Abstract

The pediatric-to-adult care transition has been correlated with worse outcomes, including increased mortality. Emerging adults transitioning from child-specific healthcare facilities to adult hospitals encounter marked differences in environment, culture, and processes of care. Accordingly, emerging adults may experience care differently than other hospitalized adults. We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients admitted to a large urban safety net hospital and compared all domains of patient experience between patients in 3 cohorts: ages 18 to 21, 22 to 25, and 26 years and older. We found that patient experience for emerging adults aged 18 to 21, and, to a lesser extent, aged 22 to 25, was significantly and substantially worse as compared to adults aged 26 and older. The domains of worsened experience were widespread and profound, with a 38-percentile difference in overall experience between emerging adults and established adults. While emerging adults experienced care worse in nearly all domains measured, the greatest differences were found in those pertinent to relationships between patients and care providers, suggesting a substantial deficit in our understanding of the preferences and values of emerging adults.

Keywords: patient experience, emerging adults, inpatient experience, adolescence, young adults, Press Ganey, patient–physician relationship, patient–nurse relationship

Introduction

The transition from pediatric to adult care is a vulnerable time for patients—one that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality (1–5). Although many prior studies have focused on the transition experience in outpatient settings (1,4,5), the inpatient experiences of emerging adults in the United States are not well studied. However, it is known that adolescents experience care differently than younger children admitted to children's hospitals (6–9).

Emerging adulthood, defined as 18 to 25 years of age, is a unique life stage (10). Emerging adults may have the physical appearance of adulthood, but they are still growing in “physiological, intellectual, social, emotional, and behavioral” domains (11). Further, this is often a time of frequent changes in life, work, and school, and it is when many people lay the foundation for adulthood (12). Emerging adults transitioning from child-specific healthcare facilities to adult hospitals encounter drastically different environments, cultures, and processes of care. As an emerging adult's first experience with healthcare may be hospitalization, a poor experience may lead to decreased adherence to recommended care.

Patient experience, as defined by Bull et al (13), aims to measure “‘what’ happened during an episode of care, and ‘how’ it happened from the perspective of the patient.” This differs from patient satisfaction, which is a subjective aspect of a patient's overall experience (14). Improvements in patient experience (PEX) correlate with improved adherence to care and lower inpatient mortality rates (15) as well as lower 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia (16). Although there is much known on the positive patient effects of improved PEX(17–19), there is little published data describing the relationship between patient-related characteristics, such as age, and how this affects the patient experience. Our study aimed to explore how the PEX of emerging adults compares to established adults and to identify in which domains their experiences may be similar or different.

Methods

Study Population and Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study of patients admitted to a large, urban academic safety net hospital in the southwestern United States. We extracted demographic data for patients 18 years old and older who were discharged from the hospital between October 1, 2015, and September 30, 2019, using a de-identified PEX dataset collected via Press Ganey Associates LLC (PG). The PG integrated survey combines the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAPHS) survey from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) with additional PG proprietary questions about the patient experience (20). The survey includes 38 of these additional proprietary questions about various aspects of the hospital stay that were used for these analyses. Responses to the various aspects of the hospital stay were rated by patients on a 5-point Likert scale with response options of “very poor,” “poor,” “fair,” “good,” and “very good.” Responses were converted to a numerical score of 0, 25, 50, 75, or 100, respectively. Composite scores for the 10 domains were obtained by calculating the mean score from each domain's questions. Incomplete survey responses were not used in composite score calculations. Composite scores for each health facility were converted to percentile rankings by PG, which were compared across different domains by age groups. The 10 domains include admission, room, food, nurses, physicians, tests and treatment, discharge, family and visitors, personal issues, and the overall score.

