Vertebrates have evolved a system of pathogen recognition which depends on the generation of a vast repertoire of immunoglobulins and T-cell receptor (TCR) specificities expressed on individual B and T lymphocytes, respectively. In contrast to B lymphocytes, which recognize intact proteins, T lymphocytes detect short peptides produced by a proteolytic machinery and presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules at the cell surface (52). Through antigen processing, T lymphocytes are able to detect foreign or mutated peptides synthesized by infected cells or tumor cells. There is now a large body of evidence showing that T lymphocytes play an important role in controlling infections and tumor growth in vivo.

T lymphocytes operate by regulating the immune response and carrying out effector functions. T cells which express CD8 molecules have the capacity to lyse directly the target cells. These cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are thought to be among the major effectors in tumor rejection. A subset of CD4+ T lymphocytes is specialized in regulating the immune response via cytokine secretion and activation of the antigen-presenting cells. It has been shown, in both mice and humans, that CD4+ T cells are mandatory for generating an efficient and long-lasting cytotoxic CD8 T-cell response (2, 39).

Chronic infection and development of tumors occur despite the remarkably sensitive recognition of T lymphocytes. Mechanisms of escape from T-cell destruction include inadequate antigen presentation and T-lymphocyte unresponsiveness (16). For example, tumor growth results more often from ineffective priming than from the absence of tumor-specific T cells (28, 43). During the past 15 years, the molecular identification of tumor epitopes recognized by T lymphocytes (4, 44) has allowed the design of novel immunotherapeutic strategies aimed at priming and expanding tumor-specific T cells (15, 51). It is likely that long-term protection requires the mobilization of the patient's own immune system. Therefore, quantitative and qualitative assessments of the antigen-specific immune response to tumor vaccination protocols are essential in understanding any correlation with clinical outcome.

Until recently, chromium release assays and limiting-dilution analyses were the only techniques commonly used to measure specific T-cell responses, although they are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and not very sensitive (10, 34). In the past 4 or 5 years, new methods have been developed to analyze complex T-lymphocyte repertoires and to assess T-cell specificity and functionality (14, 42). These new methods are more sensitive or provide more information than previously used assays. Importantly, some of these new techniques allow direct ex vivo analysis of T cells without in vitro amplification, thus providing a more accurate picture of the in vivo immune response.

In this review, we describe some of the most widely used techniques for immune monitoring of specific T-cell responses. These various assays can be schematically divided into functional assays, which measure the secretion of a particular cytokine (ELISPOT and intracellular cytokines); assays which assess the specificity of the T cells irrespective of their functionality and which are based on structural features of the TCR (tetramers and immunoscope); and assays aimed at detecting T-cell precursors by amplifying cells that proliferate in response to antigenic stimulation. The sensitivity and immunological relevance of these various methods are discussed. Major findings and future applications in basic and clinical immunology are also presented.

FUNCTIONAL ASSAYS

ELISPOT. (i) Technique description.

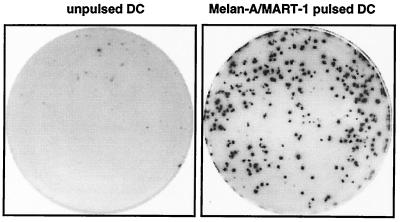

The ELISPOT (enzyme-linked immunospot) technique detects T cells that secrete a given cytokine (e.g., gamma interferon [IFN-γ]) in response to an antigenic stimulation (19). T cells are cultured with antigen-presenting cells in wells which have been coated with anti-IFN-γ antibodies. The secreted IFN-γ is captured by the coated antibody and then revealed with a second antibody coupled to a chromogenic substrate. Thus, locally secreted cytokine molecules form spots, with each spot corresponding to one IFN-γ-secreting cell. The number of spots allows one to determine the frequency of IFN-γ-secreting cells specific for a given antigen in the analyzed sample. An example of spots forming cells detected by ELISPOT assay is shown in Fig. 1. The ELISPOT assay has also been described for the detection of tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (21, 24), and even granzyme B-secreting lymphocytes.

FIG. 1.

