 (1/14) | 29 (4/14) | |

| Exon 18 | 9 | 11 (1/9) | 33 (3/9) | |

| Amplification only | 18 | 6 (1/18) | 33 (6/18) | |

| Amplification + mutationc | Amplification present | 31 | 42 (13/31) | 65 (20/31) |

| Amplification absent | 30 | 30 (9/30) | 53 (16/30) | |

| Melanoma subtype | Acral | 20 | 25 (5/20) | 55 (11/20) |

| Mucosal | 55 | 38 (21/55) | 60 (33/55) | |

| Cutaneous | 9 | 11 (1/9) | 56 (5/9) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 0 | 33 (1/3) | |

aD816: D816Y (2), D816V (1).

L576P: Includes one patient with L576P_H580 duplication.

K558: K558N (1), K558E (1).

V559: V559A (2), V559G (1), V559C (1).

V560: V560E (1), V560D (1).

W557: W557G (1), W557R (1).

Deletions in amino acids 575–580: D579 deletion (4), P577 deletion (1), 579_579 deletion (1), P577_D579 deletion (1).

Deletions in amino acids 555–560: V559_E561 deletion (1), D579 deletion (1), WKVE557-560 deletion (1).

bIncludes 1 patient with exon 11 and exon 17 mutation.

cDoes not include 10 patients with unknown amplification status and 18 with amplification without mutation.

We then assessed PFS and OS by exon, histologic subtype, and AJCC staging using data combined from our cohort of patients and the single trial for which survival data were available (Fig. 2) [4]. The median PFS of patients with exon 11 or 13 mutations appeared numerically longer than that of exon 17 mutations (4.3 months and 4.5 months vs. 1.1 months), although no statistical significance was found (p = 0.19). Similarly, OS for exon 11 or 13 mutations appeared longer than for exon 17 mutations (median 19.7 months and 15.4 months vs. 12.1 months), but there was no statistical significance (p = 0.20). When assessing by histology, median PFS was 2.7 (acral), 5.0 (unknown-primary), and 4.5 months (mucosal) [p = 0.36]. Median OS was 21.8 (acral) vs. 11.5 (unknown-primary) vs. 18.0 months (mucosal) [p = 0.26]. With regard to stage, median PFS was 3.9 (III–IV M1b) vs. 3.6 months (IV M1c/d) and median OS was 14.0 (III–IV M1b) vs. 11.3 months (IV M1c/d).

Fig. 2. Clinical outcomes in all patients and stratified by histology and exon.

a Progression-free survival for all patients. b Progression-free survival stratified by histology. c Progression-free survival stratified by exon. d Overall survival for all patients. e Overall survival stratified by histology. f Overall survival stratified by exon.

Finally, we attempted to isolate variables independently associated with PFS and OS (Table 4). In our model, variables of interest included histologic subtype, AJCC staging (III–IV M1b or IV M1c/d), and exon. Mucosal melanoma (hazard ratio [HR], 0.454; 95% CI, 0.207-0.997 [p = 0.049]) was found to be independently associated with improved PFS, while mutations at exon 17 (hazard ratio [HR], 2.603; 95% CI, 1.041-6.510 [p = 0.041]) were found to be associated with lower PFS compared to mutations at other exons. There were no statistically significant differences with regard to PFS when comparing III–IV M1b disease vs. IV M1c/d disease. With regards to OS, there were no variables of interest that were statistically significant.

Table 4.

HRs of variables from multivariate analysis.

| Variable | HR for PFS (95% CI) | p | HR for OS (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma subtype | Cutaneous | 0.810 (0.235–2.793) | 0.739 | 3.182 (0.862–11.749) | 0.082 |

| Mucosal | 0.454 (0.207–0.997) | 0.049 | 1.406 (0.587–3.367) | 0.444 | |

| Unknown | 0.226 (0.050–1.017) | 0.053 | 1.145 (0.189–6.952) | 0.883 | |

| Stage IV M1c/d | 1.556 (0.818–2.960) | 0.178 | 1.636 (0.838–3.194) | 0.149 | |

| Exon | Exon 13 | 2.133 (0.860–5.287) | 0.102 | 1.153 (0.397–3.342) | 0.794 |

| Exon 17 | 2.603 (1.041–6.510) | 0.041 | 2.057 (0.730–5.796) | 0.173 | |

| Amplification only | 1.644 (0.782–3.455) | 0.190 | 2.084 (0.906–4.796) | 0.084 | |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this pooled analysis of patient-level data from clinical trials and retrospective, “real-world” experience is the largest study to date assessing outcomes to imatinib in patients with KIT-mutated melanoma. Results demonstrated that response rates to imatinib were highly variable by KIT mutation and subtype. Higher response rates were observed for patients that harboured L576P and K642E mutations, as well as for patients with mucosal melanoma. Seemingly prolonged PFS and OS was observed for alterations in exons 11 and 13, although there was no statistical significance. In multivariate analysis, we identified mucosal melanoma to be associated with higher PFS and mutations in exon 17 to be associated with lower PFS.