PG surveys were mailed to all inpatient discharges except those meeting HCAHPS exclusion criteria (e.g., pediatric patients, primary psychiatric diagnoses, prisoners, deceased patients, and patients discharged to hospice, nursing homes, or skilled nursing facilities) (21). We compared survey responses across all aspects of the hospital stay for inpatients aged 18 years and older. We compared all domains of PEX between patients aged 18 to 21 years (group 1), 22 to 25 years (group 2), and 26 + years (group 3). We divided emerging adulthood into groups 1 (early emerging adults, ages 18-21) and 2 (late emerging adults, ages 22-25) to better evaluate the PEX of emerging adults who recently transitioned to adult care in contrast to those closer to established adulthood. Finally, the scores for each domain were compared to a dataset of Press Ganey national clients with government ownership, federal & nonfederal, and 300 + beds, excluding stand-alone pediatric facilities. Our domains were then assigned a percentile ranking (titled “Press Ganey percentile”) to demonstrate a comparison of our PEX scores to the PG national clients’ results.

Data Analysis

We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine if any of the age groups differed from one another significantly, following by a series of 2 tailed t-tests comparing group 1 with group 2, group 1 with group 3, and group 2 with group 3. A Bonferroni correction factor was applied to the t-test results to adjust for potential multiplicity. A P-value of < .05 was considered significant.

This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB). The IRB exempted the protocol from needing informed consent.

Results

From October 1, 2015, through September 30, 2019, patient experience surveys were delivered to 124 339 patients, with an 11.3% response rate, resulting in a cohort of 14 050 patients. Patients discharged from October 1, 2015, to September 30, 2019, had a mean age of 43.0 (SD 17), were 62.9% female, 68.4% White, 27.0% Black, and 53.8% Hispanic with 62.2% Medicaid and Medicare and 30.5% self-pay and charity (Supplemental Table 1). There were 424 (3%) PEX surveys from 18 to 21 years old, 737 (5.2%) surveys from 22 to 25 years old, and 12 889 (91.7%) surveys from patients aged 26 and older. The overall PEX rating was worse for 18 to 21 years old (85.6, 37th percentile) when compared to both 22 to 25 years old (87.2, 63rd percentile, P = .029) and patients 26 and older (87.5, 75th percentile, P = .004) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient Experience by Age Group: Overall and With Staff, Physicians, Visitors, and Family.

| Ages 18 to 21 | Ages 22 to 25 | Ages 26 + | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | N | % tile | Mean (SD) | N | % tile | Mean (SD) | N | % tile | P value | |

| Overall | 85.6 (14.4) | 424 | 37.0 | 87.2 (12.8) | 737 | 63.0 | 87.5 (13.3) | 12 889 | 75.0 | .014 |

| Nurse section | 87.2 (17.3) | 409 | 17.0 | 88.7 (15.6) | 712 | 30.0 | 88.8 (16.3) | 12 496 | 31.0 | .148 |

| Friendliness/courtesy of the nurses | 89.9 (17.5) | 407 | 19.0 | 90.4 (16.5) | 710 | 21.0 | 91.7 (15.8) | 12 321 | 25.0 | .010 |

| Promptness response to call | 83.6 (22.1) | 406 | 16.0 | 84.9 (20.8) | 690 | 25.0 | 84.9 (21.2) | 11 847 | 26.0 | .478 |

| Nurses’ attitude toward requests | 86.3 (19.8) | 403 | 13.0 | 88.6 (18.5) | 699 | 21.0 | 88.8 (18.2) | 12 131 | 23.0 | .026 |

| Attention to special/personal needs | 87.0 (20.1) | 405 | 17.0 | 89.0 (17.5) | 701 | 60.0 | 88.4 (18.7) | 12 123 | 45.0 | .224 |

| Nurses kept you informed | 87.6 (19.2) | 408 | 32.0 | 89.6 (17.1) | 704 | 68.0 | 88.8 (18.4) | 12 195 | 51.0 | .215 |

| Skill of the nurses | 89.0 (18.4) | 406 | 13.0 | 90.3 (16.3) | 701 | 26.0 | 90.7 (16.6) | 12 198 | 30.0 | .112 |

| Visitors and family section | 88.0 (17.8) | 417 | 49.0 | 88.3 (16.4) | 715 | 52.0 | 91.2 (14.9) | 12 270 | 95.0 | <.001 |

