ABSTRACT

The Cry proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) are major insecticidal toxins in formulated Bt sprays and are expressed in genetically engineered Bt crops for insect pest control. However, the widespread application of Bt toxins in the field imposes strong selection pressure on target insects, leading to the evolution of insect resistance to the Bt toxins. Identification and understanding of mechanisms of insect resistance to Bt toxins are an important approach for dissecting the modes of action of Bt toxins and providing knowledge necessary for the development of resistance management technologies. In this study, cabbage looper (Trichoplusia ni) strains resistant to the transgenic dual-Bt toxin WideStrike cotton plants, which express Bt toxins Cry1Ac and Cry1F, were selected from T. ni strains resistant to the Bt formulation Bt-DiPel. The WideStrike-resistant T. ni larvae were confirmed to be resistant to both Bt toxins Cry1Ac and Cry1F. From the WideStrike-resistant T. ni, the Cry1F resistance trait was further isolated to establish a T. ni strain resistant to Cry1F only. The levels of Cry1F resistance in the WideStrike-resistant and the Cry1F-resistant strains were determined, and the inheritance of the Cry1F-resistant trait in the two strains was characterized. Genetic association analysis of the Cry1F resistance trait indicated that the Cry1F resistance in T. ni isolated in this study is not shared with the Cry1Ac resistance mechanism nor is it associated with a mutation in the ABCC2 gene, as has so far been reported in Cry1F-resistant insects.

IMPORTANCE Insecticidal toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) are highly effective for insect control in agriculture. However, the widespread application of Bt toxins exerts strong selection for Bt resistance in insect populations. The continuing success of Bt biotechnology for pest control requires the identification of resistance and understanding of the mechanisms of resistance to Bt toxins. Cry1F is an important Bt toxin used in transgenic cotton, maize, and soybean varieties adopted widely for insect control. To understand the mode of action of Cry1F and mechanisms of Cry1F resistance in insects, it is important to identify Cry1F-specific resistance and the resistance mechanisms. In this study, Trichoplusia ni strains resistant to commercial “WideStrike” cotton plants that express Bt toxins Cry1Ac and Cry1F were selected, and a Cry1F-specific resistant strain was isolated. The isolation of the novel Cry1F-specific resistance in the T. ni provided an invaluable biological system to discover a Cry1F-specific novel resistance mechanism.

KEYWORDS: Bacillus thuringiensis, Bt resistance, Bt toxins, Cry1Ac, Cry1F, Trichoplusia ni

INTRODUCTION

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) strains produce an array of proteinaceous insecticidal proteins (Bt toxins) (1, 2). Selected Bt strains have been developed as bioinsecticide sprays, and Bt toxin genes have been engineered into transgenic crops (Bt crops) to confer resistance to target insect pests (3–5). Insect-resistant Bt crops have been adopted widely worldwide, providing agricultural, environmental, and economic benefits (6–9). The widespread application of Bt toxins in the field has imposed a strong selection pressure on target insect pests, leading to the evolution of resistance to the Bt toxins in the insect populations. Since the detection of early cases of insect resistance to Bt sprays (10–12) and to Bt crops (13), the occurrence of insect resistance to Bt toxins in agriculture has been increasing (14, 15). The continuing success of Bt technologies requires the identification of resistant alleles and an understanding of the genetic mechanisms of resistance to Bt toxins.

Cry proteins are the major group of insecticidal toxins in Bt, in terms of both variety and abundance in the bacterium (2). Cry toxins are produced during the stationary phase of the bacterial growth cycle, forming parasporal crystals (1); are important insecticidal toxins in Bt spray products; and are expressed in transgenic Bt crops (16, 17). The Cry toxin Cry1F was identified initially from B. thuringiensis subsp. aizawai (18) and has been used in current Bt cotton and Bt maize varieties adopted widely (19–22) and in Bt soybean varieties being commercialized recently for the control of lepidopteran pests (23). Cry1F is often pyramided with the toxin Cry1Ac or Cry1Ab (and other Bt toxins) in Bt crops to confer resistance to lepidopteran pests. Resistance to Cry1F crops has occurred in three major lepidopteran pests within 10 years after Cry1F crops were planted (15, 24–28), and resistance to Cry1F has been reported recently in more insect species and to be spread more widely in the field (29, 30).

Cry1F is known to share binding sites with Cry1Ab and Cry1Ac in the insect midgut and also to have unique binding sites not shared with Cry1A toxins (31–38). Therefore, various levels of cross-resistance between Cry1F and Cry1A toxins are often observed (28, 39–44), and resistance to Cry1F has also been found to be associated with mutations in the ABCC2 gene (45–47) which are known to confer resistance to Cry1Ac (48–50). However, genes for the Cry1F-specific binding sites not shared with Cry1Ac binding have not been identified. To understand the pathways of toxicity of Cry1F and mechanisms of Cry1F resistance in insects, it is important to identify the Cry1F-specific binding sites, or receptors, and Cry1F-specific resistance mechanisms.

The cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni, is a polyphagous insect pest and has developed resistance to Bt sprays in greenhouses (10). From the Bt-resistant T. ni populations from the greenhouses, Cry1Ac resistance and Cry2Ab resistance have been isolated and the resistance-associated genes have been identified (43, 48, 50–52). In this study, T. ni strains resistant to the commercial “WideStrike” cotton plants which express Cry1Ac and Cry1F were selected from the greenhouse-derived Bt-resistant strains, and a Cry1F-specific resistant strain was further isolated. The genetic basis of the Cry1F-specific resistance was determined to be novel, therefore providing a unique biological research system to discover a Cry1F-specific novel resistance mechanism in insects.

RESULTS

T. ni strains resistant to WideStrike plants were selected from the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains.

T. ni strains resistant to WideStrike plants were obtained from the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains after five rounds of selection on WideStrike leaves in 12 generations (Table 1). In the initial selection (the 1st selection) on WideStrike leaves, 7% of the larvae (n = 1,500) from both the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains survived the 7-day feeding on the WideStrike leaves. No larvae from the Cornell strain survived the 7-day selection on WideStrike leaves. The T. ni colonies that survived the first selection were selected on WideStrike leaves for four additional rounds in the 3rd, 4th, 7th, and the 12th generations. In the final selection on WideStrike leaves (in 12th generation), 27% and 23% of the larvae (n = 625) that originated from the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains, respectively, survived on WideStrike leaves. As the resistance to Cry1Ac in the original GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains was known to be recessive (53, 54), indicating the selected strains were homozygous for Cry1Ac resistance, the WideStrike-selected strains were further selected with Cry1F only (2 mL of Cry1F at 200 μg/mL spread on the 50 cm2 of diet surface) in the 19th and 29th generations. In the Cry1F selections, the survivals of the larvae originated from the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains in generation 19 were 64% and 50% (n = 400), respectively, and in generation 29, they were 73% and 78% (n = 400), respectively. These two T. ni strains selected from the GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains were named GLEN-WideStrike-R and GIPN-WideStrike-R, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Selection of T. ni GLEN-DiPel-R and GIPN-DiPel-R strains on WideStrike plant leaves

| Selection on WideStrike leaves | Generation (starting from 1st selection) |

|---|---|

| 1st (7 days)a | 1st |

| 2nd (entire larval stage) | 3rd |

| 3rd (7 days) | 4th |

| 4th (7 days) | 7th |

| 5th (7 days)b | 12th |

From 1,500 larvae, 7% of the larvae from both the GLEN-DiPel and the GIPN-DiPel strains survived the 7-day selection. Larvae from the Cornell strain were included in the experiment as a negative control and no larvae of the Cornell strain survived.