Melan-A/MART-1-specific IFN-γ-producing T cells detected by ELISPOT assay. A T-cell population containing Melan-A-MART-1-specific CTL was incubated with unpulsed or Melan-A/MART-1-pulsed dendritic cells (DC) in a 96-well plate precoated with anti-IFN-γ antibody. IFN-γ-secreting cells were revealed after 20 h of culture. Of 1,000 T cells, 280 are specific for HLA-A2/Melan-A.

(ii) Immunological relevance.

This assay is remarkably well adapted for monitoring immune responses to vaccines, since it is highly sensitive and versatile, can be performed directly ex vivo, and uses a relatively small number of T cells. Cells secreting as few as 100 molecules can be detected by taking advantage of the high concentration of cytokines in the immediate environment of the activated T cells. However, the ELISPOT assay detects preferentially effector T cells. An in vitro stimulation for several days may be required to reveal central memory cells (46). The frequency of antigen-specific T cells can also be underestimated if some cells are nonfunctional or secrete different cytokines. The use of tetramers (see below) may be better adapted to this type of situation. The simultaneous detection of two cytokines has also been described (37, 49) and could be particularly useful for evaluating immune deviation. The amount of secreted cytokines is not determined in ELISPOT assays. However, a rough estimate can be obtained by using computer-assisted image analysis (18) to measure spot density and area. By titrating the antigen, the ELISPOT assay can also provide some hints on the relative avidity of the T cells, and this information may be important for determining anti-tumor responses (13).

Flow cytometric analyses of intracellular cytokines. (i) Technique description.

Until recently, cytokine secretion by T cells was analyzed essentially by enzyme-linked immunoassays. This assay measures the cytokine content in culture supernatants but provides no information on the number of T cells that actually secrete the cytokine. When T cells are treated with inhibitors of secretion such as monensin or brefeldin A, they accumulate cytokines within their cytoplasm upon antigen activation. After fixation and permeabilization of the lymphocytes, intracellular cytokines can be quantified by cytometry (22). This technique allows the determination of the cytokines produced, the type of cells that produce these cytokines, and the quantity of cytokine produced per cell.

(ii) Immunological relevance.

Intracellular cytokine measurement usually requires larger sample volumes than does the ELISPOT assay. However, it remains the only assay that determines simultaneously the type of cytokine produced by a single cell and the phenotype of such a cell. In addition, the combination of cell surface marker and/or tetramer labeling with intracellular cytokine measurement allows the detection of rare cell populations (27, 28).

STRUCTURAL ASSAYS

Tetramers. (i) Technique description.

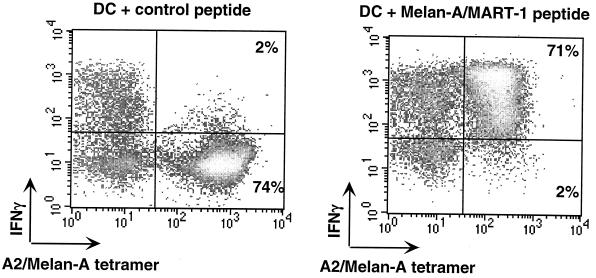

T cells recognize short peptides presented by MHC molecules through their clonotypic TCR. It is therefore conceivable to use fluorescent MHC-peptide complexes that bind the TCR to visualize antigen-specific T cells. However, the interaction between TCR and MHC-peptide complexes is too weak for stable binding: the Ka is ca. 105 M−1 with a dissociation constant of <1 min (31). Such a weak affinity can be compensated for by using fluorescent multimers of MHC-peptide complexes that increase the overall avidity for the T cell. In fact, dimers or, even better, tetramers of MHC class I-peptide complexes have been used in cytometry to enumerate, characterize, and purify peptide-specific CD8 cells (1, 12, 33). The heavy and light chains of the MHC are produced in Escherichia coli, solubilized in urea, and refolded in vitro in the presence of high concentrations of the antigenic peptide. The refolded complexes are purified by gel filtration, and a single biotin is added at the C-terminal end of the heavy chain using the bacterial BirA enzyme. Incubation with fluorescent streptavidin yields tetramers which can be used like any clonotypic antibody. An example of MHC tetramer staining is shown in Fig. 2. Tetramers of MHC class II molecules have also been produced and used to analyze CD4+ T-cell responses (11, 35).

FIG. 2.

