Abstract

Background: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a serious neurodegenerative disease associated with the memory and cognitive impairment. The occurrence of AD is due to the accumulation of amyloid β-protein (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in the brain tissue as well as the hyperphosphorylation of Tau protein in neurons, doing harm to the human health and even leading people to death. The development of neuroprotective drugs with small side effects and good efficacy is focused by scientists all over the world. Natural drugs extracted from herbs or plants have become the preferred resources for new candidate drugs. Lignans were reported to effectively protect nerve cells and alleviate memory impairment, suggesting that they might be a prosperous class of compounds in treating AD.

Objective: To explore the roles and mechanisms of lignans in the treatment of neurological diseases, providing proofs for the development of lignans as novel anti-AD drugs.

Methods: Relevant literature was extracted and retrieved from the databases including China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Elsevier, Science Direct, PubMed, SpringerLink, and Web of Science, taking lignan, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, apoptosis, nerve regeneration, nerve protection as keywords. The functions and mechanisms of lignans against AD were summerized.

Results: Lignans were found to have the effects of regulating vascular disorders, anti-infection, anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-apoptosis, antagonizing NMDA receptor, suppressing AChE activity, improving gut microbiota, so as to strengthening nerve protection. Among them, dibenzocyclooctene lignans were most widely reported and might be the most prosperous category in the develpment of anti-AD drugs.

Conclusion: Lignans displayed versatile roles and mechanisms in preventing the progression of AD in in vitro and in vivo models, supplying potential candidates for the treatment of nerrodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: lignans, Alzheimer’s disease, nerve protection, mechanism, dibenzocyclooctene lignans

1 Introduction

Over the past 200 years, the development in public health and medical interventions had led to longer life expectancy, and population ageing has gradually become a challenge that couldn’t be ignored in the social and economic development. The global burden of pathological diseases related to aging is steadily increasing. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) was considered to be the most common age-related neurodegenerative disease and one of the most serious problems facing the world’s aging population (Ermogenous et al., 2020). The World Health Organization estimated that more than 55 million people worldwide suffered from dementia, with nearly 10 million new cases each year. The global patients of dementia were expected to reach 82 million by 2030 and 152 million by 2050 (Organization, 2021).

At present, it is generally accepted that typical histopathological traits of AD are the aggregation of amyloid β-protein (Aβ) in senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) of tau protein. However, the perception of AD are far from enough and the treatments are still limited. Untill now, there weren’t a drug completely curing AD or reversing the progression. Donepezil, rivastigmine, galanthamine and memantine were four medicines approved by FDA in which the first three were acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEI) (Ali et al., 2015; Behl et al., 2022) and memantine was an antagonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) (Sonkusare et al., 2005). They were usually used in alone or combination in the clinic according to the conditions of patients, and some were reported to cause hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal-related adverse reactions and muscle-related adverse reactions, which might lead to acute renal failure secondary to rhabdomyolysis in severe cases (Ali et al., 2015; Weller and Budson, 2018). Adduhelm (Aducanumab) is a monoclonal antibody that could selectively combine with the amyloid protein in brain and reduce the deposition of Aβ plaques in neurons (Sevigny et al., 2016). It is the first drug targeting the deposition of Aβ plaques approved by FDA in 2021 and used in treating early Alzheimer’s disease. However, clinical trials revealed that about 30%–40% of the patients taking adduhelm appeared brain microbleeds and edema (Torre and Lima., 2021). Sodium Oligomannate Capsules (GV-971) was a medicine affecting the neurological function by targeting the brain-gut axis. It was approved to treat mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease in China in 2019. The side effects were rare due to its natural character (oligosaccharide from Alge), but more clinical observations were needed to evaluate its long-term effects (Luo, 2020). The demand of anti-AD drugs with better effects or lower side effects are still in increasing, however, the success rate of drug development against AD was very low, 99% of the candidate drugs were in failure (Tatulian, 2022).