From 625 larvae, 27% and 23% of the larvae from the GLEN-DiPel and the GIPN-DiPel strains, respectively, survived the 7-day selection.

Resistance of GLEN-WideStrike-R larvae to Cry1Ac and Cry1F.

Larval bioassays showed that the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was highly resistant to Cry1Ac with a resistance ratio of 2,155-fold on artificial diet, in comparison with the susceptible Cornell strain (Table 2). The inheritance of the Cry1Ac resistance in the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was determined to be incompletely recessive with calculated degree of dominance (D) to be −0.10 and −0.34 for the two reciprocal crosses (Table 2). Notably, the resistance in the F1 progenies showed paternal bias. The F1 progeny from the cross of resistant male with susceptible female showed a higher level of resistance to Cry1Ac than the F1 progeny from the cross of resistant female with susceptible male (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Level and inheritance of resistance to Cry1Ac and Cry1F in GLEN-WideStrike-R strain of T. ni

| Bt toxin | Straina | n | Slope (SE) | LC50 (95% CI) (μg/mL) | χ2 (df) | Resistance ratio | Db |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cry1Ac | Cornell (SS) | 350 | 3.10 (0.34) | 0.26 (0.20–0.33) | 5.42 (5) | 1.0 | |

| GLEN-WideStrike-R (RR) | 350 | 1.88 (0.31) | 560.2 (292.1–929.3) | 7.68 (5) | 2,155 | ||

| F1a (SS♂ × RR♀) | 350 | 2.07 (0.36) | 3.3 (2.0–4.5) | 0.86 (5) | 13 | −0.34 | |

| F1b (RR♂ × SS♀) | 350 | 1.78 (0.20) | 8.3 (6.1–10.8) | 3.84 (5) | 32 | −0.10 | |

| Cry1F (expt. 1) | Cornell (SS) | 400 | 1.79 (0.23) | 0.66 (0.46–0.90) | 2.6 (6) | 1.0 | |

| GLEN-WideStrike-R (RR) | 400 | 0.90 (0.19) | 118.5 (20.7–285.3) | 9.6 (6) | 180 | ||

| F1a (SS♂ × RR♀) | 400 | 1.61 (0.14) | 12.2 (8.1–18.4) | 9.0 (6) | 18 | 0.12 | |

| F1b (RR♂ × SS♀) | 400 | 0.90 (0.08) | 64.7 (39.9–111.8) | 6.3 (6) | 98 | 0.77 | |

| Cry1F (expt. 2) | Cornell (SS) | 350 | 2.74 (0.44) | 0.83 (0.61–1.06) | 1.5 (5) | 1.0 | |

| GLEN-WideStrike-R (RR) | 300 | 1.12 (0.15) | 105.0 (66.3–160.5) | 0.48 (4) | 127 | ||

| F1a (SS♂ × RR♀) | 500 | 1.05 (0.11) | 10.7 (6.9–15.9) | 7.06 (8) | 13 | 0.06 | |

| F1b (RR♂ × SS♀) | 300 | 1.34 (0.13) | 54.4 (35.3–84.7) | 4.08 (4) | 66 | 0.73 |

aSS represents the homozygous susceptible genotype in the Cornell strain, and RR represents the homozygous resistant genotype in the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain.

Degree of dominance calculated using the Stone formula (32).

The WideStrike-resistant larvae were also resistant to Cry1F. The bioassay results showed that the resistance level to Cry1F in the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was 127- to 180-fold compared with the Cornell strain, and the resistance was incompletely dominant and paternally biased (Table 2). The F1 larvae from the cross with GLEN-WideStrike-R males had a higher level of resistance to Cry1F (98- and 66-fold from two experiments) than the F1 larvae from the cross with females from GLEN-WideStrike-R (18- and 13-fold from two experiments) (Table 2). The degree of dominance of the resistance to Cry1F in the F1 larvae from the two reciprocal crosses was 0.06 and 0.73, respectively, and 0.12 and 0.77, respectively, from two independent replicate experiments (Table 2).

Cry1F resistance isolated from the T. ni GLEN-WideStrike-R strain.

The resistance to Cry1F in the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was shown to be incompletely dominant with paternal bias and resistance to Cry1Ac in T. ni was incompletely recessive (Table 2). Therefore, isolation of the resistance to Cry1F from the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain by introgression of Cry1F resistance to the Cornell strain was performed initially in the F1 progenies from resistant T. ni males with the susceptible Cornell strain females (Table 3). In the first round of selection with Cry1F, 13% of the F1 larvae (n = 1,000) from the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain crossed with the Cornell strain survived the 7-day selection on diet with Cry1F at 200 μg/mL. The selections of the Cry1F resistance from the final 4 backcrosses were conducted in F2 or F3 populations to select homozygous Cry1F-resistant alleles. In the last round of selection of the Cry1F-resistant strain (the 10th selection), 11.6% of the larvae (n = 3,000) survived the 7-day selection on Cry1F at 200 μg/mL (Table 3). The resulting strain resistant to Cry1F was named GLEN-Cry1F-R.

TABLE 3.

Selection of Cry1F-resistant strain from WideStrike-resistant T. ni

| Cry1F selection | T. ni families prepared for selectiona |

|---|---|

| 1stb | F1 from GLEN-WideStrike-R (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 2nd | F1 from survivors of 1st selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 3rd | F2 from survivors of 2nd selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 4th | F1 from survivors of 3rd selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 5th | F1 from survivors of 4th selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 6th | F3 from survivors of 5th selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 7th | F2 from survivors of 6th selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 8th | F2 from survivors of 7th selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 9th | F2 from survivors of 8th selection (m) × Cornell strain (f) |

| 10thc | F2 of survivors from 9th selection |

m, male; f, female.

Survival from selection with 200 μg/mL Cry1F was 13% (n = 1,000).

Survival from selection was 11.6% (n = 3,000).

Resistance of the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain to Cry1F.