| Accommodations & comfort visitors | 87.0 (19.5) | 416 | 72.0 | 88.0 (17.8) | 710 | 81.0 | 90.9 (16.0) | 12 178 | 99.0 | <.001 |

| Staff attitude toward visitors | 88.9 (18.7) | 415 | 17.0 | 88.5 (17.7) | 711 | 14.0 | 91.7 (15.3) | 12 044 | 70.0 | <.001 |

| Physician section | 86.1 (17.4) | 415 | 20.0 | 87.8 (16.2) | 727 | 42.0 | 89.0 (16.3) | 12 667 | 67.0 | <.001 |

| Time physician spent with you | 82.3 (20.9) | 412 | 24.0 | 84.8 (19.0) | 724 | 66.0 | 85.5 (19.6) | 12 519 | 79.0 | .004 |

| Physician concern questions/worries | 85.3 (19.2) | 412 | 18.0 | 86.4 (19.4) | 720 | 24.0 | 88.2 (18.6) | 12 393 | 64.0 | .001 |

| Physician kept you informed | 86.9 (19.7) | 410 | 45.0 | 87.8 (18.9) | 721 | 69.0 | 88.5 (18.7) | 12 404 | 81.0 | .157 |

| Friendliness/courtesy of physician | 88.6 (18.1) | 411 | 15.0 | 90.3 (16.9) | 721 | 43.0 | 91.6 (15.9) | 12 425 | 68.0 | <.001 |

| Skill of physician | 88.5 (16.5) | 408 | 3.0 | 89.5 (17.0) | 710 | 6.0 | 91.9 (15.8) | 12 301 | 36.0 | <.001 |

| Baby's doctor concern question/worries* | 88.6 (17.8) | 318 | – | 90.6 (15.5) | 575 | – | 91.7 (15.2) | 2972 | – | .002 |

| Baby's doctor kept you informed* | 89.1 (18.1) | 318 | – | 91.1 (15.1) | 576 | – | 92.6 (14.5) | 2966 | – | <.001 |

| Personal issues section | 85.4 (18.5) | 418 | 27.0 | 87.0 (15.6) | 731 | 46.0 | 86.9 (16.9) | 12 716 | 45.0 | .197 |

| Staff concern for your privacy | 86.3 (19.4) | 414 | 17.0 | 87.5 (16.8) | 718 | 24.0 | 88.5 (17.4) | 12 466 | 42.0 | .016 |

| How well your pain was controlled | 86.2 (19.9) | 412 | 39.0 | 88.1 (17.4) | 722 | 67.0 | 87.4 (19.2) | 12 105 | 54.0 | .274 |

| Staff addressed emotional needs | 83.7 (21.9) | 410 | 16.0 | 85.9 (19.0) | 720 | 32.0 | 86.4 (19.7) | 12 068 | 41.0 | .021 |

| Response concerns/complaints | 84.9 (21.0) | 406 | 32.0 | 85.5 (19.9) | 714 | 41.0 | 85.6 (20.7) | 11 840 | 43.0 | .795 |

| Staff include decisions regarding treatment | 86.3 (20.8) | 409 | 37.0 | 87.9 (17.3) | 719 | 78.0 | 87.0 (19.7) | 12 069 | 49.0 | .366 |

| Overall personnel section | 88.6 (18.9) | 416 | 23.0 | 90.4 (15.9) | 733 | 55.0 | 91.1 (16.4) | 12 555 | 61.0 | .006 |

| Staff worked together care for you | 89.3 (18.6) | 414 | 32.0 | 90.6 (15.8) | 733 | 51.0 | 90.7 (17.1) | 12 464 | 52.0 | .259 |

| Likelihood recommending hospital | 87.4 (21.8) | 415 | 17.0 | 89.6 (18.9) | 728 | 56.0 | 91.0 (18.5) | 12 359 | 65.0 | <.001 |

| Overall rating of care given | 89.2 (19.5) | 412 | 25.0 | 90.9 (16.7) | 728 | 57.0 | 91.9 (16.6 | 12 342 | 70.0 | .002 |

*Indicates custom questions respective to type of service received.