Quantification of functional epitope-specific T cells using MHC tetramers and IFN-γ intracellular staining. T cells were incubated for 6 h with dendritic cells (DC) pulsed with the Melan-A/MART-1 peptide or an irrelevant (MAFlu) peptide. Brefeldin A was added for the last 3 h of incubation. IFN-γ produced by Melan-A-MART-1-specific T cells was quantified by flow cytometry after gating on CD8+ cells.

(ii) Immunological relevance.

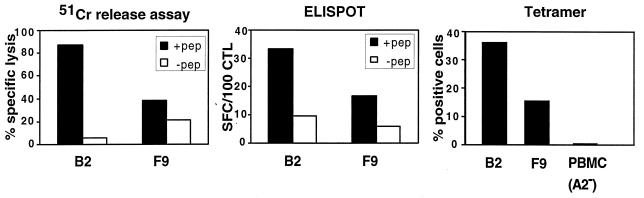

T-cell frequencies measured by MHC tetramers are often 10 times higher than those measured by more conventional techniques (33). Since MHC tetramer binding only requires proper TCR expression, this assay provides no clues as to whether the labeled T cells are functional. In addition, the analysis is restricted to already-identified T-cell epitopes. In fact, the most interesting feature of tetramers is that they allow visualizing all specific T cells, whether these are precursors or effectors, functional or anergic. A good correlation between the cytotoxic activity and the frequency of epitope-specific T cells determined by MHC tetramer and ELISPOT is observed when T cells are functional (Fig. 3). T cells labeled with MHC tetramers can be further characterized by surface marker analysis or functional assays such as intracellular cytokine detection (Fig. 2). Tetramer-positive cells can also be cloned after purification by flow cytometry or using beads coated with MHC-peptide multimers, as recently described (3). This type of purification allows rapid enrichment of epitope-specific T cells, avoiding the need for several cycles of in vitro stimulation.

FIG. 3.

Correlation between the cytotoxic activity and the frequency of epitope-specific T cells detected by MHC tetramers and ELISPOT assay. The cytotoxic activity of two T-cell lines, B2 and F9, against autologous B-EBV cells pulsed or not pulsed with Melan-A/MART-1 peptide was measured in a 4-h 51Cr release assay. The frequency of Melan-A/MART-1-specific CTL in B2 and F9 cells was determined by ELISPOT assay after stimulation with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells and by HLA-A2/Melan-A tetramer staining after gating on CD8+ cells. SFC, spot-forming cell; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cells.

Another concern about MHC tetramers refers to the relationship between TCR affinity required for T-cell activation and that necessary for staining with MHC tetramers. More data are probably required to fully answer this question.

Immunoscope. (i) Technique description.

T-cell repertoire diversity is created during the assembly of variable-region gene segments by a process of somatic DNA rearrangement known as V(D)J recombination. The third hypervariable regions (CDR3) of both α and β TCR chains result from these recombination events, and their lengths are therefore highly variable. Using V- and C-specific primers, CDR3 regions can be amplified and their size distribution analyzed by electrophoresis (immunoscope) (9, 38). Several dozen BV and 4 to 5 BJ gene segments coding for the β chain are known in mice and humans, so the combination of all possible V and J segments with all possible CDR3 lengths represents more than 2,000 possibilities that can be analyzed in one sample. Upon immunization, a few T-cell clones are amplified. All cells belonging to the same clone harbor the same CDR3. Interestingly, in some situations, it has even been found that most clones specific for the same MHC-peptide complex displayed the same BV segment and the same CDR3 length (5, 8). Expansion of these T-cell clones will therefore result in a significant perturbation of the signal measured by the immunoscope. This approach has been used to visualize and quantify clonal expansions in both human and mouse. As for any PCR-based technology, the immunoscope method is remarkably sensitive, and a single specific T cell can be detected out of 2 × 105 cells.

(ii) Immunological relevance.

Immunoscope provides information on the composition of the T-cell repertoire selected during an immune response. Combined with MHC tetramer staining, it is also possible to evaluate the diversity of epitope-specific T-cell clones that expand upon antigenic challenge (6). The combination of these two sensitive techniques allows detailed analysis of the T-cell repertoire without in vitro amplification.