Results from the bioassays of GLEN-Cry1F-R larvae with Cry1F and Cry1Ac showed that the larvae were resistant to Cry1F with a resistance ratio of 55-fold, compared with the susceptible T. ni Cornell strain, but showed no significant cross-resistance to Cry1Ac (Table 4). Results from bioassays of F1 larvae from reciprocal crosses of the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain with the susceptible Cornell strain on Cry1F and control bioassays of the two parental strains indicated that the inheritance of the Cry1F resistance in the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain was incompletely recessive, with the degree of dominance of −0.36 and −0.34 for the F1 populations from the reciprocal crosses, respectively (Table 5). In the inheritance analysis experiment, the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain showed a resistance level of 26-fold, but the level of resistance in the F1 larvae from the two reciprocal crosses was only 2.8- and 2.9-fold (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Level of resistance to Cry1F and cross-resistance to Cry1Ac in GLEN-Cry1F-R strain of T. ni

| Bt toxin | Strain | n | Slope (SE) | LC50 (95% CI) (μg/mL) | χ2 (df) | Resistance ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cry1F | Cornell | 450 | 2.36 (0.19) | 0.85 (0.71–1.00) | 1.5 (7) | 1 |

| GLEN-Cry1F-R | 450 | 2.58 (0.31) | 46.6 (38.4–56.4) | 2.5 (7) | 55 | |

| Cry1Ac | Cornell | 300 | 4.54 (0.51) | 0.27 (0.24–0.31) | 0.8 (4) | 1 |

| GLEN-Cry1F-R | 250 | 2.41 (0.27) | 0.49 (0.30–0.76) | 5.5 (3) | 1.8 |

TABLE 5.

Level and inheritance of resistance to Cry1F in GLEN-Cry1F-R strain of T. ni

| Bt toxin | Strain | n | Slope (SE) | LC50 (95% CI) (μg/mL) | χ2 (df) | Resistance ratio | Da |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cry1F | Cornell (SS) | 350 | 2.32 (0.26) | 0.76 (0.60–0.95) | 5.00 (5) | 1.0 | |

| GLEN-Cry1F-R (RR) | 400 | 1.94 (0.18) | 19.8 (14.6–26.8) | 6.12 (6) | 26 | ||

| F1a (SS♂ × RR♀) | 450 | 1.54 (0.15) | 2.15 (1.49–3.01) | 2.44 (7) | 2.8 | −0.36 | |

| F1b (RR♂ × SS♀) | 500 | 2.22 (0.32) | 2.22 (1.62–2.85) | 4.08 (8) | 2.9 | −0.34 |

Degree of dominance calculated using the Stone formula (32).

Fifth instar larvae of the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain were confirmed to be resistant to Cry1F. In 5th instar larval assays (n = 12), 11 larvae from the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain completed pupation on diet with 50 μg of Cry1F/g of diet, but only 6 larvae from the Cornell strain pupated under the same treatment. With 125 μg of Cry1F/g of diet, 10 larvae from the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain completed pupation, but no larvae from the Cornell strain survived. Therefore, resistance to Cry1F was confirmed in both neonate and 5th instar larvae of the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain.

Resistance to Cry1F in GLEN-Cry1F-R is not associated with the Cry1Ac resistance-associated ABCC2 gene mutation.

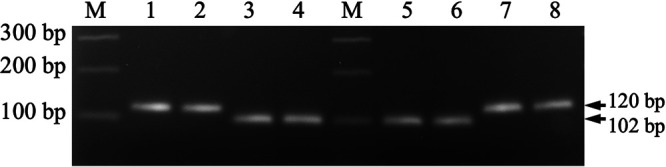

Genotyping of the ABCC2 gene alleles in the GLEN-WideStrike-R and GLEN-Cry1F-R strains in comparison with the Cornell and the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R strains determined that the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain shared the same ABCC2 allele of the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R strain, but the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain had the same ABCC2 allele as the Cornell strain (Fig. 1). Therefore, the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain carried the same ABCC2 allele from the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R strain, which is known to be associated with the Cry1Ac resistance (50). The GLEN-Cry1F-R strain did not carry the Cry1Ac resistance-associated ABCC2 allele from the WideStrike-R strain, but instead had the ABCC2 allele from the susceptible Cornell strain.

FIG 1.

Genotyping of the ABCC2 gene in T. ni from the Cornell strain (1 and 2), GLEN-Cry1Ac-R (3 and 4), GLEN-WideStrike-R (5 and 6), and GLEN-Cry1F-R (7 and 8) by PCR analysis. The Cry1Ac-susceptible allele was shown as a 120-bp fragment (MZ571761), and the Cry1Ac-resistant allele was shown as a 102-bp fragment (MZ571762). M, molecular size markers.

Resistance to Cry1F in GLEN-Cry1F-R is not associated with the Cry1Ac resistance-associated lack of APN1 in the larval midgut.

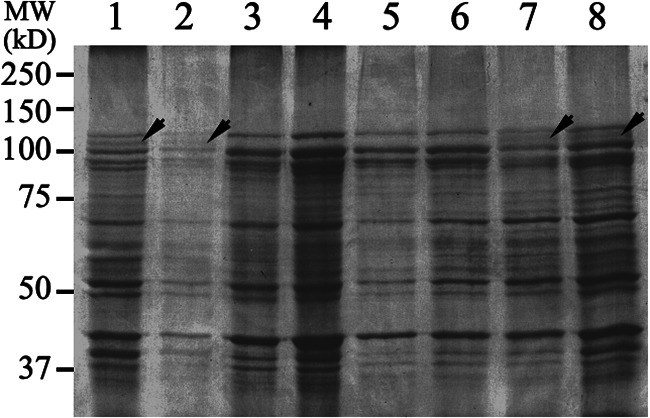

SDS-PAGE analysis of the midgut brush border membrane vesicle (BBMV) proteins from the same T. ni larvae genotyped for ABCC2 alleles above showed that the 110-kDa APN1 protein band was not visible in the midgut BBMV proteins from the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R and the GLEN-WideStrike-R strains. In contrast, the APN1 protein band was similarly visible in the midgut BBMV proteins from the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain and in the Cornell strain (Fig. 2). Therefore, the loss of the APN1 protein band, which is known to be associated with Cry1Ac resistance (55), was observed in the Cry1Ac-resistant strains GLEN-Cry1Ac-R and GLEN-WideStrike-R, but the APN1 protein was similarly present in the midgut BBMV proteins from the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain and in the susceptible Cornell strain (Fig. 2).

FIG 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of midgut BBMV proteins from individual T. ni 5th instar larvae from the Cornell strain (1 and 2), GLEN-Cry1Ac-R (3 and 4), GLEN-WideStrike-R (5 and 6), and GLEN-Cry1F-R (7 and 8). Arrows indicate the 110-kDa APN1 protein band. MW, molecular weight markers.

DISCUSSION

In this study, T. ni strains resistant to the dual-toxin WideStrike plants were selected from two DiPel-resistant strains, namely, GLEN-DiPel-R and GIPN-DiPel-R. These two DiPel-resistant strains originated from different commercial greenhouses (10) and had been maintained independently in our lab since 2003 (53, 56). However, the two strains showed the same survival rate (7%) from the first selection on WideStrike leaves and also a very similar survival rate (27% and 23% for GLEN-DiPel-R and GIPN-DiPel-R, respectively) in the final selection on WideStrike leaves (Table 1). Therefore, the alleles resistant to WideStrike leaves were present in the original GLEN-DiPel-R and GIPN-DiPel-R strains, prior to the selection on WideStrike leaves in this study.

