Abstract

Alice McGushin and colleagues argue for recognition of the diverse ways in which climate change affects adolescent wellbeing and call for health professionals to work with them to respond to the crisis

The world is already 1.1°C warmer than during pre-industrial levels, and we can expect further rises of between 1.5°C and 3.5°C by the end of this century, depending on the scale and speed of climate change mitigation.1 The impact of global warming is far greater for a child born today than for older generations: in comparison with someone born in 1960, a person born in 2020 will experience considerably more exposure to drought, crop failures, river floods, and four times as many heat waves throughout their lifetime.2 Adding to this, it is projected that low income countries will have the greatest increase in the number of young people aged 10-24 in the coming decades. The younger generations in these countries will experience the greatest rise in climate related exposures, with vulnerabilities compounded by continuing protracted inequity driven by colonialism, poverty, challenges of governance and conflict, and marginalisation due to gender, ethnicity, and low income.1

The climate crisis is the biggest global health threat of our century,3 destabilising social, environmental, and economic determinants of health and wellbeing. Despite compelling evidence that climate change will affect the life of every child born today, an understanding of the effects on adolescents is limited. We argue that it is time for more explicit recognition by health professionals of these impacts on adolescents’ physical and mental health, and also the broader effects on their wellbeing. It is important that health professionals recognise their responsibility to support adolescents and protect their wellbeing from the climate crisis.

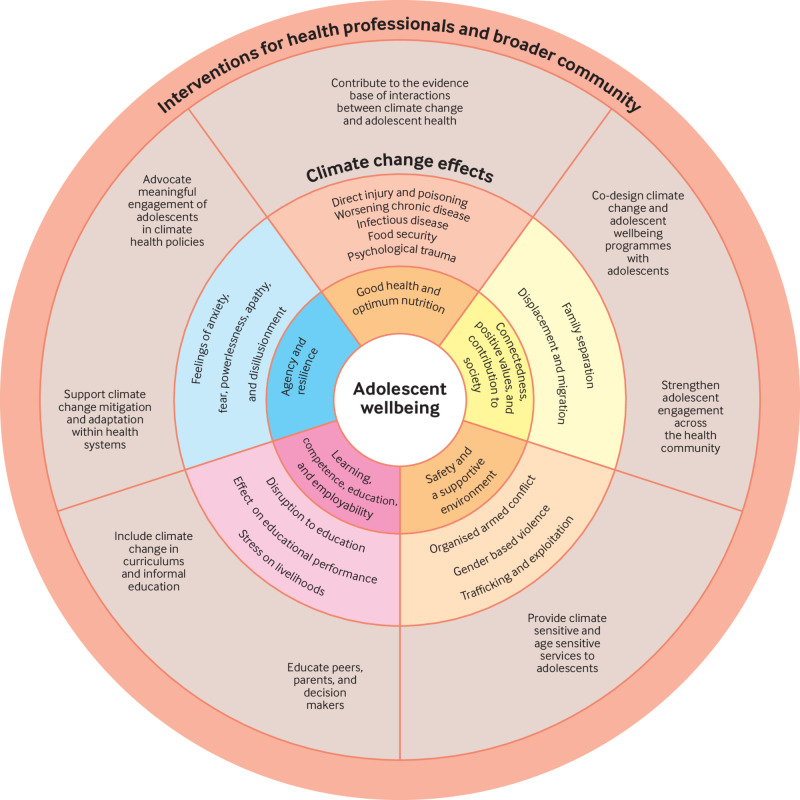

To analyse the effects of climate change on adolescents, we use an existing definition and conceptual framework of adolescent wellbeing.4 Adolescent wellbeing is a state in which adolescents have the support, confidence, and resources to thrive, realising their full potential and rights.4 Good health and optimum nutrition are recognised as essential for adolescent wellbeing, acting as both determinants and outcomes of four other domains: connectedness, positive values, and contributions to society; safety and supportive environments; learning, education, and employability; and agency and resilience.

Climate change threatens all aspects of adolescent wellbeing (fig 1), but not all adolescents are passive victims of this crisis. We highlight examples of the ways in which adolescents around the world have taken leadership, demonstrating agency and resilience both individually and collectively. They are a heterogeneous group, however, and their capacity to cope in a changing climate can be fostered by an environment, strengthened by functioning support systems at individual, community, country, and global levels.5 Health professionals have a clear role in supporting adolescents to thrive in a changing climate.

Fig 1.