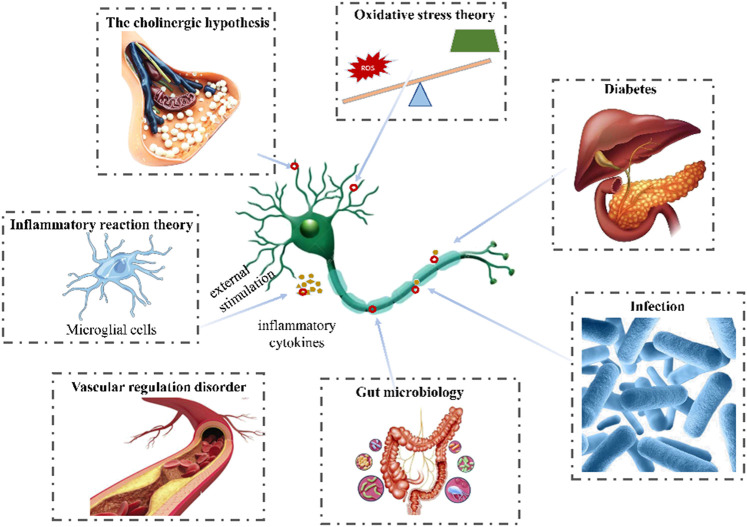

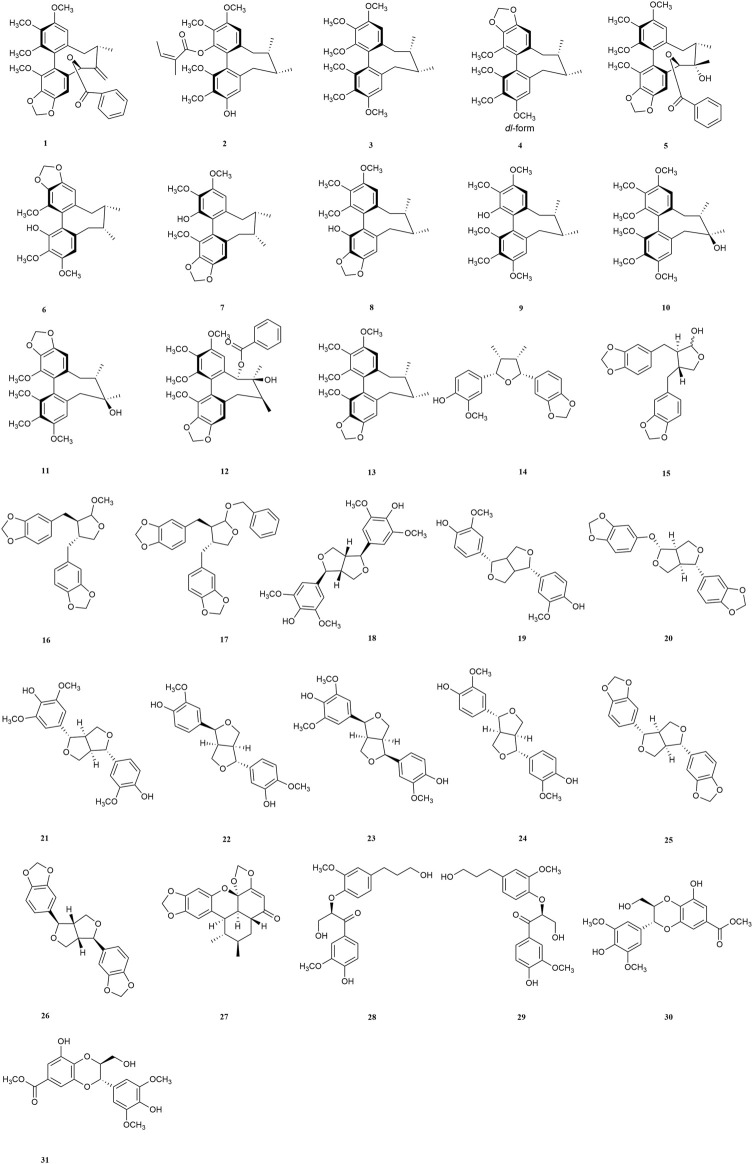

Plant chemicals might constitute important resources in the development of anti-AD due to their neuroprotective activities (Vaiserman et al., 2020). In the past, lignan and its extract were reported to effectively protect neuronal cell and improve cognitive ability (Zhou et al., 2021), however, their roles and mechanisms had never been summerized before. In this review, we referred the researches on the functions and mechanisms of lignans as well as the pathogenesis of AD, and analyze the potentiality of lignans in treating neurodegenerative diseases, aiming to supplying more candidates for anti-AD agents in the future. The pathogenesis of AD and structures of lignans in this paper are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

FIGURE 1.

Pathogenesis of AD (The pathogenesis of AD include vascular regulation disorder, infection, diabetes, inflammatory, oxidative stress, the cholinergic hypothesis, glutamic acid pathway and gut microbiology.).

FIGURE 2.

Structure of compounds 1–31.

2 Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease

2.1 Vascular regulation disorder

Increasing evidences suggested that the vascular dysregulation made the risk of AD increased (Lee et al., 2020). Elderly patients with AD are usually accompanied by cerebrovascular diseases, such as cerebral ischemia, hypoxia and hypoperfusion (Cipollini et al., 2020). Aβ deposition was reported to be observed in cerebral parenchyma and cerebral vessels in AD (Guo et al., 2020). And β-secretase protein level and enzyme activity in cerebrospinal fluid were increased, which is the key rate-limiting protease to produce Aβ (Hardy and Selkoe, 2002). According to the two-hit vascular hypothesis of AD (Nelson et al., 2016), cerebrovascular damage (hit 1) is an initial insult that directly initiates neuronal injury and neuro degeneration as well as promotes accumulation of Aβ toxin in the brain (hit 2). It was reported that a large number of inflammatory mediators were released to induce neuronal apoptosis and other neurological diseases during cerebral ischemia reperfusion (Cao et al., 2015). Vascular dysfunction would also induce the dimishment of Aβ clearance and increase of its production by influencing the amyloidogenic pathway in the brain (Zlokovic, 2011; Nelson et al., 2016).

2.2 Infection

Microbial infection is considered as an important cause in the occurence of AD. Sureda et al. detected gingipain (an enzyme secreted by Porphyromonas gingivalis) in the brain of mild to late AD patients (Sureda et al., 2020). Another example is the bacterial functional amyloid known as curli secreted by Escherichia coli migrate in the brain and triggers AD (Zhan et al., 2016). Bacteria could infect or colonize different cells in the brain, such as microglia, inducing AD (Bu et al., 2015). Besides, the bacteria and their components (capsular proteins, flagellin, fimbrillin, peptidoglycan, proteases) were considered as the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and could activate immune cells and interact with pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) such as TLR-2 and TLR-4, resulting in the pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion. This could result in a neuroinflammatory state leading to neuronal destruction and the disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), promoting Aβ deposition (Zlokovic, 2011; Keaney and Campbell, 2015).

2.3 Type 2 diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is the most common endocrine and metabolic disease, which is caused by insulin deficiency or insulin resistance. It has been reported to induce significant cognitive decline, leading to AD, especially in elderly patients (Ding et al., 2010). Insulin could cross the blood-brain barrier, and combine with insulin receptors of many brain cells (Banks et al., 2012). However, impaired insulin signaling and insulin resistance made the expression of insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) reduced in brain (Mullins et al., 2017), which is a significant contributor to Aβ degradation (Jayaraman and Pike, 2014). The downregulation of IDE could lead to the decrease of Aβ clearance and subsequently increase of Aβ accumulation in the brain as well as tau phosphorylation (Jolivalt et al., 2010).

2.4 Inflammatory reaction theory

Neuroinflammation is an immune response activated by glial cells in the central nervous system, which is considered to be one of the reasons causing kinds of neurodegenerative diseases including AD. Microglia are the brain’s innate immune cells, making up about 10% of all cells in the central nervous system. In AD patients, amyloid β-protein could combine with the receptors of microglia cells and then induce the release of inflammatory cytokines or chemokines such as COX-2, TNF-α, ILs, iNOS and so on, further impair the cognitive function. Therefore, the inhibition against activation of microglia cells, inflammatory factors, or downregulation the inflammation signaling pathways would all excert neroprotection functions. There are many signaling pathways involving in the regulation of neuroinflammation, in which P38/MAPK pathway, JNK/MAPK pathway, PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β/NRF2 pathway, MyD88 pathway, NF-κB pathway are all widely reported (Munoz and Ammit, 2010; Cuadrado et al., 2018; Fao et al., 2019; Ju Hwang et al., 2019).

2.5 Oxidative stress theory

Oxidation stress is closely related to the early occurcence of AD and its progression. Overproduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) could promote the secretion of inflammatory factors, form a cascade reaction to expand inflammation, and promote the pathological process of AD (Christov et al., 2004). Besides, extra ROS would also lead to mitochondrial damage (Sorce et al., 2017), which in turn activated NADPH oxidase to generate ROS again, aggravated the occurrence of oxidative stress (Sorce et al., 2017; Zott et al., 2018), causing protein and DNA dysfunction, and finally nerve cells apoptosis (Eckert et al., 2008; Yaribeygi et al., 2018). They could also bind to lipids and proteins of nerve cells to induce lipid peroxidation reaction, destroying the stability and fluidity of the membrane, leading to cell apoptosis (Morris, 2012). Thus, antioxidants or those with abilities to stimulate the oxidation defense system including enzymatic and nonenzymatic groups such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH) etc. might be useful in blocking the occurcence or progression of AD.