DETECTION OF PRECURSOR T CELLS

Precursor T cells do not carry out any effector function but can proliferate upon antigen encounter. T-cell proliferation is usually assessed by measuring incorporation of a radioactive tracer ([3H]thymidine), which gives the total amount of DNA synthesized in a bulk culture but provides no information on the actual frequency of specific T cells. A fluorescent dye such as bromodeoxyuridine, which intercalates into replicating chromosomes, has been widely used but is not very sensitive because of the basal T-cell proliferation. In addition, it is not possible to purify the specific live cells for further characterization.

The capacity of the precursor cells to proliferate allows amplification of an antigen-specific population and determination of the precursor frequency by limiting-dilution analysis and, more recently, by flow cytometry methods using fluorescent dyes to stain the cell membrane or cytoplasm (53).

Flow cytometry methods to estimate precursor frequency. (i) Technique description.

Cell samples containing specific precursors are first stained with a fluorescent dye such as carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) or PKH26, a long-chain aliphatic dye. CFSE binds to amino groups of intracellular proteins, while PKH26 becomes integrated into the lipid membrane. Upon cell division, cells become 2 times less fluorescent at each division due to partition of the cell dye between daughter cells. The number of cell cycles is directly deduced from the intensity of fluorescence. The initial frequency of precursor T cells can then be calculated from the distribution of fluorescence observed at the end of the experiment (usually 4 to 15 days) (17).

(ii) Immunological relevance.

The assessment of proliferation responses based on flow cytometry is advantageous over methods measuring incorporation of radioactive thymidine since CFSE and PKH26 allow the simultaneous detection of specific T cells, e.g., by tetramer staining. Obviously, T cells incapable of proliferation, such as anergic cells, will not be detected by these methods. In addition, it has been reported that CFSE, but not PKH26, may interfere with cell proliferation.

SOME IMMUNOLOGICAL QUESTIONS RELATED TO T CELLS

(i) Dynamics of the T-cell repertoire.

The techniques discussed above have provided crucial information on the dynamics of T-cell immune responses. The use of tetramers has revealed that epitope-specific T cells can represent a high proportion of the peripheral T-cell pool during a primary immune response. In several mouse models, up to 30 to 70% of CD8+ splenocytes may be specific for a single epitope during the acute phase of a viral infection or tumor rejection (6, 33). Such epitope dominance has also been observed in autoimmune models: in a prediabetic nonobese diabetic mouse, for instance, >70% of the T cells infiltrating the pancreas were found to be specific for one single epitope derived from insulin (55). The observation that most expanded T cells are antigen specific has led to a reevaluation of the concept of bystander activation. In infected humans, virus-specific T cells have been detected in peripheral blood using MHC tetramers and ELISPOT assay but at much lower frequencies (1, 7, 26, 56). During acute infection by hepatitis C virus, a high frequency of activated specific T cells are detected early during infection (up to 7%), although these cells have impaired IFN-γ secretion capacity as assessed by ELISPOT assay and intracellular staining (27). In several situations, a surprisingly limited number of T-cell clones contributes significantly to the immune repertoire (6, 32). By combining tetramers, the immunoscope method, and extensive CDR3 sequencing, we were able to compare the tumor-specific repertoire in the same animal before and after the tumor graft (6). Such studies have provided further insights into the process of T-cell recruitment and amplification during primary or secondary immune responses.

(ii) Characterization of T cells in immunopathological situations.

This new approach has also been used recently to characterize T cells associated with immunopathology. In particular, tetramers have been broadly used to analyze and purify tumor-specific T cells in cancer patients. CD8+ T cells specific for Melan-A/MART-1 or tyrosinase have been detected in the peripheral blood of patients with metastatic melanoma (28). In one patient, the frequency of tyrosinase-specific cells represented up to 2.2% of circulating CD8+ T cells. However, the frequencies of Melan-A/MART-1-specific CD8+ T cells in most cases are similar in healthy individuals and in melanoma patients (0.07%) but augmented in patients with autoimmune vitiligo (36, 40). T-cell responses against other tumor antigens, such as NY-ESO-1, have also been detected in melanoma patients, although in vitro sensitization of T cells was required for ELISPOT or tetramer staining (20). The fact that tumor-specific T-cell responses are detectable in cancer patients suggests that these antigens may represent good candidates for tumor vaccines. In addition, patient prescreening may help to identify those who could possibly benefit from immunotherapy treatment.