DiPel is a spray formulation of B. thuringiensis subspecies kurstaki, which is known to carry genes for Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac, Cry2Aa, and Cry2Ab but not for Cry1F (1, 57). The DiPel-resistant T. ni larvae are highly resistant to Cry1Ac (53, 54). The Cry1Ac resistance isolated from the DiPel-resistant T. ni shows only a low level of cross-resistance to Cry1F (43), which is not sufficient to enable the larvae to survive on WideStrike plants. Therefore, resistance to WideStrike plants requires resistance to both Cry1Ac and Cry1F in T. ni larvae. The results from bioassays of WideStrike-resistant T. ni larvae confirmed that the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain isolated in this study is resistant to both Cry1Ac and Cry1F (Table 2). The WideStrike-resistant larvae showed a high level of resistance to Cry1Ac, and the resistance trait was incompletely recessive (Table 2), which is consistent with the inheritance of Cry1Ac resistance characterized from the Cry1Ac-resistant T. ni strains isolated from the same parental DiPel-resistant strains (53, 54). The level of resistance to Cry1F in the WideStrike-resistant larvae was 127- and 180-fold compared with the Cornell strain from two bioassays in this study, and notably, the Cry1F resistance in the WideStrike-resistant larvae showed incompletely dominant inheritance (Table 2). Interestingly, the resistance to both Cry1Ac and to Cry1F in the WideStrike-resistant T. ni showed paternal bias (Table 2), which is not commonly observed for insect resistance to Bt toxins.

In this study, the Cry1F-resistant trait was further isolated from the WideStrike-resistant T. ni to establish a strain resistant to Cry1F only, namely, the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain. The resistance of GLEN-Cry1F-R larvae to Cry1F (26- to 55-fold) is lower than the resistance level in the dual-toxin-resistant GLEN-WideStrike-R strain and showed no significant cross-resistance to Cry1Ac (Table 4 and 5). In contrast to the observation that the Cry1F resistance was an incompletely dominant trait in the WideStrike-resistant strain (Table 2), the Cry1F resistance in GLEN-Cry1F-R larvae was incompletely recessive with the degree of dominance of −0.34 to −0.36 (Table 5). Although the inheritance of Cry1Ac resistance and the inheritance of Cry1F resistance both exhibited significant paternal bias in the dual-toxin-resistant GLEN-WideStrike-R strain (Table 2), the Cry1F resistance in the single-toxin-resistant GLEN-Cry1F-R strain showed no paternally biased inheritance (Table 5), and this finding is also true for the Cry1Ac resistance in the Cry1Ac-resistant T. ni strains from the same original DiPel-resistant strains (53, 54). Paternally biased inheritance of Cry1Ac resistance was not observed in the original DiPel-resistant T. ni strains in our previous studies (58). It will be interesting to understand whether and how the paternally biased inheritance of the resistance resulted from the interaction of the two resistance traits selected or if additional factors were selected during the process of selection with the dual-toxin WideStrike leaves.

Cry1F-resistant insect strains have been selected from several Lepidoptera pests, and those Cry1F-resistant insects also showed various levels of resistance to Cry1Ac (28, 40, 41, 44, 59–64). Cross-resistance between Cry1F and Cry1Ac has been commonly observed in Cry1Ac-resistant insects, as well (39, 43, 65–67). It has been well known from numerous studies of Cry toxin binding to insect larval midgut BBMV preparations that Cry1F and Cry1Ac have shared binding sites, in addition to their respective unique binding sites, in the midgut brush border in insects (31, 33, 35, 37, 68). A recent study of Cry toxin binding sites using disabled Cry toxin mutants functionally confirmed the presence of shared binding sites between Cry1F and Cry1A toxins in insect midgut (38). However, what midgut proteins serve as the shared and the unique binding sites for Cry1F remain elusive. The resistance-conferring mutation in GLEN-Cry1F-R larvae caused resistance only to Cry1F but not to Cry1Ac. Whether the mutation is associated with the Cry1F-specific binding sites but not the shared binding sites with Cry1Ac requires to be understood.

The ABCC2 protein from the midgut has been shown to be a functional receptor for Cry1Ac in cultured cells (69, 70). The Cry1Ac resistance in Heliothis virescens, Plutella xylostella, and T. ni has been identified to be associated with ABCC2 gene mutations (48–50), and these ABCC2 mutation-associated Cry1Ac-resistant insects also showed cross-resistance to Cry1F (39, 43, 71). Similarly, the Cry1F resistance in the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis, and in the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, has also been identified to be associated with the ABCC2 gene (45–47, 64). Functional analysis of the S. frugiperda ABCC2 protein expressed in cell culture supported the role of ABCC2 mediating the toxicity of both Cry1F and Cry1Ac (72). Moreover, knockout of the ABCC2 gene may result in resistance to Cry1F in lepidopteran larvae (73–75). Therefore, results from studies of ABCC2 in various insects have indicated that ABCC2 may serve as or be associated with the binding sites shared by Cry1Ac and Cry1F.

In T. ni larvae, it has been known for over 2 decades that Cry1F shares the binding sites for Cry1Ac and Cry1Ab with a lower affinity (76). Consistent with the shared binding sites between Cry1Ac and Cry1F, T. ni selected for Cry1Ac resistance lacks the binding sites for Cry1Ac and shows a low-level cross-resistance to Cry1F (43). The Cry1Ac resistance in T. ni is now known to be associated with a frameshift insertion mutation in the ABCC2 gene (50) and also associated with missing the 110-kDa APN1 and upregulated expression of APN6 in the midgut brush border membranes (55). As the Cry1F resistance isolated in this study in the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain shows no significant cross-resistance to Cry1Ac, it is expected that the Cry1F resistance in the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain is conferred by mutation(s) in the pathway of toxicity of Cry1F and is not shared with Cry1Ac. Our examinations of the Cry1Ac-associated ABCC2 mutation and the APN1 protein in the midgut BBMV from the Cry1F-resistant larvae confirmed that the Cry1F resistance in T. ni is neither associated with the ABCC2 gene mutation (Fig. 1) nor associated with the altered APN gene expression in the larval midgut (Fig. 2). The Cry1F resistance in the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain of T. ni is conferred by the mutation of a gene involved in the interaction with Cry1F but not with Cry1Ac. Therefore, the Cry1F resistance in the GLEN-Cry1F-R strain is not conferred by an ABCC2 mutation-associated resistance mechanism which is the Cry1F resistance mechanism that has so far been reported for Cry1F resistance in other insects (45–47, 64).