KIT mutations in exon 11, particularly L576P mutations, were the most prevalent in our study population and were associated with higher response rates. Similarly, KIT mutations in exon 11 are the most common mutation in GISTs and have demonstrated significantly higher response rates than mutations in all other exons [16]. Experience with imatinib in GIST with exon 17 and 18 mutations is limited due to the rarity of those mutations. In our study, mutations in exons 17 and 18 were associated with lower response rates compared to exons 11 and 13. Additionally, there were several mutations in our study (each N = 1) that have not been well described in the literature, including R634W, K558N, K558E W557G, and V560E. The effects of these very rare mutations on KIT protein function, as well as oncogenesis, are not well understood. Notably, all patients with these mutations, with the exception of V560E, had primary progressive disease, which emphasises the heterogeneity of response across mutations. However, the small numbers do not provide enough data for definitive conclusions for these uncommon mutations.

Targeting KIT in melanoma remains an important therapeutic strategy for this uncommon genetic subtype. There are several KIT inhibitors, in addition to imatinib, that have been investigated in patients with KIT-mutated melanomas. Nilotinib is a small molecular inhibitor of KIT that has demonstrated comparable efficacy to imatinib. A recent meta-analysis showed the highest ORR (20%; 95% CI, 14–26%) for nilotinib when compared with dasatinib, and sunitinib [17], although broadly similar to imatinib. Similarly, a phase II trial of nilotinib in patients with advanced KIT-mutated melanoma showed ORRs similar to those of imatinib, highlighting nilotinib as a potential option for patients with prior imatinib resistance or intolerance (albeit with very modest activity) [18]. Additionally, there are several new agents that are being actively explored for targeting KIT. A recent phase I study of ripretinib, a switch-control tyrosine kinase inhibitor of KIT and PDGFRA, in patients with KIT-altered melanoma demonstrated some efficacy with an ORR of 23% and median PFS of 7.3 months [19]. Moreover, there are studies investigating combination therapy with KIT inhibition and immunotherapy. Previous studies have demonstrated that KIT inhibitors increase T-cell activation, which provides a plausible basis for an increased anti-tumour response to checkpoint inhibitors when used in combination with KIT inhibition [20, 21]. Co-targeting of KIT and a downstream pathway may serve as a viable approach as well.

Notably, in our study, there were three patients with concurrent non-V600 BRAF mutations, of which two of those patients demonstrated a complete response. This finding supports previous preclinical work demonstrating that melanomas with class 3 BRAF mutations and KIT alterations are uniquely sensitive to tyrosine kinase inhibitors [22]. It appears likely that these class 3 (often “kinase-dead”) mutations amplify signalling generated by mutations in genes encoding upstream growth factors, thus potentially rendering these tumours more sensitive to KIT inhibition. KIT, NRAS, and BRAF mutations rarely overlap, likely due to an epistatic relationship, which may make it difficult to investigate these mutations concurrently in larger sample size [23]. Nevertheless, these co-occurring mutations do not seem to preclude benefit from imatinib.

There are several limitations to this study, including its small sample size. However, due to the rarity of KIT alterations in melanoma, it is the largest study of its kind and it is unlikely that further prospective studies of imatinib in melanoma will be performed. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the study poses limitations. The radiologic data was assessed retrospectively to determine response to treatment, rather than in a controlled, prospective setting. Moreover, some of the trial data was assessed using RECIST v1.0 while data for our cohort was assessed using RECIST v1.1. Lastly, while the inclusion of data from previous phase II trials allowed us to increase our sample size, more limited data was available for these patients (including subsequent therapies), creating a less homogenised dataset.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that imatinib remains a potential treatment option in select patients with KIT-altered melanoma, including in those with a concomitant Class 3 BRAF mutation, who have previously been treated with anti-PD-1-based therapy. Further larger-scale work to pool data for specific rare KIT alterations that are amenable to targeted therapy should be pursued.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

DBJ receives funding from the Susan and Luke Simons Melanoma Directorship, the James C. Bradford Melanoma Fund, and the Van Stephenson Melanoma Fund.

Author contributions

The project was designed by DBJ and SJ. Data analysis was performed by DBJ, SJ, FY, AL. Manuscript was written by DBJ and SJ. This submission has been reviewed and approved by all authors.

Data availability

No data are available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Competing interests

DBJ is on advisory boards or consults for BMS, Catalyst, Iovance, Jansen, Mallinckrodt, Merck, Mosaic ImmunoEngineering, Novartis, Oncosec, Pfizer, and Targovax, and receives research funding from BMS and Incyte. ANS has been on advisory boards or a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, and Novartis and has received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Immunocore, Novartis, Xcovery, Targovax, Polaris, Pfizer, Checkmate Pharmaceuticals, and Forhorn Therapeutics. RJS has been on advisory boards or a consultant over the last 36 months for BMS, Eisai, Iovance, Merck, Novartis, OncoSec, Pfizer, and has received research funding from Amgen and Merck. RDC has been on advisory boards or a consultant for BMS, Castle Biosciences, Compugen, Foundation Medicine, Immunocore, I-Mab, Incyte, Merck, Roche/Genentech, PureTech Health, Sanofi Genzyme, Sorrento Therapeutics, Rgenix, Chimeron, and Aura Biosciences. He has received research funding from Amgen, Astellis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bellicum, BMS, Corvus, Eli Lilly, Immunocore, Incyte, Macrogenics, Merck, Mirati, Novartis, Pfizer, Plexxikon, and Roche/Genentech. EA, SJ, and AZW have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional review board approval was received for study protocols from each institution.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-022-01942-z.