Adolescent wellbeing framework, described by the H6+ Technical Working Group on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing* and adapted to include related climate change effects and interventions at the level of health professionals and the broader community. *The H6+ Technical Working Group on Adolescent Health and Wellbeing includes the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health; United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; Unesco; UN Population Fund; Unicef, UN Major Group for Children and Youth; UN Women; World Bank; World Food Programme; and World Health Organization

Climate crisis affects all domains of adolescent wellbeing

To understand the effects of the climate crisis on adolescents’ health and nutrition, we examine the evidence of its risks to leading health concerns for adolescents. Climate change exacerbates the risk of injury, the leading cause of death and disability in this age group, by exposure to extreme weather events, with adolescents with disabilities and chronic diseases at greatest risk in disasters.6 Considering asthma, the most common chronic disease among adolescents, higher pollen levels, longer pollen seasons, worsening air quality, and increasing thunderstorms all increase the risk of acute asthma attacks.7,8

The psychological distress caused by extreme weather, climate induced forced migration, and expectation of future hazards might have lifelong consequences for the mental wellbeing of adolescents—with the effects more likely to be experienced by those in low and middle income countries.9–11 The climate crisis also affects adolescents’ nutrition, with downstream effects on physical and cognitive development; adolescent girls in low and middle income countries are more likely than boys, or adolescents in high income countries, to go hungry after climate related disasters.12

The climate crisis affects adolescents’ relationship with families and communities causing temporary and permanent migration and displacement, within countries and across borders. Although age disaggregated data are scarce, a high proportion of those displaced owing to climate related disasters is under 18.13 Before recent conflict, adolescents in the drought affected Tigray region of Ethiopia were forced to separate from their families because of food insecurity, loss of livelihoods, and the need to earn an income.14

A disrupted and unsafe living environment is another effect of the climate crisis. Climate related economic shocks and low rainfall have increased the risk of armed conflict in some settings.15 The resulting effects of such conflict on adolescents can last a lifetime and be passed down generations.16 Drought and heat waves have also been found to increase the risk of intimate partner violence.17,18 Furthermore, extreme events such as the 2010–11 Horn of Africa drought increase the likelihood of child marriage, with young girls sold in exchange for livestock and other necessities, as their families struggled with scarce resources.19

Attainment of quality education, the fourth Sustainable Development Goal, is threatened by the climate crisis. In 2017, 18 000 schools in South Asia were closed owing to river flooding.20 Schools in Bangladesh remained closed a year after the destruction of the Cyclone Aila, and extreme weather events are the commonest cause of unplanned school closures in the US.21,22 Moreover, when communities face water scarcity and drought, adolescents, particularly girls, might be removed from school to support their families. Higher temperatures are also known to affect the academic performance of both students and teachers.23,24

Finally, agency and resilience are threatened both by the climate crisis and the gap between actions needed and those that adolescents see being taken by global leaders. The dissonance between government responses and the prospect for the world has left many adolescents feeling a loss of agency, apathy, and disillusionment.25 Psychological distress caused by climate change is becoming particularly prevalent among adolescents. In a recent survey of over 10 000 young people aged 16-25 in 10 countries, over 50% of respondents reported feeling anxious, afraid, and powerless in the face of climate crisis.26

With these overwhelming threats to wellbeing, one would not blame adolescents for feeling hopeless and helpless. Nevertheless, there are many and varied examples of adolescents responding to the climate crisis with agency and resilience. We argue that many are exhibiting leadership beyond their years, sometimes beyond that which is displayed by those in positions of power.

Adolescents showing agency and resilience

It has often been suggested that action is an antidote to climate related anxiety and poor wellbeing.27 Young people who take part in climate action have fostered individual and interpersonal skills that contribute to youth development, such as the capacity to self-regulate emotions and behaviour, take part in teamwork, act on values such as social and environmental justice, and reduce the feeling of being alone and powerless.5,25,27

Adolescents on every continent are taking part in climate action. To combat malnutrition in their communities, adolescents from youth led organisations in Rwanda are being trained in nutrition advocacy and associated concerns, such as environmental protection, gender discrimination, education, and the economy.28 Adolescents surveyed in flood prone areas in Indonesia, Burkina Faso, and Bolivia and in areas of drought in South Africa expressed a strong sense of duty and empathy, which they used to support their communities—for example, by sharing information on ways to conserve water.29,30 Building personal resilience to climate related threats, Inuit youth in Canada described factors such as being on the land and connecting with Inuit culture as protective for their mental health and wellbeing.31