Patient experience with staff and hospital care processes is shown in Table 1. Early emerging adults reported a worse overall experience with their nurses than established adults (17th vs 31st percentile, P = .02). Early emerging adults also rated their nurses’ attitude towards their requests (13th percentile) as worse than established adults (23rd percentile, P = .006).

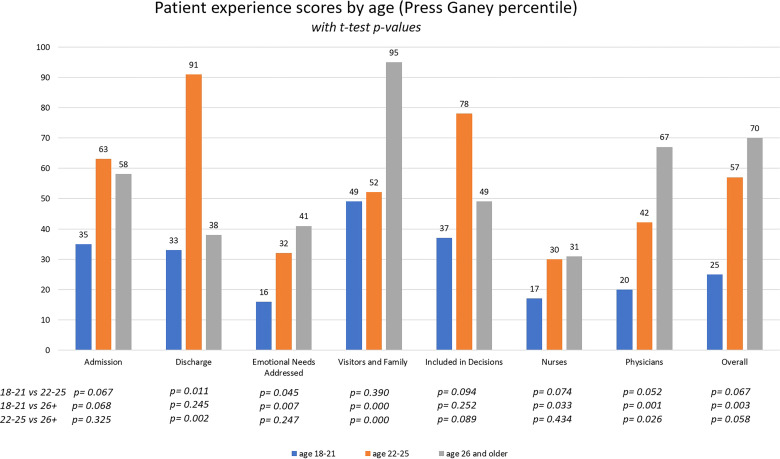

Regarding their experience with physicians, early emerging adults reported worse scores than established adults (86.1, 20th percentile vs 89.0, 67th percentile, P < .001) (Figure 1). In the 3 physician domains of “answered your questions and addressed your concerns,” “friendliness and courtesy,” and “perceived skill,” early emerging adults scored lower than established adults (P < .05 for each domain).

Figure 1.

Patient experience scores by age (Press Ganey percentile).

Early emerging adults also had a markedly worse perception of their family and visitors’ experience, rating “overall experience,” “accommodation and comfort,” and “staff attitudes” all worse than established adults (P < .001 for all domains). Early emerging adults scored staff attitudes toward visitors in the 17th percentile as compared to the 70th percentile for established adults (P < .05).

Early emerging adults also had a worse experience with the care environment and processes than their older counterparts (Table 2). Early emerging adults rated their experience with their rooms lower than established adults (85.9, 82nd percentile vs 88.3, 97th percentile, P < .001). Meals, tests, and treatments as well as discharge were all also rated lower by early emerging adults as compared to established adults.

Table 2.

Patient Experience by Age Group: Admission, Discharge, Room, Meals, Tests.

| Ages 18 to 21 | Ages 22 to 25 | Ages 26 + | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | N | %tile | Mean (SD) | N | %tile | Mean (SD) | N | %tile | P value | |

| Admission section | 85.9 (17.4) | 415 | 35 | 87.5 (17.0) | 704 | 63 | 87.2 (17.7) | 12 219 | 58 | .297 |

| Speed of admission | 84.5 (19.7) | 413 | 65 | 86.6 (19.2) | 704 | 81 | 84.9 (21.3) | 12 039 | 66 | .105 |

| Courtesy of person admitting | 87.5 (18.2) | 402 | 7 | 88.5 (17.9) | 687 | 10 | 89.9 (16.7) | 11 657 | 28 | .003 |

| Room section | 85.9 (13.8) | 418 | 82 | 87.0 (14.4) | 716 | 91 | 88.3 (14.0) | 12 502 | 97 | <.001 |

| Pleasantness of room decor | 87.3 (16.2) | 417 | 94 | 88.2 (16.5) | 713 | 95 | 90.3 (15.7) | 12 242 | 99 | <.001 |