2.6 The cholinergic hypothesis

Early in the 1970s, Deutsch et al. have found that cholinergic systems were associated with memory formation and storage (Deutsch, 1971). Acetylcholine (Ding et al., 2010; Whitmer et al., 2021) is an important central excitatory neurotransmitter responsible for cognitive function and learning (Wang and Zhang, 2019). The function of cholinergic system in AD patients was defective (Lannfelt et al., 1993). Nucleus basalis of meynert (NBM) is the main distribution area of cholinergic neurons, which were reported to lost and degenerated in AD patients according to morphological studies (Briggs et al., 1997). Further study found that the concentration of Ach was significantly reduced in the brain of patients, which accelerated Aβ deposition, and induced a variety of pathological phenomena such as abnormal phosphorylation of Tau protein, neuronal inflammation, apoptosis, imbalance of neurotransmitter and neurohormone systems (Murray et al., 2013; Stepanichev et al., 2014). Acetylcholinesterase (AchE) is the decomposition enzymes of Ach, which could catabolize Ach into inactive choline and acetic acid metabolites and often used to evaluate the activity of cholinergic nervous system (Khan et al., 2018). In addition, AchE also participated in the formation of amyloid protein in brain cells (Houghton et al., 2006). Due to the role in the development of amyloid protein and the hydrolysis of Ach, the inhibition of AchE is regarded as a promising strategy for the treatment of AD.

2.7 Glutamatergic hypothesis

Impairment of the glutamatergic system is widely considered to be associated with pathomechanisms of AD (Danysz and Parsons, 2012). Many studies have shown that glutamate signaling pathway played an important role in synaptic plasticity and is dysregulated in AD (Taniguchi et al., 2022). Functional n-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) channels are heteromeric tetramers of GLUN1 and GLUN2A-D subunits. GluN2B containing NMDA receptors account for about 50% of all NMDA receptors (Chazot and Stephenson, 1997). In the different subtypes of NMDA receptors, GLUN2B types are the most prominent in the forebrain, which provided superior treatment target for AD (Yashiro and Philpot, 2008). When soluble Aβ oligomers (AβOs) binds to these receptors such as NMDA receptors on the cell membrane, it will cause neurotoxicity and AD (Cline et al., 2018).

2.8 Gut microbiota

Recent studies have shown that the pathogenesis of many neurodegenerative diseases may be related to intestinal flora. Symbiotic flora in the gastrointestinal tract regulate the neuroinflammation and central nervous system autoimmunity through gut-brain axis (La Rosa et al., 2018). Researchers found that the most distinctive changes of gut microflora in AD patients were the decreasing of Bifidobacterium breve strain A1 and the increasing of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which could lead to the enhancement of the inflammation levels in the plasma and brain (Bostanciklioglu, 2019). Clinical studies have shown that Bifidobacterium breve strain A1 is benificial to improve cognitive and mental health in patients with mild cognitive impairment (Okubo et al., 2021). The increasing of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes would lead to the decrease of cognitive function in AD patients (Wu et al., 2020).

3 Lignans as candidate phytochemicals

3.1 Dibenzocyclooctene lignans

3.1.1 Schisandrin

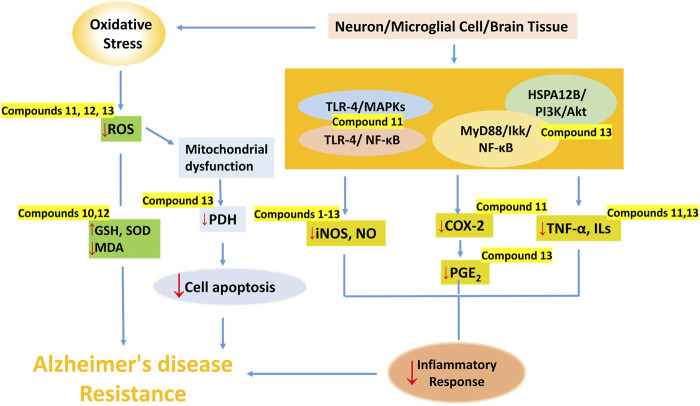

Hu et al. reported that eleven dibenzocyclooctene lignans (1–11) from the fruits of Schisandra chinensis had inhibitory effects on LPS-induced NO release in mouse BV2 microglial cells. It was worth noting that schisandrin (10) had the best activity (Hu et al., 2014), supplying a very prosperous candidates in treating AD. Besides, S-biphenyl as well as methylenedioxy were found to be the active groups according to structure-activity relationship studies, however, the presence of acetyl group on cyclooctadiene or hydroxyl group on C-7 would reduce the inhibitory activity on NO release (Hu et al., 2014).

In the in vivo model, Hu et al. also found that schisandrin (10) could significantly improve the short-term and spatial reference memory impairment of mice induced by Aβ. Glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) activity, GSH content in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus of rats increased, while MDA and GSSG contents decreased (Hu et al., 2012), suggesting schisandrin (10) might improve cognitive impairment through antioxidation.

3.1.2 Gomisin A

Gomisin A (11) in the fruits of Schisandra chinensis was reported not only to inhibit the production of NO, PGE2, but also suppress the expressions of iNOS and COX-2 in LPS-stimulated N9 microglia. TLR-4 is one of the main receptors in microglia and gomisin A (11) was reported to attenuate microglia-mediated neuroinflammation by inhibiting TLR-4-mediated NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways. Moreover, it also significantly inhibited LPS-induced ROS, NADPH oxidase activation, and GP91phox expression in microglia (Wang et al., 2014). At the same time, it reduced mRNA expression and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 production (Dong et al., 2006).

3.1.3 Schisantherin A

Schisantherin A (12) is a major bioactive lignan isolated from the fruits of Schisandra chinensis, which has potential therapeutic value for neurodegenerative diseases related to abnormal oxidative stress. In the in vivo studies, schisantherin A (12) increased the activities of SOD and GSH-Px, decreased the contents of Aβ and activities of MDA in hippocampus and cerebral cortex. It also significantly decreased the histopathological changes in the hippocampus (Li et al., 2014). Zhang et al. found that schisantherin A (12) could down-regulate the expression of iNOS, the accumulation of ROS, and inhibit the excessive production of NO in SH-SY5Y cells induced by 6-OHDA (Zhang et al., 2015). Results showed that schisantherin A (12) might exert neroprotection effects by both anti-inflamation and anti-oxidation.