The Cry1Ac resistance in T. ni has a level of cross-resistance to Cry1F of about 8-fold, compared with the Cornell strain (43). The Cry1F resistance in T. ni isolated in this study has a level of resistance 26- to 55-fold (Table 4 and 5). In the presence of both Cry1Ac and Cry1F resistance in T. ni (i.e., the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain), the level of resistance to Cry1F in larvae was higher, namely, 127- to 180-fold, compared with the Cornell strain (Table 2). These results are consistent with the presence of both functional Cry1F binding sites shared with Cry1Ac and unique to Cry1F in T. ni (76). Therefore, selection of Cry1Ac resistance in an insect will likely partially select Cry1F resistance. High-level resistance to Cry1F requires loss-of-function mutations in multiple binding sites or pathways of toxicity for Cry1F. The Cry1F-resistant trait in GLEN-Cry1F-R is not associated with an ABCC2 gene mutation nor with an alteration of APN expression, but it is conferred by a novel gene mutation to be identified. The isolation of the specific Cry1F resistance in the T. ni GLEN-Cry1F-R strain in this study has provided an invaluable biological research system and opportunity to discover a novel Cry1F resistance mechanism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

T. ni strains, cotton plants, and Bt Cry toxins.

The T. ni strains used in this study were the Bt-susceptible laboratory Cornell strain (53) and the resistant strains to the Bt product DiPel, namely, GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains (56, 58). The GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel strains were derived from different commercial greenhouses in British Columbia, Canada (10), and were maintained independently in the lab since 2003 (53, 56). The T. ni strain resistant to Bt toxin Cry1Ac, the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R strain, isolated from the GLEN-DiPel strain was also used in the study (50). The T. ni colonies were maintained on artificial diet under constant temperature at 26°C, relative humidity of 50%, and photoperiod of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark (53). The toxin Cry1Ac was prepared from the B. thuringiensis strain HD-73 as described previously (53). Seeds of the Bt cotton variety WideStrike and non-Bt cotton variety (TSN313289) and Bt Cry1F toxin were obtained from Corteva Agroscience (Indianapolis, IN). Cotton plants were grown in formulated potting soil “Cornell mix” (77) in a greenhouse as described by Wang et al. (78).

Selection of WideStrike-resistant and Cry1F-resistant T. ni strains.

Neonate larvae (n = 1,500) from the Bt-resistant T. ni strains GLEN-DiPel and GIPN-DiPel were placed in 473-mL cups (50 larvae/cup) provided with leaves of WideStrike plants for 7 days, and survivors were transferred onto artificial diet and were reared until completion of the larval stage. The WideStrike leaf-selected T. ni insects were not selected on WideStrike leaves in the second generation but were selected on WideStrike leaves for the entire larval stage in generation 3 and for 7 days in generations 4, 7, and 12 (Table 1). The resistant strains selected on WideStrike leaves were finally selected on Cry1F on artificial diet (2 mL of Cry1F at 200 μg/mL applied on 50 cm2 of the diet surface) for 7 days in generations 19 and 29. The resulting strains after the series of selections were named GLEN-WideStrike-R and GIPN-WideStrike-R, respectively, and were maintained on artificial diet in the lab without further selection.

To isolate the Cry1F resistance in T. ni, the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was crossed with the Cornell strain, and the F1 progenies were selected with Cry1F on artificial diet with a selection scenario detailed in Table 3. As the Cry1F resistance in GLEN-WideStrike-R strain was shown to be incompletely dominant (Table 2) and the Cry1Ac resistance in the parental strain GLEN-DiPel-R was known to be incompletely recessive (53), the F1 progenies from the first cross and the subsequent 4 crosses of the survivors with the susceptible Cornell strain were selected on Cry1F (Table 3), in an attempt to more effectively select the Cry1F resistance but unfavorably for selection of the cross-resistance to Cry1F from Cry1Ac resistance. The selections of the Cry1F resistance from the final 4 backcrosses were conducted in F2 or F3 populations to obtain homozygous Cry1F-resistant alleles (Table 3). The selection of T. ni larvae on Cry1F was performed on artificial diet using the same method as described previously (43, 52), except Cry1F was used to select Cry1F-resistant T. ni. A 2-mL aliquot of Cry1F at 200 μg/mL was spread on the surface of the diet (ca. 50 cm2) in Styrofoam cups, and neonate larvae were reared in the cups for 7 days. Survivors (>2nd instars) from the 7-day Cry1F selection were transferred onto fresh diet to complete larval development. For each round of Cry1F selection, the Cornell strain was also treated with Cry1F on diet in parallel to serve as a control to ensure that the selection dose of Cry1F completely killed the susceptible individuals.

Bioassays of resistance levels of T. ni strains to Bt Cry toxins.

The susceptibility of T. ni strains to Bt toxin Cry1Ac and Cry1F was determined using the neonate larval bioassay method as described previously (53). The larvae were assayed in 30-mL rearing cups with 5-mL diet. An aliquot of 200-μL Cry toxin solution was applied on the surface of the diet (ca. 7 cm2), and each Cry toxin dose included 5 replicate cups. Ten neonate larvae were placed in each cup after the toxin solution was dried, and the larval mortalities were scored after 4 days of rearing under the rearing condition as described above. Controls were treated with the same procedures, except that no toxins were applied to the diet. The computer software POLO (79) was used to calculate the 50% lethal concentration (LC50) of the toxins and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) in T. ni strains.

Bioassays of 5th instar T. ni were conducted on artificial diet with Cry1F mixed in the diet. Freshly molted 5th instar larvae were placed individually in wells of a 24-well plate provided with diet with or without Cry1F. Two Cry1F doses, namely, 50 μg and 125 μg of Cry1F per g of diet, were used with 12 larvae for each dose for the bioassay. The larvae were incubated at 26°C, relative humidity of 50%, and photoperiod of 16 h of light and 8 h of dark, as described above, until completion of pupation.

Inheritance analysis of Cry1Ac resistance and Cry1F resistance in T. ni strains.

Genetic inheritance of the resistance to Cry1Ac and Cry1F in the GLEN-WideStrike-R strain and the resistance to Cry1F in GLEN-Cry1F-R strain were analyzed using the same method as described previously (56). Reciprocal crosses were made between the GLEN-WideStrike-R or GLEN-Cry1F-R strain and the susceptible Cornell strain, and neonate larvae from the F1 families as well as larvae from the parental resistant strains and the Cornell strain were bioassayed for their susceptibility to Cry1Ac and to Cry1F on artificial diet as described above. The degree of dominance (D) (80) for the Cry1F resistance was calculated as described previously (56).

Examination of the Cry1Ac resistance-associated ABCC2 mutation in Cry1F-resistant T. ni.

A diagnostic intronic DNA fragment of the ABCC2 gene to differentiate the alleles from the Cornell strain and the Cry1Ac resistant strain (GenBank accession [acc.] no. MW595613 to MW595616) (50) was amplified by PCR from T. ni individuals and used to examine the association of the Cry1Ac-resistant ABCC2 allele with the Cry1F resistance. DNA of T. ni individuals was prepared from the larval hemolymph or tissues by lysis of the tissue with mild detergents and digestion with protease K (81), and the DNA fragment was amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-TACCAGCTTTTTAGTAGTCGTTAG-3′ and 5′-GCCCAAGATAGTCTGAAAGTAA-3′. The PCR fragment from the allele of the Cornell strain was 120 bp, and the fragment from the GLEN-Cry1Ac-R strain was 102 bp (GenBank acc. no. MZ571761 and MZ571762). The diagnostic PCR product sizes for the ABCC2 alleles were examined by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Analysis of APN1 in the midgut BBMV from larvae of the Cry1F-resistant T. ni.