| Room cleanliness | 88.6 (17.6) | 414 | 80 | 87.9 (19.5) | 712 | 71 | 89.0 (18.2) | 12 282 | 86 | .275 |

| Courtesy of person cleaning room | 88.3 (18.0) | 410 | 30 | 87.8 (19.6) | 706 | 29 | 89.3 (17.8) | 11 994 | 37 | .057 |

| Room temperature | 82.7 (20.4) | 404 | 49 | 85.4 (18.7) | 704 | 88 | 87.2 (18.0) | 12 031 | 92 | <.001 |

| Noise level in and around room | 83.1 (22.1) | 410 | 85 | 85.3 (19.7) | 704 | 99 | 86.4 (20.1) | 11 893 | 99 | .002 |

| Meals section | 81.1 (19.7) | 416 | 49 | 83.2 (18.3) | 713 | 73 | 81.2 (20.2) | 12 367 | 50 | .035 |

| Temperature of the food | 83.3 (21.3) | 415 | 88 | 84.4 (21.0) | 706 | 94 | 80.1 (24.3) | 12 235 | 65 | <.001 |

| Quality of the food | 73.2 (27.6) | 411 | 34 | 76.6 (26.9) | 703 | 63 | 75.2 (27.1) | 12 085 | 54 | .128 |

| Courtesy of person served food | 86.4 (19.6) | 409 | 16 | 88.7 (17.1) | 698 | 41 | 88.4 (18.0) | 11 976 | 39 | .076 |

| Tests and treatments section | 84.3 (17.9) | 415 | 20 | 85.5 (16.2) | 712 | 24 | 86.7 (16.2) | 12 467 | 47 | .003 |

| Wait time for tests or treatments | 82.7 (19.8) | 412 | 50 | 83.4 (19.2) | 701 | 62 | 84.2 (19.4) | 12 146 | 78 | .185 |

| Explanations happen during T&T | 85.4 (20.7) | 409 | 26 | 87.0 (17.5) | 699 | 56 | 87.1 (18.4) | 12 022 | 57 | .186 |

| Courtesy of person took blood | 84.3 (21.3) | 410 | 6 | 85.9 (19.6) | 704 | 14 | 87.8 (18.6) | 12 107 | 22 | <.001 |

| Courtesy of person started IV | 85.2 (22.0) | 413 | 4 | 86.3 (20.8) | 701 | 11 | 88.2 (18.8) | 12 100 | 27 | <.001 |

| Discharge section | 84.7 (17.4) | 415 | 33 | 87.1 (16.3) | 733 | 91 | 85.3 (18.0) | 12 709 | 38 | .022 |

| Extent felt ready discharge | 87.1 (20.3) | 415 | 45 | 88.7 (17.3) | 730 | 76 | 85.5 (20.6) | 12 547 | 30 | <.001 |

| Speed of discharge process | 79.5 (24.7) | 413 | 26 | 82.6 (24.0) | 726 | 77 | 82.1 (23.7) | 12 425 | 61 | .074 |

| Instructions for care at home | 87.5 (20.7) | 411 | 30 | 89.9 (18.4) | 724 | 90 | 88.6 (19.2) | 12 322 | 68 | .099 |

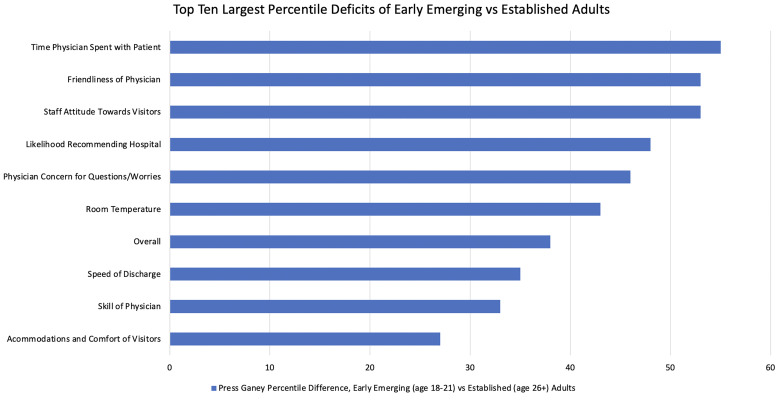

Figure 2 compares the 10 survey items with the largest PG percentile deficits from early emerging to established adults, with the top 3 items each demonstrating a greater than 50 percentile difference.