Adolescents have used the UN Conventions on the Rights of the Child, including the right to life and health, in lawsuits against governments. In a legal petition filed by 16 adolescents against five G20 members (Argentina, Brazil, France, Germany, and Turkey), claiming violation of their rights, Deborah Adegbile of Nigeria asserted that she had been repeatedly admitted to hospital for asthma attacks, triggered by rising temperatures and smog.32 Upholding their right to education, students at Santa Paz National High School in the Philippines won a campaign to have their school relocated because of the risk of a landslide.33 Adolescents are also taking what they have learnt about climate change to educate their families and communities, driving broader societal action.34

The “Fridays for Future” movement has resulted in the largest climate protests in history, with actions in over 7500 cities around the world. As the “new ambassadors for scientific consensus and climate mitigation,” adolescents are at the forefront of the movement to hold governments and industries accountable for their emissions.35 Many young people, however, assert that their inclusion in global platforms, such as the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change conferences, has been tokenistic rather than a serious attempt to respond to their views.36

Adolescents rarely hold the power to implement the change and transformation necessary to protect all people from the negative effects of the climate crisis. As illustrated by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report, there is a need for “equitable sharing of benefits and burdens of mitigation” and an enhancement of the resilience of those who are most vulnerable, through a climate justice lens.1 While it is adolescents’ right to have their views taken seriously in all matters that affect them, the responsibility falls squarely on those who hold power—governments, policy makers, and the health community—to lead in responding to the climate crisis.

How health professionals can unite with young people

Many adults are failing young people, but we argue that health professionals have a social responsibility to join with adolescents in responding to the climate crisis. Other health leaders have argued that because of their many professional and societal roles, health professionals are in a unique and privileged position to influence change.37 Such change has been seen for other health concerns, including sanitation and hygiene, tobacco control legislation, denuclearisation, and the prevention of war. Health professionals must do the same for the climate crisis, to support the wellbeing of adolescents and their communities.

Health professionals will be on the frontline of providing climate and age sensitive health services to adolescents. Evidence is scarce, however, on both the effects of climate change on adolescents and effective interventions to be taken by health professionals to protect any age group.38,39 To implement the most appropriate climate interventions, it is crucial that health professionals support the surveillance, analysis, and reporting of the climate sensitive burden of disease on adolescents, while being aware of other factors, such as socioeconomic disadvantage, history of exploitation, and geographical location. Furthermore, more evidence is needed for those interventions which might protect adolescent wellbeing in climate related conflict and disaster settings, and for adolescents experiencing climate related migration.

The experience and competence of health professionals at every level is essential to protecting the wellbeing of all people from the effects of climate change. The younger generation of health professionals is providing leadership, with medical students acting globally to include climate change within curriculums.40 Like adolescents, health professionals can spread awareness of the scale and effect of climate change, and its links to adolescent wellbeing, involving educators, parents, peers, and elected officials, so that they can make informed decisions about individual and collective responses to the climate crisis.

The health community can also work to decarbonise its own practice. Now almost 60 countries have committed to having low carbon resilient healthcare systems, and there will be global cooperation to support net zero healthcare efforts.41 The evidence and the action in this area are expanding rapidly, with opportunities to decarbonise also at the individual practice, health facility, and specialty level.

Health professionals should collaborate with adolescents in their advocacy efforts. Using their skills developed in training and practice and their societal influence, health professionals can take part in intergenerational dialogue and involve adolescents in climate and health related policy making processes.

Conclusion

As part of a holistic approach to adolescent wellbeing, it is clear that the climate crisis has far reaching effects on adolescents. Despite—or because of—this overwhelming threat to their current and future wellbeing, many adolescents show the ability to respond; we are encouraged that health workers have recently stepped up to this challenge, although further work is necessary, across all the areas we have described above. It is imperative that health professionals work hand in hand with adolescents to enable them to thrive in the 21st century.

Key messages.

The worsening threat of climate change affects all aspects of adolescents’ wellbeing

Many feel the threat to their future, are overwhelmed by the scale of the problem, and are disillusioned by inadequate action of those in power

Adolescents are taking matters into their own hands, acting individually and collectively to reduce the negative effects of the climate crisis

Health professionals must work collectively with adolescents to mitigate the effects of climate change on adolescent wellbeing

Acknowledgments

The writing group members are Shanthi Ameratunga (University of Auckland), Valentina Baltag (World Health Organization), Michelle Heys (University College London), Raúl Mercer (Programme of Social Sciences and Health, Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales), Adesola O Olumide (University of Ibadan), and Mark Tomlinson (Stellenbosch University). We also thank David Ross, Rachael Hinton, Sophie Kostelecky, and Anshu Mohan for their input.