3.1.4 Schisandrin B

In the in vivo study, Schisandrin B (SchB) (13) could significantly suppress the AChE activity and increase the level of Ach in scopolamine-induced dementia mice model (Giridharan et al., 2011). In differentiated neuronal PC12 cells of rats exposed to 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP), SchB showed the ability to resist apoptosis and necrosis by blocking the JNK-mediated pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) inhibition (Lam and Ko, 2012). It also displayed antiapoptotic effect on rat cortical neurons induced by Aβ in in vitro (Wang and Wang, 2009). In neuron-microglia cocultures, SchB exerted anti-neuroinflammatory activity by inhibiting MyD88/IKK/NF-κB signaling pathway, and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including NO, TNF-α, PGE2, IL-1β and IL-6 were all reduced. Moreover, SchB significantly inhibited ROS production and NADPH oxidase activity in microglia, thus playing a protective role in neurons (Zeng et al., 2012).

In the rat model, SchB might alleviate the damage of inflammatory response to nerve cells during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via regulating the HSPA12B/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Jiang et al., 2016), indicating that SchB could inhibit the secondary inflammatory response after cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. This indicates that SchB might have a potential therapeutic effect on AD complicated with cerebral ischemia.

3.1.5 Dibenzocyclooctene lignan-riched extract

Dibenzocyclooctene lignans are the characteristic compounds widely existed in Schisandra. It was shown that the extract from the fruits of Schisandra chinensis, which was enriched in dibenzocyclooctene lignans could alleviate the memory impairment in AD mice by inhibiting the activity of β-secretase in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus (Jeong et al., 2013). Wei et al. reported that the extract of Schisandra chinensis alleviated the inflammation caused by prostaglandins (PGs) metabolic disorders by regulating the metabolic disorders of polyunsaturated fatty acids in AD patients (Wei et al., 2019). These findings further suggest that dibenzocyclooctene lignans might be potential in preventing the occurrence or progression of AD.

3.2 Tetrahydrofuran lignans

Tetrahydrofuran lignans mainly exist in Camphoraceae, Magnoliaceae, Piperaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Nutmegaceae, Rehmanaceae, Compositae, Luteaceae, Lonicerae, Aristolaceae and other plants, which showed strong biological activities, including antitumor, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, insecticidal and estrogen-like effects as reported before (Briggs et al., 1997).

(−)-Talaumidin (14), isolated from the root of Aristolochia arcuata, has been shown to promote axon growth and displayed neuroprotection activity in primary rat cortical neurons and PC12 cells (Harada et al., 2015).

(−)-O-methylcubebin (16) and (−)-O-benzylcubebin (17), synthesized based on (−)-cubebin (15) from Piper cubeba L. f. in Piperaceae, showed the inhibitory effect on P. gingivalis (Rezende et al., 2016). Since the infection of bacteria would induce AD and the products of P. gingivalis could be detected in the brains, 15 might be useful in curing AD caused by infection.

3.3 Furofuranoid lignans

The structure of furofuranoid lignans was formed by condensation of hydroxyl groups on aliphatic hydrocarbon chains in tetrahydrofuran lignans. Some furofuranoid lignans including Syringaresinol (18), Pinoresinol (19), Sesamolin (20), Medioresinol (21) and so on were metabolized by intestinal flora to form enterolactone metabolites, which played a neuroprotective role after crossing the blood-brain barrier and reaching the brain. This provides evidence for lignans as potential modulators of the gut-brain axis (Senizza et al., 2020). (−)-7-epi-pinoresinol mr1 (22), (+)-medioresinol (23), and (+)-diapinoresinol (24) isolated from the leaves of Eucommiae ulmoides could protect the damage of PC-12 cells induced by H2O2 through PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β/NRF2 signaling pathway, which is one of the most important pathways in the regulation of Tau protein phosphorylation (Han et al., 2022).

Sesamin (SES) (25), a major lignan that is mainly obtained from sesame seeds and oil (Andargie et al., 2021), which could cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and accumulate in the brain (Umeda-Sawada et al., 1999). Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) are an important component of glial scar, which usually formed after central nervous system (CNS) injury (Burda and Sofroniew, 2014). Increased CSPGs are mainly used as a chemical barrier to protects the CNS (Davies et al., 1997; Silver and Miller, 2004). SES was reported to increase the expression of CSPGs biosynthesis and decrease degradation-related genes in the hippocampus of LPS-treated mice (Yamada et al., 2022). The effects of SES on adult neurogenesis were more obvious in the dorsal hippocampus (cognitive center) than in the ventral hippocampus (emotional center) (Yamada et al., 2018). It was also found that SES could play a neuroprotective role in in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. SES reduced anxiety/depression like behaviors, increased exercise/exploration activities, and improved passive avoidance learning and memory. It was suggested that SES could reduce blood glucose, inhibit neuroinflammation and enhance neurotrophic factors to against AD caused by diabetes (Ghaderi et al., 2021).

(−)-Sesamin (26) is a major lignan constituent in the roots of Asiasarum sieboldi, which ameliorated spatial and habit learning memory deficits by modulating both NMDA receptor and dopaminergic neuronl systems. After exposure to chronic electric footshock (EF)-induced stress, the levels of NMDA receptor phosphorylation were reduced by treatment with (−)-sesamin at both doses (25 and 50 mg/kg). The retention latency in passive avoidance test and dopamine levels in substantia nigra striatum were decreased by chronic EF stress, and increased after (−)-sesame treatment (Zhao et al., 2016).

3.4 Benzoxanthene lignans

Sauchinone (27), isolated from the roots of Saururus chinensis, supplied a useful adjunctive treatment for the treatmeng of AD cased by bacterial infection, since It enhanced phagocytosis of macrophages to Escherichia coli through p38/MAPK signaling pathway in rats macrophages in a concentration dependent manner (Jeong et al., 2014).

3.5 Norlignans

(R)-1-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-(3-methoxy-1-hydroxypropylphenoxy)-3-hydroxypropan (28) and (S)-1-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-(3-methoxy-1 - hydroxypropylphenoxy)-3-hydroxypropan (29) are a pair of enantiomers isolated from the seeds of Prunus tomentosa by Liu et al. (Liu et al., 2019). They were reported to exhibit hydrogen bonding interactions with Aβ in molecular docking studies, sharing the similar binding site at residue Gln15 with the positive compound curcumin, and their activities on anti-Aβ aggregation were further verified by thioflavin T (ThT) method with the inhibitory rate 63.25 ± 2.68% (28) and 67.13 ± 0.90% (29), higher than positive drug.

3.6 Neolignans

Wang et al. isolated two rare 8′, 9′-dinor-3′, 7-epoxy-8, 4′-oxyneolignanes from the twigs and leaves of Pithecellobium clypearia named as (7S, 8S)- and (7R, 8R)-pithecellobiumin A (30, 31) respectively, which are a pair of enantiomers of neolignans (Wang et al., 2018). Enantiomers compounds 30 (62.1%) and 31 (81.6%) showed different degrees of anti-Aβ aggregation activity by ThT method. However, they showed different interaction mode with Aβ according to molecular docking studies. Compound 30 interacted with Leu34 of Aβ while compound 31 interacted with Gly9 and Gln15. The results showed compounds 30 and 31 have potentials to treat AD by inhibiting the formation of Aβ aggregation.