Figure 2.

Top 10 largest percentile deficits of early emerging versus established adults.

Discussion

Transitioning from pediatric to adult care, especially with a pediatric onset health condition, is a vulnerable time (4). Little is known about how emerging adults experience inpatient care differently than established adults. We found that, overall, emerging adults had worse experiences with their care than their older counterparts. While these findings held true for a broad range of domains, the greatest differences were in their experiences with staff, most notably doctors and nurses, as well as patients’ perceptions of the treatment of their friends and family members. The care environment, including the rooms, food, and decor was also scored lower by emerging adults, although these differences were not as large as those measuring experiences with staff.

Within the overall domain, our study showed a 38-percentile difference in patient experience between early emerging and established adult age groups. This finding is consistent with existing literature, which postulates that young adults may have an expectation gap during the transition from pediatric to adult healthcare, be it age-related differences in the preferred method of physician communication or distinct age-related priorities (8,9). Beresford and Stuttard (7) interviewed 18 to 25 years old patients in the United Kingdom with childhood-onset chronic diseases and noted that their inpatient hospitalizations were the worst aspect of their transition to adult health care centers. They cited several reasons, including “distress with not having parents involved, […] unmet care needs, social isolation, distress and anxiety caused by [acute illness].” The overall patient experience gap in our study was echoed across the domains of physicians, visitors and family, emotional needs, and nursing.

Emerging adults reported a substantially worse experience in all physician domains, which decreased more than any other subgroup studied. In the nursing domain, patient experience decreased from the 31st to 17th percentile when comparing established to early emerging adults. However, while physician scores increased dramatically after age 26, nursing scores remained low overall (Figure 1). The reasons for this pattern are unclear; however, patient experience with physicians improves with time spent at the bedside (22,23). Time-motion studies of adult hospitalists show that they spend 15% to 17% of their typical workday on direct patient care (24,25). In the context of a hospitalist's average census of 15 patients (26), this equates to only 7 min at bedside per patient daily. For nurses, early emerging adults noted their worst experiences in the categories of nursing attention to patient's needs and the skill of the nurses. Zamora et al (27) found that when nurses and physicians implement the “acknowledge, introduce, duration, explanation and thank you” (AIDET) model, which aims to standardize provider–patient interactions, it improves patient experience quality metrics. Braverman et al (28) also found that when medical residents receive AIDET training, Press Ganey physician communication scores improve between pre- and posttraining patient surveys. Ultimately, more research is needed to explore differences between pediatric and adult physician and nursing models.

In our study, it was noted that emerging adults had poor experiences regarding visitor accommodations (27th percentile) and staff attitudes toward visitors (53rd percentile). Pediatric hospital systems focus on family-centered care and prioritize keeping family close and available throughout hospitalization. Franck et al (29) found a positive correlation between close family accommodation throughout at least part of their hospitalization leading to an improvement in the parent's perception of the patient experience. Compared to traditional adult hospitals, pediatric hospitals often have more robust accommodations provided to families and a broader focus on family-centered care. Although low visitor and family scores in emerging adults may represent an expectation gap compared to their experiences at pediatric hospitals, it is nonetheless a potential area for improvement in adult hospitals. Further research is needed to elucidate which aspects of the visitor policies had the most negative impact, but one major difference in pediatric versus adult inpatient care that may contribute to changes in visitor experience is the practice of family-centered rounding. A study at the University of California, San Francisco by Bekmezian et al (30) demonstrated significant improvement in patient satisfaction scores after implementing appointment-based family centered rounds.