The APN1 protein in the T. ni midgut brush border membrane can be detected as a distinct 110-kDa protein band by SDS-PAGE analysis of proteins from larval midgut brush border membrane vesicle (BBMV) preparations (55). To examine the presence or absence of the 110-kDa APN1 protein in the larval midgut brush border membrane, the midgut was isolated from mid-5th instar larvae on ice and cleared of other attached tissues and the food bolus enclosed in the peritrophic membrane in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The midgut was stored individually at −20°C, after a cleaning step by rinsing in PBS. Midgut BBMV samples were prepared from the midgut tissue from individual larvae (81). The distinct 110-kDa APN1 protein in the midgut BBMV was examined by 7.5% SDS-PAGE analysis of the BBMV proteins and visualized by Coomassie blue staining, as reported previously (50, 55).

Data availability.

DNA sequences of the diagnostic PCR fragments for the two ABCC2 alleles have been deposited in GenBank with acc. no. MZ571761 and MZ571762.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the AFRI Foundational Program grant no. 2019-67013-29349 and the Biotechnology Risk Assessment Research Grants Program grant no. 2021-33522-35383 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Contributor Information

Ping Wang, Email: pingwang@cornell.edu.

Karyn N. Johnson, University of Queensland

REFERENCES

- 1.Schnepf E, Crickmore N, Van Rie J, Lereclus D, Baum J, Feitelson J, Zeigler DR, Dean DH. 1998. Bacillus thuringiensis and its pesticidal crystal proteins. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62:775–806. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.62.3.775-806.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crickmore N, Berry C, Panneerselvam S, Mishra R, Connor TR, Bonning BC. 2021. A structure-based nomenclature for Bacillus thuringiensis and other bacteria-derived pesticidal proteins. J Invertebr Pathol 186:107438. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nester E, Thomashow LS, Metz M, Gordon M. 2002. 100 years of Bacillus thuringiensis: a critical scientific assessment. American Academy of Microbiology, Washington, DC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lacey LA, Grzywacz D, Shapiro-Ilan DI, Frutos R, Brownbridge M, Goettel MS. 2015. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: back to the future. J Invertebr Pathol 132:1–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bravo A, Likitvivatanavong S, Gill SS, Soberon M. 2011. Bacillus thuringiensis: a story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 41:423–31431. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James C. 2019. Global status of commercialized Biotech/GM crops in 2019: Biotech crops drive socioeconomic development and sustainable environment in the new frontier. ISAAA, Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romeis J, Naranjo SE, Meissle M, Shelton AM. 2019. Genetically engineered crops help support conservation biological control. Biol Control 130:136–154. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2018.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchison WD, Burkness EC, Mitchell PD, Moon RD, Leslie TW, Fleischer SJ, Abrahamson M, Hamilton KL, Steffey KL, Gray ME, Hellmich RL, Kaster LV, Hunt TE, Wright RJ, Pecinovsky K, Rabaey TL, Flood BR, Raun ES. 2010. Areawide suppression of European corn borer with Bt maize reaps savings to non-Bt maize growers. Science 330:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1190242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dively GP, Venugopal PD, Bean D, Whalen J, Holmstrom K, Kuhar TP, Doughty HB, Patton T, Cissel W, Hutchison WD. 2018. Regional pest suppression associated with widespread Bt maize adoption benefits vegetable growers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115:3320–3325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720692115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janmaat AF, Myers J. 2003. Rapid evolution and the cost of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in greenhouse populations of cabbage loopers, Trichoplusia ni. Proc Biol Sci 270:2263–2270. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelton AM, Robertson JL, Tang JD, Perez C, Eigenbrode SD, Preisler HK, Wilsey WT, Cooley RJ. 1993. Resistance of diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to Bacillus thuringiensis subspecies in the field. J Econ Entom 86:697–705. doi: 10.1093/jee/86.3.697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabashnik BE, Cushing NL, Finson N, Johnson MW. 1990. Field development of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis in diamondback moth (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae). J Econ Entomol 83:1671–1676. doi: 10.1093/jee/83.5.1671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Rensburg JBJ. 2007. First report of field resistance by the stem borer, Busseola fusca (Fuller) to Bt-transgenic maize. South Afr J Plant Soil 24:147–151. doi: 10.1080/02571862.2007.10634798. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tabashnik BE, Carriere Y. 2017. Surge in insect resistance to transgenic crops and prospects for sustainability. Nat Biotechnol 35:926–935. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabashnik BE, Carriere Y. 2019. Global patterns of resistance to Bt crops highlighting pink bollworm in the United States, China, and India. J Econ Entomol 112:2513–2523. doi: 10.1093/jee/toz173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hernández-Fernández J. 2016. Bacillus thuringiensis: a natural tool in insect pest control, p 121–139. In The handbook of microbial bioresources. CABI Publishing, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabashnik BE, Van Rensburg JB, Carriere Y. 2009. Field-evolved insect resistance to Bt crops: definition, theory, and data. J Econ Entomol 102:2011–2025. doi: 10.1603/029.102.0601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers JA, Jelen A, Gilbert MP, Jany CS, Johnson TB, Gawron-Burke C. 1991. Isolation and characterization of a novel insecticidal crystal protein gene from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. aizawai. J Bacteriol 173:3966–3976. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.3966-3976.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marques LH, Lepping M, Castro BA, Santos AC, Rossetto J, Nunes MZ, Silva O, Moscardini VF, de Sa VGM, Nowatzki T, Dahmer ML, Gontijo PC. 2021. Field efficacy of Bt cotton containing events DAS-21023–5 x DAS-24236–5 x SYN-IR102-7 against lepidopteran pests and impact on the non-target arthropod community in Brazil. PLoS One 16:e0251134. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siebert MW, Nolting S, Leonard BR, Braxton LB, All JN, Van Duyn JW, Bradley JR, Bacheler J, Huckaba RM. 2008. Efficacy of transgenic cotton expressing Cry1Ac and Cry1F insecticidal protein against heliothines (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J Econ Entomol 101:1950–1959. doi: 10.1603/0022-0493-101.6.1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siebert MW, Nolting SP, Hendrix W, Dhavala S, Craig C, Leonard BR, Stewart SD, All J, Musser FR, Buntin GD, Samuel L. 2012. Evaluation of corn hybrids expressing Cry1F, cry1A.105, Cry2Ab2, Cry34Ab1/Cry35Ab1, and Cry3Bb1 against southern United States insect pests. J Econ Entomol 105:1825–1834. doi: 10.1603/ec12155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rule DM, Nolting SP, Prasifka PL, Storer NP, Hopkins BW, Scherder EF, Siebert MW, Hendrix WH, III.. 2014. Efficacy of pyramided Bt proteins Cry1F, Cry1A.105, and cry2Ab2 expressed in Smartstax corn hybrids against lepidopteran insect pests in the northern United States. J Econ Entomol 107:403–409. doi: 10.1603/ec12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marques LH, Castro BA, Rossetto J, Silva OA, Moscardini VF, Zobiole LH, Santos AC, Valverde-Garcia P, Babcock JM, Rule DM, Fernandes OA. 2016. Efficacy of soybean's event DAS-81419-2 expressing Cry1F and Cry1Ac to manage key tropical lepidopteran pests under field conditions in Brazil. J Econ Entomol 109:1922–1928. doi: 10.1093/jee/tow153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimi DA, Parody B, Ramos ML, Machado M, Ocampo F, Willse A, Martinelli S, Head G. 2018. Field-evolved resistance to Bt maize in sugarcane borer (Diatraea saccharalis) in Argentina. Pest Manag Sci 74:905–913. doi: 10.1002/ps.