Contributors and sources: This article draws from the work of the background paper, “Adolescent well-being and the climate crisis,” which was one of a series of background papers on adolescent wellbeing, commissioned by the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH). AMcG is a health and climate change expert. She was programme manager of the Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change and is coauthor of its reports and other research articles. GG works on the intersection between climate change and women’s, children’s, and adolescents’ wellbeing and rights. She is an advocate and researcher within climate youth networks including YOUNGO, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change youth constituency. VG works at the interface of mental health, psychosocial wellbeing, and climate change. She supports research activities at the MHPSS Collaborative (hosted by Save the Children Denmark). CN is a Rwandan medical doctor and global health expert focusing on climate health advocacy, particularly to do with air pollution and non-communicable diseases. ST is an intern doctor at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Kathmandu, with a keen interest in climate health. FB is a leading physician, public health professional, and advocate for the health and human rights of women, children, adolescents, and elderly people. She is vice president of Fondation Botnar and is the former assistant director general for family, women’s, and children’s health for the World Health Organization. AC is a paediatrician and co-chair of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change and led the development of Children in All Policies 2030. AMcG is the guarantor.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no interests to declare.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is part of collection proposed by the Partnership for Maternal Newborn and Child Health. Open access fees are funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The BMJ commissioned, peer reviewed, edited, and made the decision to publish these articles. Emma Veitch was the lead editor for The BMJ.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: UN H6+ Adolescent Health and Wellbeing and the Climate Crisis Writing Group, Shanthi Ameratunga, Valentina Baltag, Michelle Heys, Raúl Mercer, Adesola O Olumide, and Mark Tomlinson

References

- 1. IPCC . Summary for policymakers. In: Shukla P, Skea J, Slade R, al Khourdajie A, van Diemen R, McCollum D, eds. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thiery W, Lange S, Rogelj J, et al. Intergenerational inequities in exposure to climate extremes. Science 2021;374:158-60. 10.1126/science.abi7339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A, et al. Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission . Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet 2009;373:1693-733. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ross DA, Hinton R, Melles-Brewer M, et al. Adolescent well-being: a definition and conceptual framework. J Adolesc Health 2020;67:472-6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sanson AV, van Hoorn J, Burke SEL. Responding to the impacts of the climate crisis on children and youth. Child Dev Perspect 2019;13:201-7. 10.1111/cdep.12342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seddighi H, Yousefzadeh S, López López M, Sajjadi H. Preparing children for climate-related disasters. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000833. 10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davies JM, Berman D, Beggs PJ, et al. Global climate change and pollen aeroallergens: a southern hemisphere perspective. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2021;41:1-16. 10.1016/j.iac.2020.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kevat A. Thunderstorm asthma: looking back and looking forward. J Asthma Allergy 2020;13:293-9. 10.2147/JAA.S265697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Majeed H, Lee J. The impact of climate change on youth depression and mental health. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1:e94-5. 10.1016/S2542-5196(17)30045-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goenjian AK, Molina L, Steinberg AM, et al. Posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among Nicaraguan adolescents after hurricane Mitch. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:788-94. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pfefferbaum B, Jacobs AK, Jones RT, Reyes G, Wyche KF. A skill set for supporting displaced children in psychological recovery after disasters. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2017;19:60. 10.1007/s11920-017-0814-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Global Gender and Climate Alliance . Gender and climate change: a closer look at existing evidence. 2016. https://wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/GGCA-RP-FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unicef. The climate crisis is a child rights crisis: introducing the Children’s Climate Risk Index. 2021. https://www.unicef.org/media/105376/file/UNICEF-climate-crisis-child-rights-crisis.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. MacFarlane M, Rubenstein BL, Saw T, Mekonnen D, Spencer C, Stark L. Community-based surveillance of unaccompanied and separated children in drought-affected northern Ethiopia. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2019;19:19. 10.1186/s12914-019-0203-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mach KJ, Kraan CM, Adger WN, et al. Climate as a risk factor for armed conflict. Nature 2019;571:193-7. 10.1038/s41586-019-1300-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kadir A, Shenoda S, Goldhagen J. Effects of armed conflict on child health and development: a systematic review. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210071. . 10.1371/journal.pone.0210071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Epstein A, Bendavid E, Nash D, Charlebois ED, Weiser SD. Drought and intimate partner violence towards women in 19 countries in sub-Saharan Africa during 2011-2018: a population-based study. PloS Med 2020;17:e1003064. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanz-Barbero B, Linares C, Vives-Cases C, González JL, López-Ossorio JJ, Díaz J. Heat wave and the risk of intimate partner violence. Sci Total Environ 2018;644:413-9. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. OCHA . Horn of Africa: a call for action. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ryan E, Wakefield J, Luthen S. Born into the climate crisis – why we must act now to secure children’s rights. Save the Children, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oxfam. One year on from Cyclone Aila, people are still struggling to survive. Nairobi, 2010 https://www.oxfamamerica.org/press/one-year-on-from-cyclone-aila-people-are-still-struggling-to-survive/