We found that emerging adults also have worse experiences in certain aspects of the hospital processes and environment, although these deficits are not as profound as those interpersonal interactions. There is no literature to inform how to improve the patient experience with the environment of care specifically for young adults, however in comparing patient experience data of an adult academic tertiary hospital before and after moving to a new clinical building with a “patient centered” design, Siddiqui et al (31) found that the environmental experiences were all improved, although this did not affect the overall PEX. This is consistent with our own findings that suggest interactions with hospital staff are the main driver of the gap in the overall inpatient experience of emerging adults.

Future Directions

The findings of this study suggest that further work be done in comparing emerging adults’ healthcare experiences to those of children and adolescents, as well as examining how race, ethnicity, financial barriers, care access, and comorbidities may affect emerging adults’ patient experience. HCAPHS was developed to “measure patients’ perspectives of hospital care” and continues to be used as an incentive for hospitals to improve the quality of care (21). This survey was originally tested and validated in a traditional adult population, and it excludes pediatric participation. As such, it is possible the values and preferences of emerging adults are not fully encompassed by traditional HCAPHS questions. While reviewing qualitative data collected from hospitalized emerging adults, a focus group comprised of hospitalists trained in both pediatrics and internal medicine discovered “thematic gaps in care including decreased family involvement” and “less attention to and support for emotional needs. (32)” Further qualitative studies examining what aspects of care this population values most are indicated.

Limitations

Due to the nature of the survey, we did not have demographic information for the patients who completed the PEX surveys included in our data retrieval. This study was limited to a single large urban academic medical center serving a vulnerable and diverse patient population. Accordingly, these findings may not be generalized to other centers. No qualitative information was obtained in the data retrieval. In addition, the voluntary nature of these surveys makes this study susceptible to participation (or nonresponse) bias (33). The smaller number of individuals in age groups 18 to 21 and 22 to 25 may have led to underpowering when comparing these 2 groups and could result in false negatives.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that emerging adults have specific needs and expectations during hospitalization which differ from those of established adults. For early emerging adults, nearly all domains showed a worse patient experience compared to patients aged 26 and older. Human interactions between patients, their families, and the healthcare system appear to play the primary role in emerging adults’ substantially worse experiences. This differs from factors traditionally thought to be tied to experiences, such as food and ambiance. To meaningfully improve patient experience and health outcomes, our data suggest that hospitals should focus on improving the interpersonal interactions between hospital staff and emerging adults and continue to explore the distinct values and preferences of this patient population.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221133652 for The Inpatient Experience of Emerging Adults: Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult Care by Daniel Driver, Michelle Berlacher, Stephen Harder, Nicole Oakman, Maryam Warsi and Eugene S Chu in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and cooperation received from the following individuals at Parkland Health, Dallas, Texas, USA: Lonnie Roy, Ph.D., for assistance with Press Ganey dataset collection and Margaret Hinshelwood, Ph.D., for assistance with demographic data collection. The abovementioned contributors received no compensation for their work other than their usual salary. They have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

Footnotes

Author Participation: All authors participated in writing the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this case was obtained from our Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Daniel Driver https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9171-7511