References

- 1.Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo J, Si L, Kong Y, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Zhu Y, et al. Phase II, open-label, single-arm trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with metastatic melanoma harboring c-Kit mutation or amplification. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2327–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.9275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carvajal RD, Antonescu CR, Wolchok JD, Chapman PB, Roman RA, Teitcher J, et al. KIT as a therapeutic target in metastatic melanoma. J Am Med Assoc. 2011;305:3182–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hodi FS, Corless CL, Giobbie-Hurder A, Fletcher JA, Zhu M, Marino-Enriquez A, et al. Imatinib for melanomas harboring mutationally activated or amplified kit arising on mucosal, acral, and chronically sun-damaged skin. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3182–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kelly CM, Gutierrez Sainz L, Chi P. The management of metastatic GIST: current standard and investigational therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Yaman B, Akalin T, Kandiloʇlu G. Clinicopathological characteristics and mutation profiling in primary cutaneous melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:389–97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Carlino MS, Haydu LE, Kakavand H, Menzies AM, Hamilton AL, Yu B, et al. Correlation of BRAF and NRAS mutation status with outcome, site of distant metastasis and response to chemotherapy in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:1530–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pracht M, Mogha A, Lespagnol A, Fautrel A, Mouchet N, le Gall F, et al. Prognostic and predictive values of oncogenic BRAF, NRAS, c-KIT and MITF in cutaneous and mucous melanoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1530–38. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ponti G, Manfredini M, Greco S, Pellacani G, Depenni R, Tomasi A, et al. BRAF, NRAS and c-KIT advanced melanoma: clinico-pathological features, targeted-therapy strategies and survival. Anticancer Res. 2017;37:6821–8. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.12175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beadling C, Jacobson-Dunlop E, Hodi FS, Le C, Warrick A, Patterson J, et al. KIT gene mutations and copy number in melanoma subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newell F, Wilmott JS, Johansson PA, Nones K, Addala V, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of acral melanoma reveals genomic complexity and diversity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:1446–56. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18988-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres-Cabala CA, Wang WL, Trent J, Yang D, Chen S, Galbincea J, et al. Correlation between KIT expression and KIT mutation in melanoma: A study of 173 cases with emphasis on the acral-lentiginous/mucosal type. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:3163. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newell F, Kong Y, Wilmott JS, Johansson PA, Ferguson PM, Cui C, et al. Whole-genome landscape of mucosal melanoma reveals diverse drivers and therapeutic targets. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pham DM, Guhan S, Tsao H. Kit and melanoma: biological insights and clinical implications. Yonsei Med J Yonsei Univ Coll Med. 2020;61:562–71. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2020.61.7.562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodman SE, Davies MA. Targeting KIT in melanoma: a paradigm of molecular medicine and targeted therapeutics. Biochemical Pharmacol. 2010;80:4342–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Demetri GD, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Joensuu H, et al. Kinase mutations and imatinib response in patients with metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:348–57. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steeb T, Wessely A, Petzold A, Kohl C, Erdmann M, Berking C, et al. c-Kit inhibitors for unresectable or metastatic mucosal, acral or chronically sun-damaged melanoma: a systematic review and one-arm meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2021;157:1380–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo J, Carvajal RD, Dummer R, Hauschild A, Daud A, Bastian BC, et al. Efficacy and safety of nilotinib in patients with kit-mutated metastatic or inoperable melanoma: final results from the global, single-arm, phase ii team trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1380–87. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Janku F, Bauer S, Shoumariyeh K, Jones RL, Spreafico A, Jennings J, et al. 1082P Phase I study of ripretinib, a broad-spectrum KIT and PDGFRA inhibitor, in patients with KIT-mutated or KIT-amplified melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:454–65. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.08.1467. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seifert AM, Zeng S, Zhang JQ, Kim TS, Cohen NA, Beckman MJ, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 blockade enhances T-cell activity and antitumor efficacy of imatinib in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:1094–100. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balachandran VP, Cavnar MJ, Zeng S, Bamboat ZM, Ocuin LM, Obaid H, et al. Imatinib potentiates antitumor T cell responses in gastrointestinal stromal tumor through the inhibition of Ido. Nat Med. 2011;17:234–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao Z, Yaeger R, Rodrik-Outmezguine VS, Tao A, Torres NM, Chang MT, et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature. 2017;548:234–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Garrido MC, Bastian BC. KIT as a therapeutic target in melanoma. J Investigative Dermatol. 2010;130:20–7. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.