The existence of tumor progression or chronic infection despite the presence of specific lymphocytes highlights the importance of the functional characterization of these T cells. ELISPOT and intracellular cytokine detection on tetramer-stained cells are therefore very important tools for performing more accurate immune monitoring during a given immunotherapy. Melan-A/MART-1- and tyrosinase-specific T cells display a naive phenotype in healthy individuals, contrasting with the presence of both naive and effector/memory specific T cells in melanoma patients (28, 40). Interestingly, a population of T cells presenting both naive and memory cell surface markers was detected in some melanoma patients (28). These cells lacked functional activity in vitro, even after stimulation with mitogens. Furthermore, signaling defects affecting the expression of the CD3-ζ chain of the TCR complex have been observed in T cells from patients with various malignancies (29, 54). Taken together, these studies document the severe immune defects frequently associated with human malignancies and suggest that effective treatments may require strategies aimed at breaking tolerance.

(iii) Immune monitoring in clinical trials.

Monitoring tumor-specific T cells in clinical trials is essential to optimize vaccine strategies. For instance, whereas the frequency of tumor-specific T cells was increased following subcutaneous and intradermal immunizations with MAGE-3A1 peptide-pulsed dendritic cells, a decline was observed following intravenous injection (50), suggesting that some routes of administration may be more efficient than others. Other questions, such as what are the most immunogenic tumor antigens, the optimal regimen, and the best formulation, can be addressed in short trials that include a limited number of patients and use appropriate immune monitoring methods.

Tumor regressions without detection of tumor-specific CTL have been observed in several trials, stressing again the lack of sensitivity of the 51Cr release assay and the need for improved techniques (30). Discrepancies between successful priming and the lack of a clinical response have also been reported in several clinical studies (23, 45, 47), for instance, following vaccination with tumor antigen-derived peptide. However, most of these patients were in an advanced stage of disease. Such results may therefore suggest that targeting a single epitope is probably not sufficient for the efficient destruction of tumors, especially in patients with a high tumor burden. In another study, 15 patients with resected melanoma received four injections of a polyvalent vaccine specific for MAGE-3 and Melan-A/MART-1: patients who responded as determined by ELISPOT assay (9 out of 15) remained recurrence-free for 12 to 21 months, while nonresponders relapsed after 3- to 5 months (41). Furthermore, induction of MUC1-reactive CTL by vaccination with hybrids of autologous tumor and allogeneic dendritic cells was recently described in two patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma and was associated with tumor regression (25).

We are currently monitoring T-cell responses induced in prostate cancer patients following vaccination with dendritic cells loaded with recombinant prostate-specific antigen (PSA). The immune response is assessed before, during, and after vaccination. A combination of ELISPOT, intracellular staining, proliferation assays, and the MHC tetramer method is used. PSA-specific responses have been observed in some patients. It will be important to see whether these immune responses correlate with the clinical outcome of vaccinated patients. The duration of these immune responses will be monitored carefully in order to determine whether further injections are required to provide long-term protection.