4 Conclusion and Foresight

In this paper, we focus on the neuroprotective and cognitive enhancement effects of lignans and their mechanisms, providing a basis for the development of lignans as new anti-AD drugs. Lignans exerted neuroprotective and cognitive enhancement effects through regulating vascular disorders, anti-infection, anti-inflammation, anti-oxidation, anti-apoptosis, antagonizing NMDA receptor, suppressing AChE activity, improving gut microbiota, and regulating different signaling pathways as shown in Table 1. Among them, biphenyl cyclooctene lignans are the most potential lignans, in which anti-inflamation, anti-oxidation and antipoptosis effects on neurons, microglial or brain tissue were widely reported (Figure 3).

TABLE 1.

The action mechanisms of major lignans.

| Category | Compound Name | Origin | In vitro/In vivo models | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dibenzocyclooctene lignans | Schisanchinin A (1) | The fruits of Schisandra chinensis | LPS-induced BV2 microglia in mouse | Anti-inflammation | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Schisanchinin B (2) | |||||

| Deoxyschizandrin (3) | |||||

| (±)-γ-schizandrin (4) | |||||

| Gomisin G (5) | |||||

| (-)-gomisin M1 (6) | |||||

| (-)-gomisin L1 (7) | |||||

| (+)-gomisin M2 (8) | |||||

| (+)-gomisin K3 (9) | |||||

| Schisandrin (10) | |||||

| Gomisin A (11) | |||||

| Schisandrin (10) | The fruits of Schisandra chinensis | Mice | Anti-oxidation | Cao et al. (2015) | |

| Gomisin A (11) | The fruits of Schisandra chinensis | LPS-stimulated N9 microglia | Anti-inflammation | Dong, Hung et al. (2006) | |

| LPS-stimulated N9 microglia | Anti-oxidation | Wang, Hu et al. (2014) | |||

| Schisantherin A (12) | The fruits of Schisandra chinensis | Aβ induced AD rat | Anti-oxidation | Li, Zhao et al. (2014) | |

| SH-SY5Y cells induced by 6—OHDA | Anti-inflammation | Zhang, Lun et al. (2015) | |||

| Schisandrin B (13) | The fruits of Schisandra chinensis | Scopolamine-induced dementia mice | Suppressing AChE activity | Giridharan, Thandavarayan et al. (2011) | |

| PC12 cells exposed to 3-NP | Anti-apoptotic | Lam and Ko (2012) | |||

| Rat cortical neurons induced by Aβ in vitro | Anti-apoptotic | Wang and Wang (2009) | |||

| Neuron–microglia co-cultures | Anti-oxidation | Zeng, Zhang et al. (2012) | |||

| Anti-inflammation | |||||

| Rat model of cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury | Regulation of vascular disorders | Liu et al. (2019) | |||

| Tetrahydrofuran lignans | (−)-Talaumidin (14) | The roots of Aristolochia contorta | PC12 cells | Promoting neuronal growth | Harada, Kenichi et al. (2015) |

| (−)-cubebin (15) | The synthesized compounds | Porphyromonas gingivalis suspension | Anti-infection |

(Karen, C. et al., 2016) | |

| (−)-O-methylcubebin (16) | |||||

| (−) -O-benzylcubebin (17) | |||||

| Furofuranoid lignans | Medioresinol (18) | Sesame seeds, Cloudberry | Intestinal flora | Modulation of gut microbiota | Senizza, Rocchetti et al. (2020) |

| Syringaresinol (19) | Rye, whole Grain flour | ||||

| Pinoresinol (20) | Olive oil | ||||

| Sesamolin (21) | Sesame seeds | ||||

| (–)-7-epi-Pinoresinol mr1 (22) | The leaves of Eucommiae ulmoides | H2O2-treated PC12 cells |

Anti-Tau protein phosphorylation | Han, Yu et al. (2022) | |

| (+)-Medioresinol (23) | Antioxidant | ||||

| (+)-Diapinoresinol (24) | |||||

| Sesamin (25) | Sesame seeds and oil | LPS-treated mice | Promoting neuronal growth | Yamada, Maeda et al. (2022) | |

| Rat model of diabetes | Anti-diabetics | Ghaderi, Rashno et al. (2021) | |||

| Anti-inflammation | |||||

| (−)-Sesamin (26) | The roots of Asiasarum sieboldi | Mice induced by chronic electric footshock | Antagonizing NMDA receptor | Zhao, Shin et al. (2016) | |

| Benzoxanthene lignans | Sauchinone (27) | The roots of Saururus chinensis | Mice injected with 4% Brewer thioglycollate | Anti- inflammation | Jeong, Choi et al. (2014) |

| Norlignans | (R)-1-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-(3-methoxy-1-hydroxypropylphenoxy)-3-hydroxypropan (28) | The seeds of Prunus tomentosa | ThT method | Inhibition of Aβ aggregation | Liu et al. (2019) |

| (S)-1-(3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenyl)-2-(3-methoxy-1-hydroxypropylphenoxy)-3-hydroxypropan (29) | |||||

| Benzofuran lignans | (7S, 8S)-pithecellobiumin A (30) | The twigs and leaves of Pithecellobium clypearia | ThT method | Inhibition of Aβ aggregation | Wang, Zhou et al. (2018) |

| (7R, 8R)-pithecellobiumin A (31) |

FIGURE 3.

The main mechanisms of dibenzocyclooctene lignans against AD. (Dibenzocyclooctene lignans play a protective role in the nervous system through anti-inflammation, antioxidation and inhibition of neuronal apoptosis. Compounds 1–13 inhibited the activity of NO, compounds 11 and 13 inhibited the release of downstream inflammatory factors by regulating TLR-4-mediated NF-κB and MAPKs signaling pathways, MyD88/IKK/NF-κB and HSPA12B/PI3K/Akt signaling pathways. In addition, Compounds 10 and 12 up-regulated the expression of SOD and GSH, and inhibited MDA in brain tissue, while compounds 11 and 13 reduced the content of ROS to resist oxidative stress. Compound 13 also inhibited apoptosis by inhibiting JNK-mediated PDH inhibition.).