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: All procedures in this study were conducted in accordance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocols.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent for patient information to be published in this article was not obtained because it was deemed unnecessary by our institutional review board.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Garvey KC, Markowitz JT, Laffel LM. Transition to adult care for youth with type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2012;12(5):533-41. DOI: 10.1007/s11892-012-0311-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin CE., Jr. Young adults are worse off than adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):405-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park MJ, Paul Mulye T, Adams SH, et al. The health status of young adults in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(3):305-17. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, et al. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;115(17):3447-52. DOI: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tassiopoulos K, Huo Y, Patel K, et al. Healthcare transition outcomes among young adults with perinatally acquired human immunodeficiency virus infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(1):133-41. DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciz747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batbaatar E, Dorjdagva J, Luvsannyam A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health. 2017;137(2):89-101. DOI: 10.1177/1757913916634136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beresford B, Stuttard L. Young adults as users of adult healthcare: experiences of young adults with complex or life-limiting conditions. Clin Med (Lond). 2014;14(4):404-8. DOI: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-4-404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hargreaves DS, Sizmur S, Viner RM. Do young and older adults have different healthcare priorities? Evidence from a national survey of English inpatients. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(5):528-32. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hargreaves DS, Viner RM. Children's and young people’s experience of the National Health Service in England: a review of national surveys 2001–2011. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97(7):661-6. DOI: 10.1136/archdischild-2011-300603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. Am Psychol. 2000;55(5):469-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hochberg ZE, Konner M. Emerging adulthood, a pre-adult life-history stage. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:918. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellison-Barnes A, Johnson S, Gudzune K. Trends in obesity prevalence among adults aged 18 through 25 years, 1976–2018. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2073-4. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2021.16685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bull C, Byrnes J, Hettiarachchi R, et al. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of patient-reported experience measures. Health Serv Res. 2019;54(5):1023-35. DOI: 10.1111/1475-6773.13187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed F, Burt J, Roland M. Measuring patient experience: concepts and methods. Patient. 2014;7(3):235-41. DOI: 10.1007/s40271-014-0060-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):188-95. DOI: 10.1161/circoutcomes.109.900597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, et al. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient–provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):661-5. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiMatteo MR. Enhancing patient adherence to medical recommendations. JAMA. 1994;271(1):79–83.. DOI: 10.1001/jama.271.1.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826-34. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Associates PG. I. Inpatient (IN) Survey Psychometrics Report. 2010.

- 21.Healthcare CfMMSAf and Quality. Ra. The HCAHPS Survey - Frequently Asked Questions, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/hospitalqualityinits/downloads/hospitalhcahpsfactsheet201007.pdf, 2021.

- 22.Gross DA, Zyzanski SJ, Borawski EA, et al. Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(2):133-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patterson BM, Eskildsen SM, Clement RC, et al. Patient satisfaction is associated with time with provider but not clinic wait time among orthopedic patients. Orthopedics. 2017;40(1):43-8. DOI: 10.3928/01477447-20161013-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim CS, Lovejoy W, Paulsen M, et al. Hospitalist time usage and cyclicality: opportunities to improve efficiency. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):329-34. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tipping MD, Forth VE, O'Leary KJ, et al. Where did the day go?—a time-motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):323-8. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michtalik HJ, Pronovost PJ, Marsteller JA, et al. Identifying potential predictors of a safe attending physician workload: a survey of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(11):644-6. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamora R, Patel M, Doherty B, et al. Influence of AIDET in the improving quality metrics in a small community hospital—before and after analysis. J Hosp Adm. 2015;4(3):35–8. DOI: 10.5430/jha.v4n3p35 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braverman AM, Kunkel EJ, Katz L, et al. Do I buy it? How AIDET™ training changes residents’ values about patient care. J Patient Exp. 2015;2(1):13-20. DOI: 10.1177/237437431500200104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franck LS, Ferguson D, Fryda S, et al. The child and family hospital experience: is it influenced by family accommodation? Med Care Res Rev. 2015;72(4):419-37. DOI: 10.1177/1077558715579667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bekmezian A, Fiore DM, Long M, et al. Keeping time: implementing appointment-based family-centered rounds. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2019;4(4):e182. DOI: 10.1097/pq9.0000000000000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siddiqui ZK, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, et al. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-71. DOI: 10.1002/jhm.2297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berlacher MC ES, Walsh J, Alikhan MK, Hoffman D, Oakman N, Waters A. Opportunities To Improve The Care Of Hospitalized Young Adults. Abstract published at Hospital Medicine 2020, Virtual Competition. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 2020.

- 33.Compton J, Glass N, Fowler T. Evidence of selection bias and non-response bias in patient satisfaction surveys. Iowa Orthop J. 2019;39(1):195-201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-jpg-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735221133652 for The Inpatient Experience of Emerging Adults: Transitioning From Pediatric to Adult Care by Daniel Driver, Michelle Berlacher, Stephen Harder, Nicole Oakman, Maryam Warsi and Eugene S Chu in Journal of Patient Experience