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostrem JS, Pan Z, Flexner JL, Owens E, Binning R, Higgins LS. 2016. Monitoring susceptibility of western bean cutworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) field populations to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1F Protein. J Econ Entomol 109:847–853. doi: 10.1093/jee/tov383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith JL, Lepping MD, Rule DM, Farhan Y, Schaafsma AW. 2017. Evidence for field-evolved resistance of Striacosta albicosta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to Cry1F Bacillus thuringiensis protein and transgenic corn hybrids in Ontario, Canada. J Econ Entomol 110:2217–2228. doi: 10.1093/jee/tox228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farias JR, Andow DA, Horikoshi RJ, Sorgatto RJ, Fresia P, dos Santos AC, Omoto C. 2014. Field-evolved resistance to Cry1F maize by Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Brazil. Crop Prot 64:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storer NP, Babcock JM, Schlenz M, Meade T, Thompson GD, Bing JW, Huckaba RM. 2010. Discovery and characterization of field resistance to Bt maize: Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) in Puerto Rico. J Econ Entomol 103:1031–1038. doi: 10.1603/ec10040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JL, Farhan Y, Schaafsma AW. 2019. Practical resistance of Ostrinia nubilalis (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) to Cry1F Bacillus thuringiensis maize discovered in Nova Scotia, Canada. Sci Rep 9:18247. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vassallo CN, Figueroa Bunge F, Signorini AM, Valverde-Garcia P, Rule D, Babcock J. 2019. Monitoring the evolution of resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) to the Cry1F protein in Argentina. J Econ Entomol 112:1838–1844. doi: 10.1093/jee/toz076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ballester V, Granero F, Tabashnik BE, Malvar T, Ferre J. 1999. Integrative model for binding of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins in susceptible and resistant larvae of the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella). Appl Environ Microbiol 65:1413–1419. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.4.1413-1419.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurat-Fuentes JL, Adang MJ. 2001. Importance of Cry1 delta-endotoxin domain II loops for binding specificity in Heliothis virescens (L.). Appl Environ Microbiol 67:323–329. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.323-329.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernandez-Rodriguez CS, Hernandez-Martinez P, Van Rie J, Escriche B, Ferre J. 2013. Shared midgut binding sites for Cry1A.105, Cry1Aa, Cry1Ab, Cry1Ac and Cry1Fa proteins from Bacillus thuringiensis in two important corn pests, Ostrinia nubilalis and Spodoptera frugiperda. PLoS One 8:e68164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Granero F, Ballester V, Ferre J. 1996. Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins CRY1Ab and CRY1Fa share a high affinity binding site in Plutella xylostella (L.). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 224:779–783. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hernandez CS, Ferre J. 2005. Common receptor for Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac, Cry1Fa, and Cry1Ja in Helicoverpa armigera, Helicoverpa zea, and Spodoptera exigua. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:5627–5629. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5627-5629.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sena JA, Hernandez-Rodriguez CS, Ferre J. 2009. Interaction of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1 and Vip3A proteins with Spodoptera frugiperda midgut binding sites. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:2236–2237. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02342-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bel Y, Sheets JJ, Tan SY, Narva KE, Escriche B. 2017. Toxicity and binding studies of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac, Cry1F, Cry1C, and Cry2A proteins in the soybean pests Anticarsia gemmatalis and Chrysodeixis (Pseudoplusia) includens. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e00326-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00326-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hernandez-Martinez P, Bretsnyder EC, Baum JA, Haas JA, Head GP, Jerga A, Ferre J. 2022. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo binding sites competition of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1 proteins in two important maize pests. Pest Manag Sci 78:1457–1466. doi: 10.1002/ps.6763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gould F, Anderson A, Reynolds A, Bumgarner L, Moar W. 1995. Selection and genetic analysis of a Heliothis virescens (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) strain with high levels of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J Econ Entomol 88:1545–1559. doi: 10.1093/jee/88.6.1545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tabashnik BE, Finson N, Johnson MW, Heckel DG. 1994. Cross-resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin CryIF in the diamondback moth (Plutella xylostella). Appl Environ Microbiol 60:4627–4629. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4627-4629.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Velez AM, Spencer TA, Alves AP, Moellenbeck D, Meagher RL, Chirakkal H, Siegfried BD. 2013. Inheritance of Cry1F resistance, cross-resistance and frequency of resistant alleles in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Bull Entomol Res 103:700–713. doi: 10.1017/S0007485313000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monnerat R, Martins E, Macedo C, Queiroz P, Praca L, Soares CM, Moreira H, Grisi I, Silva J, Soberon M, Bravo A. 2015. Evidence of field-evolved resistance of Spodoptera frugiperda to Bt corn expressing Cry1F in Brazil that is still sensitive to modified Bt toxins. PLoS One 10:e0119544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Zhao JZ, Rodrigo-Simon A, Kain W, Janmaat AF, Shelton AM, Ferre J, Myers J. 2007. Mechanism of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in a greenhouse population of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:1199–1207. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01834-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira EJ, Lang BA, Storer NP, Siegfried BD. 2008. Selection for Cry1F resistance in the European corn borer and cross-resistance to other Cry toxins. Entom Exp Appl 126:115–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00642.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Banerjee R, Hasler J, Meagher R, Nagoshi R, Hietala L, Huang F, Narva K, Jurat-Fuentes JL. 2017. Mechanism and DNA-based detection of field-evolved resistance to transgenic Bt corn in fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda). Sci Rep 7:10877. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09866-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coates BS, Siegfried BD. 2015. Linkage of an ABCC transporter to a single QTL that controls Ostrinia nubilalis larval resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Fa toxin. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 63:86–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boaventura D, Ulrich J, Lueke B, Bolzan A, Okuma D, Gutbrod O, Geibel S, Zeng Q, Dourado PM, Martinelli S, Flagel L, Head G, Nauen R. 2020. Molecular characterization of Cry1F resistance in fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda from Brazil. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 116:103280. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baxter SW, Badenes-Perez FR, Morrison A, Vogel H, Crickmore N, Kain W, Wang P, Heckel DG, Jiggins CD. 2011. Parallel evolution of Bacillus thuringiensis toxin resistance in Lepidoptera. Genetics 189:675–679. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gahan LJ, Pauchet Y, Vogel H, Heckel DG. 2010. An ABC transporter mutation is correlated with insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. PLoS Genet 6:e1001248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma X, Shao E, Chen W, Cotto-Rivera RO, Yang X, Kain W, Fei Z, Wang P. 2022. Bt Cry1Ac resistance in Trichoplusia ni is conferred by multi-gene mutations. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 140:103678. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2021.103678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang X, Chen W, Song X, Ma X, Cotto-Rivera RO, Kain W, Chu H, Chen YR, Fei Z, Wang P. 2019. Mutation of ABC transporter ABCA2 confers resistance to Bt toxin Cry2Ab in Trichoplusia ni. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 112:103209. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2019.103209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Song X, Kain W, Cassidy D, Wang P. 2015. Resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry2Ab in Trichoplusia ni is conferred by a novel genetic mechanism. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:5184–5195. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00593-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kain WC, Zhao JZ, Janmaat AF, Myers J, Shelton AM, Wang P. 2004. Inheritance of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin in a greenhouse-derived strain of cabbage looper (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J Econ Entomol 97:2073–2078. doi: 10.1093/jee/97.6.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo W, Kain W, Wang P. 2019. Effects of disruption of the peritrophic membrane on larval susceptibility to Bt toxin Cry1Ac in cabbage loopers. J Insect Physiol 117:103897. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2019.103897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tiewsiri K, Wang P. 2011. Differential alteration of two aminopeptidases N associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in cabbage looper. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:14037–14042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102555108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kain W, Song X, Janmaat AF, Zhao JZ, Myers J, Shelton AM, Wang P. 2015. Resistance of Trichoplusia ni populations selected by Bacillus thuringiensis sprays to cotton plants expressing pyramided Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:1884–1890. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03382-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koziel MG, Carozzi NB, Currier TC, Currier TC, Warren GW, Evola SV. 1993. The insecticidal crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis: past, present and future uses. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev 11:171–228. doi: 10.1080/02648725.1993.10647901. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Janmaat AF, Wang P, Kain W, Zhao JZ, Myers J. 2004. Inheritance of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki in Trichoplusia ni. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:5859–5867. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5859-5867.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinos D, Wang Y, Hernandez-Martinez P, He K, Ferre J. 2022. Alteration of a Cry1A shared binding site in a Cry1Ab-selected colony of Ostrinia furnacalis. Toxins 14:32. doi: 10.3390/toxins14010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jakka SR, Knight VR, Jurat-Fuentes JL. 2014. Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) with field-evolved resistance to Bt maize are susceptible to Bt pesticides. J Invertebr Pathol 122:52–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Wang Y, Wang Z, Bravo A, Soberon M, He K. 2016. Genetic basis of Cry1F-resistance in a laboratory selected asian corn borer strain and its cross-resistance to other Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. PLoS One 11:e0161189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang F, Kerns DL, Head G, Brown S, Huang F. 2017. Susceptibility of Cry1F-maize resistant, heterozygous, and susceptible Spodoptera frugiperda to Bt proteins used in the transgenic cotton. Crop Prot 98:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2017.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boaventura D, Buer B, Hamaekers N, Maiwald F, Nauen R. 2021. Toxicological and molecular profiling of insecticide resistance in a Brazilian strain of fall armyworm resistant to Bt Cry1 proteins. Pest Manag Sci 77:3713–3726. doi: 10.1002/ps.6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Flagel L, Lee YW, Wanjugi H, Swarup S, Brown A, Wang J, Kraft E, Greenplate J, Simmons J, Adams N, Wang Y, Martinelli S, Haas JA, Gowda A, Head G. 2018. Mutational disruption of the ABCC2 gene in fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda, confers resistance to the Cry1Fa and Cry1A.105 insecticidal proteins. Sci Rep 8:7255. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25491-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang T, He M, Gatehouse AM, Wang Z, Edwards MG, Li Q, He K. 2014. Inheritance patterns, dominance and cross-resistance of Cry1Ab- and Cry1Ac-selected Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenee). Toxins (Basel) 6:2694–2707. doi: 10.3390/toxins6092694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tabashnik BE, Malvar T, Liu YB, Finson N, Borthakur D, Shin BS, Park SH, Masson L, de Maagd RA, Bosch D. 1996. Cross-resistance of the diamondback moth indicates altered interactions with domain II of Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:2839–2844. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.2839-2844.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong Y, Wang C, Yang Y, Wu S, Wu Y. 2010. Characterization of resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxin Cry1Ac in Plutella xylostella from China. J Invertebr Pathol 104:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jakka S, Ferré J, Jurat-Fuentes JL. 2015. Cry toxin binding site models and their use in strategies to delay resistance evolution, p 138–149. In Soberón M, Gao Y, Bravo A (ed), Bt resistance: characterization and strategies for GM crops producing Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. CABI, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bretschneider A, Heckel DG, Pauchet Y. 2016. Three toxins, two receptors, one mechanism: mode of action of Cry1A toxins from Bacillus thuringiensis in Heliothis virescens. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 76:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Endo H, Tanaka S, Adegawa S, Ichino F, Tabunoki H, Kikuta S, Sato R. 2018. Extracellular loop structures in silkworm ABCC transporters determine their specificities for Bacillus thuringiensis Cry toxins. J Biol Chem 293:8569–8577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.001761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tabashnik BE, Liu YB, Malvar T, Heckel DG, Masson L, Ballester V, Granero F, Mensua JL, Ferre J. 1997. Global variation in the genetic and biochemical basis of diamondback moth resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:12780–12785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.12780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Franz L, Raming K, Nauen R. 2022. Recombinant expression of ABCC2 variants confirms the importance of mutations in extracellular loop 4 for Cry1F resistance in fall armyworm. Toxins 14:157. doi: 10.3390/toxins14020157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X, Xu Y, Huang J, Jin W, Yang Y, Wu Y. 2020. CRISPR-mediated knockout of the ABCC2 gene in Ostrinia furnacalis confers high-level resistance to the Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Fa toxin. Toxins 12:246. doi: 10.3390/toxins12040246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhao S, Jiang D, Wang F, Yang Y, Tabashnik BE, Wu Y. 2020. Independent and synergistic effects of knocking out two ABC transporter genes on resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry1Fa in diamondback moth. Toxins 13:9. doi: 10.3390/toxins13010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Huang J, Xu Y, Zuo Y, Yang Y, Tabashnik BE, Wu Y. 2020. Evaluation of five candidate receptors for three Bt toxins in the beet armyworm using CRISPR-mediated gene knockouts. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 121:103361. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2020.103361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Iracheta MM, Pereyra-Alferez B, Galan-Wong L, Ferre J. 2000. Screening for Bacillus thuringiensis crystal proteins active against the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. J Invertebr Pathol 76:70–75. doi: 10.1006/jipa.2000.4946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boodley JW, Sheldrake R, Jr.. 1982. Cornell peat-lite mixes for commercial plant growing. New York State Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletins 43. New York State, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang R, Tetreau G, Wang P. 2016. Effect of crop plants on fitness costs associated with resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab in cabbage loopers. Sci Rep 6:20959. doi: 10.1038/srep20959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Russell RM, Robertson JL, Savin NE. 1977. POLO: a new computer program for probit analysis. Bull Entomoll Soc Am 23:209–213. doi: 10.1093/besa/23.3.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stone BF. 1968. A formula for determining degree of dominance in cases of monofactorial inheritance of resistance to chemicals. Bull World Health Organ 38:325–326. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang S, Kain W, Wang P. 2018. Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins exert toxicity by multiple pathways in insects. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 102:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

DNA sequences of the diagnostic PCR fragments for the two ABCC2 alleles have been deposited in GenBank with acc. no. MZ571761 and MZ571762.