In addition, since long-term use of existing commercially available drugs will bring serious side effects, drugs with less side effects would be more popular in the future. As natural compounds, lignans are abundant in fruits, vegetables and grains with low toxicity and good bioavailability (Jin et al., 2013; Kumar et al., 2021)

One of the most challenging problems in the development of therapeutic drugs for neurodegenerative diseases is that drugs cannot cross the blood-brain barrier. However, the lignans such as schisantherin A and schisandrin B were reported to be capable to cross the BBB due to their lipid-soluble properties and small-molecular mass (Hu et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018), which further improve the possibilities of lignans to be developed as anti-AD drugs.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, NH and JY; methodology, NH and YW; investigation, YW; data curation, YW;validation, NH; writing—original draft preparation, YW; writing—review and editing, NH; formal analysis, ZL, JZ and SL; project administration, NH; funding acquisition, JY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by Foundation of Liaoning Education Department (Grant No. LJKZ0933).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ali T. B., Schleret T. R., Reilly B. M., Chen W. Y., Abagyan R. (2015). Adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors in dementia, according to the pharmacovigilance databases of the united-states and Canada. PLoS ONE 10 (12), e0144337 10.1371/journal.pone.0144337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andargie M., Vinas M., Rathgeb A., Moller E., Karlovsky P. (2021). Lignans of sesame (sesamum indicum L.): A comprehensive review. Molecules 26 (4), 883. 10.3390/molecules26040883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks W. A., Owen J. B., Erickson M. A. (2012). Insulin in the brain: There and back again. Pharmacol. Ther. 136 (1), 82–93. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behl T., Kaur I., Sehgal A., Singh S., Sharma N., Makeen H. A., et al. (2022). "“Aducanumab” making a comeback in alzheimer’s disease: An old wine in a new bottle." Biomed. Pharmacother. 148: 112746 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostanciklioglu M. (2019). The role of gut microbiota in pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J. Appl. Microbiol. 127 (4), 954–967. 10.1111/jam.14264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briggs C. A., Anderson D. J., Brioni J. D., Buccafusco J. J., Buckley M. J., Campbell J. E., et al. (1997). Functional characterization of the novel neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ligand gts-21 in vitro and in vivo . Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 57 (1-2), 231–241. 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00354-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu X. L., Yao X. Q., Jiao S. S., Zeng F., Liu Y. H., Xiang Y., et al. (2015). A study on the association between infectious burden and Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 22 (12), 1519–1525. 10.1111/ene.12477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda J. E., Sofroniew M. V. (2014). Reactive gliosis and the multicellular response to cns damage and disease. Neuron 81 (2), 229–248. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X. L., Du J., Zhang Y., Yan J. T., Hu X. M. (2015). Hyperlipidemia exacerbates cerebral injury through oxidative stress, inflammation and neuronal apoptosis in mcao/reperfusion rats. Exp. Brain Res. 233 (10), 2753–2765. 10.1007/s00221-015-4269-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazot P. L., Stephenson F. A. (1997). Molecular dissection of native mammalian forebrain nmda receptors containing the nr1 C2 exon: Direct demonstration of nmda receptors comprising Nr1, Nr2a, and Nr2b subunits within the same complex. J. Neurochem. 69 (5), 2138–2144. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69052138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christov A., Ottman J. T., Grammas P. (2004). Vascular inflammatory, oxidative and protease-based processes: Implications for neuronal cell death in Alzheimer's disease. Neurol. Res. 26 (5), 540–546. 10.1179/016164104225016218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipollini V., Troili F., Giubilei F. (2020). Vascular dementia: An overview. Diagnosis Manag. Dementia 1, 17–32. 10.1016/B978-0-12-815854-8.00002-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cline E. N., Bicca M. A., Viola K. L., Klein W. L. (2018). The amyloid-beta oligomer hypothesis: Beginning of the third decade. J. Alzheimers Dis. 64 (s1), S567–S610. 10.3233/JAD-179941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado A., Kugler S., Lastres-Becker I. (2018). Pharmacological targeting of gsk-3 and Nrf2 provides neuroprotection in a preclinical model of tauopathy. Redox Biol. 14 (2), 522–534. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysz W., Parsons C. G. (2012). Alzheimer's disease, beta-amyloid, glutamate, nmda receptors and memantine--searching for the connections. Br. J. Pharmacol. 167 (2), 324–352. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02057.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. J. A., Fitch M. T., Memberg S. P., Hall A. K., Raisman G., Silver J. (1997). Regeneration of adult axons in white matter tracts of the central nervous system. Nature 390 (6661), 680–683. 10.1038/37776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch J. A. (1971). The cholinergic synapse and the site of memory. Science 174 (4011), 788–794. 10.1126/science.174.4011.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., Strachan M. W., Reynolds R. M., Frier B. M., Deary I. J., Fowkes F. G., et al. (2010). Diabetic retinopathy and cognitive decline in older people with type 2 diabetes: The edinburgh type 2 diabetes study. Diabetes 59 (11), 2883–2889. 10.2337/db10-0752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H. K., Hung T. M., Bae K. H., Ji W. J., Lee S., Yoon B. H., et al. (2006). Gomisin a improves scopolamine-induced memory impairment in mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 542 (1-3), 129–135. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert A., Hauptmann S., Scherping I., Rhein V., Muller-Spahn F., Gotz J., et al. (2008). Soluble beta-amyloid leads to mitochondrial defects in amyloid precursor protein and tau transgenic mice. Neurodegener. Dis. 5 (3-4), 157–159. 10.1159/000113689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermogenous C., Green C., Jackson T., Ferguson M., Lord J. M. (2020). Treating age-related multimorbidity: The drug discovery challenge. Drug Discov. Today 25 (8), 1403–1415. 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fao L., Mota S. I., Rego A. C. (2019). Shaping the nrf2-are-related pathways in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 54, 100942 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaderi S., Rashno M., Nesari A., Khoshnam S. E., Sarkaki A., Khorsandi L., et al. (2021). Sesamin alleviates diabetes-associated behavioral deficits in rats: The role of inflammatory and neurotrophic factors. Int. Immunopharmacol. 92, 107356 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.107356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giridharan V. V., Thandavarayan R. A., Sato S., Ko K. M., Konishi T. (2011). Prevention of scopolamine-induced memory deficits by schisandrin B, an antioxidant lignan from Schisandra chinensis in mice. Free Radic. Res. 45 (8), 950–958. 10.3109/10715762.2011.571682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T., Zhang D., Zeng Y., Huang T. Y., Xu H., Zhao Y. (2020). Molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 15 (1), 40. 10.1186/s13024-020-00391-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han R., Yu Y., Zhao K., Wei J., Hui Y., Gao J.-M. (2022). Lignans from eucommia ulmoides oliver leaves exhibit neuroprotective effects via activation of the pi3k/akt/gsk-3β/nrf2 signaling pathways in H2O2-treated pc-12 cells. Phytomedicine. 101, 154124 10.1016/j.phymed.2022.154124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada K., Kubo M., Horiuchi H., Ishii A., Esumi T., Hioki H., et al. (2015). Systematic asymmetric synthesis of all diastereomers of (-)-Talaumidin and their neurotrophic activity. J. Org. Chem. 80 (14), 7076–7088. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297 (5580), 353–356. 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton P. J., Ren Y., Howes M. J. (2006). Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors from plants and fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 23 (2), 181–199. 10.1039/b508966m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Cao Y., He R., Han N., Liu Z., Miao L., et al. (2012). Schizandrin, an antioxidant lignan from Schisandra chinensis, ameliorates abeta1-42-induced memory impairment in mice. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012 (7). 10.1155/2012/721721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Han N., Yao X., Liu Z., Wang Y., Yang J., et al. (2014). Structure-activity relationship study of dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans isolated from Schisandra chinensis on lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia activation. Planta Med. 80 (8-9), 671–675. 10.1055/s-0034-1368592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D., Yang Z., Yao X., Wang H., Han N., Liu Z., et al. (2014). Dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans from Schisandra chinensis and their inhibitory activity on No production in lipopolysaccharide-activated microglia cells. Phytochemistry 104, 72–78. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman A., Pike C. J. (2014). Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes: Multiple mechanisms contribute to interactions. Curr. Diab. Rep. 14 (4), 476. 10.1007/s11892-014-0476-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong E. J., Lee H. K., Lee K. Y., Jeon B. J., Kim D. H., Park J. H., et al. (2013). The effects of lignan-riched extract of shisandra chinensis on amyloid-Β-induced cognitive impairment and neurotoxicity in the cortex and Hippocampus of mouse. J. Ethnopharmacol. 146 (1), 347–354. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong K. M., Choi J. I., Lee S. H., Lee H. J., Son J. K., Seo C. S., et al. (2014). Effect of sauchinone, a lignan from Saururus chinensis, on bacterial phagocytosis by macrophages. Eur. J. Pharmacol 728, 176–182. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang E., Tang Z., Chunyan Y. U., Chunrong Y. U., Zhu W., Pathology D. O. (2016). Protective effect of schisandrin B on cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury of rats and its mechanisms. J. Jilin Univ. Med. Sci. 42 (5), 860–865. 10.13481/j.1671-587x.20160504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H., Qi L., Liu W., Yuan R., Wen N., Yu H. Q. (2013). The toxic effect of schisandrin on nerve cells and its antitumor effect on glioma cells. Chin. J. Gerontology 33 (6), 1325–1326. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-9202.2013.06.041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jolivalt C. G., Lee C. A., Beiswenger K. K., Smith J. L., Orlov M., Torrance M. A., et al. (2010). Defective insulin signaling pathway and increased glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity in the brain of diabetic mice: Parallels with Alzheimer's disease and correction by insulin. J. Neurosci. Res. 86 (15), 3265–3274. 10.1002/jnr.21787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Hwang C., Choi D. Y., Park M. H., Hong J. T. (2019). NF-κB as a key mediator of brain inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 18 (1), 3–10. 10.2174/1871527316666170807130011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keaney J., Campbell M. (2015). The dynamic blood–brain barrier. FEBS J. 282 (21), 4067–4079. 10.1111/febs.13412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan H., MaryaAmin S., Kamal M. A., Patel S. (2018). Flavonoids as acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Current therapeutic standing and future prospects. Biomed. Pharmacother. 101, 860–870. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Chidambaram V., Mehta J. L. (2021). Plant-based diet, gut microbiota, and bioavailability of lignans. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 78 (24), e311. 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.09.1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa F., Clerici M., Ratto D., Occhinegro A., Licito A., Romeo M., et al. (2018). The gut-brain Axis in Alzheimer's disease and omega-3. A critical overview of clinical trials. Nutrients 10 (9), 1267. 10.3390/nu10091267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam P. Y., Ko K. M. (2012). Beneficial effect of (-)Schisandrin B against 3-nitropropionic acid-induced cell death in PC12 cells. Biofactors 38 (3), 219–225. 10.1002/biof.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannfelt L., Folkesson R., Mohammed A. H., Winblad B., Hellgren D., Duff K., et al. (1993). Alzheimer's disease: Molecular genetics and transgenic animal models. Behav. Brain Res. 57 (2), 207–213. 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90137-f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Kim K., Lee Y. C., Kim S., Won H. H., Yu T. Y., et al. (2020). Associations between vascular risk factors and subsequent Alzheimer's disease in older adults. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 12 (1), 117. 10.1186/s13195-020-00690-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Zhao X., Xu X., Mao X., Liu Z., Li H., et al. (2014). Schisantherin A recovers Aβ-induced neurodegeneration with cognitive decline in mice. Physiol. Behav. 132, 10–16. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Wang J., Lin B., Cheng Z, Y., Bai M., Shi S., et al. (2019). Phenylpropanoids and lignans from Prunus tomentosa seeds as efficient beta-amyloid (abeta) aggregation inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 84, 269–275. 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q. (2020). “A new drug for alzheimer 'S disease-sodium oligomannate Capsules,” in CNKI:SUN:JKSH, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Morris M. C. (2012). Nutritional determinants of cognitive aging and dementia. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 71 (1), 1–13. 10.1017/S0029665111003296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins R. J., Diehl T. C., Chia C. W., Kapogiannis D. (2017). Insulin resistance as a link between amyloid-beta and tau pathologies in Alzheimer's disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 118. 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz L., Ammit A. J. (2010). Targeting P38 MAPK pathway for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 58 (3), 561–568. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. P., Faraoni M. B., Castro M. J., Alza N. P., Cavallaro V. (2013). Natural ache inhibitors from plants and their contribution to Alzheimer's disease therapy. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 11 (4), 388–413. 10.2174/1570159X11311040004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson A. R., Sweeney M. D., Sagare A. P., Zlokovic B. V. (2016). Neurovascular dysfunction and neurodegeneration in dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862 (5), 887–900. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okubo R., Xiao J., Matsuoka Y. J. (2021). “Chapter 49—Potential beneficial effects of bifidobacterium breve A1 on cognitive impairment and psychiatric disorders,“ in The neuroscience of depression. Editors Martin C. R. (Academic Press: ), 497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Rezende K. C. S., Lucarini R., Simaro G. V., Pauletti P. M., Januario A. H., Esperandim V. R., et al. (2016). Antibacterial activity of (-)-Cubebin isolated from piper cubeba and its semisynthetic derivatives against microorganisms that cause endodontic infections. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 26 (3), 296–303. 10.1016/j.bjp.2015.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senizza A., Rocchetti G., Mosele J. I., Patrone V., Callegari M. L., Morelli L., et al. (2020). Lignans and gut microbiota: An interplay revealing potential health implications. Molecules 25 (23), 5709. 10.3390/molecules25235709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevigny J., Chiao P., Bussiere T., Weinreb P. H., Williams L., Maier M., et al. (2016). The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 537 (7618), 50–56. 10.1038/nature19323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver J., Miller J. H. (2004). Regeneration beyond the glial scar. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5 (2), 146–156. 