- 22. Wong KK, Shi J, Gao H, et al. Why is school closed today? Unplanned K-12 school closures in the United States, 2011-2013. PloS One 2014;9:e113755. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nauges C, Strand J. Water hauling and girls’ school attendance: some new evidence from Ghana. Environ Resour Econ 2017;66:65-88 10.1007/s10640-015-9938-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bidassey-Manilal S, Wright CY, Engelbrecht JC, Albers PN, Garland RM, Matooane M. Students’ perceived heat-health symptoms increased with warmer classroom temperatures. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:566. 10.3390/ijerph13060566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevenson KT, Peterson MN, Bondell HD. Developing a model of climate change behavior among adolescents. Clim Change 2018;151:589-603 10.1007/s10584-018-2313-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hickman C, Marks E, Pihkala P, et al. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. Lancet Planet Health 2021;5:e863-73. 10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hawkins DMT, Letcher P, Sanson A, Smart D, Toumbourou JW. Positive development in emerging adulthood. Aust J Psychol 2009;61:89-99 10.1080/00049530802001346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sibomana F. Let’s include the voice of young people and support their initiatives in nutrition advocacy. Voices of Youth, 2020. https://www.voicesofyouth.org/blog/lets-include-voice-young-people-and-support-their-initiatives-nutrition-advocacy

- 29. de Milliano CWJ. Luctor et emergo, exploring contextual variance in factors that enable adolescent resilience to flooding. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 2015;14:168-78. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Theron L, Ruth Mampane M, Ebersöhn L, Hart A. Youth resilience to drought: learning from a group of South African adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:7896. 10.3390/ijerph17217896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Petrasek MacDonald J, Cunsolo Willox A, Ford JD, Shiwak I, Wood M, IMHACC Team. Rigolet Inuit Community Government . Protective factors for mental health and well-being in a changing climate: perspectives from Inuit youth in Nunatsiavut, Labrador. Soc Sci Med 2015;141:133-41. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacchi, et al v Argentina, et al. Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. 2019. http://climatecasechart.com/non-us-case/sacchi-et-al-v-argentina-et-al/

- 33.Morrissey I, Mulders-Jones S, Petrellis N, Evenhuis M, Treichel P. We stand as one: children. Young people and climate change. Plan International Australia (Melbourne), 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lawson DF, Stevenson KT, Peterson MN, Carrier SJ, Strnad R, Seekamp E. Intergenerational learning: are children key in spurring climate action? Glob Environ Change 2018;53:204-8 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eide E, Kunelius R. Voices of a generation: the communicative power of youth activism. Clim Change 2021;169:6. 10.1007/s10584-021-03211-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global Youth Statement. Conference of Youth 16. 2021. https://ukcoy16.org/global-youth-statement

- 37. Dobson J, Cook S, Frumkin H, Haines A, Abbasi K. Accelerating climate action: the role of health professionals. BMJ 2021;375:n2425. 10.1136/bmj.n2425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Helldén D, Andersson C, Nilsson M, Ebi KL, Friberg P, Alfvén T. Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet Health 2021;5:e164-75. 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30274-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dupraz J, Burnand B. Role of health professionals regarding the impact of climate change on health—an exploratory review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:3222. 10.3390/ijerph18063222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Omrani OE, Dafallah A, Paniello Castillo B, et al. Envisioning planetary health in every medical curriculum: an international medical student organization’s perspective. Med Teach 2020;42:1107-11. 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1796949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.WHO. WHO and NHS to work together on decarbonization of health care systems across the world. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/who-and-nhs-to-work-together-on-decarbonization-of-health-care-systems-across-the-world