CONCLUSION

The development of sensitive assays for analyzing T-cell responses in animals and humans has led to important discoveries in basic and clinical immunology. Although none of these assays is sufficient by itself, an accurate picture of the in vivo immune system is obtained by combining several techniques. As recently suggested by Shankar and Salgaller (48), it is likely that in the near future immune monitoring methods, if correlated with clinical response, may serve as surrogate indicators of treatment status and/or clinical outcome. Such profound changes may considerably accelerate the development of new treatments of cancers and chronic diseases, providing patients with potent therapeutic alternatives devoid of the high toxicity and side effects associated with standard therapies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altman J D, Moss P A H, Goulder P J R, Barouch D H, McHeyzer-Williams M G, Bell J I, McMichael A J, Davis M M. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett S R, Carbone F R, Karamalis F, Miller J F, Heath W R. Induction of a CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocyte response by cross-priming requires cognate CD4+ T cell help. J Exp Med. 1997;186:65–70. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.1.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodinier M, Peyrat M-A, Tournay C, Davodeau F, Romagne F, Bonneville M, Lang F. Efficient detection and immunomagnetic sorting of specific T cells using multimers of MHC class I and peptide with reduced CD8 binding. Nat Med. 2000;6:707–710. doi: 10.1038/76292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boon T, van der Bruggen P. Human tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1996;183:725–729. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bousso P, Casrouge A, Altman J D, Haury M, Kanellopoulos J, Abastado J P, Kourilsky P. Individual variations in the murine T cell response to a specific peptide reflect variability in naive repertoires. Immunity. 1998;9:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bousso P, Levraud J P, Kourilsky P, Abastado J P. The composition of a primary T cell response is largely determined by the timing of recruitment of individual T cell clones. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1591–1600. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.10.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callan M F, Tan L, Annels N, Ogg G S, Wilson J D, O'Callaghan C A, Steven N, McMichael A J, Rickinson A B. Direct visualization of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the primary immune response to Epstein-Barr virus in vivo. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1395–1402. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casanova J L, Maryanski J L. Antigen-selected T-cell receptor diversity and self-nonself homology. Immunol Today. 1993;14:391–394. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90140-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cochet M, Pannetier C, Regnault A, Darche S, Leclerc C, Kourilsky P. Molecular detection and in vivo analysis of the specific T cell response to a protein antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2639–2647. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulie P G, Somville M, Lehmann F, Hainaut P, Brasseur F, Devos R, Boon T. Precursor frequency analysis of human cytolytic T lymphocytes directed against autologous melanoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1992;50:289–297. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910500220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford F, Kozono H, White J, Marrack P, Kappler J. Detection of antigen-specific T cells with multivalent soluble class II MHC covalent peptide complexes. Immunity. 1998;8:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dal Porto J, Johansen T E, Catipovic B, Parfiit D J, Tuveson D, Gether U, Kozlowski S, Fearon D T, Schneck J P. A soluble divalent class I major histocompatibility complex molecule inhibits alloreactive T cells at nanomolar concentrations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6671–6675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dhodapkar M V, Krasovsky J, Steinman R M, Bhardwaj N. Mature dendritic cells boost functionally superior CD8(+) T-cell in humans without foreign helper epitopes. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:9–14. doi: 10.1172/JCI9051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dranoff G. Interpreting cancer vaccine clinical trials. J Gene Med. 1999;1:80–83. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-2254(199903/04)1:2<80::AID-JGM20>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernandez N, Duffour M T, Perricaudet M, Lotze M T, Tursz T, Zitvogel L. Active specific T-cell-based immunotherapy for cancer: nucleic acids, peptides, whole native proteins, recombinant viruses, with dendritic cell adjuvants or whole tumor cell-based vaccines. Principles and future prospects. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1998;4:53–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilboa E. How tumors escape immune destruction and what we can do about it. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:382–385. doi: 10.1007/s002620050590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Givan A L, Fisher J L, Waugh M, Ernstoff M S, Wallace P K. A flow cytometric method to estimate the precursor frequencies of cells proliferating in response to specific antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1999;230:99–112. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herr W, Linn B, Leister N, Wandel E, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K H, Wolfel T. The use of computer-assisted video image analysis for the quantification of CD8+ T lymphocytes producing tumor necrosis factor alpha spots in response to peptide antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1997;203:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herr W, Schneider J, Lohse A W, Meyer zum Buschenfelde K H, Wolfel T. Detection and quantification of blood-derived CD8+ T lymphocytes secreting tumor necrosis factor alpha in response to HLA-A2.1-binding melanoma and viral peptide antigens. J Immunol Methods. 1996;191:131–142. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(96)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager E, Nagata Y, Gnjatic S, Wada H, Stockert E, Karbach J, Dunbar P R, Lee S Y, Jungbluth A, Jager D, Arand M, Ritter G, Cerundolo V, Dupont B, Chen Y T, Old L J, Knuth A. Monitoring CD8 T cell responses to NY-ESO-1: correlation of humoral and cellular immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4760–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones B M, Liu T, Wong R W. Reduced in vitro production of interferon-gamma, interleukin-4 and interleukin-12 and increased production of interleukin-6, interleukin-10 and tumour necrosis factor-alpha in systemic lupus erythematosus. Weak correlations of cytokine production with disease activity. Autoimmunity. 1999;31:117–124. doi: 10.3109/08916939908994055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jung T, Schauer U, Heusser C, Neumann C, Rieger C. Detection of intracellular cytokines by flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 1993;159:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khleif S N, Abrams S I, Hamilton J M, Bergmann-Leitner E, Chen A, Bastian A, Bernstein S, Chung Y, Allegra C J, Schlom J. A phase I vaccine trial with peptides reflecting ras oncogene mutations of solid tumors. J Immunother. 1999;22:155–165. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klinman D, Nutman T. Elispot assay to detect cytokine-secreting murine and human cells. In: Coligan J, Kruisbeek A, Margulies D, Shevach E, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1994. pp. 6.19.1–6.19.8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kugler A, Stuhler G, Walden P, Zoller G, Zobywalski A, Brossart P, Trefzer U, Ullrich S, Muller C A, Becker V, Gross A J, Hemmerlein B, Kanz L, Muller G A, Ringert R H. Regression of human metastatic renal cell carcinoma after vaccination with tumor cell-dendritic cell hybrids. Nat Med. 2000;6:332–336. doi: 10.1038/73193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsson M, Jin X, Ramratnam B, Ogg G S, Engelmayer J, Demoitie M A, McMichael A J, Cox W I, Steinman R M, Nixon D, Bhardwaj N. A recombinant vaccinia virus based ELISPOT assay detects high frequencies of Pol-specific CD8 T cells in HIV-1-positive individuals. AIDS. 1999;13:767–777. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199905070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lechner F, Wong D K, Dunbar P R, Chapman R, Chung R T, Dohrenwend P, Robbins G, Phillips R, Klenerman P, Walker B D. Analysis of successful immune responses in persons infected with hepatitis C virus. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1499–1512. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee P P, Yee C, Savage P A, Fong L, Brockstedt D, Weber J S, Johnson D, Swetter S, Thompson J, Greenberg P D, Roederer M, Davis M M. Characterization of circulating T cells specific for tumor-associated antigens in melanoma patients. Nat Med. 1999;5:677–685. doi: 10.1038/9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maccalli C, Pisarra P, Vegetti C, Sensi M, Parmiani G, Anichini A. Differential loss of T cell signaling molecules in metastatic melanoma patients' T lymphocyte subsets expressing distinct TCR variable regions. J Immunol. 1999;163:6912–6923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchand M, van Baren N, Weynants P, Brichard V, Dreno B, Tessier M H, Rankin E, Parmiani G, Arienti F, Humblet Y, Bourlond A, Vanwijck R, Lienard D, Beauduin M, Dietrich P Y, Russo V, Kerger J, Masucci G, Jager E, De Greve J, Atzpodien J, Brasseur F, Coulie P G, van der Bruggen P, Boon T. Tumor regressions observed in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with an antigenic peptide encoded by gene MAGE-3 and presented by HLA-A1. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:219–230. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990118)80:2<219::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Margulies D H, Plaksin D, Khilko S N, Jelonek M T. Studying interactions involving the T-cell antigen receptor by surface plasmon resonance. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:262–270. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maryanski J L, Jongeneel C V, Bucher P, Casanova J L, Walker P R. Single-cell PCR analysis of TCR repertoires selected by antigen in vivo: a high magnitude CD8 response is comprised of very few clones. Immunity. 1996;4:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murali-Krishna K, Altman J D, Suresh M, Sourdive D J, Zajac A J, Miller J D, Slansky J, Ahmed R. Counting antigen-specific CD8 T cells: a reevaluation of bystander activation during viral infection. Immunity. 1998;8:177–187. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson E L, Li X, Hsu F J, Kwak L W, Levy R, Clayberger C, Krensky A M. Tumor-specific, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response after idiotype vaccination for B-cell, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Blood. 1996;88:580–589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Novak E J, Liu A W, Nepom G T, Kwok W W. MHC class II tetramers identify peptide-specific human CD4(+) T cells proliferating in response to influenza A antigen. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:R63–R67. doi: 10.1172/JCI8476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogg G S, Rod Dunbar P, Romero P, Chen J L, Cerundolo V. High frequency of skin-homing melanocyte-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in autoimmune vitiligo. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1203–1208. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Okamoto Y, Abe T, Niwa T, Mizuhashi S, Nishida M. Development of a dual color enzyme-linked immunospot assay for simultaneous detection of murine T helper type 1- and T helper type 2-cells. Immunopharmacology. 1998;39:107–116. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(98)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pannetier C, Even J, Kourilsky P. T-cell repertoire diversity and clonal expansions in normal and clinical samples. Immunol Today. 1995;16:176–181. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pardoll D M, Topalian S L. The role of CD4+ T cell responses in antitumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:588–594. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pittet M J, Valmori D, Dunbar P R, Speiser D E, Lienard D, Lejeune F, Fleischhauer K, Cerundolo V, Cerottini J C, Romero P. High frequencies of naive Melan-A/MART-1-specific CD8(+) T cells in a large proportion of human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2 individuals. J Exp Med. 1999;190:705–715. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.5.705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reynolds S R, Oratz R, Shapiro R L, Hao P, Yun Z, Fotino M, Vukmanovic S, Bystryn J C. Stimulation of CD8+ T cell responses to MAGE-3 and Melan A/MART-1 by immunization to a polyvalent melanoma vaccine. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:972–976. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970917)72:6<972::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Romero P, Cerottini J C, Waanders G A. Novel methods to monitor antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses in cancer immunotherapy. Mol Med Today. 1998;4:305–312. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero P, Dunbar P R, Valmori D, Pittet M, Ogg G S, Rimoldi D, Chen J L, Lienard D, Cerottini J C, Cerundolo V. Ex vivo staining of metastatic lymph nodes by class I major histocompatibility complex tetramers reveals high numbers of antigen-experienced tumor-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1641–1650. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosenberg S A. A new era for cancer immunotherapy based on the genes that encode cancer antigens. Immunity. 1999;10:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg S A, Yang J C, Schwartzentruber D J, Hwu P, Marincola F M, Topalian S L, Restifo N P, Dudley M E, Schwarz S L, Spiess P J, Wunderlich J R, Parkhurst M R, Kawakami Y, Seipp C A, Einhorn J H, White D E. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Forster R, Lipp M, Lanzavecchia A. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 1999;401:708–712. doi: 10.1038/44385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schreiber S, Kampgen E, Wagner E, Pirkhammer D, Trcka J, Korschan H, Lindemann A, Dorffner R, Kittler H, Kasteliz F, Kupcu Z, Sinski A, Zatloukal K, Buschle M, Schmidt W, Birnstiel M, Kempe R E, Voigt T, Weber H A, Pehamberger H, Mertelsmann R, Brocker E B, Wolff K, Stingl G. Immunotherapy of metastatic malignant melanoma by a vaccine consisting of autologous interleukin 2-transfected cancer cells: outcome of a phase I study. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:983–993. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shankar G, Salgaller M. Immune monitoring of cancer patients undergoing experimental immunotherapy. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2000;2:66–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shirai A, Sierra V, Kelly C I, Klinman D M. Individual cells simultaneously produce both IL-4 and IL-6 in vivo. Cytokine. 1994;6:329–336. doi: 10.1016/1043-4666(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thurner B, Haendle I, Roder C, Dieckmann D, Keikavoussi P, Jonuleit H, Bender A, Maczek C, Schreiner D, von den Driesch P, Brocker E B, Steinman R M, Enk A, Kampgen E, Schuler G. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Timmerman J M, Levy R. Dendritic cell vaccines for cancer immunotherapy. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:507–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Townsend A R M, Gotch F M, Davey J. Cytotoxic T cells recognize fragments of the influenza nucleoprotein. Cell. 1985;42:457–467. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weston S A, Parish C R. New fluorescent dyes for lymphocyte migration studies. Analysis by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. J Immunol Methods. 1990;133:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90322-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whiteside T L. Signaling defects in T lymphocytes of patients with malignancy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1999;48:346–352. doi: 10.1007/s002620050585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong F S, Karttunen J, Dumont C, Wen L, Visintin I, Pilip I M, Shastri N, Pamer E G, Janeway C A., Jr Identification of an MHC class I-restricted autoantigen in type 1 diabetes by screening an organ-specific cDNA library. Nat Med. 1999;5:1026–1031. doi: 10.1038/12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Lemas V M, Flinn I W, Krone C, Ambinder R F. Application of the ELISPOT assay to the characterization of CD8(+) responses to Epstein-Barr virus antigens. Blood. 2000;95:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]