10.1038/nrn1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonkusare S. K., Kaul C. L., Ramarao P. (2005). Dementia of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders--memantine, a new hope. Pharmacol. Res. 51 (1), 1–17. 10.1016/j.phrs.2004.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S., Stocker R., Seredenina T., Holmdahl R., Aguzzi A., Chio A., et al. (2017). Nadph oxidases as drug targets and biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases: What is the evidence? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 112, 387–396. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanichev M., Lazareva N., Tukhbatova G., Salozhin S., Gulyaeva N. (2014). Transient disturbances in contextual fear memory induced by Aβ(25-35) in rats are accompanied by cholinergic dysfunction. Behav. Brain Res. 259, 152–157. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureda A., Daglia M., Arguelles Castilla S., Sanadgol N., Fazel Nabavi S., Khan H., et al. (2020). Oral microbiota and Alzheimer's disease: Do all roads lead to rome? Pharmacol. Res. 151, 104582 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K., Yamamoto F., Amano A., Tamaoka A., Sanjo N., Yokota T., et al. (2022). Amyloid-Β oligomers interact with NMDA receptors containing Glun2b subunits and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 in primary cortical neurons: Relevance to the synapse pathology of alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Res 180, 90–98. 10.1016/j.neures.2022.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatulian S. A. (2022). Challenges and hopes for alzheimer’s disease. Drug Discov. Today 27(4), 1027–1043. 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre J., Lima G. (2021). The fda approves aducanumab for Alzheimer's disease, raising important scientific Questions1. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 82 (3), 881–882. 10.3233/JAD-210736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda-Sawada R., Ogawa M., Igarashi O. (1999). The metabolism and distribution of sesame lignans (sesamin and episesamin) in rats. Lipids 34 (6), 633–637. 10.1007/s11745-999-0408-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiserman A., Koliada A., Lushchak O. (2020). Neuroinflammation in pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease: Phytochemicals as potential therapeutics. Mech. Ageing Dev. 189 (4), 111259 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Wang X. M. (2009). Schisandrin B protects rat cortical neurons against abeta1-42-induced neurotoxicity. Pharmazie 64 (7), 450–454. 10.1691/ph.2009.9552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhang H. (2019). Reconsideration of anti-cholinesterase therapeutic strategies against Alzheimer's disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 10 (2), 852–862. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Hu D., Zhang L., Lian G., Zhao S., Wang C., et al. (2014). Gomisin a inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in N9 microglia via blocking the NF-κB/MAPKs pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 63, 119–127. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.10.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. X., Zhou L., Wang J., Lin B., Wang X. B., Huang X. X., et al. (2018). "Enantiomeric lignans with anti-β-amyloid aggregation activity from the twigs and leaves of Pithecellobium clypearia benth." Bioorg. Chem. 77: 579–585. doi: doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., You L., Cheng Y., Hu K., Wang Z., Cheng Y., et al. (2018). Investigation of pharmacokinetics, tissue distribution and excretion of schisandrin B in rats by HPLC-MS/MS. Biomed. Chromatogr. 32 (2), e4069 10.1002/bmc.4069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei M., Liu Z., Liu Y., Li S., Hu M., Yue K., et al. (2019). Urinary and plasmatic metabolomics strategy to explore the holistic mechanism of lignans in S. Chinensis in treating Alzheimer's disease using UPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Food Funct. 10 (9), 5656–5668. 10.1039/c9fo00677j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller J., Budson A. (2018). Current understanding of Alzheimer's disease diagnosis and treatment. F1000Res. 7, F1000 Faculty Rev-1161. 10.12688/f1000research.14506.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer R. A., Gilsanz P., Quesenberry C. P., Karter A. J., Lacy M. E. (2021). Association of type 1 diabetes and hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic events and risk of dementia. Neurology 97 (3), e275–e283. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2021). Dementia. from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Wu Y. X., Bao X. Y., Li H. Y., Du Y., Sun T., Wang R. C., et al. (2020). Relationship between relative abundance of intestinal flora and cognitive function in alzheimer' S disease." medical review. J. Appl. Clin. Pediatr. 23 (18), 2259–2265. 10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2019.00.778 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J., Maeda S., Soya M., Nishida H., Iinuma K. M., Jinno S. (2022). Alleviation of cognitive deficits via upregulation of chondroitin sulfate biosynthesis by lignan sesamin in a mouse model of neuroinflammation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 108, 109093 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2022.109093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada J., Nadanaka S., Kitagawa H., Takeuchi K., Jinno S. (2018). Increased synthesis of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis in response to enriched environment. J. Neurosci. 38 (39), 8496–8513. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0632-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaribeygi H., Panahi Y., Javadi B., Sahebkar A. (2018). The underlying role of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration: A mechanistic review. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 17 (3), 207–215. 10.2174/1871527317666180425122557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro K., Philpot B. D. (2008). Regulation of nmda receptor subunit expression and its implications for LTD, LTP, and metaplasticity. Neuropharmacology 55 (7), 1081–1094. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng K. W., Zhang T., Fu H., Liu G. X., Wang X. M. (2012). Schisandrin B exerts anti-neuroinflammatory activity by inhibiting the Toll-like receptor 4-dependent MyD88/IKK/NF-κB signaling pathway in lipopolysaccharide-induced microglia. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 692 (1-3), 29–37. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan X., Stamova B., Jin L.-W., DeCarli C., Phinney B., Sharp F. R. (2016). Alzheimer's & dementia 12. 7S_Part_15, P739. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.1544 Lipopolysaccharide and E. Coli proteins and DNA in Alzheimer's disease brains compared to controls [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L. Q., Sa F., Chong C. M., Wang Y., Zhou Z. Y., Chang R. C., et al. (2015). Schisantherin a protects against 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic neuron damage in zebrafish and cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells through the ROS/NO and AKT/GSK3 pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 170, 8–15. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao T. T., Shin K. S., Park H. J., Kim K. S., Lee K. E., Cho Y. J., et al. (2016). Effects of (-)-Sesamin on chronic stress-induced memory deficits in mice. Neurosci. Lett. 634, 114–118. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y., Men L., Sun Y., Wei M., Fan X. (2021). Pharmacodynamic Effects and Molecular Mechanisms of Lignans from Schisandra Chinensis. Eur. J. Pharmacol 892, 173796. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic B. V. (2011). Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and other disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 (12), 723–738. 10.1038/nrn3114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zott B., Busche M. A., Sperling R. A., Konnerth A. (2018). What happens with the circuit in Alzheimer's disease in mice and humans? Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 41 (1), 277–297. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-080317-061725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]